Abstract

The so-called ‘Hamond’ partbooks (British Library, Add. MSS 30480-4) were copied over a period of c.40 years by multiple groups of collaborating scribes, resulting in a miscellaneous combination of service music, sacred songs, Latin motets, chansons, madrigals, an In nomine, and even Mass extracts. These partbooks are the only complete manuscript source of Protestant service music from the first decades of Elizabeth’s reign. This first holistic study of this set of partbooks re-evaluates the stages of compilation and the copying practices of the scribes to offer new interpretations of the manuscripts’ history and contexts. The article argues that the partbooks began life as a liturgical and educational collection for the training of choirboys. These partbooks therefore offer a unique insight into the repertory and practices of one Protestant institution, highlighting the continued reliance on Edwardian repertories over a decade into Elizabeth’s reign, as well as the growing availability of continental printed music. The transmission of these partbooks is then traced to a more domestic and recreational setting, exploring their relationship to the Hamond family. While Thomas Hamond of Hawkedon in Suffolk inscribed his ownership inside the covers in 1615, the re-evaluation of the compilation and history of these partbooks reveals that the books were in the possession of the Hamond family from at least the late 1580s/early 1590s. This family added new pieces, made repairs and engaged with the music copied by previous owners. Ultimately their preservation was assured by the younger Thomas Hamond’s interest in older music, and they continued to be a source of historical interest for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century music antiquarians.

GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4 is the least known of the handful of extant sets of complete partbooks from the Elizabethan period.Footnote1 Although they are often casually known as the ‘Hamond’ partbooks after their first known owner – Thomas Hamond of Hawkedon in Suffolk – who inscribed his ownership inside the covers in 1615, by this time the partbooks were already around 45 years old. Unlike the better-known sets of Robert Dow and John Sadler or the near complete set of John Baldwin, these partbooks are neither elegantly copied nor adorned with inscriptions or illustrations.Footnote2 They are a work-a-day set, well worn and full of corrections and with several missing pages. They are also far more miscellaneous in their contents. Beginning with canticles for Morning and Evening Prayer, they also include anthems and other sacred vernacular songs, consort songs and a large section of textless music including Latin motets by continental and English composers, chansons, madrigals, an In nomine, a metrical psalm, and even extracts from a Mass (see ). These partbooks are further complicated by the exceptionally numerous text and notation hands – many belonging to inexperienced copyists judging by their awkwardly formed noteshapes – and a copying span of nearly 50 years.

The origins and early life of these partbooks are obscure, but they are the only major manuscript source of Protestant service music from the first decades of Elizabeth’s reign. Moreover, just over a third of their contents are unique, and they preserve two of only a handful of surviving songs from Queen Elizabeth I’s royal progresses.Footnote3 It is remarkable therefore that, although they have been frequently consulted by editors, there has been no detailed study since the theses of May Hofman and Warwick Edwards in the 1970s.Footnote4 Yet even these two scholars were interested primarily in the final section of textless music, focusing on the Latin motets and the instrumental music respectively as part of much larger studies. The particular focus of these studies has led to misconceptions about the compilation of these books with consequences for our understanding of the contexts in which they were copied and used.

In undertaking the first holistic study of this set of partbooks it has been possible to re-evaluate the stages of compilation and the copying practices of its scribes to construct a new history of these partbooks. Firstly I argue that the partbooks began life as a liturgical and educational collection for the training of choirboys; secondly, I trace their transmission to a more domestic context and explore their relationship to the Hamond family who can now be shown to have possessed the partbooks from at least the late 1580s/early 1590s. In contrast to the emphasis on Catholic musical survival in Elizabethan England in much recent scholarship, a reassessment of this manuscript sheds new light on music-making in Protestant institutions and households during Elizabeth’s reign. Moreover, this analysis demonstrates the importance of evaluating such musical miscellanies as totalities. When better understood, such miscellanies offer different perspectives on Tudor musical culture to the better-known, more homogeneous partbooks that have received the most scholarly attention.

Physical description

The partbooks began life as a set of four oblong volumes (Add. MSS 30480-3). Although rebound in modern covers of red leather and cloth on boards in 1959, parts of the original parchment covers were retained within the new bindings. While very worn, there are signs that part designations were originally written on the covers (), and that these titles may have been rewritten by another hand as the first became worn away.

Table I. Part designations on the covers of GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4.

The inside covers of the initial four books are also inscribed with the name of the first readily identifiable owner, Thomas Hamond.Footnote5 The form is very similar in each book and that in 30481 reads:

octavo die octobris. 1615.

m[emoran]d[um] that Thomas Hamond of Hawkedon is the true owner of these books. In witness whereof I have put to my hand the day and year first above written

p[er] me Thomas Hamond

Thomas Hamond ow[ns] these books witness Geo[rge]: Ham[ond]: Rob[er]t Hamond; Phillip Hamond Rob[er]t Hamond Jun[io]r.Footnote6

The approximate age of the partbooks can be ascertained from the distinctive paper used to create the first four books. This was paper with printed music staves and a decorative border created from a combination of two fleurons or printers’ flowers. Iain Fenlon and John Milsom were previously able to date this music paper to the mid-1560s. A firmer terminus post quem for the start of copying is now possible, as I have recently linked this music paper to the printing partnership of Thomas East and Henry Middleton, which operated from 1567–72.Footnote7 The first known appearance of this particular fleuron design is in 1568; however, the paper used in 30480-3 may date from later within this period as it shows greater wear on the fleurons and more significant bending of the stave rules than other extant examples.Footnote8 A creation date of c.1570 therefore seems plausible, though it is possible that the paper sat on the shelves of either the seller or the purchaser for some time after the paper’s production.

The paper for the initial four books was bought in a single batch and was either bought as bound books or bound shortly after purchase (and before the fifth partbook, which has a different cover, was begun). The original paper sheets were folded into oblong quartos, which were then nested to make gatherings of eight folios.Footnote9 In their current state the partbooks each have between 84 and 93 folios of printed music paper, but all show signs of having lost pages.Footnote10 The most likely scenario is that each partbook was originally made up of 12 gatherings or 96 folios (though it is possible that the bassus book always had one less gathering).

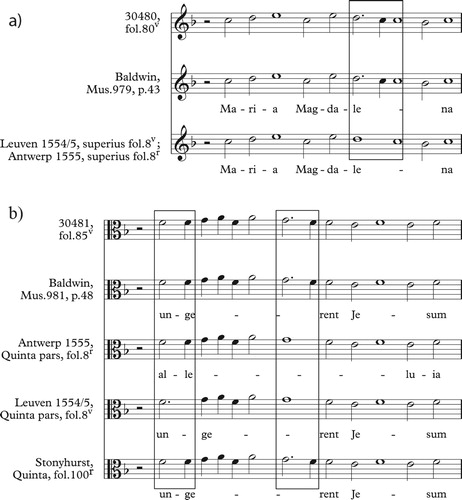

The paper used was originally all from the same printing batch with identical wear and flaws in the printed border (see ); however, two gatherings in 30480 were printed onto different paper with a variant pot watermark and narrower chain lines. As there are no indications of disturbance to suggest that this was a later insertion, these were probably just sheets from another batch of paper included in the bundle of music paper that was bought from the printer.Footnote11

Table II. Paper types used in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4.

Two other types of paper without printed staves were used to make repairs or additions. Damage occurred to folios 66–7 of the tenor partbook (30482) that caused them to be recopied by a later hand on plain paper with hand-drawn staves. Other exempla of this watermark date from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, which is consistent with the latest phase of copying in c.1591–1615. The final paper-type occurs at the end of the bassus partbook, 30483, where another two folios of plain paper were added at the end. Judging by the first piece copied on these hand-ruled pages, they were inserted towards the end of the original layer of copying (see ‘Phase IV’, later in this article).

The fifth partbook – Add. MS 30484 – was a later addition. The book is bound in parchment taken from an old Sarum breviary (though only fragments of the back cover now remain).Footnote12 The pages of plain paper were ruled as needed with staves of various sizes, five or six to a page. While the partbook looks like a motley collection with its diversity of rulings, the manuscript was made up of just one type of paper (see ).Footnote13 Such consistency means that even if the anthems and textless music were originally begun as separate booklets, they must have been compiled into a book at an early stage.Footnote14 Nineteen folios are extant, but a conjectural reconstruction based on the watermarks suggests that there could have been at least 22 folios originally.Footnote15 The irregular appearance of watermarks indicates a degree of disturbance at the beginning; at the end, the half folio (fol. 20) has been reversed, and another folio containing the fifth part of Tallis’s When Jesus Went has been lost.

Contents and structure

Despite the heterogeneity of the contents shown in , 30480-4 clearly open with service music, while the back section of the partbooks is predominantly made up of textless music in a variety of genres. The mid-section appears more confused with sacred songs, consort songs and textless pieces. Beyond this broad outline, however, the scribal and organizational complexities of 30480-4 have led to strikingly different conclusions about the structure and chronology of the compilation of these partbooks. The differences are manifold, but in broad terms May Hofman saw the copying as largely progressing from front to back though successive copyists (with some later infill) such that the textless repertory towards the end was seen as copied at a significantly later date than the service music.Footnote16 Meanwhile Warwick Edwards believed the textless music at the end of the manuscript to have been begun by the same hand as contributed the service music and most of the anthems ‘during or perhaps after’ the original layer. Indeed Edwards identified instances of his first hand recurring even in his last phase of copying.Footnote17 Such different analyses clearly had contrasting implications for both the chronology of compilation, the assumed contexts, and patterns of ownership and transmission.

Table III. Summary of contents of GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4.

The limitation of both analyses, however, was that the scholars were primarily interested in the latter part of the books that is predominantly textless, and so based their analysis on the notation hands alone. My own assessment has benefitted from the availability of digital images and is the first to consider the text hands as well as those copying the musical notation, and to have given equal focus to the service music and anthem sections. The picture that emerges from my analysis agrees with Edwards in drawing connections between the textless repertory and the service music with anthems, but is closer to Hofman’s in identifying a series of successive phases of ownership rather than the continuing recurrence of the first scribe.

I have also identified a significantly larger number of hands copying both notation and/or text, identifying evidence of collaborative copying practices and several short passages by novice scribes.Footnote18 Indeed the number of hands identified has proved so large that they are best dealt with as families of related hands rather than individually. As many of the distinctions between hands often rely on small differences between scribes using the same model script, the hands can be grouped into successive phases in which the majority of copyists tended to share similar noteshapes, text styles or other features. Indeed the precise number of scribes cannot be determined with any certainty as it is hard to distinguish between two copyists employing the same model hand with minor variations and small changes in the hand of a single scribe over time, especially when dealing with immature hands that are likely to still be developing. Connecting text and notation hands to a single scribe can be equally tricky in a manuscript where collaboration is frequent. Moreover a single scribe might employ more than one script (round and diamond notation, or secretary and italic text).

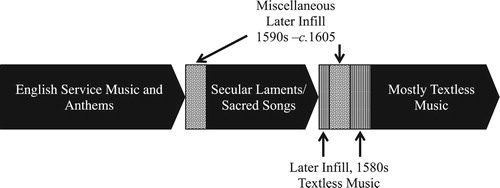

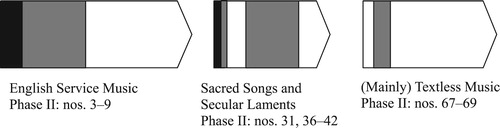

Yet if the precise number of people involved in the copying of these books remains obscure, a series of copying phases nevertheless emerges clearly. My analysis reveals that during the original layer three sections were copied concurrently (see , black sections):

Mostly service music with some intervening anthems towards the end;

Anthems or sacred songs with some secular laments;

Predominantly textless music (though the texts are often preserved in the bassus partbook) in a variety of genres including Latin motets, an In nomine, chansons, madrigals and a metrical psalm.

Nevertheless, the resulting manuscripts are more confused than this trifold division would suggest as neither the contents of the sacred song section nor the textless music were copied sequentially. The distinctions between these sections have also been blurred as later copying during the 1580s and 1590–1600s filled the gaps in-between (patterned sections in , and shaded sections in ).Footnote19 Further complexity has resulted from the recopying of some parts by these later scribes, presumably as pages came loose or sustained damage (indicated by bold type in ). Some of these recopied parts are clear as they involved replacement pages recopied onto blank paper with hand-ruled staves (fols 66–67 in 30482). Other parts recopied onto blank printed staves in the already complex middle sections are less immediately apparent.Footnote20

This revised view of the original compilation has significant implications for the functions and context of this manuscript. Hofman and Peter Le Huray regarded the partbooks as a domestic, non-liturgical collection, while most recently Milsom suggested that it ‘almost certainly started life under a church roof’ before later being owned by a Protestant family.Footnote21 As my analysis suggests that the sections were being copied concurrently not consecutively, I argue that the original collection not only had liturgical connections, but was also particularly associated with choirboys and their training. Moreover, identifying parallels between the later hands and another manuscript owned by Thomas Hamond of Hawkedon (GB-Ob: Mus. f. 7-10) has enabled a better understanding of the later domestic stages of copying and use.

This first part of the article sets out the primary phases of copying in the original layer, before exploring the repertory collected across these phases and the implications for our understanding of the context in which these partbooks were used and created. My principal argument is that the combination of liturgical, devotional and textless music points to an association with the training of choirboys, whose presence is further hinted at in the range of the ensemble required for some of the liturgical music, in the presence of novice copyists, and in the inclusion of a setting of a prayer specifically aimed at young men. While the manuscripts cannot yet be firmly connected to a specific institution, the partbooks nevertheless offer a rare insight into the musical culture of the early reign of Elizabeth I. A picture emerges of a backward-looking and conservative liturgical culture, even in an institution with access to courtly sources and a variety of continental music.

The latter part re-examines the books’ connections with the Hamond family, suggesting that the father of the 1615 owner (also named Thomas) is the most likely candidate for transferring the manuscripts to their new domestic context. Close decorative and reportorial links to another extant partbook, British Library Add. MS 47844, date this transference to c.1581. Scribal concordances in other partbooks owned by the 1615 Thomas Hamond (Bodleian Library, Mus. f. 7-10) show that numerous members of the Hamond family interacted with these manuscripts during the 1590s and early 1600s – a rare example of communal family ownership of a set of partbooks. This phase of the partbooks’ history offers a window into the music-making of a Protestant family c.1600, revealing their musical tastes as they added new pieces, made repairs, and engaged with both the sacred and secular music copied by previous owners.

The copying of the original layer

The original layer of copying is itself the result of four distinct but overlapping phases of labour. Despite the changes in scribes, the manuscripts’ context is unlikely to have changed significantly as successive groups were typically able to complete the unfinished work of their predecessors. Indeed there were sometimes periods of collaborative copying between the outgoing and the incoming scribes. These scribes clearly maintained access to the same materials and are likely to have been working in the same institution over a period of up to a decade.

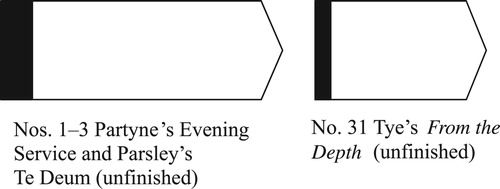

Phase I: the initiators

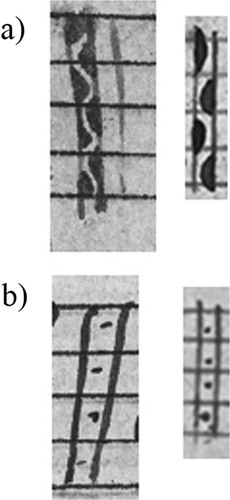

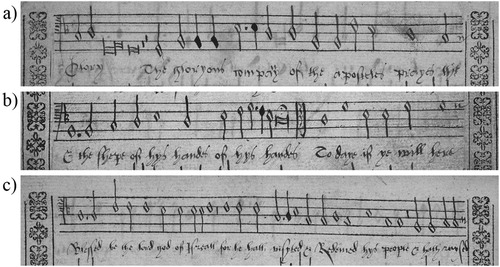

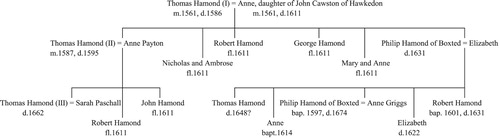

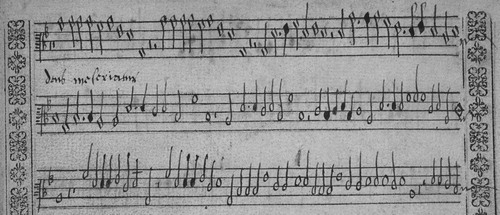

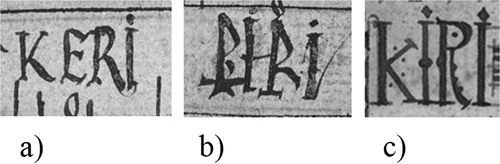

The first phase of copying was a short one (). It began with the copying of a Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis by R. Partyne, most of which has been lost due to missing pages. The principal music copyist used a flame-shaped notehead, but the bassus part was copied in a round script (see ).Footnote22 The two associated text hands are variations on a similar secretary script characterized by the use of thick, dark strokes for the ascending stroke of the ‘d’ and for descending strokes at the end of words for letters such as ‘n’, ‘s’ and ‘h’. The attribution (found only in the cantus and contratenor books) is in a significantly larger, more deliberate script. As this is the only point in the book where the attribution receives such treatment, one wonders whether one of the copyists was Partyne himself.

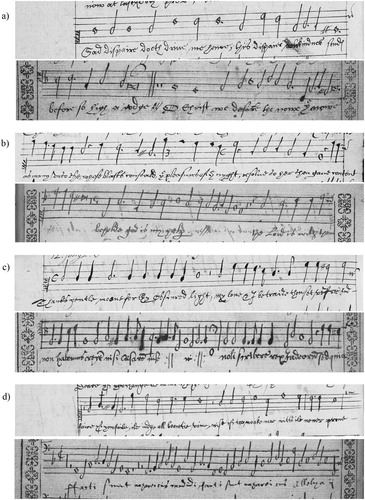

Image 1. Text and notation hands in Phase I. a) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 3v with flame-shaped noteheads; b) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30483, fol. 4r with round noteheads; both copying Partyne’s Magnificat. © British Library Board.

Example 1a–b. Variants in Christian/Sebastian Hollander’s Dum transisset in the manuscripts GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4, GB-Och: Mus. 979-83 (Baldwin Partbooks) and GB-WA: MS B. VI. 23 (Stonyhurst Partbooks); and the printed collections Liber primus cantionum sacrarum (Leuven, 1554, 1555) and Liber decimus ecclesiasticarum cantionum quinque vocum (Antwerp, 1555).

The partial copying of Osbert Parsley’s Te Deum in the flame-shaped hand reveals that the scribe worked by copying sections of music and text in tandem across all the partbooks simultaneously.Footnote23 Three partbooks contain both music and text up to a point in the phrase ‘To thee Cherubim, and Seraphim continually do cry’ (the end of a full page in the bassus and tenor), while the cantus part was much closer to completion with the text hand having proceeded further than the notation by a line.

The mid-section of the book was also started in this phase: in the contratenor book the scribe with the round hand counted off c.40 folios and began copying Christopher Tye’s From the Depth (though the flame-shaped hand soon took over). Like Parsley’s Te Deum, this piece was finished by the Phase II scribes.

Phase II: less-assured copyists

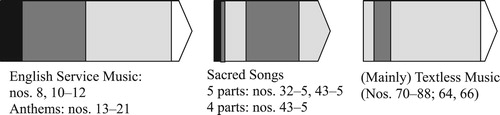

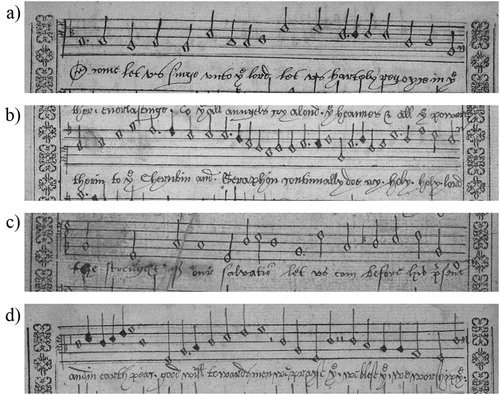

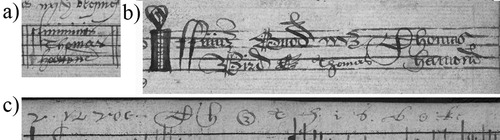

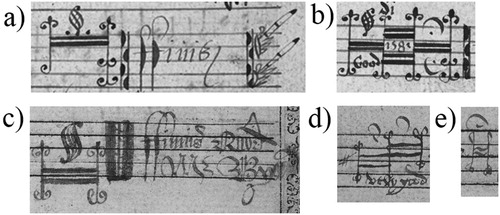

In the second phase ( – grey sections) the fluency of the opening music scribes is replaced by diamond hands whose awkwardness and inconsistency of shape suggest much less accomplished notators. Nearly all the Phase II scribes share the same basic angular diamond noteshape, with a narrow, upright diamond for notes with downwards stems, and a more elongated notehead for those with upward stems (see ). The notes are formed of strokes of even thickness (with one exception). The upward stems tend to be longer than the downward ones as the latter tend to stay within the span of the stave, and wobbliness in the stems is fairly common. Similarly the text scribes share the same model secretary script, the most obvious difference from the earlier phase being the lack of thickened strokes. The immaturity of the hands makes it difficult to determine how many copyists were at work as it is a matter of judgment how much variation to allow before one categorizes a hand as new. Cases where different hands are identified copying separate parts of the same piece (e.g. the end of Parsley’s Te Deum) or where a piece is copied in a distinctive hand from those on either side (e.g. the Venite) indicate that there was clearly more than one copyist involved. The number could be as high as six.

Figure 3. The second phase of copying in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-3. Phase II in dark grey (Phase I in black).

Image 2. A selection of the Phase II hands. a) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30482, fol. 2v, Osbert Parsley’s Te Deum; b) 30482, fol. 6r, Robert Adams’s Venite; c) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30482, fol. 7v, Anon., Benedictus. © British Library Board.

Having completed Parsley’s Te Deum and Tye’s From the Depth, these scribes separated their own additions from the previous work. Leaving a blank folio in all books, these scribes copied the additional canticles required for Morning Prayer (nos. 4–7 and 9). They also started a new middle section – skipping approximately five folios after Tye’s From the Depth to copy a mix of secular partsongs and contrafacta (nos. 36–42)Footnote24 – and started a third section of textless music towards the back with two Latin motets by British composers (nos. 67–8).

As well as the less assured notation hands, a further indication of a lack of competence among these scribes is that they failed to realize that Adams’s Venite was a three-part piece and copied a part from an unrelated anonymous Venite into 30481.Footnote25 Either the scribe was copying from a collection of loose sheets into which the extraneous contratenor part had mistakenly been mixed in, or else he was copying from another set of partbooks containing multiple Venites in which he mistakenly assumed that turning to the first example in each book would provide the correct parts. There are also a few short passages of copying that seem to be the work of even less experienced scribes in an ill-formed, wobbly round hand (see ‘Educational Use’ later in this article).

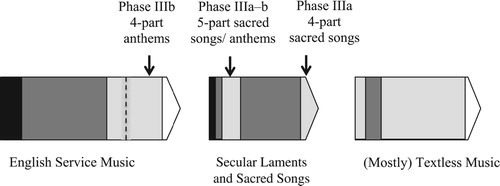

Phase III and the addition of the fifth book

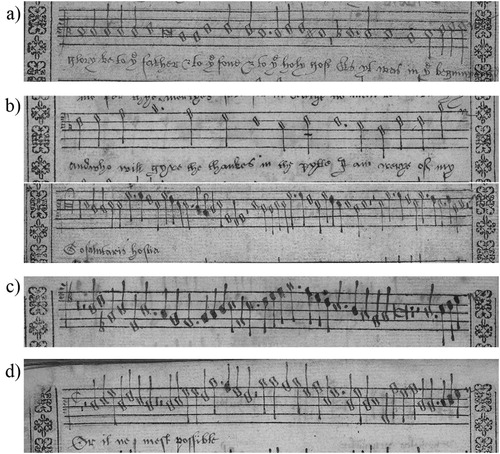

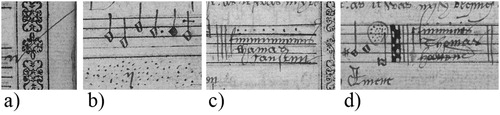

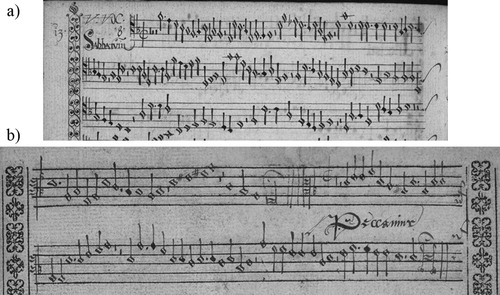

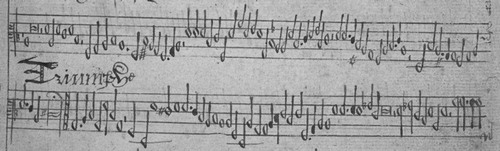

The transition from Phases II to Phase III ( – pale grey sections) is seen in Tye’s O God be Merciful, where in 30482 the first of the Phase III scribes takes over on fol. 16v. Soon after the transition there is a marked change of ink to a distinctly paler brown.Footnote26 The Phase III hands (see ) are generally characterized by oblong diamond noteheads, longer stems (with some subtle and intermittent clubbing on the downward stems in some cases), and a neater and more consistent appearance. There are similarities with the upward-stemmed notes of the Phase II hands, but the more elongated and angled heads on the downward-stemmed notes are distinctive. Nevertheless the later Phase II hands were moving closer to the Phase III shape, and a distinctive thick, black barline with a white snake through the middle is shared between both phases.Footnote27 It is possible that these hands represent the more mature style of scribes from Phase II. A similar secretary script continues to be the model text hand, but like the notation hands, these now tend to be neater, with less extravagant descenders and more care to avoid collisions with the notation and stave than most of the Phase I and II scribes.

Figure 4. The third phase of copying in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4. Phase III in pale grey (Phase I in black; Phase II in dark grey).

Image 3. A selection of the Phase III hands. Phase IIIa: a) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 20v, Robert Adams's, Nunc Dimittis; b) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 62v, Christopher Tye’s O Lord Rebuke Me Not and fol. 79r, Anon., ‘Non neamo’. Phase IIIb: c) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 75v, Osbert Parsley’s Clock; d) GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 90v, Jacobus Clemens non Papa, Or il ne m’est possible. © British Library Board.

Around the transitional point between Phases II and III there are also a few isolated hands using square-diamond noteheads that contribute to the copying of the anonymous In nomine (no. 69) and Tallis’s Wipe Away. Later in the phase further square-diamond hands contribute to Tye’s My Trust (30480) and Tye’s I Have Loved (30481). These scribes were perhaps external to the usual copying community, and were responsible for bringing these particular pieces to the 30480-4 repertory.

As well as continuing to add to both the opening service music and the middle section of sacred songs, this phase saw the creation of the fifth partbook. This addition primarily facilitated the development of the textless section, although a handful of five-part anthems were also included. A series of seven items, beginning with an anonymous and untitled piece (no. 70), were copied predominantly by a single hand with a consistency that suggests they were copied over a short period. Yet although this copying stint seems to have been the initiating factor for creating a fifth book, these pieces may not have been the first five-part music to be copied.

William More’s Levavi has several unusual features that may suggest that it is missing a fifth part. There are numerous instances of thin textures with bare octaves, unisons or fifths (particularly at cadences), as well as static passages and unsupported upper voice duets, which might suggest missing entries of a fifth voice.Footnote28 While it is possible that the scribes of 30480-3 copied the piece unaware that it was missing a part, the missing part may also have been copied on a loose sheet, or onto pages now missing from 30484.Footnote29 Indeed Levavi might have appeared on the connecting folio to the damaged fol. 20, which also contains a second copy of the first five-part textless piece copied in Phase III (the anonymous and untitled no. 70, also found on fol. 12r). If that were the case then this half folio might represent a loose bifolium that pre-dated the fifth partbook before the need for a full extra book had become apparent.Footnote30

A disruption to the copying seems to have occurred in the middle of Phase III, after which the notation hands become noticeably larger and less angular. The transitional point is marked by the brief appearance of one particular text scribe who makes contributions to Whitbroke’s Magnificat, Tye’s O Lord Rebuke Me Not, and Hollander’s Dum transisset in each of the three sections.Footnote31 The impression of a break is given by the unfinished copying of Tye’s psalm in both 30480 and 30481. At this stage the initial span of service music was complete, just two of the five-part anthems had been copied, and the five-part textless music had progressed as far as Hollander’s Dum transisset.

Both the four-part anthems that follow Whitbroke’s Magnificat and the final two five-part anthems (which are also separated from the earlier two by a blank folio in 30480) are copied by hands that are bigger, thicker and curvier than those earlier in the phase, though still sharing the same basic shape. Copying also becomes particularly collaborative with no easy relationship between text and music scribes. In the textless section, smaller hands add a couple more pieces, but from Clemens’s Or il ne m’est possible onwards larger hands have again taken over the copying.

One of the latest hands to appear has more exaggerated clubbing on the stems, which also tend to slant to the left when pointing upwards (see c). This identifiable hand indicates that Byrd’s Precamur and Parsley’s Clock were added to the beginning of the textless section after Si je me plains and A che cerchar had been copied at its end.Footnote32 This arrangement came about because the end of the printed staves had been reached in the bassus partbook. In order to copy the pieces in comparable locations in all partbooks the scribe chose to copy them before the existing textless music, a choice that also placed these two cantus firmus pieces as close as possible to the existing In nomine.

Phase IV: a master and his choirboys?

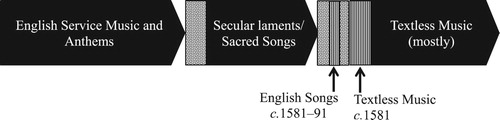

The fourth set of scribes are less a distinctive phase in the copying process than a specific group of copyists that start contributing alongside the scribes in Phase IIIb. This group generally uses smaller and squarer noteheads. Their main contribution is the parts of Thomas Causton’s service from John Day’s 1565 print Certain Notes / Morning and Evening Prayer (nos. 22–26), but some members of this group can be identified as collaborators earlier in the liturgical section and also adding to the textless music (loosely represented by the white sections in ). This group consists of one more mature hand and numerous awkwardly proportioned, wobbly and/or irregularly shaped hands. In light of the other evidence of choirboys being associated with these partbooks that will be set out later, this group may represent the Master of the Choristers and his choirboys.

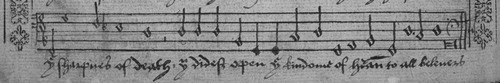

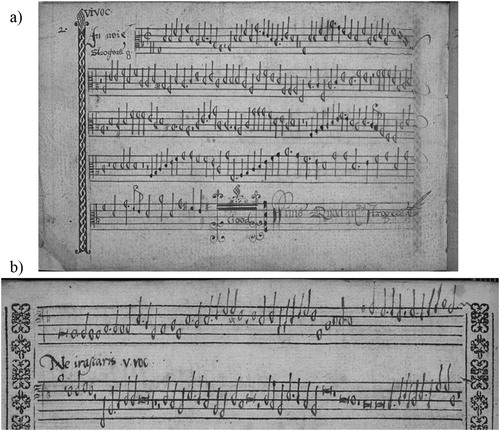

The notation hand of my proposed master is small with squeezed diamond-headed notes (see ). The highly collaborative copying in this phase makes it tricky to draw connections between the text and notation hands, but in this case the similarities between the noteheads and the angular lobes of certain letters (most obviously the ‘d’s) and the distinctiveness of both from other text and music hands in this section make me confident that these are the work of the same scribe.

Image 4. The mature hand in Phase IV, GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30483, fol. 36v, Thomas Causton’s Te Deum. © British Library Board.

Yet it is not so much the style of the hand, but rather its behaviour that indicates that this person may be the master. This scribe appears to have a controlling role in the copying, with a tendency to write texts and perhaps the first few notes of a piece or section, but leave others to finish them. He takes this role in the bassus part of White’s O Praise God and Clemens non Papa’s Or il ne m’est possible, and for several of the vocal parts of Sheppard’s Christ Rising and I Give You a New Commandment, Feryng’s O Merciful Father and the anonymous In Judgment Lord. Moreover, his only sustained period of copying both text and music is in the bassus partbook (during the copying of Causton’s service).

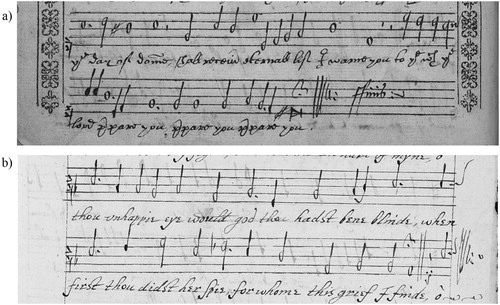

The novice copyists of this phase primarily contribute to copying parts of Causton’s ‘Service for Children’. At least eight notation scribes in addition to my proposed ‘master’ hand worked on copying Causton’s music, many across several partbooks (see ). The awkwardness of many of the notation hands suggests a group of young, inexperienced copyists. Their lack of experience shows itself in various different ways: wobbly or irregular stems, awkward proportions with stumpy or exaggeratedly long stems and very small noteheads; noteheads that are either misshapen or inconsistent, or hybrid diamond noteshapes that verge on becoming round. Several seem to be attempting a small diamond form similar to the ‘master’ hand. One of these inexperienced copyists unthinkingly copied features of the print – using a line over or under notes in the spaces above and below the stave – without the knowledge or foresight to discard such features as unnecessary. There are also several features that appear childish (): dotting around ditto marks, pauses or capitals, exaggerated directs, and several cases of an extended ‘fininininines’ (e.g. 30480. fol. 36v). There is even a cheeky substitution of the composer’s name for that of the copyist (30483. fol. 39v), Thomas Hamond (not the man who owned the books in 1615, but probably a relative, as discussed later). It is plausible that these copyists were the choirboys learning to write musical notation.

Figure 6. Family Tree of the Hamonds of Hawkedon. Adapted from J.J. Muskett, ed., Suffolk Manorial Families, Being the County Visitations and Other Pedigrees (Exeter, 1900), i, 261.

Image 5. A selection of Phase IV novice hands. a) 30482, fol. 31r; b) 30480, fol. 33r; c) 30483, fol. 33v; d) 30481, fol. 39v. © British Library Board.

Image 6. Childish features in the Phase IV hands in Thomas Causton’s Service for Children. a) extended directs: 30482, fol. 32r; b) dotted ditto marks; 30482, fol. 34v; c) extended ‘fininininininis’: 30480, fol. 36v; d) dotted pause, extended ‘finininis’ and substitution of ‘Hamond’ for ‘Causton’: 30483, fol. 39v. © British Library Board.

A couple of the scribes copying Causton’s service also made contributions at the end of the textless music section. The scribe with the squat noteheads finished off A che cerchar in the cantus partbooks (30480, fol. 86v), while the scribe with the tiny noteheads and very long stems copied O Lord Turn Not Away Your Face. Having now reached the end of the printed staves in the bassus partbook (indeed a hand-ruled page had already been needed for O Lord Turn Not), the original layer of copying ended.

The beginning of infill copying between the sections coincided with the first clean break in the procession of scribal hands, as well as a change in reportorial focus. Two phases of infill copying can be identified. The beginning of the first (Phase V) can be dated to the early 1580s by association with another partbook GB-Lbl: Add. MS 47844 and marks a shift to a more domestic and recreational context. The second stage of infilling (Phase VI) took place in the 1590s or early 1600s. These phases shall be explored further later, after first considering the origins and initial functions of these partbooks.

Liturgical use

Canticles

Having established the chronology of compilation in the original layer it is possible to draw conclusions about the intended use of the collection. The opening section of English service music provides the canticles for both Morning and Evening Prayer, suggesting that the partbooks originally had a liturgical function (see ). The Phase I scribes provided Partyne’s Evening Service and began the copying of Parsley’s Morning Service. Although Partyne’s Evening Service is now incomplete, enough of the Magnificat (particularly the doxology) survives to give an impression of its style. Alternating passages of homophony and close spaced imitation in a strictly syllabic setting with only a short ‘Amen’, it is neither in the most austere post-Reformation style nor the more elaborate. The setting would not be demanding for reasonably competent singers. Parsley’s Te Deum was a somewhat more complex piece than Partyne’s with its predominantly polyphonic texture and more limited use of homophonic declamation, but still requiring no exceptional competency.

Table IV. The opening group of canticles for Morning and Evening Prayer in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-3.

This initial scheme was interrupted as copying passed to the Phase II scribes. Though they continued to copy music for Morning Prayer, rather than proceeding to the Benedictus that accompanied Parsley’s Te Deum, first they added a Venite (which liturgically speaking should have preceded the Te Deum) and an anonymous Benedictus. These less competent scribes chose Adams’s three-voice ‘Venite’, but seem not to have had a good grasp of what they were copying as they included a fourth part from another unidentified Venite in 30481 (see ‘Phase II’). Having covered the most common canticles the scribes then added Tye’s Deus Misereatur (an alternative to the Nunc Dimittis during Evening Prayer) and a Jubilate (an alternative to the Benedictus in Morning Prayer). The Phase II scribes finished off with some further items for Evening Prayer by Adams, Tye and Whitbroke.

The services fall into two groups: canticles with upper parts in C1/2 clefs, and overall ranges of two and half octaves or more would be most suitable for a choir with boys.Footnote33 Other pieces with a narrower range (shaded in ) could have been performed by a choir of only adult male voices. The latter group typically use a C3 clef for the upper part, while those that use C2 are notated with a higher range across all parts and can therefore be transposed to an equivalent pitch to the other pieces of narrower range. The main span of service music ended with Whitbroke’s Magnificat, at which point there was sufficient repertory for both a choir with boys and an all-adult choir to provide the major musical elements for Morning and Evening Prayer, though the choice of repertory was somewhat limited. Notably there was no music for Communion. Only with the later copying of Thomas Causton’s ‘Service for Children’ (as designated in Day’s Morning and Evening Prayer, 1565) was a Gloria included, and this seems to have been used more as a copying exercise for novice scribes (see, ‘Educational Use’).

Anthems?

At the same time as the service music, further sacred songs were being copied in the mid-section of the manuscripts. Whether these were intended as anthems to be used in services seems to depend on where and when they were copied. The Phase I scribes’ choice of Tye’s From the Depth is ambiguous. As one of the penitential psalms, this text was popular in both private and collective penitential devotions. The psalm had been part of the Catholic funeral rite and despite having no specific liturgical role in the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer its associations with death and mourning remained, with Protestant authorities complaining at its continued use at funerals.Footnote34

The second group of scribes left a clear gap after this psalm, restarting the mid-section and adding a more mixed group of songs. The section begins with a secular partsong – Tallis’s When Shall My Sorrowful Sighing Slake – with Johnson’s Defiled is My Name following four songs later (shaded in ). The melancholy tone of these partsongs resonates with the penitential tone of several of the sacred songs that accompany them: Tallis’s Purge Me O Lord; the anonymous (Deliver us Lord) Both Night and Day; and Tye’s Deliver us Good Lord.

Table V. The sacred songs and secular laments added to the mid-section of GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-3 in Phase II.

Moreover, a significant proportion of these pieces are contrafacta, two of secular songs: Sheppard’s I Will Give Thanks is a contrafact of O Happy Dames; and Tallis’s Purge Me O Lord shares its music with Fond Youth is Bubble. The juxtaposition of secular consort songs and contrafacts on tunes with secular connotations is suggestive. In the case of Purge Me the sacred song may pre-date the secular, whose text appears a worse fit to the melody;Footnote35 however, this may have been unknown to the scribes of 30480-4 as they seem to have deliberately placed these two contrafacts alongside secular partsongs, and a third contrafact – (Deliver us Lord) Both Night and Day – that translates an old Sarum antiphon for Trinity Sunday, Libera nos, salva nos, with a chant tenor. There is no reason why the sacred songs here could not have been used as anthems, but their separation from the earlier psalm and their mixing with secular songs suggests that the Phase II scribes did not envisage them as such.

In Phase III sacred songs were added in three different places (). First Phase IIIa scribes added a few four-part sacred songs at the end of the mid-section (). These were a mixed bunch including a contrafact on a composite text and two psalms, one of which includes the doxology and both of which had had liturgical purposes in the past (but not in the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer). The five-part songs seem to have been copied during both halves of Phase III, with the two pairs separated by a page of blank staves in 30481. Of these the latter pair appear designed for liturgical use as both include the doxology and Tye’s My Trust O Lord is explicitly labelled as an ‘anthem’ (30480, fol. 45r). This is not the case with the earlier pair, and Tallis’s Wipe Away My Sins has no biblical or liturgical origins.

Table VI. The sacred songs / anthems added during Phase III.

The final group (nos. 13–20) was inserted after the service music during Phase IIIb. The copyists seem to have deliberately distinguished this group from the four-part sacred songs already copied in the mid-section of the manuscript, after which there were at least 13 blank folios still available in each partbook. The deliberate placing of this repertory next to the liturgical music implies that it was intended for use in services. This is born out by the pieces chosen, which include psalms and canticles appointed for Easter Day and an Offertory sentence from the Communion service (). Until the later copying of Causton’s Gloria there was no other provision for Communion music; however, the Offertory would have been the penultimate act in a so-called ‘Dry Communion’ without the sacrament, which typically followed Morning Prayer (it being typical in many parishes to receive the sacrament just once a year at Easter).Footnote36 The psalms included here all had specific liturgical uses in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, and one ends with the doxology. Anthems of praise are also common as specified in the Elizabethan injunctions of 1559 (a ‘hymn, or suchlike song to the praise of Almighty God’), for which Praise ye the Lord and O Praise God in His Holiness were clearly appropriate.Footnote37

Also suggestive is the use of the collective ‘we’ for virtually all the anthem texts in this group. Indeed for In Judgment Lord the text appears to have been deliberately altered to the collective pronoun (differing from the first person singular found in the Edwardian Wanley booksFootnote38) with traces of the alteration visible in an error in the cantus partbook where both ‘me’ and ‘us’ appear side by side on fol. 30v (line 2). Feryng’s O Merciful Father uses a text that I have not been able to trace, but which weaves together various commonplaces of liturgical language. The text has similarities with the kind of occasional prayers published for special services in times of need during in Elizabeth’s reign.Footnote39 Feryng’s text calls for God’s deliverance from enemies and points specifically to the suffering of the poor, and the second part draws particularly on phrases from the Magnificat and Lord’s Prayer (underlined):

O merciful Father, we beseech thee be not from us is time of necessity lest you forget us and the ungodly work their will against us, for then shall the poor suffer great misery.

O God, confound the proud imagination of the sinful creatures that thy name may be glorified here in earth as it is in heaven. Help us, God our saviour, and deliver us from all evil. Amen.Footnote40

Finally, this group of anthems is the only one to be carefully divided into two groups according to clefs and ranges, akin to the service music they follow, only more precisely ordered (). The sacred songs in the mid-section of the manuscripts are wide in range (2.5–3 octaves), with several using G2 clefs for the upper part or even requiring two high voices in G2 or C1 clefs (the only exception is the unfinished O Lord Rebuke Me Not). The group following the service music, however, is carefully divided: the range of the first three suggests the use of means, while the narrower ranges and use of C3/4 clefs in the upper voices mean that the latter five (shaded in ) are performable by men’s voices alone. Indeed White’s O Praise God clearly differentiates between the abilities of those taking the mean part and the men’s voices at the phrase ‘praise him in the cymbals and dances’. Whereas the bassus and tenor illustrated the dance with long melismas of running semi-minims, the contratenor has a simpler melisma, and the upper part none at all.Footnote41

Table VII. Four-part anthems added to the service music section during Phase IIIb.

The overall picture that emerges is that while provision was made for the canticles necessary for Morning and Evening Prayer early in the copying process, providing anthems was less of a priority. Only with the Phase IIIb scribes is there a clear effort to form a collection of anthems, perhaps reflecting the fact that the singing of anthems was nowhere mentioned in the Book of Common Prayer. They were not required musical items from a liturgical perspective.Footnote42 Even in Elizabeth’s 1559 injunctions the singing of a ‘hymn, or suchlike song to the praise of Almighty God, in the best sort of melody and music’ before or after Morning or Evening Prayer was only ‘permitted’.Footnote43

The provision of canticles for Morning and Evening Prayer was also limited and would have permitted little variation save between the use of boys or an all-adult choir. Beyond Tye’s setting of an Offertory sentence there was no Communion music until the late inclusion of Causton’s Gloria, and even here the scribes copied only the movement in which the rubric of the Book of Common Prayer explicitly offered the option of singing, omitting the rest of Causton’s Communion music.Footnote44 As most churches celebrated Communion only once per year, the acquisition of Communion music may not have been a particular priority.Footnote45

Finally, having dated the music paper to c.1570 (see earlier, ‘Physical Description’) it is striking that much of the repertory copied was several decades old (see ). Even a decade or more into Elizabeth’s reign, late Henrician and Edwardian music was still staple repertory for the liturgical institution in which these books were originally copied and used.

Table VIII. Henrician and Edwardian repertory in the sacred music sections of GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4.

Educational use

Liturgical music formed only one part of the repertory being copied at this time. Not only did the songs added to the mid-section of the manuscript in Phase II and IIIa have a looser devotional purpose, but a further large section of predominantly textless music was being added concurrently at the back. As a proportion of service music and anthems required the use of choirboys, this diverse collection of materials may relate to their training. Retaining a group of choirboys required not only the provision of music for them to sing in services, but a key part of the duties of a Master of Choristers was also to provide for both their wider moral and musical education.

Several of the songs from the mid-section might have provided moral instruction through music. One specifically aimed at young men was Bulman’s Lord Thou Hast Commanded by thy Holy Apostle. The text is a prayer for chastity written by Thomas Becon (a Reformist preacher originally from the Norwich diocese), which appeared in both the 1553 Primer and numerous editions of The Pomander of Prayer from 1558–78 labelled as a prayer ‘of single men’.Footnote46 None of these editions is identical with the anthem text, however, as the reference to whoredom has been removed:

I beseech thee to give me grace to behave myself according to this thy holy commandment, that in this [th]e time of my single life, I defile not my body w[ith] [Becon: whoredom or any other] no uncleanness.

Both When Shall My Sorrowful Sighing Slake and Defiled is My Name have concordances with another early Elizabethan manuscript that has been associated with the education of choristers. Jane Flynn has argued that GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30513 (the Mulliner book) reflects Thomas Mulliner’s training as a chorister, particularly after his voice had broken, in preparation for a future career in music.Footnote49 In addition to arrangements of secular songs, the Mulliner book also contains organ pieces on cantus firmi, and both excerpts and transcriptions of a range of musical genres from pre-Reformation motets to newer imitative genres. As well as providing material for learning to play the organ, Flynn argues that these pieces served as compositional models, while some anonymous examples may be exercises by Mulliner himself.Footnote50

Nor is the Mulliner book the only other Elizabethan collection of textless music to have been associated with the training of choirboys. GB-Lbl Add. MS 31390 is a large tablebook from c.1578, titled ‘A book of In nomines & other solfa-ing songs of v: vi: vii: & viii: p[ar]ts for voices or instruments’. As the title suggests, the pieces were to been sung using sol-fa syllables and played on instruments. The manuscript includes a chart for learning note values and mensuration (fol. 127v), as well as pieces that – like those in the Mulliner book – might be studied as compositional exemplars, or be student pieces modelled on Taverner’s In nomine.Footnote51

The 30480-4 partbooks have similarities with 31390 in their extensive collection of textless chansons and Latin motets, though the partbooks have fewer In nomines or similar pieces based on a cantus firmus. There are also no obvious training aids as in 31390, but the repertory in 30480-4 does exemplify nearly all the main polyphonic styles of the period: Latin motets, chansons, madrigals, a metrical psalm, consort songs, and pieces based on cantus firmi (complementing the service music and English anthems in the earlier section). This has parallels with the collecting of varied polyphonic models Flynn identified in the Mulliner book. Rather than providing a beginner’s repertory to prepare boys for singing the service music, this repertory in 30480-4 (especially the Latin motets) is often more complex than the modest liturgical polyphony and seems designed instead to stretch the abilities and broaden the musical experience of the singers.

Unlike the flexible forces designated for 31390, the textless section in 30480-4 would have been awkward for viol players as a significant number of pieces contain page turns.Footnote52 This is true even of many of the shorter pieces and there are cases where less than a line of music extends over the page turn that could easily have been fitted on the previous page should the scribe have wished to do so. This probably suggests that the repertory was intended to be sung sol-fa, such that Thomas Morley’s criticisms of singers of motets ‘leaving out the ditty and singing only the bare note, as it were a music made only for instruments’ would be applicable to the singers using 30480-4.Footnote53 Although several of the Latin motets and chansons do preserve the text in the bassus part, this cannot reflect performance practice. Rather it suggests that the scribes wished to keep a record of the original text despite not requiring it for performance, with the bassus book chosen as the one used by the Master of the Choristers. Significantly the three textless pieces not derived from songs – the In nomine, Parsley’s Clock and Byrd’s Precamur – do all fit on a page or opening and could have been performed on instruments without difficulty.

Several specific pieces also hint at this being a didactic repertory. Two versions of D’ung nouveau dart are copied adjacently. One is by Philip van Wilder, and the other is a rearrangement of the piece that condenses its material, reorders the imitative entries and adds a newly elaborated ending. As the upper voice is simplified and always enters last, Jane Bernstein suggests that this represents the remodelling of the chanson into a consort song.Footnote54 Were these two versions perhaps copied for the purpose of studying processes of contrapuntal rearrangement, or comparing different kinds of imitative textures and structures? Or perhaps the anonymous rearrangement itself is a student work? Parsley’s Clock might also be a suitable piece for study due to the peculiar constraints of its cantus firmus: an ascending and then descending hexachord on ‘F’ whose rhythms are governed by a clock (30482, fol. 70v) whose hours determine the length in semibreves assigned to each pitch. In the ascending hexachord the cantus firmus strikes the hours 6 to 11. The descending hexachord rather oddly strikes the hours 1 to 4 and then 12.Footnote55

Unique to 30480-4 is the role these books seem to have had in training the choristers as music copyists. The largest project undertaken by novice copyists was the extracts of Thomas Causton’s ‘Service for Children’ from John Day’s 1565 print Certain Notes / Morning and Evening Prayer (nos. 22–26). Indeed so many hands are at work that the labour may even have been a specific copying exercise (see ‘Phase IV’), especially given the difficulties in performing the service due to Day’s inaccurate printing. Despite visible efforts to correct the errors in the print with alterations or additions, rhythmically significant errors remain and the service would not be straightforward to perform in its current state.

Nevertheless the copying of Day’s service was only one of many copying projects associated with inexperienced or novice copyists. The awkward and wobbly hands of the Phase II scribes already suggest a lack of experience, but on several occasions their work is punctuated by short passages by scribes who appear to be beginners. Such passages occur in Adams’s Venite (30482, fol. 7r, stave 2), Tye’s From the Depth (30483, fol. 47r, staves 1–2) and Johnson’s Deus Misereatur (30481, fol. 76r, staves 2–3). In , for example, the beginner scribe takes over from the fifth note of the top line and attempts to imitate the preceding diamond hand. Managing only wobbly stems and inconsistent diamond shapes, the beginner soon slips into an easier round hand and is allowed to complete two staves before the primary scribe resumes.

Figure 7. Placement of the first infill copying (Phase V) in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4. Original layer in black; Phase V, first layer of infill (c.1581–91) is striped; Phase VI, second layer of infill (1590s–1600s) is dotted.

Image 7. A novice scribe contributing to the copying of Robert Johnson’s Deus misereatur, GB-Lbl: Add. MS 30481, fol. 76r. © British Library Board. The novice scribe takes over at the sixth note of line two. After initially attempting to imitate the preceding diamond noteshapes, the novice scribe reverts to a round hand after a few notes.

These small passages continue in Phase IIIb,Footnote56 but there are also whole parts given to less-than-competent scribes. The first half of Clemens non Papa’s Caecilia virgo in 30480 (fols 81v-82r) is one of these. The beginner is mostly attempting a diamond hand that occasionally slips back into round noteheads, while the stems are wobbly and slant in irregular directions.Footnote57 Another striking example is Si je me plains in 30484 (fol. 18v) in which the scribe tries to imitate the oblong diamond shapes used by other scribes, but consistently puts the stems so far to the left such that the notes appear to have been written backwards.Footnote58

Sources and concordances

Having demonstrated the potential liturgical and educational uses of the partbooks, the next question is where the scribes drew their repertory from. One of the striking features of the repertory in the original layer of 30480-4 is its lack of concordances with other manuscripts, especially near-contemporary sources (see ). Among the service music and sacred songs, none of the music copied by the Phase I scribes has any concordances, and of the 15 texted pieces copied in Phase II, only four have sixteenth-century concordances.Footnote59 In Phases III and IV the four-part repertory continues to have many unique or nearly unique songs. Only the five-part anthems seem to have circulated more widely, though Tye’s My Trust O Lord remains exclusive to 30480-4.

The only close connection is with the Wanley partbooks (GB-Ob: Mus. Sch. e. 420-2). The Wanley partbooks are an earlier liturgical collection (1549–52), larger in scope than 30480-4, and making significant provision for Communion. Le Huray suggested that they originated in either a private chapel or a parish church, while Wrightson favoured a public institution undertaking a full range of services, possibly in London based on the bindings and the (admittedly few) named composers.Footnote60 Tye’s Nunc Dimittis, Sheppard’s I Give You a New Commandment and the anonymous In Judgment Lord occur in close succession in both sets, while Whitbroke’s Magnificat is another concordance (see ). Yet substantial differences between the two versions of In Judgment and the fact that these pieces are attributed in 30480-4 but not in Wanley, negates the possibility of direct transmission.Footnote61 There may, however, be some broader regional connection that accounts for the circulation of these pieces in close proximity in both manuscripts.

Table IX. The position of concordances between GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4 and the Wanley partbooks (GB-Ob: Mus. Sch. e. 420-2).

Among the textless music, concordances with English sources are similarly limited. While the motets by English composers all have several concordances and appear to have circulated widely, both the consort song Without Redress and the harmonized metrical psalm O Lord Turn Not Away are unique. D’ung nouveau dart by Philip van Wilder (musician at the English royal court c.1525 until his death in 1553) has only a single concordance and the majority of the chansons are anonymous with no known concordances. Of the foreign motets, chansons and madrigals whose sources can be traced, only two are found in other English manuscripts.Footnote62 Several, however, can be found in prints that date from c.1547–56. These examples offer insight into the networks through which the copyists of 30480-4 had access to music and the circulation of continental music in early Elizabethan England.

There are six pieces with identified concordances with foreign prints (see ). The first of these, Crecquillon’s Cor mundum, appeared in five different prints between 1547 and 1559. The version in Hamond is a near-exact match – barring one minor copying error – with the Liber quartus sacrarum cantionum printed by Susato in 1547. Similarly the copy of De Rore’s Quel foco che also appears to be closely derived from print. The piece appeared in four distinct publications, of which de Rore’s, Il primo libro de madrigali, had a particularly large number of editions made by four different Venetian printers.Footnote63 The version in 30480-4 was most probably copied from one of these editions of Il primo libro or else the slightly earlier Madrigali de la fama.Footnote64

Table X. Printed concordances for textless music in GB-Lbl: Add. MSS 30480-4.

Both Crecquillon’s motet and de Rore’s madrigal are close enough copies to be directly transcribed from the print, or at least very closely derived from it. The picture is more complex for other pieces. Caecilia virgo is closest to the Liber quartus (1547) and Tertia pars magni operis (1559), but minor rhythmic variations mean that neither is a precise match. The balance of evidence tilts slightly towards Susato’s Liber quartus as the source, but unlike the copying of Crecquillon’s Cor mundum from this publication, Caecilia virgo seems to have had a less direct path of transmission via an intervening manuscript. Nor is this the only case where variants seem to indicate that the Hamond partbooks’ relationship with the potential printed concordances was indirect. Clemens non Papa’s Or il ne m’est possible similarly has substantial rhythmic variations in the cantus compared with the only printed concordance (see ).

There is, however, another concordance for Clemens’s chanson in two partbooks preserved in Stonyhurst College, Whalley in Lancashire, dated 1552 (GB-WA: MS B. VI. 23). They were originally part of an eight-book set containing c.120 pieces scored for 2, 3, 5 to 8, and 12 voices. (It is likely that the set also contained four-voices works not preserved in the extant books). As the repertory was predominantly chansons and motets by composers associated with the Habsburg courts or from the Low Countries, the partbooks were believed to have originated at the imperial court of Charles V and come to England via the Jesuit College only in the late eighteenth century.Footnote65 Yet Martin Ham has recently argued that the Stonyhurst partbooks are identical with those described as belonging to the Tudor musician Walter Earle by the eighteenth-century antiquarian John Immyns.Footnote66 Walter Earle had been in royal service since at least 1541 when he was a page in the Queen’s chamber. He continued as a gentleman in Catherine Parr’s household and then served in the privy chambers of Edward VI and Mary I before retiring shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I. He is known to have been a virginal player and also the composer of a motet, as well as possibly a pavan given his name.Footnote67 Ham suggests that these partbooks were a presentation set produced as a diplomatic gift from Charles V to Edward VI, which were later dispensed with by the crown and passed to Earle as a loyal, musical servant.Footnote68

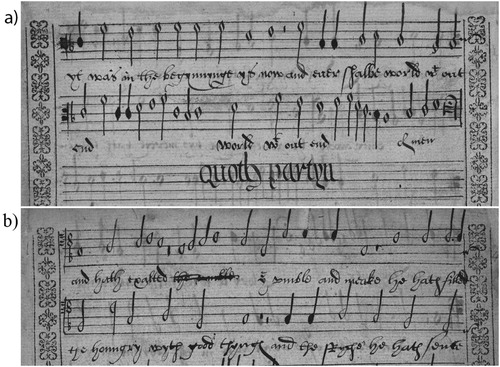

There are three concordances between 30480-4 and the five-voice section of the Stonyhurst partbooks; however, as the five-voice repertory is included in just one of the extant partbooks the scope for comparison is limited. In the case of Clemens’s Or il ne m’est possible the rhythmic variations occur in parts lost from the Stonyhurst set so no firm conclusions can be drawn. For the two motets by Hollander and Clemens the evidence is more suggestive.

Hollander’s Dum transisset and Clemens non Papa’s Venit vox occur adjacently (though reversed) in both 30480-4 and the Liber primus cantionum sacrarum (Leuven, 1554 and 1555). Yet close comparison reveals some small but significant variations between the publication and 30480-4 in both cases. Nor do the other printed concordances (see ) offer a better match.Footnote69 One of the variations in Venit vox concerns the rhythm of the final phrase in 30481, which is a match with the Stonyhurst partbook where different text underlay creates a rhythmic variation from the print. This alone would not be sufficient to connect 30480-4 with the Stonyhurst partbooks, but a similar link occurs with Hollander’s Dum transisset.

For Hollander’s Dum transisset there are again multiple concordances with printed sources with varying attributions (see ), but the 30480-4 version contains a number of small variants not found in any print. These include additional notes at the end of 30481 and the end of the prima pars in 30482, and two small but significant rhythmic variations in 30480-1 (see ).

Looking beyond print, Hollander’s Dum transisset was one of the most widely copied foreign motets in Tudor manuscripts. The first manuscript concordance is the tablebook 31390, which contains the prima pars of Hollander’s motet on fols 90v–91r, attributed again to Sebastian. This version is distinct from all the prints – more so than 30480-4 – using ligatures throughout and containing numerous minor rhythmic variants. The second concordance is with GB-CF: D-DP-Z6-2, a partbook found in Essex Record Office which belonged to John Petre (his name is on the cover) and which may have been a gift from the Paston family, c.1590.Footnote70 This includes just the prima pars (attributed to Sebastian) on fols 4v–5r, and is clearly copied from one of the editions of Phalese’s Liber primus cantionum sacrarum. The Petre partbook contains several more pieces from Phaleses’s collection and although there are a few differences in text underlay (resulting in rhythmic variants), in many cases the scribe has better solutions than the print.Footnote71 The reading in this manuscript therefore differs substantially from 30480-4. More significant, however, is the complete version of Dum transisset that appears in John Baldwin’s partbooks, GB-Och: Mus. 979-83, where it is erroneously attributed to ‘Mr Orlandus’. The set is missing the tenor, but of the three 30480-4 significant variants, two of them occur in Baldwin's copy.

The first variant is a small detail (a). All the printed exempla have two semibreves in the section marked with the brackets. Baldwin's version (Mus. 979, 43) gives the same dotted rhythm variant as in 30480 (fol. 80v). The second is a little more substantial (b). Of the prints, the Antwerp edition is the closest match to 30481 (fol. 85v), but only Baldwin matches both bracketed sections (Mus. 981, 48). Moreover, this part survives in the Stonyhurst set, and it too contains this variant (quinta partbook, fol. 100r). It is likely therefore that both the copies of Baldwin and 30480-4 stem from the Stonyhurst version. Neither, however, can have been copied directly. Aside from some minor rhythmic variants, Baldwin erroneously attributes the piece to ‘Orlandus’, while in the Stonyhurst partbooks the name ‘Christianus Hollander’ is clearly written at the start. Similarly there is an extra note at the end in 30481 that does not appear in the Stonyhurst set. The most likely explanation for this extra note (and another at the end of the prima pars in 30482) is that an intervening manuscript had made alterations to the final chord, which the scribes in 30481-2 misread as indicating two successive notes. Such an alteration occurs neither in the Stonyhurst nor the Baldwin partbooks (which in any case has several other rhythmic variants that make a direct concordance unlikely).

With Clemens’s Venit vox and Hollander’s Dum transisset both showing variants in common with the Stonyhurst partbooks, it is likely that the unexplained differences in Clemens’s Or il ne m’est possible are also derived from lost parts of this manuscript. It is even possible that Clemens’s Caecilia virgo (which follows Dum transisset) was copied from the lost, four-voice section in the Stonyhurst set.

The copyists of 30480-4 therefore had access to continental printed books that included the Liber quartus sacrarum cantionum (1547) printed by Susato and an edition of de Rore’s Il primo libro de madrigali or the Madrigali de la fama (1548), as well as access to material that stemmed from the Stonyhurst partbooks (in Phase III). Alongside More’s Levavi occulos copied in Phase II, this illustrates that the scribes had access to music and manuscripts connected with figures at the heart of the English court – the privy chamber – but probably not at first-hand. Walter Earle had retired from court life in 1558 and returned to Dorset (where he died in November 1581), but there is little to connect 30480-4 to that part of the country.Footnote72 Given Baldwin was also copying a version of Hollander’s motet derived from the Stonyhurst partbooks in the mid-to-late 1570s, it is likely that copies of some of these pieces remained in the vicinity of the court even after the manuscript passed to Earle (presumably before he left court). In any case, the foreign printed and manuscript music that the 30480-4 scribes had access to – whether directly or indirectly – was not recent music. As with much of the liturgical and sacred music, this was repertory that was already a couple of decades old.

The original institution for British Library Add. MSS 30480-4 and the English Reformation

These partbooks offer a unique insight into the repertory of one Protestant institution during the re-establishment of the Reformation in the early decades of Elizabeth’s reign. The picture is of an institution large enough to sustain choirboys as well as singing men, to make provision for their education, and to buy a large batch of music paper in one go. The institution was well connected with access to imported continental music and to music and manuscripts associated with the royal court and the privy chamber, albeit indirectly. Yet the liturgical and devotional repertory preserved here is modest, offering little opportunity for choice and variation. Far from the vibrancy that Jonathan Willis interpreted in the extensive records of pricksong he identified in first decades of Elizabeth reign, these partbooks present a picture of a more modest and conservative culture of liturgical music-making.Footnote73 Copying is taking place, but the music is retrospective, with late-Henrician and Edwardian pieces still serving as staple repertory.

The priority was music for the canticles of Morning and Evening Prayer. Communion music – although found in the Edwardian Wanley partbooks – was not a concern for this early Elizabethan institution. Nor was the provision of anthems an immediate priority as it was not until the latter stages that a specific group of anthems appears to have been collected. Music of a more general moral and devotional nature had been compiled earlier, presumably for the edification the choirboys who also used the collection of textless music to gain experience of a wide range of genres and styles and music of greater complexity. These boys were also permitted to contribute to the copying to various degrees depending on their competency.

By the 1580s the books had fallen out of use and had been transferred to a domestic context (as shall be argued later in this article). If by the 1580s the church or chapel could no longer afford to maintain its choirboys, then obsolete music books may well have passed into new, private ownership. Such a narrative would fit with the pattern of decline that Willis saw in parochial records of pricksong by the 1580s.Footnote74 Nevertheless it cannot be ruled out that the partbooks were simply replaced because they had become worn, or had limited space left, or because a more modern repertory was desired. Willis saw no evidence of a parallel decline in institutions such as cathedrals,Footnote75 and the nature of the institution in which 30480-4 were used is difficult to ascertain. The context is unlikely to have been a grammar school as provision was made for services to be sung without the boys, while the large number of collaborating hands – particularly the large number of novice hands copying Causton’s service – would seem to indicate a larger ensemble than one might expect in a private chapel. The choir school of a cathedral, collegiate chapel, or large parish church would seem the most likely context.

Some clues as to the geographical location of this unknown institution capable of supporting choirboys can be gleaned from the composers represented in the collection. Hofman argued for a London provenance pointing to concordances with the Wanley manuscripts (which Le Huray had suggested were copied for a private chapel or London parish churchFootnote76), as well as the inclusion of secular playsongs and repertory by London-based composers such as William Whitbroke (St Paul’s), and Chapel Royal composers such as John Sheppard, Thomas Causton and (erroneously) Robert Adams.Footnote77 To these John Milsom added John Francklynge, a conduct at St Michael’s Crooked Lane, London in 1547.Footnote78 One might also add the courtly connections of Philip van Wilder, William More, Thomas Tallis and even Christopher Tye.

Other composers, however, suggest an alternative East Anglian origin. Osbert Parsley was a singer at Norwich cathedral, while both Christopher Tye and Robert White had connections to Ely and Cambridge. Moreover, Roger Bowers has recently made a specific case for King’s College, Cambridge as the originating institution. His argument is based on the identification of Robert Adams with the King’s College Fellow Richard Adams and the presence of several Thomas Hamonds among the Chapel staff: one a choirboy in 1560–62 and another the Master of the Choristers in 1587–92 and from 1598 to his death in 1605. The latter had a nephew called Robert Hamond, while a George Hamond was a lay clerk in the choir in 1613–15. Both of these are names that appear on the flyleaves of 30480-4.Footnote79 Tye’s time as a lay clerk at the college in 1537 might also explain the presence of a significant proportion of his sacred music, several pieces being uniquely preserved in these manuscripts.

The King’s College thesis would fit with many of the features of the early layer of the manuscript. Boy choristers were trained at the college, while the college’s lean towards a more radical Protestantism in the 1570s under the new Provost Roger Goad discouraged elaborate musical provision and might explain the modest repertory (in terms of number of liturgical items, size of ensemble required and polyphonic style) found in 30480-3. Although the acquisition and copying of music continued, the organ had been removed and there were increasing numbers of ‘dry choristers’ who maintained their exhibitions long after their voices had broken. Moreover, from 1578 the post of Master of the Choristers was no longer filled by a professional musician, which would provide a cause for the partbooks’ transmission to a new context in the 1580s (as shall be described in the following sections).Footnote80

Nevertheless, the dates of the King’s College Hamonds do not fit well with the manuscript dates I am proposing. In 1560–2 the manuscripts would not yet have been begun, but by 1587 the books had already left their original liturgical and educational context. This means that there is no clear candidate at King’s College for the Thomas Hamond who wrote his name at the end of Thomas Causton’s Benedictus in the bassus book (30483, fol. 39v) during the 1570s. Nor can the later connections with Robert and George Hamond have a significant bearing on the manuscripts’ origins. Moreover both ‘Hamond’ and ‘Adams’ are very common names; Suffolk Manorial Families alone includes six extended family trees for the name ‘Hamond’, while at least five Thomas Ham[m]onds were students or fellows at Cambridge between 1555 and 1587.Footnote81 As shall be seen later, the dates of the King’s College Thomas Hamonds do not easily accord with those of the Hawkedon. They would have to be assumed to be relatives, but not particularly close ones, as there are no plausible candidates on the established family tree.Footnote82

The King’s College theory is therefore attractive, but not conclusive. Ultimately the origins of these partbooks are only likely to be proven through identifying the place of employment of one or more of the lesser-known composers in the collection. The key figure would be Partyne whose Evening Service opens the collection. At present almost nothing is known about this composer except that a five-part Fancy by a composer of the same name appears in the orphan partbook US-Ws: V.a.408.Footnote83 Unfortunately the origins of this manuscript are no clearer than for the 30480-4 partbooks. V.a.408 was owned by Thomas Inons who inscribed his ownership inside the cover, but his identity and geographical origins are as yet unknown.Footnote84 The miscellaneous contents of these books are not unlike those of the 30480-4, with separate sections of textless music (motets, madrigals, chansons and In nomines) and English anthems. The English composers represented are mostly minor figures, but the areas in which they are known to have worked are geographically disparate. The less common figures are Matthew Jeffries who worked at Wells Cathedral from 1579–c.1613, Edward Blanckes who worked as a London wait from 1582 and Mallorie who was associated with the Peterborough area until his death in 1572.Footnote85 The latter two are closest to the geographical connections of 30480-4, and Christopher Tye is also well represented in both collections. Other little-known composers that might help place 30480-4 are Feryng – whose surname may relate to the Essex village of Feering – and Baruch Bulman, who might be the same Mr Bulman that also composed a Pavan for lute found in GB-Gu: MS Euing 25 (but again his location of employment is unknown).

In the meantime, it seems safest to conclude that the partbooks originated c.1570 from an institution that supported and trained a group of choirboys who sang within its services, somewhere within the region spanning London and East Anglia.

Connections with the Hamond family

Having established that 30480-4 originated as a liturgical and educational collection in the 1570s, the next question is how these manuscripts came to be in the possession of Thomas Hamond of Hawkedon in Suffolk, who claimed ownership in 1615.

The Hamond family emerge as crucial to the later history of these books. The end of the original layer saw the first traces of a young ‘Thomas Hamond’ who substituted his name at the end of Thomas Causton’s Benedictus (see ‘Phase IV’; 30483, fol. 39v). Further signatures follow at the end of the 1580s infill (Phase V), while the copying of the 1590s–1600s (Phase VI) can be directly associated with members of the Hamond family through comparison with other partbooks owned by the Thomas Hamond of 1615. Indeed Thomas Hamond’s inscription of ownership was one of the last elements to be added, save the annotations of eighteenth-century antiquarians. Understanding the Hamond family tree and its various Thomases is therefore an essential starting point.

The musical interests of the 1615 owner, Thomas Hamond (d.1662), are well documented. He was a copyist, collector and even a composer. Between c.1630 and 1661 he copied six extant sets of vocal music (GB-Ob: MSS Mus. f. 1-6, 7-10, 11-15, 16-19, 20-24 and 25-8) and a note in Mus. f. 7 (fol. 2) also refers to a now-lost ‘viol book’.Footnote86 Craig Monson has also suggested that Hamond copied GB-Lcm: MS 684 as a gift for a fellow Cambridge man, William Firmage, at some point before 1621.Footnote87 Hamond showed an interest in older music, acquiring copies of the Recueil du Mellange d’Orlande de Lassus (1570) in 1635 and William Byrd and Thomas Tallis’s Cantiones sacrae (1575) in 1652.Footnote88 Finally his own song Mine Eye Why Didst thou Light appears at the beginning of Mus. f. 7-10, while he claims to have composed the two inner parts for Sweet was the Song the Virgin Sang at the end of the same set.Footnote89 He may also be the ‘T.H.’ who wrote a commendatory Latin poem for Thomas Ravenscroft’s A Brief Discourse (1614).Footnote90