ABSTRACT

Community-based ecotourism is considered a sustainable and holistic approach to local development which brings together environmental sustainability and socio-cultural benefits to local people. As an ecotourism activity, homestays contribute to the local community economically, ecologically, culturally, and socially. These benefits have instigated the proliferation of the homestay model in developing countries. However, the success of homestay operations depends on their sustained ability to attract guests, which are impacted by the social networks of the homestay operator. Accordingly, this study examines the role social networks play in homestay operations, through a qualitative approach, drawing on 46 interviews. Specifically, focusing on Bhutan, this study identifies actors that play a role in attracting guests. The findings suggest that actors can have a direct or indirect impact on the ability to attract guests. Those exerting a direct impact are usually in a position to influence the guest’s decision, while actors who have an indirect impact contribute to the experience guests have and, therefore, their satisfaction. These actors also have influence over capacity-building activities and policy which in turn influences homestay operations and, ultimately the sustainability of the ecotourism enterprise.

1. Introduction

Homestays, as a community-based ecotourism activity, represent the commercialisation of private accommodation where visitors stay as guests in the homes of residents within a host community (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., Citation2015). This enabls visitors to interact with the host family and gain an immersive experience of the local culture and community (Zhao et al., Citation2020). The economic, ecological, cultural, and social benefits associated with homestays have contributed to their proliferation as a business model within developing countries (Shukor et al., Citation2014; Tavakoli et al., Citation2017). Economically, homestays contribute to the local economy directly by generating income for the host family and indirectly by enhancing the living conditions within rural communities (Janjua et al., Citation2021; Ly et al., Citation2021). By generating employment, homestays can reduce outward migration, helping retain local talent and skills (Agarwal & Mehra, Citation2019). Ecologically, homestay programmes can motivate local communities to appreciate the value of their natural environment in attracting guests and enact efforts to conserve it (Arevin et al., Citation2014; Razzaq et al., Citation2011). Given the role of local culture in attracting visitors, homestay programmes can also contribute to preserving traditions and customs (UNWTO, Citation2016). Finally, homestay programmes can influence the social environment by increasing community pride and encouraging residents to work together to provide a tourism experience (Marques & Gondim Matos, Citation2020).

As a small business, homestay operations in developing countries face numerous challenges. This includes limited access to specialised entrepreneurial skills and language abilities which can impede their access to visitors and their ability to provide services critical to their operational sustainability (Kunjuraman & Hussin, Citation2017; Pusiran & Xiao, Citation2013). It is here social networks can play a role by enabling operators to access opportunities beyond their immediate capabilities (Jones, Citation2005). The literature, for instance, notes that social networks with local tourism entities is a critical success factor in attracting guests to homestay operations (Dawayana et al., Citation2021; Tavakoli et al., Citation2017). Arguably, social networks (both formal and informal) can help entrepreneurs access staff, resources, and customers required to support their operations (Çakmak et al., Citation2018); however, limited research has explored such strategic aspects of homestay operations (Janjua et al., Citation2021).

The aim of this study is to examine the role of social networks in homestay operations. Specifically, this study explores intermediaries and the roles they play in facilitating access to guests. By understanding social network dynamics, homestay operators can manage how they interact with actors that control information and resources crucial to their success (Prell et al., Citation2010) – in this case, guests.

2. Guiding framework

Social networks refer to the set of connections and interactions intermediaries have within a system (Tabassum et al., Citation2018). Social Network Theory (SNT) relatedly examines the relationships among intermediaries within a system (actors) and their relational position in the distribution of resources within that system (Marques & Gondim Matos, Citation2020). Eisenberg and Houser (Citation2007), explain SNT denotes how actors are connected (relationships) to each other and how these connections produce and define human society. Such networks can comprise formal ties that are organised intentionally around a common purpose where intermediaries play designated roles (Prell et al., Citation2010); and informal ties that evolve organically through personal relationships (Klitsounova, Citation2020).

Within a business context, three types of social network actors can have an influence on the flow of information and resources: gatekeepers, pulse takers, and hubs (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018; Waldstrøm, Citation2001). Gatekeepers act as the bridge for the flow of information and resources. Consequently, they can function as brokers that enable the exchange of information and resources or create bottlenecks barring the flow of information and resources (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018). As such, gatekeepers can influence membership within the network based on their ability to control the distribution of information and resources. Pulse takers tend to have a high level of interaction with intermediaries within a network by being connected to different parts of the network (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018). Accordingly, they tend to develop tacit knowledge about trends and changes within a network and can act as information filters by deciding what is shared with others (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018). Finally, hubs refer to actors centrally connected to the maximum number of diverse groups and people in the network (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018) and can facilitate the distribution of information and resources to different parts of the network.

The networks homestay operators maintain, particularly with those outside their local community, can influence their ability to attract guests and generate revenue (Lynch, Citation2000; Park et al., Citation2018). Interactions with other parts of the network, such as local tour operators or experience providers, can also inform the overall experience guests are offered (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., Citation2015; Tavakoli et al., Citation2017). Such networks can influence homestay operators by enabling or restricting access to guests and the type of experiences homestay operators can provide (Kontogeorgopoulos et al., Citation2015). Given the role of networks in influencing the success of homestay operations, SNT offers an effective framework to explicate the interaction among diverse intermediaries (Erikson, Citation2021).

3. Methods

This study aimed to explore the intermediaries within the social network of homestay operators and the roles they played in enabling access to guests, using Bhutan’s Phobjikha Valley as a case study area.

3.1. Case study area

This study focuses on Bhutan, a country with 158 homestays currently in operation (as of June 2021, TCB, Citation2021) and where homestays are recognised as a means of economic development, generally run by local residents in rural areas, certified by the Tourism Council of Bhutan (TCB) after verification of basic facilities (i.e. western toilets, adequate sleeping spaces). The TCB oversees tourism development, regulation and certification within Bhutan as well as promotion and branding. Tour operators are private enterprises that identify homestays and make reservations on behalf of guests, while national tour guides are trained and certified by the TCB and accompany guests throughout their stay in Bhutan.

This research studied the Phobjikha Valley in Bhutan, helping to ensure homestay operators were relatively homogenous regarding the experience they could provide. Homestays have been in operation within this region for longer than any other part of Bhutan – enabling this study to benefit from the experiences of participants who have operated as homestays over time. The Phobjikha Valley, part of the Wangduephodrang Dzongkhag, is the winter roosting habitat for Black-necked cranes. The valley has a population of 5,387 (DAW, Citation2021), with the main occupation being farming. The Royal Society for the Protection of Nature introduced homestays into the Phobjikha Valley to motivate residents to support ecological conservation by giving them an economic reason to do so. At the time of the study, there were 30 certified homestays in the valley.

3.2. Research approach

Given the need to understand the unique experiences of homestay operators, an interpretivist qualitative approach was adopted. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with participants to enable the discussion to be tailored to their context (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019). Three main groups of potential participants were identified: key informants, certified homestay households, and non-homestay households. During the fieldwork, it became apparent that some households operated homestays but were not officially certified. Accordingly, a sample of these households were included. explains the sample composition.

Table 1. Sample compositions.

Interviews were conducted remotely (between January and April 2021) through Zoom or WhatsApp – to accommodate for participants’ varying needs and technological proficiency.

It is likely that participation may have been limited to those with access to technology, however based on the lead author’s experience (who is Bhutanese and has worked in Bhutanese tourism industries), it is common to use WhatsApp for personal and business communication supporting its use in this study. After the interview, transcripts were compiled and analysed using Nvivo12. Transcripts were coded using a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), and analysis was conducted by the lead author with the findings presented and discussed with the research team to build trustworthiness (see also Gyamtsho et al., Citation2022). Three experts external to the research also reviewed the findings helping to nuance the conceptualisations developed. The research was approved by the Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol: H19358).

4. Findings

Overall, participants acknowledged social networks played a significant role in accessing guests. One participant summarised this noting:

Regarding the access of guests, it is entirely dependent on the relationship you maintain with as many relevant people as possible. (HH01).

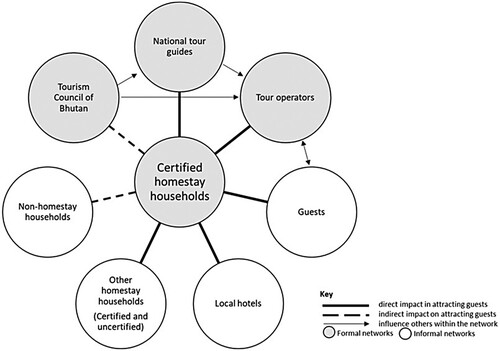

Figure 1. Intermediaries within the homestay social network.

Homestay operators believed building relationships with other intermediaries within the network was important. Accordingly, they often provided free accommodation and meals for tour guides to attract guests in the future:

We do provide free accommodation and food to guides and drivers. This is a kind of business strategy as they are the people who deal with guests. If they are satisfied and happy, it is more likely we get guests in the future (HH09).

4.1. Direct impact on attracting guests

4.1.1. National tour guides

National tour guides are professionally trained and certified by the TCB and accompany guests within the country. They play a crucial role as an interlocutor between guests and local operators considering local operators often do not speak English. Typically, national tour guides spend the most time with visitors in Bhutan and, therefore, can recommend suitable homestay accommodation. Because of their strong ties with guests, guides were perceived as a credible source of information by tour operators and could influence other guides about suitable homestay accommodation providers:

… having good links with guides can help to get guests. Guides tell their friends and other people they know … they can also talk to the tour operator to book [homestays] they already know. Guests also listen to guides as they don’t know about the places and [homestay]. (HH11).

4.1.2. Tour operators

Tour operators include private businesses that organise local experiences for visitors. They are often responsible for booking homestays for guests, and therefore homestay operators need to remain top-of-mind with them. Tour operators select homestays based on the quality of services and experiences they can provide guests.

The policy of our company is we need to ensure there is a proper toilet with modern facilities and the toilet has to be in [a good] condition even if they don’t have modern facilities. Secondly, there has to be inner settings as per the tradition like the Altar room. Another thing that we look into is a traditional hot stone bath. If all these things are present, then we consider the homestay. (KI05),

4.1.3. Guests

While guests function as a resource within the network, they also influence other guests. Key informants and homestay operators believed providing high-quality service would help homestays attract future guests through repeat visitation or word-of-mouth. Guests can also influence tour guides by indicating a preference for homestay accommodation providers:

Tourists who visit from outside, expatriates or foreigners tend to go to the house which is well-recommended by those who have a good experience earlier. (KI04)

4.1.4. Local hotels

Local hotels were seen to play an informal role within the network because they provided visitors with recommendations of homestays they could consider – particularly when they do not have enough rooms available themselves. Informal networks influenced which homestays were recommended.

It is also helpful to keep good links with local hotels as they send guests to their relatives operating homestays, and to those they have good relationships as well. (HH07).

4.1.5. Other homestays

Participants explained that through strong informal ties, guests were shared between homestays when they could not accommodate them. This was typically the case between certified and uncertified homestays – wherein certified households passed guests to uncertified operators.

We help each other when we have more guests. I have a sister who also operates a homestay. I share the guests with her when I have more guests. I also get guests from her when she has many. (HH03).

4.2. Indirect impact on attracting guests

4.2.1. Non-homestay households

Non-homestay households provide experiences visitors can participate in while staying at a homestay and consequently can influence guest satisfaction. In addition, they support homestay operators with other operational tasks they might be unable to perform:

We help the homestay operators when they have guests. We help them in a number of household activities such as tidying rooms, cattle herding, and preparing the hot stone bath [for guests to use]. We also sing our traditional songs depending on the guests’ interests. (NHH15).

4.2.2. The Tourism Council of Bhutan

While it was accepted that the TCB had no influence on accessing guests, participants believed they played a role because of their ability to certify homestays and provide access to training. The TCB also had an influence on tour operators and guides by developing tourism strategies and policies. A key informant from the TCB noted:

We have an annual budget for human resource capacity building. So, every year, we look at the homestays in the country. If some homestays have already attended training we prioritise and give training to new homestays in specific locations.(KI03).

5. Discussion, implications, and limitations

This study explored the intermediaries within the social network of Bhutanese homestay operators that played a role in accessing guests. The findings suggest intermediaries played distinct roles based on the nature of their relationship – formal vs informal, and in the access they provided to guests – direct versus indirect. Consistent with the literature, homestay operators believed social networks (formal and informal networks) influenced the success of their business by enabling or hindering access to guests (Yang & Horak, Citation2019). In this context, certified homestays emerged as a hub (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018) between the various intermediaries within the two networks.

The formal network included intermediaries like national guides, tour operators, and the TCB. Tour operators and national guides were considered important intermediaries in providing direct access to guests. The TCB (Citation2020) requires that tour guides should accompany all guests while in the country. Given the strong ties guides had with guests because of their interaction and influence, they functioned akin to gatekeepers. Doing so, they influenced which homestay operators participated in the network (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018). On the other hand, because of the influence of tour operators on bookings and their role as an intermediary between national tour guides and guests, and homestay operators, they played a role as pulse-takers.

Interestingly while the TCB could function as a gatekeeper due to their ability to certify homestays, this role appeared to be eroded. TCB (Citation2021) as an apex tourism entity is responsible for the overall tourism development and regulation in Bhutan and is required to monitor and assess tourism operators to ensure alignment with designated standards of practice. However, an inability to effectively monitor ongoing homestay operations because of limited human resources, combined with informal networks that distributed guests based on social relationships, appears to have facilitated the organisation of uncertified homestays. This aligns with Prell et al. (Citation2010), who argue that informal networks tend to fill weaknesses within formal structures. Nonetheless, based on their influence on developing tourism strategies, policies, and training programmes, the TCB appeared to function like a hub, sharing information with different elements of the formal network and playing an indirect role in building capacities and systems to access guests.

Informal relationships with local hotels and other homestays appeared to play a role in attracting guests when those intermediaries could not accommodate additional guests. This builds on the literature (Prell et al., Citation2010; Tavakoli et al., Citation2017) by demonstrating how informal networks can facilitate a reciprocal relationship between competitors within the same system. Similarly, others within the local community who did not provide homestay services (non-homestay households) could also benefit economically while contributing to guests’ experience having an indirect effect on attracting future guests. The strong ties facilitated by these informal networks contributed to network cohesion enabling intermediaries within a community to aspire to a common purpose (Tortoriello et al., Citation2012). The findings indicate an intermediary may play distinct roles depending on the focus of the social network (Muñiz & Cuervo, Citation2018). Accordingly, while certified homestays may operate as a hub between the various intermediaries, they may also function as gatekeepers from the perspective of non-homestay households by influencing their participation in the network. This highlights the unequal power relations between stakeholders in the tourism sector and the role of informal entrepreneurs who may remain hidden from formal governance structures or policy processes (Çakmak et al., Citation2018).

On a practical level, the findings highlight the need for governmental bodies responsible for tourism to facilitate the creation of formal social networks and develop systems that support them. Industry networking events can play a role by bringing together different intermediaries within the social network to share information and create a common sense of purpose. There is also potential to acknowledge and support informal networks, given their influence on the visitor’s overall experience at the destination. Formalising such networks could help further build capacity to attract and satisfy guests. This may require implementing processes to ensure homestay operations and experiences can be effectively monitored by intermediaries like the TCB, while not hindering the entrepreneurial nature of communities and the private sector.

The limitations of the study are acknowledged. First, the study was conducted in Bhutan – a developing country with a collectivistic culture which may explain the flourishing of informal social networks. While the context is a strength of this work, the findings may however be relevant to other countries that share a similar culture, and future research may consider exploring how social networks influence similar businesses within different contexts. Second, due to travel restrictions imposed by COVID-19 during the fieldwork period, this study was conducted online with participants who self-volunteered. Augmenting the interview approach with on-the-ground observations would have provided a more nuanced understanding of the local environment and the dynamics at play. Finally, as an exploratory study, this research took an overall view of the intermediaries within the network and did not focus on individual operators. Future work may apply social network analysis to map out the relationships between individual operators to gain a deeper understanding of the relationships and behaviours within the network.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the respondents for generously participating in this research. We also thank the three examiners of the thesis that this article stems from.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agarwal, S., & Mehra, S. (2019). Socio-economic contributions of homestays: A case of Tirthan valley in Himachal Pradesh (India). Tourism International Scientific Conference Vrnjacka Banja, 4, 183–201.

- Arevin, A. T., Sarma, M. M., Asngari, O. S., & Mulyono, P. (2014). The empowerment model of coastal homestay business owners in five strategic areas of national tourism. International Journal of Administrative Science & Organization, 21, 9–17.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Çakmak, E., Lie, R., & McCabe, S. (2018). Reframing informal tourism entrepreneurial practices: Capital and field relations structuring the informal tourism economy of Chiang Mai. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.06.003

- DAW. (2021). Dzongkhag Administration, Wangdue Phodrang. Dzongkhag Administration, Wangdue Phodrang. http://www.wangduephodrang.gov.bt/

- Dawayana, C. R., Jrb, S. L. S., Tanakinjalc, G. H., Bonifaced, B., & Nasipe, S. (2021). The effects of homestay capabilities on homestay performance in Sabah. Journal of Responsible Tourism Management, 2, 72–92.

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000057. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Eisenberg, A. F., & Houser, J. (2007). Social network theory. The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.10029781405165518.wbeoss171

- Erikson, E. (2021). 10 networks and network theory: Possible directions for unification. In Social theory now (pp. 278–304). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226475318-011

- Gyamtsho. P. (2022). An exploration of social networks in homestays: A case study of Bhutan. MPhil thesis, Charles Sturt University. 137 pages

- Janjua, Z. u. A., Krishnapillai, G., & Rahman, M. (2021). A systematic literature review of rural homestays and sustainability in tourism. SAGE Open, 11, 21582440211007117.

- Jones, S. (2005). Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.06.007

- Klitsounova, V. (2020). Networking, clustering, and creativity as a tool for tourism development in Rural Areas of Belarus. In Susan L Slocum & Valeria Klitsounova (Eds.), Tourism Development in Post-Soviet Nations: From Communism to Capitalism (pp. 155–173). Springer Link.

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N., Churyen, A., & Duangsaeng, V. (2015). Homestay tourism and the commercialization of the rural home in Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2013.852119

- Kunjuraman, V., & Hussin, R. (2017). Challenges of community-based homestay programme in Sabah, Malaysia: Hopeful or hopeless? Tourism Management Perspectives, 21, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.10.007

- Ly, T. P., Leung, D., & Fong, L. H. N. (2021). Repeated stay in homestay accommodation: An implicit self-theory perspective. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–14.

- Lynch, P. A. (2000). Networking in the homestay sector. Service Industries Journal, 20(3), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060000000034

- Marques, L., & Gondim Matos, B. (2020). Network relationality in the tourism experience: Staging sociality in homestays. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(9), 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1594722

- Muñiz, A. S. G., & Cuervo, M. R. V. (2018). Exploring research networks in information and communication technologies for energy efficiency: An empirical analysis of the 7th framework programme. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.049

- Park, E., Phandanouvong, T., & Kim, S. (2018). Evaluating participation in community-based tourism: A local perspective in Laos. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1323851

- Prell, C., Reed, M., Racin, L., & Hubacek, K. (2010). Competing structure, competing views: The role of formal and informal social structures in shaping stakeholder perceptions. Ecology and Society, 15(4), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03652-150434

- Pusiran, A. K., & Xiao, H. (2013). Challenges and community development: A case study of homestay in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 9(5), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n5p1

- Razzaq, A. R. A., Hadi, M. Y., Mustafa, M. Z., Hamzah, A., Khalifah, Z., & Mohamad, N. H. (2011). Local community participation in Homestay Program Development in Malaysia. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 7, 1418–1429.

- Shukor, S., Salleh, N. H. M., Othman, R., & Idris, S. H. M. (2014). Perception of homestay operators towards homestay development in Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan, 42, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.17576/pengurusan-2014-42-01

- Tabassum, S., Pereira, F. S., Fernandes, S., & Gama, J. (2018). Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek: Revised and expanded edition for updated software. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 8, 1–21.

- Tavakoli, R., Mura, P., & Rajaratnam, S. D. (2017). Social capital in Malaysian homestays: Exploring hosts’ social relations. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(10), 1028–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1310189

- TCB. (2020). Guidelines for the management of regional tourists. Tourism Council of Bhutan. https://www.tourism.gov.bt/uploads/attachment_files/tcb_PJ0ApDSJ_tcb_jaX01JRo_External%20version%2015%20guideline%20Management%20Of%20Regional%20Tourism%20as%20of%2021.07.2020%20%20(approved%20by%20the%20Cabinet).pdf

- TCB. (2021). Registered Village Home Stays. Tourism Council of Bhutan. https://www.tourism.gov.bt/home-stays

- Tortoriello, M., Reagans, R., & McEvily, B. (2012). Bridging the knowledge gap: The influence of strong ties, network cohesion, and network range on the transfer of knowledge between organizational units. Organization Science (Providence, R.I.), 23(4), 1024–1039.

- UNWTO. (2016). Tourism and culture partnership in Peru – Models for collaboration between tourism, culture and community. W. T. Organization. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.181119789284417599

- Waldstrøm, C. (2001). Informal networks in organizations-A literature review. University of Aarhus, Aarhus School of Business, Department of Management Working Papers. 2001-2.

- Yang, I., & Horak, S. (2019). Emotions, indigenous affective ties, and social network theory—The case of South Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(2), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9555-7

- Zhao, Y., Chau, K. Y., Shen, H., Duan, X., & Huang, S. (2020). The influence of tourists’ perceived value and demographic characteristics on the homestay industry: A study based on social stratification theory. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.10.012