Abstract

In this visual essay, personal growth, experienced by the authors, is explored and communicated through combined images and words. A theoretical framework – that of Mezirow’s (1994. “Understanding transformation theory.” Adult Education Quarterly 44 (4): 222–232) transformative learning – is adapted to structure the essay, and images communicate the transformative growth experienced by the four authors through involvement in a transnational education project. Images were all taken in Bruges, a significant place for all the authors in respect to interconnectedness and growth. Bruges was the location for the culmination of the transnational project, and was a new place to all authors before their involvement in the project. Images are accompanied by captions to add a layer of meaning, but neither image nor caption is truly narrative and represents the growth experienced, rather than illustrating the activities of the project. A reflective conversation, held in Bruges, provided the captions. The visual essay provides a reflection of the interconnectedness between place, experience, growth, words and image.

INTRODUCTION AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This visual essay uses images to represent interconnectedness, place, and growth through experiences within a transnational educational research project. The transnational project ran for six consecutive years, and involved five European countries: Belgium, Denmark, England, Norway and Spain. Called ‘Digital Learning Across Boundaries’ (DLAB), the project sought to explore digital learning through co-creation, and to cross geographical, personal, emotional and environmental boundaries. Members of the project team, which included school staff, university students and university staff, in a flat hierarchy, communicated and co-created via digital and physical spaces. The images in this essay were photographed at the end of the project by four members of the team, whilst in Bruges – a significant place for the project and its participants. Bruges's significance lies within these key ideas of interconnectedness and personal growth: the city was the location for transnational meetings, and the culmination of the final year of the project at a multiplier event created by members of the team from all five countries. As the project involved working in parallel in home countries, the meeting in Bruges was an opportunity for in-person collaboration, connection and creation. Relationships forged virtually developed in person in this place. The four authors revisited Bruges for post-project activity, and captured this reflection on how the project had facilitated their own personal growth.

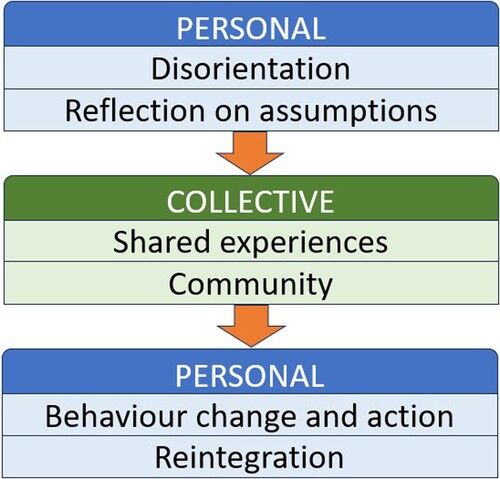

The images are curated around a framework inspired by Mezirow's transformative learning model (Mezirow Citation1994). Mezirow's work centres around the way that learning can transform ‘problematic frames of reference’ (Mezirow Citation2003, 58). His model identifies 11 stages of this transformative process (Mezirow Citation1994), during which initial discomfort and disorientation give way to assimilation of new actions and behaviours into the learner's life. An adapted framework (), devised by the authors as we reflected, collates the elements of the model into six stages, focusing on how the learner experiences each of these. It groups Mezirow's stages into three distinct phases which form the transformative journey: an initial personal phase, where there is disorientation and reflection, then a collective phase, where the personal growth continues through shared experience and community engagement. This is bookended by another personal phase, where the learning manifests into real change within personal behaviours, and integration into the new ways of being for that individual. This process is felt to reflect the experiences of the four authors’ involvement in DLAB, where individual starting points gave rise to individual, but connected, journeys of change. The project was innovative, creative and multi-faceted, and it is this depth and nuance which the authors feel was the catalyst for transformative learning experiences. It was therefore decided, that in order to communicate this growth, images would be curated around this framework.

FIGURE 1. Framework adapted from Mezirow (Citation1994).

Morgan (Citation2010, 249) suggests that travel to new places can provide opportunity for a ‘disorientating dilemma’, which marks the beginning of the transformative learning process. The gap between the usual and the new place can provide ‘“distance” … in an experiential or existential sense as well as … geographical’ (Morgan Citation2010, 249). Bruges was new to all authors before their involvement in the project, and differs from our home locations in terms of language, architecture, tourism and culture, thus presenting experience of this gap. The journey itself provided time and space for reflection on experiences, as well as serving as a physical indicator of the ‘otherness’ (Morgan Citation2010, 249) of the experience. Leijon et al. (Citation2022, 15) suggest there is a ‘movement towards an understanding of space as being produced in an entanglement of people, social and material resources’, which reflects the complexity of aspects affecting space; this was certainly true within DLAB which occupied and created learning spaces which were both physical and digital. Physical spaces, and their shaping by the people, resources and characteristics of the existing space, impacted upon the members of the project team and their learning. Bruges, as a significant place, offered this complexity and was therefore a rich space for both the initial experiences, and subsequent reflection.

IMAGE: PLACE, SPACE AND GROWTH

In this visual essay, text is added to enhance meaning – to ‘illustrate’ the photographs (Heng Citation2020, 625). Pauwels (Citation2015) suggests that words and images can work together in varying degrees of connection for differing purposes. Our captions do not provide full context for the image, rather they augment it with additional meaning for multi-aspect communication: the text and image ‘contribut[ing] their own part to the overall message’ (Pauwels Citation2015, 141). The text extracts are taken from a reflective conversation held in Bruges between the authors, where discussion focused on the learning experiences and their connection with Bruges as a significant place within this transformative process. Heng (Citation2020, 625) explains that captions can ‘situate’ the image in context; rather than providing full explanation, our words aim to add a layer of meaning.

Some of the images lean away from being overtly narratively framed, towards a more abstract reflection of place, and representation of growth. They do not include the people involved in the DLAB project, or images of the project's activities. Mena-de Torres and Roldán (Citation2017, 250), also exploring educational spaces, explain this ‘provides us with a novel way to evaluate, criticize and understand education’. In an approach which has some similarities to Chong’s (Citation2024), our images are not intended to represent truthful reflections of place as it exists, but to capture moments exploring the reflexive response to place, space, and in our case, growth. The image holds its own ‘agency’ (Rose Citation2023, 42) and in this essay, the use of non-narrative photographs enables the reader to bring their own experience to the image. This is suggested by Heng (Citation2020, 626); it enables nuanced communication, where the reader interprets the images in line with their own experience, combined with the additional frame provided by the caption and structure of the essay. The combination of theoretical framework, image and caption hopes to communicate the authors’ experience of transformative learning, utilising visual studies’ offer for boundary exploration (Pauwels Citation2021).

Personal: Disorientation

Personal: Reflecting on Assumptions

FIGURE 3. There's so much information, and you have to ‘undo it’ – you have to decode it. I felt … embarrassed that people from the other countries could speak, you know, three or four languages. And I know the project language was English so that's fine, but it did really matter. That's one of the reasons I’ve started to learn a language.

Collective: Shared Experiences (1)

FIGURE 4. We went on the boat as we were learning about the history of Bruges … there was wonderment and I think they realised actually how special it was, that it wasn't just that they were abroad, or in Bruges, they realised the history … it needed something external I think to the project maybe just to shift it and say we’ve got the shared experience now and let's have a go …

and it was new for all of you

we experienced it together

you were all in a new place – a novel place.

Collective: Shared Experiences (2)

Collective: Community (1)

Collective: Community (2)

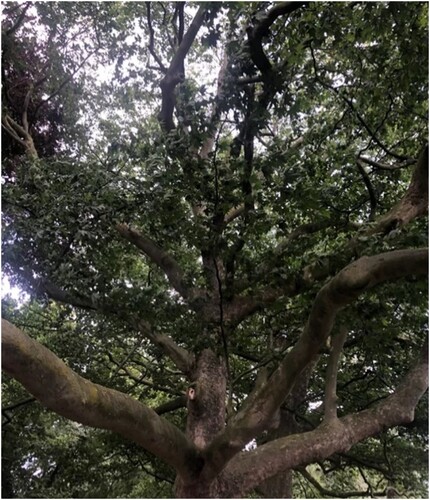

FIGURE 7. I’m thinking about how knowledge evolves. I want to use the term rhizomatic learning which basically describes learning that takes place through a kind of root system or a network or an evolving system, so doesn't go one direction, it evolves in lots of directions and it's led by the people who are involved with it. And it's unpredictable; it's not preconceived …

it's intuitive

it’s based on the connections and the intuitions

the needs of the group

insights that people make together, when they engage together. And that describes how learning went into DLAB.

Personal: Behaviour Change and Action

FIGURE 8. … makes me think how we use contemporary technologies in the project, and how we were trying to solve problems in the way that those people, the people engineering those things were solving problems, and how they were trying to draw on new strategies and new technologies.

We used a lot of design thinking, so that divergent thinking, open the lock gate, let everybody speak, bring your ideas, and then we close it again, let's bring it back in, and let's concentrate on what we want to do. It's a great way to solve problems.

We used technology – making our own, being creative with virtual reality. People were making – they were using virtual reality to create … to share each other's worlds.

CONCLUSION

Capturing through image, and the resultant conversation shared between the authors whilst in Bruges, gave space for reflection and sense-making. The framework, adapted from Mezirow's stages of transformation, gave structure for exploring the growth the authors had experienced. Bruges, as a significant place for the authors, provided a meaningful context for this reflection, and for visually capturing the significance of place. Communicating this through image and text combined has enabled expression of the growth from personal perspectives.

DATA ACCESS STATEMENT

All data underpinning this publication are openly available from the University of Northampton Research Explorer at https://doi.org/10.24339/d164dbe0-772b-4628-9c34-aa0156c43805

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amy West

Amy West is a Learning Development Tutor at the University of Northampton. Amy's research interests include the use of metaphor as a pedagogical tool, particularly within the learning and teaching of academic skills and literacies. Her background is in the arts, and primary education.

Helen Caldwell

Helen Caldwell is an Associate Professor in Education. Helen's research interests include technology-enabled social online learning in teacher education, developing changemakers and the use of immersive technologies for teaching and learning. Helen co-leads the Centre for Active Digital Education at the University of Northampton.

Helen Tiplady

Helen Tiplady is a Senior Lecturer in Education (ITT) at the University of Northampton and is currently the Curriculum Lead for science. Her research activities have included the co-creation of training videos using IRIS Connect software and researching how children use evaluation tools in wellbeing music workshops. Her background is in primary school leadership, teaching and learning.

Emma Whewell

Emma Whewell is an Associate Professor in teaching and learning at the University of Northampton. She is the Deputy Subject Leader for Sport and Exercise and the Programme Leader of the BA (Hons) Physical Education and Sport Degree. She is the Co-Lead for the Centre for Active Digital Education.

REFERENCES

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2024. “Neither Spectacular Nor Ordinary: A Visual Essay on Imaginations and Homes in Beijing from 2007 to 2019.” Visual Studies 39 (1–2): 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2023.2195841.

- Heng, Terence. 2020. “Creating Visual Essays: Narrative and Thematic Approaches.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by L. Pauwels and D. Mannay, 617–628. London, UK: SAGE.

- Leijon, Marie, Ivar Nordmo, Åse Tieva, and Rie Troelsen. 2022. “Formal Learning Spaces in Higher Education – A Systematic Review.” Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2066469.

- Mena-de Torres, Jaime, and Joaquín Roldán. 2017. “Educational Space: Photo-based Educational Research.” International Journal of Education Through Art 13 (2): 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.13.2.249_1.

- Mezirow, Jack. 1994. “Understanding Transformation Theory.” Adult Education Quarterly 44 (4): 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369404400403.

- Mezirow, Jack. 2003. “Transformative Learning as Discourse.” Journal of Transformative Education 1 (1): 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344603252172.

- Morgan, Alun D. 2010. “Journeys into Transformation: Travel to an “Other” Place as a Vehicle for Transformative Learning.” Journal of Transformative Education 8 (4): 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611421491.

- Pauwels, Luc. 2015. Reframing Visual Social Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pauwels, Luc. 2021. “Contemplating ‘Visual Studies’ as an Emerging Transdisciplinary Endeavour.” Visual Studies 36 (3): 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1970326.

- Rose, Gillian. 2023. Visual Methodologies. 5th ed. London: Sage.

![FIGURE 2. When you reflect back on the six years of DLAB, the things that drew us together were problems to solve, like floating cities, what if the sea level rose. Something in common, having something to build upon, a wicked question, or a problem – [it] draws you in, and pulls you together.](/cms/asset/2b0abff8-f6fa-4b64-b7ab-7a3aeab3b801/rvst_a_2325614_f0002_oc.jpg)

![FIGURE 5. We’ve grown for six years [in DLAB], but each year we’ve welcomed in people who offered new things.](/cms/asset/940a817f-4393-4622-8f91-5a6915eb3ec0/rvst_a_2325614_f0005_oc.jpg)