ABSTRACT

Berries hold a unique appeal, stemming from their natural aspect and the embedded cultural ecosystem services they can offer. While extensive studies have examined rural berry collectors, there is a gap of research on the engagement of urban consumers in berry-picking activities, particularly in emerging markets. This study addresses this gap by investigating the experience, consumer motivations, and other influential factors of urban consumers engaging in berry-picking activities in selected municipalities in China. Drawing on in-depth interviews with urban consumers involved in berry-picking and the thematic analysis, this research revealed three berry-picking patterns, including wild picking, pure commercial picking (U-pick), commercial picking with extra services (Pick and Plus). It identified key factors influencing urban consumer experience, namely consumer motivations, social media marketing, convenience, and service capability. It explored the challenges confronting individual berry farmers. The results highlighted the cultural and social significance of berry-picking activities, as well as the service potential of fresh berries as territorial products to bridge urban-rural divides. The research contributes up-to-date insights to the broader discourse on the cultural and provisioning ecosystem services offered by berries, shedding light on the intricate interplay among urban consumers, fresh berries, rural berry farmers and other relevant stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Berries, as a category of edible non-wood forest products (NWFPs), are also referred to as natural products (Shackleton and de Vos Citation2022). They have received much attention for their commercial value and functional benefits, such as vitamin C and antioxidants (Leßmeister et al. Citation2018). As a NWFP, berries’ subsistence uses in providing additional income to local farmers (e.g. Huber Citation2010) and their contribution to rural development have been emphasized in the literature (e.g. Huber Citation2010). It is also important to notice that their value can also be also deeply rooted in local culture. For example, the Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb et Zucc) holds significance in stories of Chinese daily life since the Han dynasty. It has been documented in numerous old poems and passed down from one generation to the next (He et al. Citation2004). Nevertheless, the growing commercial importance seems to overshadow the cultural and experiential significance of berries, diverting attention away from the embedded traditions and culture (Weiss et al. Citation2020). In addition, the growth in berry trading has caused concerns about overharvesting and ecological risks (Huber Citation2010).

A comprehensive understanding of the experience of urban consumers and of their expectations regarding berry products and services is crucial for the diverse utilization and territorial marketing strategy of berries (Rovira et al. Citation2022). However, analyses of consumer perceptions and the contextual factors influencing their participation in berry-collecting activities remain unbalanced, with a predominant focus on more developed regions, such as Switzerland (Seeland et al. Citation2007) and the Nordic countries (Amici et al. Citation2020). European and American consumers commonly perceive fresh berries they collect as natural and healthier than industrially produced alternatives (Dickson-Spillmann et al. Citation2011). Berry collectors are predominantly identified as recreational visitors (Amici et al. Citation2020; Martínez et al. Citation2021). Lifestyle and culture drive Europeans to pick wild berries, as seen in strong traditions in Finland (Kangas and Markkanen Citation2001), where two distinct groups of collectors were identified: younger families with children and older active citizens.

There is scarce literature available on urban consumers engagement in berry-picking activities in emerging countries, and the predominant focus on berries and their associated collection and consumption patterns appears to have been directed towards rural users in these countries with emphasis on livelihood and subsistence use (Shackleton and de Vos Citation2022). Meanwhile, a growing body of scholars has suggested a renewed interest in the potential of berries to boost nature-based tourism and rural development (Weiss et al. Citation2020; Rovira et al. Citation2022). In China, there also seems to be a growing trend of combining fruit-picking activities with sightseeing in rural areas, known as leisure agriculture or rural tourism (Cheng et al. Citation2020; Cui et al. Citation2021).

Despite the increasing economic importance attributed to berries, there is a noticeable gap in how urban consumers interpret and engage in berry picking. Particularly, the involvement of urban consumers in berry-picking activities remains a relatively unexplored domain in China. Therefore, this research aims to close this gap via examining experience, motivations and influencing factors of berry-picking of urban consumers. Firstly, we will examine the intricacies of their behaviour and experience during berry-picking, aiming to unveil the nuances of their participation in this activity. Subsequently, we endeavour to unravel the motivations propelling urban consumers to partake in berry-picking, and the other factors impacting their experience. By addressing these research questions, this study not only contributes to the understanding of the urban consumer perspective on berry-picking, but also sheds light on potential implications for and the marketing strategies of berries. Hence, we focus on the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1:

What kinds of behavioural patterns exist among urban consumers’ berry-picking experience?

RQ 2:

What factors drive urban consumers’ berry-picking experience?

2. Materials and methods

This study utilized thematic analysis, a qualitative method (Rovira et al. Citation2022), to explore and understand the subjective experiences and social structures of urban consumers from an interpretivist perspective (Collis and Roger Citation2014). Recognizing the complexity of consumer berry-picking activities, this approach allowed for a nuanced examination that transcended binary responses. By giving voice to the lived experiences of urban consumers, thematic analysis enabled the capture of subtle demands within the wider sociodemographic and cultural discourse. This method was particularly suited for our inductive analysis, and it has been similarly employed in many consumer studies (Collis and Roger Citation2014; Nowell et al. Citation2017). The focus was on berries (e.g. Rubus hirsutus Thunb., Vaccinium spp., Myrica rubra Sieb. & Zucc.), as a category of natural food, given their widespread consumption and relative accessibility in the study areas, aligning with our research objectives.

2.1. Context of the study

In China, the berry growth conditions vary from province to province, resulting in a diversity of berry species and berry-collecting models. Hence, berry picking in both commercially cultivated plantations and in the wild can be expected among consumers. Our focus on Zhejiang Province stemmed from an abundance of berry-picking sites, both wild and cultivated. For instance, the Chinese wild raspberry (Rubus hirsutus Thunb.), is highly consumed in Zhejiang (Wang et al. Citation2021). But the province also plays a pivotal role as a key production region for cultivated blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum), compared to northeastern Chinese provinces which stand out for their production of wild blueberries (Li et al. Citation2021). Another berry commonly grown in Zhejiang is the red bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. & Zucc.), a native subtropical fruit consumed in China for long (He et al. Citation2004). As an important component of traditional Chinese medicines, red bayberry has seen an important growth in demand, which led to increased cultivation of this tree species. Zhejiang Province, particularly Ningbo and Taizhou cities, has been a key bayberry production area since the Song Dynasty (960–1279) (He et al. Citation2004).

Furthermore, the high proportion of urban population (72% in 2020, as reported in the statistical report of the Zhejiang Provincial Government of Zhejiang Province (Citation2021) enhanced our goal to explore the topic. In addition, the selected site allowed our research team to get access to different berry farms, and to become acquainted with the local dialects and speech nuances, enriching our comprehension of the intentions expressed by the interviewees.

2.2. Data collection

The data was gathered since mid-2021 in Hangzhou and Ningbo cities, where several berry-picking hubs are located within one to two hours driving distance from city centers. The data collection spanned approximately one year, with breaks in between to allow researchers to analyze the data and to seasonally visit some picking farms to gain insights into the specific situations discussed by the interviewees. The onsite observations also provided sources for data triangulation and more comparative assessment (Collis and Roger Citation2014).

The interview guide (Appendix 1, supplementary material), was informed by literature review and our research aims to ensure that interviews were focused on key topics. The participants consisted of adult urban consumers who had been involved in berry-picking activities within the year preceding the interviews, allowing for more accurate recall of details. A total of 24 participants were involved in the study, with an average interview length of over 30 minutes (see ). Prior to the interviews, they all received an introduction outlining the purpose and main questions of the interview. These discussions were not included in the formal interview duration. The aim was to build trust between the researchers and participants (Abbe & Brandon Citation2014). During the interviews, the interviewer acted as a facilitator to further develop discussions with small follow-up questions and confirmation of the responses. At the end of each interview, participants were thanked and received stationery gifts worth US $10 to compensate them for their efforts and time.

Table 1. Summary profile of interview interviewees online and offline.

For our first interviews, 4 respondents were recruited from berry-collecting farmlands and 7 were recommended by previous participants using snowball sampling techniques. These interviews were conducted face-to-face. The COVID-19 restrictions in 2022 made it difficult to recruit and interview new participants face-to-face. To address this challenge, the later 13 participants were found and recruited via social media, where they actively shared and commented their berry-picking experiences. For these participants, we opted for video-conference calls as a widely accepted option among Chinese, providing a stable communication tool for interviews with no time limits. Selecting participants via social media may have created a bias towards recruiting younger ones, who are more used to interact in social media. This is further discussed in the limitations of the study.

The age of the interviewees ranged from 21 to 44 with a mean age of 32. The majority (88%) were female. All interviewees were Chinese living in Hangzhou and Ningbo cities. Most interviewees (88%) were married. Approximately half of the married interviewees (52%) had one child, and a third of married interviewees had two children. The mean number of children per married participant was 1 ().

2. 3. Data analysis

We mainly employed an inductive reasoning procedure to derive meanings from the consumer dataset. After interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated from Chinese to English, we read through the transcripts several times to familiarize ourselves with the data. We identified potential points of interest and initially coded for micro differences, which led us realize that at 20 interviews, we had reached a point where no new meaningful code could be developed. Four additional interviews were then conducted to confirm the data saturation. Then, we made situated, interpretive judgments to stop coding and moved on to theme generation. Given the research aims, we noted initial patterns on ‘berry-picking behavioral patterns’ and ‘influencing factors’. After carefully reviewing the codes and dataset, we accepted ‘berry-picking behavioral patterns’ as the first theme. At the same time, we became more interested in latent meanings underpinning ‘influencing factors’, leading to a more conceptual analysis. We identified a logic which appeared to capture distinct yet complementary concepts around ‘influencing factors’ and finally settled on a structure with three subthemes: consumer motivations for berry-picking, social media marketing and convenience, and service capability, each capturing a significant aspect of ‘influencing factors of urban consumer experience’. Throughout the process, we held meetings to discuss theme development, facilitating peer debriefing and exchanging thoughts. To enhance credibility, we employed triangulation techniques (Collis and Roger Citation2014), including visiting recommended picking farms, familiarizing ourselves with local dialects, and sending transcripts back to interviewees for consistency checking, as well as cross-checking by the research team.

3. Results and discussion

The first theme, ‘berry-picking behavioral patterns’, is primarily composed of codes related to picking behavior, reflecting the different types of participation which consumers experienced in berry-picking activities. The second theme is made up of three subthemes discussed separately (each capturing a meaningful aspect of the influencing factors of urban consumer experience): motivations, social-media marketing and convenience, and service capability.

3.1. Theme 1: berry-picking behavioral patterns among urban consumers

The analysis revealed that participants were involved in three distinct berry-picking experiences: wild picking, and two other practices involving commercial berry-picking farms ‘U Pick’, and ‘Pick & Plus’, each involving different actors as depicted in .

Figure 1. Three berry collecting models with various actors involved.

Wild berry-picking entails the collection of berries in natural settings without guidance, leveraging individual capabilities and experiential knowledge. In this context, ‘wildness’ denotes fruits that are minimally managed and receive scant attention from landowners. Wild picking offers a unique and refreshing experience, contingent upon the participants’ knowledge and skills. It requires the awareness of the appropriate picking season, fruit knowledge, and access to wild berries, and is more suitable for experienced berry-pickers. This is not much different from most foraging activities in the forests in northern European countries (Pouta et al. Citation2006; Margaryan and Stensland Citation2017). As Interviewee 3 recounted, she would conduct preliminary scouting to ensure the berries’ availability before taking her boys on a foraging excursion. As interviewee 7 indicated, a successful wild picking activity needed more skills and experience (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file).

In the ‘U-Pick’ practice, berries are cultivated by berry farmers in rural fields and plantations, and consumers are invited to harvest berries in these sites. Interviewees picked fresh berries by themselves, and paid berry farmers for a price based on the weight of the berries they picked. Participants often drove a short distance to reach the picking locations. Due to the lack of service amenities such as restrooms, most participants typically returned home immediately after picking, without engaging in additional activities. They had high expectations regarding taste and quality, some will proactively contact farmers at the picking hubs to confirm the condition of the fruits. Interviewee 1 mentioned that because rainfall would significantly impact the taste of cherries, she usually called ahead to inquire about the sweetness of the cherries.

Comparatively, ‘Pick & Plus’ activity involves additional facilities and service. These farmlands provide an assortment of facilities and activities that extend beyond berry-picking, such as outdoor exercise equipment, barbecue facilities, educational services on berry knowledge, and a variety of berry-themed handmade snacks and crafts for sale (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file). The interviewees disclosed that these activities are often managed by more professional organizations, rather than by individual farmers. In this context, berries are positioned as regional products (Rovira et al. Citation2022), deeply connected to the local environment and culture, and generating a spectrum of diverse demands (Weiss et al. Citation2020). Such experiences share some similarities with nature-based tourism in Norway, where individuals purchase activity packages and rent professional equipment, while instructors provide accommodation and meals (Tangeland Citation2011).

3.2. Theme 2: consumer motivations for berry-picking

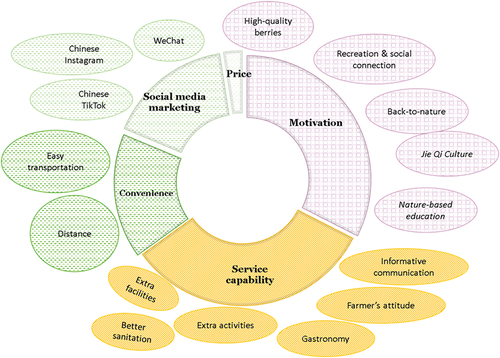

We noticed urban consumers’ motivations were multifaceted and diverse through the analysis. Participants often have multiple motivations. We identified five distinct motivations: high-quality product, recreation and social connection, back-to-nature, Jie Qi culture, and nature-based education (illustrated in ).

Figure 2. Themes and subthemes capturing influencing factors of berry-picking experience among urban consumers.

The data indicated that almost all consumers were motivated to taste high-quality berries. Furthermore, it showed that consumers’ assessments of quality were not based on the sweetness of the berries. In fact, sweetness was not always expected from fresh berries, and therefore did not significantly influence people’s overall acceptance of the berries. Rather, freshness, tastiness and food safety were reckoned as the true indicators of berry quality. Some interviewees expressed that berries they picked themselves were perceived as safer and healthier. Interviewee 6 also preferred picking wild berries rather than commercially planted ones due to the absence of pesticides. The demand for safe, fresh, and high-quality berries has been corroborated by numerous other studies, such as those by Rozin (Citation2005) and Dickson-Spillmann et al. (Citation2011). In contrast to berries sold in fruit stores, most interviewees exhibited greater trust in berry picked on farms by themselves, where they can physically assess growing conditions. The trust in the berry farm enhances the overall experience (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file). This underscores the potential of small-scale berry farms in local markets in suburban or rural regions (Polman et al. Citation2004).

The second key observation was that the berry-picking activity was often prompted by family and friends gathering for leisure and enjoyment. In almost all cases, interviewees were found to have enjoyed harvesting with family members and friends (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file). Some even extended their berry-picking invitations to their coworkers. As interviewee 3 suggested, she would also invite her friends’ families to participate in strawberry-picking. In fact, many interviewees treated commercial berry-picking as a day-trip family activity. The motivation to strengthen the bond with family members and friends could align with the berry-picking as a family activity in Nordic country (Pouta et al. Citation2006) and the purpose of rural tourism in China (Cheng et al. Citation2020). In fact, many studies in tourism-related topics, from Global East (Packer et al. Citation2014; Cheng et al. Citation2020) to West (Tangeland Citation2011; Räikkönen et al. Citation2023), emphasize the importance of social motivations.

In addition, our data further indicated that a back-to-nature concept encouraged urban citizens in berry-picking activities. Phrases such as ‘nature,’ ‘fast-paced life,’ and ‘busy’ frequently appeared during the analysis, reflecting a preference among interviewees to slow down and adjust their life rhythms by visiting and picking berries in the countryside. The restrictions instituted by the local government on long-distance travel during the COVID-19 pandemic heightened the desire of urban citizens for nature-based activities, particularly in the form of short tours in nature, making berry-picking an ideal option. As such, interviewees 5 expressed their agreement with this sentiment (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file).

It should be noted that in the current analysis, we distinguish between recreational motivation and motivation to treat berry-picking activities as family activities, particularly for urban families with young children. For these families, the experience of being close to nature and receiving nature education is especially crucial. As Cheng et al. (Citation2020) pointed out, Chinese parents value the agricultural experiences provided by suburban farms. However, for urban residents with limited access to forests and farms, there is a concern about their children’s disconnection from nature due to urbanization and the prevalence of technology. Previous research, such as that by Ma et al. (Citation2021), suggests that children confined indoors with limited outdoor activities and social interactions are at risk of negative psychological effects. In response to these concerns, and to counteract the adverse impacts of COVID-19, parents in our study actively sought to foster a closer bond with nature for their families. Berry-picking served as an activity that allowed children to disconnect from electronic devices, immerse themselves in nature, and learn about its workings. This has made ‘maintaining close relationships with children’ and ‘revisiting nature education’ strong motivators for parents to participate in berry-picking (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file). Comparatively, wild berry picking for a family’s own use in Nordic countries serves more as a leisure activity, driven by their culture, long traditions, and the usage of summer cottages (Pouta et al. Citation2006).

In addition, during the interviews, we also observed a repeated term, Jie Qi, the Chinese lunar counting of the days with 24 Solar Terms. Jie Qi specifically indicates when to sow and harvest throughout the year (Chen et al. Citation2023). Our data showed that berry harvests was closely intertwined with Jie Qi. Berry-picking interviewees had to follow the law of nature and pick different fruits and berries at different solar times. In effect, some interviewees regarded their berry-picking behaviour as a symbol to revisit and pay tribute to the traditional nature-respecting lifestyle and Chinese Jie Qi culture. Hence, picking fresh berries is of unique cultural importance to urban citizens in China and must not be overlooked.

3.3. Theme 3: social media marketing and convenience

The ‘social media marketing’ efforts of berry farmers and the ‘convenience’ associated with the activity are two related factors influencing urban consumers, in particular in their choice of berry-picking sites (illustrated in ).

Almost all participants, interviewed on site or online, relied on social media platforms to locate and pre-examine berry-collecting farms. The way social media impacted consumer choice differed slightly. Some interviewees actively searched for reviews of farmlands on social media, such as Little Red Book (Chinese Instagram). They might care more about the abundance of activities, the overall experience and service offered (see respondents comments in Appendix 2, supplementary file).

Other berry collectors noticed picking information when friends’ posted recommendation on social media. Compared to algorithm-driven advertisements on social media platforms, such as the Chinese TikTok, personal recommendation published on private messaging platforms (i.e., WeChat) seemed more effective for these collectors. Several interviewees suggested that they would add farmers’ contacts on WeChat if they were satisfied with the berry-picking experience to receive the latest information on berry products. They could even order fresh berry products and additional homemade local specialties directly from WeChat if they had no time to pick berries in person.

Overall, many interviewees enjoyed the convenience brought by social media to reserve the picking place and to communicate effectively with farmers. Social media have made it possible for berry farmers to reach a broader consumer base. Such a new form of publicity offers an alternative mechanism for berry marketing and allows both urban consumers and farmers to exchange information, and voice their expectations. It encourages the involvement of smallholder farmers in the market and establishes links between urban and rural areas (van der Ploeg Citation2014), and thus is important in territorial marketing.

Convenience is another key concept here. One frequently cited word in our data was ‘distance’. While reviews on product taste, commercial picking prices, farmer services, and the diversity of extra activities were mentioned, the convenience brought by closer distance and easy transportation were critical for both wild and commercial berry-picking. Almost all interviewees highlighted the importance of time savings and convenience when evaluating the place to go picking. Interviewees 2, 4 and 5 suggested that wild berry picking bases they had been to were close to their homes, within walking distances of less than thirty minutes. In general, interviewees accepted a driving distance of one to one and a half hours at most. For adults with busy work and for families with children, leisure time is cherished. Therefore, berry farms close to the city are preferable.

This highlights the strong potential of the emerging formation of the territorial agrifood opportunities or the nested market in suburban regions, where the market is socially constructed and organized based on social interactions between producers and consumers (Polman et al. Citation2004; van der Ploeg Citation2014). Just as for nested markets, small farmers of berries seek fair and sustainable ways of marketing their products.

3.4. Theme 4: service capability

The term ‘service’ was frequently mentioned by participants, especially when they elaborated on their experience. They suggested that there was more room to enhance the service-related experience. Therefore, we explored further participants’ expected service during the berry-picking activities. Wild berry-pickers clearly aimed at capturing and sharing moments in nature, beyond their quest for high-quality berries. Limited service was required. For ‘U Pick’ consumers, a positive experience was contingent on the farmers being welcoming, transparent, and confident about their fruits. The majority of consumers we interviewed expressed a desire for more customer-oriented services from the farmers, such as informative introductions to the berry-picking process. For instance, a proper introduction to the cultivation techniques adopted by farmers and other practices in growing berries could be useful. However, not all berry farmers were naturally inclined to engage in such interactions, and a more approachable and engaging demeanor could significantly enhance the overall experience (see respondents comments in Appendix S2, supplementary file).

For berry farmlands offering premium services, consumers had elevated expectations for the quality of those services. Overall, consumers could spend much longer time on these farms, and in a way, the whole experience was recognized as a brief excursion. Consumers assumed that the price they paid involved not only the product but also related services (see respondents comments in Appendix S2, supplementary file). A good service would entail proper communication between farmers and consumers, better sanitation, good management of farms, and extra facilities and activities offered (illustrated in ).

It thus seems that just as wild mushrooms are promoted as an element of territorial branding in Spain (Amici et al. Citation2020), berries could be a more important driver of rural tourism. It has been argued that NWFP-based downstream value chains have potentially huge value, contributing to the gastronomy, pharmaceutical and tourism sectors (Martínez et al. Citation2021). Ecotourism can greatly benefit from the rising interest in wild and cultivated berry-picking and experiential activities in rural regions (Margaryan and Stensland Citation2017; Amici et al. Citation2020). While this opens up opportunities to create synergies via a territory’s products and services to expand the markets for berry-based products and experience, all actors are required to realize such synergies with berry-picking in territorial development (Rovira et al. Citation2022). In effect, distinctiveness of each berry farm could be seen as an asset. As discussed, such distinctiveness can come from different aspects, such as the features of fresh products, the unique local scenery and the price (van der Ploeg Citation2014).

4. Implications

Berries, subsuming agroforestry practices, encompassing both cultivated varieties and those growing wild in forests and other non-agricultural settings, are renowned for their trade value and functional benefits (Shackleton and de Vos Citation2022). Berries, especially cultivated ones, play a vital role in supplementing local farmers’ incomes (e.g. Huber Citation2010) and thus contributing to rural development, reflecting their provisioning ecosystems services. Our analysis further reveals that for urban consumers, these berries resemble territorial products, carrying additional cultural and social significance. Culturally, consumers’ berry picking is partially inspired by traditional Chinese culture like Jie Qi. Harvesting specific berry species in particular seasons is an integral part of this cultural tradition. Harvesting red bayberries also reflects a continuation of Chinese tradition. Socially, while berries are valued for their natural, unprocessed qualities, for urban consumers with children, berry-picking is regarded as a family activity focused on leisure and nature education. The nature education related-service, suggested by our participants, could emerge as a unique and valuable aspect of berry-picking activities in Chinese society. In a word, our findings highlight the significant experiential, cultural, and social importance of berries, which mirrors their role as cultural ecosystem services at a macro level (Milcu et al. Citation2013).

Secondly, our findings suggest ways to unlock the economic potential of fresh berries for further rural development by offering berry-picking services and leveraging social media marketing more effectively. Urban consumers have diverse expectations regarding berry quality, the convenience of picking locations, and service levels. The depth and duration of consumer participation vary depending on the type of picking experience. Berry farms should offer more inclusive and nuanced social experiences, catering to diverse needs through services. For instance, urban families with children often seek opportunities to learn about Chinese seasonal customs (Jie Qi) while connecting with nature. Berry farms that provide high-quality services and natural education opportunities can cater to demands of these families. This does not mean that all farms should apply the same positioning strategy. Individuals or organizations with berry-picking resources should design unique combinations of products and services based on local institutions, geographical conditions, networks, and facilities, to foster more effective business development.

In addition, berry farmers could more actively collaborate with surrounding networks to meet different demands of urban collectors, such as gastronomic and hotel businesses. The networks involve not only berry-based small-and-medium sized enterprises and farmers but also other social, institutional, and economic actors (Pettenella et al. Citation2007; Abtew et al. Citation2014). Creation, differentiation, and integration of networks among public and private actors are important tools for building complementarity in NWFPs activities (Pettenella et al. Citation2007). As suggested by Weiss et al. (Citation2020), supporting measures should also include the provision of information to networks and institutional structures. Offering additional services to urban consumers can help establish the distinctiveness of local farms and rural tourist attractions. It is worth mentioning that social media marketing is an essential aspect that cannot be overlooked. Traditional word-of-mouth marketing remains effective for berry farms, but social media can enhance marketing efficiency. There is a need to bring in additional, perhaps regional stakeholders (Weiss et al. Citation2020) such as local policymakers (Martínez et al. Citation2021) and informal institutions (Abtew et al. Citation2014) to contribute to development of the marketing system.

5. Conclusions

The engagement of urban consumers in berry-picking activities has remained as a relatively unexplored domain. This research has extended the discussion of berry-pickers beyond rural collectors to urban consumers to build a more holistic perspective. The results highlighted three different berry-picking experiences among urban consumers, namely wild picking, U pick and Pick & Plus. They also show that urban consumers’ motivations are diverse, including fruit quality, recreation and social connection, back-to-nature experience, connection to Jie qi culture, and nature-based education. For urban consumers with children, fresh berries were perceived as a unique regional product, and berry-picking was viewed as a family day-trip with a focus on leisure and nature education. While berries were appreciated for their qualities, participants were particularly influenced by the transportation convenience, travel distance and the visibility of berry-picking activities on social media.

This research contributes to the understanding of berry-picking activities at least in Zhejiang province of China, shedding light on the value of berries in the economic, cultural, and experiential dimensions. Emphasizing the often-overlooked cultural significance and service potential of berries, the study introduced distinct elements for business development around berry-picking activities and underscored the potential of fresh berries as territorially branded products. Small-scale berry farms would benefit from offering enhanced services to urban consumers. The research also recognized some challenges faced by small-scale farmers, suggesting the involvement of additional stakeholders to enhance overall service system. Our findings also contribute to unlocking the greater economic potential of fresh berries through ecotourism and culinary experiences.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our qualitative research. The research has been affected by the onset of the pandemic during 2021–22 in China. Specifically, the outbreak of COVID-19 has limited the capacity to conduct more in-depth face to face interviews. Participant selection process via social media for part of our respondents may have created a bias towards recruiting younger interviewees, who are more inclined to interact in social media. Our sample of 24 interviewees is dominated by young married adults with children, and a generalization of our results is not recommended. In future research, there is a need to explore more the perspectives of producers to find more effective marketing strategies to attract new customers. Potential research avenues may also include examining consumer willingness to pay for product quality attributes: exploring territorial marketing strategies for other non-wood forest products such as mushrooms or honey could be of further interest also from the supply side.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.T., A.T.; Data collection: L.T. and M.H.; Data analysis: L.T.; Writing – original draft preparation: L.T.; Writing – review and editing: L.T., A.T., L.W. and M.H.; Funding acquisition: L.T., L.W.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Angelina Korsunova for her valuable suggestions on the methodological expression and all the respondents and those who contributed during the data collection process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

To protect respondent confidentiality, the data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2024.2340450.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbe A, Brandon SE. 2014. Building and maintaining rapport in investigative interviews. Police Practice and Research. 15(3):207–220. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2013.827835.

- Abtew AA, Pretzsch J, Secco L, Mohamod TE. 2014. Contribution of small-scale gum and resin commercialization to local livelihood and rural economic development in the drylands of Eastern Africa. Forests. 5(5):952–977. doi: 10.3390/f5050952. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/5/5/952.

- Amici A, Beljan K, Coletta A, Corradini G, Constantin I, da Re R, Ludvig A, Marceta D, Nedeljkovic J, Nichiforel L, et al. 2020. Economics, marketing and policies of NWFP. In: Vacik HH, Spiecker H, Pettenella D Tome M, editors. Non-wood forest products in Europe. US: COST; p. 125–209. doi: 10.36333/k2a05.

- Cheng H, Yang Z, Liu S-J. 2020. Rural stay: a new type of rural tourism in China. J Travel Tourism Mark. 37(6):711–726. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2020.1812467.

- Chen X, Liao Y, Li Y. 2023. Following the rhythm of nature: wisdom in the 24 solar terms and the 12 constellations. In: Zhou G, Li Y, Luo J, editors. Science education and international cross-cultural reciprocal learning: perspectives from the nature notes program. Springer; p. 11–26.

- Collis JH, Roger J. 2014. Business research: a practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students. 4th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan; p. 247–272.

- Cui J, Li R, Zhang L, Jing Y. 2021. Spatially illustrating leisure agriculture: empirical evidence from picking orchards in China. Land. 10(6):631. doi: 10.3390/land10060631.

- Dickson-Spillmann M, Siegrist M, Keller C. 2011. Attitudes toward chemicals are associated with preference for natural food. Food Qual Prefer. 22(1):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.09.001.

- Government of Zhejiang Province. 2021. Zhejiang releases urbanization goals to achieve by 2025. US. http://www.ezhejiang.gov.cn/2021-05/31/c_628363.htm.

- He XC, Chen Y, Guo C. 2004. Review on Germplasm resources of Myrica and their exploitation in China. Guoshu Xuebao. 21(5):467–471. doi: 10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.2004.05.017.

- Huber FK. 2010. Livelihood and conservation aspects of Non-Wood Forest Product Collection in the Shaxi Valley, Southwest China. Econ Bot. 64(3).

- Kangas K, Markkanen P. 2001. Factors affecting participation in wild berry picking by rural and urban dwellers. Silva Fenn (Hels). 35(4). doi: 10.14214/sf.582.

- Leßmeister A, Heubach K, Lykke AM, Thiombiano A, Wittig R, Hahn K. 2018. The contribution of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) to rural household revenues in two villages in south-eastern Burkina Faso. Agrofor Syst. 92(1):139–155. doi: 10.1007/s10457-016-0021-1.

- Li YP, Jiabo, Chen L, Sun HY. 2021. China blueberry industry report 2020. Jilin Nong Ye da Xue Xue Bao. 43(1):1–8. doi: 10.13327/j.jjlau.2021.1071.

- Ma Z, Idris S, Zhang Y, Zewen L, Wali A, Ji Y, Pan Q, Baloch Z. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on education and mental health of Chinese children aged 7–15 years: an online survey. BMC Pediatr. 21(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02550-1.

- Margaryan L, Stensland S. 2017. Sustainable by nature? The case of (non)adoption of eco-certification among the nature-based tourism companies in Scandinavia. J Cleaner Prod. 162:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.060.

- Martínez I, Maltoni S, Picardo A, Mutke S. 2021. Non-wood forest products for people, nature and the green economy. Recommendations for policy priorities in Europe. A white paper based on lessons learned from around the Mediterranean. doi: 10.36333/k2a05.

- Milcu AI, Hanspach J, Abson D, Fischer J. 2013. Cultural ecosystem services: a literature review and prospects for future research. Ecol Soc. 18(3):3. doi: 10.5751/ES-05790-180344.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. 2017. Thematic analysis. Int J Qual. 16(1):160940691773384. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Packer J, Ballantyne R, Hughes K. 2014. Chinese and Australian tourists’ attitudes to nature, animals and environmental issues: Implications for the design of nature-based tourism experiences. Tourism Manage. 44:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.02.013.

- Pettenella D, Secco L, Maso D. 2007. NWFP&S marketing: lessons learned and new development paths from case studies in some European countries. Small-Scale For. 6(4):373–390. doi: 10.1007/s11842-007-9032-0.

- Polman NBP, Schansvander J W, PloegvanderJ D, Poppe JL. 2004. Nested markets with common pool resources in multifunctional agriculture. Rivista di economia agraria. 65(2):295–318.

- Pouta E, Sievänen T, Neuvonen M. 2006. Recreational wild berry picking in Finland-reflection of a rural lifestyle. Soc Natur Resour. 19(4):285–304. doi: 10.1080/08941920500519156.

- Räikkönen J, Grénman M, Rouhiainen H, Honkanen A, Sääksjärvi IE. 2023. Conceptualizing nature-based science tourism: A case study of Seili Island, Finland. J Sustainable Tourism. 31(5):1214–1232. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1948553.

- Rovira M, Garay L, Górriz-Mifsud E, Bonet J-A. 2022. Territorial Marketing Based on Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFPs) to enhance sustainable tourism in rural areas: a literature review. Forests. 13(8):1231. doi: 10.3390/f13081231.

- Rozin P. 2005. The meaning of “natural”: process more important than content. Psychol Sci. 16(8):652–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01589.x.

- Seeland K, Kilchling P, Hansmann R. 2007. Urban consumers’ attitudes towards non-wood forest products and services in Switzerland and an assessment of their market potential. Small-Scale For. 6(4):443–452. doi: 10.1007/s11842-007-9028-9.

- Shackleton CM, de Vos A. 2022. How many people globally actually use non-timber forest products? For Policy Econ. 135:102659. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102659.

- Tangeland T. 2011. Why do people purchase nature-based tourism activity products? A Norwegian case study of outdoor recreation. Scand J Hosp Tour. 11(4):435–456. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2011.619843.

- van der Ploeg JD. 2014. Newly emerging, nested markets: a theoretical introduction. In: Hebinck SSP van der Ploeg JD, editors Rural development and the construction of new markets. US: Routledge; p. 16–40.

- Wang Q, Huang Z, Gao C, Ge Y, Cheng R. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Rubus hirsutus Thunb and a comparative analysis within Rubus species. Genetica. 149(5–6):299–311. doi: 10.1007/s10709-021-00131-9.

- Weiss GE, Marla R, Corradini G, Živojinović I. 2020. New values of non-wood forest products. Forests. 11(2):165. doi: 10.3390/f11020165.