ABSTRACT

Introduction

UK undergraduate medical curricula are under pressure to become more community-focused and generalist in approach to equip all future doctors with generalist skills and increase recruitment to generalist specialities like general practice. However, the amount of general practice teaching in UK undergraduate curricula is static or falling. Undervaluing, in the form of general practice denigration and undermining, is increasingly recognised from a student perspective. However, little is known about the perspectives of academics working within medical schools.

Aim

To explore the cultural attitudes towards general practice within medical schools as experienced by general practice curriculum leaders.

Methods

A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews of eight general practice curriculum leaders in UK medical schools. Purposive sampling for diversity was used. Interviews were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Findings

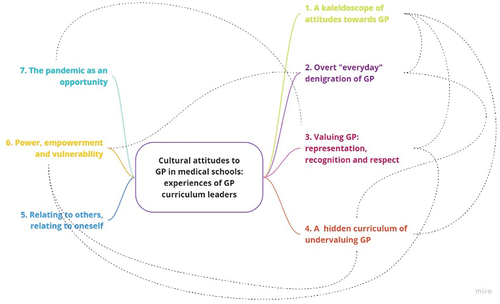

Seven themes were identified covering ‘a kaleidoscope of attitudes towards general practice’, ‘overt everyday denigration of general practice’, ‘a hidden curriculum of undervaluing general practice’, ‘valuing general practice: representation, recognition and respect’, ‘relating to others, relating to oneself’, ‘power, empowerment and vulnerability’, and ‘the pandemic as an opportunity’.

Conclusions

Cultural attitudes towards general practice were diverse: a spectrum varying from valuing general practice to overt denigration, with a ‘hidden curriculum’ of subtle undervaluing of general practice. Hierarchical, tense relationships between general practice and hospital were a recurring theme. Leadership was identified as important in setting the tone for cultural attitudes, as well as indicating general practice is valued when general practitioners are included within leadership. Recommendations include a shift in narrative from denigration to mutual speciality respect between all doctors.

Introduction

Medical curricula evolve over time as the practice of medicine advances and the context in which health care exists changes. Curricula are shaped not only by educational aims but also by the social, cultural and political climate in which they are written [Citation1]. Indeed, the General Medical Council (GMC) acknowledges that medical curricula must balance workforce needs with several other stakeholder interests [Citation2]. In an effort to equip future doctors with generalist skills and help increase recruitment to generalist specialities like general practice, there is a drive to make United Kingdom (UK) undergraduate medical curricula more community focused and to redress the balance between specialism and generalism [Citation2–4]. In contrast to the intended direction of change, research shows that the amount of general practice teaching in undergraduate medical curricula in the UK has plateaued since 2000 and currently falls significantly short of recommendations [Citation5]. Figures in Europe are even lower [Citation6].

The stark dichotomy between intended and actual curricula for undergraduate general practice teaching could reflect undervaluing of general practice. Cultural undervaluing of general practice is increasingly recognised within UK medical schools in both clinical and academic contexts, in the form of medical speciality undermining and denigration [Citation7–11]. Speciality ‘bashing’ forms a significant part of a medical school’s hidden curriculum and can send powerful messages about the importance, respectability and status of a speciality [Citation7,Citation12]. While there is increasing understanding of medical student perspectives of cultural undervaluing of general practice in UK medical schools, little is known about the perspectives of those working in the medical school itself: academics and educators. In particular, the perspectives of general practice curriculum leaders (GPCLs) are important to understand given their power to influence the formal, informal and hidden curriculum: this study aims to add to existing research by exploring these perspectives. Faculty perceptions of organisational culture in medical schools appear to be a relatively under-researched area, with minimal UK-based research and no published studies examining institutional culture with respect to particular specialities such as general practice.

We aimed to explore cultural attitudes towards general practice within medical schools as experienced by UK GPCLs. Medical school culture and cultural attitudes towards general practice are seen in this inquiry as subjective individually experienced phenomena, situating this work within relativist ontology, subjectivist epistemology and a constructivist paradigm [Citation13].

Methods

Culture is a complex and abstract social construct, with many different definitions. Organisations can also be considered through different analytical frameworks [Citation14]. Debate in the literature regarding the definition of organisational culture, and the appropriate research paradigm with which to study it, is well recognised [Citation15]. For the purposes of this work, organisational culture was defined as the values, beliefs, attitudes, practices and behaviours which characterise an organisation, based on work by Martin [Citation15], Hofstede [Citation16] and Schein [Citation17].

The study used semi-structured interviews with GPCLs, usually named heads of general practice teaching, in UK medical schools. Semi-structured interviews allowed flexibility and responsiveness to individual participants [Citation18] while ensuring relevance to the research question by using an interview guide with topic areas and suggested questions. The interview guide was based on the previous literature [Citation5–12] and refined following a pilot interview. Interviews were recorded using the online teleconferencing software Zoom [Citation19], which was used for audio recording and basic transcription.

Maximum variation sampling was used in this study in order to involve participants from medical schools diverse in age, location and other characteristics. A previous quantitative cross-sectional questionnaire study achieved a 100% response rate from GPCLs in all 36 medical schools in the UK [Citation5]. When asked to consent to be invited to participate in a follow-on qualitative study, 33/36 respondents agreed. An invitation email with participant information sheet was sent to these 33 GPCLs, 15 expressed interest in taking part. Eight participants from different medical schools were purposively selected based on the characteristics of participants’ medical schools (summarised in ); individual characteristics have not been included in order to protect anonymity.

Table 1. Summary of the characteristics of participants’ medical schools.

Basic automated transcription from Zoom recordings was reviewed and amended as necessary using the principles of orthographic transcription [Citation20]. Interview transcripts were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis [Citation21], reflecting the philosophy underpinning qualitative research, valuing researcher subjectivity and viewing knowledge as contextual. NVivo software [Citation22] was used to facilitate the coding process.

In qualitative research, subjectivity is valued and the researcher’s worldview is reflected in their research; yet, acknowledgement of how researchers’ personal biases may shape research is essential to good qualitative research [Citation20]. The researchers in this study are a general practice speciality trainee and a professor of general education. Both have an interest in medical education and educational policy, and both have personally experienced general practice denigration and undervaluing in both educational contexts and the workplace. However, while being cognisant and transparent about our bias, the researchers attempted to prioritise the beliefs and views of the participants. While considering personal biases, the researcher upheld rigour by considering Lincoln and Guba [Citation23] indicators of trustworthiness in qualitative research – credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. Specific strategies to uphold rigour included prolonged engagement with the data, a transparent and explicit audit trail, thick description, member checking and use of a reflexive stance. Triangulation to explore multiple perspectives on the phenomenon was achieved by recruiting diverse participants with maximum variation sampling.

Results

Eight GPCLs were interviewed, and the interviews lasted between 38 and 58 min. Seven themes were produced from the data as displayed in .

Figure 1. Mindmap of final themes.

Theme 1: a kaleidoscope of attitudes towards general practice

Participants described a spectrum of opinions regarding general practice, making it difficult to generalise a single unifying attitude towards it.

I think it depends on what you mean by medical school so, you know, medical schools are very kind of … heterogeneous and compartmentalised bodies. And obviously there are, there are kind of communities within communities in medical schools … I would say that prevailing attitudes to primary care vary enormously across those bodies so, we could probably place them on a spectrum.

In addition to this diversity in attitudes, participants felt that opinion is dynamic, often changing to be more positive towards general practice.

… like lots of groups general practices are often stereotyped and, there are some old fashioned people who think general practice is an easy option … I think that is changing albeit, you know very, very, very slowly … I think there is an increased recognition of the complexity of general practice

Some participants felt that negativity towards general practice was at the level of individuals, rather than a shared cultural attitude, while others interpreted the lack of conspicuous denigration to be an indicator of positivity towards general practice.

Theme 2: overt “everyday” denigration of general practice

While it was acknowledged that negativity towards general practice is not universal, participants described an atmosphere where explicit denigration of general practice has become normalised and, in some cases, accepted within their medical schools.

… if you said to someone: ‘Do people think negatively towards general practice?’ ‘Yes, they do’ everyone will come probably just shrug their shoulders and say: ‘Well that’s no real big fish, there’s no real news there is there, we all kind of know that exists’.

Within medical schools, clinicians were felt to be the main group from which overt denigration of general practice was originating. However, negativity towards it was not felt to be a phenomenon unique to the medical school environment. There was a strong sense from all participants of how denigration in the wider community and media permeates into medical school culture.

I think generally, culturally in the UK, there is an undervaluing of general practice so that does seep into the views of the staff at X [our medical school]*. And I think that’s, you just can’t get away from that.

General practice is facing an onslaught of negativity from the press and from the government as well. And so obviously that’s going to infiltrate everybody’s perception of primary care … I think you know I think we have to acknowledge that there has been, and continues to be undertones of negativity towards general practice but not, not just within the medical schools, but within society.

Participants also noted that it was often students, rather than staff, bearing witness to general practice denigration: expressing concerns about the impact of the normalisation of general practice denigration upon students.

But I think it’s when you speak to the students about their experiences of what people say about general practice, that it is sometimes quite shocking actually, you know: ‘Oh! That stupid GP [general practitioner] has sent this patient in, why have they done that, you know why haven’t they done this, that or the other thing’ or, ‘This is a dreadful referral!’ (Participant 7).

And the worry, you have is these are people who were also teaching medical students who might say things without us realising like the, ‘just a general practitioner’, or mention something, perhaps a referral letter or something that would just knock general practitioners, and obviously the effect on students that can be huge. And how students perceive general practitioners then. It also comes from your, you know your teachers, the people you respect in the medical school … but you know all you need is a few clinicians who perhaps don’t have a particularly high regard for general practice and, and you know, those flyaway comments, they might say them without actually realising the effects of them. (Participant 8)

Theme 3: valuing general practice: representation, recognition and respect

Despite explicit general practice denigration being commonly recognised by participants, many identified ways in which they saw general practice being valued. Participants perceived inclusion within decision-making, or representation of general practitioners within staffing, particularly leadership positions or positions of power as compelling markers of valuing general practice.

I do genuinely feel that my expertise is sought, my input is valued, and I’m included and intentionally so, and so I think generally, it is positive, and I do really think that the medical school from the Dean down is pro general practice. (Participant 1)

… many of us in the general practice team are involved in other parts of the medical school, other programmes and, so we’re valued and also were invited to the important meetings to talk about curriculum development or delivery and in the meetings we’re included fully in conversations… (Participant 5)

I think we’re very much valued, I think, because we, because there’s a quite a high percentage of general practitioners who have academic roles, teaching roles within the university, I there’s a, yeah there’s certainly feeling of respect there. (Participant 8)

Participants discussed representation within the curriculum as an important sign of valuing general practice. In some cases, the curriculum had been designed to heavily feature general practice; in others, incorporating more general practice into the curriculum had been a more recent development. Positive feedback about general practice teaching, from students and staff alike, was seen by some participants as an indicator of valuing general practice.

Theme 4: a hidden curriculum of undervaluing general practice

Participants described a constant undercurrent of negativity towards general practice in medical school culture, taking the form of undervaluing, marginalisation, microaggressions and covert general practice denigration. Participants often described ways in which general practice was seen to be inferior or substandard.

I think there is a subtle, and it’s very difficult to pinpoint, a subtle sense that, although my non-general practice colleagues that I interact with at the medical school respect us as a teaching group they see us as being an unusual group of ‘intelligent’ general practitioners compared to the rest of them out there who are sort of you know, the ‘ordinary’ ones. (Participant 4)

General practice was perceived to be an inferior speciality, whereas hospital medicine was treated as the ‘default’ or ‘native’ health-care setting in medical school culture, with general practice being viewed as an outlier. General practice was seen to be external to the ‘norm’ of hospital medicine and perceived to have a lower status and be less valuable than specialism.

I think the prevailing way people approach medicine, I think is still seen through the lens of a sitting in a hospital clinic or on a ward … The community is seen as a very separate place … in terms of the medicine in both they are still very separate cultures are different and the culture is, culture is very specialist focus really still. (Participant 4)

And then there’s the perceptions … the perception that general practice is just a second rate specialty … the perceptions of: ‘Well, I’m a specialist, so therefore, you know, I know something that’s very, very specific and I can do, you know, a lot of tests and various other things to get a specific diagnosis’. Whereas general practice is all about, you know, the more superficial woolly stuff that kind of perception, whereas actually it’s quite difficult, and it’s all about undifferentiated care …. (Participant 2)

Participants described microaggressions in the form of acts and behaviours which imply a negative or hostile attitude towards general practice. Microaggressions included an incongruence between espoused medical school values and values implied by actions, a perceived culture where concerns about general practice denigration are minimised or denied and structural and financial barriers or discrimination against general practice

… in our institution, for example, a consultant will automatically pretty much automatically be offered a position in the Medical School at senior lecturer level, whereas a GP wouldn’t, they’d be offered a lecturer level and then have to go through quite a rigorous set of, you know, meet a rigorous set of criteria in order to meet senior lecturer level … , if you’re teaching within a hospital environment. … then there’s a set of criteria that the University has awarded an honorary senior lecturer status. That document does not mention general practice anywhere within it, it talks about consultants and specialists … (Participant 7)

General practice could be marginalised in medical school culture: some participants cited occasions where it felt to them that general practice was treated as an afterthought, something secondary to the main work of the medical school.

Or when you’re looking at, for example, curricular changes and stuff, general practice is always the specialty that’s the afterthought you know. (Participant 2)

Some participants felt that general practice is underrepresented within medical school staffing and taught curriculum, echoing the sense of inequality of general practice's voice within the medical school infrastructure. Finally, participants reflected on a fundamental lack of understanding, and in some cases, ignorance, about the nature of general practice from colleagues and students alike. This lack of understanding of general practice was linked by participants to a lack of exposure to it, in part due to a historical paucity of general practice in medical education.

… there are a very small number of people at very senior levels within the course who don’t have any experience in general practice and haven’t ever sort of taken the time to find out exactly how it works, who sometimes come out with statements that you think: ‘Hang on a minute, you really just don’t understand how general practice works’. (Participant 6)

Historically, the amount of time, kind of, the curriculum is spent within general practice, it’s tiny. So therefore, people’s exposure to general practice in staff or an institution is quite small. So people’s understanding of what is general practice, and who are general practitioners and what their role is, is actually very, very limited. … And so actually, there is no kind of appreciation of general practice or, or an awareness of what their profession involves and experience in that. So, people I think are probably quite ignorant to general practice. (Participant 2)

Theme 5: relating to others, relating to oneself

Themes described so far relate to a diverse range of experiences regarding medical school culture towards general practice. Some participants discussed the concept of difference and raised examples of how individuals or groups can be ‘othered’ due to being perceived as not aligning with social norms. This can contribute to an ‘in’ and ‘out’ group mentality rather than cohesiveness and inclusivity.

… in the medical world, in the medical society, I think GP’s and other specialties - it’s not just about general practice, there were other specialties, psychiatry being one of them as well which is seen as: ‘You’re different’, you know and as a result of that you’re not one of ‘The clan’ and then that results in different behaviours and attitudes. (Participant 2)

Closely related to the concepts of ‘othering’ and difference are those of belonging and tribalism. Participants reflected on how it can be difficult to feel a sense belonging even within the professional group to which they identified with, exacerbated by logistics of working in a large team spread over different working days and a large physical space.

Many participants disclosed feelings of inadequacy, imposter syndrome and self-doubt, sometimes reflecting on how intertwined the internal narrative is with past and current experiences.

It’s that sort of just a GP thing … you regard yourself as being in some sort of slow lane career compared to … ‘Oh! So you couldn’t be a specialist?’ It’s that sort of, there is a, an inferiority complex, sometimes in primary care, in primary care medicine as a specialty I think. (Participant 4)

It’s hard to know how much is my own internal narrative, and how much is that that I’ve experienced … I do still find myself thinking: ‘I am just a GP’ and, and I don’t know why I’ve got that internal narrative because I don’t actually think that … actually some of the kinds of: ‘Secondary care is better and best’ is actually coming from within. (Participant 3)

Several participants identified that, alongside self-denigration and negativity towards general practice from others, a victim mentality can exist which was perceived by participants to be unhelpful in improving the current culture towards general practice.

Theme 6: power, empowerment and vulnerability

Throughout the interviews, a theme of power became evident: participants alluded to where the balance of power lies in medical school culture and dynamics and the abuse of power in interactions perceived as intimidation and bullying. Several participants mentioned concerns about anonymity during the interviews, implying a sense of vulnerability when discussing medical school culture towards general practice.

Most participants used language which implied a conscious or subconscious need to defend or protect general practice. They used expressions describing themselves as ‘the watchdog on duty’, or being ‘at loggerheads’ and in ‘constant battle’ in decision-making affecting general practice, and having to ‘constantly bang the drum’ and ‘being careful with using the ammunition’.

I think things are changing but it’s still a bit of an uphill struggle … it’s more the case of how we battle to get that status, equality of status, I think, I think … it seems like you know we have to be constantly banging a drum about. this (Participant 4)

Theme 7: the pandemic as an opportunity

When talking about the changes to general practice in medical schools since the COVID-19 pandemic, participants spoke about the pandemic as an opportunity to display the strengths of general practice in various forms. Some participants spoke proudly of how general practice stepped up to the challenges of the pandemic:

And you know it was tough but general practitioners just pulled out all the stops, they were, they have been, they are incredible. (Participant 5)

A common theme raised by participants was how the pandemic allowed general practice to demonstrate their adaptability to change, particularly in adapting to new methods of teaching. Some participants described ways in which the pandemic allowed general practice to act as pioneers, leading the way in innovations in teaching. Other participants described how general practice teaching changed over the pandemic to encourage more authentic contributions from medical students. One participant spoke about how the pandemic was a catalyst for enacting changes to make general practice more prominent in the curriculum.

Discussion

GPCLs perceived the views of general practice to be diverse and dynamic, within and between medical schools and beyond, a kaleidoscope of opinions. Participants found it hard to generalise a ‘prevailing opinion’ of general practice in their medical schools, rejecting a homogenous integration perspective and more reminiscent of differentiation and fragmentation perspectives on culture [Citation15]. It was clear from individual participant accounts that perceived cultural attitudes towards general practice vary between institutions.

Overall, GPCLs perceived widespread denigration of general practice which has become normalised within medical schools and mainly originates from clinicians. This fits with the student experience of general practice denigration reported in Destination GP, where 70% of students by their fifth year had experienced negativity towards general practice within the clinical environment [Citation8]. Overt general practice denigration was perceived to occur more pervasively throughout society and the media, again tallying with existing literature [Citation7,Citation24,Citation25].

Conversely, many participants identified the valuing of general practice in their medical school cultures. Leadership was seen to be particularly important in perceived valuing of general practice, both in terms of participants perceiving senior leaders in their medical schools as valuing general practice and in terms of seeing general practitioners themselves represented in positions of power and included in decision-making. Other markers of valuing identified by participants were representation within the curriculum, positive feedback and an appreciation of expertise unique to general practice.

Beneath the conspicuous denigration and valuing of general practice, participants described a constant undercurrent of negativity towards it in medical schools: a hidden curriculum of undervaluing and covert denigration. Participants described examples of undervaluing of general practice in all four of Hafferty’s [Citation26] areas where the hidden curriculum can be uncovered: policy, evaluation and assessment, resource allocation and language. In alignment with the wider literature, the hidden curriculum described by GPCLs bore lessons about hierarchy in medicine and speciality denigration [Citation27,Citation28].

A clear divide within medical school culture between hospital/specialism and general practice/generalism was described by GPCLs leading to a sense of ‘us and them’, tensions and sometimes conflict, in keeping with the ‘in-group’ or ‘out-group’ of social identity theory [Citation29]. GPCLs perceived hospital/specialism to be dominant, more highly valued and higher status than general practice/generalism.

GPCLs who perceived a supportive and inclusive medical school culture towards general practice viewed the culture as a positive, motivating influence on their work. Participants who perceived more hostile or negative cultural attitudes towards general practice described frustration and conflict in their work as a consequence. The influence of medical school culture towards general practice can be explained in relation to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: a hostile, negative environment threatens basic safety needs, whereas an inclusive, supportive environment where general practice is afforded recognition, respect and status meets the higher levels of belonging and esteem [Citation30].

GPCLs spoke about the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to display the strengths of general practice and, as a result, an increase in cultural valuing of general practice in medical schools. Participants' observations of how general practice teaching changed are reflected in the wider literature of change to medical education over the pandemic [Citation31], such as innovating new teaching methods.

Strengths and limitations

The focus of our study is relevant and topical, and the academic perspective is underexplored. Our methodology is coherent with the study’s theoretical underpinning, and rigour was upheld appropriately. We acknowledge that we have sampled from a single stratum of hierarchy, and collecting data from other sources such as focus groups, participant observation or examination of artefacts would have provided data source triangulation and may have shed light on different perspectives [Citation32]. We acknowledge that due to the researchers’ backgrounds and experiences outlined in the methods section, we may have focused on negatives rather than positives in the data.

Conclusions and implications

GPCLs described a spectrum of attitudes within and between medical schools, varying from overt denigration to valuing general practice. Overt denigration was felt to originate from clinicians, with the predominant audience being medical students in hospital settings. A more subtle undercurrent of general practice undervaluing and denigration in medical school culture was identified, bringing a new perspective to the body of the literature regarding general practice denigration and medical school hidden curricula which is to date has been from the medical student viewpoint. Further research such as the use of ethnography would allow integration of the perspectives of multiple cultural members, including students and university staff alike, and provide a deeper insight into medical school culture towards general practice. The importance of leadership resounded, with leaders supportive of general practice and appointment of general practitioners to positions of power being markers of valuing. This should be noted by medical school policy and decisions regarding appointment and promotion of senior leaders.

Tensions, hierarchy and conflict between general practice/generalism and hospital/specialism were a recurring theme. Given the GMC’s Duties of a Doctor emphasised how doctors must work collaboratively and respectfully with colleagues, it is time for the narrative to shift towards nurturing a culture of teamwork and mutual respect of all specialities in medicine.

Contributors

EC and HA came up with and designed the study, EC undertook the interviews and initial coding, both authors developed the themes, EC wrote the first draft and both authors refined and agreed to the final draft of the paper.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by Newcastle University Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to the participating GP heads of teaching for their time and to the national GP heads of teaching group for their support for the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Apple MW. The text and cultural politics. Educ Res. 1992;21(7):4–19. doi:10.3102/0013189X021007004

- NHS Health Education England. The future doctor programme. A co-created vision for the future clinical team; 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/future-doctor

- Council GM. Outcomes for graduates. London: General Medical Council; 2018.

- Royal College of General Practitioners Scotland. From the frontline: the changing landscape of Scottish general practice; 2019. http://allcatsrgrey. org.uk/wp/ download/primary_care/RCGP-scotland-frontline-june-2019.pdf

- Cottrell E, Alberti H, Rosenthal J, et al. Revealing the reality of undergraduate GP teaching in UK medical curricula: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e644. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X712325

- Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N, et al. Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe–a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-157

- Wass V, Gregory S, Petty-Saphon K. By choice - not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. 2016.

- Royal College of General Practitioners. Medical Schools Council. Destination GP Medical students’ experiences and perceptions of general practice. 2017.

- Baker M, Wessely S, Openshaw D. Not such friendly banter? GPs and psychiatrists against the systematic denigration of their specialties. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(651):508. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X687169

- White GE, Cole OT. Encouraging medical students to pursue general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(649):404. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X686245

- Ajaz A, David R, Brown D, et al. BASH: badmouthing, attitudes and stigmatisation in healthcare as experienced by medical students. BJPsych Bull. 2016;40(2):97–102. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.115.053140

- Allsopp G, Rosenthal J, Blythe J, et al. Defining and measuring denigration of general practice in medical education. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):205–209. doi:10.1080/14739879.2020.1768440

- Bunniss S, Kelly DR. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):358–366. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03611.x

- Reed M. The sociology of organizations: themes, perspectives and prospects. New York: Harvester; 1992.

- Martin J. Organizational culture: mapping the terrain. SAGE Publications, Inc.: 2001. doi:10.4135/9781483328478

- Brown AD. Organisational culture. London: Pitman; 1998.

- Schein EH. Organizational culture and leadership. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2016.

- O’Leary Z. The essential guide to doing your research project. Fourth edition. ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2021.

- Zoom Video Communications, Inc. 2020. ZOOM cloud meetings (Version 4.6.9).

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research : a practical guide for beginners. London: London; 2013.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? what counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- QSR International Pty Ltd. 2020. NVivo. [Updated 2020 March].

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications; 1985.

- Barry E, Greenhalgh T. General practice in UK newspapers: an empirical analysis of over 400 articles. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(679):e146–e153. doi:10.3399/bjgp19X700757

- Defend general practice - don’t denigrate and demoralise hardworking GPs’, says college chair [press release]. Royal Coll Gene Pract website. 2021.

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407. doi:10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013

- Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329(7469):770. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770

- Doja A, Bould MD, Clarkin C, et al. The hidden and informal curriculum across the continuum of training: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Teach. 2016;38(4):410–418. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1073241

- Islam G. Social identity theory. In: Teo T, editor. Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. New York: Springer New York; 2014. pp. 1781–1783.

- Ryan RM, Ryan RM. The Oxford handbook of human motivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.001.0001

- Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, et al. Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid BEME systematic review. BEME Guide No 63 Medi Teach. 2020;42(11):1202–1215. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1807484

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design : choosing among five approaches. Poth CN, editor, Fourth ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2017, International Student Edition.