ABSTRACT

After the end of World War II about 600,000 Koreans remained in Japan and quickly faced a homeland divided along ideological lines. In this context Chongryon – the General Federation of Koreans in Japan – was formed in 1955 with the support of the North Korean state. The organization advocated for Koreans in Japan, promoted a positive image of North Korea through schools and media, and acted as a gatekeeper for access to North Korea. Chongryon persists, still maintaining a university near Tokyo, a news website, and a membership of up to 30,000. Using primarily text analysis of Choson Sinbo, Chongryon’s main news website, the article explores the organization’s messaging to a unique “diaspora” population that includes second- through fifth-generation members, most of whom have never visited North Korea. Combined with historical texts, secondary literature, and interviews, this method contributes to our understanding of how authoritarian regimes seek to maintain inter-generational appeal..

Introduction

In the years 1960 and 1961 roughly 70,000 Koreans in Japan left for North Korea, thus “forsaking life in Asia’s richest country just when it was entering the period of its 1960s economic miracle” (Morris-Suzuki, Citation2007, p. 12). Expanding the timespan, in total over 86,000 Koreans “returned” from Japan to North Korea between 1959 and 1984 (ibid.). “Return” is in fact an inaccurate term, though: nearly all of them were originally from the southern part of Korea and had come to Japan before the Korean peninsula was split into the Republic of Korea (or South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) in the late 1940s. These migrants were opting into Kim Il Sung’s North Korean experiment.Footnote1 Tens of thousands of Koreans in Japan did not migrate to North Korea but still professed affinity for the DPRK by adopting its political symbols, sending their children to DPRK-affiliated schools in Japan, or attending the pro-North Korea Choson University on the outskirts of Tokyo.

The organizing force behind many of these activities was Chongryon, or the General Federation of Koreans in Japan. Established in 1955, Chongryon set up a network of schools, banks, insurance agents, a university, a publishing house, and a newspaper, the Choson Sinbo, all with the help of the North Korean government. Although much diminished in capacity and appeal since its peak in the 1960s, Chongryon survives to this day and Choson Sinbo continues to publish a news website.

This article is about how Chongryon has sought to remain relevant to the North Korean “diaspora” during its nearly seven decades of existence. It traces the changing strategies of the organization as generations turned over by using two methods. First, using case study analysis drawing on secondary literature and interviews conducted in Japan by one of the authors in 2019, the article identifies how Chongryon reached a high point in the 1960s but that its appeals to Koreans in Japan began to fade thereafter. While the organization still exists today, it is a shadow of its former self and struggles to appeal to third, fourth, or even fifth generation Koreans in Japan. The accumulated difficulties of Chongryon’s engagement with Koreans in Japan reached a tipping point in 2002, when Kim Jong Il admitted that North Korea had kidnapped Japanese citizens during the 1970s and 1980s.

Second, the article uses quantitative text analysis methods to understand the messaging of Chongryon’s newspaper Choson Sinbo, rendered in English as The People’s Korea. The paper, published since 1961 and now a news website in Korean and Japanese, reports on the Chongryon community in Japan and contains content about North Korea and its relations with Japan.Footnote2 It can be taken as the “official” voice of the DPRK’s engagement with its erstwhile diaspora in Japan. The findings that emerge from the text analysis show that Chongryon emphasizes education and educational rights, with these topics appearing to increase in importance in recent years. This can be explained by the fact that education is the most developed pillar of Chongryon’s organization and the reality that education plays a socializing function with the potential to bind pupils to the organization. Based on Chongryon’s communications this article outlines an ideal socialization life cycle for an individual in the organization, and ultimately identifies its limitations. The article finds that Chongryon’s diaspora engagement strategy appears to rely on its education infrastructure, its self-ascribed status as a protector of Koreans in Japan, and a life-cycle process akin to North Korea’s domestic mass organization structure.

This analysis of Chongryon is important to the study of authoritarian state diaspora engagement not only because it covers a case not typically found in this literature, namely North Korea (for exceptions see Greitens, Citation2020; Greitens, Citation2023), but also because it represents a unique case in which the “diaspora” ties were built mostly using ideological appeals and not lived exile.Footnote3 This pushes us to understand not only the extent to which loyalty can be manufactured via propaganda and organizational capacity in the host country, but also importantly the limits to that approach when the ideology’s appeal fades. Looking forward, the prospects for deepened ties between North Korea and Koreans in Japan looks unlikely due to the DPRK’s unappealing domestic context and strict controls on contact with outsiders as well as the Chongryon’s organizational challenges.

“Diaspora” Engagement Over Time

Chongryon attempts to constitute and maintain Koreans in Japan as a diaspora. As the introduction to this special issue discusses, conceptualizations of ‘diaspora’ can vary (Orjuela et al., Citationforthcoming; as applied to North Korea see Greitens, Citation2020, pp. 238–240; Greitens, Citation2023), but according to the criteria of Brubaker (Citation2005:, pp. 5–7), the diaspora has features of (1) dispersion in space as a minority outside its ethnonational homeland; (2) orientation to a homeland by maintaining a collective memory and regarding the ancestral homeland as the true, ideal home and as the place to which one would (should) eventually return; (3) boundary-maintenance in the host society by preserving a distinctive national identity.

The annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 resulted in a significant wave of Korean migration to Japan. In the 1920s relaxed regulations on Korean immigration led to a notable increase in Korean labourers in Japan, primarily single men employed in sectors such as construction, mining, and manufacturing (Kang & Fletcher, Citation2006, p. 269; Morris-Suzuki, Citation2006, p. 124). Over time, their family members gradually joined them, but they faced significant racial discrimination and often settled in areas predominantly inhabited by Koreans (Kang & Fletcher, Citation2006, p. 271). The situation became more severe after the National Mobilization Law was implemented in April 1938, along with the ordinance on Korean labour immigration in September of the same year. This led to the forced relocation of many Koreans to Japan (Morris-Suzuki, Citation2006, p. 121).

On the eve of Japan’s defeat in World War II in 1945 there were about 2.4 million Koreans living in Japan (Mithcell, Citation1967, p. 102). The end of the war and the collapse of the Japanese empire, which had included the Korean peninsula since 1910, led to population reshuffling on a massive scale. By 1949, about 600,000 of the initial 2.4 million remained in Japan (Mithcell, Citation1967, p. 104). Koreans in Japan (Zainichi) were legally defined as foreigners, had few political rights, and faced employment discrimination (Lie, Citation2008, pp. 37–38).

In this context Koreans organized, but groupings bifurcated along Cold War lines because Korea was now divided between North and South (Lie, Citation2008, pp. 30–31). Geographical ties to the peninsula were often trumped by ideological affinities. In 1946, the right-leaning, anti-communist, South Korea sympathetic Mindan (Community of Korean Residents in Japan) was formed.Footnote4 After the repression of a predecessor group during the American occupation of Japan, in 1955 Chongryon was formed “under the direct control of North Korea” (Shipper, Citation2010, p. 60).

Chongryon’s aims were to promote the unification of Korea under communist rule, protect Korean rights in Japan, promote North Korean education and propaganda, and advocate for the normalization of relations between the DPRK and Japan (Shipper, Citation2010, p. 60). Chongryon’s main purpose when it came to the relationship between Koreans in Japan and the DPRK was to promote North Korea’s political positions and gain “mass support for the regime” (Ryang, Citation2016, p. 4). Chongryon’s appeal was thus built on ethnicity insofar as it was only available to Koreans in Japan, but beyond that ideology was the main goal and attraction of the organization. Those who participated in Chongryon activities maintained a strong homeland orientation by establishing North Korea as the place that shaped their mentality and identity and by engaging in a “repatriation” movement in the late 1950s. To manufacture the identity of North Koreans, ethnic (Choson) education was implemented by Chongryon, and the diaspora identity was shaped and maintained through the regional organizing activities of Chongryon (Chongryon, Citation2022a). Lastly, upholding this distinctive identity was the dividing line between Japanese and Korean residents. Sometimes resistance to unequal treatment in the host society was also manifested through various Chongryon campaigns. The crucial aspect, however, is that integration into Japanese society was not the ultimate objective.Footnote5

The “repatriation” of Koreans to North Korea starting in 1959 described briefly at the outset of this article was among the most successful outcomes of these efforts from Chongryon’s viewpoint. Because people were spurning not only Japan but also South Korea, the campaign was viewed by the North Korean authorities at the time as an ideological victory vis-à-vis South Korea in the Cold War (Morris-Suzuki, Citation2007, p. 184). To convince Koreans to relocate from Japan to the DPRK, Chongryon engaged in a concerted propaganda campaign to portray North Korea as a paradise and moving there as a patriotic duty (Mithcell, Citation1967, p. 140, 154; Ryang, Citation1997, p. 114; Morris-Suzuki, Citation2007, p. 167; Lie, Citation2008, p. 45).

The messaging campaign was reasonably successful with the first post-Korean War generation of Koreans in Japan for several reasons. The harsh sociopolitical environment for Koreans in Japan was a push factor (Mithcell, Citation1967, p. 144; Ryang, Citation1997, p. 113; Morris-Suzuki, Citation2005, p. 372).Footnote6 South Korea at the time was not an appealing alternative because it was poor and ruled by a series of autocratic governments. Furthermore, Mindan did not receive significant South Korean support until late in the Cold War and as a result did not effectively engage Koreans in Japan on behalf of Seoul (Mithcell, Citation1967, p. 125; Lie, Citation2008, pp. 39–40). In the DPRK, Kim Il Sung, through formal speeches, committed to aiding the repatriation of Koreans from Japan. On September 8, 1958, he promised extensive support to facilitate their resettlement in their homeland. Simultaneously, on September 15, 1958, Nam Il, the Foreign Minister, issued diplomatic statements to engage the Korean diaspora in Japan. Aligned with Pyongyang’s directives, Chongryon significantly contributed to the repatriation movement by promoting North Korea as a ‘paradise on earth’, a tactic aimed at attracting Zainichi Koreans in Japan (Ryang, Citation2023, p. 14). Finally, there was a pull factor as North Korea enjoyed apparent economic success early in its existence (Gray & Lee, Citation2021, pp. 81–83).

Paradoxically, the repatriation campaign may have ultimately been the first in a long series of setbacks for Chongryon to engage with Koreans in Japan. At the Cheongjin Port, upon arrival in North Korea, the repatriates underwent a classification process, spanning several days to months, before being allocated to various locations throughout North Korea (Bell, Citation2018, p. 10). The North Korean authorities looked upon the new arrivals with suspicion due to the possibility that they had divided loyalties (Bell, Citation2022, pp. 90–95).Footnote7 Some returnees and their families were eventually detained in North Korean labour camps amidst political purges (Morris-Suzuki, Citation2007, p. 239). Through coded messages those who had settled in North Korea could communicate with relatives who remained in Japan and convey that life was more difficult and perilous than the Chongryon propaganda let on (Bell, Citation2019).Footnote8 Especially once family visitors were allowed from Japan in the 1980s “many Chongryon Koreans came to the realization that North Korea was a land of material shortage and political repression” (Ryang, Citation2016, p. 8).Footnote9 The demand for migrating to the DPRK rapidly evaporated. Eventually, small numbers began going the other direction, escaping North Korea to return to Japan (Bell, Citation2022), with some seeking accountability from the North Korean state for their travails (Tanaka, Citation2021).

Partly as a result, the peak of Chongryon support was from the late 1950s until the mid-1960s and it declined thereafter, with the 1990s being a time of “steady attrition in Chyongryun [sic] membership” (Ryang, Citation2016, p. 9). In the 1960s there were approximately 40,000 pupils in Chongryon schools annually, but that number dropped to about 15,000 in 2008 and is under 10,000 today (see Shipper, Citation2010, pp. 61–64). General membership has also shrunk. Estimates vary but likely stand at under 30,000 today.Footnote10

A key tipping point for Chongryon came on September 17, 2002. On that day North Korean leader Kim Jong Il admitted to Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi that North Korea had abducted 13 Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s (Hagström & Hanssen, Citation2015, pp. 72–74; for a history of the abduction project, see Boynton, Citation2016). The episode, along with North Korea’s nuclear programme, turned Japanese public opinion about North Korea even more negative than it already was (Hagström & Hanssen, Citation2015, p. 7; Chapman, Citation2004).

The kidnapping issue put Chongryon in a difficult position. It contradicted the group’s arguments before 2002 that claims by Japanese groups that North Korea had kidnapped Japanese citizens were just anti-DPRK propaganda (Dukalskis, Citation2021, p. 172). Some members themselves were surprised because they had assumed that stories of North Korean boats navigating to Japan’s coastline and grabbing people to bring back to North Korea were quite literally unbelievable.Footnote11 Some members resigned in disgust (Lie, Citation2008, p. 69). Kim Jong Il’s admission meant that Chongryon had to change its response to the issue from denial to one that accused the Japanese government of politicizing the issue or using it disingenuously (Dukalskis, Citation2021, p. 172). The group also became embroiled in Japan’s sanctions on North Korea as a result of the latter’s nuclear and missile tests, which made it more difficult to sustain financial solvency (Hastings, Citation2016, pp. 65–66). After the abduction admission and North Korea’s weapons testing, the Japanese authorities took a harder line on Chongryon, with prefectures ceasing to subsidize Chongryon schools, for instance. The Tokyo municipal government under Shintaro Ishihara (1999–2012) publicized the abduction issue and adopted an aggressively nationalistic tone. It also sought to restrict Chongryon’s activities by, for example, revoking the tax exempt status on its fixed assets (Park, Citation2011).

Chongryon has, in short, been hamstrung by North Korea’s own policies. North Korea’s deep unpopularity in Japan makes it increasingly difficult for the organization to retain its members, much less engage in outreach. It has attempted some reforms during its existence to adapt changing circumstances, such as revising its educational curricula so that Chongryon schools produce students able to succeed on entry exams for Japanese universities (Ryang, Citation1997, pp. 51–65). However, the organization was not able to react effectively to Japan’s changing relationship with South Korea, trends toward Koreans in Japan gaining Japanese or South Korean citizenship, the ineffective leadership of the Chongryon’s long-time head Han Doek Su, and the DPRK’s objectionable behaviour in the eyes of most Japanese (Ryang, Citation2016, pp. 9–12; Lie, Citation2008, pp. 67–72). Chongryon “lacked the proclivity, let alone the capacity, to respond to these changes, causing the organization to steadily lose legitimacy” among Koreans in Japan (Ryang, Citation2016, p. 12). Yet, it still attempts to appeal to second, third, fourth, and fifth (and beyond) generation Koreans in Japan via outlets like Choson Sinbo, the subject of this article’s next section.

The quest for relevance: text analysis of Choson Sinbo content

Text analysis of Choson Sinbo reveals Chongryon’s messaging over time, which we use to attempt to understand how the organization popularizes and mobilizes North Korean identity to Koreans in Japan, especially Chosen-seki (Korean domicile). By capturing, categorizing, and analyzing the messages that Chongryon disseminates over a long period of time, we can make inferences about how the organization has managed North Korean diaspora identity over multiple generations and the key reasons behind why Chongryon could not continue to appeal to the future diaspora generation of Koreans in Japan effectively.

Method

For the text analysis of Choson Sinbo messaging, we gathered articles from the Choson Sinbo website. Choson Sinbo provides a subscription service with a full PDF archive. Paid subscriptions may provide easily accessible data for analysis, but we followed an alternative approach because subscribing would necessitate a financial payment to Chongryon institutions connected to North Korea.Footnote12 Focusing on the full access and the previews of articles provided on the website, 2,054 Korean articles (analyzed in original language) and 1,498 Japanese articles (machine translated into English) were collected.Footnote13 Japanese articles have been uploaded since 1997, and Korean articles have been uploaded in earnest since 2010. We therefore have a total sample of over 3,500 articles over a 25-year period.

The Choson Sinbo website has sections of articles on various topics. This article constructs a text corpus using these self-presented categories, including (1) community news, (2) ethnic education, and (3) homeland visits, to examine how Chongryon has attempted to transfer DPRK identity to future generations. Each community and ethnic education section has sub-categories that provide ‘information’ centered articles and articles about the campaign side of Chongryon for more rights and welfare for Koreans in Japan.

describes the contents in more detail. ‘Community information’ discusses the activities of the Chongryon branches. These meetings include sports, hobbies, charity groups, and coming-of-age ceremonies. It also promotes activities and meetings of various special purpose gatherings, such as the Korean (and Youth) Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Japan and other meetings. The ‘community rights and welfare’ section introduces and promotes various welfare activities for the elderly associated with Chongryon branches. In addition, perceived discrimination against Chongryon schools and signature campaigns for free education are introduced together, overlapping some with the ‘ethnic education rights’ section.

Table 1. Text corpus description of Choson Sinbo website sections.

There are two sections devoted to ethnic education, separated into ‘information’ and ‘rights’ sections.Footnote14 In terms of ‘ethnic education information’, articles introduce various activities of Chongryon-affiliated educational organizations. The main characteristic of the contents of this section is the linkage between higher education institutions and elementary and secondary education institutions; for instance, university students and Youth League members transfer volunteer work and educational support activities to middle schools. The ‘ethnic education rights’ section discusses discriminatory measures against Chongryon educational institutions and promotes legal measures to support the organization’s schools. It mainly deals with legal measures to oppose the exclusion of Choson schools from the free high school education system provided by the Ministry of Education in Japan. Lastly, the articles in the ‘visiting homeland’ section retrospectively deal with memoirs of visiting Pyongyang. Mainly, Choson schools send students or recent graduates on education trips to North Korea for sports and cultural exchange programmes.

The text analysis goes deeper to examine the Choson Sinbo text corpus. We use qualitative text analysis with the NVivo software package.Footnote15 General trends of the sectional themes in Choson Sinbo are examined by word frequency, including actors, organizations, and geographical spread. Based on this analysis of the text corpus, we can infer how Chongryon tried to appeal to the inter-generational North Korean diaspora identity in Japanese society. Going deeper, we use the text analysis results to map out an idealized life sequence – from Chongryon’s perspective – for Koreans in Japan.

Results & Discussion

This section presents results of the analysis in three steps. First, it discusses the central rhetorical messages of the organization. Second, it maps out the organizational structure and membership of Chongryon. Third and finally, it uses these results to describe the ideal socialization and environment for those in the organization’s orbit. By doing so, the analysis provides implications for the promotion strategy and limitations of the state-sponsored diaspora organization to appeal to the next generations of the diaspora in the host country.

What are the central messages of choson sinbo?

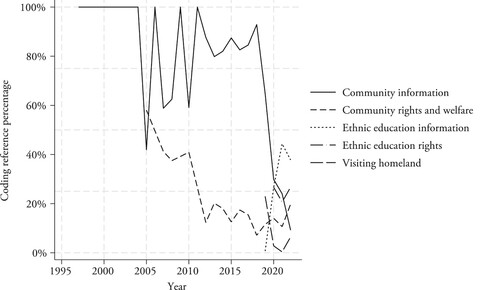

Prior to 2012, most available Choson Sinbo articles were categorized as ‘community information’ (tonpotonne in Korean – compatriots’ community). After 2012, the total uploaded articles on the website significantly increased over 10-fold.Footnote16 In 2019, the types of articles of Choson Sinbo began to diversify. Rights struggles related to Choson schools began to appear in the ethnic education session. In other words, since 2019, various types of articles have appeared more frequently. One noteworthy point is that the proportion of community information has decreased since 2019. Considering that the ratio has decreased, it can be inferred that the emphasis of Chongryon has recently taken a diversification strategy beyond the form of simply informing about branch activities and promotion news (see below). It works to promote itself as the protector of Korean rights in Japan. This is not a new strategy, but it appears to be resurgent.

Figure 1. Frequency of article types.

Note: Author made the figure based on merged articles in both Korean and Japanese.

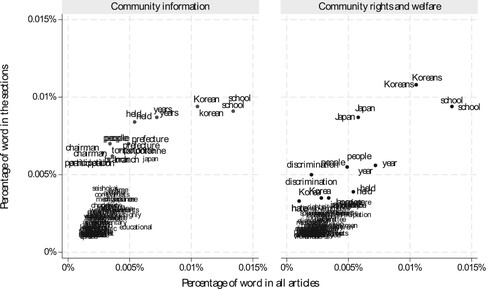

Text analysis at the semantic level and word units provide further insights. We gathered the 100 most frequently used words in the Choson Sinbo sections and allocated action and agency themes (see Franzosi, Citation1989). These comprise (1) community information, (2) community rights and welfare, (3) ethnic education information, and (4) ethnic education rights. The main contents of Choson Sinbo are categorized in these four sections, so considering the substance of these sections provides inferential advantages for how an authoritarian regime affiliated organization – Chongryon – packages and disseminates its message to the Korean diaspora in Japan.

The community information and rights and welfare sections are depicted in . Both used the terms ‘Korean’ and ‘school’ frequently in conveying community information and advocating for rights and welfare. For example, as community information, various school-related activities and gatherings are introduced, and as a section on rights and welfare, the articles represent various campaigns and signature movements against discrimination in schools and in everyday life. The words ‘tonpotonne’ (compatriots’ community), ‘branch’, and ‘prefecture’ had a higher frequency in the community information as organizational terms. Numerous articles in this session inform readers about how many people participated in and what activities they participated in for Chongryon branches, sub-branches, and various organizational meetings.Footnote17 Whereas, ‘school’ and ‘discrimination’ were frequently mentioned in the rights and welfare session, and ‘hate’, ‘education’, ‘Japanese’ and ‘government’ were also frequently mentioned. This indicates that articles addressed the Japanese government’s alleged discriminatory treatment of Choson school education.

Figure 2. Top ten words in community sections.

Note: Author utilized the English text corpus of Choson Sinbo.

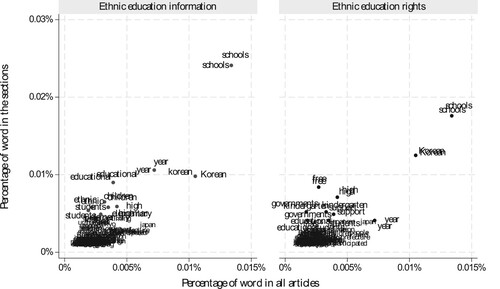

While the community section of Choson Sinbo has been uploaded since the 2000s, the sections on ‘ethnic education information’ and ‘ethnic education rights’ have been actively updated in both Korean and Japanese articles only since 2020, with the proportion of such articles increasing. Schools and education have become a focus. This is perhaps because education is the most solid organizational pillar of Chongryon, but also because school is a venue for socialization of future generations of potential Chongryon supporters.Footnote18

Articles in the ethnic education sections frequently include numerous references to educational institutions at various levels, ranging from kindergarten to secondary, high school, and university education (see ). In terms of explaining school information and events, the ethnic education information section is similar to the community information section. It describes the entrance ceremony, various school events and activities, and examples of how Chongryon organizations provided and assisted ethnic education. The section on ethnic education rights discusses more direct issues on their rights in the Japanese society. A primary focus, for instance, is on legal proceedings condemning Choson schools’ exclusion from the free high school education in the Japanese education system. Accordingly, the terms ‘free’, ‘court’, ‘trials’, ‘Japanese’, ‘government’, and ‘discrimination’ appear frequently in the section of ethnic education rights.

Figure 3. Top ten words in ethnic education sections.

Note: Author utilized the English text corpus of Choson Sinbo.

In sum, the thematic analysis of Chongryon’s communication shows that the organization focuses on education, and in particular protecting educational rights. The organization presents itself as a protector of those who wish to attend Chongryon schools and portrays the Japanese government as an obstacle to educational autonomy for Koreans.Footnote19 Relative to other topics, particularly community information, educational topics appear to be on the increase. Indeed, educational activities, supported or sponsored by the home country, are an essential instrument for implementing intergenerational appeals and targeted diaspora policy toward post-migrant generations (Mahieu, Citation2015). Textual analysis of word frequency demonstrates that Chongryon attempts symbolic nation-building through Choson education, builds national identity, and simultaneously justifies the North Korean regime’s rule.

What are the central organizations in choson sinbo’s messaging?

According to Chongryon’s official website, there are 47 regional headquarters (Jibu) in each province and prefecture in Japan, and each regional headquarters has its own branch (Jihoe), and sub-branch (Bunhoe) (Chongryon, Citation2022a). The regional headquarters plan, organize, and guide organizations, businesses, and schools under their authority in accordance with the decisions and policies of the Chongryon Central Committee. The branch is the next level down, serving as a unit to organize projects, including those that defend the lives and rights of its local compatriots and adhere to ethnicity, in cooperation with its affiliated societies, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Women’s Union, and schools.

The sub-branch is introduced as the base organization of Chongryon (Chongryon, Citation2022a). According to Chongryon’s objectives, the sub-branch functions as a practical unit that deals with difficulties raised among compatriots in a timely manner, including helping with personal issues. The sub-branch provides administrative services and directly helps connect members through a coalition of compatriots in the Chongryon community, forming an interlocking system of sub-branches. Therefore, evaluating the sub-branches’ activities shown in the Choson Sinbo articles indicates which specific activities were emphasized by Chongryon and what extent Chongryon has appealed to North Korean identity.

For this evaluation, by first searching for ‘branch’ as a keyword through the text corpus of Choson Sinbo articles, we can trace which branches are frequently referred to relative to others. This gives us a sense of the geographical spread of Chongryon’s branch activities throughout the country. may differ from the actual organizational map of the Chongryon branches officially shown as the latter does not take into account how active the branch is.Footnote20 Chongryon branches are formed around large cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, and in the case of large branches, several sub-branches are divided, and in some cases, these sub-branches are abolished and re-established depending on the capabilities of Chongryon activities.Footnote21 shows clearly that the Osaka area features disproportionately, which makes sense as the city is home to many Koreans.

Figure 4. Activity frequency of Chongryon branches.

Note: The authors have counted the frequency reference percentage inductively based on the branch name in the text corpus of Choson Sinbo.

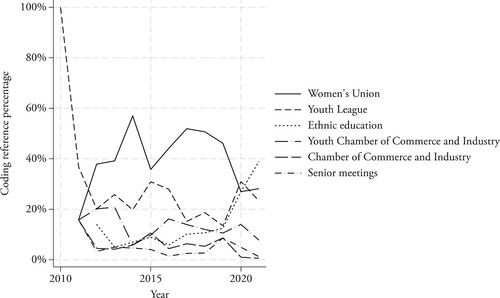

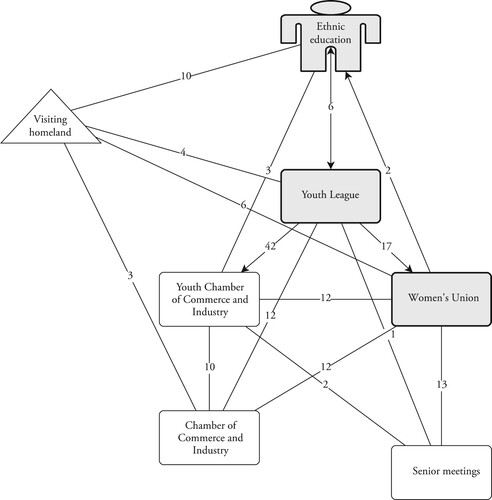

The frequency of articles featuring sub-organizations can provide clues about their strategic importance. There are several organizations under Chongryon, and through the frequency of activities of organizations actively appearing in Choson Sinbo news, we can find out what organizational methods Chongryon uses to mobilize subsequent generations. shows that the names of major organizations that appeared from 2010 to 2021 were the Women’s Union, Youth League, ethnic education, Youth Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and Senior meetings. It is worth noting that the frequency of exposure to articles by Women’s Union (membership of which includes females 30 years old or older) is overwhelmingly highFootnote22, and the influence of Youth League, which includes male and female youth, has increased since 2019.Footnote23

The influence of educational institutions is significant for the political and socialization process. This is the reason why Choson schools, which are systematically formed from kindergarten to elementary, middle, and university education, occupy a high position in the focus of articles. Kim Il Sung offered substantial educational assistance and scholarships to Chongryon for children of Korean residents in Japan since the inception of Choson University in April 1956, and between April 1957 and April 2005, North Korea paid an educational grant to Chongryon 151 times for a total of 45.53 billion Japanese Yen (Yim & Heo, Citation2013, p. 287).

Expiring reproduction of Chongryon’s inter-generational narrative

Based on the articles of the Choson Sinbo, we can reconstruct the ideal political and socialization process envisioned by Chongryon; that is, the narrative that is important in forming and transferring its identity as a North Korean diaspora that lasts for decades. The text corpus of Choson Sinbo provides evidence for a map analysis, comparing texts in terms of both concepts and the relationship between them (Carley, Citation1993, p. 91). This approach to text-mining practice preserves much of its inductive nature and insights (Goldenstein & Poschmann, Citation2019, p. 114).

In the Choson Sinbo articles, agents were represented and linked with other groups by demonstrating specific actions. Mapping the relationships among the groups, the agencies’ relationships could be defined as ‘associative’ or ‘influence’. For instance, various charity events and cultural campaigns indicate the associative relationship between the Youth League and the Youth Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Choson Sinbo, Citation2013). These specific collaboration events and participating in volunteer activities for them are defined as an ‘associative’ relationship.

An influence relationship means that one group strengthens the other group in both material (e.g. providing membership and donation) and non-material (e.g. fostering ideological affiliation and commemorating legacies of Chongryon activities) conditions. This relationship is coded qualitatively as the direction of influence. The number represents the frequency with which two institutions (or activities) are mentioned together in Choson Sinbo articles. This coding approach allows for a quantification and identification of the relationship between entities, thereby deepening our insight into their associative or influence connections as analyzed. By reducing ex-ante interpretations and utilizing the text corpus of an authoritarian regime-affiliated group’s newspaper, this map-analytic technique helps trace how Chongryon’s narratives are demonstrated in Choson Sinbo and how the Chongryon’s narratives formulated North Korean diaspora’s way of life in Japan.

summarizes the outline of the relationships among Chongryon’s sub-organizations. It indicates idealized an social life and Chongryon’s diaspora engagement strategy. Chongryon educational institutions conduct ethnic education from kindergarten to adulthood. During this process, students may have an opportunity to visit Pyongyang. This process is accompanied by a practical experience of the political and socialization process through mass organizations. They, for instance, join the Youth League if they are over high school age, which serves as an organization in charge of major activities of the Chongryon branches, including support for ethnic education and alumni activities, community service, and events to promote local economy and culture.

Figure 6. Chongryon’s Idealized Social Life.

Note: Lines indicate associative relationships, and arrow lines mean an influence relationship. Gray boxes indicate Chongryon’s official organizations and white boxes mean specialized groups. The number presented indicates the frequency of concurrent mentions of the two institutions (or activities) within articles from the Choson Sinbo. For detailed coding information, see Appendix.

Memoirs in the Choson Sinbo depict the inter-generational narrative arc. These mainly take the form of recognition of one’s parental generation who devoted themselves to Chongryon branch activities, and testimony in the form of a conviction that young generations will devote themselves to this work after graduating from Korea (Choson) University.Footnote24

I lost my father unexpectedly in my third year of university. My father returned to Sapporo for the first time in a long time at the end of the year. […] My father, I assumed, was probably going through a lot of trouble at the expense of his own body for his compatriots in the newly appointed branch. […] I was concerned about what to do about the Chongryon organization. I wanted to attend Korea (Choson) University because I wanted to be a Chongryon worker like my father, who is well- liked by my countrymen, but I considered dropping out the plan in frustration. [After hearing compliments from fellow compatriots at the funeral] I was certain at the time. My father’s Chongryon business, which he gave his all to, was never wrong. […] I will always cherish consideration of the Supreme Leader, Kim Jong Un for Chongryon’s organization, and I will enjoy learning and listening to the organization life. In the future, I will carry on my father’s will to become branch leader, and I will also study harder to become a true Chongryon worker capable of being responsible for the Chongryon in Hokkaido [author translated] (Choson Sinbo, Citation2012b).

Another Chongryon mass organization is the Women’s Union, which is composed of women in their 30s or older.Footnote25 In particular, the Women’s Union supports ethnic education through various mother’s association activities by registering their children at educational institutions under Chongryon, various charity and social activities, and volunteer activities of Chongryon. These activities themselves are meant not only to promote solidarity of the organization but are also important ‘evidence’ of a continued pathway within Chongryon structures after education. They bind members closer to the organization and channel their activities.

The North Korean diaspora identity suggested by Chongryon can also be formed on an economic basis. To this end, Chongryon has traditionally organized the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Japan to emphasize the economic cooperation and unity of the branches, and has organized Youth Chamber of Commerce and Industry to foster the next generation in the branch building project.

Finally, the nature and significance of Senior meetings are also noteworthy. Senior meetings have various names for each branch, but they are connected to social gatherings for the elderly. One important part of Chongryon’s strategy towards the transmission of the North Korean diaspora identity is reproducing respect for the life of seniors. As mentioned earlier, to transfer the narrative of Chongryon to next diaspora generations, it is necessary that the life of the elderly generation who followed Chongryon’s narrative faithfully is lauded. For this reason, articles on the slogan of forming the branch as a ‘great family’ and joint events led by the Women’s Union and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry can be seen frequently.Footnote26

On December 7th, the Motosan Higashide sub-branch of the Kobe branch of Chongryon and Women’s Union held a year-end party at a branch office. 47 compatriots under the jurisdiction of men and women, ranging from pre-school to 80-year-old elderly compatriots, participated as a result of actively carrying out promotion at the branch. A family that had a new housewarming party this year and compatriots who participated in the sub-branch meeting for the first time were introduced at the meeting, which began with the toast of Central Committee Chairman. Participants praised the food prepared by the Women’s Union as delicious. Following that, a singing contest was held for students and participants, and laughter and applause erupted in the hall, which was always exciting [author translated] (Choson Sinbo Citation2019).

What is clear from this analysis is that Chongryon has the scaffolding of an organizational structure to engage with a member from early childhood until senior citizenship. In this sense, the structure parallels the system of mass organizations, indoctrination, and everyday authoritarianism inside North Korea itself (Lee & Kim, Citation1970; Dukalskis, Citation2017; Dukalskis & Lee, Citation2020). However, one crucial difference is that within North Korea membership in such organizations is generally compulsory. North Koreans have few other options but to be a part of the system as a member of one of the party-controlled organizations (Lankov et al., Citation2012, pp. 195–201). Derived from Soviet principles of societal control, mass organizations play socializing and surveillance functions that help sustain the DPRK’s authoritarian system (Cumings Citation2019). In the case of Chongryon, however, it is much more difficult to compel Koreans in Japan to be bound to the organization’s structures. Koreans in Japan simply have more exit options than Koreans in North Korea from the organizational life of the DPRK.Footnote27 This helps explain Chongryon’s inability to remain appealing to subsequent generations of Koreans.

Conclusion

This article has sought to understand a unique case of inter-generational diaspora engagement by an authoritarian state. Because virtually none of the Koreans living in Japan ever originated from North Korea, the DPRK-supported Chongryon attempts to manufacture attachment to a totalitarian dictatorship that few have ever been to. It met with some success in the 1950s and 1960s as North Korea competed with South Korea for the mantle of legitimacy and to showcase material success on the Korean peninsula. However, as people learned about repression and poverty inside North Korea and as South Korea democratized and developed, North Korea’s appeal faded.

The result is that Chongryon’s inter-generational engagement with Koreans in Japan appears to rely on its education infrastructure, status as a protector of Koreans in Japan, and a life-cycle process akin to North Korea’s mass organization structure. Using text analysis from Choson Sinbo, the organization’s main news website, we were able to map the themes, sub-organizational structures, and ideal life cycle of those who engage with the organization. However, the key difference with Chongryon and analogous organizations in North Korea is that the latter can rely on coercion and state power. Chongryon cannot, which means that Koreans in Japan have exit options that Koreans in North Korea do not. The result has been a deterioration of Chongryon’s organizational strength and appeal.Footnote28

Looking forward, it will be difficult for Chongryon to reinvigorate its intergenerational engagement unless something drastic happens. One possibility to consider is that if North Korea significantly liberalizes, sanctions are eased, and its economy open to meaningful foreign investment, then Chongryon could play a role as a broker between the Korean community in Japan and the new-look DPRK. Chongryon has long played such a role but is limited by the closed and autocratic nature of North Korea. Some argue that North Korea may follow a Chinese or Vietnamese-style strategy of economic reform without political liberalization (Greitens & Silberstein, Citation2022). Should this process ultimately occur the image and opportunities associated with North Korea could change and revitalize Chongryon’s engagement, but this remains a distant prospect.

Reaching for the Past Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (41.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Junhyoung Lee

Junhyoung Lee is lecturer in the School of International Relations at University of Ulsan in Ulsan, Korea. His research and teaching focus on authoritarianism, Korean politics, and comparative communism. His work on these themes has been published in Nationalities Papers and Asian Studies Review.

Alexander Dukalskis

Alexander Dukalskis is associate professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin in Dublin, Ireland. His research and teaching focus on authoritarianism, human rights, and Asian politics. His work on these themes has been published in several leading journals, including Journal of Peace Research, Democratization, China Quarterly, and Government & Opposition. He is the author of two books, the most recent of which is Making the World Safe for Dictatorship, published by Oxford University Press in 2021.

Notes

1 Korean names are written with the family name preceding the given name, separated by a space.

2 The Choson Sinbo was re-established as a daily newspaper in 1961 after the Minjung Ilbo (the People’s Daily) (1945) passed through the Haebang Sinmun (the Liberation Newspaper) (1946) and Choson Minbo (Choson People’s Daily) (1957). The Choson Sinbo reported a circulation of 50,000 in the 2008 edition of Zasshi Shimbun Sokatarogu (ZSS), a figure consistent with its 2004 report (Open Source Center, Citation2009, pp. 25–26).

3 North Korea is consistently classified as an authoritarian regime in major political datasets. According to Polity IV, it often receives the lowest possible score (-10), indicative of extreme autocracy (Marshall et al., Citation2020). Similarly, V-Dem data categorizes North Korea as authoritarian, with minimal scores across various democratic dimensions, underscoring its lack of political pluralism and civil liberties (Coppedge et al., Citation2023).

4 Since Mindan’s inception, the organization has evolved to advocate for the rights of South Koreans in Japan in opposition to Chongryon’s actions. This article analyzed Chongryon as the substance of North Korea’s diaspora policy abroad. For the details about the legal classification process of Korean residing in Japan as ‘Chosen-seki’(Korean domicile) or ‘Kankoku-seki’(South Korean nationality) after Japan recognized South Korea as the sole legitimate government on the Korean Peninsula, see Cho (Citation2020).

5 According to Chongryon’s general principles (Chongryon, Citation2022b), “[w]e are devoted to preserving the rights of our fellow countrymen and completing the Juche accomplishment by uniting all Koreans in Japan under the banner of patriotism in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”.

6 In examining the challenging experiences of first-generation Zainichi Koreans in Japan, see Kang and Fletcher (Citation2006).

7 North Korea’s societal hierarchy, known as ‘Songbun’, categorizes citizens into three principal classes: core wavering, and hostile. Zainich Korean typically fall within the ‘wavering’ category, encountering constraints in employment and mobility (Ryang, Citation2023, p. 16). Notably, Zainich Koreans who relocate to Pyongyang, often through Chongryon involvement and political lobbying, confront discrimination, partly attributed to cultural disparities and their perceived status as ‘Japanese imperial sympathizers’ in the host society (Bell, Citation2018, pp. 11–13).

8 Also interview, former Chongryon member, Tokyo, August 10, 2019.

9 Accessing the experiences of repatriated Zainichi Koreans in North Korea presents complexities, with varied narratives surfacing in interviews (Ryang, Citation2023, p. 16; Rhee, Citation2022, p. 487). A consistent observation, however, is the disparity between Chongryon’s optimistic propaganda and the realities of life in North Korea.

10 Separate interviews, Tokyo, August 7, 2019, with civil society organization leader and expert on Chongryon, respectively.

11 Interview, former Chongryon member, Tokyo, August 10, 2019; interview, civil society organization leader, Tokyo, August 7, 2019.

12 On November 4, 2020, it was reported that most of its content is behind a paywall, which complicates matters because it may run afoul of sanctions against North Korea. See O'Carroll (Citation2020).

13 We found that there was no discernible difference in text analysis between the Japanese articles and English articles converted to English via Google Translation. To enhance accuracy in our nuanced and qualitative content analysis, we employed Korean articles, leveraging the native Korean language proficiency of one of our authors. Considering these articles primarily consist of concise event reports, we assessed that auto-translated material from Japanese to English is sufficiently reliable for our frequency analysis.

14 According to the list of Choson schools registered on the official website of Chongryon, 64 education facilities appear, and these schools provide comprehensive education courses. For example, middle-high schools are often combined, and kindergartens are often together in elementary school facilities. Regarding the stages of education, 33 kindergartens, 18 elementary education, 29 secondary education, ten higher education, and one university are registered. See Chongryon (Citation2022c).

15 NVivo (Mac) (Release 1.7.1)

16 Indeed, since the late 1990s, Choson Sinbo content changed in strengthening the features of current affairs – general interest magazines. See Jang, I. S. (Citation2003).

17 Women’s Union (Neyomaeng), Youth League (Jocheong), (Youth) Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Cheongsanghoe, Sanggonghoe), and Senior meetings (Jangsuhoe) are all example of notable organizations.

18 Due to the socialisation feature of ethnic education, Chongryon’s general principles (Chongryon, Citation2022b) emphasized “[w]e strengthen and develop democratic national education and educate diverse group of Korean-Japanese youngsters to be capable national geniuses with ethnic and intellectual virtue, as well as sincere patriots [emphasis added]”.

19 Choson University students protested that the Japanese government was being treated discriminately for exclusion from the student subsidy system during the COVID-19 pandemic (Choson Sinbo, 2021).

20 The size and status of a branch are not reported on the official website of Chongryon. Therefore, tracing based on the frequency of the references provides a methodological approximation for mapping Chongryon’s branch activity.

21 For instance, it took approximately 16 years to rebuild the Juo (Central) sub-branch of Chongryon Fukui Prefecture’s headquarters. According to Choson Sinbo, approximately 5,000 Koreans from six branches were active here during the movement’s heyday. See Choson Sinbo (Citation2012a).

22 This analysis correlates with Markus Bell’s study highlighting the significance of women’s kin work in repatriated Zainichi Korean families settings. See Bell (Citation2018).

23 In particular, Youth League has actively engaged with multiple social network platforms, including Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram, since 2018.

24 Korea (Choson) University is Chongryon’s tertiary ethnic education institution, funded by the government of North Korea; thus, it is not authorized as a ‘university’ based on the Japanese School Education Law, so it is treated as a ‘miscellaneous school’.

25 Chongryon recommended ethnic marriage within the Chongryon membership and has even established an ethnic marriage counselling center. However, since the 1980s, the marriage rate with Japanese has increased every year, reaching more than 80 per cent in the 2000s. In comparison, the Chongryon membership marriage rate has fallen below 20 per cent, and the absolute number has decreased significantly. See Choson Sinbo (Citation2014); Sakanaka, H. (Citation2000); Chapman (Citation2004).

26 “Making sub-branch (Bunhoe) as a one great family” became the slogan of the Chongryon’s movement. See Choson Sinbo (Citation2018)

27 After the 2000s, the Chongryon’s younger generation changed their identity based on orientation toward ‘return’ to homeland and ‘stay’ in Japan. They have orientation toward both South Korea (representing their birth land) and North Korea (representing their ideological concurrence). So, Chongryon demonstrates a strong tendency to stay in Japan and opt for individualism. See Jang (Citation2003); Tai (Citation2004). For the new identity developing of Koreans in Japan as the ‘Third Way’, see Chapman (Citation2004).

28 The increasing naturalization rate is the outcome of Chongryon’s organizational inability. In the 1990s, the number of Zaninichi Koreans registering for Japanese citizenship – naturalization – increased, reaching a peak in 2003 before declining thereafter. See Laurent and Robillard-Martel (Citation2022).

References

- Bell, M. (2018). Patriotic revolutionaries and imperial sympathizers: Identity and selfhood of Korean-Japanese migrants from Japan to North Korea. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 27, 1–25.

- Bell, M. (2019) Reimagining the homeland: Zainichi Koreans’ transnational longing for North Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20(1), 22–41.

- Bell, M. (2022). Outsiders: Memories of migration to and from North Korea. Berghahn.

- Boynton, R. S. (2016). The invitation-only zone: The true story of North Korea’s abduction project. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Brubaker, R. (2005) The ‘diaspora’ diaspora. Ethnic and Radical Studies, 28(1), 1–19.

- Carley, K. (1993) Coding choices for textual analysis: A comparison of content analysis and map analysis, Sociological Methodology, 23, 75–126.

- Chapman, D. (2004). The third way and beyond: Zainichi Korean identity and the politics of belonging. Japanese Studies, 24(1), 29–44.

- Cho, K. H. (2020) Politics of identification of Zainichi Koreans under the divided system. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 21(3), 452–464.

- Chongryon. (2022a). Introduction to Chongryon - organizational system and organization of Chongryon. Chongryon. http://www.chongryon.com/k/cr/index4.html

- Chongryon. (2022b). Introduction to Chongryon -Chongryon’s character and principles of activities. Chongryon. http://www.chongryon.com/k/cr/index3.html

- Chongryon. (2022c). List of agencies at all levels - schools at all levels. Chongryon. http://www.chongryon.com/k/cr/link_3.html

- Choson Sinbo. (2012a). <Challengers, toward a new heyday 19> After 16 years of reconstruction, people in their 40s and 50s will do their best / Chongryon Fukui Juo Sub-branch. Chongryon. https://www.chosonsinbo.com/2021/10/25-49/

- Choson Sinbo. (2012b). [Memoirs] following my father's wishes, I am a member of the Chongryon group responsible for the society of compatriots. Chongryon. https://www.chosonsinbo.com/2012/10/sinbo-k_121102-7/

- Choson Sinbo. (2013) A wide generation of compatriots celebrated the 65th anniversary of the founding of the republic in gunma prefecture. Tokyo: Chongryon. https://chosonsinbo.com/2013/09/군마에서-공화국창건-65돇경축-동포대야유회%EF%BC%8F폭넓/

- Choson Sinbo. (2014). The 20th anniversary of the establishment of the Korean marriage counseling center. Chongryon. https://chosonsinbo.com/2014/04/0402yj-4/

- Choson Sinbo. (2018). A jount new year’s meeting of the hyotanyama sub-branch of Higashi Osaka branch Chongryon and women’s union / making sub-branch like as a one great family. Chongryon. https://www.chosonsinbo.com/2018/01/il-1590/

- Choson Sinbo. (2019). The year-end party of motosan higashide sub-branch of the Kobe branch and women’s union / Chongryon, where local compatriots live like family members. Tokyo: Chongryon. Available at: https://www.chosonsinbo.com/2019/12/hj191211-3/ (Accessed: March 24, 2022).

- Choson Sinbo. (2019). <Issue of emergency subsidy for students> Japanese government, ignoring U.N. Warnings / The voices of protests from the choson university students. Chongryon. https://www.chosonsinbo.com/2021/09/09-45/

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., et al. (2023). V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. 10.23696vdemds23

- Cumings, B. (2019). The corporate state in North Korea. In H. Koo (Ed.), State and society in contemporary Korea (pp. 197–230). Cornell University Press.

- Dukalskis, A. (2017). The authoritarian public sphere: Legitimation and autocratic power in North Korea, Burma, and China. Routledge.

- Dukalskis, A. (2021). Making the world safe for dictatorship. Oxford University Press.

- Dukalskis, A., & Lee, J. (2020). Everyday nationalism and authoritarian rule: A case study of North Korea. Nationalities Papers, 48(6), 1052–1068.

- Franzosi, R. (1989). From words to numbers: A generalized and linguistics-based coding procedure for collecting textual data. Sociological Methodology, 19, 263–298.

- Goldenstein, J., & Poschmann, P. (2019). Analyzing meaning in big data: Performing a map analysis using grammatical parsing and topic modeling. Sociological Methodology, 49, 83–131.

- Gray, K., & Lee, J.-W. (2021). North Korea and the geopolitics of development. Cambridge University Press.

- Greitens, S., & Silberstein, B. K. (2022). Toward market Leninism in North Korea: Assessing Kim Jong Un’s first decade. Asian Survey, 62(2), 211–239.

- Greitens, S. C. (2020). “The north Korean diaspora”. In A. Buzo (Ed.), Routledge handbook of contemporary North Korea (pp. 233–247). Routledge.

- Greitens, S. C. (2023). Politics of the north Korean diaspora. Cambridge Elements in Politics and Society in East Asia.

- Hagström, L., & Hanssen, U. (2015). The north Korean abduction issue: Emotions, securitisation and the reconstructino of Japanese identity from ‘aggressor’ to ‘victim’ and from ‘pacifist’ to ‘normal’. Pacific Review, 28(1), 71–93.

- Hastings, J. V. (2016). North Korea: A most enterprising country. Cornell University Press.

- Jang, I. S. (2003). The changing identity of north Koreans in Japan. Review of International and Area Studies, 12(4), 27–49.

- Kang, S., & Fletcher, R. (Trans.). (2006). Memories of a Zainichi Korean childhood. Japanese Studies, 26(3), 267–281.

- Lankov, A. N., Kwak, I.-o., & Cho, C.-B. (2012). The organizational life: Daily surveillance and daily. Resistance in North Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 12(2), 193–214.

- Laurent, C., & Robillard-Martel, X. (2022). Defying national homogeneity: Hidden acts of Zainichi Korean resistance in Japan. Critique of Anthropology, 42(1), 38–55.

- Lee, C.-S., & Kim, N.-S. (1970). Control and administrative mechanisms in the north Korean countryside. Journal of Asian Studies, 29(2), 309–326.

- Lie, J. (2008). Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): diasporic nationalism and postcolonial identity. University of California Press.

- Mahieu, R. (2015). Feeding the ties to “home”: diaspora policies for the next generations. International Migration, 53(2), 397–408.

- Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2020). Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1880-2019. Center for Systemic Peace. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html

- Mithcell, R. H. (1967). The Korean minority in Japan. University of California Press.

- Morris-Suzuki, T. (2005). A dream betrayed: Cold war politics and the repatriation of Koreans from Japan to North Korea. Asian Studies Review, 29(4), 357–381.

- Morris-Suzuki, T. (2006). Invisible immigrants: Undocumented migration and border controls in early postwar Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 32(1), 119–153.

- Morris-Suzuki, T. (2007). Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s cold war. Rowman & Littlefield.

- O'Carroll, C. (2020). Pro-North Korea newspaper in Japan monetizes website with paywall. Seoul: NK News. https://www.nknews.org/2020/11/pro-north-korea- newspaper-in-japan-monetizes-website-with-paywall/

- Open Source Center. (2009). Japan – Media environment open; state looms large. Washinton: Open Source Center. https://irp.fas.org/dni/osc/japan-media.pdf

- Orjuela, C., Wackenhut, A. F., & Hirt, N. (forthcoming). Authoritarian states and their next generation diasporas: An introduction. Globalizations.

- Park, J. J. (2011). Ethnic policy and measures for Korean residents in Japan of Tokyo: Formation and causality. The Korea Journal of Japanese Studies, 33, 363–393.

- Rhee, J. (2022). Cinematic testimony to the repatriation of Zainichi Koreans to North Korea in yang yonghi’s autobiographical films. Asian Studies Review, 46(3), 473–490.

- Ryang, S. (1997). North Koreans in Japan: Language, ideology, and identity. Westview Press.

- Ryang, S. (2016). The rise and fall of chongryun – from chosenjin to zainichi and beyond. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 14(15), 1–16.

- Ryang, S. (2023). Japan, North Korea, and the biopolitics of reptriation. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 21(6), 1–25.

- Sakanaka, H. (2000). Past, present, and future of Koreans in Japan (special feature: Koreans in Japan now). Gendai Koria, 401, 30–41.

- Shipper, A. W. (2010). Nationalisms of and against zainichi Koreans in Japan. Asian Politics & Policy, 2(1), 55–75.

- Tai, E. (2004). “Korean Japanese” A new identity option for resident Koreans in Japan. Critical Asian Studies, 36(3), 355–382.

- Tanaka, C. (2021). Defectors from North Korea Pray for Resettlement Victims, Associated Press 20 December 2021. https://apnews.com/article/japan- north-korea-eca9df70fc42f40ca105419797d115f7

- Yim, Y. E., & Heo, T. S. (2013). The study on the diasporic viewpoint of chongryeon and north Korean relationship in Japan. Journal of Northeast Asian Studies, 18(1), 279–304.