ABSTRACT

The use of digital educational platforms has increased in schools, especially during Covid-19, accelerating digital transformation and the expansion of data collection. However, the platformisation phenomenon in this context is still largely unexplored. The present study aims to identify the presence and uses of digital platforms in the educational context of Catalonia and significant changes post-Covid-19 through a validated questionnaire. Results from 491 primary school teachers show that almost 90% of the digital tools used are proprietary platforms belonging to the major technology companies. Many relationships between frequencies and types of tools have been identified as well as a significant evolution of their use in the wake of Covid-19. Some recommendations at different levels are drawn up.

Introduction

Children in today’s digital society live immersed in a complex and dynamic world with continuous exposure to the media and the generalised use of technology, including in the educational context. Digital technologies, in combination with pedagogical strategies, have become essential tools for transforming education systems, fostering high quality and inclusion (European Commission, Citation2020). During the Covid-19 pandemic, digital technologies played a significant role during schools’ closure and subsequent lockdowns, ensuring students’ access to education and enabling teachers to teach remotely.

Digital technologies had already been seen as a driving force for economic globalisation (Winter et al., Citation2021). Hence, they are a key factor influencing education, changing the roles of students and teachers, and becoming a challenge for schools. Some of the biggest global technology companies, known as Big Tech, the Big Five or GAMAM (Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple and Microsoft), have also expanded their educational services with tools, applications, projects and programmes from their foundations. Here they are called ‘global educational digital platforms’ due to their global reach and extended use (e.g. Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, etc.). According to Sefton-Green and Pangrazio (Citation2021), the concept of platform refers to a programmable, proprietary online site that can be accessed from different devices and is also related to contemporary forms of capitalism.

Educational technology can be understood as an integral part of the ‘global society’ entwined with connections into schools’ reality within the dialectic of the global and the local context (Selwyn, Citation2012). The presence of technology in schools is, therefore, a reflection of society where digital technologies have been adopted merely as solutions to any problem (Williamson et al., Citation2020). Against this backdrop, and in order to have an overview of the magnitude of the situation, this study aims to analyse what kind of global digital educational platforms are present in primary schools and how teachers and students use them, identifying a hypothetical Covid-19 impact on this use, in the specific case of the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia.

Theoretical background

Digital tools and schools under Covid-19 conditions

The Covid-19 pandemic took 1.5 billion students out of school and forced the implementation of social distancing protocols between March and April 2020. It resulted in a rapid shift to remote teaching and learning with the application of digital learning solutions (BID, Citation2021; Myers et al., Citation2022). The OECD described the pandemic as an opportunity for envisioning new models of education empowered by big data and artificial intelligence (Williamson et al., Citation2020). Others claimed that educational technologies were a remedy for taking advantage of the Covid-19 crisis and schools’ lockdown, a springboard for the commercial education technology industry (EdTech) and a chance to influence educational institutions, teachers and practices (Selwyn et al., Citation2020; Williamson et al., Citation2020).

Many students signed up to new platforms in order to be able to access their classes in exchange for their information (Williamson, Citation2021), raising important concerns about data management, privacy and surveillance, and making education one of the sectors most affected by datafication (Jarke & Breiter, Citation2019). For example, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to increased use of Google in schools as more than 170 million students and teachers around the world use Google’s educational tools (Sinha, Citation2021) with Google Classroom being the most popular educational application in Spain (Qustodio, Citation2020). According to Krutka et al. (Citation2021), Google disguises its business model and persuades the consumer to perceive it as a free public service, using student identity as a commodity (Lindh & Nolin, Citation2016) and becoming a sociotechnological artefact with implicit social values (Toscano, Citation2012).

In the broadest context, international organisations like the European Commission call for the digital competences of students and teachers, considering security as one of its areas, to be included in the objectives of education systems (DigComp for citizens and DigCompEdu). The European Commission’s Digital Education Action Plan (2021–27) sets education systems adapted with technology as an example to follow for an idyllic concept of the digital age with user-friendly tools and safe platforms that, among other things, respect privacy and ethics. However, public consultation by the European Union shows that online resources and learning content need to be more appropriate, interactive and easy to use (European Commission, Citation2020).

During the state of emergency due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the use of educational applications grew by 54%, placing Spain as the country where it increased the most compared to other countries such as the US and the UK (Qustodio, Citation2020). Just over half (53%) of children between the ages of 6 and 15 have attended classes or activities via the internet. The younger ones participated to a lesser extent than the older ones (Ontsi, Citation2022). Another study carried out by EduCaixa (Citation2020) with a sample of 1600 teachers in Spain reported that 94% of educators increased their professional use of technology during Covid-19. According to a study carried out by UNICEF (Citation2020), the communication in different educational centres of Spain during lockdown was carried out through videoconferences via platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom or Google Meet and emails sent from Gmail or Hotmail.

The pandemic has accelerated digital transformation and consolidated it in the long term (Williamson, Citation2021). There were two positions regarding EdTech: techno-utopian enthusiasts who saw the pandemic as a great opportunity and a panacea for education in the ‘technological solutionism’ (Jasanoff, Citation2015); and critical voices that claimed that remote teaching would be a failure (referred to by Castañeda & Williamson, Citation2021). Changes around the world are still ongoing, and their evolution needs to be studied in order to understand the long-term consequences and how they influence educational systems worldwide (Williamson & Hoga, Citation2020).

There are many international studies discussing platformisation of education in different contexts. In Sweden, a speculative method was used by Hillman et al. (Citation2020) in order to criticise the problematic consequences of global digital platforms as well as the influences of policy makers. In the Netherlands, Kerssens and Van Dijck (Citation2021) discussed the platformisation role in public education networked in a private digital infrastructure based on a survey to ICT coordinators. Nichols et al. (Citation2020) argued how businesses are increasingly woven into education from teachers’ interviews in the USA. In Australia, Pangrazio et al. (Citation2022) developed a qualitative study to visualise the sociotechnical conditions of platforms and data infrastructures in schools.

Few studies are available referring to the Spanish context (Gutiérrez & Espinoza, Citation2020; Saura, Citation2020), and most of them deal with secondary and higher education (García Peñalvo & Corell, Citation2020; Molina-Pérez & Pulido-Montes, Citation2021). In Catalonia, Parcerisa et al. (Citation2022) studied Big Tech’s presence in education, concluding that the commercial platforms’ presence is mostly focused on technological aspects and data management risks involved. Their methodology entailed interviews with different experts in the field of digitalisation of education (with three academics from universities). Our study aims to gain a deeper understanding of the use of these platforms in primary schools from teachers’ perspectives.

The case of schools in Catalonia

In Catalonia, the Department of Education presented the Digital Education Plan of the region a year before the pandemic as an acceleration project that aimed to position Catalonia as a leading region in the use of technology for educational success, by ensuring that students, teachers and schools are digitally competent. Also, curricular deployment includes the digital competence as a basic, cross-curricular competence, referring to the creative, critical and safe use of digital technologies for learning (Decree 175/Citation2022, de 27 de setembre, d’ordenació dels ensenyaments de l’educació bàsica, 2022; European Commission, Citation2020).

According to a survey on equipment and the use of information and communication technologies in households, in 2021, 99.2% of children from 10 to 15 years old had been using the internet in the three months prior to the survey (Idescat, Citation2021). As far back as 2008, 98.1% of students from 10 to 15 years old had used a computer in class (Idescat, Citation2021). In 2021, in 10.4% of schools in Catalonia no teacher had been using technology, but in more than 50% of schools all teachers had been surfing the Web and using internet materials as a support (Departament d’Educació, Citation2021).

According to a strategic report by ACCIÓ, the agency for the competitiveness of the Administration of Catalonia, the education technologies sector, Edutech, is made up of 616 companies, which accounts for a turnover of 2306 million euros, 1% of Catalonia’s GDP (Acció, Citation2019). Regarding trends, the report notes that educational institutions are making progress in data processing in order to contribute to student success. Other trends include learning through video games, mobile education, the STEAM project and Google for Education.

Although the Department of Education carries out ‘Statistics of ICT equipment and uses’ surveys annually on the ICT services and the uses and knowledge of the educational staff in the digital field, the present study aims to identify presence, relations and trends in use of, as well as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on, digital platforms used in the particular case of primary schools in Catalonia.

Materials and methods

The research is based on a mixed-methods design encompassed in wider research, which considers quantitative and qualitative methods. The present study is the first quantitative phase, and the second derives from it and deepens it with a qualitative phase (Gonzalez-Mingot & Marín, Citation2022). This concrete study is based on a positivist paradigm of objectivity and analysis of the observable (Jorrín Abellán et al., Citation2021). It involves an iteratively expanding evidence base through empirical analysis based on quantitative measurement to overcome the biases of the researchers (Farrow et al., Citation2023).

The objective of the current study is to identify the presence, typology and frequency of use of global educational platforms at primary education level in the context of Catalonia. Also, it seeks to analyse the evolution of their use in time (by teachers and students) in order to identify the impact of the pandemic on platforms’ educational usage.

The research questions are:

What is the presence of global educational digital tools in Catalan primary schools?

What relations and trends in use and frequency can be identified?

What was the impact of Covid-19 on platforms’ use in education?

For this purpose, a validated ad hoc questionnaireFootnote1 for this study was used, as descriptive survey research to describe and explore variables of interest by using quantitative research strategies. The instrument for survey data collection with 29 questions was designed after reviewing national and international studies and surveys (Colclough, Citation2020; European Commission, Citation2019; Idescat, Citation2021; UNESCO, Citation2014). The questionnaire was addressed to teachers, and survey data from sections A (Basic data), B (Own use of digital tools) and D (Use by students of digital tools) were analysed. The instrument involved anonymous participation and was distributed by email. Data were collected between November 2021 and February 2022.

Validation of the instrument

The questionnaire was validated by a panel of experts, which makes it possible to determine knowledge about complex or little studied topics in great depth considering the ease of implementing it without many requirements. The validation group consisted of 10 experts with different profiles in the educational technologies field such as members of the international panel of research in educational technology (PI2TE)Footnote2, experts of Catalan universities and of the Department of Education of Catalonia.

Sample

The representative sample in the study was of 381 teachers, based on the population of 39,153 primary school teachers with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval. The sample represents 352 schools in Catalonia of a total of 3967 schools − 2662 public and 1305 private and partially public-funded private. Furthermore, proportionality by area has been maintained according to the number of schools and teachers in each area. Quota sampling has been used in non-probability sampling mode. The final sample exceeds the calculated representative sample (N = 491).

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics have been conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 data analysis software. Inferential statistics are considered as it is possible to infer the entire population due to working on a representative sample. This means that the results are applicable and can refer to the whole population according to the analysis. Variables have been adjusted to their values and labelled in order to carry out the analyses.

Firstly, data were grouped according to the research questions. Multiple response results have been adapted to dichotomous variables and open answers converted into new variables. Secondly, data related to the use of platforms were grouped according to the software approach and their licence type: proprietary platforms (from Big Tech, with a global approach or with limited scope), open source or non-commercial, from associations or non-profit organisations. These tool groupings (number of tools per software approach per person, scale variable) follow a non-normal distribution (p < .05), according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

The descriptive analyses include the calculation of frequencies, medians and standard deviations of the variables related to the research questions. Inferential statistics seek possible associations between two or more nominal and ordinal variables by using contingency tables with Chi-square and Phi and Cramer’s V. In the case of the exploration of associations between groups of tools (scale variable, non-parametric) and other nominal and ordinal variables, Spearman’s correlation was used. To compare between two groups of matched samples (teachers and students) before and after the pandemic, Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank (2 samples) was used.

Results

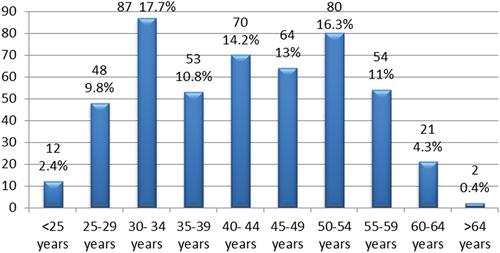

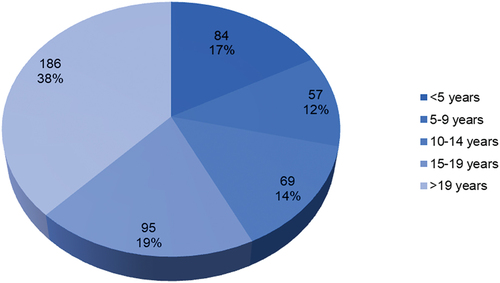

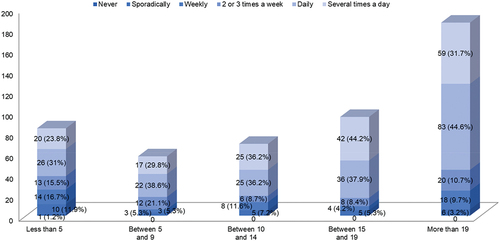

In terms of age, 74% of the teachers are between 30 and 54 years old with the median falling in the 40–44 year-old range (SD = 2.154) (see ). Concerning sex, 79.4% are women, 19.1% men and 1.5% do not state it. Regarding experience, 37.9% of the teachers have more than 19 years of experience, with the median at between 10 and 14 years (SD = 1.5) (see ). Regarding schools, 80.7% are teaching at public schools, while 0.6% work in private ones, and 18.7% in partially subsidised private schools. All 11 Catalan regions are represented.

RQ1.

Presence of global educational digital tools in Catalan primary schools

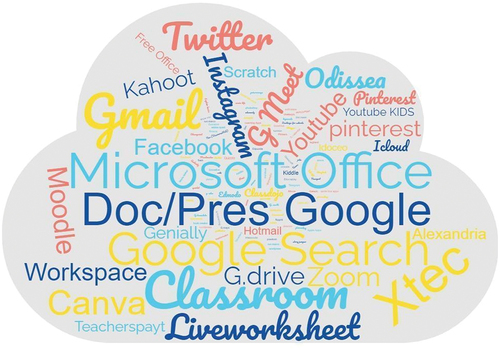

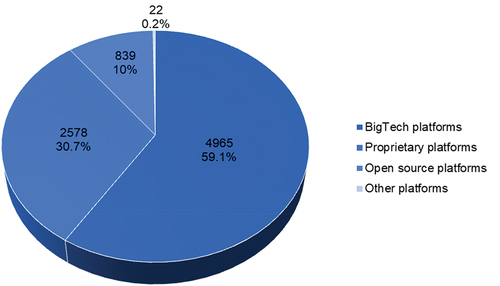

Overall, 137 different digital platforms are said to be used in primary schools by the teachers in the sample (see ). Of these tools, 89.8% used in primary schools in Catalonia are proprietary, compared to 10% that are open source (see ). Among the proprietary tools, local tools – proprietary with limited scope – account for only 0.42% compared to the vast majority of global tools present in the sample (59.1%).

Figure 4. Distribution by type of digital platforms used (n = 8404)3.

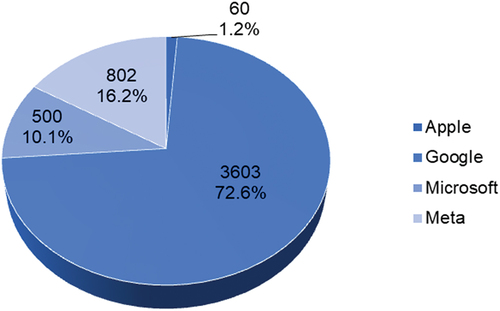

The figure of 59.1% represents the use of Big Tech tools, distributed among four companies: Microsoft, Meta, Apple and Google (). The platforms from the latter are the most used, with 72.6% (and 43% of the total). Amazon, the fifth biggest company, is also present under the Amazon Web Services (AWS) cloud use among Moodle (2.71%) and Wordpress (0.01%) users.

Figure 5. Distribution of Big Tech global platforms (n = 4965).Footnote3

Furthermore, only 0.08% of the digital tools present in Catalan schools are non-commercial tools, from associations or non-profit entities. Indeed, the four most used tools for communication and collaboration are from or related to Google: Google Drive (94.8%), Google Meet (90.8%), email XTEC (90.2%) and Gmail (76.5%). Meanwhile, Microsoft Office includes the preferred tools for carrying out teaching (90.2%), followed by Google Search (80.2%) and Google Classroom (80%). The top 10 classification of tools used in schools are proprietary and global, including seven of the first 10 tools related to Google, nine of which are from GAMAM (see ).

Table 1. Ranking of digital platforms most used in schools.

Related to type of school, some differences have been observed. One hundred per cent of private schools use Google Classroom and XTEC/domain (Educational Telematics Network of Catalonia), followed by 80% of public school use of Google Classroom and 94.9% of XTEC. However, 76% partially subsidised private schools make use of Google Classroom and 71.7% of XTEC. Although XTEC offers Google services to its staff through a business account (Google Apps Education), public schools use Hotmail more than the private ones. Private schools and partially subsidised private schools use Zoom more than public schools. Other noteworthy global tools according to the type of school are Edmodo and Teacherspay teachers for private schools and Liveworksheet for public centres. Taking these data into account, the following hypothesis is raised:

H1:

There is a relationship between the type of school and the type of digital platforms used.

A negative Spearman’s correlation between type of school and open-source digital tools was found (rS = −0.2, p < 0.05). Also, a positive correlation between type of school and proprietary with limited-scope digital tools can be interpreted (rS = 0.18, p < 0.05). This means that the use of proprietary with limited-scope platforms is related to type of school, and the use of open-source platforms is inversely related.

RQ2. Trends in use and frequency

Teachers

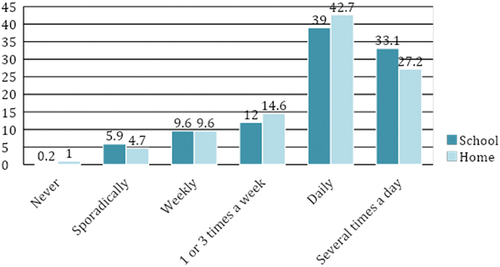

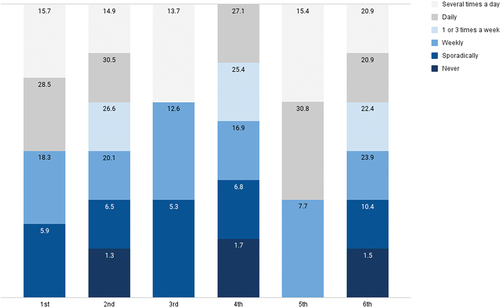

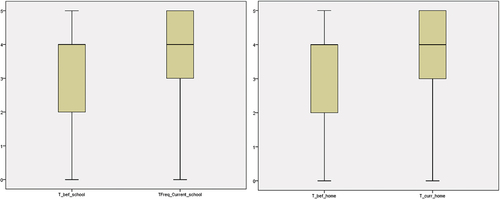

According to teachers’ use of digital tools and their frequency (see ), their educational use at home is slightly higher on a daily basis than in the school, being the frequency the most repeated.

Concerning experience (see ), all ranges of experience use more digital platforms on a daily basis except teachers with 15 to 19 and 10 to 14 years of experience. Percentages of zero and sporadic use, although low, are higher for those with less than five years of experience. Related to age, all ages show the same trend, except those younger than 29, who use them more several times a day (<25: 3.5% and 25–29: 3.3%). Also, 41.7% of teachers under 25 years of age use digital platforms several times a day, while 25% do so weekly. More teachers aged between 35 and 39 years use digital tools several times a day (43.4%) rather than daily (35.8%). Some specific cases have been observed: Teachers younger than 25 and older than 60 do not use Hotmail, although they do use other Microsoft products. Young teachers also use Moodle and Classroom in the same way (75%) although all other age groups use Google Classroom more than Moodle.

Data show that outliers use Google Workspace less (0% for teachers older than 64 years, but 100% Google Drive) and use Zoom more than other age ranges. One hundred per cent of these two groups use Microsoft Office, while those older than 64 years of age do not use OpenOffice at all. In view of these examples, the next hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

There is a relationship between age and/or experience and the use of digital tools.

As shown in , a negative relationship between age and proprietary tools with global scope has been found (rS = −0.2, p < 0.05), meaning that younger teachers make more use of proprietary tools. Again, a negative relationship is found between years of experience and proprietary platforms with global scope (rS = −0.18, p < 0.05), meaning that less experienced teachers use proprietary platforms more. Also, a positive relationship, although weak, is found with Big Tech (rS = −0.1, p < 0.05), meaning that more experienced teachers make greater use of such tools.

Table 2. Correlation between age and type of digital platforms used (N = 491).

As can be seen, there are some differences between frequency of use of digital platforms in schools and at home by teachers, as well as correlations regarding their type. The following hypothesis tested whether there were ongoing differences in this sense:

H3:

Relations between frequency of use and type of digital platforms are different in the school and at home.

shows a relationship between frequencies at school with Big Tech, proprietary and open-source tools as p < .05 (Sig.) with proprietary with global scope being the strongest one, which means greater frequency of use and more use of proprietary tools. The same trend has been observed with the frequency of use at home. Big Tech, proprietary global and open-source tools seem to be related, but the proprietary relation at home is weaker. Therefore, even though the strength of relationships is slightly different, the same trends can be observed.

Table 3. Correlation between frequency and type of digital platforms used at home and in school.

Students

Compared to teachers’ overall use of digital tools, students use them less frequently. A total of 29.8% of students use digital tools at school two or three times per week, and 28.1% daily, followed by 18.5% weekly. Only 0.6% have never used them. At home, 29.8% use them sporadically and 23.1% weekly. Twenty-one per cent of students used digital tools two or three times a week, and 6.7% never used them for educational purposes at home. Bearing this in mind, we aimed to identify different trends inside the school, specifically the use regarding grade level, class size and subjects.

H4:

Grade level is related to the type and frequency of digital platforms used.

Relationships have been found between the type of platforms used and grade level (). Firstly, between Big Tech and first graders (rS = 0.18, p < 0.05), third graders (rS = .1, p < 0.05) and fifth graders (rS = .09, p < 0.05). Regarding proprietary global platforms, a relationship is found with second graders (rS = .1, p < 0.05) and fifth graders (rS = .14, p < 0.05). Third graders’ use has a limited scope relationship with proprietary platforms (rS = .1, p < 0.05). A correlation is found between open-source platforms and use by first graders (rS = .2, p < 0.05), third graders (rS = .1, p < 0.05) and fourth graders (rS = .11, p < 0.05).

H5:

Class size is related to the type and frequency of digital tools used.

presents a relationship between class size and proprietary tools with limited scope (rS = .04, p < 0.05). Although no relationship is evident after performing the Chi-square test (p-value = 0.899), the contingency table shows a slight difference between groups of fewer students who never use digital platforms and those who do so more frequently compared to bigger classes.

H6:

Frequency of use of digital platforms is related to school subjects.

Table 4. Correlation between class size and frequency of students’ use of digital platforms.

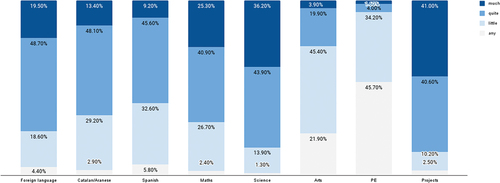

Digital platforms are ‘a lot’ and ‘quite a lot’ used in digital projects, followed by science, mathematics and foreign languages (). However, in physical education (PE) they are little or never used. The same can be said of the use of digital platforms in art classes. Those who use digital platforms more frequently tend to use them ‘a lot’ or ‘quite a lot’ in every subject, while the opposite is also true.

Different relationships have been observed between frequency of use and type of digital tools, enlarging the representation of digital platforms in school by teachers and students. Thus, the next hypothesis aims to find out any correlations related to students’ use.

H8:

There is a relationship between frequency of students’ use and type of digital platforms.

The data show evidence of a relationship between frequency of use of digital platforms and their type. Concretely, those who use digital platforms more frequently also do so with Big Tech (rS = 0.11, p < 0.05) digital platforms and proprietary tools with global scope (rS = 0.13, p < 0.05).

RQ3.

Impact of Covid-19. Pre-pandemic and post-pandemic situations at home and at school

Overall, 47.3% of the teachers stated making similar use of digital tools at the point of the study than before the Covid-19 pandemic. However, 18.3% did not use them at all, while 28.6% used them but less frequently. On the other hand, only 5.8% used them more frequently before Covid-19. However, when studying the responses independently, the data show a more significant increase, being higher among students than teachers.

Teachers

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, teachers have increased their use of digital tools at home and in school (see and ). Prior to that period, only teachers younger than 25 years old used digital tools several times a day at home (50%) rather than daily (25%). Since then, this situation has spread to teachers aged 25 to 29 years old. The percentage difference between teachers who never use digital platforms in school decreased by 83.3% after the Covid-19 pandemic. This decreasing trend is also observed in teachers who use them sporadically, weekly and two or three times per week. On the other hand, their use daily and several times a day has increased since the pandemic. Specifically, 59.9% use them several times a day in school, and 48.63% at home.

Figure 10. Frequency of teachers’ use of digital platforms in school and at home before and after Covid (N = 491).

Table 5. Frequency of teachers’ use of digital platforms before and after Covid-19 (N = 491).Footnote4

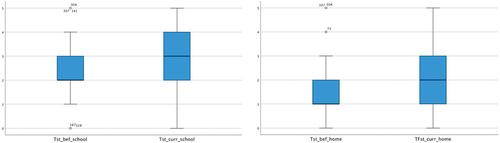

Students

Before the pandemic, 39.8% of students used digital tools sporadically at home and 23.6% never did, according to their teachers’ survey answers. This number has decreased significantly to 6.5% since the Covid-19 pandemic. Low frequencies have increased and vice versa. Concerning their use in school, before the pandemic, 6.7% used them several times a day, and after the pandemic, this figure increased by 126.9%, and 80.2% daily. The same trend as use at home has been observed, with a 119% increase in daily use since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Supporting hypotheses have been proposed to answer the causal question according to the results: Does the Covid-19 impact the use of digital tools in schools after the pandemic?

H0:

There is no Covid-19 impact on the frequency with which teachers used digital tools.

H1:

There is a Covid-19 impact on the frequency with which teachers used digital tools.

The null hypothesis is rejected, since p < .05, so Covid-19 has impacted the teachers’ use of digital platforms as there are significant differences between the frequency before and after the pandemic (T = 20280.500). Although the medians of both points in time are the same (Mdn = 3), upon inspection it appears that after the pandemic their use was more frequent (higher percentages of use daily and several times a day), as shown in and .

Figure 11. Frequency of students’ use of digital platforms in school and at home before and after Covid (N = 491).

Table 6. Frequency of students’ use of digital platforms before and after the Covid-19 pandemic (N = 491).

Discussion

The current presence of global educational digital tools in Catalan schools in primary education is significant (89.8%), with those of Big Tech being most used (59.1%) ahead of open-source tools (10%). This is in clear contrast to the equally distributed technological solutions between private licences and free licences in Argentina according to a post-pandemic research study (BID, Citation2021). Even though the Catalan Department of Education provides a virtual environment based on Moodle (Àgora and Eix), only 2.7% of teachers were using it. This raises two further points for analysis: first, the presence of one of the Big Tech companies under the open-source Moodle platform as it is hosted in AWS in order to improve its scalability and maintainability (IthinkUPC, Citation2020). And second, statistics published by the Department of Education point to 56.2% use of other VLEs. However, this study has shown that 79.6% teachers use Google Classroom, as schools, based on self-governance, can choose to use different platforms. This is an example of platforming third-party providers on the cloud and private infrastructural dominance based on market profits (Williamson et al., Citation2022) in favour of school privatisation and platformisation as in the Netherlands (Kerssens & Van Dijck, Citation2021) and Sweden (Hillman et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, many trends and relationships have been discovered regarding the type and frequency of tools used. Concerning teachers’ use, a relationship between frequency and years of experience has been found, agreeing with the affirmation that younger teachers use digital platforms more frequently (Muñoz Carril & González Sanmamed, Citation2011). However, in our study, when referring to Big Tech platforms, more experienced teachers make slightly greater use of them. Correlations between frequency of use and type of digital tools have been found according to Big Tech, proprietary and open source in the school, and the same trend is observed at home. Compared to students’ frequency of use of digital platforms according to their teachers, only Big Tech and proprietary tools with global scope are related. Overall, teachers use digital tools more frequently than students. While the statistics of ICT equipment and uses (Departament d’Educació, Citation2021) point to 10.4% of schools in Catalonia where no teacher uses technology, our study would suggest a figure of 0.2% in contrast with the 33% highly digitally active European teachers (European Commission, Citation2019).

Trends and relations observed concerning students’ use also help to understand how digital competences are learned transversally. Despite being cross-curricular competences (European Commission, Citation2020), they are not developed into all subjects to the same extent. Our results point to Science and project-based learning as the contexts where digital platforms are most used, with Art and PE as subjects where they are significantly less used. This is similar to the curricular areas not covered by EdTech solutions in Argentina (BID, Citation2021).

An increase in the use by teachers and students of digital tools has been observed in both school and home since Covid-19. Although a study carried out by EduCaixa (Citation2020) with a sample of 1600 teachers in Spain reports a 94% increase in professional use by teachers in Spain, the present study has resulted in a 42.6% median increment for teachers in Catalan schools, and 35% at home. In line with the Argentinian context, where most of the technological solutions were developed mostly from Covid-19 (n = 58), digital educational resources (79%) are from the business sector (BID, Citation2021). When looking at the numbers for students in our study, these are significantly higher than for teachers, as the percentage of students who increased their use of digital platforms grew by 103.7% at school and 74.9% at home, considered from the teachers’ perspectives. In comparison with the Spanish context, research by Qustodio (Citation2020) points to a 54% increase in the use of applications.

Therefore, the platformisation of pedagogy points towards the expansion of educational tools into homes – both as curricular content and as ‘edutainment’ – complemented with classroom management tools (such as ‘Class Dojo’, used by 22.4% of respondents). During the Covid-19 pandemic, many schools relied on digital platforms at home to carry out remote teaching. These platforms are now being used on a daily basis around the world and appear to build on established forms of communication reconfiguring the school–home relationships (Sefton-Green & Pangrazio, Citation2021).

Overall, according to the Ontsi report (Citation2022), 98% of Spanish people younger than 16 years old use the internet on a regular basis. Furthermore, the percentage of computer use is higher in Catalonia (99%) than in other parts of Spain. In this regard, this study has concluded that the presence and use of global digital tools in Catalan primary schools is significantly high (89.6%) in comparison to countries with more than 90% of highly digitally equipped and connected schools such as Denmark, Sweden and Norway (European Commission, Citation2019).

GAMAM platforms are the most used tools in Catalan primary education schools (59.1%). In the present study, Google comprises 72.6% of users, Microsoft 10.1% and Apple only 1.2%, compared to cloud services used by 84.8% of Catalan schools, of which 87.8% use Google, 11.4% Apple and 18.7% Microsoft (Departament d’Educació, Citation2021). Our findings coincide with the ones from an US report that show that, according to teachers’ interviews, 68% schools used Google for Education tools, 17% Microsoft tools and 1% of Apple tools (Edweek, Citation2017), even though the data were collected before the Covid-19 pandemic.

As can be seen, Google Drive is the most used platform in Catalan schools, although in Spain the most popular is Google Classroom (Qustodio, Citation2020). YouTube, said to be one of the platforms most accepted by teachers (Snelson, Citation2011), is in seventh position, used by 79.9% of respondents. Its use is much more widespread than YouTube Kids (19.5%), created with the idea of providing a safe environment for children.

In this regard, it is important to consider the effect of the platformisation process, also called soft-privatisation (Cone & Brøgger, Citation2020). Education privatisation and marketisation are interconnected and globalising phenomena (Rizvi et al., Citation2022). This trend is shared by other platformised educational systems, such as, for example, the USA. with the expansion of Google apps. Many teachers affirm that Google services play a central role in the teaching and learning process (Nichols et al., Citation2020).

According to the Analytical Framework of the Platformisation of Education (Rivas, Citation2021), which allows the construction of scenarios for planning digital educational policies, the level of platformisation of the Catalan educational system indicates the number of connections between students and learning, converted into operable data within a platform. Considering the areas analysed in this study, the Catalan educational system can be defined as a hybrid scenario combining platformisation with pedagogical innovation situated between the formal curriculum and informal learning as the Catalan administration does not fully centralise digital resources. This favours large private markets for the sale of platform services in schools and the expansion of digital networks and boundaries, reconsidering public forces against privatisation and commercialisation of education. This situation is observable in other contexts, such as in the decentralised and marketised educational system of Sweden (Hillman et al., Citation2020) or in the Netherlands, where local structures, woven into globally networked markets, are emerging in a geopolitical context regulated by economic interests (Kerssens & Van Dijck, Citation2021).

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, some recommendations at different levels are proposed. First, at the policy level, policy makers should build a general framework to regulate the significant provision of proprietary and global platforms in use, as well as for the management and custody of the data that this use generates. It can work for guiding countries individually, and advising and exchanging practices and evidence collaboratively (European Commission, Citation2019) to select and monitor the implementation of digital technologies.

Second, at the national and regional level, tailor-made implementation of the framework needs to be adapted to the contexts in order to guarantee the free public character of education. Due to this reason, and considering the global increase in use of digital tools and increased frequency of use, teacher professional development must be promoted as well as economic incentives or compensation of hours to reward the sustainable use of digital tools. In this sense, the difference of use between public, private and subsidised private schools must be mitigated to increase the equality gap between those systems. Also, we suggest that open-source alternatives should be promoted in the public infrastructure, such as the proposal of Digital Democratic (Xnet, Citation2020), and related support should be provided to maintain these infrastructures with secure hosting and specific professional staff.

Third, at the school level, critical and deep reflection should be prioritised on the use of platforms according to students’ needs by considering their grade level, class size and subjects when justifying decision-making on platform selection, rather than taking platformisation for granted. For example, scheduling time for teachers in order to organise regular discussions, generating written statements of the coherence of platforms with pedagogical purposes and assessing their application in classrooms through evidence-based learning based on curricular adequacy and students’ learning impact, would raise teachers’ awareness of the responsible and sustainable use of digital tools. Lastly, we strongly recommend teachers, and the whole educational community, to be cautious and aware of the implications of platformisation and be digitally competent to guide students’ practice beyond dependency on platforms, as well as consider reimagining alternatives.

Conclusions

The present study contributes to analysing in greater depth the use of digital platforms in Catalan schools, even though some studies have already identified concrete platforms in broader contexts or particular trends of use in the Catalan context. Thus, a broader approach of analysis and interpretation has been applied to understand digital platforms in the current Catalan educational system that works as a mapping example of the quantitative post-pandemic state of affairs.

The presence of educational digital tools in Catalan primary schools is wide and varied, with global platforms being used the most, and specifically those of Big Tech companies led by Google, reproducing similar dynamics of power as in other contexts such as the USA, the Netherlands or Sweden. Many trends in use and frequency have been identified, as younger teachers use digital platforms more frequently, but not always those with less work experience. Data also show the relationship between frequency of use by students of digital platforms and Big Tech and proprietary tools with a global scope. The Covid-19 pandemic impacted the use of digital technologies by students and teachers, increasing it in schools and at home. This impact is potentially reproduced in the use of digital technologies in the educational systems, as in the Catalan example in this study, which contributes to enriching cross-cultural research to better identify and understand platformisation as a broad issue (Selwyn et al., Citation2020).

However, the study has faced some limitations, such as the need to prioritise the analysis of questions and to achieve a greater precision to find out the frequency of use of each platform. Also, the type of study conducted does not provide information on the impact that the use of the different platforms had on students and teachers, which should be explored in depth through qualitative methods and shows a future line of research.

Despite the widespread use of commercial digital platforms in schools as seen in the study, there are few scientific studies that assess the impact of their use on teachers and students beyond Covid-19 solutions (BID, Citation2021; Myers et al., Citation2022), especially in the context of the primary education school. In this sense, we encourage researchers to pursue this line in order to explore the impact of digital platforms on contemporary schooling, as well as to focus on the relationship of platformisation with the current process of datafication and data infrastructures, which raises numerous ethical questions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the experts participating in the validation of the questionnaire and the teachers participating in the survey study. We also appreciate the efforts of the reviewers for their insightful comments that have improved the level of interest of the study at an international level.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sandra Gonzalez Mingot

Sandra Gonzalez Mingot is a doctoral student in the interuniversity PhD programme of Educational Technology at the University of Lleida (Spain) and member of the research group COMPETECS at the same university. She is a journalist and primary and secondary teacher, working currently as a digital mentor for the Educational Department of Catalonia.

Victoria I. Marín

Victoria I. Marín is a Senior Research Fellow (Ramón y Cajal) in the Department of Pedagogy at the University of Lleida (Spain) and member of the research group COMPETECS at the same university. She holds a PhD in Educational Technology from the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB). She is a research collaborator of the Educational Technology Group of the UIB affiliated to the Institute for Educational Research and Innovation and member of the Center for Open Education Research (Oldenburg, Germany).

Notes

1. https://zenodo.org/records/7543744

2. http://panel.edutec.es/index.php/pi2te/Pi2TE

3. This figure was adapted for a Catalan conference from which an article was derived for informational purposes (Gonzalez-Mingot & Marín, Citation2023).

4. An adapted and reduced version of the table was presented in a Catalan conference from which an article was derived for informational purposes (Gonzalez-Mingot & Marín, Citation2023).

References

- Acció. (2019). El sector de les tecnologies de l’educació (edtech) a Catalunya. https://www.accio.gencat.cat/web/.content/bancconeixement/documents/pindoles/edutech-pindola-sectorial-ok2.pdf

- BID. (2021). Soluciones Ed Tech en Argentina: Perspectivas y desafíos en tiempos de pandemia. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/Soluciones-Ed-Tech-en-Argentina-Perspectivas-y-desafios-en-tiempos-de-pandemia.pdf

- Castañeda, L., & Williamson, B. (2021). Assembling new toolboxes of methods and theories for innovative critical research on educational technology. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2021.1.703

- Colclough, C. (2020). Survey report | teaching with tech: The role of education unions in shaping the future. Education International. https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/23602:survey-report-teaching-with-tech-the-role-of-education-unions-in-shaping-the-future

- Cone, L., & Brøgger, K. (2020). Soft privatisation: Mapping an emerging field of European education governance. Globalisation, Societies & Education, 18(4), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2020.1732194

- Decree 175/2022, de 27 de setembre, d’ordenació dels ensenyaments de l’educació bàsica. (2022). DOGC, No. 8762. September 29, 2022. https://dogc.gencat.cat/ca/document-del-dogc/?documentId=938401

- Departament d’Educació. (2021). Estadístiques de l’ensenyament. Equipament i usos de les TIC. https://educacio.gencat.cat/ca/departament/estadistiques/equipaments-usos-tic/

- Educaixa. (2020). Docentes en época de confinamiento. https://educaixa.org/documents/10180/49021935/Docentes+en+%C3%A9poca+de+confinamiento_final+%281%29.pdf/6ae8b1f2-d95e-3c51-d266-4fdc5dd1d05f?t=1600969954417

- Edweek. (2017). Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft: How 4 tech titans are reshaping the ed-tech landscape. Market Brief. https://marketbrief.edweek.org/special-report/amazon-apple-google-and-microsoft-battle-for-k-12-market-and-loyalties-of-educators/

- European Commission. (2019). 2nd survey of schools: ICT in education: Objective 2: Model for a ‘highly equipped and connected classroom’, final report. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/831325

- European Commission. (2020). Digital education action plan (2021-2027). Educación y Formación - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/education/education-in-the-eu/digital-education-action-plan_en

- Farrow, R. (ed.), Weller, M., & Witthaus, G. (2023). The GO-GN open research handbook. Global OER Graduate Network/Open Education Research Hub. https://go-gn.net/gogn_outputs/open-research-handbook/

- García Peñalvo, F. J., & Corell, A. (2020). La CoVId-19: ¿enzima de la transformación digital de la docencia o reflejo de una crisis metodológica y competencial en la educación superior? Campus Virtuales, 9(2), 83–98. http://hdl.handle.net/10366/144140

- Gonzalez-Mingot, S., & Marín, V. I. (2022). Edtech ecosystems in education: Catalan educators’ perspectives on digital actors. [Manuscript submitted for publication].

- Gonzalez-Mingot, S., & Marín, V. I. (2023). Les plataformes digitals a l’educació primària de Catalunya: una qüestió d’ètica. Revista Catalana de Pedagogia, 24, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.2436/20.3007.01.193

- Gutiérrez, E. J. D., & Espinoza, K. G. (2020). Educar y evaluar en tiempos de Coronavirus: La situación en España. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 102–134. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2020.5604

- Hillman, T., Rensfeldt, A. B., & Ivarsson, J. (2020). Brave new platforms: A possible platform future for highly decentralised schooling. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1683748

- Idescat. (2021). Estadística. Ensenyament Enquesta sobre equipament i ús de TIC a les llars. https://www.idescat.cat/estad/ticl

- IthinkUPC. (2020). Migració d’ÀGORA, l’entorn virtual d’aprenentatge del Departament d’Educació, a Amazon Web Services. https://www.ithinkupc.com/ca/referencies/migracio-dagora-lentorn-virtual-daprenentatge-del-departament-deducacio-a-aws

- Jarke, J., & Breiter, A. (2019). Editorial: The datafication of education. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1573833

- Jasanoff, S. (2015). Future imperfect: Science, technology, and the imaginations of modernity. Dreamscapes of modernity, In S. Jasanoff & S.-H. Kim (Eds.). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226276663.003.0001.

- Jorrín Abellán, I. M., Fontana Abad, M. & Bartolomé Rubia, A. ( Coor.). (2021). Investigar en educación. Síntesis.

- Kerssens, N., & Van Dijck, J. (2021). The platformization of primary education in the Netherlands. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1876725

- Krutka, D. G., Smits, R. M., & Willhelm, T. A. (2021). Don’t be evil: Should we use Google in schools? Tech Trends, 65(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00599-4

- Lindh, M., & Nolin, J. (2016). Information we collect: Surveillance and privacy in the implementation of Google Apps for education. European Educational Research Journal, 15(6), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116654917

- Molina-Pérez, J., & Pulido-Montes, C. (2021). COVID-19 y Digitalización ‘Improvisada’ en Educación Secundaria: Tensiones Emocionales e Identidad Profesional Cuestionada. Revista Internacional de Educación Para La Justicia Social, 10(1), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.15366/riejs2021.10.1.011

- Muñoz Carril, P. C., & González Sanmamed, M. (2011). Conocimientos del profesorado universitario en herramientas telemáticas. CPU-e, Revista de Investigación Educativa, 13(13), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.25009/cpue.v0i13.39.

- Myers, C., Wyss, N., Villavicencio, X., & Coflan, C. (2022). Mapping and analysing EdTech initiatives in Latin America and the Caribbean. EdTech Hub. https://doi.org/10.53832/edtechhub.0111

- Nichols, T., LeBlanc, R., & Rowsell, J. (2020). Beyond apps: Digital literacies in a platform society. The Reading Teacher, 74(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1926

- Ontsi. (2022). El uso de las tecnologías por los menores en España | Ontsi—Red.es. https://www.ontsi.es/es/publicaciones/uso-nuevas-tecnologias-menores-Espana-2022

- Pangrazio, L., Selwyn, N., & Cumbo, B. (2022). A patchwork of platforms: Mapping data infrastructures in schools. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2035395

- Parcerisa, L., Jacovkis, J., Rivera-Vargas, P., & Herrera-Urízar, G. (2022). Corporaciones tecnológicas, plataformas digitales y privacidad: Comparando los discursos sobre la entrada de las BigTech en la educación pública. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, 42(42), 221–239. Article 42. https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.42.2023.34417

- Qustodio. (2020). Conectados más que nunca. https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/ficherosoia/documentos/7131_d_Qustodio-2020-report.com

- Rivas, A. (2021). The platformization of education: a framework to map the new directions of hybrid education systems—UNESCO Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377733

- Rizvi, F., Lingard, B., & Rinne, R. (2022). Reimagining globalization and education. Routledge.

- Saura, G. (2020). Filantrocapitalismo digital en educación: Covid-19, UNESCO, Google, Facebook y Microsoft. Teknokultura: Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 17(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.69547

- Sefton-Green, J., & Pangrazio, L. (2021). Platform pedagogies – Toward a research agenda. Algorithmic rights and protections for children. https://wip.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/platform-pedagogies/release/1

- Selwyn, N. (2012). Education in a digital world: Global perspectives on technology and education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108178

- Selwyn, N., Hillman, T., Eynon, R., Ferreira, G., Knox, J., Macgilchrist, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2020). What’s next for ed-tech? Critical hopes and concerns for the 2020s. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1694945

- Sinha, S. (2021). More options for learning with google workspace for education. Google. https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/education/google-workspace-for-education/

- Snelson, C. (2011). YouTube across the disciplines: A review of the literature. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/edtech_facpubs/11

- Toscano, A. (2012). Analyzing technology to uncover social values, attitudes, and practices. In A. A. Toscano (Ed.), Marconi’s wireless and the rhetoric of a new technology (pp. 31–55). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3977-2_2.

- UNESCO. (2014). Analytical survey ‘ICT in primary education: Collective case study of promising practices’. Volume 3. UNESCO IITE. https://iite.unesco.org/publications/3214736/

- UNICEF. (2020). ¿Cómo están afrontando los docentes la crisis del COVID-19?. https://www.unicef.es/educa/blog/docentes-frente-al-coronavirus

- Williamson, B. (2021). Education technology seizes a pandemic opening. Current History, 120(822), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.822.15

- Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

- Williamson, B., Gulson, K., Perrotta, C., & Witzenberger, K. (2022). Amazon and the new global connective architectures of education governance. Harvard Educational Review, 92(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-92.2.231

- Williamson, B., & Hoga, A. (2020). Commercialisation and privatisation in/of education in the context of Covid-19. Issuu. https://issuu.com/educationinternational/docs/2020_eiresearch_gr_commercialisation_privatisation

- Winter, E., Costello, A., O’Brien, M., & Hickey, G. (2021). Teachers’ use of technology and the impact of Covid-19. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916559

- Xnet. (2020). Educación: Privacidad de datos y digitalización democrática. Xnet - Internet, derechos y democracia en la era digital. https://xnet-x.net/es/?p=19923