ABSTRACT

This paper explores the professional practice of the Action Learning (AL) facilitator through a process of critical inquiry, self-reflection and evaluation of action learning practice within a Higher Education Leadership Programme, commissioned by an English NHS Mental Health Trust. Action research was adopted as the overarching research approach which was built into the one-year post graduate programme. This enabled planning, fact-finding, and taking actions in analysing the role of the AL facilitator as an iterative process to explore the practice of action learning facilitation. It involved examination of the complexities and dynamics within an AL process and how learning and action is facilitated, as well as different relational dimensions that the facilitator must be aware of to effectively manage and support AL set members. Thematic analysis, which involved a 5-step process, was used to collate and investigate the research data. Results from this research reinforce the significance of the role of the AL facilitator in the learning process and offer a framework for pedagogy of AL facilitation presented as the art, craft and apparatus of AL facilitation practice. This framework contributes to the current AL literature by offering a holistic point of reference for the learning and practice of AL facilitation.

Introduction

Action learning involves working on real issues in small groups to solve problems through learning and reflection. As originally intended by Revans (Citation1980; Citation1998), action learning facilitation is now widely used as a learning intervention for leadership and organisational development (Leonard and Lang Citation2010; Marquardt and Banks Citation2010; O’Neil and Marsick Citation2007; Raelin Citation2008). Although Revans (Citation1998; Citation2011) was wary of action learning groups becoming dependent on facilitators, he also noted the value of this approach when he stated, ‘The clever man will tell you what he knows; he may even try to explain it to you. The wise man encourages you to discover it for yourself’ (Citation1980, 9). Marquardt and Waddill (Citation2004) also observed that action learning coaches should only ask questions relating to the learning of the group and have the wisdom and self-restraint to let the participants learn for themselves and from each other.

As the practice of action learning has developed in recent years, the role of the designated action learning facilitator, mainly referred to as the ‘coach’ (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014) or ‘a set advisor’ (Pedler and Abbott Citation2013) in the literature has been recognised. The action learning facilitator helps the members to make connections between learning and work experience through critical questions, which then promotes action, enabling members to perform their tasks more effectively (Lawless Citation2008; Pedler Citation2005; Ram and Trehan Citation2009; Rigg and Trehan Citation2004). Other authors, such as Marquardt et al. (Citation2009) and Rimanoczy and Turner (Citation2008) also support the use of an action learning coach to establish the structure, rules and pace of the action learning sessions sensitively and clearly. O’Neil and Marsick (Citation2014) advocate that an action learning coach can support participants to overcome their own assumptions and support their abilities to diagnose patterns, recognise how the new situation differs from previous situations, and create new responses through questioning and reflection. However, these authors have highlighted that there is limited research on the role of the action learning facilitator i.e. What does the facilitator do? What does the facilitator not do? What happens in the action learning sessions? Hence, there is a need for research on action learning facilitation to gain further insights into this practice.

This research addresses this gap by providing empirical evidence on the practice of the action learning facilitation, with insight into the cognitive and emotional aspects of facilitating goal-oriented groups. This involved systematic collation and analysis of empirical data on the role and style of action learning facilitation and impact on the members over a period of delivery of action learning sessions within a leadership programme. The empirical evidence of the conditions, capabilities and processes for effective facilitation has enabled the development of a pedagogic model of action learning facilitation which is offered as a holistic point of reference for learning and practice in this role, and more widely for facilitation of learning.

In this paper, I first present literature with a specific focus on the role of the facilitator in action learning, followed by the research context and methodology. Next, the research findings are presented specifically under the research lens of the commitment and values that underpin the AL facilitator’s practice (the art of AL facilitation), the skills and knowledge of the AL facilitator (the craft of AL facilitation) and the processes and structures that support AL facilitation (the apparatus of AL facilitation). The paper concludes with illustration of the pedagogic model of action learning facilitation and its application across educational programmes.

Role of the facilitator in action learning

There are many different views on the practices of the Action Learning Facilitator (ALF); some key themes and recurring views are considered here. As an important aspect of action learning is ‘coaching’, the term ‘action learning coach’ is referenced throughout the literature on AL, mainly influenced by the World Institute of Action Learning (WIAL) brand of action learning. The designated action learning coach, through critical questions, helps group members to make connections between learning and work experience, which then promotes action, enabling members to perform their tasks more effectively (Lawless Citation2008; Pedler Citation2005; Ram and Trehan Citation2009; Rigg and Trehan Citation2004). The establishment of structure, rules and pace of the session can also be facilitated by this coach (Marquardt et al. Citation2009; Rimanoczy and Turner Citation2008). O’Neil and Marsick (Citation2014) highlight that in the Tacit and Scientific schools of action learning, there is little emphasis on the use of a ‘coach’ to enable learning, as the focus is primarily on action and results. However, within the Experiential and Critical Reflection schools of action learning, the authors believe that the role of a learning coach is critical. The authors highlight a number of reasons for this, such as: the participants’ inability to recognise their own assumptions and patterns of thought and behaviour (Boud and Walker Citation1996), impatience and discomfort with one’s own practice (Marsick and Maltbia Citation2009) and inability to question (Cho and Bong Citation2010). They argue that an action learning coach can support participants to overcome these barriers and ensure an explicit focus on ‘learning how to learn’ by supporting their abilities to diagnose patterns (even though context varies), recognise how the new situation differs, and adjust or create new responses through questioning and reflection (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014, 206). More generally, Stewart (Citation2006) in her study on group facilitators, suggests that high performing facilitators offer the right balance between meeting objectives, managing time and encouraging participation, with emphasised empathy, emotional resilience, stress tolerance and self-awareness.

According to authors such as Marquardt et al. (Citation2009) and Edmonstone (Citation2017), questioning is the life blood of action learning because questions are seen as the most effective tool to understand the complexity of the problem, to develop innovative strategies, build team cohesiveness and develop the leadership skills of group’s members. The AL coach tries to primarily use questions, rather than give answers (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2007). Other authors, such as Cho and Bong (Citation2010), Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe (Citation2010) and Gibson (Citation2011) also argue that the coach can foster an attitude of inquiry through questioning. In addition, the coach helps participants to learn how to ask the ‘right’ questions and through these questions, learn how to think in new ways (Hoe Citation2011; Pedler Citation1991).

Literature on AL establishes that reflection is intrinsically bound to questioning as it is often guided by good facilitation questions (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2007). The AL coach enables a divergent form of learning which is particularly conducive to periods and places of uncertainty, ambiguity and change, which characterise action learning (de Haan and de Ridder Citation2006). Thus, the primary focus of the coach role is not to teach or provide an expert perspective, but to create conditions under which participants might learn from their project work and from one another (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014, 207). Tolerance of ambiguity, openness, frankness, patience and empathy are some of the key qualities required by the facilitator for this (Edmonstone Citation2017). Casey (Citation2011), in his seminal work on set advising (AL coaching), speaks of the need for a coach to challenge a team in order to help them think differently. Thus, the coach’s capability to ‘hold’ difficult conversations is indispensable in promoting learning (Thornton Citation2016; Winnicott Citation1965; Citation1971).

According to Casey (Citation2011) and O’Neil and Marsick (Citation2007; Citation2014), another aspect to be considered is that, before learning can happen, sufficient trust is needed for participants to feel they can take risks such as: exposing personal information, questioning themselves and others, engaging in reflection and challenging the organisation. The coach ensures equity among members as well as efficiency and accountability for results in both process and outcomes. Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe (Citation2010, 206) argue that ‘the coach is not a teacher or training manager delivering classroom-based problem solving or interventions’, neither are they ‘a work supervisor who has accountabilities in terms of productivity and efficiency’. Bourner, Beaty, and Frost (Citation1997) suggest that the coach ideally is an independent person who has the capacity to guide group members in how to learn, listen, use empathy, identify and challenge assumptions, reflect critically, reframe issues, receive and give feedback effectively and think reflectively. Edmonstone (Citation2017, 80) refers to the activities of support offered by the AL facilitator as ‘emotional warmth’ and challenges assumptions, perceptions and mind-sets as the ‘light’ to the learning process.

The role of the action learning coach also includes assisting members to focus on what they are achieving and finding difficult (Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe Citation2010, 217). Without a coach, all of this would be left to chance and to the accidental or serendipitous application of process skills by group members (Marquardt et al. Citation2009). Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe (Citation2010, 217) suggest that ‘the action learning coach should be sensitive to and allow time for group members to understand the external, as well as internal environments’. These authors state that action learning coaches can guide teams and groups to reflect on what they can influence and control, as well as how they can learn continually from their shared experiences. According to Bourner, Beaty, and Frost (Citation1997), action learning coaches need to intervene at appropriate times to motivate, advise and educate the AL members, in order to enable them to reflect on the efforts, strategies, knowledge and skills generated within the AL set. The coach helps the group to reflect on the possible performance and problem-solving levels they can attain as individuals, teams and as an organisation (Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe Citation2010).

Several authors refer to the importance of creating an environment for learning by the AL coach. Lamm (Citation2000) found that participants needed an open, trusting and supportive environment for transformative learning to happen. Other authors, such as Teekman (Citation2000), O’Neil and Marsick (Citation2007) suggest that creating a learning space requires specific action learning interventions such as emphasis on confidentiality and a supportive environment. Anderson and Thorpe (Citation2004) and Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe (Citation2010) also highlight that the coach needs to create an environment that is safe and empowering for individuals, where the members feel they own the solutions, can challenge each other by asking questions and engage in reflective inquiry and powerful actions.

Pedler and Abbott (Citation2013) highlight that a key role of an action learning practitioner is that of a ‘set adviser’ rather than a ‘coach’ who works with the set members to help the set to become an effective source of action, learning and reflection. This involves encouraging the development of skills, such as presenting issues, listening, questioning, reflecting and acting. Thornton and Yoong (Citation2011) refer to the role of a ‘blended action learning facilitator’ within an ICT-supported leadership programme in the New Zealand educational sector. They found a contributor to the success of this programme was this role, which involved enabling learning and acting as a ‘trusted inquisitor’; this position required supporting and challenging participants in their leadership learning.

Overall, the above literature highlights this facilitation role as coach, a set advisor and a blended action learning facilitator. The ‘action learning coach’ seeks to open minds to a deeper level, aimed at self-discovery through one’s own experience and critical reflection (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014) maintains the balance of managing the process with the required questioning (Rigg Citation2006), enable new insights to complex emotions, unconscious processes through an active facilitation (Vince Citation2004; Citation2008; Vince and Martin Citation1993) and offer advice to enable reflection, learning and action (Pedler and Abbott Citation2013). These key aspects have informed my research inquiry and I have proposed the use of the term ‘action learning facilitator’ (ALF) to encompass the wide range of capabilities and contexts of action learning as presented in the discussion and conclusion section.

More broadly, pedagogy, although a contested concept, has been viewed as the art, craft and science of creating an educational process that develops a dialogical relationship between the educator and the learner, enabling learning and knowledge transfer (Alexander Citation2008; Smith and Smith Citation2008; Tsabar Citation2017). This definition will be drawn upon to explore the pedagogical practices of ALFs and develop a framework for pedagogy of AL facilitation.

Research context and method

The overall context of the research is within a UK post-graduate leadership development programme commissioned by an English NHS Mental Health Trust (MHT) with the aim of improving the leadership capacity of mid-level managers. The participants were mainly in management roles, either with direct line management responsibilities, or with supervision and project involvement requiring people management capabilities, working in both clinical and non-clinical services. The programme consisted of six dedicated ‘study-days’ incorporating content on managing and leading people and teams and a series of four facilitated half day action learning sessions. The action learning sets were facilitated by a team of three academic/practitioner professionals. I designed the programme content, including the process and structure for the AL sets and facilitated one of the sets. The purpose of the action learning was to provide a safe and confidential forum for participants to consider their current leadership and/or management issues and apply relevant leadership concepts, models and contexts addressed within the study days to gain deeper and new insights, to enable them to resolve real work problems (Dilworth and Willis Citation2003). The process and structure for each action learning session were used by all facilitators as a guide for the action learning sets. The Action Learning facilitator’s experience of group facilitation, programme design and delivery as an accoucheur (Revans Citation1998) supported this component of the programme. A group reflective gathering of the facilitators was also set up after each action learning session which provided opportunity for both individual and collective reflections to consider and improve practice, using an action research approach.

The programme assessment comprised a reflective review by each participant of professional learning and a critical reflection on their personal leadership journey in the implementation of a ‘stretch-project’ within their workplace. The programme has its own evaluation strategies such as evaluation questionnaires and focus groups aimed at collating feedback for on-going improvement of the programme. This specific research context is within the third cohort of the programme, consisting of 15 participants, delivered between January 2016 and December 2016. The participants within this cohort formed three AL sets with five members in each set. Mindfulness practice was applied as an AL process to ‘check-in’ by the AL facilitators. Approval from the university’s Research Ethics Committee was secured and all research participants completed an informed consent form.

The overarching research approach was a collaborative inquiry with and for people rather than on them (Heron Citation1996; Reason Citation1988), which involved cycles of review, development and improvement. As a result, action research (Heron and Reason Citation2008; Marshall Citation2011) was the most appropriate research framework for this inquiry. Marshall’s (Citation2011) first person and second person action research approach was adopted through a self- reflective inquiry (Carr and Kemmis Citation1986; Whitehead Citation1989), to undertake a critical inquiry of my own AL practice. I also engaged in the second person action research through the collaborative inquiry with my co-facilitators to address development and change in the practice of AL facilitation. The third person inquiry in my research relates to Coghlan and Brannick’s (Citation2010, 6) broader definition of third person action research which encompasses ‘creating communities of inquiry, involving people beyond direct second-person action … and dissemination by reporting, publishing and extrapolating from concreate to the general’. I involved the AL members as research participants (as respondents of the focus group, questionnaire and interviews) as part of the AL community of the post graduate programme.

I applied a range of data gathering methods in this research. These included: (1) diary narratives as I maintained a record of personal reflections after the facilitation of each of the four action learning sessions (2) group reflections of the facilitators (including myself) following each AL session (3) programme evaluation participant questionnaires and focus groups as a part of the overall evaluation of the leadership programme which captured their learning from and experience of the action learning process and (4) interview questions which were designed in line with my research questions.

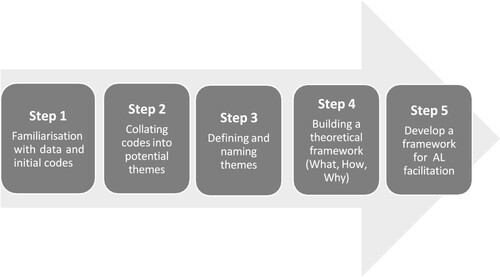

I used thematic analysis to identify, analyse and report patterns (themes) in the data collected through this process (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In establishing what counts as a ‘theme’, I ensured that the themes captured something important about the data in relation to my research inquiry and that it represented some level of patterned responses or meaning within the data set. I have analysed and interpreted the data through a 5-step process, progressing from organising descriptive sets of words to show patterns, to summarise and interpret and finally to theorise the significance of the patterns and their broader meaning and implications (Patton Citation1990; Braun and Clarke Citation2006). A graphic representation of my 5-step data analysis process is shown in .

In Steps 1 & 2, I went through an iterative process of coding and re-coding which enable me to assimilation the data in Step 3 using the three lenses of art, craft and science based on the meaning of pedagogy explored in the literature. I redefined and renamed these three aspects of pedagogy in response to my research context and content. In Step 4, I developed a theoretical framework to further drill into the data to establish relationships between the themes and codes by applying three simple elements: first, ‘why’ facilitate the AL sessions; second ‘what’ the AL facilitators need to do; third, ‘how’ the ALFs enabled the learning and change. In final step of my thematic analysis, using this ‘W’ framework (What, What and HoW), I collapsed and refined the codes to develop a set of ‘constructs’ of each element of this framework which represents my final interpretation and new understanding of the pedagogy of AL facilitation.

Research findings – the art, craft and apparatus of AL facilitation

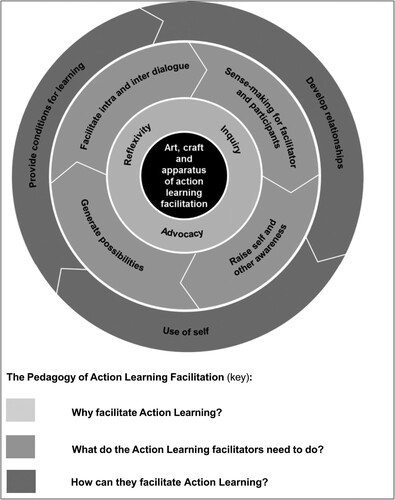

The research findings are viewed specifically through the research lens of the commitment and values that underpin the ALF’s practice (the art of AL facilitation – WHY), the skills and knowledge of the ALF (the craft of AL facilitation – WHAT) and the processes and structures that support AL facilitation (the apparatus i.e. the science of AL facilitation – HOW), presented as follows:

The Art of AL facilitation (‘WHY’): to enable Reflexivity, Inquiry and Advocacy.

The Craft of AL facilitation (‘WHAT’ the facilitators need to do): Facilitating intra and inter dialogue, sense-making for facilitator and participants, raise self and others awareness and generate possibilities.

The Apparatus of AL facilitation (‘HOW’ they can facilitate): Facilitator’s use of self, developing relationships/building trust and provide conditions for learning

The pedagogy of AL facilitation – the art, craft and apparatus of AL

The research offers a framework for pedagogy of AL, presented as the art, craft and apparatus of AL by relating the research findings to a learning process that enables a dialogical relationship between the facilitator of AL and the AL members, enabling learning, change and action. This is presented in .

The ALF enables inquiry, reflexivity and provide advocacy. The attitude of inquiry fostered by the AL facilitator, enhanced learning within the AL set (Cho and Bong Citation2010; Gibson Citation2011; Sofo, Yeo, and Villafañe Citation2010). The AL facilitator should aim to encourage and enable thinking and critical reflection to assist AL members to look at situations from multi-perspectives to define reality by recapturing, noticing and re-evaluating their experience to turn it into learning (Boud, Cohen, and Walker Citation1996; Mezirow Citation1990). This ability of the AL facilitator to enable and encourage reflexivity within the AL set will deepen learning, help the AL members to grasp key issues, make connections and draw relevant conclusions (Brockbank and McGill Citation2003). The AL facilitator may also be required to provide guidance and advice as part of the facilitative role. However, this should not be about telling the AL members what to do, although signposting for further support may be appropriate on some occasions. Rather, it is about ‘gentle guidance’ to prompt and encourage them to express themselves. I have defined this as advocacy, which is a process of supporting and enabling people to express their views and concerns, access information and services, defend and promote their rights and responsibilities and explore choices and options.

Next, to enable inquiry, reflexivity and advocacy within the AL processes, the ALF needs to build capabilities to: facilitate intra and inter dialogue, provide sense-making for facilitator and participants, raise self and others’ awareness and generate possibilities by unlocking individual and group potential. The ALF should be able to encourage dialogue within the AL set (inter) so that diverse assumptions and options may be explored (Hogan Citation2000) through questioning and probing. They can do this by building rapport and ensuring clarity of purpose to fully engage the participants in meaningful conversations. The AL facilitator may also need to simultaneously conduct an internal dialogue (intra) through critical self-reflection by questioning their own assumptions, discrepancies and contradictions in experience (Reynolds Citation1998; Rigg Citation2017) to make appropriate responses and engage others in the conversational space (Lewin Citation1946) with empathy, emotional resilience and self-awareness (Stewart Citation2006).

An effective ALF will make sense of situations presented in the AL set and, at the same time, enable sense making amongst the AL members. Insightful and critical questioning will help the AL members to make meaningful connections between learning and work experience, which, in turn will prompt action (Lawless Citation2008; Pedler Citation2005; Rigg and Trehan Citation2004). Thus, sense making for the facilitator and the participants is an essential ‘craft’ of AL facilitation, enabling AL members’ ‘voices to be heard’ and using the open space for exploring and making sense of issues presented in the AL set. This will generate possibilities and, in many cases, options for action by unlocking both individual and group potential. Another key skill is the ability to raise self and others awareness within the AL set. The AL facilitator must empower the AL members to overcome their own assumptions and be fully alert to others within the AL set, i.e. develop ‘others-awareness’.

The final dimension of the framework relates to how AL facilitation can be most effective, through the use of self, develop relationships and providing the conditions for learning. The ALF’s use of personal ‘self’, including ones’ own personality traits, belief systems, life experiences and cultural heritage (Dewane Citation2006), with genuine commitment and values such as respect and inclusiveness, are essential for AL facilitation. Thus, the ALF’s ability to make use of one’s self and develop relationships by building trust within the AL group are the key factors for effective AL facilitation. An effective facilitator will be caring, empathic, and genuine and show openness and tolerance for ambiguity (Edmonstone Citation2017; Heron Citation1977; Citation1999); this is about creating attunement through emotional sensing and connecting with the AL members. The ALF should aim to ‘hold’ and ‘contain’ emotion laden situations/conversations (Thornton Citation2016), showing understanding of group dynamics (Bion Citation1961). This ‘use of self’ relates closely to creating the conditions under which AL members could learn from each other (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2007). The ALF’s ability to apply structures and processes appropriately, can contribute significantly to providing the conditions for learning. This structuring of processes, procedures and ways of learning is considered to be one of the dimensions in facilitation (Heron Citation1977). At the same time, an effective ALF will demonstrate the ability to be supportive/non-directive, as well as challenging/directive as required, to engage AL members for the purpose of gaining new insights and resolving problems (Dilworth and Willis Citation2003). Thus, ALF’s use of self, ability to develop relationships and create the conditions for learning, by sensitive use of the AL structures and processes, is the apparatus of AL facilitation.

Discussion and conclusion

The empirical evidence for this research confirms the significance of the role of the facilitator of learning within the AL process who may be a ‘coach’, an ‘advisor’, an initiator or accoucheur1; a set facilitator or developer of wider organisational and professional learning in the AL process (Lawless Citation2008; Marquardt et al. Citation2009; Marquardt and Waddill Citation2004; O’Neil and Marsick Citation2007, Citation2014; Pedler and Abbott Citation2013; Pedler Citation2005; Revans Citation1998; Rigg and Trehan Citation2004; Rimanoczy and Turner Citation2008). This research concurs with current literature on action learning that the independent role of a group facilitator accelerates learning, change and actions within an AL set and contradicts Revans’ (Citation1998; Citation2011) concerns that the action learning groups may become over-dependent on facilitators or professional educators, which he felt could hinder the group’s growth. The research findings also reaffirm the work of O’Neil and Marsick (Citation2014) that the facilitation role enables participants to recognise their own assumptions and develop their ability to question their own practice. This assists the AL members to reassess, adjust and create new responses, through questioning and reflection, with support of the AL facilitator.

However, I would argue that the term ‘action learning coach’ (Marquardt and Waddill Citation2004; O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014) or a ‘set advisor’ (Pedler and Abbott Citation2013), which is most commonly seen in the literature, needs to be reviewed to take into consideration the wider context in which AL is now applied, such as organisational leadership development programmes. In this context, the AL facilitation is an independent expert role with high level of self-awareness as well as ‘others-awareness’, in this case the art of being alert to the members of the AL set. The ALF role enables AL set members to develop insight to be able to address complex emotions and consider complex organisational dilemmas (Rigg Citation2006; Vince Citation2004; Citation2008; Vince and Martin Citation1993) to enhance and maximise learning. The role is to acknowledge and recognise such complexities and challenges and make the process easier as a facilitator of learning, rather than just achieving a specific personal or professional goal. It is about enabling the AL members to focus on ‘learning to learn’ (O’Neil and Marsick Citation2014) and ‘think about their thinking’ (Sanyal Citation2018) through questioning and critical reflection. Thus, the role of the facilitator in AL is wider than that of an ‘adviser’ and more encompassing than a one-to-one coach. The in-depth analysis of the research data clearly demonstrates that, although the role the AL facilitator overlaps with that of a coach, to distinguish this role from a coach, specifically a team or group coach, the term ‘action learning facilitator’ is more reflective of the conditions, capabilities and processes the AL facilitator needs to consider for the AL members to learn and take action.

Although the pedagogic model of action learning facilitation presented here is constructed on evidence-based practice of skills, capabilities and processes applied by action learning practitioners, the model offers a holistic point of reference not only for action learning practitioners but facilitators of learning across contexts and sectors. The model can be applied more widely to develop the skills, capabilities, conditions and processes required for effective facilitation of learning and thus contribute to continued professional development for human resource development professionals who facilitate problem-solving groups to learn and take action. It also provides a basis for design of relevant accredited programmes for action learning practitioners. The model can also enable organisations considering action learning as a learning intervention, to identify the purpose and practice of action learning by addressing the Why, What and How of action learning applied in the development of this model. Thus, this model has relevance within the context of management learning both in formal educational programmes and at the same time it can be used in organisations to build capabilities for effective facilitation of individual learning and organisational development.

Acknowledgements

The wholehearted engagement of the programme team and the participants who contributed to this research process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Male midwife – Revans (Citation1998) endorsed initiators or ‘accoucheurs’ to help establish sets

References

- Alexander, R. 2008. “Pedagogy, Curriculum and Culture.” Pedagogy and Practice: Culture and Identities 2: 3–27.

- Anderson, L., and R. Thorpe. 2004. “New Perspectives on Action Learning: Developing Critically.” Journal of European Industrial Training 28 (8/9): 657–668.

- Bion, W. R. 1961. Experiences in Groups and Other Papers. London: Tavistock Publications. [Reprinted London: Routledge, 1989; London: Brunner-Routledge, 2001.]

- Boud, D., R. Cohen, and D. Walker. 1996. “Understanding Learning from Experience.” In Using Experience for Learning, edited by D. Boud, R. Cohen, and D. Walker, 1–17. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

- Boud, D., and D. Walker. 1996. “Barriers to Reflection on Experience.” In Using Experience for Learning, edited by D. Boud, R. Cohen, and D. Walker, 73–87. Buckingham: SHRE and Open University Press.

- Bourner, T., L. Beaty, and P. Frost. 1997. “Participating in Action Learning.” In Action Learning in Practice, edited by M. Pedler, 279–289. Aldershot: Gower.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brockbank, A., and I. McGill. 2003. The Action Learning Handbook: Powerful Techniques for Education, Professional Development and Training. London: Routledge.

- Carr, W., and S. Kemmis. 1986. Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge and Action Research. London: London The Falmer Express. Routledge.

- Casey, D. (2011) David Casey on the Role of the set Advisor. In Pedler, M. (Ed.). Action Learning in Practice (4th ed), Burlington, VT: Gower, pp. 55-70.

- Cho, Y., and H. C. Bong. 2010. “Identifying Balanced Action Learning: Cases of South Korean Practices.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 7 (2): 137–150.

- Coghlan, D., and T. Brannick. 2010. Doing Action Research in Your Organisation. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- de Haan, E., and I. de Ridder. 2006. “Action Learning in Practice: How do Participants Learn?” Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 58 (4): 216–231.

- Dewane, C. J. 2006. “Use of Self: A Primer Revisited.” Clinical Social Work Journal 34 (4): 543–558.

- Dilworth, R. L., and V. J. Willis. 2003. Action Learning: Images and Pathways. Professional Practices in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning Series. Melbourne.: Krieger.

- Edmonstone, J. 2017. Action Learning in Health, Social and Community Care: Principles, Practices and Resources. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

- Gibson, S. H. 2011. How Action-Learning Coaches Foster a Climate Conducive to Learning. Santa Barbara, CA: Fielding Graduate University.

- Heron, J. 1977. Dimensions of Facilitator Style. London: British Postgraduate Medical Federation.

- Heron, J. 1996. Co-operative Inquiry: Research Into the Human Condition. Folkestone, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Heron, J. 1999. The Complete Facilitator's Handbook. London : Kogan Page.

- Heron, J., and P. Reason. 2008. “Extending Epistemology Within a co-Operative Inquiry.” In The Sage Handbook of Action Research, 2nd ed., edited by P. Reason, and H. Bradbury, 366–380. London: Sage.

- Hoe, S. L. 2011. “Action Learning: Reflections of a First-Time Coach.” Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal 25 (3): 12–14.

- Hogan, C. 2000. Facilitating Empowerment: A Handbook for Facilitators, Trainers and Individuals. London: Kogan Page Limited.

- Lamm, S. L. 2000. “The Connection Between Action Reflection Learning and Transformative Learning: An Awakening of Human Qualities in Leadership.” Doctoral Dissertation. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Lawless, E. 2008. “Action Learning as Legitimate Peripheral Participation.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 5 (2): 117–129.

- Leonard, H. S., and F. Lang. 2010. “Leadership Development via Action Learning.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 12: 225–240.

- Lewin, K. 1946. “Action Research and Minority Problems.” Journal of Social Issues 2 (4): 34–46.

- Marquardt, M., and S. Banks. 2010. “Theory to Practice: Action Learning.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 12 (2): 159–162.

- Marquardt, M., H. S. Leonard, A. Freedman, and C. Hill. 2009. Action Learning for Developing Leaders and Organizations: Principles, Strategies, and Cases. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Marquardt, M., and D. Waddill. 2004. “The Power of Learning in Action Learning: A Conceptual Analysis of how the Five Schools of Adult Learning Theories are Incorporated Within the Practices of Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 1 (2): 185–202.

- Marshall, J. 2011. “Images of Changing Practice Through Reflective Action Research.” Journal of Organisational Change Management 24 (2): 244–256.

- Marsick, V. J., and T. E. Maltbia. 2009. “The Transformative Potential of Action Learning Conversations: Developing Critically Reflective Practice Skills.” In Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace and Higher Education, edited by J. Mezirow, and E. W. Taylor, 160–171. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Mezirow, J. 1990. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- O’Neil, J., and V. J. Marsick. 2007. Understanding Action Learning. New York, NY: AMA- COM.

- O’Neil, J., and V. J. Marsick. 2014. “Action Learning Coaching.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 16 (2): 202–221.

- Patton, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Pedler, M. 1991. “Another Look at set Advising.” In Action Learning in Practice. 4th ed. 285–296.

- Pedler, M. 2005. “Critical Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 2: 127–132.

- Pedler, M., and C. Abbott. 2013. Facilitating Action Learning. Maidenhead, Berkshire, United Kingdom: Open University Press.

- Raelin, J. A. 2008. Work-based Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ram, M., and K. Trehan. 2009. “Critical by Design: Enacting Critical Action Learning in a Small Business Context.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 6 (3): 305–318.

- Reason, P., ed. 1988. Human Inquiry in Action: Developments in new Paradigm Research. Folkestone, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Revans, R. W. 1980. Action Learning: New Techniques of Management. 1st ed. London: Blond & Briggs.

- Revans, R. W. 1998. ABC of Action Learning. London: Lemos and Crane.

- Revans, R. 2011. ABC of Action Learning. Aldershot, United Kingdom: Gower.

- Reynolds, M. 1998. “Reflection and Critical Reflection in Management Learning.” Management Learning 29 (2): 183–200.

- Rigg, C. 2006. “Developing Public Service: The Context for Action Learning.” In Action Learning, Leadership and Organizational Development in Public Services, edited by C. Rigg, and S. Richards, 1–11. London: Routledge.

- Rigg, C. 2017. Somatic Learning: Bringing the Body Into Critical Reflection. Management Learning. Folkestone, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Rigg, C., and K. Trehan. 2004. “Reflections on Working with Critical Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 1 (2): 149–165.

- Rimanoczy, I., and E. Turner. 2008. Action Reflection Learning: Solving Real Business Problems by Connecting Learning with Earning. Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

- Sanyal, C. 2018. “Learning, Action and Solutions in Action Learning: Investigation of Facilitation Practice Using the Concept of Living Theories.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 15 (1): 3–17.

- Smith, H., and M. Smith. 2008. The art of Helping Others: Being Around, Being There, Being Wise. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Sofo, F., R. K. Yeo, and J. Villafañe. 2010. “Optimizing the Learning in Action Learning: Reflective Questions, Levels of Learning, and Coaching.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 12 (2): 205–224.

- Stewart, J. A. 2006. “High-performing (and Threshold) Competencies for Group Facilitators.” Journal of Change Management 6 (4): 417–439.

- Teekman, B. 2000. “Exploring Reflective Thinking in Nursing Practice.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 31: 1125–1135.

- Thornton, C. 2016. Group and Team Coaching: The Secret Life of Groups. Oxfordshire, England: Routledge.

- Thornton, K., and P. Yoong. 2011. “The Role of the Blended Action Learning Facilitator: An Enabler of Learning and a Trusted Inquisitor.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 8 (2): 129–146.

- Tsabar, B. 2017. “Educational Work as a “Labor of Love”.” Policy Futures in Education 15 (1): 38–51.

- Vince, R. 2004. “Action Learning and Organisational Learning: Power, Politics, and Emotion in Organisation.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 1: 63–78.

- Vince, R. 2008. “Learning-in-action’ and ‘Learning Inaction’: Advancing the Theory and Practice of Critical Action Learning.” Action Learning: Research and Practice 5 (2): 93–104.

- Vince, R., and L. Martin. 1993. “Inside Action Learning: An Exploration of the Psychology and Politics of the Action Learning Model.” Management Education and Development 24 (3): 205–215.

- Whitehead, J. 1989. “Creating a Living Educational Theory from Questions of the Kind, ‘How do I Improve my Practice?’.” Cambridge Journal of Education 19 (1): 41–52.

- Winnicott, D. W. 1965. The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development. New York: International University Press.

- Winnicott, D. W. 1971. The use of an Object and Relating Through Identification. Playing and Reality. Madison, CT, United States: Psychology Press.