ABSTRACT

Nordic Noir – crime fiction originating in the Nordic region – is one of the most significant international publishing success stories of the twenty-first century. Despite its importance, no one has mapped and analysed the circulation of Nordic Noir as world literature. The present study addresses this knowledge gap by quantitatively mapping the global translation flows of Nordic Noir during the period of its greatest international success, from 2000 to 2020. Drawing on the “Nordic Noir in Translation Database” containing 8,886 translations from all five main Nordic languages – Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish – this study is the first to chart the so-called “boom” in a comparative macro perspective, bringing to light the nuances of its international dissemination and impact. Key findings relate to the chronological structure of the boom, the scale of Swedish dominance and the role of a small group of top authors in driving overall translation rates.

Introduction

Nordic Noir – crime fiction from the Nordic region – is one of the most significant international publishing stories of the twenty-first century. It is often associated with Stieg Larsson’s posthumously published Millennium trilogy (2005–2007), which has morphed into an ongoing franchise with film adaptations and bestselling continuation novels. With global sales in excess of 100 million across all formats, this series ranks among the biggest megasellers of our time. However, whereas J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter, Dan Brown’s Robert Langdon, Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight and E. L. James’s Fifty Shades series are, in a sense, isolated events, the Millennium books form part of a wave of hundreds of books by Nordic crime writers which have experienced success beyond their country of origin. Led by bestselling authors – Jussi Adler-Olsen (Denmark), Leena Lehtolainen (Finland), Arnaldur Indriðason (Iceland), Jo Nesbø (Norway) and Henning Mankell (Sweden), to list only the top author from each country – the Nordic Noir boom is likely the biggest popular publishing phenomenon originating outside the English language, far outstripping, for example, the Latin American literary fiction boom of the 1960s and 1970s.

Despite its importance, no one has mapped and analysed the circulation of Nordic Noir as world literature. Spanning literary criticism, publishing studies and sociology of translation, a significant body of research is available on Nordic Noir as well as on Nordic literature in translation.Footnote1 However, scholarship on the international boom of Nordic Noir in translation is limited by the absence of robust empirical data that enables whole-region comparison. The present study addresses this knowledge gap by quantitatively mapping Nordic Noir as a global translation phenomenon during the period of its greatest international success, 2000–2020. By creating a database of translations from Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish, we aim to chart the “boom” in a comparative macro perspective, bringing to light the nuances of its international dissemination and impact. In doing so, we are guided by two overarching research questions, one descriptive and one analytical:

How has Nordic Noir been disseminated internationally via translation during the period 2000–2020?

How can these translation patterns be understood in terms of a) authorship, b) genre, c) publishing conditions, and d) the position of the Nordic languages within the global system of translation flows?

The “Nordic Noir in Translation Database” (NNTD) serves as the empirical backbone of this article, enabling unique comparative and systematic insights into the international impact of Nordic Noir. It was compiled using several bibliographical sources, methods and approaches. In total, we identified approximately 25,000 first-edition translations of Nordic literature for the period 2000–2020. From this set, we extracted almost 9,000 works of crime fiction (more than a third of the total translations). The resulting database is available as an open-access dataset, making it a resource for further research (Berglund, Gulddal, and King Citation2024).

To gain a more complete picture of the international impact of Nordic Noir, we combine theoretical perspectives from three areas: the sociology of translation, publishing studies, and world crime fiction studies.

Evolving as a field since the early 1990s, the sociology of translation analyses the extra-textual factors that impact translation (Heilbron and Sapiro Citation2007; Sapiro Citation2014). We concur with scholars like Even-Zohar (Citation1990) who see translations as part of a holistic field or polysystem, also including national book markets and the languages themselves, that sets the conditions for different agents working with various aspects of translation. In particular, we draw on the centre-periphery model of languages, first outlined by Johan Heilbron in 1999 and later revised by Heilbron himself and others (e.g. Heilbron and Sapiro Citation2007; Sapiro Citation2010; van Es and Heilbron Citation2015). Extrapolating from patterns identified in UNESCO’s Index translationum (Citation2024), van Es and Heilbron (Citation2015, 297) divide source languages into four categories: the “hyper-central” (English), the “central” (French, German), the “semi-peripheral” (Russian, Spanish, Italian, Swedish) and “peripheral” (all other languages).Footnote2 It is important to note that these categorisations are based solely on the global share of book translations. As such, there is no clear correlation between the number of speakers of a language and the position it occupies in the global field of translation. Further, there is an inverse relation between a language’s centrality in the global field and the level of translations circulating within that language’s national book market(s). This means that source languages with a central position in terms of outbound translations also tend to exhibit a low degree of incoming translations (Heilbron Citation1999; van Es and Heilbron Citation2015). The asymmetrical power relations that shape the flows of translations are crucial to understanding the Nordic Noir phenomenon. The (semi-)peripheral status of the Nordic languages indicates that they import more literary translations than they export. As has been noted previously, the global success of Nordic Noir has partly changed this relationship (e.g. Berglund Citation2017; Citation2022; Hedberg Citation2019; Svedjedal Citation2012). The more precise effects of the boom, however, and the variations between the main five Nordic languages, have not been studied in detail until now.

While the roles of publishers and other book-market agents are already accounted for in the holistic systems analysed by the sociology of translation, a specific publishing studies perspective on crime fiction translations is required if we are to comprehend a book-trade phenomenon like Nordic Noir. In contemporary publishing, bestselling titles are increasingly important, especially for commercially driven genres like crime fiction. The constant search for the “next big thing” creates a highly commercialised culture in which the name of the author is paramount. In crime fiction, this results, for example, in the prevalence of book series, collaborative books marketed under an established name (for example, James Patterson) and continuation novels that extend the success of a deceased author. However, as John Thompson notes (Citation2010, 192–194), it is not only easier to market books by bestselling authors, but also books that trade professionals believe will be successful. For example, in the context of the Nordic Noir boom, the hunt for the “next Stieg Larsson” in the early 2010s significantly boosted international rights sales and, in turn, translations. Accordingly, an investigation of translations flows requires us to factor in the publishing conditions that shape them, for example by analysing the key roles of literary agents, scouts and book fairs as well as the structures and processes surrounding the sale of translation rights (see Berglund Citation2017; Murray Citation2012; Steiner Citation2023). To analyse genres through a publishing lens, moreover, requires us to understand not only the marketing strategies and categorisations used by publishers, but also how these shift over time as genres travel across the globe (Berglund Citation2021).

Finally, the study intersects with the emerging field of “world crime fiction”, which positions the crime genre as constitutively mobile, shaped from its beginnings by translation and transnational exchange (Gulddal and King Citation2022b; Gulddal and King Citation2023; King Citation2014). The world crime fiction paradigm highlights the early internationalism of crime fiction, yet also recognises the process of rapid globalisation over the last few decades that has challenged the twentieth-century dominance of crime fiction in English and created new networks of rights sales, translation, reception and influence. Nordic Noir is a striking example of this process at work: in addition to its high degree of commercial success, it has also become a leading force of innovation in the genre, inspiring attempts to launch other national or regional “noirs” (Tartan Noir, Australian Bush Noir, Mediterranean Noir) and holding stylistic sway over the Anglophone centre of the crime fiction universe, even to the point where English-language authors produce their own Nordic Noir with Nordic protagonists and settings (Gulddal Citation2022). This international impact is anchored in the genre’s specific properties, particularly its formal language, which is both universally recognisable and infinitely adaptable, enabling authors to draw on familiar forms to address political and social issues in highly specific contexts. The interplay between the global and the local that we see in crime fiction ideally positions it for translation, making it a form of literature that can be read and appreciated everywhere.

A key innovation of the study consists of the triangulation of these theoretical perspectives, which, when combined with statistical analysis of the data, present a transformative understanding of Nordic Noir as a singular manifestation of world crime fiction. In addition to demonstrating the scale of the boom and analysing it in terms of longitudinal structure, main authors and main target languages, we offer comparative insights that show that while all Nordic languages have seen significant increases in crime fiction translation rates across the period, Swedish clearly dominates across all metrics. Overall, the data demonstrates that, in the context of crime fiction, the Nordic languages have defied the general logics of the global translation system and achieved a level of centrality that is unprecedented outside the English-speaking world.

Methods and material

The NNTD (theoretically) comprises bibliographic records of all translations of Nordic crime fiction for adults, published during the period 2000–2020. The database and its working definition of what constitutes crime fiction are sourced from dependable bibliographies and book-trade categorisations. The base unit deployed is a “translation event”, which we define as the first published version of a title in another language. We have excluded reprints and republication in different formats because, while these help to measure impact of titles in local book markets, they are less useful for charting the international dissemination of Nordic Noir in translation and thus less reliable as source data. We have also excluded children’s literature. Given that translations of children’s literature constitute a high number of books for the Nordic languages (see Hedberg Citation2019; Svedjedal Citation2012) their inclusion would skew the numbers considerably.

This study aligns with research using bibliographic data to map translation flows. While this is a common approach for studying individual target languages (for example, translations into Swedish) and, to a lesser degree, for individual pairings of source and target languages (say, translations from Swedish into French), comparative studies of multiple source and target languages are rarer, partly because they pose major methodological challenges for data collection and comparability. We address these challenges in two ways. First, we outline the data sources and methods used to collect translation data for each language. Second, we explain the process by which we created the NNTD; this includes our operational definition of crime fiction, the choices made to harmonise the different data sets and the potential issues of comparing translation flows for several languages simultaneously.

The data for Danish literature was extracted from 1) the “Translators Database”, a bibliographic resource maintained by the Danish Arts Foundation (DAF) and covering translations of Danish literature across all genres, and 2) a dataset of international rights sales by Danish publishers and agents in the period 2010–2020, also acquired from the DAF. To identify crime fiction titles, we used a bibliography of original Danish crime fiction 1990–2020 provided by DBC Digital (Citation2022), which offers bibliographic services to Danish public libraries. This resulted in 926 Danish crime fiction titles in translation.

For Finnish literature data is drawn from “Finnish literature in translation”, a database compiled by the CitationFinnish Literature Exchange (FILI) that lists all book-length volumes of Finnish, Finland Swedish and Sami literature in translation. To separate crime fiction translations, we deployed the limitation jännitys- ja rikoskirjallisuus (“thrillers and crime fiction”), which is the genre classification used by Finnish libraries. In total, the database comprises 428 titles of Finnish crime fiction in translation.

The data for Icelandic literature was provided (in the form of a customised extract from the consolidated “Leitir.is” catalogue) by the National and University Library of Iceland (NULI), which has a long-standing policy of purchasing print copies of all translations of Icelandic books; accordingly the data is considered “rather complete and consistent”.Footnote3 The classifications used to identify crime fiction were sakamálasögur (crime stories) and spennusögur (thrillers). The database includes 544 translation events for Icelandic crime fiction.

The bibliographic data for Norwegian literature is drawn from the Norwegian national bibliography – “Nasjonalbibliografien” – as it appears in the digital database Oria which, in theory, includes all Norwegian literature in translation. Crime fiction titles were extracted using the Bibliografi over norsk krim og spenningslitteratur i bokform 1811–2015 (“Bibliography of Norwegian Crime Fiction and Thrillers in Print, 1811–2015”), compiled by Nilsen (Citation2016). For the period 2016–2020, we manually attributed genre, following Nilsen and information from book sales channels. The numbers for Norwegian crime fiction in translation are solid for the whole period, but possibly a bit low for 2016–2020. In total, the database comprises 1,251 titles of Norwegian crime fiction in translation.

The bibliographic data for Swedish fiction in translation is based on LIBRIS, the catalogue of all Swedish academic and research libraries. To identify crime fiction translations, we used Deckarkatalogen (“The Crime Fiction Catalogue”), a cumulative bibliography compiled and published annually since 1977 by the Swedish Crime Fiction Academy (Citation2023). This resulted in 5,737 titles of Swedish crime fiction in translation.

The use of different data sources raises methodological questions that need to be addressed, particularly due to the comparative nature of the study.

First, we acknowledge that quantitative investigations of bibliographic data involve statistical loss, and that this general problem is exacerbated in the translation context because the compilers of national bibliographies rarely prioritise translations. Given that “exact numbers are virtually impossible to produce”, we concur with Yvonne Lindqvist that the data “should be interpreted as indications of tendencies in the global translation field” (2016, 182).

Second, national languages, library systems and book trades all operate differently, which impedes comparison of translation flows. As Heilbron (Citation1999, 432–433) states, the difficulties include definitions (what counts as a “book” or a “title”?) as well as fluctuations in comprehensiveness over time. As Heilbron himself acknowledges, his own major source, the Index Translationum (IT), has significant problems of this kind. For example, other scholars have reported large discrepancies between national book statistics and the numbers in the IT. Further, the IT has not been consistently updated in recent years. This is particularly true for the figures for many smaller countries, which have not been updated since the 1980s or 1990s (Heilbron Citation2000, 13; Svedjedal Citation2012, 34–38).

Because the NNTD draws only on bibliographic information at the national level, which is generally much more reliable than the IT, we are confident that it is as complete as possible. However, the bibliographic entries for the five languages are derived from different kinds of sources. For Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish, the baseline is national library catalogues, including respective national bibliographies. For Danish and Finnish, the baseline is databases compiled by organisations that support literary exchange, foreign-rights sales and translations. While this is not a major problem, the statistical loss is likely to be greater for Danish and Finnish than for the other languages. In particular, the Danish figures for non-crime fiction should be interpreted cautiously.Footnote4

Third, our study focuses on translations of crime fiction written in Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish. Despite a high degree of correspondence, this is not exactly the same as studying translations of crime fiction from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. The most important difference is that crime fiction published in Finland but written in Finland Swedish is not counted as Finnish crime fiction, but as Swedish crime fiction (20 translation events in total). The present article is therefore a study of translations and language flows rather than a study of translations from discrete national book markets.

Fourth, the definition of crime fiction has been operationalised differently across the languages in line with what was practically achievable. For Norwegian and Swedish, the points of departure are carefully compiled crime fiction bibliographies by genre experts. Covering almost all crime fiction published in their respective countries, these bibliographies use an “inclusive” genre definition that encompasses all sub-genres: whodunnits, hardboiled, detective fiction, spy fiction, thrillers, psychological suspense novels, genre-hybrids, and so on.Footnote5 For Danish, Finnish and Icelandic, genre categorisation is based instead on library and book-trade classifications. Yet, despite the agents being different, they offer similar definitions of crime fiction. The broad definition of crime fiction as fiction “focusing on crime”, which is is favoured by crime fiction bibliographers as well as by most crime fiction scholars (e.g. Knight Citation2010, xiii; Scaggs Citation2005, 1), is close to the “umbrella genre” of crime and suspense used in both contemporary book publishing and in libraries (cf. Berglund Citation2021). Given our study concerns translations generally framed abroad as “Nordic Noir” and hence unquestionably considered crime fiction, the problem of different genre categorisation does not materially affect our results.

Finally, we have delimited the database in two significant ways. For Finnish and Swedish, we have only included prose fiction. Since virtually all crime fiction is written in prose, we find that the prose-prose comparison is the most salient one. For Danish, Icelandic and Norwegian, however, both prose and poetry are included as there was no robust means of excluding the latter. The ratio of crime fiction to non-crime fiction for those languages should therefore be seen as low estimates compared to Finnish and Swedish. Further, the NNTD only includes first edition translations published in print book form. Later editions of the same book in the same language (e.g. paperback editions) are not included, nor are ebook or audiobook editions. This delimitation applies to both crime fiction and non-crime fiction. Although digital formats are increasingly important in contemporary book trade, comparing translations of such formats in a reliable way borders on the impossible.

With the above delimitations, our database lists 25,227 translated first editions of Nordic fiction for 2000-2020. Of these, 8,886 (35%) are works of crime fiction (see ) and make up the NNTD, the main empirical source for our analyses. We believe the dataset to be robust for crime fiction and mostly robust for other fiction, the main exception being the number for non-crime fiction in Danish.

Table 1. Composition of the dataset by source language.

Source language

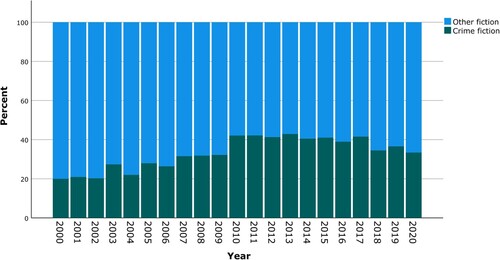

The overall share of crime fiction in the database is 35%, yet this share fluctuates over the period studied. In the early 2000s, crime fiction comprised around 20% of all translations from the Nordic languages. This proportion increased significantly over the decade to more than 40% in 2010, most probably due to the success of Stieg Larsson,Footnote6 and then stabilised at this higher level, with a peak of 42.9% in 2013. The share of crime fiction appears to decline again in 2018–2020, although it still remains high by historical standards (see ).

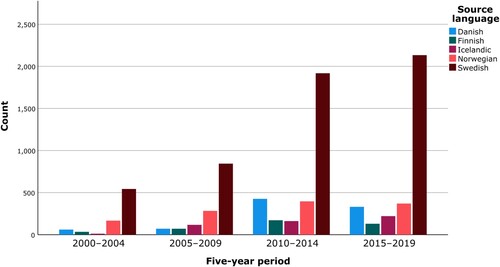

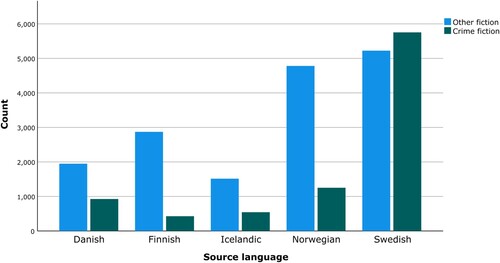

This longitudinal overview of the Nordic Noir boom across the region does not, however, account for the significant differences between the individual source languages. Most strikingly, the dataset demonstrates the vast dominance of Swedish, particularly in crime fiction, where Swedish as a source language accounts for almost two-thirds (65%) of all translations (see ). Although the proportion of crime fiction relative to other genres increases for all Nordic languages during the period studied, the increase in absolute terms is much larger for Swedish; at the peak of the boom, between 2010 and 2019, Swedish consistently produced more than 400 translation events per year, which is more than five times the number for Danish and Norwegian and more than 13 times the number for Finnish (see ). Furthermore, the ratio of crime fiction to non-crime fiction is significantly higher for Swedish than for other Nordic languages. While this ratio in the rest of the region ranges between 13% for Finnish and 32% for Danish, crime fiction accounts for the majority of translations from Swedish – 52% for the whole period (see ). Accordingly, Swedish crime fiction appears to work differently in terms of dissemination and global reach compared to crime fiction from other Nordic countries.

That Swedish is the dominant language of Nordic Noir is not surprising and has been noted by a range of scholars (e.g. Arvas and Nestingen Citation2011, 5–6; Bergman Citation2014, 11; Berglund Citation2021). However, our data shows that the scale of this dominance in the crime fiction context is much more pronounced than previously assumed, with Swedish crime fiction having produced almost twice as many translation events as crime fiction from all the other Nordic languages put together (5,737 versus 3,149).

While Swedish reigns supreme by weight of sheer numbers, we should not forget that other Nordic languages have experienced large increases in crime fiction translation rates over the period, and that these increases are remarkable in their own right. Danish averaged 12.2 translation events per year in the first five-year period (2000–2004), a figure that increased by 443% to an average of 66.2 translation events per year in the last five-year period (2015–2019). For Norwegian, the surge over the same five-year periods is less pronounced, but still significant: from 33.4 to 74.0 translation events per year, corresponding to an increase of 122%.

The growth rates for Finnish and Icelandic are even more remarkable. Crime fiction translations from these two languages were rare in the earliest part of the period. In the year 2000, they produced respectively four and one translation events, while the average per year for the first five-year period (2000–2004) was 6.8 and 2.4 (see ). In the final five-year period (2015–2019), this average had soared to 26.0 for Finnish and a remarkable 44.2 for Icelandic (the latter figure represents an increase of more than 1,700%). While we should not assume a direct correlation between population size and global literary prestige – not least since we build on Heilbron’s sociology of translation – the success of Icelandic crime fiction must be seen in light of Iceland’s population of less than 400,000 people. On a per-capita basis, the translation rate for Icelandic crime fiction in 2015–2019 was almost three times higher than for Swedish crime fiction and more than ten times higher than for Danish crime fiction. These figures show the extent to which Icelandic literature and literary publishing, in an extreme manifestation of a region-wide tendency, have been recalibrated in pursuit of the international opportunities generated by the rise of Nordic Noir.Footnote7

Authors

Mapping the most widely disseminated Nordic crime writers at the author level requires us to consider two metrics: a) the number of translation events per author and b) the number of languages into which each author is translated. The first metric highlights the “depth” of international impact and potentially favours authors with large catalogues, while the second metric measures the “breadth” of impact while obscuring the more or less sustained nature of this impact.

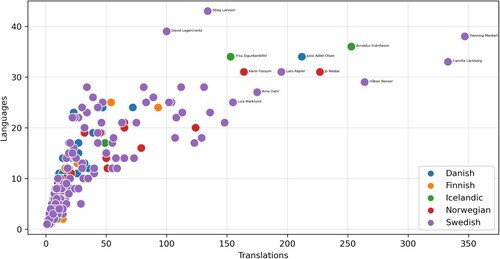

reveals that the most disseminated authors in terms of the overall number of translation events are Henning Mankell (347), Camilla Läckberg (333) and Håkan Nesser (264). These are authors who have long been active and have large crime fiction back catalogues. Mankell’s and Nesser’s place at the top of the list is unsurprising, given they had already begun to be translated on a significant scale during Nordic Noir’s embryonic moment in the late 1990s (see e.g. Arvas and Nestingen Citation2011; Berglund Citation2021, 14–15). The large number of translation events for Läckberg’s books, on the other hand, is slightly more surprising as she made her crime fiction debut in 2003, over a decade after Mankell and Nesser, and, moreover, has written fewer crime novels than both authors, especially Nesser. As the data shows, Läckberg’s Fjällbacka series has been translated into over 30 languages and many book markets offer translations of most or all the volumes – eleven at the time of writing.

Table 2. Top 25 Nordic crime writers by number of translation events.

The most-disseminated authors in terms of number of languages are, unsurprisingly, Stieg Larsson (43), David Lagercrantz (39) and Henning Mankell (38). The international dissemination of the first two authors can be explained by the hype surrounding the Millennium trilogy, which achieved levels of international impact unprecedented in Nordic genre fiction (e.g. Berglund Citation2017; Bergman Citation2014). That Lagercrantz – the author tasked with writing further novels based on the Millennium fictional universe – is in second place, outperforming even Mankell in numbers of languages, is a strong indication of the impact of Stieg Larsson’s books as well as the successful marketing campaign for the continuation novels: of the 43 countries that bought the translation rights and published Larsson’s trilogy, 39 (91%) also bought and published Lagercrantz’s Det som inte dödar oss (2015; English title: The Girl in the Spider’s Web), branded as “Millennium 4”.

As these top-3 lists for most translation events and most target languages make clear, the author level also displays a striking Swedish dominance. If we combine the two metrics and create a subset of authors who have been translated into more than 20 languages and/or have achieved more than 50 overall translation events, the resulting list includes 57 authors: five Danes, two Finns, two Icelanders, seven Norwegians and 41 Swedes. This subset constitutes the most-widely disseminated Nordic crime writers. While making up just 14% of all the authors, they are responsible for two-thirds (66%) of the total number of crime fiction translation events.

If we only consider the very top segment in terms of international impact – crime writers translated into more than 30 languages and/or with more than 150 translation events – the list reduces to 13 authors: one Dane (Jussi Adler-Olsen), two Icelanders (Arnaldur Indriðason and Yrsa Sigurðardóttir), two Norwegians (Jo Nesbø and Karin Fossum) and eight Swedes (Arne Dahl, Lars Kepler, David Lagercrantz, Stieg Larsson, Camilla Läckberg, Henning Mankell, Liza Marklund, and Håkan Nesser) (see ; cf. ). This small subset comprises Nordic crime fiction with a truly global impact.Footnote8

Figure 4. Scatter plot of Nordic crime writers (n = 408) per source language: number of translations and number of languages translated into.

What emerges from these calculations is the following pattern: while there are at least a couple of truly global and/or widely disseminated crime writers from each Nordic language, the number for Swedish is approximately ten times larger. In fact, the number of truly global and/or widely disseminated Swedish crime writers (41) is over 2.5 times that of widely disseminated crime writers from the other Nordic languages taken together (16). Among the non-Swedish authors, Norwegians are the most and Finns the least widely disseminated; there are no Finnish crime writers among the truly global ones. In absolute numbers, Swedish authors dominate all segments of translated Nordic crime fiction. Swedish is dominant both in terms of breadth and depth, but the dominance increases at the top of the distribution. Apart from Icelandic, all other Nordic languages display the opposite tendency (see ).

Table 3. Three subsets of Nordic crime writers divided per source language.

In regard to overall distribution, the top segment of truly global authors represents 3% of all translated authors but just under a third (30%) of the 8,886 translation events in the NNTD. The widely disseminated authors (11% of all authors) represent another third of the translations (36%), while the remaining, less disseminated 86% of the authors have written the final third (34%). This distribution offers insights into the structure of the Nordic Noir boom and, in particular, highlights the importance of the top segment in driving translation rates more broadly. As illustrates, the breakaway success of a few authors is followed by a tail of authors who have achieved international dissemination on a lesser (although, in many cases, still significant) scale.

What the data shows, then, is that global crime fiction bestsellers from semi-peripheral and peripheral languages are crucial to facilitate new international opportunities for other authors in those languages. When a worldwide megaseller like Larsson breaks the “translational glass ceiling” this generates global interest in books from the same region. This, in turn, results in adjustments to book market structures, with authors, agents and publishers repositioning themselves for international dissemination. While we have only investigated the specific translation phenomenon of Nordic Noir, this may constitute a general tendency or rule. At least in the Nordic context, the newly found global interest transcends the crime genre. Following the success of Nordic Noir, Swedish writers of other kinds of popular fiction – like Jonas Jonasson and Fredrik Backman – have acquired very large readerships worldwide. The adaptation of Backman’s bestseller En man som heter Ove (2012) into the American comedy-drama A Man Called Otto (2022), starring among others Tom Hanks, is perhaps the most apparent example.

Target languages

From 2000 to 2020, Nordic crime fiction was translated into 54 languages, with the number of translation events per target language ranging from hundreds for languages such as German (977), Danish (672), Dutch (587) and English (568) to just a single translation event for Belarusian, Sami languages, Gujarati and Kurdish (see ). Of the 28 translation targets with a share of >1% of the database, 26 are major European (as well as, in some instances, global) languages, and the dataset includes a total of 38 languages with European origins. Our data therefore broadly supports the hypothesis of “a European ‘internal market’ for crime fiction”, allowing crime fiction titles “to circulate across the continent with comparative ease” (Gulddal and King Citation2022a, 196). However, the dissemination of Nordic Noir extends well beyond languages originating in Europe. The group of target languages with more than 100 translation events includes Japanese (120), but languages such as Chinese (91), Turkish (85), Korean (83), Hebrew (61), Arabic (32) and Vietnamese (17) also have a significant number of translations.

Table 4. Number of translation events and share of database per target language (and with all languages with a share below 1% collapsed into “Other languages”).

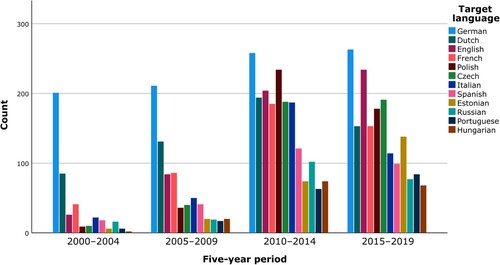

The target languages data confirms the overall longitudinal structure of the Nordic Noir boom. While translations of Nordic crime fiction were rare for most target languages in the 2000s, the number of translation events skyrocketed after 2010 (see ). When comparing 2000–2004 to 2010–2014, the number of English translations rose from 26 to 204, an increase of 686%. A similar tendency is found in French (from 41 to 185, or 351%), Czech (from 10 to 188, or 1,780%) and Italian (from 22 to 187, or 750%). The largest increase occurs in Polish, where the translations grew from 9 to 234 – a remarkable increase of 2,500%.

Figure 5. Translations of Nordic Noir for all target languages with over 2% of the translations in the NNTD and with Nordic languages excluded: count per five-year period, 2000-2019.

The main exception to this pattern is German, which was already a major target language of Nordic – predominantly Swedish – crime fiction in the 2000s (and, to some extent, in the 1990s [Böker Citation2019]). Although we can also identify an increase in German translations around 2010, the growth is much more modest – from 201 translation events in 2000–2004 to 258 ten years later, a 28% increase. Dutch represents a middle ground, having significant numbers of translations during the 2000s compared to all other target languages except Germany, yet still showing high growth after 2010.

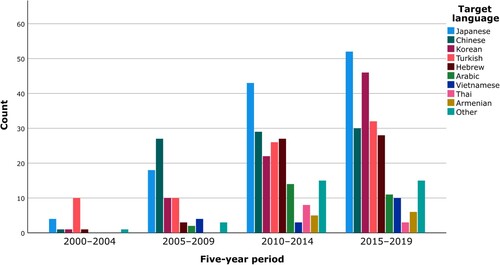

Although the absolute numbers are lower, the target languages originating either outside or (in the case of Turkish and Armenian) at the border of Europe confirm the overall pattern, with most languages showing significantly higher levels of translations in the 2010s (see ).

Figure 6. Translations of Nordic Noir for target languages originating outside or at the borders of Europe (and with languages <10 translation events collapsed): count per five-year period, 2000-2019.

The international impact of Nordic crime fiction therefore has two main phases: first, in the late 1990s and 2000s, the “Schwedenkrimi” became popular in Germany and the Netherlands due to authors such as Henning Mankell and Håkan Nesser and a general interest in Scandinavian and especially Swedish culture. Second, in the late 2000s, Stieg Larsson’s novels were crucial in launching the broader Nordic Noir boom in the Anglophone markets and the rest of the world.

With regard to geographical distribution, the data shows that Nordic crime fiction is widely available in all central and semi-peripheral languages in Heilbron’s model, and also available in significant numbers in several peripheral languages (see ). Unsurprisingly, the major languages of Western Europe, with their mature publishing industries and high levels of inbound translations, are all large markets for Nordic crime fiction; as noted, German is the leading target language with 977 translation events, while English, French, Spanish and Italian account for translations in the range of 387–568. Southeastern Europe and the Balkans are important markets as well, with Hungarian, Bulgarian, Greek and Romanian each having more than 100 translation events. However, what stands out is the fact that the Nordic region’s immediate neighbours all have comparatively high levels of translation, indicating that geographical and cultural proximity is an important driver of translation numbers. It is no surprise to find English, Dutch and German in the top five of non-Nordic target languages, but the volume of translations into Estonian (247), Russian (232) and, particularly, Polish (477) suggests that Nordic Noir has been able to open up markets that have traditionally been accessible to Nordic adult fiction to only a limited degree.

Constituting a special case, translation between the Nordic languages themselves comprises a large part of the dataset, namely 2,170 events (24.4%). While not surprising given the strong historical and cultural bonds between the Nordic countries, our data indicates the emergence of a distinct Nordic Noir translation system that functions semi-independently of the global and English-dominated one. The high flows of outbound and inbound translations between the Nordic languages not only produce significant commercial outcomes but also point to the existence of an important, ongoing dialogue between writers and readers across the region.

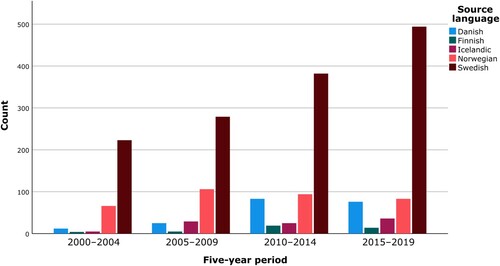

However, the Nordic region as a translation system is defined by pronounced asymmetries, with Swedish again being dominant. In terms of source languages, Swedish accounts for the majority of translation events, consistently exporting more crime fiction to the region than the other Nordic languages combined and even widening the gap between them in absolute terms throughout the period (see ).

Figure 7. Translations of Nordic Noir to Nordic languages: source language count per five-year period.

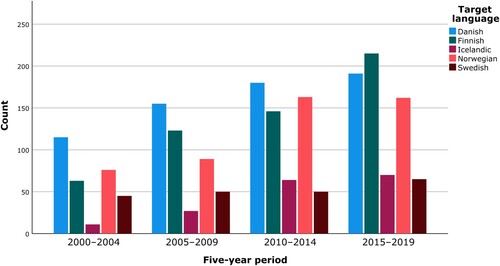

The data on target languages is even more telling. While the number of inbound crime fiction translations shows consistently high growth for the other Nordic languages, essentially following the pattern of outbound translations for these languages, the number for Swedish increases at a much lower rate. Furthermore, there are more inbound translations for Danish, Finnish and Norwegian than for Swedish throughout the period, and during the 2010s, even Iceland – a tiny book market compared to the rest of the region – imported more Nordic crime fiction than Sweden (see ).

Figure 8. Translations of Nordic Noir to Nordic languages: target language count per five-year period.

In her study of translation flows to and from Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, Lindqvist finds further evidence for Heilbron’s centre-periphery model, claiming that there are “strong indications that Swedish literature functions as the centre of this peripheral Scandinavian translation (sub)field” (Lindqvist Citation2016, 184). However, while similarly confirming Heilbron’s model, our data allows us to make an even bolder claim. The inverse relation between outbound and inbound translations, which Heilbron (Citation1999; cf. van Es and Heilbron Citation2015) regards as defining a central position in the world translation system, is clearly manifested here in the sense that Swedish is both the largest source language and the smallest target language in the Nordic region. Accordingly, in the crime fiction context we can describe Swedish as the hyper-central English of the Nordic languages.

This tendency is even clearer when we look at ratios of outbound to inbound translations (). When including all target languages, the only language with a ratio of <1, indicating net import of Nordic Noir, is Finnish, and this number can readily be explained by very high numbers of translations from Swedish and the lowest number of outbound translations in the region. Conversely, the figures for Danish, Norwegian and Icelandic are all greater than 1 and show rising levels of dominance, the numbers for the latter two languages being particularly strong. However, the ratio for Swedish is in a different league, with 26.08 outbound translations for every inbound translation, offering further evidence of the central position occupied by Swedish crime fiction. If considering only translations between the Nordic languages, all languages apart from Swedish have negative outbound-inbound ratios. In this comparison Finnish stands out as the lower extreme. For each Finnish crime novel that gets translated into another Nordic language, over 13 books get translated into Finnish. For Swedish, again, the pattern is the complete opposite. For each Nordic crime novel that gets translated into Swedish, 6.7 books are translated into one of the other Nordic languages.

Table 5. Outbound versus inbound translations for the Nordic languages: count and ratio 2000-2020.

Conclusion

The value of our research consists in providing empirical evidence for the scale, longitudinal development and geographical distribution of Nordic Noir as an international publishing phenomenon in the period 2000–2020. The number of crime fiction translation events in our database (8,886) is a striking indication, not only of the success of Nordic literary agents and publishers in selling translation rights to foreign markets, but also of the demand for Nordic crime fiction among foreign readers. The NNTD shows that while some translation activity was already occurring around 2000, the actual “boom” began around 2006 and plateaued around 2010 at high levels that were sustained over the 2010s, with a small decline towards the end of that decade. Finally, in charting the international distribution of Nordic Noir, we have demonstrated that Nordic Noir has its most important international markets in European languages (including their global extensions), with particularly high translation numbers in the Nordic region itself and countries that border it. Importantly, however, the data also shows substantial numbers of translations into languages such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

A major finding is the level of Swedish dominance. Whether we look at the overall proportion of Swedish crime fiction, the top authors in terms of either target languages or overall translation events, or ratios in outbound versus inbound translations, Swedish is well ahead of the other Nordic languages. This conclusion was expected, but the absolute and relative figures are nevertheless astounding, demonstrating how Swedish literary agents and publishers have been able to leverage the impact of authors such as Henning Mankell, Camilla Läckberg and Stieg Larsson to achieve broad-based international success on an unparalleled scale. However, recognising the enormity of the Swedish numbers comes with the risk of underestimating the success of crime fiction translated from the other Nordic languages. For “peripheral” languages, the crime fiction translation numbers for Danish, Finnish, Icelandic and Norwegian are still significant, both in absolute terms and relative to overall translations from those languages and to the size of population. As an international publishing phenomenon, Nordic Noir is disproportionately Swedish, yet the 3,149 translation events coming out of the other Nordic countries would be sufficient to qualify as a “boom” in their own right.

Our data shows that a handful of internationally successful Nordic authors have been crucial in generating translations for a large group of crime writers. In particular, Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy appears to have been pivotal in either initiating or intensifying the international success of Nordic Noir. The fact that the rapid increase in translation events – first for Swedish, later for other Nordic languages – happens shortly after the original publication of Larsson’s novels in 2005–2007 is a strong indication of Larsson’s role. This case is further supported by the fact that the 2009 peak in Larsson translations happens shortly before the 2010–2013 peak in overall Nordic Noir translations. However, translation numbers were already high, particularly for Swedish, prior to the publication of the Millennium trilogy, and while Larsson’s books are clearly a very significant factor, they are not the only driver of the Nordic Noir boom.

Our study has demonstrated the importance of individual authors paving the way for other authors and, indeed, whole languages. Nevertheless, a fuller understanding of Nordic Noir as an international publishing phenomenon requires that translation data be combined with an analysis of the institutional structures and marketing practices that have supported rights sales on this scale. Two lines of enquiry seem particularly promising.

First, the role of translation subsidies needs to be better understood. All Nordic countries have well-funded literary exchange programmes, yet the policy settings vary and appear to benefit crime fiction to different degrees. For example, the CitationFinnish Literature Exchange, as documented by their database of translations, provided financial support for 171 crime fiction translations in the period 2000–2020; this number represents a remarkable 40% of all crime fiction translation events, and top-tier authors such as Lena Lehtolainen and Antti Tuomainen each received support for multiple books, even after their international breakthrough. Conversely, the Danish Arts Foundation prioritises “publications that are to a lesser degree expected to be able to manage themselves financially” and “projects and applicants who have not previously […] received support”;Footnote9 accordingly, few Danish crime fiction authors have received translation subventions. Such differences may, to some extent, account for the varying levels of international impact achieved by crime fiction in different Nordic languages.

Second, the role played by literary agents in the success of Swedish crime fiction has already been noted by scholars (Berglund Citation2017). However, our database offers a new, evidence-backed approach to this question. For example, the Stockholm-based Salomonsson Agency currently represents 12 of the top-25 Nordic Noir authors, and they account for an astonishing 1,841 (21%) of the total number of translation events in the NNTD.Footnote10 Similarly, albeit on a lesser scale, Politiken Literary Agency, the leading agency for Danish crime fiction, represents 431 translation events or close to half of all crime fiction translations from Danish (46.5%). Thompson notes that “if you have the systems in place to exploit rights effectively in the international arena then you can generate substantial additional revenue streams both for the author and the agency” (Citation2010, 69). Our data enables an evaluation of such systems across the region, including how scale and specialisation can result in very significant rights sale outcomes.

The data from the NNTD also allows us to further understand crime fiction as a form of world literature. It provides evidence that Nordic Noir is the third great translation phenomenon in the history of world crime fiction; the first two being the worldwide circulation of, primarily, British classic detective fiction from the late nineteenth- and the early twentieth-centuries, and American “hardboiled” crime fiction, particularly after WWII. The fact that this third wave originates outside the two centres of classic Western crime fiction, in “semi-peripheral” or “peripheral” languages, and extends its geographical spread, not only to European and Western countries, but also to places such as India, China, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam, has important consequences for our understanding of world crime fiction. For one thing, it speaks to a decentring of the crime fiction universe, wherein new centres emerge and challenge the traditional supremacy of Anglophone authors. Second, it confirms one of the core tenets of world crime fiction theory, namely that contemporary world crime fiction is defined by its use of internationally recognisable literary forms that facilitate global dissemination, despite the localised settings, plots and socio-cultural contexts of individual crime novels (Gulddal and King Citation2023, 290–292). If the snow, the dark pine forests and the Nordic social model are “exotic” elements to readers outside the region, the formal repertoire of Nordic Noir is deeply familiar and offers a narrative framing that helps bridge cultural distances.

Crime fiction scholars have identified “a need for data-driven research at the global level” to understand more fully the genre’s worldwide reach (Gulddal and King Citation2022b, 21). Our study is a significant first step in this direction and provides a potential model for future research into the translation and circulation of other national, regional or continent-wide crime fiction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Simone Murray, Jana Rüegg, and Johan Svedjedal for their valuable feedback on the manuscript, and Laurits Stapput Knudsen for assistance with the editing and formatting of the Danish data. We also acknowledge the bibliographic support we received from Ylva Sommerland (National Library of Sweden), Laura Kaalund-Jørgensen and Jeppe Naur Jensen (Danish Arts Foundation), and Ragna Steinarsdóttir (National and University Library of Iceland).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data on which this study is based, “Nordic Noir in Translation Database”, has been peer reviewed and made publicly available by the Post45 Data Collective at https://data.post45.org/the-nordic-noir-in-translation-database-2000-2020/. See Berglund, Gulddal, and King (Citation2024).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karl Berglund

Karl Berglund is Assistant Professor of Literature at Uppsala University, Sweden. He has engaged mainly in computational methods for large-scale research on book and reading culture in general as well as specifically for Swedish crime fiction. He has published three books in Swedish, and articles in e.g. PMLA, LOGOS, Cultural Analytics, and European Journal of Cultural Studies. His most recent publication is Reading Audio Readers: Book Consumption in the Streaming Age (2024).

Jesper Gulddal

Jesper Gulddal is Professor of Literary Studies at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He has published books and articles on anti-Americanism in European literature, mobility and movement control in the modern novel as well as on crime fiction. His research has appeared in leading journals such as New Literary History, Comparative Literature, Comparative Literature Studies, Symploke, Textual Practice and others. Recent publications on crime fiction include the co-edited volumes Criminal Moves. Modes of Mobility in Crime Fiction (2019), The Routledge Companion to Crime Fiction (2020) and The Cambridge Companion to World Crime Fiction (2022).

Stewart King

Stewart King FAHA is Associate Professor of European Languages at Monash University, Australia, and an elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities. He has written books and articles on cultural identities in contemporary Catalan- and Castilian-language narrative from Catalonia, crime fiction from Spain and world crime fiction. His most recent publications are the monograph Murder in the Multinational State (2019) and the co-edited collections Criminal Moves: Modes of Mobility in Crime Fiction (2019), The Routledge Companion to Crime Fiction (2020) and The Cambridge Companion to World Crime Fiction (2022).

Notes

1 While the present study is the first to offer a comparative, data-backed analysis, there is now a growing literature on the Nordic Noir boom in a translation context. Johan Svedjedal’s survey “Swedish Literature as World Literature” (Citation2012, especially 47–62) provides a good historical overview of the translation flows for Swedish fiction, including the importance of the Nordic Noir wave (cf. Hedberg Citation2019). Other studies focus on specific target languages, for Scandinavian literature, including crime fiction, notably English, German, and French (Broomé Citation2015; Böker Citation2019; Hedberg Citation2022; Edfeldt et al. Citation2022). A further group of studies discusses specific translational aspects of Nordic Noir, for example the role of book covers (Broomé Citation2015; Nilsson Citation2017), literary agents (Berglund Citation2017) and interventions in the translated texts themselves (Berglund and Allison Citation2024).

2 The “semi-peripheral” category is the most unstable one in Heilbron’s scheme. The classifications here differ slightly from the ones used in Heilbron Citation1999, where he takes a longer historical perspective; the most important difference in the present context is that Danish has been moved down from “semi-peripheral” to the “peripheral languages” category. Moreover, van Es and Heilbron Citation2015 somewhat inconsistently speak of “semi-peripheral” and “semi-central” languages as synonymous. In this article, we use the more established term, “semi-peripheral”, to refer to this middle group of languages.

3 Email correspondence with the NULI Acquisitions and Metadata team (30 August 2022).

4 This is because data on rights sales was not available for the period 2000–2009. The main implication of this data gap is that we are unable to calculate accurately the overall market share of crime fiction within Danish literature in translation.

5 For a detailed discussion on the crime fiction criteria used for the Swedish bibliography “Deckarkatalogen,” see Berglund Citation2012, 13–17.

6 Another factor is the international popularity of Nordic TV crime dramas, such as Unit One (4 series, 2000–2004), The Killing (3 series, 2007–2012), The Bridge (4 series, 2011–2018), among others.

7 Another explanation for the strong Icelandic figures is the invitation extended to Iceland to be “Guest of Honour” at the 2011 Frankfurt Book Fair. As Elisabeth Böker notes, this status involved “a substantial promotional programme and translation fund provided by the Icelandic project team ‘Sagenhaftes Island’ (Fabulous Iceland) and financial support of the Icelandic government” (Böker Citation2019, 586).

8 These groupings have been made at the level of specific author constellations, meaning, for example, that Roslund & Hellström (112 translation events), Roslund & Thunberg (39) and Roslund writing alone (19) are treated as three different authors. If counted as one author, the number of translation events for all “Roslund constellations” would increase to 170.

9 Danish Arts Foundation (Citation2023), “Literary Production and Translation,” https://www.kunst.dk/english/funding-programmes/literary-production-and-translation (accessed 10 May 2023).

10 Salomonsson Agency (Citation2023), “Authors,” https://www.salomonssonagency.se/authors/ (accessed 10 May 2023).

References

- Arvas, Paula, and Andrew Nestingen. 2011. “Introduction: Contemporary Scandinavian Crime Fiction.” In Scandinavian Crime Fiction, edited by Paula Arvas and Andrew Nestingen, 1–20. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Berglund, Karl. 2012. Deckarboomen under lupp: Statistiska perspektiv på svensk kriminallitteratur 1977-2010. Uppsala: Uppsala University. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-184976.

- Berglund, Karl. 2017. “With a Global Market in Mind: Agents, Authors, and the Dissemination of Contemporary Crime Fiction.” In Crime Fiction as World Literature, edited by Louise Nilsson, David Damrosch and Theo D’Haen, 77–90. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Berglund, Karl. 2021. “Genres at Work: A Holistic Approach to Genres in Publishing.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 24 (3): 757–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211006097.

- Berglund, Karl. 2022. “Crime Fiction and the International Publishing Industry.” In The Cambridge Companion to World Crime Fiction, edited by Jesper Gulddal, Stewart King and Alistair Rolls, 25–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berglund, Karl, and Sarah Allison. 2024. “Larsson, Remade: A Computational Perspective on the Millennium Trilogy in English.” PMLA 139 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1632/S0030812923001207.

- Berglund, Karl, Jesper Gulddal, and Stewart King. 2024. “The Nordic Noir in Translation Database.” The Post45 Data Collective. https://doi.org/10.18737/CNJV1733p4520240201.

- Bergman, Kerstin. 2014. Swedish Crime Fiction: The Making of Nordic Noir. Milan: Mimesis International.

- Böker, Elisabeth. 2019. “The Incredible Success Story of Scandinavian Best Sellers on the German Book Market.” Scandinavian Studies 91 (4): 582–582. https://doi.org/10.3368/sca.91.4.0582.

- Broomé, Agnes. 2015. “Swedish Literature on the British Market 1998–2013: A Systemic Approach.” (Unpublished thesis). Department of Scandinavian Studies, UCL.

- Danish Arts Foundation. 2023. “Literary Production and Translation.” https://www.kunst.dk/english/funding-programmes/literary-production-and-translation. Accessed 10 May, 2023.

- DBC Digital. 2022. “Bibliografi over dansksproget kriminallitteratur udgivet i Danmark i perioden 1990–2021” [unpublished bibliography].

- Edfeldt, Chatarina, Erik Falk, Andreas Hedberg, Yvonne Lindqvist, Cecilia Schwartz, and Paul Tenngart. 2022. Northern Crossings: Translation, Circulation, and the Literary Semi-Periphery. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- van Es, Nicky, and Johan Heilbron. 2015. “Fiction from the Periphery: How Dutch Writers Enter the Field of English-language Literature.” Cultural Sociology 9 (3): 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975515576940.

- Even-Zohar, Itamar. 1990. “The Position of Translated Literature within the Literary Polysystem.” Poetics Today 11 (1): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772668.

- Finnish Literature Exchange. 2024. “Finnish Literature in Translation”. http://dbgw.finlit.fi/kaannokset/index.php?lang = ENG. Accessed 13 February 2024.

- Gulddal, Jesper. 2022. “The Foreignizing Crime Novel: Anatomy of a Publishing Phenomenon.” Genre 55 (1): 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1215/00166928-9720894.

- Gulddal, Jesper, and Stewart King. 2022a. “European Crime Fiction.” In The Cambridge Companion to World Crime Fiction, edited by Jesper Gulddal, Stewart King and Alistair Rolls, 196–220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gulddal, Jesper, and Stewart King. 2022b. “What Is World Crime Fiction?” In The Cambridge Companion to World Crime Fiction, edited by Jesper Gulddal, Stewart King and Alistair Rolls, 1–24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gulddal, Jesper, and Stewart King. 2023. “World Crime Fiction.” In The Routledge Companion to World Literature, edited by Theo D’haen, David Damrosch and Djelal Kadir, 285–293. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hedberg, Andreas. 2019. Svensk litteraturs spridning i världen. Stockholm: Svenska Förläggareföreningen.

- Hedberg, Andreas. 2022. Ord från norr: Svensk skönlitteratur på den franska bokmarknaden efter 1945. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.

- Heilbron, Johan. 1999. “Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World-system.” European Journal of Social Theory 2 (4): 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/136843199002004002.

- Heilbron, Johan. 2000. “Translation as a Cultural World System.” Perspectives 8 (1): 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2000.9961369

- Heilbron, Johan, and Gisèle Sapiro. 2007. “Outline for a Sociology of Translation: Current Issues and Future Prospects.” In Constructing a Sociology of Translation, edited by Michaela Wolf and Alexandra Fukari, 93–107. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- King, Stewart. 2014. “Crime Fiction as World Literature.” Clues 32 (2): 8–19.

- Knight, Stephen. 2010. Crime Fiction since 1800: Detection, Death, Diversity. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury.

- Lindqvist, Yvonne. 2016. “The Scandinavian Literary Translation Field from a Global Point of View: A Peripheral (Sub)field?” In Institutions of World Literature: Writing, Translation, Markets, edited by Stefan Helgeson and Pieter Vermeulen, 174–190. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Murray, Simone. 2012. The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nilsen, Ole-Mikal. 2016. Bibliografi over norsk krim og spenningslitteratur i bokform 1811–2015 [unpublished bibliography].

- Nilsson, Louise. 2017. “Covering Crime Fiction: Merging the Local into Cosmopolitan Mediascapes.” In Crime Fiction as World Literature, edited by Louise Nilsson, David Damrosch, and Theo D'haen, 109–130. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Salomonsson Agency. 2023. “Authors.” https://www.salomonssonagency.se/authors/. Accessed 10 May, 2023.

- Sapiro, Giséle. 2010. “Globalization and Cultural Diversity in the Book Market: The Case of Literary Translations in the US and in France.” Poetics 38 (4): 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.001.

- Sapiro, Giséle. 2014. “The Sociology of Translation: A New Research Domain.” In A Companion to Translation Studies, edited by Sandra Bermann, and Catherine Porter, 82–94. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Scaggs, John. 2005. Crime Fiction. London: Routledge.

- Steiner, Ann. 2023. “World Literature and the Book Market.” In The Routledge Companion to World Literature, edited by Theo D’haen, David Damrosch and Djelal Kadir, 259–266. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Svedjedal, Johan. 2012. “Svensk litteratur som världslitteratur: Litteratursociologiska problem och perspektiv.” In Svensk litteratur som världslitteratur, edited by Johan Svedjedal, 9–82. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press.

- Swedish Crime Fiction Academy. 2023. Deckarkatalogen. https://www.deckarakademin.se/deckarkatalogen/. Accessed 15 March, 2023.

- Thompson, John B. 2010. Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Polity.

- UNESCO Culture Section. 2024. “Index Translationum”. https://www.unesco.org/xtrans/bsform.aspx. Accessed 13 February 2024.