ABSTRACT

The Indonesian government maintains a security approach to dealing with the armed conflict in West Papua. However, the state’s securitization results in more harm, evidenced by the increasing number of armed attacks in its Central Highlands. Why has the securitization failed to quell the conflict in West Papua? How and why does Indonesia’s government securitize the conflict? This article uses securitization theory to show three strategies the Indonesian government uses to address the conflict and how the government excludes Papuans. It further argues that examining the Papuan resistance is critical to elucidate the ineffectiveness of this securitization. It concludes that securitization must be deliberative in achieving security outcomes, and those would only prolong rather than halt the conflict if only relying on powerful actors.

Since West Papua became part of IndonesiaFootnote1 in 1969 through the rigged Act of Free Choice,Footnote2 the area has remained a significant problem for Indonesia’s government. The separatist conflict, which has involved violent and nonviolent campaigns in Indonesia’s troubled easternmost region, has been ongoing for almost 60 years, with no end in sight. Since 1965, armed groups, such as the West Papua National Liberation Army – Free Papua Movement—Tentara Pembebasan Nasional Papua Barat (TPNPB)–Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM) – have waged a war against the sophisticated Indonesian security forces (Tentara Nasional Indonesia, TNI, and police), seeking independence from Indonesia.Footnote3 In response, Indonesian governments launched military operations in West Papua from 1969 to 2000.

Following the downfall of Suharto’s authoritarian rule in 1998, the Indonesian government introduced a 2001 Special Autonomy Law—Otonomi Khusus (Otsus) – to deal with insurgency in West Papua. Otsus at least officially, acknowledges the needs, interests, aspirations, and fundamental rights of indigenous Papuans. However, as Papuans’ protests made clear in 2005, 2010, and 2019, such recognitions have barely been met.Footnote4 Instead, the central government still maintains a security approach to deal with the separatist conflict in West Papua. Nevertheless, such a heavy-handed approach has failed to terminate the decades-long armed conflict that has escalated in the past few years.

Since late 2018, violence in the Central Highlands of West Papua – chiefly in Nduga, Timika, Puncak, Intan Jaya, Yahukimo and Pegunungan Bintang – has caused serious concern. The conflicts have forced thousands of indigenous Papuans to seek refuge both across West Papua and in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Residents, particularly women and children, in the affected areas have not been able to get proper access to education and health services since those areas have been closely overseen by security forces.Footnote5 During an anti-racism protest in 2019, Papuans raised serious concerns about how the state deals with pressing problems in West Papua. In 2020 and 2021, the armed conflict escalated in highland areas, claiming the lives of many civilians and soldiers, including one high-ranking special force general who was also head of provincial intelligence.

Why have the state’s securitization moves failed to halt the armed conflict in West Papua? How and why does the central government securitize insurgency as an existential threat? This article seeks to answer these questions by focusing on Papuans’ marginalized status within the Indonesian nation, a factor which is overlooked in the securitization moves. It builds upon the International Relations (IR) subdiscipline of security studies,Footnote6 namely securitization theory, both from the Copenhagen School and the Paris School, to examine how the state has securitized the Papuan conflict, yet disregarded a marginalized group that is strongly affected by security practices. The article then demonstrates that marginalized audience engagement is a critical stage in achieving security outcomes. Using the empirical case of Papua’s armed conflict, the article will explain how securitization moves – framing the Papuan conflict as a significant threat and implementing security policies in Papua – operate and how they fail to suppress insurgency or manage armed groups led by local governments and residents. In its securitization moves, the Indonesian central government has disregarded continued protests and disagreements of local leaders, civil society groups, and indigenous people in Papua. Papuans have been overlooked in the securitization moves because of both their racial difference and their lack of political influence, particularly in terms of not having been able to form a national coalition to terminate the armed conflict. However, their consent to securitization moves would support the success of such moves in West Papua.

The present article first outlines how the study was conducted. Second, it outlines a theoretical discourse of the securitization process and the effect of overlooking the indigenous status of those affected by the implementation of securitization, including the Papuan people. Third, it highlights how Southeast Asian countries securitize identity differences in the Philippines, Thailand, and Myanmar. Fourth, the article highlights the history and contemporary status of armed conflict in the Central Highlands of West Papua. Fourth, it describes how the central government securitizes the conflict in West Papua. Finally, it discusses why the state’s securitization has received a strong reaction from Papuans and failed to end the armed conflict in West Papua.

Method

The author conducted 10 months of intensive fieldwork in West Papua, combining various data collection techniques. The primary method was direct and indirect interviews and participant observation while the author spent three months as a volunteer assisting internally displaced Nduga persons (IDPs) in Wamena, the capital of the Jayawijaya region. He interviewed 78 displaced Nduga residents, who included teachers, human rights activists, local government officers, other volunteers, and even some TPNPB fighters. The author also interviewed local priests and humanitarian workers who assisted the conflict-affected people in Intan Jaya. The secondary method involved compiling civil society, media, and government reports, including official reports on the number of soldiers deployed to West Papua from 2019 to 2021. The author also compiled reports on armed attacks in the Central Highlands of West Papua since 2019. Combining various sources from fieldwork and documented evidence is helpful for explaining the dynamic of conflict in a highly restricted area where there are both security concerns and constrained access to media.

Securitization without Marginalized Audience Engagement

The second part of this article highlights two schools of securitization theory – the Copenhagen School and the Paris School – and how the theory applies to dealing with a marginalized audience in a political conflict. The article examines the perspective of the indigenous Papuans, and the importance of this perspective in relation to securitization theory. The Indonesian securitization approach aims to address the political conflict in West Papua. Shifting a political issue of independence solely to the security realm requires a shared perception and consensus between the securitizing actors and audience. Relatively few studies have focused on the framing of insurgency as an existential threat without considering either the intersubjective relations between the securitizing actors and the audience, particularly marginalized groups, or the framing of the security practices’ success. Political elites tend to focus on the interests of a particular type of audience and overlook others in securitization moves. The case of the armed conflict in West Papua offers additional lenses for constructing a specific issue as a national security problem through securitization moves.

Emerging from critical security studies, the Copenhagen School and the Paris School hold the view that there are no objective threats. Threats are socially constructed through a political rather than analytical decision.Footnote7 While both schools agree on how threats are constructed, they differ in the role of audience in securitization moves to eradicate menaces.

The Copenhagen School has pioneered the use of the securitization theory to rhetorically frame issues as an existential threat requiring extraordinary measures or policies.Footnote8 This theory is not a guide for when to securitize a specific issue, but rather underpins analysis of the prevailing circumstances, process, and outcomes of securitization of that issue and of the politics of struggle over securitization speech acts and practices.Footnote9 The classical Copenhagen School positions the speech act or rhetoric as the most crucial aspect of securitization. When securitizing actors, using repetitive discourses, frame a specific issue as a (potential) menace against the referent object, existential policies are adopted to respond to the threat.Footnote10 The threat is constructed performatively, mainly through speech acts. In this regard, speaking the discourse of security empowers securitizing actors to adopt specific policies for the referent object’s survival.Footnote11 The elites undertake securitization moves to frame issues as a national menace and therefore require relevant security actors to design and implement crucial policies to mitigate or eradicate the threat.

Securitization is self-referential, meaning a threat is not an objective reality but is presented as such by the political elites. This empowers them to adopt certain policies.Footnote12 Through rhetoric, political elites frame the issue as a threat that requires extraordinary policies beyond the normal political process. Thus, the focus of securitization is not identification and classification by the securitizing actors, since there are no objective threats, but how the actors label and frame specific issues as existential threats and what extraordinary policies must then be adopted.Footnote13

Such a classical understanding of securitization as a discourse-centric analysis has garnered various critiques, one of which stems from the Paris School, another offshoot of critical security studies. Like the Copenhagen School, the Paris School also defines the threat not as an objective condition but as socially constructed.Footnote14 However, in contrast to the discourse-based Copenhagen School that relies chiefly on the active role of political elites within a specific context to construct a threat, the Paris School emphasizes the acceptance or consideration of the audience.

The classical Copenhagen School takes account of the audience, who are relegated to a minimal role in the construction of issues as (perceived) threats.Footnote15 The securitizing actors or elites have formal authority which empowers them to make decisions relatively unconstrainedFootnote16 regarding existential threats and exceptional policies. However, the Paris School sees the influential audience – those who can give significant support – as a critical element to determining how securitization operates in dealing with a threat. The audience’s interpretation of a specific context can lead them to accept, protest against, agree or disagree with, question, or challenge securitization moves.Footnote17 Effective securitization acts require not only a securitization move but, most importantly, a level of acceptance by the audience.Footnote18 The audience’s acceptance is not taken for granted since it requires a two-way process. In this sense, securitization is about a call and a response. The elites have to frame the securitization move in certain ways and the audience has to accept it.Footnote19 Without the audience’s acceptance, securitization will be ineffective.Footnote20 The Paris School emphasizes intersubjectivity between the elites and the audience in the creation of specific issues as matters of security.Footnote21 In this regard, having audience consent legitimizes the process of securitization.

While the author agrees with the Paris School’s emphasis on the intersubjectivity process inherent in the audience’s active role,Footnote22 this article extends the notion of audience engagement to the type of audience that is highly affected by securitization moves, both in terms of rhetorical framing and actions, to determine the effectiveness in mitigating or eradicating public menaces. According to the Paris school, audience will reject securitization if they do not see it as constructing a specific issue as a public threat requiring extraordinary policies. The term “audience” is not confined to the general public, nor to the majority population, but can also be applied to a specific group with different capacities to attain security objectives. The marginalized audience can be a determinant of the effectiveness of securitization moves. Thus, the type of audience is important since different audience have different symbols, capacities, contexts, race, and cultures.Footnote23 Audience possess different influences that affect different security outcomes.Footnote24 CoteFootnote25 contends that audience are those group(s) that can authorize the perspective of the issue(s) put forward by the securitizing actors and legitimize the issue(s) through acceptance of security policies. This argument only applies to groups with political leverage related to securitization and the securitizing actors. Yet, securitization is also about acceptance not only by those who can either grant access to measures or tolerate the security actors’ actions,Footnote26 but also by those who experience the effect of security practices. In reality, marginalized individuals, groups, and communities directly affected by securitization moves are largely and intentionally overlooked. Such sidelined groups are hardly part of a securitizing process, nor can they even raise an issue about the securitization agenda.Footnote27 Nevertheless, having policy-affected marginalized audience consent will result in the legitimacy of the securitizing process and its implementation. The absence of a shared security perception and meaning among the affected population will cause resistance toward securitization moves and failure to eradicate threats.

This article uses Papuans an empirical case of a marginalized group. As Barter argues, autonomous indigenous peoples, such as Papuans, perceive themselves as nations, racially and religiously distinct and with their own territory and government, often with histories of self-rule.Footnote28 Papuans are a declining majority in their region, which most do not see as part of Indonesia. The Indonesian government would need to consult with indigenous Papuans regarding specific policies implemented in West Papua, where most indigenous people are concentrated, for this group to see themselves as part of the state. If marginalized groups who experience harmful securitizing effects are not involved in securitization, then the state will find it hard to achieve its security objectives. The more harm faced by marginalized groups, the more likely they will be to resist securitization moves that prolong their grievances.

Unsurprisingly, as mentioned earlier, Papuans tend to be overlooked in the Indonesian securitizing process and practices because of their racial difference and lack of political influence by comparison to other ethnic groups in Indonesia. They are disengaged from the state’s securitization as they do not possess influential political benefits for national stabilityFootnote29 In some Southeast Asian Countries, the securitizing actors even construct marginalized or minority groups as posing threats to the state.

Securitization of Identity Differences in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is home to minority identities who historically and contemporarily experience constrained relationships with the state. In its troubled regions, the governments’ inability to manage identity differences causes deep-seated grievances and discontent. Recently, some countries in the region still control and dominate the peripheral regions with distinct ethnic minorities. These ethnic minorities have claimed unique identities that are different from others in the state. They also present various political demands, such as autonomy, power division from the state, and even independence, to defend their identities.Footnote30 However, some Southeast Asian governments in the Philippines, Thailand and Myanmar frame those differences as a challenge, and even a threat, to their national unity and integrity.

During the nation-building process, many Southeast Asian nations reified the colonial binary vision of ethnic groups through discriminatory, racial and injustice policies, which led to various violent and nonviolent mobilizations. After gaining independence in 1947, the Philippines government reified the former colonial American land and resettlement policies that encouraged Christian settlers from the northern Philippines and private corporations to dominate Muslim-predominated areas in Mindanao.Footnote31 Following the British ethnic exclusion and assimilation policies in Malaysia, the Thailand government initiated cultural assimilation policies in 1950 that targeted its Muslim population. The government also demanded that the Muslim population remain loyal to the Buddhist king while imposing various intolerance policies in Thailand’s southern provinces; that is, Patani, Narathiwat and Yala, where Islam has been a predominant religion since the fifteenth century.Footnote32 These policies included restricted Malay language, religious education, traditions, and other customs. In Myanmar, the government had merely recognized some ethnic groups while excluding others, which became a source of cleavage, political mobilization and claim making. The state recognition of 135 identities (taingyinthar) with an indigenous status has granted those groups political and economic access.Footnote33 The Myanmar government tied taingyinthar with citizenship to differentiate them from migrants, such as the Rohingya people. In 1974, the Myanmar government imposed a citizenship policy for the Rohingya – they were categorized as foreign citizens carrying registered cards to distinguish them from native citizens.Footnote34 In all three countries, the states barely provide institutionalized protection to ethnic minority claim-makings to preserve and protect their identities and areas.

Those discriminatory policies created a fertile ground for the emergence of ethnic-religious nationalism in the Philippines, Thailand, and Myanmar. From the 1950s to the early 2020s, BRN (the National Revolutionary Front), under the banner of Islamic nationalists, became the most prominent insurgent group to launch armed and terrorist attacks, to respond to the state domination and discriminatory policies in deep-south Thailand. In the late 1960s, major insurgent groups, such as the Moro National Liberation Front, emerged to defend the local identity and respond to the state’s harsh measures to succumb to Moro’s identity. The Myanmar government’s systematized effort to disregard the Rohingya led to the rise of religious nationalist groups, such as the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation and Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, to use nonviolent mobilization or take arms to respond to the state’s discriminatory policies.Footnote35 Minority demands and interests for independence and autonomy are subject to long-held perceptions of threats to the state’s sovereignty in these three countries.

The securitization of ethnic claim-makings in these countries begins with authoritative and influential voices using historical and contemporary narratives and a psychology of fear within which threats are framed.Footnote36 It also requires extra-political actions to address the threats. The elites use historical anonymities that connotate minority groups, such as Bangsamoro, Patani and Rohingya, as a threat, harm, or challenge to the state’s integrity, self-rule, or dominant ethnic groups. Along with past grievances, Thailand, the Philippines, and Myanmar governments have used the global narratives to persecute minority groups in ‘troubled regions.” The successive Philippine governments, including Rodrigo Duterte’s administration, have used the “war against terrorism and drugs”Footnote37 policies and their detrimental effects to undermine democratic values as a pretext to employ hard-line policies in Mindanao. Similarly, Thaksin Shinawatra politicized drug trafficking to use an all-out-war approach to deal with religious nationalist discontent in deep-south Thailand.Footnote38 The Myanmar government and Buddhist extremist groups connotate the violent response of the Rohingya’s insurgent groups as an act of terror that sanitizes the state’s genocidal actions toward Muslim Rohingya.Footnote39

The elite’s speech acts, such as from politicians, military, and conservative civil society groups, are necessary to create public beliefs and perceptions, influence consciousness and construct a way of thinking that the state is under existential threat, thereby needing emergency actions to address it.Footnote40 On the one hand, the rhetoric has barely received significant opposition, which translated into passive acceptance of majority ethnic and religious groups to employ security measures to deal with distinct minority groups who either advocate for succession, state recognition or autonomy. In Southeast Asia states with minority problems, the elite’s rhetorical discourses target specific audiences, such as the Burmese majority group in Myanmar, the Christian majority in the Philippines, and Thai Buddhists, to support the governments’ heavy-handed approach.

On the other hand, ethnic minorities who mobilize people to protest the state’s harsh measures toward their identity are barely included in the securitization process. Existential threats or dangers are politically and socially framed through the elite’s rhetoric rather than becoming deliberative engagements with other relevant actors, particularly marginalized groups who are affected by security measures. The national elites believe any regional discontent is best dealt with through security measures, such as martial laws, military operations, and more security bases and posts, with a lack of local input. Consequently, this heavy-handed approach leads to more counteractions from ethnoreligious-based insurgent groups. Eventually, one can say that the securitization process and practices without local consent and involvement merely prolong the conflicts in Thailand, the Philippines and Myanmar.

In the same vein, the Indonesia’s government has systematically portrayed Papuans’ political rights as a source of instability.Footnote41 Through rhetoric, Indonesian securitizing actors merely focus on galvanizing support from the majority population to construct the armed conflict in West Papua as an existential threat and consequently employ security policies to safeguard national integrity. Audience engagement thus applies only to an influential audience, namely the dominant ethnic groups in Indonesia. Papuans, the group, directly affected by security policies, have suffered a long period of systematic racism and discrimination, and lack electoral significance and are powerless to respond to a discriminatory process of securitization of the insurgency in their land. Unable to react to the state’s securitization, Papuans simply have to accept the security regulations, which involve the installation of a new military unit, the massive deployment of soldiers and the imposition of terrorist labeling on pro-independence groups.

Despite the Papuans’ inability to generate formal support to enable or disable security actions, they are the key to legitimizing and determining the desired security outcome. Papuans’ perception of whether securitization is legitimate is crucial to their accepting and obeying the authorities.Footnote42 The main expected outcome of securitization in West Papua is the prohibition of political activities and armed campaigns considered a menace to the state. However, in the past three years, indigenous Papuans have been resistant to a security approach, which is seen as halting their political aspiration to independence. Papuans have barely complied with security policies imposed by the state’s securitizing actors. Continuous protests, disagreements, and mobilization to challenge the legitimacy of security policies are pervasive in West Papua. Their refusal to co-operate with securitizing actors has led to the inability of securitization moves to terminate the violent political conflict. In the securitization lens, Papuan dissidence is considered a threat; thus, the state sees protestors as rebels, which amplifies the conflict.

Armed Conflict in West Papua

The third aspect of this study is the historical and contemporary status of West Papuan resistance to the Indonesia’s securitization practices. The OPM started to attack the Indonesian military as early as June 1965, and proclaimed independence in July 1971.Footnote43 Although Papuan separatists have lacked internal cohesion, the struggle has endured. In response, the TNI initiated military operations in highland areas of West Papua in 1969. The TNI launched the Bharatayudha, Wibawa, Pamungkas, Koteka, Kikis, and Senyum operations located in Wamena, Nduga, Yahukimo, Puncak, Intan Jaya, Paniai, and Mimika. Such operations have induced generational trauma and grievances for indigenous people that have fueled more armed resistance over the years.

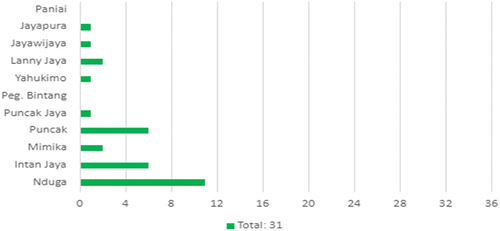

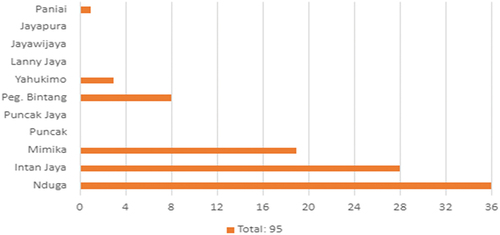

In the past fives years, the Central Highlands of West Papua have experienced regular gunfights and ambushes between the TPNPB and the Indonesian security forces. Sixteen key TPNPB commands, mostly active in several Central Highland regencies (kabupaten), have presented severe attacks on the state (see ). Since 2018, 10 commands have been in gunfights with the Indonesian armed forces. The commands in the two regencies of Nduga and Intan Jaya in particular have carried out the most armed attacks against the Indonesian military and police (see ). It should be noted that support for the TPNPB has come, first, in the supply of more sophisticated weapons, from illegal trade with the military and police, confiscation, and illicit supplies from Bougainville, PNG, Thailand, and the Philippines.Footnote44 Second, the armed groups have increasingly received financial support, such as from village funds.Footnote45 Third, despite an old ethnic schism,Footnote46 some factions of the TPNPB have joined forces to launch gunfights against the TNI.

Table 1. Key TPNPB military commands.

Nduga’s bitter experience with the Indonesian military began in 1977. Through the so-called Operasi Kikis (Chipping Away), the TNI hunted down any dissident who challenged the authority of Indonesia, chiefly in the Central Highlands of West Papua.Footnote51 Although it is difficult to estimate the number of human casualties from the operation in this region, Neles Tebay (2012), an indigenous scholar, estimates that thousands of people diedFootnote52 over this period. In 1996, the people of Nduga again experienced further brutality from the Indonesian military. Against the backdrop of rescuing 24 researchers kidnapped by the OPM, the Indonesian military, led by Brigadier General Prabowo Subianto,Footnote53 launched a massive counterinsurgency operation that claimed hundreds of civilian lives.Footnote54 Since Nduga became a new regency in 2008, people started to develop the area with very few armed or social conflicts. However, developmental projects turned out to be a source of discontent in Nduga.

The Trans-Papua Highway project – which has involved scant indigenous consultation or participation and will facilitate non-indigenous migration to the territory and increase agribusinesses’ access to West Papua’s natural resources – has generated deep resentment among Papuans who are being dispossessed of their land. In late November 2018, the TPNPB, led by local commander Egianus Kogeya, killed 16 out of 24 construction workers in Yigi district, which sparked continued attacks against the Indonesian security forces at the time of writing.Footnote55

The TPNPB also increased its presence in Intan Jaya as another battlefield against the Indonesian security force outside the Nduga and Timika regencies (see ). In October 2019, the TPNPB shot to death three motorcycle taxi drivers.Footnote56

In late December 2019, the TPNB killed two soldiers from the special force command (Kopassus), which has a reputation for egregious human rights abuses. The killing paved the way for the soldiers to patrol in search of the TPNPB across two districts, Sugapa and Hitadipa. The military started to keep the residents and their houses under surveillance to gather more information regarding the whereabouts of the guerrilla fighters.Footnote57 Violence peaked on September 19, 2020, when two soldiers shot and tortured Reverend Yeremia Zanambani, a respected religious leader. After the death of Rev. Zanambani, the military maintained its presence to hunt down the rebels. In addition, the civil society coalition reportedFootnote58 that violence in Intan Jaya was also related to the business interests of the American mining company Freeport-McMoran, national politicians, and state-owned enterprises. Accordingly, the military and the police had to secure the mining site in the area (Wabu Block). As a result, between December 17, 2019, and November 6, 2020, 17 violent cases claimed the lives of 12 civilians and 5 soldiers.Footnote59 Since then, the two opposing sides (i.e., the Indonesian security forces and the TPNPB) have committed egregious violence against one another and civilians. This has generated hundreds of IDPs from Intan Jaya residents fleeing to neighboring areas such as Nabire, Timika, and Deiyai.

Securitization Moves in West Papua

Since the escalation of the above-mentioned armed conflict in highland areas, particularly in Nduga and Intan Jaya, the central government has reinforced a heavy-handed approach in response. Securitization began with strong rhetoric from national elites. President Joko Widodo instructedFootnote60 the military to hunt down the TPNPB without considering potential wrongdoing by the state and its security forces. The speaker of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) also supported firmer measures to deal with the TPNPBFootnote61:

I demand that the government deploy the security forces at full force to exterminate the armed criminal groups (KKB) in Papua which has taken lives. Just eradicate them. Let’s talk about human rights later.

The TPNPB cannot rival the TNI in logistics, resources or military training and operates in very remote areas. As a result, the former has not been able to inflict large or lasting damage on the latter. However, the political elites’ rhetoric has portrayed the armed group as an existential menace for state survival, regardless of reported indiscriminate violence committed by state security forces. Such rhetoric reflects the general perception among the majority of Indonesians of the TPNPB as a “disturbance” of the state’s good intention to develop West Papua.

Following the speech acts of national leaders, the military has doubled its presence in the area. The state’s securitization moves in West Papua have relied on a one-sided process in which the central government commissions the military, in tandem with the police, to hunt down the TPNPB. There is no public deliberation on the legitimacy of force mobilization, particularly from the national parliament, as stated in the TNI Law No. 34/2004. The state’s securitization of the Papuan conflict employs three practical policies that are detailed below: the formation of a multi-service command, the increased deployment of soldiers to reduce the (perceived) threat, and terrorist labeling.

New Military Command in West Papua

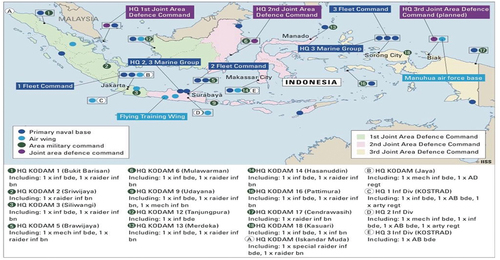

In September 2019, the TNI established Kogabwilhan consisting of army, air force, and navy units, to respond to internal and external threats. This joint command was a long-awaited military plan to transform the TNI into a modern defense force. Kogabwilhan has two primary functions. First, it is the main strike force and early response system to deal with internal threats, such as separatism, armed conflict, and even terrorist attacks.Footnote62 Second, it is a deterrent force for external threats, such as disputes with neighboring countries. Kogabwilhan has its presence in three national strategic areas: Kogabwilhan I in Sumatra, Kogabwilhan II in Kalimantan, and Kogabwilhan III in West Papua (see ). Kogabwilhan has been a critical element of Indonesia’s military transformation to achieve its medium-term strategic plan, Minimum Essential Force 2024. Kogabwilhan III supports new strategic commands in eastern parts of Indonesia, but not exclusively, in West Papua, such as the 3rd Army Strategic Force (Kostrad) Infantry Division located in Gowa, South Sulawesi; the 3rd Marine Group in Sorong, West Papua; the 3rd Fleet Command in Sorong, West Papua; and the 3rd Air Force Base in Biak, West Papua (see ). The new commands will require posting more soldiers in the designated areas.

Map 1. Key Military Units and Locations.

Continued violence in West Papua provides a pretext for Kogabwilhan to justify its relevance. Since West Papua is considered a strategic defense area and an active insurgency has operated in the area for almost 60 years, Kogabwilhan is a significant extension of Indonesia’s military power within West Papua. Kogabwilhan III authorizes and oversees military operations other than war in West PapuaFootnote64 and, if necessary, would coordinate the ground mobilization of soldiers to conduct counterinsurgency operations in West Papua. This substantial authority has strengthened Kogabwilhan III’s independent operational role compared to that of regional commands (Kodam XVII/Cendrawasih and Kodam XVIII/Kasuari), which deal with territorial and administrative matters in West Papua.

The conflicts in Nduga and Intan Jaya demonstrate how Kogabwilhan III has been a prominent operational command for launching strikes against the TPNPB. Since the 2019 armed attacks, Kogabwilhan has been a first responder in gunfights with the TPNPB.Footnote65

Massive Deployment of Soldiers

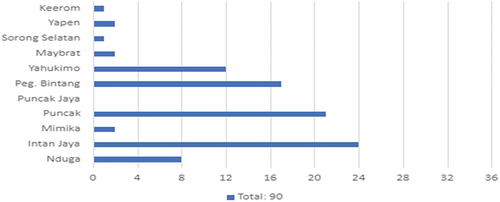

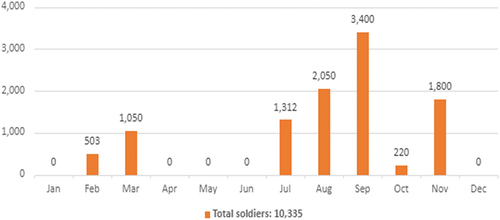

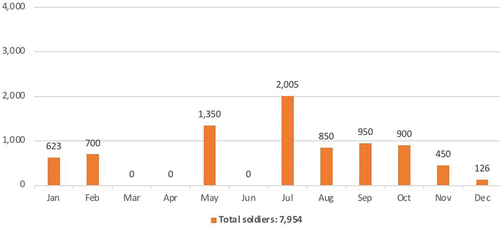

The second security policy mentioned above involves increasing the number of soldiers from other Indonesian islands brought in to deal with the insurgency in West Papua. Since 2019 to 2021, 30247 soldiers have been deployed in West Papua (see ). The main characteristic of the deployment is the display of military power rather than institutional capacity (see ). The soldiers are there to respond to armed conflicts, secure the borders, and protect national strategic objectives, such as those of the American mining firm Freeport-McMoRan in Mimika and British Petroleum’s Tangguh in Bintuni Bay, West Papua.

Table 2. Characteristics of Military Deployment in West Papua 2019–2021.

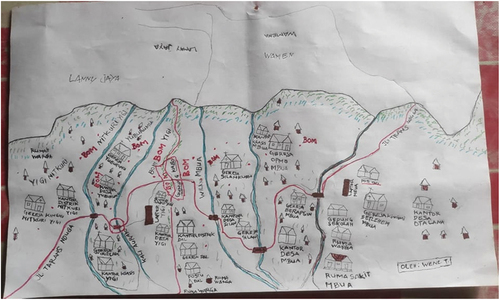

Although Kogabwilhan III is the highest joint defense command, the army is the dominant combat unit responding to the armed conflicts in Nduga and Intan Jaya. From late 2018 to 2020, the TPNPB’s guerrilla assaults in the two areas received strong retaliation from the army.Footnote70 The killings of 16 construction workers were met with a harsh response from the Indonesian security forces, which, on December 4, 2018, launched an initial counterinsurgency operation deploying up to 1,000 military and police officersFootnote71 in Nitkuri, Yigi, Dal, and Mbua in Nduga (see ). Such an operation has uprooted thousands of IDPs to seek refuge across West Papua.Footnote72 In October 2020, the army deployed 900 soldiers to reinforce the two battalions already operating in Intan Jaya since August 2019 to counter the TPNPB, which intensified its attacks there. The army also turned two schools into temporary military posts in the Sugapa district in Intan Jaya.Footnote73

Map 2. Aerial Bombs in Nduga 2019.

Key

The TNI has increased its deployment of army raiders to become the backbone of operations in the highlands. In the past three years, 14712 raider infantry soldiers have been deployed in the Central Highlands. The raiders were the first battalions to pursue the TPNPB command in Nduga and Intan Jaya in early and late 2019. Given terrain difficulties, such as mountains and jungles at high altitudes and with cold environments, Nduga and Intan Jaya present extreme challenges to hunting down TPNPB fighters, but the raider battalions are suited to such constraints. They are skilled in counterterrorism, counter-guerrilla tactics, and long battles. They also have airborne capacity suitable for highlands. The involvement of such strategic army forces reflects the high intensity of the battle in Nduga and Intan Jaya.

The existence of Kogabwilhan III and the military deployment are part of the securitization moves that influence the perception of most Indonesians. Media information related to gunfights and ambushes between the security force and the TPNPB in highland West Papua feeds the Indonesian citizenry as the primary audience to support the duty of the military without considering the experience of indigenous Papuans. Civil society groups have reported that security practices have claimed and wounded civilians.Footnote75 However, securitizing actors, such as the military, the police, and the defense ministry, have been persistent in continuing securitization policies in West Papua.Footnote76 The securitizing actors have constructed a shared security perception and actions which garner legitimacy among the majority Indonesian (non-Papuan) population. Kogabwilhan III – with its authority to conduct military operations and support massive military deployment – has created a strong perception that a Papuan political aspiration is a security realm that threatens national integrity. Thus, any firm actions employed by the Indonesian security force are unavoidable to save the nation – despite their coming at the expense of Papuan interests.

Framing the TPNPB as Terrorists

The third security policy follows a general approach adopted by the Indonesian government, which has been to label nationalist groups as terrorists. In 1976, a year after Indonesia invaded East Timor, the central government deemed the Fretilin a terrorist group. In 2005, the central government also labeled the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM) as a terrorist group, without any deliberation regarding this designation.Footnote77 It did not take long before Jakarta imposed another such labeling – on West Papua’s independence groups as terrorists.

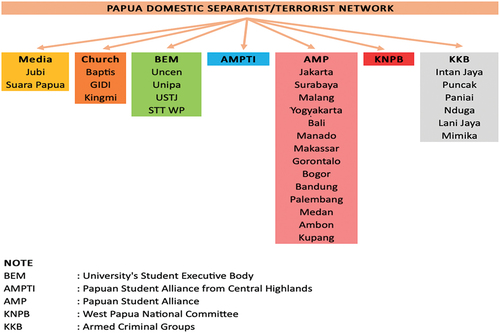

Although public discourse emerged in 2019, a defining moment for intensive discussion about labeling the TPNPB as a terrorist group emerged in 2021. Some Indonesian parliamentariansFootnote78 prompted authorities to create a formal regulation classifying the TPNPB as a new terrorist group in Indonesia. In response, the Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) held a series of meetings to classify the TPNPB and its affiliatesFootnote79 as terrorist groups. The central government has also labeled civil society groups advocating and supporting self-determination, such as student organizations and churches, as belonging to terrorist networks (see ).

The main objective of this framing is to reduce violence in West Papua, particularly in the Central Highlands. The BNPT used several endeavors to label the TPNPB. First, the BNPT has examined old court decisions related to criminal actions conducted by Papuan nationalist figures. The counterterrorism agency believed the court decisions were insufficient to deal with separatist figuresFootnote80 and argued that the treason charges, according to the criminal code law (KUHP), were also inadequate to eradicate the Papuan insurgency groups. The BNPT wanted stronger charges, arguing the political motivation of the TPNPB fit into the terrorism Law No. 5/2018. Such motivation could be considered sufficient to promote and conduct terrorist acts.Footnote81

The second BNPT endeavor was to invite relevant security stakeholders – such as the national intelligence agency, the military, the police and the coordinating ministry for politics, legal, and political affairs – to discuss terrorist labeling of the TPNPB and its affiliates. The agency also invited but later canceled discussionsFootnote83 with civil society groups, researchers, and the National Commission of Human Rights (Komnas Ham).

The Indonesian government’s latest security move to prolong the conflict in West Papua – labeling the pro-independence groups as terrorists – has followed in the footsteps of other authoritarian governments, such as Turkey with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Philippines with the Moro Islamic insurgency. Without going through a judicial process of terrorist labeling and involving civil society groups, as mandated by Law No. 5/2018 on Anti-Terrorism, the Indonesian government declared the TPNPB and other pro-independence groups terrorists. The government merely issued a government decree to legitimize its security policy to deal with Papuan political aspiration. The security practice of terrorist labeling has amplified the government’s reluctance to deal peacefully, such as through dialogue, to terminate the conflict.

Discussion: State’s Securitization and Resistance in West Papua

Securitization theory, following the Paris School, has focused mainly on influential audience constructing specific issues as security threats without engaging with policy-affected marginalized groups. There has, to date, been little attention to marginalized audience engagement in securitization moves. Nevertheless, the marginalized group directly affected by security policies can determine the success of such policies in achieving national security objectives. The research conducted for this article and detailed above indicates that securitization moves in West Papua have overlooked indigenous consent, in contrast to the rhetoric of the national elites and the acceptance of this rhetoric by majority Indonesians. Disengaging Papuans has resulted in the ineffectiveness of securitization moves in terminating the long-running conflict in the region.

Since Papuans are racially different and make up less than 1% of the Indonesian population,Footnote84 they possess less power and influence in the deliberation of the securitizing process and practices. As an indigenous group, Papuans, with their racial, ethnic, and historical differences, appear unfamiliar to many Indonesians. The Melanesian roots of indigenous Papuans are not especially compatible with the Malay-based culture embedded in Indonesian communities.Footnote85 The state has subjugated Papuans’ Melanesian identity by suppressing it as a vehicle for political mobilization and cultural expression. Since 1969, Papuans have been the object of structural racism and discriminationFootnote86 in Indonesian academic, bureaucratic, social, economic, and political life.

In August and September 2019, thousands of Papuans took to the streets to launch the biggest anti-racism protest of the past 20 years. Members of mass organizations and several soldiers in the Indonesian cities of Malang and Surabaya chanted a racial slur, “Papuans are monkeys”, aimed at Papuan youth and students. This incident sparked massive peaceful demonstrations that then turned violent across West Papua. Two crucial demands chanted during demonstrations were that the armed conflict be resolved, and that West Papua be de-militarized. The police arrested hundreds of Papuans, including seven prominent Papuan activists for whom the government sought prison sentences of up to 17 years. They were sentenced to less than a year in prison,Footnote87 primarily due to the international spotlight on the case, which came at a time of a global groundswell of support for the “Black Lives Matter” protests, and domestic pressure.

Papuans have never been part of a national coalition shaping national politics, compared to groups, such as the military, police, bureaucracy, oligarchs, Islamic groups, and political parties.Footnote88 Although Papuans gave most of their votes to President Joko Widodo in the last two elections, they are a lesser group when influencing the national government or major political parties to make more concessions to nationalist groups or to stop the armed conflict. Indonesia’s electoral system distributes votes proportionally to its populations to form a majority. Accordingly, the 2.3 million Papuans who, as stated above, amount to less than 1% of the overall population,Footnote89 are unable to be strongly represented in the executive or legislative bodies. Papuan ministers and members of the national parliament cannot form a national coalition to review the securitization moves underpinned by the most significant political parties in Indonesia, all of which share a unified ideology on dealing with regional rebellions regardless of differing party outlooks. These parties include the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, to which President Widodo belongs), the Party of Functional Groups (Golkar), the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) Party, and the Democratic Party as well as Islamist parties, such as the National Mandate Party (PAN), the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and the National Awakening Party (PKB).

The central government portrays Papuans with their aspiration to political independence as a troubling society which disrupts national integrity and challenges the state’s territorial claims.Footnote90 The national securitizing actors impose a one-way securitization to reduce the threat of this aspiration, which Papuans, in turn, interpret as a deliberate effort to ignore their identity in Indonesia. There has been no engagement to construct a shared security perception and meaning between national securitizing actors and audience in West Papua, resulting in continuous protests, disagreements, and conflicts. Security policies that Jakarta-based elites have imposed have faced skepticism, if not strong resistance.

The major military deployment in West Papua indicates that securitizing practices have increased in the past three years. As noted above, the presence of Kogabwilhan III, with its primary duty to launch strikes on the TPNPB, has merely amplified the military’s domination for handling nationalist armed conflicts. Papuans’ strong resistance toward massive military deployment has fallen short of raising the agenda of desecuritization. The national securitizing actors prefer to keep deploying thousands of soldiers without considering local perceptions and acceptance. Both provincial and national parliamentarians from West Papua have expressed their concerns regarding the brutality of non-Papuan soldiers toward indigenous Papuans. Local civil society groups have asked for more transparency regarding the deployment of these soldiers and the trauma experienced by indigenous people in Nduga and Intan Jaya from the massive military presence.Footnote91 Such concerns have received no response from the central government.

The extra military deployment also generates more grievances for the indigenous Papuans who suffer from soldiers’ misconduct, which takes the form of torture, arrests, and even killings. The local regent of Nduga even met and told President Widodo to withdraw the military from Nduga, since it has created more trauma for the residents of Nduga.Footnote92 Local religious leaders also asked for a reduction of the huge number of soldiers in Intan Jaya. However, the President preferred the generals’ advice to keep the military in the area.

Naming armed groups and other groups aspiring to the independence of West Papua “terrorists” underlines the fact that one-sided securitization further alienates indigenous Papuans. The terrorist labeling related to nationalist conflicts in Aceh, East Timor, and now West Papua, aims to depoliticize the political movements. It also legitimizes the state’s security approach or state-perpetrated violence under the framework of diminishing the “threat of terrorism” which could cause the country to disintegrate.Footnote93 Such an ill-designed policy has received strong resistance from Papuans, ranging from local political elites to grassroots organizations. Papuan Governor Lukas Enembe has stated his concern about the labeling and asked the central government to review it.Footnote94 The Papuan People’s Assembly (MRP) have raised the same concern about labeling that could result in more trauma and resistance toward Indonesia.Footnote95 Non-governmental organizations and churchesFootnote96 in West Papua have also strongly rejected the terrorist labeling. Such labeling merely exacerbates Indonesian security misconduct toward Papuans’ nonviolent political activities.

Despite the sustained protests and disagreement of Papuans, the national securitizing actors continue to securitize the Papuan conflict, with Papuans barely engaged in the production and outcomes of securitization. The chief audience that authorizes and legitimizes securitizing practices in West Papua is non-Papuan, mostly living in the big islands of Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi. The perception of majority Indonesians that authorization of extraordinary measures to deal with the conflict is appropriate is not in line with the interests of Papuans who experience the effect of security policies in West Papua. In 2017, an online surveyFootnote97 found that only 19.4% of non-Papuans (both living in and outside West Papua), compared to 40.77% of Papuans were extremely worried about security conditions in the area. The economy and poverty were the most concerning problems for non-Papuans, whereas Papuans prioritized human rights, security, and independence issues in West Papua. In addition, through media campaigns, such as in newspapers and on television,Footnote98 the national securitizing actors have secured considerable support from majority Indonesians to crush the separatist movement in West Papua.

However, it is not the Indonesian majority ethnic groups, but the marginalized Papuans directly affected by securitization moves who determine the success of such moves. The expected outcome of securitization in West Papua is three-fold: namely, that Papuans accept securitization moves, that there is no further armed conflict, and that Papuans no longer aspire to self-determination. Nevertheless, in the past three years, the escalation of violent armed conflicts has found no end, with forced displacement of thousands of indigenous Papuans. It is worth noting that, during this period, more active armed conflicts have spread across the Central Highlands and more Indonesian security forces have died during the conflict. The securitization in West Papua has so far been unable to achieve its goals of “crushing” the “rebels” and safeguarding the area, by convincing locals to “work together” and to control the armed groups with minimal government assistance and to develop West Papua as “an integral part of the Unitary State of Indonesia”.Footnote99

Displaced Papuans have refused to support the military deployment in Nduga and Intan Jaya. The displaced Nduga people have rejected returning to Nduga as long as the Indonesian security force remains in the area. Some locals have even joined the TPNPB and taken up arms against the TNI. The people of Intan Jaya have refused to share information with the TNI regarding the TPNPB’s whereabouts. Despite living in precarious conditions, displaced persons have accepted only basic supplies distributed by local civil society groups, not the supplies distributed by the military. Local residents, Papuan youth, and student organizations have continuously resisted the new military posts built near the Wabu mining area in Intan Jaya.

In conclusion, audience engagement is crucial to showing that securitization is deliberative to mitigate or eradicate public threats. Yet, it is not only the national elites and powerful audience whose engagement can achieve desired security objectives; most importantly, marginalized groups affected by securitization moves also need to be engaged. Securitization in West Papua reflects the failure in accommodating the indigenous Papuans to address the political conflict in West Papua. The state’s securitization has been mainly focused on the use of military force to achieve the Indonesian state’s interests and has barely attended to indigenous audience engagement to win the hearts and minds of Papuans affected by this approach. As a result, the establishment of Kogabwilhan III, the deployment of extra security forces, and terrorist labeling have not been able to pacify local resistance toward the state. The cases of state’s securitization in West Papua and other troubled areas in Southeast Asia reflect the central government’s use of the political conflict to construct it as an existential threat, without considering the rights of the marginalized people or their political grievances. Marginalized audience engagement is missing from the state’s securitization in the region. The disengagement of the indigenous audience has only intensified, rather than de-escalated, the conflict in West Papua, deep south Thailand, the Philippines’ Mindanao, and Myanmar’s Rakhine state.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank George Lawson, Shane Barter, Nicolas Lemay-Hebert and both reviewers for their thoughtful comments towards improving the earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hipolitus Ringgi Wangge

Hipolitus Ringgi Wangge, is a researcher and sessional academic in School of Culture, History, Language, College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University. His interests include nationalist conflicts in Southeast Asia, nonviolent resistance, civil- military relations, and Indonesian foreign policy. His work has appeared in prominent journals, such as Publius: The Journal of Federalism, The Pacific Review, and Contemporary Southeast Asia.

Notes

1. Since Indonesia annexed the western half of the island of New Guinea in 1969, the area only had one province of Papua, but later, the Indonesian government created West Papua province in 2003. In December 2022, the state created four more provinces: South Papua, Central Papua, Highland Papua, and Southwest Papua. All of which are commonly referred as West Papua.

2. John Saltford. The United Nations and the Indonesian Takeover of West Papua, 1962–1969: The Anatomy of Betrayal (London: Routledge, 2003).

3. Otto Ondawame, “One people, One Soul: West Papuan nationalism and the Organisasi Papua Merdeka.” Thesis. Department of Political Change and the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (Australian National University, 2000).

4. Shane Joshua Barter and Hipolitus Ringgi Wangge. “Indonesian Autonomies: Explaining Divergent Self-Government Outcomes in Aceh and Papua.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 52, no.1 (2022): 55-81.

5. International Coalition for Papua. “At least 4,862 indigenous Papuans internally displaced.” November 17, 2021, at https://www.humanrightspapua.org/news/33–2021/874-at-least−4–862-indigenous- papuans-internally-displaced-in-puncak-regency.

6. Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde (eds.), Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1998).

7. Thierry Balzacq, Sarah Leonard and Jan Ruzicka. “Securitization revisited: Theory and cases.” International Relations 30, no. 4 (2016): 494–531.

8. Buzan et al., “Security: A New Framework for Analysis;;” Buzan, Barry and Wæver Ole. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

9. Ole Wæver and Barry Buzan, “Racism and responsibility – The critical limits of deep fake methodology in security studies: A reply to Howell and Richter Montpetit.” Security Dialogue 51, no. 4 (2020): 386–94.

10. Didier Bigo, “Security and immigration: Toward a critique of the governmentality of unease.” Alternatives 27 (2002): 63–92; Jef Huysmans, “What’s in an act? On Security speech acts and little security nothings.” Security Dialogues 42, no. 4–5 (2011): 371–82; Thiery Balzacq, “Securitization Theory: Past, Present, and Future.” Polity 51, no. 2 (2019): 331–48.

11. What happens when the media speak security.” in Thierry Balzacq (ed.), Securitization Theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve (London: Routledge, 2011).

12. Buzan et al., “Security: A New Framework for Analysis,” 24; Buzan and Wæver, “Regions and Powers,” 48; Holger Stritzel, “Towards a Theory of Securitization: Copenhagen and Beyond.” European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 3 (2007): 357–83.

13. Johan Eriksson, “Observers or Analysts? On the Political Role of Security Analysts,” Cooperation and Conflict 3, no. 3 (1999): 311–30; Arlene B. Tickner, Securitization and the limits of democratic security in David R. Mares, Arie M. Kacowicz (eds.), Handbook of Latin American Security (New York: Routledge, 2015).

14. Wæver, ‘Securitization and Desecuritization,” in Ronnie D. Lipschutz, (ed.), On Security (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995); Tickner, “Securitization and the limits of democratic security,” 68; Balzacq, “Securitization Theory.” 333.

15. Adam Cote, “Agents without agency: Assessing the role of the audience in securitization theory.” Security Dialogue 47, no. 6 (2016): 541–58.

16. Cote, “Agents without agency,” 549.

17. Cote, “Agents without agency,” 552.

18. Philippe Bourbeau, The Securitization of Migration: A Study of Movement and Order (New York: Routledge, 2011).

19. Paul Roe, “Securitization and Minority Rights: Conditions of Desecuritization.” Security Dialogue 35, no. 3 (2004): 279–94.

20. Jonathan Bright, “Securitization, terror and control: Towards a theory of the breaking point.” Review of International Studies 38, no. 4 (2012): 861–79.

21. Michael C. Williams, “Words, Images, Enemies: Securitization and International Politics.” International Studies Quarterly 47, no. 4 (2003): 511–31; Cote, “Agents without agency,” 551.

22. Williams, “Words, Images, Enemies,;” Cote, “Agents without agency,” 551.

23. Eriksson, “Observers or Analysts?.”

24. Balzacq (ed.). Securitization Theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve (London: Routledge, 2011); Constantinos Adamides, Institutionalized, Horizontal, and Bottom-Up Securitization in The Ethnic Conflict Environments: The Case of Cyprus, Thesis, England: University of Birmingham, 2012, at https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/3791/1/Adamides_PhD_12.pdf.

25. Roe, “Securitization and Minority Rights.”

26. Adamides. “Institutionalized, Horizontal, and Bottom-Up Securitization,” 34; Stritzel, “Towards a Theory of Securitization,” 363.

27. Juha A. Vuori, “Illocutionary logic and strands of securitization: Applying the theory of securitization to the study of non-democratic political orders.” European Journal of International Relations 14, no. 1 (2008): 65–99.

28. Shane Barter, “Rethinking territorial autonomy” cited in Barter, Shane and Hipolitus R. Wangge. “Indonesian autonomies: Explaining Divergent Self Government Outcomes in Aceh and Papua.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 52, no. 1 (2022): 55–81.

29. Eriksson, “Observers or Analysts?.;” Tickner, “Securitization and the limits of democratic security.”

30. Jacques Bertrand, Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia: From Secessionist Mobilization to Conflict Resolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

31. Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, “Securing Peace? Regime Types and Security Sector Reform in the Patani (Thailand) and Bangsamoro (the Philippines) Peace Processes, 2011–2016.” Strategic Analysis 42, no. 4 (2018): 377–401; Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, “Buddhist Majoritarian Nationalism in Thailand: Ideological Contestation, Narratives, and Activism.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2022.2036360.

32. Jacques Bertrand and Cheng Xu, “Indigenous groups and Ethnic minorities,” in Eva Hanson, Meredith L. Weiss (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Civil and Uncivil Society in Southeast Asia (New York: Routledge, 2023).

33. Bertrand and Xu, “Indigenous groups and Ethnic minorities,”252.

34. Azeeem Ibrahim. The Rohingyas: inside Myanmar’s hidden genocide (London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers Ltd. 2016).

35. Adam E. Howe, “Discourses of Exclusion: The Societal Securitization of Burma’s Rohingya.” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 5, no. 3 (2018): 245–66.

36. Patrick Dave Q. Bugarin, “Securitization of the Global War on Terror and counterterrorism cooperation against the Abu Sayyaf Group,” in Frances Antoinette Cruz, Nassef Manabilang Adiong (eds.), International Studies in the Philippines: Mapping New Frontiers in Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2020).

37. Bugarin, “Securitization of the Global War in Terror,” 217–221; Nicole Jenne and Jun Yan Chang, “Hegemonic Distortions: The Securitisation of the Insurgency in Thailand’s Deep South.” TRaNS: Trans – Regional and – National Studies of Southeast Asia 7, no. 2 (2019): 209–32.

38. Jenne and Chang, “Hegemonic Distortions,” 219.

39. Howe, “Discourses of Exclusion,” 254; Erin Bijl and Chris van der Borgh, “Securitization of Muslims in Myanmar’s Early Transition (2010–15).” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 28, no. 2 (2022): 105–24; Naved Bakali, “Islamophobia in Myanmar: the Rohingya genocide and the ‘war on terror.” Race & Class 62, no. 4 (2021): 53–71.

40. Bugarin, “Securitization of the Global War in Terror,” 218; Marie Trédaniel and Pak K. Lee, “Insights from Securitization Theory.” Nationalities Papers 46, no. 1 (2018): 177–95.

41. Bertrand, “Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia” 38; Ondawame, “One People, One Soul”

42. David Easton, A Systems Analysis of Political Life (New York: Wiley, 1965).

43. Ondawame, “One People, One Soul.

44. Interview with a TPNPB fighter in Nduga, 09 January 2021; Stefanus Pramono, “Bayi Dikejar dan Pengungsi.” Majalah Tempo. March 30, 2019.

45. Personal Communication with a village coordinator in Puncak, July 23, 2021; CNN Indonesia, “Bupati Intan Jaya: KKB Minta Dana Desa Beli Senjata.”

46. Brigham Golden, “The Social Dynamics of the Bilogai Region and the Impact of P.T Freeport Indonesia.” Unpublished Baseline Study (Timika: PT Freeport, 1997).

47. Using a triangular method to develop a comprehensive understanding of the armed attacks, I collected data from various sources, i.e., interviews with TPNPB members and residents in conflict locations; TNI and police press releases; TNI’s presentation at the Indonesian Parliament; and newspapers; and human rights reports. Since 2018, the Indonesian Police have recorded 215 attacks that killed 27 soldiers and 9 police; and wounded 51 soldiers and 16 police. https://www.republika.id/posts/19934/empat-prajurit-tni-gugur-di-maybrat

48. The author used a triangular method to develop a comprehensive understanding of the armed attacks.

49. Ibid.

50. The TNI estimated the TPNPB has 735 fighters and 346 weapons. The TNI presented the data in a joint meeting with the Indonesian parliament on May 27, 2021. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r61GsYfD2ZI

51. International Coalition for Papua, “The Neglected Genocide: Human Rights abuses against Papuans in the Central Highlands, 1977–1978.” Report, Hong Kong: Asian Human Rights Commission, 2013. John Otto Ondawame, “West Papua: The Discourse of Cultural Genocide and Conflict Resolution,” in Barry Sautman (ed.), Cultural Genocide and Asian State Peripheries (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

52. Neles Tebay. Dialogue Between Jakarta and Papua: A perspective from Papua in John Braithwaite, Valerie Braithwaite, Michael Cookson and Leah Dunn (eds.). Anomie and Violence: Non-Truth and Reconciliation in Indonesian Peacebuilding (Australia: ANU Press, 2010).

53. Stephen Hill, Captives for Freedom: Hostages, Negotiations, and the Future of West Papua (Port Moresby: University of Papua New Guinea, 2017).

54. Interview with an IDP, Wamena, May 21, 2019.

55. Nduga Solidarity Team, “Nduga’s Armed Conflict and its Effects: Investigation Report,” (2019).

56. Personal communication with a local priest, Intan Jaya, July 20, 2021.

57. Victor Mambor, “The Intan Jaya conflict 2: Violence at the cost of many civilian lives.” Asia Pacific Report, 11 January 2021 at https://asiapacificreport.nz/2021/01/11/the-intan-jaya-conflict−2-violence- at-the-cost-of-many-civilian-lives/.

58. Non-government organizations Coalition (NGO) Report: Political Economy Perspective on Military Deployment in Papua (Jakarta 2019), at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1F98AWDnZNDscPfJ−5WCcJW−8bXFOR5yvNGO Coalition Report, 15.

59. Victor Mambor, “The Intan Jaya conflict: A risk of more widespread violence in future.” Asia Pacific Report, January 07, 2021 at https://asiapacificreport.nz/2021/01/07/the-intan-jaya-conflict-a-risk-of- more-widespread-violence-in-future/

60. Rudy Polycarpus, “Presiden Perintahkan Kejar Pelaku Rudy, Media Indonesia,” 06 December 2018, at https://mediaindonesia.com/nusantara/202392/presiden-perintahkan-kejar-pelaku.

61. Asia Pacific Report. Let’s talk about human rights later’ after “crushing” Papuan rebels, warns Jakarta Speaker, April 29, 2021, at https://asiapacificreport.nz/2021/04/29/lets-talk-about-human-rights-later- after-crushing-papuan-rebels-warns-jakarta-speaker/.

62. Kogawilhan III coordinates the Newangkawi Satgas, a joint task force with the Police to deal with armed conflicts in West Papua. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nAmR_10uync&t=1959s.

63. International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). “Chapter Six: Asia.” The Military Balance, 121:1 (United Kingdom: London, 2021).

64. The operation authority previously rested in the provincial military commands, namely Kodam XVII Cenderawasih and Kodam XVIII Kausari. However, since a three-star general of Kogabwilhan III presides over the joint command, the commanders of Kodam have less authority in dealing with the insurgency.

65. Rizki Fachriansyah, “Papuan resident shot dead during military operation in Intan Jaya.” The Jakarta Post, October 27, 2020.

66. Using a triangular method, I collected data from various sources, such as military press releases, TNI social media, national media, personal communications, and human rights reports.

67. Using a triangular method, the author collected data from various sources, such as military press releases, TNI social media, national media, personal communications, and human rights reports.

68. Using a triangular method, the author collected data from same sources as note 60.

69. Ibid.

70. Hipolitus R. Wangge and Camelia Webb-Gannon. “Civilian Resistance and the Failure of the Indonesian Counterinsurgency Campaign in Nduga, West Papua.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 42, no. 2 (2020): 276–301.

71. Asmara, Tia. “Indonesian Defense Chief: Papuan Rebels Must Be ‘Crushed,’” Benar News, August 14, 2019.

72. Nduga Solidarity Team, “Nduga’s Armed Conflict and its Effects: Investigation Report,” (2019).

73. Personal communication with a local volunteer, Wamena, February 20, 2019.

74. The air raid was strongly allegedly to have been conducted by the TNI (December 2018) in four districts: Nitkuri, Yigi, Dal and Mbua.

75. Amnesty International Indonesia 2020. “Papua: 5 Masalah Ham yang harus diselesaikan.” 8 June 2020 https://www.amnesty.id/papua−5-masalah-ham-yang-harus-diselesaikan/

76. Adrian Pratama Taher, “Konflik Berulang di Intan Jaya Papua karena Pendekatan Militeristik.” Tirto.id, 15 February 2021.

77. Tim Liputan 6. “Menko Polkam: GAM Itu Teroris.” SCTV. July 04, 2002, at https://www.liputan6.com/news/read/37201/menko-polkam-gam-itu-teroris.

78. Budiarti Utami Putri, “Anggota DPR Dukung Pemerintah Tetapkan KKB sebagai Teroris,” Tempo.co April 29, 2021, at https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1457585/anggota-dpr-dukung-pemerintah-tetapkan-kkb-sebagai-teroris.

79. The Police labeled the TPNPB as the armed criminal group (KKB) and pursued The Police labeled the TPNPB as the armed criminal group (KKB) and pursued them in a criminal operation. In contrast, the TNI considered the TPNPB as the armed separatist group (KSB) since the group is a military wing of the OPM. KKB or KSB are two different labels that display competing claims and unclear coordination between the Police and the TNI to deal with local insurgency in West Papua.

80. Personal communication with a BNPT officer on April 7, 2021.

81. The Komnas Ham and civil society groups have contested the BNPT’s reasoning as weak since the political motivation was insufficient to categorize the Papuan nationalist groups as terrorists. In fact, the anti-terrorism law denotes that a self-determination aspiration is isolated from terrorist motivation since the former only peacefully challenges the state. https://icjr.or.id/siaran-pers-elsam-dan-icjr-penetapan-kkb-sebagai-teroris-tidak-tepat-dan-membahayakan-keselamatan-warga-sipil-di-papua/.

82. Paulus Waterpauw, “Papuan Separatist Network,” presented at a national seminar hosted by Universitas Indonesia on May 10, 2021, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLAQ0wS41Lw&t=4076s.

83. The BNPT also invited me, as a researcher, to be part of the discussion.

84. Victor Mambor, “Enembe sebut jumlah OAP di Provinsi Papua 2,3 juta jiwa.” Jubi, September 19, 2020, at https://jubi.co.id/enembe-sebut-jumlah-oap-di-provinsi-papua−23-juta-jiwa/.

85. Callistasia Wijaya and Heyder Affan, “Mahasiswa Papua bicara soal rasialisme: ‘Ih kalian bau’ dan tudingan tukang minum,” BBC News Indonesia, August 23, 2019, at https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia−49430257; Wijaya and Affan 2019; Gunia 2020. Amy Gunia, “A Racial Justice Campaign Brought New Attention to Indonesia’s Poorest Region. Will It Translate to Support for Independence?” Time, December 15, 2020, at https://time.com/5919228/west- papua-lives-matter-independence/.

86. Benny Giay, “Mengapa Kami masih dalam Tempurung?.” Unpublished Paper. Konferensi Kejahatan Negara di Papua Barat dan Dampaknya bagi Kehidupan Sosial Budaya Rakyat Papua Barat. Jakarta, 22–23 March 2002.

87. Tapol. West Papua 2019 “Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Assembly” (London, 2020), at https://www.tapol.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/pdfs/WESTPAPUA2019_FOA_FOE_R EPORT_TAPOL.pdf

88. Marcus Mietzner, “The Coalitions presidents make: Presidential power and its limits in democratic Indonesia.” Online Seminar, ANU Coral Bell School. October 26, 2021.

89. Mambor, “Enembe sebut jumlah OAP di Provinsi Papua 2,3 juta jiwa.”

90. Ondawame, One People, One Soul.”

91. Arjuna Pademme, “DAP Kritik penambahan pasukan dengan alasan keberadaan OPM.” Jubi, 12.

92. Interview with the Nduga regent on 1 April 2019.

93. Dave McRae, “A Discourse on Separatists.” Indonesia, no. 74 (2002): 37–58.

94. Yamin Kogoya, “Papuans protest over draconian bid by Jakarta to replace Governor Enembe,” Asia Pacific Report, 28 June 28 2021, at https://asiapacificreport.nz/2021/06/28/papuans-protest-over- draconian-bid-by-jakarta-to-replace-governor-enembe/.

95. Marchio Irfan Gorbiano, “Not a wise move:’ Critics decry terrorist label for Papuan rebels.” The Jakarta Post, 02 May 2021.

96. Prianka Srinivasan and Hellena Souisa. “Indonesia’s Crackdown in West Papua brings fresh scrutiny to Australian-trained counterterrorism squad,” ABC News, 20 May 2021.

97. The change.org and LIPI conducted a survey involving 27.298 respondents with 19 key questions. The result of the survey can be retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1M−6RLg6oBfAFKavuScHp_wPcYnRtJm5j/view.

98. The media companies and their chains, such as Kompas, Tribunnews, Vivanews, Media Indonesia, RCTI, Kompas TV, have thrown support on security practices in Papua. Kompas TV coined the Papuan Terrorist Group (KTP) to label the TPNPB. https://www.kompas.tv/article/175926/sorotan-kelompok-teroris-papua-diburu.

99. Wangge and Camelia Webb-Gannon. “Civilian Resistance and the Failure of the Indonesian Counterinsurgency,” 279.