Abstract

Objectives: Musicians who wear hearing aids are a unique subset of hearing-impaired individuals. There are a number of issues musicians experience with hearing aids, making effective hearing rehabilitation a challenge. Research suggests hearing aid satisfaction in musicians is lower partly due to their advanced listening skills, however, qualitative research addressing musicians who wear hearing aids for music is scarce. The current study aimed to record the barriers encountered by musicians who wear hearing aids when playing their instrument/singing, listening to recorded music and listening to live music.

Design: Professional musicians who wear hearing aids were interviewed. Participants were questioned about their experiences with hearing loss and hearing aids, with particular emphasis on experiences listening to recorded and live music, and playing or performing music with the hearing aids.

Study Sample: Eight professional musicians were interviewed, using a semi-structured interview style, with a question and prompt guide.

Results: Thematic analysis revealed three main themes in the data: the musicians' journey, communication, and flexibility/adjustability.

Conclusions: The results have implications for future research into specific fitting parameters for hearing aids for musicians (particularly for music performance), the need for evidence-based rehabilitation programs for musicians with hearing loss, and the need for a glossary of terms to assist communication between Audiologists and musicians.

Introduction

Accurate representation of music through hearing aids has been a long-standing technical challenge for hearing aid manufacturers, mostly due to the significant differences between both the dynamic range and the spectral makeup of music and speech. Speech tends to exhibit lower dynamic ranges and a lower crest factor. Crest factor is the difference between a sound waveform’s average in dB, and it’s peak. The crest factor of speech is in the order of 12 dB, whereas music can contain peaks of 18–20 dB (Chasin, Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Speech also contains more asynchronous spectral delivery than live music (Chasin, Citation2022); while recorded music typically tends to have a more restricted dynamic range (Kirchberger & Russo, 2016).

Sound quality issues reported by hearing-impaired listeners when using hearing aids for music enjoyment include distortion in pitch and timbre, difficulties with instrument identification and general dissatisfaction with sound quality (Looi et al., Citation2019; Vaisberg et al., Citation2019). Hearing loss causes physiological changes including damage to the outer hair cells within the cochlea, leading to reduced sensitivity to soft sounds, an abnormal growth of loudness, and reduced frequency selectivity. Inner hair cell and synaptic changes can contribute to poorer pitch perception through reduced sensitivity to temporal fine structures of sound (Moore, Citation2016). Hearing aids are limited by an input dynamic range smaller than that produced by live music. A person with sensorineural hearing loss also has a smaller dynamic range than a person with normal hearing, and sound must be compressed to fit within it (Croghan et al., Citation2014; Kirchberger & Russo, 2016). Hearing aid amplification used to provide audibility of music, while still preserving the spectral integrity of the signal and improving the perceived sound quality, requires changes to compression strategies and input dynamic range, broader frequency spectrum and variations to typical hearing aid prescriptions for speech (Arehart et al., Citation2011; Chasin, Citation2009a ,2009b; Croghan et al., Citation2014; D'Onofrio et al., Citation2019; Hansen, Citation2002; Vaisberg et al., Citation2021).

Hearing aids have traditionally, necessarily, been designed to improve speech intelligibility for improved communication for hearing-impaired listeners (Chasin et al., Citation2012). As technology has developed and improved over time, there has been an increase in demand for higher quality sound reproduction to improve other areas of listener’s lives, including music enjoyment (Chern et al., Citation2022; Greasley et al., Citation2020). Music contributes to various aspects of health-related quality of life in hearing-impaired adults (Dritsakis et al., Citation2017).

Musicians with hearing loss face particular difficulties when using their hearing aids for music performance and enjoyment. Research suggests that a musician’s superior auditory perceptual skills contribute to their dissatisfaction with hearing aid sound quality (D'Onofrio et al., Citation2019). There are limited qualitative studies involving musicians who wear hearing aids. Published qualitative research outlines some themes relating to the use of hearing aids for music, including: participatory needs for musicians playing in ensembles, negative and positive experiences of using digital hearing aids for music, differences in auditory attending styles, challenges faced by musicians being fitted with hearing aids for music, and adaptation and acclimatisation to hearing aids for music (Fulford et al., Citation2013; Vaisberg et al., Citation2019). The aim of the current study was to obtain a more detailed understanding of the unique challenges and facilitators for musicians using hearing aids for music, with a view to establishing how these factors may influence successful hearing aid fitting and management for musicians with hearing loss. Another focus of the current study was to interview professional musicians wearing hearing aids, rather than amateur musicians, or hearing aid users who sometimes use their hearing aids for music listening. The emphasis on recruiting professional musicians ensured the discussion was focussed on music as a central listening goal, providing a broader description of musical experiences than that of an amateur musician or occasional listener.

General hearing aid users report varying experiences in the audiology clinic related to improving music, including a lack of experience or confidence from the Audiologist with programming hearing aids for music. Music training for Audiologists contributes significantly to their confidence with providing advice and programming hearing aids for music, however formal audiological training in music is rare or non-existent (Greasley et al., Citation2020).

The aim of the current study was to determine the rehabilitative barriers and challenges faced by professional or retired musicians. Participants were experienced hearing aid users and used their hearing aids for listening to both live and recorded music, and playing/singing with their hearing aids in. Musicians in the study were invited to discuss their experiences of hearing loss, hearing aids, audiological care, impacts on their professional life and their pathways to rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics committee (approval number 1953900.2). Written, informed consent was obtained from participants prior to conducting the interview.

Participants were selected based on convenience and snowball sampling through professional or personal contacts, direct referrals from other researchers and clinicians, as well as recruitment within the internal University of Melbourne Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology clinic.

During analysis, early codes and evolving themes in the data were iteratively examined throughout the coding process, and no new themes or categories emerged in later interview analyses. Thus, saturation was reached.

Participants

A total of 10 participants were recruited to take part in the interview process. One withdrew prior to being interviewed, and one participant’s interview recording was corrupted and lost prior to completion of the transcription.

Age, gender, audiogram, length of time with hearing loss, length of time using hearing aids, and whether the musician was retired, semi-retired or still active musically were all recorded, and are represented in .

Table 1. Participant details including hearing loss, age, gender, length of time of hearing loss, length of time of hearing aid use, and primary instrument played/musical background.

Data collection

Semi-structured, flexible interviews were conducted by the researchers, using a question and prompt guide (interested readers can access the Supplementary Appendix). Interview topics were devised according to the aims of the investigation. A range of topics was covered, including participants’ musical background, history of hearing loss and hearing aid usage, and impact on recorded and live music sound quality, professional life and personal playing/performance. Questions about the impact of the hearing aid on recorded music, for example, included: What observations have you made when listening to music on a recording with your hearing aids in?

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to code and describe the data in this study. Interviews were transcribed using a combination of the transcription software, Otter AI, and manual transcription undertaken by the researchers. Transcriptions were manually checked for accuracy prior to coding. Coding was undertaken using the qualitative analysis software NVivo 12 (QSR International, Burlington). First author SS undertook all coding. Author IO also coded one transcribed interview to check for intercoder consistency.

The style of thematic analysis followed descriptions from Braun & Clarke (Citation2006), and by Dr Leslie Curry (Curry, 2015). A descriptive style of coding was undertaken in order to provide a full picture of the data. An integrated approach between both inductive and deductive analysis was performed. The inductive (bottom-up) approach allowed for a broad understanding of the interview content, with a somewhat semantic approach taken to label codes at this stage. Subsequently, the initial codes provided a rich description of the data, with minimal interpretive translation performed by the researcher. Deductive thematic analysis was unavoidable, given the specificity of the aims and research questions.

Themes were coded according to a latent style of thematic analysis, using a predominantly constructionist epistemology, in that there were certain assumptions made in examining the underlying ideas behind the data, based on the author’s knowledge and experiences.

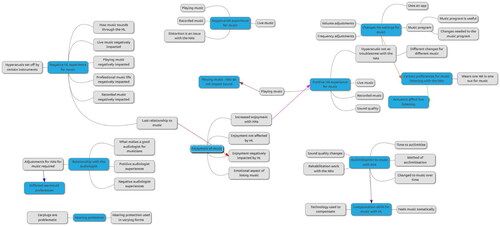

indicates the initial layers of categorisation following data coding, prior to the thematic organisation:

Results

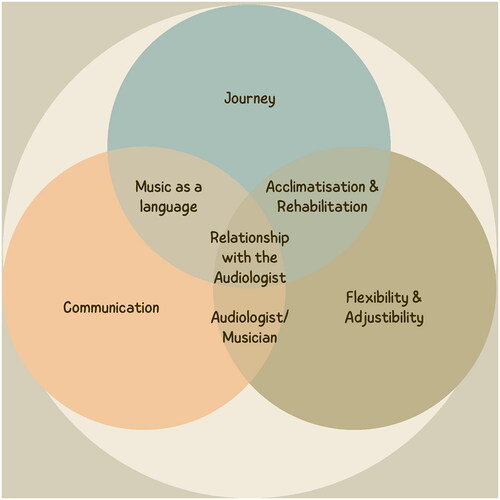

Three primary themes arose from the data in this study: the Journey, Communication, and Flexibility and Adjustability.

The impact of the Audiologist is a sub-theme throughout all themes. This sub-theme was not a topic originally included in the interview question guide, however, it was raised by early participants, and the researcher then questioned participants on it in the later interviews for comparison.

There were a number of codes and categories that were not included in the data analysis because of a lack of applicability to the research questions. For example, one category that emerged was a discussion of hearing protection practices amongst professional musicians, and thoughts on the cause of their hearing loss. The decision was taken to exclude these categories from the broader thematic analysis as these topics were not directly related to the study aims.

Within each of the themes outlined below are various subthemes, many of which intersect with one another, as indicated in .

For example, aspects of the relationship with the Audiologist are discussed in all three themes, as are aspects of acclimatisation and rehabilitation.

This section utilises a thick description of the data to illustrate each theme.

Theme: Journey

The first theme was the Journey:

The loss of music through the hearing loss

Compensation skills and acclimatisation to music through the hearing loss

Professional life and identity as a musician with hearing loss

Initial experiences of music with the hearing aids

Rehabilitation with hearing aids

Relationship with the Audiologist.

The journey was the strongest theme that emerged from the data in this study, encompassing the musicians’ whole experience from initial hearing loss to the time of the interview. There were many sub-themes present within this overarching theme. All participants interviewed described in different terms their journey through the development of hearing loss, the way their relationship with music changed, and how they had to adjust within their professional music lives. Participants described their journey through the process of acclimatisation to the hearing loss and rehabilitation work with the hearing aids. This linked to their journey through finding and connecting with an Audiologist who was ultimately able to help guide them back to music, indicating a journey taken with the Audiologist, leading the musicians back to their relationship with music.

The journey can then be broken down into each of the following sub-themes:

The loss of music through the hearing loss

Participants reflected on the negative impacts the hearing loss had on their emotional connection to music, prior to the rehabilitation process: “to me the emotional aspect of music is something that I missed terribly. Terribly.”

“…it was the complete lack of emotional response to the music.”

Coming to terms with how the hearing loss changed music was described by participants as a very difficult process:

I mean music before…my hearing loss was a rich full immersive experience that, you know, with a lot of bass, you know, and, with a lot of fullness and richness and warmth…I started to notice that it just wasn’t the same experience.

“So a big reason, people say: why did you come back to music? A big part of it was the relationship I had, with the artists, the music, the sounds and those things.”

“But the emotional impact of music upon us is every bit as important as anything else, so getting one’s hearing to a point where they can enjoy music again with a hearing loss is critical.”

“I persevered and made a point of, of listening and trying to find a way back in and yet for many, many, many years, it was just gone.”

Compensatory skills and acclimatisation to music through the hearing aids

Participants detailed the process of acclimatising to the hearing aids for music listening. For most, there was a significant length of time spent actively listening to music and other content before the music began to sound ‘normal’ again: “I remember the moment when a saxophone sounded like a saxophone on the recording.” For some, this process is still ongoing, although improvement in music sound quality and enjoyment since the start of the hearing aid journey was a common thread.

One participant mentioned trying to find information relating to rehabilitation work for music with hearing aids and relied instead on anecdotal advice from fellow aided musicians: “I had spoken to a few musicians who were now wearing hearing aids, things like that, and had some input there, so I knew I had to work hard to rehabilitate. But I couldn’t find much to do”.

Participants discussed using compensatory strategies developed through their hearing loss to assist them with music enjoyment, participation and performance: “I’ve developed all kinds of compensation skills”.

The methods described by the participants varied widely. Some discussed the way their physical bodies helped them when playing and performing music:

“I honestly think that my body, my brain, had worked out different systems in terms of the lack that I was experiencing, so I was experiencing more things in the body, perhaps, in order to work through sound and make sense of sound”

“I would never underestimate the body in our ability to hear…I think because physically, you…hear with the whole body.”

“Your brain has a wonderful ability to retranslate what you’re hearing and what you know you should be hearing… If you’re getting most of the signals, you’ll fill in the rest yourself.”

“I've learned to just sort of- it’s exactly the same thing with tinnitus, you know, you just sort of learn to hear through it.”

“I'll start to play them [Mozart sonatas], and I can hear through, you know, all the garbage in my hearing to, you know, to the music.”

Professional life and identity as a musician with hearing loss

Developing the hearing loss changed participants’ musical professional lives significantly:

“I ultimately decided to change professions, you know away from sound engineering”

it was specifically, there had been over a period of 10 years, probably three occasions where I was playing a solo line in the orchestra. And when I got to the end of it, I noticed that everyone was looking at me strangely, it’s like, what happened? It’s like, you played that entire entry a bar out and I couldn’t hear what was going on around me. So I didn’t even know.

“… it was basically experimenting and trying like hell to do things, and trying somehow another to salvage, you know, you know what I could in my career.”

“And when I don’t have them, I can’t hear properly the other people that I'm playing with, which is, which is why I quit the music.”

Initial experiences of music with the hearing aids

The participants discussed issues with the sound quality of hearing aids for music when they were starting out.

“the frequency response was so lousy”

“frequency response was terrible, you know. Big peaks and valleys”

“Trying to make sense of the new sound that I had and it, yeah, everything sounded quite tinny and yeah it was disappointing, it was disappointing.”

Some of those issues are ongoing despite rehabilitation work and technology advancements, particularly in live music settings, and particularly with reference to distortion in the sound quality:

“there’s still distortion. I still hear distortion.”

“Like as in very slight distortion effect.”

Some instruments, so for example, it must have something to do with the harmonics, but the piano I find is one of the most difficult instruments to listen to with hearing aids in. I can find I’m often battling the rustling distortion sound which happens with the hearing aids there. That’s the most pronounced, I think, of all of the instruments of being a bit frustrating.

It can distort. I don’t listen to that much music when it’s that hectic. But yeah, they can distort. I think I notice more so the little distortions and things like that in softer music than I do in louder music. The imperfections in sounds on account of the hearing aids, I noticed far more in chamber music than I would in listening to louder music. Although, I notice that it can distort.

Rehabilitation with hearing aids

Participants had different methods to help themselves rehabilitate to music with their hearing aids. The musicians used both familiar recordings and single line melodies or less complex music to acclimatise:

I would put on Elgar’s cello concerto. I knew it quite well, and I would play it every time I’d get in the car. And what I would do is I would operate off my memory of the piece, rather than what I was hearing… I was using what I was hearing as a guide to my memory of the piece.

So I would sit down at the piano, and just play notes, or play a melody, by myself. No singing, nothing else, just doing that. And I think, the, the process of getting me back to where I am really started there…cut down what you listen to way back. Way back. And stop wanting to hear the Rolling Stones, or the London Symphony. And listen to a solo violin.

“Right, so for me, I cut way back in what I was listening to. And the, even now, I listen to solo instruments.”

“And in addition to my own music, though, I started to listen to music that I didn’t know. Just to give my ears the exercise of hearing new things.”

Relationship with the Audiologist

All participants talked about the importance of the work they did with Audiologists and in the programming process with the hearing aids:

“I’m grateful to my Audiologist. A very important point. Maybe the most important tool that a musician has is a good audiologist.”

“I think one who really dissects who you are as a person and what your hearing needs will probably be…And if they know music they will know you.”

She knew that it was a critical issue, not just normal life…but this was central to my life and she was determined to find a way that, like when we talk about listening to music she was determined to find some hearing aids for me that I would enjoy that again.

Theme: Communication

The second theme was Communication:

Music as a language

the negative impact of hearing loss on music

the negative impact on music of hearing aids

the positive impact on music of hearing aids

The Audiologist

Communication is a theme present in all of the interviews in this study. Music is a form of communication between humans, and Audiologists are largely struggling to assist with this communication method when fitting hearing aids to musicians with hearing loss.

Music as a language

The negative impact of hearing loss on music

Unsurprisingly, most participants discussed the negative impact hearing loss had on music. A common description of this impact related to how confusing music sounded through the hearing loss:

I think, my ears just couldn’t, couldn’t work it out. It was, they’d get overwhelmed…by the frequency where I still had good hearing, and so…I had to be somewhere where those frequencies were coming in much stronger.

I think it was just there was so much cognitive business going on to decode what I was hearing that I was just emotionally blank, and had no response to the music I was listening to. And I didn’t know why I just thought I'd sort of lost my enjoyment of it.

“I really lost so much understanding of the tone colour, or the timbre of the instruments – I was so confused by it.”

Music as a language: the negative impact on music of hearing aids

This confusion relating to music was also a description which was used to outline how music sounded through the hearing aids:

“I think in terms of, the dynamics didn’t make sense, so I couldn’t tell how loud I was.”

“Obviously at the beginning it was really hard, and I felt most confused with those live instruments that I described earlier. Like not being able to tell what instrument was what.”

And sometimes I’d, I remember I’d also be confused by directions. Like which direction it was coming from.

I couldn’t pin-point sounds in the orchestra, like it’s so bizarre to begin with. I, for example, I kept saying to my friend it sounds like there is off-stage brass. So, this is when they put particular brass instruments off-stage in order to have this effect of distance and things like that. And that’s what it felt like, but I would be looking – and it would be the violins taking a solo. So, I would be like why does this sound like off-stage brass?

At first, I couldn’t make sense of my own sound. It sounded like, um, like I just felt disconnected. I felt disconnected from it. It sort of felt like when you’ve got pins and needles in your feet and you can’t really stand on your legs or whatnot until you’ve got feeling. It felt like that. I knew that I was making a sound. I knew that I could hear a sound, but it wasn’t mine. That was really confusing to begin with.

The positive impact on music of hearing aids

This then led to a discussion of how hearing aids have helped with these issues:

I feel like the most pronounced thing, the thing that I missed, and the thing that I notice most is this idea of muted compared to – it’s richer, it’s open sound. This is going to sound really strange, but I feel like there’s more space in the sound when I’m listening with hearing aids.

…music sounds very dull and flat and low. Sort of muted sounding. And then you put the hearing aids on, it sounds live again. So, you know provides all the high frequencies. So it’s fantastic to transform music. I don’t do any music, either playing it myself or listening to it really without the hearing aids.

“The hearing aid sound becomes your new point of reference. Your new reference sound, your new normal.”

“Engagement with music returned after a couple of months of HA use”

“And then what happened was eventually that all overlapped, and then it sounded normal…A violin sounds like a violin. A clarinet sounds like a clarinet.”

“Now they just sound like themselves. I guess essentially I’ve taught myself to make sense of those sounds in the identity that I first knew them. So now they just sound as they should.”

The Audiologist

The importance of the Audiologist being able to translate what the musician is describing they are hearing was also discussed:

“Yeah, well they have to be able to describe what they’re hearing, and the Audiologist has to be willing to um, put up with people like…me”

“Um, he didn’t understand music talk, you know…And music terminology was something that he just couldn’t, you know, that he didn’t know at all.”

“Yeah, that would be- that would be useful to have some sort of glossary…a lot of Audiologists don’t quite understand what an octave is…or what harmony is. And I think…many musicians don’t know what a frequency is…and doesn’t understand the difference between frequency and pitch…It’s important…I think really to get some sort of working vocabulary.”

Flexibility & adjustability

The third theme was Flexibility and Adjustability:

Acclimatisation to the hearing aids

Audiologist-led adjustments

Musician-led adjustments

Musicians’ expectations

The question of flexibility, of both the musician and the Audiologist, is one that was discussed in the context of acclimatisation to the hearing aids, both Audiologist-led and musician-led adjustments to the hearing aids, and flexibility in participants’ expectations.

1. Acclimatisation to the hearing aids

Timbre, that’s just become warmer. All of the instruments have become warmer, and post, this is all connected to the rehabilitation process, as I got used to the hearing aids, I was working with the hearing aids. Essentially, I was working with them to make sense of what I was hearing. Everything became warmer. And I lost that tinniness.

“I think the, so the engagement with music, probably after that probably took a couple of months before it was really back.”

The musicians talked about the importance of perseverance and determination to acclimatise to the hearing aids:

“I think passion had a lot to do with it, I really wanted it back.”

Audiologist-led adjustments

There was advice for musicians looking for an Audiologist:

“Find an audiologist who’s willing to help you experiment as well…Yeah, yeah. And who finds it enjoyable. You know, who finds it interesting, you know.”

The main thing was her understanding that the needs of a musician were going to be very specific to that musician and that’s why we kept hunting through so many different styles of hearing aids, and trying to find…the ones that worked.

I would walk in with an instrument, and play, and we’d listen to it as well. And then she was able to, with her computer and everything else, um, set it: you need this for you. I want somebody to tell me that. Because they say: well what do you need? I haven’t a clue! Try things. See what works, you know?

And they’re…hard to find…you have a hard job. I mean, you really do.

I mean, and, and musicians are the worst. [laughs] We’re the worst.

I don’t do this but I have friends who like bring their guitars in, who bring their, you know, bring their instruments in and I'm sure they drive their Audiologist crazy.

I'm not that picky, but, but, but, but I- but there are some things that I need, and I try to impart them, you know.

Musician-led adjustments

Being able to make their own adjustments to the hearing aids for flexibility in their music listening was a common thread:

“Well, basically, I just, I fiddle all the things until it sounds the most comfortable.”

“So better means it just feels nicer and sounds better to me when I fiddle it that way.”

“But it’s, it’s um, whatever, whenever I perform it’s a matter of getting your technology right.”

“And I think having control when I’m performing, or recording is absolutely critical, because you can get your engineer to do just so much.”

“But I really liked having the easy, simple, telephone control, so I can make all those different adjustments for all the different circumstances.”

“I think it’s critical to have control over your soundscape, if that’s the word, I don’t know.”

“And I can go into the app and I can change treble, bass, mid-range, um, and volume and all those other things too, uh.”

Musicians’ expectations

The participants in this study acknowledged the need to adjust their own expectations in relation to how music sounds through hearing loss, and with hearing aids:

“it’s one of these things that after a while you just accept that this is the way it is, you know. You lower your expectations, and you say, All right. This is what music is.”

“the more musicians I think understand that there is technology that can help, they just need to experiment. I think the general principle, I think is something that should be, you know, imparted.”

“I was really excited by this new experience I was about to do”

Discussion

The participants in this study talked about many experiences relating to the hearing loss and the process of using hearing aids, and the main themes that emerged, outlined in the above results, speak to those experiences.

The original questions the researcher formulated for this study were:

What unique challenges, if any, do musicians who wear hearing aids encounter when listening to or playing music with their hearing aids in?

What observations, both negative and positive, do musicians with hearing aids observe in relation to music dynamics and timbre?

Throughout the interview and coding process however, the research questions changed and evolved reflexively because of how much the participants wanted to talk about their experiences of losing music through the hearing loss. A more appropriate research question would have been: What are the experiences of musicians with hearing loss who wear hearing aids, in hearing rehabilitation?

Participants spoke about the negative impact their hearing loss had on listening to, playing, engaging with and enjoying music. The language used between participants varied, but, predictably, hearing loss universally had a negative impact on music for them all.

There were also negative aspects of hearing aids related to music sound quality described by participants. However, the overall positive impact the hearing aids eventually had on music emerged during the analysis. The response from participants on the effect of the rehabilitation work on their enjoyment of and involvement in music indicates that the process is worthwhile if it leads to better outcomes for musicians. Perhaps predictably, the severity of hearing loss had an impact on the time of acclimatisation to the hearing aids. Two of the musicians with milder degrees of hearing loss found the acclimatisation process to hearing aids to be quite short (almost instantly and approximately two weeks). However, two participants with more severe degrees of hearing loss have spent many years acclimatising to the sound of music through the hearing aids, and are still working on this process at the time of writing.

Given the extent to which participants discussed their methods for acclimatisation to performing and listening to music with the hearing aids, it would be useful to have some evidence-based clinical guidelines around what sort of rehabilitation program would assist with leading musicians with hearing loss to greater success with their hearing aids in terms of music listening, enjoyment and performance. As far as the researcher can find, there is no discussion in the literature about the efficacy of different types of rehabilitation plans designed to improve music perception and enjoyment in hearing aid users, outside generalised listening programs (Shukor et al., Citation2021). However, there are some clinical protocol resources available for the Audiologist addressing the needs of musicians, namely Dr Marshall Chasin’s textbook, Music and Hearing Aids – A Clinical Approach; and Clinical Consensus Document – Audiological Services for Musicians and Music Industry Personnel, published by the American Academy of Audiology (Citation2020).

For example initial counselling sessions for musicians wearing hearing aids for the first time, realistic expectations of hearing music through the digital processing of the hearing aids, and the gradual process of acclimatisation at the start of the rehabilitation journey. Counselling musicians on the positive outcomes others have experienced following their rehabilitation work would motivate musicians as well. Audiologists working with musicians should suggest trying different methods such as listening to very familiar recordings, or single line melodies, as suggested by some of the participants here. This would be particularly useful for those musicians with more severe hearing loss, and those with distortions in their hearing such as diplacusis, caused by damage to the inner hair cells and synaptic processes.

There is still work to be done on improving the sound quality of hearing aids for music listening, in particular in a live music context. Despite the positive responses from participants on the overall benefit of music listening from hearing aids, many ongoing issues were highlighted, in particular in reference to live music distortion.

There is already evidence to suggest certain hearing aid parameters are necessary for improved music sound quality in hearing aid programming. For example, a higher input dynamic range is needed than for speech (>96 dB), due to music having a larger crest factor and dynamic range than speech. Noise processing such as adaptive noise reduction features and feedback cancellation should be deactivated as these features can create distortion in music. Hearing aids should be set to omnidirectional mode, in particular for live music settings, as directional microphones alter music signals within an acoustically designed auditorium. Slow-acting, wide dynamic range compression is generally preferred for music listening than fast-acting, and linear is preferred compared to using a Nal-NL2 prescription rationale. This is most likely because dynamic compression introduces distortion to the amplified sound, necessary for speech intelligibility, but the purpose of listening to music is primarily for enjoyment rather than intelligibility (Kirchberger & Russo, 2016; Moore & Sek, Citation2016). All of these changes are likely to disrupt speech intelligibility sufficiently that a separate, manual listening program for music will be necessary.

The musicians interviewed in this study strongly recommended improvements to Audiologists’ training in terms of understanding musical language, and translating this into audiological terms that can be converted into adjustments to hearing aids to improve music perception. For example, the terms ‘timbre’, ‘dynamics’, ‘pitch’ and descriptors such as ‘full’, ‘rich’, ‘dull’ and ‘bright’, came up persistently when discussing musical sound quality through the hearing aids, and Audiologists with little or no musical training may struggle to translate these descriptors into audiological terms. More obscure terms were used to describe music as well. When one of the musicians was discussing the sound quality of their hearing aids with their Audiologist: “I talked about the sizzle of cymbals or the shimmer of violins. And I also said the rustle of leaves.”

The participants wanted their Audiologists to be patient, try many different hearing aids and different adjustments to the hearing aid parameters, and allow access to self-adjustments for the musicians. There are challenges to implementing this in a clinical setting, given the cost of multiple appointments and multiple sets of hearing aids, so clear goal-setting and expectations for the musician client is important here. The counselling skills of the Audiologist managing musician clients must be called upon here. Access to self-adjustments can be provided in the form of a mobile phone app connected to the hearing aids via Bluetooth, which is widely, though not universally, available in modern hearing aids today. Onward referral to an Audiologist able to provide access to these additional services, and hearing aids enabled with an appropriate self-adjustment app, should be encouraged.

Self-adjustments of volume and frequency through the use of a music program and/or the use of an app on the musician’s smartphone device were aspects that contributed to eventual positive outcomes for music listening and performance. There was a broad range of self-adjustments reported, and different changes were made for different types of music stimuli, further highlighting the need for flexibility in hearing aid fittings for musicians.

Given the variety of changes to the sound preferred by the participants for different music settings and different genres and instruments, strict adherence to existing prescriptive targets and compression characteristics is not necessarily going to provide optimal sound quality for music stimuli, so flexibility is required on the part of the Audiologist.

Flexibility is also required to allow musicians to use novel stimuli in clinical fitting and adjustment appointments, for example playing their instruments or singing to assess the sound quality of the adjusted hearing aids, or perhaps bringing in their own recording technology and speakers if the audiology clinic in question has inadequate quality speakers for music perception, as is often the case if using standard hearing aid programming technology.

The need for flexibility in the way hearing aids are programmed for music in different settings is important. Live music settings were reported in terms of a negative hearing aid experience far more in these interviews than recorded music or even music performance and playing. Distortion was the most common comment when referencing using the hearing aids in a live music setting. It is possible the distortion present in live performances relates to the inadequate input dynamic range in standard hearing devices, given the large dynamic range of live music.

The importance of educating musicians with hearing loss in the best use of technology is also clinically relevant and applicable here. There is a variety of technology available outside of conventional hearing aids, such as in-ear monitors, headphones customisable to the audiogram, and active musicians hearing protection, which Audiologists can discuss with musicians to allow for a patient-centred, informed choice approach to their rehabilitation.

The themes uncovered in this study indicate the need for further investigation for musicians’ hearing care. Potential avenues for further research include:

Investigation into appropriate acclimatisation programs for musicians wearing hearing aids for the first time.

Improving sound quality of hearing aids, in particular issues of distortion in live music settings.

Investigation into music sound quality with different hearing aid parameters using live music as the stimulus, rather than recorded musical excerpts.

Investigation into appropriate self-programming and self-adjustment techniques for musicians using hearing aids.

These suggestions may be clinically difficult to implement in many modern audiology clinical settings due to time, clinical and financial constraints, but it is important to prioritise the implementation of a financial model that will be acceptable to all parties, because the evidence suggests a model for hearing rehabilitation policies and procedures for musicians with hearing loss is a necessary addition to the clinical audiology setting/environment. This further highlights the importance of developing an evidence-based musician’s hearing aid fitting protocol, to reduce potential time requirements for this cohort of patients.

One limitation of this study was that the first author did all of the initial layers of coding. However, independent coding of select interviews was undertaken by author IO, and compared to verify the consistency of emergent themes. The experience of author SS as both a musician and an Audiologist contributed to a contextual interpretation of the data. The first author’s background in both music performance and Audiology enabled the emergent categories and subsequent themes to be drawn from her clinical and musical experience and understanding of descriptive musical language.

There was a degree of selection bias in the study – the people who are seeking out audiological help and spending long periods of time working towards a successful outcome may be more inclined to participate. The Audiologists who are volunteering participants may tend to choose those who have had successful outcomes.

There were further limitations related to the small sample size. It was not possible to draw any broad conclusions about the correlation between the degree of hearing loss and length of time or method of acclimatisation to music through the hearing aids. The small sample size also limited the exploration of differences in the language used to describe music sound quality through hearing loss, depending on the degree of hearing loss.

Conclusion

The aims of this study were to uncover barriers and challenges musicians who wear hearing aids encounter when listening to or playing music with their hearing aids in, and to reveal observations of musicians who wear hearing aids with regard to music timbre and dynamics.

Three main themes with multiple sub-themes emerged from the study. The first theme was the Journey, including: the loss of music through the hearing loss, compensatory skills and acclimatisation to music through the hearing aids, professional life and identity as a musician with hearing loss, initial experiences of music with the hearing aids, rehabilitation with hearing aids, and the relationship with the Audiologist. The second theme was Communication, including: music as a language (the negative impact of hearing loss on music, music as a language: the negative impact on music of hearing aids, and the positive impact on music of hearing aids), and the Audiologist. The final themes were Flexibility and Adjustability, including: acclimatisation to the hearing aids, Audiologist-led adjustments, musician-led adjustments, and musicians’ expectations.

This study will inform future research into how to improve music listening and performing outcomes for hearing-impaired musicians, through evidence-based music-specific audiological rehabilitation and hearing aid fitting.

This research will benefit musicians, as well as any hearing-impaired listeners who wish to use their hearing aids to improve their health-related quality of life outcomes by improving the sound quality, and their subsequent enjoyment of music.

Disclosure system

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Thank you to Anushka Vallabh and Henry Madin, who assisted with data collection for some participants. Many thanks to the musician participants who shared their experiences for this study.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author, SS. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

References

- American Academy of Audiology 2020. Clinical Consensus Document. www.audiology.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Musicians-Consensus-Doc_Final_1.23.20.pdf

- Arehart, K. H., J. M. Kates, and M. C. Anderson. 2011. “Effects of noise, Nonlinear Processing, and Linear Filtering on Perceived Music Quality.” International Journal of Audiology 50 (3):177–190. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2010.539273

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chasin, M. 2022. “Music and Hearing Aids – A Clinical Approach.” San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing Inc.

- Chasin, M. 2009a. CONCLUSIONS : THE “MUSIC PROGRAM.” 5–6.

- Chasin, M. 2009b. Music and Hearing Aids. https://jcaa.caa-aca.ca/index.php/jcaa/article/viewFile/2166/1913

- Chasin, M., N. Hockley, and M. Chasin. 2012. “Music and Hearing Aids—An Introduction.” Trends in Amplification 16 (3):136–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084713812468512

- Chern, A., M. W. Denham, A. S. Leiderman, R. K. Sharma, I. W. Su, A. J. Ucci, J. M. Jones, D. Mancuso, I. P. Cellum, J. A. Galatioto, et al. 2022. “Hearing Aids Enhance Music Enjoyment in Individuals With Hearing Loss.” Otology & Neurotology: Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 43 (8):874–881. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003595

- Croghan, N. B. H., K. H. Arehart, and J. M. Kates. 2014. “Music Preferences With Hearing Aids: Effects of Signal Properties, Compression Settings, and Listener characteristics.” Ear and Hearing 35 (5):e170–e184. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000056

- D'Onofrio, K. L., R. H. Gifford, and T. A. Ricketts. 2019. “Musician and Nonmusician Hearing Aid Setting Preferences for Music and Speech Stimuli.” American Journal of Audiology 28 (2):333–347.

- Dritsakis, G., R. M. Van Besouw, and A. O' Meara. 2017. “Impact of Music on the Quality of Life of Cochlear Implant Users: A Focus Group Study.” Cochlear Implants International 18 (4):207–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2017.1303892.

- Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J, & Greasley, A. (2013, August). Hearing Aids and Music: The Experiences of D/deaf musicians [Conference session]. Ninth triennial meeting of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, in Manchester, United Kingdom. https://www.academia.edu/15072626/Hearing_aids_and_music_the_experiences_of_D_deaf_musicians.

- Greasley, A., H. Crook, and R. Fulford. 2020. “Music Listening and Hearing Aids: Perspectives from Audiologists and Their Patients.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (9):694–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1762126

- Hansen, M. 2002. “Effects of Multi-Channel Compression Time Constants on Subjectively Perceived Sound Quality and Speech Intelligibility.” Ear and Hearing 23 (4):369–380. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003446-200208000-00012

- Kirchberger, M., and F. A. Russo. 2016a. “Dynamic Range Across Music Genres and the Perception of Dynamic Compression in Hearing-Impaired Listeners.” Trends in Hearing 20:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216516630549

- Looi, V., K. Rutledge, and T. Prvan. 2019. Music Appreciation of Adult Hearing Aid Users and the Impact of Different Levels of Hearing Loss

- Moore, B. C. J. 2016. “Effects of sound-induced hearing loss and hearing AIDS on the perception of music.” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 64 (3):112–123. https://doi.org/10.17743/jaes.2015.0081

- Moore, B. C. J., and A. Sęk. 2016. “Preferred Compression Speed for Speech and Music and Its Relationship to Sensitivity to Temporal Fine Structure.” Trends in Hearing 20:233121651664048. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216516640486

- Shukor, N. F. A., J. Lee, Y. J. Seo, and W. Han. 2021. “Efficacy of Music Training in Hearing Aid and Cochlear Implant Users: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology 14 (1):15–28. https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2020.00101

- Vaisberg, J., P. Folkeard, S. Levy, D. Dundas, S. Agrawal, and S. Scollie. 2021. “Sound Quality Ratings of Amplified Speech and Music Using a Direct Drive Hearing Aid: Effects of Bandwidth.” Otology & Neurotology: Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 42 (2):227–234. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000002915

- Vaisberg, J. M., A. T. Martindale, P. Folkeard, and C. Benedict. 2019. “A Qualitative Study of the Effects of Hearing loss and Hearing Aid Use on Music Perception in Performing Musicians.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 30 (10):856–870. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.17019