ABSTRACT

The civil service has seen dramatic changes over the last 50 years, symbolized by the shift from Traditional Public Administration, to New Public Management and now New Public Governance. Likewise, the role and nature of people management functions has changed with the development of Strategic HR and Human Resource Development (HRD). Finally, the nature of higher education has changed with a growing emphasis on research impact, knowledge exchange, and industry-academia links such as focusing on employability. In this research we explore the development of the Bahrain Institute for Public Administration’s (BIPA) Master in Public Management (MPM) program. Drawing on extensive fieldwork with students, managers, and stakeholders we identify how this program was established, how students were selected, and the implications of their study on the program for the success of the Bahrain government.

In the face of trends reshaping the world of civil servants, and the demands on universities for greater relevance, one response might be to identify an increasing gap between the practical experiences of civil servants and the education available to them in higher education. If we think that a gap has been created by trends in many civil service organizations and the growing expectation that universities are relevant as well as rigorous, then it may seem obvious that the gap should be closed by redesigning university programs to make them more relevant to the needs of civil servants. But this should not be attempted idealistically, but informed by evidence of what new designs for campus-based programs might realistically achieve. This involves not only recognizing the trends and developments in the civil service but also tempering any ideas for transformational redesigns of programs by looking at what works in practice.

The civil service has experienced significant change over the last fifty years. Specifically, this is characterized as a shift from being seen as staffed by administrators, focused on policy and the delivery of public services, to the growing need for managers to deliver efficiency, effectiveness, and equity, to more recently requiring leaders to adapt public services to change, enabling cross-sectoral collaboration and bringing about reforms. It is an appealing simplification to think of the transitions of administrator to manager, followed by manager to leader as summing up recent civil service history. Recent remarks by commentators on the civil service demonstrate this focus on leadership, with fleeting or no references to the work of administration or management, as in these remarks by Beth Simone Noveck who made the case for more mission-driven and agile leaders (Abramson, Citation2021):

But I would like to see more mission-driven leaders who are agile, data driven, and human centered. I have a vision of civil servants as public entrepreneurs who are passionate about solving problems. […] I would also like to see more agile implementation, more collaboration, and more measurement of what works.

Of course, the actual trajectory of change may not have been a successive set of distinct stages, so much as an evolution of partial displacements and additions, with some merging of the new and the old.

Likewise, approaches to the training and development of civil servants has evolved, reflecting in part the shift from personnel management, to Strategic HRM, and more recently Human Resource Development (HRD). As well as staff appraisal systems there are now new tools of competency frameworks (Civil Service Human Resources, Citation2018) and talent management (Australian Public Service Commission, Citation2019). Finally, the world of higher education has seen a shift toward educators and researchers in universities taking greater concern over the relevance of their activities. Signs of this include demands for graduates to be more employable and for academic teaching and research to be more relevant to organizations beyond the university.

The importance of employability and relevance can be seen as far back as the 1980s, when one program development for public services included mandates for “courses that relate to the job knowledge and skills” of employees of New York State and “state of the art” features (Faerman et al., Citation1987, p. 310). In relation to employability, we might note both the growth of interest in educational courses developing both personal skills and vocational competencies, and a strengthening of concern for the transfer of learning from campus to work to improve job performance and to increase organizational performance.

In demonstrating the value of formal higher education, it is important that academic educators demonstrate the relevance and positive outcomes of their programs, particularly compared to on-the-job training offers and other less formal training opportunities. This study makes a contribution to our understanding of the value of university-level education for civil servants for both the individual students and for their employer. Whilst the contextual nature of the research means that direct correlation to other jurisdictions cannot be asserted, we do believe that the nature of the context and the significance of our findings do provide important lessons for other governments and government agencies across the world.

In the sections below, we set out some issues and choices facing the designers of programs for civil servants, describe our approach to data collection, present our findings and identify some of the insights offered by the findings for designing new educational programs for experienced civil servants. But first we introduce the context of our case study on the Bahrain civil service.

The case of Bahrain

Bahrain is a small island nation located in the Arabian Gulf and is known for its relatively open economy and its operation of a national assembly with elected representative in its system of public governance. Despite social turmoil fueled by both internal and external factors, spanning the two decades of the 1990s and 2000’s and culminating in the Arab Spring of 2011, Bahrain has been able to develop an effective public sector geared to the fulfillment of its population needs (Common, Citation2008). Bahrain’s government has invested in various social services, including education, healthcare, housing, and social welfare. A major drive of the public service has been to improve the quality of these services and make them accessible to the population. Digital transformation has been at the center of this drive, as evidenced by the pioneering successes of Bahrain e-government (Mahmood et al., Citation2019). This includes e-government services aimed at improving efficiency, transparency, and accessibility for citizens and businesses.

The reform project started in the early 2000s with the goal to transition Bahrain into a diverse and vibrant economy, less dependent on gas and oil. The Bahraini government has launched various initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable development, fostering entrepreneurship, and enhancing public services. These initiatives have impacted the overall public service landscape yet, as with other Gulf-Cooperation Council states, it remains under-researched, particularly within the main public administration journals (Biygautane, Citation2023).

Over the decade from 2010 to 2021, the estimates of government effectiveness published by the World Bank (World Bank databank), show notable improvements in government effectiveness for Bahrain. This increase in Bahrain’s government effectiveness estimate seems to correlate with progress in tackling some of the biggest government challenges of the day, namely, human development (i.e., human sustainability), environmental performance management (environmental sustainability), and the development of online government services. For example, in 2010 Bahrain had one of the highest OSI (online service index) scores—it was ranked 8th. In terms of e-government development, it was also ranked 13th, which was a high ranking (see page 60 of the United Nations report on e-government in 2010). Indeed, there appears to be a strong correlation between changes in government effectiveness estimates and changes in the Human Development Index scores published by the United Nations. These improvements, which include the quality of the civil service, can be contrasted with some European countries such as Denmark, Finland, and the UK, which have been “coasting.”

The positive perception of the Bahrain public sector is likely to create a positive environment for government work. In turn, this positive work environment will drive higher levels of engagement, satisfaction, and productivity amongst employees. Direct determinants of the work environment include job stability; compensation and benefits; work-life balance; career advancement and opportunities for growth; job satisfaction; bureaucracy and the work culture.

Indeed, a survey of the Bahrain public sector, conducted by a global HR consultancy in 2010, found that employees have a positive orientation to work. More than nine out of ten (93%) of public sector employees were found to have medium to high career orientation. More than nine out of ten (92%) believed that they were growing and developing in their job (medium to high score). Almost all (99%) had a strong belief in their sense of accomplishment and worth in the job through a variety of paths: the work itself, its perceived contribution to the greater good and interactions and relationships with others. Almost all (96%) had a high to medium sense of pride in being part of the public institution they worked for. These and many other variables were regressed on a set of outcome variable including employee engagement which was found to be very high (at 85%).

All the above suggests that the Bahrain public sector environment is generally a positive environment where people thrive. The MPM students come precisely from this type of environment, and it may be inferred that they were eager to learn and to then translate that learning into better practices at work.

The development of civil service capabilities and improving outcomes in Bahrain may have engendered a positive climate for professional development. The trends toward better results and the can-do spirit in the Bahrain civil service creates opportunities for leadership to be valued and fostered. This climate, and the opening-up of leadership opportunities, may mean that students on a new master’s program to support leadership development in Bahrain had realistic expectations that they would get promoted following their participation in the program.

The pursuit of relevance through redesign

Several issues emerge from thinking about developing more work-relevant education programs. One issue is the relative importance of knowledge, skills, and behaviors as learning outcomes. The second is the balance struck between management and leadership. The third is the explicit attention given to student engagement within the learning process. The fourth is the transfer of learning. The fifth is the role of the university educators in the delivery of educational relevance and the dovetailing of their role for what might be the complementary roles of students and line managers.

Logically, the design of new educational programs for experienced civil servants should not be led by the selection of subject content, but by an understanding of the educational needs of the students and their employers. Traditionally, university educators have focused on the transfer of knowledge by lecturing students (known also as the deficit model) and, more progressively, have encouraged the student’s development of cognitive skills (e.g., knowing, understanding, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation). The main learning outcomes could prioritize the learning of knowledge, skills and behaviors, or a combination of them.

With the rise of competency frameworks for civil servants, it might seem that university programs could be made more relevant by defining the program learning outcomes as a set of individual competencies. Competencies have been defined as, “the skills, knowledge and behaviours that lead to successful performance” (Civil Service Human Resources, Citation2018; UK Government, Citation2014). Alternatively, each competency can be seen as a definition of excellence in working behavior, which implies that successful performance by civil servants is equated to normatively prescribed behavior, rather than measured by the achievement of desired outcomes with public value consequences (IAEA, Citation2020, p. 3):

A competency framework is a model that broadly describes performance excellence within an organization. Such a framework usually includes a number of competencies that are applied to multiple occupational roles within the organization. Each competency defines, in generic terms, excellence in working behaviour; this definition then establishes the benchmark against which staff are assessed. A competency framework is a means by which organizations communicate which behaviours are required, valued, recognized and rewarded with respect to specific occupational roles. It ensures that staff, in general, have a common understanding of the organization’s values and expected excellent performance behaviours.

Competency frameworks are used throughout the United Nations system, as well as in many government and private sector organizations.

Excellent performance behaviors in a competency framework might be defined as “functional competencies” and linked to role requirements to distinguish them from the broader definition of competencies as including skills and knowledge. It is possible to imagine campus based educational programs involving the assessment of functional competencies by asking students to prepare “portfolios” containing reports of workplace evidence. The university teacher might assess the portfolios of reported workplace evidence against the “ideals” set out in published statements of functional competencies. This has happened and some university lecturers have been formally certified as assessors of workplace evidence.

The greater focus on competencies has coincided with an increasing emphasis on management and leadership in public administration programs alongside more “traditional” aspects of the curriculum such as politics, law, economics, sociology, public policy analysis and implementation. At the same time as there have been curricular changes there have also been significant changes to the pedagogy of public administration. One such change in the design of programs is the evolution of the role of students, from passive to active learners, so that students are increasingly challenged to take more responsibility for their learning experience. Increasingly students are expected to be active in the learning process. Consequently, it is assumed that the learning skills and motivation of students are vital in producing good educational outcomes. The implication for program design is the attention paid to facilitating “student engagement” or even co-design (Elliott et al., Citation2021) in the learning process.

A wide range of tools and approaches can be used to facilitate student engagement and participation. Examples include increasing emphasis on problem-based assignments, including the introduction of consultancy projects instead of the more traditional research dissertation module. Arguably, such redesigns aim at higher levels of engagement through the shift toward a more problem-based curriculum and, at the same time, greater relevance by addressing problems emerging in practical experience.

In designing programs that are intended to improve job performance and organizational results there should be concern for the transfer of learning from campus to workplace. One case study of the design of a program for the public services highlighted the application of thinking based on an adult education process model. The teaching and learning process was planned to culminate in a final stage called “skill application,” which was equated to on-the-job implementation of principles and skills (Faerman et al., Citation1987). The important point in this case was that the transfer of learning from the program to the work situation was a formal and planned step in the process and not just something left to happen haphazardly.

McCracken et al. (Citation2012) make the point in their paper that the climate of the public sector affects training effectiveness, affecting both participation in training and transfer of learning to the workplace. If this is correct, the political and administrative context of the civil service may well affect the results of educational programs for civil servants. Arguably, a key aspect of that context is not only factors such as the munificence of budgets and the nature of public management reforms and transformations, which are big picture contextual factors, but also the immediate context of an individual civil servant created by a line manager. We hypothesize that line managers could encourage civil servants to take up educational opportunities and could facilitate the application of learning to the workplace during and after an educational program (Kravariti et al., Citation2022). Consequently, we argue that interactions between an individual civil servant and their line manager may be an important contextual factor.

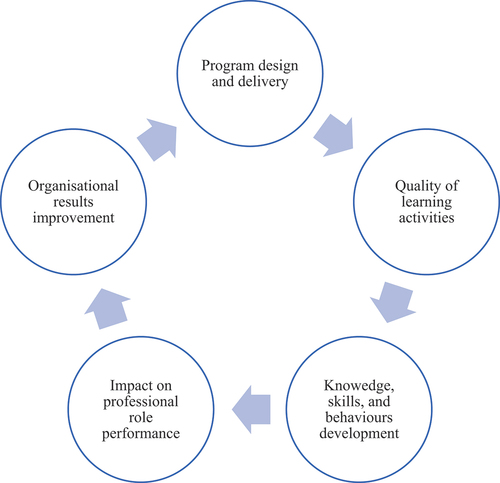

Building on these remarks, in , we present a conceptual framework based on a process model of formal education of leaders for the civil service and translation of learning into organizational results. We can imagine purposeful strategies to strengthen this process, including strategies to deepen student engagement in learning activities, to enhance line managers’ work in supporting the transfer of learning to the workplace, and to refine and improve program evaluation and design.

The Bahrain master in public management

In 2016 the Bahrain Institute of Public Administration (BIPA) launched a new program, the Master in Public Management (MPM) with the “objective of building capacity to achieve unprecedented levels of quality in delivering public services, in line with the development aspirations of Bahrain and the region.” The Master in Public Management (MPM) had aims that included developing “government leadership equipped with the tools to make informed decisions and develop policies.” It was a “building block” in the National Program for the Development of Government leaders.

The government leadership program, promoted under the sponsorship of the heir to the throne, a key figure in the Bahrain “reform project,” included a number of leadership development programs, including the MPM. Applicants admitted into these programs were fully sponsored, and admission into the program was perceived as a success in itself. The political visibility of the program made it very attractive to those who wanted to progress in their careers.

Another distinctive feature of the MPM is that it was offered by the Institute of Public Administration of Bahrain (BIPA), though technically hosted by the local university for compliance and academic credentialing purposes. This was significant in that it enabled the program to be more innovative than would be possible in the traditional academic culture. BIPA, which also delivered the other programs of the national leadership program, ensured that program delivery was targeted toward improvement of public administration practice in the country.

The Bahrain Institute of Public Administration partnered with Aix Marseille University, Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA) of France, the University of Bahrain, and Tamkeen to assemble the capabilities and resources needed to deliver the MPM concept. Three of the partners, Aix-Marseille University, ENA, and the BIPA, had full control over the program curriculum development, student admission, teaching and learning, and all other aspects of delivery (see for a full breakdown of the program content). Successful students graduated with a master’s degree awarded by Aix-Marseille University as well as a professional certification in public management jointly delivered by ENA and BIPA. These qualifications added to the high levels of motivation and commitment displayed by students.

Table 1. Schedule of components for the program.

Selection criteria for entry to the program

Students were selected by their employer for enrollment on the program. Given the large number of applications to the program typically only one in four applicants were admitted. The process of selecting students took place at different levels as outlined below.

First, applicants with outstanding academic credentials were pre-selected for interview. There was no restriction on the academic field of specialization with applicants spanning diverse fields such as engineering, social science, management, and medicine.

Secondly, those who had gone through the first sift were asked to write a motivation letter or a statement of purpose.

Thirdly, alongside the letter of motivation, applicants were also asked to submit a recommendation letter from their direct supervisor. This was intended to ensure that applicants had the full support of their managers as well as giving a sense of their current performance in the workplace. In a few exceptional cases outstanding applicants, as perceived by the selection committee, were admitted despite not having the recommended support of their line manager.

Finally, all applicants were interviewed. Each interview lasted between 15–30 minutes. The interview committee consisted of representatives of the two French institutions and one representative of the host institution, the Institute of Public Administration of Bahrain. During the interviews, applicants were probed about their professional ambitions; how they saw the MPM contributing to that; their potential for leadership in the workplace and their vision and understanding of the issues at stake in their work environment and the public sector in general.

Combined with objective factors including their Grade Point Average and English tests scores, the selection process ensured the intake of quality applicants. At the same time, the pool of interviewees was kept relatively large (about half the applicants that applied were interviewed), to ensure gender balance and representation across all public institutions. The latter was sometimes difficult to ensure as some public institutions had better applicants than others. Nonetheless, a minimal representation of the “less performing” institutions was ensured.

Methodology

The research employed a mixed methods approach to data collection using an online survey of students, a focus group with students, 6 semi-structured interviews with managers, and 2 semi-structured interviews with stakeholders. All data collection took place in 2022. The individual and group interview data was used to inform the development of survey questions and was also helpful in the theoretical sensitivity we brought to the interpretation of our survey data. As such the survey of those who had studied, or were still studying, on the program was the main data collection effort. The students contacted totaled 123 from five student cohorts (see ). Future research may explore the perceptions of supervisors and managers in more depth.

Table 2. Survey respondents.

The survey was designed following the qualitative stage of the research and was then piloted with a small group of people and the wording of questions adjusted to ensure they were easy to understand. The survey was then distributed via online survey platform Survey Monkey to all former and current students on the MPM. Participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous as explained to all respondents in the introduction to the survey. Conducting the survey via an online platform ensured that no student felt compelled to participate and so the ethical principles of informed consent and participant anonymity were maintained.

In total the survey received 51 responses. Therefore, the overall response rate was slightly over 41%. The biggest response came from those starting the MPM in 2019, with 22 responses out of 24 students. Presumably this reflected the fact that they had completed the MPM recently—in 2021, whereas earlier cohorts had completed the MPM up to 4 years ago.

Findings

Five key findings have been identified from analysis of responses to the online survey. The first key finding relates to the importance of knowledge, skills, and behaviors (functional competencies) as learning outcomes. The second is the extent to which management and leadership are addressed in a program, whether as knowledge, skills, or behaviors. The third is the explicit attention given to student engagement with the learning process. The fourth is the transfer of learning. The fifth is the role of the university educators in the delivery of educational relevance and the implications of their role for what might be the complementary roles of students and line managers. We now cover each of these key findings in turn.

Performance of functional competencies

Respondents to the survey were asked whether they were better able to fulfill the requirements of the functional competencies of their current job because of their learning and development on the MPM. Most gave positive answers to this question (with positive defined here as rating it 3 or 4 on the scale of 0 to 4). We can offer some corroboration of this positive perception by the respondents. Specifically, we checked for a correlation between the respondents’ perceptions on this matter and their perception of whether they were performing better at their current job because of what they had learnt by studying on the MPM. Bivariate analysis revealed that these two perceptions were strongly correlated (r = 0.67).

A bivariate correlational analysis shown in revealed many correlations between the eight competencies. There seemed to be a grouping of three of them in what we might for call a “Leadership Cluster” – Strategic Outlook, Driving Change, and Leading People. Professionalism seemed to be at the heart of another cluster; it had correlations with Developing Self (r = 0.72), Customer Service Orientation (r = 0.62), and Management of Resources (r = 0.57).

Table 3. Bivariate correlations of impact on performance of competencies for current job.

Curriculum and skills typology

Respondents were asked about their perceptions of increased skills because of the MPM. The skills in question were management skills, leadership skills, research skills, problem-solving skills, and digital skills. While all these skills were correlated with each other, it was clear that the strongest association was between leadership and management skills (r = 0.73). One possible inference is that leadership and management are not as distinct as we might imagine. Another is that the difference between the skills of management and the skills of leadership are “fuzzy” both in practice and in the minds of the people who have been or are MPM students. Gaining Leadership skills from the MPM was also moderately correlated with the gaining of “Problem Solving Skills” (r = 0.58). See .

Table 4. Bivariate correlations of skills.

University campus-based education and the transfer of learning

The data on the five skills were aggregated in a simple additive index of “skills gained from the MPM.” All five skills were weighted equally. Analysis showed that the development of skills because of the MPM was associated with gains in self-confidence (r = 0.74). We are inclined to see the gains in confidence being a consequence of skill development on the MPM. One deduction from this is that programs for civil servants can usefully focus on skill development to improve civil service capacity and build individual self-confidence.

When a bivariate analysis was conducted of this skills index with perceptions of better fulfillment of the requirements of the functional competencies of their current job because of learning and development on the MPM, the two were correlated (r = 0.67). That is, the people who reported gaining the most in the five skills were the ones who tended to say that they were better able to fulfill the requirements of the functional competencies of their current job because of their learning and development on the MPM. We can suggest that the MPM led to learning and development in key skills and that these skills were used to meet competencies expectations and do their current jobs better.

We had also asked students about whether they were better at performing their current job and whether they had positively impacted on their unit or department because of what they had learnt on the MPM. On the latter question most gave high ratings by way of answer, suggesting the program was perceived as being of direct benefit to the civil service. In fact, bivariate correlations showed the existence of the strongest correlations between skills and performance of job competencies, between performance of job competencies and being better at the job, and between being better at the job and positive organizational impact. See .

Table 5. Bivariate correlations relating to the impact of the MPM on organizational Results.

As is often remarked, correlations do not by themselves establish causality, but the results can be used to suggest a hypothesis consistent with the correlations. We hypothesize that the benefits of studying on the MPM flowed in a particular causal sequence, which was as follows. The MPM increased skills causing better performance of important competencies required by the job, which in turn led to people doing their jobs better, that ultimately had a positive impact on organizational results at the Unit or Departmental level.

Our hypothesis is shown in .

The following quotes from two of the line managers suggest that individuals had developed and improved as a result of taking the program. It seemed that their educational experiences had fostered their ability to be leaders and to bring about change in their units or departments:

So, leadership was an important skill that I can see he has developed and the way he is starting to manage resources in terms of people and team, and here also comes the improvement on the way he started collaborating with the teams and getting people engaged on the projects. … he has developed a lot from the past, because I can compare his skills before he joined the program and how he used to [be], … Therefore, I say these types of skills, I can see major developments and improvement. (Line Manager 1)

I will say [the member of staff] before the program was always the one who brings ideas, … and he wants us to implement it in the job, and he comes to my office, and these are just very brilliant ideas. And that’s good for me. It’s music for my ears because I can see he is doing a lot of research and he is studying about it. But then [the member of staff] after the program [MPM], I like the way he changed because he continued bringing the ideas, but then he started, putting it, I would say in a public service framework, and he started seeing the consequences and evaluating the idea. Before he used to come and say, this is a good idea, why don’t we implement it? Then we tell him because we don’t have this and we don’t have this and if we do this, it will not comply to our law. So, it is not realistic. But then, after going through the program [the MPM], I like the way he starts to think. He started bringing an idea, and he has already filled in the gaps - having looked at different perspectives and how we can resolve this [problem] as a good idea, given that this would be running under Bahrain law. He stopped bringing to me a raw idea and [instead he shows] how we will fit it in to the government’s [agenda/circumstances]. Because not every new idea is a good idea. It must be customized. That’s the way he changed his thinking. I will say it’s a higher maturity level that he has reached. I like this, and this help me to promote him to get a higher position. So, he is looking at all new ideas that come from the government, he is successfully being able to put them into a framework that will be workable in the public sector. So, this is the way that I think he changed for me, and I like it. [Emphasis added using italics.] (Line Manager 2)

It is clear from their remarks that these line managers were very satisfied with the results of the MPM. With Line Manager 2 it seems that the program had created greater maturity in the student and turned an embryonic quality of “proactivity” that could (we can imagine) enthusiastically create ideas but now was backed up by an ability to assess situational factors and constraints (like the law) and develop implementable ideas in line with government policy. Moreover, Line Manager 2 directly identified these changes as causes for the promotion of the student to a higher position in the civil service.

We might describe these changes in the person as personal development. In fact, the data on the impact of the MPM on the students’ personal development correlated with the skills index referred to above (r = 0.67). And we found three factors that were, when added together, moderately associated with the MPM’s impact on personal development. These were: student perceptions that the MPM was a well-designed program, student engagement with the MPM, and line managers helping the students apply their learning on the MPM to their work. The definition of student engagement we used in the survey was as follows: by “engagement” is meant that the student had a high level of motivation to do well on the MPM, that they felt intellectually stimulated by their experience of learning on it, and that they invested as much time and effort as possible in studying on the MPM.

When we created a program impact index, we found this correlated with the impact of the MPM on personal development. The impact index was constructed using three survey items familiar from the analysis above. The impact of the MPM was measured by adding together ratings of students’ fulfilling the requirements of the functional competencies of their current job, performing their current job better, and having a positive impact on the results of their unit or department. The bivariate correlation with the impact of the program on personal development was moderate (r = 0.61).

In summary, we suggest that personal development could be to a large degree a matter of skills development and that personal development because of the MPM explains quite a lot of the variations in the MPM’s impact (as measured by the MPM Impact Index) (see ). We propose that the transfer of learning from campus to the civil service occurs, in part, because of the skills that they have learnt, and the personal development students achieve.

Discussion and conclusions

The immediate significance of the findings of the Bahrain civil service case study are simply stated. The master’s program had helped with identifying talented people in the Bahrain civil service and had a significant impact on their personal development and their skills. The findings were consistent with the conclusion that the program’s successes in terms of personal development and skill development had positive effects on performance of job competencies and effects on the results of the organizational units and departments employing the students. This was a very satisfactory outcome: not only had the program been adding to the pool of future leaders in Bahrain’s civil service, but also it had been positively impacting on civil service results in the here and now.

From the analysis of the survey findings, we are suggesting that personal development and skill development provided a very special link in the cause-and-effect chain. The educational program, we think, provided an experience that was important for the personal development of students that then prepared them to operate in a way that fitted the competency framework, enabled better job performance, and created positive contributions to unit and departmental results. We speculate that civil service competency frameworks need skillful and self-developing individuals rather than blind and unthinking obedience by civil servants.

We highlight three practical implications we have inferred from these findings that may serve to inform learning and teaching practice, particularly across other Gulf States.

The first implication suggested here is the need to continue shifting the emphasis from the programs of the past in which it seemed that students “getting knowledge” (e.g., via books and lectures) was the essential purpose of university courses, toward more emphasis on personal development and skills development (e.g., cognitive, professional, and personal skills). Of course, knowledge transmission or acquisition remains important, especially sound knowledge. But programs should make more room for attention to personal and skill development (and even attitude development). This continuing shift of emphasis implies a strategic redefinition of the role of those taking part in learning and education as students and teachers.

The second implication is that it is probably a mistake for educational programs to displace educational learning outcomes and replace them by a list of functional or vocational competencies drawn directly from an official civil service competency framework. It is doubtful whether university academics are best placed to carry out assessments of functional competencies. And the findings above point to them being better spending their time on facilitating personal development and skill development. That said, there is an option for academics and civil service managers to partner in degree-apprenticeship collaborations, or other new programs, in which assessment of functional competencies are devolved or delegated to practitioners (experienced line managers in the civil service) who would take the lead on the assessment of vocational competencies, and who might do this assessment through a process resembling an appraisal interview (e.g., looking at actual job performance). Such a collaboration implicitly recognizes the role that line managers can play in helping students transfer learning on educational programs to the workplace.

The third implication relates to the content of programs. We think it is probably a mistake for programs for civil servants to concentrate only on leadership, or only on management. The skills of leadership and management were found to be strongly correlated, and an index of skills including them was correlated with fulfillment of functional competencies, and thereby connected to better job performance. So, it might be suggested we need to de-differentiate (to a degree) our conceptions of leadership roles and management roles, even though it is often suggested that leadership and management are completely different functions. In practice, we may need civil servants to skillfully blend leadership and management in their job performance, and possibly deploy both in complex and agile ways. Speaking speculatively, maybe a capability for leadership combined with a capability for management needs to be nourished and reproduced by leadership practice (demonstrating a strategic outlook, driving change, and leading people) and a professional practice that is partly oriented to a public value perspective (consisting of customer service and resource management) and partly to a commitment to self-development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction http://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2024.2320019

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ian C. Elliott

Ian C. Elliott is a Senior Lecturer in Public Policy and Administration at the University of Glasgow, a Fellow at the Municipal Research Lab, North Carolina State University and co-convenor of the EGPA Permanent Study Group IX Teaching Public Administration. His research interests include community empowerment, organizational change and the strategic state. He is co-editor of the Handbook of Teaching Public Administration and co-Editor-in-Chief of Public Administration and Development.

Paul Joyce

Paul Joyce is an Associate at the Department of Public Administration and Policy, University of Birmingham, a Visiting Professor in Public Management at Leeds Beckett University, and Publications Director of the International Institute of Administrative Sciences (IIAS). His most recent publications include Strategic Management and Governance: Strategy Execution Around the World, Strategic Management for Public Governance in Europe (coauthored with Anne Drumaux); and Strategic Leadership in the Public Sector.

Sofiane Sahraoui

Sofiane Sahraoui is Director-General of the International Institute of Administrative Sciences (IIAS) and was the recipient of the Jose Edgardo Campos Collaborative Leadership Award from the World Bank Group in 2017. He is a founding member of the MENAPAR (Middle East & North Africa Initiative for Public Administration Research) network.

References

- Abramson, M. A. (2021, October 20). How government is failing public servants. Government Executive. Retrieved October 26, 2021, from https://www.govexec.com

- Australian Public Service Commission. (2019). State of the service report 2018-19. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.apsc.gov.au

- Biygautane, M. (2023). Pre-requisites for infrastructure public-private partnerships in oil-exporting countries: The case of Saudi Arabia. Public Administration and Development, 43(3), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.2021

- Civil Service Human Resources. (2018, November 6). Civil service competency framework 2012-2017. Update. Retrieved June 12, 2023, form https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/436073/cscf_fulla4potrait_2013-2017_v2d.pdf

- Common, R. (2008). Administrative change in the Gulf: Modernization in Bahrain and Oman. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852308089902

- Elliott, I. C., Robson, I., & Dudau, A. (2021). Building student engagement through co-production and curriculum co-design in public administration programs. Teaching Public Administration, 39(3), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739420968862

- Faerman, S. R., Quinn, R. E., & Thompson, M. P. (1987). Bridging management practice and theory: New York State’s public service training program. Public Administration Review, 47(4), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/975311

- IAEA. (2020). The competency framework: A guide for IAEA managers and staff. Retrieved June 12, 2023, form https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/18/03/competency-framework.pdf

- Kravariti, F., Tasoulis, K., Scullion, H., & Alali, M. K. (2022). Talent management and performance in the public sector: The role of organisational and line managerial support for development. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(9), 1782–1807. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.203226

- Mahmood, M., Weerakkody, V., & Chen, W. (2019). The influence of transformed government on citizen trust: Insights from Bahrain. Information Technology for Development, 25(2), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2018.1451980

- McCracken, M., Brown, T. C., & O’Kane, P.(2012). Swimming against the current: Understanding how a positive organisational training climate can enhance training participation and transfer in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 25(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551211244124

- UK Government. (2014, April 23). Civil service: Training and development. Retrieved June 12, 2023, form https://www.gov.uk/guidance/training-and-development-opportunities-in-the-the-civil-service