ABSTRACT

Internet-delivered, therapist-guided, self-help programs are novel ways to deliver psychotherapeutic interventions adapted from established therapy models. Such programs can be easily accessed online and may offer an important treatment option for patients who struggle with barriers to seeking out and engaging in face-to-face psychotherapy, including depressed adolescents. While there are evidence-based Internet-delivered self-help programs based on cognitive-behavioral therapies (i.e. ICBT) for adolescent depression, a program based on psychodynamic principles (i.e. IPDT) has so far been lacking. In this article we describe the IPDT program developed within the ERiCA project, which has so far been evaluated in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We further provide a case example from one of the trials to illustrate the treatment process and therapeutic interaction in detail. Given the novelty of the approach, we will particularly highlight and discuss how a psychodynamic understanding of adolescent development and depressive dynamics as well as affect-focused treatment principles inform the treatment, including the therapist’s role, tasks, and choice of interventions. The potential implications and utility of IPDT for regular clinical practice are elaborated as well as potential research directions for the future.

In the last decades there has been an upsurge of interest in developing and researching Internet-delivered interventions targeting various mental health issues (Andersson et al., Citation2019). The Internet may be used in many different ways to deliver psychological treatments (Barak et al., Citation2009), including, for example, the provision of face-to-face psychotherapy sessions through a video communication application such as Skype or Zoom. However, the most researched format of Internet-delivered psychological interventions is “guided self-help programs” (Andersson et al., Citation2019). In such programs, principles derived from an established psychotherapy model are translated into a self-help format that is accessed through an online digital platform. The therapist’s role is to provide practical and technical support, as well as feedback on exercises through text messaging and/or chat sessions. Most programs developed so far have been based on cognitive-behavioral therapies (often referred to as Internet-delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; ICBT), but programs based on psychodynamic principles (i.e., Internet-delivered Psychodynamic Therapy; IPDT) have also been developed and tested with promising results in adult populations (Lindegaard et al., Citation2020).

While Internet-delivered self-help programs can function as an important alternative for patients who live in remote places, they may also be particularly appealing to patient populations that are reluctant to seek traditional face-to-face treatments, or in places where services are lacking. One such population is depressed adolescents who may avoid seeking help due to perceived stigma and feelings of shame, desire to be self-reliant, and difficulties recognizing symptoms of mental health disorders (Gulliver et al., Citation2010; Radez et al., Citation2021). In today’s world, many adolescents use the Internet for social interaction on a daily basis (Anderson et al., Citation2023). Therefore, a treatment that is delivered on their “home turf,” stresses their own agency and does not involve direct face-to-face contact, may lower some of the barriers to engage.

While there are ICBT programs targeting adolescent depression the results so far have been mixed (e.g., Christ et al., Citation2020; Ebert et al., Citation2015; Eilert et al., Citation2022). Even when found effective (e.g., Topooco et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), a substantial proportion of patients do not respond; thus, further development and testing of treatment alternatives is warranted. Since IPDT programs have previously proven to be effective in treating depression in adult populations (Johansson et al., Citation2012, Citation2013), and face-to-face psychodynamic therapies have been effective with this population (Goodyer et al., Citation2017), an IPDT program adopted for adolescents offers a promising option.

The ERiCA project (EaRly Internet-delivered interventions for Children and Adolescents) was initiated with the primary aim of developing and testing an online therapist-guided self-help program based on psychodynamic principles (e.g., IPDT) for adolescent depression. So far, two RCTs have been conducted in the project in Sweden. Lindqvist et al. (Citation2020) compared an 8-week IPDT program (described in detail below) to an online support condition. The study involved 76 adolescents and results indicated that IPDT led to large and significant reductions in self-reported depressive symptoms as well as significant effects for anxiety, emotion regulation and self-compassion. In the second trial, IPDT was compared to a previously established ICBT for adolescent depression in a rigorous randomized non-inferiority trial (Mechler et al., Citation2022). Here, IPDT was found to be non-inferior to ICBT at end of treatment with no significant differences between treatments on any outcome in the intent-to-treat analyzes. A smaller pilot study (n = 23) has also been carried out in the United Kingdom, indicating feasibility and effectiveness of the program in a cultural context outside Sweden (Midgley, Guerrero-Tates, et al., Citation2021).

In this article, we aim to describe the IPDT treatment program that was developed within the ERiCA-project. We will start by briefly describing the underlying theoretical model of adolescent depression and the affect-focused treatment principles that informs the treatment. We will then provide an overview of the eight treatment modules included in the program and describe the central guidelines for therapist interventions in feedback messages and chat sessions. Lastly, we will provide a case example obtained from the ERiCA study to illustrate the treatment process and the text-based therapeutic interaction in more detail. This way, our hope is that the reader will get a “feel” for how this novel application of psychodynamic psychotherapy for adolescents “looks” and “works” in practice. Since this type of treatment may challenge traditional views of what psychodynamic psychotherapy is (Midgley et al., Citation2023; Papadima, Citation2023) we will particularly highlight and discuss the therapist’s role and why we believe a psychodynamic understanding of adolescent depression and central treatment dynamics is crucial in this type of treatment.

A developmentally-informed psychodynamic model of adolescent depression

The underlying theoretical model guiding the treatment in ERiCA may be regarded as an integration of basic emotion (e.g., Panksepp, Citation2010) and attachment theories within a psychodynamic conflict theory framework (see Mechler, Citation2023, for further details). Central to the model is the notion that depressive symptoms reflect maladaptive processing of mixed, conflicted emotions triggered in close relationships. Having mixed feelings in attachment relationships is part of normal development and as long as there are “good enough” experiences with caregivers, the individual should develop adaptive capacities to integrate, understand and regulate (i.e., “mentalize”) their affective and relational experience. According to this model, significant disruptions in attachment bonds, however, may trigger strong emotions and maladaptive defense mechanisms to ward off negative experiences of pain, sadness, anger and guilt about anger (A. Freud, Citation1936). Intense feelings of anger toward attachment figures may be particularly difficult to process and lead to the turning of anger inwards as well as the development of a “punitive super-ego” (Abraham, Citation1927; S. Freud, Citation1957), making the individual vulnerable to depressive reactions in later relationships. Further, the normal developmental process during adolescence will inevitably trigger conflicts around a sense of belonging and separation and evoke both grief and (healthy) aggressive feelings toward family members. Thus, the adolescent’s normal striving for individuation may itself trigger (unconscious) guilt due to unresolved rage from past attachment disruptions, which may lead to the individual resorting to maladaptive defenses that create symptoms and prevent healthy emotional development.

Affect-focused treatment principles

The main treatment principles in the IPDT program follow from the model of development outlined above, and are primarily derived from affect-focused, experiential psychodynamic therapies (e.g., Abbass, Citation2015; Fosha, Citation2000; McCullough, Citation2003). These principles may be summarized by using Malan’s (Citation1995) triangular schemes, i.e. the “Triangle of conflict” and “Triangle of persons” (see ). The triangle of conflict depicts how unconscious feelings and impulses generate anxiety, which leads to the use of defenses to ward-off feelings and impulses in order to keep them out of conscious awareness. However, rigid and excessive use of defenses will lead to negative consequences in the long run, including the generation and maintenance of anxiety and depressive mood, as well as hampering our ability to grow and mature. In addition, the triangle of persons describes how maladaptive defensive patterns that originate with past attachment figures, such as parents and siblings, may repeat in current relationships, such as partners, friends, and teachers, as well as with the therapist when attachment-related, complex feelings are triggered.

In line with the underlying theory outlined above, the overall aim of the IPDT program when working with depressed adolescents is to decrease emotional avoidance and to increase awareness, experience, and adaptive expression of emotions. Throughout the treatment, participants are encouraged to become aware of their own defenses, notice and regulate high levels of anxiety, and gradually approach previously warded-off feelings related to situations that trigger depressive mood. The final part of the program contains material on how to recognize pervasive relationship patterns in terms of maladaptive dependency or independence (Blatt, Citation2008) and how to communicate and express previously avoided affects in close relationships.

The hypothesized mechanisms of change include: 1. increased capacity for self-observation, to regulate anxiety and understand patterns of emotional avoidance that lead to and maintain depressive symptoms (e.g. development of “insight” and/or “mentalization”), 2. the breaking of maladaptive patterns of anxiety and defenses in order to directly experience and integrate conflicted, attachment related, complex feelings (e.g., “corrective emotional experiences”), 3. the development of a more balanced, mature and compassionate “super-ego” to replace harsh and punitive introjects, and 4. the “freeing-up” of the adolescent’s own inner resources in order to test out and find new ways of relating to self and others without interruption from old, repetitive, relational patterns.

Overview of the treatment program and the therapist’s role in IPDT

The treatment program is accessed through a secure Internet platform (Vlaescu, et al., Citation2016) and consists of eight separate modules provided over 10 weeks. Each module is focused on specific aspects of the treatment model described above and contains brief psychoeducational texts, vignettes, and animated videos followed by exercises that participants complete and send to their therapist during the week. Compared to existing IPDT programs for adults, texts in the present treatment material are substantially shorter and easier to read. The content of each module is summarized in and is also described in more detail in relation to the case report below.

Table 1. Treatment modules.

The therapist’s role in the program is to communicate with the adolescent via the secure online platform using written feedback messages and weekly 30-minute individual text-based chat sessions. Feedback messages are typically written within 24 hours after a participant has completed an exercise while chat sessions are, as far as possible, scheduled to be held on a regular time once a week. The principles guiding therapist’s focus and feedback in messages and chat interactions followed a detailed treatment manual developed for the project. Some of most central intervention strategies are described below.

Assisting with content-related issues

One of the main therapist tasks is to support the participant in following through the treatment program. This includes providing technical support when necessary but also assisting their participants in understanding the material in the module. Although adapted for adolescents, the treatment material may still be challenging for some participants and the therapist may need to adapt and clarify content.

Focusing on symptoms (or presenting problems) and building a collaborative alliance

Since the treatment is short, the therapists need to stay focused on the present problems in the young person’s life, including the overt symptoms of depression that led them to seek treatment (Busch et al., Citation2012). This includes inviting the participant to actively work together with the therapist to try to understand what may have triggered current symptoms. The therapist typically encourages the participant to provide specific examples, and then helps the adolescent establish links between every-day events in their relationships, conflicted emotions and symptoms of depression. Whenever possible and appropriate, therapists are also instructed to refer back to relevant parts of the self-help program to enhance learning as well as establishing links between chat sessions and the overarching treatment principles. This way, the therapist provides a road map for the treatment and instills hope that, with hard mutual work, the program will be helpful for the adolescent in terms of their own goals.

Working with the triangle of conflict

In line with the treatment principles outlined above, the IPDT therapist focuses on elucidating how emotions trigger anxiety that leads to the use of defenses (i.e., the triangle of conflict). Therapists are instructed to constantly listen for and try to understand symptoms as manifestations of underlying emotional conflicts. Normally, this work begins with focusing on a relational trigger to unconscious affect. Therapists encourage the adolescent’s exploration and use the triangle in a didactic manner, to help the participant see how underlying emotions may have become coupled with anxiety, leading to the use of defenses that in the long run perpetuate depression.

Identification and regulation of affects

Through the treatment material, the young person is taught to differentiate bodily symptoms of anxiety and bodily symptoms of basic emotions. As many of the participants suffer from dysregulated affects and dysregulated anxiety, the therapist may need to put special emphasis on the difference between internally experiencing emotions versus acting out. Helping the young person differentiate between triggers, underlying feelings, anxiety and defenses (such as harsh self-criticism) are some of the affect-focused interventions often used by the IPDT-therapist.

Identification and regulation of dysregulated anxiety

When participants describe symptoms of high anxiety, emphasis is put on identifying and regulating anxiety. This is typically done by using “recaps,” i.e. helping the young person to reflect on their emotional experiences by recapitulating the triangle of conflict. By doing this, the therapist establishes causality (i.e. feelings provoke anxiety which in turn leads to defensive maneuvers) and helps differentiate the corners of the triangle. This should lead to an increased capacity for self-observation and thus help regulate dysregulated anxiety. Participants are also encouraged to try and remain with the physical experience of anxiety and not try to escape it by using defenses.

Work on defences

Even if there is one module dedicated specifically to defense work, it is a core part of the treatment and present in most of the modules. Further, most therapist interventions in messages and chat sessions can be classified as defense identification and clarification, while direct confrontation of defenses (although not prohibited) is less common. One important aspect of clarification is helping the adolescent see the cost of their defenses, i.e., how defenses are linked to relational problems and symptoms of depression, and to motivate them to let go of defenses (i.e., to experience the underlying emotions instead). Special emphasis is placed on super-ego defenses, i.e., defenses of self-criticism, and how defenses function as a way to avoid mixed feelings toward significant others and how this is linked to depressive states.

Interpersonal focus

Therapists are further instructed to elucidate maladaptive, recurring patterns of relating, including stereotypical expectations of responses from others. Given that the interaction is text-based, the transference is used more cautiously than in some face-to-face PDT protocols. As the case below illustrates, the therapists are instructed to be mindful of how the patient relates to the therapist in their written communications, and in particular to pay attention to the impact of ending treatment. The role that the participant assigns the therapist is often discussed in supervision and sometimes addressed directly, for example when potential maladaptive relational patterns are activated in chat sessions. Further, therapists are instructed to be particularly aware of how conflicts around intimacy and autonomy may influence the relationship between them and the young person. For example, in order not to “get caught” in in the role of an overly worried or pressuring adults in the adolescent’s life orbit, therapists are instructed to pay close attention to the adolescent’s own will and choice to engage in the treatment. Lastly, issues around separation, including from the therapist, are actively brought into focus toward the end of the treatment program.

The case of Zoë

In order to provide a more in-depth description of the program and how the treatment may unfold, we present the case of “Zoë”Footnote1 below. Zoë was a participant in the second trial of the ERiCA-project (Mechler et al., Citation2022) and was in many ways a typical participant in the project. She was 18 years old and had suffered from depression for more than a year. She presented with suicidal thoughts, but expressed no suicidal intentions. She had seen a therapist on a couple of occasions, but did not find it very helpful and therefore ended treatment prematurely. In her application to the project, Zoë reported that she did not want face-to-face therapy as her earlier experience had not been positive. She also expressed a will to be self-sufficient and did not want to inform her parents about entering treatment. Zoë further mentioned having been bullied and a victim of a sexual assault. She fulfilled criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD) and her self-report measures indicated moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms and comorbid anxiety. Zoë was guided through the treatment by her study therapist, “Elena,” a Master’s student in the psychologist program, who attended weekly supervision groups led by an experienced clinical psychologist and supervisor, specializing in affect-focused dynamic therapy. Supervision was based on the written communication between participants and their respective therapists. The supervisor would primarily help therapists conceptualize the participant’s suffering in terms of inner emotional conflicts and maladaptive relationship patterns using Malan’s triangle. Since the entirety of treatments are already “transcribed,” all members of the supervision group can easily follow the clinical processes as they unfold over time. Therapists were generally encouraged to bring up cases that they thought were particularly challenging or where they had a hard time understanding the process.

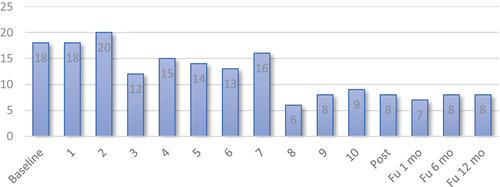

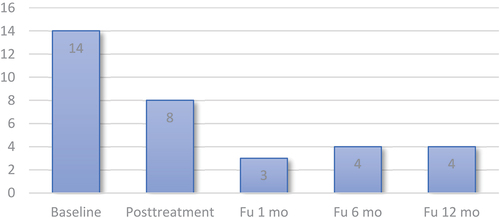

Zoe’s case can be seen as typical of the approximately 50% of young people who demonstrated a positive response to treatment in the ERiCA study. Zoë’s self-report ratings of anxiety and depression at the end of the study are displayed in below, showing a clear decrease over time. Her depression scores did not indicate complete remission at end of treatment, but as she started on relatively elevated scores, her improvement was large, and maintained at follow-up assessments six and twelve months after treatment ended.

Module 1: “Feelings – our inner guides”

The first module introduces the theory of depression that informs the ERiCA program. Brief psychoeducational texts and videos describe the interplay between emotions and attachment needs throughout our development. The triangle of conflict (called “the triangle of feelings” in the program) is introduced and it is described how defenses and anxiety may block feelings triggered in close relationships (i.e., creating “affect phobias”) leading to and maintaining depressive mood. The first module ends with self-ratings of affect phobias and exercises where the participant is encouraged to set their own goals for the treatment and start reflecting on situations that trigger depressive mood.

In her exercises, Zoë wrote about wanting to be close to others, but having trouble really trusting she would be treated fairly, and her fear of being alone. Her self-ratings indicated anxiety and defenses in response to both anger and sadness. For instance, she recognized trying to distract herself and withdrawing interpersonally when feeling sad and she would often start crying when she was in fact feeling angry. Furthermore, she did not feel comfortable with setting boundaries. She wrote about being brought up in a family where few emotions were accepted and having to deal with emotions on her own. Zoë expressed that she found module 1 interesting as it gave her new insights into the underlying dynamics of her depression.

Elena responded by validating that Zoë seemed to have had limited emotional support from her family and friends. Elena also highlighted the adaptive aspects of anger and sadness, clarifying the long-term price of avoiding them. She also highlighted the positive effects of adaptive use of both anger and sadness, whilst stressing the fact that this was something that most people needed to work on and that the coming chapters would address this further. In the first chat session, Zoë expressed that she felt much more comfortable writing to someone rather than sitting face-to-face talking.

Module 2: ”The voice of depression”

The second module introduces the concept of the “inner critic” and how it can be activated when conflicted feelings are triggered in close relationships. Basic notions of shame (and its opposite, self-compassion) are introduced and related to depressive mood and symptoms. Further, the notion of “projection of the super-ego,” e.g., how we may attribute our own self-critical thoughts to others and consequently avoid openness, is presented. The exercises of this module focus on building the participant’s capacity for self-observation by identifying self-critical, self-attacking and self-neglecting thoughts and habits. Particular emphasis is on helping the participants differentiate between old destructive ways of relating to self from more healthy parts of the ego.

In module 2, Zoë reported having frequent thoughts about herself as ugly, weak, unlovable, not good enough and worthless. She also described situations where her inner critic would get triggered, such as when she would not get the highest grade in school or when she did not perform in sports, but also in situations of interpersonal conflict. Zoë described that she was unable to overcome conflicts unless they were completely resolved, which led to her violating her own boundaries. Zoë also noticed that when the inner critic increased in strength she would feel more depressed. At the end of module 2, Zoë was given a recorded exercise focusing on self-compassion. She wrote to Elena about doing the exercise: “It felt good listening to the exercise and repeating some of the more compassionate sentences. I felt especially drawn towards the sentence: ‘I want to be able to forgive myself, even when I have done things I regret.’ I do not know why. It is not like I do a lot of things I regret, but it spoke to me somehow.”

In her feedback on the tasks, Elena responded to Zoë’s exercises by commending her on her hard work. Furthermore, she clarified the function and the cost of the harsh voice of the super-ego: “You have done an amazing job with this week’s exercises! I can imagine this chapter was quite challenging, but you have started to see how your inner critic is linked to your depression and that you are very hard on yourself a lot of the time. By building the capacity to observe the inner critic you will also start to see when it is triggered (particular situations, relationships, etc.) and in doing so we will also be able to explore what emotions are being covered up by this harsh inner voice.”

That week Zoë entered the chat session full of emotions as she had had a conflict with her mentor at school. After having been told off by the mentor, Zoë felt completely depleted and depressed. She also criticized herself for not being compassionate toward herself. She described the situation to Elena, explaining how she had been wrongfully accused for something she did not do, and how unfair it all felt. Elena inquired into how Zoë might have felt toward the mentor, which led to the following exchange:

“I was in shock. I know he can be a bit hot tempered, but we’ve always had a good relationship. I have never seen this side of him. It felt like an attack on me. I felt really angry, but I tried hiding it as best I could. But he would not let go and after the meeting he just kept badgering me about it, saying I was rude. At that point I started crying, not because I wanted to, but it was as if my body was on autopilot.”

“And right now?”

“Right now I feel hurt. I’m angry.”

Elena then validated Zoë’s feelings, but also clarified the function of the defense:

“Ok, you describe it well and it is really good that you are able to be in contact with your anger. It is really common that we start crying when we feel angry. It is like the tears cover up the anger.”

Zoë immediately started reflecting on how she was scared of her anger, and she connected this to earlier experiences. But she also showed some signs of becoming overwhelmed:

“Yes, there has never been any room for my anger. I haven’t been allowed to express it. So, when I feel angry it’s replaced by tears. Perhaps it’s something that I have learnt over the years. Something I was taught as a child. But I don’t know how to fix it! I was really scared in the situation with my mentor. I wanted to say that it was unfair, but I got really sad by what he said to me. Instead I turned the anger on myself, and blamed myself. Even if I know I didn’t do anything wrong. Oh, I don’t know. It is all so complicated.”

Elena picked up on Zoë’s distress, but rather than encouraging Zoë to approach her anger directly at this early point in treatment, Elena opted to strengthen the alliance by clarifying the function and cost of the defense and pointed to their mutual work towards a positive treatment goal:

“I see. It sounds like your anger has been replaced by tears instead. By gradually getting closer to your anger you’ll get to know an important part of yourself that you need access to. Your anger is trying to tell you something. With increased access you won’t have to rely on your inner critic to the same extent, as the inner critic is anger that your turn on yourself.”

Zoë very quickly takes the message to heart:

“This is completely new to me, what if I have never let myself feel this? I have always buried it and it’s resulted in me feeling sad and down.”

Elena then further underlined how the defenses created Zoë’s depressive reactions whilst validating sad feelings associated with these new insights:

“I can really understand that it is painful. You’ve paid a high price for covering up your anger with tears. But you and I can work together, to break this pattern. Your feelings are valuable and so are you.”

Module 3: ”Anxiety – our body’s alarm system”

The third treatment module focuses on anxiety, including the experience and function of anxiety from a relational-developmental perspective. The participant is taught how to differentiate objective fear of external threats from anxiety related to internal threats, such as thoughts and feelings. The participant is also taught how to distinguish optimal and too-high levels of anxiety (Abbass, Citation2015). Further, the notion that anxiety may signal that threating underlying feelings are being activated is explained and related to the triangle of conflict. Module exercises focus on identification and regulation of anxiety through self-observation, breathing exercises, noticing the triangle of conflict (e.g. so-called “recapping” or “stop and rewind”) and practicing labeling feelings.

In module 3, Zoë reported multiple symptoms of anxiety, such a muscle tension, nausea and some signs of cognitive perceptual disruption. She also reflected on how she often repressed feelings. Zoë identified that several relationships (with her sister, her best friend and her mentor) were associated with strong feelings, anxiety and severe self-attacks. Furthermore, Zoë identified that anger and shame were often experienced at the same time. When completing the chapter tasks, Zoë wrote: “I get distraught when I realize how badly I treat myself when I’m sad. I blame myself for almost everything, even though I don’t deserve it. I feel some kind of pressure over my chest when I think about this and I feel my shoulders tensing up when I try to experience these feelings.”

Elena responded to what was written in the exercises by validating Zoë’s feelings of sadness and pain in connection to making insights into the self-destructive mechanisms underlying her depression. She also elaborated on the triangle of conflict, underlining how emotions can feel scary: “I think you are making some key insights into how your depression works, how these conflicts in close relationships trigger anger and how you deal with this anger by criticizing yourself. This seems to be driving your depression. There seems to be loads of feelings underneath that you are ‘prohibited’ from feeling. Do you think that is the case too?”

Further, Elena encouraged Zoë to continue to reflect on and approach the underlying emotions: “Continue to take a step back and reflect on what is happening to you. What are you feeling, how are you experiencing your anxiety and what is the inner critic saying to you? If you want to, you can start exploring your anger and how you experience it physically. Remember, you don’t need to act on it, just explore and feel it inside you. I know it’s hard, but you’re also strong. Speak soon, Elena.”

In the chat session which followed this, Elena and Zoe continued to explore the issues which has arisen while completing the tasks.

Module 4: “Defenses – strategies we use to avoid our feelings”

In the fourth module, the participant is more thoroughly introduced to the psychodynamic notion of defenses. The aim is to help the participant understand their function, as well as the short- versus long-term consequences. In particular, the material focuses on how maladaptive defensive patterns may lead to and maintain depressive symptoms. In a series of exercises, the participant is encouraged to identify their own typical defensive patterns and reflect on long-term consequences of them.

In module 4, Zoë recognized that she used several defenses, such as intellectualization, rationalization and denial (through distraction). Further, in completing the exercises Zoë reflected that, already as a child, she felt she was expected be self-reliant. This had now become internalized, leading her to distance herself from others when in distress. One way of doing this was to become focused on others’ problems, which Zoë described as ”hiding in other people’s issues and trouble”. By doing this she would still have close relationships, but without having to disclose her own pain. However, she was aware that this came at a price and in the last exercise she wrote: “I would like to be comfortable letting down my guard. I want to form closer relationships where I don’t feel the need to hide myself.”

Elena responded to Zoë’s exercises by praising her hard work and her ability to recognize old patterns of relating to herself and others. She highlighted the cost of putting one’s own needs to the side and how emotions may accumulate over time. Furthermore, she clarified loneliness as part of the cost of avoiding emotions. Once again, the chat session was used to further explore what had come up from the exercise.

Module 5: “Searching for our inner guides – make space for your emotions”

The fifth module teaches basic emotions theory including the typical visceral experience of different feelings. The module further contains several experiential exercises that encourages the participant to turn their attention inward to identify, observe and accept their inner experience of feelings and impulses without acting on them. The participant is encouraged to notice any anxiety and/or defenses that may be triggered during the exercises, as well as notice any associations and/or memories that may spontaneously emerge when feelings are experienced. Lastly, the participant is also encouraged to observe how feelings, anxiety and defenses are triggered in everyday situations and write about them to their therapist.

In the exercise at the end of module 5, it became clear that both anger and sadness seemed to be fused with anxiety in Zoë’s case. When describing anger Zoë said: “I become tense in my shoulders and neck and I clench my fists. There’s like a fire inside of me. But then it changes into hopelessness, tears are streaming down my face and I kind of feel confused”. She also described sadness: “I get a sick feeling to my stomach and my heart starts racing. I have trouble breathing and it feels like someone is choking me and I just start to panic.”

Elena responded by urging Zoë not be too hard on herself, reminding her that acceptance of emotions takes time. Furthermore, in the chat session she helped her separate the defense of hopelessness from the experience of anger. She reflected on the clenched fists and inquired into whether Zoë was aware of any impulses that came with the clenched fists, whilst at the same time again reminding her that they were not talking about acting on impulses: “Experiencing strong emotions in your body, like letting your anger roar inside, will not hurt anyone. Giving all your emotions space, exploring them and letting yourself experience them is actually a way to process your emotions. This will enable you to start thinking about how you then want to handle them in real life.”

Module 6: ”Particularly challenging feelings – facing anger, grief and guilt”

Module 6 builds on the previous module and focuses on feelings that often are particularly challenging (i.e., anger, grief and guilt). The participant is taught to differentiate between the experiencing of emotions internally vs. acting out and how the latter is typically a defensive (rather than adaptive) form of feeling and/or the result of excessive anxiety. The material contains information on the importance of mixed and complex emotions in close relationships and the difference between healthy guilt versus debilitating shame. The module further contains an expressive writing exercise designed to help the participant approach and integrate complex feelings related to distressing relational events.

In her feedback on module 6, Zoë reported that she identified with a clinical vignette in the module text: “It is like I’m reading about myself. It gets to me because I haven’t processed what I’ve been through – I never took care of any of my feelings. Just like in the vignette, I do everything to avoid being angry with people.” Zoë also described how she withdrew from people around her when she got sad. Her inner experience of sadness was clearly enmeshed with high levels of anxiety.

In her expressive writing task, Zoë described a traumatic event a few years back. She described how she experienced anger, but also how easily it was turned back on herself: “How could I be so stupid!?.” Elena responded to Zoë’s exercises clarifying the link between feelings, anxiety and defenses: “You write beautifully about your grief, but it is almost like the anger has been encapsulated to protect the people you love. To me it sounds like your grief is also associated with a lot of anxiety. The bodily symptoms you’re describing (blurry vision, sweaty palms, etc.) are all signs of anxiety. And you distance yourself from your grief as a defense. I think this may be something we need to work on together because it sounds like you carry a lot of sadness within you too, and repressing sadness can also make us depressed.”

Module 7: “Togetherness and independence – which role do you play in close relationships?”

This module explains how our social development involves a constant negotiation between our needs for “relatedness” and “self-definition” (Blatt, Citation2008) and how over-reliance on either of the polarities may be connected to avoidance of emotions in relationships. In the module exercises, the participant is encouraged to identify their predominant way of relating in close relationships and reflect on how they wish their relationships were different. The participant is further encouraged to challenge their habitual interpersonal patterns by going against them in order to develop a more mature and balanced approach in relationships. In addition, the participant is encouraged to reflect upon their perceived barriers to communicating to others about their needs and feelings. Given their predominant personality configuration (dependency or self-definition) participants are offered different techniques on how to break their maladaptive relationship patterns.

In completing module 7, Zoë reported that she highly identified with emphasizing togetherness at the expense of independence. She also expressed a wish to be able to express more of her emotional needs whilst not being afraid of being turned down or experienced as “not good enough.” Elena validated Zoë in that it often feels hard being open and assertive with others who you feel dependent upon: “For some, the fear of losing others is so strong that they don’t feel comfortable in expressing hardly any concerns or demands in a relationship.”

In the chat session Elena brought up the forthcoming end of treatment: “You’ve been talking about your separation anxiety and now, you and I have about three weeks left of treatment. I want you to know that it’s really common to react to the treatment ending with strong and often mixed feelings. If you feel disappointed, angry, sad or frustrated with me we could actually use this as an opportunity for you to explore and express these feelings in a safe environment. It is up to you, but I would be open to it.”

”I have a hard time with endings. I have become attached to you and now it’s hard saying goodbye. I want to work with my feelings and I’m motivated in doing so, but we will soon go our separate ways and … I get really sad when good relationships end.”

Module 8: ”The road ahead – sharing feelings in close relationships”

The last module in the program focuses on appropriately expressing affects in close relationships. The participant is encouraged to take an active stance in communicating their feelings and needs adaptively. The module further contains exercises to identify situations that may trigger setbacks in depressive symptoms and encourages the participant to reflect on how such situations could be handled to avoid relapse. Lastly, the participant is encouraged to summarize and evaluate what they have achieved during treatment and reflect on the feelings evoked by the treatment ending.

Working with this chapter, Zoë expressed gratitude toward Elena: “The treatment was a lot better than I had anticipated. It surpassed my expectations by far! I am so grateful for all the help you’ve given me. I don’t know how I could ever express what this has all meant to me. I feel really close to you. I’ll miss our chat sessions. It was tough in the beginning. I think that I have buried my feelings for so long, and it is inevitable that it will be tough opening up for feelings that I’ve tried keeping away. You’ve helped me in understanding feelings and how to experience and accept them. It’s not as hard anymore.”

In the chat session Zoë described a situation where she was able to stand up to her former mentor and speak her mind. She also mentioned that she had started talking more openly with her best friend and that their relationship had improved as a result of this.

Even though Zoë had now done all of the 8 modules, she and Elena had two more weeks with chat sessions before treatment ended. However, right before their ninth chat session, Zoë cancelled because of the flu. She also cancelled their replacement time which meant that they only had one chat session left as the study was ending. This gave Elena a hunch that there might be issues associated with treatment ending. When Zoë got self-critical in the final chat session, Elena focused on exploring mixed feelings in the transference:

We have previously talked about the treatment ending and that it felt tough for you. How do you feel about that now?

I think about it almost all the time and this has not been a good week for me. I feel that I didn’t make the most of the treatment, that I messed up the ending. I should have done so much more!

That sounds tough, but it also sounds to me like it might be the inner critic talking? We both know you have worked really hard through the treatment.

I never feel happy with myself, no matter how hard I work I always feel that I should have done more.

I am wondering, do you think there might be some negative feelings toward me or toward the treatment? That you sort of push away by criticizing yourself? From my perspective it would be absolutely normal to feel disappointment and frustration at the end of treatment. Especially since you have really opened up to me. And then we have to end treatment anyway! There could be mixed feelings there, both positive and negative? What do you think?

Yeah, possibly. But at the same time, I knew what I signed up for. That the treatment was short and that I would potentially feel that the ending of treatment would be tough.

Sure, you knew, but you still applied which I think was a good thing. But what feelings are you experiencing toward me as treatment is ending?

I feel happy that you believe in me. I have never had this kind of contact with anyone really, and I feel sad that it is ending as I have finally learned to talk openly about what’s going on inside of me.

Thank you for telling me. Both positive feelings and some sadness because our relationship ends today. I wonder if there’s also some frustration? We just got started and now it is ending?

Yeah, why is the treatment so short!?

The anger which Zoe expressed in this final chat session can be understood as a defense (displacement), where anger is directed at “the treatment” rather than the therapist. In this instance, Elena felt that there was too little time left in the chat to continue pursuing angry feelings in the transference. Instead of inviting more feelings, she focused on helping Zoë observe and reflect on her feelings, increasing her self-observing capacity.

Right, and you have every right to feel frustrated about that.

This feels so much worse than I thought it would. Sure, I thought that it would feel tough, but this affects me so much more.

It seems that a lot of feelings are stirred up within you, and that is so understandable. You’ve really opened up to me and shared your feelings, thoughts and fears. And now it is over. That is sad. I’m sad about it too! I think it will be important for you to experience these emotions. Both the happiness, sadness and the frustration about how short the treatment was and if there was something I could have done better.

That sounds reasonable. I need to practice dealing with separations. Thank you for everything. I really mean it. This was a huge step for me to take, and it was a step in the right direction.

Thank you, that means a lot and I will be thinking about you.

The final message

After treatment had ended, Zoë was informed that Elena would read everything that she would write (exercises, messages) for another two weeks, but that she would not be in a position to reply (due to the study protocol). Almost two weeks after the treatment had ended Zoë sent a message through the platform: “Hi Elena. It has almost been two weeks since I last heard from you. I’ve been missing you and it’s been tough managing my life without you by my side. But I’m much better at accepting my emotions now and I try to embrace both positive and negative feelings. Sometimes I find myself doubting if I can really do it, but I know it’s important to me. I want to keep moving forward. […] I sometimes find myself thinking about you. You know so much about me, and yet I know almost nothing about you. What your life is like and what you’re doing. I miss hearing from you and I miss talking to you.[…] When life feels tough I’ll need to remind myself about our work and what we did together. You’ve almost become like a bigger sister to me and will continue to find strength in the fact that you believe in me. […] I will never forget you and everything you’ve done for me. I’m grateful for the time we had together. Best wishes, Zoë”

Discussion

The results of the two RCTs in Sweden indicates that the IPDT program developed in the ERiCA project is an effective treatment for adolescent depression. This adds to previous research supporting the efficacy of psychodynamic therapies for depressed young people (Midgley, Mortimer, et al., Citation2021). Thus, besides ICBT, IPDT is an evidence-based alternative for depressed adolescents, especially those who may not be able to, wish for or have difficulty accessing services directly with a therapist face-to-face. In some cases, it could also be a first experience of getting help, which could increase the chances of a young person going on to seek further help in the future, if needed.

In this article we have introduced the structure and content of the IPDT program, including the underlying theoretical model and general guidelines for therapist interventions in messages and chat sessions. We further presented the case of Zoë as an illustration of how the treatment process may unfold in a fairly successful case. Clearly, not all participants in our studies showed the same progress as Zoë, although response and remission rates (about 50% and 40% respectively) have been quite impressive given the brief intervention. Zoë is representative of our samples in additional ways; she was a young female who struggled with pervasive symptoms of depression and anxiety, there was a history of conflict in her family of origin as well as a negative experiences in peer relationships, and she had a previous experience of face-to-face treatment that she described as negative. Quite early in the treatment, she experienced that the program material “spoke to her” and she developed a strong alliance with her IPDT therapist. Qualitative research on IPDT further underscore these findings, with a recurring theme highlighting the central role of a strong therapeutic relationship for treatment effectiveness (Lindqvist et al., Citation2022; MacKean et al., Citation2023). Further, although there were indications of ambivalence, she completed most of the exercises and engaged in the chat sessions.

There were also several aspects of her interaction with her IPDT therapist, Elena, that are illustrative of the therapist’s role, tasks and interventions in the program. For example, Elena repeatedly gave encouraging feedback on Zoë’s work in the exercises. Since the interaction between therapist and participant is completely text-based, with a lack of non-verbal opportunities to demonstrate engagement and interest, the IPDT therapist needs to be more explicitly validating and supportive. In face-to-face meetings, validation and support are often conveyed with short utterances, tone of voice, facial expressions and body language. Therefore, therapists in IPDT are instructed to be explicit in conveying care and support than they would normally be in face-to-face work (meaning expressions such as “you’ve worked really hard,” “I am impressed with your work,” or “I’ve been thinking about you”). Empirical work has identified some of the ways in which the therapist in IPDT with depressed adolescents actively works to help establish a therapeutic alliance (Mortimer et al., Citation2022).

Further, Elena was active in helping Zoë focus on her symptoms and explore the emotional content of specific situations that triggered depressive mood and anxiety. She repeatedly used the triangle of conflict to help Zoë make sense of her reactions and encouraged her to reflect and approach troubling situations and feelings when anxiety was regulated. This active, symptom-oriented, and sometimes explicitly didactic therapeutic approach, may seem at odds with a traditional “listening and reflecting” therapist stance in psychodynamic psychotherapies. However, given the limited time-frame for the treatment, it is crucial that the IPDT therapist is able to be “active in a psychodynamic way” (Katzman & Coughlin, Citation2013), i.e. by encouraging self-observation, pointing out possible defensive operations, exploring emotional experience without suggesting any particular form of action. Although the treatment modules involve some didactic content and exercises, the IPDT therapist is further instructed to refrain from “taking the lead” in chat sessions and rather encourage, support and follow the adolescent’s decision on what to focus on.

Some support for the theoretical underpinnings of the treatment model has been found as two studies examining the week-by-week process identified that increases in emotion regulation preceded improvement in the following week’s depression rating (Lindqvist et al., Citation2023; Mechler et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, psychodynamic interventions in the chat sessions have been found to be related to outcome, where more use of PDT techniques predicted decreases in depressive symptoms week-by-week (Leibovich et al., Citation2022).

One psychodynamic technique used less in IPDT than in many other PDT formats is the interpretation of transference; but that is not to say that transference work is entirely absent from the process. As described above, transference is interpreted mainly when it becomes an obstacle to treatment, or when there is clear indication of “super-ego projections” onto the therapist (most commonly, this is characterized by the participant becoming worried that the therapist dislikes them or are disappointed in their work with treatment). Since interactions are short and not in person, transference work needs to be used carefully and the therapists are instructed to primarily work with the participant’s emotional reactions in extra-therapeutic relationships. However, one situation where the therapeutic relationship is explicitly discussed is at the end of treatment, where the participant is encouraged to express feelings toward the therapist, both positive and negative. While we do not expect all participants to become attached to the therapist in this brief online treatment format, it was clear that it did happen for some participants, such as Zoë. The termination process gave rise to separation issues that Elena picked up on and explicitly invited Zoë to explore so they could briefly be “worked through” in the final chat sessions.

We suspect that the Internet-delivered treatment format described in this article will likely seem far removed from ordinary practice for many psychodynamic clinicians. For example, only communicating through asynchronous text messages and 30-min weekly online chats differs sharply from regular face-to-face meetings in a therapist’s office. Some psychodynamic practitioners have also questioned if the development of a therapeutic relationship characterized by sufficient emotional depth, including transferential aspects, is even possible via the Internet, as contact is usually anonymous, asynchronous, and lacking non-verbal elements of communication (e.g., Papadima, Citation2023; Roesler, Citation2017). For example, Roesler (Citation2017) considered internet-delivered approaches “[…] more suitable for cognitive-behavioural treatments where psychotherapy is largely based on conveying helpful information” (p. 374).

In contrast, we believe the research and case presented in this article suggest that psychodynamic treatment principles can be adopted and used in this format. We further believe that a strong therapeutic relationship can be, and often is, developed and that it is crucial for a successful outcome. Further, the developmental task of separating from parental figures and becoming more independent is a frequent theme in psychotherapy with adolescents and young adults and experiencing lack of autonomy and/or the therapist as too authoritative can easily lead to discontinuation of therapy (Binder et al., Citation2011; O’Keeffe et al., Citation2019; von Below, Citation2020). In IPDT, the participant has more control over their participation in treatment, as they can choose when, how and where they partake in it, as well as having control over what they share with their therapist. This can be interpreted as them having more opportunities to regulate closeness and distance to the therapist, which may be experienced as favorable for many adolescents (Lindqvist et al., Citation2022; MacKean et al., Citation2023).

At the same time, we do not suggest IPDT can replace face-to-face psychotherapy. Rather, this form of treatment should be seen as complementary to ordinary services by offering an easily accessible, first-line treatment for young people who may be reluctant or have difficulty coming to regular outpatient services. IPDT can be an important “first step” and by offering this treatment we might lower barriers to seeking further treatment when needed (Gulliver et al., Citation2010). In fact, a recurrent feedback we have received from the participants in our studies was that the IPDT program made it seem less scary to seek treatment in the future.

Future directions

To date, there are studies supporting the efficacy of IPDT treatment as well as shedding light on some of the treatment processes as well as experiences by the participants, and the acceptability of adapting the intervention to a different cultural context has been established. These results need to be replicated by other research teams. In order to facilitate further studies on IPDT the present article was written to illustrate clinical principles and processes in this treatment. As noted above, the case used in this article to illustrate the treatment process was a fairly successful one, but not untypical of those who benefitted from participating. In order to further elucidate the processes necessary for change, successful cases could be compared to less successful ones. Furthermore, we are currently working on questions regarding suitability for IPDT; i.e., are there any predictors of treatment response? Do some patient characteristics moderate outcome? And can treatment be tailored in order to suit a larger group of young people?

As of now, IPDT for adolescents has primarily been evaluated in efficacy trials. This means that participants have been self-referred. The impact of this is unclear, but it could mean that participants who are more positively inclined toward text-based treatment have applied and that results and clinical processes might look different for less positively inclined young people. However, far from all participants rated that they would prefer text-based treatment before conventional treatment delivered face-to-face. Future research should also assess the effectiveness and ease of implementation of the treatment when delivered in routine care settings. Text-based treatment could also serve as a method for reaching clinical populations that are often challenging to reach and treat, particularly due to language barriers. Text-based materials can be readily translated, and the utilization of an interpreter or translation tool could be used when writing up the therapist feedback. This could enhance the outreach to important groups of young people that are often left without sufficient care, such as refugees or ethnic minorities.

Another avenue to pursue would be to test effects of parental involvement. In our trials, parents have not been part of the treatment. There have been no self-help materials developed for parents and parental support has not been included. This is something that could be developed and added benefits evaluated.

Further, the IPDT model developed in ERiCA is essentially a transdiagnostic treatment model and may thus also be effective in treating other problems, including anxiety disorders. This is seen with adults (Johansson et al., Citation2017; Mechler et al., Citationin press), and the existing studies on depressed adolescents suggest that comorbid anxiety is also being treated effectively (Lindqvist et al., Citation2020; Mechler et al., Citation2022).

Some research questions have already been partially answered, psychodynamic therapy techniques seem to be predictive of change (Leibovich et al., Citation2022), the therapeutic alliance and improvements in emotion regulation also seem to act as mechanisms of change (Lindqvist et al., Citation2023; Mechler et al., Citation2020) and qualitative data points to the centrality of the therapeutic relationship and that this is being experienced as a genuine and emotionally important relationship (Lindqvist et al., Citation2022; MacKean et al., Citation2023; Mortimer et al., Citation2022). Of course, results from future studies may lead to several adjustments of the content and/or principles guiding the treatment, but we believe that the IPDT approach offers real opportunities for a wider range of young people to benefit from psychodynamic therapies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

J. Mechler

J. Mechler, PhD, is a researcher at Stockholm University in Sweden. He is also a registered clinical psychologist currently working with short-term psychodynamic therapies in a private setting, where he treats young people as well as adults. Together with Karin Lindqvist, Jakob has developed and evaluated the internet-delivered psychodynamic therapy described in the current study. He is also involved in clinical research on other psychodynamic models. Jakob regularly teaches training clinicians in subjects such as affect-focused dynamic therapy, psychiatric assessment, and research methodology.

K. Lindqvist

K. Lindqvist, PhD, is a clinical psychologist and researcher at Stockholm University. She has developed and researched IPDT and is also involved in research on psychodynamic treatment in other settings, as well as in the development and teaching of mentalization-based treatment for children. She teaches child psychotherapy, developmental psychology, research methods, and mentalization, among other things. She works clinically with children and families, as well as adults.

B. Philips

B. Philips, PhD, is professor in clinical psychology at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, and leader of the research group Stockholm University research group for Process and Outcome in Psychodynamic therapies (SU-POP). He is also a licensed psychologist and licensed psychotherapist. He was principal investigator for a clinical trial of mentalization-based treatment (MBT) for concurrent borderline personality and substance use disorder, as well as three randomized controlled trials of internet-delivered psychodynamic treatment (IPDT) for adolescent depression.

N. Midgley

N. Midgley, PhD, is Professor of Psychological Therapies for Children and Young People in the Research Department of Clinical, Educational, and Health Psychology at University College London. He is director of the Child Attachment and Psychological Therapies Research Unit (ChAPTRe) at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families / UCL. He has played a key role in the development of mentalization-based treatments for children and families. As well as continuing studies into the treatment of adolescent depression, his current research focuses primarily on interventions for children, including the development and evaluation of the Reflective Fostering Programme.

P. Lilliengren

P. Lilliengren, PhD, is Assistant Professor at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Sweden, where he conducts research and teaches in the Advanced Psychotherapist Program. He is also a licensed psychotherapist by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and a trained psychodynamic supervisor. Besides his position at Stockholm University, he maintains a private psychotherapy practice in Stockholm, specializing in Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP).

Notes

1. All participants in ERiCA gave their written informed consent for use of their self-report data, written responses to exercises as well as chat messages for research and dissemination purposes by the research team. For the purpose of preserving participant confidentiality, identifiable aspects of the case have been altered. The ERiCA project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority on Aug 14, 2019 (reference number 2019–03023).

References

- Abbass, A. (Ed.). (2015). Reaching through resistance: Advanced psychotherapy techniques (1st ed.). Seven Leaves Press.

- Abraham, K. (1927). Notes on the psycho-analytical investigation and treatment of manic-depressive insanity and allied conditions. In A. Strachey & D. Bryan (Eds.), Selected papers on Karl Abraham (pp. 137–156). Karnac. (Original work published 1911).

- Anderson, M., Faverio, M., & Gottfried, J. (2023). Teens, social media and technology 2023. Pew Research Center.

- Andersson, G., Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Rozental, A., & Carlbring, P. (2019). Internet‐delivered psychological treatments: From innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20610

- Barak, A., Klein, B., & Proudfoot, J. G. (2009). Defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7

- Binder, P.-E., Moltu, C., Hummelsund, D., Sagen, S. H., & Holgersen, H. (2011). Meeting an adult ally on the way out into the world: Adolescent patients’ experiences of useful psychotherapeutic ways of working at an age when independence really matters. Psychotherapy Research, 21(5), 554–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.587471

- Blatt, S. J. (2008). Polarities of experience: Relatedness and self-definition in personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11749-000

- Busch, F. N., Milrod, B., Singer, M. B., & Aronson, A. C. (2012). Manual of panic focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, extended range. Routledge.

- Christ, C., Schouten, M. J., Blankers, M., van Schaik, D. J., Beekman, A. T., Wisman, M. A., Stikkelbroek, Y. A., & Dekker, J. J. (2020). Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e17831. https://doi.org/10.2196/17831

- Ebert, D. D., Zarski, A.-C., Christensen, H., Stikkelbroek, Y., Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Riper, H., & Wallander, J. L. (2015). Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. Public Library of Science One, 10(3), e0119895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119895

- Eilert, N., Wogan, R., Leen, A., & Richards, D. (2022). Internet-delivered interventions for depression and anxiety symptoms in children and young people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 5(2), e33551. https://doi.org/10.2196/33551

- Fosha, D. (2000). The transforming power of affect: A model for accelerated change (1st ed.). Basic Books.

- Freud, A. (1936). The ego and the mechanisms of defense (The Writings of Anna Freud, Vol. 2). International Universities Press.

- Freud, S. (1957). Mourning and melancholia. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund freud (pp. 1–14). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1917).

- Goodyer, I. M., Reynolds, S., Barrett, B., Byford, S., Dubicka, B., Hill, J., Holland, F., Kelvin, R., Midgley, N., Roberts, C., Senior, R., Target, M., Widmer, B., Wilkinson, P., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): A multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30378-9

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 113(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

- Johansson, R., Björklund, M., Hornborg, C., Karlsson, S., Hesser, H., Ljótsson, B., Rousseau, A., Frederick, R. J., & Andersson, G. (2013). Affect-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression and anxiety through the internet: A randomized controlled trial. PeerJ, 1, e102. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.102

- Johansson, R., Ekbladh, S., Hebert, A., Lindström, M., Möller, S., Petitt, E., Poysti, S., Larsson, M. H., Rousseau, A., Carlbring, P., Cuijpers, P., Andersson, G., & Bruce, A. (2012). Psychodynamic guided self-help for adult depression through the internet: A randomised controlled trial. Public Library of Science One, 7(5), e38021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038021

- Johansson, R., Hesslow, T., Ljótsson, B., Jansson, A., Jonsson, L., Färdig, S., Karlsson, J., Hesser, H., Frederick, R. J., Lilliengren, P., Carlbring, P., & Andersson, G. (2017). Internet-based affect-focused psychodynamic therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 54(4), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000147

- Katzman, J., & Coughlin, P. (2013). The role of therapist activity in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2013.41.1.75

- Leibovich, L., Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Mortimer, R., Edbrooke-Childs, J., & Midgley, N. (2022). Unpacking the active ingredients of internet-based psychodynamic therapy for adolescents. Psychotherapy Research, 33(1), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2050829

- Lindegaard, T., Berg, M., & Andersson, G. (2020). Efficacy of internet-delivered psychodynamic therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 48(4), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2020.48.4.437

- Lindqvist, K., Mechler, J., Carlbring, P., Lilliengren, P., Falkenström, F., Andersson, G., Johansson, R., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Dahl, H.-S. J., Lindert Bergsten, K., Midgley, N., Sandell, R., Thorén, A., Topooco, N., Ulberg, R., & Philips, B. (2020). Affect-focused psychodynamic internet-based therapy for adolescent depression: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3), e18047. https://doi.org/10.2196/18047

- Lindqvist, K., Mechler, J., Falkenström, F., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., & Philips, B. (2023). Therapeutic alliance is calming and curing – the interplay between alliance and emotion regulation as predictors of outcome in internet-based treatments for adolescent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 91(7), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000815

- Lindqvist, K., Mechler, J., Midgley, N., Carlbring, P., Carstorp, K., Neikter, H. K., Strid, F., Von Below, C., & Philips, B. (2022). “I didn’t have to look her in the eyes”—participants’ experiences of the therapeutic relationship in internet-based psychodynamic therapy for adolescent depression. Psychotherapy Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2150583

- MacKean, M., Lecchi, T., Mortimer, R., & Midgley, N. (2023). ‘I’ve started my journey to coping better’: Exploring adolescents’ journeys through an internet-based psychodynamic therapy (I-PDT) for depression. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 49(3), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2023.2173271

- Malan, D. H. (Ed.). (1995). Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics (2nd ed.). Butterworths.

- McCullough, L. (Ed.). (2003). Treating affect phobia: A manual for short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

- Mechler, J. (2023). Beyond the blank screen: Internet-delivered psychodynamic therapy for adolescent depression: Evaluating non-inferiority, the role of emotion regulation, and sudden gains [ PhD dissertation]. Department of Psychology, Stockholm University. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-218837

- Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Carlbring, P., Topooco, N., Falkenström, F., Lilliengren, P., Andersson, G., Johansson, R., Midgley, N., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Dahl, H.-S. J., Sandell, R., Thorén, A., Ulberg, R., Bergsten, K. L., & Philips, B. (2022). Therapist-guided internet-based psychodynamic therapy versus cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescent depression in Sweden: A randomised, clinical, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Digital Health, 4(8), e594–e603. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00095-4

- Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Falkenström, F., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., & Philips, B. (2020). Emotion regulation as a time-invariant and time-varying covariate predicts outcome in an internet-based psychodynamic treatment targeting adolescent depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00671

- Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Magnusson, K., Ringström, A., Daun Krafman, J., Alvinzi, P., Kassius, L., Sowa, J., Andersson, G., & Carbring, P. (in press). Guided and unguided internet-delivered psychodynamic therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Npj Mental Health Research. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-024-00063-0

- Midgley, N., Guerrero-Tates, B., Mortimer, R., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Hajkowski, S., Leibovich, L., Martin, P., Andersson, G., Vlaescu, G., Lilliengren, P., Kitson, A., Butler-Wheelhouse, P., & Philips, B. (2021). The depression: Online Therapy Study (D: OTS)—A pilot study of an internet-based psychodynamic treatment for adolescents with low mood in the UK, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 18(24), 12993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412993

- Midgley, N., Mechler, J., & Lindqvist, K. (2023). Response to Maria Papadima’s commentary on MacKean et al. (2023) and Midgley et al.’s (2021) papers about an internet-based psychodynamic treatment. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 49(3), 465–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2023.2277752

- Midgley, N., Mortimer, R., Cirasola, A., Batra, P., & Kennedy, E. (2021). The evidence-base for psychodynamic psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A narrative synthesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 662671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662671

- Mortimer, R., Somerville, M. P., Mechler, J., Lindqvist, K., Leibovich, L., Guerrero-Tates, B., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Martin, P., & Midgley, N. (2022). Connecting over the internet: Establishing the therapeutic alliance in an internet-based treatment for depressed adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(3), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221081193

- O’Keeffe, S., Martin, P., Target, M., & Midgley, N. (2019). ‘I just stopped going’: A mixed methods investigation into types of therapy dropout in adolescents with depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 75. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00075

- Panksepp, J. (2010). Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/jpanksepp

- Papadima, M. (2023). Commentary on the paper by Molly MacKean et al.: ‘I’ve started my journey to coping better’: Exploring adolescents’ journeys through an internet-based psychodynamic therapy (I-PDT) for depression. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 49(3), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2023.2258531

- Radez, J., Reardon, T., Creswell, C., Lawrence, P. J., Evdoka-Burton, G., & Waite, P. (2021). Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4

- Roesler, C. (2017). Tele‐analysis: The use of media technology in psychotherapy and its impact on the therapeutic relationship. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 62(3), 372–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12317

- Topooco, N., Berg, M., Johansson, S., Liljethörn, L., Radvogin, E., Vlaescu, G., Nordgren, L. B., Zetterqvist, M., & Andersson, G. (2018). Chat- and internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy in treatment of adolescent depression: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 4(4), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.18

- Topooco, N., Byléhn, S., Dahlström Nysäter, E., Holmlund, J., Lindegaard, J., Johansson, S., Åberg, L., Bergman Nordgren, L., Zetterqvist, M., & Andersson, G. (2019). Evaluating the efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy blended with synchronous chat sessions to treat adolescent depression: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e13393. https://doi.org/10.2196/13393

- Vlaescu, G., Alasjö, A., Miloff, A., Carlbring, P., & Andersson, G. (2016). Features and functionality of the Iterapi platform for internet-based psychological treatment. Internet Interventions, 6, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2016.09.006

- Von Below, C. (2020). “We just did not get on”. Young adults’ experiences of unsuccessful psychodynamic psychotherapy – a lack of meta-communication and mentalization? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01243