?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article investigates the role of trust/reputation and parasocial influence in influencing purchase intention among consumers of baby products who frequent Polish parenting blogs. Empirical data was collected by survey (n-1050) of blog readers to construct a model to assess the impact of trust/reputation and parasocial influence. Factor analysis was used to create scores which were then tested using a multiple binary logistic regression model. The research found that while both trust/reputation and parasocial influence were important determinants of consumer purchase intention, trust was significantly more important to baby product consumers than parasocial influence. Additionally, parasocial influence was a more important indicator of purchase intention among younger respondents (under 23 years of age) than those 23 years and older. Additionally, readers who have read blogs for longer are more likely to trust these sources, perceiving them to be reputable. Hence, bloggers should aim to foster long-term relationships with consumers when endorsing products that demand higher trust, such as baby products.

Introduction

Parents seeking product purchasing information and advice frequently use blogs written by fellow parents (Charlesworth Citation2015; Mintel Citation2022). “Mommy blogging” has become a major online space for marketers to reach and penetrate existing communities (Wiley Citation2018). Parents actively seek out information from other parents when choosing products, making blogs powerful sites for social commerce that meet both informational (Han and Kim Citation2017) and social needs (Holiday, Densley, and Norman Citation2021). The global baby care market is one of high economic value, estimated at $67.3 billion (Bedford Citation2021). This makes online communities of parents potentially valuable consumer communities and is supported by studies that have found influencers to be effective brand advocates (Booth and Matic Citation2011; Lee and Eastin Citation2021; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo Citation2021; Shan, Chen, and Lin Citation2020).

Parent bloggers offer a particularly powerful platform for brands wishing to reach parents as they have power and influence on consumer opinion (Kerr et al. Citation2012). Parent blogs are good sources of support for parents of young children as they produce content that recommends products while focusing on the experience in use (Holiday, Densley, and Norman Citation2021). Bloggers post their opinions about products and in doing so they combine both commercial information and knowledge from brands with a personal narrative that is interpreted by these influencers for their audience (Vanninen, Mero, and Kantamaa Citation2023). There is precedence in the literature to refer to bloggers under the wider term of influencers (Abidin Citation2015; Enke and Borchers Citation2019; Reinikainen et al. Citation2020). For this research we use the terms inter-changeably as the bloggers in this research—those who host personal websites and share their everyday experiences (Hsu et al. Citation2013)—are also influencers—those who influence followers by maintaining a presence on social media (Dhanesh and Duthler Citation2019).

Being “known” by consumers is key to bloggers’ influence. Consumers are thought to be more likely to make a purchase based on a personal recommendation from someone they know or with whom they are familiar (Han and Kim Citation2017; He et al. Citation2017; Szolnoki et al. Citation2018). The perception of similar social standing, personality, or personal factors is important for users to feel influencer recommendations are relevant to them (Kim, Park, and Kim Citation2022; Lee and Lee Citation2014). Users are more likely to share or act on information if they feel they know the influencer (Chiu et al. Citation2014), especially if the influencer is perceived as credible and trustworthy (Dhun and Dangi Citation2023). Following influencers who are perceived to be like them, results in consumers feeling strong ties to the influencer (Perez-Vega, Waite, and O'Gorman Citation2016). Li and Du (Citation2011) suggest that bloggers’ closeness to the market gives them a privileged position as bridges to potential consumers while Wang, Huang, and Davison (Citation2021) highlight how followers feel beholden to the help and advice they receive. Influencers’ posts present them as relatable advisors through intimate self-disclosure, and this fosters intimacy, authenticity, and relatability to the blogger or influencer (Childers and Boatwright Citation2021; Leite and Baptista Citation2022; Hendry, Hartung, and Welch Citation2022). Unlike celebrities, influencers are keen to be perceived as ordinary and similar to readers and share both their personal lives and lifestyles with followers (Abidin Citation2015; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo Citation2021).

The success of an influencer is dependent on their reputation which is reliant on the trust endowed on them by their followers. In the trust relationship, followers value the influencer as an independent and third-party source who gives honest recommendations, only endorsing products they value (Lou Citation2022). In recognition of the value of promoting products, businesses frequently attempt to amplify the organic nature of blogging by engaging with them through gift giving and sponsorship (Ryu and Feick Citation2007). This leads to a dilemma as, Kretz and de Valck (Citation2010) and Lee and Youn (Citation2009) show that if the blogger is not seen as independent, the trustworthiness of the influencer can be damaged, and the influencer loses reputation and relevance. This danger is amplified by increasing distrust around traditional online communications by brands relating to recommendations and customer endorsements (Capozzi and Zipfel Citation2012).

Although there is a growing body of literature on influencer marketing, there are fewer studies focused on how bloggers/influencers can impact consumer behavior and intention to purchase (Abidin Citation2015; Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021; Lou Citation2022). Working with prominent opinion leaders on social media sites, such as bloggers, is projected to become common practice for marketers (Akman and Mishra Citation2017). Calls to research mothers’ involvement with social media, have highlighted a lack of research into how parents are influenced online and what is important to them in making decisions related to caring for their children (Doub, Small, and Birch Citation2016). This research explores the influence of parasocial relationships with bloggers and trust in bloggers on consumer intention to purchase.

This research investigates the purchase intention of consumers in Poland as it is impacted by the perceived trustworthiness/reputation and online influence of bloggers/influencers. We chose to examine the blogosphere of baby products in Poland as the E-commerce market for toys and baby products, which is an important contributor to the economy (Handlowe Citation2016). This contribution is projected to grow by almost 16% to a market volume of £588.40 by 2025 (Statista Citation2022). There is little published on E-commerce in Poland, despite being a popular activity with the first blog created in 1997 according to Karnkowski (Citation2012). The number of blogs in Poland is unknown, with no official data, however, Poland’s largest web portal and online news platform previously estimated that there were ∼2.8 million blogs written in the Polish language (Onet Citation2008). General internet use continues to rise in Poland, Mobirank (Citation2016) estimated 67% of the population were internet users as of 2016, with more recent figures putting internet use at 87% of the population (Sas Citation2021).

Since the geographic focus of research into influencers has been mainly developed in English speaking countries (Trammell et al. Citation2006; Vrontis et al. Citation2021), this research provides an important contribution to international understanding. We seek to investigate what products are purchased and the relative importance of trust and interaction with influences. To facilitate this, the rest of the article is structured by presenting a review of the pertinent literature and our conceptualization of the research followed by an outline of the methods employed, and the data collected. The results and analysis are given, coupled with a discussion of the meaning of these. A note on limitations and future research ends the article.

Literature review

As social commerce is projected to become mainstream for marketing, it is of increasing importance to understand consumers motivations, behaviors, and attitudes toward the commercialization of social media (Akman and Mishra Citation2017). This study explores trust/reputation and parasocial influence as key to the early stages of consumer decision-making which have an impact on purchase intention.

Trust and reputation

Trust and reputation are inter-linked concepts. Trust is defined as a willingness to have faith in another, it requires vulnerability, and consumers are increasingly willing to depend on influencers to guide their purchase intentions (Harrigan et al. Citation2021). Trust of social media influencers has been studied as it relates to users’ behavioral intention in the context of wider behavioral factors—such as enjoyment, social pressure, awareness, ethics and satisfaction (Akman and Mishra Citation2017). Trust has also been found to have a positive effect on the intention to engage in word of mouth (Dhun and Dangi Citation2023). This research is focused on how trust in influencer recommendations informs purchase intention. Trust has been identified in previous research as an important factor driving user purchase intention—both as an individual measure of feelings toward individual vendors, but also the trustworthiness of platforms or technology providers (Benson, Ezingeard, and Hand Citation2019; Harrigan et al. Citation2021). In comparison, reputation is considered a stable measure of trust for purchase decisions, because it represents perceptions over time (de Chernatony Citation1999). Reputation, as a construct that represents trust over time, has more typically been applied to brands in literature around social commerce rather than influencers or bloggers (Bacik et al. Citation2018; Hamouda Citation2018). This research includes reputation as linked to trust and asks consumers about the length of their engagement with influencers.

Trust has been studied in relation to influencers in specific contexts. Influencers have been found to help consumers build trust at all stages of decision making (desire, information search, evaluating alternatives, purchase decisions, satisfaction, and experience sharing) (Cooley and Parks-Yancy Citation2019) and this aids consumers when evaluating purchased experiences (Pop et al. Citation2022). When social media influencers are trusted they are followed more closely and exert more influence over their followers in the context of tourism purchases (Han et al. Citation2023). Trust in influencer endorsements has also been compared to trust in celebrity endorsements. Influencers are perceived to have less manipulative intent than other marketing messages, such as celebrity endorsements and advertisements (Gräve and Bartsch Citation2022). Influencers have thus been identified as highly trusted sources for particular categories, such as baby products, and in particular contexts, such as brand scandals (Abidin and Ots Citation2016). However, trust is not always achieved through consumers accessing influencers for information retrieval or entertainment (Lou and Yuan Citation2019). Influencers are also evaluated by the number of followers, but this is a more nuanced relationship. Whilst influencers with larger numbers of followers have greater perceived expertise and cultural capital, those with smaller audiences are perceived as more accessible and authentic (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). Much of the literature around influencers and trust relates to influencer impact on consumer brand trust (Lou and Yuan Citation2019; Nunes et al. Citation2018). This study is based on a category and not a particular brand, so brand trust is not considered.

The credibility of influencers has been offered as a more inclusive construct than trust, but trust and reputation were deemed more appropriate for this work. The credibility of influencers is tied to factors, such as their physical attractiveness, social attractiveness, trustworthiness, and perceived expertise (Bhattacharya Citation2023). These labels have emerged from source credibility subdimensions applied to influencers (Weismueller et al. Citation2020). Influencer credibility has been found to be highly relevant among particular populations, such as in the case of a German study of students who follow Instagram influencers whose attractiveness and popularity were found to positively impact consumer purchase intention (Weismueller et al. Citation2020). However, when it comes to our focus on parents, authors have pointed out that parents have socially layered concerns, such as what “being a good parent” relates to parenting style, and this leads to scrutiny when evaluating purchases that may be unique to parents (Oates, Watkins, and Thyne Citation2016). Because of this, source attractiveness and perceived expertise will not be considered in the research and the focus is on trust and parasocial as more relevant constructs.

Parasocial influence

Readers choose who they follow based on similar interests, such as parenting, and self-selectively enter into online communities (Tsimonis and Dimitriadis Citation2014) and this can develop a shared social identity (Närvänen, Kartastenpää, and Kuusela Citation2013). In communities where social belonging is key, the social value of consumption choices are important (Charry and Tessitore Citation2021). According to Euromonitor (Citation2021), consumers are increasingly values driven, with personal values being prominent in decision making. Perceived similarity to influencers based on outward similarities has been linked to increased purchase intention, but shared moral values do not necessarily encourage purchase intention (Shoenberger and Kim Citation2023) a relationship between consumer and influencer is required. These social bonds create parasocial influence which helps communicate shared values within the blogger community.

Parasocial interaction (PSI) is where consumers of media perceive a relationship with a media personality (Horton and Wohl Citation1956). Even when users do not interact directly with bloggers or participate in generating responses on blogs (comments or similar), they can still experience PSI and develop parasocial relationships. Leite and Baptista (Citation2022) differentiate between parasocial interactions (PSI) as a perception of reciprocal interaction and parasocial relationships (PSR) which requires involvement over time in the form of a social bond. PSI is where consumers of media perceive an experience or relationship with a media personality (Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen Citation2016). Despite perceived confusion over parasocial interaction and parasocial relationships, the original concept of PSR is characterized by an enduring one-sided intimacy over time which is based on repeat experiences or encounters (Horton and Wohl Citation1956). Influencers can foster the perception of relationship with their followers over time by responding quickly to followers, by personalizing thoughtful responses, and altering their content, which encourages feelings of intimacy or familiarity with followers (Abidin Citation2013).

Parasocial relationships with influencers can encourage consumption. Influencers are considered aspirational figures (Shan, Chen, and Lin Citation2020), but are perceived as ordinary and similar to readers (Abidin Citation2015; Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo Citation2021). As a result, psychological ownership, where a consumer feels as though something is “theirs” without actual possession or affiliation, is facilitated by influencers (Pick Citation2021). Social media are sites of conspicuous consumption, where individuals consume content related to actual consumables, and this virtual consumption perpetuates a desire to consume (Kozinets, Patterson, and Ashman Citation2017). When consumers feel they have a connection with the influencer, either through sharing similar characteristics, through parasocial interactions, or through actual relationships, they are more likely to experience psychological ownership which is linked positively to purchase intention (Pick Citation2021). So even in cases where parents are not looking for recommendations from influencers for purchases, following parent influencers with whom they identify, could create the desire for purchase. In this research, parasocial interactions and parasocial relationships are referred to under the umbrella term of parasocial influence.

Dynamic between parasocial influence and trust/reputation

There is an existing body of research that explores the dynamic between parasocial influence, trust, and purchase intention. For social media influencers, parasocial influence is more important than source trust because of the link between intimate self-disclosure, parasocial relationships, and brand trust (Leite and Baptista Citation2022). Intimate self-disclosure and parasocial relationships both foster a sense of immediacy and this is a predominant part of both constructs (Leite and Baptista Citation2022). Parasocial relationships have even been shown to reduce the evaluation of messages because the reputation of an influencer can transfer to trust in the products they endorse, putting parasocial relationships as an antecedent to trust (Breves et al. Citation2021). In the work of Breves et al. (Citation2021), it is important to note that the influencers in the study were endorsing low involvement brands. The authors noted that the mechanisms leading to influencer influence might vary for different product categories.

Several other studies have been published where results would indicate parasocial relationships are an antecedent, or more important, than trust. Reinikainen et al. (Citation2020) studied a vlogger’s (bloggers who produce video content) promotion of health services to a Finnish online community for young girls, looking specifically at the relationships between parasocial interactions, parasocial relationships, influencer credibility, brand trust, and purchase intention. This study found that a relationship with the influencer, even if parasocial, was critical to advancing the trust and reputation of the vlogger among the young respondents. Even though parasocial relationships have been shown to increase social closeness, other factors, such as perceived trustworthiness, can make influencer messages persuasive even for consumers who are distant (Kim and Kim Citation2022). This research determines whether parasocial influence or trust in a blogger/reputation of a blogger is more important in the category of baby products.

Research model and hypotheses

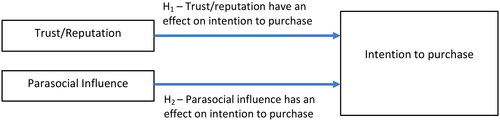

As this research explores the relationship between trust/reputation and parasocial influence on purchase intention among Polish parent blog readers, the following hypotheses and models have been developed.

The effects of trust/reputation on purchase intention

Consumers are increasingly relying on online reviews from other consumers for purchase decisions (Mukherjee and Jansen Citation2017). Furthermore, influencers, such as bloggers have been identified as highly influential in the literature because their intimate self-disclosure boosts their trustworthiness as a source (Leite and Baptista Citation2022). As bloggers are often non-expert sources, their reputation within their subject area is related to personal experience. Jøsang, Ismail, and Boyd (Citation2007) consider reputation as a social measure of trustworthiness within any given community as built up over time by inputs from others. Therefore, the perceived reputation of bloggers is most accurately evaluated by their audience.

Trust has long been established as a mediating factor that influences purchase intentions (Ambler Citation1997; Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Alemán Citation2005; Manzoor et al. Citation2020). Brand trust and perceived usefulness of a brand’s social media channels are positively linked to purchase intention (Harrigan et al. Citation2021). Trust and trustworthiness have been well-researched as influencer traits, but have less frequently been linked to influencer recommendations, product perceptions, and purchase intention (Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020). Multiple authors have specifically linked reader trust of bloggers/influencers to influence over reader’s engagement and ability to follow recommendations (Fakhreddin and Foroudi Citation2022; Pop et al. Citation2022; Doyle et al. Citation2012). Blogger trustworthiness evolves over time as readers come to evaluate blogger recommendations based on experience and know what kind of recommendations might be expected from the blog (Gefen, Karahanna, and Straub Citation2003; Hsu, Chuan‐Chuan Lin, and Chiang Citation2013). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Trust in bloggers and reputation of bloggers is positively associated with consumer intention to purchase based on blogger recommendation.

The effect of parasocial influence on purchase intention

Bloggers provide personal information, not necessarily related to the recommended products, and this enhances their influence on the reader, as the blogger is positioning their self as more believable, authentic, and approachable (Leite and Baptista Citation2022). This perception of knowing a blogger/influencer is viewed as a parasocial relationship (PSR) with its origin in parasocial interactions can lead to parasocial relationships developing over time resulting in the potential for parasocial influence. Reader’s perceived authenticity of influencers and perceived homophily with influencers has been linked to purchase intention among followers (Shoenberger and Kim Citation2023). Even when consumers feel a parasocial link to influencers, this must be combined with consumers being able to evaluate influencer promotions based on their own needs and experiences (Lou and Yuan Citation2019).

The parasocial influence of bloggers and influencers is such that they influence consumer decision-making through communicating the social value of purchases (Charry and Tessitore Citation2021). Parasocial relationships are reported as the primary factor influencing purchase intention with more influence than trust (Breves et al. Citation2021; Leite and Baptista Citation2022). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. Parasocial influence of bloggers is positively associated with consumer intention to purchase based on blogger recommendation.

Conceptual model of intention to purchase

To investigate and test the hypothesis, the conceptual model is formulated and presented in . This model will be used to structure the investigation. Purchase intention is defined as an individual’s conscious plan to purchase a good or service (Spears and Singh Citation2004). In this model, it is hypothesized that the consumer’s intention to purchase is influenced by the trust that the reader places in the blogger and the blogger’s reputation and in their parasocial interactions and relationship with them.

We consider that the relationships in might be moderated by socioeconomic variables notably age and education and experience in using blogging sites. Research by Zhang (Citation2009) shows that younger people are more likely to engage in E-commerce than older people and higher levels of education have been associated with higher levels of E-commerce engagement by for example Burke (Citation2002). As a person’s experience of E-commerce accumulates the tendency is that they will engage more in E-commerce (Shim et al. Citation2001). However, others, such as Al-Somali, Gholami, and Clegg (Citation2009), McCloskey (Citation2006), and Hernandez, Jimenez, and Martin (Citation2011) suggest that once someone engages in E-commerce socioeconomic factors cease to be of importance.

Methodology

Data was gathered with the use of an online questionnaire to obtain views on the two dimensions namely, Trust/Reputation and Parasocial Influence. The front end of the questionnaire introduced the research and covered demographic information as well as some basic measures, such as how long respondents have been reading blogs, how much time they spend reading them per week and what kind of products are they interested in. The second part of the questionnaires used 5-point Likert items. One question examined the degree to which their purchase intention was influenced by reading blogs. The end of the questionnaire contained questions related to Trust/reputation and Parasocial Influence. Four questions were designed to cover Trust/Reputation and four questions were used to investigate Parasocial Influence.

The questionnaire informed participants of the research objectives and how their data would be kept. The survey was gathered anonymously and adhered to the ethical guidelines of Edinburgh Napier University. Furthermore, the research secured ethical approval through the University ethics committee.

As the target population was Polish speaking, the questionnaire was translated into Polish and then back translated to English to assure the validity and reliability of the tool. The questionnaire was piloted by five Polish speaking blog readers with no major issues identified. The only modification made was to comments received concerning the use of Polish characters, so the questionnaire was revised to assure compliance with the Polish alphabet.

Due to the difficulty of identifying and accessing blog readers, randomization was not feasible and therefore the sampling strategy for this study was non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Although the generalization power of non-probability sampling is limited with increased sample sizes, the statistical power of the convenience sample also increases (Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim Citation2016). In the case of this study, the support of eleven different bloggers and a relatively large sample size increased the generalizability of the results.

The questionnaire was distributed with the help of eleven bloggers who had previously agreed to help with the research. These bloggers were asked to post the survey link within their blogs (on social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram) and endorse the research project. This they all did. The data gathering exercise took place during a 2-week period in March 2017 and resulted in the completion of 1050 questionnaires. We realize that this sampling runs the risk of selectivity in the choice of bloggers and hence bias. This was somewhat mitigated as we sent the posting request to all bloggers that we could identify, and the bloggers were not known to us. We accepted all who agreed to post.

Descriptive statistics were used in the first instance to investigate the data and inform the modeling process. Exploratory Factor Analysis was then used as a data reduction tool to avoid multicollinearity between the variables measuring Trust/Reputation and Parasocial Influence, it was also used to identify the latent variables which represent these constructs. Assessment of the significance of the factors on intention to purchase was evaluated using a multivariate binary logistic regression model using variables reflecting if respondents were influenced by blogs on their purchasing intention or not.

Results

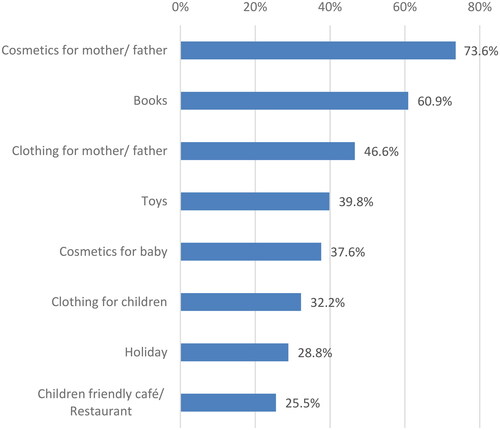

Due to the theme of the blogs being parental information, most of the respondents were women (97%), and therefore it was decided to exclude men from the analysis. A total of 1015 women competed the survey, 13.3% of these were young, under the age of 23 years. In terms of qualifications, 28.7% had education qualifications lower than a bachelor’s degree and 48.1% had a masters’ degree, which in Poland tends to be an extension of a bachelor’s degree. Only 1.2% had a doctorate. Most of the sample (87.4%) stated that they usually were online <6 h per week. Only 5.1% of the women were bloggers and 68.1% had been reading blogs for more than 2 years. A summary of the respondents’ product interest in blogs is presented in .

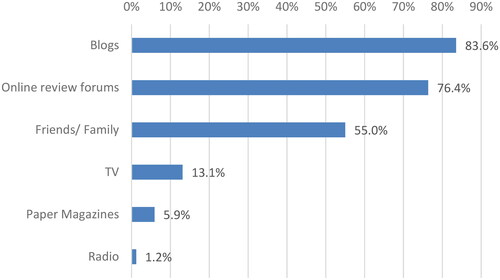

From , it is observed that most respondents (73.6%) look for cosmetics recommendations within blogs, followed by books (60.9%) and clothes (46.6%). Consumables appear to be the main products where respondents went to blogs for recommendations while holidays and children-friendly café/restaurant were only considered by a quarter of the sample. The sources where respondents report seeking recommendation are displayed in .

From it is apparent that many respondents (83.6%) used blogs as a source of recommendations followed by forums (76.4%) and family and friends (55%). This validates the research focus. It also contradicts previous assertions that friends and family are more trusted sources than blogs for recommendations (Cooley and Parks-Yancy Citation2019), though, in the case of parenting, online blogs might be an easier way to find others with children of similar ages.

Trust/reputation and parasocial influence

Questions on Trust/Reputation and Parasocial Influence were combined using factor analysis with varimax rotation—this was successful—resolving the eight questions into two components labeled “Parasocial Influence” and “Trust/Reputation.” These accounted for 30.2% and 28.7% of the original variation, respectively (The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was 0.821 and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant, p < 0.001). The rotated components are displayed in .

Table 1. Rotated components matrix.

Shown in are the resulting rotated components; the first component represents Parasocial Influence with the second one covering Trust/Reputation.

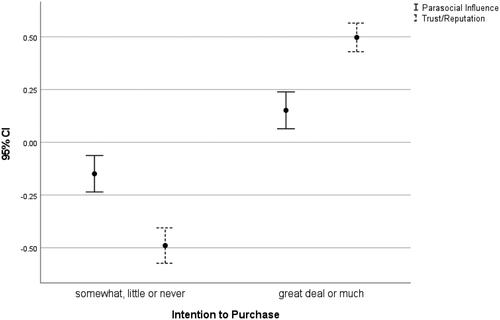

The dependent variable measuring the degree to which blogs influence purchase intention was measured using a 5-point Likert item. The distribution of this variable was skewed with the concentration of responses around two points and therefore it was decided to recode it into two categories, “somewhat, little or never” and “great or much,” accounting for 50.4% and 49.6% of the respondents, respectively. How the factors relate to the intention to purchase is displayed in . All the factors; Trust/Reputation and Parasocial Influence, appear associated with intention to purchase, with high values relating to great or much influence level on their intention to purchase. Trust/Reputation seems to have the greatest influence on the intention to purchase.

Modeling

The importance of these factors is now modeled, controlling for respondents’ education, age, if the respondent was a blogger, time spent online, and experience reading blogs using a binary logistic model. The dependent variable was the impact on purchasing. The model used is:

P: probability of purchase intention being affected a great deal or much, age,

education,

if they were blogger,

online hours,

how long have they been reading blogs,

Parasocial Influence,

Trust/Reputation.

The model fitted the data well, correctly predicting 74.3% of purchase intention outcomes compared with only 50.7% of the null model (72.7% of the somewhat, little, or never group and 76.0% of the great deal or much were correctly predicted). The coefficients, their significance, and odd ratio of the variables are presented in .

Table 2. Binary logistic model for the influence on purchasing behavior.

Older age is associated with being less influenced by blogs while those with a bachelor or postgraduate qualification were significantly more likely to be influenced compared to people with lesser qualifications. Being or not being a blogger was not significant, nor was time online. The more experience respondents have in reading blogs, results in the higher likelihood of intention to purchase. Next in terms of importance is Parasocial Influence with around 1.5 increased likelihood to have an intention to purchase with a one unit increase in their scale. Finally, trust seems to have a bigger impact over intention to purchase with a unit increase in its scale making it four times more likely to be influenced a great deal or much.

Factors and demographics

How the factors vary across the demographic control variables are exhibited in . Parasocial Influence and Trust/Reputation appears significantly higher amongst the younger group and Parasocial Influence was also significantly higher for those who read blogs for longer than two years, indicating the development of Parasocial Relationships. For education level, there was not a significant difference in Trust/Reputation scores for each level. Parasocial Influence scores decline significantly as education level increases. There were no significant differences in mean factor scores for various levels of time online or whether the respondent was a blogger.

Table 3. Mean level of factor scores and demographic control variables.

The significant differences in parasocial interaction with age, education, and length of time engaging with blogs and Trust/Reputation with age point to interaction effects with the mediating variables. These were investigated by adding interaction variables into the regression model, no significant effect was found.

Discussion

In assessing the impact of bloggers in influencing purchase intentions we add to social commerce literature in several ways through the context of the study and through the affirmation of the model. The decision-making support offered by social commerce is considered as the bloggers targeted were able to support data collection through their usage and interactions with their readers on social media sites, such as Facebook and Instagram. This response to earlier calls made for research into bloggers (Kulmala, Mesiranta, and Tuominen Citation2013; Vohra and Bhardwaj Citation2019). This study addresses an identified lack of research into influencer marketing from the consumer perspective (Abidin Citation2015; Lou Citation2022) and does so with a large sample size.

Results from testing our research hypotheses confirm that both parasocial influence and trust/reputation are important perceived blogger traits that have a direct influence on consumer purchase intention. Previous research found the importance of similarity as it relates to personality and product usage (O’Reilly et al. Citation2016), and the focus in this study on a particular blog category achieved this similarity of interest. Trust/reputation has been confirmed as an important factor for social endorsement (Manchanda, Arora, and Sethi Citation2022; Weismueller et al. Citation2020, Yin et al. Citation2018). Chen, Lin, and Shan (Citation2021) also found that the parasocial influence of influencers contributes to consumer trust in branded content, but trust/reputation was a primary indicator of purchase intention among our respondents. Trust/reputation was more important than parasocial influence among the respondents in this research. This may suggest a difference in priorities among parents as a consumer group as previous research identified parasocial influence as more influential on purchase intention (Breves et al. Citation2021; Leite and Baptista Citation2022). Thus, the research presented in this article, supports the views of Kretz and de Valck (Citation2010), Lee and Youn (Citation2009), and Carr and Hayes (Citation2014) in recognizing that concerns over blogger reputation and trust will apply to bloggers advising mothers in the baby product sector.

We find that time online, and whether or not a person was a blogger did not statistically significantly influence the likelihood to purchase. Three or more years’ experience of reading blogs was significantly associated with increased intention to purchase. This contradicts with McCloskey (Citation2006) and Al-Somali, Gholami, and Clegg (Citation2009) but does fit with Shim et al. (Citation2001). There are significant demographic differences in the likelihood of purchasing. Those who were younger and those with university level education were less likely to purchase. The lower levels of purchasing among less educated is perhaps explainable by lower income levels, but if this is so one would expect those 23 years old or more would have a higher likelihood to purchase than younger people, but this does not seem to be the case. Perhaps those over 23 years old have more experience or have a face-to-face network that includes parents who give direct recommendation.

From interactive effects between age, education, and experience appear as significant with the parasocial influence factor. Those 23 years old or more and those who have university level education report significantly lower levels of parasocial influence. This might be a confidence effect that comes with age and education. With more experience of reading blogs, there is significantly higher parasocial influence. Again, this could be a confidence effect as respondents have learned how to learn from and use the crowd and the influencer recommendations. It could also indicate that reputational trust rises over time as readers become more familiar with blogs as sources to aid in purchase decision making, which would support previous research, that following influencers more closely over time, leads to greater influence on purchases (Han et al. Citation2023). For the Trust/reputation factor, of the variables investigated only age had a significant association in that those 23 years old and over reported significantly lower levels in the trust/reputation factor.

An additional contribution of this research is the prominence of bloggers and influencers as trusted sources within the realm of social marketing. Recently authors have suggested users who like the sense of community that comes from engaging in online social spaces, may dislike shopping interferences in these social spaces (Wang, Huang, and Davison Citation2021). In contrast, our respondents identified blogs as more trusted sources for product recommendations than friends or family. This indicates that these individuals see reputable blogs whose communities they feel part of as acceptable sites to aid their consumer decision making. Additionally, the length of blog reading had an impact with more experienced blog readers reporting higher intention to purchase—and this supports our application of reputation to influencers as a form of trust that develops over time. Kim and Kim (Citation2023) found that homophily, social presence, and attractiveness create attachment which has a positive impact on source credibility while reducing resistance to advertising. This research confirmed that perceived attachment, explored through parasocial influence and blog reading over time, had an impact on purchase intention.

Implications for practice

As this research found a difference of opinions based on age, we suggest that generational differences may require different approaches for product recommendations. Older readers (23 years+) were slightly less likely to use blogs to inform purchase decisions than their younger counterparts. Blog readers 23 years of age and older were more likely to be influenced by with trust variables (such as trust in the blogger, reputation of the blogger, truthfulness of recommendations, and usefulness of recommendations) while younger readers (younger than 23) were more likely to be influenced to purchase intention by parasocial variables (such as feeling they would be friends with the blogger, perceived homophily with the blogger, parasocial relationship and social belonging). Though it should be noted that trust/reputation was still a significantly larger influence across all respondent groups. It is therefore recommended that bloggers who want to be more effective in their endorsements should consider the age of their target audience and tailor their content to draw on more parasocial elements to influence younger consumers. Examples of how this might be achieved in practice include intimate self-disclosure, engaging in emotional labor to maintain emotional bonds with readers, and adopting approachable identities with which consumers can identify (Scholz Citation2021; Tian Citation2013). As length of blog reading had a positive impact on purchase intention, bloggers should employ these tactics to foster long-term relationships and brands should seek partnerships with bloggers who engage in such activities. Despite the growth in blogging, this is a fragile environment for social commerce. Bloggers need to be perceived as trustworthy, reputable, and independent of companies trying to promote their goods.

Limitations and future research

We acknowledge that our data gathering can only give indicative insights, therefore a more probabilistic approach is required by accessing those using influencer pages and blogs directly, and not using an influencer as a gate keeper. However, this was beyond our resources. We also acknowledge there are several areas where more research is required. Our findings are limited to a focus on females who interact with bloggers through social media sites and this research reports on a single sector and country context (baby products in Poland). Nevertheless, the specificity of the sample composition and the context brings to light some useful insights into an example of a growth market—in this case, baby products—which offers opportunities for social commerce. There is also a potential for bias in our findings in how data was collected as it was exclusively collected via blogs which function as wider online communities. This makes generalization difficult, though there is a respectable sample size to underpin data analysis and statistical testing.

Furthermore, while the survey returned sufficient data, there is scope to add questions to allow other constructs to be investigated.

More research is needed to use longitudinal data to understand how parasocial relationships develop and evolve. The platforms through which users access influencer content could also be more fully explored to better understand how bloggers reach audiences over different platforms and if this has an impact on parasocial influence and trust/reputation.

Conclusions

This research investigated the influence of consumer trust in bloggers as reputable and reliable sources of product recommendation. This was assessed through the parasocial influence bloggers had on consumers as these two factors (trust/reputation and parasocial influence) influence consumer intention to purchase. This research confirmed that both factors were significantly correlated to intention to purchase, but that trust/reputation was more important to consumers than parasocial influence in the context of parent blogs. For parents online purchasing of baby products, we find that higher levels of education make purchasing more likely but being over 23 years of age means purchasing becomes less likely. This is unexplained and will be investigated in future research. This study contributes to a growing body of literature on social commerce in general and influencer marketing. The findings from this research can be usefully employed by bloggers and social media influencers to become more effective product endorsers by building trust and reputation over time. Marketers can also practically apply this research to better evaluate which influencer characteristics might suit different target audiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abidin, C. 2013. Cyber-BFFs: Assessing women’s ‘perceived interconnectedness’ in Singapore’s commercial lifestyle blog industry. Global Media Journal Australian Edition 7 (1):1–20.

- Abidin, C. 2015. Communicative intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media & Technology 8:1–16.

- Abidin, C., and M. Ots. 2016. Influencers tell all? Unravelling authenticity and credibility. In Blurring the lines: Market-driven and democracy-driven freedom of expression, ed. M. Edström, A. T. Kenyon, and E. M. Svensson, 153–61. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Akman, I., and A. Mishra. 2017. Factors influencing consumer intention in social commerce adoption. Information Technology & People 30 (2):356–70. doi: 10.1108/ITP-01-2016-0006.

- Al-Somali, S., R. Gholami, and B. Clegg. 2009. An investigation into the acceptance of online banking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation 29 (2):130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2008.07.004.

- Ambler, T. 1997. How much of brand equity is explained by trust? Management Decision 35 (4):283–92. doi: 10.1108/00251749710169666.

- Bacik, R., R. Fedorko, L. Nastisin, and B. Gavurova. 2018. Factors of communication mix on social media and their role in forming customer experience and brand image. Management & Marketing 13 (3):1108–18. doi: 10.2478/mmcks-2018-0026.

- Bedford, E. 2021. Baby products market worldwide – Statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/7365/baby-products-market-worldwide/#dossierContents__outerWrapper (accessed October 3, 2020).

- Benson, V., J.-N. Ezingeard, and C. Hand. 2019. An empirical study of purchase behaviour on social platforms The role of risk, beliefs and characteristics. Information Technology & People 32 (4):876–96. doi: 10.1108/ITP-08-2017-0267.

- Bhattacharya, A. 2023. Parasocial interaction in social media influencer-based marketing: An SEM approach. Journal of Internet Commerce 22 (2):272–92. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2022.2049112.

- Booth, N., and J. A. Matic. 2011. Mapping and leveraging influencers in social media to shape corporate brand perceptions. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 16 (3):184–91. doi: 10.1108/13563281111156853.

- Breves, P., J. Amrehn, A. Heidenreich, N. Liebers, and H. Schramm. 2021. Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. International Journal of Advertising 40 (7):1209–29. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2021.1881237.

- Burke, R. R. 2002. Technology and the customer interface: What consumers want in the physical and virtual store. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30 (4):411–32. doi: 10.1177/009207002236914.

- Campbell, C., and J. R. Farrell. 2020. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons 63 (4):469–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003.

- Capozzi, L., and L. B. Zipfel. 2012. The conversation age: The opportunity for public relations. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 17 (3):336–49. doi: 10.1108/13563281211253566.

- Carr, C. T., and R. A. Hayes. 2014. The effect of disclosure of third-party influence on an opinion leader’s credibility and electronic word of mouth in two-step flow. Journal of Interactive Advertising 14 (1):38–50. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2014.909296.

- Charlesworth, A. 2015. An introduction to social media marketing. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Charry, K., and T. Tessitore. 2021. I tweet, they follow, you eat: Number of followers as nudge on social media to eat more healthily. Social Science & Medicine 269:113595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113595.

- Chen, K., J. Lin, and Y. Shan. 2021. Influencer marketing in China: The roles of parasocial identification, consumer engagement, and inferences of manipulative intent. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 20 (6):1436–48. doi: 10.1002/cb.1945.

- Childers, C., and B. Boatwright. 2021. Do digital natives recognize digital influence? Generational differences and understanding of social media influencers. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 42 (4):425–42. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2020.1830893.

- Chiu, H.-C., A. Pant, Y.-C. Hsieh, M. Lee, Y.-T. Hsioa, and J. Roan. 2014. Snowball to avalanche Understanding the different predictors of the intention to propagate online marketing messages. European Journal of Marketing 48 (7/8):1255–73. doi: 10.1108/EJM-05-2012-0329.

- Cooley, D., and R. Parks-Yancy. 2019. The effect of social media on perceived information credibility and decision making. Journal of Internet Commerce 18 (3):249–69. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2019.1595362.

- de Chernatony, L. 1999. Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management 15 (1–3):157–79. doi: 10.1362/026725799784870432.

- Delgado-Ballester, E., and J. L. Munuera-Alemán. 2005. Does brand trust matter to brand equity? Journal of Product & Brand Management 14 (3):187–96. doi: 10.1108/10610420510601058.

- Dhanesh, G. S., and G. Duthler. 2019. Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness on paid endorsement. Public Relations Review 45 (3):101765. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.03.002.

- Dhun, and H. K. Dangi. 2023. Influencer marketing: Role of influencer credibility and congruence on brand attitude and eWOM. Journal of Internet Commerce, 22 (sup1):S28–S72. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2022.2125220.

- Dibble, J. L., T. Hartmann, and S. F. Rosaen. 2016. Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: Conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Human Communication Research 42 (1):21–44. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12063.

- Doub, A. E., M. Small, and L. L. Birch. 2016. A call for research exploring social media influences on mothers’ child feeding practices and childhood obesity risk. Appetite 99:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.003.

- Doyle, J. D., L. A. Heslop, A. Ramirez, and D. Cray. 2012. Trust intentions in readers of blogs. Management Research Review 35 (9):837–56. doi: 10.1108/01409171211256226.

- Enke, N., and N. S. Borchers. 2019. Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13 (4):261–77. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2019.1620234.

- Etikan, I., S. A. Musa, and R. S. Alkassim. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5 (1):1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.

- Euromonitor. 2021. Voice of the consumer: Lifestyles survey 2021: Key insights. https://www.portal.euromonitor.com/portal/?o%2BDb0GSz2hOL/rChLfZO6A%3D%3D (accessed January 20, 2022).

- Fakhreddin, F., and P. Foroudi. 2022. Instagram influencers: The role of opinion leadership in consumers’ purchase behavior. Journal of Promotion Management 28 (6):795–825. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2021.2015515.

- Gräve, J., and F. Bartsch. 2022. # Instafame: Exploring the endorsement effectiveness of influencers compared to celebrities. International Journal of Advertising 41 (4):591–622. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2021.1987041.

- Gefen, D., E. Karahanna and D. W. Straub. 2003. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly 27 (1):51–90. doi: 10.2307/30036519.

- Hamouda, M. 2018. Understanding social media advertising effect on consumers’ responses: An empirical investigation of tourism advertising on Facebook. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 31 (3):426–45. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-07-2017-0101.

- Han, M. C., and Y. Kim. 2017. Social media commerce: Town square to market square. Pan-Pacific Journal of Business Research 8 (1):29–46.

- Han, W., W. Liu, J. Xie, and S. Zhang. 2023. Social support to mitigate perceived risk: Moderating effect of trust. Current Issues in Tourism 26 (11):1797–812. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2022.2070457.

- Handlowe, W. 2016. Polski rynek produktów dla dzieci zyska dzięki 500+. https://www.wiadomoscihandlowe.pl/artykuly/polski-rynek-produktow-dla-dzieci-zyska-dzieki-500,8567 (accessed February 14, 2019).

- Harrigan, M., K. Feddema, S. Wang, P. Harrigan, and E. Diot. 2021. How trust leads to online purchase intention founded in perceived usefulness and peer communication. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 20 (5):1297–312. doi: 10.1002/cb.1936.

- He, C., H. Li, X. Fei, A. Yang, Y. Tang, and J. Zhu. 2017. A topic community-based method for friend recommendation in large-scale online social networks. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 29 (6):e3924. doi: 10.1002/cpe.

- Hendry, N., C. Hartung, and R. Welch. 2022. Health education, social media, and tensions of authenticity in the ‘influencer pedagogy’ of health influencer Ashy Bines. Learning, Media and Technology 47 (4):427–39. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2021.2006691.

- Hernandez, B., J. Jimenez, and M. J. Martin. 2011. Age, gender and income: Do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Information Review 35 (1):113–33. doi: 10.1108/14684521111113614.

- Holiday, S., R. L. Densley, and M. S. Norman. 2021. Influencer marketing between mothers: The impact of disclosure and visual brand promotion. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 42 (3):236–57. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2020.1782790.

- Horton, D., and R. R. Wohl. 1956. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 19 (3):215–29. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049.

- Hsu, C., J. Chuan‐Chuan Lin, and H. Chiang. 2013. The effects of blogger recommendations on customers’ online shopping intentions. Internet Research 23 (1):69–88. doi: 10.1108/10662241311295782.

- Hsu, C. P., H.-C. Huan, C.-H. Ko, and S.-J. Wang. 2013. Basing bloggers’ power on readers’ satisfaction and loyalty. Online Information Review 38 (1):78–94. doi: 10.1108/OIR-10-2012-0184.

- Hudders, L., S. De Jans, and M. De Veirman. 2021. The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising 40 (3):327–75. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925.

- Jøsang, A., R. Ismail, and C. Boyd. 2007. A survey of trust and reputation systems for online service provision. Decision Support Systems 43 (2):618–44. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.019.

- Karnkowski, K. 2012. Blogosfera polityczna w Polsce. http://depotuw.ceon.pl/handle/item/242 (accessed February 14, 2019).

- Kay, S., R. Mulcahy, and J. Parkinson. 2020. When less is more: The impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management 36 (3–4):248–78. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1718740.

- Kerr, G., K. Mortimer, S. Dickinson, and D. S. Waller. 2012. Buy, boycott or blog: Exploring the online consumer power to share, discuss and distribute controversial advertising messages. European Journal of Marketing 46 (3/4):387–405. doi: 10.1108/03090561211202521.

- Kim, D. Y., and H. Kim. 2023. Social media influencers as human brands: An interactive marketing perspective. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17 (1):94–109. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-08-2021-0200.

- Kim, D. Y., M. Park, and H. Y. Kim. 2022. An influencer like me: Examining the impact of the social status of Influencers. Journal of Marketing Communications :1–22. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2022.2066153.

- Kim, E., and Y. Kim. 2022. Factors affecting the attitudes and behavioral intentions of followers toward advertising content embedded within YouTube influencers’ videos. Journal of Promotion Management 28 (8):1235–56. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2022.2060414.

- Kozinets, R. V., A. Patterson, and R. Ashman. 2017. Networks of desire: How technology increases our passion to consume. Journal of Consumer Research 43 (5):659–82. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucw061.

- Kretz, G., and K. de Valck. 2010. ‘Pixelizeme!’: Digital storytelling and the creation of archetypal myths through explicit and implicit self-brand association in fashion and luxury blogs. In Research in consumer behavior, ed. R. W. Belk, 313–29. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.

- Kulmala, M., N. Mesiranta, and P. Tuominen. 2013. Organic and amplified eWOM in consumer fashion blogs. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 17 (1):20–37. doi: 10.1108/13612021311305119.

- Lee, H. S., and H. J. Lee. 2014. Factors influencing online trust. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 18 (1):41–51.

- Lee, J. A., and M. S. Eastin. 2021. Perceived authenticity of social media influencers: Scale development and validation. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 15 (4):822–41. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-12-2020-0253.

- Lee, M., and S. Youn. 2009. Electronic word of mouth (eWOM). International Journal of Advertising 28 (3):473–99. doi: 10.2501/S0265048709200709.

- Leite, F. P., and P. D. P. Baptista. 2022. The effects of social media influencers’ self-disclosure on behavioral intentions: The role of source credibility, parasocial relationships and brand trust. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 30 (3):295–311. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2021.1935275.

- Li, F., and T. Du. 2011. Who is talking? An ontology-based opinion leader identification framework for word-of-mouth marketing in online social blogs. Decision Support Systems 51 (1):190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2010.12.007.

- Lou, C. 2022. Social media influencers and followers: Theorization of a trans-parasocial relation and explication of its implications for influencer advertising. Journal of Advertising 51 (1):4–21. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2021.1880345.

- Lou, C., and S. Yuan. 2019. Influencer marketing how message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising 19 (1):58–73. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501.

- Manchanda, P., N. Arora, and V. Sethi. 2022. Impact of beauty vlogger’s credibility and popularity on eWOM sharing intention: The mediating role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Promotion Management 28 (3):379–412. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2021.1989542.

- Manzoor, U., S. A. Baig, M. Hashim, and A. Sami. 2020. Impact of social media marketing on consumer’s purchase intentions: The mediating role of customer trust. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Research 3 (2):41–8.

- McCloskey, D. 2006. The importance of ease of use, usefulness, and trust to online consumers: An examination of the technology acceptance model with older consumers. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing 18 (3):47–65. doi: 10.4018/joeuc.2006070103.

- Mintel. 2022. Babies’ and children’s personal care, nappies and wipes – UK – 2022. https://store.mintel.com/report/uk-babies-and-childrens-personal-care-nappies-and-wipes-market-report (accessed October 3, 2022).

- Mobirank. 2016. Mobile i digital w Polsce i na świecie w 2016 r. https://mobirank.pl/2016/01/27/mobile-digital-w-polsce-na-swiecie-2016/ (accessed February 14, 2019).

- Mukherjee, P., and B. J. Jansen. 2017. Conversing and searching: The causal relationship between social media and web search. Internet Research 27 (5):1209–26. doi: 10.1108/IntR-07-2016-0228.

- Närvänen, E., E. Kartastenpää, and H. Kuusela. 2013. Online lifestyle consumption community dynamics: A practice-based analysis. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 12:358–69. doi: 10.1002/cb.1433.

- Nunes, R. H., J. B. Ferreira, A. S. de Freita, and F. L. Ramos. 2018. The effects of social media opinion leaders’ recommendations on followers’ intention to buy. Review of Business Management 20 (1):57–73.

- O’Reilly, K., A. MacMillan, A. G. Mumuni, and K. M. Lancendorfer. 2016. Extending our understanding of eWOM impact: The role of source credibility and message relevance. Journal of Internet Commerce 15 (2):77–96. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2016.1143215.

- Oates, C., L. Watkins, and M. Thyne. 2016. Editorial: The impact of marketing on children’s well-being in a digital age. European Journal of Marketing 50 (11):1969–74. doi: 10.1108/EJM-10-2016-0543.

- Onet. 2008. Kto wymyślił blogi? http://wiadomosci.onet.pl/kto-wymyslil-blogi/yxwc5 (accessed February 14, 2019).

- Perez-Vega, R., K. Waite, and K. O'Gorman. 2016. Social impact theory: An examination of how immediacy operates as an influence upon social media interaction in Facebook fan pages. The Marketing Review 16 (3):299–321. doi: 10.1362/146934716X14636478977791.

- Pick, M. 2021. Psychological ownership in social media influencer marketing. European Business Review 33 (1):9–30. doi: 10.1108/EBR-08-2019-0165.

- Pop, R.-A., Z. Săplăcan, D. C. Dabija, and M. A. Alt. 2022. The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Current Issues in Tourism 25 (5):823–43. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729.

- Reinikainen, H., J. Munnukka, D. Maity, and V. Luoma-Aho. 2020. ‘You really are a great big sister’ – Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 36 (3–4):279–98. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2019.1708781.

- Ryu, G., and L. Feick. 2007. A penny for your thoughts: Referral reward programs and referral likelihood. Journal of Marketing 71 (1):84–94. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.71.1.084.

- Sánchez-Fernández, R., and D. Jiménez-Castillo. 2021. How social media influencers affect behavioural intentions towards recommended brands: The role of emotional attachment and information value. Journal of Marketing Management 37 (11–12):1123–47. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1866648.

- Sas, A. 2021. Internet usage in Poland – Statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/5573/internet-usage-in-poland/#topicHeader__wrapper (accessed October 3, 2022).

- Scholz, J. 2021. How consumers consume social media influence. Journal of Advertising 50 (5):510–27. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2021.1980472.

- Shan, Y., K. Chen, and J. E. Lin. 2020. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. International Journal of Advertising 39 (5):590–610. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2019.1678322.

- Shim, S., M. A. Eastlick, S. I. Lotz, and P. Warrington. 2001. An online prepurchase intentions model: The role of intention to search. Journal of Retailing 77 (3):397–416. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00051-3.

- Shoenberger, H., and E. A. Kim. 2023. Explaining purchase intent via expressed reasons to follow an influencer, perceived homophily, and perceived authenticity. International Journal of Advertising 42 (2):368–83. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2022.2075636.

- Spears, N., and S. N. Singh. 2004. Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26 (2):53–66. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164.

- Statista. 2022. Toys & baby – Poland. https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/ecommerce/toys-hobby-diy/toys-baby/poland (accessed October 3, 2022).

- Szolnoki, G., R. Dolan, S. Forbes, L. Thach, and S. Goodman. 2018. Using social media for consumer interaction: An international comparison of winery adoption and activity. Wine Economics and Policy 7 (2):109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.wep.2018.07.001.

- Tian, Q. 2013. Social anxiety, motivation, self-disclosure, and computer-mediated friendship: A path analysis of the social interaction in the blogosphere. Communication Research 40 (2):237–60. doi: 10.1177/0093650211420137.

- Trammell, K. D., A. Tarkowski, J. Hofmokl, and A. M. Sapp. 2006. Rzeczpospolita Blogów [Republic of Blog]: Examining Polish bloggers through content analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11 (3):702–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00032.x.

- Tsimonis, G., and S. Dimitriadis. 2014. Brand strategies in social media. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 32 (3):328–44. doi: 10.1108/MIP-04-2013-0056.

- Vanninen, H., J. Mero, and E. Kantamaa. 2023. Social media influencers as mediators of commercial messages. Journal of Internet Commerce 22 (sup1):S4–S27. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2022.2096399.

- Vohra, A., and N. Bhardwaj. 2019. From active participation to engagement in online communities: Analysing the mediating role of trust and commitment. Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (1):89–114. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2017.1393768.

- Vrontis, D., A. Makrides, M. Christofi, and A. Thrassou. 2021. Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (4):617–44. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12647.

- Wang, P., Q. Huang, and R. M. Davison. 2021. How do digital influencers affect social commerce intention? The roles of social power and satisfaction. Information Technology & People 34 (3):1065–86. doi: 10.1108/ITP-09-2019-0490.

- Weismueller, J., P. Harrigan, S. Wang, and G. N. Soutar. 2020. Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australasian Marketing Journal 28 (4):160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.03.002.

- Wiley, D. 2018. How mom bloggers helped create influencer marketing. AdWeek. https://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/how-mom-bloggers-helped-create-influencer-marketing/ (accessed October 3, 2022).

- Yin, C., Y. Sun, Y. Fang, and K. Lim. 2018. Exploring the dual-role of cognitive heuristics and the moderating effect of gender in microblog information credibility evaluation. Information Technology & People 31 (3):741–69. doi: 10.1108/ITP-12-2016-0300.

- Zhang, J. 2009. Exploring drivers in the adoption of mobile commerce in China. The Journal of the American Academy of Business 15 (1):64–9.