ABSTRACT

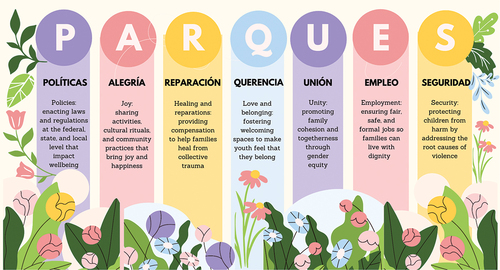

A growing body of evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States by increasing the prevalence and incidence of mental health problems. While it is important to document the repercussions of the pandemic, it is also necessary to articulate what a future of wellbeing and positive mental health will look like for Latinx children, youth, and families. To address this need, we propose PARQUES, a framework to dream about the future of Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. We imagine PARQUES as communal spaces for connection, joy, play, rest, and healing that result from activism and collective action. We use the Spanish word for parks as an acronym “PARQUES,” which stands for políticas (policies), alegría (joy), reparación (healing and reparations), querencia (love and belonging), unión (unity), empleo (employment), and seguridad (safety). These components work together to create an ecosystem to foster the physical and mental wellness and wholeness of Latinx children, youth, and families.

RESUMEN

Un número creciente de estudios sugieren que la pandemia de COVID-19 ha afectado desproporcionadamente a niñes, jóvenes, y familias Latines en los Estados Unidos al incrementar la prevalencia e incidencia de problemas de salud mental. Aunque es importante documentar el impacto de la pandemia, también es necesario articular cómo sería un futuro de bienestar y salud mental para niñes, jóvenes, y familias Latines. Para atender esta necesidad, proponemos PARQUES, un modelo para soñar el futuro de niñes, jóvenes, y familias Latines en los Estados Unidos. Imaginamos PARQUES como espacios comunes para la conexión, el goce, el juego, el descanso, y la sanación que promueve el bienestar, desarrollo integral, y la salud mental de les niñes, jóvenes, y familias Latines, y es el resultado de nuestro activismo y acción colectiva. Usamos la palabra PARQUES como un acrónimo que está compuesto de políticas, alegría, reparación, querencia, unión, empleo, y seguridad. Estos componentes trabajan juntos para crear un ecosistema que promueve el bienestar integral y la salud física y mental de les niñes, jóvenes, y familias Latines.

En la comunidad nosotros luchamos mucho por este parque, diez años de lucha … Y el valor más importante es la unión. Se llama Mariposa Park, que representa a los inmigrantes como yo y muchas de mis compañeras que están aquí.

In the community, we fought a lot for this park, ten years of fighting … And the most important value is unity. Its name is Mariposa [Butterfly] Park, representing immigrants like myself and many of my [female] peers here. (Bermudez et al., Citation2023, p. 211)

When the outbreak of COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in 2020, few of us imagined it would have such a negative and enduring impact on our mental health. Since then, a growing body of evidence has documented that the pandemic contributed to increased levels of parental stress, feelings of hopelessness, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, trauma, and suicidal ideation, among Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States (Penner et al., Citation2021; Polo et al., Citation2024; Salgado de Snyder et al., Citation2021). The pandemic did not operate in a vacuum, but it amplified ongoing social inequalities driven by racism, xenophobia, and capitalism to increase the risk of psychopathology (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Sanchez et al., Citation2022). This special issue examines these dynamics in more depth and documents the unique experiences, processes, and outcomes affecting the mental health of Latinx children, youth, and families following the pandemic (Causadias & Neblett, Citation2024).

The articles in this special issue discuss the mental health needs of undocumented and mixed status Latinx families during the pandemic (Garcini et al., Citation2024) and the perspectives of clinical providers working with asylum-seeking unaccompanied immigrant children from Central America who are separated from their families (Venta et al., Citation2024). The articles shed light on the experience of Mexican American parents as essential workers and the mental health of their children during the pandemic (Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2024) and how food insecurity and family stress impacted the wellbeing of Puerto Rican adolescents (Capielo Rosario et al., Citation2024). The collection of articles in this special issue provides evidence of a higher risk of internalizing problems during the pandemic among Latinx adolescents in Chicago public schools (Polo et al., Citation2024). The articles show important gaps in clinical research for Latinx youth who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people (Abreu et al., Citation2024) and/or AfroLatinx, Black, Biracial, and of other races during the pandemic (Sanchez et al., Citation2024).

The collection of articles in this special issue improves our understanding of the complex ways the pandemic has affected the mental health of Latinx children, youth, and families (Causadias & Neblett, Citation2024). For instance, there were some silver linings form the pandemic, as one study found that Latinx youth living in North Carolina fared better across the pandemic when they used problem-focused coping (Stein et al., Citation2024). Yet, reading some of these findings can make us feel disheartened by the harmful conditions that Latinx children, youth, and families experienced (and continue to experience) before, during, and after the pandemic, and by how these conditions increase the risk of developing psychopathology. The enduring problems Latinx children, youth, and families deal with and the new challenges they face can make us feel hopeless and restrict our ability to visualize a positive environment for the development of their mental health. As scientists, we often conclude that “more research is needed on X and Y” but fall short of extending beyond such refrains to take critical and important next steps. While it is true that more and better research is necessary, we also need to articulate and envision what a future of wellbeing and positive mental health will look like for Latinx children, youth, and families.

PARQUES: Dreaming the Future of Our Latinx Children, Youth, and Families

To address this challenge, we propose PARQUES, a framework to dream about the future of Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. We imagine a bright future for Latinx children, youth, and families that includes us. PARQUES (parks in Spanish) are imagined as communal spaces for connection, joy, play, rest, and healing that promote our wellbeing and mental health. We draw inspiration and guidance from theory and research on culturally situated playful environments for Latinx communities (Bermudez et al., Citation2023), radical hope and healing from racial trauma (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019; French et al., Citation2020), lessons from liberation psychology (Comas-Díaz & Torres Rivera, Citation2020), a rich tradition of freedom dreaming rooted in Black liberation theology (Hersey, Citation2022), and developmental science centering Black youth (Leath et al., Citation2023). We were also inspired by S.I.G.E.!, a model to guide the future of Filipina/x/o American psychology (David et al., Citation2022).

Following the structural-intersectional approach outlined in the introduction to this special issue, PARQUES engages the individual and collective dynamics that lead to the emergence of psychopathology (Causadias & Neblett, Citation2024). We imagine new spaces that embody the cultural and material conditions shaped by experiences of oppression and created by a commitment to resist injustice (Dantzler & Peron, Citation2023). We imagine PARQUES as places for recreation and family wellness, as public spaces for joy that are created by communities and serve to keep communities together. Similar to parks in the United States that exist because of Latinx community activism (Bermudez et al., Citation2023), these imagined spaces of future wellbeing will only be realized through our activism and collective action (Martínez, Citation2014; Neville & Cokley, Citation2022). We use the Spanish word for parks as an acronym “PARQUES,” that stands for políticas (policies), alegría (joy), reparación (healing and reparations), querencia (love and belonging), unión (unity), empleo (employment), and seguridad (safety). These components are not independent but work together to create an ecosystem to foster the physical and mental wellness and wholeness of Latinx children, youth, and families (see ).

Figure 1. Depiction of PARQUES.

In these PARQUES, Latinx families gather during the weekends and holidays to play fútbol and béisbol; listen to cumbia, corridos, salsa, and reggaetón; cook barbeque and share homemade food; tell stories in Spanglish or Indigenous languages; celebrate cumpleaños; and take Quinceañera and graduation photos. We believe PARQUES is innovative because most of the research in clinical child and adolescent psychology focuses on home and school environments for children and youth, and sometimes on work environments for parents and caregivers. Parks are a fourth space that is neither home nor school nor work, but an environment that creates and is created by communities, families, and youth. We imagine PARQUES as spaces for healing Latinx families through radical change in social policies that drive individual psychopathology and collective trauma (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019; French et al., Citation2020).

P – Políticas (Policies)

We dream about políticas. Policies are central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. The spaces we imagine, PARQUES, are embodied in cities, communities, and recreational parks that are free, open to everyone, welcoming, accessible, and often funded by taxpayers (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). Parks are public spaces by design, and many are the result of public policies (políticas públicas in Spanish) in response to community activism and collective action at the local level (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). Policies can have a positive effect in promoting developmental competencies, which are not limited to academic success but refer to wellbeing, including emotional physical, mental and financial health (Aceves et al., Citation2022), among Latinx children, youth and families.

Numerous laws, policies, and regulations enacted before and during the pandemic at the federal, state, and local level negatively impacted the development and wellbeing of Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States (Lopez, Citation2019; Rodriguez Vega, Citation2023; Rubio-Hernandez & Ayón, Citation2016; Valdez et al., Citation2022). Before the pandemic, state laws such as Arizona SB 1070 criminalized not carrying identification, encouraged racial profiling by law enforcement, and led to harassment and separation of Mexican-origin families in Arizona that traumatized their children (Rodriguez Vega, Citation2023; Rubio-Hernandez & Ayón, Citation2016). During the pandemic, public health policies that were necessary to stop the transmission of COVID-19, such as lockdowns, quarantines, and social distancing mandates, restricted children’s play and community interactions by limiting access to public spaces, including neighborhood playgrounds, gardens, and parks (Graber et al., Citation2021). Access to parks, in turn, predicted mental health among children and parents during the pandemic (Hazlehurst et al., Citation2022).

Against a longstanding backdrop of Anti-Latinx rhetoric and policy in the U.S (e.g., Zero Tolerance Policy and Migrant Protection Protocols; Rojas Perez et al., Citation2023), federal policies such as Title 42 restricted and deterred immigrants from Central America from requesting asylum and becoming refugees during the pandemic (Montoya-Galvez, Citation2023). These policies were not enacted because of public health concerns but because of xenophobia (Reznick, Citation2022). The intersection of immigration policies and the pandemic increased the risk of isolation, illness, parental job loss, and inability to access health care and federal benefits among immigrant Latinx families in Central Texas (Valdez et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, several laws harmed LGBTQ Latinx children, youth, and families (Abreu et al., Citation2024). As of 2023, there were 496 bills in state legislatures in the U.S. that undermined the rights of LGBTQ persons by limiting their ability to update gender information in their identifications and by sanctioning sexual and gender discrimination based on religion (ACLU, Citation2023).

In contrast to policies that adversely impact the mental health and wellbeing of Latinx children, youth and families, we need policy, research, and interventions that support undocumented and mixed-status Latinx families (Garcini et al., Citation2024), unaccompanied minors seeking asylum (Venta et al., Citation2024), and other marginalized Latinx and immigrant populations (Lebrón et al., Citation2023). A public health approach helps us dream about PARQUES, spaces in which robust public policies support immigrant, undocumented, and mixed-status Latinx families at the federal, state, and local levels (Young et al., Citation2023). We dream of PARQUES anchored by institutional commitment and action to promote antiracist care for unaccompanied immigrant children (Robles-Ramamurthy & Fortuna, Citation2023), as well as gender affirming care for transgender Latinx immigrants (Abreu et al., Citation2021).

We dream of PARQUES where policies such as the Every Student Success Act (ESSA) that promotes the success of Latinx students who are English language learners, their developmental competencies, and educational attainment (Aceves et al., Citation2022). We dream of PARQUES where policies extending Medicaid to undocumented young and pregnant people (State-Funded Health Coverage for Immigrants as of July Citation2023, Citation2023; Young Adult Expansion, Citation2022), can increase access to health coverage for and promote the health of undocumented immigrant families. We dream of PARQUES where Latinx youth with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status, who were brought to this country by their parents as children (Gonzales et al., Citation2020), can be happy and enjoy time with their families because the U.S. Congress passed comprehensive legislation that gave them a pathway to citizenship. Ultimately, these recreational spaces we imagine can integrate best practices for policies centered on Latinx children, youth, and families, including the need to address their diverse needs and focus on contexts that include and extend beyond education (Aceves et al., Citation2022).

A – Alegría (Joy)

We dream of alegría. Joy is central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. The spaces we imagine, PARQUES, are filled with Latinx families having fun and being happy. Latinx families find joy in spending time with each other and have cultural rituals and traditions that solidify these bonds, before and during the pandemic (Causadias et al., Citation2022). Some of these Latinx rituals that bring joy take place once in a lifetime, such as Quinceañeras. Others take place once a year, such as Día de los Muertos, while other rituals are celebrated weekly, such as family dinners (Causadias et al., Citation2022; González, Citation2019; Marchi, Citation2022). According to the U.S. Census, a higher proportion of Latinx parents had frequent dinners with their children than their non-Latinx parents every year from 2018 to 2021 (Mayol-Garcia, Citation2022). For Chicano families, family dinners create a space to bond, share experiences, and learn about their language and identities (Silva, Citation2020).

Latinx children, youth, and families find joy in these shared activities around food that go beyond spending time together and involve active engagement. These include having children help in making lists and going grocery shopping, counting items, measuring quantities, preparing ingredients, cooking and baking, and sharing meals (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). These activities are instrumental in helping parents but are also emotional in eliciting positive feelings and fostering strong family relationships. These shared activities illustrate the importance of promoting happiness, fun, play, and joy for healthy child development and for the development of strong family bonds (Ginsburg & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Citation2007). Joy is at the heart of what makes parks learning landscapes and environments that promote playful learning, intergenerational connections with the family, celebrations with the broader community (e.g., block parties), and physical activity to stay healthy (Bustamante et al., Citation2019).

The centrality of joy takes a new meaning following the pandemic because so many Latinx children are still dealing with its consequences, including orphanhood, physical illness, mental health problems, and economic adversity (Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2024; Hillis et al., Citation2021; Vargas & Sanchez, Citation2020). In this scenario, promoting joy is more than helping Latinx children feel good, but structuring recreational activities outside schools that can promote mental health, wellbeing, and facilitate learning and academic success (Bustamante et al., Citation2019). Examples include guided play and games in parks and playgrounds that are relational, actively engaging, meaningful, and joyful, and that promote the development of skills that help Latinx children thrive, such as collaboration, communication, critical thinking, imagination, and self-confidence (Bermudez et al., Citation2023).

A playful environment for family celebrations, shared activities, and guided play and games in parks helps us dream about PARQUES, spaces in which Latinx families are happy, joyful, and healthy. We dream of PARQUES where Latinx children, youth, and families who experienced trauma before, during, and after the pandemic can experience joy through access to basic social services they need, including mental health treatment to heal from harm.

R – Reparación (Healing and Reparations)

We dream of reparación. Healing and reparations are central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. The spaces we imagine, PARQUES, are enjoyed by Latinx families that are healing from trauma because they have received material and symbolic compensation, and access to culturally responsive mental health services (Meléndez Guevara et al., Citation2021). Parks themselves serve to repair urban and rural landscapes by reclaiming water, forests, and wildlife for rest and recreation. Parks often exist because of community activism (Bermudez et al., Citation2023), and environmental initiatives to heal cities and towns from historical harms, which are related to reparations (reparación in Spanish). Reparations are important to achieve national reconciliation, promote justice, restore dignity, and strengthen democracy (Martín-Baró, Citation1990).

Reparations are specific programs that recognize and heal the wounds of racial trauma and violence (Hannah-Jones, Citation2021). Reparations are not about vengeance (Martín-Baró, Citation1990) or about punishing specific groups, such as White people, nor are they intended to be financed by them (Hannah-Jones, Citation2021). Reparations are a historical obligation of the U.S. government to address the harm it caused, for instance, by sanctioning enslavement of Black people in the Constitution, sponsoring racial segregation, and by laws and policies designed almost exclusively for the benefit of White families and the detriment of Black families, such as the GI Bill (Hannah-Jones, Citation2021; Katznelson, Citation2005). Reparations include, but are not limited to, programs for financial compensation, social support, and truth and reconciliation (Hannah-Jones, Citation2021). Trauma before, during, and after the pandemic demonstrated the need of healing and reparations for Latinx children, youth, and families.

An enduring source of trauma that happened before, during, and after the pandemic was the family separation of unaccompanied immigrant children from Central America seeking asylum in the U.S (Venta et al., Citation2024). In 2021, roughly 2,217 children who came to the U.S. fleeing violence in Central America were still separated from their families (Saboroff, Citation2021). Although President Biden said separated migrant families deserved financial compensation, his Justice Department reversed course in court and said they were not entitled to it (Sacchetti & Sullivan, Citation2022). Families that suffered and are still experiencing harm over U.S. government family separation policies demand reparations to heal from these harms (Physicians for Human Rights, Citation2022). Reparations can make healing from trauma possible for these families. Healing goes beyond coping and symptom relief and means structural changes in policies, actions, and practices that allow these families to thrive, live out their full potential, and become whole again (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019; French et al., Citation2020; Neville, Citation2017).

Supporting healing and reparations can help us dream about PARQUES, spaces in which Latinx children, youth, and families can receive the mental health services that they need to heal from trauma (Garcini et al., Citation2024; Venta et al., Citation2024). We dream of PARQUES where Latinx children, youth and families go to repair damage from trauma sequelae and reclaim psychological balance, resilience, and fortitude (Walker, Citation2020). We dream of PARQUES where unaccompanied children from Central America can be reunited with their families, have access to quality health and education, financial compensation, and refugee status in the U.S., so they feel they belong, and they are welcomed.

Q – Querencia (Love and Belonging)

We dream of querencia. Love and belonging are central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. The spaces we imagine, PARQUES, are places of querencia, where our people feel strong attachment, love, sense of belonging, fond memories, and connection to the land. Querencia is a concept created by Indigenous Hispanos of the Northern Rio Grande Region of New Mexico that has been increasingly used in Chicano studies and related fields to describe how Latinx communities develop a deep connection to their homeland (Arellano, Citation1997; Gonzales, Citation2020). Querencia means love of place, love of home, connection and belonging rooted in a strong relationship with a specific homeland or patria chica (Anaya, Citation2020; Fonseca-Chavez et al., Citation2020). Parks are places of querencia, of love and belonging for Latinx children, youth, and families, of memories and lived community experiences of participation in fiestas, holidays, and celebrations (Gorman, Citation2020).

The pandemic demonstrated the importance of love and belonging to a specific place for the mental health and wellbeing of Latinx children, youth, and families. School closures, lockdowns, and quarantines kept many children out of school, inhibited peer interactions, and increased social isolation and internalizing symptoms among Latinx children and youth (Cortés-García et al., Citation2022; Polo et al., Citation2024). Latinx LGBTQ youth, in particular, have been impacted significantly by these pandemic restrictions, because many find among their LGBTQ peers the social support and affection their family denies them (Salerno et al., Citation2020). Supporting the spaces where Latinx LGBTQ youth feel love and belonging requires that we address cissexism, heterosexism, and rigid gender norms in our Latinx communities that are driven by machismo (Abreu et al., Citation2023) and marianismo (Carranza, Citation2018; Vega et al., Citation2023). Unfortunately, Latinx LGBTQ youth are not only harmed by hostility and violence within our communities, but by neglect among scientists. Most of the research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latinxs did not include Latinx LGBTQ youth in their samples, focusing almost exclusively on cisgender, gender binary, and heterosexual Latinx youth (Abreu et al., Citation2024).

Fostering places of love and belonging for Latinx LGBTQ youth can help us dream about PARQUES as safe spaces where queer Latinx children, youth, and families feel querencia, that they are loved and welcomed, and where transgender Latinx youth belong and can become attached rather than forced to migrate (Abreu et al., Citation2021). This imperative follows a pandemic that has emphasized and reminded us of the significance of community connection, support, and activism for Black transgender youth (Sostre et al., Citation2023). Cultivating querencia requires that we address the specific needs of accessibility and belonging, for not only Latinx LGBTQ youth but also diverse and intersectional groups among Latinx children, youth and families. For example, Latinx youth who are queer and with disabilities, could benefit from educational accommodations, mental health services in both English and Spanish, and recreational settings that are gender affirming (Suarez-Balcazar et al., Citation2022; Zongrone et al., Citation2020). We dream of PARQUES as sexual and gender inclusive places where Latinx LGBTQ and other marginalized youth and their families can share, but also have fun and connect with their peers in activities and celebrations, united with their chosen family.

U – Unión (Unity)

We dream of unión. Unity is central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. The spaces we imagine, PARQUES, are embodied in parks that make unity possible by providing amenities that bring together family and community members who live in different places and are separated by distance. Research shows the importance of parks as places for unity, as spaces for family reunions that bring Latinx immigrants together as they used to be in their countries of origin (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). As one research participant said in a study: “Es algo que uno añora porque en nuestros países íbamos al kiosco o a la plaza, porque son reuniones en familia. Es lo mismo cuando vamos a los parques. Es algo muy bonito, que tomen en cuenta los parques. Es la unión familiar que es un valor muy importante. [It is something that we yearn for because, in our countries, we would go to the kiosk or plaza because they are family gatherings. It’s the same thing when we go to the park. It’s beautiful that you consider parks. It is family unity, which is a very important value] (Bermudez et al., Citation2023, pp. 211–212).

Unity as family cohesion and togetherness is key for Latinx families and communities living in the diaspora, such as Puerto Rican families living in the U.S. mainland (Capielo Rosario et al., Citation2024) and adolescent boys who migrated to the U.S. to do farm work (Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2022). Unity is also critical for Central American families who have experienced separation when seeking asylum in the U.S. and want to be reunited (Venta et al., Citation2024), and for Mexican American families who saw a family member deported to Mexico (Rodriguez Vega, Citation2023). However, this emphasis on unity can obscure structural inequalities and power dynamics within Latinx families, in which values such as familism and marianismo are often used to force Latinas into gender conformity, obedience, and self-sacrifice (Cahill et al., Citation2021; Vega et al., Citation2023).

The pandemic showcased the importance of unity for Latinx children, youth, and families because it led to lockdowns, social distance measures, and quarantines that made it difficult for Latinx families to see each other, spend time together, and travel, while others living in multigenerational homes found it difficult to maintain social distance (Gonzalez et al., Citation2021). The pandemic also made some Latinx families spend more time together because school closures made children stay at home, which offered opportunities for family connection but also increased parental stress (Stein et al., Citation2024). The pandemic also invited us to reflect on how this quest for unity in Latinx families could become a burden for Latinas. For instance, Latina mothers struggled during the pandemic as many navigated gendered expectations and family obligations, as well as financial strain and the challenge of dealing with a pandemic as undocumented immigrants (Hibel et al., Citation2021; Ybarra & Lua, Citation2023).

Attention to unity can help us dream about PARQUES, spaces in which Latinx children, youth, and families can be reunited and spend time together. We dream of PARQUES that promote family wellbeing and mental health, not by fostering unity as conformity, but taking into account complexity and nuance as we challenge traditional gender roles and foster gender equitable arrangements of family roles and responsibilities. We dream of PARQUES where Latinos, Latinas, and nonbinary Latinxs work together to ensure family cohesion, and families have the resources and time to learn how to be more gender equitable.

E – Empleo (Employment)

We dream of empleo. Employment is central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. Fair, safe, and formal employment allows Latinx adults to cover and afford basic needs, thrive and provide for their children, pursue the “American Dream” of owning a house, support their extended family within and outside the United States, invest in their communities, and pay taxes that are reinvested in recreational public spaces, such as parks. Fair, safe, and formal employment allows Latinx families to make time to enjoy parks, while unfair, dangerous, and informal employment becomes a barrier for rest, recreation, and spending time together (Stodolska & Santos, Citation2006).

The pandemic exacerbated labor and mental health inequities among Latinx people, affecting family dynamics and compromising health among those who were most vulnerable (Olayo-Méndez et al., Citation2021; Villatoro et al., Citation2022), especially among farmworkers who were considered essential but treated as expendable (Handal et al., Citation2020). Unfair labor practices that take advantage of Latinx workers, as well as those who are immigrants, not fluent in English, and lacking college education, can limit the quantity and quality of time they can spend with their family (Olayo-Méndez et al., Citation2021). Exploitation of undocumented immigrant workers from Mexico and Central America in U.S. agriculture, aggravated by extreme heat, increases the risk of heat-related illness and death (Iglesias-Rios et al., Citation2023; Kuehn, Citation2021). A new wave of state legislation removing child protections against dangerous job conditions in the United States may increase the risk of death and injury for poor and immigrant Latinx youth (Sherer & Mast, Citation2023).

Several studies suggest that employment extends beyond safety, as it had detrimental effects on the mental health of Latinx children, youth, and families during the pandemic. Family financial stress and food insecurity during the pandemic had a significant impact on the mental health of Puerto Rican adolescents living in the U.S., especially among those who identified as racial minorities (Capielo Rosario et al., Citation2024). In one study, over half of the Latina mothers in low-income essential worker families were forced to make economic cutbacks, which were related to higher anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic (Hibel et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, caregivers’ essential worker status predicted Mexican American adolescents’ mental health outcomes during the pandemic, particularly for adolescent boys (Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2024).

Supporting fair, safe, and formal employment can help us dream about PARQUES, spaces in which Latinx children, youth, and families can have food security and financial stability that promote their wellbeing and mental health (Capielo Rosario, Citation2024; Salinas & Salinas, Citation2022). We dream of PARQUES where Latinx children and youth are protected against dangerous jobs, and Latinx immigrant farmworkers and others considered “essential” during the pandemic are treated as such, receiving a fair minimum wage and benefits that allow them to live with dignity and safety with their families (Bonilla-Silva, Citation2022).

S – Seguridad (Safety)

We dream of seguridad. Safety is central to dreaming a future of wellbeing for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States. Safety can be defined in the positive sense by experiences, environments, and services Latinx children, youth, and families need for healthy development, and in the negative sense by what they do not need and should be protected against. In the positive sense, safety is defined by nurturing attachment relationships with sensitive caregivers that foster the development of emotion regulation and shape adaptation (Sroufe et al., Citation2014), welcoming school settings that support bilingual development and embrace cultural diversity (Salas et al., Citation2013), and gender and sexual affirming environments for Latinx LGBTQ youth that embrace their needs (Abreu et al., Citation2024).

In the negative sense, safety is defined by protecting families against immigration and incarceration policies and legislation that employ family separation as a punishment (Venta et al., Citation2024), against maltreatment, abuse, and neglect at home (Rodriguez et al., Citation2021), and against gun violence, the leading cause of death for children and adolescents in the United States (Roberts et al., Citation2023). Promoting safety for Latinx children, youth, and families requires that we go to the root causes of the issues that threaten their lives and wellbeing. In the case of gun violence, evidence shows that the key variable is not the firearms, but the history of antiblackness in the United States (Anderson, Citation2021). According to historian Dr. Carol Anderson, antiblackness is the main reason behind the enactment of the Second Amendment, the expansion of gun rights, and inaction in the face of mass shootings because these laws and policies are motivated by fear and criminalization of Black people (Anderson, Citation2021). Antiblackness is hatred, fear, and complete dehumanization of Black people, denying their humanity and right to be treated with dignity (Anderson, Citation2021; Jung & Vargas, Citation2021).

The pandemic brought to light the need for safety and the danger of antiblackness because it coincided with the Black Lives Matter movement following the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many others (Neville & Cokley, Citation2022). The pandemic showed how antiblackness is a threat to safety because it revealed racial health inequities in access to healthcare, vaccination, protective equipment, and safe work environments (Churchwell et al., Citation2020; Neville & Cokley, Citation2022). The pandemic and the movement for Black Lives also brought a racial reckoning within Latinx communities by showing that antiblackness harms Black children, youth, and families, including those who are AfroLatinxs. Although many Latinxs claim they cannot be racist because they are minorities, antiblackness has a profound influence in Latinx communities (Fuentes et al., Citation2021; Hernández, Citation2022). Antiblackness explains why Latinx people mistreat their own family members who are dark skinned; discriminate against AfroLatinxs in school, housing, and work environments; and engage in White vigilantism and murder Black people (Hernández, Citation2022).

Supporting safety for the wellbeing of Latinx children, youth, and families can help us dream about PARQUES, spaces that are not only free of guns, but also the threat of antiblackness. We dream of PARQUES where Latinx children, youth, and families, especially those who are AfroLatinx, feel welcome, safe, and seen. We dream of PARQUES as safe spaces in which Latinx families tell stories, have honest conversations, and hold each other accountable over their own antiblackness. We imagine places that become safe because activists from Latinx and African American communities build coalitions to pursue programs that benefit both, as they have done in the past, including public safety campaigns, new day care programs, free school breakfast, gang reduction efforts, and vocational education (Hernández, Citation2022).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States, exacerbating parental stress, uncertainty, food insecurity, economic hardship, and increasing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and trauma (Capielo Rosario et al., Citation2024; Carlos Chavez et al., Citation2024; Polo et al., Citation2024). It has uniquely impacted some Latinx populations, including unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, undocumented immigrants, Latinx families with youth with disabilities, AfroLatinxs, and/or Latinx LGBTQ youth (Abreu et al., Citation2024; Garcini et al., Citation2024; Sanchez et al., Citation2024; Suarez-Balcazar et al., Citation2021; Venta et al., Citation2024), but it has also shown the strength, resilience, and resources of Latinx families (Stein et al., Citation2024). The negative impact of the pandemic on their mental health can make us feel hopeless and inhibit our ability to imagine a better future for Latinx children, youth, and families.

Hope is crucial to believe that our work is not in vain, to experience a sense of agency and the conviction that we can completely change our negative social conditions, to avoid being paralyzed by fear, and to envision new possibilities (French et al., Citation2020). In this paper, we proposed PARQUES, a new model to dream about a future for Latinx children, youth, and families in the United States that is full of hope. We discussed the importance of public policies, joy, healing and reparations, love and belonging, unity, employment, and safety. This is not a laundry list of things that can independently have a positive effect. Instead, we believe these components work together to create an ecosystem to foster the physical and mental wellness and wholeness of Latinx children, youth, and families. The significance of public policies is exemplified in the need for reparations. Employment makes it possible for families to develop love and belonging to a homeland (querencia), rather than being forced to migrate to seek better jobs. Healing and reparations make it possible for families to be joyful, and safety creates the conditions for unity. Many in our communities yearn for unity and find joy when reunited, especially those living in the diaspora who have family members across borders.

We dream that these components of PARQUES can be enacted in physical spaces and through changes in material conditions, as well as in virtual and symbolic ways. Indeed, the pandemic saw a proliferation of remote and virtual ways of engaging children, youth, and families through online schooling, social media engagement, telehealth apps, and mental health services delivered through Zoom and other digital platforms (Wasil et al., Citation2021). These innovations are crucial to increase accessibility, improve access to educational and therapeutic services, and reduce racial inequities in mental health. At the same time, we believe we need to invest in structural change and physical recreational spaces to foster the joy and happiness of Latinx children, youth, and families (Bermudez et al., Citation2023). We invite clinical researchers, practitioners, students, and policymakers to work with our Latinx communities and families to transform our dream of PARQUES into real parks. Soñemos juntos y hagamos nuestros sueños realidad. Let’s dream together and make our dreams a reality.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the special issue “Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Latinx Children, Youth, and Families: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities”. We are grateful for the support and guidance we received from Dr. Andrés De Los Reyes. José acknowledges Dr. Rafael A. Martínez for teaching him about querencia and identifying key literature, and Dr. Edward D. Vargas for introducing him to parques where Latinx children, youth, and families come together. Enrique acknowledges Drs. Paul J. Fleming and William D. Lopez for their help and guidance in navigating the literature on policies. We received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors to complete this work. We declare no conflict of interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abreu, R. L., Barrita, A. M., Martin, J. A., Sostre, J., & Gonzalez, K. A. (2024). Latinx LGBTQ youth, COVID-19, and psychological well-being: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158839

- Abreu, R. L., Gonzalez, K. A., Capielo Rosario, C., Lockett, G. M., Lindley, L., & Lane, S. (2021). “We are our own community”: Immigrant Latinx transgender people community experiences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(4), 390–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000546

- Abreu, R. L., Hernandez, M., Ramos, I., Badio, K. S., & Gonzalez, K. A. (2023). Latinx bi+/plurisexual individuals’ disclosure of sexual orientation to family and the role of latinx cultural values, beliefs, and traditions. Journal of Bisexuality, 23(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2022.2116516

- Aceves, L., Crowley, D. M., Rincon, B., & Bravo, D. Y. (2022). Transforming policy standards to promote equity and developmental success among latinx children and youth. Social Policy Report, 35(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/sop2.18

- ACLU. (2023). Mapping attacks on LGBTQ rights in U.S. State legislatures. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights

- Anaya, R. (2020). Foreword. Querencia, Mi Patria Chica. In V. Fonseca-Chavez, L. Romero, & S. R. Herrera (Eds.), Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico homeland (pp. xiii–xxii). University of New Mexico Press.

- Anderson, C. (2021). The second: Race and guns in a fatally unequal America. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Arellano, J. E. (1997). La querencia: La raza bioregionalism. New Mexico Historical Review, 72(1), 31–37.

- Bermudez, V. N., Salazar, J., Garcia, L., Ochoa, K. D., Pesch, A., Roldan, W., et al. (2023). Designing culturally situated playful environments for early STEM learning with a Latine community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2023.06.003

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2022). Color-blind racism in pandemic times. Sociology of Race & Ethnicity, 8(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220941024

- Bustamante, A. S., Hassinger‐Das, B., Hirsh‐Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2019). Learning landscapes: Where the science of learning meets architectural design. Child Development Perspectives, 13(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12309

- Cahill, K. M., Updegraff, K. A., Causadias, J. M., & Korous, K. M. (2021). Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 947–985. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000336

- Capielo Rosario, C., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Sanchez, D., Torres, L., Mattwig, T., Pituch, K. (2024). Mental health among Puerto Rican adolescents living in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2024.2301775

- Carlos Chavez, F. L., Gonzales‐Backen, M. A., & Perez Rueda, A. M. (2022). International migration, work, and cultural values: A mixed‐method exploration among latino adolescents in US agriculture. Family Relations, 71(1), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12603

- Carlos Chavez, F. L., Sanchez, D., Capielo Rosario, C., Han, S., Cerezo, A., & Cadenas, G. A. (2024). COVID-19 economic and academic stress on Mexican American Adolescents’ psychological distress: Parents as essential workers. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2023.2191283

- Carranza, M. (2018). Marianismo. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology (pp. 1–2). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeos1243

- Causadias, J. M., Alcalá, L., Morris, K. S., Yaylaci, F. T., & Zhang, N. (2022). Future directions on BIPOC youth mental health: The importance of cultural rituals in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2084744

- Causadias, J. M., & Neblett, E. W. (2024). Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Latinx children, youth, and families: Clinical challenges and opportunities. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2024.2304143

- Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Adames, H. Y., Perez-Chavez, J. G., & Salas, S. P. (2019). Healing ethno-racial trauma in latinx immigrant communities: Cultivating hope, resistance, and action. American Psychologist, 74(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000289

- Churchwell, K., Elkind, M. S., Benjamin, R. M., Carson, A. P., Chang, E. K., Lawrence, W., & American Heart Association. (2020). Call to action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation, 142(24), e454–e468. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936

- Comas-Díaz, L., & Torres Rivera, E. (2020). Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000198-000

- Cortés-García, L., Hernandez Ortiz, J., Asim, N., Sales, M., Villareal, R., Penner, F., & Sharp, C. (2022). COVID-19 conversations: A qualitative study of majority Hispanic/Latinx youth experiences during early stages of the pandemic. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51(4), 769–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09653-x

- Dantzler, P. A., & Peron, M. A. (2023). Towards a praxis of manifesting spatial imaginaries. Dialogues in Urban Research, 1(3), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/27541258231195599

- David, E. J. R., Nadal, K. L., & Del Prado, A. (2022). S.I.G.E.!: Celebrating filipina/x/o American psychology and some guiding principles as we “go ahead”. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000277

- Fonseca-Chavez, V., Romero, L., & Herrera, S. R. (2020). Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico homeland. University of New Mexico Press.

- French, B. H., Lewis, J. A., Mosley, D. V., Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Chen, G. A., & Neville, H. A. (2020). Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 14–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019843506

- Fuentes, M. A., Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Tineo, P., Gonzalez, K., & Butt, M. (2021). Skin color matters in the latinx community: A call for action in research, training, and practice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 43(1–2), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986321995910

- Garcini, L. M., Vázquez, A. L., Abraham, C., Abraham, C., Sarabu, V., & Cruz, P. L. (2024). Implications of undocumented status for latinx families during the COVID-19 pandemic: A call to action. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158837

- Ginsburg, K. R., & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697

- Gonzales, M. (2020). La Querencia. The genízaro cultural landscape model of community land grants in Northern New Mexico. In V. Fonseca-Chavez, L. Romero, & S. R. Herrera (Eds.), Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico homeland (pp. 243–268). University of New Mexico Press.

- Gonzales, R. G., Brant, K., & Roth, B. (2020). Dacamented in the age of deportation: Navigating spaces of belonging and vulnerability in social and personal lives. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1667506

- González, R. V. (2019). Quinceañera style: Social belonging and latinx consumer identities. University of Texas Press.

- Gonzalez, C. J., Aristega Almeida, B., Corpuz, G. S., Mora, H. A., Aladesuru, O., Shapiro, M. F., & Sterling, M. R. (2021). Challenges with social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic among hispanics in New York City: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11939-7

- Gorman, L. (2020). Remapping patriotic practices. The case of Las Vegas 4th of July Fiestas. In V. Fonseca-Chavez, L. Romero, & S. R. Herrera (Eds.), Querencia: Reflections on the New Mexico homeland (pp. 32–53). University of New Mexico Press.

- Graber, K. M., Byrne, E. M., Goodacre, E. J., Kirby, N., Kulkarni, K., O’Farrelly, C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2021). A rapid review of the impact of quarantine and restricted environments on children’s play and the role of play in children’s health. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12832

- Handal, A. J., Iglesias-Ríos, L., Fleming, P. J., Valentín-Cortés, M. A., & O’Neill, M. S. (2020). “Essential” but expendable: Farmworkers during the COVID-19 pandemic—the michigan farmworker project. American Journal of Public Health, 110(12), 1760–1762. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305947

- Hannah-Jones, N. (2021). The 1619 project: A new origin story. One World.

- Hazlehurst, M. F., Muqueeth, S., Wolf, K. L., Simmons, C., Kroshus, E., & Tandon, P. S. (2022). Park access and mental health among parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13148-2

- Hernández, T. K. (2022). Racial innocence: Unmasking latino anti-black bias and the struggle for equality. Beacon Press.

- Hersey, T. (2022). Rest is resistance: A manifesto. Hachette UK.

- Hibel, L. C., Boyer, C. J., Buhler-Wassmann, A. C., & Shaw, B. J. (2021). The psychological and economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on latina mothers in primarily low-income essential worker families. Traumatology, 27(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000293

- Hillis, S. D., Blenkinsop, A., Villaveces, A., Annor, F. B., Liburd, L., Massetti, G. M., Demissie, Z., Mercy, J. A., Nelson III, C. A., Cluver, L., Flaxman, S., Sherr, L., Donnelly, C. A., Ratmann, O., & Unwin, H. J. T. (2021). COVID-19–associated orphanhood and caregiver death in the United States. Pediatrics, 148(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053760

- Iglesias-Rios, L., O’Neill, M. S., & Handal, A. J. (2023). Climate change, heat, and Farmworker Health. Workplace Health & Safety, 71(1), 43–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/21650799221135581

- Jung, M. K., & Vargas, J. H. C. (2021). Antiblackness. Duke University Press.

- Katznelson, I. (2005). When affirmative action was white: An untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America. WW Norton & Company.

- Kuehn, B. M. (2021). Why farmworkers need more than new laws for protection from heat-related illness. JAMA, 326(12), 1135–1137. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.15454

- Leath, S. C., Mims, L., & Inniss-Thompson, M. N. (2023, May). Editorial: Freedom dreaming futures for black youth: Exploring meanings of liberation in education and psychology research. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1215719. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1215719

- Lebrón, A. M., Torres, I. R., Kline, N., Lopez, W. D., ME, D. T. Y., & Novak, N. (2023). Immigration and immigrant policies, health, and health equity in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly, 101(S1), 119–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12636

- Lopez, W. D. (2019). Separated: Family and community in the aftermath of an immigration raid. JHU Press.

- Marchi, R. M. (2022). Day of the dead in the USA: The migration and transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. Rutgers University Press.

- Martín-Baró, I. (1990). Reparations: Attention must Be paid–healing the body politic in Latin America. Commonweal, 117(6), 184.

- Martínez, R. A. (2014). Counter culture youth: Immigrant rights activism and the undocumented youth vanguard. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/27

- Mayol-Garcia, Y. (2022). 90% of hispanic parents shared frequent meals with their children. U.S. Census. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/10/family-dinner-more-common-hispanic-and-immigrant-families.html#:~:text=Family%20dinners%20have%20long%20been,to%20follow%20the%20cherished%20ritual

- Meléndez Guevara, A. M., Lindstrom Johnson, S., Elam, K., Hilley, C., Mcintire, C., & Morris, K. (2021). Culturally responsive trauma-informed services: A multilevel perspective from practitioners serving latinx children and families. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00651-2

- Montoya-Galvez, C. (2023). Biden expands title 42 expulsions while opening legal path for some migrants. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/immigration-biden-title-42-expansion-legal-path-migrants/

- Neville, H. A. (2017, February). The role of counseling centers in promoting well- being and social justice. Keynote address presented at the Big Ten Counseling Centers Conference, Champaign, IL.

- Neville, H. A., & Cokley, K. (2022). Introduction to special issue on the psychology of black activism: The psychology of black activism in the 21st Century. Journal of Black Psychology, 48(3–4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/00957984221096212

- Olayo-Méndez, A., Vidal De Haymes, M., García, M., & Cornelius, L. J. (2021). Essential, disposable, and excluded: The experience of Latino immigrant workers in the US during COVID-19. Journal of Poverty, 25(7), 612–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2021.1985034

- Penner, F., Ortiz, J. H., & Sharp, C. (2021). Change in youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in a majority hispanic/latinx US sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027

- Physicians for Human Rights. (2022). “Part of my heart was torn away”. What the U.S. Government owes the tortured survivors of family separation. https://phr.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/PHR_-Report_Deported-Parents_2022.pdf

- Polo, A. J., Solano-Martinez, J. E., Saldana, L., Ramos, A. D., Herrera, M., Ullrich, T., & DeMario, M. (2024). The epidemic of internalizing problems among latinx adolescents before and during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2023.2169925

- Reznick, A. (2022). Report finds pandemic-era border restrictions weren’t enacted on public health grounds. Fronteras. https://fronterasdesk.org/content/1818427/report-finds-pandemic-era-border-restrictions-werent-enacted-public-health-grounds

- Roberts, B. K., Nofi, C. P., Cornell, E., Kapoor, S., Harrison, L., & Sathya, C. (2023). Trends and disparities in firearm deaths among children. Pediatrics, 152(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-061296

- Robles-Ramamurthy, B., & Fortuna, L. R. (2023). Editorial: Institutional commitment is needed to promote antiracist care of unaccompanied immigrant minors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(11), 1185–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.03.010

- Rodriguez, C. M., Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., & Pu, D. F. (2021). The perfect storm: Hidden risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Maltreatment, 26(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520982066

- Rodriguez Vega, S. R. (2023). Drawing deportation: Art and resistance among immigrant children. NYU Press.

- Rojas Perez, O. F., Silva, M. A., Galvan, T., Moreno, O., Venta, A., Garcini, L., & Paris, M. (2023). Buscando la Calma Dentro de la tormenta: A brief review of the recent literature on the impact of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies on stress among latinx immigrants. Chronic Stress, 7, 24705470231182475. https://doi.org/10.1177/24705470231182475

- Rubio-Hernandez, S. P., & Ayón, C. (2016). Pobrecitos los niños: The emotional impact of anti-immigration policies on Latino children. Children and Youth Services Review, 60, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.11.013

- Saboroff, J. (2021). More than 2,100 children separated at border ‘have not yet been reunified,’ Biden task force says. NBC news. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/more-2-100-children-separated-border-have-not-yet-been-n1269918

- Sacchetti, M., & Sullivan, S. (2022). Biden says separated migrant families deserve compensation. But in court, the Justice Dept. says they’re not entitled to it. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/biden-separated-families-court-migrants/2022/01/12/5c592f74-725a-11ec-8b0a-bcfab800c430_story.html

- Salas, S., Jones, J. P., Perez, T., Fitchett, P. G., & Kissau, S. (2013). Habla con ellos—talk to them: Latinas/Os, achievement, and the middle grades: Moving bilingual children beyond subordinated categories toward full engagement in relevant and authentic learning that embraces their communities. Middle School Journal, 45(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2013.11461878

- Salerno, J. P., Devadas, J., Pease, M., Nketia, B., & Fish, J. N. (2020). Sexual and gender minority stress amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for LGBTQ young persons’ mental health and well-being. Public Health Reports, 135(6), 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920954511

- Salgado de Snyder, V. N., McDaniel, M., Padilla, A. M., & Parra-Medina, D. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on latinos: A social determinants of health model and scoping review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 43(3), 174–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863211041214

- Salinas, J. L., & Salinas, M. (2022). Systemic racism and undocumented latino migrant laborers during COVID-19: A narrative review and implications for improving occupational health. Journal of Migration and Health, 5, 100106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100106

- Sanchez, D., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Capielo Rosario, C., Torres, L., Webb, L., & Stoto, I. (2024). Racial differences in discrimination, coping strategies, and mental health among US Latinx adolescents during COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1537416.2024.2301702

- Sanchez, D., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Wagner, K. M., Cadenas, G. A., Torres, L., & Cerezo, A. (2022). COVID-19 stressors, ethnic discrimination, COVID-19 fears, and mental health among latinx college students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000448

- Sherer, J., & Mast, N. (2023). Child labor laws are under attack in states across the country. Economic Policy Institute. https://files.epi.org/uploads/263680.pdf

- Silva, E. (2020). Chicano English at the dinner table. Electronic theses, projects, and dissertations. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1128/

- Sostre, J. P., Abreu, R. L., Vincent, D., Lockett, G. M., & Mosley, D. V. (2023). Young black trans and gender-diverse activists’ well-being among anti-black racism and cissexism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000627.

- Sroufe, L. A., Szteren, L., & Causadias, J. M. (2014). El apego como un sistema dinámico: Fundamentos de la teoría del apego. In B. Torres Gómez de Cádiz, J. M. Causadias, & G. Posada (Eds.), La teoría del apego: Investigación y aplicaciones (pp. 27–39). Psimática.

- State-Funded Health Coverage for Immigrants as of July 2023. (2023, July 10). KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/state-funded-health-coverage-for-immigrants-as-of-july-2023/

- Stein, G. L., Salcido, V., & Gomez Alvarado, C. (2024). Resilience in the time of COVID-19: Familial processes, coping, and mental health in latinx adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158838

- Stodolska, M., & Santos, C. A. (2006). Transnationalism and leisure: Mexican temporary migrants in the US. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(2), 143–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2006.11950073

- Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Balcazar, F., Torres, M. G., Garcia, C., & Arias, D. L. (2022). Goal setting with Latinx families of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Case studies. Behavior & Social Issues, 31(1), 194–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42822-022-00094-2

- Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Mirza, M., Errisuriz, V. L., Zeng, W., Brown, J. P., Vanegas, S. … Magaña, S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and well-being of latinx caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157971

- Valdez, C. R., Walsdorf, A. A., Wagner, K. M., Salgado de Snyder, V. N., Garcia, D., & Villatoro, A. P. (2022). The intersection of immigration policy impacts and COVID‐19 for latinx young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 70(3–4), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12617

- Vargas, E. D., & Sanchez, G. R. (2020). COVID-19 is having a devastating impact on the economic well-being of latino families. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, 3(4), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00071-0

- Vega, G. P., McGill, C. M., Duran, A., & Rocco, T. S. (2023). Familismo, religiosidad, and marianismo: college latina lesbians navigating cultural values and roles. Journal of Latinos and Education, 22(5), 1939–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2022.2071899

- Venta, A., Bautista, A., Garcini, L. M., Silva, M., Mercado, A., Perez, O. F. R., Pimentel, N., & Hampton, K. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 on unaccompanied immigrant minors and families: Perspectives from clinical experts and providers. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158841

- Villatoro, A. P., Wagner, K. M., Salgado de Snyder, V. N., Garcia, D., Walsdorf, A. A., & Valdez, C. R. (2022). Economic and social consequences of COVID-19 and mental health burden among latinx young adults during the 2020 pandemic. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 10(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000195

- Walker, R. (2020). The unapologetic guide to black mental health: Navigate an unequal system, learn tools for emotional wellness, and get the help you deserve. New Harbinger Publications.

- Wasil, A. R., Gillespie, S., Schell, T., Lorenzo‐Luaces, L., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2021). Estimating the real‐world usage of mobile apps for mental health: Development and application of two novel metrics. World Psychiatry, 20(1), 137–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20827

- Ybarra, M., & Lua, F. M. (2023). No calm before the storm: Low-income latina immigrant and citizen mothers before and after COVID-19. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 9(3), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2023.9.3.07

- Young Adult Expansion. (2022, November 15). Department of health care services, State of California. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal/eligibility/Pages/youngadultexp.aspx.

- Young, M. E. D. T., Tafolla, S., & Perez‐Lua, F. M. (2023). Caught between a well‐intentioned state and a hostile federal system: Local implementation of inclusive immigrant policies. The Milbank Quarterly, 101(4), 1348–1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12671

- Zongrone, A. D., Truong, N. L., & Kosciw, J. G. (2020). Erasure and resilience: The experiences of LGBTQ students of color. In Latinx LGBTQ youth in US Schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN).