Abstract

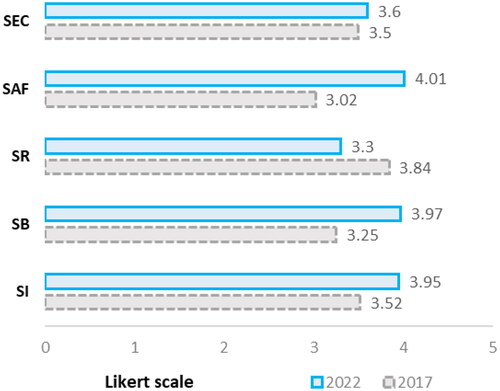

Pedestrianization is a prevalent strategy, especially in urban centers, aimed at creating safer and more vibrant environments. However, there remains a conspicuous absence of studies exploring the social consequences of pedestrianization in the Middle East (ME). This research aims to bridge this gap by assessing the social impacts of pedestrianization on Chaharbagh Abbasi Pedestrian Street (ChAPS), a historical social hub of Isfahan, a city in the heart of Iran, which was revitalized from a car-oriented to a car-free street between 2017 and 2020. We focused on five independent factors: social interaction (SI), sense of belongingness (SB), sense of responsibility (SR), security (SEC), and safety (SAF). Data from 984 in-person questionnaires and online surveys were analyzed via SPSS and ArcGIS, and pre- and post-project outcomes were compared. The findings indicate an improvement in SAF, SB, and SI, a negligible change in SEC, and an unexpected decrease in SR post-pedestrianization. Specifically, SI improved for 60% of visitors and 72% of urban residents reliant on public transportation. SAF increased by 97% and 80% for city inhabitants and visitors, respectively, while SEC witnessed minimal progress of under 10% for both groups. Despite SB achieving a remarkable improvement of 93%, SR surprisingly decreased by 21.5% for those living far from ChAPS. The study aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), indicating the pedestrianization project’s contribution to social sustainability to a large extent. However, further efforts are needed to fully meet SDG sub-indicators. This study provides practical guidelines for urban planners intending to enhance social sustainability through built environmental planning at the city level in the ME.

Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework to protect the future of the planet, in particular the harmonious coexistence between humans and the natural environment (Cohen Citation2021; United Nations Citation2015). To be more precise, it has been approximately one decade since the United Nations adopted the SDGs to address global unsustainability issues and promote prosperity for all people by 2030 (Blasi, Ganzaroli, and Noni Citation2022). To verify the accomplishment of the 17 SDGs, 169 targets were defined by 2030 with various indicators (United Nations Citation2015). Within the realm of urban projects and interventions, the social dimension plays the most crucial role in evaluating its impact on people’s quality of life (Mouratidis Citation2021; Rogers, Gardner, and Carlson Citation2013). A strategic problem occurs if these projects instigate unwelcome social consequences as their expected benefits and credibility will be diminished (Rogers, Gardner, and Carlson Citation2013). Social indicators related to the SDGs include population, poverty levels, gender equality, nutrition, child mortality, education, housing, crime, employment, sanitation levels, and health measures (Rogers, Gardner, and Carlson Citation2013). These factors should be studied both in pre- and post-urban revitalization projects, such as pedestrianization, to investigate the tangible effects and achievements of particular development plans on communities (Yassin Citation2019).

Pedestrianization is a built-environment project that can boost livability and sustainability by restricting access to private vehicles in certain areas of the city (Guillen-Royo Citation2022; Shahmoradi, Abtahi, and Guimarães Citation2023; Yassin Citation2019; Yoshimura et al. Citation2022). Urban open spaces in many city centers used to be a place to gather and fulfill urban life desires such as social, political, religious, and commercial activities along with public entertainment (Salimi and Al-Ghamdi Citation2020; Yasin, Tariq, and Najeeb Citation2021). However, the continuous worldwide growth of motorization and increased urban traffic in the last decades of the twentieth century posed threats to pedestrian safety and subsequently decreased communal activities (Chen, Liu, and Tao Citation2013; Dičiūnaitė-Rauktienė et al. Citation2018). Likewise, central business districts and historical urban centers gradually confronted unsustainability crises due to traffic, pollution, and degradation (Özdemir and Selçuk Citation2017). To address these challenges, car-restriction measures and active travel modes attracted the attention of urban planners worldwide toward a sustainable urban environment, aiming to reduce pollution, overall carbon emissions, and urban heat islands (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2020; Ortega et al. Citation2020), preserve historical buildings, improve environmental quality, promote face-to-face social interactions, revitalize local economies, and restore shopping activities in the city centers (Yassin Citation2019). This strategy has also expanded people’s access to and understanding of historical places, safe walking, and streetscape watching that meet modern humanity’s cultural and social demands by removing traffic barriers from the consolidated urban fabric (Özdemir and Selçuk Citation2017).

A broad range of research has investigated the impacts of pedestrianization in various locations globally, including streets, malls, and plazas (Blečić et al. Citation2020; Parajuli and Pojani Citation2018), with a focus on economic and environmental consequences (Hahm, Yoon, and Choi Citation2019; Volker and Handy Citation2021). However, a notable gap exists in the literature regarding the social impacts of pedestrianization in ME cities. The research question is whether implementing pedestrianization in a historical ME city contributes to a more sustainable society. In response, Chaharbagh Abbasi Pedestrian Street (ChAPS) in Iran was considered as our case study. This particular site was selected because planners and designers have developed a people-focused concept of public spaces that has contributed to increasing the attractiveness of the area and communication among people who frequent the street. The research objectives of the project reported here were threefold. First, we sought to unfold the effects of pedestrianization of Chaharbagh Abbasi Street on each of the five dimensions of social interaction, sense of belongingness, sense of responsibility, security, and safety. Second, the study sought to compare the outcomes of post-implementation with the results of the surveys accomplished in the pre-project period. Finally, we aimed to depict location-based social impacts of pedestrianization for urban residents. The research methodology involved collecting data from visitors (including both domestic and foreign tourists) and city inhabitants through in-person and online questionnaires, respectively. Location-based social analysis for city dwellers is considered a novelty in the study of the ME region, particularly for the municipality and decision makers of Isfahan city. The approach of this research was designed to evaluate urban socialization, to assess the most and least socially affected urban regions with pedestrian policies, and to inform decision makers regarding further pedestrianization practices in similar historical cities. Our research is structured as follows. In the next section, we provide a literature review. The third section outlines our methodology, including information about the performed questionnaires, data gathering, case study, data processing, and analysis. The fifth section discusses these results, outlines our policy suggestions, and offers directions for further research. Lastly, we conclude this study in the final section.

Literature review

Encouraging people to walk or cycle, known as active transportation (AT) (Mouratidis Citation2021), not only promotes healthier lifestyles through improved physical and mental health, but also facilitates social interactions in public spaces (Chatman, Broaddus, and Spevack Citation2019; Mueller et al. Citation2015), which may lead to socialization and social cohesion (Askarizad and Safari Citation2020). The pedestrian street is practical for the entire population regardless of socioeconomic background, thereby promoting social equity and sustainable relations as well (Jamei et al. Citation2021). In addition, this policy, by progressing social activities, such as public surveillance, can reduce the crime rate and provide a safe environment for people (Soni and Soni Citation2016). In an urban historical fabric with established ancient forms in collective memory, pedestrianization can be a sensible strategy. It is not only for the aforementioned reasons, but it can also increase visitors’ level of satisfaction and sense of belonging to the area (Nursyamsiah and Setiawan Citation2023) and contribute to their sense of responsibility (Soni and Soni Citation2016), which is sometimes referred to as the soul of social sustainability (Rogers, Gardner, and Carlson Citation2013). In this regard, Blečić et al. (Citation2020) defined the factors of “walkability” which involve efficiency and comfort, safety, security, pleasantness, and attractiveness. Furthermore, Soni and Soni (Citation2016) classified the merits of pedestrianization including the provision of social interactions and relations, a sense of belonging, responsibility and pride, the increment of security and safety, the preservation of heritage, the management of renewable urban resources, and the improvement of livability (). Due to the wide scope of sustainability and several indicators, this study focused on five main factors through which we can analyze the evolution of social sustainability in the pedestrian area of Chaharbagh Abbasi Pedestrian Street (ChAPS) located in the Iranian city of Isfahan. According to the findings of Soni and Soni (Citation2016), these are social interaction (SI), sense of belonging (SB), sense of responsibility (SR), security (SEC), and safety (SAF).

Table 1. Built environment and social sustainability factors.

While numerous international cities have embraced pedestrianization by transitioning from car-oriented to people-focused transportation, the implementation and success of these initiatives have varied across different regions (Mueller et al. Citation2015). Germany was the first country in Europe to introduce pedestrianization (in the city of Essen) in 1926 (Özdemir and Selçuk Citation2017), inspiring a number of European cities in the early 1960s to turn parts of their centers into car-free zones (Yasin, Tariq, and Najeeb Citation2021). In the United States, this scheme was initiated with the first pedestrian mall in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1959. The trend expanded gradually, approximately reaching 200 cities (Yassin Citation2019). Furthermore, the first pedestrian malls in Australia were implemented in the late 1970s, similar to their North American counterparts (Parajuli and Pojani Citation2018). Up until now, many European, Australian, and Asian cities have developed pedestrianization projects, especially in city centers, which indicates that pedestrian streets and pedestrian malls have proven to be a popular form of urban (re)development (Parajuli and Pojani Citation2018). Still, the acceptance of this type of planning intervention differs across global regions and countries and is often associated with local or national characteristics. For instance, Parajuli and Pojani (Citation2018), noted that the dominance of car culture in most American cities poses limitations on the proliferation of pedestrianization initiatives in the country. Additionally, Smart and Klein (Citation2020) argued that car ownership is associated with better employment opportunities, greater job security, and a higher overall quality of life over time for individuals in the United States (Smart and Klein Citation2020).

The Middle East (ME), located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, is unique both historically and geopolitically (Held and Cummings Citation2018). In this region, pedestrianization has gained momentum among developing countries, including Iran, for several reasons. First, rapid urbanization in the ME has led to traffic congestion, air pollution, and other unsustainable issues in the cities (Bayomi and Fernandez Citation2019). Second, this area, being the cradle of the first civilizations and a treasure trove of cultural heritage, is the birthplace of the great monotheistic religions. The region maintains many global tourist destinations and its attractions should also be preserved for future generations (Held and Cummings Citation2018). Finally, there is a need to reduce the ME’s economic dependency on nonrenewable resources by enhancing local businesses and the tourism industry (Khan et al. Citation2020). However, pedestrianization policy in the ME may differ from other global regions due to complex social dynamics, traditional values, and specific social norms (El-Ghonaimy and Al-Haddad Citation2019; Held and Cummings Citation2018). These factors may influence the type of public space use, social interactions, place attachments, sense of responsibility, security, and safety. Furthermore, the high costs associated with these projects pose financial burdens for countries in the ME with lower incomes. Consequently, assessing the potential impacts of pedestrianization on communities can reduce the risk of both failure and untenable financial burdens for developing nations in the region.

In recent years, scholars have devoted more attention to the connection between social sustainability and the built environment in various urban areas (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Liu et al. Citation2017; Yıldız et al. Citation2020). For instance, Liu et al. (Citation2017) defined social sustainability in close connection with quality of life and suggested a conceptual framework, with specific reference to China, composed of two components: well-being and social justice. In another study, Eizenberg and Jabareen (Citation2017) provided a conceptual framework of social sustainability, including equity, safety, eco-presumption (which involves consuming, producing, and gaining value in socially and environmentally responsible ways), and other factors relevant to urban form. They concluded that a desired physical form can enhance the social aspects of health, place attachment, and safety among other environmental objectives. Yıldız et al. (Citation2020), working from the vantage point of Istanbul, presented a model to explain the relationship between built environmental design and social sustainability via five variable groups of accessibility and quality of social life, conservation of resources, quality of the built environment, protection of disadvantaged groups, and commercial and economic opportunities. They found that accessibility and quality of social life is the most important factor compared to the others in enhancing social sustainability in a built environment project. In 2021, Mouratidis (Citation2021) reviewed seven potential pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being, including travel, leisure, work, social relationships, residential well-being, emotional responses, and health (). Another study conducted in Bahrain highlighted the importance of considering the ethnicity of residents when designing the built environment. The research suggested that traditional areas may suffer from a loss of identity and heritage due to excessive modernization and neglect of stakeholders’ traditional culture (El-Ghonaimy and Al-Haddad Citation2019).

Materials and methods

Data gathering and analyses

This research investigates the social effect of Charbagh Abbasi pedestrianization on the community of Isfahan and we designed a questionnaire to solicit views not only with respect to the street itself but also concerning its surroundings. The study engaged two main categories of respondents as project stakeholders (Rivai, Rohman, and Sumantri Citation2023) and involved two phases of data collection. The first category comprised pedestrians visiting ChAPS (mobile users) and the second category consisted of random residents living in 15 different urban districts of Isfahan (Shahmoradi, Abtahi, and Guimarães Citation2023; Ujang Citation2012). In our study, according to Cochran and Morgan’s table, the statistical sample size was equal to 384. To ensure the representativeness of our samples, we exceeded this size for both types of stakeholders. For the first category (visitors), we randomly selected 400 tourists present in ChAPS during the data-collection period. The questionnaires were conducted during the Nowruz festivities, Eid al-Fitr holidays, and on weekends from March 2022 to May 2022. This time frame was chosen due to its high touristic activity in the country and we collected 396 valid paper questionnaires with a gender distribution of 57% women and 43% men. For the second category of stakeholders (city inhabitants), we selected all 15 urban districts based on the definition provided by the Isfahan municipality. During this process, we randomly surveyed 45 participants from each urban district via an online link between early June 2022 and July 2022. This resulted in a total of 588 valid responses with a generally equal balance of 49% males and 51% females, which was deemed sufficient for statistical analysis as well.

The data collected from these questionnaires were further compared with data from the Municipality of Isfahan collected in a pre-project phase in 2017 that involved a random survey of 812 residents of Isfahan. Of these, 362 were surveyed in Chaharbagh Abbasi Street and 450 completed the questionnaire in other districts of the city. The majority of respondents fell within the age range of 20–35 years old (MATFA Citation2017).

To ensure the ethical conduct of our study, we obtained informed consent from all participants and guaranteed all the respondents’ privacy terms and conditions. The questionnaire was designed based on our social evaluation framework, which includes social interaction (SI), sense of belonging (SB), responsibility (SR), security (SEC), and safety (SAF). The first section of the questionnaire contained general demographic questions such as gender, level of education, location of residence, and physical disability. In the next section, both urban inhabitants and visitor participants were asked to grade the SI factors for the street. They were questioned about how much space was provided in the ChAPS for chatting, watching, sitting, and social interactions after pedestrianization. How often do they visit ChAPS as city inhabitants/how much do they desire to visit it again as tourists in the future? To what extent can less physically able people (disabled, elderly, children) use this space fairly with others? The third part was specialized for city inhabitants regarding SB and SR. Accordingly, the questionnaire contained items about current SB. They also graded their level of interest in financial and non-financial participation for future improvement of ChAPS. In the final section, we collected both city inhabitants’ and visitors’ perceptions SEC and SAF. Respondents were questioned about their level of satisfaction with night light, their sense of security when they were present in that place, the security provided for sensitive groups of women, children, and the elderly 24 hours a day, and the criminal acts visitors might have experienced in the area. They were also asked about their sense of safety against traffic crashes, risk, or injury to walking freely in the pedestrian street after Chahrbagh Abbasi Street’s pedestrianization. It should be noted in the present study that we encountered the government’s refusal to provide official safety and security data due to precautionary reasons. Therefore, the investigation of SAF and SEC dimensions was conducted merely through empirical analysis and surveying people’s sense of security and safety.

All the items on the questionnaire were structured on a 5-point Likert scale that evolved around the social dimensions before and after the project. We used multiple questions to assess some social dimensions, which assisted in triangulating the data and increasing its validity. The comparisons of social analyses of pre- and post-pedestrianization results for groups of both city inhabitants and visitors were conducted via SPSS version 26. The variable coefficients were restricted to the 5% statistical level. In addition, as the questionnaires included the residence location of each respondent, it was possible to develop a spatial distribution of respondents by inputting the data into ArcGIS. The resultant map includes variations according to the answers collected in each district.

Case study

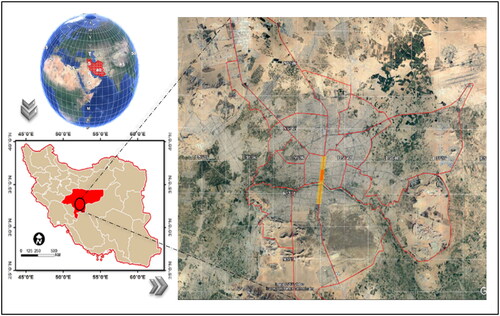

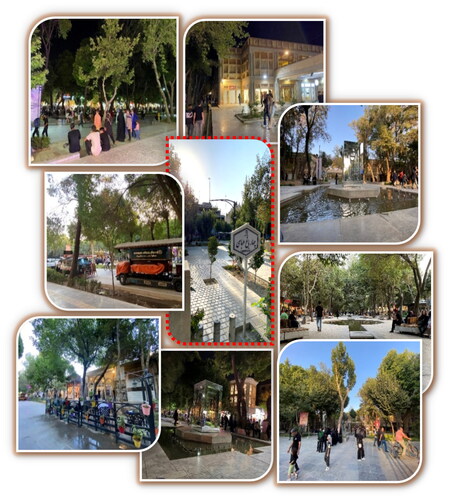

The case study focuses on the city of Isfahan in Iran (), which is the second largest in the country in terms of population and the largest country in geographic size in the ME and holds a significant place in world history as one of the oldest nations with a known civilization (Danaei et al. Citation2019). A leading visitor destination in Iran, Isfahan is located in the central part of the country and has a rich historical heritage (Bagheri and Shaykh-Baygloo Citation2021). The city is situated at latitude 32° 39′ North and longitude 51° 40′ East and has a population exceeding 2 million people spread across 15 various urban districts (MATFA Citation2017). The field study specifically centers around Chaharbagh Abbasi Street, a prominent commercial thoroughfare in Isfahan. The street holds historical significance as it is part of the 5.5 kilometer (km) north-south boulevard with this same name which has served as the backbone of the city throughout history (Mansourianfar and Haghshenas Citation2018; Shahmoradi, Abtahi, and Guimarães Citation2023). Chaharbagh Abbasi Street itself spans 1.2 km and is located in the heart of the city, between two notable historical landmarks: Naqsh Jahan Square (a World Heritage Site since 1979 as recognized by the United Nations Scientific, Educational and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)) and the Thirty-Three Bridges spanning the Zayanderud River (Shahmoradi, Abtahi, and Guimarães Citation2023). Chaharbagh Abbasi Street has long been a place for social and leisure activities and traditional events, which gradually found a new role in urban commerce (MATFA Citation2017). It has been less than a decade since the pedestrianization scheme was started (2017) and accomplished (2020) on this street by the Municipality of Isfahan ( and ). It is worth noting that at the time of the study, there was one active metro line in Isfahan stretching from north to south for almost 20 km and including a total of 20 stations with two stations located in this pedestrian area.

Results

Social interaction (SI)

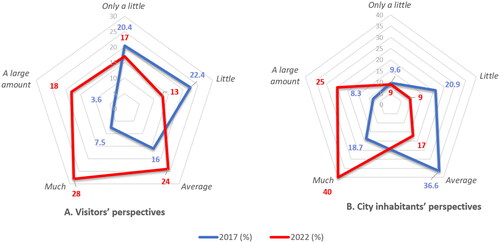

As illustrated in , in 2017, about 43% of visitors and 31% of city inhabitants held the view that Charbagh Abbasi Street did not contain sufficient space for social activities such as sitting, watching, and chatting. In the 2022 survey, after completion of the pedestrianization project, 70% of visitors and 82% of city inhabitants confirmed that ChAPS provided enough social space for them. The term “enough” here refers to the sum of the percentages of average, much, and a large amount value.

Figure 4. The change of social space in Chaharbagh Abbasi: city inhabitants’ and visitors’ perspectives. Source: authors survey (2022) and surveys performed by Municipality of Isfahan (2017).

According to the social interaction results reported in , while 39.7% of visitors in the pre-project survey (2017) predicted that social interaction would not change after pedestrianization, the 2022 questionnaires revealed a very different perception as 60% of respondents asserted that social interaction in the pedestrian zone increased and significantly expanded in total. Similarly, only half of the city inhabitants in the pre-project phase (52.7%) were optimistic about SI growth after the pedestrianization scheme. Nonetheless, the results demonstrate that 72% of the city inhabitants affirmed that social interaction increased (increased and significantly increased) after pedestrianization ().

Table 2. Changes in pre- and post-pedestrianization in social interaction: city inhabitants’ and visitors’ perspectives.

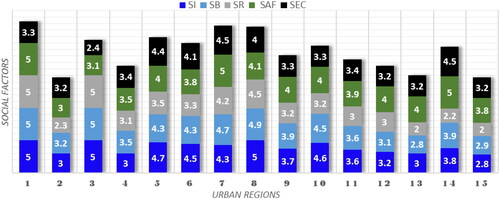

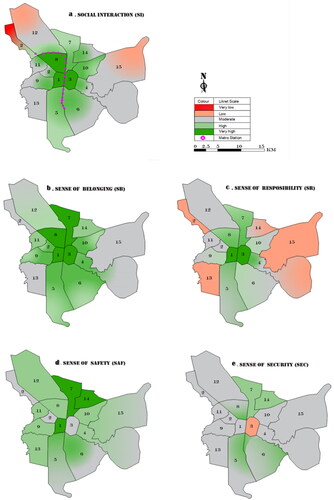

In this research, a schematic spatial analysis of the desire for social interaction in pedestrian areas is displayed in . According to this map, it is possible to confirm that there is a spatial distribution of respondents’ assessments on the evolution of social interaction along the street. Respondents who resided in the areas designated as 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 10 rated higher social interaction and activity in ChAPS. In contrast, fewer residents of areas 2, 12, and 15 reported willingness to travel to the street for social activities.Footnote1 According to the open-ended questions in our survey, the presence of city inhabitants in the area is mainly related to accessibility. This means that people who reach this area without a car have more opportunities to visit the pedestrian area and socialize than other city inhabitants who do not live near the pedestrian street or do not have easy access to public transportation. Therefore, residents of areas near Metro Line 1 were more likely to visit ChAPS, and this relationship held for both men and women of all ages. They could easily travel to the street, whereas residents of area 15 and northern parts of area 12, which are further away and have insufficient public transportation, had the least desire to socially interact in this pedestrianized street ().

Figure 5. Which urban areas impact on the SI, SB, SR, SAF, and SEC* of Chaharbagh Abbasi Pedestrian Street and to what extent? Source: The map was adapted from the Municipality of Isfahan and modified by the authors. *Abbreviation: SI, social interaction; SB, sense of belonging; SR, sense of responsibility; SAF, sense of safety; SEC, sense of security.

Sense of belonging (SB)

In the 2017 survey, about 70% of city inhabitants declared their sense of belonging to Chaharbagh Abbasi Street, of which approximately 43% had a strong place attachment. However, in 2022, those numbers increased considerably to 93%, of which 64% reported a strong place-attachment to the street (). illustrates that city inhabitants’ sense of belonging to areas 2, 4, 13, and 15 of ChAPS was moderate while residents of other areas had a strong sense of belonging. To further elaborate, the 15th urban area was previously a separate town, Khorasgan, located 6 km from the city center of Isfahan but was annexed by the city in 2014. Furthermore, the 13th urban area, added in 2007 to the cityscape (Isfahan Municipality Citation2020), exhibited a relatively low degree of social engagement within its ChAPS environment. It can be concluded that the residents living far from the historical core do not have much place-attachment to the ancient monuments of the city as they have rare interaction with the place, and rarely spend time transiting or recreating there.

Table 3. Changes in pre- and post-pedestrianization in city inhabitants’ sense of responsibility and belonging.

Sense of responsibility (SR)

Even though the pedestrianization project encouraged city inhabitants to walk in public spaces, it was not able to meaningfully enhance their sense of responsibility. Our questionnaire sought to interrogate respondents on how much they financially supported the pedestrianized Chaharbagh Abbasi Street or to what extent they felt (non-financially) responsible for preserving the livability of ChAPS. In 2017, 63.5% of city inhabitants were willing to participate voluntarily (high and very high level of sense of responsibility). Surprisingly, having launched the pedestrian-street project, the percentage of expressly responsible city inhabitants declined to 42% in 2022. In total, their SRs were classified into three main levels: high (42%: high and very high), moderate (31%), and low (28%: low and very low) sense of responsibility ().

According to , the populations of urban areas 1 and 3 had the highest sense of responsibility for maintaining the viability and vitality of ChAPS in both financial and non-financial terms. Conversely, the lowest sense of responsibility was found in areas 2, 13, 14, and 15 and some parts of 4. The factors that create participation in a city are different, such as public awareness, degree of accessibility, personal financial situation, and sense of belonging (Shaykh-Baygloo Citation2020; Soni and Soni Citation2016). Considering the open-ended questions, we found that most residents in the south of the city were financially more capable than those in the north. However, due to personal reasons, they were unwilling to support the government in urban projects, as seen in some areas of districts 5 and 6. In addition, regions 2 and 14 comprised people who were financially disadvantaged. Furthermore, residents of areas 13 and 15 with some parts of 4 lacked a sense of belonging to this historical area. Despite this, residents of other areas were willing to participate in ChAPS.

Safety feeling (SAF)

Due to our lack of access to governmental data, we asked respondents about their level of safety feeling (SAF) in ChAPS. compares the perspectives of city inhabitants and visitors on SAF from 2017 to 2022. It displays an enormous advance in safety from 64.8% to 97% among city inhabitants and from 38.9% to 80% among visitors after implementation of the pedestrianization project.

Table 4. Changes in pre- and post-pedestrianization in sense of safety: city inhabitants’ and visitors’ perspectives.

As demonstrates, the populations of urban areas 1, 7, and 14 indicated that the case-study area became much safer against traffic hazards and accidents than it previously had been. According to our survey, there is no doubt that Chaharbagh Abbasi Street came to be perceived as safer with respect to motorized vehicles in the period following completion of pedestrianization. However, the average responses of the city inhabitants of the 3rd area (eastern side of ChAPS) indicated the lack of equal accessibility of urban emergency vehicles to all residential areas leading to ChAPS. Furthermore, the dwellers of the 2nd district of Isfahan mentioned their perception of low safety in Chaharbagh Abbasi Street. To better understand their concerns, we should investigate further as it might be related to their limited updated knowledge about the area’s recent revitalization. This is likely because they have not frequently visited the street, as indicated by their responses to previous questions ().

Security feeling (SEC)

Regarding our inability to access municipal data pertaining to this factor, the findings revealed that city inhabitants had a sense of security (SEC) at 82.2% in 2017, which increased to 85% in 2022, showing a marginal improvement. Likewise, almost three-quarters of the visitors were satisfied with the security of ChAPS in 2017, although their security perception increased to 85% in 2022 (). Considering surveys from respondents in both pre- and post-revitalized street, it appears that the ChAPS area has generally been secure for people, including Isfahan residences and visitors. Therefore, the pedestrianization of Chaharbagh Abbasi Street did not result in notable change in this regard.

Table 5. Changes in pre- and post-pedestrianization in sense of security: city inhabitants’ and visitors’ perspectives.

In , it is evident that residents of urban areas 1, 6, 7, 8, and 14 reported high feelings of security. Meanwhile, other respondents from areas experienced no significant change in their sense of security in ChAPS compared to the pre-project phase. However, in district 3, residents were not satisfied with the security of the pedestrian area. According to our open-ended questions, we found that this was due to a lack of night lighting, especially in the eastern part of the pedestrian area, half-constructed buildings or abandoned shops along the sidewalk, and reduced commercial activity and social vitality on the eastern side of ChAPS. These factors were likely to decrease the sense of security by providing potential hiding spots for perpetrators of criminal activity at night.

Spatiality of social sustainability

In , the average of the 5-point Likert scale for each social dimension is compared across different regions. Each region was assigned a total social score ranging from 5 (representing a weak status) to 25 (indicating a strong status). The findings suggest that all 15 urban areas within the city of Isfahan play a significant role in the experienced social sustainability of ChAPS while simultaneously being affected by it. Regarding the survey administered to city inhabitants and visitors, we found that region 1 had the most positive impact on the social sustainability of ChAPS, with a total score of 23.3. In contrast, region 3, located on the eastern side of the street, experienced a negative sense of security and safety, despite positive changes in other factors that we studied. Other regions 5, 6, 7, and 8 were in a favorable social situation according to the walking plan (see ). The primary success of ChAPS was in creating a safe atmosphere for the majority of users, as it improved by one Likert level after the project. However, urban residents’ responsibility was not fully recognized. Overall, ChAPS was estimated to be a sustainable social project, except for the public participation factor (see ).

Discussion

Despite extensive research by scholars on pedestrianization, the social effects of this type of policy in ME cities have received limited attention. It remains unclear whether implementing pedestrianization in a historical ME city contributes to the social sustainability of the place and urban areas surrounding it. The main objective of this research was to explore the social impact of pedestrianization schemes on communities in urban spaces, bridging the knowledge gaps in the less studied geographical contexts. Hence, we presented a practical method to investigate five dimensions of SI, SR, SB, SAF, and SEC. ChAPS, a revitalized area in Isfahan was considered as our case study. The study revealed that the majority of the participants had a generally positive outlook on the social effects of the pedestrianization project. Following the ban on motorized vehicles, SAF, SI, and SB witnessed significant growth in this historical region. The SEC experienced fractional growth post-ChAPS. Surprisingly, despite the strong attachment of city dwellers to the pedestrianized area, their SR declined in comparison to the pre-project phase.

While pedestrianized streets restrict motorized mobility, there are indications that such projects provide adequate public area to promote face-to-face communication, social interactions (Boessen et al. Citation2018), and even shopping activities (Soni and Soni Citation2016; Volker and Handy Citation2021). In 2022, by offering adequate space for activities like sitting, watching, and talking, people experienced a certain level of happiness in city life. This enjoyment relies on social ties among residents, as supported by studies of Diener et al. (Citation2018) and Mouratidis (Citation2021). The growth in SI within ChAPS demonstrated the acceptance of this area as an appealing environment for stakeholders, including city residents and visitors. In addition, the finding is consistent with previous research conducted by Shafik and El-Husseiny (Citation2019) and Yıldız et al. (Citation2020) in Egypt and Turkey, respectively. They discovered that built environment practices, such as green urban spaces and parks, can result in increased social interaction and a sense of community. Similarly, our outcome corresponds with research by Shahmoradi, Abtahi, and Guimarães (Citation2023) which showed an increase in pedestrian volume following a pedestrianization project. Other studies, as mentioned in our theoretical framework, have also validated our SI results (Askarizad and Safari Citation2020; Chatman, Broaddus, and Spevack Citation2019; Mueller et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, our visualized findings emphasize the importance of accessibility to public transportation as a vital pedestrian facility in promoting social interaction in ChAPS. This notion is supported by the outcomes of other studies, including those by Hahm, Yoon, and Choi (Citation2019), Jamei et al. (Citation2021), and Yıldız et al. (Citation2020). This work has demonstrated that carefully designed and well-built environments can attract more visitors and increase social interaction immediately after the project’s completion (Hahm, Yoon, and Choi Citation2019; Jamei et al. Citation2021).

When it comes to SB, a walking strategy enhances local attachment to the intervention area. Post-ChAPS, the growth in SB and SI is consistent with Nursyamsiah and Setiawan’s (Citation2023) study in Indonesia, which demonstrated that place attachment positively influences revisiting renovated parks and can boost SI. Furthermore, our work reveals a direct relationship between accessibility to the place and SB. This finding supports the conclusions drawn by Koohsari et al. (Citation2023) in Calgary (Canada). Their research identified implementation of an accessibility policy for pedestrians significantly boosted SB levels. Similarly, Nursyamsiah and Setiawan (Citation2023) confirmed that accessibility to place plays a key role in overall satisfaction with built environments, ultimately leading to a strong sense of place attachment.

SR is a crucial aspect of social sustainability that has received limited attention in the context of urban regeneration and built environment projects. This study showed unexpected outcomes, including a notable decrease among city inhabitants’ sense of responsibility toward ChAPS. Wang et al. (Citation2021) argue that the diverse interests of stakeholders in revitalization projects increase their complexity, necessitating the participation of decision-makers and others. However, the lack of public participation as a primary cause of conflicts between the public and various stakeholders (Zhuang et al. Citation2019), potentially undermining project success. Moreover, when political-economic interests overlap with the project goals, the opinions of people are not likely to be heard, and thereby the success of projects will be undermined (Uršič and Križnik Citation2012). Consequently, prioritizing public participation in urban projects becomes crucial. Such active involvement not only enhances social cohesion and local services but also ensures the long-term viability of pedestrianized areas (Xie, Liu, and Zhuang Citation2021; Yassin Citation2019). It is worth mentioning that the ChAPS project was started and proceeded without any public participation (Mehr News Agency Citation2019). Based on data from the questionnaires, the decline of interest in civic participation regarding the future of the area may stem from the lack of prior consultation with city inhabitants. This situation likely fostered a sense of distrust, particularly among affected retail businesses toward the government. Other possible justifications for this decrease include economic challenges for individuals, political and municipal reasons, as well as cultural attitudes regarding citizen engagement in urban regeneration.

In the context of our study, the pedestrian policy resulted in a high level of perceived SAF against accidents and vehicular hazards. This improvement was particularly pronounced when compared to the pre-project state. Functionally diverse streets, such as historical, commercial, and residential areas, tend to attract high daily traffic. Unfortunately, this often leads to conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles, leaving pedestrians vulnerable (Hu et al. Citation2020). It is not surprising that implementing a pedestrianization plan in congested streets can significantly reduce the risk of accidents and provide people with a safer and more comfortable mobility experience (Soni and Soni Citation2016; Noland Citation2021). Moreover, this policy supports the presence of vulnerable social groups, such as children, the elderly, and disabled people (Yassin Citation2019). Our SAF finding aligns with a study by Younes, Noland, and Andrews (Citation2023) in New Jersey (United States), which revealed that the provision of pedestrian facilities is associated with a decreased risk of fatal crashes, even in states with high non-motorist fatality rates. Our result also brings attention to the perceived lack of accessibility of urban emergency vehicles in all residential areas, which could potentially affect overall safety.

On the dimension of SEC, security is closely tied to various urban factors, including continuous social activities, the quality of night lighting (Soni and Soni Citation2016) and police monitoring. Increasing street lighting can reduce public anxiety about vulnerability to criminal activity (Peña-García, Hurtado, and Aguilar-Luzón Citation2015). Peña-García, Hurtado, and Aguilar-Luzón (Citation2015) further explain that when night lighting is adequate and uniform in urban spaces, individuals feel safer and more at ease. Although pedestrian policies are expected to enhance sustainability (Guillen-Royo Citation2022), their location and stakeholder considerations require further attention. Adopting an active transportation plan in an inappropriate location may pose security risks rather than fostering sustainability. For example, in Chile and South America more generally, the lack of urban access in low-income areas led to security crises for pedestrians, particularly concerning sexual harassment (Herrmann-Lunecke Citation2020). Likewise, even with initial success, some American cities experienced failure two decades after implementation, mainly due to a lack of night lights and security issues in pedestrian areas, and the affected communities reverted to a vehicular setting in the 1990s (Parajuli and Pojani Citation2018). In contrast, more effective implementation of pedestrian zones in European cities has demonstrated success in terms of inclusive access, security, and social vitality (Koster, Pasidis, and van Ommeren Citation2019; Parajuli and Pojani Citation2018; Michalina et al. 2021). Although ChAPS was appropriately located in the historical and commercial heart of the city, this placement did not significantly strengthen the public sense of security. In the pre-project survey, most security concerns in this area were related to old, non-compliant teahouses and itinerant vendors (MATFA Citation2017), which were subsequently removed. Despite this intervention, ChAPS likely achieved a sustainable social realm of safety and security. However, ongoing efforts to provide security for all sensitive groups of society remain crucial.

The SDGs emphasize the importance of justice for all segments of society, not just during the implementation of a project but also afterward. Accordingly, we recommend promoting social equity by providing facilities for disadvantaged groups. These investments may include additional urban furniture, tactile paving, stair-free paths, convenient access to public transportation, toilets for the disabled, and shelters for rainy days. Furthermore, we propose organizing national and religious festivals, street-theater performances, street-music events, cultural competitions, and other sociocultural programs within the pedestrian area to encourage community engagement and vibrancy. Moreover, fostering trust among users of the space prior to, during, and after project implementation is essential to meet the objectives of local communities and encourage their active participation. The AT plan should focus on a strategically suitable location and be aimed to foster sustainable transportation and address the air-pollution challenges faced by ME urban centers. This AT zone should also incorporate adequate night illumination to guarantee the safety and security of pedestrians and cyclists. Finally, to develop access to pedestrian zones, project planners should ensure an efficient public transportation network with frequent and reliable service and offer affordable fares for all socioeconomic groups.

Conclusion

In summary, the case of pedestrianization described in this article influenced social interaction, sense of belonging, feelings of safety and security, and sense of responsibility in ChAPS compared to the prior period. First, we found that the pedestrianization policy enhanced social interaction among city dwellers, particularly in regions with public transportation access to the ChAPS area. Second, the project improved the sense of belonging to ChAPS for residents who live far from this historical area. Third, the feelings of safety for city inhabitants and visitors noticeably increased, while their sense of security saw a negligible improvement. In contrast, the sense of responsibility among city residents surprisingly diminished after the project, specifically in regions located some distance from the pedestrian area. More precisely, we found that all urban areas of Isfahan contribute to social sustainability and are affected by it, with areas close to ChAPS being more influential than the less proximate ones.

Accordingly, since pedestrianization has not yet been thoroughly explored in historical ME communities, the present investigation could potentially pave the way for further studies about social sustainability throughout the region. We suggest that urban planners provide all city inhabitants with sufficient facilities such as inclusive transportation services, accessible facilities for the elderly, and disability-inclusive infrastructures. It is also important to arrange smart advertising for social programs, encourage more people to participate in the diverse social programs, and build the trust of city dwellers to attract their participation. As we had significant limitations in accessing governmental data, further research is suggested to deepen our knowledge of the accomplishments of a wider range of sub-indicators of the SDGs. Due to the unique cultural and geographical context of the ME, we strongly recommend that policymakers prioritize social sustainability in urban initiatives and involve local communities to ensure equity, social justice, and project survival.

Ethical statement

The research involved human participants and was approved by Human Research Ethics committee of the Isfahan University of Technology (approval IUT Code of Ethics) prior to data collection. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Municipality of Isfahan and Dr. Sayyed Mahdi Abtahi for supporting the research. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Maurie Cohen for his generous assistance and meticulous editing of the article’s content.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We divided district 2 into two parts with district 11 located between them. Based on the authors’ knowledge of the area, we assumed that this area had a meaningful concentration of elderly people whose limited mobility and insufficient accessibility to public transportation could justify why the residents of this area had less social interaction in ChAPS.

References

- Askarizad, R., and H. Safari. 2020. “The Influence of Social Interactions on the Behavioral Patterns of the People in Urban Spaces (Case Study: The Pedestrian Zone of Rasht Municipality Square, Iran).” Cities 101: 1. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102687.

- Bagheri, B., and R. Shaykh-Baygloo. 2021. “Spatial Analysis of Urban Smart Growth and Its Effects on Housing Price: The Case of Isfahan, Iran.” Sustainable Cities and Society 68: 102769. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2021.102769.

- Bayomi, N., and J. Fernandez. 2019. “Towards Sustainable Energy Trends in the Middle East: A Study of Four Major Emitters.” Energies 12 (9): 1615. doi:10.3390/en12091615.

- Blasi, S., A. Ganzaroli, and I. Noni. 2022. “Smartening Sustainable Development in Cities: Strengthening the Theoretical Linkage between Smart Cities and SDGs.” Sustainable Cities and Society 80: 103793. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2022.103793.

- Blečić, I., T. Congiu, G. Fancello, and G. Trunfio. 2020. “Planning and Design Support Tools for Walkability: A Guide for Urban Analysts.” Sustainability 12 (11): 4405. doi:10.3390/su12114405.

- Boessen, A., A. Boessen, J. Hipp, C. Butts, N. Nagle, and E. Smith. 2018. “The Built Environment, Spatial Scale, and Social Networks: Do Land Uses Matter for Personal Network Structure?” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 45 (3): 400–17. doi:10.1177/2399808317690158.

- Chatman, D., A. Broaddus, and A. Spevack. 2019. “Are Movers Irrational? On Travel Patterns, Housing Characteristics, Social Interactions, and Happiness Before and After a Move.” Travel Behaviour and Society 16: 262–271. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2018.11.004.

- Chen, M., W. Liu, and X. Tao. 2013. “Evolution and Assessment on China’s Urbanization 1960–2010: Under-Urbanization or Over-Urbanization?” Habitat International 38: 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.09.007.

- Cohen, M. 2021. Sustainability. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Danaei, G., F. Farzadfar, R. Kelishadi, A. Rashidian, O. Rouhani, S. Ahmadnia, A. Ahmadvand, M. Arabi, A. Ardalan, and M. Arhami. 2019. “Iran in Transition.” Lancet 393 (10184): 1984–2005. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33197-0.

- Dičiūnaitė-Rauktienė, R., V. Gurskienė, M. Burinskienė, and V. Maliene. 2018. “The Usage and Perception of Pedestrian Zones in Lithuanian Cities: Multiple Criteria and Comparative Analysis.” Sustainability 10 (3): 818. doi:10.3390/su10030818.

- Diener, E., M. Seligman, H. Choi, and S. Oishi. 2018. “Happiest People Revisited.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (2): 176–184. doi:10.1177/1745691617697077.

- Eizenberg, E., and Y. Jabareen. 2017. “Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability 9 (1): 68. doi:10.3390/su9010068.

- El-Ghonaimy, I., and M. Al-Haddad. 2019. “Towards Reviving the Missing Noble Characteristics of Traditional Habitual Social Life: Al-Farej in Kingdom of Bahrain.” Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 3 (2): 35–46. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2018.4699.

- Guillen-Royo, M. 2022. “Flying Less, Mobility Practices, and Well-Being: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic in Norway.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 18 (1): 278–291. doi:10.1080/15487733.2022.2043682.

- Hahm, Y., H. Yoon, and Y. Choi. 2019. “The Effect of Built Environments on the Walking and Shopping Behaviors of Pedestrians: A Study with GPS Experiment in Sinchon Retail District in Seoul, South Korea.” Cities 89: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.020.

- Held, C., and J. Cummings. 2018. Middle East Patterns: Places, Peoples, and Politics. New York: Routledge.

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M. G., R. Mora, and L. Sagaris. 2020. “Persistence of walking in Chile: lessons for urban sustainability.” Transport reviews 40 (2): 135–159. doi:10.1080/01441647.2020.1712494

- Hu, L., X. Wu, J. Huang, Y. Peng, and W. Liu. 2020. “Investigation of Clusters and Injuries in Pedestrian Crashes Using GIS in Changsha, China.” Safety Science 127: 104710. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104710.

- Isfahan Municipality. 2020. The portals for 13th and 15th urban areas. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://mun13.isfahan.ir/node/5875, and https://mun15.isfahan.ir/node/5877

- Jamei, E., K. Ahmadi, H. Chau, M. Seyedmahmoudian, B. Horan, and A. Stojcevski. 2021. “Urban Design and Walkability: Lessons Learnt from Iranian Traditional Cities.” Sustainability 13 (10): 5731. doi:10.3390/su13105731.

- Khan, A., S. Bibi, A. Lorenzo, J. Lyu, and Z. Babar. 2020. “Tourism and Development in Developing Economies: A Policy Implication Perspective.” Sustainability 12 (4): 1618. doi:10.3390/su12041618.

- Koohsari, M., A. Yasunaga, K. Oka, T. Nakaya, Y. Nagai, and G. McCormack. 2023. “Place Attachment and Walking Behaviour: Mediation by Perceived Neighbourhood Walkability.” Landscape and Urban Planning 235: 104767. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104767.

- Koster, H., I. Pasidis, and J. van Ommeren. 2019. “Shopping Externalities and Retail Concentration: Evidence from Dutch Shopping Streets.” Journal of Urban Economics 114: 103194. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2019.103194.

- Liu, Y., M. Dijst, S. Geertman, and C. Cui. 2017. “Social Sustainability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability 9 (4): 658. doi:10.3390/su9040658.

- Mansourianfar, M., and H. Haghshenas. 2018. “Micro-Scale Sustainability Assessment of Infrastructure Projects on Urban Transportation Systems: Case Study of Azadi District, Isfahan, Iran.” Cities 72: 149–159. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.012.

- MATFA. 2017. Sociocultural Impact Studies of Charbagh Abbasi Report. Isfahan: Municipality of Isfahan (in Persian).

- Mehr News Agency. 2019. “Pedestrian construction of Chaharbagh from idea to implementation: a plan without citizens’ participation”, text in Farsi, code: 4805935, http://mehrnews.com/xQRFk, accessed on 04/03/2024

- Michalina, D., P. Mederly, H. Diefenbacher, and B. Held. 2021. “Sustainable Urban Development: A Review of Urban Sustainability Indicator Frameworks.” Sustainability 13 (16): 9348. doi:10.3390/su13169348.

- Mouratidis, K. 2021. “Urban Planning and Quality of Life: A Review of Pathways Linking the Built Environment to Subjective Well-Being.” Cities 115: 103229. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103229.

- Mueller, N., D. Rojas-Rueda, T. Cole-Hunter, A. Nazelle, E. Dons, R. Gerike, T. Goetschi, L. Panis, S. Kahlmeier, and M. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2015. “Health Impact Assessment of Active Transportation: A Systematic Review.” Preventive Medicine 76: 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.010.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M. 2020. “Urban and Transport Planning Pathways to Carbon Neutral, Liveable and Healthy Cities: A Review of the Current Evidence.” Environment International 140: 105661. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105661.

- Noland, R. 2021. “Pedestrian Safety Versus Traffic Flow: Finding the Balance.” In Transport and Safety, edited by G. Tiwari and D. Mohan, 165–187. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-1115-5_9.

- Nursyamsiah, R., and R. Setiawan. 2023. “Does Place Attachment Act as a Mediating Variable that Affects Revisit Intention toward a Revitalized Park?” Alexandria Engineering Journal 64: 999–1013. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.08.030.

- Ortega, E., B. Martín, Á. Isidro, and R. Cuevas-Wizner. 2020. “Street Walking Quality of the ‘Centro’ District, Madrid.” Journal of Maps 16 (1): 184–194. doi:10.1080/17445647.2020.1829114.

- Özdemir, D., and İ. Selçuk. 2017. “From Pedestrianisation to Commercial Gentrification: The Case of Kadıköy in Istanbul.” Cities 65: 10–23. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.02.008.

- Parajuli, A., and D. Pojani. 2018. “Barriers to the Pedestrianization of City Centres: Perspectives from the Global North and the Global South.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (1): 142–160. doi:10.1080/13574809.2017.1369875.

- Peña-García, A., A. Hurtado, and M. Aguilar-Luzón. 2015. “Impact of Public Lighting on Pedestrians’ Perception of Safety and Well-Being.” Safety Science 78: 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2015.04.009.

- Rivai, F., M. Rohman, and B. Sumantri. 2023. “Assessment of Social Sustainability Performance for Residential Building.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 19 (1): 2153575. doi:10.1080/15487733.2022.2153575.

- Rogers, S., K. Gardner, and C. Carlson. 2013. “Social Capital and Walkability as Social Aspects of Sustainability.” Sustainability 5 (8): 3473–3483. doi:10.3390/su5083473.

- Salimi, M., and S. Al-Ghamdi. 2020. “Climate Change Impacts on Critical Urban Infrastructure and Urban Resiliency Strategies for the Middle East.” Sustainable Cities and Society 54: 101948. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101948.

- Shafik, Z., and M. El-Husseiny. 2019. “Re-Visiting the Park: Reviving the ‘Cultural Park for Children’ in Sayyeda Zeinab in the Shadows of Social Sustainability.” Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 3 (2): 84–94. doi:10.25034/ijcua.2018.4704.

- Shahmoradi, S., S. Abtahi, and P. Guimarães. 2023. “Pedestrian Street and Its Effect on Economic Sustainability of a Historical Middle Eastern City: The Case of Chaharbagh Abbasi in Isfahan, Iran.” Geography and Sustainability 4 (3): 188–199. doi:10.1016/j.geosus.2023.03.006.

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. 2020. “A Multifaceted Study of Place Attachment and Its Influences on Civic Involvement and Place Loyalty in Baharestan New Town, Iran.” Cities 96: 102473. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102473.

- Smart, M., and N. Klein. 2020. “Disentangling the Role of Cars and Transit in Employment and Labor Earnings.” Transportation 47 (3): 1275–1309. doi:10.1007/s11116-018-9959-3.

- Soni, N., and N. Soni. 2016. “Benefits of Pedestrianization and Warrants to Pedestrianize an Area.” Land Use Policy 57: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.009.

- United Nations. 2015. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Report, USA: http://sdgs.un.org, accessed on 04/03/2024

- Ujang, N. 2012. “Place Attachment and Continuity of Urban Place Identity.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 49: 156–167. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.07.014.

- Uršič, M., and B. Križnik. 2012. “Comparing Urban Renewal in Barcelona and Seoul – Urban Management in Conditions of Competition Among Global Cities.” Asia Europe Journal 10 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1007/s10308-012-0319-1.

- Volker, J., and S. Handy. 2021. “Economic Impacts on Local Businesses of Investments in Bicycle and Pedestrian Infrastructure: A Review of the Evidence.” Transport Reviews 41 (4): 401–431. doi:10.1080/01441647.2021.1912849.

- Wang, H., Y. Zhao, X. Gao, and B. Gao. 2021. “Collaborative Decision-Making for Urban Regeneration: A Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis.” Land Use Policy 107: 105479. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105479.

- Xie, F., G. Liu, and T. Zhuang. 2021. “A Comprehensive Review of Urban Regeneration Governance for Developing Appropriate Governance Arrangements.” Land 10 (5): 545. doi:10.3390/land10050545.

- Yasin, H., F. Tariq, and F. Najeeb. 2021. “Perception Based Evaluation of Pedestrianization at Liberty Market Lahore.” Global Regional Review VI (IV): 1–15. doi:10.31703/grr.2021(VI-IV).01.

- Yassin, H. 2019. “Livable City: An Approach to Pedestrianization through Tactical Urbanism.” Alexandria Engineering Journal 58 (1): 251–259. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2019.02.005.

- Yıldız, S., S. Kıvrak, A. Gültekin, and G. Arslan. 2020. “Built Environment Design – Social Sustainability Relation in Urban Renewal.” Sustainable Cities and Society 60: 102173. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102173.

- Yoshimura, Y., Y. Kumakoshi, Y. Fan, S. Milardo, H. Koizumi, P. Santi, J. Arias, S. Zheng, and C. Ratti. 2022. “Street Pedestrianization in Urban Districts: Economic Impacts in Spanish Cities.” Cities 120: 103468. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103468.

- Younes, H., R. Noland, and C. Andrews. 2023. “Gender Split and Safety Behavior of Cyclists and E-Scooter Users in Asbury Park, NJ.” Case Studies on Transport Policy 14: 101073. doi:10.1016/j.cstp.2023.101073.

- Zhuang, T., Q. Qian, H. Visscher, M. Elsinga, and W. Wu. 2019. “The Role of Stakeholders and Their Participation Network in Decision-Making of Urban Renewal in China: The Case of Chongqing.” Cities 92: 47–58. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.03.014.