Abstract

Over the past decade, the concept of circular economy (CE) has gained political traction as a potential solution to economy-environment tradeoffs. However, critical social scientists have raised concerns that CE may not address the root causes or consequences of environmental degradation, thus remaining ineffective. Concurring with this critique, this article highlights three constituent elements of the linear economy that remain unaddressed in CE frameworks: environmental, labor, and gender inequalities. Building upon scholarship from environmental justice, environmental labor studies, and feminist ecological economics, we elaborate a conceptual framework to interrogate the existing literature. Our analysis shows that current CE models 1) are mainly concerned with return on capital investment and sustained growth of gross domestic product (GDP) rather than with redressing the North/South inequalities embedded in the linear economy model; 2) present a limited perspective on labor, with a primary focus on the number of jobs to be created, rather than their quality, or workers’ leadership; and 3) overlook gender inequalities and the sexual division of labor, thus reproducing the devaluation of care that lays at the roots of socioecological crises. We conclude by suggesting avenues for elaborating a “just circular economy” framework.

Introduction

The concept of circular economy (CE) has gained momentum at a political and industrial level as a potentially transformative new organization of production that combines economic growth and environmental sustainability (Becque, Roy, and Hamza-Goodacre Citation2016; Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017; Ghisellini et al. Citation2016). CE is an economic system designed to minimize waste and optimize resource use by keeping materials in use for as long as possible, reducing the amount of waste produced, and preserving the value of products and materials (Calisto Friant, Vermeulen, and Salomone Citation2020a). The CE model aims to create a closed-loop system in which materials are reused, repaired, and recycled rather than being thrown away after their initial use (Genovese, Figueroa, and Koh Citation2017). This approach has gained significant attention in recent years due to its potential to address environmental and economic challenges. Nevertheless, it has also faced criticisms from various perspectives (Pansera, Genovese, and Ripa Citation2021) including the lack of consideration for overconsumption (Calisto Friant, Vermeulen, and Salomone Citation2020b), energy and material limits (Giampietro and Funtowicz Citation2020), scaling problems (Bimpizas-Pinis et al. Citation2021; Genovese and Pansera Citation2020), and the required investments (Bauwens, Hekkert, and Kirchherr Citation2020; Giampietro and Funtowicz Citation2020). Although there is still a very low share of social and political science studies in CE research compared to the fields of engineering, industrial organization, or supply-chain management (Llorente-González and Vence Citation2020), a small but consistent body of literature has emerged recently that focuses on the social aspects. Some scholars have problematized the lack of consideration for social equity issues (Schröder et al. Citation2019; Schröder, Anggraeni, and Weber Citation2019; Ziegler et al. Citation2023), highlighting the importance of social inclusion and justice (Mies and Gold Citation2021; Bradley and Persson Citation2022; Jaeger-Erben et al. Citation2021). Others have focused on the importance of disentangling international relations, geopolitics, and global justice in framing circularity (Barrie and Schröder Citation2022). Finally, more recently a number of scholars have highlighted the ethical foundations of CE models (Inigo and Blok Citation2019; Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017) and the impact on employment (Burger et al. Citation2019; James Citation2022).

In short, critical social scientists have argued that mainstream policy frameworks, such as the European Union’s (EU) CE action plan (European Commission Citation2015), lack fundamental reflections about who wins and who loses if an ecological circular transition is going to be implemented. The result is an apolitical version of circularity, that is too focused on how production is carried out, with virtually no emphasis on who produces for what reason. This article attempts to contribute to filling this gap by proposing a conceptual framework for a just transition to CE. The aim is to further the debate about how to repoliticize the CE by focusing on three dimensions of justice which are typically unaddressed by mainstream CE frameworks: environmental, labor, and gender justice. To achieve this goal, the article is structured as follows. First, we offer a brief analysis of current CE models, showing how they overlook justice issues. Second, we elaborate an analytical framework that we call “just circular economy” (JCE), based on a selection of key concepts from environmental social science literatures, and particularly environmental justice, environmental labor studies, and feminist ecological economics. Illustrating the concepts of environmental, labor, and gender justice, our JCE framework is intended to show how they are connected to each other and the CE. Our overall research question then becomes: How can critical CE research help reorient CE practices and policies toward equality and justice? Finally, we interrogate the current academic CE literature to understand to what extent it engages with notions of environmental, labor, and gender injustices. In particular, we focus on three sub-questions:

How does CE research engage with environmental inequalities? And how could CE models be reshaped toward reparation of ecological and climate debt?

Are workers’ subjectivity and agency considered in CE research? How could CE models be recentered around workers’ perspectives?

How does CE research frame questions of gender and value? And how could CE models be reframed through a proper valuation of reproductive and care work?

Finally, we discuss the results of the review and compare them with our framework for a JCE.

Toward just circular economy (JCE): a conceptual framework

Repoliticizing the CE starts from asking what it looks like from the perspective of social groups at the bottom of power hierarchies and typically excluded from decision-making processes. In this article, we focus on three broad areas of social inequality that we consider as particularly relevant to give voice to the potential losers of top-down CE transitions: environmental, labor, and gender inequalities. To assess how these are related to current CE implementations, in this section we elaborate a preliminary conceptual framework based on a selection of key concepts from three bodies of environmental social science research: environmental justice, environmental labor studies, and feminist ecological economics.

Environmental justice

The concept of environmental inequalities signals the uneven distribution of the environmental and social costs associated with the life cycle of commodities, from extractive processes to transport, manufacturing, distribution, and waste disposal (Boyce, Zwickl, and Ash Citation2016; Pellow Citation2000; Szasz and Meuser Citation1997). Studies in environmental justice (EJ) have demonstrated that industrial toxicity/hazards, resource exhaustion, and contested facilities tend to concentrate in specific areas (referred it as “sacrifice zones”) typically inhabited by marginalized populations such as Black, Indigenous, peasants, or working-class communities (Zografos and Robbins Citation2020). As part of the broader domain of EJ, the study of “ecological distribution conflicts” (Martinez-Alier Citation2002) has focused on the analysis of such unequal distribution of costs, including its structural causes and consequences, from local to global scales. Building upon ecological economics, environmental history, political ecology, and world-system theory, this scholarship highlights how environmental inequalities have emerged from the unprecedented increase in global social metabolism (energy and material use) throughout the industrial era, and especially during the so-called Great Acceleration period, generally construed as 1950 to the present (Steffen et al. Citation2015).

On the global scale, EJ research shows how the current planetary crisis has resulted from “ecologically unequal exchange” (Martinez-Alier Citation2021). The latter signals the unequal distribution of costs and benefits of the increase in social metabolism between the global North and South. According to this scholarship, the economic growth of the global North has been possible through the historical and present plundering of resources and the discharge of waste and other ecological damage onto colonized territories, generating “ecological debt.” Additionally, carbon-dioxide (CO2) emissions produced by the global North disproportionately affect the environmental stability of the global South – a process which generates “climate debt” (Pickering and Barry Citation2012). As claimed by decolonial social movements since the early 1990s (Warlenius et al. Citation2015), this historical trend continues today as a cumulative effect of unequal/colonial relations on the global scale. Ecological and climate debts can be assessed using material flow analysis, where the monetary evaluation of indicators on pollution, depletion, and degradation, together with ecological footprints (the environmental space occupied and used to maintain a particular production) can be calculated to determine local and global impact of trade, historically dominated by the global North (Pigrau 2014). More recently, decolonial movements have been demanding the reparation of ecological and climate debt from the global North, aiming to remediate the legacy of colonialism and unequal ecological exchange (Papadopoulos, de la Bellacasa, and Tacchetti Citation2023).

One of the most significant EJ issues potentially associated with the CE is the export of waste to developing countries. The CE initiatives that rely on this type of waste disposal shift the cost of CE on to third parties, harming local communities and damaging their environments (Perkins et al. Citation2014; Shittu, Williams, and Shaw Citation2021). From this perspective, the CE configures yet another source of ecological debt, for example through “double standard” practices which tend to dump hazardous recycling and remanufacturing activities in poor countries, taking advantage of cost differentials and the availability of cheap labor and resources. However, while the impact of global supply chains on the environment is well documented, there is a scarcity of research about the impact of a transition to circularity on North-South relations (Genovese, Figueroa, and Koh Citation2017). This is a significant research gap, which perpetuates the misleading idea that the global North has appropriate solutions to environmental problems, which the global South is incapable of implementing – while hiding the inverse relationship between long-term responsibilities and impact of the ecological and climate crises.

Environmental labor studies

Questioning the putative opposition between work and environment is foundational to an emerging body of scholarship called environmental labor studies (ELS). In its founding text, Räthzel and Uzzell (Citation2012) indicate its twofold objective. First, theoretical explorations delve into the inherent intertwining of production and the environment, revealing their inseparable connection, while also highlighting the peril posed by capitalist social constructs and their institutional manifestations. Secondly, through empirical analysis, ELS shows that there exists a critical evaluation of the environmental stances adopted by workers’ organizations on a global scale. In recent years, a notable development in ELS has been the elaboration of a heuristic framework that identifies in the organization of labor along global value chains the core issue for the analysis of the internally differentiated relationship between society and nature (Barth and Littig Citation2021; Räthzel, Stevis, and Uzzell (Citation2021). What kind of work is valued? How are tasks pertaining to it distributed? How much are they remunerated? These are far from irrelevant questions for understanding the root causes and possible remedies of ecological crises. Thus, ELS does not necessarily employ a normative approach. Rather, the unitary trait is the analytical reconstruction of the dilemmas of trade union politics with respect to environmental issues, especially when such politics assumes that employment and health are not constitutively in opposition to each other (Barca and Leonardi Citation2018; Barca 2012).

The concept of “just transition” (JT) is a central concern for ELS, which frames it as a historical turning point in labor politics, aimed at overcoming the tension between labor and environmental policies. Since the early 1990s, trade unions have discursively mobilized the JT to claim that the ecological transition could not happen if its manifold costs had to be largely paid by workers (Mazzochi Citation1993; Kohler Citation2010). In its current official definition (ILO Citation2015), JT is intended to guarantee appropriate working conditions and decent green jobs for all, including for workers in sectors that should be abandoned (for example, fossil fuel-intensive value chains). Since 2015, this version of JT has become a central tenet of transnational climate governance; quite notably, it has been included in the Paris Agreement resulting from the 21st Conference of the Parties (to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP 21) and is one of the watchwords of many international organizations (most recently, the final text of COP28 – so-called Global Stocktake – mentions JT ten timesFootnote1). In line with the market-centered and corporate-led approach which characterizes the COP system, this definition of JT assigns a passive role to workers and their organizations and is limited to preventing an excessively unfair distribution of costs and benefits of the post-carbon transition.

The contemporary general increase in labor disputes on environmental issues, along with some cases of strategic alliance between industrial workers and climate-justice movements (e.g., at the ex-GKN factory in Florence (Gabbriellini and Imperatore Citation2023; Feltrin and Leonardi Citation2023)) – suggest that a shift in JT politics might be underway.1 As some scholars have suggested (Velicu and Barca Citation2020; Leonardi Citation2019; Feltrin and Leonardi Citation2023), more than a defensive posture (reluctance to assume the full cost of productive eco-transformations), the JT might be signifying a path-breaking strategy for eco-syndicalism in the 21st century. This shift is propelled by the recognition that the market-based green economy strategy – embedded in United Nations-led climate governance and hence in the Paris Agreement – while safeguarding profits, has failed to both safeguard workers’ interests and to bring environmental benefits.

From this perspective, workers and their organizations must be regarded not as mere receivers of compensatory policies but as central actors of a truly just post-carbon transition. Accordingly, thinking the CE through a radical JT lens means paying attention to workers’ agency and to labor’s potential leadership of an ecological transition from below.

Feminist ecological economics

Income from paid labor is not the only material resource for well-being and dignity, insofar as unpaid labor such as taking care of children or parents, cooking, or sorting waste are all activities that ensure the reproduction of society. The sexual division of labor, however, has led to most of the unpaid work being done by women and paid work by men, which has resulted in a precariousness of women in the labor market and their subordination in family and society (Perez Orozco Citation2019; Carrasco Citation2014a). Most gender-equality policies aim to transfer women to the market economy by removing existing barriers to their inclusion in the labor market, for example by providing formal education and job opportunities (Picchio Citation2021). While this antidiscrimination approach is ethically and politically necessary, it is insufficient to bring gender justice. On one hand, simply adding waged work to women’s daily lives does not in itself eliminate the unpaid tasks that gender norms assign them in households and communities; it is amply demonstrated how this often generates a double burden of work for women. On the other hand, gender-parity approaches reinforce existing valuation mechanisms, which exclude most of social reproduction work from the sphere of what counts as relevant to “the economy” (Perez Orozco Citation2014; Carrasco Citation2014b).

Feminist economists have long demonstrated that growth of gross domestic product (GDP) is (literally) based on the devaluation of all the work that is necessary to reproduce not only societies but also their environments. The connection between the devaluation of both women’s work and the environment was first made by Australian political economist and politician Marilyn Waring (Citation1999), who argued that GDP is not an adequate measure of wealth because it discounts both the unpaid work of care and subsistence production and ecosystem services; in fact, GDP accounting severely underestimates human and nonhuman reproduction and care work (or the “production of life”), and/or considers them as passive sectors (economic costs). At the same time, GDP accounting includes human and environmental depletion/degradation as value-producing. A striking contemporary example is given by carbon trading and other financial mechanisms that turn the climate and biodiversity crises into financial opportunities. In short, Waring (1999) argued, the paradox of GDP is that it values work correlated with human and environmental costs while devaluing work correlated with human and environmental services. This approach showed how the unlimited growth of the valued economy requires an increase of unvalued work to support it, leading to crisis in both social and environmental reproduction (Barca Citation2019, Citation2020). The link between these two forms of reproduction provides the starting point for feminist ecological economics (FEE), a body of scholarship that sees ecological crisis as resulting from the devaluation of reproductive work (Perkins et al. Citation2005; Mellor Citation1997; Perkins Citation1997; Nelson Citation1997; O’Hara Citation1995; Agarwal Citation1992).

Structural gender inequalities are reflected by current CE practices. A recent report by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO Citation2022) found that there is an over-representation of women in low-value-added, informal, and end-of-pipe activities of the CE, including recycling, reuse, and waste management. By contrast, there is an under-representation of women in higher value-added circular activities such as industrial eco-design and the development of circular products. The over-representation of women in low value-added CE is correlated with the fact that many circular activities are carried out by unpaid workers, both in the domestic and in the public sphere, for instance by volunteers in recycling centers. Despite the central importance of these tasks in an economy focused on reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling (Ravenswood Citation2022; Barca Citation2023), there is a lack of dedicated studies in the CE literature. This constitutes a significant research gap, which – following the FEE approach – can be seen as a consequence of patriarchal valuation mechanisms, disregarding reproductive and care work as compared to commodity production.

Toward a just circular economy

Based on the three bodies of critical social science literature highlighted above, the premises of our investigation can be summarized as such: (1) the unprecedented growth of global GDP since the 1950s is unequivocally correlated with the growth in industrial social metabolism, whose social and environmental cost have been mostly shouldered – but also actively opposed – by subaltern social subjects, and particularly by women in all of them; (2) in order to overcome the opposition between production and ecology, a market-led green economy is not enough (actually, it has proved counterproductive). Against this background, any transition toward a just CE should seriously consider and engage with workers’ and trade unions not only as vulnerable actors to be protected but rather as proactive subjects to be involved in the socioeconomic eco-transformation through participation and eco-design “from below”; (3) the current planetary crisis is a direct consequence of an economic model which overvalues destructive and degrading practices while devaluing care-centered and regenerative ones. This critical social science perspective highlights the need for elaborating what we call a Just CE framework, i.e., one capable of redressing the environmental, labor and gender inequalities that constitute the linear economy.

Our approach to justice follows Velicu and Barca (Citation2020) in rejecting post-political notions of justice in distributional and procedural terms and characterize it as a “method of equality” among all the subjects of ecological transitions. Understanding the latter as a way out of unequal relations, as a preliminary condition for envisaging a way out of fossil fuels or waste (see also (Armiero Citation2021)). Velicu and Barca (Citation2020) propose that a JT to sustainability can only be a radically democratic one, where the socially disadvantaged and marginalized subjects are not simply at the receiving end of compensation or recognition policies, but are those who define the terms of the problem in the first place. Our approach here does not focus on the process of transition to a CE, which would require a separate discussion. Rather, we address the preliminary problem of how and by whom unsustainability is experienced and defined, and how this shapes CE models. In other terms, we are addressing the problem of inequalities.

We understand inequalities as structural characteristics of the linear economy, which are indispensable to its functioning. Without shifting environmental and social costs onto Black, Indigenous, peasant, working-class, and female populations, and onto the global South more generally, the linear economy could not exist. In other words, if waste (in the broadest sense) was dumped into the backyard and the bodies of the rich (most of them being white men in power), and if toxic jobs, as well as unpaid reproductive and care work were dumped upon the same men, circularity and sustainability would now prevail. It is as simple as that: inequalities produce unsustainability. By ignoring or reproducing inequalities, CE models can at best achieve weak and circumscribed sustainability, while de facto shifting environmental costs on to third parties. Consequently, we argue, making the CE just, in the sense of prioritizing the redressing of inequalities, is not only normative – driven by a moral imperative toward environmental, labor and gender justice, but inherently functional to achieving strong sustainability. As anticipated in the introduction, our overall research question thus becomes: How can critical CE research help reorient CE policies toward equality?

Research methods

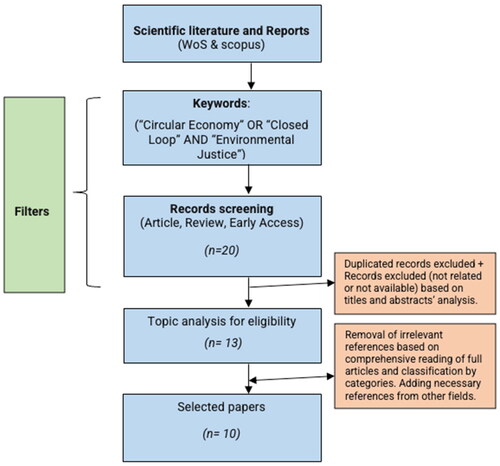

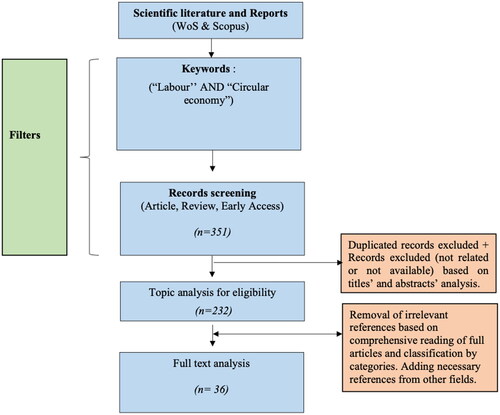

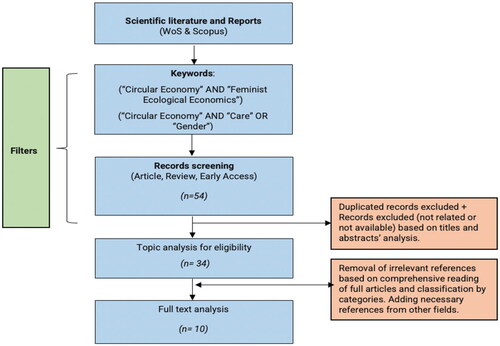

To address the research questions outlined in the previous section, we conducted a systematic literature review combined with a critical content analysis of selected articles. The intent was to provide an overview of the state of the art about how CE literature frames the three types of (in)justice dimensions outlined above. The systematic review was carried out using keyword searchers in the Web of Science and Scopus database (see ). Since we were interested in how the notion of CE is discursively used in combination with environmental, labor, and gender justice, we explicitly excluded related concepts such as waste management, recycling and the like. The only exception was the keyword “closed-loop” that is conventionally considered a synonym of CE. The review was complemented with reports from international organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and trade unions retrieved from Google Scholar databases using specific keywords for environmental, labor, and gender.

Global environmental justice in CE transition

This search was oriented by the question: How do CE research, policy, and practices engage with environmental inequalities? And how could EJ research help reshape CE models toward reparation of ecological and climate debt? Using the Web of Science and Scopus databases, we conducted a keyword search with the query “Circular Economy” OR “closed loop” AND “Environmental Justice.” The search returned only 13 articles from which we selected 10 that were directly connected with EJ. Although EJ was mentioned, the 3 excluded articles did not actually engage with the concepts and literature. A detailed analysis of the 10 articles is reported in the results section.

Labor in CE

This search was oriented by the questions: Are workers’ subjectivity and agency considered in CE models? What would CE look like if shaped around workers’ needs and perspectives? We conducted keyword research in Web of Science and Scopus using “Labour OR Labor’’ AND “Circular Economy.” We have limited ourselves to the words in the title of our report, as the literature on the subject is already overwhelming. When we added “work” AND “circular economy” to the Web of Science and Scopus, we found over 10,000 items. After eliminating duplicate references, our set contained 232 articles. shows an overview of the item-selection process. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the bibliography, we then selected 36 articles (n = 36) relevant to our research questions. The full list is available in Appendix 2.

Gender in CE transition

This search was oriented by the question: How does CE frame questions of gender and value? And how could the FEE approach help reshape the CE toward a proper valuation of reproductive and care work? We initiated our investigation by employing a search strategy encompassing the keywords “Circular Economy” and “gender” within titles, keywords, and abstracts. This initial query yielded a pool of 41 articles, from which we meticulously curated 21 based on their relevance, specifically focusing on those that delved into gender as a socioeconomic aspect or indicator within the context of CE. Notably, only 7 of the selected articles explicitly embraced a feminist perspective. Subsequently, we refined our search using the keywords “Circular Economy” and “care” within titles, keywords, or abstracts, resulting in the identification of 13 articles. Within this subset, only 5 articles offered a nuanced analysis of care from a gender perspective. Remarkably, two of these articles overlapped with the previously selected pool, bringing the final count to 10 articles of particular interest. For a comprehensive overview of these selected articles, please refer to Appendix 2. A detailed analysis of the 10 articles is reported in the results section.

Results

The global environmental justice dimension

We extracted only 10 articles from the review that clearly engage with the concept of EJ (see Appendix 1). Overall, the authors criticized the lack of meaningful engagement in CE studies with EJ concepts. We can summarize this critique as follows: (1) Most CE works adopt a reduced understanding of circularity in terms of waste management and recycling and (2) They tend to ignore complex global dynamics in which power asymmetries create injustices through dispossession, contamination and exploitation, especially in the global South.

In a published note entitled “Scientists’ Warning Against the Society of Waste,” Marín-Beltrán et al. (Citation2022) make a call to move beyond the mere focus on waste management in CE and to imagine an economy that prioritizes well-being, social equity, and ecological sustainability. Malinauskaite and Jouhara (Citation2019) and Chen (Citation2021) also criticize the narrow focus of EU policy and argue that CE policies should be clearly readdressed to contribute to global EJ. According to Gregson et al. (Citation2015), current EU policy uses CE as a moral economy distinguishing right circularity practices (high-quality recycling conducted within the EU) from wrong practices conducted outside of the borders of the EU that are labeled as illegal and insecure. The CE is presented as an ideal of ecomodernism where there are right and wrong ways of keeping materials circulating. According to these authors, this vision overlooks the fact that the “right” modes of CE in the EU are often only possible through the outsourcing of “dirty” practices to non-European countries. The same dynamics are shown in the works of Mason-Renton and Luginaah (Citation2018) and Ashwood and MacTavish (Citation2016) who documented how the burden of waste management in many CE initiatives is unequally distributed between North and South and between rural and urban spaces.

Similarly, Wuyts and Marin (Citation2022), applying an intersectional environmentalist lens, argue that CE initiatives in Flanders are based on a “nobodisation” of knowledge that removes people and territories from the scene. In the same vein, Niskanen, McLaren, and Anshelm (Citation2021) argue that the CE often fails to acknowledge the social struggles and history of extractivism. Through interviews with a group of repairers, including practitioners and experts, the authors highlight the political dimension of repair and its role within a larger system. The repairers questioned the depoliticization of repair and its potential to exacerbate existing inequalities. In other words, the article suggests that the CE may overlook the social and political complexities of repair and fail to address the systemic issues that perpetuate environmental and social injustices.

In his recent work, Martinez-Alier (Citation2021) draws upon environmental conflict cases documented in the EJAtlasFootnote2 to demonstrate the inherent limitations of achieving a circular industrial metabolism. Despite attempts to make the linear economy more circular, such efforts often lead to environmental injustices due to the continued growth of the economy and its reliance on an ever-expanding material basis. The author contends that the prevailing discourse and practices around the CE are not at odds with the pursuit of economic growth, and warns that even with increased circularity, the expansion of extraction and waste-disposal frontiers will inevitably result in more environmental injustice. Pansera, Genovese, and Ripa’s (Citation2021) article addresses the potential consequences of a transition to closed-loop production and consumption systems that do not account for justice and power relations. They argue that a technocratic approach to the CE can overlook environmental and social injustices. To counter this, the authors suggest that responsible innovation offers a more comprehensive approach to CE, incorporating public engagement, anticipation, and reflexivity, which have been neglected in mainstream CE practices. These dimensions are essential for a JT to a CE, as they address issues such as democracy, planning, participation, gender, and global justice.

Finally, Mah (Citation2021) critically examines the CE and its growing popularity as a sustainable business concept that emphasizes a circular, zero-waste economy. Using a political economy and Gramscian approach, the article suggests that the CE offers a grand but vague solution to the linear “take-make-waste” model of industrial growth without actually giving up on growth. The author highlights the challenges of securing public legitimacy and protecting and extending the markets of plastics, which remain major contributors to environmental injustice and climate change despite commitments to the CE by the petrochemical industry. In summary, Mah’s analysis underscores the need for a deeper examination of the political and economic forces at play in CE discourses and practices and the importance of addressing systemic issues to achieve genuine sustainability.

The labor dimension

In our comprehensive review, the 36 selected articles collectively underscore a pervasive critique concerning the insufficient incorporation of JT concepts within CE studies. This appraisal can be succinctly summarized as follows:

Limited conceptualization of labor: The majority of the reviewed works critique CE for adopting a narrow perspective on labor, predominantly focusing on the quantitative aspect of job creation without delving into the qualitative dimensions.

Neglect of social dynamics: A notable deficiency identified in these studies is the disregard for intricate social dynamics. Specifically, there is a tendency to overlook the power asymmetries existing between labor and capital, resulting in injustices manifested through exploitation. This exploitation is particularly pronounced within a context of racialized and gendered labor forces.

This critical evaluation emphasizes the need for a more nuanced and holistic approach within CE studies, one that incorporates the broader implications of JT principles and acknowledges the intricate interplay between labor, power dynamics, and social justice concerns. Virtually all articles adopt a quantitative approach, whose primary aim is assessing CE potentials for job creation on the basis of a rather heterogeneous set of circular activities, and measuring the effects of capital composition on employment, and the global restructuring of labor markets among different economic sectors (Repp et al.

Citation2021). This phenomenon is elucidated in the comprehensive review undertaken by Mies and Gold (Citation2021), revealing that a significant proportion – specifically two-thirds – of the articles dedicated to the “social dimension” of CE predominantly concentrate on quantitatively measuring the emergence of new jobs. Strikingly, job creation often stands as the exclusive social indicator employed in assessments within the realm of CE. Most of these studies suggest that a CE will produce an overall net-jobs increase (Larsson and Lindfred Citation2019; Mitchell and James Citation2015; Sulich and Sołoducho-Pelc Citation2022; Wiebe et al. Citation2019). In the grey literature these forecasts of the overall increase in employment are generally even more positive than in the academic literature on the subject (see Stavropoulos and Burger Citation2020). These claims, however, are contested by scholars who point at methodological issues (Laubinger Citation2019) and, most importantly, by authors who denounce the lack of focus on the impact of a CE transition on global supply chains.

Following the publication of an International Labour Organization report (ILO Citation2008b), the CE literature on labor has increasingly adopted the concept of “green jobs” (Sulich and Sołoducho-Pelc Citation2022), which aims to juxtapose employment opportunities with climate-change mitigation. This approach, however, rarely challenges the imperative of endless economic growth, nor does it question the corporate organization of labor or workplace hierarchies. Similarly, in the CE literature, the focus on labor is usually limited to issues such as workers’ health and safety, skills development, and general working conditions (Mies and Gold Citation2021).

Some attention, however, is also being paid to the quality of CE jobs. Of our selection of 36 references, 16 articles or reports (n = 16) also deal with issues of quality in terms of opportunities for work that is productive and delivers a fair income; provides security in the workplace and social protection for workers and their families; offers better prospects for personal development and encourages social dialogue and integration; gives people the freedom to express their concerns, to organize, and to participate in decisions that affect their lives; and guarantees equal opportunities and equal treatment for all (ILO Citation2008b). More recently, the concept of “decent work seems to partially include attention to the distribution of decision-making power within the company and to workers’ agency (ILO Citation2015). For instance, in one of the rare articles directly tackling this issue, Buch et al. (Citation2021) defend the centrality of cooperative forms of organization in the transition to the CE. Nevertheless, the agency of workers, is seldom considered in the selected literature. Except for a very few studies (n = 3/36), the articles we analyzed barely mention the agency or power of workers’ decisions, the effects of the transition on reproductive and unpaid labor, or the place of non-citizen immigrant workers in the CE. This confirms Mies and Gold’s preliminary observation that the CE shows “a noticeable distinction between actively or passively involved actor groups,” with workers usually depicted as passive in contrast to organizations being perceived as active and decisive, and a general focus “on organizations and society as taking care of employees’ well-being’’ (Mies and Gold Citation2021, 12).

The gender dimension

We organized our analysis of the 10 selected articles by distinguishing between high-value added and low-value added (or unvalued) practices. As regards the first, the gender dimension in CE often emerged in relation with repairing activities. In a study of repair communities in Norway and the Netherlands, for example, van der Velden (Citation2021) claims that “repair has gender,” meaning that repair work follows traditional gender roles, with men occupying the majority of paid jobs in the repair sector in the EU (together with construction and mining). As Pla-Julián and Guevara (Citation2019) argue, since neither consumers’ attitudes and preferences, nor organizations, innovation, institutions or budgets are gender neutral, the implementation of a gender-just CE implies profound changes with long-ranging impacts at multiple levels. These authors emphasize how proper consideration of gender issues is still missing from research on CE and, more broadly, on sustainability. Similar claims are made by Vijeyarasa and Liu (2022) who documented that CE discourse has become central in “sustainable fashion,” a sector dominated by a female labor force with most of them in the global South. The authors argue that one of the key barriers to fulfilling the rights of women workers in the fashion industry is that sustainability is not necessarily understood as requiring a gender perspective. They also note that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) tend to treat women as a monolithic category. This is more evident considering the relevance of women’s multiple identities as workers in the garment sector, where the initiatives implemented in response to the SDGs, such as policies that provide for equal pay or prohibit discrimination among employees, do not actually affect the majority of women workers in this sector, who are informal or contract workers and therefore unable to benefit from these policies. Similar arguments can be found in other sectors such as the agri-food industry (Coghlan, Proulx, and Salazar Citation2022; El Wali, Golroudbary, and Kraslawski Citation2021).

Other authors develop a critique of corporate CE as fundamentally unjust, implicitly reflecting a more skeptical approach to the possibilities of implementing a just CE in the capitalist system. Dauvergne and LeBaron (2013), for example, claim that corporate-recycling plans are shifting capital’s contradictions with nature onto labor and gender and that, rather than maintaining a focus on value-creation opportunities through better management of material resources, the CE literature should take seriously the debate on the need to overcome the pursuit of growth. The authors argue that the corporatization of recycling is devaluing marginalized populations within the global economy. They show how in the recycling of electronic waste in the global South, the majority of the workforce comprises women and children, while in the United States it is formed by men of color from poor backgrounds. More specifically, the article exposes that, “Using archaic technology to extract value from what others have thrown away, this work exposes a highly racialized and gendered labor force to extreme levels of toxicity, contributing, particularly in the global South, to high rates of injury, illness and death” (Dauvergne and LeBaron Citation2013, 411).

As regards gender and care in the unvalued CE, we found several authors who focus on non-corporate – for example community-oriented CE practices – specifically, repair, reuse, and composting – developing what we call a value-transformative approach to CE. Community-oriented CEs are described as the most fertile terrain for value transformation; however, they are also shaped by the currently dominant gender/value constructs. van der Velden (Citation2021), for example, focuses on community repair, in which locally-organized networks match volunteer repairers with people in need of repair. They find that repair is considered a value-based activity reflecting a variety of economic and non-economic values. McQueen et al. (Citation2022) show that women are more engaged in self-repairing their clothes than men. Berry (Citation2022) investigates the role of community-based reuse organizations, mostly formed by volunteer women. They propose framing CE as an effort at closing the loop between production and reproduction by expanding our understanding of CE toward including care work, specifically that which takes place outside the household. Morrow and Davies (Citation2022) investigate community composting in New York City and highlight the importance of the social, material, and affective relations related to care work that is done in these contexts. They criticize mainstream CE approaches for overlooking aspects such as the “labor, health, equity, care, education, and participation” involved in composting programs. The authors argue that care work is often unpaid, mostly done by women volunteers, and tends to be underacknowledged and devalued compared to other kinds of labor, because of its gendered dimension. They call for a need to shift burdens onto producers through extended producer-responsibility programs that include unpaid labor. The authors conclude that the current linear production-consumption-disposal system fails to recognize the value created by care work. The article concludes by noting that community-based reuse and repair initiatives can positively influence gender roles in tech work and that a radical rethinking of economy and waste is required to look beyond efficiency and privilege the affective, material, and ethical doing of care.

Overall, our review points to two key insights. First, the CE’s potential to promote gender justice has not yet been fully assessed (only 10 articles in our review clearly address CE and gender; see Appendix 2). Second, achieving this goal would require a transformation of the present valuation mechanisms within CE. This entails redefining the value produced in CE to include the unpaid reproductive and care work that is often excluded from mainstream value theories and practices. Such a transformation would bring about a more equitable distribution of value and recognition for the traditionally devalued care work performed mostly by women. Therefore, to fully leverage the potential of CE to promote gender justice, a comprehensive restructuring of the current valuation mechanisms is crucial.

Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis shows that, although all three dimensions of inequality are structurally embedded by CE practices, problems of justice are generally ignored or underestimated by CE models. At the same time, the literature discussed here offers important insights into possible ways of redressing this important lacuna. The EJ perspective highlights that the transition to CE is likely to generate both benefits and costs associated with changes in material and energy throughput. These impacts will be unevenly distributed across intersecting dimensions of power, perpetuating existing inequalities. Without addressing the potential unfair distribution of these impacts and without considering the historical injustices caused by the linear model, the implementation of CE policies and programs may lead to a simple shift of social and environmental costs, with the emergence of new ecological distribution conflicts (Buckingham et al. Citation2005). Furthermore, many circular activities, which are essential for achieving sustainability but are not typically recognized as such by CE theorists or practitioners, are excluded from mainstream CE policies and discourse. These activities include informal, nonprofit, or non-value-oriented practices like informal repair, waste-picking, unpaid reproductive work in households and communities, and peasant farming. Empirical studies in the field of EJ have shown the significant role played by these actors in waste reduction and circularity. Their exclusion from CE models reflects and perpetuates a top-down colonial knowledge paradigm that disregards sustainable practices which are not value-oriented.

Our review problematizes the general focus on new employment opportunities in the CE, showing how this does not guarantee job quality. Most importantly, while ELS has been describing workers as proactive agents of change, with the right to decide not only the conditions of production but also what should and should not be produced based on its social usefulness, most labor-related CE literature still assumes workers as merely passive recipients of top-down decisions regarding CE design, policies, and implementation. A number of factors can explain the prevalence of this approach.

The large prevalence of literature reviews over field surveys – which would be more conducive to investigate workers’ agency and subjectivity.

Circular economy models tend to be top-down and to take a global rather than a local approach, which prevents us from considering the situated viewpoints of workers in different contexts.

The CE literature seems to largely ignore theoretical traditions (e.g., materialist and Marxist sociology of work) that have favored the consideration of workers’ points of view and agency.

A greater emphasis on workers’ agency in CE initiatives would enrich the concept of decent work and overcome the limitations of a narrow focus on green jobs and economic growth. A fair CE model, we argue, should involve workers’ subjectivity in two ways: (1) enabling them to take pride in and receive recognition for their work, and (2) empowering them to initiate the transition to a CE. Workers can drive transition policies at various levels. At the company level, workers should have a role in decision-making processes, whether it involves cooperative enterprises shaping strategies or dedicated (and executive) committees focusing on occupational health and safety and production processes. When collective decision-making by workers integrates environmental concerns, it achieves a double objective: to protect working conditions and to regulate relations with the environment (Akbulut and Adaman Citation2020). The challenge for a fair and sustainable decision-making system is therefore both to give workers a central place in a company’s orientations and to integrate environmental standards for a just CE. At the national level, workers’ proposals for social and environmental initiatives should find expression through social dialogue facilitated by their trade unions. Overall, the convergence of demands for a JT among public institutions, civil society, private companies, and trade unions can meaningfully influence political power to implement real transformative policies.

As regards the gender dimension, our review shows that CE often reflects the same devaluation mechanisms that characterize the linear economy. Women tend to occupy the lower value-added positions and reproductive and care work continues to be excluded from definitions of what is valued by the CE, with important consequences upon people’s lives and well-being, as well as on the environment. Our analysis suggests that achieving gender justice in the CE requires more than a mere “gender equality” approach. This is because, while gender equality would lead toward including (more) women in the formal economy, this would not, per se, alter the (de)valuation mechanisms that produce gender inequality in the first place. Further, and equally relevant to a CE perspective, the same devaluation mechanisms that exclude women from the formal economy are also a root cause of environmental degradation. What is devalued, in GDP-growth oriented economies, is reproductive work, most notably the work of producing and caring for people and the environment. In short, the gender-equality approach per se is not conducive to a just CE. Feminist political economists have highlighted that the inclusion of women in the labor market fails to address sexual and racial divisions of labor. This often results in women bearing a double burden of work, including paid employment and unpaid domestic/care/provisioning and subsistence work. Alternatively, devalued caring responsibilities are shifted onto others, typically racialized and/or migrant women. In essence, ensuring equal access to the CE for women is a fundamental anti-discriminatory approach, but it alone does not address gender inequality. Moreover, since reproductive work is primarily focused on sustaining and regenerating human and nonhuman well-being and requires continuous effort, if it is not adequately valued within the CE, it will be shifted elsewhere. In other words, true circularity will not be achieved. Consequently, an environmentally-just CE needs to be based on a redefinition of value that includes circular work in all its forms. This also applies to reproductive work – which is largely circular.

summarizes the results of our analysis in relation with the sub-research questions and the conceptual framework presented in the earlier sections of this article. In the table we also highlight the cross-references between the three dimensions of justice that we identified and propose a potential research agenda for a Just CE. We conclude that, while mainstream business models of the CE focus on resource efficiency and waste valorization, a JCE model should be based on three features. First, it should focus on repairing ecological and climate debts accrued by the global North toward the global South, while recognizing and supporting the already-existing non-value-oriented circularities. Second, it should reframe the role of labor by empowering workers themselves as CE leaders. Finally, a JCE should find ways to properly value and center reproductive and care work, while displacing the centrality of commodity production.

Table 1. Main findings and a potential research agenda.

In closing, we note that we are aware that this study has two limitations that warrant consideration. First, our examination did not extend to policy documents, particularly those associated with European Horizon programs and grey literature. This omission is noteworthy, as an exploration of such policy frameworks could provide valuable insights into the evolution of CE policies, particularly in relation to justice dimensions. Moreover, a deeper analysis of the grey literature would add more granularity to what is really happening on the ground where corporate and public institutions, but also civil society actors, are trying to translate the abstract notion of circularity into viable actions. Second, it is important to acknowledge that our focus was exclusively on studies that explicitly self-identified as being within the purview of the CE. While this decision allowed for a targeted investigation, it may have excluded relevant perspectives or approaches that align with CE principles but do not explicitly label themselves as such. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the scope of this article and potential implications for broader contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 1 The “ex-GKN” factory in Florence, Italy, is often referred to as the Officine Zero or Officine Gulliver. It became a symbol of workers’ resistance and the cooperative movement. The story began in 2012 when the GKN plant was shut down, leaving hundreds of workers unemployed. In response, a group of these workers decided to occupy the factory, protesting against job losses and corporate decisions. They transformed the abandoned factory into a worker-run cooperative, demonstrating an alternative model of production based on self-management and solidarity.

2 The EJAtlas, short for Environmental Justice Atlas, is an online platform that maps and documents environmental conflicts around the world. It provides information about various environmental justice issues, including land-grabbing, pollution, deforestation, water conflicts, and more. The EJAtlas aims to raise awareness about these conflicts, to highlight the voices of affected communities, and to support efforts toward environmental justice and sustainability. The platform collects data from various sources, including academic research, grassroots organizations, and media reports, to create interactive maps and detailed case studies. Users can explore the map to learn about specific environmental conflicts in different regions, access relevant documents and resources, and connect with organizations and activists working on related issues. The EJAtlas is available at: https://ejatlas.org.

References

- Agarwal, B. 1992. “ The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India." Feminist Economics 18 (1): 119–158.

- Akbulut, B., and F. Adaman. 2020. “The Ecological Economics of Economic Democracy.” Ecological Economics 176: 1. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106750.

- Albaladejo, M., V. Arribas, and P. Mirazo. 2022. Why Adopting a Gender-Inclusive Approach towards Circular Economy Matters. Geneva: UNIDO. https://iap.unido.org/articles/why-adopting-gender-inclusive-approach-towards-circular-economy-matters.

- Armiero, M. 2021. Wasteocene: Stories from the Global Dump. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ashwood, L., and K. MacTavish. 2016. “Tyranny of the Majority and Rural Environmental Injustice.” Journal of Rural Studies 47: 271–16. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.017.

- Barca, S. 2019. “An Alternative Worth Fighting For: Degrowth and the Liberation of Work.” In Towards a Political Economy of Degrowth, edited by S. Barca, E. Chertkovskaya, and A. Paulsson, 175–192. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Barca, S. 2020. Forces of Reproduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barca, S. 2023. “Dimensions of Repair Work.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13 (2): 255–258. doi:10.1177/20438206221144827.

- Barca, S., and E. Leonardi. 2018. “Working-Class Ecology and Union Politics: A Conceptual Topology.” Globalizations 15 (4): 487–503. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1454672.

- Barrie, J., and P. Schröder. 2022. “Circular Economy and International Trade: A Systematic Literature Review.” Circular Economy and Sustainability 2 (2): 447–471. doi:10.1007/s43615-021-00126-w.

- Barth, T., and B. Littig. 2021. “Labour and Societal Relationships with Nature.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Labour Studies, edited by N. Räthzel, D. Stevis, and D. Uzzell, 769–792. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bauwens, T., M. Hekkert, and J. Kirchherr. 2020. “Circular Futures: What Will They Look like?” Ecological Economics 175: 106703. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106703.

- Becque, R., N. Roy, and D. Hamza-Goodacre. 2016. The Political Economy of the Circular Economy: Lessons to Date and Questions for Research. San Francisco: ClimateWorks Foundation. https://www.climateworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/CE-political-economy.pdf.

- Berry, B. 2022. “Glut: Affective Labor and the Burden of Abundance in Secondhand Economies.” Anthropology of Work Review 43 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1111/awr.12233.

- Bimpizas-Pinis, M., E. Bozhinovska, A. Genovese, B. Lowe, M. Pansera, J. Pinyol-Alberich, and M. Ramezankhani. 2021. “Is Efficiency Enough for Circular Economy?” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 167: 105399–105399. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105399.

- Boyce, J., K. Zwickl, and M. Ash. 2016. “Measuring Environmental Inequality.” Ecological Economics 124: 114–123. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.01.014.

- Bradley, K., and O. Persson. 2022. “Community Repair in the Circular Economy – Fixing More than Stuff.” Local Environment 27 (10–11): 1321–1337. doi:10.1080/13549839.2022.2041580.

- Buch, R., A. Marseille, M. Williams, R. Aggarwal, and A. Sharma. 2021. “From Waste Pickers to Producers: An Inclusive Circular Economy Solution through Development of Cooperatives in Waste Management.” Sustainability 13 (16): 8925. doi:10.3390/su13168925.

- Buckingham, S., D. Reeves, and A. Batchelor. 2005. “Wasting Women: The Environmental Justice of Including Women in Municipal Waste Management.” Local Environment 10 (4): 427–444. doi:10.1080/13549830500160974.

- Burger, M., S. Stavropoulos, S. Ramkumar, J. Dufourmont, and F. van Oort. 2019. “The Heterogeneous Skill-Base of Circular Economy Employment.” Research Policy 48 (1): 248–261. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.015.

- Calisto Friant, M., W. Vermeulen, and R. Salomone. 2020a. “A Typology of Circular Economy Discourses: Navigating the Diverse Visions of a Contested Paradigm.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 161: 104917. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104917.

- Calisto Friant, M., W. Vermeulen, and R. Salomone. 2020b. “Analysing European Union Circular Economy Policies: Words versus Actions.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 337–353. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2020.11.001.

- Carrasco, C. 2014a. “Introducción (Introduction).” In Con Voz Propia: La Economía Feminista Como Apuesta Teórica y Política (With Your Own Voice: Feminist Economics as a Theoretical and Political Commitment), edited by C. Carrasco, 15–24. Madrid: La Oveja Roja.

- Carrasco, C. 2014b. “La falsa neutralidad de las estadísticas: hacia un sistema de indicadores no androcéntrico (The False Neutrality of Statistics: Toward a Non-Androcentric System of Indicators).” In Con voz propia: La economía feminista como apuesta teórica y política (With Your Own Voice: Feminist Economics as a Theoretical and Political Commitment), edited by C. Carrasco, 99–120. Madrid: La Oveja Roja.

- Chen, C.-W. 2021. “Clarifying Rebound Effects of the Circular Economy in the Context of Sustainable Cities.” Sustainable Cities and Society 66: 102622. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102622.

- Coghlan, C., P. Proulx, and K. Salazar. 2022. “A Food-Circular Economy-Women Nexus: Lessons from Guelph-Wellington.” Sustainability 14 (1): 192. doi:10.3390/su14010192.

- Dauvergne, P., and G. LeBaron. 2013. “The Social Cost of Environmental Solutions.” New Political Economy 18 (3): 410–430. doi:10.1080/13563467.2012.740818.

- El Wali, M., S. Golroudbary, and A. Kraslawski. 2021. “Circular Economy for Phosphorus Supply Chain and Its Impact on Social Sustainable Development Goals.” Science of the Total Environment 777: 146060. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146060.

- European Commission. 2015. Implementation of the First Circular Economy Action Plan. Brussels: European Commission. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/first-circular-economy-action-plan_en.

- Feltrin, L., and E. Leonardi. 2023. “Working-Class Environmentalism and Climate Justice: Strategic Converging for an Ecological Transition from Below.” R:I – Relaçoes Internacionais, 49–61.

- Gabbriellini, P., and F. Imperatore. 2023. “An Eco-Revolution of the Working Class? What We Can Learn from the Former GKN Factory in Italy.” Berliner Gazette. https://berlinergazette.de/an-eco-revolution-of-the-working-class-what-we-can-learn-from-the-former-gkn-factory

- Genovese, A., A. Figueroa, and L. Koh. 2017. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management and the Transition towards a Circular Economy: Evidence and Some Applications.” Omega 66: 344–357. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2015.05.015.

- Genovese, A., and M. Pansera. 2020. “The Circular Economy at a Crossroads: Technocratic Eco-Modernism or Convivial Technology for Social Revolution?” Capitalism Nature Socialism 32 (2): 95–113. doi:10.1080/10455752.2020.1763414.

- Ghisellini, P., C. Cialani, and S. Ulgiati. 2016. “A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems.” Journal of Cleaner Production 114: 11–32. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007.

- Giampietro, M., and S. Funtowicz. 2020. “From Elite Folk Science to the Policy Legend of the Circular Economy.” Environmental Science & Policy 109: 64–72. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.012.

- Gregson, N., M. Crang, S. Fuller, and H. Holmes. 2015. “Interrogating the Circular Economy: The Moral Economy of Resource Recovery in the EU.” Economy and Society 44 (2): 218–243. doi:10.1080/03085147.2015.1013353.

- Inigo, E., and V. Blok. 2019. “Strengthening the Socio-Ethical Foundations of the Circular Economy: Lessons from Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 233: 280–291. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.053.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2008a. Toolkit for Mainstreaming Employment and Decent Work – Country Level Application. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-exrel/documents/publication/wcms_172612.pdf.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2008b. Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World. Geneva: ILO. http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/WCMS_158727/lang–en/index.htm.

- ILO. 2015. Guidelines for a Just Transition towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf.

- Jaeger-Erben, M., C. Jensen, F. Hofmann, and J. Zwiers. 2021. “There is No Sustainable Circular Economy without a Circular Society.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 168: 105476. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105476.

- James, P. 2022. “Re-Embedding the Circular Economy in Circles of Social Life: Beyond the Self-Repairing (and Still-Rapacious) Economy.” Local Environment 27 (10–11): 1208–1224. doi:10.1080/13549839.2022.2040469.

- Kirchherr, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Kohler, B. 2010. “Decent Jobs or Protection of the Environment?” International Union Rights 17 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1353/iur.2010.0048.

- Larsson, A., and L. Lindfred. 2019. “Digitalization, Circular Economy and the Future of Labor: How Circular Economy and Digital Transformation Can Affect Labor.” In The Digital Transformation of Labor: Automation, the Gig Economy, and Welfare, edited by A. Larsson and R. Teigland, 174–184. London: Routledge.

- Laubinger, F. 2019. “OECD – WCEFOnline Side Event: Labour Implications of the Circular Economy Transition.” Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/environment/waste/OECDWCEFOnlineSideEventLabourimplicationsofthecirculareconomytransition.htm

- Leonardi, E. 2019. “Bringing Class Analysis Back In.” Ecological Economics 156: 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.09.012.

- Leonardi, E. 2023. “La giusta transizione tra questione sociale e questione ambientale (The Just Transition between Social and Environmental Issues).” Giornale DI Diritto Del Lavoro E DI Relazioni Industriali 177: 99–124. doi:10.3280/GDL2023-177007.

- Llorente-González, L., and X. Vence. 2020. “How Labour-Intensive is the Circular Economy? A Policy-Orientated Structural Analysis of the Repair, Reuse and Recycling Activities in the European Union.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 162: 105033. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105033.

- Mah, A. 2021. “Future-Proofing Capitalism: The Paradox of the Circular Economy for Plastics.” Global Environmental Politics 21 (2): 121–142. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00594.

- Malinauskaite, J., and H. Jouhara. 2019. “The Trilemma of Waste-to-Energy: A Multi-Purpose Solution.” Energy Policy 129: 636–645. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.02.029.

- Marín-Beltrán, I., F. Demaria, C. Ofelio, L. Serra, A. Turiel, W. Ripple, S. Mukul, and M. Costa. 2022. “Scientists’ Warning against the Society of Waste.” Science of the Total Environment 811: 151359. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151359.

- Martinez-Alier, J. 2002. The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Martinez-Alier, J. 2021. “Mapping Ecological Distribution Conflicts: The EJAtlas.” The Extractive Industries and Society 8 (4): 100883. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2021.02.003.

- Martinez-Alier, J., L. Temper, D. Del Bene, and A. Scheidel. 2016. “Is There a Global Environmental Justice Movement?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (3): 731–755. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198.

- Mason-Renton, S., and I. Luginaah. 2018. “Conceptualizing Waste as a Resource: Urban Biosolids Processing in the Rural Landscape.” Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes 62 (2): 266–281. doi:10.1111/cag.12454.

- Mazzochi, T. 1993. “A Superfund for Workers.” Earth Island Journal 9 (1): 40–41.

- McQueen, R., L. McNeill, Q. Huang, and B. Potdar. 2022. “Unpicking the Gender Gap: Examining Socio-Demographic Factors and Repair Resources in Clothing Repair Practice.” Recycling 7 (4): 53. doi:10.3390/recycling7040053.

- Mellor, M. 1997. “Women, Nature and the Social Construction of ‘Economic Man.’” Ecological Economics 20 (2): 129–140. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(95)00100-X.

- Mies, A., and S. Gold. 2021. “Mapping the Social Dimension of the Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 321: 128960. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128960.

- Mitchell, P., and K. James. 2015. Economic Growth Potential of More Circular Economies. Banbury: Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP).

- Morrow, O., and A. Davies. 2022. “Creating Careful Circularities: Community Composting in New York City.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (2): 529–546. doi:10.1111/tran.12523.

- Murray, A., K. Skene, and K. Haynes. 2017. “The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context.” Journal of Business Ethics 140 (3): 369–380. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2.

- Nelson, J. 1997. “Feminism, Ecology, and the Philosophy of Economics.” Ecological Economics 20 (2): 155–162. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00025-0.

- Niskanen, J., D. McLaren, and J. Anshelm. 2021. “Repair for a Broken Economy: Lessons for Circular Economy from an International Interview Study of Repairers.” Sustainability 13 (4): 2316. doi:10.3390/su13042316.

- O’Hara, S. 1995. “Sustainability: Social and Ecological Dimensions.” Review of Social Economy 53 (4): 529–551. doi:10.1080/00346769500000017.

- Pansera, M., A. Genovese, and M. Ripa. 2021. “Politicising Circular Economy: What Can We Learn from Responsible Innovation?” Journal of Responsible Innovation 8 (3): 471–477. doi:10.1080/23299460.2021.1923315.

- Papadopoulos, D., M. de la Bellacasa, and M. Tacchetti, eds. 2023. Ecological Reparation: Repair, Remediation and Resurgence in Social and Environmental Conflict. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Pellow, D. 2000. “Environmental Inequality Formation: Toward a Theory of Environmental Injustice.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (4): 581–601. doi:10.1177/0002764200043004004.

- Perez Orozco, A. 2014. “Del trabajo doméstico al trabajo de cuidados (From Domestic Work to Care Work).” In Con voz propia: La economía feminista como apuesta teórica y política (With Your Own Voice: Feminist Economics as a Theoretical and Political Commitment ), edited by C. Carrasco, 49–74. Madrid: La Oveja Roja.

- Perez Orozco, A. 2019. Subversión feminista de la economía: Aportes Para un debate sobre el conflicto capital-vida (Feminist Subversion of Economics: Contributions to a Debate on the Capital-Life Conflict). Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños.

- Perkins, D., M. Brune Drisse, T. Nxele, and P. Sly. 2014. “E-Waste: A Global Hazard.” Annals of Global Health 80 (4): 286–295. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2014.10.001.

- Perkins, E. 1997. “Introduction: Women, Ecology, and Economics: New Models and Theories.” Ecological Economics 20 (2): 105–106. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00459-4.

- Perkins, E., E. Kuiper, R. Quiroga-Martínez, T. Turner, L. Brownhill, M. Mellor, Z. Todorova, M. Jochimsen, and M. McMahon. 2005. “Explorations: Feminist Ecological Economics.” Feminist Economics 11 (3): 107–150. doi:10.1080/13545700500301494.

- Picchio, A. 2021. “Condiciones de vida: perspectivas, análisis económico y políticas públicas (Living Conditions: Perspectives, Economic Analysis and Public Policies).” Revista De Economía Crítica 1 (7): 27–54.

- Pickering, J., and, C. Barry. 2012. “On the Concept of Climate Debt: Its Moral and Political Value.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 15 (5): 667–685. 10.1080/13698230.2012.727311.

- Pigrau, A. 2014. “The Texaco-Chevron case in Ecuador: Law and justice in the age of globalization.” Revista catalana de dret ambiental 5(1):1–43.

- Pla-Julián, I., and S. Guevara. 2019. “Is Circular Economy the Key to Transitioning towards Sustainable Development? Challenges from the Perspective of Care Ethics.” Futures 105: 67–77. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2018.09.001.

- Räthzel, N., and, D. Uzzell. 2012. “Mending the Breach between Labour and Nature: Environmental Engagements of Trade Unions and the North-South Divide.” Interface: A Journal For and About Social Movements 4 (2): 81–100.

- Räthzel, N., D. Stevis, and D. Uzzell, eds. 2021. The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Labour Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ravenswood, K. 2022. “Greening Work-Life Balance: Connecting Work, Caring and the Environment.” Industrial Relations Journal 53 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1111/irj.12351.

- Repp, L., M. Hekkert, and J. Kirchherr. 2021. “Circular Economy-Induced Global Employment Shifts in Apparel Value Chains: Job Reduction in Apparel Production Activities, Job Growth in Reuse and Recycling Activities.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 171: 105621. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105621.

- Schröder, P., M. Anantharaman, K. Anggraeni, and T. Foxon. 2019. “Conclusion: Pathways to an Inclusive Circular Economy.” In The Circular Economy and the Global South, edited by P. Schröder, M. Anantharaman, K. Anggraeni, and T. Foxon, 203–211. London: Routledge.

- Schröder, P., K. Anggraeni, and U. Weber. 2019. “The Relevance of Circular Economy Practices to the Sustainable Development Goals.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 23 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1111/jiec.12732.

- Shittu, O., I. Williams, and P. Shaw. 2021. “Global E-Waste Management: Can WEEE Make a Difference? A Review of E-Waste Trends, Legislation, Contemporary Issues and Future Challenges.” Waste Management 120: 549–563. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2020.10.016.

- Stavropoulos, S., and M. Burger. 2020. “Modelling Strategy and Net Employment Effects of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency: A Meta-Regression.” Energy Policy 136: 111047. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111047.

- Steffen, W., W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, and C. Ludwig. 2015. “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration.” The Anthropocene Review 2 (1): 81–98. doi:10.1177/2053019614564785.

- Sulich, A., and L. Sołoducho-Pelc. 2022. “The Circular Economy and the Green Jobs Creation.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 29 (10): 14231–14247. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16562-y.

- Szasz, A., and M. Meuser. 1997. “Environmental Inequalities: Literature Review and Proposals for New Directions in Research and Theory.” Current Sociology 45 (3): 99–120. doi:10.1177/001139297045003006.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). 2022. Circular Economy. Geneva: UNIDO. https://www.unido.org/unido-circular-economy.

- van der Velden, M. 2021. “‘Fixing the World One Thing at a Time’: Community Repair and a Sustainable Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 304: 127151. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127151.

- Velicu, I., and S. Barca. 2020. “The Just Transition and Its Work of Inequality.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 263–273. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1814585.

- Waring, M. 1999. Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women Are Worth. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Warlenius, R., G. Pierce, and V. Ramasar. 2015. “Reversing the Arrow of Arrears: The Concept of “Ecological Debt” and Its Value for Environmental Justice.” Global Environmental Change 30: 21–30. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.014.

- Wiebe, K., M. Harsdorff, G. Montt, M. Simas, and R. Wood. 2019. “Global Circular Economy Scenario in a Multiregional Input-Output Framework.” Environmental Science & Technology 53 (11): 6362–6373. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b01208.

- Wuyts, W., and J. Marin. 2022. “‘Nobody’ Matters in Circular Landscapes.” Local Environment 27 (10–11): 1254–1271. doi:10.1080/13549839.2022.2040465.

- Ziegler, R., T. Bauwens, M. Roy, S. Teasdale, A. Fourier, and E. Raufflet. 2023. “Embedding Circularity: Theorizing the Social Economy, Its Potential, and Its Challenges.” Ecological Economics 214: 107970. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107970.

- Zografos, C., and P. Robbins. 2020. “Green Sacrifice Zones, or Why a Green New Deal Cannot Ignore the Cost Shifts of Just Transitions.” One Earth 3 (5): 543–546. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.10.012.