ABSTRACT

Recent research has shown that adopting a cooperative approach in agricultural production and exchange can be an effective and sustainable method in agri-food supply chains (SCs). However, existing studies have primarily focused on treating institutions as organizational components of agricultural production and exchange, with little attention given to the power dynamics inherent in agri-food collaboration. To bridge this gap, this study has integrated perspectives from new institutional economics (NIE) and political ecology. In particular, this study has drawn on the concept of “a bundle of powers” introduced by Ribot and Peluso (2003) in the “theory of access” framework. In this paper, I investigate the power dimensions of collaboration within agri-food SCs, emphasizing the importance of understanding the political relationships of agri-food production. My findings demonstrate that, while the networking between farmers and the edamame SC tends to be more socially sustainable, interactions with the rice SC have occasionally led to adverse outcomes such as indebtedness and impeded rice farming. These findings underscore the significance of taking into account the political and power dimensions of the agri-SC to comprehend and tackle the challenges encountered by farmers in their cultivation decisions.

Introduction

Agri-food research has previously stressed the crucial role of collaboration in organizing agri-food supply chains (SCs) (Bandara et al. Citation2017; Gramzow et al. Citation2018; Yang et al. Citation2022). This scholarship has emphasized agricultural cooperative operations and SC integration, generally viewing buyer – supplier collaboration in SCs as a means of creating value. Consequently, SCs involve joint planning and investment in relation-specific assets to foster sustainable agri-food production and exchange (L. Wang et al. Citation2021; Yang et al. Citation2022). However, these collaborative relationships do not assure balanced gains for all participants (Devin and Richards Citation2018; Yang et al. Citation2021). While SC-related studies have paved the way for a deeper understanding of the organizational aspects of agri-food supply, this line of scholarship has tended to perceive institutions as an organizational element of agricultural production and exchange. Consequently, this body of work has paid less attention to how collaborative agri-food production represents an unfolding of power dynamics, which may result in less sustainable economic and ecological development. In practice, agricultural organizations such as firms or farmer cooperatives rely on their interactions with formal institutions to operate effectively (Ricks and Doner Citation2021). Moreover, it is important to emphasize the concept of “a bundle of powers” in the theory of access, introduced by Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003). This concept refers to the “capability” of actors to derive advantages from controlling or maintaining access to resources within chains or other forms of commodity exchange. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the power dynamics within agri-food SC collaboration. Specifically, the study analyzes the connections between organizations and institutional political power and how these powered networks in northern Thailand have shaped farmers’ access to resources and influenced their farming decisions.

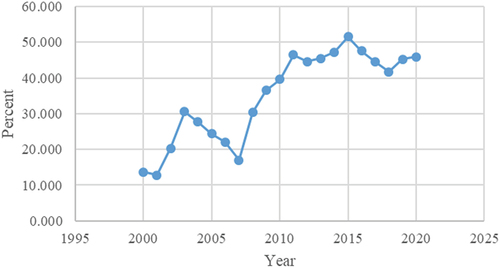

Studies have addressed contemporary agrarian development in Thailand in the globalized era with a focus on rice and rubber plantations (Chiengkul Citation2017; Doner Citation2009; J. Ricks Citation2018) and the seafood sector (Clark and Longo Citation2022). Thai agriculture has experienced at least two waves of diversification to encourage the cultivation of crops other than rice and rubber (Christensen Citation1992; Walker Citation2012). The first wave was the development of upland field crops in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by the development of other high-value agricultural commodities, including fruit and vegetables in the 1980s. These new crops changed the face of rural development in Thailand, especially after the country joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1997. In terms of the Thai export vegetable sector, edamame is not only a substantial crop for vegetable export (see ) but also a case that exemplifies the transformation of Thai agriculture.

Edamame is the name for immature soybeans that are sold either fresh or frozen in their pods and boiled before being served as an appetizer. It became popular in Japan in the 1970s before spreading across Asia. The import of edamame in Japan constitutes the biggest category of frozen vegetable trade in Asia. In the 1970s and 1980s, Taiwan was the largest exporter of frozen edamame until it was overtaken by China in the 1990s. In the 2000s, Taiwan regained its position as the leading edamame exporter in the WTO era. In 2015, Thailand surpassed China in edamame exports to become the second largest exporter in the WTO era (see ). It is therefore worth asking how the edamame SCs are embedded in the context of agricultural development in Thailand, where rice farming has remained the major agri-food sector. I found these two crops to be the primary agricultural products at my research site in the Phrao region, located in northern Thailand. While it was not surprising that Thai farmers grew rice, I was intrigued by the choice of farmers in northern Thailand to grow jasmine rice, as sticky (or glutinous) rice has traditionally been the region’s most commonly grown rice variety.

Table 1. Edamame exports from Taiwan, China, and Thailand, mt (metric tons) value (104¥) % (market share).

I am interested in exploring the power dynamics within the agricultural SCs of edamame and rice that effect changes in farmers’ decisions in crop plantation. This study argues that the power relationships between the SC system and local farmers have a significant effect on farmers’ crop-growing decisions. While the networking between farmers and the edamame supply chain is more socially sustainable, interactions with the rice SC have sometimes thwarted rice farmers and led to indebtedness. This research thus underscores the importance of understanding the role of power dynamics in the agri-SC sector and how they can influence farmers’ decisions.

The next section of this paper outlines the conceptual framework, which draws from the literature on SCs, new institutional economics (NIE), and political ecology. The paper conceptually engages with the dialogue between “a bundle of rights” and “a bundle of powers” (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003), as well as the types of social order created (North, Wallis, and Weingast Citation2009). Through this lens, the study explains why the concept of “access” can help to establish a deeper and more grounded view of access to, and control and maintenance of, resources. The subsequent sections describe the methodology of the study and the structural changes that Thai agriculture has undergone in the globalized era. The penultimate section focuses on edamame and rice smallholders’ livelihoods and the two agri-food SCs in northern Thailand in the context of the shifting political economy and ecology of the area. The final section summarizes the findings of this study.

Struggling for access to agri-food SCs

The significance of collaboration within SCs has gained recognition in recent times. However, research on agricultural SCs and resource commodity networks has yielded mixed findings (Bandara et al. Citation2017; Gramzow et al. Citation2018; Yang et al. Citation2021). Agri-food SCs are typically categorized into two main types: coercive and non-coercive (Bandara et al. Citation2017). Coercive relationships within agri-food SCs involve aggressive, forceful, and suppressive behaviors that exert influence over others through the use of punishment (Bandara et al. Citation2017). The literature has acknowledged the disadvantageous position of suppliers within the growing asymmetry of coercive relationships in agri-food SCs (Devin and Richards Citation2018; Yang et al. Citation2021). By contrast, non-coercive relationships in agri-food SCs are characterized by persuasion, cooperation, negotiation, and charisma (French and Raven Citation1959; see also Bandara et al. Citation2017).

Although studies on agri-food SCs have suggested that a cooperative mode (a non-coercive type of SC) is beneficial for food production efficiency and sustainability, such studies have tended to perceive institutions as an organizational element of agricultural production and exchange. Therefore, scholars have paid less attention to how collaboration in agri-food production reflects the unfolding of power dynamics. What is lacking is the recognition that organizations in the agriculture sector are, in part, the institutional mechanisms that coordinate the actions of individuals and groups.

Furthermore, critics have expressed concern over the attempt to centralize the governance of natural resources under the NIE perspective, particularly in terms of its emphasis on property rights and the contractual arrangements of commodity chains (Borras and Franco Citation2012; Peluso and Ribot Citation2020; Ribot and Peluso Citation2003). From a political ecology perspective, it is also important to recognize the limitations associated with the concept of “a bundle of rights” in the literature on resource access. This concept primarily emphasizes how property rights holders exercise their sanction rights to regulate resource access, focusing solely on the right to benefit from resources. Such a definition of access overlooks the concept of “a bundle of powers,” which refers to the ability to derive benefits from resources through associated structural and socio-relational mechanisms (Hansen, Myers, and Chhotray Citation2020; Peluso and Ribot Citation2020; Ribot and Peluso Citation2003). As Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003, 157) explain, “Our move from concepts of property and tenure to access locates property as one set of factors (nuanced in many ways) in a larger array of institutions, social and political-economic relations, and discursive strategies that shape benefit flows.” Thus, “access” has been defined as a broader set of socio-economic-ecological mechanisms, which includes, but extends beyond, property rights.

Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003) broadly categorize mechanisms of access into two main groups: rights-based, and structural and relational mechanisms. The first category, rights-based access, pertains to property relations that are formally recognized and sanctioned by law, custom, or convention. This category also encompasses illegal access, which refers to access that lacks social sanction. The second category, structural and relational mechanisms of access, as outlined by Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003, 164–172), encompasses various types of access, including access to technology, access to capital, access to markets, access to labor and labor opportunities, access to knowledge, access to authority, access through social identity, and access through the negotiation of other social relations. This framework is designed to be generic and heuristic, adaptable to different contexts (Hansen, Myers, and Chhotray Citation2020).

Therefore, according to Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003), an individual’s ability to access resources is contingent on the powers they hold, and these mechanisms collectively generate their ability to access resources (Hansen, Myers, and Chhotray Citation2020). As Peluso and Ribot (Citation2020, 303) further elaborate:

… we conceptualized property and access as nested concepts in which property is one kind of access—property claims are more formal; they involve formal-legal, customary, or conventional enforcement structures. It is nevertheless useful to point out that all kinds of access mechanisms and means of access—including property—begin from some kind of claim-making.

By adopting the “bundle of powers” perspective, organizations can be seen as more or less entrenched within institutional structures. This view provides a framework to bridge the concepts of NIE and the theory of access.

The NIE’s definition of an institution includes the patterns of interactions in managing resources that govern and constrain the relationships of individuals. As North, Wallis, and Weingast (Citation2009, 15) define them, institutions “span formal laws, informal norms of behavior, and shared beliefs that individuals hold about the world.” In contrast to institutions, North, Wallis, and Weingast (Citation2009, 15) see organizations as “consisting of specific groups of individuals, pursuing a mix of common and individual goals through partially coordinated behavior.” In this context, a “contractual organization” is defined as an organization characterized by both self-enforcing incentive-compatible agreements and third-party enforcement of contracts among its members. This stands in contrast to an “adherent organization,” which relies primarily on self-enforcing incentive-compatible agreements (North, Wallis, and Weingast Citation2009). North, Wallis, and Weingast (Citation2009, 7) suggest that “most organizations, even simple ones, rely on third-party enforcement of agreements and relationships between the organization’s members, or agreements between the organization and outside actors. The state most often provides third-party enforcement.”

The theory of access can facilitate a deeper and more grounded view of social and ecological components. In dialogue with the NIE approach, controlling access in the sense of “a bundle of powers” may generate economic rent through exclusive privileges, and in turn augment these privileges by improving the productivity of group members through their organizations. Consequently, the creation of economic rent not only safeguards the privileges and benefits of group members, but also fosters their loyalty, thereby averting disorder (North, Wallis, and Weingast Citation2009). Furthermore, rents can serve as incentives, as well-designed rentier relations have the potential to enhance efficiency (Cheung Citation1968). By contrast, in certain instances, rent-seeking behavior can lead to economic inefficiency due to free riding, corruption, fraud, and similar factors (North Citation1990). In other words, although the creation of rents may bind powerful groups together, the reduction of rents paradoxically becomes necessary to maintain social order.

Accordingly, the concept of access provides a framework for examining the intersection between institutions and organizations, the diverse array of agricultural practices, and how value is created through control over access. The main goal of this study is thus to delve into the power dynamics at play in collaboration and the potential disruptions that can arise within the operations of agri-food SCs. This inquiry investigates the use of violence and other coercive measures to restrict access to valuable resources, including land and labor. It also delves into how such actions are utilized to establish control over crucial activities, such as contract enforcement, property rights enforcement, and trade, ultimately shaping either contractual or adherent organizations, or even going beyond those boundaries. This study focuses on the cases of rice and edamame agriculture in northern Thailand, where globalization has put significant pressure on local agricultural practices. I utilize edamame and jasmine rice as case studies to illustrate the emergence of novel access mechanisms that operate through agri-food SCs. These mechanisms also operate within the distinct social orders adopted by local Thai farmers in northern Thailand. The paper’s analytical framework focuses on four components of the access regime of agri-food SCs: organization (contractual/adherent); institution; stakeholder; and rent. Together, they form a bundle of powers that operate through access to the agri-food SCs, as shown in .

Table 2. Access regime of agri-SCs.

Methodology

This study applies a primarily qualitative methodology to inquire about mechanisms of access and how differences in relative power and privilege create inequities through agri-food SCs in the northern region of Thailand. In the first stage of field research, in 2019, I collaborated with the owner of a local seed company to conduct field research in Phrao, one of the major edamame production sites in northern Thailand (see ). I also conducted semi-structured interviews with managers and owners of a major edamame firm, Chiang Mai Frozen Foods Public Co., Ltd. (CM), co-founded by Thai, Taiwanese, and Japanese businesspeople. The firm exports about 10,000 metric ton of edamame to Japan annually, accounting for approximately 50% of Thai edamame exports. Subsequently, with the facilitation of the local seed company, I conducted long-term surveys with local smallholders in the same area until the outbreak of COVID-19 in Thailand in May 2020. I collected 30 responses from farmers, 20 of whom allowed me to use their responses in writing this paper but preferred not to disclose their identity; of these 20 interviewees, 13 were edamame and sticky rice growers, and seven were sticky rice farmers. I summarize their responses in . In May – April 2022 and January – February 2023, after Thailand reopened its borders, I collaborated with scholars at Payup University in Chiang Mai City to conduct semi-structured interviews with farmers in Phrao. I collected 13 responses from 12 interviewees; of these interviewees, seven were edamame and rice farmers (two were also brokers) and five were rice farmers (see ). The rice farmers I interviewed grow multiple varieties of rice, including sticky rice, japonica rice, and/or jasmine rice. Farmers who are involved in either jasmine rice SCs or edamame SCs are usually capable farmers with higher capital that is needed for production.

Table 3. Livelihoods of smallholders in Phrao, Thailand.

Table 4. Smallholders interviewed in 2022 and 2023.

It is important to acknowledge the significant contributions made by agri-food research over the past two decades, particularly studies focusing on rural society in northern Thailand, which have made commendable efforts to provide a comprehensive overview of this context (Rigg Citation2019; Walker Citation2012). For instance, Walker (Citation2012, 6) explored the “new middle-income politics of peasants,” and Rigg (Citation2019) delved into the concept of peasantry being “more than rural.” Both Walker’s and Rigg’s studies have indicated that rice farmer households in northern Thailand have adopted a multifaceted approach to generating income, and it is typical for rice farmers to engage in cross-sector occupations in different seasons to sustain their livelihoods (Rigg Citation2019; Walker Citation2012). Consequently, the intra-regional mobility of these farmers blurs the line between the rural and urban areas in northern Thailand. However, most of the rice farmers I interviewed are now in their 60s. This has led to constraints on their sources of income: while they commonly engage in two to three types of agricultural production at a local scale, they no longer work as part-time laborers in the nearby cities. All my interviewees grow edamame or rice, or (in the case of four) both, and earn extra income by raising cows or chickens. This trend to some extent resonates with Walker’s (Citation2012) findings on the surge of cash crop cultivation in rural northern Thailand. However, unlike Walker’s research, which was on garlic, my findings indicate that the cultivation of new cash crops, such as edamame beans, poses a lower risk than the rice sector in Phrao. This includes both recently introduced jasmine rice and traditional sticky rice.

Thai agriculture in the globalized era

The impact of globalization in rural Thailand has been observed from many angles, including the state’s poor design of agriculture-related institutions, such as irrigation organizations (J. I. Ricks and Doner Citation2021), the dispossession of smallholders, and agricultural land grabs (Schoenberger, Hall, and Vandergeest Citation2017). These impacts have converged to create challenges to environmental sustainability (Mostafanezhad and Dressler Citation2021). Globalization can be viewed as a capitalist mechanism that controls access to natural resources for accumulation, with the state somehow integrated into this mechanism. Yet, looking at the broad patterns of access to natural resources (Borras and Franco Citation2012), the diversification of livelihoods has pushed rural Thailand beyond having only one segment of the agricultural sector as its sole source of revenue (Rigg Citation2019; Walker Citation2012), and new peasantries have thus emerged in the face of globalization (Van der Ploeg Citation2018). Therefore, there is a need to shift the focus of analysis to a relatively small scale in order to gain a more detailed understanding of agricultural practices in this context (Peluso and Ribot Citation2020). To start, it is important to say something about the role of the Thai state in the face of globalization in the agricultural sector and the state’s imperative to develop the rural areas of northern Thailand.

Following its 20-Year National Strategy (2017–2036), the Thai government announced the Agricultural Resources Development and Management Strategy and Agricultural Development Plan (2017–2021). The main objectives of these state-led efforts have been to reduce agricultural production costs, promote high-quality agricultural products, and enhance the competitiveness of Thai agriculture in the global market (FAO, Citation2018). These agricultural policies correspond with the Thai state’s development strategies to gradually liberalize agricultural regulations in response to globalization (Poapongsakorn Citation2006). The Thai state has facilitated the creation of monopolies by developing export-oriented agribusiness (Chiengkul Citation2017; Siriprachai Citation2009; Warr and Kohpaiboon Citation2007) rather than developing the “comparative advantage of the government” (Christensen Citation1992, 3) to intervene effectively for the sake of local farmers’ livelihoods (Siriprachai Citation1998). Recent studies have paid attention to the more interventionist approach taken by the Thai state in subsidizing rural development to build legitimacy (Laiprakobsup Citation2014; J. Ricks Citation2018). However, the Thai state’s strategy for developing agriculture has often aligned with transnational investment in various forms of contract farming (Chiengkul Citation2017; Doner Citation2009; Doner and Abonyi Citation2013; Poapongsakorn Citation2006). Thai agrarian development has long been jeopardized by rent-seeking behaviors operating through alliances between the landlord class and political regimes (Chiengkul Citation2017; Doner Citation2009; Siriprachai Citation2009). For instance, rubber and sugarcane have enjoyed an increasing share of the value-added crop sector due to government protections (Poapongsakorn Citation2006). In addition, the Thai government has been subsidizing new rubber plantations in northeastern Thailand since the late 1980s, and the same basic pattern of state intervention has also been seen with other crops (FAO, Citation2018; Laiprakobsup Citation2014; Poapongsakorn Citation2006).

The northern region of Thailand is the center of agricultural development, with around 30.5% of its total land area used for agriculture – the highest percentage in Thailand (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council Citation2019). It is also the region where more than two-thirds of the country’s poor live (FAO Citation2018). The region is characterized by mountainous natural highlands encompassing the upstream of major rivers, such as the Ping, Nan, Yom, and Wang rivers. The major crops cultivated in this region are field crops, such as rice, maize, beans, and other temperate plants. Maize produced for fodder markets has been booming as a cash crop in the region, accounting for 70% of the maize production in the country (Senanuch et al. Citation2022).

Studies of rural Thai politics have also highlighted the role of the local mafia and their political influence in rural areas, especially in the northern region of Thailand. These groups, collectively known as the ittiphon meurt (“dark influence”), effectively governed rural Thailand during the 1970s and 1980s. Leaders of the local society, poh liang or chao pho (“godfathers”), emerged as local powerbrokers by operating businesses that were closely related to the government’s local development projects aimed at removing the threat of communism in rural areas (Baker and Phongpaichit Citation2014; Ockey Citation1993). Poh liang were sub-district chiefs and village heads who leveraged influence in their rural communities (Ockey Citation1993). By the 1980s, electoral politics contributed to the consolidation of the poh liangs’ already well-established local spheres of influence, as many of these provincial strongmen were elected as members of Thailand’s parliament (Nishizaki Citation2018). At the same time, the steady encroachment of the market economy subverted the patron – client ties between the poh liang and villagers in rural Thailand and forced the local mafia to rely on a less dependable combination of personal and economic ties (Nishizaki Citation2002; Ockey Citation1993). Importantly, the term poh liang has different meanings to northern Thais; it is a term that can be used either negatively to denote the local mafia or positively to denote the local wealthy people who are normally the opinion leaders of the village.

Over the past several years, scholars have proposed that, alongside coercive relationships in northern Thailand’s rural society, there are also less coercive relationships emerging within certain agricultural sectors. These latter relationships have not been fully addressed in the literature. For instance, young farmers returning from the city to their hometown in rural Thailand have contributed to the establishment of innovative agricultural practices (Jansuwan and Zander Citation2021; Salvago et al. Citation2019). Indeed, case studies of agri-food SCs in other areas of Southeast Asia have pointed to a similar trend, with young returnees joining village cooperatives and making them more efficient and sustainable by re-organizing the agri-food SCs (Salvago et al. Citation2019).Footnote1

Nonetheless, elderly farmers cultivating rice in northern Thailand still depend on loans from agricultural cooperatives or other financial systems, where local opinion leaders, or poh liang, play a crucial role. As depicted in , the debt incurred by the rice farmers in this study varied from 10,000 to 100,000 Baht, with a significant portion of this debt being accrued as a membership requirement upon joining the agricultural cooperative. As rice farmers expanded their production, their debt increased from 100,000 Baht to 500,000 Baht, putting their land at risk.

Thai edamame agriculture in the globalized era

Thai edamame farmers normally grow three crops a year over three seasons. About 50% of Thai edamame beans are grown in spring, planted in April and May, and harvested between mid-June and July. Summer edamame production accounts for about 35% of total annual production. Summer crops are planted in July and August, and harvested in October and November. The remaining 15% of edamame production takes place in winter, with crops normally planted in December and January, and harvested in February and March. Chiang Mai, located in northern Thailand, is a major production site for Thai edamame. Four main edamame processing and export companies are the major buyers of edamame beans. In addition to CM, Lanna Agro Industry Co., Ltd. (LACO), founded by Thai citizens, exports about 4,000 ton of edamame to Japan annually. Union Frozen Foods Co., Ltd. and Grace Food Co., Ltd., co-founded by Thai and Taiwanese entrepreneurs, each export 1,000 ton of edamame to Japan annually. For the case study of Thai edamame SCs, I focus on CM due to its leading role in Thai edamame production.

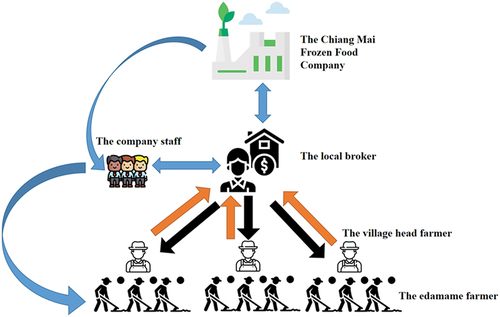

The Thai edamame agricultural sector comprises three major types of stakeholder: processing/exporting companies, local brokers, and farmers (see ). Our example company, CM, produces and distributes frozen processed vegetables such as edamame, green beans, sweetcorn, and baby corn. About 93% of its products are for export, with the Japanese market accounting for approximately 11% of total exports. For edamame production, CM operates contract farming through local brokers. CM chooses the planting area before planting a new crop of edamame through contract farming, and the company announces the quota through the local broker. The company then signs a contract with the local broker, who commits to growing the edamame in the specified area and selling it to the company at a guaranteed price. Brokers then contact their collaborators in the villages (normally the head farmers) to organize growers in their area who want to produce edamame. These farmers register with the head farmers. Before accepting the request to enter into a buyer – supplier relationship, the brokers and head farmers in the village normally conduct a survey of the land area suitable for growing edamame.

Typically, each farmer is allocated 5–10 raisFootnote2 to grow edamame. Before planting edamame, the farmers acquire seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides from the broker and his or her collaborators. The broker then calculates each farmer’s possible income and expenses. CM also sends its staff to the planting sites to monitor and survey operations. For instance, in the Phrao district, the company arranges for 2–3 staff members to help with and check every step of the growing cycle. These staff also play a role in relaying information between the producers, the farmers, the buyers, and CM. When the crop is ready to harvest, the farmers report to the head farmers the date on which they would like to harvest their crop, and the head farmers set a harvesting schedule with the company staff. The company first visits the plotted area to check whether the edamame has residual pesticides or herbicides, and then the farmers hire plenty of short-term labor to help with the 2–3-day harvesting period. Finally, CM purchases at the guaranteed price the products that pass the standardized quality tests. For edamame that does not pass the quality tests, the company may still make an offer to purchase, but at a 60% discount.

I was curious about how and why farmers in the remote areas of northern Thailand embraced and integrated this cash crop into their agricultural practices. Phrao is the major production site of edamame for CM, and indeed the major production site in Thailand. CM operates the contract for edamame through a broker named Mr. S. Mr. S used to be a soybean farmer and supplied his own products to CM. When CM decided to step into the edamame business in 1993, Mr. S was invited to join the business, and he has been in charge of organizing the local production of edamame beans since then. His tasks include providing production capital to farmers – prepayments (for harvest and transportation), seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers – through 35 production managers in the villages where the edamame farms are located. The production managers are involved in ensuring the production schedule and product quantity and quality, as well as managing contracts with Mr. S. In the interviews, Mr. S stressed the word “flexible” (klong dtua) many times, referring to one of the major characteristics of Thai edamame SCs: the quota system discussed earlier.

To offer an example of how the quota system operates, in 2022, CM assigned 300 rais of land (a quota) for edamame production to Mr. S. Along with each rai of land, everything necessary for production was included, such as prepayment, fertilizer, pesticide, and seed. Mr. S and his collaborators then set up meetings to allocate the quota to farmers based on their capacity to produce edamame beans. This quota system has multiple implications for organizing the edamame SCs. First, it is a useful way to monitor the efficiency of each farmer, as the materials for production are allocated through the quota system free of charge. However, when the products are collected by Mr. S and his collaborators (the head farmers), the payment made to the farmers for the edamame product is reimbursed to cover the cost of the materials for production. If the product cannot meet the standards and is rejected by CM, Mr. S and his collaborators normally absorb the loss for that year, but then adjust the quota allocated to that specific farmer the following year. Second, the quota system provides room to leverage the share of revenue among CM, the brokers, and the farmers. CM hires Mr. S to arrange the quota for edamame production with prepayments, which include money deposited and the materials for production. To allocate quotas and resources to farmers, Mr. S needs to assess the potential profit of the edamame product. This evaluation is typically based on the number of farmers growing edamame and the amount of land they have available to plant and harvest the beans. By controlling the amount of edamame beans that are produced, Mr. S can ensure maximum profitability for all involved parties. Third, the quota system consolidates the collaborative relationship between CM, the brokers, and the farmers. According to Mr. S’s report, the quota system has lasted since 1995—almost 30 years of practice (through trial and error, as he said) as the suppliers and the buyers have collaborated to adapt to the system. Conflicts occurred when the quota was allocated unevenly, but this has not happened since the 2000s.

Some edamame smallholders also claimed that it was more “flexible” to grow edamame than to grow rice, which resonated with Mr. S’s report. However, the term “flexible” was expressed differently, with the smallholders using the term bplian bplaeng to describe how the quota system was a strategy for approaching farming. I repeatedly heard similar statements from the smallholders, especially those who had previously been rice farmers before turning to edamame. For example, one said, “I would rather grow green soybean [edamame] than rice. Yes, growing rice is safer, but growing green soybean is more flexible.”Footnote3 For edamame production in Phrao, Mr. S and his collaborators, who often serve as the leaders of work teams in edamame production, are less strict than the production leaders for other crops. For example, they do not force smallholders into mass production and they give the smallholders considerable control over their production processes. As the main concern of edamame firms, such as CM, is to export enough product to maintain profit margins, their goal is not to maximize the harvest from each farm but to make sure that smallholders can consistently fulfill a certain production quota, which allows brokers to estimate seasonal production accurately.

However, high-quality edamame seeds, which are mostly produced in Taiwan, cannot be exported overseas due to intellectual property rights implemented by the WTO (K.-C. Wang Citation2020). Given that the quality of Thai edamame is consistently undermined by inferior seed, a significant amount (about 50%) of the smallholders’ final product is rejected by the edamame firms, as it cannot meet the required standard. Since the smallholders and edamame firms have little chance to or capability of addressing these quality concerns, their primary goal is to maintain their seasonal production, focusing instead on increasing the quantity produced. In addition, the quota system is a more reliable arrangement for farmers because the contractual packages attached to the system mean that contractors are consistently supplied with new seeds to replace inferior ones at almost no cost (and debt) to the farmer.

Furthermore, the “flexibility” the smallholders mention refers to the fact that it only takes 60 days to grow edamame from seed to harvest. Therefore, farmers can flexibly rotate edamame with other crops, which has helped smallholders adapt to environmental changes. The spring and summer rice crops in northern Thailand depend on irrigation water brought by the monsoon season. However, in recent years, crops have suffered greatly from the late arrival of the monsoons. This change has been particularly disastrous for farmers in the hills of northern Thailand, who rely on such rain-fed agriculture for their livelihoods. During the interviews, the rice farmers often complained that rainclouds had been rare during the monsoon season for the past few years, which meant insecurity and loss for them. Edamame, meanwhile, is a warm-weather plant that requires less water, making it a better choice for smallholders in the context of such climate change.

Thai rice agriculture in the globalized era

Although rice is a staple crop around the globe, it is still eaten mainly by people in Asian countries, and almost all Asian rice-eating countries produce rice for themselves. Furthermore, the cultivation of rice is contingent on location, but its symbolic meanings and significance often transcend geographical boundaries (Chan and Lau Citation2023). The total export volume of rice accounts for about 7% of global rice production (Muthayya et al. Citation2014), which is relatively low compared to other staple crops for export; since the 1990s, Thailand has been one of the largest rice exporters in the world.

The most significant change in the Thai rice export price happened in 2007–2008, when the global rice price reached a peak of about US$800 per ton. During that period, major rice producers, such as Vietnam and India, increased their rice production to compete in the global rice market (World Integrated Trade Solution Citation2010). Facing this change in the international price of rice, the Thai government, under Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra (2011–2014) launched the Paddy Pledging Program. During this period, Thai farmers sold rice at an insured price of around US$500 per ton – about twice as much as the previous price. The income of farmers increased, and therefore they were willing to take out loans to expand production. In this way, the Yingluck administration succeeded in improving the lives of farmers in Thailand and thus won the support of farmers, especially the poor farmers in northern and northeastern Thailand (Bunbongkarn Citation2015). However, as the policy drove the price of Thai rice higher than that of rice produced in other countries, rice exports from Thailand could not compete (Titapiwatanakun Citation2012).

With high rice prices, the global supply of rice increased substantially, but demand could not match it. As a result, the global rice price could not be maintained and dropped to a level even lower than before the intervention. To a certain extent, this trend has persisted. It is estimated that the Thai government has spent more than US$30 billion on rice purchases since the global rice price dropped (Poapongsakorn Citation2019). To address the deficit resulting from the implementation of the Paddy Pledging Program, the government planned to borrow money from the Government Saving Bank (GSB), but the People’s Democratic Reform group (Gor Bpor Bpor Sor) disrupted the plan (Khaosod English Citation2014). The Paddy Pledging Program was canceled after the Yingluck administration collapsed, and since then, Thai grain merchants have purchased rice from farmers for around US$200 per ton (Tanakasempipat Citation2016).

Rice farming in northern Thailand produces sticky rice and jasmine rice. In general, Thai rice smallholders in this area own land ranging from 2 to 5 rais, which is equal to 2–3.2 acres, but they normally lease more land from other farmers who are not currently practicing agriculture. In contrast, I found that farmers in the area of Phrao own around 20 rais of land on average. The land plots used by rice-producing smallholder households are about twice the size of those used by edamame and vegetable smallholders. Some of the land owned by rice farmers was purchased from other farmers using loans provided by Thaksin-era projects (i.e., Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, 2001–2006), notably funds administered by the Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Development Bank and the Village Development Fund (VDF). Although the Paddy Pledging Program was discontinued in 2014, the VDF has continued, providing 1 million Baht (about US$30,000) of loans to ordinary rural people in villages at an interest rate of 6% (Boonperm, Haughton, and Khandker Citation2013). Further, although the SME Development Bank no longer provides loans, the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC) has begun extending loans to rice smallholders at almost the same interest rate (although rice farmers must obtain loans from local farmer cooperatives).

Therefore, land ownership, conventional agricultural patterns, and financial support from the government mean that growing rice is still profitable for some smallholders, although the wholesale price of rice (including sticky rice and jasmine rice) at 7–12 Baht per kg is lower than that of edamame beans and vegetables (17–28 Baht per kg). As well as rice farming, smallholders often have other sources of revenue, such as from raising animals and growing cash crops. Consequently, as came to light in my survey, only 30–50% of most smallholders’ household income comes from growing rice. It is also important to note that not every smallholder household has the ability to grow rice. Rice farmers normally own the land they work (through a title deed), which must be of a reasonable scale for their livelihood, and if necessary, additional income can help them to expand their land to become a larger-scale farmer. However, the Thai government treats land titles as a qualification for accessing loans, and farmers who possess their land under an S.K.1 title or an N.S.2 title,Footnote4 which do not legally count as full ownership of the land, are in a weaker position than those who own their land outright.

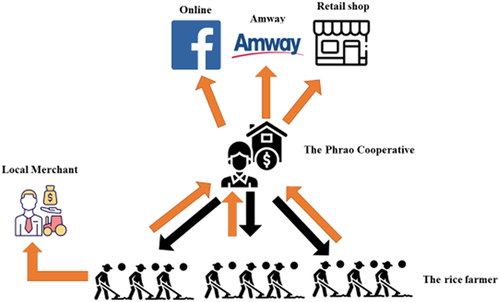

Smallholders from the Global South have been exposed to the extreme concentration of the global industrial food system at multiple scales (Clapp Citation2020). Against the backdrop of adapting jasmine rice agriculture in Southeast Asia to the increasing demand from China (Green Citation2022), the Thai central government has initiated a series of policies to promote jasmine rice agriculture since 2000. In northern Thailand, the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative is a major cooperative that focuses on commercializing jasmine rice. The farmers in the Phrao district must apply to be members of the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative to be allowed to join the jasmine rice planting program. The program provides training, seed, fertilizers, and pesticides to members. The cooperative is also a source of financial support. Members of the cooperative are qualified (and required) to borrow money for their jasmine rice farming, and they must sell their rice back to the cooperative. Furthermore, the cooperative guides farmers’ practices based on the GAP (Good Agriculture Practices) system, including through control and supervision of the rice fields.

After receiving rice from the farmers, the cooperative takes it to its own rice mill for processing. Finally, the cooperative distributes milled rice to its three major retail channels: direct sales, Amway (a national retailer chain), and local retail partners (see ). For direct sales, the cooperative uses telephones and Facebook to communicate with customers and receive orders. Then, they send their milled rice through the Thai postal service or private logistics companies. Amway is a partner of the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative, purchasing around 20% of the organization’s milled jasmine rice. In addition, Amway has established an OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) contract with the cooperative for around 200 tons of milled jasmine rice per year. The most important partners of the cooperative are the local retail shops in Chiang Mai and Lamphun provinces; this channel accounts for around 70% of the total milled jasmine rice. Local retail shops are preferred mostly because the sellers can obtain cash almost immediately, and hence farmers and producers can receive revenue quickly. It seems that the implementation of the jasmine rice program by the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative has the potential to create a profitable niche for local rice farmers. However, most of the rice farmers I interviewed are still in debt, and the cooperative understates the hidden costs associated with joining the jasmine rice program.

Arguably, farmers’ debt issues cannot be fully resolved by joining the jasmine rice program. Three farmers I interviewed held large areas of land for growing rice (Mr. A: 27 rais, Mr. W: 40 rais, and Mr. C: 35 rais), but had little interest in joining the program or had withdrawn from the program. For instance, Mr. W was leasing 40 rais of land as the main collaborator with the edamame broker Mr. S, managing contract edamame in the Phrao area, but he was also one of the few major farmers in the region growing japonica rice for export. Mr. W explained that he had not joined the jasmine rice program because he did not want to be trapped by accruing debt, and joining the program would have meant that he had an obligation to borrow money from the cooperative. Even though he was capable of shouldering the relatively high interest rate of around 10% per year set by the cooperative, he preferred to use his own money to grow japonica rice at a slightly lower wholesale price (japonica: 9 Baht/kg versus jasmine: 12 Baht/kg). Growing edamame was a more profitable option for him.

Another farmer, Mr. A, who owned 27 rais of land and was growing both sticky and jasmine rice, explained why he was not part of the cooperative:

If we are a member of the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC), we are not allowed to be a member of the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative. That is why I have decided to withdraw from the project; in fact, I can still make enough profit by growing different kinds of jasmine rice (different from the variety promoted by the cooperative) and sticky rice without the support of the cooperative[s].

Similarly, Mr. C had been a rice farmer since 1995, but in 1999 due to the decline in profit from growing rice, he had followed Mr. W, the senior farmer in his village, in joining the group of edamame growers, while continuing to grow rice. His 35 rais of land were divided into 23 rais for edamame (rotated with sweetcorn) and 12 rais for sticky rice in the dry season; in the rainy season, he used all his farmland to grow sticky rice. Mr. C explained to me why he had withdrawn from the jasmine rice cooperative:

The net profit from growing jasmine rice is almost the same as for the sticky rice; besides, it requires a longer period to grow jasmine rice than sticky rice. Moreover, jasmine rice is fragile, as it’s easy to contaminate it with plant diseases, so I’ve spent more time spreading herbicides and pesticides when growing jasmine rice … The harvest of sticky rice is divided into [rice for] my household consumption and sales to the rice middlemen from other villages.

In general, however, regardless of the type of rice being cultivated, such as sticky or jasmine rice, rice farmers are often in debt, as shown in . The only distinguishing factor is that those farmers who have more land and a better financial position can use their debt to invest in other areas of agriculture, such as growing edamame beans. Farmers with smaller land holdings must repay their debt and often only pay back the interest on the loan from the bank or the cooperative. A local rice farmer who had just lost her husband and was deeply indebted to a local cooperative explained to me that, after her husband passed away, “They transferred the debt from my husband’s account to mine in violent ways, so I am forced to be trapped in debt.”Footnote5

Discussion and conclusion

More than a decade ago, the rise of industrial agriculture in Southeast Asia was presented in Taking Southeast Asia to Market, edited by Joseph Nevins and Nancy Lee Peluso (Citation2008). The process has escalated, furthering the capitalist system and revealing a new stage of capital accumulation of resources and land that strengthens capitalism’s hold on people and the environment, mass farmland acquisition, and resource enclosure. Meanwhile, the trend toward the regionalization of commodity flows, as part of the intensification of the regional division of labor in Southeast Asia and beyond, has positioned certain Southeast Asian countries as centers for the production and circulation of agricultural commodities.

The reconfiguration of the agricultural landscape in northern Thailand has involved different forms of access to resources. Local political leaders have had an important influence in northern Thailand for decades, and many function as village leaders, core members of the local agricultural cooperatives, and/or local businesspeople. This enables them to secure significant power in the agricultural sector by acting as middlemen or as local agents for the government (which controls the allocation of agricultural subsidies).

From the traditional perspective of SCs, one promising way to sustainably develop the agricultural sector is through cooperative relationships. However, the rice and edamame smallholders involved in the agricultural SCs in this study were subject to various power dynamics that affect both their positionalities in chain relationships and the overall sustainability of the supply chain. Some smallholders and farmers have been able to improve their livelihoods by changing their agricultural practices and accessing new opportunities, such as the agri-SCs of edamame. However, the rice smallholders still rely on agricultural cooperatives to provide them with capital, which makes it difficult for them to free themselves of debt. As summarized in , a bundle of powers that functioned as an access regime through state intervention seemed more prevalent in the rice chains than in the edamame chains. The main reason for this difference, as I have demonstrated, is related to the historical-political evolution of this region’s agriculture.

Table 5. Access regime of agri-SCs in Phrao.

The jasmine rice planting program promoted by the Phrao Agricultural Cooperative functioned as an organization that adhered to the wishes of the local elite group and opinion leaders. Hence, many rice smallholders were caught up in debt due to local power regimes. As previously mentioned, the farmers’ debt is the financial sector’s profit – which in this case is controlled by the local agricultural cooperative. The cooperative essentially operates a coercive loan contract, which can be seen as “rent-seeking behavior” or “rent generation” in the terms of NIE. The organizational structure of edamame SCs is different from that of the rice SCs. In edamame SCs, a lead firm manages the supply chains through legal contracts that are enforced by third-party local brokers and collaborators. This contractual organization helps to control rent-seeking behaviors and, with the quota system, edamame SCs avert the problem of farmers accumulating debt, thereby reducing rent. To conclude, it has been shown that Thai farmers are deeply entangled in a complex web of power dynamics in the agri-food SCs, some of which are socially sustainable and enhance their economic survival while others have been more coercive.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the outcome of a research plan that lasted several years, funded by the NSTC of the Taiwan government and the RCHSS at Academia Sinica. I want to express my appreciation to my research assistants from Thailand – Porntep, Aom, and Boyle – for their invaluable help during my field research. I extend special thanks to Porntep for his assistance in translating the Lan Na language. Yuk Wah Chan offered insightful comments and critiques that helped refine the paper, and I’m grateful for the anonymous reviewers’ comments. Any mistakes in the paper are solely my responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The majority of interviewees for this paper were older farmers, around the age of 60. However, an interesting trend was observed whereby their sons or relatives returned from urban areas to assist in maintaining the agricultural practices.

2. 1 rai equals 1600 square meters.

3. Thai edamame farmer, Mr. Punvongsa, 10 March 2020.

4. S.K.1: This document provides evidence of possessing land but does not show ownership of the land. The state used to issue these documents when farmers applied for a title deed as evidence of possession of the land (the documents are no longer issued). According to the law, the person who possesses a piece of land has the right to possess it and can transfer and disclaim it. In addition, the person who possesses the land can apply for a title deed and certificate of utilization if there are no disputes with other people. N.S.2: This document allows for temporary occupation of land distributed by the land department through the land distribution program. If all conditions are met, the owner of the document can apply for a certificate of utilization and title deed.

5. This interviewee chose to keep her identity anonymous.

References

- Baker, C., and P. Phongpaichit. 2014. “A Short Account of the Rise and Fall of the Thai Technocracy.” Southeast Asian Studies 3 (2): 283–298. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.2_283.

- Bandara, S., C. Leckie, A. Lobo, and C. Hewege. 2017. “Power and Relationship Quality in Supply Chains: The Case of the Australian Organic Fruit and Vegetable Industry.” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics 29 (3): 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-09-2016-0165.

- Boonperm, J., J. Haughton, and S. R. Khandker. 2013. “Does the Village Fund Matter in Thailand? Evaluating the Impact on Incomes and Spending.” Journal of Asian Economics 25 (3): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2013.01.001.

- Borras Jr., S. M., and J. C. Franco. 2012. “Global Land Grabbing and Trajectories of Agrarian Change: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (1): 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00339.x.

- Bunbongkarn, S. 2015. “What Went Wrong with the Thai Democracy.” In Southeast Asian Affairs, edited by D. Singh, 359–368. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Chan, Y. W., and J. H. L. Lau. 2023. “Producing Rice, Eating Tradition? A Multiscalar Ricescape in Hong Kong.” Food, Culture & Society 1–22. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2023.2284051.

- Cheung, S. 1968. “Private Property Rights and Sharecropping.” Journal of Political Economy 76 (6): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1086/259477.

- Chiengkul, P. 2017. The Political Economy of the Agri-Food System in Thailand: Hegemony, Counter-Hegemony, and Co-Optation of Oppositions. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Christensen, S. 1992. “The Role of Agribusiness in Thai Agriculture: Toward a Policy Analysis.” TDRI Quarterly Review 7 (4): 3–9.

- Clapp, J. 2020. Food. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Clark, P. T., and S. B. Longo. 2022. “Global Labor Value Chains, Commodification, and the Socioecological Structure of Severe Exploitation. A Case Study of the Thai Seafood Sector.” Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (3): 652–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1890041.

- Devin, B., and C. Richards. 2018. “Food Waste, Power, and Corporate Social Responsibility in the Australian Food Supply Chain.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (1): 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3181-z.

- Doner, R. 2009. The Politics of Uneven Development: Thailand’s Economic Growth in Comparative Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Doner, R., and G. Abonyi. 2013. “Upgrading Thailand’s Rubber Industry: Opportunities and Challenges.” Thammasat Economic Journal 31 (4): 44–66.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2018. Country Fact Sheet on Food and Agriculture Policy Trends Socio-Economic Context and Role of Agriculture. Bangkok: FAO Country Office in Thailand.

- French, J. R. P., and B. Raven. 1959. “The Bases of Social Power.” In Studies in Social Power, edited by D. Cartwright, 150–167. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

- Gramzow, A., P. J. Batt, V. Afari-Sefa, M. Petrick, and R. Roothaert. 2018. “Linking Smallholder Vegetable Producers to Markets: A Comparison of a Vegetable Producer Group and a Contract-Farming Arrangement in the Lushoto District of Tanzania.” Journal of Rural Studies 63:168–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.07.011.

- Green, W. N. 2022. “Placing Cambodia’s Agrarian Transition in an Emerging Chinese Food Regime.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (6): 1249–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1923007.

- Hansen, C. P., R. Myers, and V. Chhotray. 2020. “Access Revisited: An Introduction to the Special Issue.” Society & Natural Resources 33 (2): 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1664683.

- IndexMundi. n.d. “Insert Specific Webpage Accessed.” Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.indexmundi.com/.

- Jansuwan, P., and K. K. Zander. 2021. “What to Do with the Farmland? Coping with Ageing in Rural Thailand.” Journal of Rural Studies 81:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.12.003.

- Khaosod English. 2014. “GSB Boss Resigns, Cancels Loans for Rice Program.” February 18, 2014. https://www.khaosodenglish.com/news/business/2014/02/18/1392720844/.

- Laiprakobsup, T. 2014. “Populism and Agricultural Trade in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Thailand’s Rice-Pledging Scheme.” International Review of Public Administration 19 (4): 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2014.967000.

- Mostafanezhad, M., and W. Dressler. 2021. “Violent Atmospheres: Political Ecologies of Livelihoods and Crises in Southeast Asia.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 124:343–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.010.

- Muthayya, S., J. D. Sugimoto, S. Montgomery, and G. F. Maberly. 2014. “An Overview of Global Rice Production, Supply, Trade, and Consumption.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1324 (1): 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12540.

- Nevins, J., and N. L. Peluso, eds. 2008. Taking Southeast Asia to Market: Commodities, Nature, and People in the Neoliberal Age. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Nishizaki, Y. 2018. “New Wine in an Old Bottle: Female Politicians, Family Rule, and Democratization in Thailand.” The Journal of Asian Studies 77 (2): 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002191181700136X.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C., J. J. Wallis, and B. R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ockey, J. 1993. “Chaopho, Capital Accumulation, and Social Welfare in Thailand.” Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 8 (1): 48–77.

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. 2019. Northern Development Plan. (In Thai, Review). Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

- Peluso, N., and J. Ribot. 2020. “Postscript: A Theory of Access Revisited.” Society & Natural Resources 33 (2): 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1709929.

- Poapongsakorn, N. 2006. “The Decline and Recovery of Thai Agriculture: Causes, Responses, Prospects and Challenges.” In Rapid Growth of Selected Asian Countries: Lessons and Implications for Agriculture and Food Security: Republic of Korea, Thailand and Viet Nam, edited by P. K. Mudbhary. Bangkok: Regional FAO Office for Asia and the Pacific. https://www.fao.org/3/ag087e/AG087E00.htm.

- Poapongsakorn, N. 2019. “Overview of Rice Policy 2000–2018 in Thailand: A Political Economy Analysis.” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform. https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1426.

- Ribot, J., and N. L. Peluso. 2003. “A Theory of Access: Putting Property and Tenure in Place.” Rural Sociology 68 (2): 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x.

- Ricks, J. 2018. “Politics and the Price of Rice in Thailand: Public Choice, Institutional Change and Rural Subsidies.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (3): 395–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1419275.

- Ricks, J. I., and R. F. Doner. 2021. “Getting Institutions Right: Matching Institutional Capacities to Developmental Tasks.” In World Development, 139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105334.

- Rigg, J. 2019. More Than Rural: Textures of Thailand’s Agrarian Transformation. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Salvago, R. M., K. Phiboon, N. Faysse, and T. P. L. Nguyen. 2019. “Young People’s Willingness to Farm Under Present and Improved Conditions in Thailand.” Outlook on Agriculture 48 (4): 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727019880189.

- Schoenberger, L., D. Hall, and P. Vandergeest. 2017. “What Happened When the Land Grab Came to Southeast Asia?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (4): 697–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1331433.

- Senanuch, C., T. W. Tsusaka, A. Datta, and N. Sasaki. 2022. “Improving Hill Farming: From Maize Monocropping to Alternative Cropping Systems in the Thai Highlands.” The Land 11 (1): 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010132.

- Siriprachai, S. 1998. “Export-Oriented Industrialisation Strategy with Land Abundance: Some of Thailand’s Shortcomings.” Thammasat Economic Journal 16 (2): 83–138.

- Siriprachai, S. 2009. “The Thai Economy: Structural Changes and Challenges Ahead.” Thammasat Economic Journal 27 (1): 148–229.

- Tanakasempipat, P. 2016. “Thailand’s Junta Seeks to Reassure Powerful Rice Farmers Amid Price Plunge.” Reuters. November 3, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-politics-rice-idUSKBN12Y0AV.

- Titapiwatanakun, B. 2012. The Rice Situation in Thailand. Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

- Van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. The New Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization. New York: Routledge.

- Walker, A. 2012. Thailand’s Political Peasants: Power in the Modern Rural Economy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Wang, K.-C. 2020. “The Art of Rent: The Making of Edamame Monopoly Rents in East Asia.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 3 (3): 624–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619880552.

- Wang, L., J. Luo, Y. Liu, and L. Vasa. 2021. “Agricultural Cooperatives Participating in Vegetable Supply Chain Integration: A Case Study of a Trinity Cooperative in China.” Public Library of Science One 16 (6): e0253668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253668.

- Warr, P. G., and A. Kohpaiboon. 2007. Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Thailand. Report no. 56079. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/469601468339594968/main-report.

- WITS (World Integrated Trade Solution). 2010. “Cereals; Rice, Semi-Milled or Wholly Milled, Whether or Not Polished or Glazed Exports by Country in 2010.” Accessed March 22, 2023. https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ALL/year/2010/tradeflow/Exports/partner/WLD/product/100630.

- Yang, Y., M. H. Pham, B. Yang, J. W. Sun, and P. N. T. Tran. 2022. “Improving Vegetable Supply Chain Collaboration: A Case Study in Vietnam.” Supply Chain Management 27 (1): 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-05-2020-0194.