ABSTRACT

While several studies have explored strategic communication in relation to military intervention, this study analyses communicative strategies in the context of military withdrawals and redeployments. We focus on the case study of the United States withdrawal from Afghanistan to analyse which (and how) strategic narratives were discursively mobilised by the US administration on Twitter (now known as X) to seek public support and legitimacy for its operations. Findings suggest that key narratives of securitisation, national interest and responsibility were deployed through macro strategies of transcendence, bolstering, blaming and mitigation. We claim that while early representations of the war in Afghanistan were depicted as an unavoidable mission, the overarching discourse has now shifted to portrayals of the war being unsustainable and no longer needed by the United States.

Introduction

The American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 represented the epilogue of a two-decade-long conflict started under the ‘war on terror’ campaign in the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States of America (US). The US military operation started by President Bush was initially aimed at ousting the Taliban from power and reinstating the Afghan state institutions and was subsequently supported by an international operation under the UN mandate. Under the first Obama administration (2009–2013), US troops were increasingly deployed on Afghan soil to prevent Taliban attacks and to promote a gradual restoration of Afghan civil society, while it was agreed that security responsibilities would eventually be handed over to the Afghan army. However, a subsequent surge of Taliban attacks and an ill-prepared Afghan army meant that by the time NATO formally completed its task in 2014, the situation on the ground was far from stable. Against this backdrop, in 2018 the incumbent President Trump committed to a drastic reduction of the US presence in Afghanistan and a final withdrawal agreement with the Taliban was signed in Doha. The agreement was then executed by President Biden and full withdrawal of the US troops was announced in April 2021.

Focusing on TwitterFootnote1 as a key communicative platform for the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, this study contributes to the existing literature on communication crisis by identifying discursive patterns adopted by the US administration to represent and, more crucially, legitimise its actions around the withdrawal from Afghanistan. While events related to the 2021 American withdrawal from Afghanistan have been analysed extensively in sociological, political and military studies, as well as by a wealth of interdisciplinary work, the topic remains less explored within the strategic communication field (however, see Vyklický and Divišová (Citation2021) for a Czech perspective on NATO activities in Afghanistan). Moreover, while research into communicative strategies around military intervention has been prolific (e.g. Roselle, Citation2006), to our knowledge there have been fewer studies examining communication management in relation to withdrawal and redeployment operations (e.g. Ringsmose & Børgesen, Citation2011). Our research therefore aims to critically address the question of the overall management of communication around topical events related to the withdrawal, with a specific focus on the time frame between 1 April 2021 and 30 October 2021. We primarily treat the US administration’s discursive productions as an instantiation of (political) crisis communication (Coombs, Citation2018) aimed at mitigating, justifying and, ultimately, (de)legitimising specific actions and actors (as we elaborate further in section 2). Via a critical discourse analysis (Wodak & Meyer, Citation2009), this study focuses on the discursive positioning of the withdrawal by the Biden administration not only in relation to specific military goals but also in relation to the larger-scale legitimisation of US international operations. More specifically, our study addresses the following research questions: a) Which discursive strategies did President Biden’s administration adopt on Twitter to communicate the US withdrawal from Afghanistan between 1 April and 30 October 2021? b) Through which narratives was the withdrawal legitimised?

The article proceeds as follows. We outline a theoretical framework by drawing on relevant literature on crisis communication strategies and legitimation followed by a discussion of our research methodology and the dataset for this study. The subsequent section elaborates on the results of this research. Conclusions are drawn in the final section.

A theoretical approach to crisis communication and legitimation

Crisis communication – that is, communication produced and consumed in relation to events potentially threatening an organisation’s reputation – is a key strategic tool in pre-empting and responding to a crisis (Coombs & Holladay, Citation1996). According to Coombs (Citation2010) situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), effective communication should be the organisation’s response to the perceived threat posed by a crisis, the latter interpreted as a staged lifecycle of events that unfold from incubation to physical manifestations of the emergency and to the restoration period. The SCCT postulates different potential communicative strategies an organisation can adopt in managing the crisis effectively. Underpinned by the principle of attribution of responsibility, these strategies range from framing the organisation as either responsible for the crisis events or a victim of them to apologising, denying, mitigating and bolstering, to name some of the most common responses an organisation will typically invoke to navigate a crisis (Coombs, Citation2007).

More widely, communication performed amidst a crisis can be regarded as a discursive process of legitimation (Falkheimer, Citation2021) through which certain social actors strategically aim to influence an audience so that their actions are perceived as “desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). In this sense, communication should be the organisation’s response to a perceived risk that undermines the organisation’s social activities, and ultimately its very raison d’être. According to Coombs (Citation2006, p. 249), in crisis situations, “deal-response” communication “can be viewed as efforts to restore legitimacy by directly addressing how stakeholders view the organisation-efforts to reshape its reputation”. Legitimacy and its communication have been the concern of many studies focusing on commercial organisations as well as on institutional and political actors such as governments. For example, the management of public communication during a crisis as a strategic legitimacy tool has been extensively analysed from managerial perspectives (Holmström et al., Citation2009; Kryger Aggerholm & Thomsen, Citation2016; Vaara & Monin, Citation2010). Equally, attention has been paid to legitimacy dynamics in public governance communication at the intersection of its political and public relations functions (Hallahan et al., Citation2007), whether that be in the context of global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Svenbro & Wester, Citation2023; Tench et al., Citation2022) or in national socio-political crises such as Brexit (Zappettini & Krzyżanowski, Citation2021). There is also an established academic field of work that has analysed legitimacy from political perspectives by zeroing in on the democratic right of certain authorities (such as the state and associated institutions) to rule and to make decisions on coercive power that would affect citizens or other states (Peter, Citation2008). Crisis communication management is therefore also key to any military operation, as testified by a long-established tradition of academic work in the field of strategic communication (Hallahan et al., Citation2007), this emerging on the back of the US government’s management of public diplomacy, security and military activities in Iraq and Afghanistan (Paul, Citation2011).

The nexus between political crisis management and legitimacy holds especially true as the production and consumption of messages are increasingly reliant on mass mediatisation (Holtzhausen & Zerfass, Citation2015). Political crises and the associated communicative processes of legitimation are nowadays performed in the networked public sphere (Friedland et al., Citation2006), which involves the production and consumption of messages by institutions, the media and the networked public (Boyd et al., Citation2010). By and large, the growth of social media has enabled politicians to engage directly with the public, bypassing conventional media in the process to rapidly disseminate information to a larger audience and influence public opinion. As digital platforms such as Twitter are increasingly regarded by the public as an official source of information (Bruns et al., Citation2012), governments are turning to digital forms of diplomacy (Su & Xu, Citation2015) to handle political crises by building consensus in public opinion (Farwell, Citation2012) and to reassert their legitimacy in the networked public sphere.

Starting from this conceptualisation of strategic communication and legitimacy, we focus in this article on the discursive enactment of legitimacy by drawing from social constructivist and critical stances (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966; Foucault, Citation1972). We therefore recognise that communication not only reflects events and social actors, but it constructs them within dominant ideological frames (Ericson, Citation1998). In this sense, we see communication as strategic inasmuch as it re-presents semiotically the goal of powerful actors (Hall, Citation2013), while platforms such as Twitter can act as strategic sound boxes for power to reproduce and legitimise existing hierarchies in an international order (Miskimmon et al., Citation2013).

In many respects, therefore, one can see social platforms enabling the performance (Demasi et al., Citation2021; Zappettini & Maccaferri, Citation2021) of crisis communication within a rhetorical arena (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2022) where leadership is arguably expected to seek public consensus to sustain its legitimacy and discourse is ultimately aimed at rationalising and justifying certain decisions or actions. Discursive representations like those produced on Twitter by official government accounts can thus be seen as part of strategic overarching (de)legitimising narratives (Ringsmose & Børgesen, Citation2011; Zappettini & Bennett, Citation2022) aimed at influencing public perceptions, including the extent to which the national interest is deemed to be at stake and national security at risk (Eichenberg, Citation2005; Jentleson, Citation1992; Record, Citation1993). As suggested by Ringsmose and Børgesen (Citation2011), the discursive mobilisation of strategic narratives by institutional actors should be seen as being aimed at managing public sensitivity and acceptance of the human costs of war, since strategic narratives act as stories which must convey “a sense of cause, purpose, and mission” (Arquilla & Ronfeldt, Citation2001, p. 328) to sanction the legitimacy of specific goals. Leveraging both cognitive consistency and emotional appeal, strategic narratives are thus produced to resonate with an audience by promoting particular views of the world which somehow dovetail with the audience’s core values and help them make sense of events consistently and with values and beliefs (Miskimmon et al., Citation2013). Just as “decision makers are [.] actors endowed with the capacity to mobilise support for military intervention” (Ringsmose & Børgesen, Citation2011, p. 507), strategic narratives can be invoked by social actors for reverse operations, such as withdrawals and redeployments. While Ringsmose and Børgesen (Citation2011) by and large equate narratives with Entman’s (Citation1993) conceptualisation of framing (by referring to the description of events in an explanatory, cause-effect framework), we focus in this study on the legitimacy aspect of a narrative. We thus treat legitimation as a discursive process reliant on appealing to specific rational justifications or specific moral arguments (van Leeuwen & Wodak, Citation1999) to naturalise a particular version of the story (Forchtner & Özvatan, Citation2022). To operationalise the analysis of legitimation and strategic narratives, we conduct a critical discourse analysis (which we explain in detail in the next section) with a focus on both propositional (content) and stylistic (form) dimensions of communication.

Data and methodology

Official Twitter accounts of five key actors in the Biden administration were examined (see ). These accounts were chosen for their representativeness of the US administration’s discourse, as they are the official institutional voices of the US government – in other words, they represent the “principal” speaker in Goffman’s (Citation1981) terms. An advanced search, which is a search feature on Twitter that allows users to define specific parameters of a query (e.g. account name, time frame, etc), was run for all tweets produced by these five accounts. The timeframe for this search was between 1 April and 30 October 2021, which largely covers all public communication from the announcement of the troops’ withdrawal on 14 April to the departure of the last US soldier on 30 August 2021. The extended period to 30 October 2021 traces further communication following the withdrawal. The advanced search for tweets contained these terms: “Afghanistan”, “Afghan”, “Taliban”, “Ghani”, “Abdullah”, “peace” and “Doha”. Tweets were then downloaded through www.exportcomments.com, and the website’s nested comment feature was utilised to ensure the retrieval of all nested tweets within a tweet thread. Furthermore, a manual approach was employed to download tweets to ensure that no relevant tweets were overlooked. Irrelevant posts were subsequently removed, resulting in a total of 302 tweets retained. Transcripts of President Biden’s speech videos embedded in his tweets were also analysed.

Table 1. Details of data analysed.

The data were initially sorted and filtered within an Excel file. Subsequently, these files were transferred to NVivo 12 software to facilitate coding and analysis. NVivo 12 was selected as the preferred tool due to the intricate nature of the data. The software supported structured analysis, enabling the creation of nodes based on tweets or specific segments of a tweet. Due to resource constraints, our analysis focused only on written text and not on visual elements.

Texts (tweets and speech transcripts) were analysed via critical discourse analysis (CDA). CDA is an umbrella term for different methodological approaches that share the common goal of showing the close relationship between texts (as manifestations of discourses or larger units of meaning) and social dynamics. In particular, according to van Dijk (Citation2015, p. 467), CDA is concerned with studying the way power relations are “enacted, reproduced, legitimated, and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context”. Following this general analytical orientation, our study followed the CDA procedure proposed by Wodak and Meyer (Citation2009). Our analysis was thus concerned with identifying: a) key discursive themes or topics; b) key discursive strategies (macro level); and c) their means of linguistic realisation (micro level). More specifically, the data were initially coded with NVivo 12 to identify recurrent patterns of topicalisation. In other words, we mapped out key themes based on how they were made salient in a tweet (this is equivalent to the ‘aboutness’ of news one could derive from article headlines in a newspaper; see, for example, Zappettini & Maccaferri, Citation2021).

In relation to the concept of discursive strategy, we followed Wodak and Meyer’s (Citation2009) treatment of a strategy as “a more or less intentional plan of practices … adopted to achieve a particular social, political, psychological or linguistic goal” (p. 94), which in our case we assumed would primarily be (de)legitimising an action or an intention, and which we ascribed to identifiable strategic narratives based on our interpretation of how a specific (de)legitimising utterance would fit a larger story plot. We integrated this notion of strategy with Coombs (Citation2015, Citation2018) specific insight into crisis management strategies as discussed in the previous section. At the micro-linguistic level, attention was paid to argumentative structures. In particular, we systematically scrutinised the use of topoi (Wodak & Meyer, Citation2009) which, in moral or rational argumentative schemes, constitute the explicit or implicit underlying assumptions warranting the conclusion of an argument. We interpreted these in line with logical continuity within a narrative plot. In analysing the language of tweets and speeches, we also took into account the notion of speech act performativity (Austin, Citation1962) that would see a specific social action performed and sanctioned primarily through language (e.g. to say ‘I apologise’ is to perform an act of apology). Finally, we scrutinised lexical features that would characterise tweets and speech transcripts, such as metonymy, metaphor, modal verbs, intertextual/interdiscursive references, rhetorical devices, and affective and emotive language (Martin & White, Citation2005) to identify their discursive functions (e.g. what cognitive implications could be derived from metaphorical language adopted by the US administration).

Analysis

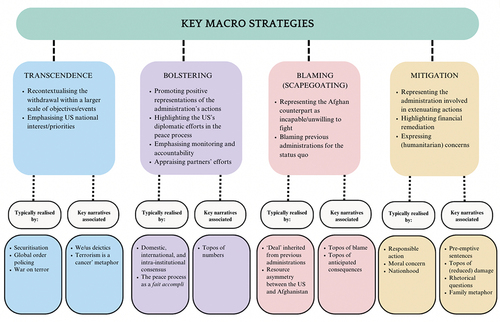

A set of key discursive themes, strategies, narratives and linguistic features emerged from the analysis of the official accounts under scrutiny. These are presented in and . By and large, themes referred to operation- and evaluation-oriented topics. Operation-oriented topics largely encompass tweets and passages from the speech transcripts which primarily discussed evacuation logistics and/or diplomatic, organisational and governmental activities from a seemingly neutral standpoint (e.g. consultations with allies and other political actors); these typically took the form of statements and made use of active verbs (e.g. “Over the coming days, we intend to transport out thousands of American citizens who have been living and working in Afghanistan”). Evaluation-oriented topics relate to tweets and transcripts in which the speaker’s voice took a clear evaluative stance and made frequent use of emotive language (e.g. “[These scenes] are gut-wrenching, particularly […] for those who have lost loved ones in Afghanistan, and for Americans who have fought and served in the country”).

Table 2. Most frequent key themes/topics in accounts analysed.

Figure 1. A synopsis of the key themes, strategies, narratives and linguistic features of the US administration tweets analysed.

Distribution across the accounts showed some variations, which we have summarised in .

Themes relating to evaluation-oriented topics such as the US strategic goals and shifts in policies featured more frequently in Biden’s (31%) and Psaki’s (11%) tweets than in other accounts, while Blinken’s tweets primarily discussed operation-oriented topics such as collaboration with US allies (14%), appraising US allies’ and army efforts (13%), and diplomacy efforts (5%). Similarly, tweets produced by the White House’s account overtly focused on operational topics related to the evacuation (27%), while Khalilzad’s communication tended prominently to represent diplomatic efforts for the intra-Afghan peace process (27%) and the social, cultural and political consequences of withdrawal for the Afghan nation.

Our in-depth macro analysis identified a set of key strategies that frequently drove the administration’s tweets across the five accounts. By and large, we found that deal response strategies (Coombs, Citation2006) were most frequently utilised by the administration. This overall strategic orientation resulted in the administration adopting specific macro strategies of transcendence, bolstering, blaming/scapegoating, and mitigating both to legitimise its decision to withdraw vis-à-vis various actors and stakeholders and, at the same time, to delegitimise its permanence on Afghan soil, as we elaborate further below. In the discussion of each of these strategies, we also elaborate on specific micro means of realisation (linguistic features) and on how these strategies relate to larger narratives.

Transcendence

Our data suggest that strategies of transcendence were often appealed to by the US administration in its tweets. By transcendence, we refer to the communicative goal of persuading an audience to view specific acts in a wider context of events (see, for example, Hearit, Citation1997). For instance, in Extract 1, President Biden discusses the reason for invading Afghanistan and how it relates to the current and future strategic goals of the United States:

Extract 1

We went to Afghanistan almost 20 years ago with clear goals: get those who attacked us on September 11, 2001—and make sure al Qaeda could not use Afghanistan as a base from which to attack us again. We did that—a decade ago. Our mission was never supposed to be nation-building. (@POTUS, 8 August 2021)

In this case, the narrative of securitisation is used to legitimise the initial invasion of Afghanistan as a response to previous aggression against the American nation, an actor that throughout the passage is signalled by the pronouns we/us and ‘our’, thus implicitly demarcating Afghanistan as lying outside the interests of the American nation. The emphasis of this argument is on the ultimate goal of such a mission, which is stated as getting those who attacked the US, as opposed to building the Afghan nation. This strategy thus appears to be aimed at transcending the contingent situation by contextualising the withdrawal within the bigger picture of US operations and by dismissing any nation-building intervention.

A further example of transcendence as a communicative strategy is provided by Extract 2 in which, drawing on the narrative of national interest, President Biden makes it explicit that Afghanistan is no longer a priority for the US:

Extract 2

We must stay clearly focused on the fundamental national security interests of the United States. This decision about Afghanistan is not just about Afghanistan. It is about ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries. (@POTUS, 31 August 2021)

It is noteworthy that the narrative of the US as contributing to rebuilding nations seems to be at odds in Extract 1 and Extract 2; the former depicts the mission in Afghanistan as never having been intended to be a nation-building goal, while the latter justifies the withdrawal so that troops can be deployed to “remake other countries”.

The narrative of national interest was also drawn upon to justify the withdrawal as a way to avoid the dangers and costs of stationing troops in a foreign country, a scenario that Blinken described as potentially advantageous to US “strategic competitors or adversaries”:

Extract 3

There is nothing that our strategic competitors or adversaries would have liked more than for the United States to re-up a 20-year war and remain bogged down in Afghanistan for another decade. (@SecBlinken, 14 September 2021)

Similarly, transcendence strategies were adopted by the administration when addressing how US counterterrorism policies have changed. In this case, the tweets produced tended to construct arguments around the claim that the US faces greater security threats in other parts of the world than it does in Afghanistan and thus to justify how its (euphemistically labelled) “Afghanistan relocation efforts” should be mobilised where they are most needed while reassuring the public they would be ready to return when the need arose again, as in the following extract:

Extract 4

We are repositioning our resources to meet terror threats where they are now: across South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. But make no mistake: we have the capabilities to protect the homeland from any resurgent terrorist challenge emanating from Afghanistan. (@POTUS, 8 July 2021)

Here the discourse harks back not only to the securitisation narrative (via the “homeland” trope) but also to the cognate ‘war on terror’ narrative (interdiscursively signalled by the expression “terror threats”) to justify withdrawing. Through a reiteration of the premise that the US faces greater security threats in other parts of the world (topos of global threat), the argument is put forward that a military presence in Afghanistan is not as greatly required as it is in other countries and the withdrawal is thus implicitly legitimated.

Our analysis found that strategies of transcendence frequently relying on the narrative of securitisation were in some cases realised through the implicit topos of moral policing (i.e. that the US has a moral obligation to police terrorism worldwide), as exemplified by the following extracts:

Extract 5

Today, the terrorist threat is metastasized well beyond Afghanistan. Al Shabab in Somalia, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Alausa and Syria, ISIS attempting to create a caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and establishing affiliates in multiple countries in Africa and Asia. These threats warn our attention and our resources. We conduct effective counterterrorism missions against terrorist groups in multiple countries where we don’t have a permanent military presence. If necessary, we’ll do the same. (@POTUS, 17 July 2021)

Extract 6

The fundamental obligation of a President is to defend America. Not against the threats of 2001, but against the threats of 2021 and tomorrow. I do not believe the safety and security of America is enhanced by continuing to deploy thousands of American troops in Afghanistan. (@POTUS, 1 September 2021)

In Extract 5, the discourse is linguistically realised via the medical metaphor of terrorism being a cancer, which can be inferred from “the terrorist threat is metastasized”, which likens the globe to an ill body and the US to a medical agent. Through this representation, the American ‘doctor’ is portrayed as capable of moving around the globe to attend to patients as needed and arguably to legitimise leaving the field once the intended intervention has concluded.

Similarly, in Extract 6 the strategy of transcendence is sustained by narratives of global and domestic securitisation but, unlike Extract 5, which refers to a spatial dimension of the terrorist threat, it taps into a temporal dimension (via the juxtaposition from 2001 to 2021) to justify the US relocating its military operation. In other words, in the discourse of the US administration, transcendence is not only achieved by spatial transcendence (that is, contextualising the relevance/priority of US operations within wider geographically identifiable borders) but also by reference to a wider past/present historical frame. These two distinct aspects of transcendence, which were performed along distinct spatial and temporal axes, contributed to justify a shift in discourse and legitimise the US decision to withdraw its troops.

The longevity of the war was also often mentioned in the administration’s communications to justify the need to end it, and this typically occurred via the expression “America’s longest war” and by tapping into the narrative of nationhood (via the metaphorical trope of home):

Extract 7

It is time to end America’s longest war. It is time for American troops to come home from Afghanistan. (@POTUS, 14 April 2021)

Finally, strategies of transcendence were aimed at in tweets regarding the power handover from the US to the Taliban:

Extract 8

The Taliban now face a test. Can they lead their country to a safe & prosperous future where all their citizens, men & women, have the chance to reach their potential? Can Afghanistan present the beauty & power of its diverse cultures, histories, & traditions to the world?. (@US4AfghanPeace, 30 August 2021)

Extract 8 shows how the US administration constructs its diminished responsibility by representing the Taliban now in charge of a new government that the US envisages as capable of living up to Western standards.

Bolstering

Along with transcendence, bolstering was a strategy frequently deployed by the administration. Typically, this strategy revolved around promoting positive representations of the administration’s past actions and appeared to be primarily aimed at persuading its audience of the benefits of such decisions. For example, a large set of the administration’s bolstering strategies (notably, in Secretary Blinken’s communications) centred on highlighting the US’s diplomatic efforts to bring peace to the Afghan nation and to arrange evacuation routes and subsequent support for evacuees. In a set of tweets, bolstering was invoked to demonstrate how the US had consulted and collaborated with partners and NATO allies on the withdrawal process by appealing to the topos of moral credibility and through narratives of international consensus (see Extract 9) and domestic intra-institutional consensus (Extract 10):

Extract 9

I have seen no question of our credibility from our allies around the world. I’ve spoken with our NATO allies. … The fact of the matter is I have not seen that. As a matter of fact, the exact opposite I’ve gotten (Valverde, Citation2021, as cited in; Valverde, Citation2021, no page).Footnote2

Extract 10

Yesterday, @potus spoke with both President Bush and President Obama during separate calls. While we will not disclose private conversations, he wanted them both to hear from him directly about his decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan. (@PressSec, 14 April 2021)

Our data analysis also showed that bolstering was sometimes achieved by emphasising representations of the peace process as a fait accompli in a narrative that is reminiscent of those mobilised in the media and by politicians in relation to the US withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s and the USSR’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in the 1980s (see Roselle, Citation2006).

Extract 11

Following stops in Tashkent, Doha, Kabul, and Dushanbe focused on building regional consensus on #AfghanistanPeace, concluded [sic] this trip in Berlin with a US-Europe meeting of allies. There is a unique international consensus for peace, rooted in the support for a negotiated settlement, an end to violence, and rejection of any attempt to impose a military solution. Afghan leaders from all sides of the conflict should seize this opportunity and negotiate a political settlement to end their 40 year long war. If the Taliban do not choose peace, a future based on consensus and compromise, then we will stand with Afghans who strive to keep the Republic intact. (@US4AfghanPeace, 7 May 2021)

Through representations of Al Qaeda having been defeated in Afghanistan and the threat now being minimal, Biden was thus able to argue that the US military was no longer needed in Afghanistan.

In some cases, these bolstering strategies relied on the topos of numbers

(see Extract 7), while in other instances, they were intersecting with other strategies, such as transcendence and blame shifting (see below). For example, the peace process was invoked by the administration not only to justify its withdrawal (strategy of transcendence) but also to dismiss any responsibility of further involvement (strategy of blaming) based on arguments that the Afghan army was not being collaborative or proactive (see the next section for strategies of blaming).

Extract 12

We have already evacuated more than 18,000 people from Afghanistan since July—and approximately 13,000 since our military airlift began on August 14. Thousands more have been evacuated on private charter flights facilitated by the U.S. government. (@POTUS, 20 August 2021)

Moreover, strategies of bolstering were sometimes achieved through specific topoi of monitoring and accountability, whereby, for example, the US administration tended to represent itself as a competent and committed agent engaged in tracking the Taliban’s promise to safeguard the international community during the evacuation process:

Extract 13

Today, nearly 100 countries issued a joint statement on the assurances by the Taliban that all foreign nationals and any Afghan citizen with travel authorization from our countries will be allowed to safely travel outside Afghanistan. We will hold the Taliban to that commitment. (@PressSec, 29 August 2021)

Finally, our analysis showed that as part of a macro strategic approach to communication based on bolstering, the administration also frequently adopted strategies of appraising, particularly in relation to three groups: US military troops, US allies (including NATO and other US partners), and US civil servants.

Extract 14

We’re going to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with our closest partners to meet the current challenges we face in Afghanistan—just as we have for the past 20 years. We are acting in consultation and cooperation with our closest friends and fellow democracies. (@POTUS, 24 August 2021)

Unlike previous extracts where the emphasis was on the desirability of US permanence in Afghanistan and on limiting US responsibility in the conflict, in Extract 14 the strategic orientation is towards highlighting a sense of joint ownership of the current situation, a representation which is conveyed through the expression “shoulder-to-shoulder”, a trope interdiscursively related to the Bush-Blair military alliance in the wake of the 11 September attack and laden with emotional valence.

Blaming/Scapegoating

As remarked by Coombs (Citation2015, p. 142), “a scapegoating strategy seeks to shift the blame to another actor; here, the organisation is connected to the crisis but lays fault upon another entity” (see also Hansson, Citation2015). The administration’s use of this strategy was mainly focused on blaming its Afghan counterpart, namely the Afghan government, politicians, and the national army, as exemplified by the following extracts:

Extract 15

American troops cannot—and should not—be fighting and dying in a war that Afghan forces are by and large not willing to fight and die in themselves. (@POTUS, 16 August 2021)

Extract 16

We spent over a trillion dollars. We trained and equipped an Afghan military force with some 300,000 strong, incredibly well equipped. A force larger in size than the military of many of our NATO allies. We gave them every tool they could need … What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future. (@POTUS, 16 August 2021)

President Biden’s argument is aimed at legitimising the withdrawal and is based on vivid representations of the Afghan army as an inactive or incapable actor in the conflict. In Extract 15, the argument is constructed via the topos of blame and the use of the modal verbs ‘can’ and ‘should’ to not only indicate the US army’s inability to continue the fight (“cannot”) but to emphasise the desire to end its moral obligation to support the host country’s fighting (“should not”). In Extract 16, the strategy of blaming is realised in conjunction with a strategy of bolstering, the latter reliant on the topos of numbers used to highlight the US investment in the Afghan military machine vis-à-vis their alleged unwillingness to fight. These representations of an Afghan army unwilling to fight are contradicted by the fact that over the course of 20 years of war, more than 70,000 Afghan soldiers died on the battlefield compared to 2,456 US troops (USA Today, Citation2021). President Biden characterises Afghan institutions as inactive, a delegitimating strategy that allows him to justify American troops ceasing to fight, based on the logic that all military operations should constitute a joint effort.

The administration also adopted strategies of blaming in relation to former US administrations, including former President Donald Trump, whom the incumbent administration identified as one of the causes of the crisis due to his bad deal with the Taliban that led to a rapid withdrawal:

Extract 17

That’s what I inherited. That agreement was the reason the Taliban had ceased major attacks against US forces. If, in April, I had instead announced that the United States was going back — on that agreement made by the last administration — [that] the United States and allied forces would remain in Afghanistan for the foreseeable future. The Taliban would have again begun to target our forces. The status quo was not an option. (@POTUS, 8 July 2021)

President Biden’s argument in Extract 17 is based on the topos of anticipated consequences and is constructed by the speaker referring to the agreement reached by President Trump (metaphorically represented as an inheritance) involving the release of Taliban prisoners which, in Biden’s view, would have given too much leverage to the Taliban at the expense of the US army.

Mitigation

Our analysis identified a final set of strategies which were oriented toward mitigation – that is, they aimed at representing the intensity or impact of a situation less serious or hurtful by offering some extenuating arguments. Typically, these strategies were predicated on the speaker offering a reason that made negative events easier to accept in light of a specific pre-emptive or countering act undertaken by the speaker. For example, the administration adopted mitigating strategies to justify why it was necessary to withdraw, drawing on narratives of responsibility and nationhood, as in the extract below:

Extract 18

I know my decision on Afghanistan will be criticized. But I would rather take all that criticism than pass this responsibility on to yet another president. It’s the right one for our people, for the brave servicemembers who risk their lives serving our nation, and for America. (@POTUS, 16 August 2021)

In this tweet, President Biden constructs an argument for the withdrawal via the pre-emptive statement ‘I know I will be criticized’, which is then followed by a justification predicated on mitigation. Mitigating is invoked through the topos of responsible action to suggest the unsustainability of the current conflict set-up and the lessening of damage his decision would result in for the American nation (linguistically realised via the nation-centric deictic ‘our people’) and for his successor.

In a similar vein, Biden appealed to the topos of (reduced) damage and of responsible action in an emotive tweet in which he reiterated his decision to withdraw American troops from Afghan soil:

Extract 19

How many more generations of America’s daughters and sons would you have me send to fight Afghanistan’s civil war when Afghan troops will not?. (@POTUS, 17 August 2021)

In this case, the strategy of mitigation is linguistically realised via the metaphor that a nation is a family (inferred from the use of “sons” and “daughters”) and by the adoption of a rhetorical question which is often intended to solicit the audience’s approval of an argument put forward by a speaker (Kallendorf & Kallendorf, Citation1985).

In some other instances, mitigation is achieved through micro strategies of remediation in which the administration makes a claim about some adjustment or compensation to a course of events that would arguably reduce victims’ negative feelings towards the organisation for their actions (see, for example, Marcus & Goodman, Citation1991). In particular, our analysis found evidence of a number of tweets in which the Biden administration’s communications made use of a remediation strategy to emphasise how the US would support Afghans with humanitarian and financial provisions:

Extract 20

The United States remains firmly committed to continue our robust humanitarian assistance for the people of Afghanistan. We are proud to announce an additional $64 million in humanitarian assistance. (@US4AfghanPeace, 13 September 2021)

Similarly, there were micro strategies oriented towards mitigation that focused on expressing (humanitarian) concern. In these cases, the strategic communicative goal appeared to be aimed at gaining the benevolence of primary stakeholders and was focused on showcasing the administration’s moral responsibility for its actions. Whilst in most tweets produced by Biden micro strategies of concern involved demonstrating concern for the lives of Americans and offering condolences to the affected families, Khalilzad’s communication tended to deploy concern for Afghanistan and its citizens who have been drowning in the war for four decades:

Extract 21

Afghans are suffering terribly from the war. Credible reports of atrocities are emerging. The parties’ commitment to prevent civilian casualties is a start, but only a negotiated political settlement can end this senseless violence. (@US4AfghanPeace, 20 July 2021)

Discussion and conclusions

This study has provided insight into the US administration’s management of communication in relation to the American withdrawal from Afghanistan. Our analysis has identified a set of discursive strategies that the administration adopted in their Twitter communications, namely transcendence, bolstering, blaming and mitigation. Our analysis has suggested that such strategies largely served an overarching discursive shift, whereby portrayals of the war in Afghanistan as unsustainable and no longer needed by the US replaced early representations which depicted the invasion as a “mission of necessity” (Ringsmose & Børgesen, Citation2011, p. 505) in line with the Responsibility to Protect principle (United Nations, Citation2023).Footnote3 Our analysis has also suggested that, by and large, macro strategies of transcendence, bolstering, blaming and mitigation relied on a set of key strategic narratives aimed at framing events, social actors and, more widely, social reality.

Global/domestic securitisation was one of the driving narratives of our data. It construed the military operation in Afghanistan as one aimed at keeping both the world and America safe. The macro narrative of global/domestic securitisation was often associated with the ‘war on terror’ narrative, an account of events providing cognitive and emotional continuity with the 9/11 attack and justification for starting the war in the first place. However, in this case, harking back to the ‘war on terror’ narrative was deployed by the administration to legitimise redeploying the US army to other ‘terror hotbeds’ and thus to justify withdrawal from Afghan soil. This narrative also tied in with the narrative of the US as a global order policing officer, a role that the US implicitly advocated for itself when announcing troop redeployment and which constitutes the basic legitimacy not only for such operations but for one of the key functions of the state – namely, safeguarding its citizens.

Our analysis has shown that narratives of national interest and nationhood were also running through most of these tweets. This is hardly surprising, given the discursive naturalisation of the world order around nation states. Our analysis however points to how the mobilisation of national interest and strategic goals in the discourse of tweets was context-dependent, since the narrative of the Afghan war – which back in the 2001 invasion was represented as an imperative for security – was now being abandoned for one that justified the US’s withdrawal by characterising the war as detrimental to the US and a burden for the American nation. The context dependency of the national security narrative is also highlighted by the tensions between domestic protection and the Responsibility to Protect principle that was originally invoked to justify the Afghan operation and had now changed to other countries.

Our analysis has also shown how such a discursive shift was achieved via strategies of scapegoating, where the blame for the status quo and the ‘logical’ decision to leave was attributed both to previous administrations for passing down a ‘bad deal’ and to the Afghan army for its inability/unwillingness to fight alongside the US. In some cases, representations of legitimate decisions taken by the US administration were also reliant on narratives of domestic, international and intra-institutional consensus whereby the US portrayed itself as a wise actor accommodating different interests rather than imposing its will. In this sense, the narrative of responsibility (to protect) was also prominent in strategies of mitigation in which the administration portrayed itself as a moral actor striving to do the right thing for its own people and, to a lesser extent, for the Afghan population.

Our analysis has also highlighted how the discourse of the peace process as a fait accompli was often mobilised by the administration to justify the withdrawal in a way that was similar to narratives about the US withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s and the USSR’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in the 1980s. While one may welcome the end of the conflict, the narrative of Afghanistan being at peace is far from reality as the country faces unprecedented humanitarian and economic crises and severe international isolation (Amnesty International, Citation2022; UNHCR, Citation2023) in the wake of the longest war fought by the US army which has resulted in over 200,000 casualties and an estimated yearly average of 2.5 million refugees displaced by the conflict (World Bank, Citation2023).

In many respects, the findings on the use of strategic narratives tell us that legitimacy was constructed around a perceived international order of nations in which conflict is conceived as a means to restore an idealised status quo. In this sense, the language of legitimacy encompasses two distinct but interrelated dimensions: one dimension dwelling on factual, operation-oriented discourses which primarily focus on reporting evacuation logistics, diplomatic, and organisational activities; and another dimension making use of evaluation-oriented discourses aimed at justifying certain actions through explicit/implicit moral premises.

The analysis has also shown that, as the discursive mobilisation of strategic narratives is context-dependent, it allows some contradictions. For example, we have shown how, in the case of the narrative that the US is intervening to rebuild nations, the American administration adopted statements which directly opposed each other at various times. Rather than regarding these as incongruencies, in our view, the strategic deployment of the same narrative of securitisation served functionally to sanction the legitimacy of a discursive shift from invasion to withdrawal as distinct military goals in two different contexts. In this sense, legitimation and delegitimation strategies often co-occured as part and parcel of the same narrative; however, the topoi invoked (that is, the circumstantial premises that warrant an argument) relied on different sets of external circumstances.

Further considerations can be given to the extent to which communication was used to reflect a pre-planned strategy rather than driving it, a question which, in turn, goes to the core debate on the nature of language (Wittgenstein, Citation2001 [1953]). Following the social constructivist approach that we have taken to our study, we must consider the mutually constitutive nature of language and social activities in which one influences the other, thus recognising the power of language beyond the argumentative validity of certain statements to encompass both the illocutionary and perlocutionary forces of an utterance (Searle, Citation1969). Consequently, while linguistic narratives can be seen as instrumentally supporting the communication of strategy, they also become part of the strategy itself as they reiterate the socially accepted beliefs they encode. Although we cannot speculate on the extent to which such strategies were effective (as our study did not assess the persuasiveness of the communication or any effects on the intended audience), we nevertheless have highlighted how strategic messages were arguably driven rhetorically by the intended audience and the contexts of production. Moreover, we have pointed out the cognitive implications of certain language choices, emphasising how, from a critical perspective, the rhetoric adopted by the US government in its communication must be seen through the lens of external events, including the critical voices of international stakeholders, such as the media and politicians.

In this regard, we would welcome future studies that address these aspects – namely, correlations between the US administration’s discursive shifts and external events/discourses. Similarly, we would encourage research that looks at audience responses to such communications and at the effectiveness of the strategies adopted.

Our final considerations relate to the use of Twitter for institutional communication. On the one hand, our analysis has suggested that the US administration leveraged innovative and dynamic forms of communication such as Twitter for rapid information dissemination (Sigala, Citation2011) and because such platforms have been regarded by the American public as a reliable source of news and information (Research, Citation2021). This arguably illustrates the administration’s keen understanding of its target audience and the effective medium to align its communication strategy with a patriotic rhetoric that would resonate with American public sentiment.

On the other hand, findings on the strategies adopted by the US administration largely corroborate previous studies on the handling of crisis communication as, although they performed their communications on a digital platform like Twitter, speakers resorted to traditional communicative patterns by invoking transcendence, bolstering, blaming and mitigation, and did so from established rhetorical stances. Therefore, while we share the broad academic consensus that social media platforms have increasingly been adopted for diplomatic purposes (Bjola & Holmes, Citation2015) and that they have had an overarching impact on the performance of communication (Hedling & Bremberg, Citation2021), we are more sceptical of claims that such platforms are conducive to dialogical communicative patterns with stakeholders (Liu & Shrum, Citation2002; Ott & Theunissen, Citation2015; Strauß et al., Citation2015). The hypertextual nature of social media and some of their functions, such as reposting, clearly mean that messages can be reverberated effectively among users at speed and at scale. The importance of Twitter is demonstrated by the fact that it was quickly adopted by the Taliban to mobilise participation in the insurgency and to disseminate information about the conflict (Bernatis, Citation2014; Drissel, Citation2015). However, we did not see a straightforward dialogical formula in the mobilisation of Twitter (Sundstrom & Levenshus, Citation2017) in the case of the American administration due to a power asymmetry between actors, namely the government and the public. Therefore, although social media like Twitter may allow bottom-up and peer-to-peer communication flows of information which could potentially enable a networked civic debate (Cull, Citation2013), the typical use that has been made of Twitter by the US government tends to replicate a traditional asymmetric top-down flow. Indeed, even when a two-way flow of information has been generated by public communication on social media (manifested, for example, through audiences’ comments and opinions), the extent to which this has resulted in more than a set of ‘metrifiable’ high impressions and may in fact have contributed to shifts in an overall policy-making agenda remains debatable (Bjola & Holmes, Citation2015).

So, despite the bottom-up potential, contextual and power dynamics are still key in how strategic communication unfolds in the pseudo-sociality and rhetoric of digital discourses (Thurlow, Citation2013), a view which is supported in our data by the fact that no official responses ensued from audience comments. This has clear implications for governments/administrations and for practitioners choosing to communicate on Twitter about their military operations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 At the time this study was carried out and the article was written, the platform was officially known as Twitter. Following Elon Musk’s acquisition, the platform was rebranded as X in July 2023. For consistency, in this article we have kept our reference to the platform in its original name.

2 This statement is attributed by Valverde (Citation2021) to Biden as part of the President’s speech delivered on 20 August 21; however, it does not appear in the transcript of videos posted on the @POTUS account.

3 In the international law system, the R2P principle holds sovereign states accountable to protect their own citizens. If they fail to uphold this principle, the obligation to protect falls on the international community, thus justifying humanitarian intervention through force.

References

- Amnesty International. (2022). Afghanistan report. https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/asia-and-the-pacific/south-asia/afghanistan/report-afghanistan/

- Arquilla, J., & Ronfeldt, D. (2001). Networks and Netwars: The future of terror, crime, and militancy. Rand Corporation.

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Clarendon Press.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. Penguin Books.

- Bernatis, V. (2014). The Taliban and twitter: Tactical reporting and strategic messaging. Perspectives on Terrorism, 8(6), 25–35.

- Bjola, C., & Holmes, M. (2015). Digital diplomacy: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Boyd, D., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on twitter. 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, USA (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2010.412

- Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Crawford, K., & Shaw, F. (2012). Crisis communication on twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland floods-research report.

- Coombs, W. T. (2006). The protective powers of crisis response strategies: Managing reputational assets during a crisis. Journal of Promotion Management, 12(3–4), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1300/J057v12n03_13

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organisation reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

- Coombs, W. T. (2010). Parameters for crisis communication. In W. T. Coombs & S. J. Holladay (Eds.), The handbook of crisis communication (pp. 17–53). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Coombs, W. T. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.10.003

- Coombs, W. T. (2018). Crisis communication. In R. L. Heath & W. Johansen W (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of strategic communication (pp. 436–448). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (1996). Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study in crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(4), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr0804_04

- Cull, N. J. (2013). The long road to public diplomacy 2.0: The internet in US public diplomacy. International Studies Review, 15(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/misr.12026

- Demasi, M. A., Burke, S., & Tileagă, C. (Eds.). (2021). Political communication: Discursive perspectives. Springer Nature.

- Drissel, D. (2015). Reframing the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan: New communication and mobilization strategies for the Twitter generation. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 7(2), 97–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2014.986496

- Eichenberg, R. C. (2005). Victory has many friends: U.S. public opinion and the use of military force, 1981–2005. International Security, 33(1), 140–177. https://doi.org/10.1162/0162288054894616

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Ericson, R. V. (1998). How journalists visualize fact. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 560(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716298560001007

- Falkheimer, J. (2021). Legitimacy strategies and crisis communication. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1567

- Farwell, J. (2012). Persuasion and power: The art of strategic communication. Georgetown University Press.

- Forchtner, B., & Özvatan, O. (2022). De/Legitimising Europe through the performance of crises. The far-right alternative for Germany on ‘climate hysteria’ and ‘corona hysteria’. Journal of Language and Politics, 21(2), 208–232. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.21064.for

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language. Pantheon Books.

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2022). New theoretical directions and frameworks in social media and crisis communication research. In L. Austin & Y. Jin (Eds.), Social media and crisis communication (2nd ed, pp. 373–385). Routledge.

- Friedland, L. A., Hove, T., & Rojas, H. (2006). The networked public sphere. Javnost – the Public, 13(4), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2006.11008922

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hall, S. (2013). The work of representations. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 27–47). Sage.

- Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D. R., van Ruler, B., Vercic, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244

- Hansson, S. (2015). Discursive strategies of blame avoidance in government: A framework for analysis. Discourse & Society, 26(3), 297–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926514564736

- Hearit, K. M. (1997). On the use of transcendence as an apologia strategy: The case of Johnson controls and its fetal protection policy. Public Relations Review, 23(3), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90033-3

- Hedling, E., & Bremberg, N. (2021). Practice approaches to the digital transformations of diplomacy: Toward a new research agenda. International Studies Review, 23(4), 1595–1618. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab027

- Holmström, S., Falkheimer, J., & Gade Nielsen, A. (2009). Legitimacy and strategic communication in globalization: The cartoon crisis and other legitimacy conflicts. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 4(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180903415780

- Holtzhausen, D. R., & Zerfass, A. (2015). Strategic communication: Opportunities and challenges of the research area. In D. R. Holtzhausen & A. Zerfass (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of strategic communication (pp. 3–17). Routledge.

- Jentleson, B. W. (1992). The pretty prudent public: Post post-Vietnam American opinion on the use of military force. International Studies Quarterly, 36(1), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600916

- Kallendorf, C., & Kallendorf, C. (1985). The figures of speech, ethos, and Aristotle: Notes toward a rhetoric of business communication. International Journal of Business Communication, 22(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194368502200102

- Kryger Aggerholm, H., & Thomsen, C. (2016). Legitimation as a particular mode of strategic communication in the public sector. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1176570

- Liu, Y., & Shrum, L. J. (2002). What is interactivity and is it always such a good thing? Implications of definition, person, and situation for the influence of interactivity on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 31(4), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673685

- Marcus, A. A., & Goodman, R. S. (1991). Victims and shareholders: The dilemmas of presenting corporate policy during a crisis. Academy of Management Journal, 34(2), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/256443

- Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. R. (2005). The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Miskimmon, A., O’Loughlin, B., & Roselle, L. (2013). Strategic narratives: Communication power and the new world order. Routledge.

- Ott, L., & Theunissen, P. (2015). Reputations at risk: Engagement during social media crises. Public Relations Review, 41(1), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.015

- Paul, C. (2011). Strategic communication: Origins, concepts, and current debates. Praeger.

- Peter, F. (2008). Democratic legitimacy. Routledge.

- Record, J. (1993). Hollow victory: A contrary view of the gulf war. Brassey’s.

- Research, P. (2021). News Consumption Across Social Media in 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/09/20/news-consumption-across-social-media-in-2021/

- Ringsmose, J., & Børgesen, B. K. (2011). Shaping public attitudes towards the deployment of military power: NATO, Afghanistan and the use of strategic narratives. European Security, 20(4), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2011.617368

- Roselle, L. (2006). Media and the politics of failure: Great powers, communication strategies, and military defeats. Springer.

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press.

- Sigala, M. (2011). Social media and crisis management in tourism: Applications and implications for research. Information Technology & Tourism, 13(4), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830512X13364362859812

- Strauß, N., Kruikemeier, S., van der Meulen, H., & van Noort, G. (2015). Digital diplomacy in GCC countries: Strategic communication of Western embassies on twitter. Government Information Quarterly, 32(4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.08.001

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Sundstrom, B., & Levenshus, A. B. (2017). The art of engagement: Dialogic strategies on Twitter. Journal of Communication Management, 21(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-07-2015-0057

- Su, S., & Xu, M. (2015). Twitplomacy: Social media as a new platform for development of public diplomacy. International Journal of E-Politics, 6(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEP.2015010102

- Svenbro, M., & Wester, M. (2023). Examining legitimacy in government agencies’ crisis communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 17(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2022.2127358

- Tench, R., Meng, J., & Moreno, A. (Eds.). (2022). Strategic communication in a global crisis: National and international responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Routledge.

- Thurlow, C. (2013). Fakebook: Synthetic media, pseudo-sociality, and the rhetorics of web 2.0. In D. Tannen & A. M. Trester (Eds.), Discourse 2.0: Language and new media (pp. 225–250). Georgetown University Press.

- UNHCR. (2023). Afghanistan situation. https://reporting.unhcr.org/afghanistan

- United Nations. (2023). Responsibility to Protect. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/about-responsibility-to-protect.shtml

- USA Today. (2021). The People Behind the Numbers in Afghanistan. https://www.usatoday.com/pages/interactives/graphics/afghanistan-in-memoriam/

- Vaara, E., & Monin, P. (2010). A recursive perspective on discursive legitimation and organizational action in mergers and acquisitions. Organization Science, 21(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0394

- Valverde, M. (2021). Fact-Checking Joe Biden on U.S. Credibility as Military Withdraws from Afghanistan. https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2021/aug/26/joe-biden/fact-checking-joe-biden-us-credibility-military-withdrawal

- van Dijk, T. A. (2015). Critical discourse analysis. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (2nd ed, pp. 466–485). Wiley.

- van Leeuwen, T., & Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: A discourse-historical perspective. Discourse Studies, 1(1), 83–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445699001001005

- Vyklický, V., & Divišová, V. (2021). Military perspective on strategic communications as the “new kid on the block”: Narrating the Czech military deployment in Afghanistan and the Baltic states. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 15(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2021.1906681

- Wittgenstein, L. (2001 [1953]). Philosophical investigations. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (2nd ed, pp. 1–33). Sage.

- World Bank. (2023). World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG.OR?end=2021&locations=AF&start=2001

- Zappettini, F., & Bennett, S. (2022). Special issue on ‘reimagining Europe and its (dis)integration? (De)legitimising the EU’s project at times of crisis’. Journal of Language and Politics, 21(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.21075.zap

- Zappettini, F., & Krzyżanowski, M. (2021). Brexit as a social and political crisis: Discourses in media and politics. Routledge.

- Zappettini, F., & Maccaferri, M. (2021). Euroscepticism between populism and technocracy: The case of Italian Lega and Movimento 5 Stelle. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 17(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v17i2.1184