ABSTRACT

This study investigates how the presence and type of an observer influence individual waste sorting intentions. We explore the role of impression management and pro-environmental attitude as mediating and moderating factor, respectively. Results indicate that individuals are more inclined to sort waste thoroughly in the presence of another person, particularly an acquaintance or a stranger, compared to CCTV or being alone. This effect is amplified among those with weaker pro-environmental attitude. Conversely, individuals with stronger pro-environmental attitude consistently exhibit high waste sorting intention irrespective of the observer’s presence. The results suggest that placing waste sorting facilities in public areas may be more effective than installing CCTV cameras, especially among those with lower pro-environmental attitudes.

Recently, the global environment has been deteriorating at an alarming pace, largely due to a huge amount of carbon dioxide emissions, plastic production, and waste disposal. In particular, the habit of plastic consumption is considered as a major contributor to serious environmental pollution (Helen et al., Citation2022). The global production of plastic products is significantly increasing every year, reaching 390.7 million metric tons in 2021 (Statista Research Department, Citation2023), while the recycling rate of plastic waste throughout the world is only 9% (OECD, Citation2022). It is urgent to increase the recycling rate of plastic waste to mitigate environmental damage.

Many empirical studies have indicated that people do not actually take concrete action to protect the Earth’s environment (Gifford, Citation2011; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002; Maryam & Tye, Citation2020; O’Riordan, Citation2009; Szerszynski, Citation2007), while more than 90% of people are generally aware of the seriousness of environmental pollution and have a positive attitude toward pro-environmental behavior (Geng et al., Citation2017; KEITI, Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2020). This raises the question of why people’s pro-environmental attitude does not necessarily translate into pro-environmental behavior.

J. H. Kim (Citation2013) highlighted the reasons why awareness of environmental protection does not always translate into pro-environmental behavior, despite the desirability of social values. First, people tend to view themselves as not directly related to environmental pollution policies, leading to a lack of perceived relevance for pro-environmental behavior. Second, people may be unwilling to accept the potential negative consequences of environmental pollution in the future. Finally, people may believe that their pro-environmental behavior is socially ineffective. To protect environment from pollution, it is essential to foster public interest and active participation in government policies related to waste sorting.

Previous studies have investigated the factors that influence consumers’ pro-environmental attitude and behavior (Dixit & Badgaiyan, Citation2016; Fielding & Hornsey, Citation2016; Gifford & Nilsson, Citation2014; X. Li et al., Citation2019; Liu & Bai, Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2016). Generally, the variables uncovered by these studies are divided into personal, psychological, and social factors (Gifford & Nilsson, Citation2014; X. Li et al., Citation2019). Personal factors mainly include demographic variables such as gender, age, educational level, marital status, and residential area. Psychological factors deal with past experiences, personal values, and a sense of responsibility. As for social factors, social sanctions, norms, and cultural or ethnic variations have been suggested.

Although a vast quantity of prior studies has been conducted to identify the variables affecting pro-environmental behavior and attitude, this study specifically focuses on the social factors. Its purpose is to analyze the specific effect of an observer’s presence in a waste sorting place, unlike much previous literature emphasizing factors such as social sanctions and norms (Saracevic & Schlegelmilch, Citation2021; Silvi & Padilla, Citation2021; Vesely & Klöckner, Citation2018). Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to verify whether an individual’s waste sorting intention is affected by the social contexts in which an observer is present and the type of observer. These assumptions will be examined by Mere Presence Effect and Social Impact Theory. Additionally, this research aims to ascertain the psychological mechanism underlying the impact of an observer’s presence and type on personal waste sorting intention.

The mere presence effect suggests that the presence of others can influence individual behavior, even without direct interaction with them (Argo et al., Citation2005; Kang et al., Citation2023; Roos et al., Citation2023; Zajonc, Citation1965; Zajonc & Sales, Citation1965). Moreover, social impact theory posits that the influence of others varies according to social distance and increases individual arousal level or induces a specific drive for satisfaction (Cottrell et al., Citation1968; Evans, Citation2023; Latané, Citation1981). Based on the theories, we expect that the presence of observer and the three types of observer (i.e., acquaintance, strangers, and CCTV) affect consumers’ waste sorting intention.

Furthermore, this study aims to explore the potential moderating role of pro-environmental attitude on the relationship between an observer’s social influence and waste sorting intention, as well as the mediating effect of impression management motivation.

Theoretical development

Mere presence effect

The influence of others on individual behavior can be easily observed in phenomenon such as mimetic activity, compliance, competition, helping behavior, and conformity (Etienne & Charton, Citation2023; Fabrigar & Norris, Citation2012; Markus, Citation1978; S. Park et al., Citation2017). In other words, the social situation with the presence of others affects individual behavior in any way. In this regard, the mere presence effect was insisted by Zajonc (Citation1965) mentioning that ‘Even if others do not directly instruct or control an individual, their presence itself can sufficiently exert influence on the person’. This argument is germane to Social Facilitation Theory that was firstly identified by Triplett (Citation1898).

The social facilitation theory is also referred to as ‘an audience effect’, which explicates that the results of task performance vary according to the conditions in which others exist or not when a performer performs a specific task. Specifically, the performer shows improved performance in the task of high familiarity (e.g., easy tasks) when others exist. In contrast, the performer shows rather decreased performance in the task of low familiarity (e.g., difficult task) under the same condition (Charles et al., Citation2010; Hamilton & Lind, Citation2016; Monterio et al., Citation2023).

According to Yerkes and Dodson’s (Citation1908), there is a close relationship between a performer’s arousal level and the level of performance. If the arousal level is too high, it rather hinders the performance of difficult task. However, in contrast, the performance of easy task is enhanced and sustained at a high level. Therefore, considering Yerkes-Dodson’s Law along with Zajonc’s (Citation1965) mere presence effect, familiar pro-environmental behavior, such as correctly sorting plastic waste, is expected to increase due to the arousal caused by the presence of others.

In the research area of human and consumer behavior, empirical literatures have shown that the presence of others forces people to follow social norms (Childers & Rao, Citation1992; Goldberg, Citation2023; Lane et al., Citation2023; D. Rook & Fisher, Citation1995) or activates their motivation to shape a good impression in a social relation (Leary & Kowalski, Citation1990; McFarland et al., Citation2023; Pernelet & Brennan, Citation2023; Schlenker & Weigold, Citation1992). In line with the studies, consumers may impulsively buy a product due to the presence of others (Beatty & Ferrell, Citation1998; Wang et al., Citation2020), and may be encouraged to choose expensive brands (Argo et al., Citation2005; Haque et al., Citation2023).

In this respect, it will be worth investigating whether an observer’s mere presence is an appropriate factor driving individual pro-environmental behavior. In fact, a few studies have confirmed that people are likely to exhibit pro-environmental behavior, such as purchasing environmentally friendly products even at a higher price, in the public area (Griskevicius et al., Citation2010). However, it is challenging to find specific studies that have examined whether there are differences in personal waste sorting behavior and intention under social situations where an observer is simply present or not. Therefore, based on the mere presence effect, this study firstly aims to verify whether there is a difference in the intention to sort plastic waste with deliberation between the conditions of an observer’s presence and being alone in waste sorting place.

In Korean, people usually dispose of plastic waste alone and they must detach packing materials, such as vinyl labels, from them. If people have even a little interest in environmental pollution and eco-friendly behavior, the waste sorting task is easy to do in everyday life without requiring much time and effort. In other words, waste separation is not a difficult mission requiring increased arousal. However, in contrast with a condition in which a person disposes of the waste alone, a condition in which an observer exists can cause the person’s arousal and may induce waste sorting intention to change. This is the reason why H1 was set in the current study. We intend to identify whether people express an increased intention to sort waste by detaching vinyl labels from plastic bottles when an observer is present in waste sorting place.

H1.

The presence of an observer is more likely to affect waste sorting intention compared to being alone.

Social impact theory

According to a study by Zajonc (Citation1965), the presence of anyone evokes physical or psychological arousal resulting in mere presence effect. The physical or psychological arousal is also closely related to the generation of emotions, such as positive or negative moods (Hazlett-Stevens & Fruzzetti, Citation2021; James, Citation2007; D. W. Rook & Gardner, Citation1993), conformity to social norms (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1974, Citation1975; Hatcher et al., Citation2016), and the motivation for impression management (Belk, Citation1988; Huberman et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2019). As a result, people may behave differently depending on whether there is one or more persons around them, and who is the person in presence (Benenson et al., Citation2013; Perez-Vega et al., Citation2016; D. W. Rook, Citation1987).

Social Impact Theory (SIT) suggests that the influence of social circumstance on a person depends on the size, strength, and immediacy of the source (Latané, Citation1981). The size of source refers to the number of others, and the strength of source implies gender, age, physical characteristics, and intellectual level. The immediacy of the source means psychological, social, and physical distance from me. In other words, SIT describes that individual behavior, belief, and attitude are changed by the characteristics of others (Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004; Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998; Kwahk & Ge, Citation2012).

In this study, we focused on the immediacy factor proposed by SIT, regarding consumers’ waste sorting intention which might be changed by social distance between an observer and the person. Specifically, it is anticipated that people are more likely to show increased waste sorting intention when the social distance with an observer is closer. As revealed by a vast body of research in various fields, individuals with close relationships including friends and family members can exert significant influence on each other’s behavior and thoughts compared to stranger (Hu et al., Citation2023; Kang et al., Citation2023; Lalot & Abrams, Citation2023). This is often achieved by motivating individuals to form a positive impression, which ultimately contributes to strengthening the relationship (Filimonau et al., Citation2023).

Likewise, the social closeness effect has been confirmed in various research field (Batolas et al., Citation2023; Feng et al., Citation2022; Uhm et al., Citation2022), and the components of SIT have been examined by many prior studies in the fields of organizational and social psychology (Latané & Wolf, Citation1981; Montag et al., Citation2021; Shojaati & Osgood, Citation2023). However, it is difficult to find the research investigating the effect of social immediacy with others in the area of public pro-environmental behavior. Thus, the second objective of this study is to examine the differences in personal waste sorting intention based on the level of social closeness with an observer. The type of observer is classified into three types; acquaintance, stranger, and CCTV.

Among these three types of observer, ‘acquaintance’ specifically refers to someone who a person knows either superficially or well. In other words, this observer type includes people simply known to reside in the same apartment or residential complex. While encountering family or friends at waste disposal facilities in Korea is infrequent, meetings with people living in same area are commonplace. Hence, ‘acquaintance’ has been classified as a distinct observer type compared to ‘stranger’, which denotes a person who has never been met.

Additionally, stranger and CCTV both play roles in observing a person’s behavior and are expected to create different social distances compared to acquaintance because they are not deeply involved in an individual’s daily life. However, they possess a fundamental conceptual difference. Unlike stranger, who is directly perceived as a human presence, CCTV camera is not. Nevertheless, CCTV is also categorized in the spectrum of observer because when people perceive the presence of CCTV, they consider the situation in which someone is monitoring oneself (Matczak et al., Citation2023; Mathur & Sood, Citation2023; Seifi et al., Citation2023). Moreover, there are many theoretical studies that have demonstrated the observer effect of CCTV (Gerell, Citation2021; Piza et al., Citation2019; Thomas et al., Citation2022).

Therefore, the distinction holds particular significance when considering waste sorting practices In Korea, where CCTV is commonly deployed in waste separation facilities. This prompted us to conduct further analysis to differentiate between human observation and CCTV surveillance, especially in terms of their impact on personal waste sorting intention. It can be assumed that the closer the social relationship is, the higher the pro-environmental behavior intention is.

H2.

Waste sorting intention is likely to be highest in the presence of acquaintance, followed by stranger, CCTV, and being alone.

Pro-environmental attitude

The causes of human behavior are highly complicated and multifaceted. A lot of researchers have made significant efforts to explain why people initiate or restrain a certain behavior. The researchers pointed out that motivation is a driving force to trigger or sustain an individual’s actions, and it stems from personal belief and attitude about a particular event (Begley, Citation2004; Preissner et al., Citation2022; Schwartz, Citation1992). Therefore, investigating individual internal factors, such as moral belief or attitude, is crucial to understand why people perform ethical behavior including pro-environmental behavior (Nugroho et al., Citation2023; Tian et al., Citation2019; Wyss et al., Citation2022).

Among the internal factors, attitude traditionally refers to an individual’s stable and consistent mental or emotional state (Allport, Citation1935). Attitude is also expressed in a consistent disposition to favorably or unfavorably respond to a specific object (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Thus, while there is no uniform definition of attitude toward the environment (Härtel et al., Citation2023), pro-environmental attitude could be defined as an individual’s interest in environmental issues, which guides the person to act pro-environmental behavior in a certain direction.

According to one study, an individual with high pro-environmental attitude is more likely to engage in pro-environmental consumption behavior (Bao et al., Citation2019). The result of prior study shows that pro-environmental attitude is on a par with pro-environmental behavior, and it is related to the habit of purchasing, using, and disposal of eco-friendly products (Hamzah & Tanwir, Citation2021; Martino et al., Citation2019; S. H. Park & Oh, Citation2014). The fact that there is a direct relationship between pro-environmental attitude and behavior in the public and social fields was also confirmed (DeVille et al., Citation2021; Stern, Citation2000). All these studies indicate that consumers with a positive viewpoint about environmental conservation tend to carry out actual pro-environmental behavior.

However, the problem is that a person with low pro-environmental attitude does not actively take pro-environmental actions. While numerous factors, such as restrictions of circumstances including political regulations (ElHaffar et al., Citation2020; Wyss et al., Citation2022) and cost efficiency (Farjam et al., Citation2019; Naguyen et al., Citation2018), have been proposed to explain why a pro-environmental attitude may not always translate into concrete actions, it is undeniable that there exists a strong correlation between pro-environmental attitude and behavior (Blankenberg & Alhusen, Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2022). As a solution to this problem, the presence of observer could be one way to promote pro-environmental behavior in a person with low pro-environmental attitude.

It means that the effect of observer presence on pro-environmental behavior may not be apparent among people with high pro-environmental attitude. This is because the person with high pro-environmental attitude is likely to practice pro-environmental behavior regardless of external factors (Gholamzadehmir et al., Citation2019; Thian et al., Citation2019; Wilkie & Trotter, Citation2022), including the presence and the type of observer. In short, it is expected that the impact of the mere presence and the type of observer on pro-environmental behavior will be stronger for people with low pro-environmental attitude than people with high pro-environmental attitude. Therefore, the following H3 was set to figure out whether the effect of the mere presence and the type of observer on pro-environmental behavior is controlled by pro-environmental attitude.

H3.

The effect of an observer’s presence and type (acquaintance, stranger, CCTV) on waste sorting intention is moderated by pro-environmental attitude.

Impression management motivation

Probing what a person pursues in social interaction with others is crucial to comprehend the person’s social behavior, particularly, in the area of ethical behavior. Indeed, many empirical studies have been conducted to figure out why people engage in pro-social behavior in social interaction situations. As a result, impression management was suggested for the one of the reasons (Al-Shatti et al., Citation2022; Leary, Citation2019).

Impression management is defined as an action in which an individual attempts to influence others’ perception in order to give a positive image (Goffman, Citation1959; Wayne & Liden, Citation1995). According to previous studies, an individual’s good impression is formed by performing socially desirable behaviors (Gardner & Martinko, Citation1988; Grant & Mayer, Citation2009; Sassenrath, Citation2020; Schlenker, Citation1980; Schlenker & Britt, Citation1999). The results of previous studies imply that human moral behavior is closely related to the motivation of impression management.

In this respect, we assume that the presence of an observer would increase the probability of waste sorting intention because the motivation of impression management might have been evoked. Additionally, it is expected that the closer the social distance with an observer is, the higher the waste sorting intention is, because the level and the tactics of impression management may vary in accordance with social closeness (YuSheng & Ibrahim, Citation2020). Therefore, this study aims to analyze the mediating effect of impression management on the waste sorting intention which might be affected by observer type.

H4.

The effect of observer type (acquaintance, stranger, CCTV) on waste sorting intention is mediated by impression management.

Method

Research model and situation setting

The purpose of current study is to verify the impact of an observer’s presence and type on waste sorting intention, considering the moderating role of pro-environmental attitude and the mediating effect of impression management. The overall overview of this study can be confirmed through the research model (see ).

The basic situation was divided into two conditions, without and with an observer. The condition with an observer was subdivided into three types based on social distance: acquaintance, stranger, and CCTV. Taking into account the typical waste sorting practices in Korea, where waste sorting is often done individually and CCTV is commonly installed in waste sorting areas, it will be meaningful to differentiate between a human observer and CCTV. Each type of scenario explaining the specific waste sorting situation was inserted into the questionnaire to help respondents’ understanding (see ).

The scenarios in each situation are fundamentally the same, depicting the scene where respondents are about to dispose of recyclable waste collected at home. However, in the waste sorting facility, the presentation of each situation varies across four conditions: ‘You are alone’, ‘You are with an acquaintance’, ‘You are with a stranger’, and ‘CCTV camera is installed’. These scenarios portray moments when respondents realize that vinyl labels are still attached to plastic bottles without having separated them. The respondents were randomly assigned to one of the four scenarios and asked to answer a series of questions. Specifically, 164 participants were allocated to the condition of being alone, while 100 participants each were assigned the conditions of acquaintance, stranger, and CCTV.

Data collection

This study was conducted in South Korea, and Gpower 3.1 program was used to determine an appropriate sample size. The required sample size suggested 400 participants with an effect size of .25 and a confidence level of .95. From April to May 2023, two researchers and four assistants collected data using both an online Google survey form and on-site surveys. Although 470 citizens participated voluntarily without compensation, 6 questionnaires were excluded due to respondents either leaving multiple questions unanswered or providing inconsistent responses within a single number, indicating potential insincerity. In total, 464 valid questionnaires were adopted and the statistical program SPSS 26 was employed to analyze the collected data. The sample had an average age of 24.43 years (SD = 7.736), consisting of 174 men (37.5%) and 290 women (62.5%).

Measures

Pro-environmental attitude has been measured using various scales in previous studies, such as enjoyment of nature, support for interventionist conservation policies and environmental activism (Milfont & Duckitt, Citation2010). To measure this attitude in the current study, we focused on respondents’ attitude toward environmental concerns and recycling-related policies. The pro-environmental attitude measurement scale used in this research was constructed by selecting four items based on indicators proposed by Van Liere and Dunlap (Citation1981), Klineberg et al. (Citation1998), and Milfont and Duckitt (Citation2010).

The four items used were: ‘I seriously consider the environmental impact of the use of disposable products’, ‘I am very interested in the issues related to environmental pollution’, ‘I usually think about how my behavior affects environmental problem’, and ‘I carefully watch news about environmental pollution’. All the items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and the scale showed reasonable reliability, with a Cronbach’s coefficient of .896.

This research intended to employ the widely used scale of impression management designed by Bolino and Turnley (Citation1999), which is based on the taxonomy identified by Jones et al. (Citation1982). However, this scale has been refined by numerous researchers and typically measures impression management motivation in the situational contexts of organizations or companies. For this study, we selected and modified a total of eight items from the impression management scale based on studies by Bolino et al. (Citation2008) and Van Iddekinge et al. (Citation2007).

The eight items on the impression management scale used in this study were: ‘I want to be considered as a good person by others’, ‘I usually try to give a good impression to others’, ‘I do not want to be seen negatively by others’, ‘I try not to give a bad impression to others’, ‘When I am with other people, I care about whether they like me or not’, ‘I want to appear good to others’, ‘In interpersonal situations, I am usually aware of the other person’s thought’, and ‘I tend to act in accordance with the other person’s thought’. All the items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale and the Cronbach’s coefficient for the impression management scale was .908.

The scale used to measure waste sorting intention in this study was composed of four items that were designed to reflect the situational context of this study. These four items were: ‘I am willing to remove vinyl labels from plastic bottles’, ‘I intend to separate plastic bottles by detaching vinyl labels’, ‘I am motivated to sort plastic waste more thoroughly’, and ‘I do not think it is necessary to remove vinyl labels from plastic bottles’. All the items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale and the measurement scale demonstrated reasonable reliability, with a Cronbach’s coefficient of .860.

Finally, to confirm the discriminant validity of the three types of observer, six items were used to assess psychosocial distance. The items were : ‘When I act, I tend to be aware of the presence of the acquaintance around me’, ‘When I act, I tend to be aware of the stranger’s presence around me’, ‘When I act, I tend to be aware of the CCTV’s presence around me’, ‘When I act, I tend to consider the reaction of the acquaintance around me’, ‘When I act, I tend to consider the reaction of stranger around me’, and ‘When I act, I tend to consider the situation in which CCTV monitors me’. All the items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale and the measurement scale demonstrated reasonable reliability, with a Cronbach’s coefficient of .824.

The survey participants initially responded to questions assessing the perceived psychosocial distance, intended to verify the discriminant validity of the three observer types. Subsequently, they answered questions regarding their pro-environmental attitudes and impression management motives. Finally, after the presentation of the specific scenario where they were randomly assigned among four situational conditions, they responded to questions concerning their intention for waste sorting (see Appendices).

Manipulation check on psychosocial distance

As a result of conducting a manipulative check on the distinction of observer types, the result of the average analysis showed that the psychosocial distance according to the type of observer appeared higher in the following order: acquaintance (M = 5.44, SD = 1.13), stranger (M = 4.55, SD = 1.06), and CCTV (M = 3.81, SD = 1.26). Bonferroni post-hoc tests confirmed the statistical significance of the differences in means between acquaintance and stranger with a .886 mean difference (p < .001), and between stranger and CCTV with a .774 mean difference (p < .01).

Results

Descriptive statistics for waste sorting intention

Prior to hypothesis verification, descriptive analysis was conducted to check for the mean values of waste sorting intention under the four conditions. The mean value of waste sorting intention under the condition of being alone was 5.12 (SD = 1.15, N = 164), and observer presence was 5.47 (SD = 1.16, N = 300). Specifically, the mean value of waste sorting intention under the condition of acquaintance was 5.70 (SD = 1.07, N = 100), under the stranger condition was 5.52 (SD = 1.12, N = 100), and under CCTV condition was 5.17 (SD = 1.27, N = 100).

Hypothesis verification

Impact of observer’s presence and type

To assess the statistical significance of the mean difference in waste sorting intentions based on an observer’s presence, T-test was conducted. Conditions were categorized into two groups: presence of an observer versus being alone. The results indicated a statistically significant difference in waste sorting intentions between these two conditions (Mean Difference = .350, t = 2.696, p < .001).

Additionally, one-way ANOVA and post-hoc tests were performed. The results showed that the mean difference in waste sorting intention among the four conditions was statistically significant within the 95% confidence interval (CI), F(3, 460) = 6.184, p < .001, η2=.039.

As shown in , the results of Bonferroni’s test indicated that waste sorting intention under the condition of acquaintance was significantly higher than the condition of being alone (MD = .580, p < .01), and compared to the condition of CCTV (MD = .530, p < .01). The intention under the condition of stranger was also significantly higher than the condition of being alone (MD = .399, p < .05), and compared to the condition of CCTV (MD = .349, p < .05). However, the difference in waste sorting intention between the conditions of being alone and CCTV was not significant (MD=−.050, p > .05). Likewise, there was no statistically significant difference in waste sorting intention between the conditions of acquaintance and stranger (MD = .181, p > .05).

Table 1. Results of post-hoc tests on one-way ANOVA analysis.

Moderating role of pro-environmental attitude

For the next step, we further categorized the pro-environmental attitude variable into high and low levels based on the mean value. Then, two-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate whether the impact of an observer’s presence and type on waste sorting intention varies depending on personal pro-environmental attitude. The results indicated that the type of observer and pro-environmental attitude had an interaction effect on waste sorting intention, F(3, 455) = 2.992, p < .05, η2 = .019. As a result of simple main effect analysis, it was confirmed that waste sorting intention was influenced by pro-environmental attitude, F(1, 455) = 50.732, p < .001, η2 = .100, as well as the observer’s presence and type, F(3, 455) = 6.311, p < .001, η2 = .040.

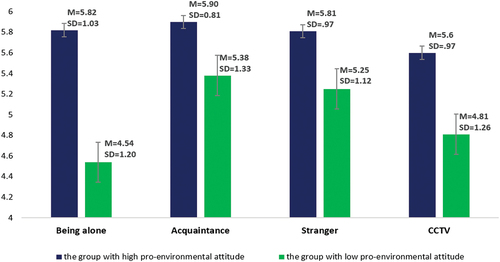

As shown in which showed the results of one-way ANOVA analysis, the group with high pro-environmental attitude displayed a higher level of waste sorting intention in all conditions, compared to the group with low pro-environmental attitude.

Figure 3. The difference in waste sorting intention between high and low pro-environmental attitudes.

However, within the group with high pro-environmental attitude, the differences in waste sorting intention by an observer’s presence and type were not significant, F = .211, p > .05. Even though the mean value of waste sorting intention was highest when participants were with an acquaintance (M = 5.90, SD = .81), these differences were statistically insignificant compared to the mean values of the conditions when they were being alone (M = 5.82, SD = 1.03), with a stranger (M = 5.81, SD = .97), or under CCTV observation (M = 5.60, SD = .97).

On the other hand, within the group with low pro-environmental attitude, the differences in waste sorting intention among four conditions were significant, F = 6.642, p < .001. Compared to the mean value of waste sorting intention under the condition of being alone (M = 4.54, SD = 1.20), the intention was higher under the condition of observer presence. Specifically, the highest waste sorting intention was indicated under the condition of acquaintance (M = 5.38, SD = 1.33), and the next highest waste sorting intention was indicated under the stranger condition (M = 5.25, SD = 1.12). Relatively, participants showed low waste sorting intention under the condition of CCTV (M = 4.81, SD = 1.26).

To confirm, within the group with low pro-environmental attitude, whether the differences in waste sorting intention are statistically significant, post-hoc test was undertaken. As indicated in , the condition of acquaintance formulated a significantly higher waste sorting intention than the condition of being alone (MD = 0.84, p < .001) and compared to the condition of CCTV (MD = 0.57, p < .001). Similarly, the stranger condition also showed a significantly higher waste sorting intention than the condition of being alone (MD = 0.71, p < .01) and compared to the condition of CCTV (MD = 0.44, p < .01). However, there was no significant difference in waste sorting intention between the conditions of acquaintance and stranger (MD = 0.13, p > .05) as well as between the conditions of CCTV and being alone (MD = 0.27, p > .05).

Table 2. Post-hoc test investigating the differences in waste sorting intention within a group with low pro-environmental attitude.

Mediating role of impression management

We drew 5,000 resamples using Model 4 of SPSS PROCESS macro for bootstrapping analysis of the mediating effect of impression management on waste sorting intention affected by the observer type. The analysis was proceeded in four steps. For the first step, the impact of observer type on impression management was analyzed. The analysis results confirmed that the model fitness was statistically significant, F = 5.402, p < .001, R2 = .034. The findings indicated that the impression management was increased by the presence of an acquaintance (β = .399, p < .05) and the presence of a stranger (β = .349, p < .05). In contrast, the CCTV condition did not affect impression management (β = .181, p > .05).

As the second step, the direct effect of observer type on waste sorting intention was analyzed. This model fitness was also statistically significant, F = 5.705, p < .001, R2 = .036. The results show that the condition of acquaintance significantly affected waste sorting intention (β = .583, p < .001). Likewise, the stranger condition also significantly influenced waste sorting intention (β = .406, p < .05). However, the CCTV condition did not significantly affect waste sorting intention (β = .005, p > .05).

For the third step, both variables of observer type and impression management were put in as independent variables to confirm whether the coefficients of each condition are significantly decreased or not. As a result of the analysis, the model fitness was statistically significant, F = 9.472, p < .001, R2 = .076. Although the impact of an acquaintance on waste sorting intention decreased compared to direct effect, the impact was still significant (β = .398, p < .05). The effect of stranger condition on the intention also decreased compared to direct effect, but the impact was significant (β = .337, p < .05). Most importantly, the effect of impression management on waste sorting intention was significant (β = .228, p < .001). On the other hand, as confirmed in the second step, waste sorting intention was not influenced by the CCTV condition (β = .131, p > .05).

Finally, Bootstrapping test was conducted to ascertain the mediating role of impression management (see ). The findings demonstrated that the mediating effect of impression management was statistically significant in the relationship between the presence of acquaintance and waste sorting intention, β = .398, SE = 0.153, Boot 95% CI [0.102, 0.691]. It was also confirmed that impression management mediates the relationship between the presence of a stranger and waste sorting intention, β = .338, SE = 0.141, Boot 95% CI [0.059, 0.609]. However, the mediating effect was not significant under the CCTV condition. It could imply that impression management partially mediates the relationship between waste sorting intention and the effect of observer type.

Table 3. Bootstrapping test on the mediating effect of impression management.

General discussion

This research started with a curiosity why the recycling rate of plastic waste throughout the world is only 9% (OECD, Citation2022) in the situation where the global production of plastic products is significantly increasing every year, and most people are generally aware of the seriousness of environmental pollution and have a positive attitude toward pro-environmental behavior (Geng et al., Citation2017; KEITI, Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2020). Although many research have suggested the various factors including personal, psychological, and social factors (Gifford & Nilsson, Citation2014; X. Li et al., Citation2019) which influence individuals’ pro-environmental attitude, intention, and behavior, this study wanted to find the factors that can directly promote publics’ plastic waste sorting behavior by increasing waste sorting intention.

To investigate the factors which lead people to unconsciously practice waste sorting behavior, we focused on the social factors that can inadvertently induce an individual’s pro-social behavior. Given that human behavior is normally affected by others around oneself (Argo et al., Citation2005; Beatty & Ferrell, Citation1998; Childers & Rao, Citation1992; J. H. Kim et al., Citation2008; Luo, Citation2008; D. Rook & Fisher, Citation1995; Zajonc, Citation1965), confirming the mere presence effect of observer on the waste sorting intention seemed to be meaningful.

Supporting our predictions, a series of results showed that the presence of an observer in recycling place significantly influenced individual waste sorting intention. Participants were more inclined to increase their intention to detach vinyl labels from plastic bottles when an observer was present. Of course, a previous study also confirmed the audience effect on consumer’s pro-environmental product purchasing behavior, stating that simply making the concept of a public audience salience leads people to desire may types of green product (Griskevicius et al., Citation2010). However, the current study further demonstrated that the mere presence effect could unwittingly promote people’s waste sorting behavior by tapping into increased waste sorting intention due to the observer’s presence. Furthermore, our findings also shed new light on the notion related toYerkes and Dodson (Citation1908). This is because the result implies that the performance of easy task including waste sorting behavior, which are typically practiced in everyday life, can be enhanced by induced arousal due to the presence of others.

Additional findings showed that people vary their plastic waste sorting intention depending on the psychosocial distance with the audience who is present in the recycling place. The participants expressed a significantly increased waste sorting intention when an acquaintance or a stranger was present alongside them, compared to the two situations where a CCTV was installed and where they were alone. Especially, people showed the highest waste sorting intention under the condition of acquaintance. These results imply that the psychosocial distance with the observer also affects personal pro-environmental behavior. It is also in accordance with previous studies that confirmed the close relationship with others is more likely to affect an individual’s pro-social behavior (Barclay & Barker, Citation2020; Kawamura & Kusumi, Citation2018; M. Li et al., Citation2022).

In this study, the reason why the social closeness with an observer facilitates people’s pro-environmental behavior was explained by the motivation of impression management. We found out impression management mediated the relationship between waste sorting intention and the type of observer. According to prior studies, in social situation, people take various strategies for impression management such as engaging in socially desirable behavior (Gardner & Martinko, Citation1988; Grant & Mayer, Citation2009; Sassenrath, Citation2020; Schlenker, Citation1980; Schlenker & Britt, Citation1999). The participants might have increased waste sorting intention in an effort to manage their social image to give a positive impression to an acquaintance or a stranger.

However, the participants with high pro-environmental attitude were not significantly affected by an observer’s presence and type in contrast to the participants with low pro-environmental attitude. The results also correspond with previous research which ascertained that people with high pro-environmental attitude constantly practice eco-friendly behavior in everyday lives regardless of external factors (Casaló & Escario, Citation2018; Langenbach et al., Citation2020; Maedeh et al., Citation2019; Tian et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, people with low pro-environmental behavior could change their intention to engage in pro-environmental behavior based on the external factors, such as the presence of others and social distance with them.

Although the participants with low pro-environmental attitude showed a lower waste sorting intention in all conditions (being alone, acquaintance, stranger, CCTV) compared to the participants with high pro-environmental attitude, they increased waste sorting intention under the conditions of acquaintance and stranger. Otherwise, the circumstance with CCTV did not enhance their waste sorting intention. It signifies that both variables of an observer’s presence and social distance exert significant impact on waste sorting intention of people with weaker eco-friendly attitude.

As considering the discovery of current study, locating waste sorting place in visible areas may be more effective to promote public pro-environmental behavior rather than installing CCTV cameras. This is because despite active efforts by local governments in Korea over the past decade to install CCTV cameras in waste sorting facilities, the issue of public waste sorting behavior persists. Along with this problem, many studies have been conducted to analyze the effectiveness of CCTV in addressing the current situation (K. Y. Kim et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the approach, placing waste sorting place in observable area, can activate people’s impression management motivation, and eventually lead them to more properly sort plastic waste in recycling place. To address the environmental pollution associated with consumers’ plastic consumption and disposal habits, setting up visible waste sorting areas might be one of the more effective solutions than installing CCTV cameras.

Indeed, we recognize the importance of consistently providing citizen with information and educational programs on proper waste sorting methods. While utilizing external conditions might be effective in increasing public engagement with waste sorting practices, it is equally imperative to initially focus on fostering individuals’ pro-environmental attitude. To encourage more people to engage in proper waste sorting behavior, strategies like implementing educational programs focused on methods for environment prevention in everyday life should be also seriously considered (Ajaps et al., Citation2015; Jensen, Citation2010; Rickinson, Citation2001; Zsóka et al., Citation2013). This suggestion aligns with the current study’s results, which demonstrate that individuals with a strong pro-environmental attitude tend to exhibit a higher intention to sort plastic waste correctly, regardless of external factors, such as the presence and type of observer.

As a result, we confirmed that the mere presence effect and the type of observer have a significant impact on individual waste sorting intention through impression management. This study also emphasizes the importance of increasing public pro-environmental attitude to encourage practical pro-environmental behavior. The current study might contribute to the extended understanding of social influence on consumer pro-environmental behavior, in that demonstrating how the mere presence of others and psychosocial distance can affect people’s pro-environmental behavior. Moreover, by confirming the mediating role of impression management, we verified the psychological mechanism underlying the effect of an observer’s presence and type.

However, it could not be denied that this study focused solely on one psychological variable: impression management, to explain the causes of the effect of an observer’s presence and type. Additionally, while the researchers extracted the impression management variable through logical thought processes based on the studies related to Mere Presence Effect and Social Impact Theory, and verified the mediating role in the group of people with low pro-environmental attitude, the other external factors were not taken into account. For instance, apart from the impression management factor, an individual’s past experience related to positive or negative reinforcement from others could potentially have influenced the intention to engage in waste sorting, whether or not an observer is present. In fact, may studies have suggested that an individual’s past memories on moral reinforcement have a significant impact on the person’s pro-social behavior (Furukawa et al., Citation2023; Ramaswamy & Bergin, Citation2009; Tasimi & Young, Citation2016). Therefore, in future studies, it is necessary to consider various psychological factors which are related to social influence on pro-environmental behavior, going beyond impression management.

Moreover, a vast body of studies has emphasized that a pro-environmental attitude does not always translate into practical behavior due to additional factors, such as cost, time efficiency, and situational barriers (Colombo et al., Citation2023; Hau & Dong, Citation2022; Renondo & Puelles, Citation2017; Wyss et al., Citation2022). However, the current study did not address these extra factors, which could potentially influence the relationship between pro-environmental attitude and waste sorting intention. It solely examined the moderating role of participants’ pro-environmental attitude in the relationship between an observer’s influence and waste sorting intention. Given that reality often involves complex situations with numerous unexpected factors, future studies should conduct on-site experiments to better understand the influence of an observer’s presence and type on people’s waste sorting behavior.

Foremost, it is crucial to consider intervening factors that bridge the gap between pro-environmental attitude, waste sorting intention and actual behavior to ensure the generalizability of this study’s findings. During the assessment of participants’ intentions regarding waste sorting, there might have been a tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner, aligning their answers with the research’s expectations. This inclination may have arisen due to the explicit outline of key variables and situational scenarios involving waste sorting intention within the questionnaire. These scenarios encompassed situations of sorting waste alone, with an acquaintance, a stranger, or under CCTV surveillance in the waste sorting place. Consequently, these prompts could have influenced participants to respond in a way that aligned with the anticipated outcomes sought by the current study. This limitation underscores the study’s reliance on situational scenarios without direct observation of participants’ real behavior, emphasizing the necessity for more comprehensive future investigations.

Nevertheless, we cautiously predict that in real-life situations, the impact of an observer’s presence might be more pronounced than indicated by the current study. This speculation arises from the lack of realism in the questionnaire scenarios used for waste sorting situations. In other words, while people make their decision to separate labels from the bottles in real life, the scenario presented in the questionnaire might not be fully reflect this, since the actual presence or absence of an observer may amplify the impact compared to simply imagining the situation. Even if an individual’s intention for waste sorting might not be high, the mere presence of an observer could either subconsciously or consciously increase waste sorting behavior in line with many previous studies which confirmed the effect of other’s mere presence (Charles et al., Citation2010; Hamilton & Lind, Citation2016; Monterio et al., Citation2023).

Despite the debated limitations in the study’s findings, we have successfully confirmed the impact of an observer’s presence and type on participants’ waste sorting intention. Consequently, we anticipate that this study could contribute to a broader understanding of people’s pro-environmental intentions, particularly by considering the moderating role of pro-environmental attitude and the mediating role of impression management motivation. Addressing the discussed limitations and conducting research with a larger sample size to generalize the findings is expected to yield more comprehensive results. It is also anticipated that this study could serve as foundational data for future research exploring the influence of others on pro-environmental behaviors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajaps, S., McLellan, R., Gritter, K., & Gritter, K. (2015). “We don’t know enough”: Environmental education and pro-environmental behaviour perceptions. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1124490. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2015.1124490

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–27). Clark University Press.

- Al-Shatti, E., Marc, O., Philippe, O., & Michel, Z. (2022). Impression management on Instagram and unethical behavior: The role of gender and social media fatigue. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169808

- Argo, J. J., Dahl, D. W., & Manchanda, R. V. (2005). The influence of a mere social presence in a retail context. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1086/432230

- Bao, X. M., Park, J. C., & Joung, S. H. (2019). Determinants of eco-friendly consumption behavior: Focusing on eco-friendly attitude, environmental identity and normalization of eco-friendly consumption behaviors. Consumer Policy and Education Review, 15(3), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.15790/cope.2019.15.3.127

- Barclay, P., & Barker, J. L. (2020). Greener than Thou: People who protect the environment are more cooperative, compete to be environmental, and benefit from reputation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 72, 101441. Article 101441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101441.

- Batolas, D., Perkovic, S., & Mitkidis, P. (2023). Psychological and hierarchical closeness as opposing factors in whistleblowing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(2), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09849-5

- Beatty, S. E., & Ferrell, M. E. (1998). Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. Journal of Retailing, 74(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80092-X

- Begley, P. T. (2004). Understanding valuation processes: Exploring the linkage between motivation and action. International Studies in Educational Administration, 32(2), 4–17.

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Benenson, J., Markovits, H., & Hultgren, B. (2013). Social exclusion: More important to human females than males. Public Library of Science ONE, 8(2), e55851. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055851

- Blankenberg, A., & Alhusen, H. (2019). On the determinants of pro-environmental behavior: A literature review and guide for the empirical Economist. Behavioral & Experimental Economics eJournal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3473702

- Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, K. M., Turnley, W. H., & Gilstrap, J. B. (2008). A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1080–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324325

- Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (1999). Measuring impression management in organizations: A scale development based on the Jones and Pittman Taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods, 2(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819922005

- Casaló, L. V., & Escario, J. J. (2018). Heterogeneity in the association between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior: A multilevel regression approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 175, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.237

- Charles, F. B., Adnan, A., & Marilyn, D. V. (2010). Social impairment of complex learning in the wake of public embarrassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1801_4

- Childers, T. L., & Rao, A. R. (1992). The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1086/209296

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591–621. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Colombo, S. L., Chiarella, S. G., Raffone, A., & Simione, L. (2023). Understanding the environmental attitude-behaviour gap: The moderating role of dispositional mindfulness. Sustainability, 15(9), 7285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097285

- Cottrell, N. B., Wack, D. L., Sekerak, G. J., & Rittle, R. H. (1968). Social facilitation of dominant responses by the presence of an audience and the mere presence of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(3), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025902

- DeVille, N. V., Linda, P. T., Olivia, P. S., Grete, E. W., Teresa, H. H., Kathleen, L. W., Eric, B., Peter, H. K., Jr., & Peter, J. (2021). Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147498

- Dixit, S., & Badgaiyan, A. J. (2016). Towards improved understanding of reverse logistics – examining mediating role of return intention. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 107(12), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.021

- ElHaffar, G., Durif, F., & Dubé, L. (2020). Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 122556–122556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556

- Etienne, H., & Charton, F. (2023). A mimetic approach to social influence on Instagram. eprint arXiv:2305.04985. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.04985

- Evans, O. G. (2023). Social impact theory in psychology. Retrieved September 20, 2023. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-impact-theory.html

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Norris, M. E. (2012). Conformity, compliance and obedience. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0075

- Farjam, M., Nikolaychuk, O., & Bravo, G. (2019). Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecological Economics, 166, 106434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106434

- Feng, S., Qiu, S., Gibson, D., & Ifenthaler, D. (2022). The effect of social closeness on perceived satisfaction of collaborative learning. Open and inclusive educational practice in the digital world. Cognition and Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age. Springer, Cham. 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18512-0_7

- Fielding, K. S., & Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

- Filimonau, V., Matute, J., Kubal-Czerwińska, M., & Mika, M. (2023). Religious values and social distance as activators of norms to reduce food waste when dining out. Science of the Total Environment, 868(10), 161645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161645

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1974). Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychological Review, 81(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035872

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Furukawa, Y., Fuji, S., & Sugimura, S. (2023). Good children do not always do good behavior: Moral licensing effects in preschoolers 1, 2, 3. Japanese Psychological Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12447

- Gardner, W. L., & Martinko, M. J. (1988). Impression management in organizations. Journal of Management, 14(2), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400210

- Geng, J., Long, R., Chen, H., & Li, W. (2017). Exploring the motivation-behavior gap in urban residents’ green travel behavior: A theoretical and empirical study. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 125, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.06.025

- Gerell, M. (2021). CCTV in deprived neighbourhoods – a short-time follow-up of effects on crime and crime clearance. Nordic Journal of Criminology, 22(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578983X.2020.1816023

- Gholamzadehmir, M., Sparks, P., & Farsides, T. (2019). Moral licensing, moral cleansing and pro-environmental behaviour: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101334

- Gifford, R. (2011). The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023566

- Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 141–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12034

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

- Goldberg, S. C. (2023). Llocutionary force, speech act norms, and the coordination and mutuality of conversational expectations. Sbisà on Speech as Action, 2147483647–2147483647. Palgrave-Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22528-49

- Grant, A. M., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013770

- Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J., & Bergh, B. V. D. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017346

- Hamilton, A. F. C., & Lind, F. (2016). Audience effects: What can they tell us about social neuroscience, theory of mind and autism? Culture of Brain, 4(2), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40167-016-0044-5

- Hamzah, M. I., & Tanwir, N. S. (2021). Do pro-environmental factors lead to purchase intention of hybrid vehicles? The moderating effects of environmental knowledge. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123643

- Haque, I. U., Khan, S., & Mudarik, M. S. (2023). Effect of social media influencer on consumer purchase intention: A PLS-SEM study on branded luxury fashion clothing. Journal of Mass Communication, 28(1), 2219–2627. https://doi.org/10.22555/pbr.v25i1.887

- Härtel, T., Randler, C., & Baur, A. (2023). Using species knowledge to promote pro-environmental attitudes? The association among species knowledge, environmental system knowledge and attitude towards the environment in secondary school students. Animals (Basel), 13(6), 972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13060972

- Hatcher, J. W., Cares, S., Detrie, R., Dillenbeck, T., Goral, E., Troisi, K., & Whirry-Achten, A. M. (2016). Conformity, arousal, and the effect of arbitrary information. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(4), 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216670525

- Hau, Y., & Dong, F. (2022). Can environmental responsibility bridge the intention-behavior gap? Conditional process model based on valence theory and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 376, 134166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134166

- Hazlett-Stevens, H., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2021). Regulation of physiological arousal and emotion. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy: Overview and approaches (pp. 349–383). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000218-012

- Helen, V. F., Nia, H. J., Andrew, J. D., Brendan, J. G., Jenna, R. J., Imogen, E. N., Coleen, C. S., Gareth, J. W., Lucy, C. W., & Heather, J. K. (2022). The fundamental links between climate change and marine plastic pollution. Science of the Total Environment, 806(1), 150392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150392

- Huberman, J. S., Suschinsky, K. D., Lalumière, M. L., & Chivers, M. L. (2013). Relationship between impression management and three measures of women’s self-reported sexual arousal. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 45(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033397

- Hu, X., Zhang, Y., & Mai, X. (2023). The impact of social distance on the processing of social evaluation: Evidence from brain potentials and neural oscillations. Cerebral Cortex, 33(12), 7659–7669. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad069

- James, D. L. (2007). Feelings: The perception of self – chapter 4. Autonomic arousal and emotional feeing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195098891.003.0004

- Jensen, B. B. (2010). Knowledge, action and pro-environmental behaviour. Environment Education Research, 8(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145474

- Jones, E. E., Pittman, T. S., & Jones, E. E. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 1, pp. 231–262). https://www.scirp.org/(S(vtj3fa45qm1ean45%20vvffcz55))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=1781340

- Kang, C., Chen, H., Teng, D., Mao, M., Shen, Y., Gan, T., & Hou, G. (2023). The influence of partner presence on cooperation and norm formation. Organizational Psychology, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2755542/v1

- Kawamura, Y., & Kusumi, T. (2018). Relationships between two types of reputational concern and altruistic behavior in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 121(15), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.003

- KEITI. (2021). Research on public perception of pro-environmental products and policies. https://www.keiti.re.kr/site/keiti/ex/board/View.do?cbIdx=318&bcIdx=34000

- Kim, J. H. (2013). The effect of perceived risk, environmental value orientation and perceived psychological distance on environmental behavior. Korean Journal of Consumer and Advertising Psychology, 14(1), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.21074/kjlcap.2013.14.1.155

- Kim, J. H., Kim, T. H., & Jeon, J. A. (2008). The influence of Chemyon (social face) on unplanned upward consumption. Korean Journal of Consumer and Advertising Psychology, 9(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.21074/kjlcap.2008.9.2.149

- Kim, K. Y., Yun, J. O., Lee, S. J., Jeong, D. W., & Jeong, Y. J. (2022). Analysis of the effectiveness of CCTV for preventing illegal dumping of garbage and alternative proposals. 2022 D.M.T Program Awards in Korea. https://www.bigdata-map.kr/datastory/new/story_43

- Klineberg, S. L., McKeever, M., & Rothenbach, B. (1998). Demographic predictors of environmental concern: It does make a difference how it’s measured. Social Science Quarterly, 79(4), 734–754. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42863844

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Kwahk, K. Y., & Ge, X. (2012). The effects of social media on e-commerce: A perspective of social impact theory. 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 1814–1823. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2012.564

- Lalot, F., & Abrams, D. (2023). A stranger or a friend? Closer descriptive norms drive compliance with COVID-19 social distancing measures. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 231(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000524

- Lane, T., Daniele, N., & Silvia, S. (2023). Law and norms: Empirical evidence. American Economic Review, 113(5), 1255–1293. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210970

- Langenbach, B. P., Berger, S., Baumgartner, T., & Knoch, D. (2020). Cognitive resources moderate the relationship between pro-environmental attitudes and green behavior. Environment and Behavior, 52(9), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916519843127

- Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343

- Latané, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review, 88(5), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.88.5.438

- Leary, M. R. (2019). Self-presentation: Impression management and interpersonal behavior. eBook : 9780429497384.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429497384

- Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A Literature Review and Two-Component Model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34

- Li, X., Du, J., & Long, H. (2019). Dynamic analysis of international green behavior from the perspective of the mapping knowledge domain. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(6), 6087–6098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-04090-1

- Li, M., Li, J., Li, H., Zhang, G., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2022). Interpersonal distance modulates the influence of social observation on prosocial behaviour: An event-related potential (ERP) study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 176, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2022.03.013

- Liu, Y., & Bai, Y. (2014). An exploration of firms’ awareness and behavior of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 87, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.04.002

- Luo, X. (2008). How does shopping with others influence impulsive purchasing? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(4), 288–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1504_3

- Maedeh, G., Paul, S., & Tom, F. (2019). Moral licensing, moral cleansing and pro-environmental behaviour: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101334

- Markus, H. (1978). The effect of mere presence on social facilitation: An unobtrusive test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(78)90034-3

- Martino, J. D., Nanere, M. G., & Dsouza, C. (2019). The effect of pro-environmental attitudes and eco-labelling information on green purchasing decisions in Australia. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 31(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2019.1589621

- Maryam, T., & Tye, W. J. (2020). Environmental knowledge gap: The discrepancy between perceptual and actual impact of pro-environmental behaviors among university students. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(2), e2426. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2486

- Matczak, P., Wójtowicz, A., Dabrowski, A., Leitner, M., & Dutkowska, N. S. (2023). Effectiveness of CCTV systems as a crime preventive tool: Evidence from eight Polish cities. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 47(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2021.1976237

- Mathur, S., & Sood, K. (2023). Policing perspective on pre-emptive and probative value of CCTV architecture in the security of the smart city - Gandhinagar. International Journal of Electronic Security and Digital Forensics, 15(3), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESDF.2023.130655

- McFarland, L. A., Hendricks, J. L., & Ward, W. B. (2023). A contextual framework for understanding impression management. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 100912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100912

- Milfont, T. L., & Duckitt, J. (2010). The environmental attitudes inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.001

- Miller, L. B., Rice, R. E., Gustafson, A., & Goldberg, M. H. (2022). Relationships among environmental attitudes, environmental efficacy, and Pro-environmental Behaviors Across and within 11 countries. Environment and Behavior, 54(7–8), 1063–1096. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139165221131002

- Montag, C., Yang, H., & Elhai, J. D. (2021). On the psychology of TikTok use: A first glimpse from empirical findings. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 641–673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641673

- Monterio, D., Wang, A., Wang, L., Li, H., Barrett, A., Pack, A., & Liang, H. N. (2023). Effects of audience familiarity on anxiety in a virtual reality public speaking training tool. Universal Access in the Information Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-023-00985-0

- Naguyen, H. V., Nguyen, C. H., & Hoang, T. T. B. (2018). Green consumption: Closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustainable Development, 27(1), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1875

- Nugroho, B., Anggreni, M., Afnanda, M., Arta, D., & Tannady, H. (2023). The role of academic fraud as an intervening variable in relationship of determinant factors Student ethical attitude. Journal on Education, 5(3), 9584–9593. https://doi.org/10.31004/joe.v5i3.1832

- OECD. (2022). Plastic pollution is growing relentlessly as waste management and recycling fall short, says OECD. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.htm

- O’Riordan, T. (2009). Why carbon-reducing behavior is proving so frictional. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(5), 2. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.51.5.c2-c2

- Park, S. H., & Oh, K. H. (2014). Environmental knowledge, eco-friendly attitude and purchase intention about eco-friendly fashion products of fashion consumers. Fashion & Textile Research Journal, 16(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.5805/SFTI.2014.16.1.91

- Park, S., Shin, J., & Ponti, G. (2017). The influence of anonymous peers on prosocial behavior. Public Library of Science ONE, 12(10), e0185521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185521

- Paulus, M., Kühn-Popp, N., Licata, M., Sodian, B., & Meinhardt, J. (2013). Neural correlates of prosocial behavior in infancy: Different neurophysiological mechanisms support the emergence of helping and comforting. Neuroimage: Reports, 66(1), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.041

- Perez-Vega, R., Kathryn, W., & Kevin, O. (2016). Social impact theory: An examination of how immediacy operates as an influence upon social media interaction in Facebook fan pages. The Marketing Review, 16(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1362/146934716X14636478977791

- Pernelet, H. R., & Brennan, N. M. (2023). Impression management at board meetings: Accountability in public and in private. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 36(9), 340–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-09-2022-6050

- Piza, E. L., Welsh, B. C., Farrington, D. P., & Thomas, A. L. (2019). CCTV surveillance for crime prevention: A 40-year systematic review with meta-analysis. Criminology & Public Policy, 18(1), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12419

- Preissner, C. E., Oenema, A., & Vries, H. D. (2022). Examining socio-cognitive factors and beliefs about mindful eating in healthy adults with differing practice experience: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00977-4

- Ramaswamy, V., & Bergin, C. (2009). Do reinforcement and induction increase prosocial behavior? Results of a teacher-based intervention in preschools. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540909594679

- Renondo, I., & Puelles, M. (2017). The connection between environmental attitude–behavior gap and other individual inconsistencies: A call for strengthening self-control. Education, Environmental Science, 26(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1235361

- Rickinson, M. (2001). Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research, 7(3), 207–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120065230

- Rook, D. W. (1987). The buying impulse. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1086/209105

- Rook, D., & Fisher, R. (1995). Normative influences on impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1086/209452

- Rook, D. W., & Gardner, M. P. (1993). In the mood: Impulse buying’s affective antecedents. Research in Consumer Behavior, 6(7), 1–28.

- Roos, B. A., Mobach, M., & Heylighen, A. (2023). Challenging behavior in context: A case study on how people, space, and activities interact. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 16(4), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867231178312

- Saracevic, S., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2021). The impact of social norms on pro-environmental behavior: A systematic literature review of the role of culture and self-construal. Sustainability, 13(9), 5156. WU Vienna, 1020 Vienna, Austria. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095156

- Sassenrath, C. (2020). “Let me show you how nice I am”: Impression management as bias in empathic responses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(6), 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619884566

- Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Brooks/Cole.

- Schlenker, B. R., & Britt, T. W. (1999). Beneficial impression management: Strategically controlling information to help friends. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(4), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.559

- Schlenker, B. R., & Weigold, M. F. (1992). Interpersonal processes involving impression regulation and management. Annual Review of Psychology, 43(1), 133–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.001025

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

- Seifi, M., Cozens, P., Reynald, D., Haron, S. H., & Abdullah, A. (2023). How effective are residential CCTV systems: Evaluating the impact of natural versus mechanical surveillance on house break-ins and theft in hotspots of Penang Island, Malaysia. Security Journal, 36(1), 49–81. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-022-00331-8

- Shojaati, N., & Osgood, N. D. (2023). An agent-based social impact theory model to study the impact of in-person school closures on nonmedical prescription opioid use among youth. Systems, 11(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020072

- Silvi, M., & Padilla, E. (2021). Pro-environmental behavior: Social norms, intrinsic motivation and external conditions. Environmental Policy and Governance, 31(6), 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1960

- Statista Research Department. (2023). Global plastic production 1950-2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/282732/global-production-of-plastics-since-1950/

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Szerszynski, B. (2007). The post-ecologist condition: Irony as symptom and cure. Environmental Politics, 16(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010701211965

- Tasimi, A., & Young, L. (2016). Memories of good deeds past: The reinforcing power of prosocial behavior in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 147, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.03.001

- Thian, H., Zhang, J., & Li, J. (2019). The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(7), 7341–7352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07393-z

- Thomas, A. L., Piza, E. L., Welsh, B. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2022). The internationalisation of CCTV surveillance: Effects on crime and implications for emerging technologies. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 46(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2021.1879885

- Tian, H., Zhang, J., & Li, J. (2019). The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(7), 7341–7352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07393-z

- Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. The American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 507–533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1412188