ABSTRACT

Relational sensitivity involves attuning to subtle and complex collaborative dynamics and plays an important role in participatory design (PD) processes. PD practitioners, including researchers, designers, and facilitators, need abilities to navigate group dynamics while responsibly considering their own impact on the process. This article focuses on the term ‘relational sensitivity’ to develop perspectives and a vocabulary for discussing the competence and readiness needed in PD. This knowledge can contribute to design research by addressing the lack of understanding regarding how practitioners are trained in design facilitation and sensitivity to relationships. The article articulates relational sensitivity through the perspectives: sensitivity to self, to intersubjectivity, and to materiality and process. It makes a valuable contribution to the PD field by bringing together and exemplifying concepts and aspects connected to relational sensitivity, as well as applying Wilber’s four-quadrant model and Ofman’s adapted model in a new research context.

1. Introduction

Participatory design (PD) processes are relational and contingent, in which ‘needs emerge, design objects change, designers morph and the design process is continuously reconstructed by all interested publics’ (DiSalvo, Clement, and Pipek Citation2013, 203). To navigate such contingent and relational processes, PD researcher Ann Light (Citation2015, 91) contends that it ‘is more important [for practitioners] to be attuned to relations and ready for anything in these flexible and evolving circumstances than it is to have an action plan’. Furthermore, practitioners, such as designers, researchers, and facilitators who are part of coordinating and facilitating PD processes, require certain readiness – ‘drawing on who [they are] as part of the preparation for designing’ (Akama and Light Citation2020, 19), as their backgrounds, cultures, personalities, and commitments are part of shaping their PD practices.

Relational sensitivity is a term used to describe practitioners’ readiness and involves attuning to ‘invisible, subtle, and complex dynamics, and how these [dynamics] are shaped and conditioned by our upbringing, culture and society’ (Akama and Light Citation2018, 2). It can involve an embodied knowing that shifts from moment to moment, often in response to the intersubjective nuances of the group, allowing practitioners to respond to collaborative dynamics in a situation. This relational sensitivity plays a crucial role in facilitating design activities during workshops. By remaining attuned and responsive to the relationships they are involved in, practitioners can enhance their ability to navigate and facilitate design processes. This not only heightens the ability to respond to situations, ‘respons-ability’, but also strives towards responsible practices in PD (Akama and Light Citation2018).

This article focuses on the term ‘relational sensitivity’ to develop perspectives on what readiness and sensitivities are important for practitioners, and why, in order to navigate complex, subtle dynamics in PD processes. In a literature review on design facilitation, Mosely, Markauskaite and Wrigley (Citation2021) highlight a lack of understanding of how design education prepares students for facilitation, despite this being a common taken by designers in participatory processes (Manzini Citation2015). Additionally, scholars have criticised the lack of training in body-related awareness in design education in academia, which is important for reflexivity, self-awareness, sensitivity to relations, and facilitation (Akama and Light Citation2018; Malinverni and Pares Citation2016; Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016). Furthermore, scholars argue for a need to conceptualise practitioners’ relational expertise and readiness for collaborative design processes (Akama and Light Citation2018, Citation2020; Dindler and Iversen Citation2014). Through a literature review, this article aims to synthesise perspectives and develop a vocabulary for discussing relational sensitivity in PD. The article also uses a model by Wilber (Citation2000), from developmental psychology, and Ofman’s adaption of this model (Citation2013), in order to enrich the concept of relational sensitivity. Through the exploration and exemplification of relational sensitivity, the aim is to provide insights into the training and development of readiness in PD. This endeavour seeks to foster responsible practices of designing with others, highlighting the significance of nurturing care and the ability to respond to the relationships one is involved in.

2. Background

The inspiration for using and developing the term ‘relational sensitivity’ comes from the work of Akama (Citation2015) and Akama and Light (Citation2018). Akama (Citation2015) uses ‘relational sensitivity’ in connection to the Japanese concept ‘ma’, which describes attention towards the in-between space, silence, atmospheres and potential. Akama’s proposition is that ‘co-designing is performed and emerges from relational sensitivity’ (Citation2015, 1) and that being attuned to ma or between-ness can support a subtle attunement and responsiveness to the relational dimensions of designing. Ma as a relational sensitivity offers a perspective to designing that emphasises the felt, invisible, relational and spiritual. ‘relational sensitivity’ is also used in Akama and Light’s work (Citation2018) on ‘poise’ and ‘punctuation’, in which they examine the relational and subtle dimensions of working in contingent, participatory processes. They discuss the importance of practitioners’ readiness to be attuned and responsive to dynamics in a group (punctuation) and to cultivate self-awareness of their ways of being and behaving (poise) in the shaping of responsible collaborative design practices. Since poise and punctuation were developed from Akama and Light’s own PD practices, this article draws together the work of other researchers focused on navigating collaborative dynamics, which could further an understanding of relational sensitivity in PD.

In this paper, I use the term ‘participatory design’ to denote collaborative processes involving multiple groups, stakeholders and/or communities, which explore and enact possible alternative futures. These dialogical and explorative processes may not necessarily result in the creation of a thing but can be understood as reconfiguring relationships between people, practices, places, and structures (Binder et al. Citation2011; Light and Akama Citation2014).

3. Methodology

Starting from the work of Akama (Citation2015) and Akama and Light (Citation2018), this article elaborates on relational sensitivity in PD processes through a literature review, to explore and draw together relevant concepts in PD research. At the time of the literature search (May 2021–July 2022), only Akama and Light (Citation2018) and Akama (Citation2015) were using the term ‘relational sensitivity’. Therefore, a vocabulary connected to relational sensitivity was elaborated (see ) and papers were selected from the Participatory Design Conference (PDC) 2022, which had a relevant theme and took place after the literature search. Initially, the literature review did not focus on the practitioners to explore relational sensitivity more broadly in respect to various actors in PD.

Table 1. The literature review process.

To analyse the literature covered in this review, each article was read by the author and summarised in a table with six categories (). The concepts and aspects elicited from the literature where then mapped on to Wilber’s four-quadrant model (described in the next section) and were then clustered into various related themes. The concepts and aspects were then mapped on Ofman’s adapted four-quadrant model (Citation2013) to compare and deliberate on the use of Wilber and Ofman’s models.

Table 2. Categories for summarising articles.

4. Theoretical framework

The four-quadrant model (Wilber Citation2000) is used to interact with and analyse the literature. The four-quadrant model () comes from developmental psychology and distinguishes different dimension of how humans experience reality, covering the individual and collective (upper and lower quadrants) and the internal and external (left and right quadrants). The model highlights four different perspectives – ‘I’, ‘We’, ‘It’ and ‘Its’. The ‘I’ perspective in the model refers to the subjective, focusing on one’s individual experience, such as thoughts, emotions, memories, and sensations. The awareness of the ‘I’ perspective can be likened with poise, which focuses on the awareness of the self. The ‘We’ perspective refers to the intersubjective, which centres on what happens between individuals – shared values, relationships, and cultures. The awareness of the ‘We’ can be likened to punctuation, which focuses on an awareness of the various dynamics of a collaboration. The ‘It’ perspective refers to the objective, focusing on observable and measurable (individual) things, such as a thing, activity, and behaviour. The ‘Its’ perspective refers to the inter-objective, which focuses on the plurality of things, which can include multiple material things, networks, and systems. Whereas the ‘I’ and ‘We’ perspectives are intangible and not directly observable, the ‘It’ and ‘Its’ are tangible and observable. The model emphasises that all four dimensions of experiences are always part of any given moment and are interconnected; that is, one quadrant is never mutually exclusive of, divorced from or reduced to another. Hence, an individual’s emotions (‘I’) could be observed through their behaviour (‘Its’).

Figure 1. The four-quadrant model by Wilber (Citation2000). (All figures are drawn by the author of the present article).

The purpose of using the four-quadrant model in PD is because the left quadrants (‘I’ and ‘We’) bear resemblances with poise and punctuation – an awareness for the subjective and intersubjective. However, by using the four-quadrant model, the right quadrants offer an expanded perspective by emphasising materiality and processes and their interrelationship to the left quadrants. It thereby enables exploration of the intricate relationships between the ‘internal’ and more subtle dynamics of a PD process with the material and systemic dimensions involved. Hence, by employing the four-quadrant model to map other concepts in PD, there is potential to enhance the understanding of relational sensitivity derived from poise and punctuation.

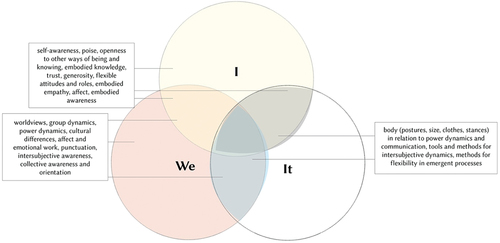

Towards the conclusion of this article, Daniel Ofman’s (Citation2013) undefined adaptation of the four-quadrant model () is employed. In this adaptation, the categories of ‘It’ and ‘Its’ are merged to depict the interconnections between the various perspectives through a Venn diagram. By mapping the literature using both Wilber’s and Ofman’s models, the models are compared and discussed in relation to the concept relational sensitivity.

5. Findings

The findings draw together perspectives on relational sensitivity from the literature in the review. The ‘I’, ‘We’, ‘It’ and ‘Its’ perspectives from four-quadrant model (Wilber Citation2000) and emergent themes are used to structure the findings.

5.1. Relational sensitivity from an ‘I’ perspective

The following aspect and concepts of relational sensitivity are connected to the ‘I’ perspective and have been organised into the following themes ().

5.1.1. Design researchers’, facilitators’ and participants’ embodied awareness

A perspective that emerged in connection with relational sensitivity in the ‘I’ quadrant concerns embodied awareness. Research highlights the importance of embodied awareness, also referred to as embodied knowledge, in fostering awareness of oneself and involves noticing one’s emotions, thoughts, sensations, and values (Akama and Light Citation2018; Gottlieb Citation2022; Malinverni and Pares Citation2016; Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016). The importance of embodied awareness is described differently among various actors involved in PD processes. Design researchers and facilitators emphasise the value of their own embodied awareness or knowledge when navigating collaborative dynamics and facilitating participatory processes (Akama and Light Citation2018; Gottlieb Citation2022; Malinverni and Pares Citation2016; Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016). This includes recognising and acknowledging feelings of tension within themselves during a collaborative process in PD, which could allow the practitioner to discern the presence of diverse perspectives and values within the group (Gottlieb Citation2022). Other studies focus on participants’ embodied awareness as a means to recognise and express authentic needs and interests, fostering genuine participation in the process (Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016). Research acknowledges the significance of embodiment in promoting reflexivity (Malinverni and Pares Citation2016), self-awareness (Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016), and navigating intersubjective dynamics (Akama and Light Citation2018). However, the research also highlights the lack of embodiment training in academic design curricula.

5.1.2. Designers’ and design researchers’ ways of being that impact relationships

A further perspective connected to relational sensitivity in the ‘I’ quadrant relates to normative claims of how designer researchers or designers should be in participatory processes (Ho, Ma, and Lee Citation2011; Light and Akama Citation2014; Petrella, Yee, and Clarke Citation2020; Steen Citation2013), as opposed to what they should do (Tjahja and Yee Citation2022). This focus brings attention to attitudes and personal characteristics that are important in enabling designers and design researchers in participatory processes to build trust and long-lasting relationships. Such attitudes and characteristics include: sensitivity to relations (Light and Akama Citation2014); embodied empathy for others’ experiences (Ho, Ma, and Lee Citation2011); generosity and vulnerability for cultivating mutuality and reciprocity (Petrella, Yee, and Clarke Citation2020); reflexivity for developing one’s practice (Akama and Light Citation2018; Barcham Citation2021; Steen Citation2013; St John and Akama Citation2022, Tjahja and Yee Citation2022); flexible attitude and roles; and openness to diverse ways of knowing and doing (Tjahja and Yee Citation2022; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019; St John and Akama Citation2022). These personal characteristics are defined in relation to case studies and interviews with design practitioners engaged in participatory processes. Examples illustrate how designers’ natural attitudes or lack of sensitivity towards collaborative partners or users can disrupt the establishment of respectful relationships and the sustainability of collaborations (Ho, Ma, and Lee Citation2011; Light and Akama Citation2014). For instance, Ho, Ma, and Lee (Citation2011) describe the insensitivity and lack of respect displayed by design students when visiting participants’ homes. The scholars argue that designers involved in collaborative processes need to develop embodied empathy and sensitivity to respectfully interact with design participants and navigate various contexts. Contrary to a dichotomy between being and doing (Tjahja and Yee, Citation2022), the example highlights the interconnectedness of practitioners’ ways of being and their actions, and its influence on building and maintaining relationships within design collaborations.

5.1.3. Design researchers’ awareness of their own positionality

Lastly, a perspective that emerged in connection with relational sensitivity in the ‘I’ quadrant concerns the practitioners’ awareness of their own positionality and how it interconnects with other people. The words ‘self-awareness’ (Akama and Light Citation2018), ‘reflexivity’ (Bustamante Duarte et al. Citation2021; Malinverni and Pares Citation2016; St John and Akama Citation2022; Steen Citation2013), ‘self-reflexivity’ (Spiel et al. Citation2020), ‘reflexive-awareness’ (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019) and ‘poise’ (Akama and Light Citation2018, Citation2020; Gottlieb Citation2022) are used to describe awareness on positionality. This article will refer to these as ‘awareness to positionality’ to differentiate between various forms of self-awareness outline in the preceding sections. Awareness on one’s positionality is described as important for PD practitioners (i.e. researchers, designers and facilitators) to account for their subjectivity and how their roles, perspectives and values are part of ethical and methodological decision-making (Malinverni and Pares Citation2016).

Ethical considerations drive the need for awareness of positionality, with a focus on addressing inherent power imbalances (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; Speil et al. Citation2020), diverse ways of doing and being (St John and Akama Citation2022) and situated judgements – that is, ethical decisions made in the moment that cannot always be known or assessed beforehand (Malinverni and Pares Citation2016; Speil et al. Citation2018). These reflections on positionality are informed by case studies encompassing various contexts involving vulnerable participants and communities, such as children and/or individuals with disabilities (Speil et al. 2018; Malinverni and Pares Citation2016), young migrants (Bustamante Duarte et al. Citation2021), and indigenous communities (Akama and Light Citation2018; Barcham Citation2021; St John and Akama Citation2022). As an example, when engaging with children, practitioners engage in reflection regarding the appropriate level of closeness they should maintain with the participants and the extent of personal information they should disclose (Speil et al., Citation2018). These deliberations take into account the temporary nature of the collaborations and the potential risk of participants developing attachments to the practitioners. By reflecting on their positions, experiences and actions, practitioners thereby inform their relationships, as well as the ethical and methodological decisions in their participatory practice.

5.2. Relational sensitivity from a ‘We’ perspective

The following aspect and concepts of relational sensitivity are connected to the ‘We’ perspective and have been organised into thematic clusters ().

5.2.1. Facilitators’ and design researchers’ attunement and responsiveness to group dynamics

Relational sensitivity can be described in relation to design researchers’ and facilitators’ ability to attune and respond to what is happening in the group dynamics (Akama and Light Citation2018, Citation2020; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019; Mosleh and Larsen Citation2021), which has the capacity to encourage or discourage participation (Ehret and Hollett Citation2016; Light and Akama Citation2012). The term ‘punctuation’ has been used to describe attunement and responsiveness to the flux of intersubjective dynamics (Akama and Light Citation2018). This perspective highlights the unpredictability of facilitation practice, which requires the presence of, attunement to, and responsiveness to intersubjective dynamics and the contingency of the process (Akama and Light Citation2018, Citation2020; Mosleh and Larsen Citation2021). For example, Light (in Akama and Light Citation2018) describe the flexibility of navigating and adopting design activities throughout a workshop to support the group’s energy levels and aim for efficiency. This need and ability of being responsive in situations opposes the idea that processes or outcomes are controlled by facilitation or by ‘staging’ workshops via tools and methods (Mosleh and Larsen Citation2021).

Various aspects are described as important for facilitators to attune to and navigate within group dynamics, including: (i) the (re)negotiation of shared values (Agid and Chin Citation2019; Gottlieb Citation2022; Iversen, Halskov, and Leong Citation2012); (ii) affect (e.g. laughter and tensions), which is part of creating a sense of belonging and sustaining participation (Balaam et al. Citation2019; Branco, Quental, and Ribeiro Citation2017; Détienne, Baker, and Burkhardt Citation2012; Ehret and Hollett Citation2016; Petrella, Yee, and Clarke Citation2020; Wilson and Morrissey Citation2022); and (iii) building and maintaining trust with and among the group (Sandman, Meguid, and Levänen Citation2020; Zhang, Ji, and Chen Citation2022; Petrella, Yee, and Clarke Citation2020; Tjahja and Yee Citation2022; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019). Embodied knowledge is described as integral in thinking and feeling what is going on and responding in the moment to the group (Light and Akama Citation2012, 69).

5.2.2. Design practitioners’ awareness of power dynamics

A large emphasise in relation to navigating group dynamics in the literature is on power dynamics. Based on case studies, articles in the literature review examine the inherent power dynamics in collaborations between participants themselves (Taoka, Kagohashi, and Mougenot Citation2021; Van Mechelen et al. Citation2014), design researchers and children/other participants (Speil et al. Citation2020; Agid and Chin Citation2019; Pitt and Davis Citation2017), or designers and participants with different mental, physical and emotional capabilities (Speil et al. Citation2020; Bellini et al. Citation2019; Branco, Quental, and Ribeiro Citation2017; Del Gaudio, Franzato, and Jefferson de Oliveira Citation2020; Kelly Citation2019; Sandman, Meguid, and Levänen Citation2020). These articles emphasise the significance of practitioners (including design researchers, designers, and facilitators) being aware of power dynamics when working with groups, as these dynamics have an impact on participation. By acknowledging power dynamics, practitioners can strive to balance or counteract power imbalances in order to foster participation rather than hinder it (Del Gaudio, Franzato, and Jefferson de Oliveira Citation2020; Taoka, Kagohashi, and Mougenot Citation2021). For instance, drawing from reflections on organisational hierarchies in a Japanese context, facilitators can intentionally avoid selecting workshop participants from different hierarchical levels to encourage active participation from all participants (Taoka, Kagohashi, and Mougenot Citation2021).

Another lens on power dynamics is presented in articles focused on the dominance of Eurocentric worldviews in design practices (Akama Citation2017; Akama et al. Citation2017; Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; Barcham Citation2021; St John and Akama Citation2022). These articles critically examine how design practices tend to prioritise methods, techniques, and knowledge, while overlooking the subtle, intuitive, subjective, and spiritual aspects of collaboration. They present case studies where design researchers and designers engage with indigenous communities and explore possibilities for future design practices to incorporate diverse ways of being, doing, and knowing. For example, designers and design researchers describe their use of storytelling to foster deep listening and subjective perspectives (Barcham Citation2021), as well as their efforts to slow down and embrace silence (St John and Akama Citation2022). By acknowledging diverse worldviews, design researchers and designers reflect on ways to shift design practices towards inclusivity, embracing pluralistic and relational approaches to understanding the world.

5.2.3. Design researchers’ and participants’ collective orientation towards others’ contributions

Participatory processes in design are described as unpredictable and contingent, involving multiple people, stakeholders and/or communities (Agid and Chin Citation2019; Akama and Light Citation2018; Bratteteig and Stolterman Citation1997; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019; Shaw Citation2010). The emergent quality is compared to improvisational jazz and theatre (Bratteteig and Stolterman Citation1997; Shaw Citation2010) where each unpredictable contribution responds to others while introducing something new (Shaw Citation2010). In order to collaborate in an emergent process, studies describe the importance of design researchers’ and participants’ collective awareness (Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019), collective orientation and keen intersubjective awareness, in order to engage in and contribute to the collective process (Shaw Citation2010). Such a collective orientation includes a willingness to contribute to the collective process (Shaw Citation2010) and to step into the ‘empty’ void of the not-yet-known paths of a co-creative, emergent process (Akama Citation2015). To be attuned and responsive to others’ contributions can be understood as another kind of relational sensitivity, where the group is open and engaged in contributing to each other’s ideas.

5.3. Relational sensitivity from an ‘It’ perspective

The following aspect and concepts of relational sensitivity are connected to the ‘It’ perspective and have been organised into a thematic cluster ().

5.3.1. The role of the body in power dynamics and communication

A perspective on relational sensitivity in the ‘It’ quadrant concerns how the body plays a role in shaping communicative practices and dynamics (in relation to other bodies). This includes deliberations on how design researchers’ and facilitators’ bodies (i.e. posture and size) play a role in power dynamics (Speil et al. Citation2018; Agid and Chin Citation2019; Bustamante Duarte et al. Citation2021). For instance, when working with children whose bodies can be smaller, researchers discuss associate power relations and adopting speaking to participants at eye level. The clothing worn by design researchers when facilitating sessions is also mentioned as a means of addressing a power balance (Bustamante Duarte et al. Citation2021).

The important role of the body in supporting communication, such as imitating another person’s stance, is also deliberated on (Tenenberg, Socha, and Roth Citation2016). When studying the role of body stance in collaborative design processes between design students, Tenenberg, Socha, and Roth (Citation2016) problematise online collaborations, which can limit the body’s visibility. Focusing on the body (and how it interacts with other bodies) brings attention to the body’s role in shaping power dynamics and enabling communicative practices in design.

5.4. Relational sensitivity from an ‘Its’ perspective

The following aspect and concepts of relational sensitivity are connected to the ‘Its’ perspective and have been organised into thematic clusters ().

5.4.1. The role of tools in shaping intersubjective dynamics

The literature that connects to relational sensitivity in the ‘Its’ quadrant, that is the plural and observable things, structures and networks, focuses on the role of tools (artefacts, materiality and activities) in shaping intersubjective dynamics (see ). The role of tools is explored through case studies (e.g. in projects in urban planning, museums, technology development and care homes) in which design researchers facilitate workshops with various intended users, stakeholders or communities.

Table 3. Tools for intersubjective dynamics.

The articles listed in emphasise the role of tools in intersubjective dynamics between the participants in a process. Through design tools and activities such as walking the land, travelling by boat (Devos and Loopmans Citation2021; Light and Akama Citation2014) and camping (Light Citation2019), the literature describes reshaping design researchers’ and participants’ relationships to each other as well as the land, creating a greater action-potential of possible futures for an area (Devos and Loopmans Citation2021; Ehret and Hollett Citation2016; Light and Akama Citation2014).

Although several studies in the literature review examine the role of tools in mediating intersubjective relationships, some conclude that engagement with the artefacts largely depends on how the participants choose to work with the artefacts (Andersen and Mosleh Citation2021) and on the complex entanglements between people, people, places, practices and artefacts (Taylor, Wujal Wujal Council, and Brereton Citation2022). The conclusion that artefacts ‘do not facilitate relationship building in and of themselves’ (Taylor, Wujal Wujal Council, and Brereton Citation2022, 10) echoes Light and Akama’s contention that ‘it is not meaningful to separate the designer from method since we cannot know participative methods without the person or people enacting them’ (Light and Akama Citation2012, 61). Despite this conclusion, the studies that focus on tools meditating intersubjective dynamics omit descriptions of the people using the tools (Bustamante Duarte et al. Citation2021; Halskov and Dalsgaard Citation2007; Taylor, Wujal Wujal Council, and Brereton Citation2022). This omission is pointed out by Akama and Light (Citation2018), Agid and Chin (Citation2019) and Malinverni and Pares (Citation2016) and motivates their use of autoethnography to bring transparency to subjective perspectives.

5.4.2. Methods and processes for conditions and attitudes in emergent processes

Lastly, a perspective on relational sensitivity in the ‘Its’ quadrant concerns methods and processes that support participants and design researchers working in emergent ways (Agid and Chin Citation2019, Shaw Citation2010; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019; Light Citation2019). By structuring a process with ‘voids’ (Light Citation2019) or through Theory U methodology (Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019), design researchers describe cultivating flexible conditions and attitudes in emergent processes . For instance, research describes how shared agreements can be used to cultivate an openness between design researchers and participants in order to renegotiate decisions and values throughout the process (Agid and Chin Citation2019). The methods and structures for emergent processes are thus connected to enabling flexible collaborative structures in emergent processes and cultivating appropriate attitudes.

5.5. Mapping concepts on the Wilber and Ofman models

Once the aspects and concepts were mapped onto Wilber’s four-quadrant model (), the same process was carried out using Ofman’s adapted model for the purpose of comparison (). The comparison is elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

6. Discussion

This article has organised a range of examples and concepts using the Wilber () and Ofman () models to elaborate on the concept of relational sensitivity. In doing so, it demonstrates a variety of sensitivities associated with the perspectives of ‘I’, ‘We’, ‘It’, and ‘Its’, highlighting nuances within each. For instance, self-awareness (‘I’) could manifest as embodied awareness, understanding of ways of being and behaving, or awareness of one’s positionality. Sensing group dynamics (‘We’) might involve sensitivity towards power dynamics, affect, emotion, or the group’s energy levels. This mapping provides nuanced insights and an expanded vocabulary for discussing various types of relational sensitivity.

Using the Wilber or Ofman model, researchers can explore collaborative work from diverse perspectives and their interrelationships. For instance, instead of solely examining power dynamics through the limited lens of artefacts’ influences (‘Its’) (as in Taylor et al. Citation2022), research could explore how intangible and unobservable aspects (‘I’ and ‘We’) intertwine with the tangible and observable (‘It’ and ‘Its’) in shaping power dynamics. These models acknowledge the inseparability between methods and people, elucidating their interconnectedness and adopt a more holistic approach to evaluating collaborative dynamics.

Moreover, the author of this article has utilised the Ofman model in their research to prompt reflection among PD practitioners and participants, particularly in collectively analysing and evaluating collaborative dynamics (Gottlieb Citation2022, Citation2023). Introducing the Ofman model in these contexts to discuss collaborative dynamics has been more effective than using the terms ‘poise’ and ‘punctuation’, as practitioners found it easier to understand and remember the model’s terminology. Therefore, utilising the Ofman model (Citation2013) could serve as a valuable tool in PD workshops and processes to draw attention to and examine various collaborative dynamics through the lenses of ‘I’, ‘We’, and ‘It’ and their interrelationships.

6.1. Model for conceptualising relational sensitivity

Upon comparing the models, this article has found that the Ofman model is more useful for visualising the interconnectedness of the various perspectives. Through a Venn diagram, the Ofman model visually displays how the perspectives are interconnected and how concepts and aspects of relational sensitivity can belong to more than one quadrant. For instance, ‘embodied empathy’ could be described as both an individual’s way of being (‘I’) and a relationship with others (‘We’). In contrast, the Wilber model, visually separating the perspectives through quadrants, makes this interconnection less apparent.

Additionally, the distinction between the individual ‘It’ and collective ‘Its’ was not clearly delineated in the literature analysis, as findings in ‘It’ could also belong to the ‘Its’ perspective. For example, body postures could be understood not solely belonging to the singular ‘It’ perspective as it involves multiple bodies interacting. Ofman’s adapted four-quadrant model, which combines the ‘It’ and ‘Its’ perspectives, therefore adequately represents the tangible and observable (both singular and plural). By combining the three perspectives, the ‘I’, ‘We’, and ‘It’ (both singular and plural), in a Venn diagram, the Ofman model is able to display the interconnection between these more clearly.

By employing the Ofman model to conceptualise relational sensitivity, an emphasise in the literature can be seen on the ‘We’ dimension, focused on examining relationships, interactions, and dynamics. Where the ‘I’ perspective is elucidated, it is in relation to its interconnectedness in shaping relationships, dynamics, and processes. Additionally, the ‘It’ dimension is examined in relation to intersubjective dynamics and individual experiences and attitudes. Through the Ofman model, relational sensitivity can be understood as ‘sensitivity to intersubjectivity’ (e.g. group- and power dynamics, worldviews, cultural differences, sensing affect and emotions, shared values, collective orientation), ‘sensitivity to the self’ and how it is part of forming relationships and processes (e.g. through embodied awareness, awareness of one’s ways of being and doing, and awareness of one’s positionality), and ‘sensitivity to materiality and processes’ and how it is part of shaping relationships and individual experiences (e.g. through tools, methods, and body postures). further shows the array of concepts and examples from the literature review that are connected to these perspectives, that highlight the nuances of relational sensitivity.

Table 4. Examples of relational sensitivity.

This conceptualisation of relational sensitivity shares similarities with ‘poise’ and ‘punctuation’, primarily emphasising the ‘I’ and ‘We’ dimensions. However, it expands upon these concepts by incorporating the ‘It’ perspective, highlighting the significance and interconnection of materiality, particularly in relation to tools in PD, with the subjective and intersubjective dimensions.

It is important to note that this conceptualisation of relational sensitivity is not intended as an all-encompassing framework, but rather an expansion of ‘poise’ and ‘punctuation’, aimed at enhancing the readiness of PD practitioners. Alternative models may be more useful to explore other pertinent aspects in PD, such as political structures or historical perspectives. Furthermore, as design practices evolve and vary across contexts (Redström Citation2017), different concepts and aspects may be relevant in specific contexts, leading to the evolution of the conceptualisation of relational sensitivity.

6.2. Whose relational sensitivity?

While the literature review did not specifically target practitioners’ relational sensitivity, the findings indicate a predominant focus on practitioners, including design researchers, designers, and facilitators. The concepts and aspects discussed in the literature relate to practitioners’ ability to attune to and respond to group dynamics, their awareness of different worldviews and the role of the body in power dynamics, and their self-awareness and embodied awareness. There are limited references to participants, except for discussions on participants’ embodied awareness (Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016) and their collective orientation and intersubjective awareness when contributing to the emergent PD processes (Agid and Chin Citation2019; Akama and Light Citation2018; Bratteteig and Stolterman Citation1997; Hakio and Mattelmäki Citation2019; Shaw Citation2010).

The emphasis on practitioners underscores the importance of their development of specific sensitivities and awareness towards collaborative dynamics. However, it also highlights a potential avenue for future research to explore and deepen the understanding of participants’ relational sensitivity and its role in PD processes. For example, Simonsen and Jensen (Citation2016) stress the significance of participants’ relational sensitivity, particularly embodied awareness, in identifying and expressing their genuine interests within a PD process. While Simonsen and Jensen’s existing data (Simonsen and Jensen Citation2016) primarily focuses on practitioners’ embodied awareness rather than the participants’, the lack of research on participants’ relational sensitivity presents an opportunity for further exploration. This could also be significant for researching intersubjective dynamics which requires multiple points of views (Détienne, Baker, and Burkhardt Citation2012).

7. Conclusion

This article presents a literature review and theoretical frameworks to articulate and exemplify relational sensitivity. By employing the Wilber (Citation2000) or Ofman (Citation2013) model, collaborative dynamics could be explored through a holistic perspective, to reflect on how the tangible and observable interrelate with the intangible and unobservable. The Ofman model, furthermore, clarifies the interrelatedness of the ‘I’, ‘We’, and ‘It’ perspectives. In applying Ofman’s model, this research distinguishes between three overarching perspectives on relational sensitivity: ‘sensitivity to intersubjectivity’; ‘sensitivity to the self’ and how it is part of forming relationships and processes; as well as, ‘sensitivity to materiality and processes’ and how it is part of shaping relationships and individual experiences. Additionally, the article provides diverse examples illustrating the nuances of these perspectives of relational sensitivity. Overall, the aim is to contribute to exploring responsible, or respons-able, PD practices that prioritise caring for and responding to the relationships within the process. The article contends that articulating relational sensitivity is an important aspect to fostering awareness of subtle and complex collaborative dynamics. These articulations could further inform the training needed to enhance such readiness.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Co-design reviewers for their insights that greatly contributed to the refinement of this article. Additionally, I extend my gratitude to Jennie Schaeffer, Anna-Lena Carlsson, Yvonne Eriksson, and Åsa Ståhl for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agid, S., and E. Chin. 2019. “Making and Negotiating Value: Design and Collaboration with Community Led Groups.” CoDesign 15 (1): 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1563191.

- Akama, Y. 2015. “Being Awake to Ma: Designing the Between-Ness as a Way of Becoming with.” CoDesign 11 (3–4): 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1081243.

- Akama, Y. 2017. “Surrendering to the Ocean: Practices of Mindfulness and Presence in Designing.” In Routledge Handbook for Sustainable Design, edited by R. B. Egenhoefer, 12. London: Routledge .

- Akama, Y., D. Evans, S. Keen, F. McMillan, M. McMillan, and P. West. 2017. “Designing Digital and Creative Scaffolds to Strengthen Indigenous Nations: Being Wiradjuri by Practising Sovereignty.” Digital Creativity 28 (1): 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2017.1291525.

- Akama, Y., P. Hagen, and D. Whaanga-Schollum. 2019. “Problematizing Replicable Design to Practice Respectful, Reciprocal, and Relational Co-Designing with Indigenous People.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1571306.

- Akama, Y., and A. Light. 2018. “Practices of Readiness: Punctuation, Poise and the Contingencies of Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers – Volume 1. PDC ’18: Participatory Design Conference 2018, 1–12. Hasselt and Genk Belgium: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210586.3210594.

- Akama, Y., and A. Light. 2020. “Readiness for Contingency: Punctuation, Poise, and Co-Design.” CoDesign 16 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1722177.

- Andersen, P. V. K., and W. S. Mosleh. 2021. “Conflicts in Co-Design: Engaging with Tangible Artefacts in Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration.” CoDesign 17 (4): 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1740279.

- Balaam, M., Comber, R., Clarke, RE., Windlin, C., Ståhl, A., Höök, K., Fitzpatrick, G., et al. 2019. “Emotion Work in Experience-Centred Design.” Paper presented at CHI 2019, May 4–9.

- Barcham, M. 2021. “Towards a Radically Inclusive Design – Indigenous Story-Telling as Codesign Methodology.” CoDesign 19 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1982989.

- Bellini, R., A. Strohmayer, P. Olivier, and C. Crivellaro. 2019. “Mapping the Margins: Navigating the Ecologies of Domestic Violence Service Provision.” In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ’19: May 4–9, Glasgow, Scotland, 122. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Binder, T., G. De Michelis, P. Ehn, G. Jacucci, P. Linde, and I. Wagner. 2011. Design Things. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

- Branco, R. M., J. Quental, and Ó. Ribeiro. 2017. “Personalised Participation: An Approach to Involve People with Dementia and Their Families in a Participatory Design Project.” CoDesign 13 (2): 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1310903.

- Bratteteig, T., and E. Stolterman. 1997. “Design in Groups—And All That Jazz.” Computers and Design in Context 289–315.

- Bustamante Duarte, A. M., M. Ataei, A. Degbelo, N. Brendel, and C. Kray. 2021. “Safe Spaces in Participatory Design with Young Forced Migrants.” CoDesign 17 (2): 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1654523.

- Buur, J., and H. Larsen. 2010. “The Quality of Conversations in Participatory Innovation.” CoDesign 6 (3): 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2010.533185.

- Clarke, R. E., J. Briggs, A. Armstrong, A. MacDonald, J. Vines, E. Flynn, and K. Salt. 2019. “Socio-Materiality of Trust: Co-Design with a Resource Limited Community Organisation.” CoDesign 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1631349.

- Del Gaudio, C., C. Franzato, and A. Jefferson de Oliveira. 2020. “Co-Design for Democratising and Its Risks for Democracy.” CoDesign 16 (3): 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1557693.

- Détienne, F., M. Baker, and J.-M. Burkhardt. 2012. “Quality of Collaboration in Design Meetings: Methodological Reflexions.” CoDesign 8 (4): 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.729063.

- Devos, T., and M. Loopmans. 2021. “Stimulating Embodied Intersubjectivities: Two Participatory Experiments in Antwerp North, Belgium.” CoDesign 18 (3): 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1894179.

- Dindler, C., and O. S. Iversen. 2014. “Relational Expertise in Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference on Research Papers – PDC’14, 41–50. Windhoek, Namibia: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2661435.2661452.

- DiSalvo, C., A. Clement, and V. Pipek. 2013.“Communities – Participatory Design for, with and by communities. In Routledge Handbook of Participatory Design.” edited by J. Simonsen and T. Robertson, 28. 1st ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315625508.

- Ehret, C., and T. Hollett. 2016. “Affective Dimensions of Participatory Design Research in Informal Learning Environments: Placemaking, Belonging, and Correspondence.” Cognition & Instruction 34 (3): 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2016.1169815.

- Gottlieb, L. 2022. “Relational Sensitivity and Participatory Practice: Exploring Poise and Punctuation Through an Empirical Study.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022 –Volume 2, 186–190. Newcastle upon Tyne: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3537797.3537872.

- Gottlieb, L. 2023. “Relational Sensitivity in Participatory Design: Thinking and making together through joint inquiry.” PhD Thesis, Mälardalen University Press.

- Hakio, K., and T. Mattelmäki. 2019. “Future Skills of Design for Sustainability: An Awareness-Based Co-Creation Approach.” Sustainability 11 (19): 5247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195247.

- Halskov, K., and P. Dalsgaard. 2007. “The Emergence of Ideas: The Interplay Between Sources of Inspiration and Emerging Design Concepts.” CoDesign 3 (4): 185–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701607404.

- Ho, D. K.-L., J. Ma, and Y. Lee. 2011. “Empathy @ Design Research: A Phenomenological Study on Young People Experiencing Participatory Design for Social Inclusion.” CoDesign 7 (2): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2011.609893.

- Iversen, O. S., K. Halskov, and T. W. Leong. 2012. “Values-Led Participatory Design.” CoDesign 8 (2–3): 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672575.

- Kelly, J. 2019. “Towards Ethical Principles for Participatory Design Practice.” CoDesign 15 (4): 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1502324.

- Light, A. 2015. “Troubling Futures: Can Participatory Design Research Provide a Constitutive Anthropology for the 21st Century?” IxD&a 26 (26): 81–94. https://doi.org/10.55612/s-5002-026-005.

- Light, A. 2019. “Design and Social Innovation at the Margins: Finding and Making Cultures of Plurality.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1567985.

- Light, A., and Y. Akama. 2012. “The Human Touch: Participatory Practice and the Role of Facilitation in Designing with Communities.” In Proceedings of the 12th Participatory Design Conference on Research Papers: Volume 1 – PDC’12, 61. Roskilde, Denmark: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2347635.2347645.

- Light, A., and Y. Akama. 2014. “Structuring Future Social Relations: The Politics of Care in Participatory Practice.” In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference on Research Papers – PDC’14, 151–160. Windhoek, Namibia: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2661435.2661438.

- Malinverni, L., and N. Pares. 2016. “An Autoethnographic Approach to Guide Situated Ethical Decisions in Participatory Design with Teenagers.” Interacting with Computers. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iww031.

- Manzini, E. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

- Mosely, G., L. Markauskaite, and C. Wrigley. 2021. “Design Facilitation: A Critical Review of Conceptualisations and Constructs.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 42:100962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100962.

- Mosleh, W. S., and H. Larsen. 2021. “Exploring the Complexity of Participation.” CoDesign 17 (4): 454–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1789172.

- Ofman, D. 2013. Core Qualities and the Core Quadrant. The Hague: Core quality international.

- Petrella, V., J. Yee, and R. E. Clarke. 2020. Mutuality and Reciprocity: Foregrounding Relationships in Design and Social Innovation. Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2020.177.

- Pitt, C., and K. Davis. 2017. “Designing Together?: Group Dynamics in Participatory Digital Badge Design with Teens.” In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 322–327. Stanford California: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3078072.3079716.

- Ramírez Galleguillos, M. L., A. Eloiriachi, and A. Coşkun. 2022. “Beneath Walls and Naked Souls: Factors Influencing Intercultural Meaningful Social Interactions in Public Places of Istanbul.” In Participatory Design Conference 2022: Volume 1, 194–205. Newcastle upon Tyne: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3536169.3537793.

- Redström, J. 2017. Making Design Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sandman, H., T. Meguid, and J. Levänen. 2020. “Unboxing Empathy: Reflecting on Architectural Design for Maternal Health.” CoDesign 18 (2): 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1833935.

- Shaw, B. G. 2010. “A Cognitive Account of Collective Emergence in Design.” CoDesign 6 (4): 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2010.533184.

- Simonsen, J., and O. S. Jensen. 2016. “Contact Quality in Participation: A “Sensethic” Perspective.” In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference Aarhus, Denmark: ACM Press, 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/2948076.2948084.

- Spiel, K., E. Brulé, C. Frauenberger, G. Bailley, and G. Fitzpatrick. 2020. “In the Details: The Micro-Ethics of Negotiations and in-Situ Judgements in Participatory Design with Marginalised Children.” CoDesign 16 (1): 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1722174.

- Spiel, K., E. Brulé, C. Frauenberger, G. Bailly, and G. Fitzpatrick. 2018. “Micro-Ethics for Participatory Design with Marginalised Children.” In Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference, Hasselt and Genk Belgium, 1–12. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210586.3210603.

- Steen, M. 2013. “Virtues in Participatory Design: Cooperation, Curiosity, Creativity, Empowerment and Reflexivity.” Science and Engineering Ethics 19 (3): 945–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-012-9380-9.

- St John, N., and Y. Akama. 2022. “Reimagining Co-Design on Country as a Relational and Transformational Practice.” CoDesign 18 (1): 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.2001536.

- Taoka, Y., K. Kagohashi, and C. Mougenot. 2021. “A Cross-Cultural Study of Co-Design: The Impact of Power Distance on Group Dynamics in Japan.” CoDesign 17 (1): 22–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1546321.

- Taylor, J. L., A. S. Wujal Wujal Council, and M. Brereton. 2022. “Tangible ‘Design Non-Proposals’ for Relationship Building in Community-Based Co-Design Projects.” In Participatory Design Conference 2022: Volume 1, 63–74. Newcastle upon Tyne: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3536169.3537780.

- Tenenberg, J., D. Socha, and W.-M. Roth. 2016. “Seeing Design Stances.” CoDesign 12 (1–2): 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1127386.

- Tjahja, C., and J. Yee. 2022. “Being a Sociable Designer: Reimagining the Role of Designers in Social Innovation.” CoDesign 18 (1): 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.2021244.

- Van Mechelen, M., M. Gielen, V. Vanden Abeele, A. Laenen, and B. Zaman. 2014. “Exploring Challenging Group Dynamics in Participatory Design with Children.” In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 269–272. Aarhus Denmark: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2593968.2610469.

- Wilber, K. 2000. A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality. Boulder Colorado: Shambhala Publications.

- Wilson, C., and K. Morrissey. 2022. “Modalities of Participation: Designing Beyond the Verbal.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022 – Volume 2, 63–69. Newcastle upon Tyne: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3537797.3537812.

- Zamenopoulos, T., B. Lam, K. Alexiou, M. Kelemen, S. De Sousa, and M. Phillips. 2021. “Types, Obstacles and Sources of Empowerment in Co-Design: The Role of Shared Material Objects and Processes.” CoDesign 17 (2): 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1605383.

- Zhang, M., D. Ji, and X. Chen. 2022. “Building Trust in Participatory Design to Promote Relational Network for Social Innovation.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022 – Volume 2, 94–102. Newcastle upon Tyne: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3537797.3537817.