Abstract

Background:

Feeding difficulties and subsequent malnutrition are common in children with cerebral palsy (CP).

Objectives:

A study was undertaken to determine the current practices and challenges of South African registered dietitians (SA RD) regarding the nutritional management of children with CP, to compare these practices with international guidelines and to compare the practices of private- and public-sector dietitians.

Design:

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study with an analytical component.

Subjects and outcome measures:

The SA RDs completed an online questionnaire, which was developed according to the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) guidelines. Participant answers were scored to assess their management of children with CP.

Results:

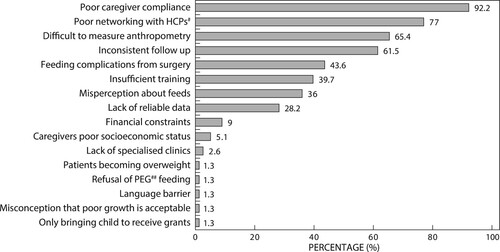

Of the 87 SA RDs who participated, 78 had work experience in CP (40 public and 38 private sector). Over two-thirds (n = 62/87, 71.2%) received training on the management of CP at university, albeit inadequate (n = 42/62, 67.7%). Common challenges that affect RDs’ management are poor caregiver compliance (n = 72; 92.2%) and poor networking between healthcare professionals (HCPs) (n = 60; 77.0%). The SA RD (n = 78) management of children with CP was significantly different from the ESPGHAN guidelines (p < 0.001). When comparing the total practice score, no significant difference was found between private- and public-sector RDs. The SA RDs did not achieve many of the recommended practices, particularly those pertaining to anthropometry.

Conclusions:

Improved training of SA RDs in the assessment and management of children with CP, and addressing barriers such as poor caregiver compliance, would enhance SA RDs’ competence to improve the nutritional management of children with CP.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common physical disability in childhood.Citation1 CP is caused by an injury to the brain or due to abnormal development of the maturing brain.Citation2 There is limited information available on South African (SA) statistics, yet the latest data describe the prevalence of children with CP in SA (0.3–1%) as higher than the global statistic (0.21%).Citation3,Citation4

Children with CP are at risk of malnutrition, faltering growth and nutritional comorbidities due to many factors including feeding difficulties and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.Citation5 Adequate nutritional management is vital to prevent the onset of malnutrition and its consequences for poor development and health.Citation6 Children who are well nourished and able to feed adequately have a better quality of life both functionally and physically.Citation6

Caregiver challenges in feeding their children with CP have been examined in the literature. Common challenges are feeding problems, which include vomiting, choking, prolonged mealtimes and constipation.Citation7 Concerns over these feeding difficulties can significantly decrease the quality of life of both caregiver and child.Citation8

There is a paucity of data on how children with CP are managed nutritionally in SA, as well as the barriers faced by registered dietitians (RDs) to provide their best care. SA studies found that feeding problems in children with CP were not adequately addressed because less than half of children in need of nutritional advice were referred to RDs.Citation9,Citation10 Similar studiesCitation11,Citation12 from the UK and Saudi Arabia have described how RDs who were part of a multidisciplinary team were more likely to use best dietetic practicesCitation12 and receive more referrals.Citation11 Very few RDsCitation11,Citation12 included a variety of anthropometric measurements, including skinfold thickness, to assess nutritional status, which is important for children with CP.Citation13 Lack of trainingCitation11,Citation12 and timeCitation11 have contributed to this gap in practice. As there are no specific SA guidelines on how to manage these children nutritionally, the international guidelines compiled by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN)Citation13 () are a valuable resource for SA RDs.

The aims of this study were: (i) to describe the current practice of SA RDs regarding the nutritional management of children with CP in SA; (ii) to compare these practices with international guidelines; (iii) to compare the practices of private and public sector SA RDs; and, finally, (iv) to identify the challenges and barriers faced by SA RDs in providing optimal nutritional care to children with CP. The findings and recommendations from this study will provide insight into the practices of SA RDs and how these compare with international guidelines, with the aim of improving the nutritional status of these vulnerable children.

Methods

Study population and design

A cross-sectional descriptive study, which included an analytical component, was conducted. The study population was defined as all SA RDs who are involved in the nutritional care of children in SA. Such data were obtained from the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA), the Association of Dietetics in South Africa (ADSA), Medpages (an African database of healthcare contact information) and 72 provincial SA hospitals. The population of RDs who manage CP patients was estimated as N = 209, consisting of 112 RDs in the private sector and 97 RDs in the public sector. All members of the study population were invited to participate.

To test the null hypothesis that the practices of private- and public-sector RDs are equal, the required sample size for each group was calculated at 64. However, due to no further responses after reminder advertisements of the study were sent, once a sample size of 40 public and 38 private sector RDs was reached, interim analysis revealed that the minimum difference of clinical importance (10%) had not been achieved and further sample collection was discontinued.

Methods

An online survey was electronically sent between March and May 2019 to all members of the Association for Dietetics in South Africa (ADSA) via an ADSA newsletter. Additionally, RDs were contacted electronically after compiling a database of paediatric RDs utilising Medpages and lists of CP clinics. Reminder emails were sent out again after the first invitation to increase the response rate.

Research instrument

The research instrument was a questionnaire incorporated into an online survey using the web-based program SurveyMonkey. This questionnaire was developed based on the latest published guidelines on the nutritional care of children with CP by ESPGHANCitation13 and included those guidelines pertaining to dietetic management. It comprised two sections. The first section included six demographic questions, which were answered by all RDs. The second section continued for RDs who regularly managed children with CP, comprising 26 questions (5 dichotomous, 13 multiple choice and 8 open-ended questions) on aspects of nutritional care for children with CP. The questions in the second section were designed to assess whether the RD’s management of children with CP followed the recommended practices described in the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines. The questionnaire was used to assess the RD’s adherence to 28 such guidelines. For each guideline that the RD followed, they scored one point out of a possible 28 points. A total practice score was calculated out of 28 and expressed as a percentage. The total practice percentages of all SA RDs were compared with the ESPGHAN guidelines. Additionally, the total practice percentages of the public-sector RDs were compared with the private-sector RDs.

Content validity was established by the review of two experts in paediatric nutrition and on the grounds that the questionnaire was developed from guidelines compiled by ESPGHAN,Citation13 which is an authoritative body as all information is derived from scientific evidence. A pilot study was used to determine face validity. Final-year dietetic students were chosen for this purpose as they had theoretical knowledge of the nutritional management of children with CP and thus could provide meaningful input concerning the clarity of questions. They evaluated the procedure of answering and submitting the electronic survey. Five students volunteered and provided feedback, which helped to clarify the instructions to complete the survey and resulted in the aim of the study being explained more clearly. Registered dietitians were not chosen to be part of the pilot study because the pool of paediatric RDs is small and if they took part in the pilot study they would not be eligible to participate in the study.

Data analysis

Data from the survey were imported from SurveyMonkey in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and analysed using the statistical package IBM SPSS®, version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were prepared for statistical analysis by means of coding. Responses to open-ended questions were categorised into familiar themes. The RDs’ responses were scored on 28 guidelines (referred to as a total practice score) from the ESPGHANCitation13 recommendations and a percentage was calculated, which indicated the degree to which these guidelines were achieved ().

Two null hypotheses were tested. The first hypothesis was that there was no difference between the mean total practice scores of the population of SA RDs in the study and the expected score of 100% practice of the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines. The mean total practice score of all the RDs were compared with a score of 100% representing the guidelines using the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test. The second hypothesis was that there was no difference in mean total practice scores between the private and public RDs. The mean total practice score of public and private practicing RDs were compared using the two-sided, two-sample equal-variance Mann–Whitney U test. Individual items were compared between independent groups using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. A p-value < 0.05 indicated a significant difference between the two groups in all tests.

Ethics

This study was granted ethics approval by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University (HREC Ref: S18/08/170) and was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided informed consent by agreeing voluntarily to participate in the study before gaining access to the survey. The survey was anonymous and confidential because responses cannot be linked to any participant.

Results

Ninety-three RDs consented to participate; however, 87 completed the questionnaire and were included in the study. The mean age of the RDs was 33.8 years (SD ± 6.9), the median years of dietetic experience was 10 years (range = 1–28) and 7 of the 9 SA provinces were represented. Over two-thirds (n = 62/87, 71.3%) had received training on the management of CP at university but the majority (n = 42/62, 67.7%) felt the training was inadequate ( and ).

Table 1: Summary of personal information of South African registered dietitians with an interest in paediatrics (N = 87).

Table 2: Provinces where South African registered dietitians reside and universities attended (N = 87)

Seventy-eight (78/87, 90.0%) RDs had work experience in CP management (40 public-sector and 38 private-sector RDs) (). The ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines used in the questionnaire are presented in . The guidelines performed by most RDs were in identifying undernutrition (guidelines 6 and 7) (n = 73, 93.6%) and correctly including early feeding history as part of assessment (guideline 9) (n = 74, 94.9%), while the least performed guideline was the anthropometric guidelines for measuring fat mass (guidelines 4 and 5) (n = 4, 5.1%). Although 39.7% (n = 31) used standard growth curves (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] as well as World Health Organisation child growth standards [WHO]) (guideline 10), many RDs used a combination of growth curves for assessment. Public-sector RDs performed significantly more of the guidelines than private-sector RDs by being part of a multidisciplinary team involving more than one other healthcare profession (guideline 1) (p = 0.009). Private-sector RDs performed significantly better than public-sector RDs on the guidelines, which recommend regular micronutrient assessment (guideline 11) (p = 0.002), estimating energy (guideline 12) (p = 0.011) and micronutrient requirements (guideline 14) (p = 0.043), prescribing supplementary protein in specific circumstances (guideline 15) (p = 0.003) and the trial use of whey-based formula in gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) (guideline 21) (p = 0.001) ().

Table 3: Achievement of the selected ESPGHAN## guidelines by South African registered dietitians, public-sector and private-sector dietitians and p-values of the tests# comparing the two sectors

The nutritional assessments during follow-up visits were carried out by a lower percentage of RDs compared with nutritional assessments done during the first assessment. The measurement of triceps skinfold thickness (TST) for the determination of body fat (which is a requirement of the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines) was the least used method, changing from 9.0% for the first evaluation to 1.3% at the 12-month evaluation. Those RDs who investigated micronutrient status mostly considered iron, vitamin D and calcium while 23.1% did not consider any micronutrients. Clinical signs of malnutrition were not specifically defined but at least 50% of the RDs consistently monitored clinical signs ().

Table 4: Percentage of registered dietitians (n = 78) who perform nutritional assessments of children with cerebral palsy at various intervals

A significant difference was found between the total practice score of the SA RDs and the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines. The median total practice score of the total group (n = 78) was 60.7% (IQR 53.6%, 67.9%) (one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test = −7.683, p < 0.001). Conversely, the median total practice score of the public-sector dietitians (n = 40) and private-sector dietitians (n = 38) showed no difference (57.1% [IQR 51.8%, 67.9%] and 60.7% [IQR 57.1%, 71.4%] respectively) (independent-samples Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.090).

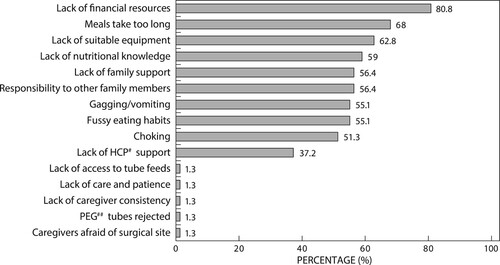

The SA RDs were posed open-ended questions to describe their challenges when managing children with CP () as well as their observations of the challenges that caregivers face when caring for their children with CP (). The most common challenges faced by SA RDs include poor caregiver compliance (92.2%), poor networking between SA RDs and other HCPs (77.0%), difficulty in measuring anthropometry (65.4%) and inconsistent follow-up (61.5%) ().

Figure 1: Challenges registered dietitians (n = 78) face when managing children with cerebral palsy.

Note: # Health care professional; ## Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Figure 2: Challenges registered dietitians (n = 78) perceive caregivers face when supporting their children with cerebral palsy nutritionally.

Note: # Health care professional; ## Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Additionally, SA RDs perceived that caregivers faced many challenges when supporting their children with CP. Lack of financial resources (80.8%) was perceived as the most common obstacle, followed by meals taking too long to consume (68.0%), lack of suitable equipment to prepare the food (62.8%) and a lack of nutritional knowledge (59.0%). Feeding difficulties (gagging and vomiting [55.1%], fussy eating [55.1%] and choking [51.3%]) during meals were also perceived as challenges ().

Discussion and recommendations

This research aimed to determine the practices and challenges of SA RDs regarding the nutritional management of children with CP. These practices were compared with international guidelines,Citation13 and the practices of private- and public-sector SA RDs were also compared. The study found that SA RDs successfully achieved certain practices such as managing patients as part of a multidisciplinary team and initiating enteral feeding appropriately but fell short of the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines, particularly in anthropometric assessment. In total, the practices of publicly and privately practicing SA RDs were similar. Additionally, SA RDs are faced with many obstacles that impede their ability to succeed.

Nutritional assessment

The anthropometric assessment of children with CP is challenging because weight and height measurements can be unreliable due to their physical attributes. Additionally, these children may be shorter and have reduced lean body mass and higher fat mass compared with typically developed children,Citation13,Citation14,Citation15 possibly resulting in an incorrect interpretation of a body mass index (BMI) or z-score.Citation15 For this reason, fat mass and fat-free mass using TST is a more reliable indicator of malnutrition in this population group.Citation16 Very few (5%) SA RDs complied with this practice, and previous studies attributed it to lack of time and appropriate training.Citation11,Citation12 The use of alternative segmental length measures (e.g. knee height or tibial length) when linear height is not possible was not well practised by SA RDs, possibly due to absence of the specialised equipment required for accurate measurement. Additionally, the follow-up of children with CP, which should be six monthly, was not well achieved in this study, possibly due to the logistical problems highlighted by RDs as three out of five SA RDs reported that follow-up appointments were inconsistent.

Standard growth charts like the WHO growth curves are recommended by ESPGHANCitation13 to monitor growth in children with CP because CP-specific growth charts, which were developed to account for the altered growth pattern often found in these children, show how children with CP are growing but not necessarily how they should grow.Citation13 In this study, just over a third of SA RDs complied with this practice. Additionally, SA RDs use a combination of growth charts to assess their patients, possibly due to the wide spectrum of CP patients they manage and the conflicting approaches in the literature. For instance, a Mexican studyCitation17 found that CP-specific charts were a better reference for children with CP than the standard CDC charts.

Macro- and micronutrient requirements in children with CP are recommended in the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines to be the same as for neurotypical children, and individualised regular monitoring of bodyweight and fat composition to fine tune energy requirements is emphasised. The lack of follow-up appointments, which has been highlighted as a challenge by SA RDs, and their failure to take body fat measurements prevent this recommendation from being followed. The SA RDs use a variety of methods to calculate energy requirements, probably due to the vast spectrum of severity of this condition.Citation6 Six out of 10 SA RDs prescribed protein according to DRIs, while less than half increased protein requirements in accordance with the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines, which recommend an increase in the presence of pressure ulcers and when the energy requirement is reduced. The importance of annual micronutrient monitoringCitation13 (e.g. vitamin D, iron, calcium and phosphorus) is highlighted in the literature to correct deficits in these patients. While the majority of SA RDs did not regularly assess micronutrient deficiencies, those SA RDs who were concerned mostly considered iron, vitamin D and calcium. In this instance, RDs in Saudi Arabia set the example as almost all their RDs habitually test micronutrient status.Citation12

Nutritional management

Dysphagia, GOR and constipation have been highlighted in the literature as the most significant gastrointestinal conditions that can affect feeding in children with CP.Citation13 Even though dysphagia has been widely described in up to 90% of all children with CPCitation18, just over a third of SA RDs do not consider the possibility of dysphagia in all their patients. Similarly, the prevalence of GOR and constipation have been reported in up to 70% and 74% of children with CP respectively.Citation18 The ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines’ approach to treating constipation is the same as for neurotypical children and is appropriately managed by the majority of SA RDs (80%). Half the SA RDs prescribed probiotics yet this is not included in the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines. A recent review (2020) concluded that although probiotics have a positive effect on the intestinal habitat, there is no benefit on constipation.Citation19

The ESPGHANCitation13 guideline to initiate enteral feeding only when oral feeding is unsafe, nutritionally inadequate, stressful and prolongedCitation13 was observed by almost all SA RDs. The guidelines provide recommendations to use certain feeds for four different groups of patients.Citation13 In this study SA RDs complied with the recommendation to use breast milk, formula or energy-dense infant formula as indicated for infants as well as high-energy feeds for those who are volume restricted. Only one-fifth of SA RDs used the suggested feed for children over one year, namely a standard polymeric feed with fibre. Most chose fibre-free feeds, possibly due to the higher cost of fibre feeds. The recommended use of low-energy feeds with fibre for immobile patients was followed by less than one-fifth of SA RDs. As this type of feed is not commercially available in SA, RDs are faced with adjusting feeds based on what the patient can afford and on what feeds are available, without compromising their patient’s nutritional management.

Although the null hypothesis comparing the practices of public- and private-sector SA RDs showed no significant difference in their overall management of children with CP, some individual guidelines differed significantly. The differences in practice are probably in part because these sectors have different structures in SA. The public sector has separate departmentsCitation20 that provide allied healthcare services, which include occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy and dietetics, allowing better networking between the HCPs. The public sector also operates within the confines of standard protocolsCitation21 and a strict budget, while the private sector practises with more management and financial flexibility.

Challenges identified by South African registered dietitians

Unfortunately, most SA RDs face challenges that limit optimal nutritional care. Poor caregiver compliance was reported by almost all SA RDs. Literature shows that families of children with CP may report their practices inaccurately for fear of being judged, to seek approval or to receive compensation,Citation22 while others overestimate the food consumed as they overlook spillage and vomiting.Citation18 Compliance may be affected by their children’s feeding difficultiesCitation23 or the caregivers’ education level, language and cultural barriers.Citation22,Citation23 Research shows that non-compliance by caregivers of children who had gastrostomy feeding was due to many barriers perceived by caregivers, including the confirmation of permanence of the disability, fearing discrimination from others and the loss of the nurturing maternal experience of feeding their child orally.Citation24

Proper nutritional care is further impeded by insufficient networking between SA RDs and other HCPs. The accomplishment of more than 8 out of 10 SA RDs engaging in an interdisciplinary approach when managing children with CP has been described as beneficialCitation13 as this leads to the referral of more patients and better dietetic practices.Citation11,Citation12 Findings from this study are higher than from previous studies reporting that 6 out of 10 dietitians worked as part of a multidisciplinary team including doctors, occupational therapists, speech therapists and physiotherapists.Citation11,Citation12 Perplexingly, despite SA RDs’ involvement in a team, this study showed that more than two-thirds found networking with other HCPs unsatisfactory. Based on findings in the current literature, RDs may enhance networking with HCPs by using web-based networks to improve transparency and quality of care.Citation25,Citation26

The most common challenge SA RDs identified with which caregivers struggle regarding the nutritional care of their children was a lack of financial resources. The cost of living is substantial for people with disabilities as the caregiver needs to provide the basic needs as well as the additional costs needed to care for their disabled childCitation27 including medical care and therapy, and specialised equipment. In the developing world, this burden falls almost entirely on the family.Citation28 Mealtime challenges are well documented and include meals taking too long and being stressful because of the child’s feeding difficulties due to poor eating and drinking ability, which can cause coughing, vomiting, gagging, drooling and food refusal.Citation8,Citation28 These challenges highlight the importance of including the guidance of other HCPs to improve the nutritional management of these children. SA RDs’ perception that caregivers struggle with lack of support from their families and from HCPs is aligned with findings from an African systematic reviewCitation29 that children with CP have limited access to healthcare facilities and HCPs. Furthermore, caregivers are unhappy with the lack of information regarding diagnoses, and its impact on the child and their family.Citation30

Recommendations

Improved and updated teaching at tertiary institutions is pivotal to advance the nutritional management of children with CP. The undergraduate dietetic curriculum needs to cover concepts of the prevention and recognition of malnutrition in children with CP as highlighted in this study, multidisciplinary care and early intervention across all levels of health care in SA. Additionally, the curricula of all disciplines relevant to the management of children with CP (including medicine, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech therapy) should recognise the importance of interprofessional education and collaborative practice (IPECP) to enhance a holistic approach for the care of children with CP. A unique set of SA nutritional guidelines should be formulated, based on the SA environment and resources, and taking these ESPGHANCitation13 recommendations into account. An affordable and appropriate low-calorie, complete paediatric feed rich in fibre should be made available for children with low energy needs.

Limitations

Sample bias may exist due to the small sample size. Data received were on reported practice and not actual practice. The facilities available to the RDs were not taken into consideration. Use of an electronic survey does not allow for probing questions to clarify findings. It is beyond the scope of this study to provide solutions to the problems identified.

Conclusion

Compared with the ESPGHANCitation13 guidelines, although certain practices were well achieved, there were gaps in SA RDs’ nutritional management of children with CP, particularly pertaining to anthropometry. The overall practice of publicly and privately practising SA RDs was comparable, apart from a few individual guidelines (being part of a multidisciplinary team, estimating and monitoring certain requirements and the management of GOR) that could be attributed to their different working environments. This study highlights the many challenges SA RDs face that impede the best possible care available to these vulnerable children. It is important to understand and resolve these concerns, which include poor compliance, poor networking with other HCPs and difficulties with measuring anthropometry. Caregivers also need to withstand many obstacles when caring for their children, including financial constraints and difficulties with feeding. Since this study was a descriptive account of the practices of SA RDs, it is suggested that a qualitative study be carried out to determine how to improve current practices by exploring in-depth reasons why certain practices are carried out and how to elevate them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data and Statistics for Cerebral Palsy. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html.

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007;109:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.tb12610.x

- Oskoui M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, et al. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:509–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12080

- Murugasen S. A systematic review of cerebral palsy in African paediatric population [unpublished dissertation]. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 2022. https://scholar.sun.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/e7077e3e-6ce7-42d5-814d-9b9f1408a704/content

- Romano C, Dipasquale V, Gottrand F, et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in children with neurological disability. Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2018;60:892–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13921

- Marchand V, Motil KJ. NASPGHAN committee on nutrition. nutrition support for neurologically impaired children: a clinical report of the north American society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:123–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mpg.0000228124.93841.ea

- Marques JM, Sa LO. Feeding a child with cerebral palsy: parents’ difficulties. J Nurs Referência. 2016;4(11):11–19. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV16041

- Donkor CM, Lee J, Lelijveld N, et al. Improving nutritional status of children with cerebral palsy: a qualitative study of caregiver experiences and community-based training in Ghana. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;7:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.788

- Barratt J, Ogle V. Recorded incidence and management of dysphagia in an outpatient paediatric neurodevelopmental clinic. SAJCH. 2010;4(2):38–41. https://sajch.org.za/index.php/SAJCH/article/view/223/171.

- Lourens L. Nutrition-related concerns of the primary caregiver regarding children with spastic cerebral palsy [unpublished dissertation]. Potchefstroom: North-West University; 2016. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/25516

- Hartley H, Thomas JE. Current practice in the management of children with cerebral palsy: a national survey of paediatric dietitians. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2003;16:219–224. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00452.x

- Almajwal AM. Dietetics practices for nutritional management of children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia among the practicing dietitians. Can J Clin Nutr. 2019;7(2):7–26. https://doi.org/10.14206/canad.j.clin.nutr.2019.02.02

- Romano C, van Wynckel M, Hulst J, et al. European society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of gastrointestinal and nutritional complications in children with neurological impairment. JPGN. 2017;65(2):242–264. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001646

- Gurka MJ, Kuperminc MN, Busby MG, et al. Assessment and correction of skinfold thickness equations in estimating body fat in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:e35–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03474.x

- Finbraten AK, Martins C, Andersen GL, et al. Assessment of body composition in children with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional study in Norway. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57:858–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12752

- Samson-Fang LJ, Stevenson RD. Identification of malnutrition in children with cerebral palsy: poor performance of weight-for-height centiles. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:162–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0012162200000293

- Vinals-Labanino CP, Velazquez-Bustamante AE, Vargas-Santiago SI, et al. Usefulness of cerebral palsy curves in Mexican patients: A cross-sectional study. J Child Neurol. 2019;34(6):332–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073819830560

- Trivic I, Hojsak I. Evaluation and treatment of malnutrition and associated gastrointestinal complications in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019;22(2):122–131. https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2019.22.2.122

- Gomes DOVS, Morais MB. Gut microbiota and the use of probiotics in constipation in children and adolescents: systematic review. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2020;38:e2018123), https://doi.org/10.1590/19840462/2020/38/2018123

- Parker W, Steyn NP, Mchiza Z, et al. Dietitians in South Africa require more competencies in public health nutrition and management to address the nutritional needs of South Africans. Ethn Dis. 2013;23(1):87–94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23495628/.

- National Department of Health. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for South Africa. Hospital Level, Paediatrics; 2017. http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/standard-treatment-guidelines-and-essential-medicines-list.

- Gibson RS, Charrondiere UR, Winnie B. Measurement errors in dietary assessment using self-reported 24-hour recalls in low-income countries and strategies for their prevention. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:980–91. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.117.016980

- Polack S, Adams M, O’Banion D, et al. Children with cerebral palsy in Ghana: malnutrition, feeding challenges, and caregiver quality of life. Dev Med and Child Neuro. 2018;60:914–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13797

- Petersen MC, Kedia S, Davis P, et al. Eating and feeding are not the same: caregivers’ perceptions of gastrostomy feeding for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:713–717. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0012162206001538

- Gulmans J. Crossing boundaries: improving communication in cerebral palsy care. Int J Inter Care. 2012;12:855–856. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.855

- Brown BB, Patel C, McInnes E, et al. The effectiveness of clinical networks in improving quality of care and patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1615-z

- Diseko TN. Experiences of caregivers caring for children with cerebral palsy in mahalapye, Botswana. Masters dissertation. University of Pretoria, 2017. https://hdl.handle.net/2263/60355

- Adams MS, Khan NZ, Begum SA, et al. Feeding difficulties in children with cerebral palsy: low-cost caregiver training in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Child: Care Health Dev. 2011;38(6):878–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01327.x

- Donald KA, Samia P, Kakooza-Mwesige A, et al. Pediatric cerebral palsy in Africa: A systematic review. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2014;21:30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2014.01.001

- Reid A, Imrie H, Brouwer E, et al. ‘If I knew then what I know now’: parents’ reflections on raising a child with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2011;31(2):169–183. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2010.540311