ABSTRACT

The article provides a historical analysis of the evolution of ‘Peacekeeping-Intelligence’ (PKI) as a UN intelligence system and tool of conflict management. It examines the processes leading to the development of the PKI Policy by analyzing the analytical entities that cumulatively contextualized these developments. It also examines the institutional mechanisms at the UNHQ, the underlying logic, and the challenges surrounding these processes. The article first traces the various iterations of information and analysis structures within the UN since the early 1960s. It then focuses on intelligence developments in the 1990s and the new millennium, where the lack of intelligence capabilities, particularly at the mission level, was identified as an underlining factor for the operational problems faced by the UN. It concludes with an examination of the PKI policy as an evolutionary step in UN peacekeeping. The paper argues that PKI offers a new pathway to effective peacekeeping and provides a foundation for enhanced decision-making through situational awareness, the safety and security of peacekeepers, and the protection of civilians.

Introduction

Over the past six decades, peacekeeping has become the mainstay of United Nations (UN) activities and ‘one of the most visible symbols of the UN role in international peace and security.’Footnote1 The geo-political and normative context of peacekeeping has evolved considerably, and so too has the conception of the use of intelligence. Peacekeepers operate in complex environments where there is little or no peace to keep and are required to be robust and assertive in implementing mandates. From its early establishment, intelligence was deemed as incompatible with the UN’s values and normative principles. Despite the criticality of intelligence to mission success, the UN has historically been reluctant in its use due to conceptual issues and deep-rooted structural challenges of integrating intelligence into a multilateral institution. These controversies are borne out of the notion of intelligence as a secret and an intrusive tool that undermines the idea that peacekeepers intervene in conflicts as a symbol that reflects the collective goodwill of the UN.Footnote2 However, the nature of conflicts has changed considerably since the new millennium and challenged this narrative.Footnote3 Paul Johnston has argued that effective intelligence could be used within UN operations despite the political sensitivities.Footnote4 Similarly, Bassey Ekpe argued that despite its restrictions, the UN needs intelligence for planning and implementation of its missions.Footnote5 Alex Bellamy and Adam Lupel identified that the continuous failure of the UN to prevent atrocities pointed to the inability to translate and analyse data that could lead to ‘actionable early warnings,’ and the limited capabilities available to missions to ‘gather and analyse accurate intelligence.’Footnote6 Arguably, the sentiments expressed by a senior UN official involved in the development of relevant intelligence policies in assessing the UN-intelligence conundrum provides context:

What is even worse is, we deploy Member States’ nationals. When Member States deploy the exact same personnel in the national context, they give them intelligence. But when they are deploying the exact same people with the blue helmets, they say ‘no intelligence.’ So, you want to protect them here, but not there? How does it work? It is incredible that we are an organisation that employs roughly 120,000 uniformed personnel, more than any single organisation or country and we are the only organisation deploying all these people that are restricted in using intelligence.Footnote7

The UN’s position on the use of intelligence has gradually shifted over the past few years. Several iterations of structures and entities were developed at both the strategic and mission level in search of an intelligence system that is fit-for-purpose. In Resolution 1894 (2009), the Security Council emphasized the need to give ‘priority in decisions about the use of available capacity and resources, including information and intelligence resources, in the implementation of mandates for the protection of civilians.’Footnote8 For instance, in 2012, following an escalating situation in Mali, the UN called on Members to provide ‘intelligence capacity’ to support its operations in Mali.Footnote9 Intelligence, which was once deemed as a ‘dirty word’Footnote10 has now come to be regarded as ‘as a “critical enabler” to permit missions to operate safely and effectively.’Footnote11

It has been argued that ‘intelligence’ has always been a part of peacekeeping.Footnote12 Nevertheless, the UN did not acknowledge it as a key component due to its political sensitivity and the lack of consensus among Member States. On 26 May 2017, following several months of extensive consultations at the UNHQ with the field, and with Member States, the then Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO)Footnote13 and Department of Field Support (DFS) issued a code cable disseminating the Peacekeeping-Intelligence (PKI)Footnote14 Policy to all missions.Footnote15 The policy is to ‘ … be adapted and applied flexibly to respond to specific needs in each mission environment.’Footnote16 The PKI policy was aimed at supporting the operations and activities of peacekeeping missions in the field, either during the initial planning phase of a mission or during the mission’s lifecycle.Footnote17 This step represents an evolution in the theory and practice of peacekeeping and a desire to extend the peacekeeping and intelligence boundaries.

Intelligence within the context of the UN and peacekeeping operations provides a valuable context to understanding the international dimension of intelligence. Though the intelligence studies field has expanded since the 1970s,Footnote18 its focus has primarily been on intelligence as a fundamental element of statecraft.Footnote19 The intelligence literature has mainly presented the national dimension of intelligence as a tool to project power in furtherance of the self-interest of states.Footnote20 Don Munton and Karima Fredj, and Stephen Lander put it succinctly as ‘good intelligence is, like adequate military capability, an instrument of state power,’Footnote21 and that ‘intelligence services and intelligence collection are at heart manifestations of individual state power and of national self-interest.’Footnote22 The literature on the international aspect of intelligence has focused primarily on intelligence-sharing, cooperation, and liaison agreements at the state-to-state level as a form of alliance.Footnote23 A wave of scholars emerged since the mid-1990s that have explored the complexity of the use of intelligence within the UN, both at the strategic and mission level.Footnote24 Other scholars examined how technological solutions, machine learning and big data could enhance data analysis systems for conflict prevention, humanitarian action, development, and peacekeeping.Footnote25 John Karlsrud calls this ‘the fourth-generation peacekeeping’ or ‘Peacekeeping 4.0.’Footnote26 Walter Dorn also refers to this as ‘Smart Peacekeeping,’ a ‘network-enabled’ or ‘network-centric’ peacekeeping that thrives on digital and technological solutions.Footnote27

However, the question of the historical context and evolution of intelligence in the UN, and what it means for contemporary peacekeeping theory and practice remain unexplored. This article examines the evolution of PKI as part of UN conflict management. The focus is on the institutional developments at both the UNHQ and the field that all together shaped the emergence of the novel PKI Policy. It argues that the factors that constrained the use of intelligence in contemporary peacekeeping operations have their roots in the early development of the UN and the essence of intelligence as a strategic tool of statecraft. The article presents an historical analysis of the efforts towards developing intelligence entities within the UN, the processes undertaken, the underlying logic, and related challenges surrounding these processes.

The article first traces the various iterations of information and analysis structures since the early 1960s when the need for intelligence was identified in UN peacekeeping. The second part focuses on intelligence developments in the 1990s, an era where the UN entered with high hopes and optimism for peacekeeping but encountered several ‘failures’ in areas such as Somalia, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia, where the lack of intelligence capabilities was identified as an underlining factor. The third part looks at peacekeeping in the new millennium and how the need for better situational awareness within missions led to the creation of multidimensional analytical entities to chart the path for the use of intelligence. The final part examines the PKI policy as an evolutionary step in UN peacekeeping and as a new approach to addressing the UN-intelligence conundrum. The article argues that PKI offers a new pathway to effective peacekeeping and provides a foundation for enhanced decision-making through situational awareness, the safety and security of peacekeepers, and the protection of civilians.

Intelligence developments in the formative years

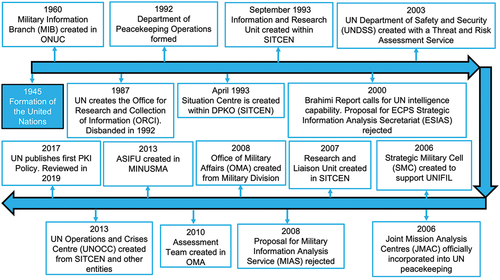

The UN has struggled over the course of its history to develop an intelligence culture along with the requisite architecture and organisational structures to provide active and timely intelligence support to decision-making and operations.Footnote28 Member states have traditionally resisted several efforts to develop UN intelligence capabilities. Since peacekeeping operations continue to be conducted in increasingly volatile situations, Member States have accepted that a greater intelligence capacity is required for force protection and to effectively implement their mandates.Footnote29 Over the past four to six decades, the UN adopted different approaches and a plethora of structures to utilise intelligence, albeit with mixed results. The UN intelligence developments occurred in a non-linear and incoherent fashion.Footnote30 shows a timeline schematic of the UN’s journey towards developing intelligence capabilities.

Footnote31Early developments in the 1960s: The Pioneering Military Intelligence Branch (MIB)

From the early years of the UN, the organisation did not establish any form of intelligence-gathering and analysis entity, a condition which the second Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, viewed as a ‘serious handicap.’Footnote32 Dag Hammarskjöld requested for the UN to develop a system of early warning capabilities to ensure a pre-emptive approach to conflict prevention.Footnote33 However, he rejected the development of an ‘intelligence’ capability arguing that the UN must have ‘clean hands.’Footnote34 The UK had proposed for the creation of a ‘Military Staff for the UN Secretariat’ composed of ‘intelligence staff’ to provide ‘the study of situations wherein the United Nations Organisation might become militarily involved, and to prepare contingency plans for these circumstances.’Footnote35 However, the UN did not assent to such an entity for political reasons. The first real UN-intelligence test occurred during the UN mission in the Congo (ONUC) in 1960.Footnote36 The intelligence system that was later instituted was described at the time as ‘UN’s first dedicated intelligence-gathering unit’Footnote37 and the ‘most comprehensive intelligence support structures in any UN peace operation.’Footnote38 From the onset, there was disagreement between ONUC’s military and civilian leadership and the UN Secretariat resulting from ambivalence over the role of intelligence.Footnote39

Secretary-General Hammarskjöld decided that ONUC could not conduct any intelligence operation of the kind employed by national intelligence agencies, even though he acknowledged the limitations posed by the lack of an intelligence capability.Footnote40 The outbreak of the Congo civil war and the deteriorating situation in 1961 exposed the limitations resulting from the lack of an intelligence machinery in the mission. Accordingly, in February 1961, ONUC’s mandate was extended to include peace enforcement and the Military Information Branch (MIB) was created to provide comprehensive intelligence support to the mission.Footnote41 The MIB’s intelligence system employed wireless message interception, photographic intelligence using airplanes and aerial surveillance, and human intelligence.Footnote42 To mitigate the apprehension emanating from the term ‘intelligence’, the UN called the branch military ‘information’ as opposed to ‘intelligence’ branch.Footnote43

Though ONUC’s MIB developed an extensive intelligence-gathering machinery, it encountered some challenges. First, the management of intelligence within the mission lacked a coherent and a systematic approach thereby minimising the level of integration. This was coupled with the limited size and resources which impeded its ability to control the intelligence situation (initially the MIB had only nine officers). Also, the staff lacked the language skills and intelligence training in addition to the limited technical intelligence capability of the branch.Footnote44 The frequent turnover of staff affected the development of a systematic intelligence structure and institutional memory, while there was a lack of coordination with the operations branch.

Indeed, subsequent analysis will demonstrate that some of these challenges that impeded the MIB’s effectiveness persist in the management of PKI today, particularly the limited resources, the high turnover of staff, lack of coordination and the problem of integration. A significant asset was the counterintelligence section. Though all studies on the MIB did not provide details of the counterintelligence tasks they performed, it is believed that the desk was created to prevent the activities of hostile elements against the intelligence-gathering efforts of the MIB. As a pioneering UN intelligence machinery, the MIB had the potential to serve as a prototype peacekeeping ‘intelligence’ capability for future operations.Footnote45 However, the UN was unable to immediately consolidate the gains of the MIB. Subsequent operations possessed limited military information elements that performed operational reporting without a coherent mission-wide intelligence entity.Footnote46

The Office of Research and Collection of Information (ORCI)

The lack of systematic intelligence capabilities persisted throughout the 1960s until the late 1980s when the UN took concrete steps to ameliorate the situation. Recognising the early warning and predictive gaps, Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar created the Office for Research and Collection of Information (ORCI) within the Office of Special Political Affairs at the UN Headquarters. The ORCI provided assessments of global trends, strategic analysis of various countries, regions, and conflicts, early warning of potential and emerging situations, and monitoring of humanitarian crises and emergencies.Footnote47 It was the first ‘serious’ attempt at ‘early warning’ and ‘strategic analysis’ at the UN Secretariat.Footnote48

The ORCI was designed as a strategic hub for coordinating all information-gathering and analysis among UN agencies.Footnote49 However, it suffered from the lack of information flow due to bureaucratic bottlenecks as most departments were unwilling to share information.Footnote50 It was also severely under resourced in terms of its personnel, which meant it could not conduct in-depth analysis of emerging international issues.Footnote51 Dorn explains that despite the ORCI having an early warning section, it did not issue any significant early warning throughout its existence.Footnote52 Also, the persistent requests for speech writing by the then Secretary-General and senior UN officials impeded the ORCI from carrying out strategic analysis of global events required of its mandate.Footnote53

The biggest obstacle was the political setback that effectively limited its ability function and to obtain adequate resources. The US, Britain and France supported the creation of the office to detach the task of a daily press summaries from the Political Information News Service (PINS) of the Department of Political and Security Council Affairs (DPSCA). This was due to suspicion of strong Soviet influence in the PINS.Footnote54 However, some US politicians opposed the ORCI on the basis that it might provide a cover for Soviet espionage in the US. It was alleged that the ORCI would ‘gather information on the internal political situation of member states, a definite UN intrusion into domestic affairs.’Footnote55 The US subsequently blocked funds to the office, thereby limiting its influence and relevance.Footnote56 Though some of the concerns raised by the US were allayed, the tactic of UN Member States deliberately limiting the efforts to develop intelligence capacity of the UN prevailed and eventually led to the disbandment of the ORCI in 1992. The critical function of strategic warning based on systematic intelligence-gathering and analysis remained a lacking capability at the UN Secretariat for most part of the 1990s.

Agenda for Peace and Intelligence Developments in the 1990s

The post-Cold War era saw a renewed optimism for UN peacekeeping resulting in an exponential increase in the number of peacekeeping operations in the 1990s.Footnote57 The new layer of complexity in peacekeeping re-ignited the UN-intelligence debates following several episodes of failures in Somalia, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia. In all these cases, the lack of intelligence was identified as a contributing factor.Footnote58 When Boutros Boutros-Ghali assumed office as UN Secretary-General in 1992, it became apparent very early in his tenure that peacekeeping was quickly becoming the centrepiece of the UN’s response to international conflict in the post-Cold War era.

The Agenda for Peace was launched among other things to strengthen peacekeeping in the face of evolving conflict situations.Footnote59 The report underscored the need for an ‘Early Warning’ system. The DPKO was subsequently created to strengthen the management and administration of the growing number of peacekeeping operations, paving the way for the development of information-gathering and analysis entities.

Monitoring, analysis and reporting: the situation centre (SITCEN) model

As a first step in the post-Brahimi report, the SITCEN was created in April 1993 as part of the recommendations for information and analysis functions in the Agenda for Peace. It was situated within the DPKO to provide a systematic information network and a 24/7 link between UN headquarters, the field, other UN agencies, and Member States through their diplomatic missions. It was tasked to produce strategic assessments of political, military and security trends for both current and future peacekeeping operations.Footnote60 Though the SITCEN had a Research and Information unit that carried out information-gathering and analysis, it was not a ‘comprehensive intelligence unit.’Footnote61 However, the creation of the SITCEN demonstrated a realisation and firm commitment within the UN to expand its information-gathering and analysis capabilities.Footnote62

It was envisaged that the SITCEN would be equipped to provide a holistic assessment of developments in peacekeeping ranging from political, security, military, police, and humanitarian issues.Footnote63 Dorn explained that the SITCEN’s capacity was more than a ‘cable room’ but was short of a ‘nerve centre for command and control used in national defence establishments.’Footnote64 The SITCEN served as the interface and communication link between the UNHQ and the missions.Footnote65 Indeed, at the height of UN peacekeeping in the mid-1990s, ‘the sun never set on UN peacekeepers.’Footnote66 Though the SITCEN was not identified as an intelligence unit, a command centre, or a ‘war room,’ it systematised data to develop a wider assessment of conflict and peacekeeping trends to facilitate planning and decision-making.Footnote67 Its primary focus was monitoring and coordinating information from field missions and disseminating to related departments.Footnote68

Despite the SITCEN’s role in providing information about current operations, it did not avert the lack of comprehensive analysis and assessment capacity to serve the policymakers both within the UN and Member States.Footnote69 The SITCEN was incorporated into the newly created UN Operations and Crises Centre (UNOCC) in January 2013. However, the process of integration at that level and the specific requirement for a ‘strategic intelligence capability’ remains limited at the UNHQ. Currently, the UNOCC serves as an innovative hub for a system-wide information management and incident reporting.Footnote70 It has developed a clear set of procedures for information collection and reporting from the field, UNOCC entities, and at the UN Headquarters. It has been innovative in broadening its scope from its modest structure that was inherited from the SITCEN to an entity that is able to mobilise a wide range of agencies, expertise, and perspectives across the UN system. Among the UNOCC’s key contributions is the management and backstopping of the Joint Mission Analysis Centres (JMACs) and the Joint Operations Centres (JOCs) at the mission-level. As will be seen in subsequent analysis, the UNOCC has also provided a forum for a coordinated crises response across peacekeeping missions by streamlining the information gathering and reporting channels, policies, and guidelines. Missions like the United Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) and the erstwhile United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) under the guidance of the UNOCC developed relevant policies and mechanisms that interfaced the missions with the UNOCC in daily reporting and coordinating crises response.Footnote71

Strategic intelligence and the Information and Research (I&R) Unit

To expand the predictive capability of the UN for better analysis of underlying conflicts, the then DPKO needed an extensive intelligence network that could draw from multiple sources, including from national intelligence agencies.Footnote72 The major powers agreed to provide the UN with intelligence to support its missions which led to the creation of the Information and Research (I&R) Unit within the SITCEN in September 1993. The I&R Unit represented the first ‘complete’ UN strategic intelligence capability.Footnote73 The Unit provided analysis of the motivations of conflicting parties, prepared strategic threat assessments, and strategic forecasts of potential and imminent conflicts. It possessed the greatest ‘reach’ in terms of information collection and analysis due to its direct connection with national intelligence systems of the P5 members. One of the distinguishing features that shaped the work of the I&R Unit was the massive support of the ‘great powers,’ the US, France, Russia, and the UK who availed their intelligence, personnel, and resources to the unit.Footnote74

The I&R Unit was granted access to state-of-the-art systems that enhanced its information-gathering, analysis, and dissemination, including technological systems such as the US computer-based system called the Joint Deployable Intelligence Support System (JDISS). The JDISS was a system that provided cutting-edge analytical software and database that could interface with compatible national intelligence databases.Footnote75 However, these raised concerns that the US could manipulate UN decision-making by using selective and biased information.Footnote76 A factor that contributed significantly to the I&R Unit’s demise was its structural design. It consisted of only officers seconded from four of the P5 members. This raised concerns over bias towards the interests of the most powerful states.Footnote77 The officers retained links to the national intelligence agencies of their home countries from where they provided intelligence feeds to the UN. The lack of diversity in its composition created a lot of political tension. In the late 1990s, the UN decided to phase out the gratisFootnote78 officers from the UN HQ. The move was politically motivated by many developing countries and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).Footnote79 These states resented the over-representation of Western states in the DPKO. The General Assembly eventually passed a resolution that phased out the use of gratis personnel citing financial reasons and geographical imbalance.Footnote80

In February 1999, the staff of the I&R Unit were replaced by civilians and the unit was transformed into a resource centre.Footnote81 The very essence of the I&R unit was lost, and no alternative capacity replaced the unit.Footnote82 The I&R Unit, though another failed UN intelligence move, proved that intelligence was an extremely useful resource to UN’s peacekeeping project. Indeed, evidence showed how it provided useful intelligence to support UN operations in the 1990s.Footnote83 It demonstrated the potential of what could be achieved within the multilateral intelligence-sharing sphere.

The new millennium and UN Intelligence Developments

The new millennium witnessed unparalleled innovation in UN’s intelligence drive and charted a new path towards achieving an ‘intelligence-compliant’ UN. While some of the initiatives, particularly at the strategic level faced the same political resistance and thus failed to garner the support of Member States, the mission level efforts received significant support.

A ‘CIA for the UN’? Dilemma of UN strategic analysis

The need for a comprehensive UN information-gathering and analysis system was reflected in the Brahimi Report in two ways. First, the report recommended that UN peace operations ‘should be afforded the field intelligence and other capabilities needed to mount a defence against violent challenges.’Footnote84 The explicit use of the word ‘intelligence’ suggested that the traditional aversion to the use of intelligence in the UN was changing. Second, the report cited the lack of a professionalised system of information-gathering, analysis, and dissemination as part of conflict management.Footnote85

The Secretariat attempted to address this lacuna by developing strategic intelligence capabilities at the Secretariat and subsequent mechanisms at the field level. However, the deep-rooted mistrust and brewing political tension derailed any potential for the UN to expand its analytical capabilities. As a first step in the post-Brahimi reforms, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan proposed for the establishment of the Strategic Information and Analysis Secretariat within the Executive Committee on Peace and Security (ECPS). This was called the ECPS Strategic Information and Analysis Secretariat (ESIAS) and was to be an amalgamation of the SITCEN, and other policy planning and analysis units at the UN Secretariat. The mandate was to provide strategic analysis on peace and security issues, formulating long-term strategies and to warn UN leadership of emerging threat.Footnote86 Chesterman explained that the EISAS faced sudden death as soon as it was unofficially referred to as a ‘CIA for the UN.’Footnote87 The ESIAS proposal raised serious concerns among Member States as it was feared that it would be a vehicle through which the national intelligence agencies of selected countries would penetrate the UN.Footnote88 There were also concerns that the analysis of risks of internal conflict by a ‘UN-intelligence agency’ would be a justification for military intervention in internal affairs of Member States, especially developing countries, which could potentially harm their sovereignty.Footnote89

There was also the conceptual problem of what constituted ‘strategic analysis,’ ‘information-gathering,’ vis á vis espionage and intelligence as well as the difference between ‘strategic intelligence’ versus ‘tactical intelligence.’Footnote90 These concerns fed into the broader narrative that any form of ‘intelligence’ organisation within the UN was undesirable. The ESIAS proposal reignited a long-standing suspicion that some Member States often use the Secretariat as a conduit for their intelligence activities against other states. The UN was already dealing with allegations of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s role in espionage in Iraq through the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM).Footnote91 These tainted the UN’s credibility and ‘neutral’ position. Consequently, Member States, especially the NAM, resisted the establishment of the EISAS and the proposal was not implemented.Footnote92 The ESIAS had the potential to consolidate strategic analysis within the UN which could have enhanced the UN’s analytical and predictive capabilities. However, the lack of consensus and mistrusts continued to undermine efforts towards developing a UN intelligence system.

The Strategic Military Cell (SMC)

Another significant development was the creation of the Strategic Military Cell (SMC) at the Secretariat following the 34-day War between Israel and Hezbollah in July 2006. It was created to strengthen the Military Division [later called Office of Military Affairs (OMA)] and to provide strategic analysis, policy and planning, and command and control to support the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in 2006.Footnote93 The SMC was composed of military staff from the main Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) in UNIFIL, particularly Italy, France, and Spain, supported by personnel from members of the P5. It worked closely with the SITCEN regarding analysis on UNIFIL where it was co-located to facilitate coordination and information-flow.Footnote94

Despite the innovative concept of the SMC which improved the oversight, coordination, information-sharing, and management of UNIFIL, it faced criticisms.Footnote95 Its exclusive focus on UNIFIL, with substantial allocation of resources, was regarded as too much for a mission that was not classified at the time as ‘complex.’Footnote96 It was also seen as selective, lacked diversity, pro-Western and an ad hoc step to please the Europeans. From the perspective of the Secretariat, it was a condition for the contribution of European nations to UNIFIL.Footnote97 The SMC project was completed in 2010, however, its legacy was laying the foundation towards the development of a military analysis capacity at the OMA.

The failed attempt to establish the Military Information Analysis Service (MIAS)

With the planned dissolution of the SMC, the UN requested to establish a strategic analysis unit to fill the capacity gap that was created. A joint study led by the OMA in 2008 proposed the establishment of a Military Information Analysis Service (MIAS) modelled along the concept of the SMC to provide detailed analysis of the military situation in operational theatres and on threats to current and future operations.Footnote98 It was to increase the strategic analytical capacity of the UN to ensure force protection of troops in the field, enhance management of crisis response, and improve planning to facilitate decision-making.Footnote99 Despite its operational ‘appeal,’ the MIAS model was rejected. The Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ) of the General Assembly voted against it, citing that the analogy to national military strategic headquarters was deemed ‘not relevant to the OMA’ and that the MIAS was ‘excessively complicated.’Footnote100

The failure of this proposal was a consequence of the aversion to the use of intelligence and the political mistrust that continued to brew among Member States at the time. An alternative entity was later created in 2008 called the Assessment Team (AT). The designation of ‘Assessment Team’ was deemed more acceptable among members of the General Assembly’s Fifth Committee, particularly among the NAM countries much more than the ‘Military Information Service’ as proposed by the Secretariat. Footnote101 Indeed, Colonel Sam, who is the current Chief of the AT stated that:

The nomenclature ‘Assessment Team’ can be misleading. Assessment is so broad that everyone puts a different interpretation to it. What we do is military strategic threat assessment. The designation of ‘Assessment’ Team is creating problems for the work of the AT; it is open to varied interpretation. For instance, people often perceive that the team assesses the performance of missions and peacekeepers.Footnote102

A senior UN official explained that the role performed by the AT did not differ significantly from that of the MIAS.Footnote103 Currently, the AT, which is located within the OMA, provides analytical support to DPO. It is the primary military peacekeeping-intelligence entity at the UN Secretariat. The AT’s analytical products such as Annual Threat Forecast, Intelligence Summaries (INTSUM) and Threat Analysis Reports are used by the senior leadership of the OMA in their advisory role to the Under Secretary-General of the DPO. The AT has potential (like the I&R Unit) in terms of personnel and expertiseFootnote104 to drive strategic analysis should the UN overcome the resistance to ‘strategic intelligence.’ However, it does not have a mandate for such a function, and thus, focuses its expertise on providing information analysis rather than strategic intelligence.

Compromise and necessity: the progress of mission-level intelligence

The lack of intelligence-gathering and analysis capability in the UN, particularly at the field level persisted in the early 2000s as the situation began to expose weaknesses in peacekeeping. The Security Council was keen in intervening in conflicts through the deployment of peacekeeping forces. This placed greater demands for a coordinated system of information management. The idea of ‘robust’ peacekeeping emerged prominently in the 2000s as the UN carried out multidimensional operations in Sierra Leone, Congo, and Haiti. These missions doctrinally changed the passive posture of peacekeepers that characterised the failures of Rwanda and Bosnia and Herzegovina.Footnote105 Consequently, new ‘intelligence’ structures needed to be developed for mission level analysis. These growing demands led to the introduction of the JMAC. The JMAC was proposed in 2005 to provide analytical support to peacekeeping. It was implemented alongside the JOC which primarily serves as a reporting hub.Footnote106 The JMAC was first piloted in Liberia, Afghanistan, Sudan, the DRC, and Haiti.Footnote107 In 2006, the JMACs were officially promulgated to provide mission-wide analytical support at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of DPKO missions. To strengthen the integration of JMACs, the DPKO and DFS published relevant supporting policies and guidelines.Footnote108 The development of these ground-breaking policies, is further evidence of the progress made by entities such as the UNOCC in streamlining strategic analysis and reporting within the UN, both at the UNHQ and the field missions.

A unique feature of the JMAC model is its integrated approach. It is composed of military, police, and civilians.Footnote109 The JMAC, as a multidisciplinary entity, is required to provide analysis that reflects the broad range of expertise available in multidimensional missions and produce balanced, timely and systematically verified mission-specific information.Footnote110 The JMACs operate with the concept of multi-source analysis. It draws from a broad range of sources and institutions based on which it conducts its medium- to long-term analysis.Footnote111 Since the concept of the JMAC was developed for the operational level and limited within a specific geographical space, and so long as its activities were focused on ongoing operations, it gained traction and support from Member States.Footnote112 The JMAC’s utility and value have been proven in many missions. For instance, in Haiti, the JMAC provided timely intelligence to support operations against the criminal gangs.Footnote113 Duursma explained that the JMAC in Darfur provided useful information that helped the mission leadership to take proactive steps to avert some conflicts.Footnote114

The JMAC’s data collection is also described as the most comprehensive and precise than any other form of conflict data analysis.Footnote115 Despite the JMAC’s utility, it has faced some challenges with integration.Footnote116 The relationship between the JMAC and military intelligence branches have soured in some missions in some time periods like MINUSCA, MINUSMA, and UNMISS mainly due to clash of roles, turf battles, staffing issues, and the desire for influence.Footnote117 These challenges have persisted and reflect the deep organisational cultural challenges within the UN that impedes coordination and information-sharing. The implementation of the PKI policy, which is discussed later, offers an opportunity to drive the process of mission level intelligence integration.

The All-Sources Information Fusion Unit (ASIFU)

The early 2010s placed UN peacekeeping in uncharted territory, forcing several analysts to suggest that UN peacekeeping was moving towards counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.Footnote118 The threat level increased significantly in countries like the DR Congo, Mali, and Central Africa Republic where the mission environment was complicated by the growing terrorist threat and mass civilian casualties. Specifically, in 2012, the Secretariat called on Member States to help provide ‘intelligence capacity’ to MINUSMA.Footnote119 Subsequently, the Security Council authorised the Secretary-General to enhance ‘MINUSMA’s intelligence capacities, including surveillance and monitoring capacities.’Footnote120 In response, the ASIFU was created in January 2014. The ASIFU was a flagship intelligence capability that represented the biggest revolution in peacekeeping intelligence at the mission level since the MIB in 1960.

The creation of ASIFU was supported by several Western and European nations who contributed specialised intelligence capabilities to the unit.Footnote121 It was later merged into the military intelligence branch of MINUSMA in 2017. Allard Duursma explicates some of ASIFU’s actionable and integrated intelligence provided to MINUSMA using its extensive network of military assets that were tasked to gather intelligence.Footnote122 The ASIFU was equipped with high technology sensors, highly trained intelligence analysts, and advanced information technology, databases, and command systems. The unit was allocated substantial resources and extensive intelligence capabilities across spectrums such as human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), open-source intelligence (OSINT) and imagery intelligence (IMINT). This was a further development of the growing use of advanced technological tools, monitoring, and surveillance technologies such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) that shaped intelligence-gathering and analysis in UN peacekeeping since the UN first introduced drones in peacekeeping in 2013.Footnote123

At the outset, the ASIFU operated as a distinct entity from the existing mission analytical structures.Footnote124 The separation created internal tensions within MINUSMA’s information management system, especially because the ASIFU’s secured channel of communications restricted the dissemination of its products. The use of North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) systems (specifically the highly secure Dutch ‘TITAAN-Red’) and procedures made it difficult to share classified intelligence with non-NATO systems, including the UN.Footnote125 Though the ASIFU was a highly developed intelligence capacity, some argued that the idea of integrating such a high technology capacity within a low technology organisation like MINUSMA was problematic.Footnote126 The lack of compatibility between the ASIFU system and the rest of the mission created division between the military, humanitarian, and development aspect of peacekeeping, thereby, undermining the integrated approach.Footnote127 Within the mission, the lack of clarity over the ASIFU’s role, reporting lines and dissemination of their products further deepened the division between the mission’s intelligence structure.Footnote128 Other non-Western states viewed the ASIFU as an ‘exclusive club’ of the West to promote their intelligence-gathering effort in the Sahel region, further fuelling mistrust.Footnote129

Though it was short-lived, the ASIFU paved the way for stronger UN intelligence integration and the prospects for a future UN peacekeeping mechanism where an elaborate intelligence capability could be developed. The PKI policy was given a push by the ASIFU project. This was following an UN-led lessons learned team in December 2015 that studied the ASIFU and MINUSMA intelligence. The report recommended for a ‘policy’ framework on intelligence in peacekeeping operations.Footnote130

PKI policy: a new UN approach to intelligence

In 2016, the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations (C34) acknowledging the need to improve intelligence and analysis to enhance the safety and security of peacekeepers using modern technology and human-based information-gathering called on the Secretariat to ‘develop a more cohesive and integrated United Nations system for situational awareness … .’Footnote131 This call paved the way for the Secretariat to engage in broader consultation on the modalities and the development of an overarching policy framework to govern the use of intelligence in peacekeeping.Footnote132 The publication of the PKI Policy in 2017 was ground-breaking in UN’s long and arduous road towards intelligence integration. It was the first time the UN officially acknowledged in policy, a guidance document that authorised the specific use of ‘intelligence’.

The PKI policy was adopted by the Security Council and the General Assembly based on a recognition of the ‘need for improved situational awareness.’Footnote133 The strategy of consensus and extensive engagement used by the UN played a major part in moving PKI from being a mere rhetoric to actual implementation and a sense of ‘acceptance’ by Member States though it watered down the supposed UN-intelligence ‘doctrine’ to lowest common denominator. The PKI Policy has provided a firm foundation for the UN to adapt and develop an intelligence system that is ‘compatible’ with its needs without upsetting sensitivities.

Overcoming old troubles: pathway to a consensus-driven approach

One of the fundamental problems that impeded efforts towards developing a UN intelligence system was the lack of consensus among Member States due to mistrust and divergent views on what an ideal UN intelligence system entailed. To address this limitation, a series of studies by the UN on intelligence was concluded in early 2016.Footnote134 This formed the basis for broader engagements with the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations (C34) on the scope for the policy including the purpose and focus on mission-level operational requirements. Footnote135 Following the draft policy by the Secretariat, the Special Committee urged the Secretariat ‘to undertake close consultations with Member States, drawing on their views and legitimate concerns … ’Footnote136 Indeed, the C34 acknowledged that the:

[…] consultations have provided opportunities to understand and address the priorities and the concerns of Member States, contributing to a policy that will articulate a consistent and principled approach firmly grounded in United Nations values, including on the confidentiality and the protection of sources; the establishment of a robust oversight regime; and an effective whole-of-mission approach.Footnote137

As mentioned earlier, the deployment of the ASIFU in 2014 played a vital role and provided immediate impetus the policy to guide the UN’s approach to intelligence.Footnote138 The Peacekeeping-Intelligence Coordination Team (PICT) was subsequently created within the DPO to coordinate and manage the consultative process and operationalisation of the policy. The PKI Policy embodied the culmination of several efforts to address the challenges of developing an intelligence framework within the UN. It outlines how UN missions should gather, analyse disseminate, use, protect, and manage intelligence.Footnote139

The processes leading to the PKI Policy came with its challenges. There were internal divisions among the key UN departments and entities regarding the scope and the context. A senior UN official explained the tensions that accompanied the process to the extent that some departments ‘chose to sidestep the process or deliberately opted out of discussions.’Footnote140 The five key sections of the DPO involved in the process shared different views on the scope of the policy, the definition, and a conceptualisation of the UN’s approach to intelligence.Footnote141 Largely, drawing from the NATO experience in multidimensional missions, most European states acknowledged the value of an enhanced intelligence capability for UN peacekeeping operations, resulting in their support of the PKI policy.Footnote142 However, several Member States of the NAM, reignited the long-held suspicion of ‘undue’ Western influence in UN peacekeeping.Footnote143 With these concerns, the UN embarked on an ‘extensive’ consultation to solicit support, an approach that largely resulted in an appreciable degree of ‘success,’ compared to previous UN approaches. Indeed, a UN official acknowledged that ‘All Member States, including Russia, are on board with peacekeeping intelligence for safety and security of personnel.’Footnote144 The efforts of the PICT yielded results with the strong support the policy has received since it was first published.

The C34 has reaffirmed the policy and its 2019 revision including the principles, focus and implementation framework.Footnote145 One of the main issues that divided opinions during the development of the policy was agreeing the definition of ‘peacekeeping intelligence.’Footnote146 The definition presented in the 2017 PKI Policy was:

Peacekeeping intelligence is the non-clandestine acquisition and processing of information by a mission within a directed mission intelligence cycle to meet requirements for decision-making and to inform operations related to the safe and effective implementation of the Security Council mandate.Footnote147

The intent of the 2017 PKI Policy which emerged in discussions was that ‘PKI relates to all aspect[s] of the mission mandate.’Footnote148 However, some Member States raised concerns that the spirit of that definition gave the UN carte blanche, arguing that using PKI to support every aspect of the mandate would mean the UN could meddle in political intelligence that could harm its reputation.Footnote149 The revised version of the policy in 2019, therefore, eliminated the ‘definition’ and re-developed it into ‘principles.’Footnote150 Currently, there is no specific definition of PKI, however, the principles provide the overarching framework and rules for its application.Footnote151 While most Western states advocated for stronger multidimensional intelligence systems in the UN, members of the NAM, who have for several years resisted attempts by the UN to build intelligence structures, maintained their reservations about the intentions and motives of those European and NATO states.

Some experts argued that the debates reflected an ongoing geopolitical competition regarding the framing of key aspects of mandates such as the protection of civilians.Footnote152 However, this goes beyond the peacekeeping debates and reflects a long-standing suspicion and mistrust that have always surrounded the ‘intelligence’ discourse within the UN over the past seven decades. As debates progressed, a point of consensus, as outlined in the ‘areas of application in the policy,’ was that PKI was needed to ‘enhance situational awareness and the safety and security of UN personnel and to inform operations and activities related to the protection of civilians tasks of the Security Council mandates.’Footnote153 These were re-emphasised under the principle of PKI being ‘conducted within designated areas of application,’ to mitigate the risk of PKI being used for areas beyond the limits agreed by Member States. Footnote154 In principle, PKI is intended to serve three main purposes: (1) support a common operational picture; (2) provide early warning of imminent threats; and (3) identify risks and opportunities.Footnote155 These roles are linked to the normative understanding of intelligence.

Though PKI remains ‘vague’ within the policy, the UN has adopted the concept of a hyphen between ‘peacekeeping’ and ‘intelligence’ to distinguish UN intelligence from national intelligence. With PKI presented as a new concept, without a specific definition and only principles, Member States who resisted the efforts altered their stance and accepted the revised policy.Footnote156 In principle, the PKI activities are to be conducted in line with the Security Council mandates and in compliance with the UN Charter including the overall legal framework governing peacekeeping and legal and human rights standards. Secrecy and covert activities remain outside the scope of PKI. In previous missions such as ONUC, the UN did rely on some covert sources.Footnote157 However, the idea of PKI policy is to assuage any concerns of covert activities which undermine the values of the UN. The policy also emphasises the respect for state sovereignty including host nation and neighbouring states and that PKI should maintain its ‘exclusively international character’ and be independent of all aspects of any national intelligence system or other operations.Footnote158

The policy and its ‘acceptance’ by Member States suggests that intelligence has gained traction and paved the way for the progressive development of a comprehensive UN intelligence capability that is effective and fit-for-purpose. A significant benefit of the PKI policy and its acceptance is the area of training support.Footnote159 Some Member States such as Norway, The Netherlands, and Austria have funded PKI courses since 2017. Since the PKI Policy was developed, the UN has published other supporting framework documents such as the Military Peacekeeping-Intelligence Handbook (MPKI) (2019), Acquisition of Information from Human Sources for Peacekeeping-Intelligence (HPKI) (2020) and the Guidelines for United Nations Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Capabilities (2019). Other documents like the Police Peacekeeping-Intelligence, Peacekeeping-Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance Handbook (PKISR), and the Guidelines for Sharing Peacekeeping-Intelligence with and Receiving Intelligence from Non-UN and Non-Mission UN EntitiesFootnote160 are at various levels of development.Footnote161 The UN is certainly well-positioned to adapt to the current developments in the international security landscape through the utilisation of intelligence underpinned by the PKI policy.

Conclusion

This article has analysed the evolution of PKI as a novelty in UN intelligence system development situated within the broader shift in peacekeeping doctrine and practice. In tracing these developments that were non-linear and ad hoc, the paper examined the conditions under which specific entities were established, the structural designs, the challenges they encountered, and how they paved the way for the UN to develop the PKI Policy as an evolutionary step in its effort to utilise intelligence in peacekeeping. As demonstrated, the challenges had their roots in the early developments of the UN and the peacekeeping project. Peacekeeping today is conducted in complex environments where missions operate in increasingly volatile environments characterised by counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.

As peacekeeping evolved, the UN struggled to develop intelligence capabilities due to inherent mistrust and lack of consensus among Member States, coupled with the sensitivity of intelligence. Peacekeeping missions not only require information to know where and how to intervene but more importantly, a stronger intelligence collection and analytical capacity will help to better understand the political dynamics and to make appropriate decisions. The processes at the strategic level have continued to face resistance due to the level of mistrust and sensitivities surrounding the application of intelligence. The disbandment of entities like the ORCI and the I&R Unit, and the failure to establish mechanisms such as the ESIAS and MIAS created a vacuum in strategic analysis at the UNHQ. Nevertheless, these developments have cumulatively paved the way for the emergence of new entities such as the PICT, UNOCC and the AT that are contributing to information analysis, reporting and PKI management of mission level processes. More fundamentally, these processes were shaped by a deeper need for a consensus-driven approach towards a collective realisation of the need for a paradigm shift in UN’s approach to intelligence. This, indeed, has strengthened the UN’s ability to keep pace with current developments in peacekeeping.

The UN intelligence evolution saw the emergence of the PKI Policy in 2017 which provides an overarching strategic guidance to mission-level intelligence management. The policy has not been able to finalise a specific definition of intelligence, but it has provided a set of principles which underpin the UN’s use of intelligence. Beyond the publication of the PKI policy, the UN, practitioners, and scholars dedicated to understanding the unique UN-intelligence conundrum would need to shift attention to understanding how the PKI Policy has shaped and contributed to contemporary peacekeeping practice. The specific outcomes of the processes and implementation of the policy, particularly in specific mission cases, would provide an avenue to understand the impact of this intelligence evolution within the UN. Though the integration of PKI would remain a challenging venture, nevertheless, there is potential for developing stronger mechanisms for utilising intelligence as a force multiplier both at the strategic and mission level of the UN.

Special note

This paper is redacted from a thesis submitted by the author to the School of International Relations, University of St Andrews towards the award of a Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations.

Ethical approval

The research underpinning this study involved the conduct of field research using semi-structured face-to-face and virtual interviews of senior United Nations officials in New York. The fieldwork followed all required ethical guidelines and received ethical approval from the University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Committee (UTREC) and School of International Relations Ethics Committee, Approval Number IR14290 valid from 16 May 2019 to 16 May 2024. Informed consent was sought for the publication of interviews and the attributable name received the express permission of the interviewee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Patrick Peprah Obuobi

Patrick Peprah Obuobi is a serving Ghanaian senior military intelligence officer. He holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of St Andrews, a Master of Arts Degree in Intelligence and International Security from Kings College London, and a Bachelor of Science in Administration from the University of Ghana. Patrick is a graduate of the United States Army Intelligence Center and School, Fort Huachuca. He has served on several UN missions and was a Military Observer and Military Intelligence Analyst in MONUSCO in 2017. He received the prestigious British Government Chevening Scholarship in 2015 and the Commonwealth Scholarship in 2018.

Notes

1 Ramesh Thakur, The United Nations, Peace, and Security (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 37.

2 Sebastiaan Rietjens and Walter A. Dorn, “The Evolution of Peacekeeping Intelligence: The UN’s Laboratory in Mali,” in Perspectives on Military Intelligence from the First World War to Mali: Between Learning and Law, ed. Floribert Baudet et al. (The Netherlands, The Agues: T.M.C ASSER Press, 2017); Hugh Smith, “Intelligence and UN Peacekeeping,” Survival 36, no. 3 (1994): 174–92; David Ramsbotham, “Analysis and Assessment for Peacekeeping Operations,” Intelligence and National Security 10, no. 4 (1995): 162–74; Sebastiaan Rietjens and Erik de Waard, “UN Peacekeeping Intelligence: The ASIFU Experiment,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 30, no. 3 (2017): 532–56; Walter A. Dorn and David J.H. Bell, “Intelligence and Peacekeeping: The UN Operation in the Congo 1960–64,” International Peacekeeping 2, no. 1 (1995): 11–33; Walter A. Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters? The Information and Research Unit and the Intervention in Eastern Zaire (1996),” in Peacekeeping Intelligence: New Players, Extended Boundaries, ed. David Carment and Martin Rudner (Oxon: Routledge, 2006); Walter A. Dorn, “United Nations Peacekeeping Intelligence,” in Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, ed. Loch K. Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); and Allard Duursma and John Karlsrud, “Predictive Peacekeeping: Strengthening Predictive Analysis in UN Peace Operations,” Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 8, no. 1 (2019): 1–19.

3 Walter A. Dorn, “Intelligence at UN headquarters? The information and research unit and the intervention in Eastern Zaire 1996,” Intelligence and National Security 20, no. 3 (2005): 440–65; Dorn, “United Nations Peacekeeping Intelligence”; Simon Chesterman, “Does the UN have intelligence,” Survival 48, no. 3 (2006): 149–64; and Smith, “Intelligence and UN Peacekeeping.”

4 Johnston, “No cloak and dagger required: Intelligence support to UN peacekeeping,” Intelligence and National Security 12, no. 4 (1997): 102–12.

5 Ekpe, “The Intelligence Assets of the United Nations: Sources, Methods, and Implications,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 20, no. 3 (2007): 377–400.

6 Bellamy and Lupel, Why We Fail: Obstacles to the Effective Prevention of Mass Atrocities (New York: International Peace Institute, 2015), 1–2.

7 Interview with Senior UN Official, October 10, 2019.

8 United Nations, Resolution 1894 (2009) Adopted by the Security Council at its 6216th meeting, on 11 November 2009 S/RES/1894(2009), Security Council (New York, 2009), 5.

9 United Nations, Resolution 2227 (2015): Adopted by the Security Council at its 7474th meeting, on 29 June 2015 S/RES/2227 (2015), Security Council (New York: Security Council, 2015), para 16.

10 International Peace Academy, Peacekeeper’s Handbook. Pergamon (1984), 39.

11 United Nations, United Nations Peacekeeping Intelligence Policy, Ref. 2000707 (New York: UN DPKO/DFS, 2017), 2.

12 Ramsbotham, “Analysis and Assessment for Peacekeeping Operations”; and Smith, “Intelligence and UN Peacekeeping”.

13 As part of management reforms at the Secretariat, the DPKO was redesignated as Department of Peace Operations (DPO) in 2018.

14 Peacekeeping-intelligence (PKI) refers specifically to the UN’s adapted concept for its intelligence practice. See United Nations, Policy: Peacekeeping-Intelligence (New York: Department of Peace Operations, 2019); and Sarah-Myriam Martin-Brûlé, Finding the UN Way on Peacekeeping-Intelligence (New York: International Peace Institute, 2020).

15 UNHQ, Code Cable #1055, 26 May 2017.

16 Ibid.

17 United Nations, Policy: Peacekeeping-Intelligence, 3.

18 Loch K. Johnson, “The Development of Intelligence Studies,” in Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies, ed. Robert Dover, Michael S. Goodman, and Claudia Hillebrand (Oxfordshire and New York: Routledge, 2014); Michael Herman, Intelligence Power in Peace and War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Sam Goldstein, Jack A. Naglieri, and Dana Princiotta, Handbook of intelligence: Evolutionary Theory, Historical Perspective, and Current Concepts. (New York: Springer, 2015); Sam Goldstein, Jack A. Naglieri, and Dana Princiotta, Handbook of intelligence: Evolutionary Theory, Historical Perspective, and Current Concepts. (New York: Springer, 2015); and Stephen Marrin, “Improving Intelligence Studies as an Academic Discipline,” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 2 (2016): 479–90. These scholarly works provide context regarding the evolution of intelligence studies.

19 Loch K. Johnson, “National Security Intelligence,” in Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence, ed. Loch K. Johnson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Herman, Intelligence Power in Peace and War; Johnson, The Development of Intelligence Studies, 3–9; and Marrin, “Improving Intelligence Studies as an Academic Discipline.” These scholars identify this lacuna and provide a cursory look at its implications for intelligence studies.

20 Stafford T. Thomas, “Assessing Current Intelligence Studies,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counter Intelligence 2, no. 2 (1988): 217–44; Herman, Intelligence Power in Peace and War, 137–140; Loch K. Johnson, ed. Handbook of Intelligence Studies (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2007); Gregory F. Treverton and Wilhelm Agrell, ed. National Intelligence Systems: Current Research and Future Prospects (New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, Sixth ed. (Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2015); Loch K. Johnson, ed. The Oxford Handbook of National Security Intelligence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); and Robert Dover, Michael S. Goodman, and Claudia Hillebrand, ed. Routledge Companion to Intelligence Studies (Oxfordshire and New York: Routledge, 2014).

21 Munton and Fredj, “Sharing Secrets: A Game Theoretic Analysis of International Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 26, no. 4 (2013): 666–92.

22 Lander, “International Intelligence Cooperation: An Inside Perspective,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 17, no. 3 (2004): 481–93.

23 Bradford H. Westerfield, “America and the World of Intelligence Liaison,” Intelligence and National Security 11, no. 3 (1996): 523–60; Richard J. Aldrich, “British intelligence and the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’ during the Cold War,” Review of International Studies 24, (1998): 331–51; Stéphane Lefebvre, “The Difficulties and Dilemmas of International Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 16, no. 4 (2003): 527–42; Chris Clough, “Quid Pro Quo: The Challenges of International Strategic Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 17, no. 4 (2004): 601–13; Adam D.M. Svendsen, “Connecting Intelligence and Theory: Intelligence Liaison and International Relations,” Intelligence and National Security 24, no. 5 (2009): 700–29; Musa Tuzuner, ed. Intelligence Cooperation in the 21st Century: Towards a Culture of Sharing, Amsterdam, Netherlands (IOS Press, 2010); and Pepijn Tuinier, “Explaining the Depth and Breadth of International Intelligence Cooperation: Towards a Comprehensive Understanding,” Intelligence and National Security 36, no. 1 (2021): 116–38.

24 Mats R. Berdal, “Whither UN Peacekeeping?: An Analysis of the Changing Military Requirements of UN Peacekeeping with Proposals for Its Enhancement,” Adelphi papers Issue 281 (1993): 30–50; Robert E. Rehbein, Informing the Blue Helmets: The United States, UN Peacekeeping Operations and the Role of Intelligence (Kingston, ON: Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University, 1996); David Carment and Martin Runder, ed. Peacekeeping Intelligence: New Players, Extended Boundaries (Oxon: Routledge, 2006); Ekpe, “The Intelligence Assets of the United Nations: Sources, Methods, and Implications”; Chesterman, “Does the UN have intelligence; Dorn, ‘Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters? The Information and Research Unit and the Intervention in Eastern Zaire (1996); Melanie Ramjoué, “Improving UN Intelligence through Civil-Military Collaboration: Lessons from the Joint Mission Analysis Centres,” International Peacekeeping 18, no. 4 (2011): 468–84; and Olga Abilova and Alexandra Novosseloff, Demystifying Intelligence in UN Peace Operations: Toward an Organisational Doctrine (New York: International Peace Institute, 2016).

25 See for instance, Allard Duursma and John Karlsrud, “Predictive Peacekeeping: Strengthening Predictive Analysis in UN Peace Operations,” Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 8, no. 1 (2019): 1–19; Chris Perry, “Machine Learning and Conflict Prediction: A Use Case,” Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 2, no. 3 (2013); Robert A Blair, Christopher Blattman, and Alexandra Hartman, “Predicting Local Violence: Evidence from a Panel Survey in Liberia,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 2 (2017); Michael Colaresi and Zuhaib Mahmood, “Do the Robot: Lessons from Machine Learning to Improve Conflict Forecasting,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 2 (2017); Walter Dorn, Smart Peacekeeping: Toward Tech-Enabled UN Operations; Walter A. Dorn, Keeping Watch: Monitoring, Technology and Innovation in UN Peace Operations (Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University Press, 2011); Allard Duursma, Protection of Civilians: Mapping Data-Driven Tools and Systems for Early Warning, Situational Awareness, and Early Action (Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021); and Karlsrud, “Peacekeeping 4.0: Harnessing the Potential of Big Data, Social Media and Cyber Technology,” in Cyber Space and International Relations: Theory, Prospects and Challenges, ed. Jan-Frederik Kremer and Benedikt Muller, 141–60 (Berlin: Springer, 2014).

26 Karlsrud, “Peacekeeping 4.0.,” 141.

27 Dorn, Smart Peacekeeping, 1, 12–13.

28 Cees Wiebes, Intelligence and the War in Bosnia 1992 – 1995: The Role of the Intelligence and Security Services (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2003).

29 Abilova and Novosseloff, Demystifying Intelligence in UN Peace Operations: Toward an Organisational Doctrine.

30 Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 83.

31 Developed from Author’s Research Note (2020)..

32 Conor Cruise O’Brien, To Katanga and Back: A UN Case History (New York City: Simon and Schuster, 1963), 76.

33 Alex J. Bellamy, Global Politics and the Responsibility to Protect: From Words to Deeds (Oxon: Routledge, 2010), 129.

34 O’Brien, To Katanga and Back: A UN Case History, 76; Brian Urquhart, Hammarskjöld (Knopf Books for Young Readers, 1972), 159–60.

35 ”A Military Staff for the UN Secretariat,” Foreign Office Archives, FO Doc. 371/166872, Jan 31, 1962, cited by Abilova and Novosseloff, Demystifying Intelligence in UN Peace Operations, 25.

36 Jane Boulden, “United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC),” in The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, ed. Joachim A. Koops et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 161–62; and Dorn and Bell, “Intelligence and Peacekeeping: The UN Operation in the Congo 1960–64.” These works provide a full historical analysis of the conflict.

37 Walter A. Dorn, “The Cloak and the Blue Beret: Limitations on Intelligence in UN Peacekeeping,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 12, no. 4 (1999): 414–47.

38 Per Martin Norheim-Martinsen and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, “Towards Intelligence-Driven Peace Operations? The Evolution of UN and EU Intelligence Structures,” International Peacekeeping 18, no. 4 (2011): 454–67.

39 Dorn and Bell, “Intelligence and Peacekeeping”.

40 Ibid.

41 Allard Duursma, “Counting Deaths While Keeping Peace: An Assessment of the JMAC’s Field Information and Analysis Capacity in Darfur,” International Peacekeeping 24, no. 5 (2017): 823–47.

42 Dorn and Bell, “Intelligence and Peacekeeping”.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 For detailed analysis of the specific impact of the MIB on ONUC operations, see Dorn and Bell, ‘Intelligence and Peacekeeping.

46 Haidi Willmot, Improving U.N. Situational Awareness:Enhancing the U.N.’s Ability to Prevent and Respond to Mass Human Suffering and to Ensure the Safety and Security of Its Personnel (United States of America: Stimson Center, August 2017).

47 Abilova and Novosseloff, Demystifying Intelligence in UN Peace Operations; and James O. C. Jonah, ‘Office for Research and Collection of Information,’ in International Conflict Resolution Using System Engineering (SWIIS): Proceedings of the IFAC Workshop, Budapest, Hungary, 5–8 June 1989, ed. Harold Chestnut, Tibor Vámos, and Peter Kopacek (Pergamon Press, 1990).

48 Jonah, Office for Research and Collection of Information.

49 Bellamy, Global Politics and the Responsibility to Protect: From Words to Deeds, 130–133; and Gareth Evans, Cooperating for Peace: The Global Agenda for the 1990s and Beyond (Sydney, S. Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 1993), 65.

50 Chesterman, Does the UN have intelligence.

51 Ibid.

52 Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 69.

53 Ibid.

54 The Head of the PINS was a Soviet national, prompting the suspicion of Soviet interference in the UN.

55 Chesterman, “Does the UN have intelligence,” 154; and Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 67.

56 Chesterman, Does the UN have intelligence.

57 Eric G. Berman and Katie E. Sams, Peacekeeping in Africa: Capabilities and Culpabilities (Geneva & Pretoria: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) & Institute for Security Studies (ISS), 2000), 27–28. For context, from ONUC in 1960, the UN deployed 13 missions compared to the 32 missions between 1990–99.

58 Wiebes, Intelligence and the War in Bosnia 1992 – 1995, 36; Dorn, “United Nations Peacekeeping Intelligence,” 277, 287–90.

59 Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking, and Peace-keeping.

60 Chesterman, Does the UN have intelligence.

61 Ramsbotham, Analysis and Assessment for Peacekeeping Operations.

62 Dorn and Bell, Intelligence and Peacekeeping: The UN Operation in the Congo 1960–64.

63 Ramsbotham, “Analysis and Assessment for Peacekeeping Operations”; and Smith, “Intelligence and UN Peacekeeping.”

64 Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,’ 70.

65 Ibid.

66 Ibid.

67 Berdal, “Fateful Encounter: The United States and UN Peacekeeping.”

68 Smith, “Intelligence and UN Peacekeeping.”

69 Ramsbotham, “Analysis and Assessment for Peacekeeping Operations.

70 Martin-Brûlé, Finding the UN Way on Peacekeeping-Intelligence.

71 See for instance United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, Standing Operating Procedure: UNIFIL Joint Mission Analysis Centre Ref: HOM POL 20–16; United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, UNIFIL Crisis Management and Joint Operations Centre (JOC) Procedures Ref: HOM POL 16–16; United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali Standard Operating Procedure Early Warning and Rapid Response Ref. MINUSMA 2020.11; United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, SOP 2014/4 on Intelligence Cycle Management, 22 December 2014; United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, MINUSMA’s Mission-wide Intelligence Acquisition Plan, August 2018.

72 Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 71.

73 Frank van Kappen, “Strategic Intelligence and the United Nations,” in Peacekeeping Intelligence: Emerging Concepts for the Future, ed. Ben de Jong, Wies Platje, and Robert David Steele (Oakton, VA: Open Source Solutions, International Press, 2003).

74 Dorn, “Intelligence at UN headquarters?.

75 Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 71; and Berdal, ‘Fateful Encounter.’ This system was used in Somalia in 1992–93 and to the former Yugoslavia in 1993

76 Kappen, “Strategic Intelligence and the United Nations”; and Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?,” 67–86.

77 Dorn, “The Cloak and the Blue Beret.

78 Dorn, “Intelligence at UN headquarters,” 444. Gratis officers were officers from member states who were seconded to the UN and paid by their home country.

79 In all, a total of 500 staff including 219 military officers were affected. Dorn, “The Cloak and the Blue Beret,” 82.

80 United Nations, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly: Gratis Personnel Provided by Governments and other Entities A/RES/51/243 10 October 1997 (New York: General Assembly, 1997).

81 Abilova and Novosseloff, Demystifying Intelligence in UN Peace Operations.

82 William J. Durch et al. The Brahimi Report and the Future of UN Peace Operations The Henry L. Stimson Centre (Washington DC: The Henry L. Stimson Centre, 2003), 38.

83 See Dorn, “Intelligence at United Nations Headquarters?.” In this article, Walter Dorn provides a detailed analysis of the intelligence contributions and lessons drawn from the I&R Unit.

84 United Nations, Report of the Panel on U.N. Peace Operations: Comprehensive Review of the Whole Question of Peacekeeping Operations in All Their Aspects A/55/305-S/2000/809., para. 51 (emphasis mine).

85 Ibid.

86 United Nations, Report of the Panel on U.N. Peace Operations: Comprehensive Review of the Whole Question of Peacekeeping Operations in All Their Aspects A/55/305-S/2000/809., paras 65–75; and United Nations, Report of the Secretary-General on the implementation of the report of the Panel on United Nations peace operations A/55/502, (New York: General Assembly, 2000), 9–12.

87 Chesterman, ‘Does the UN have intelligence.

88 Durch et al. The Brahimi Report and the Future of UN Peace Operations, 39.

89 Ibid.

90 Dorn, ‘United Nations Peacekeeping Intelligence,’ 282; Kappen, ‘Strategic Intelligence and the United Nations.

91 Susan Wright, “The Hijacking of UNSCOM,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 55, no. 3 (1999): 23–25; and David Wise, “Is U.N. the Latest Cover for CIA Spies?,” Los Angeles Times, 17 January 1999, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jan-17-op-64370-story.html (accessed October 30, 2019).

92 Chesterman, “Does the UN have intelligence,” 154.

93 Ronald Hatto, “UN Command and Control Capabilities: Lessons from UNIFIL’s Strategic Military Cell,” International Peacekeeping 16, no. 2 (2009): 186–98; and United Nations, Resolution 1701 (2006) Adopted by the Security Council at its 5511th meeting, on 11 August 2006 S/RES/1701 (New York: United Nations Security Council, 2006), 4; Alexandra Novosseloff, ‘Expanded United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL II),’ in The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, ed. Joachim A. Koops et al. (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015), 774.

94 United Nations, Comprehensive review of the Strategic Military Cell: Report of the Secretary-General A/62/744 (New York, 2008).

95 Hatto, “UN Command and Control Capabilities,” 774.

96 Novosseloff, ‘Expanded United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL II), ’ 774.

97 Hatto, “UN Command and Control Capabilities,” 774.

98 United Nations, Report on the Comprehensive Analysis of the Office of Military Affairs in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations A/62/752 (General Assembly, 2008), 9.

99 Ibid.

100 United Nations, Financial performance report for the period from 1 July 2006 to 30 June 2007 and proposed budget for the support account for peacekeeping operations for the period from 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2009: Report of the Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions A/62/855 ;(New York: General Assembly, 2008), 18–19.

101 Norheim-Martinsen and Ravndal, ‘Towards Intelligence-Driven Peace Operations?..

102 Colonel George Sam (Chief of AT, OMA, DPO), in discussion with the author, 12 August 2021.

103 Interview with Senior UN Official, New York, October 8, 2019.

104 The staff are professional military intelligence officers drawn from Member States, but unlike the I&R unit in the past, they do not have working affiliations to their parent agencies during the time of their secondment.

105 Thierry Tardy, “A Critique of Robust Peacekeeping in Contemporary Peace Operations,” International Peacekeeping 18, no. 2 (2011): 152–67; and Christine Gray, “Peacekeeping After the “Brahimi Report”: Is There A Crisis of Credibility for the UN?,” Journal of Conflict & Security and Law 6, no. 2 (2001): 267–88.

106 United Nations, SOP on Headquarters Crisis Response in Support of Peacekeeping Operations Ref.2016.17 (New York: Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, 2017); United Nations, Policy: Joint Operations Centre Ref. 2019.20 (New York: Department of Peace Operations, 2019); United Nations, Guidelines on Joint Operations Centre Ref. 2019.21 (New York: Department of Peace Operations, 2019); United Nations, SOP on Integrated Reporting from Peacekeeping Operations to UNHQ Ref. 2019.10 (New York: Department of Peace Operations, 2019).

107 Martin-Brûlé, Finding the UN Way on Peacekeeping-Intelligence; Sarah-Myriam Martin-Brûlé and Nadia Assouli, Joint Mission Analysis Centre Field Handbook (New York: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, 2018).

108 References to the supporting SOPs and policies are: United Nations, SOP on Access to Information PK/G/2010.36 (New York: Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, 2011); United Nations, Joint Mission Analysis (JMAC) Guidelines PK/G/2015.04 (New York: Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, 2015); United Nations, Policy on Joint Mission Analysis (JMAC) Guidelines PK/G/2015.03 (New York: Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support, 2015); United Nations, Policy: Joint Mission Analysis Centres (JMAC) Ref. 2020.06 (New York: Department of Peace Operations, 2020).

109 Philip Shetler-Jones, “Intelligence in Integrated UN Peacekeeping Missions: The Joint Mission Analysis Centre,” International Peacekeeping 15, no. 4 (2008): 517–27.

110 Ibid.

111 Martin-Brûlé and Assouli, Joint Mission Analysis Centre Field Handbook, 15.

112 Norheim-Martinsen and Ravndal, ‘Towards Intelligence-Driven Peace Operations?..

113 Michael Dziedzic and Robert M. Perito, Haiti: Confronting the Gangs of Port-au-Prince, United States Institute of Peace (Washington D.C: United States Institute of Peace, 2008), 8.

114 Duursma, ‘Counting Deaths While Keeping Peace.

115 Duursma, “Counting Deaths While Keeping Peace”; Allard Duursma, “Information Processing Challenges in Peacekeeping Operations: A Case Study on Peacekeeping Information Collection Efforts in Mali,” International Peacekeeping 25, no. 3 (2018): 446–68; and Duursma and Karlsrud, Predictive Peacekeeping.