ABSTRACT

Most terrorist groups are active close to their native area of operation. Why then do some terrorist groups expand to foreign territories? In an exploratory attempt, this article draws parallels between organised crime group transplantation frameworks and the transnational activities of terrorist groups. Utilising transplantation studies, we introduce a conceptual criminological framework that integrates both push and pull factors influencing the transnational movement of terrorist groups. To validate this framework as a pilot test, we apply it to al-Qaeda’s operations in the Sahara-Sahel region, relying on open-source data. Our findings, while preliminary, indicate the potential of this unified transplantation approach in offering deeper insights into the transnational behaviours of terrorist groups.

Introduction

The transnational expansion of terrorist groups is a subject of increasing interest in both academia and policy-making (Boeke, Citation2022; Varese, Citation2020). Despite the fact we live in a globalised world, few terrorist organisations actively expand to foreign territories and conduct activities outside their native area of operation (Crenshaw, Citation2020; Gill et al., Citation2019; Jordán, Citation2014; Kohlmann & Pantucci, Citation2010; Mendelsohn, Citation2018; Rossmo & Harries, Citation2011; Varese, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). This observation begs the question: why then do some terrorist groups, despite existing barriers, expand outside their native area of operation? To answer this question, we seek insights from the field of criminology in which transnational expansion was studied primarily in relation to organised crime. In particular, what can organised crime group expansion, often dubbed transplantation, tell us about terrorist group manifestation outside their native region (Varese, Citation2011b)? This article offers an initial step in answering calls to construct a unified, criminology based, transplantation framework in order to eventually apply it in a systematic and empirical manner to terrorist group case studies (Silverstone, Citation2011; Arsovska, Citation2016; Calderoni et al., Citation2016; Moro & Villa, Citation2017; Varese, Citation2020). To begin finding answers, the framework is applied in an exploratory way to al-Qaeda in the Sahara-Sahel as a first test, based on open sources.

Bringing together theoretical insights from the transplantation literature

The premise behind transplantation revolves around the movement of an illicit group from its area of origin to a foreign territory. Building on Galeotti, Massari and Gambetta, Federico Varese was the first criminologist to coin the term ‘transplantation’, meaning the ability of an organised crime group to control an outpost over a sustained period outside its region of origin and routine activity (Galeotti, Citation2000; Gambetta, Citation1993; Varese, Citation2011b). Varese identifies three criteria for transplantation: Firstly, the actor conducting the relocation or expansion must be considered as an illicit entity. Secondly, the organised crime group should (willingly or unwillingly) create an operational base outside its native area of origin and routine operation. Thirdly, the movement should be durable, in the sense it must exist for a prolonged period of time and not be considered an ad-hoc border crossing (Varese, Citation2011b). Others built on Varese’s work reinterpreting transplantation as functional diversification, infiltration and reproduction of the criminal enterprise abroad (Calderoni et al., Citation2016; Campana, Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014)

Although not formally part of transplantation literature, it is worth noting several studies on the spatial distribution of terrorism in our examination of terrorist transplantation, potentially contributing to our understanding terrorist transplantation. These studies provide a multi-dimensional view of the spatial attributes of terrorism, weaving together the influences of geography, urban planning, ideology, and predictive analytics.

Cothren et al. and Rossmo and Harries have emphasised the proximity between terrorists’ residences and their operational activities (Rossmo & Harries, Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2008). Their research suggests that terrorists tend to commit attacks in areas close to where they live or where their cells operate. They found that about half of the terrorists reside and prepare for their operations within a 30-mile radius of their target locations. This proximity may afford logistical convenience, greater operational security, and a deeper familiarity with the target environment, which can be exploited to execute attacks efficiently.

Berrebi and Lakdawalla extended the spatial analysis to the role of international borders in facilitating terrorist activities (Berrebi & Lakdawalla, Citation2007). They assert that the presence of international borders near terrorist bases can lower the costs and logistical barriers associated with cross-border attacks. This increased accessibility may result in a higher frequency of transnational terrorist incidents, indicating a strategic use of border regions.

Urban environments present unique challenges in the context of terrorism, as described by Savitch (Savitch, Citation2005). Urban terrorism is characterised by attacks in densely populated areas, targeting non-combatants and key infrastructure. The complexity of urban settings provides terrorists with opportunities to blend into the civilian population and exploit the anonymity that cities offer.

Nemeth, Mauslein, and Stapley focused on identifying the geographic and socio-economic factors that correlate with the incidence of domestic terrorism (Nemeth et al., Citation2014). Their work highlights how specific conditions, such as mountainous regions, proximity to state capitals, large populations, high population density, and poor economic conditions, can create fertile grounds for terrorist activities. Moon and Carley utilise multiagent modelling to simulate the social and spatial distributions of terrorist networks (Moon & Carley, Citation2007). Their methodology aims to uncover leaders, organisational vulnerabilities, and hotspots.

Buffa et al. employed remote sensing, spatial statistics, and machine learning in predicting terrorism hotspots (Buffa et al., Citation2022). Their study underscores the potential of integrating technology with spatial analysis to forecast and potentially prevent terrorist incidents. Onat and Gul examined how ideological influences shape the spatial patterns of terrorism (Onat & Gul, Citation2018). They argue that the ideological nature of terrorist groups can impact their choice of location, affecting where attacks are planned and executed.

Lastly, on the concept of ‘terrorist hot spots’, Braithwaite and Li investigate the identification and effects of transnational terrorism hot spots (A. Braithwaite & Li, Citation2007). Their findings indicate that countries within these hot spots are more likely to see an increase in terrorist activities. These studies dovetail with studies in transplantation literature concerning areas with little state authority presence (Hansen, Citation2019; Varese, Citation2011b). While indeed a rich literature on this topic exists, it is interesting to pursue future empirical research specific in this area.

Despite notable research, transplantation by illicit actors continues to be an understudied phenomenon in many respects (Allum, Citation2014; Morselli et al., Citation2011; Sergi, Citation2015; Ubah, Citation2007; Varese, Citation2011b). Moreover, an overarching theory of transplantation is yet to be developed (Allum, Citation2014; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014; Varese, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). As observed in the 2011 special issue of Global Crime, there are still open questions regarding the transnational movement of organised crime groups and in particular the associated factors (McIntosh & Lawrence, Citation2011). With respect to the reasons behind transplantation, we identify two theoretical positions: the emergent and strategic position.

The emergent position of transplantation

The emergent position largely falls under environmental criminology as it is focused on situational and opportunity structures (Schoenmakers et al., Citation2013). This approach departs from the premise that expansion is easily conducted by organised crime groups and that they intentionally settle in foreign territories to ‘grab’ the available criminal opportunities and (illicit) markets (Morselli et al., Citation2011). Proponents of the emergent approach argue that certain environments inherently have vulnerabilities to various crimes due to a lack of government authority presence or due to the widespread presence of criminal opportunities (Morselli et al., Citation2011). According to the emergent approach, organised crime groups are often believed to be acting strategically, whereas in fact criminogenic environments or contextual factors primarily explain how they expand (Morselli et al., Citation2011). It is the local environment, or context, that determines through pull factors how organised crime groups emerge in a territory. Opportunities and vulnerabilities in the specific ‘emergent’ context allow organised crime groups to form, thus making the environment and opportunities more important than the strategic intent (Schoenmakers et al., Citation2013).

The emergent position demonstrates how organised crime groups face significant challenges in establishing their activities outside their native territories (Gambetta, Citation1993; Reuter, Citation1985; Ubah, Citation2007; Varese, Citation2011b). According to Varese, criminals conduct foreign activities because they are forced to relocate due to pressure from authorities or competitors. Varese argues that transplantation occurs mainly because organised crime groups make the most out of bad luck moving abroad not out of their own desire (Varese, Citation2011b). Thus, organised crime groups do not actively plan to establish new branches or bases in foreign territories (Varese, Citation2020). Because of the forced character of their relocation, these groups experience considerable difficulty. The groups do not know who is trustworthy, have yet to prove themselves and face possible competition from native organised crime groups (Gambetta, Citation1993; Reuter, Citation1985; Ubah, Citation2007).

The emergent approach can more broadly be placed in-line with deprivation, social ladder and ethnic succession theories, all agreeing that the emergence of organised crime groups is primarily due to local conditions and opportunity structures (Albini, Citation1971; Bell, Citation1953; Ianni, Citation1974; Ianni & Reuss-Ianni, Citation1972; Ubah, Citation2007; Woodiwiss, Citation2001). This broad category of theories also takes into account specific cultural orientations in a country and a lack of opportunities for certain ethnic groups as an explanation for organised crime group emergence. Once some groups move up the ladder, others may take their place. Emergence depends heavily on the local context, the character of the group, its members and the effects of the local setting and networks on them (Lavorgna et al., Citation2013). For instance, studies on the emergence of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra in the United States stress the blocked mobility of early Sicilian immigrants who found their new home base alienating as a result of resentment from the native population (Lombardo, Citation2012; Ubah, Citation2007). These studies suggest that the Cosa Nostra in the United States adapted to the local system and opportunity structure when they emigrated to the United States (Lombardo, Citation2012). This is line with organised crime acting as a ‘queer ladder of social mobility’ (Bell, Citation2000). Groups move into organised crime due to the lack of formal opportunities for upward social mobility and discontinue criminal activities when legitimate opportunities become available (Albanese, Citation2010, Citation2011; Finckenauer & Waring, Citation1998; Ianni, Citation1974).

The strategic position of transplantation

The strategic position views the expansion of organised crime groups differently. Groups are seen as intentional, mobile and acting strategically and rationally (Castells, Citation2010; Shelley, Citation1999, Citation2006). According to this position, organised crime groups are motivated by larger profits and market control in new markets with new connections. They tend to settle in territories creating durable foreign bases and alliances with other criminal actors (Castells, Citation2010; Shelley, Citation1999, Citation2006). Thus, location decisions are seen as outcomes of a cost-benefit analysis influenced by economic globalisation and international migration (Varese, Citation2011a, Citation2020). This intentional movement together with the aim of taking control over markets and opportunities, forms the strategic context of organised crime group transplantation (Morselli et al., Citation2011).

The strategic approach implies that an organised crime group intentionally infiltrates a foreign territory while being controlled through an original domestic base (Ubah, Citation2007). The so-called ‘alien conspiracy’ theories of organised crime touch upon this perspective suggesting that waves of international migration intentionally ‘exported’ established organised crime groups to foreign territories (Morselli et al., Citation2011; Varese, Citation2011b). Studies on Italian ‘Mafia’s’ in the United States, explained through the strategic expansion approach, argue that the organisational structure, membership and ideology of the Cosa Nostra was imported by migrating Italians (Albini, Citation1988; Cressey, Citation1969). These individuals are believed to have been members of established Italian organised crime groups who were specifically directed to create new outposts abroad (Albini, Citation1971; Cressey, Citation1969; McWeeney, Citation1987).

Toward an integrated transplantation perspective

The study of terrorism, traditionally explored by political scientists and international relations scholars, has recently seen a growing interest from criminology (Freilich & Lafree, Citation2015; Lynch, Citation2011). Criminology’s analytical tools have proven useful for understanding terrorist behaviour (Lynch, Citation2011). Environmental criminology, a rational choice approach focusing on the situational aspects of crime rather than on the motivations behind it, is one such tool that has gained traction in terrorism studies (Freilich & LaFree, Citation2016). It investigates how immediate environmental factors create opportunities for crime, providing a framework for understanding the interplay between terrorist actors and their operational contexts (Clarke & Newman, Citation2006).

Within environmental criminology, three opportunity frameworks stand out. Firstly, studies on suicide terrorism have applied the rational choice framework to argue that terrorists conduct cost-benefit analyses similar to other criminals (Perry & Hasisi, Citation2015). The crime pattern framework, on the other hand, suggests that crimes occur where the paths of offenders and victims intersect, often in ‘hotspots’ of criminal activity (Brantingham & Brantingham, Citation1981). The routine activities framework posits that crime arises when a potential offender and target coincide in the absence of a capable guardian, shedding light on the factors that enable crimes like terrorism (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979; Felson & Clarke, Citation2011). These approaches have been applied to various terrorist activities to understand the specific conditions under which they occur (Clarke & Newman, Citation2006; Fahey et al., Citation2012). The detailed analysis of the environmental context and criminal opportunities provided by these theories helps in developing targeted prevention strategies (Mazerolle & Wortley, Citation2013).

Situational Crime Prevention (SCP), derived from these frameworks, focuses on altering the environment to reduce crime opportunities, and its principles have been applied to a range of terrorist acts (Clarke, Citation2009; Freilich & Newman, Citation2009). SCP emphasises the importance of specific criminal categories over broad classifications, advocating for separate analysis of different forms of terrorism (Newman & Clarke, Citation2007). It suggests that by reducing opportunities and increasing risks for terrorists, authorities can prevent terrorist acts (Clarke & Newman, Citation2006; Lynch, Citation2011).

Other criminological theories put more emphasis on the factors that prevent individuals from engaging in deviant behaviour. In the context of terrorism, control theories can explain why some individuals or groups resist the influence or expansion of terrorist groups. Braithwaite’s discussion on organisational crime can be applied to terrorist groups, examining how social bonds and (the lack of) institutional controls may influence the capacity of these groups to establish a presence in new regions (Braithwaite, Citation1989). Additionally, general strain theory posits that individuals who experience certain societal strains, stressors and crime opportunities are more likely to engage in crime. Walters’ exploration of strain theories in relation to hate crime can be adapted to terrorism, suggesting how socio-economic strains might precipitate the spread of terrorist groups as they seek to alleviate their grievances through expansion (Walters, Citation2011). The latter criminological theories can be part of an explanatory model by focussing on opportunity structures and motivations altogether. However, this is not explored in-depth here as the present article looks at concrete opportunities for transplantation or the lack thereof.

In transplantation, both the emergent and strategic approaches have seen limited systematic empirical testing thus far. Studies have mostly focused on Italian-origin organised crime groups (Arsovska, Citation2016; Silverstone, Citation2011). A thoroughly integrated theory on criminological transplantation does not exist so far. However, Varese and Morselli, Turcotte and Tenti offered two influential perspectives on transplantation in their attempt to empirically strengthen and analytically summarise the field.

Varese sees transplantation as a combination of push and pull factors or supply and demand of ‘mafiosi’ and their ‘services’ in his ‘property-rights’ theory of organised crime (Varese, Citation2011b). In contrast to studies that largely focus on Italian organised crime groups, Varese looks at Russian, Chinese and Japanese cases, adding robustness to his comparative research and improving the empirical diversity in the transplantation literature. He finds that organised crime groups manifest themselves in territories undergoing a sudden socio-economic transition/shock, experience weak legal structures to settle disputes and have a supply of individuals skilled in violence that become unemployed during this socio-economic transition. These individuals thus seek to employ their skills elsewhere (Gambetta, Citation1993; Varese, Citation2011b).

Based on these case studies, Varese concludes that situational and contextual factors seem to prevail. Organised crime group members were never willing to move to a foreign territory of their own accord (Varese, Citation2011b). The motivation of organised crime groups to ‘seize’ foreign markets, resources and make strategic investments do not appear to be the primary determinants of successful transplantation (Varese, Citation2011b). It is simply very difficult to export an illicit group and seize a foreign territory because local information, networks and contacts are crucial. Also, just the presence of criminal migrants in a foreign territory is by itself insufficient for transplantation to occur (Varese, Citation2011b). However, this is rarely the complete story as the group may have strategic goals and have awareness of opportunities in other territories. Varese therefore combines factors that can be categorised under both the emergent and the strategic position.

Firstly, we organise factors under the banner of push and pull factors that we further divide in willing and unwilling. Willing Push factors occur when organised crime groups want to (1) increase their resources/capabilities, knowledge, innovation, equipment and safe areas from which to operate; (2) seek investments and money laundering opportunities abroad in both legitimate and illegitimate sectors; (3) seek new markets abroad due to a potential gap in a ‘market’ in another territory with no or few active competitors. This can include protection or providing any (criminal) service or good in which the group has relevant expertise or connections (Varese, Citation2011a).

Secondly, unwilling push factors occur due to (1) general migration be it due to economic reasons, wars, conflict, disasters, persecution of ethnic groups and (2) due to specific government policies that result in the spread of organised crime groups transnationally. Varese gives an example of the Italian forced resettlement policy, the so-called ‘soggiorno obbligato’, that forced members of organised crime groups to live away from their areas of origin as punishment. (3) Organised crime groups can unwillingly migrate in order to escape conflict or rivalry from competitors and efforts from authorities. Also, individual members can be expelled to a foreign territory by their seniors (Varese, Citation2011a).

Furthermore, Varese looks at the extent of command-and-control the leadership of organised crime groups have over their foreign agents. Firstly, the leadership may find it difficult to monitor their foreign agents, which is a typical principal-agent problem. The agent may engage in activities that are not sanctioned, cooperate with authorities and even establish a new group (Gambetta, Citation1993; Reuter, Citation1985; Varese, Citation2011b). Varese calls for additional studies in exploring to what extent foreign agents become autonomous over time from their parents organisations (Varese, Citation2020). Secondly, information collection in an unfamiliar territory is difficult for organised crime groups. This makes effective communication between foreign agents and parents without authorities intercepting their messages challenging (Varese, Citation2011b). Finally, a solid reputation is essential for organised crime groups and can be especially difficult to establish in new territories (Reuter, Citation1985; Varese, Citation2011b). Reputation and trust are dependent on long-term relations of kinship, friendship and ethnic networks, making it hard to reproduce abroad (Gambetta, Citation1993; Varese, Citation2011b).

Similarly to Varese, Morselli et. al. consider opportunities as more important than strategic decisions by the group itself arguing that criminogenic conditions effectively ‘create’ organised crime groups by drawing them to territories where opportunities are available (Morselli et al., Citation2011). The first push factors they emphasise from the literature are: pressure from authorities and competition from competing groups (Morselli et al., Citation2011). The first pull factors they emphasise are: large demand for criminal services; access to supply; lax, ineffective or absent law enforcement; high levels of corruption; proximity to trafficking routes; porous borders and the presence of brokers and facilitators (Morselli et al., Citation2011).

Morselli et. al. also stress that kinship, reputation, local ties and diaspora networks play a role in assessing the degree of transplantation and their relationship with foreign organised crime groups (Bovenkerk et al., Citation2003; Morselli et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, they identify additional socio-economic push factors: increasing socioeconomic status; decreasing cultural marginalisation; increasing enforcement in country of origin against a specific group (Morselli et al., Citation2011). Additionally, they distil the following pull factors: legitimation and exit of previous groups; novel opportunities for transnational crimes (open borders); ethnic groups’ strong criminal reputations; strong local ties and kinship networks (Morselli et al., Citation2011). Regarding the strength of ethnic ties, studies show these factors by themselves likely do not explain transplantation; otherwise, there would be criminal groups along ethnic lines in every destination country. Moreover, ethnically homogenous crime groups are rare. It is clear, though, that strong networks can help in building trust (Silverstone, Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014; Varese, Citation2011a).

Finally, Morselli et. al. argue that the emergence of organised crime groups are also marked by opportunities in areas that have a demand for certain criminal services (Morselli et al., Citation2011). The final pull factors they identify relate to opportunity structures: lax enforcement and security in an area; poorly regulated economic sectors; overlap between upper and underworld actors (facilitators and financiers); low technology and professionalisation of economic sectors; high unemployment and number of disenfranchised workers; lack of legitimate service providers and products (conducive for black markets).

Combining the approaches into a taxonomy for analysis

The above summary of transplantation and the inherently scarce testing of hypotheses in the realm of organised crime, strongly suggests that in order to analyse terrorist group expansion, transplantation explanatory factors have to be combined. The review of the literature also suggest that factors derived from the emergent approach have more weight in the explanations than factors rooted in the strategic approach. It is unknown to what extent both observations also hold for terrorist groups’ expansion or lack thereof. The present article aims at integrating the factors found in the relevant criminological theoretical approaches combined with findings from studies on the expansion of organised crime groups. We organise this into a taxonomy that can be used for future systematic empirical testing in relation to the transplantation of terrorist groups. These factors may help understand expansion attempts and constraints. By summarising and grouping elements from previous transplantation research, two broad sets of push and pull factors are distinguished that may attract and drive illicit actors to and from different areas

Firstly, push factors can be organised around the willingness of illicit actors to migrate because of the desire to (a) attain capabilities, resources and investments not available in the territory of origin, (b) to conduct activities in a foreign territory due to ideological reasons and (c) the actor could possess knowledge, skills and connections that are conducive to take advantage of opportunities in a foreign territory (Calderoni et al., Citation2016; Morselli et al., Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014; Varese, Citation2011b, Citation2020). Secondly, push factors can be organised around a forced migration of the terrorist group because of (x) pressures, policies or crackdowns from authorities in their area of origin, (y) competition or conflicts with competitors or other illicit actors and (z), general transnational movements and migration of terrorists with relevant skills, knowledge and connections (Calderoni et al., Citation2016; Morselli et al., Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014; Varese, Citation2011b, Citation2020).

Secondly, pull factors regarding local conditions and opportunities in a foreign territory can be grouped around economic, cultural and institutional sets. (1) Economic factors include: illicit economic opportunities featuring easy access to supply and demand for criminal services, protection, materiel, recruits (black markets) and illicit trade and trafficking routes. Licit economic opportunities include: sectors with high unemployment and disenfranchisement, low technology and professionalisation; societies undergoing sudden change and economic booms; easy access to capabilities, resources and investments; low presence of competitors and presence of brokers and facilitators (Morselli et al., Citation2011). (2) Cultural factors include: a low level of general societal trust; the legitimation of ethnic groups, rise in their socioeconomic status and decreased marginalisation; presence of diasporas and open borders giving opportunities for transnational crimes; strong group reputation, strong existing local ties and kinship networks (Morselli et al., Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014). (3) Institutional factors include: lax security and law-enforcement; poor regulation and oversight of economic sectors; high government authority corruption; high ineffectiveness of government institutions (Crenshaw, Citation2020; Morselli et al., Citation2011; Sciarrone & Storti, Citation2014; Varese, Citation2011b).

Table 1. Summary of the push and pull dynamics together with the command-and-control factors.

Identifying transplantation factors in potential future case studies

Applying the introduced taxonomy to terrorist group cases is useful for several reasons. First, we can investigate the taxonomy using non-mafia case studies. Second, the theoretical insights provided from the above transplantation literature can help us better understand if and how transplantation dynamics are applicable to terrorist groups and in turn further drive the debate on transnational terrorism. At this stage, we cannot definitively determine which factors are crucial and which are irrelevant, as it is too early for a discussion based on empirical results. To achieve this, future in-depth case studies into terrorist groups that are active transnationally need to be conducted. Only then can the analytical construct be refined by excluding irrelevant or weak factors.

For the present article, we provide an initial exploration of the taxonomy, applying it to terrorist groups in the Sahara-Sahel region. Regarding the study of illicit group transplantation, the wider Sahara-Sahel region is an empirically target-rich area to study (D’Amato, Citation2018; Forest & Giroux, Citation2011). In this area, the jihadist al-Qaeda stands out regarding its transnational resonance and magnitude of activities. Studying this group provides us with a first step for future in-depth empirical study of the introduced transplantation framework on terrorist groups. Firstly, we start by presenting a timeline of al-Qaeda’s development in the Sahel and its evolution into the group Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM). Then, we seek to identify factors from the above transplantation taxonomy.

This empirical test case focused on open sources, primarily but not exclusively on academic articles. Our data collection involved a systematic search using specific terms related to al-Qaeda activities within the Sahara-Sahel region. We used the following search terms: al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), transnational terrorism, transplantation terrorism, al-Qaeda in the Sahel, AQIM Sahel, JNIM expansion, AQIM expansion, al-Qaeda expansion and terrorist transnational expansion. The search was temporally bounded, focusing on incidents and relevant activities reported between the years 2000–2023. We utilised a variety of search engines and databases, including Google Scholar, JSTOR, the Leiden University online database, and (regional) news databases, to ensure a comprehensive, non-exhaustive, collection of relevant academic literature, media reports, and publicly available government documents.

Each source was selected for its relevance to our study’s focus on al-Qaeda’s activities in the Sahara-Sahel. News reports were only included from established media organisations with editorial standards that ensure the veracity of reporting. From this information, we constructed a narrative around the expansion of al-Qaeda in the Sahara-Sahel from their origins in Algeria to their current structure in the form of JNIM. Moreover, this information suggests that, much like organised crime groups, al-Qaeda in the Sahara-Sahel and JNIM face similar challenges and operate in comparable ways when expanding across borders. We employed a credibility assessment based on the sources’ historical accuracy, reputation for factual reporting, and recognised expertise in terrorism and regional affairs. This was supplemented by an inter-source consistency check, where information from one source was deemed credible if corroborated by independent reporting from other reputable outlets. We acknowledge the inherent limitations in open-source research, including potential media biases and the variable quality of available data, particularly from conflict zones. We have delineated the scope of our data collection to maintain focus while acknowledging the inherent limitations of open-source research. With the aim to test our theoretical model in preliminary way these data suffice. Future work will benefit from incorporating a broader spectrum of primary data sources and a more comprehensive analysis that includes additional terrorist group case studies.

Al-Qaeda in the Sahara-Sahel

Al-Qaeda or ‘the base’ evolved from the Afghan resistance to Soviet occupation following the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. Fighters from Muslim communities throughout the world came to Afghanistan to fight against the Soviets making al-Qaeda’s makeup truly international from its inception. To date, al-Qaeda has been compared analytically to multinational organisations, resistance groups, computer networks, biological entities and other living organisms and various social movements (Asal et al., Citation2007; Bergen, Citation2002; Helfstein & Wright, Citation2011; Sageman, Citation2011). In recent years, al-Qaeda’s activities in the Sahel evolved from a regionally oriented movement with mostly domestic goals to an increasingly integrated element of the global jihad. Traditionally, the Sahel was a remote theatre drawing marginal attention from the senior leadership of al-Qaeda. This changed with the establishment and continuing regional expansion of al-Qaeda’s offshoots in the Sahel and Northern Africa. In these areas, al-Qaeda was primarily represented by AQIM and JNIM after their merger in 2017. However, the roots of JNIM’s transnational expansion can be traced back to 1993 with the Groupe Islamique Armé.

In 1993, returned jihadists from Afghanistan created the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in Algeria targeting the Algerian government and military. In 1998, the group transformed into the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC). The transformation was prompted by a renewed focus on jihadist ideology promoted partially through transnational connections created in Afghanistan with al-Qaeda’s leadership (Bencherif, Citation2021; Larémont, Citation2011). By 1998, GSPC had partially moved their activities to Mali due to pressure from Algerian authorities (Bøås, Citation2015; Thurston & Lebovich, Citation2013). In this period, the group started entrenching its members in the local context of Mali’s Timbuktu region by presenting themselves as traders, educators and intermarrying with the local population in order to avoid crackdowns from Algerian authorities (Bøås, Citation2015). After 9/11 and the Iraq war in 2003, GSPC’s council of chiefs decided to support the jihad in Iraq, formalising GSPC’s link with al-Qaeda (Bencherif, Citation2021). Between 1998 and 2007, because of their decision to support the global jihad, the GSPC attracted not only domestic Algerians but various other North African, Tuareg and Arab fighters (Steinberg & Werenfels, Citation2007). In 2004, Abdelmalek Droukdel became GSPC’s new leader and continued internationalising the group by entrenching its position in Mali, sending fighters to aid al-Qaeda in Iraq and expanding its recruitment efforts to other North African countries (Filiu, Citation2009). By managing al-Qaeda’s global jihadist outlook with GSPC’s local and regional concerns, he managed to grow the organisation outside Algeria’s borders (Bencherif, Citation2021).

In 2007, al-Qaeda’s former leader Ayman al-Zawahiri together with Droukdel, created AQIM. GSPC morphed into AQIM because of GSPC’s devotion to the global jihad and due to al-Qaeda’s wish to expand further in Africa (Bencherif, Citation2021; Filiu, Citation2009). Indeed, al-Qaeda, profited from the already established GSPC networks, (illicit) economic activity and ethnic links in the region (Walther & Christopoulos, Citation2015). The GSPC in turn benefitted from the al-Qaeda brand and had easier access to recruits and materiel. Following its creation, in order to expand operations throughout North Africa, AQIM co-opted smaller North African rival jihadist groups (Smith, Citation2007). Not all expansion efforts were successful. AQIM did not succeed in formally co-opting Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia and due to consistent pressure from both Tunisian and Algerian authorities, resulting in AQIM winding down operations in both countries (Zelin, Citation2020).

The 2007 merger sparked AQIM’s so-called ‘Sahelisation’ process because the group intensified their expansion further south into Mali and the wider region (Cristiani & Fabiani, Citation2011). Also, it transformed AQIM into multi-ethnic group by adding more non-Algerians into its ranks. In addition to Algerian government pressure, AQIM moved to the Sahel because of the lack of government authority presence in parts of Mali and Niger (Larémont, Citation2011). The vastness of the Sahara-Sahel region gave AQIM ample illicit opportunities. Traditionally, the area has been home to organised criminal activity due to the lack of legitimate opportunities for profit. The ancient trade routes across the poorly controlled Sahara-Sahel region have long been attractive to smugglers and robbers, and control over these routes has been a lucrative source of income (Hansen, Citation2019). Poor governance, social segregation, and corruption in the area have created an environment where AQIM could gain support by promising change to the disempowered population. Through previously established GSPC connections, AQIM deepened the ties to local Tuareg and Arab networks (Wehrey, Citation2018). By recruiting Tuaregs and Arabs, AQIM increased its knowledge of the large desert environment and strengthened its intelligence gathering capabilities (Bøås, Citation2015; Boeke, Citation2016).

In the years following the merger, AQIM used existing social systems, integrating itself further into local communities (Bøås, Citation2015). In the absence of Mali’s authorities, the group built an alternative system of governance, providing services and appropriating local grievances, presenting themselves as saviours to local populations (Bøås, Citation2015). By 2011, AQIM operated largely unbothered in an area ranging from southern Algeria, eastern Mauritania, northern Mali and into Niger. Here, made possible from its ethnic and other connections throughout the region, the group profited from activities such as kidnapping for ransom, smuggling and human trafficking (Boeke, Citation2022).

After the fall of the Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi in 2011, AQIM profited from a massive influx of weapons and experienced fighters from Libya (Wehrey, Citation2018). As a result, various armed groups were formed further adding to the destabilisation of Mali. This new dynamic caused a splintering in AQIM resulting in several new jihadist subgroups. As the group expanded south, Droukdel increasingly had trouble controlling his southern commanders (Bencherif, Citation2021). In 2012. A prominent southern commander, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, created his own group in the Sahel, al-Mourabitoun. He tried to distance himself from AQIM leadership and connect with al-Qaeda directly. At the same time, northern Mali was experiencing a Tuareg rebellion in which AQIM, al-Mourabitoun and the Tuareg commander Iad Ag Ghali’s Ansar Dine were involved. The violence caused the groups to collaborate giving them control over Northern Mali. AQIM’s leadership warned they should not lose support from the local population and offer them protection, economic development and limited governance (Bencherif, Citation2021). AQIM’s leadership advised the groups to work with the Tuareg rebels encouraging an inclusive management of the new Islamic state in northern Mali (Bencherif, Citation2021).

The groups’ victory was short-lived however. In 2013, France intervened in Mali driving the groups into rural areas. After France’s intervention, Amadou Kouffa – a commander and preacher in Ansar Dine – established a following among the Fulani in Mali, receiving support from Pakistani jihadists (Eizenga, Citation2020; Le Roux, Citation2019). Also, in 2015, a subcommander of al-Mourabitoune, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, broke away to start Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), eventually clashing with his former AQIM allies. The newly established ISGS was a fierce competitor and rival in the region that no single subgroup could take on by itself (Boeke, Citation2016).

However, after the French intervention in Mali in 2013 and the rise of ISGS in 2015, AQIM and the splinter groups re-joined. This reunification was caused by the shared loyalty to al-Qaeda’s leader and the fact that French troops and ISGS were now common enemies (Hansen, Citation2019). Thus, in 2017, driven by competition and crackdowns from common enemies, AQIM integrated with the splinter groups evolving into JNIM (Forbes, Citation2018; Skretting, Citation2020). The newly established JNIM formalised the existing collaboration between the groups, uniting all of them for the first time formally (Hansen, Citation2019). Through the subgroups, JNIM had vast support across the Tuareg, Fulani and Arab groups across the region.

After JNIM’s creation, the group focused on solidifying territorial control in large swaths of Mali to safeguard a stable safe haven (Eizenga, Citation2020). As of 2019, there was an uptick of activity attributed to JNIM in Niger, Burkina Faso and increasingly Togo, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Benin (NATO - JFC Naples, Citation2020). JNIM’s drivers for this seem to be focused around the control of artisanal gold mines, commercial and smuggling routes in the region and large nature reserves able to provide cover from authorities (Beevor, Citation2022; Eizenga, Citation2020). As of 2021, JNIM is active in these areas by acting as a security provider to miners and hunters in exchange for contributions from their economic activities (Beevor, Citation2022). And most recently, JNIM controls, or at least has active freedom of movement, in (parts) of Algeria, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Benin.

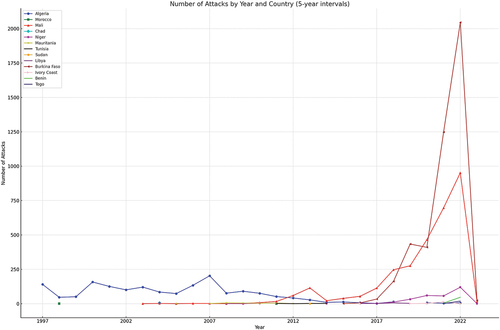

Using primary data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Database (ACLED), we provide an activity timeline of JNIM and its predecessor groups in (Raleigh et al., Citation2023). The largest peak of activities occurs after JNIM’s creation in 2017. Simultaneously, the group further expands its activities to other Sahelian and the Gulf of Guinea countries till the data cut-off year in January 2023. Similar albeit smaller rises in activity occur after GSPC morphed into AQIM and after the French intervention in Mali in 2007 and 2013 respectively.

Figure 1. Number of al-Qaeda and al-Qaeda affiliates’ attacks in the Sahel between 1997 and 2022.

Transplantation analysis

Evidence of a role for push factors

Terrorist groups need resources and capabilities to survive; if they cannot be found in their domestic market, they will need to acquire them elsewhere (Choi & Salehyan, Citation2013; Fearon & Laitin, Citation2003; Hazen, Citation2013). This clearly applies to JNIM as the group has consistently expanded its area of operation towards the Sahel’s artisanal gold mines in order to secure income (Kone, Citation2021). Regarding ideology, studies highlight ideological reasons as a necessary driving element for operating abroad (Ahmad, Citation2016; Crenshaw, Citation2017, Citation2020; Hegghammer, Citation2011). When JNIM was formed, al-Qaeda claimed that expansion in the Sahara-Sahel region was a crucial effort in Muslim history (Forbes, Citation2018).

Terrorist groups with connections, funding and capabilities can fill the demand in areas that have a need for services terrorist groups can offer (Bencherif, Citation2021; Skretting, Citation2020; Thurston, Citation2020). JNIM interacts with criminal networks offering them expertise, funding and materiel (International Crisis Group, Citation2018). In Burkina Faso, JNIM has co-opted local armed bandits with heavy weaponry and payments in order to facilitate entrance into foreign areas further expanding the group’s area of operations (International Crisis Group, Citation2018).

In order to survive, terrorist groups will move to foreign territories when faced with pressure from state authorities (Beardsley et al., Citation2015; Dowd & Raleigh, Citation2013). As mentioned above, GSPC expanded to Mali to avoid crackdowns from Algerian authorities (Forbes, Citation2018). Byman shows that parent – affiliate relationships are at risk of losing terrain to rivals and that competitors can fight their way into a market (Byman, Citation2014). Indeed, JNIM expanded its territory in the Sahel by pushing out ISGS in the border region between Mali and Niger (Hansen, Citation2019). Bove and Böhmelt theorise that the social ties and social capital of migration flows are exploited by terrorist groups as they plan their future activities (Bove & Böhmelt, Citation2016). Indeed, proximity to intra-African migration routes gave JNIM opportunities to increase their ability to communicate, attract recruits, and move throughout Africa through such diaspora connections (Estelle, Citation2021).

Evidence of a role for pull factors

Areas with flourishing black markets can attract both terrorist and organised crime groups (Haidar, Citation2019; Makarenko, Citation2004; Roberts, Citation2016). Libya’s conflict created large black markets proliferating weapons across the region, giving JNIM revenue streams from smuggling and linking them with jihadist networks across the region (Spittaels et al., Citation2017). Indeed, areas with established illicit trade and trafficking routes have historically attracted organised crime groups and could play a role in attracting terrorist groups (Idler, Citation2012; Kenney, Citation2021). Throughout the Sahara-Sahel region, smuggling, drug trafficking, and related organised crime generates financial resources for armed groups in general and JNIM specifically (International Crisis Group, Citation2018; United Nations, Citation2017). Good relations with organised crime groups with access to international trafficking routes have proven essential for JNIM (CISAC Stanford, Citation2018; International Crisis Group, Citation2018). Moreover, JNIM controls, protects and taxes routes between international smuggling hubs generating significant income (International Crisis Group, Citation2018; NATO - JFC Naples, Citation2020).

Areas with high unemployment and disenfranchised groups can be a fertile recruitment and mobilisation ground for terrorist groups (Abrahms, Citation2008; Falk et al., Citation2011; Humphreys & Weinstein, Citation2008; Roberts, Citation2016). Al-Qaeda views the wider Sahara-Sahel region as vulnerable and susceptible for its operations due to ongoing ethnic strife and having a large population that is disaffected with their government (Forbes, Citation2018; Skretting, Citation2020). Since 2007, al-Qaeda focused on cultivating local support, mobilising disenfranchised populations and linking local grievances with its global expansionist agenda (Forbes, Citation2018; Hansen, Citation2019; Skretting, Citation2020).

Areas with traditional low-technology economic sectors may be more vulnerable to terrorist and organised crime group penetration (Lavezzi, Citation2008). Although there is little research linking this factor to terrorist expansion specifically, we can theorise that findings from organised crime literature are possibly applicable to terrorist groups as well (Calderoni et al., Citation2016). Vast swaths of areas in the Sahel and Libya are sparsely populated, with farming communities giving JNIM opportunities to infiltrate, recruit and profit (Assanvo et al., Citation2019). By offering a modicum of structure and modernity, JNIM managed to spread across low-technology communities in the Sahel, effectively becoming service and protection-providing monopolists (Hansen, Citation2019). According to Hansen, the economic boom in unregulated artisanal mining in Mali attracted JNIM who seeks to control mining activities (Hansen, Citation2019; Kone, Citation2021).

When terrorist groups lack resources and capabilities in their native environment, studies show they will seek areas and partners that can remedy their deficits (Bacon, Citation2013). The criminal and unregulated economies in parts of Africa have led to lucrative markets from which JNIM obtained resources and funds. Terrorist groups compete for (political) market share and seek resources and capabilities at each other’s expense in the same conflict market (Bacon, Citation2013; Hoffman, Citation2003; McCormick, Citation2003). Areas with no or few competitors in the Sahel offered AQIM and subsequently JNIM opportunities to become virtual monopolists in violence and providers of security (Skretting, Citation2020).

Alliances with local power brokers and facilitators can make it easier for terrorist groups to operate in foreign territories (Bencherif, Citation2021; Byman, Citation2014; Thurston, Citation2020). JNIM extensively partners with local sympathisers and facilitators granting them access to new areas (Hansen, Citation2019; Skretting, Citation2020). Areas with low societal and institutional trust push populations to search for alternative modes of security giving terrorist groups opportunities to provide protection services (Cragin, Citation2007; Freilich et al., Citation2015; Haidar, Citation2019; Widner, Citation2010). JNIM offers civilians in their areas of control a degree of security and dispute resolution, albeit under their interpretation of Sharia law (Hansen, Citation2019; SITE, Citation2017).

Like organised crime groups, terrorists can find support and recruits in marginalised ethnic groups by offering socioeconomic opportunities and prestige (Albanese, Citation2010, Citation2011; Cline, Citation2021; Finckenauer & Waring, Citation1998; Ianni, Citation1974; Jourde, Citation2017). Many Libyan veterans of the 1980s Soviet invasion of Afghanistan became AQIM members. They rose to legitimate political positions after leveraging their jihadist connections against Gadhafi in 2011 (Wehrey, Citation2018). By joining the fight against Gadhafi, AQIM seemed a legitimate security provider offering a way out of government marginalisation to tribes and clans who supported them (Wehrey, Citation2018).

Areas with open borders and sympathetic diasporas with desires to join or support terrorist groups can provide fertile grounds for their expansion (Asal et al., Citation2007; Assanvo et al., Citation2019; Meehan, Citation2004; Wayland, Citation2004). JNIM is able to control smuggling routes, tax and offer protection to communities because it is rooted in Sahrawi, Tuareg and Arab communities giving the group family and tribal links throughout the region (Lacher, Citation2012). Kinship support links have been suggested to play a role in the ability of terrorist groups to expand into areas where ties are strong (Hansen, Citation2019; NATO - JFC Naples, Citation2020; Ronfeldt, Citation2005). According to Skretting and Hansen, JNIM’s ethnic subgroups stretch across vast areas of the Sahara-Sahel possessing varying ethnic and criminal affiliations (Hansen, Citation2019; Skretting, Citation2020). This has provided al-Qaeda, through JNIM, with a significant geographical and social reach.

JNIM thrives in unregulated sectors obtaining its funding from criminal activities including kidnapping for ransom, trafficking of drugs, people, and arms, taxation, provision of services, protection and exploitation of the region’s unregulated artisanal gold mines (Boeke, Citation2016; CISAC Stanford, Citation2018; Kone, Citation2021; Skretting, Citation2020). On corruption and government ineffectiveness, studies have stressed that areas with weak state structures allow terrorist groups to find sanctuaries and subsequently profit from the lawlessness found therein (Boeke, Citation2016; Cragin et al., Citation2007; Fearon, Citation2017; Piazza, Citation2008; Skretting, Citation2020). JNIM provides an alternative form of governance and rule of law in areas where the state fails to do so and in areas where state authorities marginalise specific ethnic groups. According to Hansen, JNIM champions al-Qaeda’s goal of cultivating support for the implementation of Sharia law through religious education, outreach from its religious leaders, and the provision of legal services and protection (Hansen, Citation2019).

Evidence of a role for constraining factors

Studies find that parent terrorist groups have difficulties in monitoring and controlling their agents in foreign territories (Byman, Citation2014; Mendelsohn, Citation2018; Shapiro, Citation2013). For example, AQIM could not control Abu Walid al-Sahrawi as he split from AQIM pledging allegiance to Islamic State and creating ISGS in 2015 (Hansen, Citation2019). Also, studies find that terrorist groups face difficulties in (covertly) communicating and controlling their members and affiliates (Mendelsohn, Citation2018; Perkoski, Citation2019; Shapiro, Citation2013). In order to organise and coordinate activities, AQIM used letters and, when possible, in-person meetings in addition to other (covert) methods of communication (Bencherif, Citation2021). Despite their best efforts in utilising operational security methods, AQIM’s former leader, Abdelmalek Droukdel, was eliminated by French forces in 2020.

Finally, studies point to the necessity of having access to high-quality local information in foreign areas to understand the operating environment (Moghadam, Citation2017; Moghadam & Wyss, Citation2020). JNIM actively recruits from domestic organised crime groups that are familiar with the areas and have domestic tribal and familial ties (Boeke, Citation2016; D’Amato, Citation2018). According to Mendelsohn, many terrorist groups face difficulties in managing their reputation in foreign territories making them often unable to exercise control over their offshoots (Mendelsohn, Citation2016, 2018). In this regard, JNIM has significant autonomy from al-Qaeda in their decision-making as long as it follows general al-Qaeda guidance and doctrine (Larémont, Citation2011). Summarising the above, we can fill in for JNIM.

Table 2. Summary of the push and pull dynamics together with the command-and-control factors for JNIM.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article addressed why some terrorist groups, despite existing barriers, expand outside their native area of operation. By drawing from the field of criminology in which transnational expansion was studied primarily in relation to organised crime, we have attempted to construct an integrated, criminology-based transplantation framework that can be applied to the study of terrorism. In order to test the framework, we have systematically applied it in an exploratory way and based on open sources to al-Qaeda in the Sahara-Sahel. This first preliminary test has demonstrated the potential value of applying transplantation theory to the analysis of terrorist group transplantation across national borders. By reviewing relevant criminological approaches and empirical studies on organised crime and by integrating the emergent and strategic positions from the transplantation literature, we have developed a conceptual taxonomy that serves as a foundation for future more rigorous empirical investigations into terrorist group transplantation.

The preliminary application of this taxonomy to the case of al-Qaeda and its regional affiliate, JNIM, has provided initial evidence that the transplantation framework can offer valuable insights into the dynamics of terrorist group expansion and the factors that drive their transnational operations. Our findings further suggest that, much like organised crime groups, terrorist groups face similar challenges and operate in comparable ways when expanding across borders. This underscores the relevance of utilising the transplantation literature in advancing our understanding of transnational terrorist group dynamics. By bridging the gap between the study of organised crime groups and terrorist groups, we hope to pave the way for future interdisciplinary research that can yield novel insights and foster a more comprehensive understanding of the factors and mechanisms that facilitate the spread of these groups across borders.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the present study, which include the reliance on open sources and academic literature, as well as the focused nature of the analysis. Future research should aim to incorporate a wider array of primary data sources and expand the scope of analysis to include additional case studies of terrorist group transplantation. Moreover, a more in-depth examination of the interactions between emergent and strategic factors in driving terrorist group expansion is warranted. Ultimately, the development and application of the transplantation framework to the study of terrorist groups hold significant promise for advancing our understanding of the complex processes underpinning the transnational spread of terrorism.

In our study, we primarily concentrated on Rational Choice Theory based approaches focusing on specific crimes and terrorist activities. However, we recognise the potential value of incorporating other criminological theories, such as strain theory and social control theory, especially when applying our model more comprehensively to case studies with extensive data. This approach broadens the scope for future research, enabling a deeper exploration into the reasons for the cross-border expansion of groups, the driving forces behind their movements, and the strategies terrorist groups use to adapt to new settings.

One critical domain for future research is the empirical validation of our conceptual taxonomy through a diversified case study approach. This would involve examining a wider array of terrorist groups with varying ideologies and operational tactics. For example, the transnational activities of far-right extremist groups, particularly their interaction with transnational conspiracies and expansion throughout the West, offer a fertile ground for comparison and contrast with jihadist networks. In addition, the investigation of groups like the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM) presents an opportunity to explore the intersection of transnational ideology, such as Pan-Slavism, with organised crime dynamics. Given the RIM’s designation by the United States as a terrorist organisation, a case study could provide nuanced insights into the operational similarities and differences between traditional organised crime groups and ideologically motivated terrorists.

Finally, to address the literature gaps, we propose an empirical approach that includes mixed-methods research combining quantitative data analysis with qualitative fieldwork. Incorporating interviews with law enforcement and intelligence professionals, as well as potentially reformed former members of these groups, can offer depth to our understanding of the motivations and mechanisms of transnational expansion. Moreover, leveraging digital ethnography to analyse online communications and social media platforms could provide a window into the recruitment, propaganda, and networking strategies of these groups. This approach is particularly pertinent given the increasing importance of the internet in facilitating transnational connections. By incorporating these suggestions into future research endeavours, we aim to construct a more comprehensive and empirically grounded understanding of terrorist transplantation.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. No external funding was received for this research.

References

- Abrahms, M. (2008). What terrorists really want: Terrorist motives and counterterrorism strategy. International Security, 32(4), 78–105. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.32.4.78

- Ahmad, A. (2016). Going global: Islamist competition in contemporary civil wars. Security Studies, 25(2), 353–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2016.1171971

- Albanese, J. S. (2010). Organized crime in our times. Routledge.

- Albanese, J. S. (2011). Transnational crime and the 21st century: Criminal enterprise, corruption, and opportunity. Oxford University Press.

- Albini, J. L. (1971). The American mafia: Genesis of a legend. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Albini, J. L. (1988). Donald Cressey’s contributions to the study of organized crime: An evaluation. Crime & Delinquency, 34(3), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128788034003008

- Allum, F. (2014). Understanding criminal mobility: The case of the Neapolitan camorra. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 19(5), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2014.962257

- Arsovska, J. (2016). Strategic mobsters or deprived migrants? Testing the transplantation and deprivation models of organized crime in an effort to understand criminal mobility and diversity in the United States. International Migration, 54(2), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12217

- Asal, V., Nussbaum, B., & Harrington, D. W. (2007). Terrorism as transnational advocacy: An organizational and tactical examination. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism Taylor & Francis, 30(1), 15–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100600959713

- Assanvo, W. (2019). Violent extremism, organised crime and local conflicts in Liptako-Gourma. ISS West Africa Report, 2019(26), 1–23. Available at https://issafrica.org/research/west-africa-report/violent-extremism-organised-crime-and-local-conflicts-in-liptako-gourma

- Bacon, T. L. (2013). Strange bedfellows or brothers-in-arms: Why terrorist groups ally. Georgetown University.

- Beardsley, K., Gleditsch, K. S., & Lo, N. (2015). Roving bandits? The geographical evolution of African armed conflicts. International Studies Quarterly, 59(3), 503–516. Blackwell Publishing Ltd Oxford, UK. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12196

- Beevor, E. (2022). JNIM in Burkina Faso: A Strategic Criminal Actor. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC). https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Burkina-Faso-JNIM-29-Aug-web.pdf

- Bell, D. (1953). Crime as an American way of life. The Antioch Review, 13(2), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.2307/4609623

- Bell, D. (2000). The end of ideology: On the exhaustion of political ideas in the fifties: With“The resumption of history in the new century”. Harvard University Press.

- Bencherif, A. (2021). Unpacking “glocal” jihad: From the birth to the “sahelisation’ of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 00(00), 1–19. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2021.1958171

- Bergen, P. L. (2002). Holy war, Inc. : Inside the secret world of Osama bin Laden. And u. Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books.

- Berrebi, C., & Lakdawalla, D. (2007). How does terrorism risk vary across space and time? An analysis based on the Israeli experience. Defence and Peace Economics, 18(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690600863935

- Bøås, M. (2015). Crime, coping, and resistance in the Mali-Sahel periphery. African Security, 8(4), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.1100506

- Boeke, S. (2016). Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb: Terrorism, insurgency, or organized crime? Small Wars & Insurgencies, 27(5), 914–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1208280

- Boeke, S. (2022) Understanding Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb: Responses to Terrorist Tactics and Insurgent Strategies. Leiden University. https://books.google.nl/books?id=TYhDzwEACAAJ

- Bove, V., & Böhmelt, T. (2016). Does immigration induce terrorism? The Journal of Politics, 78(2), 572–588. University of Chicago Press Chicago, IL. https://doi.org/10.1086/684679

- Bovenkerk, F., Siegel, D., & Zaitch, D. (2003). Organized crime and ethnic reputation manipulation. Crime, Law, & Social Change, 39(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022499504945

- Braithwaite, J. (1989). Criminological theory and organizational crime. Justice Quarterly, 6(3), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418828900090251

- Braithwaite, A., & Li, Q. (2007). Transnational terrorism hot spots: Identification and impact evaluation. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 24(4), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940701643623

- Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (1981). Environmental criminology. Sage Publications Beverly Hills.

- Buffa, C. (2022). Predicting terrorism in Europe with remote sensing, spatial statistics, and machine learning. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(4), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11040211

- Byman, D. (2014). Buddies or burdens? Understanding the Al Qaeda Relationship with its affiliate organizations. Security Studies, 23(3), 431–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2014.935228

- Calderoni, F. (2016). The Italian mafias in the world: A systematic assessment of the mobility of criminal groups. European Journal of Criminology, 13(4), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815623570

- Campana, P. (2011). Eavesdropping on the mob: The functional diversification of mafia activities across territories. European Journal of Criminology, 8(3), 213–228. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811403442

- Castells, M. (2010). End of millennium. John Wiley & Sons.

- Choi, S.-W., & Salehyan, I. (2013). ‘No good deed goes unpunished: Refugees, humanitarian aid, and terrorism’. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 30(1), 53–75. Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894212456951

- CISAC Stanford. (2018) Mapping Militants JNIM. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/jamaat-nusrat-al-islam-wal-muslimeen

- Clarke, R. V. (2009). Situational crime prevention: Theoretical background and current practice. In M. D. Krohn,A. J. Lizotte,& P. H. Gina (Eds.), Handbook on crime and deviance (pp. 259–276). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0245-0_14

- Clarke, R. V. G., & Newman, G. R. (2006) Outsmarting the Terrorists. Praeger Security International (Global Crime and Justice). https://books.google.be/books?id=nkP9aU1dMFQC

- Cline, L. E. (2021). Jihadist movements in the Sahel: Rise of the Fulani?. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1888082

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

- Cragin, K. (2007). Sharing the dragon’s teeth. Terrorist groups and the exchange of new technologies. https://doi.org/10.7249/MG485

- Cragin, K., Chalk, P., Daly, S. A., & Jackson, B. A. (2007). Sharing the Dragon’s Teeth: Terrorist Groups and the Exchange of New Technologies. Report No. 485. Rand Corporation.

- Crenshaw, M. (2017). Transnational jihadism & civil wars. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 146(4), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00459

- Crenshaw, M. (2020) Rethinking Transnational terrorism. United States Institute of Peace Peaceworks. (p. 158). https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/02/rethinking-transna-tional-terrorism-integrated-approach?fbclid=IwAR0gJdLUwfSSNkMfMfZXrCQqF6c-jrLAVSPZEYwp1ja5B-ZQneM9ZCdLns8Q

- Cressey, D. R. (1969). Theft of the nation: The structure and operations of organized crime in America. Transaction Publishers.

- Cristiani, D., & Fabiani, R. (2011). Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM): Implications for Algeria’s regional and international relations. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

- D’Amato, S. (2018). Terrorists going transnational: Rethinking the role of states in the case of AQIM and Boko Haram. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 11(1), 151–172. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2017.1347238

- Dowd, C., & Raleigh, C. (2013). The myth of global Islamic terrorism and local conflict in Mali and the Sahel. African Affairs, 112(448), 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adt039

- Eizenga, D. (2020). Puzzle of JNIM and militant Islamist groups in the Sahel. Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

- Estelle, E. (2021) Why experts ignore terrorism in Africa. (p. 2021). https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/19/why-experts-ignore-terrorism-in-africa/

- Fahey, S. (2012). A situational model for distinguishing terrorist and non-terrorist aerial hijackings, 1948–2007. Justice Quarterly, 29(4), 573–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.583265

- Falk, A., Kuhn, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2011). Unemployment and right‐wing extremist crime. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(2), 260–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2011.01648.x

- Fearon, J. D. (2017). Civil war & the current international system. Dædalus, 146(4), 18–32. MIT Press One Rogers Street, Cambridge, MA USA journals-info. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00456

- Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. The American Political Science Review, 97(1), 75–90. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000534

- Felson, M., & Clarke, R. V. (2011). The Origins of the Routine Activity Approach and Situational Crime Prevention. In F. T. Cullen,C. Lero Johnson,A. J. Myer,& F. Adler (Eds.), The Origins of American Criminology (1st ed., pp. 245–260). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315133683-12/origins-routine-activity-approach-situational-crime-prevention-ronald-clarke-marcus-felson

- Filiu, J.-P. (2009). The local and global jihad of al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghrib. The Middle East Journal, 63(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.3751/63.2.12

- Finckenauer, J. O., & Waring, E. J. (1998). Russian mafia in America: Immigration, culture, and crime. Upne.

- Forbes, J. (2018). Revisiting the Mali al-Qàida playbook: How the group is advancing on its goals in the Sahel. CTC Sentinel, 11(9), 18–21.

- Forest, J. J. F., & Giroux, J. (2011). Terrorism and political violence in Africa: Contemporary trends in a shifting terrain. Perspectives on Terrorism, 5(3/4), 5–17.

- Freilich, J. D. (2015). Investigating the applicability of macro-level criminology theory to terrorism: A county-level analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 31(3), 383–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9239-0

- Freilich, J. D., & Lafree, G. (2015). Criminology theory and terrorism: Introduction to the special issue. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.959405

- Freilich, J. D., & LaFree, G. (2016). Measurement issues in the study of terrorism: Introducing the special issue. Taylor & Francis.

- Freilich, J. D., & Newman, G. R. (2009). Reducing terrorism through situational crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press. https://www.popcenter.org/sites/default/files/library/crimeprevention/volume_25/00-FrontMatter.pdf

- Galeotti, M. (2000). The Russian mafia: Economic penetration at home and abroad. In A. Ledeneva & M. Kurkchiyan (Eds.), Economic crime in Russia. Springer Netherlands. https://books.google.je/books?id=WHMEAQAAIAAJ

- Gambetta, D. (1993). The Sicilian mafia : The business of private protection. Harvard University Press.

- Gill, P., Horgan, J., & Corner, E. (2019). The rational foraging terrorist: Analysing the distances travelled to commit terrorist violence. Terrorism and Political Violence, 31(5), 929–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1297707

- Haidar, L. (2019). The emergence of the mafia in Post-War Syria: The Terror-Crime Continuum. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 0(0), 1–16. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1678869

- Hansen, S. J. (2019). Horn, Sahel and Rift : Fault-lines of the African jihad. Hurst & Company.

- Hazen, J. M. (2013). What rebels want: Resources and supply networks in wartime. Cornell University Press.

- Hegghammer, T. (2011). Jihad in Saudi Arabia. Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979. Politique etrangere, 1(1), 198–201. https://doi.org/10.3917/pe.111.0198

- Helfstein, S., & Wright, D. (2011). Success, lethality, and cell structure across the dimensions of Al Qaeda. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 34(5), 367–382. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2011.561469

- Hoffman, B. (2003). The logic of suicide terrorism. Rand Santa Monica.

- Humphreys, M., & Weinstein, J. M. (2008). Who fights? The determinants of participation in civil war. American Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 436–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00322.x

- Ianni, F. A. J. (1974). Black mafia; ethnic succession in organized crime. Simon & Schuster.

- Ianni, F. A. J., & Reuss-Ianni, E. (1972). A family business: Kinship and social control in organized crime. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Idler, A. (2012). Exploring agreements of convenience made among violent non- state actors. Perspectives on Terrorism, 6(4–5), 63–84.

- International Crisis Group. (2018). Drug trafficking, violence and politics in northern Mali. Report No. 267. https://icg-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/267-drug-trafficking-violence-and-politics-in-northern-mali-english.pdf

- Jordán, J. (2014). The evolution of the structure of jihadist terrorism in Western Europe: The case of Spain. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 37(8), 654–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.921770

- Jourde, C. (2017). How Islam intersects ethnicity and social status in the Sahel. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(4), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1361016

- Kenney, M. (2021). From Pablo to Osama. Penn State University Press.

- Kohlmann, R., & Pantucci, E. (2010). Bringing global jihad to the Horn of Africa: Al Shabaab, Western Fighters, and the sacralization of the Somali conflict. African Security, 3(4), 216–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2010.533071

- Kone, F. R. (2021). How western Mali could become a gold mine for terrorists.

- Lacher, W. (2012). Organized crime and conflict in the Sahel-Sahara region. Report No. 13. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep12951.pdf

- Larémont, R. R. (2011). Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb: Terrorism and counterterrorism in the Sahel. African Security, 4(4), 242–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2011.628630

- Lavezzi, A. M. (2008). Economic structure and vulnerability to organised crime: Evidence from Sicily. Global Crime, 9(3), 198–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570802254312

- Lavorgna, A., Lombardo, R., & Sergi, A. (2013). Organized crime in three regions: Comparing the Veneto, Liverpool, and Chicago. Trends in Organized Crime, 16(3), 265–285. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-013-9189-1

- Le Roux, P. (2019 https://africacenter.org/spotlight/confronting-central-malis-extremist-threat/,). Confronting central Mali’s extremist threat. Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

- Lombardo, R. M. (2012). Organized crime in Chicago: Beyond the mafia. University of Illinois Press.

- Lynch, J. P. (2011). ‘Implications of opportunity theory for combating terrorism’, criminologists on terrorism and homeland security. Cambridge University Press.

- Makarenko, T. (2004). The Crime-Terror Continuum: Tracing the interplay between transnational organised Crime and terrorism. Global Crime, 6(1), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744057042000297025

- Mazerolle L., and Wortley R. (Eds.), (2013). Environmental criminology and crime analysis: situating the theory, analytic approach and application. In Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis (pp. 23–40). Willan. 9780203118214.

- McCormick, G. H. (2003). Terrorist decision making. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1), 473–507. Annual Reviews 4139 El Camino Way, PO Box 10139, Palo Alto, CA 94303-0139, USA. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085601

- McIntosh, C. N., & Lawrence, A. (2011). Spatial mobility and organised crime. Global Crime, 12(3), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2011.589250

- McWeeney, S. M. (1987). The Sicilian Mafia and its impact on the United States. FBI L. Enforcement Bull, 56. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/fbileb56&div=13&id=&page=

- Meehan, H. V. (2004). Terrorism, diasporas, and permissive threat environments: A Study of Hizballah’s Fundraising Operations in Paraguay and Ecuador Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey. Naval Postgraduate School. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=00d9661cf65693483de92018eb613b95acea9ac4

- Mendelsohn, B. (2016). The Al-Qaeda Franchise: The expansion of Al-Qaeda and its consequences. Oxford University Press.

- Mendelsohn, B. (2018). Jihadism constrained: The limits of transnational jihadism and what it means for counterterrorism. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Moghadam, A. (2017). Nexus of global jihad understanding cooperation among terrorist actors. Columbia University Press.

- Moghadam, A., & Wyss, M. (2020). The political power of proxies: Why nonstate actors use local surrogates. International Security, 44(4), 119–157. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00377

- Moon, I.-C., & Carley, K. M. (2007). Modeling and simulating terrorist networks in social and geospatial dimensions. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 22(5), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2007.4338493

- Moro, F. N., & Villa, M. (2017). The new geography of mafia activity. The case of a northern Italian region. European Sociological Review, 33(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw046

- Morselli, C., Turcotte, M., & Tenti, V. (2011). The mobility of criminal groups. Global Crime, 12(3), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2011.589593

- NATO - JFC Naples. (2020) Terrorism in the Sahel: Facts and figures - Progress Report (UNCLASS).