ABSTRACT

India’s experience with the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) is notable on account of nationally formalising – at scale – community action in service delivery, monitoring, and planning of health services. A study was undertaken to document and create a historical record of NRHM’s ‘communitization’ processes. The oral history method of the Witness Seminar was adopted and two virtual seminars with five and nine participants, respectively, were conducted, and supplemented with 4 in depth interviews. Analysis of transcripts was done using ATLAS.ti 22 with the broad themes of emergence, evolution, and evaluation and impact of ‘communitization’ under NRHM. This paper engages with the theme of ‘emergence’ and adopts the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) conceptualised by John Kingdon for analysis. Key findings include the pioneering role of boundary spanning decision makers and the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA) in advocacy and design of ‘communitization’ structures, and the legacy of rights based social mobilizations and state-civil society partnerships in health during the 1990s influencing the ethos underlying ‘communitization’. Democracy, leadership from the civil society in policy design and implementation, and state-civil society partnerships are linked to the positive results witnessed as part of ‘communitization’ in NRHM.

Introduction

The global discourse on health equity and accessibility to health services is now increasingly linked to Universal Health Coverage (UHC), enshrined in United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.8. The UHC agenda is increasingly seen as being tied to community participation following from the legacy of the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration on Health for All (Allotey et al., Citation2019; Rifkin, Citation2009; United Nations, Citationn.d.). It is argued that integrating meaningful community participation through adequate funding support, and ensuring transparent and accountable governance mechanisms, allow health and wellbeing to be co-produced by various actors in the health system, thus paving the way for UHC (Odugleh-Kolev & Parrish-Sprowl, Citation2018). There is growing evidence that links community participation to improved health outcomes and health systems, including accountability (Allotey et al., Citation2019; Rifkin, Citation2014). Examples demonstrating the linkages between UHC and participatory spaces include the government civil-society dialogues for developing and adopting the National Health Financing Strategy for Universal Health Coverage (SNFS-CSU in French acronym) in Burkina Faso, and the National Health Security Act in Thailand mandating the representation from the civil society in its decision-making board for the Universal Coverage Scheme, among others (World Health Organization, Citation2021). This evidence is critical to gaining the consensus of government decision-makers to work collaboratively towards institutionalising community participation in health programmes (Rifkin, Citation2014).

Global commitment towards integrating community participation in policy and practice over the years has witnessed an evolution in the concept of community participation (Morgan, Citation2001; Rifkin, Citation2009) and a 2019 systematic review presents a conceptual model to frame the varied outcomes of community participation interventions (Haldane et al., Citation2019). With popularization of the human rights and empowerment frameworks, initiatives have evolved from merely engaging beneficiaries in development projects to involving communities in decision-making and enabling the opportunity to understand how governments and institutions fulfil their obligations towards the right to health’ (Hunt & Backman, Citation2008). This can be traced to literature from development aid that emphasises on understanding and transforming power relationships among actors to translate concepts of trust, inclusion accountability and partnerships into practice (Chambers, Citation2013; Cornwall & Gaventa, Citation2001; Gaventa, Citation2002). Gaventa (Citation2002) draws on Cornwall and Gaventa (Citation2001) to echo the importance of situating participation and institutional accountability in a conception of rights that ‘strengthens the status of citizens from that of beneficiaries of development to its rightful and legitimate claimants’ (Gaventa, Citation2002, p. 1). The grounding of community participation in human rights stresses the state’s critical role in fulfilling the right to health of people through the establishment of accountability mechanisms – acting as spaces for government to ‘explain and justify, to rights-holders and others, how they have fulfilled or failed to fulfil obligations regarding participation’ (De Vos et al., Citation2009, p. 26). It is important to also underscore the critical role that civil society groups and organisations play in advocacy, holding governments accountable, and facilitating engagements of the public with state services (Hassell et al., Citation2020).

In India, the legacy of community participation in health and health reform precedes Independence and has been long-standing with initiatives such as the Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) experience of 1970 which later fed into Alma Ata’s concepts and principles (Perry & Rohde, Citation2019). In the late 1970s, as the Emergency gripped the country, foreign funders began to support a number of voluntary agencies to keep the focus on welfare, development and democratic imperatives, creating a civil society groundswell which in turn was part of the global discourse on community participation in health by the time of the Alma Ata Declaration (Asian Development Bank, Citation2009; Kocher, Citation1980). The Declaration’s influence on India’s policy thought is reflected in the sixth five-year plan of 1980-1985, which emphasised the development of a community-based health system (Duggal, Citationn.d.). A series of developments in policy and legislations of the 90s, such as the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, the New Economic Policy, and the International Conference on Population and Development, set the stage for radical shifts in how community participation was articulated in health policy reforms (Duggal, Citation1998; Srinivasan et al., Citation2007). The late 1990s were also characterised by civil society’s increasing involvement in policy implementation. The second phase of the 1999 National AIDS Control Programme witnessed the establishment of mechanisms by the government to engage community members and civil society in health programme activities (Lahariya et al., Citation2020).

A more fundamental and systematic policy reform in this direction arrived in 2005 with the Government of India launching the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). ‘Communitization’Footnote1 is one of five major pillars of NRHM, intended to institutionalise a rights-based approach to health and the sharing of political, administrative and budgetary decision-making power with communities. Noteworthy is the pivotal role played the civil society in implementing the programme of ‘communitization’ (Lahariya et al., Citation2020)

Between 2007 and 2009, the central government funded a pilot project – spearheaded by the Advisory Group on Community Action (AGCA) – to help state governments learn about ‘communitization’ activities and adopt them before spearheading their post-pilot implementation and upscaling. 1,620 villages of 36 districts across the states of Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu were selected to participate in the pilot phase (Lahariya et al., Citation2020). Evaluations of this phase have found that the communitization activities showed promise; they enhanced community awareness of their health entitlements, immunisation and antenatal care service coverage, and medicine and lab service availability, while empowering marginalised community members as part of VHSNCs (Lahariya et al., Citation2020; Srivastava et al., Citation2015). On account of ‘wins’ that took place during the pilot phase, the NRHM’s communitization has been scaled up; in 2018-2019, the AGCA supported 24 states in activity implementation (Lahariya et al., Citation2020). Notably, in 2013, the NRHM was subsumed under the National Health MissionFootnote2 (NHM) (Lahariya et al., Citation2020).

India has important lessons for itself and the world from its experience of institutionalising community participation and action as part of the NRHM with groundings in a human rights-based framework. Barring a few exceptions (Lahariya et al., Citation2020; Planning Commission of India, Citation2011; Ved et al., Citation2019), however, such documentation and literature are piecemeal. Indeed, learnings from the NRHM’s communitization activities can be applied to strengthen the involvement of non-governmental stakeholders in other flagship initiatives such as the Ayushman Bharat Programme launched in 2018 (Lahariya, Citation2018). We attempted to create an archive to increase our depth of understanding co-constructed with key actors who played pioneering roles in advocating for, designing, and implementing a rights-based framework within the ambit of NRHM to engage communities in health programmes and systems governance. In addition to limited documentation of the lessons from NRHM, specifically ‘Communitization’, literature presenting an analytical understanding of the context-specific influences on the culmination of advocacy and political currents into the NRHM is limited. Thus, the analysis presented in this paper is an attempting at addressing this gap.

In the subsequent sections, we describe the method of conducting the two Witness Seminars focussing on the emergence of the ‘Communitization’ framework as part of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). This is followed by an analysis of the Witness Seminar verbatims using John Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework (MSF). Prior to delving into the analysis we also provide a snapshot of the MSF.

Method

The Witness Seminar methodology was adopted to carry out the documentation of community participation and action in health under India’s NRHM. Witness Seminar is an oral history methodology which involves inviting persons bearing direct witness to a past event to share their perspectives around that event, and discuss, debate, and agree or disagree with each other’s views (Berridge & Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine Citation2006; Chakravarti & Hunter, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Christie & Tansey, Citation2001). In 2021, we organised two Witness Seminars to document experiences of designing and implementing models of community participation and community accountability mechanisms institutionalised under India’s NRHM. During preparatory consultations with the participants, they had indicated that following the aforementioned thematic sequence would serve the purpose of the Witness Seminar better, i.e. in understanding the institutionalisation of the ‘Communitization’ framework under the NRHM. This paper is dedicated to focusing on the theme of ‘emergence’ in order to capture the antecedents in detail with a separate paper focusing on the themes of ‘evolution and institutionalisation’, and evaluation and impact.

We have adapted the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist to report the methodology adopted for this study (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Participant selection

Sampling: Based on the remit of the Witness Seminars, we intended to identify potential witnesses involved in the advocacy, design, and implementation of the ‘communitization’ related processes as part of NRHM at the national level. We went through publicly available sources to identify the witnesses and using a snowballing technique, also reached out to prospective witnesses through our (researchers’) networks. The identified persons included civil society members, retired government officials, researchers, practitioners, and advisors who were closely involved with the policy processes of the NRHM at the national level (). We selected a chairperson, who has long engaged with health systems and policy processes in the Indian context, to steer the Witness Seminar proceedings.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.Footnote3

Recruitment: Potential participants (witnesses) were approached through email and telephone. They were introduced to the theme and methodology via a detailed concept note covering the specifics of the research study. We held one-on-one virtual conversations with all the witnesses to orient them with details of the theme, and method, and collate their feedback on our overall approach to the documentation work.

Sample size and non-participation: Fifteen witnesses participated in the Seminars – nine in the first Seminar and five in the second. There were 5 women out of the 15 participants in the Witness Seminars including the in-depth interviews conducted to supplement the seminars. The sample size was chosen based on two considerations: (i) number of participants recruited as witnesses in Witness Seminars conducted in India on health; (ii) to have adequate representation from civil society and decision makers who witnessed the genesis of NRHM. Two supplementary in-depth interviews were conducted with two participants from the first Witness Seminar. As part of the second witness seminar, a supplementary in-depth interview was conducted with a participant who couldn’t participate in the main Seminar session and one interview was conducted with a participant from the main Seminar. One out of the 10 original participants from the first Witness Seminar requested retraction of their contributions and was designated an ‘anonymous observer’ of the Seminar proceedings and one participant from the first seminar who participated in an in-depth interview requested anonymity and the transcript wasn’t made available publicly, and anonymity was retained during analysis.

Data collection

The dates and times of the Seminars were finalised in consultation with the witnesses, each Seminar lasting roughly 1.5 h. Three chronological themes were delineated vis-à-vis the (a) emergence; (b) evolution and institutionalisation; and (c) evaluation and impact of the community-based accountability processes institutionalised under NRHM.

We loosely structured the sessions by listing nine questions, i.e. three questions for each of the thematic areas, and slotting witnesses against the questions according to relevance to their experience. This agenda – prepared in consultation with the chairperson – was shared with the witnesses in advance to help orient them in preparing for the session. We had also circulated the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and consent form with the witnesses in advance of the Seminars. The Seminars were complemented by three follow-up interviews with witnesses and one potential witness who could not attend the proceedings. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we organised the sessions online via Zoom. The virtual mode and relatively short duration of the Seminars were convenient in terms of attendance but did introduce some constraints in terms of flow and duration of the sessions. Typically, Witness Seminars can be up to five or six hours in duration with multiple speakers interrupting and speaking on multiple occasions, whereas our virtual seminars were at most two hours in duration and typically involved a sequential panel presentation format, with some interjections and additions at the end. We observed that having nine participants during the first Witness Seminar of 1.5 h couldn’t allow for unpacking of many of the threads emerging as part of the discussions and thus having five participants during the second seminar helped us close that gap. Data saturation was at the discretion of Chairs who could ask any participant to expand or elaborate. Further, the Witness Seminar reports were primary outputs and our analysis was a secondary exercise conducted prospectively after the completion of the seminars and release of the reports, where we sought to achieve saturation for the points we were making, as determined by triangulation by multiple speakers and outside sources.

Audio-visual recording: The seminars and the in-depth interviews were recorded, and the recordings were safely stored electronically on a shared network drive at The George Institute for Global Health.

Transcripts: A verbatim transcript was created from the recordings and circulated to all participants. Witnesses at this point could exercise their right to delete, restrict, and/or redact portions of an interview as they saw fit. They were requested to complete this within a week and up to 10 days. The transcript was then annotated with biographical and bibliographical information and turned into a report. Annotations took the form of footnotes added in the appropriate places to provide complete references to publications or give brief descriptions of technical terms, events, persons, and organisations. The draft report was then shared with participants for further edits if there were any, and post their approval, it was prepared for publication. Final reports are freely available online and constitute the primary data sources for this analysis.

Analytical approach

Prior to the Witness Seminars, three team members had prepared codes pertaining to each of the guiding questions. These predefined codes helped index the witness verbatim across the three broad themes of emergence, evolution, and evaluation and impact – this was completed with help of the software ATLAS.ti 22. As states earlier, this paper focuses on the theme of ‘emergence’. Two researchers (MK & SS) independently coded the transcripts from the Witness Seminars and the in-depth interviews. Following the completion of coding, MK & SS checked for consistency and resolved discrepancies through iterative discussions. The codes were indexed and the same was discussed with DN who reviewed and resolved discrepancies that had arisen.

The ‘emergence’ theme covered the questions of (a) the role of community action and voice in the genesis of NRHM in 2005, and (b) how ‘communitization’ and community accountability framework were brought into the NRHM, including the key players and institutions. The analysis of the ‘emergence’ of the institutionalisation of community action in health is carried out using the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) developed by John Kingdon, which provides an analytical approach to understand why some policy solutions get a preference over others (Hoefer, Citation2022; Kingdon, Citation1995). According to the framework, a policy solution is adopted when a ‘problem’, ‘politics’ and ‘policy’ streams converge opening a ‘policy window’ (Hoefer, Citation2022; Kingdon, Citation1995). The MSF has been widely used for analysing the agenda-setting process of a policy (Cairney & Zahariadis, Citation2016; Kusi-Ampofo et al., Citation2015; Mauti et al., Citation2019; Mhazo & Maponga, Citation2021) and hence we considered it appropriate to analytically frame how ‘communitization’ ascended on the policy agenda as described by the witnesses. The framework is grounded in the premise that ‘short-term, unstable, high-profile agenda setting is tempered by long-term, continuous processes going on behind the scenes’ (Cairney & Zahariadis, Citation2016, p. 87).

Results

lays out the participant characteristics defined in terms of the roles that the witnesses held during their past and current involvement with the NRHM and broader health systems and policy processes. The witness group for both the seminars (inclusive of the IDIs) had 5 women out of the total 15 participants.

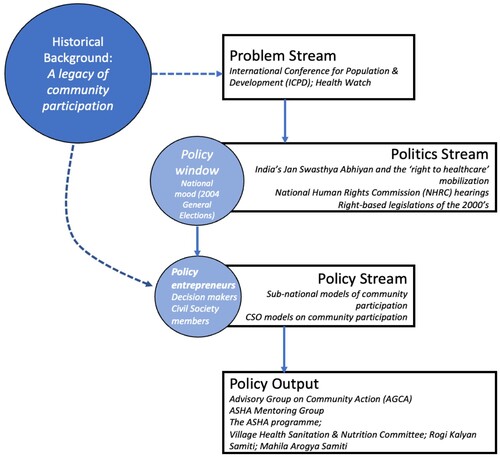

We examined the emergence of the framework for institutionalising community action for health as part of the NRHM by adapting and applying the MSF as illustrated in .

Figure 1. Our adaptation of John Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Analysis Framework. Source: Zahariadis (Citation2007) adapted from Zahariadis N. The Multiple Streams Framework: Structure, Limitations, Prospects. In: Sabatier PA, Theories of the Policy Process, Second Edition. Avalon Publishing; 2007. p. 65–92.

In the context of our analysis, a few of the adaptations to the MSF include addition of a dimension of the historical background of NRHM and ‘communitization’ along with a few more adaptations to how we approach the sequence of the framework and the same have been covered as part of the analysis for each of the components.

Our analysis suggested that while it was less clear what single problem the institutionalisation of ‘communitization’ was addressing in the context of NRHM, critical ‘focusing events’ that created ‘feedback’ and ‘load’ occurred in tandem with the emergence of a ‘policy window’ involving a less-cautious decision style. This was enabled by a policy stream where models of community action at local levels had shown feasibility (standing on a vibrant precedent, and empowered by an active and highly engaged civil society backbone). The impetus set in place by ‘policy entrepreneurs’, finally, led to the emergence of ‘communitization’ at the systemic level. We describe these features in the following sections with the caveat that they do not neatly separate as streams that eventually coalesce, instead representing multiple currents operating in a larger stream related to community action for health in India.

Before proceeding with the analysis, it is crucial for us to highlight the overarching influence that India’s legacy of people’s participation and social movements had on the events leading up to the adoption of ‘communitization’ under the NRHM. One of the witnesses located the roots of this legacy in the context of the ‘freedom struggle’, particularly around 1947, starting with the Bandung Conference of 1937 and the Sokhey Committee of 1938 which spoke of a ‘community health worker program with 1 CHW per 1000 population in India’ (National Planning Committee, Citation1947). Witnesses brought up regional examples of community mobilisation and action which, according to them, influenced the community participation and accountability framework of the NRHM. This included women taking up local health-related issues and mobilising the community to lead and address such issues. To quote a witness:

The first thing I am describing is the […] Dalli Rajhara women’s section of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, where the women there decided to take up the question of alcohol. When they took up the question of alcohol, they took it up in a campaign mode. That was one of the early examples of what later got pulled into the Mitanin [Chhattisgarh's community health worker] program. [Witness 10]

Problem stream

The ‘problem stream’, as per Kingdon refers to how certain policy problems draw the attention of people and as a consequence of government decision-makers (Kingdon, Citation1995). The creation of ‘communitization’ mechanisms in NRHM was not premised, as per our witnesses, on any specific and clearly defined problem but rather based on a series of ‘focusing events’. Kingdon noted that problems may not be self-evident, instead needing a little push to get the attention of people in and around the government – Kingdon conceptualised this ‘push’ to be a ‘focusing event’ (Cairney & Zahariadis, Citation2016; Kingdon, Citation1995). Below are what emerged strongly as focusing events in the wake of NRHM and the institutionalisation of community action for health.

To start with, witnesses spoke about their involvement in initiatives related to community accountability processes in health over decades before the advent of NRHM. These were focused on local problem identification and problem-solving. The 1994 International Conference for Population and Development (ICPD) held in Cairo, Egypt was a watershed moment for state-civil society partnerships in health systems and programmes, with both sets of actors showing a united front advocating for the sexual and reproductive rights of women and girls in a global platform. This coalition was brought home in the form of an initiative called the Health Watch, comprising of civil society members to assist the government in offering rights-based alternatives to implement sexual and reproductive programmes in the country (Visaria et al., Citation1999). Many participants opined that the emergence and institutionalisation of ‘communitization’ could be traced back to the ICPD and Health Watch experience which were grounded in a rights-based framework. Around this time, a global right to health movement was also coalescing around the unkept commitment of the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration to Health For All by 2000. This culminated in the formation of the JSA, the Indian chapter of the People’s Health Movement in 2000. To quote a participant:

I will start with the emergence as I see it. The story for me starts much earlier, actually after Cairo and the Health Watch experience . … On one side, I see myself being influenced by the Health Watch process, and by the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan – People’s Health Assembly process. Both these contributed to the emerging confidence of the civil society to engage with public systems. [Witness 1]

Politics stream

Kingdon conceptualises as part of his framework a ‘national mood’, i.e. political shifts caused by mobilisation of public opinion ‘along certain common lines’ as integral to promoting specific agenda items on the policy table. The politics stream – as articulated by Kingdon – considers the importance of social movements in stirring public opinion to push for a particular policy agenda and have electoral impacts. Elections also have a powerful effect on the agenda (Kingdon, Citation1995) as was witnessed in India when the country was at the cusp of an election in the early 2000s. As aforementioned, focusing events included the creation of the JSA which immediately set about its work of making health a highly political issue.

The newly formed JSA mobilised public opinion across the country in relation to cases of denial of the right to healthcare leading up to public hearings in 2002 convened by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). The JSA brought together a number of Civil Society Organisations (CSO) advocating for community-led processes and mobilised such networks on the NHRC hearings. To quote a witness:

Though there was a lot of experience in the country through NGOs, there was no countervailing power to change the larger health system trajectory. The formation of JSA helped in the formation of a countervailing power to a large extent. It [JSA] brought together all these 21 networks, women’s movements – 6 groups, environmental movements and others. It played an important role in engaging with the political process and policy process. [Witness 12]

So, I think that sometimes I look at it as a constellation of things that came together. As one senior officer put it, ‘the stars are in the right places, so to speak’. A number of different things came together at a given point of time. One of these events, is, I think, the National Health Assembly, which happened in 2000 organised by a large number of civil society organizations which later came to be called the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan. Then in 2002, spinning off from that and related to that were the Right to Food, the Right to Education and the Right to Information campaigns by a number of rights-based movements and then the collapse of ‘India Shining’ in the 2004 General Elections. [Witness 14]

JSA members played a key role in pushing for community action in health and also promulgating Community-based Minitoring and Planning (CBMP) processes for the NRHM – the very idea of ‘communitization’ and its components reflect the efforts of the health movements at advocating for social accountability within NRHM and broader health systems governance (Donegan, Citation2011; Shukla, Citation2005). Witnesses’ accounts underscored that the state responded to JSA’s advocacy and opened up the space for negotiations on the solutions that were to be tabled by civil society.

Policy window

For our analysis, we adapted Kingdon’s conceptualisation of the ‘policy window’ and nested it within the ‘politics stream’ as the content of the policy window seems to heavily overlap with the politics stream. Witnesses made reference to India’s General Elections of 2004 and a change in the government regime from the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) to the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) while recalling the years cascading into the launch of the NRHM. These events, i.e. the Elections, opened up a policy window which enabled the concept of ‘communitization’ to be formalised as part of the NRHM in 2005. A witness indicated that the change in the ruling party at the Centre led to the translation of a policy proposal into a policy change that continues to be an integral part of ‘communitization’, i.e. the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) programme.

Interestingly, as for ASHA, as [witness 12] sort of traced a longer history, the ASHA was already there and proposed by the Sushma Swaraj government. So, there was already a template on file which got pushed when the UPA government came; and it was a person with a bunch of contraceptives, that was the original plan. I remember seeing a presentation on that, and everyone going ballistic about that. However, that continuity is what I want to highlight. In a way, probably communitization’s time was right, there were [the] right people, right energy, post-election scenario, ideas, and even the government wanting to do something. [Witness 13]

Policy entrepreneurs

Witnesses named a few key individuals in the government who were responsive to the advocacy by the civil society and emphasised their role in facilitating civil society participation in the design and implementation of the NRHM’s community-led accountability models. Many of these government decision-makers had experience working with civil society prior to the genesis of the NRHM and were deeply engaged with the series of critical events leading up to the NRHM.

We had to take the help of others – Health Watch, People's Health Movement – and we had to enter into the Prime Minister’s office. The Prime Minister heard our problems. There were powerful bureaucrats at that time who were opposed to this [communitization] idea, who were not very sensitive to this idea, and they wanted to bring only family planning in a very targeted manner into the program of the NRHM and give a very minor role for the community action and ‘communitization’. Luckily, we got it [communitization] into that [NRHM], thanks to the other bureaucrats. [bureaucrat a], [bureaucrat b], [bureaucrat c] – they were very proactive in this, and we also got the hearing of the Prime Minister. This is one of the matters of the genesis that I remember. [Witness 4]

One of the first memories of NRHM is about a meeting we have with [a senior decision maker] in Delhi. [a civil society advocate] led the group as it were and a large group of people had come together, as [Witness 12] had described, essentially to emphasise to the government that the proposed community health worker, the ASHA at that time, was inadequately designed and it needed to be much more a worker with role and responsibility coming from experience of various civil society groups, NGOs, CBOs in India historically. [Witness 13]

Policy stream

According to Kingdon, this is the stage wherein varied policy brokers such as bureaucrats, interest groups, and policy analysts provide inputs for a policy solution to the problem. In the context of our findings and analysis, this stage overlaps with the ‘policy entrepreneurs’ component as the key individuals associated with ‘communitization’ continued to work collaboratively, offering policy solutions to be integrated as part of NRHM. In our analysis, we found that the influence from pre-NRHM and subnational models of community participation coalesced to offer grounding to the NRHM’s ‘communitization’ and the community accountability framework.

Witnesses raised state-specific examples that highlighted models of community participation from the pre-NRHM era; for instance, the Rajasthan Medical Relief Society ‘ … was constituted around various health facilities which then became the placeholder for the Rogi Kalyan Samitis as we went down the line’ [Witness 3]; the Mitanin Programme, i.e. the Community Health Worker programme from Chhattisgarh which existed prior to NRHM informed the ASHA programme at the national level under NRHM. To quote another witness:

Going back to Chhattisgarh, I was looking at some of the old documents of SHRC [State Health Resource Centre]. I noticed in Chhattisgarh the Swasthya Panchayat Yojana was functioning in 2006. At that time, most of the country did not have ASHA karmis. The idea that a Panchayat has to be healthy, and the interface between health and Panchayat was already there in Chhattisgarh. Large number of those were in campaign mode those days, and they developed a small questionnaire which I can see being used even now at Mahila Arogya Samiti, in Chhattisgarh, even at all India level. [Witness 10]

Non-governmental Organisations (NGO) had been developing alternative models of implementing health programmes since the 1990s, and many witnesses recalled their experience of proposing to the government a model design for community-based monitoring of health services under the NRHM. It also appeared from the witness accounts that the NGO members found the space to test their models in collaboration with the government. This space was enabled by the decision-makers who were in officially in charge of designing and implementing NRHM during its formative years.

[we were] this small group of health activists which included [witness 1], [a civil society advocate] and [a civil society advocate] and myself. We interacted and [a decision maker] had set up a task force on district health planning where [a civil society advocate] and I were members and that gave us the opportunity to shape the CBMP framework. [Witness 2]

Negotiations such as this, which placed attention on the governance of ‘communitization’ as much as the processes itself, ensured that accountability reached the highest levels and could truly be conceived and operationalised at scale. As a policy move, this was highly significant and set itself apart from the more ad hoc or de jure efforts and initiatives that had preceded the AGCA and NRHM.

Policy output

Kingdon hasn’t conceptualised ‘policy output’ specifically in his original work but in general refers to ‘outcome’ and ‘choice’ as the function of the merging of the three streams. He refers to the final list of subjects for decision making through a policy enactment as the ‘decision agenda’ (Kingdon, Citation1995). Cairney and Zahariadis (Citation2016) – in their adaptation of the MSF – use ‘policy output’ to imply the policy choice produced from the agenda setting process conceptualised in MSF. The institutionalisation of ‘communitization’ may be considered ‘policy output’ resulting from the intertwining of the components of ‘problem’, ‘politics’, ‘policies’, ‘policy entrepreneurs’ and ‘policy window’ as relevant to our analysis. The witnesses mentioned several structures constituted and institutionalised under the NRHM – or existing structures that were revamped – as part of the ‘communitization’ process, including the Advisory Group on Community Action (AGCA), the ASHA Mentoring Group, the Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC), the ASHA programme, Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS), and Mahila Aarogya Samiti (MAS), among others.

So, NRHM was born in 2005, and along with it came the formulation of several structures and processes slightly antithesis to this informal [unclear] of the community-based healthcare system that had been developed by several in the NGO sector. This was the basis of the NRHM. There was a task force, ASHA mentoring group and Advisory Group of Community Action; the formation of committees – Village Health and Sanitation Committee, the RKSs and so on. What followed was the inevitability of scaling up to national measurements almost in an industrial manner, which [Witness 10] alluded to in his talk. The ASHA and the Village Health and Sanitation Committee and the upward Block – and district-level structures were seen as a phase of communitization. [Witness 11]

Discussion

The principle of Alma-Ata is reflected in NRHM’s tenets recognising that:

If the mission of Health for All is to succeed, the reform process would have to touch every village and every health facility. Clearly it would be is possible only when the community is sufficiently empowered to take leadership in health matters (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Citation2005, p. 29).

This analysis focussed on the data from two Witness Seminars to characterise the emergence of the ‘communitization’ programme. Witnesses did not indicate a specific ‘problem’ that eventually led to the emergence of the ‘communitization’ structures under NRHM but rather a policy impetus created by a series of ‘focusing events’ that includes the ICPD and the Health Watch initiative. The social movement stirred by the JSA and the slew of rights-based reforms introduced during the early 2000s form a crucial part of the ‘politics’ including the ‘policy window’ in the context of our analysis, i.e. the 2004 General Elections nesting within the overall political shifts that pushed for the ‘communitization’ agenda. Boundary spanners in the government and civil society members pushed for ‘communitization’ by mobilising their networks in the highest echelons of the government carving out the space for it to be designed and implemented collaboratively by the government, civil society, and the community. As a result, the participatory structures which emerged (as pointed out by witnesses during the seminars) were the advisory bodies, i.e. the Advisory Group on Community Action (AGCA) and the ASHA Mentoring Group, the ‘communitization’ structures – or existing structures that were revamped – including the Village Health Sanitation & Nutrition Committees, Rogi Kalyan Samitis, and Mahila Arogya Samiti, among others.

The antecedents to the NRHM moment that our Witness Seminars and analysis could examine are limited by time and the feasibility of witnesses sharing their experience of participating in this history. There are additional strands to this nebulous history that attract explorations into how NRHM as a set of programmes moving away from the earlier approach to family planning-based health policies came about. A few pertinent ones include the unsatisfactory results of India’s Reproductive and Child Health Programme-I during the late 90s, the failure of the Structural Adjustment Policies (SAP) of the early 90s in bringing benefits as promised, the rural distress of the 90s up till 2000s, and support of the Left political parties to the United Progressive Alliance as an alternative to the ruling National Democratic Alliance of the early 2000s, among others (Dasgupta & Qadeer, Citation2005; Gaitonde, Citation2020; Srinivasan et al., Citation2007). Along the timeline of the late 1980s preceding the prominence of the ICPD and the Health Watch moment, we also had the Ministry of Rural Development (Government of India) set up the Council for Advancement of People’s Action and Rural Technology (CAPART) as a regulatory interface between the government and the civil society for partnering on initiatives related to rural development (‘Voluntary Action’, Citation2005).

Starting in 2010, UHC has begun occupying greater prominence in India’s policy aspirations, demonstrated through the constitution of the High-level Expert Committee on UHC in 2010. The committee made explicit recommendations for engaging citizens and community participation – followed by the National Health Policy (NHP) of 2017 subsequently shaping the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) programme of 2018 that brought health financing and financial risk protection to the fore (Government of India, Citation2017; Planning Commission of India, Citation2011).

The latest draft of the 2023 political declaration on UHC points towards the centrality of participatory health governance (United Nations, Citation2023). The recent publication of the World Health Organisation on Social Participation in Health titled ‘Voice, agency, empowerment – Handbook on social participation for universal health coverage’ (World Health Organization, Citation2021) consolidates brief case studies from various countries on social participation with an endeavour to advance citizen engagement for UHC. The series of case studies from WHO also includes the study of participatory spaces in India that were created and strengthened as part of ‘communitization’ i.e. the ASHA/Village Health Worker programme, Hospital Management Committees (Rogi Kalyan Samiti), Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees (VHSNC), and community-based monitoring processes, among others (World Health Organization, Citation2021). These structures and community action for health will be important to India’s journey towards UHC as increasing community engagement and participation has been deemed critical for service delivery under the PM-JAY programme (Lahariya et al., Citation2020).

Analysis of how the NRHM and its participatory mechanisms continued to function, alongside advocacy for reform, has been widely published (Dasgupta & Qadeer, Citation2005; Shukla, Citation2005; Soni, Citation2014; Srinivasan et al., Citation2007). Our documentation is an attempt at filling the current vacuum in evidence on institutionalisation of ‘communitization’ models (Lahariya et al., Citation2020) under NRHM and to address nuances related to the historical determinants of the participatory and social accountability mechanisms under NRHM. It is part of an ongoing research-advocacy partnership with the Civil Society Engagement Mechanism for UHC2030 – a global advocacy movement for advancing UHC that is interested in drawing lessons from NRHM’s participatory models and structures, including their features and context-specific drivers and challenges. In addition to technical knowledge, UHC requires political know-how which comes from community engagement (Allotey et al., Citation2019). Evidence and practice reiterating a shared proposition around the importance of citizen engagement in health continue to spur, and our study aims to contribute to this pool of literature by bringing in stories, evidence, and lessons from India in an attempt to support the global advocacy movements towards advancing community participation for UHC. Globally and within the Indian context, future research can help identify mechanisms by which communities may actively contribute towards advancing UHC especially subgroups of community facing marginalisation. Such research needs to be facilitated through partnerships with UHC advocacy movements and civil society with opportunities for cross learning across contexts.

Literature collating evidence on integrating community participation in health discusses diverse and sometimes conflicting frames of reference around what constitutes community participation in health programmes, and, despite efforts, the gaps in achieving positive health outcomes by means of embedding social participation continue (Gaitonde et al., Citation2017; Morgan, Citation2001; Rifkin, Citation1996, Citation2009). Crucial to resolving this gap is being cognisant of the political context in which community participation is situated (Rifkin, Citation2009). Our Witness Seminars and the subsequent analysis presented in this paper bring out the political context of the NRHM’s ‘communitization’ programme. The analysis attempts at articulating how a political context at the national level is filled with key players, ideas, and events culminating into a framework for participation with its rights-based frame of reference to viewing participation.

This study is focused more broadly on how social participation for health was undertaken at the level of a national policy and its functioning at a generalised national level only briefly touching upon state experiences. The need for systematic, and nuanced documentation and analysis of the participatory processes operating as part of NRHM continues (Lahariya et al., Citation2020). Considering the diversities in social and political institutions and how they function across different states in India, and the fact that health is a State List subject in India, it becomes crucial to explore how the ‘communitization’ institutions took shape and have unfolded and evolved at the state level. We have addressed this theme through documentation (using the witness seminar methodology) of the legacy of community participation and the efforts at decentralisation and health reforms undertaken in the state of Kerala as part of the National Rural Health Mission (Jaya et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b, p. Citation2022c).

One major limitation of our study has been that owing to the pandemic restrictions we had to hold the seminars virtually and not in person. This constrained the depth of interaction that witnesses were able to have while sharing their reminiscence about their participation in such a complex history. Many of the threads and narratives left unfinished during the period of interest (the early 2000s through to 2015 or so) were covered with additional in-depth interviews; the point was underscored, repeatedly, that the national discourse around ‘communitization’ was one, but there were also state-specific discourses and experiences institutionalising NRHM structures. Some of these have been studied, but others warrant further research, and analysis of their relationship to the national context.

Conclusion

The emergence, operationalisation, and functioning of participatory process in the context of NRHM have been a political process deeply embedded in the socio-political history of India. It was evident from the analysis of the emergence of NRHM’s ‘communitization’ models that leadership from the civil society in policy design and implementation, democracy, and space for diverse political mobilisations and state-civil society partnerships are linked to positive results. Alongside the learnings in terms of lessons and challenges of ‘communitization’ that emerged from the witness accounts, witnesses spoke about the way forward towards sustaining and strengthening the current participatory spaces functioning under the NRHM. This includes reducing financial constraints that ‘communitization’ mechanisms are reeling under, capacity strengthening of participatory institutions and active engagement of actors involved in NRHM’s ‘communitization’ institutions – these reflections from the witnesses offer opportunities for strengthening policy response towards strengthening the participatory institutions under the NRHM. Governments must invest in adequate financing to sustain effective administration of participatory mechanisms, strengthen capacity of actors, and compensate participants (Koonin et al., Citation2023; World Health Organization, Citation2021). Legal frameworks mandating such financing could be one approach towards this (Koonin et al., Citation2023). More discussions regarding how the ‘communitization’ structures continue to function, and challenges and impacts related to these mechanisms, are analysed in a different paper.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this research [project no. 27/2020] was obtained from the Ethics Committee of The George Institute for Global Health, India.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Shweta Marathe, Indira Chakravarthi, Rakhal Gaitonde and Rajani Ved for their guidance at the early stages of this project. Ms. Rajani Tatineni provided support for the organisation of the Witness Seminar as well as preparatory meetings. Mr Jason Dass and Mr Alexander Baldock helped with graphics and design for our witness seminar reports. We are also grateful to the team at Auxohub, led by Yashasvini and Vandana, for their careful work on the transcriptions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The NRHM Framework for Implementation (2005–2012) makes mention of the word ‘communitization’ twice but never defines it. The first mention is in a section entitled ‘institutionalizing community led action for health’ where the sentence talks about ‘vibrant community organisations and women’s groups’ being involved with communization. The second instance is in a section entitled ‘monitoring/accountability framework’ where the focus is on ‘communitization’ of health institutions with a specific monitoring role (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Citation2005). ‘Communitization’ hasn’t been defined specifically anywhere in the context of NRHM but has been understood as the institutionalisation and scaling up of community led action for health and includes NRHM’s strategy to include village level community health workers i.e., the ASHA programme, flexible funds at the community led action community level, village level committees and healthcare institution level committees to facilitate accountability, as well as community-based monitoring initiatives. Source: Gaitonde R, San Sebastian M, Muraleedharan VR et al. Community Action for Health in India’s National Rural Health Mission: One policy, many paths. Social Science & Medicine 2017;188:82–90; Communitization. Society for Community Health Awareness Research and Action n.d. Available from: https://www.sochara.org/perspectives/Communitization

2 The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) was subsumed into the National Health Mission (NHM) in 2013. We use 'NRHM’ throughout the paper as our focus is on the emergence of the program which lies in NRHM and we explore the years preceding NRHM i.e., its antecedents.

3 Most if not many participants had multiple, overlapping roles

References

- Allotey, P., Tan, D. T., Kirby, T., & Tan, L. H. (2019). Community engagement in support of moving toward universal health coverage. Health Systems & Reform, 5(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2018.1541497

- Asian Development Bank. (2009). Overview of civil society organizations: India (Civil Society Briefs). https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28966/csb-ind.pdf.

- Berridge, V., & Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine (2006). Public health in the 1980s and 1990s: Decline and rise? The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 12 October 2004 ; [Wellcome Witnesses to twentieth century medicine, Volume 26].

- Cairney, P., & Zahariadis, N. (2016). Multiple streams approach: A flexible metaphor presents an opportunity to operationalize agenda setting processes. In N. Zahariadis (Ed.), Handbook of public policy agenda setting (pp. 87–105). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715922.00014.

- Chakravarti, I., & Hunter, B. (2019a). Witness Seminar on Private Healthcare Sector in Pune and Mumbai since the 1980s. SATHI-CEHAT/Kings College.https://sathicehat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Witness-Seminar-Private-HC-Sector-1.pdf

- Chakravarti, I., & Hunter, B. (2019b). Regulation of formal private healthcare providers in Maharashtra Journey of Bombay Nursing Homes Registration Act and the Clinical Establishments Act and Journey of Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostics Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 1994. SATHI-CEHAT/Kings College. https://sathicehat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Witness-Seminar-Journey-of-BNHRA_PCPNDT-1.pdf.

- Chambers, R. (2013). Ideas for development. Routledge.

- Christie, D. A., & Tansey, E. M. (2001). Maternal care: a witness seminar held at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL.

- Cornwall, A., & Gaventa, J. (2001). Bridging the gap: Citizenship, participation and accountability. PLA Notes, 32–35.

- Dasgupta, R., & Qadeer, I. (2005). The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM): A critical overview. Indian Journal of Public Health, 49(3), 138–140.

- De Vos, P., De Ceukelaire, W., Malaise, G., Pérez, D., Lefèvre, P., & Van der Stuyft, P. (2009). Health through people’s empowerment: A rights-based approach to participation. Health & Hum. Rts., 11, 23.

- Donegan, B. (2011). Spaces for negotiation and mass action within the national rural health mission: “community monitoring plus” and people’s organizations in tribal areas of maharashtra, India. Pacific Affairs, 84(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.5509/201184147

- Duggal, R. (1998). Health care and New economic policies, the further consolidation of the private sector in India. National seminar on the rights to development, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India.

- Duggal, R. (n.d.). Health Planning In India. https://www.academia.edu/21084250/HEALTH_PLANNING_IN_INDIA.

- Gaitonde, R. (2020). Divergences, dissonances and disconnects Implementation of Community-Based Accountability in India’s National Rural Health Mission [Umea University]. http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid = diva2%3A1390255&dswid = 5739.

- Gaitonde, R., San Sebastian, M., Muraleedharan, V. R., & Hurtig, A.-K. (2017). Community action for health in India’s national rural health mission: One policy, many paths. Social Science & Medicine, 188, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.043

- Gaventa, J. (2002). Exploring citizenship, participation and accountability. IDS Bulletin, 33(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2002.tb00020.x

- Government of India. (2017). National health policy, 2017 approved by cabinet focus on preventive and promotive health care and universal access to good quality health care services. Press Information Bureau.. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/Printrelease.aspx?relid = 159376.

- Haldane, V., Chuah, F. L. H., Srivastava, A., Singh, S. R., Koh, G. C. H., Seng, C. K., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2019). Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS One, 14(5), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216112.

- Hassell, T. A., Hutton, M. T., & Barnett, D. B. (2020). Civil society promoting government accountability for health equity in the Caribbean: The healthy Caribbean coalition. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública Pública, 44, 1. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.79

- Hoefer, R. (2022). The multiple streams framework: Understanding and applying the problems, policies, and politics approach. Journal of Policy Practice and Research, 3(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42972-022-00049-2

- Hunt, P., & Backman, G. (2008). Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Health and Human Rights, 10(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/20460089

- Jaya, S., Benny, G., Hari, S., Madhavan, M., Kakoti, M., Srivastava, S., Shraddha, M., & Nambiar, D. (2022a). The case of decentralization and health reforms in Kerala: First of three witness seminars (Witness Seminar on Community Action for Health in India). https://cdn.georgeinstitute.org/sites/default/files/documents/CommAction4Health_WitnessSeminar1_%20Kerala_Sep_2022.pdf.

- Jaya, S., Benny, G., Hari, S., Madhavan, M., Kakoti, M., Srivastava, S., Shraddha, M., & Nambiar, D. (2022b). The case of decentralization and health reforms in Kerala: Second of three witness seminars (Witness Seminar on Community Action for Health in India). https://cdn.georgeinstitute.org/sites/default/files/documents/CommAction4Health_WitnessSeminar1_%20Kerala_Sep_2022.pdf.

- Jaya, S., Benny, G., Hari, S., Madhavan, M., Kakoti, M., Srivastava, S., Shraddha, M., & Nambiar, D. (2022c). The case of decentralization and health reforms in Kerala: Third of three witness seminars (Witness Seminar on Community Action for Health in India). https://cdn.georgeinstitute.org/sites/default/files/documents/CommAction4Health_WitnessSeminar1_%20Kerala_Sep_2022.pdf.

- Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. HarperCollins College.

- Kocher, J. E. (1980). Population policy in India: Recent developments and current prospects. Population and Development Review, 6(2), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/1972732

- Koonin, J., Mishra, S., Saini, A., Kakoti, M., Feeny, E., & Nambiar, D. (2023). Are we listening? Acting on commitments to social participation for universal health coverage. The Lancet, 402, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01969-4.

- Kusi-Ampofo, O., Church, J., Conteh, C., & Heinmiller, B. T. (2015). Resistance and change: A multiple streams approach to understanding health policy making in Ghana. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 40(1), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2854711

- Lahariya, C. (2018). ‘Ayushman bharat’ program and universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatrics, 55(6), 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-018-1341-1

- Lahariya, C., Roy, B., Shukla, A., Chatterjee, M., Graeve, H. D., Jhalani, M., & Bekedam, H. (2020). Community action for health in India: Evolution, lessons learnt and ways forward to achieve universal health coverage. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 9(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.4103/2224-3151.283002

- Mauti, J., Gautier, L., De Neve, J.-W., Beiersmann, C., Tosun, J., & Jahn, A. (2019). Kenya’s health in All policies strategy: A policy analysis using Kingdon’s multiple streams. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0416-3

- Mhazo, A. T., & Maponga, C. C. (2021). Agenda setting for essential medicines policy in sub-saharan Africa: A retrospective policy analysis using Kingdon’s multiple streams model. Health Research Policy and Systems, 19(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00724-y

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2005). National Rural Health Mission Meeting people’s health needs in rural areas Framework for Implementation 2005-2012. MoHFW. https://nhm.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/nrhm-framework-latest.pdf.

- Morgan, L. M. (2001). Community participation in health: Perpetual allure, persistent challenge. Health Policy and Planning, 16(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/16.3.221

- National planning committee. (1947). National health. Vora. https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/national-planning-committee-series-report-of-the-sub-committee-national-health/.

- Odugleh-Kolev, A., & Parrish-Sprowl, J. (2018). Universal health coverage and community engagement. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96(9), 660–661. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.202382

- Perry, H. B., & Rohde, J. (2019). The jamkhed comprehensive rural health project and the Alma-Ata vision of primary health care. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5), 699–704. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304968

- Planning Commission of India. (2011). High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/publication/Planning_Commission/rep_uhc0812.pdf.

- Rifkin, S. B. (1996). Paradigms lost: Toward a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta Tropica, 61(2), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-706X(95)00105-N

- Rifkin, S. B. (2009). Lessons from community participation in health programmes: A review of the post Alma-Ata experience. International Health, 1(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.001

- Rifkin, S. B. (2014). Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: A review of the literature. Health Policy and Planning, 29(Suppl 2), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu076

- Shukla, A. (2005). National rural health mission–hope or disappointment. Indian Journal of Public Health, 49(3), 127–132.

- Soni, P. (2014). Changing facets of public health services in India institutionalising rogi kalyan samiti madhya pradesh. In Mortality and Health, 173–179.

- Srinivasan, K., Shekhar, C., & Arokiasamy, P. (2007). Reviewing reproductive and child health programmes in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 42, 2931–2939. https://www.epw.in/journal/2007/27-28/special-articles/reviewing-reproductive-and-child-health-programmes-india.html.

- Srivastava, A., Gope, R., Nair, N., Rath, S., Rath, S., Sinha, R., Sahoo, P., Biswal, P. M., Singh, V., Nath, V., Sachdev, H., Skordis-Worrall, J., Haghparast-Bidgoli, H., Costello, A., Prost, A., & Bhattacharyya, S. (2015). Are village health sanitation and nutrition committees fulfilling their roles for decentralised health planning and action? A mixed methods study from rural eastern India. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2699-4

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- United Nations. (2023). Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage: Zero draft. https://www.un.org/pga/77/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2023/05/UHC-Political-Declaration-2023-Zero-Draft-FINAL.pdf.

- United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good health and wellbeing. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/.

- Ved, R., Scott, K., Gupta, G., Ummer, O., Singh, S., Srivastava, A., & George, A. S. (2019). How are gender inequalities facing India’s one million ASHAs being addressed? Policy origins and adaptations for the world’s largest all-female community health worker programme. Human Resources for Health, 17(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0338-0.

- Visaria, L., Jejeebhoy, S., & Merrick, T. (1999). From family planning to reproductive health: Challenges facing India. International Family Planning Perspectives, 25, S44–S49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991871

- Voluntary Action: CAPART Blues. (2005). Economic and Political Weekly. https://www.epw.in/journal/2005/13/editorials/voluntary-action-capart-blues.html.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Voice, agency, empowerment – handbook on social participation for universal health coverage. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/342704.

- Zahariadis, N. (2007). The multiple streams framework: Structure, limitations, prospects. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process, second edition (pp. 65–92). Avalon.