ABSTRACT

This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the current landscape of pediatric palliative care in Latin America, including policies, regulations, available resources, challenges, barriers, and evidence-based recommendations. We conducted a comprehensive search for peer-reviewed articles related to pediatric palliative care in Latin America, considering both review and empirical articles published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish within the last decade. Our review initially identified 30 publications, which were subjected to a full-text assessment. The majority of these articles originated from Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, highlighting a regional concentration of research efforts. Notably, we observed a scarcity of comprehensive research and specific studies on pediatric palliative care in Latin America. Our findings revealed significant challenges, including resource limitations, the absence of dedicated policies, and the critical need for interdisciplinary teams to address the multifaceted aspects of pediatric palliative care. In light of our review, we emphasise the necessity for more extensive and representative research efforts, as well as the continuous updating of scientific evidence in the field of pediatric palliative care within the Latin American context. The recommendations derived from this review aim to contribute to the enhancement of pediatric palliative care services and accessibility throughout Latin America.

Introduction

Over recent decades, Palliative Care (PC) has garnered significant attention (González et al., Citation2012), driven by the rising burden of non-communicable chronic diseases (Parodi et al., Citation2016). Its focus is on alleviating suffering and enhancing the quality of life for patients with severe or terminal illnesses and their families (Alonso, Citation2013). As defined by the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), PC emphasizes the prevention and relief of suffering through early detection, accurate assessment, and the treatment of pain, along with other potential physical, psychological, or spiritual issues (PAHO, Citation2016). While there have been substantial advancements in PC research and implementation globally, Latin America (LA) still faces significant hurdles. PC often remains a secondary consideration, with limited accessibility for the general populace and insufficient investment in resources and training for healthcare professionals (Víctor, Citation2019). Moreover, when there's an emphasis on PC, it is frequently exclusive to adult services (Garcia-Quintero et al., Citation2020).

Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) is dedicated to managing the pain and distress experienced by children and adolescents with chronic or terminal illnesses and their families (Norris et al., Citation2019). Globally, it is estimated that four million individuals require PPC. Access remains uneven across regions; pediatric palliative services are deemed underdeveloped in Asian, African, and South American continents compared to Europe and North America (Connor & Sepulveda-Bermedo, Citation2014). The lack of PPC access gravely impacts children and their families, leading to exacerbated pain, suffering, and a reduced quality of life (Gaab, Citation2015). This underscores the urgency to champion the development and deployment of PPC policies and programmes on a global scale.

In LA, the prevalence of chronic and terminal diseases among children is notable (Constantinou et al., Citation2019). The region grapples with intricate challenges in delivering PPC. Furthermore, PPC needs to cater to a diverse range of over 300 complex and limiting pediatric diseases (Friedel et al., Citation2019). As such, programmes must be adaptable and flexible to meet the varied needs of pediatric patients (Wolff et al., Citation2020) and their families (Leemann et al., Citation2020). Yet, the region is marked by fragmented and unequal healthcare systems, often restricting or even denying access to PPC. The prevailing structural inequality and current policies further exacerbate these issues (Simão & Mioto, Citation2016). In the present healthcare landscape of LA, there's a growing acknowledgment of PPC's pivotal role in alleviating suffering and elevating the quality of life. Despite advancements in PPC research and implementation worldwide, the scenario in LA has unique intricacies and challenges. Existing literature highlights that effective PPC programmes emphasize pain and suffering relief, enhanced communication among healthcare providers, patients, and their families, and emotional and psychological support (Pastrana et al., Citation2012, Citation2013). With the establishment of care standards incorporating PPC quality indicators, it's crucial to map the development level of these services across the continent (Zuniga-Villanueva et al., Citation2021).

Given these circumstances, there's a pressing need to assess the maturity of these services, pinpoint the specific challenges hampering effective implementation, and highlight the fundamental barriers affecting care for children and families requiring palliative care in LA. Therefore, this study aims to address these issues through a scoping review and a critical analysis of PPC in the region. The objective is to offer an overview of the current PPC landscape in LA and an in-depth analysis of related policies and regulations (Zuniga-Villanueva et al., Citation2021). This review intends to bolster future policies, strategies, and actions, ensuring dignified, high-quality care for children and families in need of PC in LA.

Materials and methods

Given the breadth and diversity of aspects related to PPC in Latin America, an exploratory review approach is employed to comprehensively map and understand these elements. The questions and objectives of this review are broad in scope and multidimensional, encompassing policies and regulations, as well as challenges and barriers in the delivery of PPC. An exploratory review approach, such as the Scoping Review, is particularly suited for this purpose. The scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA ScR) guidelines and was grounded in the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005). It is registered (blinded for peer review) following the principles of Open Science.

Research question

The guiding research question was: What is the current state of PPC in Latin American countries in terms of policies, regulations, available resources, challenges, barriers, and evidence-based recommendations? Accordingly, the objectives are to (1) Assess the development level of PPC in Latin American countries by mapping out policies, regulations, and available resources; (2) Identify specific challenges hindering the effective implementation of PPC in the region; (3) Describe the key barriers impacting care for children and families requiring palliative care in Latin America; and (4) Offer recommendations to address challenges and overcome barriers in the provision of PPC in the region.

Identification and selection of relevant studies

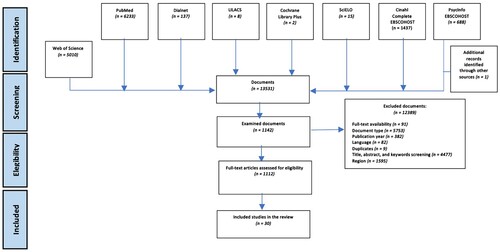

A document search was conducted across nine databases (PubMed, SciELO, Dialnet, Lilacs, Cochrane Library Plus, CINAHL Complete EBSCOHOST, PsycINFO EBSCOHOST, and Web of Science). The search equation included ‘paediatric palliative care’ OR ‘pediatric palliative care’ AND ‘Latinamerica OR Latin America OR South America’ in the title, abstract, and keywords (see ). The resulting documents from the search were reviewed for inclusion by one of the researchers through an initial title and abstract reading, and subsequently confirmed by a second researcher. Publications that did not meet the aforementioned inclusion criteria were excluded; no exclusions were made on any other grounds. The criteria followed to evaluate the documents include:

Article Type: Both review and empirical articles were included to ensure broad coverage of scientific literature related to Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) in Latin America. Review articles will provide a summary of existing evidence, whereas empirical articles will deliver more specific data on the challenges and implementation of PPC in the region.

Publication Year: The decision to restrict the search to publications from the past 10 years is based on the need for up-to-date information regarding PPC's status in Latin America. As healthcare and health policies can significantly evolve over time, the focus is on documents that represent the most recent situation of PPC in the region. This approach aims to obtain a clearer understanding of current policies, regulations, resources, challenges, and evidence-based recommendations. By zeroing in on recent publications, outdated or no-longer-in-use programmes or policies, which might not be relevant to this scoping review's objective, are avoided.

Language: Publications in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were included to encompass as many relevant documents on PPC in Latin America as possible. These languages, prevalent in the region, will enable a more comprehensive review of available literature.

Topic: Selected documents should revolve around Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) in Latin America to ensure their relevance to this review's purpose. Documents not focusing on PPC or delving into other non-related pediatric medical care topics in the region are excluded.

Peer Review: Only peer-reviewed documents were included to ensure a minimum quality and reliability standard in the reviewed literature. Peer review is an assessment process of scientific document quality and validity, enhancing the trust in the articles’ provided information.

Table 1. Sources of information, search equation, and number of resulting articles.

It was assumed that key terms used in the search strategy, such as ‘Pediatric Palliative Care’ and ‘Latin America’, would aptly identify publications relevant for the scoping review. Publications from the last 10 years (from 2013 to 2023) were deemed to adequately represent the current situation of PPC in Latin America, excluding outdated or no-longer-in-use information. The data acquisition and confirmation process was streamlined, involving original researchers from the documents or additional sources when necessary to clarify ambiguous or insufficient information.

Duplicates were manually detected and removed (n = 9). Ultimately, 30 publications were included for full-text review (). In parallel with the documentary search, a legislative search and in-country resource search were also conducted.

Data extraction

Specific data mapping forms were designed according to the variables of interest (policies and regulations, resources, challenges and barriers, and recommendations). Data extraction was carried out independently by the researchers, using these forms. A cross-check was then performed to ensure accuracy and consistency, resolving any discrepancies by consensus. Once data extraction was completed, the information was organised and summarised. The data were grouped according to the thematic categories defined in the research question. Data were presented in tables and graphics to facilitate visualisation and understanding. It was assumed that the reviewed documents would provide substantial and relevant information on each of the variables of interest. Effort was made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the extracted data, but it is acknowledged that the availability and quality of information might vary among evidence sources.

Data mapping forms were designed prior to the start of the information extraction process. These were calibrated and tested on a pilot set of documents to ensure their suitability. Data extraction was performed independently by researchers, using these forms to record structured information systematically. The variables of interest during the information synthesis were as follows, and the data extraction matrices can be found in Appendix S1:

Policies and Regulations: Refers to governmental policies and regulations established in Latin American countries related to PPC in the region. This includes rules, laws, guidelines, and any normative framework governing the provision of PPC in the area.

Available Resources: Encompasses the physical, human, and financial resources allocated for PPC care in Latin America. This covers the availability of medical facilities, trained health personnel, equipment, and specific funding for PPC.

Challenges and Barriers: Refers to obstacles and issues identified in the reviewed literature or documents that hinder the effective implementation of PPC in the region. This may include financial, cultural, logistical, or other barriers. Barriers are factors that prevent or limit access to PPC in Latin America, including geographical, economic, sociocultural, and any other factors that hinder the care of children and their families.

Evidence-Based Recommendations: Refers to suggestions, guidelines, or recommendations identified in the reviewed literature that are based on scientific evidence and aim to improve the provision of PPC in Latin America.

Results

To determine the level of development of PPC in Latin America, current policies and regulations in the region were identified (). Out of the 30 identified documents, there were 8 review articles (26.67%) and 22 empirical articles (73.33%). Among the empirical articles, 13 (43.33%) used qualitative approaches, 8 (26.67%) employed quantitative methods, and 1 (3.33%) used a mixed-method approach. Moreover, 66.66% of the identified documents were published in English, while the remaining 33.33% were in Spanish. The majority of the documents focus on Brazil (8; 26.67%), followed by Mexico and Chile, each with 3 documents (10%). Colombia and Argentina have 2 documents each (6.67%), while Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Ecuador each have 1 document (3.33%). Additionally, 8 documents (26.67%) span multiple countries in their data collection. Details are available in Appendix S1.

Table 2. Data extraction matrix for regulations, legislation, and resources.

Resources for development refer to the means and tools available to foster and promote the advancement of palliative care (PC) and pain management. These resources can include funding, institutional support, training of health professionals, establishment of specialised centres, creation of educational programmes, among others. The goal of these resources is to enhance the quality of PC and pain management care, as well as to promote its implementation and dissemination in clinical practice. On the other hand, resources for research refer to the means and facilities aimed at conducting research in the field of PC and pain management. This implies providing research funds, establishing research infrastructures, promoting collaboration among researchers, and providing access to necessary data and resources to conduct relevant research. These resources are essential to drive knowledge generation, improve clinical practices, develop new therapies and approaches, and provide scientific evidence that supports and enhances care in PC and pain management. Some countries mention specific resources for PC development, although the availability of research resources varies more broadly.

Summary and presentation of the results

To assess the level of development of palliative care programmes (CPP) in Latin America, it is vital to complement the analysis of current policies and regulations with specific reports on professional practices in the field. There are policies and regulations related to CPP in some countries of the region. However, not all countries have specific regulatory frameworks for CPP, leading to disparities in service provision and patient care. 57.89% of the countries from which data is available have General or National Health Laws that include provisions on PC and pain management (47.36%); however, the presence of specific laws on CPP drops significantly, being considered only in 5 cases (26.31%). Following the objectives of the review, the main results are summarised in .

Table 3. Review results by objectives.

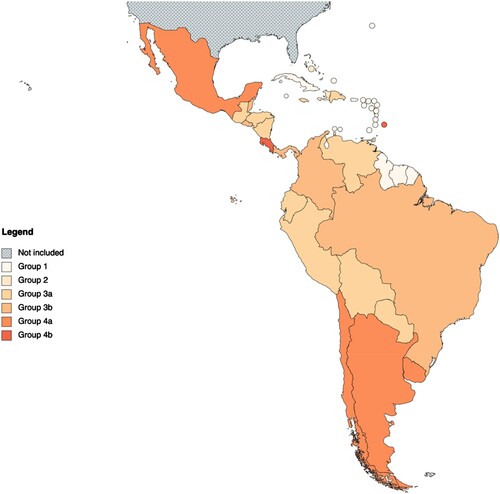

In 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Worldwide Hospice and Palliative Care Alliance (WHPCA) published the Global Atlas of PC (Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance & World Health Organization, Citation2020), in which they categorise the service development in each country into four possible levels: (1) No known PC activity; (2) Capacity building activity; (3a) Isolated provision of PC; (3b) Widespread provision of PC; (4a) Early-stage integration of PC into general service provision; (4b) Advanced-stage integration of PC into general service provision (see ).

L1: 9 countries (27.27%)

L2: 2 (6.06%)

L3a: 11 (33.33%)

L3b: 5 (15.15%)

L4a: 4 (12.12%)

L4b: 2 (6.06%)

Figure 2. Development of PC in Latin America according to the classification by WHO and WHPCA. Source: adapted from the classification proposed by WHPCA and WHO (Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance & World Health Organization, Citation2020).

In Latin America, PCPs face various challenges and barriers that have hindered their development and equitable access compared to other regions in the world. One fundamental aspect for the advancement of these programmes is the definition of quality indicators, but a consensus has yet to be reached regarding the outcomes and criteria that should be considered. An essential challenge is the lack of preparedness among the healthcare team. Low CP knowledge among healthcare personnel highlights the need for measures to train and inform them about the importance of initiating PC early in the diagnosis of incurable diseases. The scarcity of financial and human resources, inadequate training and education in PC for healthcare professionals, and limited availability of essential medications for pain control and other symptoms are obstacles that hinder the provision of proper care. Lack of awareness and institutional support are also considered significant barriers to the development of PCPs in Latin America.

An ethical analysis conducted at the National Children's Hospital in Costa Rica revealed that ethical issues generate doubts and uncertainty among PCPs’ team members (Rodríguez, Citation2003). The absence of care protocols for specific treatment cases or certain pathologies also creates insecurity in decision-making and care provision. In Chile, a lack of in-depth research on the application of PCPs and the specific role of Occupational Therapy in this context is evident (Bermúdes et al., Citation2016). The absence of care protocols for specific treatment cases or certain pathologies can lead to uncertainty among some team members when providing care and making decisions. To improve the situation, interventions promoting access to PC resources, didactic training, and clinical education, with a focus on equitable access to essential resources and support, are necessary. Additionally, there is a need to strengthen the identification and proper integration of potential beneficiaries of PCPs, which are critical aspects to enhance the timeliness and quality of service in the region.

Furthermore, effective PC implementation and continuous education in clinical practice ethics are emphasised (Rodríguez, Citation2003). Educational interventions are needed to improve the quality of life of children in the terminal stage and the importance of more extensive training and education for healthcare professionals (Mota et al., Citation2017). This underscores the importance of including PC in the academic training of professionals and providing a supportive environment within healthcare institutions (Verri et al., Citation2019). It is also essential to enhance communication and coordination of care and provide emotional support to children and their families (Flexa et al., Citation2018). According to these authors, areas for improving PC plans include expanding care plans, research on administration and management, communication during hospitalisation, and the complexity of the hospital and home care network as relevant topics for the advancement of nursing in future studies. Additionally, the importance of establishing public and private policies that promote PC and efficiently allocate available healthcare resources is highlighted (Lo et al., Citation2022). Finally, there is a recognised need to improve coping strategies and address empathy fatigue among PC programme professionals (Scaratti et al., Citation2019).

The analysed documents highlight the significance of multidisciplinary teams for PPC, providing comprehensive and high-quality care to children and their families (Ferreira et al., Citation2015; Rendón et al., Citation2011; Scaratti et al., Citation2019). These teams consist of professionals from various disciplines such as medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, education, chaplaincy, and others, who collaborate to address the physical, emotional, social, educational, and spiritual needs of patients and their families. Overall, it is recognised that multidisciplinary teams play a crucial role in delivering quality PPC and in enhancing the experience of patients and their families.

Discussion

The present scoping review reveals significant challenges in the development of PPC in Latin America (LA). Regarding policies and regulations, most countries have General or National Health Laws that include provisions on PPC and pain control. However, the presence of specific PPC laws is notably low, limited to only five cases, posing an obstacle to ensuring adequate care and equitable access to PPC in the region.

Regarding current policies and regulations, most countries have General or National Health Laws that include provisions on PPC and pain control. Still, the presence of specific PPC laws is considerably low, limited to only five cases, which can be an obstacle to ensuring appropriate care and equitable access to PPC in the region (Parodi et al., Citation2016). In terms of resources for development, the importance of having financing, institutional support, training of health professionals, establishment of specialised centres, and educational programmes is highlighted (Víctor, Citation2019). The classification of the development of the PPC service in LA countries, according to the Global Atlas of PC (Pastrana et al., Citation2021), reveals that most countries are at levels ranging from 1 to 3. These levels indicate there's capacity development activity and isolated or widespread provision of PPC in some countries, but there's still a way to go to achieve full integration into general service provision.

There are significant challenges to overcome in LA concerning the development of PPC (Alonso, Citation2013). The lack of consensus regarding the quality indicators of PPC makes it difficult to evaluate and compare services in the region, which aligns with Víctor's (Citation2019) statement on the lack of investment in resources and training for health professionals. PPC often focuses on adult services, as indicated by Parodi et al. (Citation2016) and Garcia-Quintero et al. (Citation2020). The lack of preparation of the health team in PPC and the shortage of financial and human resources identified (Aldana et al., Citation2022; Downing et al., Citation2018) also support the statement on the lack of training and resources in the region. The lack of awareness and institutional support is also highlighted as significant obstacles for the development of PPC in the region.

The lack of care protocols in specific cases and the lack of in-depth research in specific areas, such as Occupational Therapy, coincide with the identified limitations. In practical terms, the results emphasise the need to establish clear protocols and promote educational and training interventions to improve the quality of life for terminally ill children and provide adequate care. Moreover, improving communication and care coordination becomes paramount, as does ensuring equitable access to the basic resources needed for PPC. Concerning public and private policies, the need to establish regulatory frameworks that promote PPC and efficiently allocate available health resources is reiterated. Collaboration between the public sector, civil society organisations, and the private sector is vital to ensure equitable and quality care for all children requiring PC.

The results highlight the empathetic burnout experienced by professionals working in PPC programmes, underscoring the need to address this critical aspect. Providing support and resources to care for the well-being of professionals is essential to ensure sustainable and quality care for patients and their families. In short, the findings of this study support and expand on the theoretical framework's claims regarding the challenges and barriers in the development of PPC in Latin America (LA). The importance of adopting a comprehensive and collaborative approach to overcome existing challenges and provide dignified and quality care to children with serious and terminal illnesses, as well as their families, is emphasised. It is crucial to have robust policies that support PPC, efficiently allocating the necessary resources. Continuous training for health professionals in the field of PPC should also be ensured, incorporating this care into academic programmes and promoting research in the area. The evidence obtained in this study provides a solid foundation to advocate for improvements in the LA PPC system. The findings also emphasise the need for concrete actions, such as policy development and implementation, adequate resource allocation, and research promotion. Only through a comprehensive and collaborative approach can current challenges be overcome and quality care ensured for children requiring palliative care in the region.

Research on the application of PPC is limited, and the absence of care protocols for specific cases or certain pathologies creates uncertainty for the health team when providing care and making decisions. It's essential to effectively implement PPC and provide continuous education in clinical ethics. The need for more training and education for health professionals is highlighted.

The findings reveal a concerning reality in the region, where care for children in palliative situations faces numerous challenges. This situation raises fundamental questions about equity and justice in access to medical care. Is it ethical that some children receive high-quality palliative care while others, due to a lack of specific policies and limited resources, cannot access the same quality of care?

The fact that most countries have General Health Laws that include provisions on PPC, but that the presence of specific laws is low, invites reflection on the role of health policies in promoting equitable medical care. Are general policies sufficient to ensure that children in palliative situations receive adequate care, or is a more specific and detailed approach needed in legislation?

The lack of financial and human resources, as well as the lack of consensus on quality indicators, raises questions about society's and governments’ commitment to caring for children with life-limiting illnesses. How much do we value as a society the care of these children and their families? What are we willing to invest in terms of resources and training to ensure quality care? The temporal bias in the review, due to the inclusion of older studies, underscores the need to keep scientific evidence in the field of PPC updated. This leads us to question how research in this area is valued and funded. Are we allocating enough resources to generate evidence that supports the continuous improvement of PPC?

Ultimately, these results raise fundamental ethical and philosophical questions about medical care, equal access, and the role of society and governments in caring for the most vulnerable. They urge us to reflect on our values as a society and consider the importance of ensuring that all children, regardless of their geographical or economic situation, have access to high-quality palliative care.

Despite the richness of the study's findings, some limitations are acknowledged. Firstly, regarding the search process and scope of the review, it is important to note that although exhaustive efforts were made to gather relevant information from various sources, the information presented in may not be exhaustive, and it's possible that some relevant aspects in each country are not mentioned. This is due to the limited availability and accessibility of specific data in some LA countries, which may have affected the complete representativeness of details on policies, regulations, and resources related to PPC. Secondly, regarding the availability of studies and scientific literature, there is a predominant concentration of research in Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, while other countries in the region have much lower representation in the literature. This lack of in-depth research and specific studies in some countries makes it difficult to identify best practices and generate the necessary scientific evidence to support and improve care in PPC in the region. Therefore, it's important to recognise that the review might more significantly reflect the situation in countries with a stronger presence in scientific literature. Lastly, it is relevant to note that one of the articles included in this scope review does not meet the inclusion requirement of being within the last 10 years. However, it was deemed relevant and included due to its significance in the research context, providing valuable information on PPC in the region, despite its age. This may have introduced a temporal bias in the review, but it was done with the intent of more comprehensively and accurately addressing the topic of interest.

These limitations underscore the need for future, more exhaustive and representative research in the Latin American region, as well as the importance of keeping scientific evidence in the field of PPC updated. Including more countries and a broader diversity of studies in future research would allow for a more complete and equitable understanding of the PPC situation in the region.

In conclusion, there is an urgent need to develop PPC policies and programmes in LA to ensure equitable access and quality care. It is hoped that this review will help identify gaps in PPC research and improve the quality of care through a collaborative and holistic approach.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the authors of the included studies. We would also like to acknowledge the Spanish National Research Agency AEI and the European Social Fund Plus.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldana, L. E., Alvarado, E. F., Córdoba, W. G., Hernández, D. T., Marulanda, A. D., Osorio, J. P., Pérez , D. F., Solarte , J. J., & Sora, C. J. (2022). Percepción de los niños y cuidadores sobre los procesos educativos y apoyo psicoemocional de un programa de cuidado paliativo pediátrico entre los años 2021-2022 [internet]. https://acortar.link/1mOLbl

- Alonso, J. P. (2013). Cuidados paliativos: entre la humanización y la medicalización del final de la vida. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 18(9), 2541–2548. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232013000900008

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bermúdes, P., González, D., & Ortiz, R. (2016). El rol de la terapia ocupacional en cuidados paliativos en niños, niñas y adolescentes. Revista de Estudiantes de Terapia Ocupacional, 3(1), 12–25. https://acortar.link/WUM6ZX

- Connor, S. R., & Sepulveda-Bermedo, M. C. (2014). Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. World Health Organization & Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. https://acortar.link/WQGbYm.

- Constantinou, G., Garcia, R., Cook, E., & Randhawa, G. (2019). Children’s unmet palliative care needs: A scoping review of parents’ perspectives. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001705

- Downing, J., Boucher, S., Daniels, A., & Nkosi, B. (2018). Paediatric palliative care in resource-poor countries. Children, 5(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5020027

- Ferreira, A., Becker, H., da Graça, M., & Zanchi, D. (2015). Palliative care in paediatric oncology: Perceptions, expertise and practices from the perspective of the multidisciplinary team. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 36, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2015.02.46299

- Flexa, T. C., Silva, A. J., de Santana, M. E., & Nunes, J. (2018). Pediatric palliative care: Analysis of nursing studies. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE on Line, 12(5), 1409. https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963-v12i5a231901p1409-1421-2018

- Friedel, M., Aujoulat, I., Dubois, A. C., & Degryse, J. M. (2019). Instruments to measure outcomes in pediatric palliative care: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 143. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2379

- Gaab, E. M. (2015). Families’ perspectives of quality of life in pediatric palliative care patients. Children, 2(1), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.3390/children2010131

- Garcia-Quintero, X., Parra-Lara, L. G., Claros-Hulbert, A., Cuervo-Suarez, M. I., Gomez-Garcia, W., Desbrandes, F., & Arias-Casais, N. (2020). Advancing pediatric palliative care in a low-middle income country: An implementation study, a challenging but not impossible task. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00674-2

- González, C., Méndez, J., Romero, J., Bustamante, J., Castro, R., & Miguel, J. (2012). Cuidados paliativos en México. Revista Médica del Hospital General de México, 75(3). https://acortar.link/gJsi0O

- Leemann, T., Bergstraesser, E., Cignacco, E., & Zimmermann, K. (2020). Differing needs of mothers and fathers during their child’s end-of-life care: Secondary analysis of the “Paediatric end-of-life care needs” (PELICAN) study. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00621-1

- Lo, D. S., Hein, N., & Bulgareli, J. V. (2022). Pediatric palliative care and end-of-life: A systematic review of economic health analyses. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 40. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0462/2022/40/2021002

- Mota, F. R., Paredes-Téllez, M. Á., Rivas-Ruíz, R., & Villanueva-García, D. (2017). Conocimiento de cuidados paliativos pediátricos del personal de salud de un hospital de tercer nivel. Revista CONAMED, 22(4), 179–184. https://acortar.link/yE5aPC

- Norris, S., Minkowitz, S., & Scharbach, K. (2019). Pediatric palliative care. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 46(3), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2019.05.010

- Pan American Health Organization. (2016). Palliative care. Retrieved from https://www.paho.org/en/topics/palliative-care.

- Parodi, J. F., Morante, R., Hidalgo, L., & Carreño, R. (2016). Propuesta de políticas sobre cuidados paliativos para personas adultas mayores en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Horizonte Médico (Lima) Médico (Lima), 16(1). https://doi.org/10.24265/horizmed

- Pastrana, T., Lima, L., Pons-Izquierdo, J. J., & Centeno, C. (2013). Atlas de cuidados paliativos en Latinoamérica [internet]. Edición Cartográfica. https://acortar.link/O5s1Y2

- Pastrana, T., Lima, L., Sánchez-Cárdenas, M., Steijn, D., Garralda, E., Pons-Izquierdo, J. J., & Centeno, Carlos. (2021). Atlas de cuidados paliativos de Latinoamérica 2020 [internet]. https://acortar.link/ZoRSPO

- Pastrana, T., Lima, L. D., Centeno, C., Wenk, R., Eisenchlas, J., Monti, C., & Rocafort, J. (2012). Atlas de cuidados paliativos en Latinoamérica [internet]. https://acortar.link/hSOCVQ

- Rendón, M. E., Olvera, H., & Villasís-Keever, M. A. (2011). El paciente pediátrico en etapa terminal: un reto para su identificación y tratamiento. Revista de investigación clínica, 63(2), 135–147. https://acortar.link/81vh07

- Rodríguez, J. (2003). Vivencias y cuestionamientos que enfrenta el equipo de cuidado paliativo pediátrico del Hospital Nacional de Niños en relación a la atención brindada a sus pacientes: un análisis ético. Revista Enfermería Actual en Costa Rica, (6), 19. https://acortar.link/796u5y

- Scaratti, M., Oliveira, D. R., Rós, A. C. R., Debon, R., & Baldissera, C. (2019). From diagnosis to terminal illness: The multiprofessional team endeavior in pediatric oncology / Do diagnóstico a terminalidade: Enfrentamento da equipe multiprofissional na oncologia pediátrica. Revista de Pesquisa Cuidado é Fundamental Online, 11(2), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.2019.v11i2.311-316

- Simão, V. M., & Mioto, R. C. T. (2016). O cuidado paliativo e domiciliar em países da América Latina. Saúde em Debate, 40(108), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-1104-20161080013

- Verri, E. R., Santana Bitencourt, N. A., da Silva Oliveira, J. A., dos Santos Júnior, R., Silva Marques, H., Alves Porto, M., & Rodrigues, D. G. (2019). Nursing professionals: Understanding about pediatric palliative care. Journal of Nursing UFPE/Revista de Enfermagem UFPE, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963-v13i01a234924p126-136-2019

- Víctor, G. H. (2019). Cuidados paliativos no mundo. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia, 62(3), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2016v62n3.343

- Wolff, S. L., Christiansen, C. F., Nielsen, M. K., Johnsen, S. P., Schroeder, H., & Neergaard, M. A. (2020). Predictors for place of death among children: A systematic review and meta-analyses of recent literature. European Journal of Pediatrics, 179(8), 1227–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03689-2

- Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance & World Health Organization. (2020). Global atlas of palliative care, 2nd ed. [internet]. https://acortar.link/fXbNfm

- Zuniga-Villanueva, G., Ramos-Guerrero, J. A., Osio-Saldaña, M., Casas, J. A., Marston, J., & Okhuysen-Cawley, R. (2021). Quality indicators in pediatric palliative care: Considerations for Latin America. Children, 8(3), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8030250