Abstract

Traditionally perceived as a historical enemy, Turkey was ‘rediscovered’ in Armenia after it actively supported Azerbaijan in the 2020 Armenian-Azerbaijani war over Nagorno-Karabakh. This article traces some of the cultural-ideational reverberations of Turkey’s ‘return’ within Armenian society. It argues that the war was a (re-)formative moment since it simultaneously resulted in the emergence of new meanings and the revival of traditional ones. It brought the ‘distant’ neighbour into Armenians’ geographical/geopolitical imaginations, reshaping the meaning of Turkey and of the larger region for them. But it also reinforced long-established complex semantics of the ethnonym ‘Turk’, setting the stage for its instrumentalisation in internal politics.

Introduction

During a press conference held on 23 November 2021, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan was asked about the possibility of normalisation between Armenia and neighbouring Turkey. His answer was intricate and overloaded, yet telling. It touched upon perceptions of Turkey and Turks in his country, which were reconfigured and reanimated, as this paper shows, after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. In that second full-scale war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Turkey had actively supported the latter in its victory.

The prime minister responded: ‘We want to normalise relations with Turkey, but we would like to ask … Turkey and Azerbaijan—since they [speak of themselves as] “one nation, two states”: Are they willing to destroy Armenia, or not? Are they willing to continue with the genocide of the Armenian people and bring it to completion, or not?’ He then referred to a comment written beneath the Facebook announcement of his press conference. ‘We don’t need empty talk. We need peace which we don’t have,’ it read. Pashinyan described the author of the comment as a young woman whose cover photo featured her child and whose profile picture, depicting her marriage, had an added frame reading ‘The Turk is my enemy.’ ‘I was simply astonished,’ he remarked, ‘our whole politico-cultural subconscious problematic was expressed there, in that young woman’s comment, cover photo, profile picture … ’ He then proceeded by recalling his earlier statements where he, referring to Armenian-Turkish and Armenian-Azerbaijani relations, had proposed ‘to manage the enmity,’ thus triggering public criticism and discourse on ‘whether the Turk is our enemy or not,’ and went on to describe what he observed as a trend in the country: ‘There’s a very powerful tool for silencing anyone who expresses an unorthodox idea. [It consists in] telling them “You’re a Turk! You serve the Turk’s interest!”’ (Armenian Public TV, Citation2021, 2:06:04).

Pashinyan’s convoluted answer holds out some of the phenomena observable in post-2020-war Armenian society. His rhetorical questions and the quote of the Facebook user aching for peace betray a sense of threat, vulnerability, and anxiety vis-à-vis Turkey and Azerbaijan. The slogan appearing on the Facebook picture and reasserting hostility to the Turk, widely circulating on social media at the time, exemplifies a stiffening of anti-Turkish stances and discourse in Armenian society and politics. Whereas his mention of the ‘very powerful political tool’ refers to the highly increased usage of the label ‘Turk’ in the country’s internal political debates.

Based on qualitative research initiated in the Summer of 2021, this article traces the impact of Turkey’s involvement in the 2020 war on Armenian perceptions and representations of both Turkey and Turks. It thus has primarily a retrospective orientation, as it examines some of the social, cultural, and ideational ramifications of a rapid and mostly unexpected change in the geopolitical environment of Armenia characterised by a swift ‘return’ of Turkey to the region. But the discussion also holds relevance for the future of Armenia-Turkey relations, of which a new normalisation process was officially launched in December 2021 (Fraser, Citation2022). These relations, in fact, can barely be completely detached from the influence of domestic social and cultural factors which I analyse here. As argued by constructivist or sociological perspectives on international relations, states as social actors (Andrews, Citation1975; Katzenstein, Citation1996a), as well as their identities, preferences, perceptions, and even foreign policy behaviour are often not just constrained but also constituted and constructed (see Wendt Citation1999, pp. 25-27) by social and cultural determinants—norms, ideas, conventions, meanings, beliefs, expectations, representations of Self and Other—operating both at the systemic/inter-state and the domestic/intra-state levels (Finnemore, Citation1996; Hopf, Citation1998; Katzenstein, Citation1996b; Lapid & Kratochwil, Citation1996; Wendt, Citation1999). Far from providing any ‘a priori prediction per se’ (see Hopf, Citation1998, p. 197), this article examines the (re)construction of meanings, imaginations and perceptions in post-war Armenia that potentially might, in the near or distant future, act as ‘domestic-level norms … shap[ing] state interests’ (Kowert & Legro, Citation1996, p. 462) or ‘domestic sources of national security policy’ (Jepperson, Wendt & Katzenstein, Citation1996, p. 52), as has been observed in other contexts elsewhere (e.g. Johnston, Citation1996; Berger, Citation1996; Barnett, Citation1996).

The primary source of my analysis is a set of twenty semi-structured interviews that I conducted in Yerevan between July 2021 and January 2022. Most of my interlocutors were people who publicly speak and/or write about Turkey and Turks, thus participating in processes of meaning construction. They were analysts, journalists, Turkey experts, political activists, parliamentarians, and candidates in the 2021 parliamentary elections. I included people with a broad spectrum of views, from adamant supporters of Turkish-Armenian reconciliation to those who believed that Armenians and Turks cannot peacefully coexist. Aiming to assess understandings and attitudes among the more general public as well, my research also involved some field observation and reviewing Armenian news and social media.

In what follows, I first explain the history of Armenia-Turkey relations and describe how Armenians generally perceived Turkey and Turks until the recent war. Then I discuss the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and Turkey’s involvement in it, arguing that it changed not only the geopolitics of the region but also Armenians’ understandings and imaginations of it. Drawing on theoretical literature on geographical and geopolitical imaginations, I analyse the ‘(re)discovery’ of Turkey in Armenians’ mental maps, emanating from the hitherto ignored neighbour’s largely unexpected hostile intervention. I show in the third section how that intervention has led to an increased sense of threat, anxiety, and vulnerability vis-à-vis Turkey and Turks in Armenian society, how historical memories have been revived and future expectations darkened. The fourth section examines the growing preoccupation with the idea of the ‘Turk’ in post-defeat Armenia, its cultural and political workings, as well as the instrumentalisation of the label within the political crisis that followed the war. I end by arguing that the 2020 war and defeat constitute a (re-)formative moment for Armenian society as they resulted in the emergence of new meanings, imaginations, and narratives as well as the revival and reification of traditional ones at the same time.

Until 27 September 2020: Distant Neighbour, Historical Enemy

A 311 km long border separates Armenia from Turkey. Turkey has banned travel and trade across it since 1993, two years after the Republic of Armenia emerged from the Soviet Union as an independent state, as a sanction against Armenia and in support of Azerbaijan when the two Caucasian countries were at war over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Turkey also refused to establish diplomatic relations with Armenia, making any conciliation conditional upon the settlement of the conflict with Azerbaijan. Although a period of ‘football diplomacy’ led to the signing of protocols on the establishment and development of relations between the two sides in October 2009, the process was frozen a few months later and neither of the countries’ parliaments ratified the protocols. Increasing pressure by Azerbaijan on Turkey and by hard-liners in both countries and the Armenian diaspora are cited as factors contributing to the eventual collapse of that rapprochement process (Göksel, Citation2012; Hill, Kirişçi & Moffatt, Citation2015, pp. 132-3; Ter-Matevosyan, Citation2021, pp. 160-2). The sealed border did not entirely stop movement between the two countries and societies. Limited contacts between representatives of civil society, shadow trade of products imported from Turkey to Armenia and some labour migration in the opposite direction sustained a minimal level of connectedness (Hill, Kirişçi & Moffatt, Citation2015; Ohanyan, Citation2007). Nevertheless, Turkey remained a ‘distant’ neighbour for most in Armenia.

Distant Neighbour

Geography scholars have established that there is often a correlation between people’s physical movement and their sense of space (e.g. Casey, Citation1993; Feldhaus, Citation2003; Stein, Citation1977). The importance of the mere idea of such a movement’s possibility has been noted as a factor that generates spatial or regional awareness. As Casey (Citation1993) described this dynamic: ‘I take myself to be here in this house or block or neighbourhood, in this state or nation, whenever I am convinced that … I can in principle move (in person or by proxy) to any part of this region, however far-flung this part might be’ (p. 53). The impermeability of the Turkish-Armenian border had pushed Turkey out of Armenians’ sense of the ‘here’ despite the physical proximity of the countries. The fact that the limited trade and mobility have occurred only by circumventing the border through Georgia, not by crossing it, has increased the perception of the border as a barrier rather than a port of entry. Although there have been direct flights between Yerevan and Istanbul for most of the last two decades, flying entails merely moving ‘through a tube of ignorance between two points on the Earth’s surface,’ as Gould and White eloquently put it (Citation1986, p. 83), offering no spatial experience of movement on the ground and preventing travellers’ cognitive region-making potentialities. Flying entails moving to, whereas regions are brought into being in people’s minds through moving across them (Feldhaus, Citation2003, p. 211).

As a result of this long-term separation, Turkey was merely a distant neighbour in the geographical imagination of residents of Armenia until the war in September 2020. It was not a constitutive element of their region, understood as a ‘concatenation of places that, taken together, constitutes a common and continuous here for the person who lives in or traverses them’ (Casey, Citation1993, p. 53). Being a disconnected place (see Feldhaus, Citation2003), it was almost absent from their regional awareness. Lacking the political, economic, cultural, and administrative practices and discourses necessary for the social construction of regions (see Paasi, Citation2001, p. 16), and not being ‘active[ly] gather[ed]’ through direct bodily movement and interaction, the two countries have barely gone through a process of ‘regioning’ in the mental maps of Armenians (see Casey, Citation1993, p. 74). The closed border led to not just alienated borderlands (see Martinez, Citation1994), but alienated countries and societies in general. What was beyond the border was at most imagined as a lost homeland by many Armenians whose ancestors fled the 1915–1923 genocide committed by the Young Turks’ Ottoman government (see Leupold, Citation2020, pp. 155-7), instead of being experienced as a neighbouring and tangible nation-state. As AramFootnote1, a historian in his mid-forties, told me:

We used to live in an illusory condition. We gained our independence [from the USSR], but Turkey remained something mythical for us as there haven’t been any real relations [with it]. See, for instance, [the example of] Iran. [It] turned into something living, something real. We understood that the Persians are not just King Shapur, [that] there are real, living Persians … [But] Turkey was not a living thing …

In addition to and following this geographical-imaginative detachment, Turkey was somehow withdrawn from the average Armenian’s geopolitical awareness as well. It was barely perceived as part of the immediate geopolitical web in which Armenia was situated and was not expected to have any direct engagement with the country. This was not only due to the lack of official relations between the two states. In Armenian popular geopolitics (see Ó Tuathail, Citation1999), or Armenians’ geopolitical vision of order (see Dijkink, Citation1996, pp. 15-6), there has been a general assumption that Turkey would never be allowed to ‘enter the region.’ ‘We always thought that Turkey’s membership in NATO would keep it away from our region where Russia is the primary actor,’ explained Naira, a candidate in the June 2021 parliamentary elections, clearly putting Turkey outside ‘our region.’ Hakob, a journalist who often writes and speaks about Armenian-Turkish relations and their history, concurred. He had never thought that Turkey posed a direct threat to Armenia(ns) as long as Russian forces were militarily present in the country. ‘Not because the Russians would defend us from Turkish aggression, but because the Turks have some limits and boundaries in their relations with the Russians and they would never cross those red lines. They would always remain behind the river Arax’—he clarified his point using spatial-geographical imagery that placed Turkey outside certain lines marking the imagined geopolitical region to which Armenia belonged.

Historical Enemy

Despite being ‘distant’ neighbours, despite being relegated to the periphery of average Armenians’ geo-awareness—a term I use to refer to both geographical and geopolitical awareness—Turkey and Turks have had a prominent place in Armenian historical awareness. They were not absent from public discourse or popular imagination before the war, but perceptions of them were primarily limited to the realm of historical memories connected with the genocide in the early twentieth century. Through stories of surviving-victim family members, as well as through media and history education in schools (see Akpınar et al., Citation2019; Dudwick, Citation1994, pp. 65-9; Fırat et al., Citation2017; Kharatyan-Araqelyan, Citation2010; Zolyan & Zakaryan, Citation2008), memories of the genocide have been maintained and a negative image of Turks has been reproduced.

The pre-war perception of Turkey and Turks—even if ‘mythical’ in the words of the historian quoted above—was thus already negative and antagonistic. This has been confirmed in opinion surveys (ACNIS, Citation2005; CISR, Citation2018; CRRC-Armenia, Citation2015), ethnographic research (Kharatyan-Araqelyan, Citation2010), and my interviews. Being almost outside Armenians’ geo-awareness, Turkey and Turks constituted more of a symbolic Other rather than an actual imminent threat. A 2017 study described the pre-war situation as follows: ‘[T]here are no current immediate security threats, no reasonable expectations of hostilities between the two states, much less between dispersed peoples … Instead, it is the public memory of 1915 … that most deeply informs [Armenian-Turkish] inter-personal, inter-communal, and inter-state relations’ (Seferian, Citation2017, p. 4).

Turkey’s (Unexpected) Return: Changing the Region and its Emic Perception

The 2020 Karabakh war brought Turkey and ‘the Turk’ closer again, as contemporary Armenians encountered the ‘historical enemy’ in a more direct way than ever. On the morning of 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan launched a full-scale military offensive against the breakaway unrecognised Republic of Artsakh (previously Republic of Mountainous Karabakh), situated within the internationally recognised borders of Azerbaijan but administered by ethnic Armenian inhabitants with the support of Armenia. Decades earlier, in September 1991, the Republic of Mountainous Karabakh was declared independent by Armenians who formed a majority in the then Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) within Soviet Azerbaijan. The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh had soon turned into a war between the two sides, which ended in May 1994 with Armenians establishing control over most of the previous NKAO as well as seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts.

From the beginning of the 2020 Karabakh War, Armenia, acting as security guarantor of the Republic of Artsakh and mobilising its troops in defence of the latter, officially declared that Turkey was actively participating on the side of Azerbaijan with a ‘direct presence on the ground.’ A 28 September statement by the Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs mentioned not only Turkish UAV and warplane supplies to the Azerbaijani army, but also Turkish military experts’ direct presence and Turkey’s recruitment and transportation of foreign mercenaries to the battlefield (Hetq, Citation2020). Turkey’s direct involvement was soon confirmed by Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu who spoke of Turkey supporting Azerbaijan ‘in the battlefield’ (TRT World, Citation2020), and the Armenian side’s allegations were later corroborated by various international, Azerbaijani, and Turkish sources (Kenez, Citation2021; Parliamentary Assembly, Citation2021; Soylu, Citation2020; Turan, Citation2021; UNHCR, Citation2020; see also Cheterian, Citation2022, p. 16).Footnote2 Although not inside the borders of the Republic of Armenia, Armenians were thus witnessing a major episode of direct Turkish aggression for the first time since a century ago.Footnote3 ‘Though not in a straightforward manner, it was, in essence, Turkey warring against Armenia,’ a prominent political analyst in Yerevan told me.

The war ended on 10 November 2020 with the victory of Azerbaijan and Turkey. Armenia incurred significant territorial losses, including not only the seven adjacent districts but also portions of what used to be the NKAO. About 4000 Armenian soldiers perished during the 44 days of the war (Tass, Citation2021). Turkey’s president attended the victory parade in Baku on 10 December 2020 alongside his Azerbaijani counterpart. A Turkish commando brigade also took part, in addition to Turkish-supplied ‘Bayraktar’ UAVs known for their decisive role in the outcome of the war (Al Jazeera, Citation2020).

Turkey’s intervention in the second Nagorno-Karabakh war has been assessed as a geopolitical game changer in the South Caucasus region. By directly inserting itself in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Turkey, as some experts maintain, compelled Russia—which traditionally perceived the South Caucasus as its ‘near abroad’—to tolerate Turkey’s presence as an actor in the region (Broers, Citation2021, p. 260; Soylu, Citation2020; Stronski, Citation2021).

‘Realising Where We Are’

I argue that the 2020 war has returned Turkey not only to the region (see Soylu, Citation2020) but also to the regional awareness of Armenians. It has shifted not only the geography of the South Caucasus, as Stronski (Citation2021) asserts, but also the geographical and geopolitical imaginations of Armenians. After decades without movement across the Turkish-Armenian border, the movement of Turkish armaments, F-16 jets, and military advisors and personnel to the de facto Armenian border in Karabakh made both Turkey and the shifting region ‘imaginatively visible’ for Armenians (see Feldhaus, Citation2003, p. 38). Turkey suddenly became real and tangible for them, revolutionising its previous ‘mythical’ perception and returning to their regional awareness.

Having cognitively distanced Turkey and left it outside of their geo-awareness, many Armenians had not expected it to intervene in the military confrontation with Azerbaijan. Experts of Turkey are an exception in this regard. One such expert, an opposition MP from the ‘Armenia’ faction, explained why he was not surprised when Turkey joined the hostilities: ‘I wake up every morning and monitor the Turkish newspapers, Turkish politicians’ Twitter accounts, etc.’ Most others, however, including politicians and political analysts, admitted that they had not considered Turkey to be a real threat and had not expected its involvement in the conflict to be as serious as it was. Even an MP from the ruling party admitted being ‘shocked’ by Turkey’s direct participation in the war, even though she had read the government’s National Security Strategy published in July 2020, which found ‘Turkey’s readiness for covert or overt intervention in the case of Azerbaijani-initiated military actions [to be] particularly problematic’ (Republic of Armenia, Citation2020, p. 6). Two months before the beginning of hostilities, the leader of the ruling parliamentary faction, Lilit Makunts, had also confidently denied the possibility of Turkey joining Azerbaijan in a military intervention, even when news about intensified contacts between the two countries’ military leaderships were circulating in the media (Armenpress, Citation2020a). In a February 2022 interview, another MP from the ruling party admitted that the Armenian leadership had misevaluated the risks and prepared the country for war only against Azerbaijan rather than multiple parties, hinting obviously at Turkey as well (1in TV, Citation2022).

But the war-engendered shifts in Armenians’ regional awareness go even further than the ‘return’ or ‘rediscovery’ of Turkey. Karine, a writer in her early sixties, reflected on the war’s effects: ‘Syria has always been so close to us, but we somehow felt that we were closer to Europe … Maybe because back in Soviet times Europe was “our neighbour” really … Only now [after the war] we are realising where we are.’ The where of post-war Armenia has begun to be imagined, as Karine’s comments suggest, in relation to Turkey and the broader region of the Middle East. Like foreign analysts noting increasing geopolitical and economic connections between the Caucasus and the Middle East (e.g. Stronski, Citation2021), Armenian experts have started constructing a narrative about the ‘Middle-Easternisation of our region’ (Safrastyan, Citation2021; see also Hovyan, Citation2020). In a lecture to an audience of Armenians in Burbank, California, in November 2021, I watched a young expert on Turkey from Yerevan and a former advisor to the President of Armenia, saying: ‘Turkey’s entry into the region through the war and its transport of Middle Eastern mercenaries to fight against Armenians attest to the fact that our region is becoming part of the Middle East.’

An Increased Sense of Threat and Vulnerability

Disturbances to perceived geopolitical orders are known to engender feelings of insecurity (see Dijkink, Citation1996, p. 16). Turkey’s participation in the war has visibly produced a sense of vulnerability vis-à-vis Turkey and Turks in Armenian society. The previously ‘theoretical threat’, in the words of the historian Aram, the sense of which was passed down also in cultural forms—such as the traditional song about the ‘Sultan willing to exterminate us’ that the parents of another interlocutor taught him when he was a child—, was now materialised for the first time. Habet, a middle-aged activist, provided a lucid exposition of this impact of the war:

The last direct threat on the part of Turkey was a century ago. After that, we lived with the memories of that tragedy. We remembered that the Turk [was] evil because we remembered that massacres took place in 1915. Otherwise, Turkey did not give any real and palpable reason [for us to feel threatened] … We weren’t in a state of war. Now, there is a threat coming from Turkey. An obvious, objective, quantifiable, visible threat. Turkey is a more dangerous state for us than Azerbaijan.

Return of the ‘Haunting Spectrum’

A significant manifestation of the increase in feelings of vulnerability and anxiety was the resurfacing of discourse on the genocide. This resurrection of the ‘haunting spectrum’ was visible both in Armenia and in the diaspora (see Adjemian & Davidian, Citation2021). From the beginning of the hostilities, parallels were drawn by state officials. Prime Minister Pashinyan tweeted that ‘Turkey returned to the South Caucasus […] to continue the Armenian Genocide’ (Pashinyan, Citation2020), and President Armen Sargsyan warned about the return of ‘the ghost of the Ottoman Empire that 105 years ago masterminded the Armenian Genocide’ (Armenpress, Citation2020b). This was surely more than a matter of state propaganda, as it was accompanied by countless such comparisons being made in Armenian traditional and social media.

Common themes included the portrayal of the Turkish ‘Bayraktar’ Unmanned Aerial Vehicle as the modern version of the infamous Ottoman yataghan swords, remembered for being used during the genocide (e.g. Fifth TV, Citation2021). Pictures of the Armenian exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh were juxtaposed with pictures of 1915 deportations of Armenians from Ottoman towns (e.g. ), and comparisons were made between the beheadings of Armenian civilians and prisoners of war in 2020 (see Roth, Citation2020) and those of the victims of the genocide (see Ghaletchyan, Citation2021). The dates ‘1915’ and ‘2020’ started to frequently appear next to each other. Even the symbolism of 24 April, the day on which Armenians commemorate the genocide, was expanded to include those who perished during the 2020 war. A homemade leaflet during the electoral campaign period for the June 2021 snap elections read: ‘From now on, on April 24 and always, I elect my countless martyrs and [our] sons that were sent to the gallows before our eyes’ (see ). When I asked Mariam, a 37-year-old saleswoman, whether their family had any victims during the 1915 genocide, she said, ‘No, but we had martyrs during this war’, indicating a cognitive linkage between the two events.

Figure 1. A collage circulated on social media during the war, drawing a comparison between Armenians deported during the 1915 genocide and Armenians fleeing Nagorno-Karabakh during the 2020 war.

Figure 2. Leaflet reading ‘From now on, on April 24 and always, I elect my countless martyrs and [our] sons that were sent to the gallows before our eyes—an Armenian’. Photographed by the author in Yerevan, Armenia, July 2021.

![Figure 2. Leaflet reading ‘From now on, on April 24 and always, I elect my countless martyrs and [our] sons that were sent to the gallows before our eyes—an Armenian’. Photographed by the author in Yerevan, Armenia, July 2021.](/cms/asset/05deeb0b-2fd2-45e0-8d37-6f5d35ce4874/reno_a_2176587_f0002_oc.jpg)

A similar reactivation of genocide memories occurred during 1988–1990 when pogroms were carried out against ethnic Armenians in Azerbaijan in response to the growing Karabakh Movement in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh (Marutyan, Citation2009). But Turkey was not involved back then. The genocide discourse during the 2020 war was more straightforwardly linked to Turkey and Turks as the historical and contemporary perpetrators, establishing a direct continuity through an ‘optical illusion between contemporaneity and its other’ (Das, Citation1995, p. 121). My interlocutors did not necessarily think that Turkey’s political aim during the 2020 war was ‘to continue the Armenian Genocide’ as the Prime Minister had claimed in his tweet. A few were even openly critical of such interpretations and described them as a ‘national obsession with the genocidal past.’ But several did evaluate the war as ‘genocidal’, as a ‘small scale genocide’ or a ‘generational genocide’ which took the lives of thousands of young Armenian men. Others did not rule out the possibility of future genocidal acts by Turkey, citing Turkish officials’ denial of the 1915 genocide and sustained anti-Armenian discourse, as well as President Erdogan’s praise of Enver Pasha, one of the top Ottoman officials responsible for the 1915 genocide, during the 2020 Baku victory parade (see Cheterian, Citation2020). ‘This war showed us once again that Armenians’ existence is at risk in our region’, argued Sipan, a 30-year-old university lecturer.

‘Turkey’s Plans’

My interlocutors speculated on the ‘returning’ neighbour’s possible plans. These ranged from wiping the Armenian state off the map, as alluded to by the prime minister in his remarks quoted in the introduction, to Turkey’s ambitions to pull Armenia under its political and economic influence. Many among the people I interviewed and those making comments in the Armenian media spoke of the risk of losing Armenian statehood. Ruben, who had also been an assistant to the former president Armen Sargsyan, thought that ‘Armenia is the only state in the world that has two neighbours willing to eradicate it.’ Gegham, a young Turkey expert, shared this feeling of threat from what he called the ‘Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem’. He thought that Turkey perceived Armenia as a factor hindering its geopolitical expansion towards the east. ‘Unfortunately, Armenian sovereignty is in direct contradiction with Turkey’s regional plans’, he observed.

Several of my interlocutors believed that Turkey is implementing a pan-Turkic project to expand its geopolitical influence towards the other Turkic-speaking states in Eurasia and that it perceives Armenia as a bone in its throat. They pointed to the fact that Turkey and Azerbaijan waged the 2020 war under their ‘one nation, two states’ slogan (see Daily Sabah, Citation202Citation0) and mentioned the Azerbaijani presidents’ statements making territorial claims over the southern Armenian region of Syunik (see Kucera, Citation2021), which aim, they believed, to establish a land link between the two countries. Karine, the writer, watched the victory parade of Azerbaijani and Turkish forces in Baku on YouTube. She said it was revelatory for her as it helped her ‘understand that the project of pan-Turkism is real.’

Yet others thought that Turkey would not physically dismantle Armenia, since it also needs it as part of a buffer zone between itself and Russia, but will instead continue to exert pressure to turn Armenia into a ‘vassal state.’ Armenia would then neither impede Turkey’s eastward economic and geopolitical expansion nor serve as a foothold for third parties against it. Turkey would also demand concessions from Armenia, they thought, such as asking to drop demands of genocide recognition. Only two of my twenty interlocutors said that they did not perceive Turkey as a threat, arguing that it had already achieved its aims with the war. A third interviewee, a candidate in the June 2021 elections usually speaking in favour of normalisation of relations with Turkey, first recounted the geopolitical reasons why she believed Turkey would not or could not eradicate Armenia physically, but then added, ‘[I might be] consoling myself with these thoughts because I would have to pack my bags [and escape] otherwise.’

The majority thought that Turkey’s involvement in the war signalled the beginning rather than the end of its return, and that ‘the 2020 war will not be the last time we encounter that threat’, as one prominent political analyst put it. When I asked Ruben whether he really thought the ‘Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem’, as he referred to it, threatened Armenia’s existence altogether, he smiled and replied: ‘There’s a Jewish saying: “When someone tells you about their intention to kill you, take them seriously.”’

The ‘Turk’: Consolidated and Omnipresent

In the Summer of 2021, I observed a conference at a state-run academic institute in Yerevan. During a break, a policeman stopped me as I came outside. He asked, in English, where I was from, then apologised after hearing my response in Armenian and let me walk away. Upon my return, he approached me again. Starting an informal interrogation, he asked me who I was, why I was there, and requested to see my documents. I declined his unjustified request, saying that I had come to observe a conference open to the public, and walked to the conference room, only to find two other security guards suspiciously staring at me. I noticed that a board member of the academic centre was making calls and asking people around whether they knew me. I reminded her that we had met before. Embarrassed, she apologised and tried to explain what had just happened: ‘They thought you were from the neighbouring country.’ My ‘unusual look,’ particularly my moustache, she specified, had made the policemen think that I could be a Turk who had come to sabotage the conference, which had the topics of the Armenian Genocide and the 2020 Karabakh war—a remarkable pairing, again—at its centre.

The day before that incident I had attended a book presentation organised by a non-governmental organisation in Yerevan. The book was the outcome of Turkish-Armenian cooperation, and the event was conceived as part of a project on Turkish-Armenian normalisation. The invitation email I had received a week before included an unusual notification: ‘Please note that given the sensitivities that this type of a project may entail, particularly after the second Karabakh war, this will be a closed, low-profile event for invitation holders only’ (emphasis in original).

These two incidents are indicative of yet another societal reverberation of the 2020 Karabakh war. They speak of the significantly heightened and almost obsessive engagement with the idea of the ‘Turk’, which has two mutually sustaining dimensions. One is the increased perception of the Turk as an imminent threat, exemplified by the first vignette above. The other consists of a growing discourse on ‘internal Turks’ and their witch-hunt, which the Armenian NGO organising an event dedicated to Turkish-Armenian reconciliation was apparently trying to avoid by limiting attendance to invitees.

Semantic Complexities, Reinforced Meanings

In Armenia, the ethnonym ‘Turk’—with the ‘u’ pronounced as an ‘oo’ in ‘loop’—is typically used to refer to the ethnic Turks in the Republic of Turkey as well as to the people of Azerbaijan—at least the Turkic-speaking amongst them (Abrahamian, Citation2006, p. 251). In the Soviet era, according to my interlocutors who remembered them, the term referred to the Turkic-speaking Muslim residents of Soviet Armenia—those who would later become Azerbaijani citizens. Most of my interviewees used the term ‘Turk’ this way. When asked to clarify, some genuinely thought that Azerbaijani and Turkish people are ‘the same Turks’ and mobilised primordialist arguments in support of their thesis. Others believed that Azerbaijanis are religiously and historically distinct from Turks of Turkey, but still consistently used ‘Turk’ when referring to them. As several of my interlocutors observed, this emic conflation became reified during the recent war that Turkey and Azerbaijan unleashed as ‘one nation, two states.’

In certain contexts the term’s meaning can even partly detach itself from its ethnic signification, becoming abstracted to simply mean ‘the enemy.’ ‘The term “Turk” has a much broader semantic range in Armenian, one that goes way beyond the ethnie’, Aram the historian maintained. Echoing Aram’s argument, Yervand, a former diplomat, explained further: ‘The “Turk” has a much larger meaning among us. It has even become a synonym for “enemy” to the extent that I’ve heard, for instance, [statements like] “the Russian is the Turk of the Pole” or “The Russian is more Turk than the Turk.”’ This dimension of the term’s semiotic complexity appeared frequently in my conversations. Several people remembered learning the term with this connotation in early childhood. Some told stories about their parents scolding them when fighting with their siblings by saying, ‘You aren’t Turks to treat each other like this, are you?!’ I spoke with Vahram about this, a member of an opposition movement that self-identifies as ‘national-socialist.’ I asked whether in his opinion the consistent use of the word ‘Turk’ as a derogatory label in internal politics (to be discussed below) would not result in the spread of anti-Turkish racism. He disagreed and argued: ‘You’re giving that word too much of an ethnic meaning, whereas I’m giving it an existential connotation—we define “Turk” to mean anything that poses an existential threat to us.’

This Turk-as-enemy or Turk-as-threat conceptual pairing is not just the result of memories of the genocide or an outgrowth of the related concept of the ‘historical enemy.’ It has been consistently maintained and reified in recent and current times as well, at least since the first Nagorno-Karabakh war and, importantly, during the 2020 war. Gegham argued: ‘People simply see the videos of how their co-villager is being beheaded during the war and think, “Man, they’re beheading him! Man, they are Turks, it’s true [that] they’re Turks”, suggesting how stereotypes get reinforced through novel instances of violence conforming to them. Norms, socioculturally constructed collective expectations for the behaviour of actors with a defined identity (see Katzenstein, Citation1996a, p. 5), are known to solidify through iteration (see Kower & Legro, Citation1996, p. 472). Several others whom I spoke with also agreed that the image of the ‘Turk’ as ‘the one who can injure [the Armenian]’ has been reaffirmed during the latest war. As one of my interlocutors maintained, this happened through a ‘subconscious reaction’ to the war during which, as another said, ‘our society saw its children being massacred with none other than Turkish Bayraktars [UAVs]’.

A related impact of the war is that this perception of the Turk as the inimical other is now much more thought of as a ‘necessary defensive mechanism’ in times of increased vulnerability. After Armen Grigoryan, Secretary of the Security Council of Armenia, was reluctant to describe Turkey as an ‘enemy state’ during a televised interview in March 2021 (News am, Citation2021a), and Prime Minister Pashinyan spoke of the need to ‘manage’ the Turkish-Armenian enmity (Armenpress, Citation2021), the ‘The Turk is my enemy’ campaign was initiated as a reaction by nationalist hardliners in the opposition. The sentence frequently appeared on protest banners and on profile pictures of Facebook users such as the woman about whom Pashinyan spoke during the press conference cited in the introduction (see and ). Habet feared that the authorities’ post-war discourse on possible normalisation of relations with Turkey and their calls for ‘managing enmity’ could result in society’s ‘lowering the guard vis-à-vis the increased Turkish threat.’

Turks Everywhere?

In addition to reinvigorating the inimical perception, the war has also turned the Turk into a ubiquitous threat in the imagination of many in Armenia—even though the number of Turks residing in the country is truly negligible.Footnote4 This suggests a somehow paranoic state in the immediate post-war period of increased vulnerability and anxiety, evident in random interactions in public. As had happened to me at the conference, my colleague and her friends, all of them diasporic Armenians, were suspected of being ‘Turks’ when they were visiting Metsamor, home to a nuclear power plant, in February 2022. A local questioned them, asking for proof of identity. The informal interrogator was not satisfied, even when it was clear that they could speak Armenian. ‘They [Turks/Azerbaijanis] have been learning Armenian too, that’s how they infiltrated us and won the war,’ he told them. Perhaps he had heard the rumours about ‘the city being full of Turks’ that were circulating in Yerevan soon after the end of the war. Mariam, the saleswoman, believed these rumours because one of her relatives had heard two people ‘speaking in Turkish’. ‘Maybe they are not that many,’ she said, ‘but they have come for sure. And they’re frightening because they’re apt to do anything … See the horrors they committed during the war?’ Karine, the writer, told me that she thinks that Turks have probably infiltrated the Armenian state apparatus and even Facebook using Armenian names. The arrival of Russian citizens after economic sanctions were placed on Russia in the context of the war on Ukraine triggered a new wave of rumours about ‘Turks arriving disguised as Russians.’

These fears were also stoked by members of the political opposition who blamed the government for ‘opening the country for Turkey and Turks.’ In September 2021, for instance, three Iranian tourists were taken to a police station in central Yerevan after opposition activists had ‘caught’ them as ‘Turks’ and ‘spies of Azerbaijan’ because a Turkish flag was sewn on the pants of one of them (See Hayeli Am, Citation2021a; Iravaban, Citation2021; News am, Citation2021b). Two months later, an opposition TV channel ‘alerted’ the public to the presence of ‘Turk-Azerbaijanis conducting interviews with Azerbaijanis in the hearth of Yerevan’. They even contacted the Foreign Ministry to question how a Turkish journalist was allowed in Yerevan (Armenian Second TV Channel, Citation2021). In February 2022, war veterans blocked the roads from Yerevan’s Zvartnots International Airport to the city centre at the time of arrival of the recently re-established flight from Istanbul. They intended, they said, to prevent Turks from entering the country (News am, Citation2022). A recently proposed legislation aiming to make Armenian citizenship acquisition easier for foreign investors was portrayed as a bill intending to pave the way for ‘the Turks to be able to become citizens of the Republic of Armenia’ (Panorama.am, Citation2022).

‘Internal Turks’

In addition to ‘real Turks’ being expected, feared, searched for, and ‘discovered’, there has also been a widespread witch-hunt of ‘internal Turks’ after the defeat in the war. In fact, not all statements and media coverage mentioning ‘Turks in Armenia’ are about actual Turks. Many are about Armenians, usually political figures, who are labelled as ‘Turks’ (e.g. Hayeli Am, Citation2021b; Manukyan, Citation2021). Far from being completely novel (Abrahamian, Citation2006; Adriaans, Citation2017), this phenomenon has arguably reached unprecedented levels in the post-defeat period.

The aftermath of the war in the Fall of 2020 led to a political crisis in the country. On the night the ceasefire agreement was signed, demonstrators stormed the parliament, the government building, and Prime Minister’s residence, while parliamentary speaker Ararat Mirzoyan was heavily beaten by a mob (Cookman, Citation2020). Then waves of demonstrations paralysed central parts of Yerevan for weeks. The concepts of the ‘Turk’ and ‘Turkish threats’ were instrumentalised in this internal political struggle, not just by blaming the authorities for ‘opening the country for the Turks’ as described above, but also by presenting them as Turkey’s agents, as Turkey sympathisers, or simply as ‘Turks’. ‘Turk Nikol’—referring to the prime minister—became a common expression read on social media and heard at rallies organised by the opposition Homeland Salvation Movement. The movement’s main slogan soon changed from ‘Armenia without Nikol’ to ‘Armenia without Turk[s]’, which was chanted by large numbers of protestors in the streets of Yerevan (Newspress am, Citation2021). Parliamentarians from the ruling party were ‘visited’ by groups of activists who shouted ‘Turk! Turk!’ outside their residences (Sukiasyan, Citation2022). Protesters in the south of the country greeted PM Pashinyan chanting the same label (Citation168.am, Citation202Citation1).

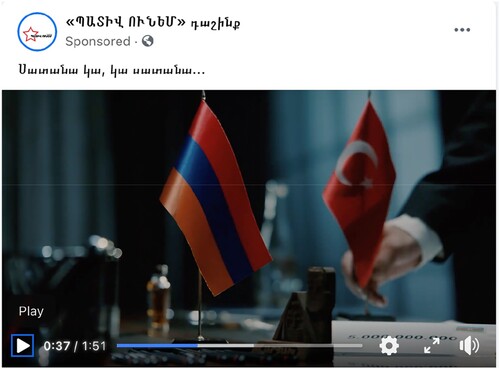

Mounting pressure from different political actors and factions within the state, including the military, led to the resignation of Pashinyan on 25 April and a call for snap parliamentary elections scheduled for 20 June 2021. Some opposition parties pointedly associated Pashinyan with Turkey and Azerbaijan during their electoral campaigns. ‘Participate in the elections, lest Ibrahim wins’, proclaimed a large black banner on central Mashtots Avenue in May 2021. Ibrahim, a Muslim name also used in Turkey, was used to refer to the Turks of whom Pashinyan was portrayed to be a puppet. The campaign video ad of the ‘I Have Honour Alliance’, now represented in the parliament, portrayed Pashinyan as a devil who cooperated with Turkey and Azerbaijan and gave away Nagorno-Karabakh (see ). After Pashinyan retained his seat as Prime Minister, receiving about 54 per cent of votes—significantly lower than the 70 per cent his alliance had got in December 2018—his victory was labelled by some as ‘the victory of the Turks.’

Figure 5. ‘There is a devil, there is a devil’. Still frame from the campaign video ad of the ‘I have Honour Alliance’, posted on the alliance’s Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/pativunenk/videos/512920409924360.

When I asked opposition activists and politicians to explain their usage of the label ‘Turk’ against the authorities, they usually had recourse to the Turk-enemy conceptual pairing examined above, maintaining that the actions of the authorities were, whether purposefully or not, directed against Armenia’s interests and serving the Turkish and Azerbaijani agendas. ‘We think that there is the Turk and there is the internal Turk. These two serve an identical function: acting against our state,’ explained a member of the ‘I Have Honour’ opposition faction in parliament. A parliamentarian from the other opposition bloc, ‘Armenia’, told me that ‘it’s just a political assessment. It’s because we are convinced that they are doing exactly what the Turk would do. What Erdogan or Aliyev would do. That much damage, that much harm, only the Turk could do.’ ‘The Turk is the enemy that cooperates with the Turk’, argued Gegham, the Turkey expert, in a convoluted sentence in which the first ‘Turk’ referred to the ‘internal’ whereas the second to the ‘real’ Turk.

Of course, the usage of the label ‘Turk’ in political discourse entails more than just an innocent ‘political assessment’ of the authorities and their actions. Beyond being applied in the sense of ‘injurer’, ‘threat’, or ‘enemy’, beyond being a mere manifestation of some people’s probably genuine conviction that ‘the authorities serve Turkey’s interests,’ the label ‘Turk’ is also—perhaps chiefly—advertently instrumentalised and strategically used for political purposes. Narek, often using the word ‘Nikol-Turks’ when speaking about Pashinyan’s supporters, admitted plainly that the term is ‘very aggressive propaganda against the Nikol supporters.’ He argued that ‘[arousing] irrational feelings is essential in times of mobilisation’, and that ‘anti-Turkishness is a mechanism for mobilisation [against the authorities].’ Habet, who identifies as a ‘political technologist’ (see Wilson, Citation2005), tellingly explained that the label ‘Turk’ was not such a powerful weapon until the war, since it used to have only historical connotations back then.

The war, and its effect on the increase of vulnerability and fear from Turkey and Turks, have thus clearly valorised the label of ‘Turk’ in internal politics. The circulation of the label, in turn, would only further exacerbate those anxieties and contribute to the (re)construction and stiffening of the traditional stereotypical image and connotations of the ‘Turk’ in Armenia. In this vicious circle, an ‘activation’ of the Armenian-Turkish symbolic boundary (see Tilly, Citation2004, p. 223) is underway, arguably jeopardising earlier attempts at informal normalisation between the two societies (see Hill, Kirişçi & Moffatt, Citation2015).

Conclusion: From (re-)Formative Moment to Cloudy Prospects

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war brought Turkey closer to post-Soviet Armenia and its people than it had ever been, thus somehow resetting Armenian-Turkish relations. Whereas these relations were previously focused on history, memory, and retrospection, the war abruptly brought them into the present, shaping expectations about an imminent future. Turkey moved not only into the region but also into Armenians’ geo-awareness, providing a new understanding and imagination of ‘our region’ for them. Redefining the meaning of Turkey, from distant/historical to near/imminent threat, and reconfiguring the perception of the region ‘where we are’ in the Armenian worldview, this war has been a ‘formative moment’ to a certain extent, a concept used by Ringmar to describe ‘times when new meanings become available’ (Citation1996, p. 86) due to major political occurrences or ‘critical events’ in nations’ journeys (Das, Citation1995).

However, the cultural-ideological impact of this war also includes the revival of long-existing meanings and symbolism. The conflation of Turks and Azerbaijanis under the umbrella term ‘Turk’ was reified because of the aggression meted out by the ‘one nation, two states’ tandem, and the synonymity of ‘Turk’ with ‘enemy’ or ‘threat’ was only consolidated. Manipulating the reinvigoration of the traditional concept of the ‘Turk’ and playing on its complex semantics, political groups employed it as a label in internal politics. Although this discourse was criticised by many in Armenia (e.g. Davtyan-Gevorgyan, Citation2021), including several of my interlocutors, its rise could in turn reinforce the traditional negative construct of the ‘Turk’ at least among some segments of Armenian society. In this sense, if ‘formative moments’ entail the contestation and breaking down of traditional identities, metaphors, and stories (Ringmar Citation1996, pp. 83, 85, 156), this war also constituted a re-formative moment for Armenian society wherein some old narratives and meanings were re-formed, revived, reified, and solidified. The war and its immediate aftermath have thus been ambiguous in terms of their cultural effects on Armenian society, constituting a (re-)formative moment.

What remains to be seen, as well as studied by scholars in the field, is how these cultural-ideational structures and processes in the current moment might relate to the more practical relations between the two neighbouring countries in the near or distant future. Following constructivist arguments maintaining that ‘noncultural factors can, under certain circumstances, shape the evolution of culture [yet] at the same time … cultural forces have a significant impact on how states respond to the structural conditions … under which they operate’ (Berger, Citation1996, p. 319), one can expect a two-way influence process in this regard. In other words, how/to what extent would these cultural-ideational factors influence Armenian policy vis-à-vis Turkey and how, in turn, would the future state of relations, whether characterised by normalisation or further antagonism, impact those domestic sociocultural processes?

I had interviewed most of my interlocutors before the new dialogue initiative aimed at the normalisation of relations between the two countries was unveiled in December 2021. They were, at the time, divided over whether normalisation was appropriate. Some were vehemently against renewed talks, while others eagerly supported and even publicly advocated normalisation often thinking that ‘Turkey already got most of what it wanted.’ Importantly, both views were at least partly shaped by the war and the resulting increased sense of vulnerability and threat. Whereas some believed that negotiating would only result in further concessions, others argued that direct talks were necessary ‘to mitigate the threat.’ More recently, most respondents to a June 2022 survey expressed negative opinions about normalisation with Turkey (48% ‘very negative,’ 11% ‘somewhat negative,’ 21% ‘somehow positive,’ 7% ‘very positive,’ 13% ‘no response’) (CISR, Citation2022). These dispositions—dependent at least partly on the meanings, beliefs, perceptions, and other sociocultural determinants examined above—could be consequential; if not in terms of impact on foreign policy, then at least in terms of domestic responses to it.

A year has passed since the beginning of the talks, and the process has not yet shown tangible results. Turkey has been insisting on Armenia’s agreement to Azerbaijani demands as a precondition for normalisation, a stance voiced more openly after a recent meeting between the two countries’ leaders (Tastekin, Citation2022). Turkey also voiced its support to Azerbaijan in September 2022 when the latter initiated a large-scale attack against Armenia resulting in hundreds killed and Armenian territories occupied (Broers, Citation2022; Reuters, Citation2022). A Turkish MP went so far, on that occasion, as to threaten ‘to erase Armenia from history and geography’ (Destici Citation2022). All this might well have further reinforced the meanings and attitudes examined above.

How would, on the other hand, a potential normalisation impact the perception and meanings of Turkey/Turks in Armenia? How would the recently ignited sensibilities and rigidified boundaries play out if social encounters were enabled with a possible eventual opening of the border? How would the ‘expansive potential’ of the border (Houtum, Kramsch & Zierhofer, Citation2005, p. 4), that of ‘mediating contacts’ (Paasi, Citation1998, p. 80), manifest itself? How would open borders impact the geo-awareness of people on the two sides of the boundary? These and other questions would come forth. Meanwhile, flames remain unquenched on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border as well as in Karabakh (Bloomberg, Citation2022), and the conflict has been spiralling again with the recent Azerbaijani blockade of the Lachin corridor linking Nagorno-Karabakh to the outside world (Gavin, Citation2023).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Esra Özyürek and Kevork Oskanian for providing feedback at different stages of this work, Lori Allen for her editorial assistance, and Rik Adriaans for his comments on the initial research proposal.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Pseudonyms are used for interlocutors.

2 Turkey and Azerbaijan denied the deployment of mercenaries (Butler, Citation2020).

3 Although Turkey sided with Azerbaijan during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war as well, its support then was largely limited to the diplomatic and economic spheres and its involvement was far from comparable to what it was in 2020 (Broers, Citation2021; Ter-Matevosyan, Citation2021; de Waal, Citation2021).

4 For a discussion of their experiences see Nikoghosyan (Citation2017).

References

- 168.am. (2021, April 21). Ara Nikol, Tʻurkʻ, gna … restoranitsʻ durs yekogh Pʻashinyanin syunetsiʻnerě chanaparhetsʻin hayhoyanknerov. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cCvzBnaEhc.

- Abrahamian, L. (2006). Armenian identity in a changing world. Mazda Press.

- ACNIS. (2005). The Armenian genocide: 90 years and waiting. Armenian Center for National and International Studies.

- Adjemian, B., & Davidian, V. K. (2021). Scholarship and introspection in the time of War. Études Arméniennes Contemporaines, 13, 255–257.

- Adriaans, R. (2017). Dances with oligarchs: Performing the nation in Armenian civic activism. Caucasus Survey, 5(2), 142-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761199.2017.1309868

- Akpınar, A., Avetisyan, S., Balasanyan, H., Güllü, F., Kandolu, I., Karapetyan, M., Manasyan, N., Mkrtchyan, L., Özkaya, E., Özkaya, H., Palandjian, G., Şekeryan, A., & Turan, Ö. (2019). History education in schools in Turkey and Armenia:A critique and alternatives. Istanbul; Yerevan: History Foundation and Imagine Center for Conflict Transformation.

- Al Jazeera. (2020, December 10). Azerbaijan celebrates Nagorno-Karabakh victory, Erdogan attends. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/12/10/azerbaijan-celebrates-nagorno-karabakh-victory-erdogan-attends.

- Andrews, B. (1975). Social rules and the state as a social actor. World Politics, 27(4), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/2010013

- Armenian Public TV. (2021, November 23). HH Varch’apet Nikol Pashinyani Asulisě. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZ0i0AwmfEM.

- Armenian Second TV Channel. (2021, November 11). Tʻurkʻ-adrbejantsʻinerě Yerevani srtum hartsʻazruytsʻ en vertsʻnum nayev adrbejantsʻineritsʻ. Mariam Melkonyan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kt02QTulwQY.

- Armenpress. (2020a, July 27). Tʻurkʻian chi miana Adrbejanin Hayastani nkatmamb laynatsaval paterazmi sandzazertsman hartsʻum. Makuntsʻ. https://armenpress.am/arm/news/1023126.html.

- Armenpress. (2020b, September 28). Turkish F-16s back Azeri attack on Karabakh, Sarkissian says warning of Ottoman Empire's ghost. https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1029252.

- Armenpress. (2021, April 14). Tʻurkʻerě, adrbejantsʻinerě mer tʻshnamin en. Pʻashinyaně tesnum e tʻshnamankʻě karʻavarelu anhrazheshtutyun. https://armenpress.am/arm/news/1048985.html.

- Barnett, M. N. (1996). Identity and alliances in the Middle East. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Berger, T. U. (1996). Norms, identity, and national security in Germany and Japan. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Bloomberg. (2022, August 3). Three Die in New Clashes Between Azerbaijanis and Armenians. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-03/two-killed-in-new-clashes-between-azerbaijanis-and-armenians.

- Broers, L. (2021). Requiem for the unipolar moment in nagorny karabakh. Current History, 120(828), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.828.255

- Broers, L. (2022, September 26). Is Azerbaijan planning a long-term presence in Armenia? Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/09/azerbaijan-planning-long-term-presence-armenia.

- Butler, E. (2020, December 10). The Syrian mercenaries used as ‘cannon fodder’ in Nagorno-Karabakh. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-55238803.

- Casey, E. S. (1993). Getting back into place: Toward a renewed understanding of the place-world. Indiana University Press.

- Cheterian, V. (2020, December 15). The Day Symbols Paraded on the Streets of Baku. Agos. http://www.agos.com.tr/en/article/25041/the-day-symbols-paraded-on-the-streets-of-baku.

- Cheterian, V. (2022). Technological determinism or strategic advantage? Comparing the two karabakh wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Journal of Strategic Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2127093

- CISR. (2018). Public opinion survey: Residents of Armenia. October 9-29, 2018. International Republican Institute.

- CISR. (2021). Public opinion survey: Residents of Armenia. December 2021. International Republican Institute.

- CISR. (2022). Public opinion survey: Residents of Armenia. June 2022. International Republican Institute.

- Cookman, L. (2020, November 10). Armenians rage against last-minute peace deal. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/10/armenians-oppose-last-minute-peace-deal-azerbaijan-nagorno-karabakh/.

- CRRC-Armenia. (2015). Key Findings Based on the Public Opinion Survey Conducted Within the Support to the Armenia-Turkey Normalization Process Program. Yerevan, Armenia.

- Daily Sabah. [@DailySabah]. (2020, September 29). Twitter. https://twitter.com/DailySabah/status/1310886686059098113.

- Das, V. (1995). Critical events: An anthropological perspective on contemporary India. Oxford University Press.

- Davtyan-Gevorgyan, A. (2021, August 4). ‘Yes Tʻurkʻ chʻem’ kam ‘Tʻurkʻě du es’ kharʻnaghmukě. Aliq Media. https://www.aliqmedia.am/2021/08/04/24014/

- de Waal, T. (2021). The Nagorny Karabakh Conflict in its Fourth Decade. CEPS Working Document No. 2021-02, September.

- Destici, M. [@Mustafa_Destici]. (2022). Twitter. https://twitter.com/mustafa_destici/status/1570379659476619265.

- Dijkink, G. (1996). National identity and geopolitical visions: Maps of pride and pain. Routledge.

- Dudwick, N. C. (1994). Memory, Identity and Politics in Armenia. PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

- Feldhaus, A. (2003). Connected places: Region, pilgrimage, and geographical imagination in India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fifth TV. (2021, April 25). Yatʻaghanitsʻ bayraktar. Sharunakvogh tsʻeghaspanutʻyun. https://www.facebook.com/fifthTV/videos/465362574746175.

- Finnemore, M. (1996). National interests in international society. Cornell University Press.

- Fırat, D., Şannan, B., Muti, Ö, Gürpınar, Ö, & Özkaya, F. (2017). Postmemory of the Armenian genocide: A comparative study of the 4th generation in Armenia and Turkey. Oral History Forum D’histoire Orale, 37.

- Fraser, S. (2022, March 12). Turkey, Armenia agree to press ahead with mending fences. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-europe-mevlut-cavusoglu-middle-east-armenia-cacb4774a8df60371f54fb69034aa209.

- Gavin, G. (2023, January 18). The crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh highlights Russia’s waning global influence. Time. https://time.com/6247979/russia-nagorno-karabakh-humanitarian-crisis/.

- Ghaletchyan, N. (2021, May 4). MIP-ě hay gerinerin khostangelu tesarannerov tesanyutʻeri usumnasirutʻyuně kugharki mijazgayin karʻutsʻnerin’, Azatutyun. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31237355.html.

- Gould, P., & White, R. (1986). Mental maps. George Allen and Unwin Publishers. (Original work published 1974).

- Göksel, N. (2012). Turkey and Armenia post-protocols: Back to square One? Istanbul: TESEV.

- Hayeli Am. (2021a, September 19). Hraparakum hanrahavakě nkarahanogh Tʻurkiayi droshov dghamardik Tʻurkʻer ein. Marina Khachatryan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TGwdRej3lQ.

- Hayeli Am. (2021b, September 19). Tʻurkʻerě Yerevanum. Tsap tvekʻ, YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Dm8hgyyKNA.

- Hetq. (2020, September 28). Armenian Foreign Ministry: Turkish Military Experts are Fighting Alongside Azerbaijan. https://hetq.am/en/article/122092.

- Hill, F., Kirişçi, K., & Moffatt, A. (2015). Armenia and Turkey: From normalization to reconciliation. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 13(4), 127–138.

- Hopf, T. (1998). The promise of constructivism in international relations theory’. International Security, 23(1), 171–200. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.23.1.171

- Houtum, H., van Kramsch, O., & Zierhofer, W. (2005). Prologue: B/ordering space. In H. van Houtum, O. Kramsch, & W. Zierhofer (Eds.), B/ordering space. Ashgate Publishing Company.

- Hovyan, V. (2020). Artsʻakhyan paterazm. Rusakan ardzagankʻner. Orbeli Center, 14 October. https://tinyurl.com/mrbc6at3

- in TV. (2022, February 15). Kʻnnichʻ handznazhoghově kusumnasiri nayev 44-orya paterazmi ardakʻin hetkʻě. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBsvmZexBZ8&t=721s.

- Iravaban. (2021, September 19). Vostikanutyuně ‘Vosku ashkharhi’ dimatsʻitsʻ berman yentʻarkvats ‘Tʻurkʻeri’ masin. https://iravaban.net/350364.html?fbclid=IwAR1Am7hfw_ALxmBPi6vFLHhNW84pXUYb6lAoNWW07y2IZzzD96fP6-5xdWY.

- Jepperson, R. L., Wendt, A., & Katzenstein, P. J. (1996). Norms, identity, and culture in national security. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Johnston, A. I. (1996). Cultural realism and strategy in maoist China. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Katzenstein, P. J. (1996a). Introduction: Alternative perspectives on national security. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Katzenstein, P. J. (ed.). (1996b). The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Kenez, L. (2021, December 3). VP confirms Turkish intelligence was involved in Nagorno-Karabakh war, refuting long-denied claim. Nordic Monitor. https://nordicmonitor.com/2021/12/vice-president-confirms-turkish-intelligence-involved-in-nagorno-karabakh-war-refuting-long-denied-claim/.

- Kharatyan-Araqelyan, H. (2010). Research in Armenia: Whom to forgive? What to forgive? In L. Neyzi, & H. Kharatyan-Araqelyan (Eds.), Speaking to One another: Personal memories of the past in Armenia and Turkey. DVV International.

- Kowert, P., & Legro, J. (1996). Norms, identity, and their limits: A theoretical reprise. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security: Norms and identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

- Kucera, J. (2021, July 16). What’s the future of Azerbaijan’s ‘ancestral lands’ in Armenia? Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/whats-the-future-of-azerbaijans-ancestral-lands-in-armenia.

- Lapid, Y., & Kratochwil, F. (1996). The return of culture and identity in IR theory. Lynn Rienner Publishers.

- Leupold, D. (2020). Embattled dreamlands: The politics of contesting Armenian, kurdish and turkish memory. Routledge.

- Manukyan, G. (2021, December 14). Tʻurkʻerě kʻaghakʻum en. Yerkir. https://m.yerkir.am/news/view/256386.html.

- Martinez, O. (1994). The dynamics of border interaction: New approaches to border analysis. In C. H. Schofield (Ed.), Global boundaries, world boundaries, vol. 1. Routledge.

- Marutyan, H. (2009). Iconography of Armenian identity. Volume 1: The memory of genocide and the karabagh movement. Yerevan: Gitutyun Publishing House.

- News am. (2021a, March 27). Armen Grigoryani skandalayin haytararutʻyuně Tʻurkʻian tʻshnami petutʻyun hamarelu masin. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIpbgrOFpIE.

- News am. (2021b, September 19). Jinseri vra tʻurkʻagan droshov yeritasardner Hanrapetutyan hraparakum. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kix7pnyfmFA.

- News am. (2022, February 21). Ughigh: ‘Chʻenk tʻoghnelu estegh Tʻurkʻ mtni’. Paterazmi masnakitsʻner chanaparh en pʻakel. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAZvfSARRUQ.

- Newspress am. (2021, February 27). “Arantsʻ tʻurkʻi Hayastan”. Baghramyan poghotayum Pashinyani hrazharakani pahanjov hanrahavak. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MkrnAQhrLI.

- Nikoghosyan, A. (2017). Hayastani ‘tʻurkʻakan hamaynkě’. In G. Shagoyan (Ed.), Chʻlsvogh dzayner. Hishoghutyunn u hethishoghutyuně banavor patmutʻyunnerum. IAE Publishing.

- Ohanyan, A. (2007). On money and memory: Political economy of cross-border engagement on the politically divided Armenia-Turkey frontier, Conflict, Security & Development 7(4), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678800701692993

- Ó Tuathail, G. (1999). Understanding critical geopolitics: Geopolitics and risk society. Journal of Strategic Studies, 22(2-3), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402399908437756

- Paasi, A. (1998). Boundaries as social processes: Territoriality in the world of flows. Geopolitics, 3(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650049808407608

- Paasi, A. (2001). Europe as a social process and discourse. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640100800102

- Panorama.am. (2022, October 15). Shutov ěndameně 150.000 dollari timatsʻ Tʻurkerě kkaroghanan darʻnal HH Kʻghakʻatsʻi. Iravaban. https://rb.gy/hvycs4

- Parliamentary Assembly. (2021). Humanitarian consequences of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan / Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Resolution 2391, Council of Europe.

- Pashinyan, N. [@NikolPashinyan]. (2020, October 1). Twitter. https://twitter.com/nikolpashinyan/status/1311635330106351618.

- Republic of Armenia. (2020). National Security Strategy of the Republic of Armenia: Resilient Armenia in a Changing World. https://www.gov.am/en/National-Security-Strategy/.

- Reuters. (2022, September 13). Turkey backs Azerbaijan, says Armenia ‘should cease provocations’. https://www.reuters.com/world/turkeys-says-armenia-should-cease-provocations-with-azerbaijan-2022-09-13/.

- Ringmar, E. (1996). Identity, interest and action: A cultural explanation of Sweden’s intervention in the thirty years War. Cambridge University Press.

- Roth, A. (2020, December 15). Two men beheaded in videos from Nagorno-Karabakh identified. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/15/two-men-beheaded-in-videos-from-nagorno-karabakh-war-identified.

- Safrastyan, R. (2021, November 20). Tʻurkʻaget. ‘Merdzavor Arevelkʻn ir bolor khndirnerov nerkhuzhum e mer taratsashrjan’. Interview by Marine Martirosyan. Hetq. https://hetq.am/hy/article/138086.

- Seferian, N. (2017). The clash of turkish and Armenian narratives: The imperative for a comprehensive and nuanced public memory. Sabanci University.

- Soylu, G. (2020, December 11). Why Turkey returned to the Caucasus after a hundred years. Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-azerbaijan-armenia-caucasus-return-why.

- Stein, B. (1977). Circulation and the historical geography of tamil country. The Journal of Asian Studies, 37(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2053325

- Stronski, P. (2021, June 23). The Shifting Geography of the South Caucasus. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/23/shifting-geography-of-south-caucasus-pub-84814.

- Sukiasyan, L. (2022, January 21). Patuhanis tak gorʻum ein ‘Tʻurkʻ’, u du terʻoritsʻ es khosum, Gegham? Lusine Badalyan. Aravot. https://www.aravot.am/2022/01/21/1242678/.

- Tass. (2021, April 14). Pashinyan says about 4,000 Armenian troops killed in Nagorno-Karabakh. https://tass.com/world/1277921.

- Tastekin, F. (2022, October 11). Turkey's stance complicates potential peace between Armenia, Azerbaijan. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/10/turkeys-stance-complicates-potential-peace-between-armenia-azerbaijan#ixzz7iskO4FSu.

- Ter-Matevosyan, V. (2021). Deadlocked in history and geopolitics: Revisiting Armenia–Turkey relations. Digest of Middle East Studies, 30(3), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/dome.12242

- Tilly, C. (2004). Social boundary mechanisms. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 34(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393103262551

- TRT World. (2020, September 29). Turkey with Azerbaijan ‘in battlefield, on negotiation table’. https://www.trtworld.com/turkey/turkey-with-azerbaijan-in-battlefield-on-negotiation-table-40143.

- Turan. (2021, March 4). Famous general killed in helicopter crash in Turkey. https://www.turan.az/ext/news/2021/3/free/Worldwide/en/1932.htm

- UNHCR. (2020, November 11). Mercenaries in and around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone must be withdrawn – UN experts. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26494.

- Wendt, A. (1999). Social theory of international politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Wilson, A. (2005). Virtual politics: Faking democracy in the former soviet world. Yale University Press.

- Zolyan, M. and Zakaryan, T. (2008). The image of ‘self’ and ‘other’ in Armenian history textbooks. In L. Vesely (Ed.), Contemporary history textbooks in the south Caucasus, Prague: Association for International Affairs.