ABSTRACT

The debate regarding whether, in sub-Saharan Africa, exogenousFootnote1 and endogenous institutionsFootnote2 have witnessed significant changes to facilitate contemporary Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) processes remains inconclusive. Additionally, there is insufficient knowledge of their compliance levels. To address these lacunae, we used content analysis of policy documents, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and expert interviews to examine the evolution of FLR-linked exogenous and endogenous institutions and their compliance levels in rural Cameroon. Using thematic and content analyses hinged on a hybrid endogenous-cum-exogenous institutional analytical lens; we conclude that in Cameroon’s FLR context, exogenous institutions have transitioned from focusing solely on forest plantation establishment to encompass natural/artificial regeneration and agroforestry. More recent approaches have incorporated FLR financing mechanisms, capacity building, collaboration, and research. However, the significant exogenous institutional transformation does not necessarily imply higher compliance. Future studies should unravel actors’ interests and power dynamics that potentially shape compliance with institutions in FLR.

1. Introduction

The role of governance – actors’ decision-making and the institutional frameworks that enable or constrain the implementation of decisions (Giessen & Buttoud, Citation2014) – in natural resources management, especially forest landscape restorationFootnote3 (FLR), has attracted scientific and political attention in recent decades (Guariguata & Brancalion, Citation2014; Lamb & Gilmour, Citation2003; Mansourian, Citation2021). Although the ecological and technical factors, such as drivers of degraded or deforested landscapes, species to be used for the restoration, the kind of methods to adopt for FLR, etc., are very relevant considerations when planning FLR, they have proven to be insufficient in ensuring successful FLR outcomes (César et al., Citation2020; Mansourian, Citation2016; Sayer et al., Citation2013). However, governance issues in FLR are increasingly recognised as the critical factors determining the success or failure of FLR interventions (Guariguata & Brancalion, Citation2014; Mansourian, Citation2016; Urzedo et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the scientific literature, in recent decades, has paid more attention to the role and relevance of institutions and their dynamics within diverse forested landscapes (Osei-Tutu et al., Citation2015; Owusu et al., Citation2023).

Institutions are viewed as highly invisible and sometimes abstract conditions: that constitute cognitive, normative and regulatory structures that stabilise human behaviour (Scott, Citation2013). According to Ostrom (Citation1992), they are the rules entities employ to govern natural resources protection, conservation and use, ultimately impacting themselves and others. Put succinctly, in the context of FLR, institutions are the processes (e.g. rules, taboos, etc.) and the structures (e.g. forestry offices, community forest management groups, etc.) that shape human behaviour in FLR by acting as constraints or enablement (Fleetwood, Citation2008; Ostrom, Citation1990). The structure-process institutions appear to be inherently interconnected, as the processes (e.g. rules) define the composition of the structures (e.g. forestry offices), and the structures, in turn, (re)define rules and their enforcement and/or compliance mechanisms (Fleetwood, Citation2008).

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), for instance, the literature on forest management institutions has highlighted the importance of the functional and complementary roles of the formal and informal institutions in forest management (Kimengsi et al., Citation2022b; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., Citation2017). Also, the exogenous and endogenous formal and informal typologies of FLR-linked institutions and their link to FLR outcomes in SSA have been reported (Owusu et al., Citation2023). The literature also reports information on forest-linked institutional change (Haller et al., Citation2016). Moreover, the literature has captured reports on the role of effective institutions in influencing community participation in FLR where local community members, for instance, will only participate more in FLR activities when there is effective custom and/or policy linked to land tenure security (Lovo, Citation2016; Owusu et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, institutional arrangements have been reported to have produced injustices in rural Africa regarding who wins or losses in FLR (Elias et al., Citation2021; Kandel et al., Citation2021; Kariuki & Birner, Citation2021).

Despite the increasing body of literature on forest and FLR management institutions, the debate on whether or not exogenous and endogenous institutions have evolved to assume their place in shaping contemporary FLR remains inconclusive (Kimengsi et al., Citation2023b), especially in the context of SSA’s FLR, therefore suggesting the need for further evidence. Additionally, the scant literature on the compliance levels of the exogenous and endogenous typologies of FLR-linked institutions requires renewed evidence, especially in SSA – where there are seeming changing institutional arrangements as well as diverse social, demographic, ecological, economic, and political forces, of which those who are supposed to comply with the institutions likely deal with. Our general assumption is that the exogenous institutions that shape rural Cameroon’s FLR have evolved more than the endogenous institutions; however, the latter witnesses more compliance than the former. In this paper, we determined (i) the evolution of FLR-linked exogenous and endogenous institutions and (ii) their compliance levels in rural Cameroon’s FLR.

Cameroon has a multiplicity of endogenous cultural institutions (Kimengsi & Silberberger, Citation2023) due to its ethnic diversity (Fearon, Citation2003). Some of these cultural entities include the Abashi (Santchou landscape), Muankum (Bakosi landscape), and Manjong (Kilum Ijim landscape) (Kimengsi et al., Citation2022a). Also, several FLR-linked interventions are occurring in the country (MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020). Recently, the country has developed a national FLR strategic framework to push FLR interventions (ibid). These factors make Cameroon an appropriate ‘living laboratory’ to investigate the evolution and compliance levels of the exogenous and endogenous institutions that shape SSA’s FLR. Our study edifies the theoretical anchor on exogenous and endogenous institutional change (Koning, Citation2016) as well as the extent of compliance with exogenous and endogenous institutions (Greif, Citation2006; Shvetsova, Citation2003; Vallino, Citation2014) in the context of FLR. The study also provides concrete information to guide FLR interventions in Cameroon as the country works towards achieving the commitment of restoring over 12 million ha of its degraded or deforested landscape by 2030.

2. Methodology

2.1. Analytical framework

The study’s analytical framework is hinged on the exogenous and endogenous institutional analytical lens that frames institutions as a self-enforcing or externally enforced set of constraints or enablement mechanisms (Greif, Citation2006; Shvetsova, Citation2003; Vallino, Citation2014). In other words, in exogenous and endogenous institutionalism, institutions are typified as the outcomes of external and/or local-level political choices that regulate human behaviour (Shvetsova, Citation2003; Vallino, Citation2014). Although there are diverse levels of exogeneity and endogeneity, in this study, while endogenous refers to the local communities where the study was conducted, exogenous relates to anything outside the study communities (Owusu et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the institutions that shape natural resources use and management, and in this context, rural Cameroon’s FLR, have sources linked to exogenous (i.e. international, national, subnational) or endogenous (i.e. community designed institutions or daily practices and/or way of life of community members).

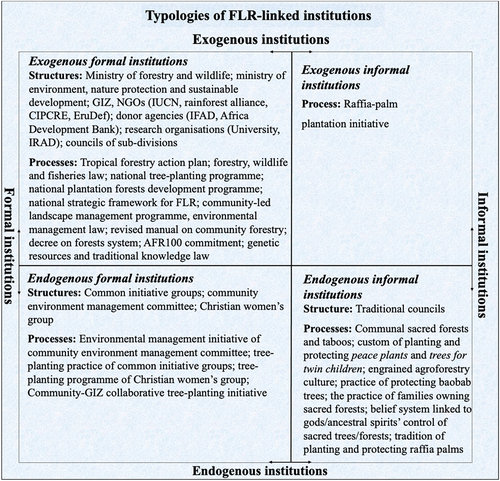

The exogenous and endogenous institutions in this study are viewed as behaviour-guiding processesFootnote4 (e.g. policies, taboos, etc.) and structuresFootnote5 (e.g. forestry departments, traditional councils, etc.) after Fleetwood (Citation2008). Exogenous and endogenous institutions (either structures or processes) have some formality, i.e. formal institutions – documented and standardised structures and processes mostly governed by national authorities or informal institutions – unwritten or uncodified practices, lack governments’ recognition and instead rely on unofficial agreements or expectations, sometimes enduring across generations (Yeboah-Assiamah et al., Citation2017). This, therefore, resulted in four typologies of institutions – exogenous formal, exogenous informal, endogenous formal, and endogenous informal institutions (). These typologies of institutions interact to shape resource management and use (in this case, FLR) (Owusu et al., Citation2023; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., Citation2019). Institutions are also subject to evolution over the years. The evolution of institutions can also influence the overall institutional environment ().

Figure 1. Analytical framework of the study [adapted from Koning (Citation2016), Orozco (Citation2019), Owusu et al. (Citation2023), Shvetsova (Citation2003), Vallino (Citation2014), and Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2017)].

![Figure 1. Analytical framework of the study [adapted from Koning (Citation2016), Orozco (Citation2019), Owusu et al. (Citation2023), Shvetsova (Citation2003), Vallino (Citation2014), and Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2017)].](/cms/asset/f1e75bad-5227-4ef3-8376-d6f57817cc63/tlus_a_2322602_f0001_oc.jpg)

In this study, evolution, which refers to the change in the institutional landscape, was framed differently for exogenous and endogenous-linked institutions. The evolution of exogenous institutions was framed as the transformation of institutional policy direction over time. On the other hand, the evolution of endogenous institutions was examined within the context of historical endogenous institutional frameworks, which consisted of endogenous FLR-linked institutions that influenced FLR activities in the past and the more recent endogenous institutional framework – endogenous FLR-linked institutions that have been shaping FLR practices, probably, within the last two decades. According to Koning (Citation2016), the evolution of either the endogenous or exogenous institutional landscape could be driven by either endogenous or exogenous factors. Endogenous institutional change occurs when the transformation is triggered by internal social structures or interactions involving actors within the institution (Koning, Citation2016). In contrast, exogenous institutional change arises when deliberate actions of external entities induce transformation, typically in response to factors outside the established institutions, such as the creation of new institutions or significant shifts in societal characteristics (ibid).

The evolution of institutions has the potential to influence compliance levels of institutions and vice versa. Additionally, due to the potentially different levels of implementation, enforcement, reverence and/or resistance to institutions, there is the potential for varying levels of adherence (i.e. non-compliance, partial or full compliance). In this study, we framed full compliance (+) as adherence or conforming to applicable laws or norms (institutions); partial compliance (±) was framed as partly adhering to institutions or a reduction in the intensity of enforcement/adherence; non-compliance (–) was framed as a non-adherence to tenets of institutions (Orozco, Citation2019).

2.2. Study area

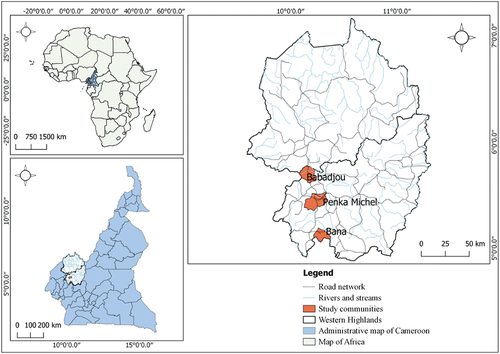

The study was conducted in Cameroon, a central African country located between latitudes 1°45″–13°00″ North and longitudes 8°24″–16°28″ East (McSweeney et al., Citation2008) (). Geographically, Cameroon displays five biophysically and climatically distinct agro-ecological zones – the Sudano-Sahelian zone, the Guinean High Savannah zone, Monomodal Rainfall Forests zone, Bimodal Rainfall Forests zone, the Western Highlands zone (MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020). Cameroon’s estimated forest cover is 20,340,480 ha, suggesting a loss of about 2,159,520 ha over the past two decades when the forest cover was estimated to be 22,500,000 ha (Kengoum Djiegni et al., Citation2016; MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020; World Bank, Citation2022). A recent assessment of the FLR needs of Cameroon revealed the Western Highlands as one of the areas in great need of FLR (Tunk et al., Citation2016).

The Western Highlands, the agro-ecological zone for the study, have similar social, economic, and political characteristics and span through an area of about 3,807,280 ha (38,072.8 km2) (Jiotsa et al., Citation2015; WWF, Citation2022). It is shaped by savannah vegetation, stepped plateaus, low basins and plains crossed by gallery forests (MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020). The area has an altitude range of 1000–2500 m above sea level (Jiotsa et al., Citation2015). Also, the ecoregion is one of Cameroon’s densely populated areas, with a population density of about 128.5 inhabitants per km2 (Mbile et al., Citation2019; MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020). Most of these inhabitants are rural dwellers that engage in agricultural activities; they mostly cultivate Irish potatoes, corn, beans, tomatoes, etc (Jiotsa et al., Citation2015; Mbile et al., Citation2019; MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020). The inhabitants also engage in livestock keeping (ibid). The traditional setting of communities in this ecoregion is highly centralised with well-structured hierarchical institutions (Jiotsa et al., Citation2015; Kimengsi & Silberberger, Citation2023). The endogenous institutional setting of the communities in the region epitomises a traditional African society where there is reverence for local traditions.

We, therefore, selected the Western Highlands of Cameroon as a suitable ‘living laboratory’ for our study because of (i) the well-structured institutional set-up, (ii) the area’s great need of FLR and (iii) the fact that FLR activities – establishment of tree seedlings, tree-planting, establishment, and protection of forest reserves and/or sacred forests, agroforestry, among others – are occurring in the landscape. Three rural communities (i.e. Bana, Babadjou, Penka Michel) were randomly selected from the area due to the area’s similar ecological, social, and economic characteristics (Jiotsa et al., Citation2015) ().

2.3. Data collection methods

This paper forms part of a study on the exogenous and endogenous institutional analysis of FLR processes in rural Cameroon. Using content analysis of policy documents, expert interviews, key informant interviews (KIIs), and focus group discussions (FGDs), we qualitatively explored the issues linked to the evolution and compliance levels of the exogenous and endogenous institutions that shape FLR in rural Cameroon. We employed multiple research strategies to aid in data triangulation. We reviewed 10 key documents linked to Cameroon’s forest and environment management () between May 2022 and April 2023 to identify the evolution of the policy instruments, objectives, and strategies that have shaped Cameroon’s FLR.

Field data collection occurred in the three rural communities of Cameroon’s Western Highlands between June and August 2022. Research instruments – KIIs guide with 10 questions, FGDs guide capturing eight questions, and experts interview guide made up of seven questions – aided in data collection (see supplementary material 1). Before data collection started, the research instruments, which had English and French versions, were reviewed by peers and pre-tested. Additionally, a research assistant was selected and trained to aid with data collection. Since data was collected in a predominantly French-speaking side of Cameroon, the research assistant selection criteria were linked to individuals who speak, read, and understand English and French and understand basic concepts in forestry. Subsequently, data collection commenced. Twenty-four KIIs were conducted in the study area, i.e. eight KIIs in each study community, capturing data from traditional leaders of the communities, relatively older men and women, and youth (). This was done to capture the perspective of almost all categories of people in the communities about the institutions that shape FLR in rural Cameroon, their evolution, and compliance levels, among others. In addition to the 10 key questions that guided the KIIs, several follow-up questions were asked to clarify the information provided by respondents or for further information based on the responses received. On average, KIIs lasted 35 minutes. Although the researcher took notes, all interviews and discussions during the study were recorded after obtaining the verbal consent of the respondents.

Also, using the FGD guide, 15 FGDs were conducted during the study. The first author asked follow-up questions during the discussions for clarification and further information. In each of the three study communities, FGDs were done with two mixed groups (composed of men, women, and youth), one men group, one women group and one youth group (). Aside from the Christian Women’s group that was already established to cater for its members’ welfare, all other groups were ad-hoc groups put together by the researchers – with memberships composed of communities’ individuals linked to natural resources (forest, land, etc.). FGDs were done to obtain the perspective of all groups or categories of people in the communities about the institutions that shape FLR, their evolution, and compliance levels, among others. On average, FGDs composed of about nine individuals lasted about 55 minutes.

Additionally, expert interviews were conducted to obtain experts’ perspectives on the exogenous and endogenous institutions that regulate rural Cameroon’s FLR. We interviewed one Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF) official, three Agricultural officials, one Ministry of Environment, Nature Protection and Sustainable Development official, three Sub-divisional Councils’ officials and one official of a Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) – CIPCRE. The expert interview guide guided the interaction with the experts. Like the KIIs and FGDs, follow-up questions were asked to get further and better information on the study subject. On average, expert interviews lasted about 40 minutes. During data collection, questions and responses were predominantly in French. However, the research assistant translated the conversations for the first author to understand. This allowed the first author to ask follow-up questions where necessary (in English but translated to the respondents in French). The first author, however, directly interacted with any respondent who understood English.

2.4. Data analyses methods

A review of key policy documents on Cameroon’s forest and environment was done using directed content analysis (Clay et al., Citation2015). We carefully studied the content of the documents linked to the Tropical Forestry Action Plan; Forest, Wildlife, and Fisheries Law; Decree on Forests System; Environmental Management Law; Manual on Community Forestry; National Tree-Planting Programme; AFR100 Commitment; National Plantation Forests Development Programme; National Strategic Framework for FLR; and Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge Law (supplementary material 2). Particular attention was paid to the statements, sections, articles, objectives, or strategies in the documents linked to FLR by searching for terms such as forest restoration, reforestation, afforestation, tree-planting, agroforestry, creating enclosures or enclosing areas, creation and protection of forest reserves, natural regeneration, assisted natural regeneration, and managed plantations. We subsequently extracted the statements, sections, articles, objectives, or strategies linked to FLR in Cameroon into a Microsoft Word document. We carefully read the Microsoft Word document to identify the trend and how the policies related to Cameron’s FLR had evolved over the years.

Regarding the data from the field, the audio recorded during data collection was transcribed into text (see supplementary material 3). Each interview in the transcript was coded. Directed content and thematic analyses were used to analyse the textual data (Clay et al., Citation2015). The authors carefully read the content of the transcribed data and extracted key information following pre-determined themes that corresponded to the specific objectives of this paper. Narratives were used to elaborate the themes. Qualitative analysis software was not employed to assist with the analysis because issues related to institutions are complex and sometimes not directly framed; hence, using software to help in the analysis might miss out on certain key data. Our analysis focused on identifying the exogenous and endogenous institutions that shape FLR in rural Cameroon and how they have evolved. Finally, we explored the compliance levels of the exogenous and endogenous institutions in rural Cameroon’s FLR. We evaluated the compliance levels of the institutions by thoroughly analysing the responses we received from our respondents. Institutions that exhibited complete adherence were placed in the ‘Full Compliance (+)’ category. Those institutions that displayed a decrease in enforcement or adherence were categorised under the ‘Partial Compliance (±)’ group. Lastly, institutions that exhibited no adherence whatsoever were classified as undergoing ‘Non-Compliance (–)’.

3. Results

3.1. FLR-linked institutions in rural Cameroon

Our research revealed that a plethora of institutions influence rural Cameroon’s Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR). Many of these institutions emerged in recent years as a response to international and regional environmental management efforts. The institutions were linked to exogenous formal, exogenous informal, endogenous formal, or endogenous informal institutional typologies. Among these typologies, the most dominant was the exogenous formal institution – signifying its prominence and significant impact on FLR initiatives, followed by endogenous informal and endogenous formal institutions – suggesting that both exhibit some influence in rural Cameroon’s FLR (). The exogenous informal institution emerged as the least dominant institutional typology, suggesting a relatively limited role in the FLR dynamics of rural Cameroon ().

3.2. Evolution of exogenous and endogenous FLR institutions

3.2.1. Exogenous institutions

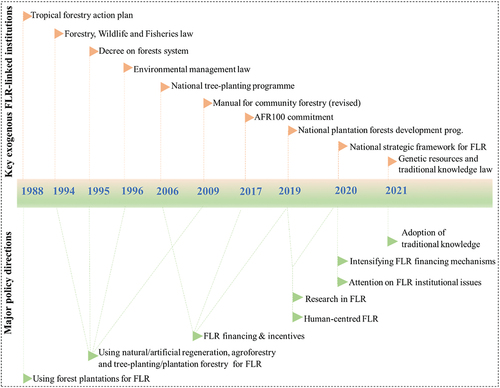

Over the years, the restoration of degraded forest landscapes in rural Cameroon has been shaped by key environmental management legislations (exogenous institutions) (). In the 1980s, the exogenous FLR-linked institutional landscape of Cameroon was made up of a narrow policy statement on the approach to restoring degraded forest landscapes. Subsequently, the institutional landscape kept evolving over the years, with the introduction of new policy provisions to complement what already existed, to the extent that recent years have witnessed relatively more detailed and pragmatic exogenous institutions that hope to improve FLR in the country. For instance, in the 1980s, forest restoration in Cameroon focused mainly on establishing forest plantations, as outlined in the 1988 Tropical Forestry Action Plan of Cameroon. However, the 1990s and 2000s saw significant advances in environmental regulations related to FLR. Notable regulations introduced include the 1994 Forest, Wildlife, and Fisheries Law, the 1995 Decree on Forests System, the 1996 Environmental Management Law, and the 2009 Manual on Community Forestry. In contrast to the 1988 Tropical Forestry Action Plan, these laws embraced a more holistic approach to FLR. While they continued to support the use of plantation forestry as the means of restoring degraded forest lands, they also recognised and emphasised the importance of natural/artificial forest regeneration and agroforestry (refer to Appendix A).

Figure 5. Evolution of key exogenous institutions and major policy directions linked to Cameroon’s FLR.

From the mid-2000s, in a bid to promote FLR, the introduced exogenous institutions such as the 2006 National Tree-Planting Programme, the 2017 AFR100 commitment, and the 2019 National Plantation Forests Development Programme promoted the economic aspects of FLR (i.e. financing of FLR interventions by the State and use of incentive measures in FLR) (Appendix A). The 2019 National Plantation Forests Development Programme and the 2020 National Strategic Framework for FLR complemented existing legislation by emphasising the human factors of FLR or the human-centred FLR. They introduced regulations linked to actors’ capacity building, collaboration, and research in FLR (Appendix A). Additionally, the 2020 National Strategic Framework for FLR paid more attention to the intensification of the financing mechanisms of FLR as well as FLR institutional issues (such as land use policies conducive to FLR, the contribution of ministries in FLR, etc.) (Appendix A) – explained, probably, by the recent global attention on FLR governance as well as the economic and ecological outcomes of FLR.

In 2021, Cameroon enacted the Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge Law that emphasises the valorisation of genetic resources and traditional knowledge – rooted in customs, traditions, norms, etc., of the local communities of Cameroon. This seemingly complements the 2020 National Strategic Framework for FLR regarding FLR institutions and actors. The law indirectly supports FLR by enhancing livelihoods and landscape regeneration since it can make people less dependent on the landscape. However, the lack of the law’s full link to the restoration of degraded landscapes makes the role of traditional knowledge and practices in FLR more deficient. It is, therefore, imperative for future environmental institutions in Cameroon to integrate local customs to ensure effective FLR.

3.2.2. Endogenous institutions

Our study’s evidence indicates that, across the study communities, there is a unanimous acknowledgement of the need to intensify the restoration of degraded landscapes due to the effects of the environmental changes they witness as a result of forest loss and/or tree cover change. Our findings indicate that the restoration of degraded landscapes in rural Cameron has historically been influenced primarily by endogenous informal institutions. These include the traditional councils, taboos linked to sacred forests/trees, deeply engrained agroforestry culture, etc. (see ). However, in recent times, more endogenous formal institutions, such as the community environmental management committee, faith-based groups like the Christian women’s group, and common initiative groups, have taken on a more prominent role in shaping FLR in rural Cameroon. Additionally, endogenously organised groups that are funded by international development agencies, such as the ‘Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit’ (GIZ), actively contribute to forest restoration efforts ().

Table 1. Evolution of endogenous institutions linked to FLR in rural Cameroon.

The variation in endogenous formal institutions across the study communities is evident. While common initiative groups exist across the communities, others are specific to study communities (). For instance, in Penka Michel, the community environmental management committee and Christian women’s group influence forest restoration efforts. In contrast, in the Babadjou community, an endogenously organised group funded by the GIZ has taken up the responsibility of tree-planting to restore degraded forest landscapes.

3.3. Compliance levels of exogenous and endogenous institutional typologies

summarises the results on compliance with FLR-related institutions in the study communities. The study revealed that across the study areas, while the exogenous formal and informal FLR-linked institutions are modestly adhered to, there is a high level of full compliance with the endogenous informal and formal FLR-related institutions that were recorded in the various study communities.

Table 2. Typologies of FLR-related institutions and their compliance levels.

From the evidence of the study, there are, so far, more violations of the exogenous formal FLR-related institutions than full compliance, and close to 50% of the recorded provisions or regulations are partially adhered to (). Concerning full compliance with exogenous formal institutions, our study revealed that there is full compliance with a provision of the 1994 Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries law that authorises or allows people to plant and own private forests. During the study, it was reported that some individuals in the communities restore degraded landscapes by planting and owning a few to several thousand hectares of plantation forests. Mostly, these forest owners restrict unauthorised access to their plantation forests (see Appendix B). Non-compliance or partial compliance with exogenous formal institutions, on the other hand, are linked to regulations such as, among others, (i) adopting land use policies and laws conducive to FLR, (ii) sanctions for engaging in illegal logging or destroying planted trees, (iii) obtaining authorisation before cutting poles or trees, and (iv) ensuring the inclusion of all social categories in FLR programmes.

Regarding the regulation, adopting land use policies and laws conducive to FLR, the evidence from the study shows that no new land use system conducive to FLR has been adopted to help impact FLR activities. The land use policy of the 1970s is still valid. From this policy, the government of Cameroon owns all lands and gives land titles to people. Obtaining a land title remains difficult even in recent. Some respondents (both experts and community members) expressed frustration over inadequate land ownership titles issued by the State to local community members. Consequently, individuals interested in FLR activities encounter challenges claiming ownership of sufficient land for agricultural and tree-planting purposes (see Appendix B).

Also, concerning the non-compliance with the provisions such as getting authorisation before cutting poles/trees and sanctioning people who engage in illegal logging or destruction of planted trees, a forest officer reported of their (forestry officials) inability to enforce the law to punish people who deliberately put impediments on the restoration processes by sometimes destroying planted trees (see Appendix B). At the community level, there was evidence of poor enforcement and adherence to the provisions. It was reported that some forestry officials do selective enforcement of the provision regarding the acquisition of authorisation prior to cutting poles/trees. Additionally, at times, they get easily influenced by some community members, sometimes leading to laxity in law enforcement regarding tree harvesting (Appendix B).

Furthermore, our study revealed the existence of the Community-led Landscape Management (COBALAM) programme in the Babadjou and Bana communities. According to the General Secretary of the Council of Babadjou sub-division, COBALAM is an FLR programme that aims to replant trees in all the degraded areas of Mount Bamboutos. It involves several communities and actors. While it is expected that this FLR initiative will promote the involvement of all social groups in FLR, the responses from community members during our research present a contrasting perspective. Field evidence suggests the need for an effective collaboration between the traditional council, the local community members and the State departments and agencies as a better way to ensure effective FLR (Appendix B). This presupposes non-compliance with the policy objective of ensuring the inclusion of all social categories in FLR.

With respect to the compliance level of the exogenous informal institutions, our study revealed partial compliance. Though Raffia palm planting and protection is one of the customs of the people of the Western Highlands of Cameroon, the delegates of MINFOF are informally leveraging on this custom in what is referred to as the Raffia-palm plantation initiative in the quest to restore the landscape. MINFOF officials engage in informal discussions and train community members on the protection, growth, and management of Raffia palms (see Appendix B). While some community members show interest in participating, others are less enthusiastic about the initiative (see Appendix B). An official from MINFOF expressed concern about the level of adherence to the initiative (see Appendix B), suggesting that this exogenous informal institution is partially complied with.

Our study shows that all the endogenous formal FLR-linked institutions in rural Cameroon seemingly witnessed full adherence (). For instance, the tree-planting programme of the Christian women’s group is complied with. Field evidence indicates that Christian women’s group members actively engage in a tree-planting programme due to the admonishment of tree-planting by their church (see Appendix B).

For the endogenous informal institutions, there is a remarkably higher degree of full compliance. All but one of the recorded endogenous informal institutions are fully adhered to (). Interestingly, even the younger generation (youths) in the communities know about the environmental-related endogenous informal institutions and reported that adherence to them has not changed over the years (see Appendix B). Also, it was reported that many people in the communities put their traditions first before any other religion (Christianity or Islam). Hence, their reverence for traditional customary practices has been almost constant over the years (Appendix B). The reverence for the customs related to the environment and, by extension, FLR is related to the communities’ belief system linked to gods/ancestral spirits’ control of sacred trees/forests. The people in the communities believe that, unlike the national laws where they can disobey and still manoeuvre their ways in such a way that they might not be caught to face punishment, a breach of the traditions and customs of the community (either overtly or covertly) will result in a tragedy on the perpetrator and/or his family (Appendix B).

4. Discussion

4.1. Institutional arrangements that shape FLR activities in rural Cameroon

Our study revealed that a diverse range of endogenous and exogenous (formal, informal) institutions shape FLR in rural Cameroon. The study’s result could be attributed to the combined impact of recent global political commitments, policy strategies, etc., linked to FLR (Bonn Challenge, Citation2020; MINFOF - MINEPDED, Citation2020), the daily practices and beliefs systems of local communities, and the activities of community-based groups in shaping FLR in rural Cameroon. The institutional diversity underscores the complex institutional landscape surrounding rural Cameroon’s FLR, suggesting the need to consider the existing institutional context when planning or designing FLR intervention to ensure effective outcomes. Additionally, the involvement of endogenous institutions, mostly rooted in local traditions and culture, highlights the importance of involving local communities in FLR interventions. Engaging with endogenous institutions and leveraging their values and social networks can enhance the success and possible sustainability of FLR efforts.

Furthermore, the dominance of exogenous formal institutions in rural Cameroon’s FLR suggests the significant role external entities (international, national, and sub-national) play in pushing FLR. Hence, effective collaboration between the exogenous and endogenous institutions (both formal and informal) with strong partnerships, expertise sharing, and alignment of goals and strategies is crucial to enhance the impact of the FLR initiatives and ensure effective FLR interventions. In all, the diversity of institutions shaping FLR highlights the importance of recognising and engaging with the diverse range of endogenous and exogenous institutions influencing FLR in rural communities of Cameroon to foster inclusive and sustainable FLR practices that align with local realities and contribute to long-term ecological functionality and community well-being. Our findings align with the research of Mansourian et al. (Citation2022), which highlights the role of various factors, such as tenure rights and collaborative arrangements between external agencies and local authorities, in effectively facilitating FLR efforts. However, our results differ from the findings of research in the Seno Plains of Mali that reported on the important role played by only the national forestry regulation in facilitating farmer-managed natural regeneration (Reij & Garrity, Citation2016).

4.2. FLR-related institutional dynamics in rural Cameroon

Our study revealed that the key exogenous institutions linked to Cameroon’s FLR evolved from a narrow-based policy direction to relatively broad policy objectives and strategies in recent times. This could probably be due to the country’s increasing efforts to find the optimal legal framework with greater potential to enhance the efficacy of FLR initiatives. The recent global attention on FLR governance and the notable economic and ecological benefits of FLR efforts likely drive this heightened focus. The evolution of the exogenous FLR-related institutional landscape of Cameroon rightly links to the mainstream literature on exogenous institutional change, where evolution is caused through the purposive actions of entities due to the situations outside the developed institutions, such as the formation of different institutions and/or large-scale changes in societies’ characteristics (Koning, Citation2016).

Additionally, with the recent focus on FLR governance (actors and institutions) in Cameroon, the law on traditional knowledge and practices in genetic resource management and use was enacted. However, the traditional knowledge and practices’ full link to restoring the existing degraded forest landscapes seems missing in the law. Although it is commendable that traditional knowledge and techniques have been acknowledged in the national legal framework, that alone is insufficient. However, the law should have elaborated on how traditional knowledge and practices have the potential to be fully valorised in environmental management and to ensure effective FLR. Therefore, future exogenous institutions (laws, regulations, policies, etc.) related to the environment and FLR in Cameroon should emphasise the valorisation of traditional knowledge and practices embedded in local customs, norms, and traditions. This potentially can ensure successful FLR when the potentials of these endogenous institutions are harnessed in FLR processes. This assertion was made against the background that for local communities to own and participate more to ensure sustainable development, efforts must be made to incorporate indigenous institutions in the formal development process (Kendie & Guri, Citation2007).

Regarding the evolution of endogenous institutions, the study reveals that in addition to endogenous informal institutions that traditionally shape FLR in rural Cameroon, recent times have witnessed the emergence of endogenous formal institutions that influence FLR in rural Cameroon. The integration of these relatively newer endogenous institutions suggests that as the landscape and societal dynamics change in rural Cameroon, resulting in excessive landscape degradation, endogenous institutions in rural Cameroon have adapted to new circumstances. The traditional institutions (endogenous informal ones) have incorporated elements from newer institutions and/or have established new mechanisms to meet the community’s evolving needs. This interestingly suggests that the endogenous FLR-related institutional landscape of rural Cameroon links clearly with the mainstream literature on exogenous institutional change, where evolution is triggered by the intentional actions of entities (Koning, Citation2016). However, the influence of this evolution on the success or otherwise of the entire FLR in rural Cameroon is currently not too clear. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of these institutions and change is crucial for effective FLR, requiring future research to unravel. Furthermore, conducting additional studies in various locations is essential to gain deeper insights into whether the recent transformation of the endogenous institutional landscape is more closely linked to exogenous institutional changes.

4.3. FLR-related institutional compliance in rural Cameroon

Based on our study, we found that the compliance levels of institutional typologies in rural FLR are notably different. While there is a higher degree of full compliance with endogenous institutions – all but one of the endogenous institutions were fully complied with, the exogenous institutional typologies demonstrate only modest adherence. The results shed light on the intriguing dynamics of compliance with institutions within the context of FLR efforts in the Western Highlands of Cameroon. The observed disparities in compliance levels bring a nuanced understanding of how local communities and exogenous entities engage with and respond to different institutional frameworks in the context of FLR.

In addition, the pronounced adherence to endogenous institutions underscores the profound influence of local norms, traditions, and established community processes on FLR interventions. Our results can be attributed to rural communities’ absolute reverence for their culture, closely linked to their belief system in their ancestral worship and/or gods. Therefore, when FLR initiatives align with these endogenous systems, they could tap into a reservoir of trust, familiarity and reverence that encourages higher levels of compliance. This result corroborates Kimengsi and Silberberger (Citation2023) who held that the actors driving exogenous institutions in the context of climate adaptation in rural Cameroon should accommodate endogenous cultural institutional arrangements and vice versa. Our study is also consistent with the findings from rural communities in Uganda where there was higher compliance with endogenous regulations (Nkonya et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, notwithstanding the remarkably pronounced adherence to the endogenous institutions, the only recorded endogenous institution (the tradition of planting and protecting raffia palms) that exhibits a distinct characteristic of partial compliance cannot be underestimated. It, however, signals a need for future research to unravel the underlying factors contributing to this unique pattern of behaviour and the potential solution if we want to sustain the pronounced nature of full compliance with endogenous institutions, especially in the context of FLR in rural communities in the Western Highlands of Cameroon.

While this result holds for the Western Highlands, it cannot be extrapolated for the different agro-ecological and socio-cultural contexts of Cameroon, where variations in the compliance levels of endogenous informal institutions are expected. This is linked to the ethnic diversity of Cameroon – about 250 ethnic groups (Fearon, Citation2003), implying significant variations in the endogenous cultural institutions which, either enhance or constrain compliance (Nuesiri, Citation2012). For instance, in Northern Cameroon, the religious and cultural specificities enhance compliance with endogenous cultural institutions (Haller, Citation2010). However, in the Greater South region, significant variations in compliance with endogenous cultural institutions are observed (Kimengsi et al., Citation2023a). Also, while strong centralised chieftaincy systems shape communities in the Western regions of Cameroon, the people in the East and Southern part of Cameroon (e.g. the Maka people), have an acephalous society where chieftaincy is not very centralised (Nuesiri, Citation2012). Hence, variations in compliance with endogenous cultural practices in these diverse societies are observed. Additionally, while the Marabouts of Senegal, who enjoy customary authority and legitimacy in the eyes of the local people, were able to exert much autocratic control over their subjects during the colonial era, the warrant chiefs of Eastern Nigeria faced a lot of resistance when they tried to exercise control over their subjects (Adegbulu, Citation2011; Nuesiri, Citation2012). Therefore, the findings from this landscape (Western Highlands) cannot be used to represent the whole of Cameroon and SSA. It is imperative for additional studies to be conducted in other parts of the region to assist in providing a holistic picture of the compliance level of endogenous FLR-related institutions in SSA.

On the other hand, the relatively lower compliance associated with exogenous institutional typologies could be due to their misalignment with local values and/or the lapses in the enforcement process. These limitations are often rooted in the inadequate commitment and self-interest of certain officials within agencies responsible for enforcing these institutions. Unfortunately, some officials prioritise their interests over the collective interests of the State and tend to bend the rules. There is, therefore, the need to improve the enforcement mechanisms of the exogenous FLR-related institutions and their integration with the existing endogenous systems. This integration would leverage the influence of endogenous institutions to boost the acceptance and success of exogenous FLR-related institutions in rural communities’ FLR interventions. Furthermore, our findings underscore the necessity for strategies that bridge the gap between global and national FLR objectives and the realities in local communities. Our result is similar to other studies where non-compliance with exogenous institutions was reported (Acheampong et al., Citation2016; Mupangwa et al., Citation2017). Our result was, however, different from the findings of Acquaah et al. (Citation2023), where there was an increase in compliance with both formal and informal forest management institutions during the COVID-19 outbreak in rural Uganda. Our results were also inconsistent with other studies that reported relatively high compliance with exogenous formal institutions (Fischer et al., Citation2014; Hersi & Kangalawe, Citation2016).

5. Conclusion

The governance of FLR has become a subject of growing interest among scientists and policymakers. Our study used the endogenous-exogenous institutional analytical lens to analyse (i) the evolution of FLR-linked exogenous and endogenous institutions and (ii) their compliance levels in rural Cameroon’s FLR to contribute to the growing knowledge on FLR governance, especially in SSA. We conclude that in the context of FLR in rural Cameroon, exogenous institutions have significantly evolved to assume their place in shaping contemporary FLR more than endogenous ones. However, the higher transformation of exogenous institutions does not necessarily imply higher compliance. In contrast, there is enduring adherence to endogenous institutions pointing to a deeper connection between local communities and their customs.

In addition, the transition of the exogenous FLR-related institutional typology from a narrow focus on forest plantation to a comprehensive approach encompassing diverse strategies signifies a noteworthy progression in Cameroon’s environmental management efforts. Including natural and artificial regeneration, agroforestry, collaborative financing mechanisms, capacity building, and research within the institutional framework demonstrates a commitment to sustainable and holistic FLR. Concurrently, the evolution of the endogenous institutions, characterised by the emergence of formal institutions alongside existing informal ones, underscores the dynamic nature of endogenous systems in shaping FLR activities in rural Cameroon. However, integrating traditional knowledge and practices into the FLR-related institutional landscape remains incomplete. Future FLR-linked policies in Cameroon should prioritise recognising and valorising traditional knowledge and practices rooted in local customs, norms, and traditions to ensure a truly comprehensive and culturally sensitive approach to FLR.

Moreover, both the exogenous and endogenous FLR-related institutional landscapes of Cameroon have undergone exogenous institutional change. Hence, this study helps edify the theoretical anchor on exogenous institutional change in the context of FLR. Future studies are, however, required to determine the factors that account for the less significant evolution of endogenous institutions in rural Cameroon’s FLR.

Finally, the cultural reverence for traditional norms and practices enhanced the full compliance with the endogenous institutions in rural Cameroon’s FLR. Therefore, FLR interventions or initiatives such as AFR100, among others, should align with or build upon existing endogenous institutions and tap into the well-established familiarity and cultural resonance underpinning the endogenous systems to enhance their legitimacy and increase the likelihood of success. This study enlightens the theoretical anchor on the variations in compliance with different forms of institutions (exogenous, endogenous, formal or informal) in the context of FLR. We recommend that future studies unravel FLR actors’ interests and the power dynamics in FLR that potentially shape compliance with institutions and, by extension, the effectiveness of institutions.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (248.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Gadinga Walter Forje and Mr. Russel Ngoh Tita, for their assistance during the data collection. We also thank all the respondents that provided responses to our study questions.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2024.2322602

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Exogenous institutions are the structures or processes (institutions) designed outside the community of their implementation or influence (e.g. forest restoration policy, forestry office, etc.).

2. Endogenous institutions are community-designed institutions or community members’ daily practices and/or ways of life that regulate human behaviour (e.g. traditional councils, customs, norms, etc.).

3. Forest landscape restoration is a ‘planned process that aims to regain the ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded forest landscapes’ (Lamb & Gilmour, Citation2003, p. 14) – It is manifested through diverse processes like agroforestry, new tree-plantings, managed natural regeneration, or improved land management to accommodate a mosaic of land uses such as agriculture, managed plantations, riverside plantings and protected biodiversity reserves (IUCN, Citation2022).

4. Institutions (processes) are the rules that define the enforcement mechanisms, and the composition and functioning of organisations/structures (Fleetwood, Citation2008).

5. Institutions (structures) are the organisations or agencies that (re)define rules and enforcement mechanisms (ibid).

References

- Acheampong, E., Insaidoo, T.F., & Ros-Tonen, M.A. (2016). Management of Ghana’s modified taungya system: Challenges and strategies for improvement. Agroforestry Systems, 90(4), 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-016-9946-7

- Acquaah, G., Kimengsi, J.N., & Were, A.N. (2023). Response of forest management institutions to health-related shocks. Learning from the busitema forest reserve of Uganda during the COVID-19 outbreak. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 32(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2023.2212701

- Adegbulu, F. (2011). From warrant chiefs to Ezeship: A distortion of traditional institutions in Igboland. Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences, 2(2.2), 1–25.

- Bonn Challenge. (2020). Current pledges. Retrieved may 20, 2022, from https://www.bonnchallenge.org/pledges

- César, R.G., Belei, L., Badari, C.G., Viani, R.A., Gutierrez, V., Chazdon, R.L. & Morsello, C. (2020). Forest and landscape restoration: A review emphasizing principles, concepts, and practices. Land, 10(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010028

- Clay, L., Hay-Smith, E.J.C., Treharne, G.J., & Milosavljevic, S. (2015). Unrealistic optimism, fatalism, and risk-taking in New Zealand farmers’ descriptions of quad-bike incidents: A directed qualitative content analysis. Journal of Agromedicine, 20(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2014.976727

- Elias, M., Joshi, D., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2021). Restoration for whom, by whom? A feminist political ecology of restoration. Ecological Restoration, 39(1–2), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3368/er.39.1-2.3

- Fearon, J.D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024419522867

- Fischer, A., Wakjira, D.T., Weldesemaet, Y.T., & Ashenafi, Z.T. (2014). On the interplay of actors in the co-management of natural resources–A dynamic perspective. World Development, 64, 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.026

- Fleetwood, S. (2008). Structure, institution, agency, habit and reflexive deliberation. Journal of Institutional Economics, 4(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137408000957

- Giessen, L., & Buttoud, G. (2014). Assessing forest governance-analytical concepts and their application. Forest Policy and Economics, 49, 1–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.11.009

- Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy: Lessons from medieval trade. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Guariguata, M. R., & Brancalion, P. H. (2014). Current challenges and perspectives for governing forest restoration. Forests, 5(12), 3022–3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5123022

- Haller, T. (Ed.). (2010). Disputing the floodplains: Institutional change and the politics of resource management in African floodplains. Leiden: Brill.

- Haller, T., Acciaioli, G., & Rist, S. (2016). Constitutionality: Conditions for crafting local ownership of institution-building processes. Society & Natural Resources, 29(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1041661

- Hersi, N.A., & Kangalawe, R.Y. (2016). Implication of participatory forest management on duru-haitemba and Ufiome forest reserves and community livelihoods. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment, 8(8), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE2015.0550

- IUCN. (2022). Forest landscape restoration. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.iucn.org/theme/forests/our-work/forest-landscape-restoration#:~:text=FLR%20manifests%20through%20different%20processes,plantations%2C%20riverside%20plantings%20and%20more

- Jiotsa, A., Okia, T.M., & Yambene, H. (2015). Cooperative movements in the western highlands of Cameroon. Constraints and adaptation strategies. Journal of Alpine Research| Revue de géographie alpine, 103(103–1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.2764

- Kandel, M., Agaba, G., Alare, R.S., Addoah, T., & Schreckenberg, K. (2021). Assessing social equity in farmer-managed natural regeneration (fmnr) interventions: Findings from Ghana. Ecological Restoration, 39(1–2), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.3368/er.39.1-2.64

- Kariuki, J., & Birner, R. (2021). Exploring gender equity in ecological restoration: The case of a market-based program in Kenya. Ecological Restoration, 39(1–2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.3368/er.39.1-2.77

- Kendie, S.B., & Guri, B. (2007). Indigenous institutions, governance and development: Community mobilization and natural resources management in Ghana. Compas Series on Worldviews and Sciences, 6, 332–349. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237480383

- Kengoum Djiegni, F., Assembe-Mvondo, S., Eba’a Atyi, R., Levanga, P., & Fomété, T. (2016). Cameroon’s forest policy within the overall national land use framework: From sectorial approaches to global coherence? International Forestry Review, 18(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554816819683762

- Kimengsi, J.N., Abam, C.E., & Forje, G.W. (2022a). Spatio-temporal analysis of the ‘last vestiges’ of endogenous cultural institutions: Implications for Cameroon’s protected areas. Geo Journal, 87(6), 4617–4634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10517-z

- Kimengsi, J.N., Mairomi, H.W., Forje, G.W., Kometa, R.N., & Abam, C.E. (2023a). Power and conviction dynamics on land and linked natural resources: Explorative insights from the greater south region of Cameroon. Geo Journal, 88(5), 4625–4643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10884-9

- Kimengsi, J.N., Owusu, R., Charmakar, S., Manu, G., & Giessen, L. (2023b). A global systematic review of forest management institutions: Towards a new research agenda. Landscape Ecology, 38(2), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-022-01577-8

- Kimengsi, J.N., Owusu, R., Djenontin, I.N., Pretzsch, J., Giessen, L., Buchenrieder, G. & Acosta, A.N. (2022b). What do we (not) know on forest management institutions in sub-saharan Africa? A regional comparative review. Land Use Policy, 114, 105931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105931

- Kimengsi, J.N., & Silberberger, M. (2023). How endogenous cultural institutions may (not) shape farmers’ climate adaptation practices: Learning from rural Cameroon. Society & Natural Resources, 36(5), 460–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2175283

- Koning, E.A. (2016). The three institutionalisms and institutional dynamics: Understanding endogenous and exogenous change. Journal of Public Policy, 36(4), 639–664. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X15000240

- Lamb, D., & Gilmour, D. (2003). Rehabilitation and restoration of degraded forests. Cambridge, UK: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK in collaboration with WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- Lovo, S. (2016). Tenure insecurity and investment in soil conservation. Evidence from Malawi. World Development, 78, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.023

- Mansourian, S. (2016). Understanding the relationship between governance and forest landscape restoration. Conservation and Society, 14(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.186830

- Mansourian, S. (2021). From landscape ecology to forest landscape restoration. Landscape Ecology, 36(8), 2443–2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01175-6

- Mansourian, S., Kleymann, H., Passardi, V., Winter, S., Derkyi, M.A.A., Diederichsen, A. & Kull, C.A. (2022). Governments commit to forest restoration, but what does it take to restore forests? Environmental Conservation, 49(4), 206–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892922000340

- Mbile, P.N., Atangana, A., & Mbenda, R. (2019). Women and landscape restoration: A preliminary assessment of women-led restoration activities in Cameroon. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 21(6), 2891–2911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0165-4

- McSweeney, C., New, M., & Lizcano, G. (2008). UNDP climate change country profiles: Cameroon. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://www.geog.ox.ac.uk/research/climate/projects/undp-cp/UNDP_reports/Cameroon/Cameroon.lowres.report.pdf

- MINFOF - MINEPDED. (2020). Restoration of degraded forests and landscapes in Cameroon: National strategic framework. Yaounde, Cameroon: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Mupangwa, W., Mutenje, M., Thierfelder, C., & Nyagumbo, I. (2017). Are conservation agriculture (CA) systems productive and profitable options for smallholder farmers in different agro-ecoregions of Zimbabwe? Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 32(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170516000041

- Nkonya, E., Pender, J., & Kato, E. (2008). Who knows, who cares? The determinants of enactment, awareness, and compliance with community natural resource management regulations in Uganda. Environment and Development Economics, 13(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X0700407X

- Nuesiri, E.O. (2012) The Re-emergence of Customary Authority and its Relation with Local Democratic Government. In Responsive Forest Governance Initiative (RFGI) Working Paper No. 6 (pp. 1–74). Darkar, Senegal: CODESRIA.

- Orozco, D. (2019). A systems theory of compliance law. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law, 22(2), 244–302.

- Osei-Tutu, P., Pregernig, M., & Pokorny, B. (2015). Interactions between formal and informal institutions in community, private and state forest contexts in Ghana. Forest Policy and Economics, 54, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.01.006

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. New York: Cambridge university press.

- Ostrom, E. (1992). Crafting institutions for self-governing irrigation systems. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies Press.

- Owusu, R., Kimengsi, J.N., & Giessen, L. (2023). Outcomes of forest landscape restoration shaped by endogenous or exogenous actors and institutions? A systematic review on sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Management, 72(2), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01808-x

- Owusu, R., Kimengsi, J.N., & Moyo, F. (2021). Community-based forest landscape restoration (FLR): Determinants and policy implications in Tanzania. Land Use Policy, 109, 105664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105664

- Reij, C., & Garrity, D. (2016). Scaling up farmer‐managed natural regeneration in Africa to restore degraded landscapes. Biotropica, 48(6), 834–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12390

- Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J.-L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E. & Garcia, C. (2013). Ten Principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(21), 8349–8356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210595110

- Scott, W.R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). California: Sage publications.

- Shvetsova, O. (2003). Endogenous selection of institutions and their exogenous effects. Constitutional Political Economy, 14(3), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024702528927

- Tunk, C., Hoefsloot, H., & Amougou, J. (2016). Evaluation du potentiel de restauration des paysages forestiers au Cameroun. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from http://www.foretcommunale-cameroun.org/download/documents/Rapport_final_%C3%A9tude_Restauration_Paysages_Forestiers.pdf

- Urzedo, D.I., Neilson, J., Fisher, R., & Junqueira, R.G. (2020). A global production network for ecosystem services: The emergent governance of landscape restoration in the Brazilian Amazon. Global Environmental Change, 61, 102059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102059

- Vallino, E. (2014). The tragedy of the park: An agent-based model of endogenous and exogenous institutions for forest management. Ecology and Society, 19(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06242-190135

- World Bank. (2022). Forest area (sq. km) - Cameroon. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.FRST.K2?locations=CM

- WWF. (2022). Western Africa: Western Cameroon extending into Nigeria. Retrieved December 22, 2022, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0103

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Muller, K., & Domfeh, K.A. (2017). Institutional assessment in natural resource governance: A conceptual overview. Forest Policy and Economics, 74, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.10.006

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Muller, K., & Domfeh, K.A. (2019). Two sides of the same coin: Formal and informal institutional synergy in a case study of wildlife governance in Ghana. Society & Natural Resources, 32(12), 1364–1382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1647320