?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

For local governments, inter-municipal cooperation (IMC) has become an increasingly common solution to tackle fiscal constraints and demographic challenges. However, in many policy areas, it is still not clear whether IMC fulfills its promises of cost savings or increased service quality. This study aims to contribute new knowledge on the effects of IMC in one of these understudied policy areas – education – and does so by employing recent developments in difference-in-differences methods. The results show that being part of IMC significantly reduces expenditures on upper secondary education. However, there are indications that decreased costs come at a price, since joining a local federation also correlates with lower grades in the cooperating municipalities.

Introduction

The phenomena of urbanization and population aging give rise to a seemingly intractable equation for numerous local governments worldwide. As the working population – and consequently the tax base – of these local governments shrinks, they are nevertheless obliged to maintain the provision of services for their citizens. These developments have spurred a wave of reforms in public service provision. Here, amalgamations of municipalities, where small units are merged to form larger ones, have been prevalent, creating what Blom-Hansen et al. (Citation2016, 812) refer to as “a global movement” driven by a pursuit of economies of scale. Another trend in local government reform, presumed to reduce costs, has been increased privatization and outsourcing of service delivery (Bel and Warner Citation2015). However, in recent years, inter-municipal cooperation (IMC) has become massively popular: the number of cooperations has increased rapidly in many European countries (Swianiewicz and Teles Citation2018), and IMC has even surpassed for-profit contracting in the United States (Warner, Aldag, and Kim Citation2021). Sweden, which is the focal point of this study, is also an integral part of this trend with a significant surge in the number of IMCs in recent decades (The Swedish Agency for Public Management Citation2023).

Obtaining cost savings is a key rationale for IMC. Through increased cooperation between municipalities, local governments are expected to exploit economies of scale and thereby lower costs (Bel and Sebő Citation2021). An upshot with IMC compared to amalgamations is that cost savings may be achieved without sacrificing local self-government, as the original municipal structure of small units can be retained (e.g. Blåka Citation2017). Furthermore, as opposed to privatization, IMC allows local governments to maintain greater control over production (Hefetz and Warner Citation2012).

However, despite the high expectations for the potential achievements of IMC, empirical evidence regarding its impact on costs remains inconclusive. To date, research has reported both lower and higher costs associated with IMC (Bel and Sebő Citation2021). Furthermore, although in recent years there has been a welcome increase in studies exploring new policy areas where IMCs operate (e.g. Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020), most studies have nevertheless been conducted on solid waste services, primarily due to challenges related to data accessibility (e.g. Bel and Warner Citation2015; Dijkgraaf and Gradus Citation2013). Thus, despite being widely applied, it remains uncertain whether IMC ultimately delivers its promises on cost savings – especially in areas where economies of scale are theoretically more difficult to achieve, which education policy would be an example of. In addition, there is little evidence of what happens to service quality if such cost savings take place. Against this backdrop, the purpose of the present study is to contribute to a better and more nuanced understanding of IMC. This is done by employing recent developments in difference-in-differences design (Callaway and Sant’anna Citation2021), on a panel data set of all Swedish municipalities from 1998 to 2021, and addressing the overarching research question: How does inter-municipal cooperation affect costs and service quality in Swedish upper secondary education?

The contribution of this study is two-fold: First, it examines a field that has not been the focus in previous literature on the effects of IMC – education. This represents a service that is inherently labor-intensive, making it a policy area that – at least in theory – is more challenging in which to achieve economies of scale compared to more technically oriented policy areas like solid waste services (Bel and Warner Citation2015). Furthermore, education is a policy area that requires many resources. Hence, if municipalities are able to lower costs in this sector, which in the case of Sweden makes up more than 40% of its budget (SALAR Citation2023), it is more advantageous economically than in other areas. Secondly, the study includes a measure of one aspect of service quality in education – grades – which gives us the opportunity to better understand if IMC affects the quality of the services provided. This is a perspective on the effects of IMC that tends to be lacking in empirical studies (Bel and Sebő Citation2021). Ultimately, the study demonstrates that IMC is associated with significant cost savings within this policy field. However, IMC and its cost savings seem to come with a price tag: lower grades.

IMC and cost savings: theoretical expectations

IMC is an umbrella term for a wide range of municipal cooperations: informal agreements, formal contracts between municipalities, joint bodies for governance, as well as the delegation of power and resources to supra-municipal bodies (Bel and Sebő Citation2021). Nonetheless, all these forms are expected to be a way for a municipality of a sub-optimal jurisdiction size to achieve economies of scale. This discussion on modifying the boundaries of local government by cooperation to achieve economies of scale dates back to at least the 1960s (Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren Citation1961).

Economies of scale refer to a decrease in average cost as production increases (Bel and Warner Citation2015). Through IMC, one municipality is expected to be able to provide larger volumes of a type of service to several municipalities, instead of producing it in fewer (costly) units by itself. In addition, underutilized and costly equipment and personnel can be shared between municipalities in IMC. This implies that IMC would be relatively more beneficial for smaller municipalities, as larger municipalities may already benefit from economies of scale.However, lowered costs are not conspicuous with IMC. In fact, there are a variety of reasons why IMC might not lead to cost reductions. If the goal of cooperation is not lowered costs, but rather coordination across the region and ensuring or improving quality of service, it may not be surprising that IMC ultimately increases costs (Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020). But even if the explicit goal of cooperation is cost reduction, it may not materialize. One reason is that IMC runs the risk of giving rise to collective action problems. The joint good and collective interests of all parties involved in the IMC might clash with the interests of individual municipalities, leading to sub-optimal outcomes for the new jurisdiction. Mitigating such collective action problems may involve significant transaction costs, including those related to monitoring and regulating the cooperation (Voorn, Genugten, and Thiel Citation2019). Other examples of potential transaction costs associated with IMC are those associated with information and coordination, negotiation and division, as well as bargaining (Feiock Citation2007). These types of transaction costs are anticipated to be greater in more formalized cooperation models, such as inter-municipal bodies which have been delegated authority over a policy area, compared to cooperation through, for instance, a contractual agreement. Furthermore, transaction costs are expected to be higher for cooperation that involves many municipalities (Blåka Citation2017; Tavares and Feiock Citation2018).

In addition, some types of policy services may be more conducive to IMC than others. For instance, labor-intensive and consumer-oriented services – such as health inspectors – are not expected to generate economies of scale because an increased volume of service requires a correspondingly larger number of employees (Dollery and Fleming Citation2006). Conversely, capital-intensive services with asset-specific elements – meaning services that require specific physical infrastructure or technical knowledge – have higher potential for achieving cost advantages through IMC (Bel and Sebő Citation2021). An example of this would be sewage disposal or domestic water supply (Dollery and Fleming Citation2006).

Empirical evidence on IMC and cost savingsFootnote1

Although academic publications on the subject have increased dramatically in recent years, the relationship between IMC and cost remains unclear in several policy areas. One exception is waste collection, which is the policy area on which most studies have been conducted. Here, several studies find evidence for cost savings through IMC (e.g. Pérez-López, Prior, and Zafra-Gómez Citation2018; Soukopová and Vaceková Citation2018).

However, when studies expand to other services, the evidence becomes more mixed. Ferraresi, Migali, and Rizzo (Citation2018) find that joining a supra-municipal body significantly reduces costs without affecting service quality, measured as the per-capita primary school class size, in Italy. However, a study expanding to more regions in Italy finds no trace of such efficiency gains (Luca and Modrego Citation2021). Similarly, Frère, Leprince, and Paty’s (Citation2014) study of IMC in France fails to find evidence of IMC reducing overall spending for the participating municipalities.

In other cases, the effects of IMC on cost vary depending on the size of the municipality. This is one of the conclusions in a recent meta-regression analysis by Bel and Sebő (Citation2021), which find that small populations seem to offer cost advantages to cooperating municipalities. Examples of specific policy areas where this relationship between population size and cost savings have been found include waste water policy in Germany (Blaeschke and Haug Citation2018) and tax collection in the Netherlands (Niaounakis and Blank Citation2017). Allers and de Greef (Citation2018) also confirm reductions in costs of tax collection through IMC in the Netherlands, but they observe a slight increase in overall municipal spending as an effect of IMC for small and large municipalities. Another study that finds specific effects related to the size of the municipalities is Tricaud’s (Citation2021) study on coerced IMC in France, where she shows that IMC results in 20 to 30% fewer daycare spots and public libraries for residents in rural municipalities.

Another strand of results suggest that the effects on cost may vary depending on the form of IMC. Holmgren and Weinholt (Citation2016) find no consistent cost effects in Swedish fire services when IMC forms are not differentiated. However, in the Norwegian context, IMC in fire services seems to reduce costs for contractual agreements, albeit with diminishing cost benefits as the number of cooperating partners increases. When IMC takes the form of a joint organization, no cost benefits can be identified, most likely due to heightened transaction costs associated with these cooperative structures (Blåka Citation2017). This pattern can be discerned in other studies. For instance, when studying jointly owned Norwegian municipal companies in waste collection, Sørensen (Citation2007) find that more municipal owners increase fees and costs.

The sole multivariate empirical study thus far to examine the impact of cooperation on costs over time in the United States, scrutinizing the effect on costs for 12 distinct services, concludes that “cost savings are heavily dependent on the characteristics of each service” (Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020, 285). It uncovers reduced costs for IMC associated with libraries, police, solid waste management, roads and highways, and sewer services. However, higher costs are found for elderly services, as well as for planning and zoning. No significant association is discerned between IMC and costs for five policy areas – fire, ambulance, water, youth recreation, and economic development. Nevertheless, for most services – even when costs decrease – economies of scale appear to be limited. The conclusion that the results of cooperation depend on the service field, as well as its organizational structure, has been echoed by several scholars (e.g. Bel and Sebő Citation2021; Blåka Citation2022).

While it can be concluded that IMC is not a panacea, the knowledge is still limited about when and where cost savings should be expected. Despite a surge in literature over the past decade (Bel and Sebő Citation2021), with more than 25 international publications in the field between 2013 and 2020 (Aldag, Warner, and Bel Citation2020), studies in each policy area remain scarce. This scarcity makes it challenging to form a comprehensive assessment for any policy domain, except for solid waste services. In addition, an array of different methods – with different ways of handling the bias which tends to be induced, since IMC in many countries is a voluntary project – have been used. Hence, more research in all policy fields and all countries is needed. This is particularly pronounced in policy areas that have not been the focus of multivariate empirical studies, such as education policy.

Context: IMC and upper secondary education in Sweden

Sweden stands out as one of the most decentralized countries in the world (Ladner et al. Citation2022). Each of its 290 municipalities shoulders the responsibility for extensive welfare services – including elderly care, social services, and education – which according to law are expected to be equal in quality irrespective of where you live. However, demographic conditions differ tremendously across the country, with municipal populations ranging from 2,350 to nearly 1 million inhabitants. This disparity has been accentuated over the past decades, where the smallest municipalities have experienced depopulation, whilst the largest municipalities continue to grow. As of 2022, 48 of the municipalities had fewer than 8,000 inhabitants. Already in the 1960s, this was a figure believed to be the lowest threshold for Swedish municipalities to be able to carry out their primary school operations efficiently (CitationSOU 1961:9). Hence, it may come as no surprise that many municipalities in Sweden experience financial stress and challenges in fulfilling their responsibilities, leading to extensive debates on the need for amalgamations and other public sector innovations (e.g. SOU Citation2020:8). Furthermore, Swedish municipalities have gone comparatively far with New Public Management reforms (e.g. Green‐Pedersen Citation2002), with contracting out being relatively common; approximately 17% of welfare servicesFootnote2 have been carried out by private providers in recent years (Statistics Sweden Citation2022).

Last, but not least, there has been a virtual explosion of IMC during the past decades, facilitated by both active encouragement and legislative adjustments from the central government, such as the introduction of joint committees in 1998 (Gossas Citation2006). The number of IMCs operating through a joint organization has gone from 34 in 1996 (CitationSOU 1996:137) to 207 in 2022,Footnote3 spanning various policy areas, including emergency services, administration, water and sewerage, elderly care, and energy (The Swedish Agency for Public Management Citation2023). It is worth noting that both entering and exiting these joint organizations is voluntary and does not come with any financial incentives – apart from the potential to achieve economies of scale – for joining or penalties for leaving. Generally, the organizations are initiated at the local government level, and typically, there is a separate joint organization for each policy area. Hence, every municipality can be part of several joint committees and/or local federations with different municipal partners.

The joint committee is part of one of its member municipalities’ existing organizations (the host municipality). It replaces the committees for this policy area for its member municipalities, which will instead be represented on the new joint committee. A local federation is thus not part of any existing municipal organization but creates a supra-municipal entity of its own that is granted authority from its member municipalities. Structurally, it resembles a regular municipality, with a council or a political executive board representing each municipal member. In the case analyzed here, the local federation takes over the formal responsibility, service provision, budget, and decision-making authority for the entire upper secondary education within its member municipalities. It is these local federations, demanding the highest level of commitment among IMC types in Sweden, that form the focal point of this study. During the years of this study, there have been no legislative changes pertaining to this particular form of IMC.

Turning to the policy area of interest, upper secondary education in Sweden, it should be noted that one of its main characteristics is the implementation of a voucher system. This system encourages parents and students to choose freely between schools, creating an environment that is permeated by both cooperation and competition between municipalities. According to Swedish legislation (CitationSFS 2010:800), the municipality is mandated to offer a “versatile selection of national programs”, either within the municipality itself or through IMC with other municipalities. This has led to approximately 95% of the municipalities engaging in IMC through contractual agreements (CitationSOU 2020:33) and, as of 2021, 35% of the students attended schools in a municipality where they did not reside.

The schools can be either public schools (managed by the municipalities) or private schools (which are run by either for-profit businesses or non-profit organizations). Almost a third of students attend private schools (National Agency for Education Citation2023). However, regardless of the entity responsible for running the school, its funding is provided by the municipality (Larsson Taghizadeh and Adman Citation2022). As already described above, contractual agreements to increase the choice of schools for students are the most prevalent form of cooperation. However, several municipalities have chosen to cooperate through local federations.

The theoretical expectations for local federations in upper secondary education are not straightforward. On the one hand, there appear to be opportunities for achieving economies of scale in upper secondary education, involving larger class sizes and potential cost reductions through shared school facilities and support functions. On the other hand, upper secondary education is a relatively labor-intensive type of welfare service. A teacher can only manage a certain number of students in his/her class – although the exact number is not specified in Swedish legislation. In addition, by its very nature, it is a geographically bounded operation since the distance a student can commute is limited. Moreover, when IMC involves delegated authority and politically salient issues – as in this case – higher transaction costs are anticipated compared to many other IMC forms. This is because it may give rise to conflicting interests and necessitate extensive monitoring. Furthermore, it may well be that IMC in this policy area is not primarily driven by a quest for cost reduction. Other objectives may take precedence, negating any potential cost-saving benefits. For instance, cooperation might be driven by the need for regional coordination across municipal borders, or to enable the participating municipalities to provide certain types of education programs.

Data

This study uses panel data on all 290 Swedish municipalities from 1998 to 2021 to estimate the effect of joining a local federation in upper secondary education on municipal school costs and grades. Data on local federations in upper secondary education, the key independent variable, have been compiled from Statistics Sweden and the National Agency for Education.

The number of municipalities participating in a local federation for upper secondary education fluctuated between 20 and 32 during these years, peaking in 2010 when 32 municipalities (or 11% of all Swedish municipalities) were part of a local federation.Footnote4 In total, there were 15 active federations encompassing 44 participating municipalities during the period. Once in place, local federations tend to be robust. The median time spent in a local federation is 14 years in this sector during the period studied.

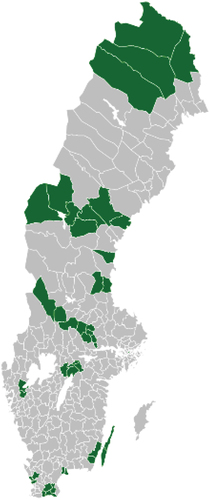

As depicted in , it is notable that all municipalities in local federations are neighbors, with just one exception. Additionally, the municipalities participating in local federations are present in all parts of Sweden and are not restricted to a certain type of municipality.

The study’s two dependent variables – expenditure on education and average grades – are also obtained from Statistics Sweden and the Swedish National Agency for Education. Expenditure on education is measured as the log expenditure on upper secondary education per student and year for each municipality, which includes all costs associated with education for the municipality. The average grade represents the mean grade across all subjects for students residing in a municipality, who graduate from an upper secondary school (within or outside the municipality).

The grading system in Sweden ranges from 0 to 20, with a score of 0 indicating failure and grades between 10 and 20 corresponding to varying levels of achievement. In this study, the average grade serves as a proxy for assessing the quality of education in the municipalities, under the assumption that improvements in education should lead to enhanced student performance. It is important to acknowledge that there has been noticeable grade inflation in Sweden over time (Henrekson and Wennström Citation2019). However, it is reasonable to assume that this inflation should, on average, be the same for municipalities within and outside local federations. Furthermore, one might argue that there are other variables more relevant in evaluating education quality, such as class size, student-teacher ratios, or the percentage of certified teachers. However, these aspects can only be measured in municipalities with their own upper secondary schools, and many municipalities in Sweden do not have such facilities.

The summary statistics for the municipalities included in the main analysis, (see in Appendix A), align with the anticipated trends: municipalities within a federation typically have smaller populations and lower population densities than municipalities outside local federations. Moreover, they tend to have a slightly smaller proportion of the population within the age group attending upper secondary education. However, they do not appear to exhibit greater financial distress than other municipalities. On average, they demonstrate similar levels of unemployment and a higher median income than municipalities not participating in a federation.Footnote5

Empirical strategy: addressing recent developments in difference-in-differences design

In its simplest form, a difference-in-differences design relies on two time periods and two different groups. In the initial period, neither of the groups undergoes treatment, while in the subsequent period, one group receives treatment. The difference between the groups can then be used to estimate the average effect on the treated population, under the assumption that both groups would have experienced parallel trends in the absence of treatment (Goodman-Bacon Citation2021). However, in practical applications, many researchers have modified this setup to analyze treatment effects in settings where treatment does not happen at one point in time for all treated units. They do this by employing two-way fixed effect (TWFE) models, i.e. linear regressions that incorporate period and group fixed effects.

The problem is that recent methodological developments in econometric theory have revealed that estimates with this widely popular research design are likely to be biased (e.g. de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Citation2020; Goodman-Bacon Citation2021; Imai and Song Kim Citation2021; Sun and Abraham Citation2021). When treatment effects remain constant over time, the TWFE estimator serves as a variance-weighted average of all possible two-group/two-period difference-in-differences estimators. However, in scenarios with heterogeneous treatment effects – meaning when treatment effect varies across time – some of these estimates are averaged with negative weights (Goodman-Bacon Citation2021). This is due to an issue of “forbidden” comparisons, where already-treated units or units that will become treated in the future act as controls (Roth et al. Citation2023), which in turn can cause significant estimates with the wrong sign (Baker, Larcker, and Wang Citation2022). In the case of local federations, it is likely that we are dealing with such heterogeneous treatment effects that may lead to biased results, as treatment does not happen at one point in time for all treated units. Hence, the study needs to take recent methodological advancements into account and employ an alternative design to the TWFE model.

Fortunately, a variety of studies have not only shed light on the limitations of TWFE models in cases where treatment is staggered (i.e. does not occur at a single point in time), but have also explored what methodological strategies to use instead (for an overview see Roth et al. Citation2023). One noteworthy contribution is the recent and widely cited paper by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021). In this study, their estimator – csdid – will be employed,Footnote6 which involves comparing pre-treatment trends with post-treatment changes, while accounting for the fact that municipalities joined local federations at different times. It also restricts the comparison group to municipalities that never entered a local federation, thus sidestepping the issue of negative weighting.Footnote7

Model specification

To take treatment heterogeneity into account, csdid estimates separate average treatment effects of the treated (ATT’s) for different cohorts of municipalities, depending on when they receive treatment. Thus, every municipality that first receives treatment in the same year belongs to the same group. These group-time average treatment effects are then aggregated to calculate the average total treatment effect across the full sample (Callaway and Sant’anna Citation2021).

Given the potentially significant disparities between municipalities that participate in a local federation and those that do not, a form of propensity score matching is implemented in the main specification. Thus, each group-time average treatment effect is based on a comparison with the post-treatment outcomes of the groups treated in a specific year against the never-treated groups that bear the closest resemblance (Huntington-Klein Citation2022).

Following the guidance of Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021), the approach based on propensity scores – which is based on inversed probability weighting (IPW) – is combined with an outcome regression. IPW relies on modelling the conditional probability of being in group g correctly, and the outcome regression relies on modelling the conditional expectation of the outcome evolution of the comparison group correctly. The advantage of this combined approach, known as the doubly robust approach, lies in the fact that only one of these needs to be correctly specified for the model to yield reliable results (Callaway and Sant’anna Citation2021). The group ATT by time is thus calculated through the following equation, using the doubly robust estimator:Footnote8

… where X refers to the independent variable (being part of a local federation) and covariates included in the analysis. These variables encompass demographic variables – the logarithm of the population, population density, and the proportion of people in the 16–19 age group – as the potential of achieving scale economies, which is one of the drivers for joining a local federation, should be greater for smaller municipalities. Additionally, the economic indicators median income and the percentage of employed individuals are incorporated, as financial constraints may drive municipalities to join a local federation. Three variables expected to influence school results are also included: the proportion of highly educated individuals, the proportion of foreign born, and the proportion of students in private schools. The first two serve as proxies for parents’ educational attainment and new immigrants among students, which are deemed important for explaining variation in school results in Sweden (National Agency for Education Citation2024). The third variable, the share of students in private schools, is included due to evidence suggesting that private schools may be more generous in grading (Hinnerich and Vlachos Citation2017). p, in the equation represents propensity scores derived from covariates expected to influence the likelihood of joining a local federation, which are the same covariates already mentioned. Since these covariates can change over time, they are assigned the value from the most recent year prior to treatment (Adhikari, Maas, and Trujillo-Barrera Citation2023). G is a binary variable equal to 1 if the municipality is first treated in period g, while C is a binary variable equal to 1 for municipalities in the control group, i.e. those in the never-treated group. Within the control group, observations with characteristics akin to those in group g are given higher weights, whereas observations with characteristics seldom found in group g are assigned lower weights (the other groups are omitted). This reweighting process is vital to ensure that the covariates of group g and the control group are balanced (Cunningham Citation2021). Y is the outcome, i.e. cost of school respectively grades, measured for the treatment or control in either the baseline (g-1) or some other period (t). The last component of the equation, denoted as m, is the population outcome regression for the never-treated group. In the final step, the many separate group-time average treatment effects (of joining a local federation on cost or grades), is aggregated into a summary causal effect measure, which accounts for effect heterogeneity related to treatment timing (Dettmann Citation2020). The estimation in this aggregation is weighted based on the number of observations in each group.

An underlying assumption of the model is that once a unit receives treatment, it will remain treated for the entire analyzed period (Callaway and Sant’anna Citation2021). However, given the possibility for municipalities to discontinue treatment in this context, this study estimates the aggregated effect of treatment for the initial seven years post-treatment. Footnote9 This approach allows for a larger pool of treated observations in the model, and it is reasonable to expect that any cost-saving effects should manifest within this timeframe.Footnote10 Furthermore, it is worth noting, following Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021), that units treated in the first year – the “always treated”-units – are excluded from the analysis. This is because untreated potential outcomes are never observed for this group, making it impossible to estimate treatment effects. Since the comparison group consists of never-treated units, the already-treated observations do not contribute to this aspect either. This means 20 municipalities already treated in 1998 are not a part of the main model.

Results

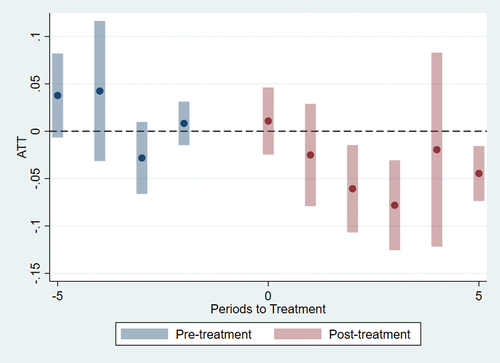

In this section, the findings derived from the difference-in-differences design (csdid), which accounts for staggered treatment timing and potential heterogeneous effects, are presented.Footnote11 Model 2 in displays results indicating that joining a local federation leads to a decrease in school costs. Specifically, municipalities that joined a local federation experienced, on average, a 4% reduction in costs over the first seven years after treatment compared to if they had not joined a local federation (p-value <0.05). Although the effect is not statistically significant immediately after joining a federation, it becomes significant within the first two years, with the highest cost savings observed two to three years after the year of joining.

Table 1. Aggregated and dynamic treatment effect estimates of being part of a local federation on costs and grades.

In the parsimonious model 1, where no covariates are included, the average effect for the first seven years after treatment is a slightly lower cost reduction of 3% compared to not being part of a federation (p-value <0.1). However, as detailed in the empirical strategy section, the estimations of model 2 should be more accurate. This is because observations in the control and treatment groups are weighted based on propensity scores, rendering them more comparable and leading to enhanced precision in estimates.

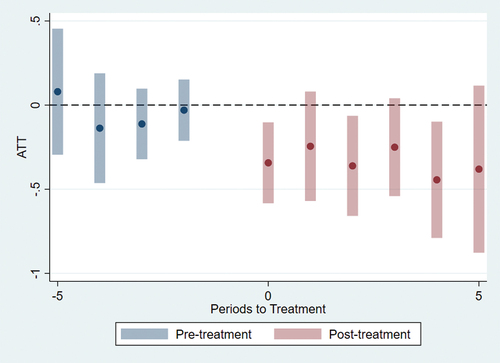

The results also indicate that the decision to join a local federation yields unintended consequences, particularly in terms of lowered grades. In model 4, the average total treatment effect reveals a decrease in grades by 0.4 grade points for the first seven years after joining a local federation (p-value <0.05). Notably, this effect is visible and significant from the year of joining a local federation. Moreover, the strongest average effect occurs in the fourth year after joining, with an estimated decrease in grades of 0.44 points compared to if the municipality had not joined a local federation. Model 3, without covariates and weighting based on propensity scores, exhibits similar trends, although the aggregated effect is slightly lower, indicating a decrease in grades by 0.2 grade points for the first seven years after joining a local federation.

The csdid model relies on pre-treatment parallel trends for estimates to hold true. In , this is explored through a graphical display of the main models of interest (models 2 and 4) from . As demonstrated in , the assumption seems to be met for costs, as there are no observable signs of treatment effects before the actual treatment occurs. Starting from the treatment year onwards, the coefficient exhibits a larger magnitude, and is significant in three out of the first five years after treatment, whereas it does not hold significance in any years before treatment.

Figure 2. Impact of local federations on school expenditure by relative time to treatment, model with covariates.

Figure 3. Impact of local federations on grades by relative time to treatment, model with covariates.

suggests that the parallel trend assumption holds in the case of grades as well, as there are no signs of treatment effects before joining a local federation. Here, the average effect of treatment is more stable over time compared to the effects of IMC on school cost, with estimates being either significant or very close to significant for all years following treatment.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper has analyzed the effect of IMC on the cost of education and on grades. The study adds to the growing literature on the economic effects of IMC, while simultaneously contributing to the employment of recent developments in difference-in-differences design. Furthermore, it contributes to the more limited literature on the effects of IMC on service quality, by examining a previously understudied field of cooperation – the relatively labor-intensive policy area of education, a policy area that arguably also has a local character.

The results provide important insights. Ex ante, IMC in a labor-intensive operation that has an inherently local character, and in the form of a formal joint organization such as a local federation, constitutes a tough case to reap economies of scale. However, first, there indeed seem to be opportunities for economies of scale in upper secondary education. Joining a local federation resulted in an average reduction of 4% in the cost of upper secondary education over the initial seven years post-treatment compared to the counterfactual scenario of not joining. These results are statistically significant, both at the aggregated level and in four out of seven individual years following treatment. This has important implications since education represents an expensive policy area for local government.

Second, and contrary to what is sometimes suggested in the literature, the reduced costs imply that achieving economies of scale through a form of IMC predicted to involve significant transaction costs – a joint organization delegated authority over a welfare service – is indeed possible. Previous studies have indicated challenges in achieving economies of scale in such cooperative arrangements (e.g. Blåka Citation2017). The feasibility of cost reduction in this case may be explained by the relatively few municipalities involved in each local federation since, as suggested in previous studies, more members are associated with larger transaction costs. In addition, most of the local federations last for many years, implying a strong commitment and reciprocity among the cooperating partners, factors that are predicted to lower transaction costs as well. It is also possible that there are transaction costs not grasped by the models in this study. Future research should study and compare different forms of IMC in upper secondary education to determine whether the specific form of cooperation affects the potential for achieving economies of scale in this domain.

Third, the results have the potential to shed light on the relationship between cost and service quality in IMC. The analyses reveal a statistically significant effect of lower grades when municipalities join a local federation, a trend that remains stable over time. On average, joining a local federation is associated with a decrease of 0.4 grade points for the first seven years after joining compared to the scenario of not joining a federation. This outcome is likely not what municipalities intended when delegating authority to a local federation and has significant implications for students, as grades influence their prospects for future university attendance.

It is important to note that while lower grades may suggest decreased service quality, grades serve as a proxy measure, and further research is necessary to unravel the underlying mechanism behind the results. One possible explanation, aside from diminished education quality, could be if IMC leads to more school closures, with less accurate grading schools being more prone to closure. Additionally, given the teacher shortage in Sweden, where a considerable portion of school staff lack teaching certification, the impact on grades may stem from an increased proportion of certified teachers within the local federation. It is plausible that certified teachers would assign more precise grades, albeit potentially lower, compared to those without formal teaching qualifications.

Nevertheless, given this potential negative effect linked to IMC, policymakers should exercise caution when establishing local federations in upper secondary education. In light of this concern, and considering the substantial rise in the prevalence of IMC worldwide, further research is warranted to explore the relationship between IMC and service quality.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for comments by Richard Öhrvall, Gissur Ó Erlingsson, Bo Persson, Emanuel Wittberg, and Eva Mörk, as well as conference attendees at the conference of the Swedish Political Science Association 2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author KS, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This section is focused on multivariate empirical studies that analyze the cost-saving effects of IMC. It is largely based on the literature reviews in Bel and Sebő (Citation2021) and Aldag, Warner, and Bel (Citation2020).

2. This includes education, health care, elderly care, and social services.

3. There are no data for the two other types of IMC in Sweden: contractual agreements between municipalities, where one municipality delegates a specific task to another municipality, and inter-municipal corporations.

4. This development over time is displayed in in Appendix A.

5. A full list of variables, definitions, and sources used in the study can be found in in Appendix A.

6. This is done by implementing the package csdid (Rios-Avila, Sant’anna, and Callaway Citation2021) in Stata.

7. In Appendix B, the TWFE model is also implemented to showcase potential differences in results between the new and old differences-in-differences methods, as well as to discuss potential explanations for why these differences may occur.

8. This doubly robust estimator, as described by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021, 205–206), has been performed using the command dripw.

9. In addition to the aggregated effect for the first seven years after treatment and the average treatment effects by the length of exposure to treatment displayed in of the results section, the group-specific and calendar time effects are reported in Appendix C

10. There are two local federations (which include four municipalities in total) that only lasted for three and four years respectively. Therefore, the municipalities in these local federations are dropped from the main model. However, if included the estimates for the first three years of treatment show almost identical results across models. These results are available upon request.

11. In Appendix D, a placebo test is displayed, where the outcome instead is something that should not be affected by joining a local federation – the cost of emergency services.

12. It should be noted that the municipalities already part of a local federation in 1998 are not part of the main model, as they are “always treated”. Additionally, two local federations, encompassing four municipalities in total, lasted only three and four years, respectively. Consequently, the municipalities in these local federations are excluded from the main model. Nevertheless, when included, the estimates for the first three years of treatment show almost identical results across models.

13. However, it should be noted that Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021) determine the appeal of the aggregations of calendar effects to be limited, as the interpretation is complicated (see discussion on page 211).

14. It should be noted that the municipalities that were already part of a local federation in 1998 are not part of the main model, as they are “always treated” (see the reasoning behind this on page 18). Furthermore, there are two local federations (which include four municipalities in total) that only lasted for three and four years respectively. Therefore, the municipalities in these local federations are dropped from the main model. However, if included the estimates for the first three years of treatment show almost identical results across models.

References

- SFS 2010:800. Skollagen.

- Adhikari, K., A. Maas, and A. Trujillo-Barrera. 2023. “Revisiting the Effect of Recreational Marijuana on Traffic Fatalities.” International Journal of Drug Policy 115 (May): 104000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104000.

- Aldag, A. M., M. E. Warner, and G. Bel. 2020. “It Depends on What You Share: The Elusive Cost Savings from Service Sharing.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (2): 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz023.

- Allers, M. A., and J. A. de Greef. 2018. “Intermunicipal Cooperation, Public Spending and Service Levels.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1380630.

- Baker, A. C., D. F. Larcker, and C. C. Y. Wang. 2022. “How Much Should We Trust Staggered Difference-In-Differences Estimates?” Journal of Financial Economics 144 (2): 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2022.01.004.

- Bel, G., and M. Sebő. 2021. “Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Really Reduce Delivery Costs? An Empirical Evaluation of the Role of Scale Economies, Transaction Costs, and Governance Arrangements.” Urban Affairs Review 57 (1): 153–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419839492.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2015. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence.” Public Administration 93 (1): 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12104.

- Blaeschke, F., and P. Haug. 2018. “Does Intermunicipal Cooperation Increase Efficiency? A Conditional Metafrontier Approach for the Hessian Wastewater Sector.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1395741.

- Blom-Hansen, J., K. Houlberg, S. Serritzlew, and D. Treisman. 2016. “Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation.” American Political Science Review 110 (4): 812–831. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000320.

- Blåka, S. 2017. “Does Cooperation Affect Service Delivery Costs? Evidence from Fire Services in Norway.” Public Administration 95 (4): 1092–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12356.

- Blåka, S. 2022. “Cooperation Is No Panacea: Inter-Municipal Cooperation, Service Delivery, and the Optimum Scale of Operation A Study of How Cooperation Affects Performance in Local Service Delivery.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Agder. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24124.92804.

- Callaway, B., and P. H. C. Sant’anna. 2021. “Difference-In-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.

- Chaisemartin, C. D., and X. D’Haultfœuille. 2020. “Two-Way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects.” American Economic Review 110 (9): 2964–2996. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181169.

- Cunningham, S. 2021. Causal Inference: The Mixtape. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dettmann, E. 2020. “Flexpaneldid: A Stata Toolbox for Causal Analysis with Varying Treatment Time and Duration.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3692458.

- Dijkgraaf, E., and R. H. J. M. Gradus. 2013. “Cost Advantage Cooperations Larger Than Private Waste Collectors.” Applied Economics Letters 20 (7): 702–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2012.732682.

- Dollery, B., and E. Fleming. 2006. “A Conceptual Note on Scale Economies, Size Economies and Scope Economies in Australian Local Government.” Urban Policy and Research 24 (2): 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111140600704111.

- Feiock, R. C. 2007. “Rational Choice and Regional Governance.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29 (1): 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00322.x.

- Ferraresi, M., G. Migali, and L. Rizzo. 2018. “Does Intermunicipal Cooperation Promote Efficiency Gains? Evidence from Italian Municipal Unions.” Journal of Regional Science 58 (5): 1017–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12388.

- Frère Q, Leprince M and Paty S. (2014). The Impact of Intermunicipal Cooperation on Local Public Spending. Urban Studies, 51(8), 1741–1760. 10.1177/0042098013499080

- Goodman-Bacon, A. 2021. “Difference-In-Differences with Variation in Treatment Timing.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 254–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014.

- Gossas, M. 2006. “Kommunal samverkan och statlig nätverksstyrning.” Doctoral Dissertation, Örebro University.

- Green‐Pedersen, C. 2002. “New Public Management Reforms of the Danish and Swedish Welfare States: The Role of Different Social Democratic Responses.” Governance-An International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions 15 (2): 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00188.

- Hefetz, A., and M. E. Warner. 2012. “Contracting or Public Delivery? The Importance of Service, Market, and Management Characteristics.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (2): 289–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur006.

- Henrekson, M., and J. Wennström. 2019. “‘Post-Truth’ Schooling and Marketized Education: Explaining the Decline in Sweden’s School Quality.” Journal of Institutional Economics 15 (5): 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174413741900016X.

- Hinnerich, B. T., and J. Vlachos. 2017. “The Impact of Upper-Secondary Voucher School Attendance on Student Achievement. Swedish Evidence Using External and Internal Evaluations.” Labour Economics 47 (August): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.03.009.

- Holmgren, J., and Å. Weinholt. 2016. “The Influence of Organisational Changes on Cost Efficiency in Fire and Rescue Services.” International Journal of Emergency Management 12 (4): 343. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEM.2016.079848.

- Huntington-Klein, N. 2022. The Effect: An Introduction to Research Design and Causality. First. Boca Raton London New York: A Chapman & Hall Book CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003226055.

- Imai, K., and I. Song Kim. 2021. “On the Use of Two-Way Fixed Effects Regression Models for Causal Inference with Panel Data.” Political Analysis 29 (3): 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2020.33.

- Ladner, A., N. Keuffer, A. Bastianen, and I. Bačlija Brajnik. 2022. Self-Rule Index for Local Authorities in the EU, Council of Europe and OECD Countries, 1990-2020. 1st ed. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Luca, D., and F. Modrego. 2021. “Stronger Together? Assessing the Causal Effect of Inter‐Municipal Cooperation on the Efficiency of Small Italian Municipalities.” Journal of Regional Science 61 (1): 261–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12509.

- Luca, D., and F. Modrego. 2024. “SALSA - En statistisk modell.” 2024. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/salsa-statistisk-modell.

- National Agency for Education. 2023. “Elever på program redovisade efter typ av huvudman och kön 2022/23.” https://siris.skolverket.se/siris/sitevision_doc.getFile?p_id=551885.

- Niaounakis, T., and J. Blank. 2017. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation, Economies of Scale and Cost Efficiency: An Application of Stochastic Frontier Analysis to Dutch Municipal Tax Departments.” Local Government Studies 43 (4): 533–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1322958.

- Ostrom, V., C. M. Tiebout, and R. Warren. 1961. “The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry.” American Political Science Review 55 (4): 831–842. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952530.

- Pérez-López, G., D. Prior, and J. L. Zafra-Gómez. 2018. “Temporal Scale Efficiency in DEA Panel Data Estimations. An Application to the Solid Waste Disposal Service in Spain.” Omega 76 (April): 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2017.03.005.

- Rios-Avila, F., P. H. C. Sant’anna, and B. Callaway. 2021. CSDID: Stata Module for the Estimation of Difference-In-Difference Model with Multiple Time Periods. Statistical Software Components S4588976 Boston College Department of Economics.

- Roth, J., P. H. C. Sant’anna, A. Bilinski, and J. Poe. 2023. “What’s Trending in Difference-In-Differences? A Synthesis of the Recent Econometrics Literature.” Journal of Econometrics 235 (2): 2218–2244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2023.03.008.

- SALAR (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions). 2023. “Så mycket kostar skolan.” https://skr.se/skr/skolakulturfritid/forskolagrundochgymnasieskolakomvux/vagledningsvarpavanligafragor/samycketkostarskolan.2785.html.

- SOU 2020:8 (Governmental Inquiry). Starkare kommuner – med kapacitet att klara välfärdsuppdraget.

- SOU 1961:9 (Government Inquiry). Principer för en ny kommunindelning.

- SOU 1996:137 (Government Inquiry). Kommunalförbund och gemensam nämnd - två former för kommunal samverkan.

- SOU 2020:33 (Governmental Inquiry). Gemensamt ansvar: en modell för planering och dimensionering av gymnasial utbildning.

- Soukopová, J., and G. Vaceková. 2018. “Internal Factors of Intermunicipal Cooperation: What Matters Most and Why?” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1395739.

- Statistics Sweden. 2022. “Privata företag utförde 17 procent av verksamheten inom vård, skola och omsorg 2020.” https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/offentlig-ekonomi/finanser-for-den-kommunala-sektorn/finansiarer-och-utforare-inom-varden-skolan-och-omsorgen/pong/statistiknyhet/finansiarer-och-utforare-inom-vard-skola-och-omsorg-20202/.

- Sun, L., and S. Abraham. 2021. “Estimating Dynamic Treatment Effects in Event Studies with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006.

- The Swedish Agency for Public Management. 2023. Hand i hand – en analys av kommunal samverkan. Stockholm: Statskontoret. https://www.statskontoret.se/siteassets/rapporter-pdf/2023/2023_5-utskriftsversion.pdf.

- Swianiewicz, P., and F. Teles, eds.20182018. Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe: Institutions and Governance, 1st. Palgrave Macmillan: Governance and Public Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62819-6.

- Sørensen, R. J. 2007. “Does Dispersed Public Ownership Impair Efficiency? The Case of Refuse Collection in Norway.” Public Administration 85 (4): 1045–1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00681.x.

- Taghizadeh, J. L., and P. Adman. 2022. “Discrimination in Marketized Welfare Services: A Field Experiment on Swedish Schools”. Journal of Social Policy.1–31. December. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279422000940.

- Tavares, A. F., and R. C. Feiock. 2018. “Applying an Institutional Collective Action Framework to Investigate Intermunicipal Cooperation in Europe.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1 (4): 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvx014.

- Tricaud, C. 2021. “Better Alone? Evidence on the Costs of Intermunicipal Cooperation.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3827613.

- Voorn, B., M. Genugten, and S. Thiel. 2019. “Multiple Principals, Multiple Problems: Implications for Effective Governance and a Research Agenda for Joint Service Delivery.” Public Administration 97 (3): 671–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12587.

- Warner, M. E., A. M. Aldag, and Y. Kim. 2021. “Privatization and Intermunicipal Cooperation in US Local Government Services: Balancing Fiscal Stress, Need and Political Interests.” Public Management Review 23 (9): 1359–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1751255.

Appendix A:

Additional information on dataFootnote12

Table A1. Municipalities in local federations in upper secondary education 1998–2021.Footnote14.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics of municipalities in main analysis (csdid model).

Table A3. List of variables, definitions, and sources.

Appendix B:

TWFE model

As described in the section on empirical strategy, methodological literature advises against using the two-way fixed effect (TWFE) model in settings with staggered treatment (de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille Citation2020; Goodman-Bacon Citation2021; Sun and Abraham Citation2021). The results of the TWFE model are thus only included to showcase potential differences in results between the new and old differences-in-differences methods, as well as to discuss potential explanations for why these differences may occur.

In , the regression estimates for the effect of being part of a local federation on education expenditure and grades are displayed, which incorporates year and municipal fixed effects. Additionally, municipal controls are included in models 2 and 4, consisting of the same variables as those in the csdid model presented in .

Table B1. The effect of being part of a local federation on expenditure on education (log) per student and grades.

For the effect on grades (model 1 and 2) the results are similar to the main specification in . However, the TWFE model provides a larger coefficient, indicating that the effect of joining a local federation is a lowered school cost of between 5 and 7 percent compared to not joining a local federation. As for grades, the results are not statistically significant, and the coefficient is much smaller than in the main specification of the csdid model. With the TWFE model, the average effect of joining a local federation is estimated to result in a decrease of 0.05 grade points, while the csdid model estimates this effect to be a decrease in grade points of 0.4.

For the sake of inquiry, the TWFE model is also employed on the full dataset in , which includes municipalities that were already treated in 1998 and those that exited the federations during the studied time period. This inclusion does not lead to any substantial changes to the estimates – the results are nearly identical to those in . Consequently, the results for grades once again differ substantially from the csdid model.

Table B2. The effect of being part of a local federation on expenditure on education (log) per student and grades, full dataset.

Just as the csdid model, the TWFE model relies on the parallel trend assumption. Therefore, the regression is conducted with leads and lags to assess whether there are any treatment effects prior to the treatment period, which could indicate evidence against this assumption. displays the results, showing that none of the pre-trends are statistically significant, suggesting that the parallel trend assumption may indeed hold.

Table B3. The effect of being part of a local federation on expenditure on education (log) per student and grades, model including leads and lags.

What, then, might account for the variance in results between the csdid model and the TWFE model concerning the estimation of the effects of joining a local federation on grades? As previously noted, one plausible explanation is treatment heterogeneity, indicating that the treatment effect varies significantly depending on which municipality joins the local federation and when this occurs in absolute time. Such treatment heterogeneity seems to be present for both outcome variables, grades and school cost, when looking at the group-specific effects presented in Appendix C. For example, municipalities that joined a local federation in 1999 experienced an average treatment effect of lowered grades by 0.76 grade points compared to if they had not joined the federation. In contrast, municipalities that joined in 2013 saw a slightly positive effect on grades from joining a local federation. When encountering heterogeneous treatment effects, the use of TWFE models is not advisable. Instead, models that take treatment heterogeneity into account, such as the csdid model applied in this study, should be used.

Appendix C:

Group-specific and calendar time effects

The group-specific and calendar time effects using the main csdid specification (i.e. including covariates) are displayed in , respectively. Group-specific effects summarize average treatment effects based on the timing of a municipality’s entry into a local federation, i.e., the year when a municipality is first treated. In this case, the aggregated estimates by group support the notion that joining a local federation reduces education costs and negatively impacts grades. However, there are signs of treatment heterogeneity for both school costs and grades, as the majority – but not all groups – have negative coefficients. Furthermore, the effect size differs between groups.

Table C1. Group-specific effects of joining a local federation on school costs and grades.

Table C2. Calendar time effects of joining a local federation on school costs and grades.

Calendar time effects report average treatment effect by year, i.e., it reports the average effect of participating in the treatment in a particular year for all groups that participated in the treatment in that year. For calendar time effect, the aggregated results are negative and significant only for grades, not for school costs.Footnote13

Appendix D:

Robustness test

presents the findings of a placebo test investigating the impact of joining a local federation in upper secondary education on emergency services costs (measured in Swedish krona/inhabitant). According to the results, there appears to be no significant impact of the treatment on this variable. Neither one of the years following treatment are significant or close to significant, nor the aggregated summary measure for the period.

Table D1. Impact of joining a local federation on costs for emergency service, model with covariates.