ABSTRACT

The article employs a model of interdependency of institutional choices and seeks to investigate the determinants of the provision and production of bus transportation services. We find that municipal population size and low levels of debt are the main drivers of service provision. The decision to cooperate in the provision of bus services is associated with municipalities that have lower levels of financial autonomy. Lastly, we find that larger municipalities and those not run by center left-wing mayors are more likely to opt for the externalization of bus services, either to municipal corporations or to private providers.

Introduction

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, public transportation is a system of transport for passengers available for use by the general public, managed on a schedule, operated on established routes, and that charge a fee for each trip. The system is typically paid for and run by government and/or private operators and can include assorted means of transportation, such as buses, trains, and metros, among others. In this article, we focus on bus transportation services (BTS), typically provided by municipalities, either alone or in cooperation with neighboring local governments.

Public transportation displays a set of unique features that distinguish it from other services typically provided by municipalities, such as water distribution or solid waste collection. BTS provided at the municipal level do not require substantial investments to start the activity and entail low asset specificity (Brown and Potoski Citation2003; da Cruz and Marques Citation2014), since buses can be sold to other municipalities, entities or companies and redeployed to alternative uses. In addition, bus drivers are not specific human assets, since they can drive other large vehicles besides buses. In terms of service measurability, bus transportation systems are relatively easy to measure, as their efficiency and effectiveness can be assessed through consumer surveys about aspects of the service such as punctuality, comfort, number of buses, number of stops, behavior of drivers, among others. In turn, low asset specificity and the ease of measurement translate into low transaction costs of service provision, which are thus less decisive for choosing a production model (Brown and Potoski Citation2003). Compared to services such as health care for the elderly or daycare services for children, which are labor-intensive, bus transportation services are capital-intensive and, therefore, better able to capture economies of scale (Szmigiel-Rawska, Łukomska, and Tavares Citation2021).

This study does not intend to compare various types of services, so the service features of public transport are not central to the hypotheses regarding the service delivery model employed by each municipality. Instead, the article contributes to the literature in three different ways. The first contribution is theoretical and can be extended beyond BTS. Our framework attempts to mimic the order of the decisions faced by local officials by sequentially addressing the factors affecting the decision to provide the service and the determinants of the choice of production model. Second, and related to the first, the study employs a research design accounting for this interdependency of choices, underscoring the empirical links between each stage. Third, from a practitioner’s view point, the empirical findings highlight specific patterns involved in the provision and production decisions, which may help local officials get a better understanding of the trade-offs associated with each decision in BTS.

The article seeks to answer three research questions. First, we ask what factors affect a municipality’s decision to provide a bus transportation service. Second, we are interested in unveiling the determinants of cooperation as a mode of governance. The last question concerns the determinants of the choice of production model for providing BTS in Portuguese municipalities. A non-experimental cross-sectional design is used, which allows for the comparison of a large group of cases from the same unit of analysis at a single point in time.

This article is divided into eight sections. After this introduction, the second section reviews the literature on the determinants of the choice of service delivery mode by local governments in BTS. The third section presents the theoretical framework and hypotheses. Next, we characterize BTS in general and contextualize the study by providing information on how it has been carried out by Portuguese local governments in recent years. The fifth section introduces the research methods and data employed in the empirical analysis conducted on section six. Section seven discusses the results and the last section concludes.

Background on the modes of service delivery of public transportation

Prior empirical research has focused on the governance and regulation of BTS (Albalate, Bel, and Calzada Citation2012; Swarts and Warner Citation2014) and the efficiency of alternative management forms (Campos-Alba et al. Citation2020), but, to the best of our knowledge, no extant studies have investigated the determinants of provision and inter-municipal cooperation for the delivery of BTS. Similarly, empirical studies have failed to address the production choices and trade-offs involved in the provision of BTS. For the most part, the aforementioned research has been primarily concerned with the use of private capital and private firms in the production of publicly funded bus transportation services. The main reason for involving a private entity in the production of BTS is cost savings, but other goals are also possible, including improved technical expertise and private capital investments to modernize the quality of services (Bognetti and Robotti Citation2007). Next, we address these motivations in further detail, particularly the competition between suppliers, the economies of scale involved in service production and the sectoral differences in labor practices (Ferris and Graddy Citation1986).

Several arrangements for the delivery of BTS aim to integrate private capital into the provision of service delivery and increase the competition between suppliers. In Berlin, the transport service provision structure is a mixed company, as there is a public parent company that owns three private companies that provide the service together (Swarts and Warner Citation2014). There is a hierarchical and dependent relationship, both fiscal and legal, which allows the public parent company to exercise authority and monitoring over other private companies, simultaneously guaranteeing the quality and universality of the service as a public goal, and the possibility of cost savings and gains in efficiency and flexibility by the competing private counterparts. Furthermore, transaction and monitoring costs between the service buyer (the public sector) and the service producer (the private sector) tend to be lower in this service delivery model. This is due to the parent company’s ability to monitor subsidiaries and exercise control over them, replacing the management of the private operator or even dissolving a subsidiary if needed (Swarts and Warner Citation2014).

In contrast with the Berlin case, in Barcelona, there is one public company and several private ones operating in the market (Albalate, Bel, and Calzada Citation2012). Bus transportation services consist of a public company and several private companies that operate the service through different concessions. The private companies facilitate the detection of inefficiencies in the public company and help contain labor conflicts and union demands, whereas the public company provides “the regulator information about costs and demands that is useful for overseeing private operators and protecting passengers’ interests” (Albalate, Bel, and Calzada Citation2012, 84). According to Warner and Hefetz (Citation2008), this mixed delivery model at the market level guarantees organizational redundancy in the system, avoiding the negative outcomes of a public monopoly and ensuring the provision of the service in the event of contract failures.

Yet another form to involve private capital in the provision of public services is to use a mixed company operating under private law, where ownership is divided between the local government and a private partner (Bel and Fageda Citation2010). In situations where there are limits to the local public debt, as is the case in Italy and Portugal, private capital can be used to finance investments necessary to maintain economically efficient and up-to-date services (Bognetti and Robotti Citation2007). However, da Cruz and Marques (Citation2012) warn that mixed companies tend to pursue the objectives of the private sector, instead of protecting the public interest.

The second reason for the use of private providers in publicly funded bus transportation services is the capturing of economies of scale. Because private companies do not have their activity restricted to a single municipality or jurisdiction, they manage to achieve economies of scale by distributing their fixed costs over several geographic units (Bel and Miralles Citation2003; Wassenaar, Groot, and Gradus Citation2013). The use of the contracting mechanism to explore economies of scale is particularly relevant for small municipalities, which most likely will have a production scale below the optimum for most services (Bel and Fageda Citation2006). Private companies gear their activity towards results (outputs and outcomes) (Bel and Miralles Citation2003; Wassenaar, Groot, and Gradus Citation2013), aiming at maximum efficiency in the production and provision of goods or services. The financial capacity of large private companies allows them to invest in innovations in terms of production, processes, infrastructure and equipment, which translate into savings in production and maintenance costs in the long term (White Citation1997). Due to the intrinsic characteristics of private companies, they will be able to provide the service at the lowest price (Bel and Miralles Citation2003).

Private companies are guided by objectives of profit maximization and cost reduction, which can result not only in reductions of service quality, but also in uneven coverage of provision. For example, it may be inefficient and costly to operate a certain bus route because the number of passengers in that area is small, which will lead a private company with profit-maximizing objectives to cease service. Private companies can choose their market and the services they provide, while the public sector is expected to provide a universal good or service (Petersen, Hjelmar, and Vrangbæk Citation2018). Thus, contracting a private company may entail some risks of discontinuity and the creation of social injustices (Joassart-Marcelli and Musso Citation2005). Furthermore, the transfer of responsibility for the production of services to private sector companies allows local governments to shift the blame for any loss of quality or inequalities in service provision (Joassart-Marcelli and Musso Citation2005).

The third issue related to the private provision of BTS are the different labor practices across sectors. The private sector is governed by private commercial law, which provides greater flexibility in the management of processes and human resources (Bel and Fageda Citation2010; Bel and Miralles Citation2003; Wassenaar, Groot, and Gradus Citation2013). In the case of BTS, labor costs represent a large share of the total costs of service production (Albalate, Bel, and Calzada Citation2012). In the private sector, workers’ wages are normally lower than in the public sector, as the latter suffers from continuous pressure from public sector unions to raise wages. Thus, the private sector tends to save costs when operating bus transportation services (Albalate, Bel, and Calzada Citation2012; White Citation1997).

A related problem concerns the greater flexibility in hiring, firing and distributing work incentives in the private sector. While flexible labor regulations can provide greater cost savings and increased efficiency, in some contexts job flexibility translates into lower wages for workers and reduced job incentives and benefits, thus weakening workers’ power (Swarts and Warner Citation2014). Such situations can lead to a decrease in the quality of the service and public safety.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Ferris and Graddy (Citation1986) developed an analytical model of the decision to provide and produce a public service based on two steps: first, local officials must decide whether the service under consideration will be provided internally, through partnerships with other local governments or through contracting. Once this step is settled, the second decision involves choosing who will be in charge of production: the local governments own staff, other governments, non-profit organizations or private companies. Bel, Fageda and Mur (Citation2014) mention two decision dimensions in the Spanish context. The first is related to the level of provision of the service, and therefore distinguishes between individual provision – at the municipal level – and collaborative provision – at the inter-municipal level. The second dimension corresponds to the production decision, which, in turn, can be public or private.

Adapting these dimensions to the case under analysis, we argue that local officials have three decisions to make concerning BTS. The first decision involves the choice between providing or not providing the service. In theory, all local governments may wish to provide BTS, but, in practice, small populations, low densities and/or financial constraints may prevent that desideratum. Once a local government decides to provide the service, the second decision concerns the mode of provision. The municipality must choose between providing the service alone or delegating provision to some form of inter-municipal cooperation (IMC) organization. The latter case contemplates situations where the mayors as members of an IMC organization jointly make a decision over service production.Footnote1 The third and final decision concerns the production of the service. This production decision may involve contracting out (decided by the municipality or by the IMC organization), delegation to a municipal corporation (decided by the municipality alone) or to an inter-municipal corporation (decided by the IMC organization) or an in-house bureaucracy, either of the municipality or of the IMC organization.Footnote2

. clarifies the sequence of decisions and the options available to the local decision-makers.

After reviewing the literature, we now turn to the operationalization of the hypotheses, divided into three groups corresponding to the three research questions: 1) why do municipalities provide BTS? 2) Why do municipalities cooperate in the provision of BTS? And 3) what are the determinants of the choice of production model for BTS? In each group, we first present the hypotheses related to contextual factors, which are exogenous to the local government organization, and then introduce the hypotheses related to the internal determinants of each decision.

Provision decision

Why do municipalities provide bus transportation services?

The first decision concerns whether or not to provide the service. This decision will likely be constrained by local market conditions. Local officials may wish to provide the service, but small, rural and underfunded municipalities will find it harder to delivery bus transportation services. Kim and Warner (Citation2016) analyzed the relationship between local financial stress and the level of service provision, considering the characteristics of the municipalities in post-Great Recession United States. The authors concluded that larger municipalities have higher levels of provision as well as a greater variety of public goods and services. The decision to provide BTS should be directly linked to the size of the municipality. Small municipalities will not have sufficient demand to justify the provision of the service. BTS depend on economies of scale to be profitable, thus making medium and large cities above a certain level of population the most likely settings to find the provision of these services.Footnote3 Hence, we expect that:

H1a:

Medium and large municipalities are more likely to provide bus transportation services.

Besides the size of municipal population, Ladd (Citation1992) has also identified the dispersion of population as a crucial factor to determine the optimal geographical coverage of service provision. In BTS this is particularly relevant, because ceteris paribus, a more disperse population entails longer routes serving fewer passengers, thus leading to higher costs per passenger and per route. Conversely, municipalities with higher levels of population density are more likely to experience lower costs in the provision of BTS due to economies of density (Bel and Warner, Citation2015). The expectation is that:

H1b:

Municipalities with higher population density are more likely to provide bus transportation services.

Even if the local conditions are met to secure the technical viability of service provision, the municipality may lack the necessary financial conditions to meet this goal.

H1c:

Municipalities experiencing worse financial conditions are less likely to provide bus transportation services.

Why do municipalities cooperate in the provision of bus transportation services?

The second stage of decision-making concerns the provider’s decision about whether to compete or cooperate. As in the previous stage, we discuss the exogenous factors of the cooperation decision first and the internal determinants next. If a municipality decides to cooperate in the provision of the service, it delegates the authority over the production decision to some form of IMC arrangement, typically an organization where all mayors (or other local officials) are represented and this organization (the provider) chooses the mode of production. Thus, a municipality can choose to cooperate in the provision stage and then all municipalities involved in the IMC organization establish a contract with a private operator for BTS in the production stage. This way, a municipality can choose to delegate BTS powers to an IMC organization, while retaining veto power over the production decision (Teles Citation2016).

The option to cooperate with other municipalities, delegating responsibilities to an IMC organization may be motivated by financial restrictions, spatial factors, such as the degree of urbanization, and organizational factors (Bel and Warner Citation2016; Camões et al. Citation2021). One of the most important factors driving cooperation with other municipalities is cost reduction through the exploration of economies of scale (Bel and Warner Citation2016; Bel, Fageda, and Mur Citation2014). Smaller municipalities are also more likely to face problems related to lack of competition, higher transaction costs and cross-jurisdictional externalities (Bel & Warner, Citation2015). According to Bel, Fageda and Mur (Citation2013), small municipalities tend to cooperate in order to achieve economies of scale, lower transaction costs and reduce concerns about the lack of competition in their jurisdiction. Likewise, Shrestha and Feiock (Citation2011) have found that cities of smaller size are more likely to engage in higher levels of cooperation. In the Portuguese case, the IMC organization may choose to contract BTS to a private company expecting cost savings and a reduction in the risks of contracting, since these risks will be divided among all the municipalities involved. It is also more likely that an IMC organization will be able to hire human resources with greater technical capacity to deal with contracting procedures. In fact, Bel et al. (Citation2014) concluded that smaller local governments manage to significantly reduce service costs when they delegate the responsibility for providing the service to the districts, regardless of the choice between public and private production. Still, Campos-Alba et al. (Citation2020) show that the inter-municipal cooperation option is the most efficient solution in small and medium-sized municipalities, with regard to BTS. Provision of this service directly through the municipality is more efficient in larger municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants (Campos-Alba et al. Citation2020). In this sense, and because BTS has the potential to explore economies of scale, the following working hypothesis is proposed regarding the size of the municipality:

H2a:

Small municipalities prefer to cooperate with other governments through IMC organizations in the provision of bus transportation services.

A municipality in greater financial difficulties may find IMC pertinent to contain service provision costs, as shown by Bel et al. (Citation2013) in a study of solid waste collection services in the municipalities of Aragon, Spain. Joassart-Marcelli and Musso (Citation2005) also conclude that municipalities with lower financial capacity tend to outsource services, favoring IMC over direct privatization. Zullo (Citation2009) analyzed inter-municipal contracting decisions by local governments in the United States in the 1992–2002 period and found that a high debt burden was associated with inter-municipal contracting for public transit but not for the other services. Zafra‐Gómez, Prior et al (Citation2013; Zafra-Gómez, Pedauga, Citation2014). investigate a large sample of Spanish municipalities and find that local officials are more likely to cooperate when facing a financial crisis assessed by a multitude of indicators, including insufficient transfers, negative cash flows, debt, or budget deficits. Hence, we expect that:

H2b:

Municipalities experiencing worse financial conditions tend to cooperate more in bus transportation services.

Several studies attribute the performance of public sector-oriented delivery models to the pressure exerted by civil servants and public sector unions. Civil servants are important actors in the management of public production and delivery, as a result of the growing and continuous decentralization of the public sector. The use of contracting out to private companies to provide public services, reduces the role of the State, and may jeopardize the employment of civil servants (Ferris and Graddy Citation1986), compromising their ability to defend public values. Warner and Hebdon (Citation2001) argue that the greater presence of civil service unions in the municipality increases inter-municipal cooperation, whereas Chandler and Feuille (Citation1994) found that the presence of a municipal sanitation union reduces the probability of contracting out in cities with a very cooperative relationship with the union. Bel and Fageda (Citation2007) reach the same conclusion. The number of unions is positively related to the number of civil servants. In this sense, we argue that:

H2c:

Municipalities with a greater relative number (weight) of civil servants tend to cooperate more.

Production decision

The hypotheses related to the third moment of decision-making are presented below. Following the same structure of the previous stages, we begin with a discussion of the hypotheses related to the exogenous (or contextual) factors followed by the hypotheses linked to the internal determinants.

What are the determinants of the choice of production model for BTS?

The search for efficiency gains and cost savings are factors that motivate the choice of alternative production models to in-house production (Szmigiel-Rawska, Łukomska, and Tavares Citation2021), namely contracting out the service (Ferris and Graddy Citation1986) or delegation to an organization at arm’s length (e.g. a municipal corporation) (Tavares and Camões Citation2023). Competition among producers is a major factor in the minimization of production costs (Rodrigues, Tavares, and Araújo Citation2012). In larger municipalities, there will be more private competitors due to the existence of greater potential for capturing economies of scale (A. Tavares and Rodrigues Citation2017). Thus, more populous municipalities are more likely to experience the presence of a greater number of competitors for the outsourcing contract and more likely to save costs through externalization to a private company (Ferris and Graddy Citation1986; Nelson Citation1997; Szmigiel-Rawska, Łukomska, and Tavares Citation2021).

On the other hand, when it comes to deciding how to produce the service internally, Tavares and Camões (Citation2007, Citation2010) concluded that larger municipalities prefer production by municipal companies rather than through the municipality’s own services. All else equal, we expect that:

H3a:

Large municipalities are more likely to prefer a market-oriented production of bus transportation services.

H3b:

When favoring public sector production, large municipalities are more likely to prefer the production of BTS through municipal companies than using in-house production.

Population density is also related to the production choice. Population density is an indicator of the degree of urbanization. Bel et al. (Citation2013) concluded that the greater the population dispersion in a municipality, the greater the incentives for local governments to produce certain services internally, given the lack of accessible quality monitoring mechanisms. Rural municipalities with a large population dispersion and lower population density are less attractive to private investments, so the number of competitors for a BTS contract is small in these territories (Hultquist et al. Citation2017). Due to the lack of a market and also the limited capacity of human resources to design and monitor contracts, the externalization option becomes less feasible in rural municipalities with low population density (Bel, Fageda, and Mur Citation2013; Hultquist et al. Citation2017; Mohr, Deller, and Halstead Citation2010). We expect that:

H3c:

Municipalities with lower population density are more likely to prefer the production of BTS using their own staff or a municipal company.

Financial stress is an important internal constraint in the choice of BTS production. Tavares and Camões (Citation2007) analyzed the municipal corporatization decisions of Portuguese municipalities and concluded that local governments less dependent of intergovernmental transfers prefer to transfer the provision of services to municipal corporations. In doing so, local governments relinquish user fees, but are able to take advantage of more flexible financial and human resource management rules, resulting in more efficient services (Tavares and Camões Citation2007). Faced with a situation of fiscal crisis and financial dependence on the central government, municipalities tend to produce local services internally (Tavares and Camões Citation2010), thus associating the outsourcing of services to financial “good times” (Bel and Fageda Citation2017; Pallesen Citation2004).

An analysis of local government service delivery in Poland concluded that municipalities with both budget surplus and debt tend to delegate the service production to municipal corporations (Szmigiel-Rawska, Łukomska, and Tavares Citation2021). The authors reach the same conclusion as Tavares & Camões, Citation2007, Citation2010), showing that wealthier municipalities are more likely to prefer private contracting over in-house production. On the other hand, they also find that municipalities under financial stress delegate services to municipal corporations to avoid the discontinuity of the service and reductions in quality. In contrast to in-house production, delegation to municipal corporations allows them to evade responsibility over any problems that may emerge in the production of the service. In turn, the study by Carr, Leroux and Shrestha (Citation2009), which focuses on local governments in the U.S., concludes that the richest municipalities and those that manage to raise more own revenues through the application of fees and taxes, have a greater capacity to produce services internally, discouraging them from contracting private companies (Carr, Leroux, and Shrestha Citation2009).

Despite Bel and Fageda’s (Citation2007) conclusion that studies focusing on a single service generally do not find financial constraints as a determining factor, the findings described above suggest that:

H3d:

Municipalities in better financial situation are more likely to prefer the production of BTS through municipal companies.

In addition to factors related to production costs, the choice of BTS production may depend on political-ideological factors, such as the autonomy of the local government (Pallesen Citation2004). In Portugal, the most representative parties cover the political spectrum from the ideological left to the right. Right-leaning parties tend to prefer market-oriented service delivery solutions (Bel and Fageda Citation2010; Feiock, Clingermayer, and Dasse Citation2003; Girard et al., Citation2009), since they aim to decrease the role of the State (Tavares and Camões Citation2007). The more progressive left-leaning parties favor public values and tend to prefer in-house production solutions (Bel and Fageda Citation2010). Still, when the decision is between using municipal corporations and granting the service to a private company, Tavares and Camões (Citation2010) conclude that left-leaning parties prefer the use of municipal corporations, whereas right-leaning parties opt for contracting out to private companies. Thus, we expect that:

H3e:

Municipalities with left-leaning executives are less likely to prefer BTS production using contracting out to private companies.

Contextualization

In this article we analyze the decisions made by local governments in Portugal concerning bus transportation services. In order to get a better sense of the context of service provision, we applied the theoretical model to describe the actual service delivery choices regarding service provision and production. As in the theoretical model, we first inquired municipalities about whether they provide BTS. While all municipalities in Portugal have the same set of competences assigned by law, including public transportation, regardless of their size, the law is silent on the obligation to provide BTS and on the penalties they might incur if they fail to do so. Next, we ask those that provide the service whether they opted to cooperate or provide the service alone. Lastly, we obtained data on BTS production decisions made by provision authorities (the municipality or the IMC organization).

Most municipalities provide public transportation to their residents, corresponding to 242 out of all 278 municipalities in mainland Portugal. As for the second decision, cooperation is the dominant option, as about 64% of municipalities provide the service in partnership with neighboring municipalities. In addition, the vast majority of municipalities that provide public transport (208) choose to outsource the production to private companies, either through IMC or direct municipal provision.

Based on 2018 data on the modes of production of BTS, we note that all municipalities that decide to cooperate make the same production decision: contracting out to private firms. There are no inter-municipal companies as BTS producers and not a single IMC organization uses its own staff to produce BTS. Thus, if a municipality decides to delegate the authority for BTS service provision to an IMC organization, this IMC organization will hire a private operator to produce the service in all cases (155 in total).

Eighty-seven municipalities retain the authority over service provision. In contrast with the 155 that cooperate through IMC organizations, this smaller group opts for a more diverse set of options. Of the 87, the majority (53) prefers contracting out with a private firm, 27 produce the service in-house and seven opted for a municipal corporation. shows the provision and production choices of BTS made by Portuguese municipalities.

To sum up, the design and the implementation of service delivery in public transportation, involves three choices. One, the provision decision, is the municipal binary choice regarding providing or not BTS. Another, the cooperation decision, is also a binary choice about cooperating with other municipalities or providing the service alone. Lastly, the production decision consists in the choice among the several alternatives for service delivery. Notice that these three decisions are all discrete choices. In addition, it is very clear that the provision decision precedes the cooperation and the production, which may occur simultaneously or sequentially. The data and the estimation methods employed in the empirical analysis are described in the following section.

Data and methods

Data

The first dependent variable in our study takes the value 1 if the municipality provides the service, and 0 if it does not. The second dependent variable is also dichotomous and takes the value of 1 if the municipality opts for cooperation in the provision of the service and 0 if it prefers to go at it alone. The third and final dependent variable can take four values: production through an in-house bureaucracy (1); production via municipal corporation (2); municipal contracting out of a private firm (3); and inter-municipal contracting out of a private firm (4). The categories of this variable may be ordered by the degree of complexity to reflect increasing transaction costs as we move along the delegation path from in-house production → municipal corporation at arm’s-length → municipal decision to contract out to a private firm → IMC organization decision to contract out to a private firm. We chose to separate and evaluate the two forms of outsourcing since they are the most frequent modes of production employed in Portugal and because they entail different levels of complexity related to the presence of multiple principals in the second form (Bel et al. Citation2023).

These data were collected directly from the websites of the municipalities, as well as from the Portuguese IMC organizations (Comunidades Intermunicipais). When the analysis of these internet websites indicated the presence of private production for a given municipality or group of municipalities, the information was crosschecked with data on the base.gov.pt, a website where all public contracts are included.

The independent variables included in our estimations are described and explained in . The municipal population and density variables use data from the 2011 Census, since it is the most reliable source and does not rely on annual estimates. In the case of debt per capita, we employ data from 2015 as it is the year of publication of the legal framework of bus transportation services (RJSPTPFootnote4), which changed the institutional model for the provision and production of BTS. For this calculation, we use the estimated municipal population in 2015, published by Institute of National Statistics (INE).

Table 1. Independent variables (descriptions, sources and expected signals).

Financial autonomy and the proportion of civil servants are calculated as three-year averages: the year the RJSPTP was approved, and the following two years, to internalize any exogenous fluctuations in numbers. Data from 2017 were used for the political party variable, corresponding to the first municipal elections that took place after the approval of the RJSPTP in 2015.

shows the summary statistics of the variables included in our study.

Table 2. Summary statistics (dependent and independent variables).

Note that only the first dependent variable includes observations for all the municipalities in mainland Portugal (278), since the aim is to explain the factors influencing the decision to provide BTS. The remaining dependent variables only include the municipalities that actually provide that service (242 observations). The independent variables population and population density include all 278 observations, since they are the potential explanatory factors of the decision to provide BTS.

Design and estimation

In order to analyze the decisions made by the local officials, we rely on discrete choice models, designed to address situations in which a political or administrative agent faces a choice or a series of choices among a set of two or more options or alternatives (Train Citation2009). As with the municipal decisions regarding BTS delivery, the ultimate goal is to understand the behavioral process that leads to the decision maker’s choice, assuming the existence of factors associated with that choice.

The econometric analysis of these models focuses on estimating the probability of choosing a particular alternative, with the limitation that only the chosen alternative is observed and all the remaining ones are unobserved. The structure of the observed and the unobserved error terms determines the specific model that is assumed and estimated. In this analysis of the determinants of municipal service delivery of BTS in Portugal, severe limitations are imposed by the specific pattern of choices made, considering the concentration choices in municipal and inter-municipal contracting out solutions (208) as opposed to the other alternatives of in-house production (27) and municipal corporations (7), as shown in .

We use two complementary strategies to circumvent this difficulty. First, we estimate the determinants of provision and production using separate regression models for each choice problem. The estimation of separate regressions is the easiest way to proceed, but it is unrealistic, as it assumes and treats provision, cooperation and production decisions as if they were separate and independent moments. The advantage is the more straightforward use of logit for binary decisions and multinomial logit for multiple unordered alternatives.

Next, we use nested logit models to analyze our case since the cooperation and production decisions are clearly not independent. When the decisions are dependent, the random errors can no longer be treated as independent. The essence of the nested logit models is an estimation relaxing the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) – according to which the odds ratio of any two alternatives are independent of the other alternatives – and the grouping of alternatives (nests) for which unobserved shocks may have concomitant effects. The choice of both municipal and inter-municipal delivery production choices suggests that this approach fits more realistically the choice problem under analysis.

Two additional notes regarding the estimation of nested models are required. On the one hand, these models do not imply or assume any temporal sequence of decisions among the nests. On the other hand, the estimation requires alternative-specific variables to estimate the choice equation, and that the variables (alternative or unit-specific) are not repeated in the regressions of the nests.

The severe constraint here is the unavailability of those alternative-specific variables. In order to overcome this limitation, an artificially-created ordinal variable had to be introduced, measuring the delegation/monitoring complexity of the four production alternatives and normalized to vary between 0 and 1. The least complex production alternative is in-house production (assumed to take on the value of 0) and the most complex is inter-municipal contracting out (assumed to be 1). Municipal corporations (assumed to be 0.25) and municipal contracting out (assumed to be 0.75) fall in between. A multiplicative term (complex * ldens) was also included to increase the number of the alternative-specific variables.

Findings

Baseline estimations – separate logit regressions

presents the baseline results estimated with separate logistic regressions for the different decisions made by the local officials regarding the organization of municipal BTS. These results provide global statistical support for the hypotheses and show some interesting patterns. First, it seems clear that the size of the municipality in terms of population is a robust key driver of the provision, cooperation and production decisions. Second, financial concerns, either per capita indebtedness or financial autonomy to raise local revenues, are also critical factors for those decisions. Finally, political (ideological) considerations are mostly relevant to explain the choice of the production alternative (in-house, municipal corporation, contracting out, and inter-municipal contracting out).

Table 3. Baseline estimations - separate logit models.

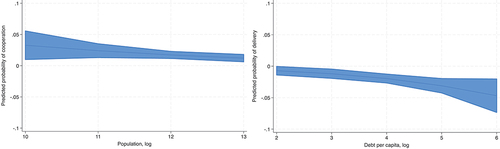

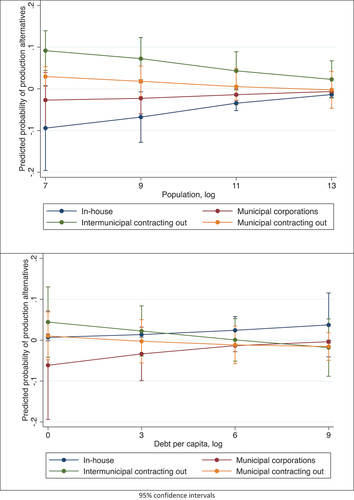

Referring more specifically to each of the three decisions, present the marginal effects of the statistically significant variables. The provision decision is driven mostly by population size and by the financial situation of the municipality (). Notice that size has a positive effect on the likelihood of providing BTS, although this effect gets marginally smaller in larger municipalities. In the case of the financial situation of the municipality, the effect is more straightforward. Debt per capita affects negatively the likelihood of provision and the effect is reinforced as the debt per capita increases.

Next, we analyzed the probability of cooperation in the provision of BTS. The analysis indicates that the probability of cooperation is positively related to the increasing proportion of municipal employees and negatively associated with financial autonomy (). In the first case, the statistically significant effect is relevant only above around 40 employees per 1,000 inhabitants. In the case of financial autonomy, the efforts to cooperate are relevant only up to a certain level, approximately 40% of own revenues. Above that level the negative effect vanishes or even reverts after 80%. This is an interesting result, which certainly deserves further investigation.

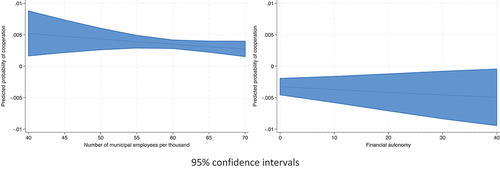

With regard to the production decision, the four alternatives available to the municipalities make the analysis of the driving factors more complex. For example, the effect of population size on the choice of alternatives is much sharper for small municipalities, for which inter-municipal contracting out is the preferred solution, as opposed to in-house production. For larger municipalities, the differences among the alternatives decrease and almost disappear. In the case of debt per capita, the hierarchy of the preferred alternatives completely reverses in the relevant interval, but the results are far weaker, as the 95% confidence intervals encompass zero. At zero or near-zero debt levels, municipalities appear to prefer inter-municipal contracting out while municipal corporations are much less considered. As debt increases, the preferred choice clearly turns out to be in-house solutions ().

Financial autonomy depicts the opposite trend of population size. Low levels of autonomy show no clear pattern of preference among the alternatives. The clear differences emerge above a certain level, roughly 50–60% of own revenues, a point after which municipal corporations become the clear preference. The problem is that the corresponding coefficients are statistically significant but near zero.

Finally, ideological concerns are most relevant regarding the choice between production alternatives. As indicated by the negative and statistically significant coefficients on , left-leaning governments are less prone to consider municipal corporations and contracting out in the delivery of BTS, seen as market-like, as opposed to in-house solutions. This result is also not surprising as it is consistent with traditional ideological divisions.

Addressing interdependent decisions – nested logit models

As referred in the design and estimation section, treating the decisions as independent and estimating separate regressions is straightforward but somewhat unrealistic. In fact, it is quite likely that the provision, cooperation and production decisions are interdependent. This interdependence leads to the estimation relaxing the IIA assumption and the grouping of alternatives (nests) and the use of nested logit models.

presents the results regarding the decision to cooperate and the production choices. They partly corroborate the previous results, considering the significant differences of specification imposed by the need to include alternative-specific variables and the restriction of non-repetition of variables across regressions. One important difference in the results is the effect of scale (population size and density) in the decision to cooperate. Municipal size was positively associated with cooperation in the separate logit model, which was inconsistent with H2a and most findings in the empirical literature. In the nested logit estimations, however, population displays a negative coefficient, which is consistent with the argument that small municipalities cooperate more in the provision of BTS. In the case of density, the coefficient is positive and marginally statistically significant, indicating that cooperation in the provision of BTS increases with density. As to the production decision, financial considerations, namely debt per capita, play a considerable role. Political concerns do not appear as significant in any of these results.

Table 4. Nested logit estimations.

Discussion

In this article we examined the provision and production decisions of Portuguese municipalities in bus transportation services. Empirical analyses in this domain are still scarce and our work is motivated by our research agenda centered on testing theoretically-driven hypotheses using data from different municipal services.

Compared to other services, bus transportation services involve low transaction costs, primarily because human and material assets are not specific and because performance is easily measured and evaluated. In practice, this means that inter-municipal cooperation and outsourcing production to private firms are appealing options to local decision-makers. Our findings are largely in line with these expectations.

As predicted in H1a and H1c, the empirical analysis indicates that the decision to provide these services is driven primarily by the size of the municipality and the state of the local finances. Consistently with the results obtained by Kim and Warner (Citation2016), we found that larger municipalities and those least affected by municipal debt are more prone to provide BTS. This result suggests that municipalities respond to the size of the demand (H1a) and that this response is contingent on their financial status, but not on the level of density of a municipality (H1b).

The findings concerning the decision to cooperate for BTS are slightly more mixed. The conventional estimation through a logit model suggests that more populous municipalities with a larger local government workforce and lower financial autonomy cooperate more. The result is partially consistent with arguments related to capacity (H2b) and the size of the local workforce (H2c), but contradicts the idea that smaller municipalities cooperate more (H2a). However, when re-estimating the analysis using nested logit models to accommodate the interdependency of choices and removing financial autonomy from these estimations, we do find that smaller municipalities tend to cooperate more, as predicted in H2a and most literature (Bel and Warner Citation2016). A clearer picture emerges as a result: the level of financial autonomy appears to be the driving force behind our results (H2b), to the point that it overwhelms the effect of size in our initial estimation. Once that variable is removed, smaller municipal size becomes the driving force (H2a). Thus, it is certainly possible that the level of financial autonomy and size are highly correlated and perhaps gauging a common phenomenon.

The production choices of BTS in Portuguese municipalities seem clearly driven by both financial and ideological motivations. First, consistent with prior findings by Bel and Fageda (Citation2010), market size is one of the driving forces of externalization with larger municipalities preferring outsourcing to private firms, either when providing the service alone or as part of an IMC organization (H6a). Second, outsourcing decisions to any of the three alternatives – municipal corporations, IMC outsourcing to private firms and municipal contracting of private firms – are all the product of good financial status, especially lower debt levels, but also better financial autonomy in the case of municipal corporations (H8), as found by Szmigiel-Rawska et al (Citation2021) in the Polish case. This result is consistent with “the politics of good times”, described by earlier work by Pallesen (Citation2004). Lastly, we also found evidence supporting the idea that outsourcing of BTS in Portugal is driven by ideological values, as both corporatization and municipal outsourcing to private firms is far more frequent in municipalities not run by left-leaning mayors.

Conclusion

This article sought to analyze the provision, cooperation and production decisions of bus transportation services by municipalities in Portugal. BTS are a key function of local governments and empirical knowledge about the motivations for these decisions is still scarce. Our work contains several contributions to the academic literature and to local government decision-makers and practitioners.

Academically, we follow earlier work by Szmigiel-Rawska et al. (Citation2021) in arguing that provision and production decisions are sequential, in the sense that decision-makers first decide whether to produce the service and only after this decision has been affirmative they will move to investigate and choose among production alternatives. Yet, we go beyond the idea of sequential decisions and propose a model of interdependent choices where each decision moment is dependent on the other(s). This is not simply framed as a theoretical argument, but it is also tested empirically in this article by taking advantage of nested logit models, where the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives is relaxed. This is our main contribution to the academic research of service delivery choices. Concomitantly, we also contribute to this literature by investigation these choices in BTS, which traditionally face lower transaction costs than other municipal services, such as water supply or social welfare services. In doing so, we support a research agenda of local government scholars who are increasingly interested in extracting more generalizing principles regarding provision and production decisions of an assorted array of local public services. We think that the more diverse the set of services and locations where these empirical studies take place, the more robust the conclusions that might be extracted from this research agenda.

From a more pragmatic point of view, our study may also help decision-makers to compare the municipal profile of their locality with the provision, cooperation and production choices made by other municipalities with a similar profile. These profiles tend to vary according to demographic, financial and ideological continuums, thus allowing local officials to determine whether to provide the service and which mode of production to employ.

The main limitation of our work is a product of the unbalance in the data related to the lack of diversity in production choices for BTS in Portugal. On the one hand, certain choices which are theoretically possible (e.g. mixed firms) are not contemplated in the analysis because they are not practiced in Portugal. On the other hand, some alternatives (i.e. municipal corporations) are only chosen by a handful of municipalities, which creates problems for model estimation. The use of the theoretical framework to study municipal choices in other countries with a wider and more diverse set of production alternatives will contribute to overcome these limitations and emphasize the strength of this model of interdependency of provision and production choices.

Acknowledgments

The research underlying this document was partially supported by the Research Centre in Political Science (UIDB/CPO/00758/2020), University of Minho/University of Évora supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science through national funds. It also received financial support from “INOV.EGOV-Digital Governance Innovation for Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Societies/NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000087”, supported by the Norte Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (EFDR).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All Portuguese municipalities participate in IMC “standalone” organizations with their own workforce, which constitutes the IMC equivalent to an in-house bureaucracy.

2. Other forms of service production were excluded from the theoretical model to avoid a more cumbersome explanation and because they are not contemplated in the Portuguese case. These include, among others, mixed firms, intergovernmental contracting or a mixed market similar to the one existing in Barcelona.

3. In this article, economies of scale of BTS will be assessed by the population size of the municipality as a proxy for the number of passengers. The literature recommends using passenger-trips or passenger-miles as the best indicator of demand or market size (Berechman and Giuliano Citation1985). While we are aware this is not an ideal measure, population size should still be a good proxy for the size of the local market and the unit cost of the service.

4. Regime Jurídico do Serviço Público de Transporte de Passageiros.

5. This column was divided into: municipal management (direct provision and municipal corporations), contracting out by a municipality (3) and contracting out by an IMC organization (4).

References

- Albalate, D., G. Bel, and J. Calzada. 2012. “Governance and Regulation of Urban Bus Transportation: Using Partial Privatization to Achieve the Better of Two Worlds.” Regulation & Governance 6 (1): 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2011.01120.x.

- Bel, G., I. Bischoff, S. Blåka, M. Casula, J. Lysek, P. Swianiewicz, A. Tavares, and B. Voorn. 2023. “Styles of Inter-Municipal Cooperation and the Multiple Principal Problem: A Comparative Analysis of European Economic Area Countries.” Local Government Studies 49 (2): 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2041416.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2006. “Between Privatization and Intermunicipal Cooperation: Small Municipalities, Scale Economies and Transaction Costs.” Urban Public Economics Review 6:13–31. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/504/50400601.pdf.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2007. “Why Do Local Governments Privatise Public Services? A Survey of Empirical Studies.” Local Government Studies 33 (4): 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701417528.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2010. “Partial Privatisation in Local Services Delivery: An Empirical Analysis of the Choice of Mixed Firms.” Local Government Studies 36 (1): 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930903435856.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2017. “What Have We Learnt After Three Decades of Empirical Studies on Factors Driving Local Privatization?” Local Government Studies 43 (4): 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1303486.

- Bel, G., X. Fageda, and M. Mur. 2013. “Why do Municipalities Cooperate to Provide Local Public Services? An Empirical Analysis.” Local Government Studies 39 (3): 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.781024.

- Bel, G., X. Fageda, and M. Mur. 2014. “Does Cooperation Reduce Service Delivery Costs? Evidence from Residential Solid Waste Services.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (1): 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus059.

- Bel, G., and A. Miralles. 2003. “Factors Influencing Privatization of Urban Solid Waste Collection: Some Evidence from Spain.” Urban Studies 40 (7): 1323–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000084622.

- Bel, G., and M. Warner. 2016. “Factors Explaining Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Service Delivery: A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 19 (2): 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2015.1100084.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2015. “Inter‐Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence.” Public administration 93 (1): 52–67.

- Berechman, J., and G. Giuliano. 1985. “Economies of Scale in Bus Transit: A Review of Concepts and Evidence.” Transportation 12 (4): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00165470.

- Bognetti, G., and L. Robotti. 2007. “The Provision of Local Public Services Through Mixed Enterprises: The Italian Case.” Annals of Public & Cooperative Economics 78 (3): 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2007.00340.x.

- Brown, T. L., and M. Potoski. 2003. “Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13 (4): 441–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mug030.

- Camões, P., A. Tavares, and F. Teles. 2021. “Assessing the Intensity and Diversity of Cooperation: A Study of Joint Delegation of Municipal Functions to Intermunicipal Communities.” Local Government Studies 47 (4): 593–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1857245.

- Campos-Alba, C., D. Prior, G. Pérez-López, and J. Zafra-Gómez. 2020. “Long-Term Cost Efficiency of Alternative Management Forms of Urban Public Transport from the Public Sector Perspective.” Transport Policy 88:16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.01.014.

- Carr, J., K. Leroux, and M. Shrestha. 2009. “Institutional Ties, Transaction Costs, and External Service Production.” Urban Affairs Review 44 (3): 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087408323939.

- Chandler, T. D., and P. Feuille. 1994. “Cities, Unions, and the Privatization of Sanitation Services.” Journal of Labor Research 15 (1): 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02685675.

- da Cruz, N., and R. Marques. 2012. “Mixed Companies and Local Governance: No Man Can Serve Two Masters.” Public Administration 90 (3): 737–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02020.x.

- da Cruz, N., and R. Marques. 2014. “Rocky Road of Urban Transportation Contracts.” Journal of Management in Engineering 30 (5): 05014010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000224.

- Feiock, R., J. Clingermayer, and C. Dasse. 2003. “Sector Choices for Public Service Delivery: The Transaction Cost Implications of Executive Turnover.” Public Management Review 5 (2): 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461667032000066390.

- Ferris, J., and E. Graddy. 1986. “Contracting Out: For What? With Whom?” Public Administration Review 46 (4): 332–344. https://doi.org/10.2307/976307.

- Girard, P., R. D. Mohr, S. C. Deller, and J. M. Halstead. 2009. “Public-Private Partnerships and Cooperative Agreements in Municipal Service Delivery.” International Journal of Public Administration 32 (5): 370–392.

- Hultquist, A., D. M. Harsell, R. S. Wood, and D. T. Flynn. 2017. “Assessing the Impacts of Transaction Costs and Rapid Growth on Local Government Service Provision and Delivery Arrangement Choices in North Dakota.” Journal of Rural Studies 53:14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.05.003.

- Joassart-Marcelli, P., and J. Musso. 2005. “Municipal Service Provision Choices within a Metropolitan Area.” Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 492–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087404272305.

- Kim, Y., and M. Warner. 2016. “Pragmatic Municipalism: Local Government Service Delivery After the Great Recession.” Public Administration 94 (3): 789–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12267.

- Ladd, H. F. 1992. “Population Growth, Density and the Costs of Providing Public Services.” Urban Studies 29 (2): 273–295.

- Mohr, R., S. Deller, and J. Halstead. 2010. “Alternative Methods of Service Delivery in Small and Rural Municipalities.” Public Administration Review 70 (6): 894–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02221.x.

- Nelson, M. 1997. “Municipal Government Approaches to Service Delivery: An Analysis from a Transactions Cost Perspective.” Economic Inquiry 35 (1): 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1997.tb01896.x.

- Pallesen, T. 2004. “A Political Perspective on Contracting-Out: The Politics of Good Times. Experiences from Danish Local Governments.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 17 (4): 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00258.x.

- Petersen, H., U. Hjelmar, and K. Vrangbæk. 2018. “Is Contracting Out of Public Services Still the Great Panacea? A Systematic Review of Studies on Economic and Quality Effects from 2000 to 2014.” Social Policy & Administration 52 (1): 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12297.

- Rodrigues, M., A. Tavares, and F. Araújo. 2012. “Municipal Service Delivery: The Role of Transaction Costs in the Choice Between Alternative Governance Mechanisms.” Local Government Studies 38 (5): 615–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.666211.

- Shrestha, M. K., and R. C. Feiock. 2011. “Transaction Cost, Exchange Embeddedness, and Interlocal Cooperation in Local Public Goods Supply.” Political Research Quarterly 64 (3): 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912910370683.

- Swarts, D., and M. Warner. 2014. “Hybrid Firms and Transit Delivery: The Case of Berlin.” Annals of Public & Cooperative Economics 85 (1): 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12026.

- Szmigiel-Rawska, K., J. Łukomska, and A. Tavares. 2021. “The Anatomy of Choice: An Analysis of the Determinants of Local Service Delivery in Poland.” Local Government Studies 47 (5): 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1777108.

- Tavares, A. F., and P. J. Camões. 2023. “Municipal Corporatisation in Portugal: From Mania to Depression.” In Corporatisation in Local Government: Context, Evidence and Perspectives from 19 Countries, edited by M. Van Genugten, B. Voorn, R. Andrews, U. Papenfuss, and H. Torsteinsen, 315–333. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Tavares, A., and P. Camões. 2007. “Local Service Delivery Choices in Portugal: A Political Transaction Costs Framework.” Local Government Studies 33 (4): 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701417544.

- Tavares, A., and P. Camões. 2010. “New Forms of Local Governance: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis of Municipal Corporations in Portugal.” Public Management Review 12 (5): 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719031003633193.

- Tavares, A., and M. Rodrigues. 2017. “The Same Deep Water As You? The Impact of Alternative Governance Arrangements of Water Service Delivery on Efficiency.” Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation 3 (2): 78–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055563617728744.

- Teles, F. 2016. Local Governance and Inter-Municipal Cooperation. (1sted.) UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Train, K. E. 2009. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Warner, M., and R. Hebdon. 2001. “Local Government Restructuring: Privatization and Its Alternatives.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (2): 315–336.

- Warner, M., and A. Hefetz. 2008. “Managing Markets for Public Service: The Role of Mixed Public – Private Delivery of City Services.” Public Administration Review 68 (1): 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00845.x.

- Wassenaar, M., T. Groot, and R. Gradus. 2013. “Municipalities’ Contracting Out Decisions: An Empirical Study on Motives.” Local Government Studies 39 (3): 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.778830.

- White, P. 1997. “What Conclusions Can Be Drawn About Bus Deregulation in Britain?” Transport Reviews 17 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441649708716965.

- Zafra‐Gómez, J. L., D. Prior, A. M. P. Díaz, and A. M. López‐Hernández. 2013. “Reducing Costs in Times of Crisis: Delivery Forms in Small and Medium Sized Local governments’ Waste Management Services.” Public Administration 91 (1): 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02012.x.

- Zafra-Gómez, J. L., L. E. Pedauga, A. M. Plata-Díaz, and A. M. López-Hernández. 2014. “Do Local Authorities Use NPM Delivery Forms to Overcome Problems of Fiscal Stress?” Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española De Financiación Y Contabilidad 43 (1): 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02102412.2014.890823.

- Zullo, R. 2009. “Does Fiscal Stress Induce Privatization? Correlates of Private and Intermunicipal Contracting, 1992–2002.” Governance-An International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions 22 (3): 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01447.x.