Abstract

This article discusses the history of textile exhibitions in Israel during the state’s first three decades, focusing on the seminal yet completely overlooked exhibition Works in Thread, held at the Israel Museum’s Design & Architecture Department in 1975. As this article shows, Works in Thread was an eclectic compilation of applied- and art-textiles, both hand- and machine-made, but it particularly highlighted the new medium of art textiles, or fiber art, known locally as “work in soft thread.” I argue that this exhibition serves as an archeological site that reveals multiple currents in the short history Israel’s textile production, particularly a process by which textiles and fiber works were gradually perceived as objects for aesthetic consumption rather than merely useful ones. By considering Works in Thread in its historical context, this article seeks to illuminate the multi-faceted sources for Israel’s early fiber art, and contextualize the local manifestation of of and the international studio craft movement.

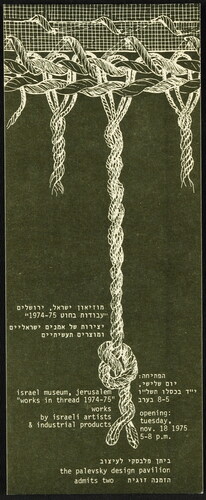

In November-December 1975, the exhibition Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artists and Industrial Products was presented at the Israel Museum’s Palevsky Pavilion, the center for the museum's Design and Architecture Department that opened in 1973. The exhibition was a joint initiative of the department’s director and chief curator, Yizhak (Izzika) Gaon, and the Israel Designers-Craftsmen Association (IDCA), founded in 1964 to promote Israeli craft. Despite its subtitle, the exhibition included very few industrially made objects and was rather dominated by non-functional textile works, namely, wall-hangings and soft sculpture made using various techniques (). This paper argues that Works in Thread was the first Israeli museum exhibition to showcase local manifestations of the international studio fiber movement that emerged in the 1960s, reframing fiber works as art rather than craft or design. In recent decades, scholars have recovered the history of the studio fiber movement, particularly during its defining decades of the 1960s and 1970s,Footnote1 yet discussion of this movement remains completely absent in the scholarship on Israeli art. By redressing this, I seek both to highlight a vibrant field of artistic production that has been overlooked in the historiography of Israeli art and add another perspective to the discussion of twentieth-century textile art as a truly global field.

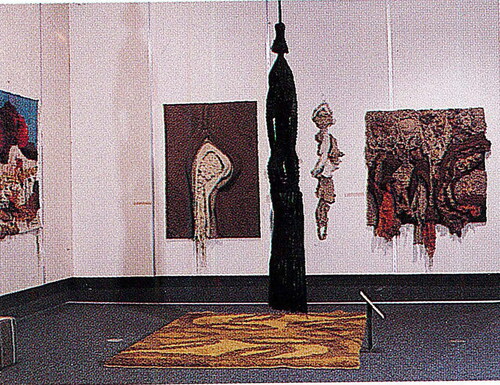

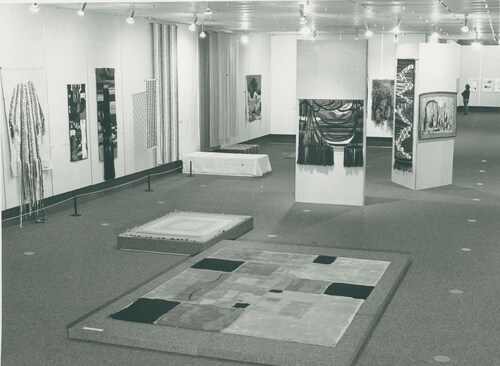

Fig 1 Installation view of Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artists and Industrial Products at the Palevsky Pavilion, Design & Architecture Department, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1975. Second left: Judith Bloch, Jerusalem #1 or #2; front: Tirtza Ozieli, Macramé in Black. Reproduced in Design and Architecture at the Israel Museum: Portrait of a Department, 1973–1997 (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1999). Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

To understand Works in Thread in its historical context, I first discuss the short history of textile displays in Israel since the 1940s, and then analyze the connection made between Israeli craft and the international studio craft movement in the 1960s, which stimulated new perceptions of textile art in Israel and lead to the establishment of the IDCA. Works in Thread was a culmination of a shift in local perceptions of craft as either applied or folk art, revealing the scope of a hardly recognized local field of art made from fiber materials. Yet, distinct from seminal fiber art exhibitions such as the 1969 Wall Hangings at the Museum of Modern Art, Works in Thread juxtaposed different categories of objects including artworks, rugs and applied textiles for home and fashion.Footnote2 Indeed, it is the inclusive character of the exhibition that makes it such a rich site through which to explore the early history of Israel’s field of art textiles, three decades in the making.

Israeli Textiles on Display: a Brief Survey

Works in Thread was the first exhibition dedicated to textiles and fibers at the Palevsky Pavilion. Though it preceded later textile exhibitions of different types, Gaon described Works in Thread as one of the few exhibitions showing a “limited number of unique hand-produced works.”Footnote3 The Design & Architecture department, inspired by other such departments worldwide, focused on high-end local and international design, and sought raise the level of Israeli design and its international recognition..Footnote4 The Pavilion’s opening exhibition, “Introduction to Design” was an extensive survey that included “Milestones in Modern Design” such as Le Corbusier’s reclining chair, an exhibit of the Italian firm Danze, and a section on Israeli architecture. Gaon, who joined the department after that exhibition and served as chief curator until his premature passing in 1997, continued this design focus with exhibitions of Scandinavian design and of the International Association of Graphic Designers. But he also organized visionary, groundbreaking exhibitions such as the 1973 Recycling, which consisted of “objects recycled from domestic and industrial trash.”Footnote5 Works in Thread, though originally conceived as an all-craft exhibition by the IDCA (as I detail later), reflected Gaon’s ability to spot significant yet still-emergent developments in fields adjacent to the department’s main design focus.

To understand Works in Thread, it is necessary to examine first the history of textile exhibitions in Israel up until that time. During the first two decades following Israel’s founding in 1948, the various ways in which textiles were displayed reflected the envisioned role of this medium in the consolidating culture of the nascent state. Industrially manufactured fabrics comprised Israel’s second largest industry and thus were displayed in commercial fairs and industrial shows. By contrast, traditional embroidery and weaving, primarily by recently-arrived Jewish immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa, were displayed in ethnographic exhibitions as a type of Jewish, and presumably Israeli folk art.Footnote6 And textiles handmade by individual designers or in small workshops were commonly featured in exhibitions of applied art held in museums and other venues, which often aimed to promote local design and stimulate the formation of a local Israeli style.Footnote7 The question of whether there was such a thing as a quintessentially Hebrew or Israeli aesthetics was foremost in the minds of many during this time, as artists and craftspeople of diverse cultures of origin sought to establish a new national culture. Israeli design, in particular, was shaped at its infancy by Central European modernism, brought to Israel by designers who escaped Germany in the 1930s and then helped to develop fields such as graphic design, ceramics, metalwork and textiles in the new state. The New Bezalel, a school founded in 1935 by a group of Central Europeans who studied at the Bauhaus and similar German schools, included a weaving department founded and directed by German-born Julia Keiner, who trained her students according to the principles of truth to materials and honest design based on the structure of warp and weft.Footnote8 Applied art exhibitions held during the 1940s and 50s at museums and other venues often featured textiles for interiors and fashion by Keiner and her students, alongside textiles handmade by individual designers or produced in small workshops primarily of kibbutzim and charity organizations.Footnote9

Such applied art exhibitions had only limited success in advancing the field of commercial textile design. However, I contend that they contributed to the aestheticization of a certain type of textiles, and to a new public perception of objects such as napkins and curtains as aesthetic objects made for pleasurable consumption—a perception otherwise alien to Israel’s ethos of frugality and austerity, particularly dominant during the 1950s-1960s. This attempt to distinguish some forms of textiles as pure art is exemplified in the curatorial statement of the 1958 exhibition Photography, Ceramics, Weaving, 1957–58 held at the Haifa Museum of Art in honor of Israel’s first decade. The weaving sections included rugs, tablecloths, and napkins by Keiner, her former student Neorah Warshavsky, and another weaver of similar style. The curators wrote: “In the craft of weaving one must discern between popular art, revived in recent years by immigrants from Oriental Countries, and the art of weaving for the sake of its own [my emphasis].”Footnote10 By distinguishing between traditional weaving by Mizrachi Jews, which the Hebrew text defined as “folk art,” and functionalist weaving based on German modernism, the curators not only revealed racial biases characteristic of the Israeli Ashkenazi hegemony at the time, but also positioned weaving in the latter category as more aesthetically elevated.

However, the textile traditions of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa, disparagingly alluded to by the Haifa Museum curators, were themselves redefined as part of Israeli modern identity. In 1954, Ruth Dayan, who would become Israel’s best known and arguably most exuberant craft advocate, founded Maskit, a state-owned company that operated under the Ministry of Labor and aimed to employ newly arrived immigrants in home industries based on ethnic craft traditions. Dayan spent time in England with her then-husband, Israeli general Moshe Dayan, where she learned about British craft and cottage industries. She believed the only way to create a profitable market that could support craft-makers was to use ethnic traditions in modern fashion and home goods. Dayan thus set about hiring professional designers, including several New Bezalel graduates to develop Maskit’s trademark line of clothing, jewelry and fabrics, who incorporated and adapted a variety of local ethnic traditions.Footnote11 In 1955, Village Craft, a large-scale Tel Aviv Museum exhibition of Maskit products included such items as rugs, jewelry, and clothing, as well as live demonstrations of traditional Yemenite-Jewish silversmithing and weaving.Footnote12 As art historian Yael Guilat has noted, Dayan was able to recruit the Tel Aviv Museum of Art—normally, a haven of modernist fine art—for such an exhibition reflects her own and Maskit’s prominence in the effort to define a quintessentially Israeli aesthetic.Footnote13

But it was specifically Maskit’s textile department that sowed the seeds for the organization’s eventual shift away from traditional methods and towards contemporary fine craft in the 1960s, as I discuss in the following section. In the early years, Maskit’s line of textiles included rugs adapted directly from the traditional style of Israel’s Yemenite- and Tunisian-Jewish communities. In addition, a small factory managed by George Kashi, an Iraqi-born specialist of English woven fabrics, manufactured twills for Maskit’s fashion department.Footnote14 The trademark style of Maskit fabrics changed significantly when dedicated departments for handwoven and printed textiles were founded in 1959 and 1960, respectively. The former was managed by New Bezalel graduate Neorah Warshavsky, mentioned above, who served as Maskit’s weaving designer for over three decades. Warshavsky worked with a selected group of skilled home weavers, and though she integrated some of their traditional methods into her designs, she was firmly grounded in the modernist methods and perceptions she absorbed from Keiner.Footnote15 Her designs were characterized by intricate, conspicuous textures, achieved through a combination of different types of fibers, as demonstrated in a fashion fabric that she first made of wool and leather straps and later reproduced using silk ribbons and other materials (). As Maskit’s head weaver, Warshavsky focused on textiles for fashion and interiors, but, as I discuss below, she would also become a key figure in promoting Israeli art textiles.

Fig 2 Neora Warshavsky for Maskit, handwoven upholstery fabric sample, wool and leather ribbons, 1965/1970. Photograph: Ran Erde.

Unlike the company’s weaving department, Maskit’s printed textile department commissioned designs from a broad range of lesser- and better-known artist-designers, and outsourced manufacturing to an independent printed textiles factory. A similar roster of artists-designers contributed designs for the hand-knotted rug workshop established in the Arab town of Um-El-Fahen, which continued Maskit’s original mission of providing employment through handicraft, but was not based on any local, traditional technique.Footnote16 In this way, Maskit’s rugs and printed textile departments nurtured and supported a growing roster of makers working at the boundary of art, craft, and design. Though designing for these departments did not require textile-making knowledge, some of the most prominent designs were created by artists whose studio work encompassed fiber techniques such as batik, weaving, and appliqué—in styles that reflected new concepts of art-craft and art-textiles that developed in the international arena during the 1960s.

Maskit, the WCC, and the Israel Designers-Craftsmen Association

Maskit is arguably the most extensively studied chapter of Israel’s design history.Footnote17 Yet existing historical narratives overlook a key dimension of the organization’s history, namely, its connection with the World Craft Council (WCC) and its local chapter, the Israel Designers-Craftsman Association, which paved the way for a new mode in Israeli craft. New perceptions of craft as an individual, creative practice more akin to art emerged in the United States in the 1960s, stirring a massive movement institutionally supported by philanthropist Aileen Osborn Webb.Footnote18 As Sandra Alfoldy has shown, the agenda of Webb and other prominent leaders of American studio craft was to rebrand craft as a form of modern art instead of a traditional practice or applied art.Footnote19 In the US, Alfoldy argues, Webb’s “awareness of modernist aesthetics led to the financial support of a unique approach to making within the US craft community, one that stressed innovation, technical experimentation, and the privileging of the conceptual over the traditional and the utilitarian.”Footnote20 After energizing and reshaping American craft though institutions such as the Museum of American Craft and the American Craft Council, Webb initiated the First World Congress of Craftsmen that convened in New York in June 1964 and invited craft leaders from around the world to organize national delegations. “The emphasis throughout the Congress,” Webb wrote in retrospect, “was largely on design and education and the need of art content in the work of craftsmen.”Footnote21 The second newsletter of the WCC, incorporated immediately after the Congress, sought to distinguish between the artisan-craftsman who masters manufacturing, and the designer-craftsman who produces his own design.Footnote22 The international fiber art movement, while having its own particular history (discussed below), was part of this new perception of craft as a form of art. Maskit’s involvement with the WCC directly reshaped the organization’s agenda and contributed to a new type of craft, and art textiles, in Israel.

Dayan, as Maskit’s director, was invited to form an Israeli delegation to the Congress and grouped together a cohort of six accomplished craft-artists working in various media. This group became founding members the Israel Designers Craftsman Association (IDCA), an affiliate of the WCC. The IDCA included practitioners in the fields of fibers, ceramics, metal and glass, and aimed to support Israeli craft locally and abroad. Ceramicist Chana Harag Tsunz was elected first chair of the Association, while Warshavsky served as secretary and Dayan (though not a craftsperson herself) was a board member.Footnote23 Both Warshavsky and Dayan regularly represented Israel in WCC meetings during the 1960s–1980s, and the latter was a regular speaker at the Congress.

The practical and ideological links between Maskit and the IDCA were on display at Maskit 6, a gallery founded in 1966 at the Tel Aviv flagship store, which functioned as Israel’s first venue dedicated to art-craft, including various forms of art textiles. The opening exhibition was of printed fabrics by members of the avant-garde art group Ten + led by conceptual artist Rafi Lavie. Although they were presented as fashion fabrics, the exhibition marked a radical break from Maskit’s focus on both home industries and commercial fashion shown in Village Craft only a decade earlier.Footnote24 Several of the artists who regularly contributed to Maskit’s commercial lines also made non-functional art-craft that was shown at the gallery. A prominent example is Shula Litan, a self-taught weaver, appliqué and batik artist, who later trained and specialized in paper casts, and began designing printed fabrics for Maskit in 1961. Litan was particularly renowned for her meticulously made and highly skillful appliqué works, which were abstract but often dealt with issues stemming from her personal biography (). A 1969 article in Craft Horizon described her as a “master of positive-negative space,” and her appliqué works as “eye stoppers.” Her work was featured in the 1974 seminal exhibition In Praise of Hands, organized as part of the WCC meeting in Toronto.Footnote25 Anna Kralove, in contrast, was a lace artist Dayan discovered and promoted through Maskit 6 and in her various publications on craft and textiles, though she did not design for Maskit’s commercial departments. Born in Czechoslovakia, Kralova immigrated to Israel in 1965, and created lace works in the contemporary Eastern European style more famously associated with Luba Krejci. Examples of the type of textile works showcased in Maskit 6 can be found in the 1968 exhibition Dividers, which featured room dividers made especially for the exhibition in techniques such as lace, weaving, batik and an assemblage of objects bought at the flea market. All items were for sale, but, according to one reporter, were priced beyond the average consumer’s reach, leading her to wonder whether they could be industrially manufactured at more reasonable prices.Footnote26

The program at Maskit 6 thus blurred the boundary between functional and non-functional objects, providing a stage for studio craft practitioners to experiment with one-of-a-kind pieces not catered to the commercial market.Footnote27 It represented a new mode of art-craft that diverged from earlier applied art exhibitions dominated by the functionalist style of German-born designers, but also from the field of industrial design that emerged in Israel during in the 1960s and took over Bezalel, which by 1965, had become an Academy of Arts and Design. Together, Maskit and the IDCA sought to carve a distinct space for Israel’s art craft. But while the Maskit 6 gallery regularly showcased works made in thread, it was the 1975 Works in Thread exhibition that revealed for the first time the full scope of the field in Israel, and its diverse sources and styles.

Works in Thread: Art Textiles at the Forefront

Beginning in 1972, the IDCA began to advance the idea of a broad museum exhibition of its members’ work. After attempts to hold the exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art failed, Warshavsky, in her role as IDCA secretary, and metalsmith Aryeh Ofir approached Gaon, who agreed to organize a large-scale exhibition of contemporary Israeli craft at the Israel Museum’s Palevsky Pavilion, but emphasized that it could not be limited to IDCA members only. It was decided that a jury comprised of Israel Museum staff and one IDCA representative would select works made in the previous two years and planned works based on artists’ portfolios.Footnote28 Although the IDCA and Warshavsky, in particular, assisted Gaon to raise funds for the show and liaised between him and the craft community, Gaon and the museum took full autonomy over the exhibition’s concept and organization.

In January 1975 Gaon notified Warshavsky and Ofir that due to budgetary constraints, the exhibition could no longer be a general craft exhibition, but would have to be limited to two fields only—specifically, “all types of work in threads, weaving, embroidery, knotting etc…” as well as “precious metals.”Footnote29 Worried still about the quality of the exhibits, Gaon wrote to Warshavsky in July 1975 and asked her to reach out to more artists and institutions. “The interest of the museum and of the Association, I hope,” he wrote, “was to reach out and show works of craft of particular interest and high professional quality.”Footnote30 Gaon’s concerns about quality may have been a realistic assessment of the small scope of skilled and sophisticated practitioners in these fields, but they also reflected the unprecedented decision to showcase this type of work in such a central museum, even within its design department. Indeed, tensions eventually arose between the IDCA and the museum around this question of quality. The jury for the precious metals section, which included Israel Museum director Martin Weil and chief curator Elisheva Cohen, found the submissions unsatisfactory. It was decided to drop the precious metals section from the show altogether, which infuriated the IDCA’s metal artists.Footnote31 Meanwhile, the “threads’ jury, which also included Weill and Cohen, as well as the museum’s contemporary art curator Yona Fisher and textile designer Ruth Sternshos representing the IDCA, selected thirteen artists out of thirty who submitted independent works, in addition to six hand-knotted rugs each designed by different artists for Maskit. Consequently, the exhibition was redefined as an extensive display of works made in soft thread, with the jury agreeing that Gaon could add works as he saw fit by artists not among the original submitters. Footnote32 In this way, Gaon eventually doubled the number of works in the exhibition and was thus instrumental in shaping its final vision and premise as the most significant and varied compilation of locally-made textiles ever shown in an Israeli museum.

Works in Thread was a highly eclectic exhibition that included functional and non-functional textiles, studio-made rugs, hand-and machine-made fabrics for home and fashion, and traditional tapestries.Footnote33 But the largest category was comprised of studio-made wall hangings and fiber works rendered through diverse techniques such as weaving, tapestry, embroidery, appliqué and macrame, and created not only by highly skilled practitioners, but also by artists without textile backgrounds experimenting with the medium. The exhibition revealed Israeli artists’ participation in the broader international fiber art movement and its new approach to art made in threads. By 1975, this movement was hardly new—indeed, it already included over a decade of experimentation with practices such as off-loom weaving and fiber sculpture that emerged in the Lausanne Biennials of the 1960s and featured at exhibitions such as MoMA’s Wall Hangings, and the Stedelijk’s Perspectives in Textile in 1969. Works by the American Sheila Hicks and Polish Magdalena Abakanowicz were highlighted in those exhibitions as exemplifying new approaches that stretched the boundaries of fiber into the expanded field of sculptural work, while the American Lenore Tawney used complex weaving techniques for both two- and three-dimensional poetic fiber constructions. Footnote34 The works by Israeli fiber artists exhibited in Works in Thread did not yet embrace monumentality, but many of the wall hangings in the show challenged the flat, pictorial tapestry form in a way that was clearly grounded in these new international developments.

Indeed, for several artists in the exhibition, these “new” approaches to fibers resonated with the structuralist weaving methods developed at the Bauhaus and other German Schools, on which the New Bezalel’s weaving department based its pedagogical agenda. Ruth Kaiser, who graduated from the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop in 1932 and immigrated to Palestine in 1935, succeeded Keiner and directed the department from 1963 until it closed in 1970. Over her long career, Kaiser managed weaving cooperatives and designed functional fabrics in the structural style she later taught at the New Bezalel, but by the 1960s her private practice focused primarily on large tapestries depicting Jerusalem’s mountainous landscape.Footnote35 For Works in Thread, four of her tapestries were centrally placed at the middle of the gallery (). She described one, titled Jerusalem Mountain, a multi-level mountainous landscape in natural tones of off-whites, greens, and browns as “an expression of the character of landscape through the handling of materials and use of texture.”Footnote36 Works seen in installation views as well as her similar extant works demonstrate how Kaiser balanced figuration with technical experimentation and medium specificity, by distinguishing elements through structural patterns of different depths and textures, thus adding a three-dimensional layer to the work. The texture in Kaiser’s work was also the result of combining different threads that she spun and dyed herself to produce idiosyncratic colors.Footnote37 Her tapestries engaged with and drew from her local surroundings, but their ethereal quality can be traced to the influence of Kandinsky, with whom she took a course in “analytical signs” while at the Bauhaus.Footnote38

Fig 4 Installation view of Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artists and Industrial Products at the Palevsky Pavilion, Design & Architecture Department, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1975. Front: two tapestries by Ruth Kaiser. Photograph: Reuven Milon.

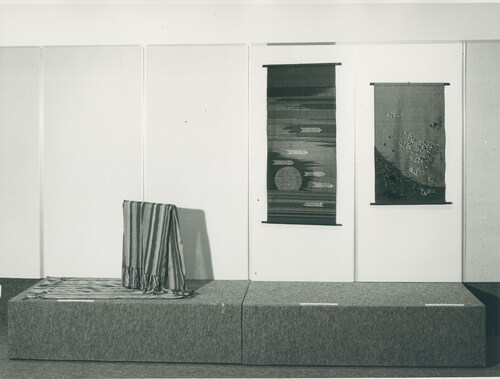

Several scholars have pointed out the direct impact of Central European weavers of the Bauhaus generation on new forms of art textiles that emerged in the 1960s, particularly through key émigré designers such as Anni Albers, Marli Eherman and Trude Guermonprez, who served as educators in key fiber departments in the United States.Footnote39 Kaiser and her predecessor Julia Keiner similarly passed their modernist design perceptions to the next generation of weavers who became part of this transnational inter-generational lineage. Like Kaiser, Keiner had immigrated from Germany, where she studied weaving design at the innovative Kunstschule Frankfurt. Keiner’s prolific career focused on handwoven textiles for interiors, and she taught her students the principles of functionalist design derived from material and technique, as well as color theories based on the natural environment.Footnote40 Most New Bezalel graduates who developed a professional weaving practice focused, like Keiner, on applied textiles. But by the 1970s, some were inspired by new ideas of art-craft to create wall hangings that applied structuralist methods to non-functional objects. Keiner moved to the United States in 1964 and did not submit any of her own work to the 1975 exhibition, but four of her former students were accepted by the jury and presented both applied and art textiles. Warshavsky, arguably the most renowned, showed several of her most popular fashion fabrics for Maskit, but also her first-ever wall-hanging, a hand-dyed and loosely hand-woven construction in black and white that echoed her style of “op-art” patterned fabrics. Ziva Amir contributed a shawl as well as two wall hangings that integrated complex woven structures with found natural objects such as feathers and bamboo sticks, inspired by Japanese art that Amir studied and collected ().Footnote41 Rina Milon was the only graduate whose work, a tablecloth, was highly faithful to the signature New Bezalel style of monochromatic, meticulously made structural weaving.

Fig 5 Installation view of Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artists and Industrial Products at the Palevsky Pavilion, Design & Architecture Department, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1975. Front left: shawl, Ziva Amir, Red Sun, Scroll with Peacock Feathers. Photograph: Reuven Milon.

Hanna Rosen was distinguished among the department’s graduates by her practice dedicated solely to art textiles. With her husband Shlomo Rosen, who studied graphic design at the New Bezalel, she created both flat figurative tapestries featuring biblical themes, often made for commissions, but also abstract, woven pieces made “in the modern free form,” as she described them.Footnote42 As can be seen in an installation view of the Rosens’ 1976 solo show at Jerusalem’s Debel Gallery, their wall hangings break the traditional tapestry shape, and while rather flat, they are hung in some distance from the wall to accentuate their three-dimensionality (). These works are assemblages of elements made through distinctly different techniques, including tapestry weaving, loosely hung threads, and low relief, echoing Lenore Tawney’s woven constructions. Unfortunately, only one work of the four the Rosens contributed to Works in Thread is documented—a tapestry titled A Coat of Many Colors (a take on the Biblical story of Joseph and his brothers) made with a wool, cotton, silk and sisal background and a wool and sisal warp. This coat-shaped wall hanging is a suggestive gesture to the Biblical drama, displaying an orderly and balanced composition of woven stripes of different structure and thickness.Footnote43 In an interview held in honor of their 1976 solo show, Hanna emphasized the distinction between a master weaver who creates someone else’s design, and the “artist-weaver” who feels “an inner urge to say something of their own through threads and a loom.” Echoing both the values of the studio craft movement and her modernist, functionalist training, Rosen described her works as derived from the specific threads she used, but unlike her student works, she framed her newer works as “autonomous objects” rather than useful ones. She nevertheless linked her practice directly to her training, saying that “some of the teachers were graduates of the famous Bauhaus… and it was clear that weaving could be art. They did not perceive it as a women’s hobby.”Footnote44 She lamented the fact that since the department’s closure in 1970, weaving was no longer perceived as art in Israel, though she did point to Works in Thread as a milestone that stimulated new forms of art weaving.

Fig 6 Installation view of Hanna and Shlomo Rosen, Weavers, Debel Gallery, Jerusalem, 1976. Photographer: Reuven Milon.

While different, works by the New Bezalel group demonstrated a rather unified set of stylistic and conceptual principles, based in the ideas of material- and process-specificity and a high level of skill, other works in Works in Thread broke with the flatness of traditional wall hangings as well as with the meticulous technicality of the New Bezalel style. Gaon enhanced the experimental character of the exhibition by adding works of such artists as Nora Frankel, a self-taught weaver and reputable painter who trained at Cooper Union before moving to Israel. Frankel’s wall hangings lacked the dexterity of Warshavsky’s or Rosen’s works but demonstrated more liberated use of the loom. Her squarish yet asymmetrical constructions were roughly woven, conveying three-dimensional motifs through knotting and looping that seemed to jump from the background. Though completely abstract, her works had referential titles like The Wedding or a View of Provence, as well as Homage to Sheila, a tribute to fiber art superstar Sheila Hicks (). Another work added by Gaon was a freestanding macramé sculpture by Tirza Ozieli, who is little known today (). Hung from the ceiling, Ozieli’s work manifested a highly non-traditional, liberated treatment of a medium largely associated with low-brow, hobbyist art (, center front).

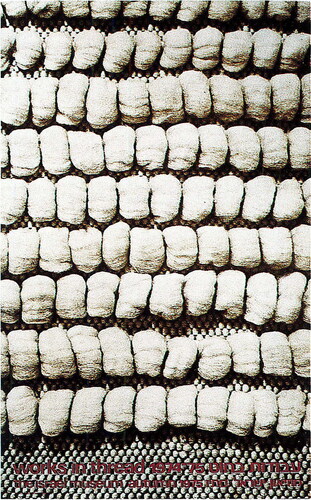

Yael Gelles, whose work was selected by the jury, was similarly a self-taught weaver whose textured wall-hangings—some monochromatic, some brightly colorful—were in high demand among interior designers and private clientele. Judith Bloch, in contrast to Gelles and Frankel, studied textile and art at the Kunstgewerbeschul Zurich before immigrating to Israel, though little else is known about her career and biography.Footnote45 Two of the three works she contributed to Works in Thread—titled, respectively, Jerusalem # 1, 2 and 3—were highly skillful, three-dimensional wall hangings made in crochet and looping using wool and linen, containing semi-abstract, sensual motifs alluding to bodily organs (, back wall on left).Footnote46 Her third piece was a felt relief she defined as a ‘soft sculpture,’ composed of a conspicuous frame that enveloped rows of perfectly round balls (). Though Bloch was selected by the jury, it was Gaon who chose a photograph of this piece as the only image to appear in the exhibition brochure. Although Bloch’s work was rather small, the close-up photograph in the brochure rendered it seemingly monumental thus emphasizing its material sensuality and sculptural quality (). Such visual manipulations enhanced the exhibition’s emphasis on expressive, experimental fiber works.

Fig 8 Exhibition brochure cover, Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artist and Industrial Products at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1975. Reproduced in Design and Architecture at the Israel Museum: Portrait of a Department, 1973–1997 (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1999). Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Fig 9 Installation view of Works in Thread: Works by Israeli Artists and Industrial Products at the Palevsky Pavilion, Design & Architecture Department, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1975. Photograph: Reuven Milon.

Other notable artists included Litan, who exhibited four appliqué works; and Ruth Cidor, who studied briefly at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop and presented a collage of woven pieces.Footnote47 At the same time, the exhibition also included many applied textiles, both hand- and machine-made. Gaon added a section of textiles designed for industrial manufacturers, such as a bed cover by Tamar de Shalit for textile company Etun, and fabrics designed for the fashion brand Rikma. Levita Tadmor, a textile designer and the owner of a small workshop for machine-made fashion fabrics made after her handweaving designs, contributed various fabrics. This category was a good fit for the department’s overall focus on industrial design, and may have been added to draw the support of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, which ultimately provided funding for the exhibition.Footnote48 In an interview he gave shortly after the exhibition opened, Gaon stated that he had hoped to include other pieces manufactured in some of Israel’s large factories such as Polgat and Kitan, but found none that he thought to be aesthetically worthy. Nevertheless, Gaon explained that artistic quality was not the only factor determining what was included, for the exhibition aimed “to provide a representation of everything going on today in the field of work in soft thread,” and “to encompass the different and almost unlimited possibilities of using threads for art and industrial products, that has an artistic motif.”Footnote49 He further elaborated: “It was enough for it to have something special and unique, that would reveal something about the potential of thread, from a perspective unseen in other works. Difference stimulates creativity, and I would like to see more and more people engaged in thread art, which is so primal and diverse.”Footnote50

Gaon’s realistic assessment of Israel’s fiber and textiles art at the time affirms Works in Thread as a momentous recognition of a field that was still in its infancy but quickly developing in new directions grounded in local history and recent international trends. Paradoxically, the inclusivity of the exhibition also defied conventions of fiber art exhibitions, which distinguished fiber from traditional craft or applied art, and aspired to elevate fiber art to the status of so-called pure art. The installation itself embodied this inclusive approach, showing textiles both hung on a wall or from a ceiling, and laid on the floor or a table, modes of display conveying very different associations of “high” and low” (). The invitation to the exhibit similarly emphasized materiality over a specific type of end-product by featuring a drawing of an unidentified construction of woven and looped threads, rather than any specific work ().

Conclusion: the Impact of Works in Thread

Works in Thread was unique in bringing together textiles and fiber works of various types, but its greatest significance was its large concentration of wall hangings and soft sculpture, a medium that was hardly known or acknowledged locally prior to that show. The Works in Thread exhibition file in the Israel Museum archive contains only three articles reviewing the exhibition, suggesting the show received little media attention at the time, and even today, the exhibition seems to have fallen out of Israel’s art historical narrative. Ironically, this elision likely relates to precisely what I contend made the show so important, namely, its assemblage of works that existed in a liminal state ‘in between’ art, craft, and design. As Elissa Auther notes, despite the fact that fiber artists during the 1960s-1970s challenged the boundaries between art and craft, they were not perceived at the time as part of the groundbreaking boundary-crossing practices of other artistic movements, but were relegated instead as “neither art nor craft.”Footnote51 Similarly, Works in Thread and the artists in it, including those who had prolific careers in the fields of textiles and fiber art, did not fit easily within the common definitions of either Israeli contemporary art or Israeli fashion and design history.

There is evidence that Works in Thread nonetheless made an important impression on those engaged with the field of fiber art. In a letter sent by Israel Museum board member William Sanberg to Max Palevsky, patron of the Design and Architecture department, Sanberg wrote that he found the exhibition “revealing” and welcomed the discovery that “much better things are being made in Israel than you see on official shows.” He added that Gaon must have worked hard to “assemble so many good pieces.”Footnote52 Sandberg was an ardent advocate of the international studio fiber movement in his role as director of the Stedelijk Museum and involvement with the Lausanne Biennale, but by no means involved with the exhibition. His impression reflected both the links and the gaps between the local and international fields of fibers, and he proposed to amend these gaps by bringing artists such as Abakanowicz or Hicks to Israel to connect local artists with recent developments in the US and Eastern Europe, asking if Palevsky would sponsor the effort. It is unclear whether Sanberg acted as a liaison, but Hicks sent a card to Gaon congratulating him on the show and requesting a catalogue (there was none, only the thin brochure, mentioned above). Five years after Works in Thread, Gaon curated Hicks’s solo exhibition Free Flow at the Palevsky Pavilion. This extensive exhibition was based on Hicks’ visits to Israel between 1978–1980, during which she connected with local artists and craftsperson’s in the textile field, some of whom she invited to take part in the exhibition, which also included a series of satellite exhibitions of Israeli textile art and craft in small, peripheral venues. In the Free Flow catalogue, Gaon referenced Works in Thread, stating that it “was followed by a significant new awareness of the field [of Israeli fiber art] among producers and consumers, who subsequently begun to cultivate and develop new sources of material.”Footnote53

Hardly anything has been written on Israeli fiber art created during the last decades of the twentieth century. Yet archival material and interviews I conducted with fiber artists reveal that the 1980s and 1990s were a golden age of activity in this field. “Omanut Sivim,” the literal Hebrew translation to fiber art coined in the 1980s, was exhibited during those decades in galleries dedicated to craft and fiber art, galleries in small colleges, and other venues outside Israel’s mainstream artworld.Footnote54 Works in Thread not only preceded, but stimulated this development by helping artists develop a sense of belonging to the growing field of fiber art. That the next museum exhibition to feature a survey of Israeli textile art did not occur until 2014, at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv, establishes the 1975 exhibition as a singular event in the history of Israeli art, one that put a formative institutional spotlight on an otherwise marginalized field.

Acknowledgement

The research for this article has receive funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant Agreement no. 889568, held at the Hebrew Univeristy of Jerusalem between 2020-2022. I'm grateful to Prof. Tamar Elor for her guidance and support, and to Dr. Sandrine Canac for her insightful comments on this article. I would also like to thank the peer reviewers and the editors of the Journal of Modern Craft.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Noga Bernstein

Dr. Noga Bernstein is a faculty member at the Faculty of Design & Architecture, SCE-Sami Shamoon College of Engineering and Visiting Researcher at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. A scholar ofmodern craft, art and design in Israel and the United States, her articles appeared in American Art and Journal of Design History. Noga's study of Israeli textiles after the 1940s was supported by a a Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellowship, and her work was awarded grantsfrom the Smithsonian Institution, the ACLS and the Center for Craft.

Notes

1 The quickly expanding literature on the international studio fiber movement includes, for example: Elissa Auther, String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art (Minnesota University Press, 2009); Cynthia Fowler, “A Sign of the Times: Sheila Hicks, the Fiber Art Movement and the Language of Liberation,” Journal of Modern Craft, 7, no. 1 (2014): 33–51; Emilia Teracciabo, “On Being Crafty: Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Sleight of Hand and the Politics of Fiber Art (1977-94),” Oxford Art Journal, 43, no. 1 (2020): 1–23.

2 Jenni Sorkin, “Way Beyond Craft: Thinking Through the Works of Mildred Constantine,” Textile: Cloth and Culture 1, no. 1 (2003): 29–47.

3 Izzika Gaon, “On the Exhibition and in General,” Free flow: Sheila Hicks at the Israel Museum (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1980). Following Works in Thread, the department held an exhibition of American Quilts (1977), Israeli Industrial Fabrics (1978), and a solo exhibition of Sheila Hicks (1980).

4 The department was the brainchild of William Sandberg, the Dutch graphic designer who was on the Israel Museum board and sponsored through contribution from Max Palevsky. Teddy Kollek, note in Introduction to Design: The Opening Exhibition of the Palevsky Design Pavilion (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1973).

5 Design and Architecture at the Israel Museum: Portrait of a Department, 1973-1997 (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1999), 31.

6 Noa Hazan, Visual Syntax of Race: Arab Jews in Zionist Visual Culture (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2022). Ayala Raz, 100 Years of Israeli Fashion (Yeidot Achronot, 2002); Yaakov Shavit, The Textile Industry in Eretz Israel, 1854–1956 (Israeli Textile Association, 1992); Yaakov Shavit, The Textile Industry in Eretz Israel, 1854–1956 (Israeli Textile Association, 1992).

7 For example: Mordechai Ardon, “On the Applied Art Exhibition,” Mishmar (September 5, 1946); “The New Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts,” Zionist News-Letter (Published by the Jewish Agency and the WZO, January 21, 1949).

8 Ibid. Noga Bernstein, “Julia Keiner's Universalism and the Search for an Israeli Style,” forthcoming in the Journal of Design History; Gideon Ofrat, The New Bezalel (Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, 1997). Izika Gaon, Julia Keiner: Weaving and Collages (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1993).

9 The Bezalel National Museum, a separate institution from the school, held applied art exhibitions in 1941, 1944, 1946 and 1956. Other exhibitions were held at the Israel Product Design Organization gallery, the Orient Fair, and the Haifa Museum of Art, as discussed below. See: Julia Keiner file, the Israel Museum Center for Israeli Art; Neorah Warshavsky Digital Archive, The Israel National Library.

10 Photography, Ceramics, Weaving, 1958 (Haifa Museum of Art, 1958)

11 Ruth Dayan and Wilburt Feinberg, Craft of Israel (London: Macmillan, 1974); Batia Donner, Maskit: A Local Fabric (Tel Aviv: the Eretz Israel Museum, 2003).

12 The critique of Village Craft as reflecting institutional racism, precisely in its live demonstrations, is discussed in Yael Guilat, “Social Practices, Production Spheres and Jewelry Design in Maskit’s Silversmithing Department,” Thoughts on Craft (Jerusalem: Bezalel Acadmey of Art and Design): 237–41.

13 Ibid.

14 Donner, Maskit, 9–31.

15 Author’s interview with Warshavsky, January 15, 2021.

16 Donner, Maskit, 37–45.

17 For example: Donner, Maskit; Tamar El-Or and Moti Regev, “The Construction of an Israeli Style, 1967–1973,” in Israel 1967–1977: Continuity and Transformation (Ben-Gurion Institute, 2017), 308–33; Yael Gilat, “Embroiderers of the Nation: Women's Organizations as Folk Art Patrons,” in Ruth Markus, ed., Women Artists in Israel, 1920-1970, 181–224; Shelly Shenhav, “The Israeli Souvenir: its Text and Context,” Annals of Tourism Research, 20 (1993): 182–96.

18 Ellen Paul Denker, “Aileen Osborn Webb and the Origins of Craft’s Infrastructure,” Journal of Modern Craft, 6, no. 1 (2013): 11–34.

19 Sandra Alfoldy, Crafting Identity: The Development of Professional Fine Craft in Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005).

20 Ibid., 55.

21 World Crafts Council, A Newsletter Report (June 12, 1964); emphasis mine.

22 World Crafts Council, A Newsletter Report (December, 1964).

23 Interview with Warshavsky. Letter from Shimoni (Ministry of Commerce) to Avigad (Ministry of Education), (August 9, 1966), Israel National Archive: ISA-education-EducationalInstit-000ff8t.

24 Donner, Maskit, 47–50.

25 Kay Whitcomb Keith, “Stutgart: International Handcraft,” Craft Horizons 29 (September/October 1969): 5, 21. CV, Shula Litan file, Information Center for Israeli Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

26 Tz. K. “‘Dividers’ Exhibition at Maskit 6,” Lamerhav, 2, no. 1 (1967): 3.

27 The organization was also rebranded by changing its name from “company for cottage industries” to Israel’s Center for Craft.

28 Warshasky to Gaon, meeting’s summary (October 16, 1974), box 325, #211435. Israel Museum Archive (hereafter IMA).

29 Gaon to Ofir (January 6, 1975), box 325, #211435, IMA.

30 Gaon to Warshavsky (July 30, 1975), box 325, #211435, IMA.

31 Sara Harel to Warshavsky (September 11, 1975); memo, meeting of the jury for precious metal exhibition, design department (September 3, 1975), box 325, #211435, IMA.

32 Memos, meetings of the jury for weaving and works in thread for craft exhibition (September 2, September 8, 1975), box 325, #211435, IMA.

33 Works in Thread, full list of exhibitors, titles and techniques, box 325, #211435, IMA.

34 Glenn Adamson, “The Fiber Game,” Textile: Cloth and Culture 5, no. 2 (2007): 154–77; Victoria Anastasyadis & Marjan Boot, “Perspectives in Textile (1969) at the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum: A Landmark Exhibition,” The Journal of Modern Craft 12, no. 3 (November 2020): 265–73; Auther, String, Felt, Thread; Sorkin, ‘Way Beyond Craft.”

35 Magdalena Droste, et al., Gunta Stölzl - Weberei am Bauhaus und aus eigener Werkstattl, (Zurich: Museum für Gestaltung, 1987): 173–5.

36 Box 325, #211435, IMA.

37 Author’s interview with Yehuidt Katz, (April 16, 2021).

38 Droste, et al., Gunta Stölzl, 174.

39 Auther, Strong, Felt, Thread, xxiii-xxiv; Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenore Larsen, Beyond Craft: The Art Fabric (New York: Van Nostrand, 1972), 23–7; Sorkin, “Way Beyond Craft”; Sorkin, “Tactile Beginning” in Barbara Kasten: Stages (Zurich: JPR-Ringier, 2015), 153.

40 Gaon, Julia Keiner

41 Author’s interview with Dan Amir [ADD DATE?].

42 With the Exhibition Hanna Rosen – Shlomo Rosen, Weavers, Debel Gallery, Ein Karem, Hanna and Shlomo Rosen file, Information Center for Israeli Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

43 A photograph is also held at the Hanna and Shlomo Rosen file, Information Center for Israeli Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

44 With the Exhibition Hanna Rosen – Shlomo Rosen, Weavers.

45 Miniatures (Tel Aviv: Alefh Gallery, 1980)

46 Works in Thread, full list of exhibitors, titles and techniques, box 325, #211435, IMA.

47 Ibid.

48 Correspondence between Gaon, Warshavsky and Ezra Sasson regarding funding is in box 325, #211435, IMA.

49 Tzipora Roman, “Art in Soft Thread,” Yediot Aharonot (November 27, 1975).

50 Ibid.

51 Auther, String, Felt, Thread, 6.

52 Sandberg to Palvesky, 29.12.1975, box 325, #211435, IMA.

53 Gaon. “On the Exhibition and in General.”

54 Many exhibition catalogues are held at the Information Center for Israeli Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.