Abstract

The late Tom Lodge’s magisterial Red Road to Freedom will surely become the standard text on communism in South Africa, definitively re-assessing the sociological development and historiographically-contested political arc of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). The book, nevertheless, is squarely focused on the South African public realm, eliding the important private experiences of individual CPSA members and significant transnational interchanges with the broader Southern and Central African region. Early CPSA leaders were often strikingly restrictive about the kinds of relationships available to members; had a complicated, often hostile, relationship with immigrant workers; and were opposed to organising across colonial borders. For marginalised groups, these examples prompt difficult questions about what ‘freedom’ meant to communists and where the early CPSA’s Red Road was ultimately headed to.

In August 1945, Joseph Kumalo, an incensed Zulu resident of Western Native Township, on the outskirts of Johannesburg, threatened “to make war on all Nyasaland people.”Footnote1 He alleged that his wife, Rebonie Kumalo, had run off with their children, and was having an affair with a Zambian township resident, Thomas Kazembe. The Rand-based Nyasaland Native National Congress (NNNC) were ordered to intervene, or face the consequences. This was no idle threat of violence. Anti-immigrant riots had swept through Western Native Township and neighboring Newclare in 1927, killing 6 and injuring 25.Footnote2 Public meetings of Central Africans were restricted for fear of further reprisals.Footnote3 And Kumalo himself could draw on considerable support as local leader of the Vigilance Association, the African National Congress (ANC), and the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA).

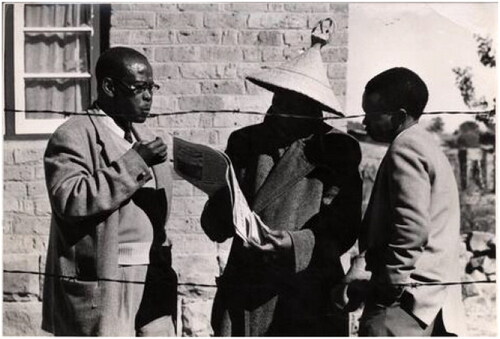

Joseph Kumalo (left) with other Communist Party and ANC refugees in 1960s Lesotho (Wits Historical Papers and the South African Institute of Race Relations).

Kumalo makes a very brief appearance in the late Tom Lodge’s magisterial Red Road to Freedom as a rent-striker, demonstrating the CPSA’s increased influence within urban African organizations during the 1940s.Footnote4 But the few available sources on Kumalo indicate that his revolutionary consciousness was otherwise narrowly defined by patriarchy and nation. Red Road to Freedom represents a formidable achievement, and will surely become the standard text on communism in South Africa, definitively reassessing the party’s sociological development and historiographically-contested political arc. The book’s focus, nevertheless, is set squarely within the bounds of the South African state, and while important connections to Britain, Australia and Eastern Europe are illuminated, it does little to situate the party within the broader Southern and Central African region. The threats of a CPSA member against Malawians and Zambians, in turn, invites a reconsideration of the early party’s history from a regional perspective, and opens up broader interconnected questions about the freedom to move, organize and love – questions which remain niggling and half-answered in my own research on early 20th century Southern Africa and the life of Clements Kadalie, an immigrant from colonial Nyasaland (modern-day Malawi) who organized vast numbers of workers under the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union of Africa (ICU) in the 1920s; challenged respectable norms around sex, love and drink; and had an uneasy relationship with the early CPSA.Footnote5

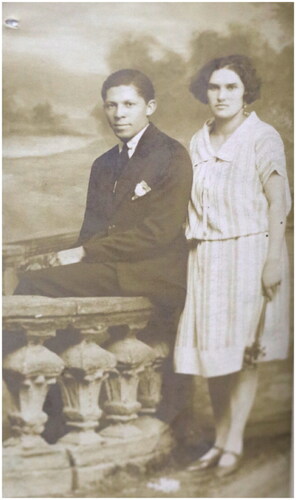

Lodge doesn’t dwell on the topic of love, but he does mention the party’s multiracial social events, the numerous mixed-race relationships between party members, and how CPSA leaders had to constantly bat away heckles about the interlinked dangers of communism and “miscegenation” at public meetings.Footnote6 In early 1928, Reverend Hazael Maimane encapsulated widespread anti-communist prejudices when he complained to the Johannesburg newspaper Umteteli wa Bantu about a speech by the pro-communist ANC president, Josiah Tshangana Gumede. On returning from the Soviet Union, Gumede had enthused about how divorce was easier in Russia, liberating “sensual men and women.” Maimane, however, warned that the “easy dissolution of marriages” was already “becoming common even in this country,” threatening children and the black race as a whole.Footnote7 Missionary and anthropologist, John Henderson Soga, noted in 1932 that most black South Africans already approached adultery with an attitude “of tolerance, but not of approval.”Footnote8 But the divorce proceedings of communist stalwart, John Gomas, add some colour to Maimane’s association between revolutionary ideals and “free love.” In 1929, Gomas alleged that his wife, Rebecca Meyer, a young communist waitress in Cape Town, had slept with two other party members, Sidwell Mohapi, a laborer, and Claudia Silwana (the wife of CPSA-ANC-ICU leader, Stanley Silwana) after a June 1928 CPSA meeting, while he was in prison on sedition charges.Footnote9 Many of Rebecca Meyer’s communist contemporaries also had extra-marital relationships. Bill Andrews, the founding party secretary, had an affair with Johannesburg teacher, Eva Green. Josie Mpama, a domestic servant and early black woman communist, married to CPSA leader Edwin Mofutsanyana, had an affair with Moses Kotane. Teacher and communist labor organizer John Beaver Marks had an “untidy” private life.Footnote10 It is unclear whether these relationships reflected a wider acceptance of infidelity, a radical criticism of the nuclear Christian family, people simply cheating on their partners – or a mixture of all three. While ideas about “free love” were gaining traction among communists in interwar South Asia, America and Europe, the South African party could be startlingly restrictive.Footnote11 CPSA secretary, Lazar Bach was straight-forwardly abusive in his attempt to book a one-bed hotel room with a young woman member, Ray Alexander; Joseph Kumalo and John Gomas were consummate wounded patriarchs, profoundly disconcerted by the affairs of their wives, Rebonie and Rebecca.Footnote12 Eddie Roux, editor of the party paper, was told he could not marry Winifred Lunt because she was too middle class; HA Naidoo and Pauline Podbrey, Durban-based trade unionists, were ordered to relocate to Cape Town, marry and settle down, to avoid controversy.Footnote13

John Gomas, ICU and CPSA official, and his wife Rebecca Maria Meyer, a coloured waitress and CPSA member (Western Cape Archive).

For many black South African men, like Joseph Kumalo, African immigrants from outside South Africa’s borders were a more obvious source of deviancy than ideas from Russia – stealing partners, starting fights and disrupting marriage practices. At times, the CPSA supported immigrant workers. At a July 1926 Johannesburg ICU meeting, CPSA member T.P. Tinker recounted how he had been arrested for organizing Mozambican workers.Footnote14 The CPSA had extensive connections with Lekhotla la Bafo in Basutoland (today’s Lesotho); and the party paper advocated for “a united front of all mine workers for raising the wages and improving the standard of living of all mine workers, whether [from the] Union [of South Africa] or non-Union” in 1934.Footnote15 Anxieties over the employment of immigrants, however, went back to the foundation of the white labor movement in the 1890s, and remained influential within the CPSA for decades after. Bill Andrews, for example, wrote in 1925 that it was

necessary to put an end to the policy of importing low-paid uncivilized labourers and to base any expansion of industry on the employment of civilized labourers. There cannot be the same objection to the entry into the Union of civilized European immigrants willing to take their share in the establishment of industry as there is to uncivilized non-European immigrants. The one class will held to strengthen civilization in Africa, the other to swamp it.Footnote16

The CPSA’s newspaper concurred in 1927 that the government’s “total failure” to restrict “labour importation in white South Africa’s own interest” meant that “any body of native strikers is faced with an almost UNLIMITED RESERVOIR of ignorant and unorganised potential ‘scabs’ who can be drafted at short notice like troops to the scene of action.”Footnote17 Lodge rightly argues that the white laborism of Bill Andrews and others needs contextualization.Footnote18 But Andrews’ approach to black immigrants was consistent and pretty uncomplicated. In 1913, he blamed the “poor white” problem on black immigration. In 1925 he called on the newly-elected Pact government to honor a pledge against the “increased introduction of foreign labour which ultimately works irreparable injury on the white population of this Union.”Footnote19 The early CPSA were not like the South African Labor Party (SALP), which doggedly campaigned for the restriction of Indian and Mozambican immigrants, but anti-immigrant rhetoric remained an important (and under-appreciated) part of its anticapitalist rhetoric. In December 1926, after being expelled from the ICU on the basis of his CPSA membership, Eddie Khaile, an accountant and trainee pastor, called for Clements Kadalie’s repatriation.Footnote20 As ANC general secretary, Khaile went further – tabling a petition for the deportation of all Central Africans after the 1927 Western Native Township riots.Footnote21 When the ICU criticized Khaile, J.T. Gumede ambiguously told a CPSA meeting that the ANC would “not alter its plan to please Kadalie and will pursue its course of uniting the SA natives to help themselves.”Footnote22 In 1928, the party paper saw restrictions on Mozambican immigrants as “desirable,” protecting “local industry from being flooded with cheap indentured labour,” and it continued to argue into the 1930s that immigration kept South African workers in “unemployment and misery.”Footnote23 Joseph Kumalo, clearly, still thought the same way in 1945.

Comintern instructed the CPSA to organize throughout Southern Africa.Footnote24 But limited solidarity with immigrant workers at home was mirrored by apathy toward African workers abroad. Although some ICU leaders exhibited equal hostility toward Mozambicans, the trade union organized branches across colonial borders, and both the ANC and ICU dropped “South Africa” from their titles in the mid-1920s.Footnote25 It is striking, in comparison, how the CPSA remained tightly focused on national revolution within the confines of the new South African state. In 1926, the party paper explicitly changed from the International to the South African Worker; and during the internal factional battles of the 1930s, the CPSA’s particular brand of South African nationalism became startlingly exclusionary, particularly toward Eastern European immigrants (who Lodge demonstrates had a significant influence within the early CPSA). In retrospect, accusations that Jewish “foreigners” had too much influence within the party, and Moses Kotane’s complaints that many CPSA members were ideologically “not South Africans,” are straight-forwardly antisemitic and anti-immigrant.Footnote26 The CPSA opposed the formation of a party in Southern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe) in the early 1940s, as “there was no ‘objective’ basis for one.”Footnote27

There remained important exceptions. A handful of Zimbabwean teachers used CPSA material in their lessons; a short-lived Communist Party of Southern Rhodesia was founded in 1942; and Zimbabwean ICU leader Charles Mzingeli wrote for the CPSA newspaper in the 1940s.Footnote28 Three Malawian clerks, James Whiteford Mwangamwira, Lester Meschack and Matthew Ndove, read the party paper and wrote to the CPSA from Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania) in the early 1930s. In contact with Molly Walton and Joseph Sepeng of the Johannesburg CPSA, Mwangamwira hoped that Kadalie’s uncle, Yesaya Zerenji Mwasi, among others, could form a Communist Party of Nyasaland in 1932.Footnote29 It was in South Africa, in turn, that significant Central African trade unionists and nationalists – including Robert Mugabe, James Chikerema, James Meschack Chamalula, Henry Chipembere and Flax Musopole – first encountered Marxist ideas.Footnote30 These connections were unusual though, unplanned and underdeveloped.

Lodge impressively demonstrates that for much of the CPSA’s early history, the party was influential but incredibly small, reliant on a few key personalities and their ability to get on – all while trapped inside a political pressure cooker. Within such a tiny group, personal experiences of lost jobs and lost lovers mattered. Bill Andrews possibly believed that comrades lost work to immigrant competitors; Eddie Khaile and Joseph Kumalo, certainly, felt jilted by their Central African rivals. In this context, it was easy to resort to popular anti-immigrant ideas. The available CPSA sources (newspaper articles, letters and court cases) may be minor in-and-of themselves. But they offer crucial insights into how the early party thought about different kinds of liberation. It was not until long-time labor organizer Thibedi William Thibedi coordinated the CPSA with the Transvaal African Congress (TAC) and the newly-formed African Mine Workers Union (AMWU) in the early 1940s that the party began to organize across borders, while questions of love remained subordinate to revolutionary discipline into the 1960s, when Kumalo and many others were exiled abroad.Footnote31 In part, this prompts a broader question: what did the early CPSA really mean when it talked about freedom? The party ended up being integral to South Africa’s national liberation project, charting a red road from capitalist exploitation and colonial oppression. But for marginalized groups, it is less clear where this road ultimately headed to.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henry Dee

Henry Dee is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Glasgow. He is currently completing a book on the life and times of Clements Kadalie, and starting a new project on trade unions and the politics of transnational migration in the interwar period.

Notes

1 South African National Archive, Pretoria (SANA) KJB 408 N1/14/3 “Nyasaland African Congress” (1945-1951), Nyasaland Government Representative to Native Commissioner, September 27, 1945.

2 “Trouble at Western Native Township,” Umteteli wa Bantu, December 31, 1927.

3 SANA GNLB 401 55/53 “The Nyasaland, East African and Rhodesian Helping Hand Society” (1933).

4 Lodge, Red Road to Freedom, 249.

5 I’m heavily indebted to Tom Lodge who was a generous and hugely knowledgeable examiner of my PhD research in 2019.

6 Lodge, Red Road, 173, 197–198, 207, 239, 250, 259.

7 H.M. Maimane, “Marriage Contract and Dissolution,” Umteteli wa Bantu, April 21, 1928.

8 Delius and Glaser, “The Myths of Polygamy,” 90.

9 Western Cape Archives CSC 2/1/1/1151 124 “Illiquid Case: Divorce John Stephen Gomas vs Rebecca Maria” (1929). Thanks to Sue Ogterop for copying this file.

10 Hirson, “Lies in the Life of Comrade Bill,” 59; Edgar, Josie Mpama/Palmer, 81; Lodge, Red Road, 173.

11 Loomba, Revolutionary Desires, 21, 112–155; Battan, “What Is The Correct Revolutionary Proletarian Attitude Toward Sex?,” 43–70.

12 Lodge, Red Road, 207.

13 Lodge, Red Road, 212, 260.

14 SANA JUS 915 1/18/26 “Police Reports RE Activities of Native Weekly Newspaper RE Meeting of Natives: Part 3” (1925-1926), report of Johannesburg ICU meeting, July 4, 1926.

15 Edgar, Prophets with Honour, 22–25; “Shangaan Labour on the Gold Mines,” Umsebenzi, July 21, 1934.

16 Andrews, Lucas and Rood, “Report by Commissioners Andrews, Lucas and Rood,” 346.

17 “Another Little Strike,” South African Worker, July 15, 1927.

18 Lodge, Red Road, 23.

19 Bradlow, Immigration into the Union, 371; W.H. Andrews to Minister of Mines, 3 December 1925, SANA MNW 802 2489/25 “Retrenchment of European Labour on Mines: Shortage Native Labour: Part 1” (1925–1927).

20 A.A. Toba, report, 18 December 1926, SANA JUS 916 1/18/26 “Police Reports RE Activities of Native Weekly Newspaper RE Meeting of Natives: Part 5” (1926-1927).

21 H.D. Tyamzashe, “Past and Present,” Workers’ Herald, February 18, 1928; “African Congress & ICU Co-operation,” Workers’ Herald, March 17, 1928.

22 “Russia Today,” South African Worker, March 30, 1928.

23 “Mozambique and the Union,” South African Worker, May 25, 1928; “Portuguese Native Labour on the Rand,” Umsebenzi, January 21, 1933; “Native Slave Labour from Mozambique,” Umsebenzi, December 5, 1936.

24 Lodge, Red Road, 93.

25 The South African Native National Congress became the ANC in 1923; the ICU of South Africa became the ICU of Africa in 1924.

26 Lodge, Red Road, 181, 188, 213.

27 Lessing, Under My Skin, 275, 352.

28 Van der Walt, “The First Globalisation and Transnational Labour Activism in Southern Africa,” 243.

29 Malawi National Archives, Zomba, NC 1/23/4 “Communists in Nyasaland.”

30 Van der Walt, “First Globalisation,” 243; Chipembere, Hero of the Nation, 144; Kalinga, “‘The General from Fort Hill’,” 305.

31 Lodge, Red Road, 255–256; Thibedi appears as TAC general secretary in Umteteli wa Bantu, March 26, 1938 and May 7, 1938.

References

- Andrews, William Henry, Frank Archibald William Lucas, and Willem Hendrik Rood. “Report by Commissioners Andrews, Lucas and Rood.” In Report of the Economic and Wage Commission (1925). Cape Town: Cape Times Limited, 1926.

- Battan, Jesse F. “‘What is the correct revolutionary proletarian attitude toward sex?’ Red Love and the Americanisation of Marx in the Interwar Years.” In Marxism and America: New Appraisals, ed. C. Phelps and R. Vandome, 43–70. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

- Bradlow, Battan Edna. Immigration into the Union: Policies and Attitudes. PhD thesis. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 1978.

- Chipembere, Henry. Hero of the Nation: Chipembere of Malawi: An Autobiography. R. Rotberg, ed. Blantyre: Kachere Series, 2002.

- Delius, Peter, Robert Rotberg, and Clive Glaser. “The Myths of Polygamy: A History of Extra-Marital and Multi-Partnership Sex in South Africa.” South African Historical Journal 50, no. 1 (2004): 90.

- Edgar, Robert R. Josie Mpama/Palmer: Get Up and Get Moving. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2020.

- Edgar, Robert R., ed. Prophets with Honour: A Documentary History of Lekhotla la Bafo. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1988.

- Hirson, Baruch. “Lies in the Life of Comrade Bill.” Searchlight South Africa 3, no. 3 (1993): 59.

- Kalinga, Owen. “The General from Fort Hill’ Katoba Flax Musopole’s Role as an Anti-Colonial Activist and Politician in Malawi.” Journal of Southern African Studies 46, no. 2 (2020): 305.

- Lessing, Doris. Under My Skin. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

- Lodge, Tom. Red Road to Freedom: A History of the South African Communist Party, 1921-2021. Sunnyside: Jacana, 2021.

- Loomba, Ania. Revolutionary Desires: Women, Communism and Feminism in India. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

- Van der Walt, Lucien. “The First Globalisation and Transnational Labour Activism in Southern Africa: White Labourism, the IWW, and the ICU, 1904-1934.” African Studies 66, no. 2-3 (2007): 243.