Abstract

During the last decade, a number of media theorists have defended the idea that photography, through its new computational and networked existence, is progressively losing its representational identity. While it is evident that the computational materiality of networked photographs has turned most distributed images into data generating assets, the way most photographs continue to operate in our society suggests that the specificity of the medium remains practically unaltered since modernist times. In an age where immersive virtual worlds will soon dominate our online interactions, this paper discusses the current forms and uses of photography within the emerging virtual spaces. Through practice-led, experimental research on the use of virtual cameras to record immersive, lived experiences, and the analysis of recent works produced by the so-called virtual photographers documenting their gaming interactions, this study investigates the value of the photographic frame as a still, two-dimensional representation, while questioning its function within extended reality environments.

Preamble

The screen lights up. A bright blue, Meta logo, appears in the middle of the scene, welcoming another user into its parallel new world. My virtual living room looks impressive, clearly neater than the one at home. A great, panoramic window, lets the light of a tropical sunset through. Five air balloons wonder across the horizon, while the cracking sound of dried wood burning in the virtual chimney helps me relax after a long day of work.

I look down and see my hands; my virtual extremities. They seem slightly larger than my real ones but feel strangely mine. They move with fascinating precision, mimicking the gestures I perform while holding the Oculus controllers. These hands are immaculate; no cuts, no prominent veins. Only fingers and flesh, with ten perfectly cut nails (). My body too seems happy here. It wonders around the space with exceptional lightness, floating from one side of the room to the other, lifting objects without effort, letting itself fall with no risk of harm.

The screen turns black and lights again. I am now in one of the most popular spaces within Meta’s Horizon Worlds; a social virtual app where users can hang out, play games and attend all sorts of immersive events. The pop-up menu shows some information about my digital self; Ronalda Smith is wearing a rather fancy jacket today. As soon as the menu disappears I can’t see Ronalda anymore, but I am Ronalda now. I am Ronalda Smith. Her eyes are now my eyes. Her movements determine my experience of the space.

A boy approaches and asks me to play a music game. Who is he talking to? Can’t he see that I’m a grown up? Of course he can’t. He is talking to Ronalda now, there is no way he could tell my age. This is a ludic space. I should make an effort to have fun.

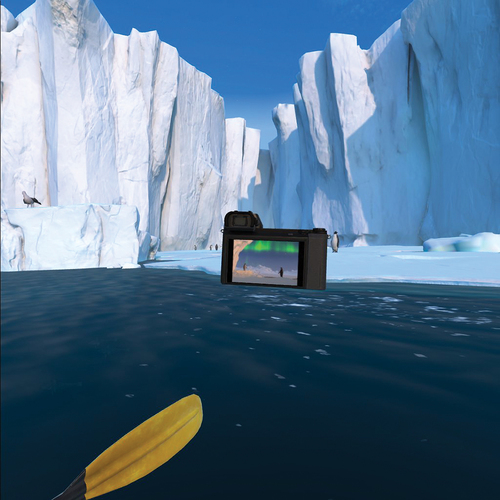

I look through my virtual gear and get the camera out. Now we are talking! I point around, take some snapshots. People here are very loud. I want to document the space, but most of all, I want a photograph of Ronalda in this space (). I could ask someone around to take my picture, but I don’t feel like starting a conversation with all these strangers just yet. I’d better take a selfie. There you go!

Satisfied, I leave the space.

Introduction

While the current experience of virtual reality is still very raw and far from the ideal of a unified Metaverse recently proclaimed by the founder of Meta, Mark Zuckerberg, immersive social apps like Horizon Worlds have become very popular.Footnote1 It is clear that for many people — specially youngsters — virtual worlds are as real as their local park. This is not surprising. Once you put on your VR headset, most barriers with the ‘real world’ disappear. The virtual camera view follows eye movement with such precision that the brain has no reason to believe that what it is perceiving is other than a real-life experience. But is it not a real life experience? While the nature of the virtual space might lack of solid materiality, the self operates within it in a very real manner. Interactions with virtual objects and social relations with other users — some of which often turn into friendships or romantic relationships — make these worlds as habitable for the mind as any physical space.

Virtual experience, however, is by no means new. Before virtual worlds could be experienced in an immersive manner, video games already offered an alternative reality for gamers to develop a parallel existence through their digital alter egos. Games like SIMS and Second Life, had a similar socializing framework to that of Meta’s Horizon Worlds. One can also play today all sorts of PC video games, such as Company of Heroes 3, through real-time social interactions, where avatars belonging to users from all over the world get together to fight against each other or work towards a common strategy.

As it occurs with immersive reality experiences, the gameplay experienced through flat screens offers users a digital space where personal experiences unfold from one’s self, into the screen and the virtual world within it. An just as it happens in the physical world, these virtual users also seem to feel an evident urge to document their experiences through still, two dimensional representations; namely photographs. It is this somewhat compulsive desire to take pictures, not understood as the pleasure of looking or being looked at, but as a personal drive to freeze and frame personal experiences in the virtual realm, that this paper will discuss.

Framing the gamespace

While some recent texts on the contemporary nature of photographs have suggested that the medium may no longer be defined as human, others insist on the idea that photography’s specificity has ceased to exist altogether as a result of its networked performance.Footnote2 Although these theories rightly explain some of the changes undergone by the medium through its new computerised and algorithmic nature, as this paper will discuss, even in the most techno-futuristic scenarios, photography’s specificity is not only thriving, but expanding unstoppably.

The so-called in-game photography genre, also known as screenshotting, has been proliferating for over a decade. Although its origins date back to 2006 with the publication of the book Gameplay: Art in the Age of Video Games, it was in 2014 through the video game The Last of Us Remastered that photo-modes started to be used frequently in any major videogame release (Švelch 564). In-game photography, however, has a variety of applications, not all of which are relevant for the purposes of this discussion. Promotional screenshots, for example, like those produced by in-game photographer Petri Levälahti (), are taken by professionals and serve mainly for the purposes of marketing (Švelch 565). There are also titles in which photography as practice is the main objective of the game. Pokémon Snap (1999) and Wild Earth Photo Safari (2008), challenged players to produce technically successful photographs of different subjects within the gamescene. These were shot with the use of virtual cameras, where basic adjustments (ISO, focal distance and general composition) allowed players to have some control of their photographs (Möring and Mutiis 72). However, given the pre-set conditions of these photographic situations, creative freedom in this type of games is generally very limited, with the motivation of the player-photographer directed mainly at winning the game.

A much more interesting approach is achieved when taking pictures is not part of the video game's objectives, but an added future that allows users to capture a moment of their gameplay, driven only by their own will to produce a photograph of the scene. These images are sometimes done using virtual cameras with in-built photo-modes, while other times they are obtained through direct screenshots. The most common motivation for gamers when producing such images is to document their achievements, to demonstrate that ‘they-were-there and saw-this’. These photographs are often shared in social platforms amongst users, serving as a costless promotional strategy for videogame developers (Möring and Mutiis 78–79). As Cindy Poremba argues in her essay ‘Point and Shoot: Remediating Photography in Gamespace’, what players are doing with their images is to ‘validate these experiences’, to commit to them, demonstrating their presence in the game and reinforcing their identity as players within the video game community (50). Their ability to control the content of the picture is essential here. Players are not simply taking a screenshot of a fixed computer screen or a filmscene, they are moving around the camera-angle, selecting the right point of view, and choosing, to some extent, a relevant decisive moment; a moment that might also be provoked by the player themselves through their game-play behaviour. The resulting image might not be ‘written with light’, but it serves non-the-less as a realistic representation of an immaterial reality (Giddings 46). And while these photographs might be only referencing a virtual representation of the real, the player’s psychological experience is certainly real, often filled with feelings and social interactions that are no different from those taking place in their corporeal world (Poremba 51).

A different type of in-game photography takes place when the player enters the video game with the only aim of taking pictures within the gamespace. These users have no intention of winning or completing any of its objectives. Instead, they wonder around the gaming worlds, turning the gamescene into a space of photographic voyeurism, but also in a place for artistic critique on the virtual representation of contemporary issues.

A good example of this practice can be found in the work of Allan Butler. In his ongoing project, Down and Out in Los Santos, which he started shooting in 2015, Butler uses the photo-mode available in the video game Grand Theft Auto V to take pictures with a virtual smartphone of the game environment. The artist focuses on the poor and homeless characters spread throughout the game, which have no other function but to complement the aesthetics of the scene and make it look like a realistic city from the twentieth-first century.

In the videogame community, these type of passive characters are known as NPCs (non-player characters). Generally, they are not designed to compete with the player, though in certain titles they might intervene to make the gameplay more or less challenging. In Grand Theft Auto V particularly, the NPCs are coded to interact with others, including Butler himself. At times these characters react to his proximity, allowing the artist to capture a somewhat emotional response in their gaze. Other times his photographic subjects attack him; forcing Butler to swap his smartphone camera for one of the available weapons in his virtual gear in order to defend himself. In most occasions, however, the NPCs behave like zombies; unable to register the player’s movements, they ignore his attempts to take their picture, giving the resulting photograph a somewhat journalistic aesthetic (). Controversially, Butler would then share these images through the photo-sharing app Instagram, attributing them a journalistic hashtag, which allows the work to penetrate photojournalistic networks. As a result, he tends to get numerous automated ‘likes’ from bots that are coded to interact with such images, and which only purpose is to increase the number of followers of their host-accounts. According to Butler, this sharing strategy gave his project a ‘poetic turn’, as the coded reaction of his NPC subjects received a secondary coded reaction from another software, with these ‘sycophant-bots’ — as the artist defines them — somehow becoming the primary audience for his virtual photographs (Butler n.p.).

Fig. 4. Alan Butler, ‘8i44GOVZZkyL_9NUulteHQ_0_0.Jpg’, from Down and Out in Los Santos, 2016 © Allan Butler.

The artist Shiwei Yu also photographed the characters’ reaction in the game Watch Dog: Legion, for her project Under the Gaze (2021). In this game, taking pictures is an essential part of the gameplay mission, used mostly to collect evidence from the enemy’s base. But the developers of the game also acknowledged the gamers’ growing desire to record their experiences as they engaged in their play, even when the pictures would not contribute to the game’s objective. A secondary, more advanced, image-capture function called ‘photo-mode’, was thus built into the gamer’s virtual gear, allowing the player to pause the scene and move around the viewfinder to frame their chosen subject. When selecting this tool, a wide range of camera functions become available for the player to fine-tune their creations (focusing, tilting, panning). When Shiwei Yu selected this photo-mode option in the middle of a populated gamescene, the artist discovered that whenever she confronted an NPC closely with the camera, almost all of them reacted aggressively, often trying to attack her, or giving her a daring look as if demanding to put her camera down (). As the characters’ behaviour suggests, the dynamics of the game appear to have been designed to assimilate the camera with some sort of weapon, while the automated reactions of these NPCs seem to replicate a widespread response from everyday subjects when noticing that their picture is being taken without their consent in the physical world. Beyond their individual motivation for the production of the work, both Butler and Yu’s projects seem to point at the perpetuation of class division and urban violence through popular video games, as well as the growing tensions between street photographers and their anonymous, non-consensual subjects.

While some might argue that in-game photography constitutes only a remediation; a visual representation of a fantasy world with thin links to photographic practice, as Poremba explains, there is no doubt that for their creators, these images remain photographs in their indexical form. They certainly record the lived experiences of the players, turning them into memorable moments, which accommodate expression and creative control, and are therefore able to speak about the essential quality and functions of still photographs (Poremba 53).

In any case, whether individual experiences are real or fabricated is something that has become very difficult to establish. It has long been accepted that the physical presence of the individual in a scene is not required to participate in the events occurring in a given place. We all became accustomed to participating remotely in all sorts of activities during the Covid pandemic. That a photograph produced in virtual worlds is not of something real, is only an issue if you consider that photographs can only depict our corporeal experience (Poremba 53). It would appear indeed very reductive to hold a fixated idea of the technological nature of photography and the social frameworks in which photographs are ought to operate. As Seth Giddings argues in his essay ‘Drawing without Light’, if we accept that since its invention, the medium has been part of a continuous flux of technological developments, able to accommodate to the constant changes of our social dynamics, virtual photographs would no longer be seen as a rupture, as a dramatic, apocalyptic moment for the medium, but as an evolution, just another phase in our relation to the camera and our desire to capture fleeting moments of reality, whatever ‘the real’ might mean for each of us (50).

Photography and virtual reality

Real-life, virtual experiences, become much easier to reclaim in the context of extended reality. As opposed to PC gaming, immersive virtual environments break with the perceptual barriers of the flat screen, allowing users to gain an inseparable agency of their digital self. While social PC games like SIMS were already conferring players with certain agency, the visual and corporeal experience developed while playing these games was mediated by a camera view that established a clear separation between the user and its avatar. This camera not only offered a view point from a rather unnatural perspective (above the avatar’s body) but it was also transmitted through a computer screen that accentuated the physical distance between the corporal self and the avatar’s identity.

Immersive virtual experiences, instead, allow us to see the world directly through the avatar’s eyes and hold objects using the avatar’s hands, which in response produce small vibrations on our corporeal extremities through the device controllers. The user’s relation to the virtual environment could not get any more real. The avatar’s movements are directly guided by the user’s intentions, which they perform in real time, following their personal interests and desires.

What appears most interesting about this experience, however, is the function of the photographic frame within this infinite, immersive space. Although immersive virtual reality remains at its infancy, a large number of virtual apps have introduced photography as part of the user’s experience in their virtual products. The National Geographic app, for example, allows the traveller to use a virtual DSLR to record memorable moments of their trips, collecting them in a virtual album that can later be shared in social media. Just as it occurs when using a physical DSLR, this app enables the user to either look at the scene through the LCD screen, or by using the camera’s view finder (). Similar travel apps, like Brink, allow the user to take pictures of the landscape by making a framing gesture with their virtual hands (). Once the gesture is performed, a rectangular image frames the selected scene, which is later collected in a photo-album. Meanwhile, virtual social apps like Rec Rooms or VR Chat, have also included cameras as part of their basic gear, with platforms like Horizon Worlds acknowledging the urge for the selfie and incorporating this much wanted function into their image capture devices (). Interestingly, even when no in-built camera mode is available in a virtual app, the VR headset would always allow for direct image capture in the form of a screenshot. When opting for this form of photographic production, all the user needs to do is look at the subject and press the trigger button in their VR hand controller. The avant-garde fantasy of the eye becoming a camera has never been closer to being true.

It remains to be asked the reasons behind the users’ desire to freeze their immersive experience through a bidimensional format, while they are being offered with a much richer, 360°, observational experience within these immersive worlds. One way to answer this question might be to think about visual perception and the processes the brain uses to make sense of the world. As Joanna Zylinska explains in her essay ‘Perception at the End of the World’, it has generally been accepted that visual perception translates the visual into an understandable collective unit to offer a picture of reality, with neuroscientists now agreeing that this process is part of the survival mission of the eye-brain connection. While the eyes may capture an infinite number of elements within the visual field, the brain is constantly downsizing this information, cutting it in essential pieces in order to make sense of the world, by selecting only that which may help us meet our biological and social needs (13–24). According to Zylinska, this ‘cutting of visual information’ undergone by the brain, needs to be seen as ‘one of the most fundamental and originary processes in which we emerge as “selves”, as we engage with matter and attempt to give it (and ourselves) form’ (Kemper and Zylinska 27).

We could then argue that the desire of framing, whether this is done through our biological, visual perception, or through the aid of technological devices, is so basic because it helps us understand our presence in the world. The photograph is, above all, a reaffirmation of a self-defining process that the brain has already performed. We take photographs not only because we enjoy looking at things, but mostly because we enjoy certainty. The certainty of our own existence; of a ‘this-has-been’ in ontological terms, that is stated for, and because, of the individual taking the picture. This still, bidimensional representation, offers comfort against the insecurity of the photographer’s presence in a given reality, which as a result, pushes them to produce a larger number of images the more complex such reality becomes. We may think for example about the selfie phenomenon, mostly produced by teenagers in the midst of a traumatic transition into adulthood, or the new parent compulsively taking pictures of their new born; as cute as their baby might appear to them, the urge of taking her picture 24/7 might be better explained by their own need to understand the radical changes to their individual identity, which from now onwards will be unavoidably defined by parenthood. Even simple modifications in our life, like cutting one’s hair, changing jobs or moving to new city, often prompt a multiplicity of snapshots from their protagonists, most of which are never shared or printed, but taken for the sake of conferring a personal reaffirmation of our ever-changing condition in the world.

Conclusion

The above discussion might explain why the production of photographs in virtual worlds is growing at such remarkable speed. Immersive experiences invite us to join artificial realities where we can free our looks and movements from most corporeal restrictions, re-invent our identity and develop behaviours in fantastical digital places that distance considerably from anything known in the physical world. The challenging acceptance of the self in such places, the identification of an avatar’s body with our own, of a digital workspace with our physical office, requires a psychological transformation in which the brain-eye connection plays a significant role. The inclusion of image capture functions, therefore, whether through the use of virtual cameras or screenshots, might proof key to aid that understanding, enabling us to embody these new experiences, while minimising the psychological risks linked to a possible disassociation from our corporeal selves ().

The pleasure of being looked at, therefore, may be explained by the desire of seeing oneself — or an object relating to the self — as something emanating from the photograph, which should not be understood as a narcissistic behaviour, but rather as an additional step (aided by technology) in the survival mission performed by the brain-eye connection.

As extended reality experiences continue to develop, there is no doubt that virtual photographs will continue to multiply unstoppably, demonstrating that photography’s condition, with its still, bidimensional specificity, has never been more valuable and prevalent than today.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paula Gortázar

Paula Gortázar is a photography researcher, artist and lecturer based in London. She was awarded her PhD from the University of Westminster in 2018. Paula’s research has been published in various academic journals, including Photography and Culture, Third Text, and Fotocinema. She currently lectures in photography at the University of Westminster in London.

Notes

1. The potential of the Metaverse was discussed on a livestreamed promotional video by Meta’s founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, (As of 28 December, 2021. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKPNJ8sOU_M).

2. See Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography; and Dewdney, Forget Photography.

Bibliography

- Butler, Allan. Down and Out in Los Santos. 2015. http://www.alanbutler.info/down-and-out-in-los-santos-2016

- Dewdney, Andrew. Forget Photography. London: Goldsmiths Press, 2021.

- Giddings, Seth. “Simulated Photography in Video Games.” In The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, edited by Martin Lister, 41–55. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Kemper, Sarah, and Joanna Zylinska, as quoted in Zylinska, Joanna. Perception at the End of the Word (Or How Not to Play Videogames), 27. New York: Flugschriften, 2020 (2012).

- Möring, Sebastian, and Marco de Mutiis. “Camera Ludica.” In Intermedia Games—Games Inter Media, edited by Miuchael Fuch and Jeff Thoss, 69–93. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.

- Poremba, Cindy. “Point and Shoot: Remediating Photography in Gamespace.” Games and Culture 2, no. 1 (2007): 40–58. doi:10.1177/1555412006295397.

- Švelch, Jan. “Redefining Screenshots: Toward a Critical Literacy of Screen Capture Practices.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27, no. 2 (2021): 554–569. doi:10.1177/1354856520950184.

- Zylinska, Joanna. Nonhuman Photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.

- Zylinska, Joanna. Perception at the End of the Word (Or How Not to Play Videogames). New York: Flugschriften, 2020.