Abstract

This article explores photographic representations of the border between the Republic of Ireland and the state of Northern Ireland. This contentious division of the island occurred in 1921 following a War of Independence. It left six of the island’s thirty-two counties under British rule and its creation precipitated a Civil War (1922-1923). Photography has been employed to either undermine or solidify the border’s existence. At various times its visibility was heightened or negated reflecting the political climate. The article will consider the border imagery reproduced in popular magazines such as LIFE and also those created by stock photo-agencies. Mainly consumed by non-Irish audiences, these representations were initially quaint, however, as political and civil unrest grew, and British troops occupied and patrolled the border area, the depictions became more sinister. Border checkpoints and a ‘wild’ countryside teeming with paramilitaries became visual shorthand for this ‘problematic’ space. Recent Fine Art representations of the border in the post-Brexit era will also be considered.

This paper will explore photographic representations of the border which divides the island of Ireland into two jurisdictions namely the Republic of Ireland and the state of Northern Ireland. At various times, this border’s visibility was either heightened or negated to reflect the political climate. Photography was, and is, employed to undermine or solidify the border’s existence. In line with Nail’s theory of the border, tropes such as the checkpoint, watchtower and patrol, will be examined.Footnote1 As Graham notes ‘the intensity of the politics of the border have produced their own kind of photographic responses.’Footnote2 This analysis will concentrate mainly upon press or stock imagery. International journalists, on assignment, often took photographs with non-Irish audiences in mind, and whilst the emphasis will be upon press output, some documentary and Fine Art responses will also be referenced as a counterpoint.

Before discussing the photographs, it is necessary to give a brief overview of the events leading up to partition. This contentious division of the island occurred in 1921 following on from the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. These legislative measures occurred in the aftermath of the Rising of 1916 and a War of Independence between 1919 and 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 provided for the establishment of the two-state solution which left six of the island’s thirty-two counties under British rule. Its creation precipitated a Civil War (1922–1923) and a near century of conflict.

The six counties that make up the state of Northern Ireland were part of the larger nine county province of Ulster, however, three of these counties were not included in the new state. This ensured that the new Northern Irish state had a built in Protestant and pro-union majority leaving the Catholic and Republican population as minority residents in a sectarian state. Catholics were faced with discrimination with regards to housing, education and employment opportunities. The creation of the border also isolated the three border counties Protestants (residents of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan) and separated them from their co-religionists.

Between 1956 and 1962, the Irish Republican Army mounted a border campaign which targeted infrastructure and aimed to destablise partition. It was not well organised and was considered a tactical failure. Official reactions to the civil rights movement, from the late 1960s onwards, heightened tensions. The British Government ordered the deployment of troops to Northern Ireland in August 1969. This was to counter the growing disorder surrounding civil rights protests and an increase in sectarian violence during the traditional Protestant marching season. On Sunday, 30 January 1972, British paratroopers opened fire on a march of civil rights supporters killing thirteen people. The ensuing years of violence included internment without trial, bombings, the Hunger Strikes of 1981 and the deaths of ca.3,500 people that attracted international media attention. The lives lost across all sectors of society (civilians; members of loyalist and republican paramilitaries; British Army personnel and those serving in the Royal Ulster Constabulary police force) were recorded by David McKittrick in his seminal book Lost Lives.

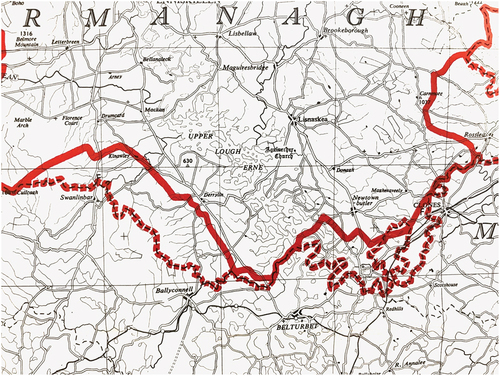

shows a map revealing the complexity of the border region and the many small roads which intersect and weave around natural features such as lakes, rivers and mountains. Accounts from the early period of the border, show that even people living in the area were often unaware of where the border was with talk of towns, villages and even houses being split in two. The following quotation from Seán Ó Faoláin’s short story No Country for Old Men exemplifies this: ‘I wish I knew to hell where exactly our wandering border is tonight … We’re in the South now. But this bloody border loops all over the place. Any road we take, if we take it far enough, might take us into trouble again.’Footnote3

Fig. 1. Irish Boundary Commission, Boundary changes recommended in Southern Fermanagh close-up, 1925.

The border was created along the lines of the old county boundaries which, in the divided northern province of Ulster, had been in place since the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Before partition these county borders had little impact on everyday life. The creation of the border cut communities off from their economic and social hinterlands. Regardless of religion or political persuasion people in border communities gravitated towards the nearest largest town and the new border interrupted this. As Nash, Lorraine and Bryan, note the border ‘cut through complex local micro geographies of ethnic, political and religious difference, regional agricultural and economic networks, and senses of collective regional identity.’Footnote4 The extent to which the border, in its earliest decades, was linked to customs and the generation of revenue is explored by Moore.Footnote5 Indeed, recent research by Cormac Moore suggests that the Free State was instrumental in implementing border controls in a more forceful manner.

The exact delineation of the border was intended for review. In 1925, a Boundary Commission examined the border with the promise of ‘determining the wishes of residents so far as they were “compatible with economic and geographic conditions.”’ (Article XII, Anglo-Irish Treaty, December 1921). Some viewed the latter clause as an opt out and in the end the report was leaked and the border remained unchanged.Footnote6 This map shows the border and the proposed but never implemented changes. As Vaughan-Williams writes ‘none of these borders is in any sense given but (re)produced through modes of affirmation and contestation … In other words borders are not natural, neutral nor static but historically contingent, politically charged, dynamic phenomena.’Footnote7

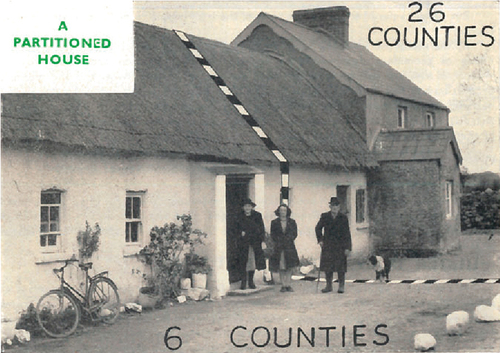

Initially border imagery was quaint and whimsical. In its earliest decades the border was often depicted in a folksy manner with an emphasis upon the rural nature of the Irish Free State (). Donkey and carts and animals being moved across the border were especially favoured. The perceived ‘novelty’ of Irish language signage on the Free State side of the border was another particularly prevalent trope. At this stage, the border manifested as a customs checkpoint and imagery frequently highlighted its ludicrous division of pre-existing structures. shows the Murray homestead at Gortineddan on the Fermanagh-Cavan border. It was one of 1,400 holdings that the border cut through and here we see photography employed within a propagandistic pamphlet outlining the unnaturalness of partition. 600,000 copies of the pamphlet entitled Ireland’s Right to Unity: the case stated by the All-Party Anti-Partition Conference were produced between 1949 and 1953. They were distributed amongst the Irish diaspora in the United States. Although the image provoked laughter at the pointedly bizarre situation in which the family found themselves, the photograph belies what was according to Leary the plight of the Murray family.Footnote8 In later years they were to witness violence with both the Provisional IRA and British army setting up temporary checkpoints at nearby crossroads. It was from there that the British Army made a number of controversial incursions into the South. This photograph has been widely used in histories of the border providing an impactful visualisation of its arbitrary nature.

Fig. 2. Border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland on the road to Belfast from Dublin, c.1950 (Getty Images).

Fig. 3. The Murray House at Gortineddan on the Fermanagh-Cavan border Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Ziff’s discussion of photography and the Troubles refers to a similar image taken by Mike Abrahams in the 1980s which shows a farm owned by Peter Caraher in South Armagh which straddles the border.Footnote9 The older members of the family have been placed in South Armagh and the children in County Monaghan, the Republic of Ireland:

The ‘empty’ space between them is the border. This invisible line running through their field (through the photograph) is part of the most heavily watched and defended ground in Europe, costing the British government many millions of pounds each year in both manpower and technology. Yet none of this is seen in the photograph.Footnote10

She refers to this liminal space as a ‘structured absence’. The lines which were overlaid onto the photograph of the Murray farm also echo the interventions undertaken by Sugrue in 2019 in a series of viral tweets which attempt to visually explain the complexity of the border (). These interventions were undertaken in a post-Brexit referendum context where technological solutions were mooted for border control. It reveals the convoluted and absurd nature of the 310 mile border which in some areas sunder churches from graveyards and often runs through homes, farms and businesses.

Fig. 4. Tweet showing the border between Northern Ireland the Republic of Ireland, August 2019. Permission from Mark Sugrue.

As political and civil unrest grew, and especially from the late 1960s, when British troops occupied and patrolled the border area, the depictions became more sinister. Border checkpoints and a ‘wild’ countryside teeming with paramilitaries became visual shorthand for this ‘problematic’ space. Much of the journalistic depictions of the recent Troubles centred upon the urban. City centres were the locus of the bombings and rioting which became the media’s main way of depicting the period and ‘the British presence was more immediately apparent in the towns than the countryside.’Footnote11 In Gilles Peress’ Annals of the North published by Steidl in 2021, we see that his images concentrate upon the urban locations of Belfast and Derry rather than rural peripheries.Footnote12

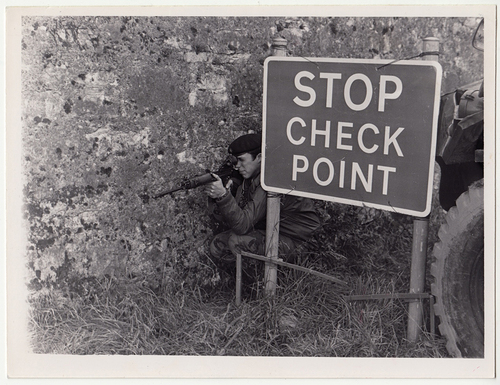

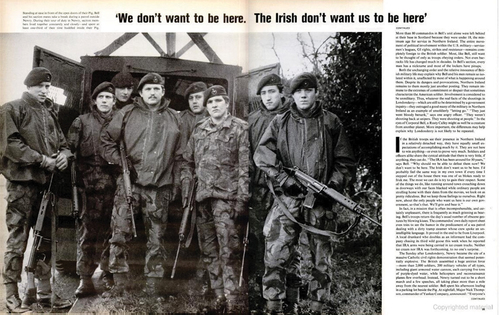

is from a story that appeared in LIFE magazine on the18 February 1972. Entitled ‘Corporal Bell, IRA Target’.Footnote13 The photographer was Terence Spencer and the journalist was Bill McWhirter. South-African born Spencer was a long-time photographer with LIFE, working with them from 1952. His war photography included the typical destinations for a war correspondent of the time with assignments in Vietnam, Cuba and the Middle East. This 1972 photo-story focused upon the experience of Bell as he patrolled the Irish border and unveils the experience of moving through a terrain in which one is potentially a target. The patrol — which was identified by Nail as an important border regime — featured prominently in depictions of the Irish border. The editorial notes that this ‘situation was particularly unusual for Spencer, who in four years of covering the trouble in Northern Ireland, has spent most of his time with the IRA.’Footnote14 The patrol sets out from the town of Newry before moving into the countryside. It includes eight black and white images. Whilst the opening spread does show civilians being searched on the street and in a bar, the majority of the images show Bell’s troop. This typifies the way in which the border was portrayed with the emphasis upon either the Irish Republican Army and the British Army to the exclusion of the local populace and the paramilitary groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force. The images are interspersed between advertisements for Toyota cars, Listerine Mouth wash and Virginia Slims cigarettes. Other stories in the issue cover the winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan and poverty in Seattle. This was the final year of LIFE’s publication and a further examination of popular magazine’s commissioning of photography of the Troubles is beyond the scope of this article but often overlaps with the stock photos that were available then and now.

Fig. 5. Photographer: Terence Spencer; Journalist: Bill McWhirter ‘Corporal Bell, IRA target,’ LIFE magazine, 18th February 1972, volume 72, No.6, pp. 30–33.

Nail noted that the checkpoint often works in conjunction with the patrol and visually the portrayal of British troops patrolling were paired with those showing checkpoints and watchtowers. It is worth noting, however, that by 1975 the Army abandoned road transport in South Armagh and came to favour the helicopter.

The British Army were naturally circumspect about being photographed as this could lead to identification and possible assassination. In addition to military concerns, and indeed two photographers discussed in this article (Michael Brennan and Evelyn Hofer) were cautioned as to what they could show of border infrastructure and military personnel. This caution also extended to the civilian population and as Feldman remarks visibility, identification and the role of photography within these extreme circumstances becomes entwined: ‘not only do such fears, insecurities, and rumours about photographic depiction inhibit documentary picture taking, they reveal to what extent visual perception, after more than two decades of clandestine and not so clandestine war is informed by, if not actually modelled on acts of violence. Seeing and killing, being seen and being killed, are entangled and exchangeable in the ecology of fear and anxiety.’Footnote15

When the British Army were deployed to Northern Ireland in 1969, they resolved to seal the frontier between the two states. The official border checkpoints brought the general populace directly into contact with the division of the country. Travel between the two jurisdictions was not prohibited for residents rather these checkpoints were a physical manifestation of power. With the arrival of the British Army, this meant face-to-face encounters with heavily armed soldiers. The border was marked not with the previous signs, instead we see barbed wire, heavy barricade concrete bunkers and viewpoints.

On the 9th of February 1975, The Sunday Times magazine published an article and photographs depicting the people of Crossmaglen, County Armagh. The text was written by the Derry activist and journalist, Eamonn McCann and the photographs were by Evelyn Hofer. The photographs and article provide a nuanced and rounded portrait of this border community. Spread over seventeen pages, the images include streetscapes and portraits. The latter show a variety of ages and occupations such as a teenager, a Catholic priest, parents of a deceased IRA volunteer, publicans and shopkeepers and the captions include quotations from those depicted. The majority are in colour and the accompanying article aims to get at the mindset of a people, highlighting ‘Crossmaglen’s cherished heritage of resistance to all alien authority.’Footnote16

A photograph of a family group stands out: the Devlin family are portrayed in the vibrant colours of 1970s clothing countering the usual black and white imagery of combatants that typically represent the area. We hear from the mother in the accompanying caption in which she ponders her children’s fate. The fact that the Derry writer McCann had empathy with and an understanding of the local mindset, coupled with the high calibre of Hofer’s photographs marks this article as one that attempts to understand the situation.

The border was partially closed in 1970, when the Army cratered or blocked fifty-one ‘unapproved’ roads. Main roads had checkpoints whilst others were dramatically sealed off. As the decade proceeded, this campaign heightened and of the 300 plus roads that spanned the border, only fifteen were approved. The rest were cratered, spiked, or blocked. These intrusions into the landscape were blunt instruments that separated communities and traditional routes. They reveal that bordering is indeed a process requiring continual interventions and activity. As Freytag notes in their study of the cratering policy of the British Army, the local population felt that ‘they were being blamed for paramilitary acts that were committed far away from the border.’Footnote17 They note that this tactic was largely futile and a wasted effort.

This photograph in was taken in shows the professional boxer, Barry McGuigan, atop a concrete structure on an unapproved road near his hometown of Clones, County Monaghan. This typified the British Army interventions in border locations: making the invisible border visible. To travel upon an unapproved road was risky and considered to be something that only those with local knowledge would do. The photograph was taken by Michael Brennan, a sports and current affairs photographer who had a London-Irish background. He worked for English newspapers including The Sun and The Daily Mail, covering the Troubles in Northern Ireland for the latter. The rights to this image are now owned by the globally dominant image collection Getty and their website states that it is part of the Hulton archive. However, no mention is given of its original context and the same caption is used for several photographs. In email correspondence, the photographer revealed that the photo story was published in the New York Post. Brennan emphasised the rural nature of the location where McGuigan trained, indeed other images in the series, show him jogging along the narrow country road. Via email with the author on the 3 May 2023, Brennan noted that the photo story focused upon ‘the soothing, albeit temporary influence of his [McGuigan’s] achievements.’

Fig. 6. ‘Irish featherweight boxer Barry McGuigan in his hometown of clones, Ireland, 1984. He is posing astride the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland’ (photo by Michael Brennan/Getty images).

Nail notes that, ‘the techniques of border circulation only have the strength that society gives them.’Footnote18 This cratering and blocking of unapproved roads was not necessarily accepted by local communities. No sooner had some been put up by the British Army than they were dismantled by local people determined to regain access to their fields, neighbours and local shops. This resistance has been photographed by Tony O’Shea whose images show the extent of local community involvement in the dismantling of the road blocks.Footnote19 Frankie Quinn’s finely observed depictions of border communities, created between 1994 and 1996, also echo the themes in Walking Along the Border, the collaboration between the writer Colm Tóibín and the photographer, Tony O’Shea.Footnote20 Both show resilience in the face of intrusive surveillance and harsh architectural interventions. Likewise, Leary’s work Unapproved Routes: the histories of the Irish Border 1922–1972, includes photographs of community resistance to this blocking and cratering. Taken by John A. McCabe and reproduced with the permission of Pat Brady, they represent the community’s record of the event. These images include a depiction of a digger being used to repair the road at Munnilly Bridge on the border between Fermanagh and Monaghan. Taken in 1971, it shows the extent of community support and the futility of the operations. Did other communities feel differently about these interventions? Did they think that the barriers provided protection: keeping out those who would commit crimes and retreat to the Republic? If so, their stance is not visualised or recorded to the same extent.

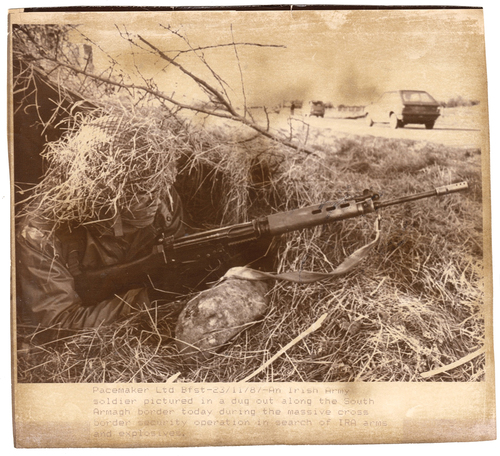

and show photographic prints which were distributed by press agencies in the 1980s. They show patrols and checkpoints on either side of the border. Soldiers of the army of the Irish Republic faced soldiers from the British army generating similar imagery. The first was produced by Pacemaker, an agency created in Northern Ireland and still in existence today, which sought to generate indigenous imagery of the conflict. They were taken in the last era of hard copy prints as photo libraries transitioned from physical archives to servers in the mid-1990s. Some of the images originally existed in this format but were digested and syndicated by the large players in this field as they bought up smaller agencies and the archives of photographers. The versos of these 1980s prints also became densely marked and layered with stamps, codes, measurements and comments which trace the photographic object’s passage from the news agency through to publication and the newspaper archive. Each news agency recorded a photo credit or caption which was pasted onto the back of the image. The author purchased both prints from an online auction site noting that ‘as the number of newspapers being published declined towards the end of the twentieth century their photographic archives were dissolved and this is how so many of these prints come to be on the market.’Footnote21 As photographic objects they are revealing of the press and media practices whereby large photographic agencies stored and circulated prints.

Fig. 7. ‘Pacemaker ltd. 23/11/1987, an Irish army soldier pictured in a dug out along the South Armagh border today during the massive cross border security operation in search of IRA arms and explosives’. Image credit: Pacemaker Press International.

The British army used a system of high-tech watchtowers to survey the territories of Northern Ireland, and to observe the actions of the local people under their occupation. These towers, constructed in the mid 1980s, primarily in the mountainous border region of South Armagh, were landmarks in a thirty year conflict. Jonathan Olley’s 2007 publication and exhibition Castles of Ulster (Belfast: Factotum) also depicted these fortresses (also known as sangars) built by the British Army during the Troubles. The Towers were demolished between 2000 and 2007 as part of the British government ‘Demilitarization’ program for Northern Ireland. The last watchtower was dismantled by February 2007. In her introduction to Donovan Wylie’s book recording the towers before they were removed, Louise Purbrick, notes the following:

The battlefield logic that leads to the construction of watchtowers assumes that the landscapes beneath them are spaces containing only combatants or potential combatants rather than, as they always are, lived environments where people try to complete the routines of living. It is not simply that the siting of watchtowers on hilltops upsets the ordinary scenes of life below, or spoils the view, which in the case of South Armagh is understood to be one of rural beauty, but that fortification alters the condition of being in such a landscape. Without land changing hands, ownership of the space is lessened or lost to those who command the view.Footnote22

The dismantling of this infrastructure provided the peace process which following the Good Friday Agreement, with dramatic photographic opportunities. For two decades following the 1998 Good Friday Agreement you could cross the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland seamlessly. The 1998 Good Friday agreement and the dismantling of the physical border, meant that whilst the island remained divided, the border receded from consciousness. The Brexit vote of June 2016 (which took the United Kingdom out of the European Union) changed everything. The policing of this space, both in terms of customs and immigration, will most likely result in the reinstatement of a hard border between the North and the Republic due to Brexit. The border is now the UK’s only land border with another European country. A new kind of border may lack the physical infrastructure of its predecessor. How will photography depict proposed technological ‘solutions’? The Brexit vote introduced phrases such as ‘hard border’ and ‘Irish sea border’ into the dialogue. Some arguing that there never was a hard border and as the writer Darren Anderson has noted:

There was relief to see our checkpoint vanish. The air felt lighter walking through the place where it once stood. For those of us with long enough memories, it/still does. Yet we made a mistake in removing all trace of the checkpoint, understandable as it was. It is the classic paradoxical error of the iconoclast who topples the symbols of tyranny, only to erase evidence of them. Later professional amnesiacs will come to say there never was tyranny, or resistance to it. And, sure enough, in the midst of Brexit brinkmanship, it was claimed there never had been a hard border.Footnote23

Media images of Northern Ireland during the Troubles could be sensationalist, simplistic and biased. Burke, in the book which accompanies his documentary film, Shooting the Darkness, records that local press photographers, ‘all agreed that the behaviour of the foreign press at such events was deeply insensitive, symptomatic of the fact that those journalists did not have to live in the same small place week after week, year after year.’Footnote24 Artistic responses to the border were often a reaction to the tropes and stereotypes of the international press. As Barber notes photojournalism ‘provided the dominant visual representations of the conflict which both art photo- graphers and artists aimed to subvert, often through their production of imagery that related more closely to aspects of lived experience of the Troubles.’Footnote25

Though Graham has also argued that the fine art and documentary photographic responses were also influenced by wider international trends in photography such as New Topographics or the use of colour. Photographers and artists such as Paul Seawright, Willie Doherty, Anthony Haughey and David Farrell have explored sectarian murders, those ‘disappeared’ by the IRA and states of surveillance. As Carville notes with regard to the work of Haughey, ‘the border region is much more porous and multifaceted than either nationalist or unionist discourses wish to acknowledge.’Footnote26

The press’s binary depiction of the conflict as it pertained to border ccommunities tended to picture only the British Army and the IRA. Missing from the picture were depictions of loyalist paramilitaries. Trevor Dickson’s series showing armed UVF men at an undisclosed location was published in The News Letter without any byline.Footnote27 In the media’s eye the typical gunman was Catholic, Republican and male. This belies the existence of the loyalist paramilitaries who were also active along the border, often with the collusion of British forces and agencies.Footnote28

, from a series Lacuna by the artist Kate Nolan, shows the town of Pettigo which is split in two by the border and the river Termon.Footnote29 One side of the bridge is in the Republic, the other in Northern Ireland. When she commenced her long term project examining the liminal spaces created by borders, the border was invisible and had receded into folk memory for the young people with whom she worked. The Brexit voted changed all that. Work such as Nolan’s functions in a different realm to the stock imagery created on assignment, thus allowing for a more nuanced and in-depth view that takes into account, through oral histories and community work, the opinions of those resident in an area. This project has led Nolan to consider ‘what a border is: a lacuna, a gap, this in-between place, about the differences between the communities and then this physical split being put in.’Footnote30

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Orla Fitzpatrick

Orla Fitzpatrick is a post-doctoral research fellow at Trinity College Dublin, engaged on a project exploring Ireland’s Border Cultures. This project is a Shared Island initiative with Queen’s University Belfast. Her doctoral research related to the Irish photobook, modernity and modernism (Ulster University 2016). She was the Royal Dublin Society Post Doctoral Research scholar in 2021. She has published widely on Irish photographic, design and material culture. Recent articles include an analysis of an Irish Republican Army surveillance album, dating from the Irish War of Independence, which appeared in the Journal of the History of Photography in 2022. She recently curated an exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland dealing with Ireland’s revolutionary period entitled ‘Imaging Conflict.’

Notes

1. Nail, Theory of the Border.

2. Graham, Northern Ireland, 17.

3. Ó Faoláin, I remember, 220.

4. Nash, Lorraine, and Graham, “Putting the Border in Place,” 423.

5. Moore, Birth of the Border.

6. See the following for the details of the Boundary Commission: Hand, “MacNeill and the Boundary Commission,” 201–75; and O’Callaghan, “Old Parchment and Water,” 27–55.

7. Vaughan-Williams, Border Politics.

8. Leary, “A House Divided,” 269–90.

9. This photograph is also reproduced in Toby Harnden’s controversial work: ‘Bandit Country’: The IRA & South Armagh, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1999, in which the caption notes that one member of the family becomes an IRA sniper and that another was shot dead by the Royal Marines in 1990.

10. Ziff, The Media and Northern Ireland, 195.

11. Ibid., 199.

12. Fine Art depictions of the Troubles and after are covered by the following: Graham, Northern Ireland; Tuck, After the Agreement; Long, Ghost-Haunted Land; and Legg, Northern Ireland and the Politics of Boredom.

13. McWhirter and Spencer, “Corporal Bell, IRA Target,” 30–36.

14. Graves, “In the Belly of the Pig,” 3.

15. Feldman, “Violence and Vision,” 29.

16. McCann, “The Eye of the Storm,” 33.

17. Freytag, “Border Crossings and Road Cratering.

18. Nail, Theory of the Border, 8.

19. O’Shea, Border Roads 1990–1994.

20. Tóibín and O’Shea, Walking along the Border.

21. Fitzpatrick, “eBay Press Prints,” 8.

22. Purbrick, British Watchtowers, 57.

23. Anderson, “Time Moves Both Ways,” 9–10.

24. Burke, Shooting the Darkness, viii.

25. Barber, “Introduction,” 120.

26. Carville, “Re-Negotiated Territory,” 9.

27. Dickson et al., Shooting the Darkness, 32–33.

28. See Cadwallader, Lethal Allies; and Urwin, A State in Denial.

29. Nolan has also worked with border communities in Carlingford Lough and Bessbrook, South Armagh.

30. Fitzpatrick, “Third Space,” 22.

Bibliography

- Abrahams, Mike. Borderlands 1984-1993. Southport: Café Royal Books, 2021.

- Abrahams, Mike, and Laurie Sparham. Still War: Photographs from the North of Ireland. Edited by Trisha Ziff. London: Bellew Publishing, 1989.

- Anderson, Darren. “Time Moves Both Ways.” In The New Frontier: Reflections from the Irish Border, edited by James Conor Patterson, 6–22. Dublin: New Island Books, 2021.

- Barber, Fionna. “Ghost Stories: An Interview with Willie Doherty.” Visual Culture in Britain 10, no. 2 (2009): 189–199. doi:10.1080/14714780902924922.

- Barber, Fionna. “Introduction: After the War: Visual Culture in Northern Ireland Since the Ceasefires.” Visual Culture in Britain 10, no. 2 (2009): 117–123. doi:10.1080/14714780902924351.

- Borderlines Project. Borderlines: Personal Stories and Experiences from the Border Counties on the Island of Ireland. Dublin: Gallery of Photography, 2006.

- Burke, Tom. “Introduction.” In Shooting the Darkness: Iconic Images of the Troubles and the Stories of the Photographers Who Took Them, edited by Dickson Trevor, Faith Paul, Lewis Alan, Stanley Matchett, Martin Nangle, Crispin Rodwell, and Hugh Russell, vi–ix. Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 2019.

- Cadwallader, Anne. Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland. Cork: Mercier Press, 2013.

- Carr, Garrett. The Rule of the Land: Walking Ireland’s Border. London: Faber & Faber, 2017.

- Carville, Justin. “Re-Negotiated Territory: The Politics of Place, Space, and Landscape in Irish Photography.” Afterimage 29, no. 1 (2001): 5–9. doi:10.1525/aft.2001.29.1.5.

- Collins, Jude. Laying It on the Line: The Border and Brexit. Cork: Mercier Press, 2019.

- Cousins, James A. Without a Dog’s Chance: The Nationalists of Northern Ireland and the Irish Boundary Commission, 1920–1925. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2020.

- Dickson, Trevor, Paul Faith, Alan Lewis, Stanley Matchett, Martin Nangle, Crispin Rodwell, and Hugh Russell. Shooting the Darkness: Iconic Images of the Troubles and the Stories of the Photographers Who Took Them. Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 2019.

- Doyle, Martin. Dirty Linen. The Troubles in My Home Place. Dublin: Merrion Press, 2023.

- Feldman, Allen. “Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror.” Public Culture 10, no. 1 (October, 1997): 24–60. doi:10.1215/08992363-10-1-24.

- Fitzpatrick, Orla. “eBay Press Prints.” Source Photographic Review no. 101 ( Summer 2020): 8–9.

- Fitzpatrick, Orla. “Third Space: An Interview with Kate Nolan.” Gorse, no. 11 (2022): 19–36.

- Freytag, Jan. “Border Crossings and Road Cratering by British Troops in the Aftermath of Internment without Trial and Its Effects on the Republic of Ireland.” Nordic Irish Studies 15, no. 2 (2016): 117–131.

- Gibbons, Ivan. Drawing the Line: The Irish Border in British Politics. London: Haus Publishing, 2018.

- Graham, Colin. Northern Ireland: 30 Years of Photography. Belfast: Belfast Exposed, 2013.

- Graves, Ralph. “In the Belly of the Pig.” LIFE Magazine 72, no. 6 (February 18, 1972): 3.

- Hand, Geoffrey. “MacNeill and the Boundary Commission.” In The Scholar Revolutionary: Eoin MacNeill, 1876-1945, and the Making of the New Ireland, edited by F.X. Martin and F. J. Byrne, 201–275. Shannon: Irish University Press, 1973.

- Leary, Peter. Unapproved Roads: Histories of the Irish Border, 1922–1972. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Leary, Peter. “A House Divided: The Murrays of the Border and the Rise and Decline of a Small Irish House.” History Workshop Journal 86, no. Autumn (2018): 269–290. doi:10.1093/hwj/dby024.

- Legg, George. Northern Ireland and the Politics of Boredom: Conflict, Capital and Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019.

- Long, Declan. Ghost-Haunted Land: Contemporary Art and Post-Troubles Northern. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

- MacDonald, Darach. Hard Border: Walking Through a Century of Partition. Dublin: New Island, 2018.

- McCann, Eamonn, and Evelyn Hofer. “The Eye of the Storm.” The Sunday Times Magazine, February 9, 1975, 26–43.

- McGilloway, Brian. “Walking the Tightrope: Brexit, Books and the Border.” The Irish Times, November 3, 2018.

- McKittrick, David. Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1999.

- McWhirter, William A., and Terence Spencer. “Corporal Bell, IRA Target.” LIFE Magazine 72, no. 6 (February 18, 1972): 30–36.

- Moore, Cormac. Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland. Dublin: Merrion Press, 2019.

- Mulroe, Patrick “Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror.” Public Culture 10, no. 1 (October, 1997): 24–60. doi:10.1215/08992363-10-1-24.

- Mulroe, Patrick Bombs, Bullets and the Border: Policing Ireland’s Frontier: Irish Security Policy, 1969–1978. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2017.

- Nash, Catherine, Denis Lorraine, and Graham Bryan. “Putting the Border in Place: Customs Regulation in the Making of the Irish Border, 1921–1945.” Journal of Historical Geography 36, no. 4 (2010): 421–431. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2010.01.004.

- O’Callaghan, Margaret. “Old Parchment and Water: The Boundary Commission of 1925 and the Copper Fastening of the Irish Border.” Bullan: An Irish Studies Journal 5, no. 2 (2000): 27–55.

- Ó Faoláin, Seán. I Remember, I Remember. London: R. Hart-Davis, 1961.

- Olley, Jonathan. Castles of Ulster. Belfast: Factotum, 2007.

- O’Shea, Tony. Border Roads 1990–1994. Southport: Café Royal Books, 2017.

- Purbrick, Louise. “Introduction.” British Watchtowers, edited by Donovan Wylie, 207. Göttingen: Steidl, 2007.

- Rolston, Bill, ed. The Media and Northern Ireland: Covering the Troubles. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1991.

- Taylor, John. War Photography: Realism in the British Press. London: Routledge, 1991.

- Tóibín, Colm, and Tony O’Shea. Walking Along the Border. London: Queen Anne Press, 1988.

- Tuck, Sarah. After the Agreement: Contemporary Photography in Northern Ireland. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015.

- Urwin, Margaret. A State in Denial: British Collaboration with Loyalist Paramilitaries. Cork: Mercier Press, 2016.

- Vaughan-Williams, Nick. Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

- Wylie, Donovan. British Watchtowers. Göttingen: Steidl, 2007.

- Ziff, Trisha. “Photographs at War.” In The Media and Northern Ireland: Covering the Troubles, edited by Bill Rolston, 187–207. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1991.