ABSTRACT

We identify four patterns of diffusion that are likely to explain how trends in death penalty usage spread among countries. The first is geographic proximity, which creates dependency relations between nations that in turn affect the spread of changes in death penalty regimes. The second is global diffusion, meaning processes that spread ideas globally. The third is cultural homogeneity, which can be expected to be conducive for diffusion; studies show that countries similar in terms of language and religion influence each other to a great extent. Finally, similar colonial heritage, which can establish cultural and institutional ties between countries. This study encompasses all independent countries of the world over the period 1800 to 2021. In addition to measures of diffusion, a number of control variables are introduced. Relationships are measured using statistical techniques complemented by qualitative analyses.

Introduction

Although capital punishment is a highly controversial and debated subject, surprisingly few studies exist in which authors aim to identify the determinants of death penalty usage globally. In studies that have been conducted, authors have generally focused on domestic factors, such as political institutions, party ideology, economic wealth, level of crime, law tradition, religion, and ethnic fragmentation. The focus on diffusion has been limited. A few studies have included regional diffusion as a control variable but without much theoretical elaboration or consideration of diffusion networks other than regions. Studies have shown that the use of the death penalty is regionally concentrated, indicating that geographic diffusion mechanisms appear to be at work, particularly within the European context.Footnote1 In addition, Linde has found that the abolition of capital punishment for child abusers is explained by reference to various types of diffusion mechanism,Footnote2 while Mooney and Lee have provided evidence that geographic diffusion affects death penalty policies within the United States.Footnote3 The literature is even more scarce when it comes to links between other forms of diffusion and the death penalty. A notable exception is Mathias, who put explicit focus on a pattern of global diffusion, explaining that abolition of the death penalty is connected to the spread of the global human rights regime.Footnote4

In this article, we test the hypothesis that the abolition of the death penalty is an outcome of cross-national diffusion within networks. These networks consist of countries that share characteristics such as a common colonial heritage, religion, or geographic location. The empirical analyses take advantage of a new dataset on death penalty usage, covering all currently existing states since the year 1800, or the year of independence. The empirical data consists of a much larger number of cases than those used in previous studies on death penalty usage. The results, which show that diffusion is strongly linked to the abolition of the death penalty, provide new knowledge about diffusion as a determinant by explaining the differentiated developments of abolition.

Death penalty usage

When examining death penalty usage, many options are available. On the one hand, we can operate with a strictly dichotomous variable, where countries that execute persons are confined to one category and all other countries to another. This would create a category that contains considerable variation. Another alternative could be to operate with quantitative measures of death penalty usage, where we would, for instance, attend to the number of crimes that are punishable by death or the number of executions a country undertakes in a given year. Since data on executions tends to be highly unreliable, highly sophisticated measures of death penalty usage cannot be applied; this problem is exacerbated when the study, like ours, covers long periods and diverse contexts.

The most common method of categorizing death penalty regimes is to apply Amnesty International’s classification system, in which countries are assigned to one of four categories.Footnote5 This categorization is based on regularly conducted surveys of death penalty usage undertaken by the United Nations since 1975. The first category consists of countries that are ‘abolitionist for all crimes’, meaning that the death penalty is forbidden in all circumstances. The second category comprises countries that are ‘abolitionist for ordinary crimes only’. In this group, the death penalty can be used ‘only for exceptional crimes such as crimes under military law or crimes committed in exceptional circumstances such as wartime’.Footnote6

Countries that do not fall within either of those two categories have death penalty statutes. Because many such countries do not apply the death penalty frequently, the two remaining categories separate countries that do not use the death penalty in practice from those that do. Countries in the third category are ‘abolitionist de facto’, meaning ‘they have not executed anyone during the past ten years or more, or … have made an international commitment not to carry out executions’.Footnote7 The fourth and last category consists of ‘retentionist’ countries, where the death penalty is allowed and executions have been carried out in the past 10 years.

In the framework of this study, we apply that categorization with two minor modifications. First, countries with death penalty statutes are considered de facto abolitionists if and only if they have not executed anybody for at least 10 years. Second, in the category of countries that are abolitionists for ordinary crimes only, a few have carried out death sentences; countries in which an execution has taken place on the past 10 years are confined to a separate category.

We treat the categorization as an ordinal scale of death penalty usage. Abolitionist countries constitute one endpoint, followed by countries abolitionist for ordinary crimes only, countries abolitionist for ordinary crimes only but where at least one execution under exceptional circumstances has occurred in the last 10 years, countries that are abolitionist de facto, and, finally, retentionist countries.

In the empirical analyses, we operate with two measures of abolition. The first, ‘complete abolition’, refers to a change from any form of death penalty usage to complete abolition for all crimes. The second, ‘stepwise abolition’, accounts for any change along the ordinal scale towards a more restrictive attitude towards the death penalty. Complete abolition and stepwise abolition overlap for cases that move from any category to complete abolition.

Diffusion of death penalty usage

In comparative research, ‘diffusion’ refers to processes where ideas about institutions or policies spread between countries.Footnote8 Since abolishing the death penalty requires a change of law through political decisions by political elites, we consider diffusion of death penalty abolition a form of policy diffusion. Studies in policy diffusion have identified several mechanisms that we assume will be important with regard to death penalty abolition.Footnote9 The first consists of altered payoffs. Here, the decisions of one government alter the conditions (the costs and benefits) of the policy in question for other governments. This mechanism works through material payoffs (e.g., economic benefits, tax laws), reputational payoffs (e.g., global norms, liberalization), and support groups (e.g., credibility or immunity on a practice). These are ways in which countries change their policies in order to adapt to changing conditions. The second mechanism consists of a process through which countries learn from each other through exchanges of information. As its point of departure, this takes a situation where decision makers lack the information they need to understand the effects of a specific policy, but can learn about the effects of policies from success cases (e.g., best-performing countries), through communication, and in cultural reference groups. A third mechanism of diffusion is coercion, whereby powerful countries influence weaker nations to adapt a certain policy. Coercive diffusion can involve both sticks and carrots, but it is always based on power asymmetry: a stronger state imposes its preferences on a weaker state. The fourth mechanism is emulation, meaning that a country imitates or reacts to policies of other countries. Powerful countries, international organizations, and expert groups may become role models by formulating ideas that become socially accepted among political elites. As our study covers all independent states in different contexts under a long period, we assume that various mechanisms have operated in the relationships between countries.

Policy changes clustered in time (waves) or space indicate policy diffusion. According to our data, on which we elaborate further in later sections, such clustering patterns exist in the abolition of the death penalty. These patterns make it reasonable to expect and examine the occurrence of death penalty diffusion between countries. Admittedly, conditions other than diffusion can cluster policies in time and space (e.g., domestic conditions or responses to international shocks),Footnote10 but ignoring the likelihood of diffusion can lead to ‘Galton’s problem’, i.e., an underestimation of the interdependence between countries and an overestimation of the effects of domestic conditions.Footnote11

Since studies on the death penalty abolition have not primarily focused on diffusion as a determinant, their theoretical contributions are rather limited and tend to have only a weak connection to comparative diffusion theories. Studies where diffusion is included among the explanatory variables generally focus on a single form of diffusion. For example, both Kim and Neumayer include regional diffusion as a control variable in their analyses.Footnote12 Their diffusion variable measures the proportion of countries that have completely abolished the death penalty in certain regions. To ensure that regional shares are not spuriously affected by global trends, they divide regional percentages by the global percentage of countries that have abolished the death penalty completely. Their empirical analyses show that regional diffusion has a positive effect on abolition.

Although regional diffusion appears to be significant for the abolition of the death penalty, it is only one of several forms of linkage between countries. In this study, we explore the importance of four forms of relationship between countries for the diffusion of death penalty abolition. These four relationships are selected with inspiration from the results of studies on democratic diffusion. We therefore regard them more as general networks for diffusion rather than as specific networks for death penalty abolition, and our empirical analyses will test whether diffusion networks for democratization have relevance for the abolition of the death penalty.

First, regional diffusion is included based on arguments about geographic proximity as a condition of diffusion. The theoretical reason for assuming proximity promotes diffusion is summarized in ‘Tobler’s First Law’: ‘Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distance things’.Footnote13 The basic argument is that countries have more connections with closely located countries than with remote ones, and that high levels of interaction promote diffusion between countries.Footnote14 Countries within the same regions are expected to have strong connections through cooperation, trade, communication, regional organizations or treaties, but also through institutional and cultural similarities.Footnote15

Second comes global diffusion, which consists of processes that spread ideas globally. Mathias has argued that death penalty abolition can largely be attributed to what he refers to as the ‘sacralization of the individual’: the position of the individual has been gradually enhanced through Judeo-Christian thought and the European Enlightenment, he writes, leading eventually to the development of the global human rights regime, in which the rights of the individual surpass the rights of the state. A natural consequence of this development, Mathias argues, is that a state is no longer deemed to have the right to punish its citizens by taking their lives, and this change in attitude towards the death penalty has manifested as increasing pressure towards worldwide abolition.Footnote16 It is well-established that international organizations in particular can be highly effective in creating global diffusion patterns by supporting policy reforms in member states or demanding that states that have applied for membership undertake such reforms to be eligible for inclusion.Footnote17 This is certainly the case with regard to the death penalty, as several international organizations (particularly the European Council and the UN) actively work to push states towards abolishing the death penalty. In his above-mentioned study, Mathias found that what he refers to as the ‘global institutionalization of the sacrality of the individual’, measured by the number of international nongovernmental human rights organizations and global human rights documents, was strongly and positively related to death penalty abolition.Footnote18

Third, ideas and policies are also likely to spread between countries that are culturally close to each other. Wong and Woodberry distinguish three aspects of cultural similarity, namely religion, language, and colonial heritage. They argue that interactions within culturally proximate countries are enhanced by factors such as homophily, organizational similarity, ease of communication, educational flows, and migration.Footnote19 With reference to Anderson’s notion of ‘imagined communities’, they further note that cultural proximity is likely to create emotional bonds between inhabitants who might be located very far from each other.Footnote20 The empirical evidence strongly supports the importance of cultural networks for the spread of democratization; all three indicators of cultural proximity are more strongly associated with the dependent variable than geographical proximity.Footnote21 In this study, cultural proximity is captured by networks based on colonial heritage and religion. Although linguistic similarity is likely to create strong ties and facilitate communication between countries, this variable is very closely connected to colonial heritage, and linguistic similarity is difficult to operationalize because of problems of delimitation: Should we focus only on native speakers or also on non-native speakers, for instance? How well should a non-native speaker know the language? When is a language considered a separate language?

Colonial heritage is not only more easily operationalized, but also widely cited as a plausible determinant of death penalty usage. In many cases, the colonial power exported their death penalty statutes to their colonies. In the African context, for instance, it has been argued that capital punishment as practiced today was introduced by the colonial powers and that in Southern Africa, the death penalty was virtually non-existent prior to colonization.Footnote22 A British colonial heritage in particular has been associated with a positive view of the death penalty, since the death penalty was historically more widely used in Britain than in continental Europe.Footnote23 Its popularity in the English-speaking countries in the Caribbean has been partly explained by the fact that the countries inherited the death penalty from their former colonizer and continued using it even after Britain became an advocate of the abolitionist movement.Footnote24 Within the framework of this study, a colonial heritage network is composed of countries that had the same former colonizer. In all, we make use of thirteen colonial networks.Footnote25 None of them include the former colonial power, because we aim to study to what extent death penalty policies spread among countries that share the same colonial heritage rather than assessing policy adoptions from the former colonial power to the former colonies.

Religious networks can be expected to be highly important for changes in death penalty policies. Wong and Woodberry provide a detailed account of how democracy spread in the Catholic world during the ‘third wave’ of democratization.Footnote26 As claimed by Mathias, it makes sense to expect a similar pattern with regard to death penalty abolition.Footnote27 Over the years, the Catholic Church has become an influential opponent of the death penalty and its revised Catechism—its official compilation of teachings—from 2018 bluntly states that capital punishment is ‘inadmissible’. An illustration of its impact on death penalty policies is the Philippines’ decision to abolish the penalty only days before a meeting between the country’s president and the Catholic pope in 2006.Footnote28 Other religious networks can be expected to be important as well. We believe this might particularly be the case in the Islamic world, as a substantial part of the countries with a Muslim majority, namely the ones situated in the MENA-region, not only share a common faith but also a common language, region, and history. Even the highly heterogeneous group of Protestant countries can be expected to influence each other because they are, in general, favorably disposed towards individualism and thus ‘more likely to institutionalize cultural models that protect, authorize, and empower the individual’.Footnote29

Emulation is the most relevant mechanism by which diffusion is expected to occur. This is especially the case with global diffusion. With reference to Mathias’ work discussed above, we find it evident that the sacralization of the individual is a norm evolved from the ideas and values of the European Enlightenment. Furthermore, international organizations, particularly the UN, have actively worked to convince political leaders that the death penalty is an obsolete punishment that is not acceptable in the modern world. Emulation is also the main driving force as death penalty policies spread regionally; with the global spread of the human rights regime, we expect these ideas to spread, and particularly among neighbouring countries. However, in the regional context diffusion can also occur by means of coercion. This is particularly the case in Europe, where the abolition of the death penalty in Eastern Europe has been largely attributed to the fact that Western European countries made it a requirement to join organizations such as the European Council and the European Union.Footnote30 We also expect diffusion among colonial networks to occur through emulation, especially since we do not include the former colonial power; the lack of asymmetry in the relationships between the countries means that diffusion through altered payoffs and coercion should be less relevant than if the former colonial power was included. To some extent, however, we expect learning processes to occur as political elites in the networks interact closely with each other. A common language often means that communication occurs at all levels in society. Learning and emulation are also relevant for the spread of death penalty policies within religious networks, but here an element of coercion is also involved, as religious authorities can have a profound impact on how political leaders position themselves towards the death penalty. The Vatican’s increasingly negative stance on the death penalty since the 1960’s is illustrative in this respect. In Islamic thought, the intertwinement of the religious and political spheres and reliance on Sharia can affect the freedom of restriction of the power holders.

Data presentation

The unit of analyses is country-year. The material consists of 19,010 country-year observations from 1800 to 2021. Due to the exclusion of states that have abolished the death penalty (n = 3,750) and lack of data for some control variables, the statistical analyses include 11,452 observations.Footnote31 The original dataset consists of 106 cases of complete abolition and 273 cases of stepwise abolition. The regression analyses contains 93 cases of complete abolition and 241 cases of stepwise abolition.

Our first measure of diffusion, global diffusion, refers to death penalty usage at the global level. The second measure, regional diffusion, accounts for death penalty usage in nineteen separate world regions based on the classification by the UN. Religion network diffusion refers to death penalty usage among countries with the same dominant religion. Colonial heritage networks diffusion, finally, accounts for death penalty usage in countries that have been under the rule of the same colonial powers. To calculate the share of countries within each of these four networks, we have, for each country-year and for each network, calculated the share of countries that have a) abolished the death penalty completely (for the analyses where complete abolition constitutes the dependent variable) or b) is situated in another category than retentionist (for the analyses where stepwise abolition constitutes the dependent variable). To indicate the external context of the specific country, we have excluded the country from the calculation. All measures of diffusion range from 0 to 100, where high values indicate a strong prevalence of abolition in the network and vice versa.

Admittedly, the interrelatedness of the indicators constitutes a challenge. presents factor analyses based on the two sets of diffusion indicators. The first factor analysis refers to diffusion indicators for complete abolition, while the second includes diffusion indicators for stepwise abolition. As we can see, strong correlations exist between the indicators. The variation among the diffusion indicators measures a common variation over 70 percent. Consequently, the outcome for all factor analyses is a one-dimensional solution with one factor for each analysis that measures the diffusion of complete or stepwise abolition respectively.

Table 1. Factor analyses of diffusion measurements

The strong correlations between the diffusion indicators are an expression of the fact that death penalty usage spreads simultaneously through multiple channels. In other words, states are exposed to diffusion from various networks that spread the same policy of death penalty usage. Furthermore, memberships in networks tend to overlap. shows the correlations between memberships in different networks. Although the memberships do not have a hierarchical structure, strong correlations exist between the memberships in terms of region, religion, and colonial background. To some degree, these correlations probably explain the strong correlation between the diffusion indicators.

Table 2. Overlapping membership in networks (symmetric lambda λ)

To partly remedy this shortcoming, we additionally merge the various diffusion measures to a single index of diffusion. Based on the outcomes of the factor analyses and the factor loadings of indicators, we have created indices that measure the share of death penalty abolition within the networks that countries are part of. The main advantage of this strategy is that we get a comprehensive indication of the general impact of diffusion while avoiding overestimation of a particular network’s significance. It also allows us to deal with problems of multicollinearity. However, it offers no indication of the effects of specific networks.

The analyses use lagged independent variables to increase confidence in the causal direction between the independent and dependent variables. Although the length of the temporal lag can have consequences for the outcome, there are no theoretical or empirical guidelines for the choice of temporal lag in previous research. We have lagged the index value up to five years. As a correlations matrix shows strong correlations over time (Pearson’s r is around or above 0.98 for all correlation pairs), we have chosen to present analyses that include index values lagged with one year. However, we have also conducted analyses with index values with other lags to explore the robustness of the results. The outcomes of these analyses do not deviate from the patterns observed in the main analyses.

Control variables

We include a number of control variables that we expect to have relevance for death penalty abolition. We expect level of liberal democracy to have a positive effect on the abolition of the death penalty. The main reason for this assumption is that democracy is built on the convention that all humans have inalienable rights, including the right to life. In democratic societies, this principle of human rights influences how penal systems are shaped, namely by replacing corporal punishment with prison terms.Footnote32 A potential link between democracy and the abolition of the death penalty has received support in many empirical studies.Footnote33 We measure the variable of liberal democracy with the V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index, which has been transformed to range from 0 to 100.

The second control variable indicates changes in the level of liberal democracy between two years, likewise measured using the V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index. The inclusion of this variable is based on the same theoretical arguments as the level of democracy. Although most studies include level of democracy only, Neumayer finds positive associations between democratic transition and death penalty abolition.Footnote34 In a similar manner, Kim concluded that political change that increases the democracy level has positive effects on the probability for abolition of the death penalty for all crimes.Footnote35

The third control variable concerns socioeconomic development, measured as GDP per capita (logarithmic). We expect socioeconomic development to foster higher levels of education and thereby a tendency to regard the death penalty as a cruel punishment unfit for modern societies.Footnote36 However, there are also theoretical arguments for an opposite direction of association, based on the assumption that powerful countries are more likely than weak countries to resist pressures from the abolitionist movement and therefore have the capacity to uphold the death penalty.Footnote37 Empirical results are equivocal: some studies have found positive associations,Footnote38 while others have not detected any associationFootnote39 between socioeconomic development and death penalty abolition.

This makes it necessary to introduce a fourth control variable, state power. The inclusion of this variable builds on the assumption that powerful states in particular are able to resist external pressures for abolition. Kim, for instance, detects a strong negative effect of state power on the probability of the abolition of the death penalty for all crimes.Footnote40 For this study, we use the same indicator as Kim to measure state power, namely the Composite Indicator of National Capability (CINC), which includes six indicators of state power: military expenditure, military personnel, energy consumption, iron and steel production, urban population, and total population.Footnote41 To simplify the interpretation of this index, we have multiplied the CINC-value by 10,000.Footnote42

A recurrent argument in the scholarship suggests that countries influenced by the British common-law tradition should have a more restrictive view of the death penalty than countries with a civil-law tradition. The rationale for this is that common law as a tradition is connected to individual rights and limited government, while civil law tradition aims to strengthen sovereigns’ control over their citizens.Footnote43 However, empirical studies have tended to find support for an opposite association between common law and death penalty abolition. A plausible explanation for this finding is that the principles of individualism embedded in the common law tradition favour more moralistic and sanctioning systems.Footnote44 Based on Greenberg and West, we include a control variable with dichotomous scale that distinguishes the common law tradition from all other law traditions.Footnote45

The last control variable concerns religion. Although empirical results have not been uniform, some studies conclude that countries with a Muslim majority population are more likely than other countries to uphold the death penalty.Footnote46 The inclusion of Islam as a control variable is primarily motivated by our understanding of the role Islam exercises in the formation of penal law in Muslim countries and by statements some Muslim representatives have made at the UN drawing a connection between Islam and the death penalty.Footnote47 Based on this, we include a variable that codes countries where Muslims constitute the largest religious denomination as 1 while other countries are coded as 0.

Method of analyses

As the dependent variables have a dichotomous structure, we used logistic regression models to test the importance of diffusion for death penalty abolition. Logistic regression allows us to analyse the effects of diffusion on the probability of the occurrence of abolition when the model includes several diffusion variables and control variables. It opens for comparisons of the effect magnitudes between the diffusion variables. Logistic regression does not assume a linear relationship between variables, which is essential as diffusion can have non-linear forms of effect (e.g., S-forms).Footnote48 It can also analyse dependent variables with strong skewness in the distribution of cases, which occurs in our population as abolition is a relatively rare occurrence.

In addition to the initial analyses covering the whole time period, we investigate potential differences in diffusion effects between two major periods (1800–1979 and 1980–2021). We use a period-split design that presents separate analyses for each period. An alternative to this design would be to use models with interaction terms, but this would requires creating an interaction term for each diffusion indicator, which results in problems of multicollinearity, as all interaction terms would use the same period variable (i.e., diffusion indicator * period variable). Although the period-split design divides the observations into subsamples, it allows us to compare the diffusion effects between the two periods.

Empirical findings

A bird’s-eye view

and present results from two logistic regression analyses. The first set of regressions accounts for whether the death penalty has been completely abolished or not in a given year. The second set of regressions registers whether a country has moved towards abolition along the scale, regardless of between which points along the scale the movement has occurred.

Table 3. Explaining complete abolition of the death penalty 1800–2021. Logistic regression analyses

Table 4. Explaining stepwise abolition of the death penalty 1800–2021. Logistic regression analyses

With respect to the first set of regressions (), we note that diffusion is of high importance for death penalty abolition. All measures of diffusion are separately linked to the dependent variable, as is the combined index of diffusion. Based on the results of model 6, regional networks appear to be the most important network for explaining the complete abolition of the death penalty. Among the control variables, democracy and state power are consistently linked to death penalty abolition in the expected directions, whereas GDP appears to be completely irrelevant. A common law heritage is negatively associated with death penalty abolition, but this relationship disappears when diffusion based on colonial heritage is included in the regressions. With regard to the second set of regressions (), which accounts for stepwise trends towards abolition, results are more or less identical to those observed in , although the models explain less of the variance in the dependent variable.

The most striking finding is that regional networks are more important than other networks (global, religious, and colonial heritage) for explaining death penalty abolition. As we have, seen, closeness to abolitionist countries in Western Europe explain why Eastern European countries abandoned the death penalty en masse in the 1990s, and similar patterns appear to be discernible in other regions in the world. However, before drawing far-reaching conclusions about this relationship, however, we need to recall the strong correlations between our various diffusion indicators.

The negative relationship between state power and death penalty abolition provides strong support for Neumayer’s argument that powerful states in particular are likely to resist demands for abolition.Footnote49 The fact that democracy is positively related to death penalty abolition is as we expected, and is in line with findings from other studies in the field. The negative association between common law tradition and abolition detected in some of the regressions are in line with results obtained by Greenberg and West as well as by Neumayer.Footnote50 Finally, we find the lack of association between Islam and the abolition of the death penalty interesting, given that bivariate findings have shown that complete abolition is strongly linked to religion.Footnote51

Two periods

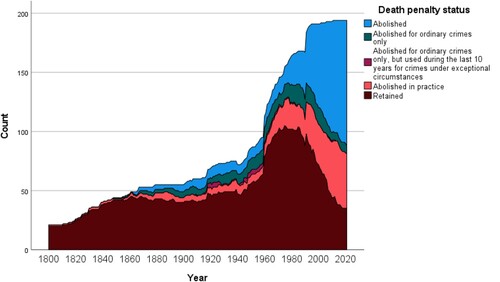

Since the study includes all countries over more than 200 years, we can assume that the relevance of the independent variables differs between periods. provides a presentation of how the use of capital punishment has changed since 1800. Until the mid-1800s, the death penalty was used all over the world. San Marino abolished it for ordinary crimes in 1848. Peru abolished the death penalty in 1956, only to reintroduce it four years later, abolish it again in 1867, and reintroduce it again later in same year. In 1863 Venezuela and Colombia abolished the death penalty for all crimes, although Colombia restored it in 1886. San Marino (1865), Costa Rica (1877), Ecuador (1897), Uruguay (1907), Panama (1903) and Colombia (1910) followed suit.Footnote52 In 1900, 73 percent of countries applied the death penalty and 11 percent were completely abolitionist; nine percent had abolished it for ordinary crimes only, and seven percent had stopped carrying out executions.

During most of the 20th century, the proportion of countries situated in our categories remained fairly stable. For example, the shares for the five categories in 1970 were 70 percent (retained), 13 percent (abolished in practice), 1 percent (abolished for ordinary crimes, but used during the last 10 years), 6 percent (abolished for ordinary crimes only), and 9 percent (completely abolished). During the 1970s, however, the death penalty began to lose its popularity fast. In 2021, the last year covered by the database, the shares for the categories changed to 18 percent (retained), 24 percent (abolished in practice), 0 percent (abolished for ordinary crimes, but used during the last 10 years), 4 percent (abolished for ordinary crimes only), and 55 percent (abolished). It is worth pointing out that at the country level, this development has not always been linear: in some countries the death penalty was completely abolished only to be reintroduced again later. For example, Honduras has abolished death penalty three times, while Argentina, Colombia, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, and Switzerland have done so twice.

Critical mass theories claim that diffusion starts after a mass of cases is reached, and that the speed increases when the number of cases surpasses a critical threshold.Footnote53 Since the abolitionist wave did not start until the mid-1970s, it makes sense to split up the population into two time periods. We therefore proceeded to conduct separate analyses for the periods 1800–1979 and 1980–2021 respectively. The results, shown in and , are revealing in several respects.

Table 5. Explaining complete abolition of the death penalty in two periods. Logistic regression analyses

Table 6. Explaining stepwise abolition of the death penalty in two periods. Logistic regression analyses

Our first observation is that the odds ratios for the index of diffusion are much higher in the previous time period than in the later one, indicating that the marginal effects of diffusion were stronger during the first period, when the share of countries that had abolished the death penalty was very low, than in the second period. During the earlier period, diffusion based on colonial networks are also of relevance for the complete abolition; we further detect a strange negative association between global diffusion and the complete abolition. A plausible explanation for this result is that many new states with death penalty statutes emerged during the period in question while at the same time very few countries were abolishing the death penalty completely. This means that the global share of countries that have abolished the death penalty decreases as we move along the time axis. In the later period, diffusion based on regional networks is the most important dimension of diffusion for death penalty abolition. The two measures of democracy are important in both periods. However, state power loses its predictive power during the later period.

In we use stepwise abolition as the dependent variable, and the results are slightly altered. The index of diffusion is significantly associated with death penalty abolition in both periods, but none of the specific diffusion networks is independently associated with death penalty abolition in any of the time periods. Regarding the control variables, state power is consistently and negatively associated with death penalty abolition. Change of democracy level is linked to the dependent variable at both points in time, whereas the overall level of democracy fails to reach the level of significance in all regressions during the period 1800–1979. Interestingly enough, we now find a negative association between Islam and death penalty abolition during the earlier time period.

It is evident that the limited number of cases of death penalty abolition during the first time period makes it difficult to draw any far-reaching conclusions based on the regression analyses. Instead, the analyses must be complemented with a more qualitative line of action. First, we found it somewhat striking that geographical diffusion appears to be unimportant for complete abolition. A quick glance at the data shows that during the first 180 years, abolition occurred almost exclusively in Western European or Latin American countries. Twenty-five countries in these regions abolished the death penalty completely: Argentina, Austria, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Finland, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Iceland, Luxembourg, Monaco, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Peru, Portugal, San Marino, Sweden, Switzerland, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The only countries that abolished the death penalty outside these regions were Sri Lanka (1954) and Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and Tuvalu which were abolitionist when they gained independence. Sri Lanka, however, reintroduced capital punishment in 1957. The lack of association is perhaps explained by the fact that we operate with numerous (19) regions, combined with the low number of abolitionist countries.Footnote54 For instance, of the first 10 instances where the death penalty was abolished, eight occurred in Latin America, whereas no cases where registered in 16 regions. In other words, geographic diffusion was important, but only in the Latin American context. With regard to religion, again, findings reveal that all countries but one, namely Buddhist Sri Lanka, were dominated by Western Christianity. Yet approximately three quarters of Protestant or Catholic countries continued to keep death penalty statutes in force by the year 1979.

Turning to countries that have taken measures towards abolition along the ordinal scale during the same period, our findings remain largely unaltered. In all, there are 104 such cases in 51 countries. Thirty-seven countries are situated in Western Europe or Latin America, but all continents are now represented: steps towards abolition have also been taken in Eastern Europe (Romania, Russia), Asia (Bhutan, Israel, Nepal, Sri Lanka), Africa (Seychelles, Senegal), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, Fiji), and North America (Canada). The list reveals that all major world religions are represented in these 180 years, but that the overwhelming majority of the countries are dominated by adherents of Western Christianity and that there is only one case of a step towards abolition in a Muslim country is found’ namely Senegal, which went from retentionist to abolitionist in practice in 1977.

Discussion

Our analyses have provided strong support for the assumption that diffusion mechanisms are important for explaining why countries abolish the death penalty. In general, the evidence suggests that networks based on geographic proximity are important. At the same time, the relevance of diffusion varies extensively, not only between different periods but also with regard to how death penalty abolition is operationalized. With regard to complete abolition, regression analyses showed that diffusion based on geography and religious networks were completely irrelevant in the period 1800–1979. Yet qualitative analyses showed that all abolitions of the death penalty during this period occurred in Protestant or Catholic countries, situated in Western Europe or Latin America. Our careful interpretation of the results indicates that geographic diffusion has been important, but only in the Latin American and European contexts. We found Christianity to be historically linked to death penalty abolition, but that Christian countries were still far more likely to apply the death penalty than to be abolitionist.

Generally, our indices of diffusion have a higher explanatory value in the earlier period than in the later one. We find this odd, given that international pressure for the abolition of the death penalty has grown in strength in recent decades especially; we thus expected countries to find it more and more difficult to resist pressures for death penalty abolition. However, a conclusion that diffusion loses its importance as we move forward along the time axis is probably too hasty. True, with regard to the complete abolition of the death penalty, we note that the odds ratios for the index of diffusion is much higher in 1800–1979 than in 1980–2021. The marginal effects of diffusion decrease when the number of abolitions increase, which is in accordance with the S-pattern of diffusion identified in many studies on diffusion.Footnote55 Although the marginal effects are low, a high share of abolitions produces a higher probability for death penalty abolition during the second period than the first. But this is also a reflection of the fact that in the earlier period, the total number of abolitions was very small and the overwhelming majority occurred in Latin America. Here, we found that diffusion based on geography, colonial networks (Spain), and religion (Catholicism) coincided.

Among the measures of diffusion, regional networks in particular were associated with diffusion of death penalty abolition. This finding is well in line with results from other studies in which regional diffusion has been found to be relevant for death penalty abolition.Footnote56 As our analyses also include diffusion networks other than regional ones, however, the results from our study indicate that it is necessary to further elaborate on the relationship between regional diffusion and death penalty abolition. As we have seen, regional networks overlap with other diffusion networks; analyses that include only regional networks will therefore overestimate the effect of regional diffusion, as this measure also contains effects from other networks. This finding is an important contribution to the literature on determinants of death penalty abolition.

The relationship between diffusion based on colonial networks and death penalty abolition is another important contribution. However, not all colonial networks are necessarily of equal importance for explaining death penalty abolition. This is especially the case with regard to the statistically significant association between colonial network diffusion and complete abolitions of the death penalty during 1800–1979, which we see as more or less completely driven by a link between Spanish colonial heritage and abolition. Clearly, the relationship between regional networks, colonial heritage, and death penalty abolition needs to be scrutinized in more detail, preferably in qualitative case studies.Footnote57

Finally, among the control variables, democracy and state power were linked to death penalty abolition in the directions we expected. In terms of complete abolition of the death penalty, however, state power lost its predictive value in 1980–2021. This is perhaps an indication that even the world’s most powerful countries are not immune to pressures for abolition, but as long as the death penalty is in use in US, China, India, and Japan, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that very powerful states still resist pressures for abolition.

This study has shown that diffusion constitutes an important requisite of death penalty abolition. Much in line with results from studies on democratization, we have seen that geographic diffusion alone does not capture all relevant patterns of transmission of death penalty policies within networks. Moreover, by making use of a unique dataset, we have shown that the relevance of diffusion varies over time. Although the extensive period covered by the study has provided important information of the role of diffusion at different periods of time, operating with such an extensive dataset also creates challenges and limitations. Since our study is global and extends over two centuries, it is not possible to control for all plausible explanations of death penalty abolitions. For one thing, we need reliable data on relevant independent variables; for another, the indicators we operate with should be comparable across countries and over time. This requirement makes it difficult to operate with ideological variables, such as the left-right dimension, which plausibly affects the choice to apply or abolish the death penalty.Footnote58 Reliable and comparable data on crime rates, too, would be of value, as we might expect countries with high crime rates to be reluctant to abolish capital punishment.Footnote59 Finally, like so many other studies, we have not been able to include the political actor perspective. The personal attitudes of power-holders towards the death penalty are often crucial for decisions to retain, abolish, or reintroduce the death penalty.

Main sources

Death penalty usage:

Hood and Hoyle, The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective; Schabas, The International Sourcebook on Capital Punishment; United Nations: Capital Punishment, Report of the Secretary-General, E/5616; E/1980/9; E/1985/43; E/1990/38. Amnesty International: Annual Reports 1976-2021.Wikipedia: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital-punishment-by-country> accessed 16 February 2024; Clarence H. Patrick, ‘The Status of Capital Punishment: A World Perspective’ (1965) 56(4) Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Political Science 397; Lee E. Deets, ‘Changes in Capital Punishment Policy since 1939’ (1948) 38(6) Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 584

Legal system:

University of Ottawa, ‘Juriglobe’ <https://www.juriglobe.ca> accessed 16 February 2024.

Religion:

David Barrett, George Kurian and Todd Johnson (eds), World Christian Encyclopedia (Oxford University Press 2001); Gina A. Zurlo and Todd M. Johnson, eds. World Christian Database (Brill 2024). ; U.S. Department of State International Religious Freedom Reports, <http://www.state.gov.international-religious-freedom-reports> accessed 16 February 2024; CIA World Factbook <http://cia.gov/the-world-factbook> accessed 16 February 2024.

Liberal Democracy Index, GDP/capita:

V-Dem Database, version 12 <http://www.v-dem.net> accessed 16 February 2024; Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2020), ‘Maddison Style Estimates of the Evolution of the World Economy. A new 2020 update’<http://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/publications/wp15.pdf> accessed 16 February 2024.

Colonial heritage:

Paul R. Hensel (2018) ‘ICOW Colonial History Data Set, version 1.1’ <http://www.paulhensel.org/icowcol.html> accessed 16 February 2024.

State power:

‘National Material Capabilities, version 6’ <https://correlatesofwar.org/data-sets/national-material-capabilities> accessed 16 February 2024.

Notes

1 Eric Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition and the Ratification of the Second Optional Protocol’ (2008) 12(1) The International Journal of Human Rights 3; Eric Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations of the Global Trend Towards Abolition’ (2008) 9(2) Human Rights Review 241; Anthony McGann and Wayne Sandholtz, ‘Patterns of Death Penalty Abolition, 1960–2005: Domestic and International Factors’ (2012) 56(2) International Studies Quarterly 275; Dongwook Kim, ‘International Non-governmental Organizations and the Abolition of the Death Penalty’ (2016) 22(3) European Journal of International Relations 596.

2 Robyn Linde, The Globalization of Childhood (Oxford University Press 2016).

3 Christopher Mooney and Mei-Hsien Lee, ‘The Temporal Diffusion of Morality Policies. The Case of the Death Penalty: The Case of Death Penalty legislation in the American States’ (1999) 27(4) Policy Studies Journal 766.

4 Matthew D. Mathias, ‘The Sacralization of the Individual: Human Rights and the Abolition of the Death Penalty’ (2013) 118(5) American Journal of Sociology 1246.

5 E.g. Roger Hood and Carolyn Hoyle, The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective, 5th ed. (Oxford University Press 2015).

6 William A. Schabas (ed.), The International Sourcebook on Capital Punishment (Northeastern University Press 1997, 241).

7 ibid 242

8 Nathaniel Beck, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch and Kyle Beardsley, ‘Space Is More than Geography: Using Spatial Econometrics in the Study of Political Economy’ (2006) 50(1) International Studies Quarterly 27; John O´Loughlin, Michael D. Ward, Corey L. Lofdahl, Jordin S. Cohen, David S. Brown, David Reilly, Kristian S. Gleditsch and Michel Sin, (1998). ‘The Diffusion of Democracy’ (1998) 88(4) Annals of the Association of American Geographers 545; Harvey Starr and Christina Lindborg, ‘Democratic Dominoes Revisited’ (2003) 47(4) Journal of Conflict Resolution 490; Michael D. Ward and Kristian S. Gleditsch, Spatial Regression Models (Sage 2008); Barbara Wejnert, Diffusion of Democracy: The Past and Future of Global Democracy (Cambridge University Press 2014).

9 Dietmar Braun and Fabrizio Gilardi, ‘Taking ‘Galton’s Problem’ Seriously: Towards a Theory of Policy Diffusion’ 18(3) Journal of Theoretical Politics 298; Zachary Elkins and Beth Simmons, ’On Waves, Clusters, and Diffusion: A Conceptual Framework’ (2005) 598 The Annals of the American Academy 33; Robert J. Franzese and Jude C. Hays, ‘Interdependence in Comparative Politics: Substance, Theory, Empirics, Substance’ (2008) 41(4/5) Comparative Political Studies 742; Beth A. Simmons, Frank Dobbin and Geoffrey Garrett, ‘Introduction: The International Diffusion of Liberalism’ (2006) 60 (4) International Organization 781; Beth A. Simmons and Zachary Elkins, ‘The Globalization of Liberalization: Policy Diffusion in the International Political Economy’ (2004) 98(1) American Political Science Review 171.

10 Elkins and Simmons (n 9); Christian Houle, Mark A Kayser and Jun Xiang, ‘Diffusion or Confusion? Clustered Shocks and the Conditional Diffusion of Democracy’ (2016) 70 International Organization 687.

11 Braun and Gilardi (n 9); Marc Howard Ross and Elizabeth Homer, ‘Galton’s Problem in Cross-National Research’ (1976) 29(1) World Politics 1; O´Loughlin et al. (n 8).

12 Kim (n 1); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’; Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

13 Waldo R. Tobler, ‘A Computer Movie Simulation of Urban Growth in the Detroit Region’ (1970) 46 Economic Geography 236.

14 Beck et al. (n 8); Elkins and Simmons (n 9); Franzese and Hays (n 9); Ross and Homer (n 10).

15 Beck et al., ‘Space is More than Geography’; O’Loughlin et al., ‘The Diffusion of Democracy’; Starr and Lindborg (n 8); Jan Teorell, Determinants of Democratization (Cambridge University Press 2010); Wejnert (n 8).

16 Mathias (n 4).

17 Gleditsch and Ward, ‘Diffusion and the International Context of Democratization’ (2006) 60(4) International Organization 911; Teorell (n 15); Barbara Wejnert, (2005). ‘Diffusion, Development, and Democracy, 1800–1999’ (2005) 70(1) American Sociological Review 53.

18 Mathias (n 4).

19 Wong and Woodberry, ‘Who is My Neighbor?’ Cultural Proximity and the Diffusion of Democracy’ Paper presented at the Conference of the American Political Science Association in San Francisco, September 2015.

20 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso 2006); Wong and Woodberry (n 19).

21 Wong and Woodberry (n 19); also Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations (Free Press 2003)

22 William A. Schabas, ‘African Perspectives on Abolition of the Death Penalty’ In: Schabas, W. (ed.) The International Sourcebook on Capital Punishment, (1997) Northeastern University Press, 33-34.

23 Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’ 11

24 Julian Knowles, ‘Capital Punishment in the Commonwealth Caribbean: Colonial Inheritance, Colonial Remedy?' In Hodgkinson, P, Schabas W. A. (eds) Capital Punishment: Strategies for Abolition, Cambridge University Press 2004.

25 These networks are former colonies of Austria-Hungary, Belgium, China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Russia/ Soviet Union, Spain, the Ottoman Empire, and United Kingdom.

26 Wong and Woodberry (n 19).

27 Mathias (n 4).

28 ‘Arroyo Repeals Death Penalty Law in Advance of Papal Audience,’ The Union of Catholic Asian News, June 26, 2006.

29 Mathias (n 4) 1254

30 Rick Fawn ‘Death Penalty as Democratization: Is the Council of Europe Hanging Itself?’ (2001) 8(2) Democratization 69.

31 The missing data for control variables concern mostly micro-states and some historical periods (before 1900).

32 Corey Brettschneider, ‘Dignity, Citizenship, and Capital Punishment: The Right of Life Reformulated’ (2002) Studies in Law, Politics and Society 25 119; Robert A. Burt, ‘Democracy, Equality, and the Death Penalty’, In Shapiro, Ian (ed), The Rule of Law, (1994) New York University Press; Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’.

33 Carsten Anckar, Determinants of the Death Penalty: A Comparative Study of the World (Routledge 2004); David Greenberg and Valerie West, ‘Siting the Death Penalty Internationally’ (2008) 33(2) Law & Social Inquiry 295; Mathias (n 4); McGann and Sandholtz (n 1); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’; Rick Ruddell and Martin Urbina, ‘Minority Threat and Punishment: A Cross-National Analysis’ (2004) 21(4) Justice Quarterly 903.

34 Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

35 Kim (n 1).

36 Anckar (n 33); Mathias (n 4).

37 Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’.

38 Mathias (n 4); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

39 Greenberg and West (n 33); McGann and Sandholtz (n 1).

40 Kim (n 1).

41 J David Singer, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey, (1972). Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965. In Russett, B. (ed) Peace, War, and Numbers (1972) Sage; J. David Singer, (1987) ‘Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of States, 1816-1985’ (1987) 14(1) International Interactions 115.

42 The construction of CINC produce small vales, which gives very high regression coefficients that are difficult to interpret. The original values for CINC range from 2.594*10−7 to 3.839*10−1.

43 Greenberg and West (n 33); Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishy, ‘The Quality of Government’ (1999) 3(1) Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 222.

44 Greenberg and West (n 33); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

45 Greenberg and West (n 33).

46 Anckar (n 33); Mathias (n 4); McGann and Sandholtz (n 1); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’; Chan S. Suh, ‘Democracy and the Making of Contentious Policy: The role of Democracy in the Abolition of the Death Penalty, 1950–2010’ (2015) 56(5) International Journal of Comparative Sociology 314.

47 Bertil Dunér and Hanna Geurtsen, ’The Death Penalty and War’ (2002) 6(4) International Journal of Human Rights 1; Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

48 Rogers (n 21).

49 Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’.

50 Greenberg and West (n 33); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

51 Carsten Anckar, ‘Why Countries Choose the Death Penalty’ (2014) (21) The Brown Journal of World Affairs 7.

52 During the 19th century the death penalty was also abolished in Switzerland (1874), Nicaragua (1893) and Honduras (1894) but subsequently reintroduced.

53 Rogers (n 21).

54 However, we also tested alternative classifications, with 5 and 10 regions, but results of these analyses showed that regional diffusion lacks significant effect. The lack of such effects is also explained by the strong correlations between the diffusion indices (Table 1).

55 Daniel Brinks and Michael Coppedge, ‘Diffusion is no Illusion: Neighbour Emulation in the Third Wave of Democracy’ (2006) 39(4) Comparative Political Studies 463; Gleditsch and Ward (n 17); Rogers (n 21).

56 Kim (n 1); Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty Abolition’; Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

57 In the analyses above, we have controlled for whether countries have a common law tradition or not. One could also assume that diffusion based on law traditions network are of importance for death penalty abolition. Since law tradition networks overlap strongly with networks based on colonial heritage, however, both diffusion variables cannot be included in the regressions. Furthermore, theoretically, the relationship between diffusion based on a common law tradition and death penalty abolition is far from uncomplicated. Whereas it can be easy to understand how ideas and policies spread between neighbouring countries and between countries that share a common language or religion, it is less obvious how a particular law tradition would constitute a favourable environment for similar interactions between nations. This is especially the case for the group of countries with a civil-law tradition, which consists of 75 countries and is highly heterogeneous, incorporating countries like Albania, Belgium, Chile, Kazakhstan, and Vietnam. The group of common-law countries is composed of more homogeneous countries. However, it is far from evident that law tradition would constitute the crucial element for the spread of death penalty policies between the entities. This is mainly due to the fact that colonial heritage and law tradition are highly intertwined, as all countries with a common-law tradition have been under British influence, either as a British colony as defined in the source used or in other respects.

58 Neumayer, ‘Death Penalty: The Political Foundations’.

59 Ibid.