?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

An increasingly large number of Western youth suffer from impaired general well-being and mental health. This is not least compounded by inappropriate use of psychological concepts and methods. They are trying to get a grip on life by, first of all, using psychology in a psychologizing way, which – contrary to the intention – creates an impaired image of one’s self and life, and which is nonpractical, because it is difficult to operationalize and does not point towards what actually can be done to get a good enough grip on own and common life. In this article, we discuss the danger of this inclination for psychologizing and introduce a psychological method which may avoid the psychologizing pitfalls. A research study is presented showing whether high school students can make use of the method, as well as the effect of their use of the method regarding mental health in the form of experienced stress, general well-being, and sense of coherence in life.

Vulnerability in youth

The general well-being and mental health situation of Western youth seems to deteriorate year by year.

Nine million European young people (aged 10 to 19) are living with a mental disorder, of which anxiety and depression account for half of the cases (UNICEF Citation2022 and EU (the European Union), Citation2022). In the USA, 37% of 12-to-17-year-olds suffer from persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness (CDC, Citation2022). In 2018, an average of 13% of all Nordic young people (Iceland, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) aged 18 to 23 reported mental distress or unhappiness. The manifest form of distress experienced was stress, depression, anxiety, self-harm, the use of antidepressant drugs, and in extreme cases suicide (NCM, Citation2022).

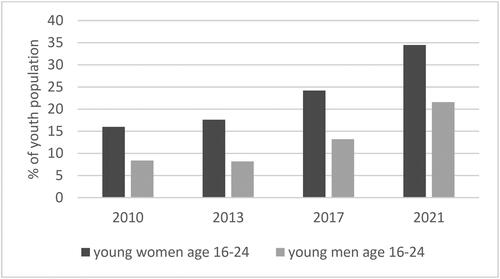

The World Health Organization’s definition of mental health reads: “Mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders […] Mental health is a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (WHO, Citation2022). The Danish Health Authority adopted this definition as starting point in their research study of mental health among Danish youth over the past 10 years, from 2010 to 2021. The research study showed that the score on a mental health scale for young people has been exacerbated significantly and, in particular, that no less than 35% of young women reported mental health problems in 2021 (see ).

In continuation of WHO's definition can be concluded that some kind of empowerment initiative is called for (cf. Freire, Citation1970). Here we understand empowerment as being helped with regard to freedom, power, and directedness of critical constructive contribution to creation, maintenance, and development of own and common life, in a well-being and health-promoting way (Bertelsen, Citation2022).

Using psychology may form part of the solution. That is, essentially by helping to personally understand, scientifically explain, and in practice assist with empowerment in relation to being able to participate in a critical-constructive way in social, cultural, and societal communities in general, and in relation to mental well-being and health in particular. In short, helped to what can be called a good enough grip on own and common life (Bertelsen, Citation2013, Citation2022).

Then again, using psychology may form part of the problem. That is, in fact it may not only impair opportunities for empowerment and a good enough grip on life, it may also contribute to reducing well-being and worsening mental health, not least among young people (Katznelson et al., Citation2022). This may occur in cases of the problematic and improper use of psychology known as psychologization. No clear consensus exists on what should be understood by the term psychologization. But De Vos (Citation2014) suggests that psychologization may be understood as the spreading of the discourse of psychology beyond its alleged disciplinary borders.

Firstly, we take a critical-constructive look at psychologization as a significant pitfall in the use of psychology. Psychology used in a wrong and nonpractical way may contrary to the intention lead to reduced well-being. It will contribute to worsening mental health. Secondly, we take a look at a particular psychological intervention technique, that is, the Life Psychological method (LP method) and how this type of intervention may avoid the pitfalls of psychologization, and how the LP method can, on the contrary, contribute to empowerment, well-being, and improved mental health. In short, the LP method provides a proposal for how the empowerment potential of psychology can be maintained and used in accordance with WHO’s understanding of mental health.

Hence, we want to test the LP method in its capacity as a non-psychologizing and practical use of psychology. We also want to test whether and how the LP method has a positive effect on well-being and mental health based on the parameters stress, well-being, and the experience of own and common life as coherent and meaningful.

Psychology: empowerment or psychologization

Psychology is double-sided

First of all, let us take a look at the understanding of psychology on which this research study is based (cf. Bertelsen, Citation2013). On the one hand, seen from an inward-and-out perspective psychology is fundamentally concerned with our way of thinking, our feelings, and our motivation. Psychology deals with how we translate this into actions and ways of relating to things, by which we deal with the small and major challenges and problems we are facing in our own and common life, as well as in everyday life and in the great choices of life. Through our actions and ways of relating to things, we unfold ourselves and express ourselves. On the other hand, psychology is concerned with how nature as well as the social, cultural, and societal systems constitute our opportunities and conditions. Seen from the outside-and-in, it deals with how external opportunities and conditions shape and affect as well as develop, create, and direct our relationship to ourselves and the directedness in our way of thinking and acting in relation to the surrounding world and our own and common life. In this sense the outside world makes an impression on us and is embedded in our thoughts, feelings and wishes for ourselves, each other and our own and common life.

Because psychology is not just concerned with anonymous impersonal psychological and societal structures and functions, but with participants who make conscious choices about the creation, maintenance, and further development of own and common life, we recapture this double-sidedness in the form of the intentionality in our perceptions and actions. Our intentionality is double-sided. From the inside-and-out, intentional agency has the form of intentio. When formed by our wishes, hopes and dreams, we proactively and prospectively direct our perceptions and actions at the outside world and the life we want for ourselves and together with others. Seen from the outside-and-in our intentional agency is in the form of intentum, that is, the fact that we must relate in a realistic, preferably critical– constructive way to the actual opportunities and conditions in life. In this sense, we are directed by the outside world and the existing life opportunities as a point of departure in life (Bertelsen, Citation2005).

Overall, it can be said that psychology is concerned with the way in which we as human beings are intentionally directed at/by the outside world, each other and ourselves. Psychology’s contribution to empowerment is precisely to strengthen, develop, and establish this double-sidedness. That is, to empower the intentional way in which we in a proactive and prospective manner can relate in a realistic critical-constructive way to our opportunities and conditions with a view to establishing, maintaining, and further developing our own and common life. Thus, psychology may significantly contribute to countering the vulnerable position that many young people find themselves in with negative consequences as to their well-being and mental health.

Psychology as such is a personal and social resource by which we through interdisciplinary collaboration with other social and human sciences may be able to approach the complex biopsychosocial structures and dynamics that make human life possible. However, as is the case for all sciences, some pitfalls may derail the use of psychology, and as mentioned above this kind of derailment may end up as being part of the problem, rather than providing a solution. A key pitfall is psychologization.

Psychologization – a pitfall in the use of psychology

One suggestion for what psychologization refer to is when moral, political and/or social categories are reduced or transformed into a question of psychological factors (Madsen & Brinkmann, Citation2010; Madsen, Citation2018). Maybe problems actually caused by social and structural problems (e.g., poverty or crime) are explained as simply having been triggered by intrapsychic processes and disorders (Camera, Citation2010), or maybe the wish of voters to vote conservative is solely explained on the grounds that they have an authoritarian personality.

Psychologization means that people’s psychological structures and processes are regarded as being the source, explanation and direction of action in relation to virtually anything in life. Furthermore, one can be held personally responsible for the way in which one as an individual succeed in dealing with the challenges of life, and one may end up holding oneself, and nothing or nobody else, responsible for one’s life situation. If one fail to handle life challenges including problems and situations that one cannot possible be responsible for and that one cannot by means of psychology, then the reason seen from a psychologization perspective is that one lacks the requisite personal qualities and skills (Crespo & Serrano, Citation2010).

As mentioned above, De Vos (Citation2010, Citation2014) refer to the double-sidedness of psychology. A psychologizing use of psychology can take place from an outward-directed as well as from an inward-directed perspective.

Psychologization means using psychology as an expanding concept intended to explain virtually every aspect of life. Social, cultural, and societal circumstances are understood and explained solely by means of psychological terms. Psychologization is either a way of disregarding social structures and dynamics that are not based on psychological factors, or a way to reinterpret these structures and dynamics into purely psychological terms. An example may be to consider racism solely as an expression of the group-shaped social identity ‘Them versus Us’ and as prejudices against others. Or, explaining racism as having arisen solely due to, for example, personality traits or clinical personality disorders.

From an outside-in perspective, psychologization is an equally misunderstood use of psychology. Here psychology is about external demands on the individual and the individual’s demands on themselves to be continuously reflective and self-optimizing. With the optics and imperatives of psychology, you must constantly develop your ability to deal with challenges, develop your personality, and develop your social relations and networks. This also means that interventions are directed inwards towards the individual rather than outwards towards social and cultural and societal structural changes and challenges of a financial, legal, ethical, or political nature.

Naturally, psychology is not synonymous with proneness to psychologization, but through the psychologizing use the constructive-critical and empowering potential of psychology is eliminated. Inspired by Antonovsky (Citation1979) and his pointing out that mental health rests on the ability to comprehend and handle life meaningfully, we understand psychologization as a tendency to/an attempt to comprehend, find meaning in, and manage complex biopsychosocial challenges by means of psychological concepts. Some key aspects of psychologization may be extracted from the above.

Psychologization means reducing the understanding and explanation of personal, social, cultural, and social structural factors solely into psychological categories

Psychologization may be nonpractical. It reduces interventions to pure introspections that are non-operationalizable or that cannot be operationalized into specific actions directed at/by life.

Psychologization may lead to individualization. Problems and challenges are seen as being solely the responsibility of the individual. Implicitly: The external structures are not the problem, but rather the individual behaving in a too unstructured way.

In this way, empowerment through the use of psychology is lost, and the desired curative function may instead be replaced by impaired well-being and mental health.

The negative effect of psychologization on well-being and mental health

In their quantitative and qualitative research study of young people in Denmark, Katznelson et al. (Citation2022) point out that psychologization together with elevated (and accelerating) pace and performance requirements constitute risk factors with regard to lack of well-being and impaired mental health. According to Katznelson and colleagues, 51% of the young people experience the pressure of constantly having to achieve a lot and even in an accelerating pace. 45% percent of the young people feel pressured by constantly having to perform more and more, better and better.

Here we focus sharply on the pointing out of the unfortunate consequences of psychologization on young people. In accordance with the above statement, the authors point out that, in principle, psychology can offer good and effective tools for handling well-being and health challenges in connection with pace in life and performance. However, as they also underline, the use of psychology can get out of hand and, as mentioned above, become part of the problem rather than part of the solution. We take a more detailed look at this research study because it provides a good indication of the challenges of young people, and because it draws a picture of the pitfalls of psychologization that empowering intervention programs must avoid.

As mentioned above, psychologically, young people’s reflections on life may be explicitly or implicitly oriented, that is, double-sided. Young people focus their attention outwards on external demands and expectations for pace, performance, and psychological life competence that are actually rooted in social, cultural, and societal structural conditions and discourses. And they focus their attention inwards on how they are able to live up to these requirements, or in fact, their focus is rather on how they are not able to live up to the demands. When goals and norms for performance are constantly ahead of you like a shadow you can never reach, performance becomes kind of indefinite. Overall, it remains unclear exactly what is to be achieved, and surely you will underachieve. Undoubtedly you will always have to do more. In this way, the demand for performance becomes limitless, and you will have increased focus on optimizing yourself in constant competition with yourself and others.

In their research study, Katznelson and colleagues underline two key aspects of the use of psychology, that is, as a resource and help, but also as something that can get out of hand and transform into psychologization, which may result in impaired well-being and mental health due to extremely intensified directedness towards oneself and extremely negative self-critical introspection.

According to Katznelson and colleagues, young people’s extremely intensified inwards directedness makes them try to set their own standards for pace and performance, and also for whether what they do, say, think and feel is good enough, which, as mentioned above, it never quite is. Again, you could say that the problem in itself is not that you turn your gaze inwards during psychological reflection occasionally. This is indeed all right. The problem lies in the fact that to some young people the situation gets out of hand when left alone to their own subjective and psychologically constructed standards in terms of living up to perceived external demands on pace, performance, and personality.

In continuation of what the authors point to, we may add that, as it is, the young people do not get/have a socially realistic corrective approach to their own (self-made) standards, but only a self-oriented psychologizing and individualizing corrective approach. In addition, the corrective approach is reduced to solely being about the internal psychological conditions concerning what you feel and want. It is not about actual structural and discursive conditions in the world around us. You could say that the standards young people have for themselves are pseudo-socially based on distorted computer-optimized Instagram-like images and Facebook stories about others and their lives. Images that basically stem from a misunderstanding saying that everyone else lives up to these standards. The unfortunate effect of social media is underpinned by Braghieri et al. (Citation2022) research study on the effect of the roll-out of Facebook at American universities in Facebook’s earliest days. The research study shows that this led to a worsening of mental health in a number of young people, especially as a result of unfavorable social comparison (“everyone else has a better life than me”).

The second aspect of psychologization which Katznelson and colleagues point to is that some young people using psychology and its concepts end up with a very negative self-critical view on own abilities and way of thinking. That is, an extreme introspection in the form of a self-condemning view as to not being good enough, authentic enough, not performing well enough, and as to having negative and ambivalent feelings. Once again, psychology is used in a psychologizing way, as the inward-directed gaze is set on oneself as never being good enough as a person. This misapplication of psychology makes you believe that the solution lies in the fact that you have to turn your gaze inward and take the psychologizing external demands for happiness and performance success with you in a constant monitoring of and pressure towards reaching the best version of yourself. But this remains a borderless project where enough is never enough, which may easily lead to self-condemnation.

Reflecting the two approaches of psychology, we let one of the participants in Katznelson and colleagues’ research study (Citation2022, p. 137) get to speak. Rasmus aged 24 says that he is tired of all the self-talk, self-monitoring, and self-criticism. Instead, he tries to take a practical approach to life. "[…] I try to find out what works here and now." The way in which the authors present Rasmus’ views on what has first and foremost helped him is that he tries to change the outer circumstances in his life rather than the inner ones that the psychologizing tools focus on. We might add: a nonpractical, psychologizing use of psychology does not seem to have helped Rasmus.

Summing up: We—and not least the young people—are in need of a psychology, which can be operationalized in practical tools which in an empowering way may help to cope with the challenges and problems young people contemporarily face in their own and common life. That is, a psychological theory and intervention that help direct the perspective inward as well as outward without it being transformed into reductionism, lack of operationalization, and individualization.

The LP-method as a practical and non-psychologizing method

The Life Psychological intervention method is a proposal for such a non-psychologizing and practical approach within the field of psychology, which can be operationalized in relation to actions directed at/by one’s own and common life. The theoretical basis of the LP method is unfolded, for example, in Bertelsen (Citation2013, Citation2021, Citation2022).

The LP method is developed in action research through active collaboration with a large number of practitioners (social educators, teachers, psychologists, street level workers, club employees, and youth mentors). Development, testing, and empirical studies have taken place within various Danish contexts: social psychiatry (Bertelsen, Citation2010), eighth grade pupils in public school (Skibsted & Bertelsen, Citation2016; Skibsted, Citation2019, Citation2020), high school (Bertelsen et al. Citation2020; Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021), and in mentoring radicalization-threatened adolescents (Bertelsen, Citation2018, Kruglanski & Bertelsen, Citation2020). The course material in the form of online resources and instructional videos is available free of charge.Footnote1

Below we will briefly outline the general workflow in the LP method in order to illustrate how to avoid the psychologization pitfall and ensure practical operationalization.

The aim of the LP method and the four-step workflow

Life psychology and the LP method build on the assumption that regardless of social, cultural, and life-historical background, and genetic-biological-psychological constitution, most people wish to have and live a good enough life (Bertelsen, Citation2013). Most people want to have, develop, create, and empower a good enough grip on own and common life. Having a good enough grip on life means that you are able to participate proactively and prospectively in the construction, maintenance and development of your life. Firstly, the grip on life must make personal sense. Secondly, it must be socially, culturally, and societally aligned (in a conforming and/or critical-constructive manner) with the norms and values of relevant communities. That is, the grip on life must not only have personal sense for the individual, but also a common social, cultural, and societal meaning.

On the one hand, the way you strive for a life that make sense always takes place on the basis of the social, cultural, and societal contexts familiar to you. Accordingly, one’s grip on life indeed does get its common meaning from the communities in which one partake. On the other hand, whether one like it or not, one’s directedness towards life will always in some way have an effect on the community. That is, one’s grip on life is some way or another meaningful and significant to the community.

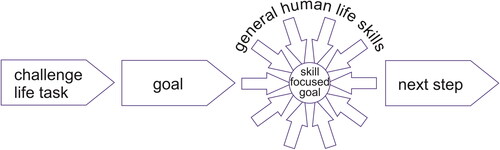

The workflow of the LP method developing and forming one’s personal senseful and common meaningful grip on life consists of four steps. One start by selecting and focusing on a challenge one want to work with. Then one set a goal, which can be a complete or partial solution to the challenge. The third step is to focus on life skills related to the aspects of the goal which are particularly salient, and which can be operationalized into actions, that is, a next step towards the goal. As such, this workflow results in practical actions directed at/by life, at any rate the part of life that is influenced by the handling of the chosen challenge and the set goal. The workflow in relation to the chosen challenge can be followed up with several next steps, i.e. a whole sequence of steps, or sub-goals, towards achieving the goal. One may choose additional challenges, so that one have several LP workflows that take place sequentially or concurrently with each other ().

Figure 2 The Life Psychological method, its basic concepts and its four-step workflow. As shown the method operates with ten general human life skills (the goal focusing arrows) which will be defined below.

Choosing a challenge

No life without constant challenges. Therefore, in this context and as pointed out by Antonovsky (Citation1979), having a good enough grip on own and common life lies in being able to comprehend and manage challenges in a senseful way, and we may add: in a commonly meaningful way. Both small challenges taking the bus, going shopping) and big challenges can be outward-directed (choosing education, changing jobs, establishing your own family) or inward-directed (noticing what a discomfort is about, learning to navigate on the conflict ladder, making peace with your personality traits or psychological challenges in a value-oriented manner). Challenges can be silent (routinely putting your key and mobile phone in your pocket before leaving your house) or pressing and attention-demanding (mending the bike, initiating a difficult conversation, noting whether you are on your way up the conflict ladder). The challenge that you choose to focus on in the LP workflow can relate to positive expectations and good emotions (learning something new, developing your kayak technique, developing your communication skills). Or the challenge may take the form of problems and difficult emotions (everyday hassles with ordinary structural things such as financial matters, or with more general and negative structural things, such as discrimination or stigmatization). This may be due to personal psychological difficulties and a lack of well-being. Or it may be due to bad physical health or disabilities that are genetically conditioned or caused by injury or lifestyle. Any such challenge can be inserted, one after another, in the first stage of the workflow. More challenges can be managed in successive or parallel workflows.

Choosing a goal

The goal to be set should be a positively formulated solution to a challenge (i.e., not negatively formulated as for example: "I want to get away from/stop…", but as a positively formulated: "I would like to…, begin to…"). Positive goals invite directedness for action (this is what I want to achieve), negative goals do not. A wide range of benefits comes with setting goals. If provides overview and helps prioritize what to concentrate on here and now. Goal setting provides a guideline for how to use one’s energy in a persistent way, and for what needs to be done. Moreover, setting goals is associated with increased well-being, and, not least, it helps change, develop and form a grip on own and common life (Cox & Klinger, Citation2004a; Eberly et al., Citation2013; Martre et al., Citation2013; Poulsen et al., Citation2015; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017).

Choosing life skills

Skills are our ability to do something, make something happen, act and thereby reach a goal. Life skills are our ability to achieve a life goal in a personally senseful way as well as a common meaningful way, that is, in alignment with the social, cultural, societal contexts and opportunities and conditions on which our existence is based. In short, attuned with our common life. Ultimately life skills are all about individually and jointly building, maintaining, and further developing a desirable own and common life (Bertelsen, Citation2013, Citation2022).

On the one hand, our life skills help shed light on what is key about a goal. Two persons may have the same goal, for example, to have a good time whilst attending an education, and for that matter they may have the same overall goal. But for one of them, the main aspect of that goal is to have good fellow students which demands life skills in relation to building social relations. For the other person, the main thing about the overall goal may be planning daily life in a way that ensures enough time to be with both family and friends, and to have a leisure life, as well as time enough to prepare well for the lessons. So, for this person, life skills in relation to planning are key in order to reach the goal.

On the other hand, life skills point toward practical action that helps managing the next step toward realizing the goal, and thus the part of life in focus in this part of the life-psychological workflow.

Thus, there is a clear connection. Each life challenge or life task corresponds with a specific life skill as to the ability to grasp and deal with the challenge or task in a personally senseful and commonly meaningful way. In other words, we are talking about units of life challenges or life tasks (LT) and life skills (LS), or in short: LT/LS units. Life tasks and life challenges varies almost infinitely depending on the social, cultural, and life-historical positions and discourses in which the individual is located. Similarly, the required LS handling varies almost endlessly, which is why it is impossible scientifically to list such infinite rows of LT/LS units, let alone for the individual to be able to acquire and remember these. So, in Life Psychology, a different path is chosen. In this context, the basic idea is to identify a delimited set of general human life tasks and corresponding general human life skills. These general sets can generate specific, concrete challenges and the corresponding specific and concrete life skills. In short, Life Psychology operates with a delimited set of generic LT/LS units. A theoretical and general psychological reason for life tasks and LT/LS units can be found in Bertelsen (Citation2013, Citation2021, Citation2022).

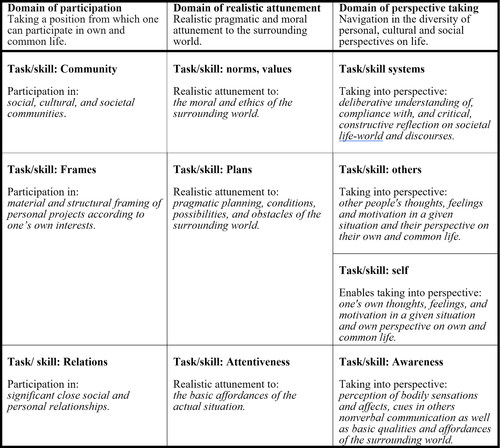

These universally human and generic LT/LS units are found in fundamental domains in life. Firstly, we have the life domain concerning to participate in life socially, culturally, and societally together with other people (participating in close relations, practical framing of life, and community). Secondly, we have the life domain concerning realistic attunement of our perception, approach, and actions in relation to the surrounding world (attentiveness, pragmatically planning, normative and value-oriented). Thirdly, we have the life domain concerning mentallization or perspective-taking (attention to inner and outer cues, understanding oneself, understanding others, understanding the systems that one is part of). The three domains have a total of 10 such general human and generic LT/LS units. A more precise definition of these is shown in , as well as in Bertelsen (Citation2013, Citation2021).

Figure 3 Definition of the basic generic and general human life task/life skill units in three domains.

As indicated, these LT/LS units are universally human. They are assumed to apply to any human form of life, that is, something which all people in their own way must be able to master. LT/LS units are also generic. This means that each of these units can be used to generate insight into and action in relation to a variety of specific challenges and similar specific skill-based activities.

For example, the general human life task of establishing and maintaining close relations (cf. Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995) varies from culture to culture in terms of the way in which families and friendships are formed, while being in need of and having close relationships is universal and general human. This also means that each and every general human life tasks underlie any everyday challenge. For example, the challenge to stand in a queue at the supermarket waiting for one’s turn expresses all domain tasks: One must be able to participate (work together in a joint way), one must be able to attune to reality (notice how the queue is moving forward) and one have to be able to mentallize (for example, bear with the impatient and quite provocative, harassed person behind you). It is clear that in different situations, various universal LT/LS units will be more or less important and more or less urgent, and they will be contributing in various more or less important ways to generating a good enough notion of and personally senseful as well as common meaningful handling of the situation in question.

The next step consists of operationalizing the chosen skills in the form of taking a next step towards realizing the goal. The next step must be as specific as possible (in relation to who, what, where, and when), for example: “On Wednesday at 1 pm, I will arrange for a talk with A in her office.” The hazier and less action-filled the next step is, the greater the risk will be that you do not know what to do and therefore get nothing done (Gollwitzer, Citation1993; Oettingen et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, it is important that you have a plan for what you want to do if unforeseen circumstances or obstacles arise (Cox & Klinger, Citation2004b), because this increases the probability that the next step will be taken. It also makes it possible to change the next step accordingly (make a plan B), for example: “If A is not at the office, I call her or write an email about a new appointment.”

The two levels of the LP method

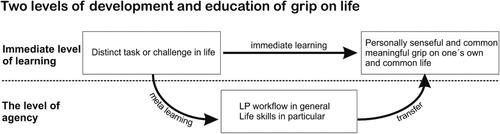

Basically, the LP method operates at two levels. At an immediately practical level, the LP method is about dealing with specific challenges and finding useful goals and solutions in order to make practical changes to a small or larger part of life. On a deeper level, through the practical acquisition of the methodology (meta-learning), a more general learning, development and education is acquired. Through learning and practical use of the method, a common skillset is acquired in the form of the ability to get a grip on life and general life tasks. You acquire a perception of yourself as a participant with specific practically useful tools, not only for learning to solve the specifically chosen challenge (immediate learning), but also for being able to meet other future challenges by means of the LP workflow skillset (transfer). In this way, a meta-cognitive mindset is acquired, that is, a practical understanding of oneself as a participant who is actually able to handle and grasp the small and major life challenges and the innate common life tasks in a personally meaningful and commonly important way. In other words, the acquisition and continued use of the LP workflow contribute to proactive and prospective empowerment. And indeed, the practical use of one’s skills contributes to continued development and formation of the common human life skills by which one generally masters a good enough grip on own and a common life ().

Figure 4 Two-level LP workflow. By focusing on handling specific tasks in order to reach a goal, meta-learning develops. That is, by means of the LP workflow and general human life skills, common, generic, and metacognitive learning takes place, which may transform into a general foundation for one’s personal and common life in general.

LP method to avoid psychologization pitfalls

Based on insight into own and common life world and challenges that feel prospective and meaningful, the individual user, for example a high school student, decides (a) which problem to work with, (b) which goal appears to be a good enough solution, (c) which skills are in the foreground now in relation to the most important aspects of the goal, and (d) thereby how to activate/operationalize the chosen life skills in a personally senseful and commonly meaningful manner.

In this sense, the LP method complies with the framework outlined above for a method that is outward directed toward sociocultural opportunities and conditions. The method is also inward directed, however, notably firstly toward empowerment at each of the four steps in the workflow, including, not least, empowerment in the use of the wheel of skills. Secondly, inwardly directed toward development of agency in the form of a metacognitive mindset and skillset. Thirdly, inwardly directed in the sense that a personal and psychological challenge or problem can in itself be turned into a challenge that can be inserted in the workflow in a practicable and action-oriented way (“what is the next step in relation to this problem?”).

The question is how the LP method avoids the pitfalls of psychologization. Let us take a closer look at the LP method in the light of the three aspects of the psychology identified above: reductionism, non-practicality, and individualization.

Regarding reductionism, the LP method does not prescribe either implicitly or explicitly that challenges and solutions should be understood as simplified or reduced to purely psychological categories. On the contrary, the LP method and each of its steps can usefully be integrated with other methods, inter alia sociological (e.g., discourse analysis), political (e.g., interest-oriented activism), and legal (e.g., fairness-orientated mediation) methods.

Challenges can be understood psychologically, but also from an existential, cultural, and social perspective, and from a nature-oriented perspective (biological health, climatic threats, etc.). Similarly, goal-setting may be formulated in psychological as well as non-psychological terms (e.g., regarding private finances or psychology in relation to personal self-reflective work with mental health and development and education). The choice of skills and operationalization of these in the next step may similarly focus on specific life domains and domain-specific practices (such as political initiatives in your surroundings, whether it is in the public school eighth grade, in high school, in your local community, or in the society you are part of). Thus, the next step can be a purely psychological operationalization of the universally human life skills, such as an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)-oriented way of making peace with your own psychological basic constitutions or personality traits, while at the same time striving to act in a value-oriented personally senseful and commonly meaningful way. The next step may also form part of a physiological-medical attempt to alter the medically problematic aspects of one’s lifestyle, such as to exercise more or change one’s eating habits. Or the next step may be some sort of political activism toward undesirable social, cultural, organizational, or societal structures.

About nonpractical lack of operation ability

As stated and emphasized above, the actual solution-oriented workflow in the LP method in itself is a systematized incremental operationalization that goes from challenges to goals to choice of skills and realization in the form of life-directed actions and taking a next step toward realizing of a particular goal, as well as proactive and prospective change of life in general.

This consistent solution-oriented and operationalization-oriented workflow avoids the psychologizing and ruminating pitfall, that is, to continuously revolve around challenges and problems and analyze these in more and more advanced psychological details and with the involvement of more and more factors. It certainly gives increased insight, and one get better at talking openly about difficult problems. However, without getting to change one’s grip on life, neither psychologically, existentially, socially, culturally, nor societally. The LP workflow is based on the fact that the challenge should be understood just enough to set a good enough sub-goal to make it possible to operationalize one’s life skills into making actual changes in order to get a good enough grip on own and common life.

About individualization

The LP workflow provides the opportunity, but like all other methods, never a guarantee to avoid the pitfall of individualism. This opportunity is embedded in two key aspects of the method. Firstly, the LP workflow is based on general human and generic LT/LS units. The method is therefore not specific and solely directed at/by specific types of psychologically identified challenges (such as self-confidence, personality disorders, clinical or psychiatric diagnoses etc.). On the contrary the LP method is directed at/by the general human life tasks, which must be handled in order to establish, maintain, and develop a good enough life for oneself and each other. Obviously, it is possible to handle psychologically identified challenges as challenges in the LP workflow. In this case, these are handled in a universally human and non-stigmatizing way (cf. Bertelsen, Citation2013) as everyone—regardless of background, position, and situation—can somehow actually make use of life skills, for example, by dealing with anxiety and/or anxiety-related life challenges using participatory, reality-aligning, and metallizing life skills.

Secondly, each step in the workflow is designed to care for what makes sense as to one’s individual efforts to deal with the ways in which the general human life skills are presented, in the form of one’s specific lifeworld challenges. But perhaps just silently in the sense of embedded meaning in the skills as being universally human—it is also a matter of care for humaneness, in the form of an orientation toward the common meaning of such challenges. This is partly due to a common fundamental understanding of the challenge as an expression of basic life tasks we all need to be able to handle. Partly because the way we handle own challenges always also has an effect on, i.e., has a common meaning for the community, may it be microscopic or sometimes considerable.

The LP method – possibly a critical method

Naturally, a critical confrontation with psychologization does not imply a rejection of psychology as such. A consistent rejection of psychology would correspond to, for example, a sociologizing or politicizing reduction. Psychology is - not least, as here, in the form of the metacognitive structure and learning design behind the method - together with other arts and social sciences indeed pertinent to understanding, explaining, and empowering the individual’s participation in social, cultural, and societal life for oneself and together with others who proactively and prospectively want to create, maintain, and develop a good enough own and common life.

Therefore, focusing on psychology and psychological empowerment with regard to getting a grip on own and common life does not mean that we, as a society, can allow ourselves to lose grip on the structural challenges that contribute to increased vulnerability and worsened mental health. Focus on psychology is not synonymous with individualizing the problems.

However, regardless of how society points out, manages and unfolds political solutions, we are all, including young people, exposed to the challenges that such solutions (or lack of the same) provide as conditions and opportunities for a good enough life. Challenges that we as part of a community must find ways to deal with. Challenges that we may take a critical-constructive approach to, maybe as part of our everyday efforts to achieve a good enough grip on life, or as explicit activism.

The particular challenges and the new kind of vulnerability that Katznelson et al. (Citation2022) point to - relating to pace, performance and psychologizing self-relation, feeling aversion and self-critical introspection - can be handled using the LP method. They may be comprehended as challenges that be set up in the first step of the LP workflow. Next, sub-goals can be inserted to address these challenges in a solution-oriented manner. The universal human life skills can be used to identify the next step that the person should take, aimed at less pacing, less performance-orientation, and less psychologizing and individualizing grip on life in the future.

We have taken a look at the LP method as psychological suggestion for a non-psychologizing and non-individualizing practically operationalizable action-based method. Therefore, we need to take a closer look at the initial questions about (1) whether LP interventions actually help young people to build up a grasp of the actual LP workflow, and thus developing an LP-oriented meta-mindset and skillset related to oneself in own and common life in an empowering way—and (2) whether such acquisition of the method actually has an effect on young people’s well-being and mental health based on the parameters: stress, well-being and experiencing a sense cohesion in life.

Studying the effect of LP intervention

Previous research studies - High school project 1 and 2

Two previous studies have shown good results in relation to the implementation and effect of the LP method. As they form the basis of the present study, they are briefly presented here.

High school project one (HSP1) - bertelsen et al., Citation2020

Implementation of such methods is often costly for institutions and educational venues. The first high school project focused on investigating whether the LP method could be implemented in a self-administered manner. A total of 33 students (average age 17.5 years) from two high schools in Denmark received a three-hour introductory course and full access to the open access resources. During the following ten weeks, the students worked with challenges of own choice. The students, as well as a control group, completed a pre-and post-test.

The result of this study shows that week by week the young high school students worked systematically with the method as expected, that is, with a high degree of fidelity (Cook & Campbell, Citation1979; Proctor et al., Citation2011). The study drew a distinction between technical fidelity and intrinsic fidelity. Technical fidelity defines users—here the young people—understanding the concepts, tools, and workflow, and in practice using the method as intended. In other words, the method is acquired as a skillset. Intrinsic fidelity defines users experiencing the method as personally senseful, and a method that he or she would like to engage in and use as well as possible, i.e., the method is acquired as a mindset. Furthermore, the result of the research study shows empowerment of the young people’s ability to reflect on the use of the LP method and using it for general, generic, and prospective goal-setting regarding their personal life world in order to get a good enough grip on own and common life. Thus, the research study shows that LP can actually be implemented successfully, that is, as a meta-cognitive grip on life with a high degree of technical and intrinsic fidelity in a self-administered (and, in so far, non-cost-intensive) way.

High school project two (HSP2) - Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021

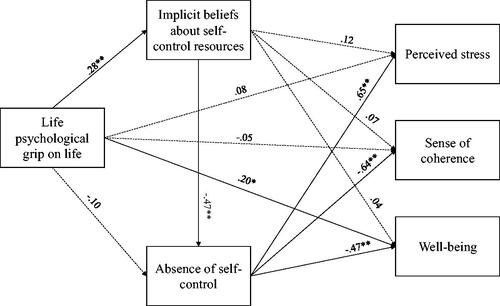

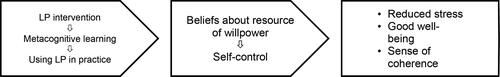

The purpose of this research study is to examine whether an LP mindset (that is, a basic understanding of the LP method including its concepts and application) has an effect on general well-being and stress via self-control.

Francis and Job (Citation2018) have shown that self-control is essential for one’s ability to reach goals in several life domains (education, occupation, health, social relations, and well-being in general). Conversely, it can be said that low self-control has a negative effect on a good enough life. Other research studies (Job et al., Citation2015; Bernecker et al., Citation2017; Napolitano & Job, Citation2018) show that a positive implicit belief of and expectation of self-control when it comes to energy-demanding challenges and tasks has proven a key factor behind well-being. Conversely, low or negative expectations of own self-control are linked to the fact that the actual use of self-control is impaired, which reduces well-being.

The question is then what precedes and helps create positive or negative belief of own self-control—and thereby also of actually carried out self-control, here understood and measured in the form of robustness, resilience, and agency. In continuation of the above discussion, one could say that a purely abstract requirement to ‘make positive’ one’s belief about own self-control resources and an abstract requirement to demonstrate better self-control in order to improve one’s grip on life, easily becomes a nonpractical requirement that does not actually answer the question of how this is done, and thus, against the good intentions, it can actually create a psychologizing kind of despair ("Okay, how do I do that? I have no idea! Even this I can’t figure out!"). In the HSP2 research study, we studied if acquisition of the LP method could be a decisive preceding factor as to being a concrete and plausible way of getting hold of the challenges and tasks in life.

A total of 276 high school students (average age 17.5 years) from eight high schools in Denmark participated in the HSP2 research study. The participants responded to an online questionnaire about their grip on life (via questions based on the LP method and its concepts, specific tools, and workflow) as to beliefs about self-control resources and self-control, as well as experienced stress and general well-being. The results of the research study show that a good enough grip on life measured by means of the elements of the LP method (choice of challenges, setting goals, using skills to operationalize steps towards achieving one’s goal) may be antecedent to a positive belief about and use of own self-control resources with a view to handling life challenges tasks with resulting good well-being and a low degree of stress ("I know what it means to perform self-control in practice and to have a grip on the challenges and tasks in life. I can picture it by virtue of the LP workflow").

Based on these results, it seems reasonable to assume that an actual LP intervention aimed at systematically and purposefully teaching young people how to use the LP method can in fact create a specific and practicable image - rather than an abstract, nonpractical, psychologization-based demand—of how it must be done. We investigated this further in High School Project number three (HSP 3).

Present study – high school project 3: the effect of LP intervention on young people’s grip on life

The purpose of this project was to investigate whether a systematic and thorough intervention (a teacher-administered instruction of high school students in the use of the LP method, and the students’ use of the method over a longer period of time) could help creating a non-psychologizing and practical approach to life, measured in perceived stress, general well-being, and sense cohesion in life.

Design

Ten high school teachers from three Danish high schools participated in a three-day course held at the Department of Psychology and Behavioural Sciences, Aarhus University. The aim of the course was for the teachers to be able to instruct high school students on the use of the method with a high degree of fidelity. Immediately after the end of the course, all the teachers composed small groups of high school students who wished to participate in a course over 10 wk: One weekly group session at school together with the teacher, as well as individual work on the method between sessions.

During the first two sessions of the course, the groups were introduced to the whole process and instructed in the use of the LP method, its concepts and workflow, and in the use of the key online tool, the LP app (cf. footnote 1). From the third to the tenth time, the students work in sessions at school—by following the app’s instructions step by step—with a challenge of own choice from their own life world (school, family/friends, leisure). They set goals, chose skills and operationalized them in the first step, and worked with this for a week until the next session. In the subsequent session, the students evaluated their homework and how they had been doing with taking the next step toward the goal. This reflection helped the students consider whether to continue with the same challenge, goal, choice of skills and the next step in the following week. Or, whether changes should be made to one or more of the steps, perhaps because the goal had been reached or the next step had been taken and thus ready for a new next step, or perhaps because one or more of the steps were too ambitious or not fully aligned with one’s engagement or external conditions and had therefore not been worked on. Based on own reflections, the students continued working with the LP app, ready to figure out the next step (the same or a new next step) towards the goal (the same, a slightly changed or new one) and thus ready to work with the next step in the following week.

Before and after this intervention project, the students completed an online test, and so did a control group who did not take part in the process and who did not receive any attention apart from taking the test. We measured the effect of the teachers’ LP intervention on the students as well as the effect of the daily use of the LP method in terms of whether the students did actually acquire the method. Also, in the form of a replication study (cf. Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021), the indirect correlation between the LP skillset and stress, general well-being and sense of coherence in life was studied through a path model focused on self-control.

Participants

Power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2009) for a t-test to detect a difference between two dependent means with a medium-sized effect (d = .50) and 85% power (Cohen, Citation1992). The expected effect was based on previous research utilizing a similar intervention (Bertelsen et al., Citation2020). Our power analysis produced a minimum required sample size of N = 38 for each group to detect two tailed significant effects (alpha level of .05).

Participants were 104 high school students (66 female, 37 male, Mage = 17.81, SDage = 0.79). These students were divided into an intervention group (n = 42, 78.6% female) and a control group (n = 62, 54.1% female).

Measurement

Participants answered questions concerning background information such as their age, gender, and school affiliation. Besides this background information, the following measures were used.

Life psychological grip on life

The acquisition of the LP method as a non-psychologizational and practical grip on life was assessed with the TPM-16, a newly developed assessment scale. An item example is “when I set a goal, I think about which skills it would be fine to develop (at bit or a lot) to reach my goal”. The answers were stated on a 7-point Likert-scale (1 = for the time being not typical of me, 7 = for the time being very typical of me, = .91). Because TPM-16 is a new scale, CFA was conducted using the whole sample at T1. Results yielded acceptable fit to the data, χ2(99) = 149.42, p < .001; CFI = .91; SRMR = .08; RMSEA = .07, 90% CI = .05 to .09, with factor loadings ranging between .36 and .85. While factor loadings below .40 can be considered questionable, we adhere to general guidelines that accept loadings above .32 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007).

Implicit theories about willpower were assessed with a Danish translation of the Implicit Theories About Willpower for Strenuous Mental Activities Scale, ITW-M (Napolitano & Job, Citation2018) comprising six items, for example: “Strenuous mental activity exhausts your resources, which you need to refuel afterwards (e.g., through breaks, doing nothing, watching television, eating …)” on a 7-point scale (1= disagree, 7 = agree, = .86).

Absence of Self-Control was measured through the Self-Control Scale, SCS (Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021), comprising nine negatively phrased items inspired by existing inventories (i.e., The Brief Self-control Scale by Tangney et al., Citation2008; self-regulation inventory by Grossarth-Maticek & Eysenck, Citation1995). The first three items concern robustness, for example, in relation to resisting temptation: “Although I have set a meaningful and important goal, I may easily be attracted to funny or exciting things which will divert me from this goal.” The next three items reflect resilience, for example, regarding persistence: “When goal progress becomes difficult and strenuous, I am not persistent in my effort to reach my goal.” The last three items are about agency, for example, “I am unaware of which direction my life should take and which goal would be good for me to have.” The answers were stated on a 7-point Likert-scale (1 = for the time being not typical of me, 7 = for the time being very typical of me, α = .81).

Perceived stress was assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale, (PSS; Cohen et al., Citation1983), containing ten items that ask about the participant’s feelings and thoughts during the last month, e.g. “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?”, on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often, = .89).

Sense of coherence was assessed using the Sense of Coherence Scale (SCS; Antonovsky, Citation1993) assessing how respondents view life and identifies how they use their resistance resources to maintain and develop their health. The short version of the scale includes 13 items covering the three components of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. Sample items read: “Does it happen that you experience feelings that you would rather not have to endure?”. Replies were given on a 7-point Likert-scale based on different scale notions depending on items, for example 1 = never happened, 7 = happened many times, or 1 = missed goal and meaning, or 7 = both goal and meaning, = .84.

Well-being was measured through the Flourishing Scale (FS; Diener et al., Citation2009). The scale tap into self-perceived success in important areas such as relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism through eight items, e.g. “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life”, on a 7-point Likert-scale (1 = not at all, 7 = highly, = .85).

Analytic overview

All analyses were conducted in SPSS or Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998-2011) employing Maximum Likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. The analytic process consisted of two steps. First, we examined whether the life skills intervention had an effect by comparing replies before (T1) and after (T2) the intervention across both the intervention group and the control group. Second, we sought to replicate a previous study (Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021) suggesting life skills to be antecedents of beliefs about self-control and actual lack of self-control, and in turn perceived stress and well-being. Additionally, we also tested changes in the sense of coherence. This replication was examined through path analysis using all the replies from T1 (i.e., both intervention and control group) in order to reach sufficient statistical power (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987).

Results

Testing the effects of the life skills intervention

First, we examined mean differences across T1 and T2 for the intervention group employing paired samples t-test. Conducting multiple tests increases the risk of Type 1 error, and consequently, we employed Bonferroni corrections to control the family-wise error rate by adjusting the cutoff alpha level. Accordingly, statistical significance can be presumed at p < .008. The results reviled that there were a significant effect of the intervention reflected in an increase in life skills, t(40) = −4.27, p > .001, d = −0.67, sense of coherence, t(40) = −3.76, p > .001, d = −0.59, and well-being, t(40) = −4.57, p > .001, d = −0.71. Furthermore, there were a decrease in absence of self-control, t(40) = 3.67, p > .001, d = .57, and perceived stress, t(41) = 4.10, p > .001, d = .63. There were no significant effect on implicit beliefs about self-control resources, t(40) = −0.44, p > .331, d = −0.07. Overall, a salutary effect of the intervention was observed in five out of six measures used for evaluation.

Second, to relate these results with students who did not receive the life skills intervention (i.e., control group), we compared means across T1 and T2. The results indicated no significant difference in regard to either life skills, t(58) = −0.90, p = .373, d = −0.12, implicit beliefs about self-control resources, t(58) = 0.76, p = .449, d = −0.07, absence of self-control, t(58) = 0.79, p = .432, d = .10, perceived stress, t(59) = 0.23, p = .982, d = .00, sense of coherence, t(59) = −0.68, p = .501, d = −0.09, or well-being, t(57) = 1.05, p = .301, d = .10. Accordingly, the control group did not exhibit any positive effects observed in the intervention group, indicating the effectiveness of the intervention.

Table 1. Correlation matrix and means for the intervention group.

Table 2. Correlation matrix and means for the control group.

Path model analysis

As reflected in and , the bivariate correlations indicate that life skills were significantly associated with less perceived stress and greater sense of coherence and well-being after the intervention. This pattern was not found in the control group.

The hypothesized indirect effects model (Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021) was estimated through path analysis utilizing both groups’ replies at T1. In this fully saturated mediation model (see ), life skills was positively associated with implicit beliefs about self-control resources, β = .28, p = .002, 95% CI = .11 to .45, and well-being, β = .20, p = .028, 95% CI = .02 to .38, while unassociated with absence of self-control, β = −0.10, p = .251, 95% CI = −0.26 to .07, perceived stress, β = .08, p = .407, 95% CI = −0.11 to .26, and sense of coherence, β = −0.05, p = .655, 95% CI = −0.27 to .17.

Implicit beliefs about self-control resources were positively linked with absence of self-control, β = −0.47, p > .001, 95% CI = −0.63 to −0.32, but not significantly related to the three dependent variables: perceived stress, β = .12, p = .127, 95% CI = −0.27 to .03, sense of coherence, β = .07, p = .360, 95% CI = −0.08 to .23, and well-being, β = .04, p = .700, 95% CI = −0.17 to .25.

Finally, absence of self-control was significantly linked with perceived stress, β = .65, p > .001, 95% CI = .51 to .79, sense of coherence, β = −0.64, p > .001, 95% CI = −0.78 to −0.49, and well-being, β = −0.47, p > .001, 95% CI = −0.625 to −0.32. Overall, the path model results suggest that grip on life is associated with well-being through beliefs about self-control resources and the absence of self-control.

Discussion of the results

The results support the assumption of the life skills intervention being effective reflected in the increase in the acquisition of the LP method as a non-psychologization and practical grip on life, associated with an increase in sense of coherence, and well-being together with a decrease in absence of self-control and perceived stress. Meanwhile, the control group did not indicate any changes in regard to these variables. Furthermore, the path model largely replicated the previous model (Bertelsen & Ozer, Citation2021) suggesting that implicit assumptions about will-power and self-control mediate the association between life skills and psychological well-being (perceived stress, sense of coherence, and well-being).

While this study investigates the effect of life skills intervention on the well-being of youth, it is essential to address potential confounding variables that may influence the results. Factors such as socioeconomic status, family support, mental health conditions, and various external stressors could play a role in regard to both the intervention and well-being levels. Although these confounders could introduce random effects in both groups, further investigations are needed for a better understanding of the complexity of these intervention effects.

Regarding the life skills intervention, our results clearly indicate a positive outcome of this cost-neutral, self-administered method. These results are in accordance with other research indicating the psychologically adaptive effects of life skills interventions. That is, interventions facilitating life skills development has proven to mitigate stress and improve self-esteem (Sobhi-Gharamaleki & Rajabi, Citation2010; Yankey & Biswas, Citation2012). Accordingly, the results suggest that life skills interventions could be one way of addressing the mental health challenges among the youth.

Limitations

Our results should be considered in the light of several important limitations. First, our path model is based on correlational data, and we cannot conclude any causality based on this approach. Nevertheless, our test of the life skills intervention clearly supports the assumption linking increased life skills with positive well-being consequences. Second, participation was restricted to high-school students, limiting the generalizability as students might be more responsive to such interventions. Although more research is needed, it is expected that these interventions could be effective for youth in general. Third, participants were not blinded, potentially introducing bias as the expectations of the intervention could influence the perception of an effect. Moreover, the students were not divided into the control or intervention group completely at random. However, baseline comparisons indicate no significant differences between the mean values of the control (M = 3.97, SD = 1.27) and intervention (M = 3.82, SD = 0.85) groups regarding Life Psychological grip on life, t(101) = −0.66, p = .513, d = −0.13. Future research could use a more rigorous experimental design. Fourth, the study employed self-report measures, which may be susceptible to response bias, social desirability, and subjective interpretation. Consequently, future research could be enhanced by complementing these measures with more objective methods. Fifth, although the study was based on a generic conception of life skills, cross-cultural research is needed to determine how well this method can be utilized in other sociocultural contexts. Overall, these limitations underscore the need for additional investigation to strengthen the validity of these preliminary findings.

Conclusion

We have argued in favor of using the LP method as a non-psychologizing and practical, operationalizable use of psychology based on the life psychological theory. This theory and method was developed with regard to getting a good enough grip on own and common life. Previous studies show that the LP method can be acquired with a high degree of technical and intrinsic fidelity by young high school students via systematic intervention and metacognitive learning, that is, understanding oneself as an individual having agency who knows and is capable of using the method in practice when facing challenges in own life world. Moreover, the present study shows that LP intervention, through beliefs about self-control resources and the exercising of autonomy, has a positive effect on the mental health of young high school students, measured by perceived stress, general well-being, and sense of coherence in life.

As illustrates it is neither psychologizing nor unspecific and hardly operationalizable demands for mobilization of willpower and self-control that do take effect on mental health. Willpower and self-control understood as robustness, resilience, and agency become empowered by specific, distinct, and operationalizable ideas about how one can actually handle urgent and self-chosen challenges via goal setting, choice of adequate life skills, and their operationalization as next step towards the goal and hence getting a good enough grip on the part of life in question.

Figure 6 LP intervention takes effect through beliefs about resources of willpower and self-control on mental health.

This indicates that it is possible to provide young people with non-psychologizing and practical operationalizable life-directed tools for the use of achieving a good enough grip on own and common life, hence counteracting vulnerability and impairment of mental health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The LP method – also called the LGT method in Bertelsen et al. (Citation2020) and Bertelsen & Ozer (Citation2021) – is based on two leading principles: firstly, non-profit and open access, secondly respecting that most institutions have limited resources for courses and implementation with regard to time and finances. To provide easy access the following material can be found free of charge: Online instruction material, a series of short videos, an online LP app guiding interested users through the method (cf. www.psy.au.dk/life), and a handbook (Bertelsen, Citation2022) that can be used for either self-tuition or short courses. The method is scalable for different age groups and settings. The implementation is further scalable for courses lasting a few hours or, for example, 10-week courses (cf. the below study).

References

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. Jossey-Bass.

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 36(6), 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for Interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

- Bernecker, K., Herrmann, M., Brandstätter, V., & Job, V. (2017). Implicit theories about willpower predict subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 85(2), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12225

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Bertelsen, P. (2005). Free will, consciousness and self. Anthropological perspectives on general psychology. Berthahn Books.

- Bertelsen, P. (2010). Aktør i eget liv. Om at hjælpe mennesker på kanten af tilværelsen. Frydenlund.

- Bertelsen, P. (2013). Tilværelsespsykologi. Et godt nok greb om tilværelsen. Frydenlund.

- Bertelsen, P. (2018). Mentoring in anti-radicalisation. LGT: A systematic assessment, intervention and supervision tool in mentoring. In G. Overland, A. Andersen, K. E. Førde, K. Grødum and J. Salomonsen (Eds.), Violent extremism in the 21st century. International perspectives (pp. 312–352). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bertelsen, P. (2021). A taxonomical model of general human and generic life skills. Theory & Psychology, 31(1), 106–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354320953216

- Bertelsen, P. (2022). Et godt nok greb om tilværelsen. En håndbog i tilværelsespsykologien. Frydenlund.

- Bertelsen, P., & Ozer, S. (2021). Grip on Life as a possible antecedent for self-control beliefs interacts with well-being and perceived stress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12676

- Bertelsen, P., Ozer, S., Faber, P., Jacobsen, A. S., & Lund Laursen, T. (2020). High school students’ grip on life and education: High-school students’ self-administered work with a life mastering method. Nordic Psychology, 72(4), 265–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2019.1690557

- Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social media and mental health. American Economic Review, 112(11), 3660–3693. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20211218

- Camera, C. G. (2010). Je Te mathème!: Badiou‘s de-psychologisationof love. In J. De Vos, & A. Gordo (Eds.), Psychology under scrutiny (Vol. 8, pp. 153–178).

- CDC (2022). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. J. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Houghton Mifflin.

- Cox, M. W., & Klinger, E. (2004a). A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change. In W.M. Cox, & E. Klinger (Eds.), Motivational counseling. Concepts, approaches, and assessments (pp. 121–140). John Wiley & Sons.

- Cox, M. W., & Klinger, E. (2004b). Motivational counseling: Taking stock and looking ahead. In W.M. Cox, & E. Klinger (Eds.), Motivational counseling. Concepts, approaches, and assessments (pp. 479–488). John Wiley & Sons.

- Crespo, E., & Serrano, A. (2010). The psychologisationof work: The deregulation of work and the government of will. In J. De Vos, & A. Gordo (Eds.), Psychology under scrutiny (Anual Review of Critical Psychology, Vol. 8, pp. 43–62).

- De Vos, J. (2010). Beyond psychologisation. The non-psychology of the Flemish novelist Louis Paul Boon. In J. De Vos, & A. Gordo, (Eds.), Psychology under scrutiny (Anual Review of Critical Psychology, Vol. 8, pp. 201–216).

- De Vos, J. (2014). Psychologization. In T. Teo (Eds.), Encyclopedia of critical psychology. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_247

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266.

- Eberly, M. B., Liu, D., Mitchell, T. R., & Lee, T. W. (2013). Attributions and emotions as mediators and/or moderators in the goal-striving process. In E. A. Locke, & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goal setting and task performance (pp. 35–50). New York: Routledge.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Francis, Z., & Job, V. (2018). Lay theories of willpower. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass, 12, 1–13.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum Publishing Company.

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 141–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000059

- Grossarth-Maticek, R., & Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Self-regulation and mortality from cancer coronary heart disease and other causes: A Prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(6), 781–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(95)00123-9

- Job, V., Walton, G. M., Bernecker, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Implicit theories about willpower predict self-regulation and grades in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(4), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000014

- Katznelson, N., Pless, M., & Görlich, A. (2022). Mistrivsel i lyset af tempo, præstation og psykologisering. Om ny udsathed i ungdomslivet. Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

- Kruglanski, A., & Bertelsen, P. (2020). Life Psychology and Significance Quest. A Complementary Approach to Violent Extremism and Counter Radicalization. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 15(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2020.1725098

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2013). Potential pitfalls in goal setting and how to avoid them. In E. A. Locke, & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

- Madsen, O. J., & Brinkmann, S. (2010). The disappearance of psychologization?. In J. De Vos, & A. Gordo (Eds.), Psychology under scrutiny (Anual Review of Critical Psychology, Vol. 8, pp. 179–200).

- Madsen, O. J. (2018). The psychologization of society. On the unfolding of the therapeutic in Norway. Taylor and Francis.

- Martre, P. J., Dahl, K., Jensen, R., & Nordahl, H. M. (2013). Working with goals in therapy. In E. A. Locke, & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goal setting and task performance (pp. 474–494). Routledge.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2011). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.) Muthén & Muthén.

- Napolitano, C. M., & Job, V. (2018). Assessing the implicit theory of willpower for strenuous mental activities scale: Multigroup, across gender, and cross-cultural measurement invariance and convergent and divergent validity. Psychological Assessment, 30(8), 1049–1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000557

- NCM. Nordic Counsil of Ministers (2022). Nordic Co-operation on young peoples health. A cross-Nordic mapping of associative factors to the increase of mental distress among youth.

- Oettingen, G., Wittchen, M., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2013). Regulation goal pursuit through mental constraints with implementation intentions. In E. A. Locke, & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goalsetting and task performance. Routledge.

- Poulsen, A. A., Ziviani, J., & Cuskelly, M. (2015). The science of goal setting. In A. Poulsen, J. Ziviani, & M. Cuskelly (Eds.), Goal setting and motivation in therapy (pp. 28–39). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publishing.

- Skibsted, E., & Bertelsen, P. (2016). Fra relationskompetencer til tilværelseskompetence. Et pilotprojekt. In E. Skibsted, & N. Matthiesen (Eds.), Relationskompetencer i læreruddannelsen og skole (pp. 157–178). Dafolo.

- Skibsted, E. (2019). Elevens alsidige udvikling i skolen – en tilværelsespsykologisk intervention. Pædagogisk Psykologisk Tidsskrift, 5/(6), 48–70.

- Skibsted, E. (2020a). A lifeworld approach to the pupils’ general development in school. Nordic Psychology, 72(4), 292–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2019.1698315

- Sobhi-Gharamaleki, N., & Rajabi, S. (2010). Efficacy of life skills training on increase of mental health and self esteem of the students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1818–1822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.370

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

- Tangney, J., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2008). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

- UNICEF & the European Union. (2022). The state of the world’s children 2021. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/eu/reports/state-worlds-children-2021

- WHO. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being