Introduction

The background and resources presented here support teaching about two Tent/Freedom Cities—in Fayette County, Tennessee, and in Lowndes County, Alabama—that were built as a form of civil rights resistance and for housing BlackFootnote1 sharecroppers and tenant farmers evicted by oppressive white landlords for marching, attending mass mobilization meetings, and trying to register to vote. We conceptualize these Tent/Freedom Cities as forms of Black place-making and anti-racist mobility work and suggest that teaching about these insurgent encampments represents a neglected chapter within the “canon” of what has tended to be commemorated and taught about the Civil Rights Movement. We identify photographs, first-person accounts, and other primary source documentation for exploring and teaching Tent/Freedom City geographies. In doing so, there is an opportunity to focus on the under-discussed intersection of civil rights struggle and the production of home—complete with moments of lived resistance, resourcefulness, community-building, self-defense, and joy.

Purpose

There has long existed a need for incorporating a wider and deeper understanding of the Civil Rights Movement (which we also refer to in this paper as the Movement) into geography education. Important to teaching about and for racial justice is the generation of geography curriculum and teaching content that identifies and explores the specific material landscapes and places undergirding the African American Freedom Struggle. We suggest that “Tent City geographies” or “Freedom City geographies” have the potential to help teach the Movement from an explicitly place-making perspective and explore the historical geography of these encampments, which arose out of the Movement’s struggles over Black communities exercising the right to vote and the right to move (or stay put) on their own terms. The purpose of our paper is to offer background and resources for teaching about two Tent/Freedom Cities—one in Fayette County, Tennessee (located approximately 45 miles east of Memphis), and one in Lowndes County, Alabama (located approximately 30 miles southwest of Montgomery). We use these case studies to advance instruction in practical ways but also in terms of broadening ways of knowing, remembering, and learning through the Civil Rights Movement. The Movement may appear to be a well-understood chapter in the nation’s past, but its story has been impacted by simplification, selectivity, and sanitization, both in the classroom and within popular media and culture (Southern Poverty Law Center Citation2011; Swalwell, Pellegrino, and View Citation2015; Rodríguez and Vickery Citation2020).

Our central pedagogical argument in this piece is that this process of building, living in, and defending Tent/Freedom Cities was a form of Black place-making, a concept that is increasingly discussed in human geography research (e.g., Hawthorne Citation2019; Binoy Citation2022) but that has received little attention in the geography education literature. Black activist communities and their allies built these Tent/Freedom Cities on Black-owned land to provide housing to sharecroppers and tenant farmers evicted by oppressive white landlords for marching, attending mass mobilization meetings, and trying to register to vote. These Tent/Freedom City geographies offer an alternative to the “canon” of Civil Rights Movement memory and representation that has tended to dwell on victimized activists (Berger Citation2014). Curriculum standards typically emphasize this “canon”—the better-known marches, boycotts, and sit-ins—often at the exclusion of the grassroots community-building and organizing that undergirded the Movement. These depictions do not fully capture the agency and identity of mobilized African Americans and the everyday ways in which they challenged white supremacy.

Of particular importance to the theme of geographic mobility developed in the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Tennessee, prevailing curriculum standards speak in limited ways of oppressive mobility control practices behind racism or the fact that white opposition to the Civil Rights Movement brought about displacement and forced movement of some Black community members. Also not often discussed is how these residents responded to this dispossession by refusing to be moved from their communities and carrying out self-determined mobility and settlement that ran counter to the dominant racist social order. Although lasting only about two years, Tent/Freedom Cities kept evicted African Americans from needing to leave their counties, where they were registered to vote and had family ties, and allowed them to maintain a sense of place in opposition to abandonment, forced relocation, and discrimination. In this respect, Tent/Freedom Cities represent a creative form of anti-racist mobility work as well as place-making.

Crucial to viewing mobility as a way of working against the oppression and violence of white supremacy are the ways in which Black individuals and communities were able to develop and operate systems of resistance such as Tent/Freedom Cities. The decision of these communities to remain in the counties where they faced eviction is also critical to this view of anti-racist mobility work. When faced with being forcibly moved from the land their families had sharecropped for multiple generations, many did not leave the county. Instead, those displaced actively constructed a counter-mobility of staying put, reclaiming the right to belong, and fashioning resistant settlements and infrastructures on their own terms. They actively engaged in this place-making not only by establishing their Tent/Freedom City communities but also through the networks and organizations that allowed the acquisition and distribution of supplies necessary to sustain life and the Movement.

Through the Tent/Freedom City geographies, there is an opportunity to re-center neglected places and people from the Movement, especially those people at the intersection of civil rights struggle and the production of home—complete with its joys, struggles, and moments of day-to-day resistance. This historical background on Tent/Freedom Cities of Fayette and Lowndes counties further suggests important pedagogical lessons to be learned beyond the sometimes all-too-familiar keystone events, locations, and leaders that have come to encapsulate the Movement. We identify photographs, first-person accounts, and other primary source documentation for exploring and teaching Tent/Freedom City geographies. We will build on the narrative of resistance and activism by including the stories of everyday people whose survival, living, place-making, and mobility-making are essential to understanding the African American Freedom Struggle and the role that movement and settlement played in that struggle.

Finally, our hope is to facilitate a greater incorporation of Black geographies scholarship into geography education, which was one of the foundational goals of The Role of Geographic Mobility in the African American Freedom Struggle Summer Institute. Some of our work on Tent/Freedom Cities is grounded in the “maroon geographies” and “fugitive infrastructures” described by Winston (Citation2021). Winston stresses Black place-making and survival beyond and against racial violence and abandonment. When she describes “fugitive infrastructures,” she refers to material systems, including non-conforming land uses and dwellings, created by Black communities to sustain life amid oppression. Tent Cities were such an infrastructure that allowed evicted Black families to resist erasure and push back on the control of property that normally undergirded racism. Beyond a temporary home, these encampments became sites of lived resistance, resourcefulness, community-building, and self-defense. In counties that had a majority Black population, the Tent Cities established a way to ensure that voting power among displaced/dispossessed Black communities remained in the county, along with providing for the welfare of those communities. Tent Cities have been ignored or at best downplayed in dominant public commemoration and education about the Civil Rights Movement. This neglect and the difficulty of preserving these relatively ephemeral communities has led to limited scholarly research on them. We suggest that teaching about Tent/Freedom Cities offers an opening for students and educators to use critical imagination to explore these unsung spaces, the activists behind them, and their impact in expanding our understanding of the geographies of the African American Freedom Struggle.

Fayette County, Tennessee

Prior to the beginning of voter registration drives in mid-1959, fewer than twenty of Fayette County, Tennessee’s nearly 17,000 Black residents had exercised the right to vote, fearing intimidation and threats of possible recrimination from whites. Because of those registration drives, more than 2,000 Black residents registered to vote before the general election of 1960 (Ballantyne Citation2021). This in turn led to those who registered to vote having their names put on a “blacklist” by the local White Citizens Council. (Found across the Southeastern United States, White Citizen Councils were organizations of white segregationists and supremacists who opposed integration and other Black strides in civil rights.) As a form of economic coercion, opponents to Black voting distributed this Citizen Council blacklist to local white business owners with the purpose of ensuring that named registered voters would be denied essential goods and services needed to support their families. In addition, recently registered Black voters would not be allowed to rent and farm land owned by white plantation owners who, almost 100 years after the Civil War, still controlled much of the county economy (Ballantyne Citation2021). By the end of 1960, 257 African Americans had been evicted from their land along with their families, suddenly making them homeless (Ballantyne Citation2021). Two Black landowners offered property for sheltering evicted sharecroppers and tenant farmers in what would become Tent City. Tents were initially purchased and collected by local activists such as John and Viola McFerren, and eventually people from beyond the county donated tents for the cause (University of Memphis Citation2019a).

In December of 1960, the U.S. Justice Department sought to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1957, passed to protect the right to vote and investigate discriminatory conditions. The Justice Department filed a case “alleging that some seventy persons [land-owners and merchants] had violated the sharecroppers’ civil rights,” with another filing for an injunction to prevent further retaliatory evictions of Black farmers (Ballantyne Citation2021, 122). These court filings did not stop evictions, however, as landowners used any reason they could fabricate to justify the continued forced movement of Black sharecroppers out of their homeplaces. White plantation owners made disingenuous claims that evictions were necessary because increased mechanization of farm work made Black farm labor redundant.

By January 1 of 1961, 400 families in Fayette County had been ordered to move from the land they were sharecropping. Another 300 in nearby Haywood County were forced to vacate their homes—leading to a second Tent City being established there. It was clearly an example of white suppression of the Black vote since the lack of a residential address in effect disenfranchised farmers; strikingly, only one of the evictees had not registered to vote, according to an outside humanitarian report filed at the time by visiting observers (Anderson, Nelson, and McCrackin Citation1961).

In addition to dealing with the trauma of displacement and dispossession, residents of Fayette County’s Tent City were desperate for food and clothing due to an ongoing economic boycott, especially after the local Red Cross denied aid. John McFerren rented a grocery store to service the Black citizens of the county, frequently driving outside of the county to purchase supplies to sell (Viola McFerren on Blacklist and Getting Supplies: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County, Tennessee Citationn.d.). Additionally, several labor unions across the country such as the United Auto Workers sent supplies and representatives to help those evicted. The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations even provided financial aid for those who still owned land but were being impacted by the economic boycott Black sharecroppers were facing (Ballantyne Citation2021). An article from January 1961 in The Tri-State Defender describes a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) group having sent food and clothing by “eight trucks and airplane to the Tennessee farmers,” with other groups sending supplies to “meet the critical need for children’s clothing, blankets, and food.”

Residents of Tent City referred to it as “Freedom Village” and reportedly had high morale despite enduring “hazardous and difficult” living conditions (Anderson, Nelson, and McCrackin Citation1961). Students from across the country also traveled to Fayette and Haywood counties to bring not only supplies but also support for the voter registration movement, many staying with local Black families and bringing their own supplies and food so they would not be relying on the already limited resources (Ballantyne Citation2021). Through continued economic and social support, the Tent City eventually disbanded in 1963, with many of the residents finding homes, including some who moved to a collective called Freedom Farm (University of Memphis Citation2019b).

Lowndes County, Alabama

At the beginning of 1965, there was not one Black registered voter in Lowndes County, Alabama, and there was only one registered voter by March of that same year (Civil Rights Movement Archive). Evictions of sharecroppers in Lowndes County began toward the end of the 1965 cotton-picking season. A majority of those forced to move off the land and made homeless were farmers and their families who had participated in voter registration or were otherwise active in the Movement (Jeffries Citation2010). In response, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a civil rights organization working to mobilize oppressed communities, helped those evicted to find new housing in tents, creating their own Tent City on seven acres of land on Highway 80 between Selma and Montgomery. The Tent City was envisioned as a temporary measure for sustaining life, maintaining the voting power of Black residents in the county, and creating a highly symbolic reminder on the landscape of the racial inequality rampant in the county and state.

As in Fayette County, the Lowndes Tent City consisted of army surplus tents, no running water or electricity, and one shared outhouse. Some of the tents had holes, and only two had flooring that could help contain heat and protect occupants from the cold, bare ground (Jeffries Citation2010). The SNCC compiled a list of needs, including wood for floors and for fires, refrigerators, non-perishable food, and non-prescription medical items, which were collected by local and national-level progressive organizations (Jeffries Citation2010). Given that these evictions took place after the Bloody Sunday March across the Edmund Pettus Bridge that helped spur the Voting Rights Act of 1965, activists turned to a more permanent solution by filing a lawsuit alleging a violation of the Voting Rights Act.

White landowners justified the eviction of newly registered Black voters in the same way as those in Fayette County, suggesting that it was merely a coincidence (Jeffries Citation2010). Despite the Justice Department agreeing with the plaintiffs (the displaced farmers), the case was dismissed in June of 1966 when Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., ruled that since the plaintiffs did not have a “smoking gun” (or direct proof) that white plantation owners had met and conspired explicitly to evict the registered Black voters, there was not enough evidence for a case (Jeffries Citation2010). As noted historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries effectively argued, “The white landowners [in Lowndes County], though, did not have to hold a secret meeting to reach a consensus about using economic coercion and physical intimidation to slow the movement’s momentum. They understood the stakes and knew instinctively that they needed to resort to the old way of doing things to preserve the racial caste system” (Jeffries Citation2010, 110). And while the oppressive mobility politics of evictions continued, the efforts of civil rights activists to keep dozens of families and registered voters living in the county were a success, in large part due to the construction and maintenance of Tent City (Jeffries Citation2010). Residents were resourceful and resilient for more than two years, as organizers helped them find new jobs, permanent housing, and new lives.

Lessons from Tent City/Freedom City Geographies

Both Tent/Freedom Cities highlight the importance of Black residents controlling their movements and place-making on their own terms and in opposition to white efforts to drive them from where they lived, worked, worshipped, and raised families. These resistant encampments and the wide range of social and spatial practices happening within them illustrate the formation of alternative Black geographies of civil rights activism in which the creation of home became a site of resistant living, political expression, and anti-racist community-building outside of the structures and places we normally associate with protest. Often in our teaching of the “canon” of Civil Rights Movement memory, there is a heavy emphasis placed on the role of highly public spaces—streets, schools, lunch counters, bus terminals, and churches—as key arenas in the struggle for racial equality. Far less discussed is the role of homes as battlegrounds for struggles to enact racial equality and Black self-determination, not just in retaining and exercising the right to vote in their county but also in ensuring bodily survival and material reproduction. Resistance outside the confines of formal protest most assuredly included the struggle for survivability and material reproduction (Alderman and Inwood Citation2016).

Important to geography educators, the homes created in and through the Tent/Freedom Cities of Fayette and Lowndes counties represented a form anti-racist place-making as well as a contesting of the politics of forced removal and migration that white landowners sought to inflict on Black communities. The Tent Cities—although the result of illegal evictions and dispossession—were animated by efforts to achieve Black self-sufficiency and solidarity in a region with a long history of Black communities being exploited by but also stubbornly living in defiance of a white-run plantation economy and set of property relations that was a clear extension of slavery (Woods Citation1998). When the American Red Cross refused to aid Tent City residents in Fayette County, activists mobilized within the Black community and turned to outside allies for help, pushing back on any reliance on what Winston (Citation2021) calls “infrastructures of domination.” These Tent/Freedom Cities also offer a view into daily acts of resistance—such as sheltering, feeding, and protecting one’s family in the face of exclusion and eviction—necessary for creating the “fugitive infrastructures” for sustaining life amid and in opposition to oppression.

Tent Cities also challenge us to represent the identities and strategies of civil rights activists in broader ways than we normally do in classrooms. While these encampments certainly illustrate the severe degree to which Black communities were victimized, they also demonstrate the agency of these communities not only to protest discrimination but also to creatively plan and establish an alternative infrastructure of places, resources, and communities that existed independently of and in opposition to white supremacist–led forced movement and voter suppression. Tent City geographies also make space for teaching about self-defense as a civil rights mobilization strategy. Nonviolent civil disobedience was one of the Movement’s widely embraced and successful principles advocated by Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others. It is so closely associated with how we remember and teach civil rights that it can overshadow or occlude the fact that those nonviolent gains were complemented by and arguably made possible in some instances by the use of weapons to ensure the survivability of civil rights workers against white supremacists who had no problem attacking people of color in light of the lack of protection offered by law enforcement (Cobb Citation2016). In Lowndes County, each tent was supplied with a rifle. One SNCC worker working in the Alabama encampment at the time said, “Tent City [was] like a shooting gallery for local folks in Lowndes County. They used to come by three or four times a week and shoot into Tent City …” (Jansen Citation2012, 110). A resident in Lowndes County, Annie Bell Scott, said “[We] had a lot of peoples around [Tent City] that started shooting back. So that took care of that” (Jansen Citation2012, 111). Ms. Scott’s comments speak to the effectiveness of self-defense in mitigating the daily racialized violence directed at Tent City inhabitants and how this violence threatened not just people’s lives but also their ability to maintain a place of refuge and hence resist displacement and disenfranchisement.

Classroom Application of Tent City/Freedom City Geographies

When we talk about teaching beyond the “canon,” we are referring to those names and events that are usually considered synonymous with the Civil Rights Movement, such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the March on Washington. At the same time, it is important to recognize the necessity for educators to remain within their content standards. While standards vary greatly throughout the country, there are ways that Tent City geographies can be woven through them. While the state of Tennessee’s standard TN.56 specifically mentions the Tent City Movement of Fayette County, other states may have broader standards that enable these discussions. Standards we have reviewed include teaching about various methods employed by African Americans to obtain civil rights. Tent Cities would clearly fit into such an overarching standard. The state of Alabama, for instance, has a curriculum standard that includes explaining the contributions of the SNCC.

In pushing beyond the “canon” of how the Movement is typically taught, the exploration of Tent Cities does not need to replace or usurp these more familiar discussions but can and should be placed within and alongside content already present in the classroom. To reiterate, we feel that a teaching of the topic of Tent Cities can open a space for exploring the deeper relationship between civil rights struggles and the everyday place-making, the claiming and constructing of home, and oppositional mobility work of ordinary Black communities—thus enriching and complicating an image of the Movement that many of our students identify with only in terms of highly visible public protests, court cases, and charismatic national leaders.

Additionally, the geographic location of these two Tent Cities places them in concert with other pivotal moments and people in the Movement. Highway 80 in Lowndes County connects Selma and Montgomery, allowing that effort to be included in lessons about the March to Montgomery, Bloody Sunday, and even the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Fayette County is located not far from Memphis, Tennessee, allowing for its inclusion in discussions of sit-ins, striking sanitation workers, and ultimately the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. These better-known moments and places within the “canon” can also provide students with the necessary context and connections to understand the historical, geographical, and political significance of Tent/Freedom Cities and realize that all of these chapters in the Movement are relationally connected, while also illustrating their own stories. By joining Tent Cities with the traditional canon of teaching topics and approaches, educators can encourage students to recognize that there was not just one Civil Rights Movement and to consider “the different, sometimes conflicting, manners in which movements and individuals envision and enact Black liberation” (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019).

Surviving photographs of and from these Tent Cities provide new ways of visualizing examples of activism. As Berger (Citation2014) notes, many photos were taken during the Civil Rights Movement, but just a few similar images are now commonly reproduced, leaving the mainstream pubic with a highly selective and unrepresentative story of what was activism, who was a freedom-seeker, and where ant-racist mobilization happened. Tent Cities offer an alternative narrative to boycotts, marches, and sit-ins that focus on the lived resistance of the day-to-day necessities of life—cooking dinner, doing laundry, making a home. Continuing to live and to carry on with tasks, despite the structures of oppression and threats of violence around them, is important civil rights work. Surviving photos of Tent/Freedom Cities can work to bring humanity to those fighting for justice and self-determination.

One of the most evocative sets of photos to come out of the Lowndes County Tent City shows a female resident and her daughter sitting on a portable camp bed or cot near their tent home. While life obviously looks hard and stressful for them, they are shown smiling and laughing—an image that speaks to the moments of dignity, resiliency, and joy that constitute civil rights struggles and Black geographies (). These types of images are not often part of the more established photographic record, and asking students to reconcile the juxtaposition of different representations of the Movement (e.g., photos of Lowndes Tent City alongside photos of marchers on the Edmund Pettis Bridge) can help create valuable educational moments. Another set of Lowndes County photos from around the same time shows a father and son working to cook a Christmas dinner inside their modest Alabama tent (). While speaking to the difficulty of the conditions (they are cooking with little in the way of a table and with a crude floor), the photography speaks more powerfully of a long history of resistant Black foodways, the maintenance of the Black families and homes in the face of oppression, and how even the most ordinary daily practices are also political practices for enacting a more just world. Some photos can be found in an issue of Jet from March 10, 1966, from an article “Aftermath of Ala. Negroes who seek to vote” on pages 14 through 20. The full issue and article are accessible through Google Books, and they provide students with not only photographs that illustrate life in Tent City but also an article that is a good length for a classroom lesson.

Figure 1. Woman and little girl on a cot in the dirt yard in front of the tent where they are living in Lowndes County, Alabama. Credit: Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Figure 2. Roosevelt Scott and his father prepare a holiday meal inside their family’s tent in Lowndes County, Alabama. Credit: Alabama Department of Archives and History.

On YouTube, The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change, which has championed the retelling of the history of West Tennessee’s voting rights struggle, has more than 100 short video segments that can easily be used within the classroom. These videos create moments for teaching about and using oral histories in geography classrooms that all too often reduce the human experiences of place and movement to statistical data or patterns on maps. For example, several residents in video segments discuss their experiences living in the Fayette County Tent City: “Me and her and the four kids, we lived in that tent, we cooked in that tent, and we slept in that tent. Sixteen foot, a little bitty. But in the winter time, that tent would get like a deep freeze. Ice solid. All over sides and walls and top, solid with ice” (Early B. Williams on Living in Tent: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County, Tennessee, Citationn.d.). Early B. Williams describes being shot at in his tent (Early B. Williams on Being Shot and Violence: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County, Tennessee Citationn.d.). Williams’ wife Mary explains how the floors were initially cardboard, but once the heater thawed out the ground, mud began to come through the cardboard (Mary Williams on Moving into Tent City: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County, Tennessee Citationn.d.). Beyond just discussing their experiences in Tent City, the videos discuss voter registration, sharecropping, desegregation, and integration—all topics educators can connect to existing standards within curriculum while introducing students to new figures in the movement.

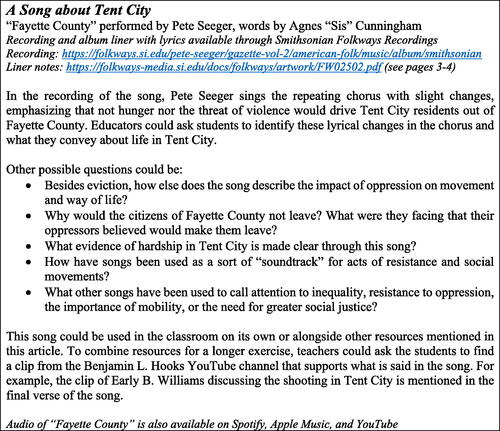

Another practical way to include these stories in the classroom is through Evicted! The Struggle for the Right to Vote (Duncan Citation2022), a picture book written by Alice Faye Duncan and illustrated by Charly Palmer. The highlights include a number of lesser-known figures in the Civil Rights Movement in Fayette County, many of whom are featured in clips on The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change YouTube channel. With the book, the Hooks Institute website also provides access to a teacher guide for using Evicted! in the classroom. The guide (Sapp Citation2022) has nearly twenty discussion questions and writing prompts; a lesson on the use of media in the Civil Rights Movement; a lesson about voter suppression using a 1965 literacy test; and activities to connect the past and the present moment, such as voter suppression in recent elections and evictions as a civil rights issue during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another project mentioned in the guide is the use of oral histories—not just learning from them, but students making their own. Students can ask an older family member or friend about their own experiences voting or perhaps their memories of the Civil Rights Movement. Once again, students have a chance to go beyond the textbook or “canon” of figures and events and touch more closely those stories that have impacted them and their own communities. One can find via Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube a song written by protest musician and songwriter Agnes “Sis” Cunningham originally performed by folk singer Pete Seeger (Citation1961) about Fayette County’s Tent City. Playing and analyzing the song in the classroom would be useful for facilitating student discussions about the resilience of Tent City residents to move and stay on their own terms and the harsh conditions and violence they faced in the encampment ().

Concluding Remarks

The past several years have seen growing calls to enhance the teaching of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black experience more broadly within geography classrooms (Alderman, Kingsbury, and Dwyer Citation2013; Inwood Citation2017; Eaves Citation2020). Our exploration of Tent/Freedom Cities responds to those calls while also demonstrating the kind of pedagogical discussions held at the National Endowment for Humanities institute in the summer of 2022. The institute sought to highlight the role of geographic mobility in the African American Freedom Struggle and the landscapes of racial control or resistance created by those movements. Tent/Freedom Cities in both Fayette County, Tennessee, and Lowndes County, Alabama, offer educators ways of teaching about the forced removal and abandonment of Black communities during the Civil Rights Movement along with how those communities contested this racism by refusing to move out of their home counties and worked among themselves and with allies to create and relocate to alternative home spaces. These insurgent encampments represent a neglected chapter within the “canon” of what has tended to be commemorated and taught about the Civil Rights Movement. More broadly, Tent/Freedom Cities do not just advance our teaching of the Movement; rather, they speak to how the African American Freedom Struggle can expand our understanding of the foundational role that geographical themes such as mobility, place, and home play in the fight for social justice.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katrina Stack

Katrina Stack is a PhD Candidate at the University of Tennessee in the Department of Geography and Sustainability, where she studies cultural historical geography and geographies of memory with a focus on race, public memory, heritage tourism and preservation, and critical place naming.

Derek H. Alderman

Derek H. Alderman is a Professor in the Department of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and founder of Tourism RESET, an organization that studies and challenges racial inequalities in travel, tourism, and geographic mobility. He is a cultural historical geographer interested in public memory, race, civil rights education, critical place naming and mapping studies, and politics of geographic mobility and travel, often in the context of the African American Freedom Struggle.

Notes

1 We elect to deviate from the journal’s use of The Chicago Manual of Style and capitalize the word “Black” when referring to people and communities. This follows (and is in solidarity with) the conventions of the growing Black geographies field. Use of uppercase recognizes the shared sense of identity and struggle against discrimination long defining Black experiences. We have also elected to adhere to the journal’s style and set “white” in lowercase. There is considerable divided opinion among publishers and academicians about whether to capitalize “white” or not. We are also sensitive to the argument of many media outlets and presses, which points to the use of the capitalized “White” by white supremacists and the importance of undermining the legitimacy of their beliefs and practices.

References

- Alderman, D. H., and J. Inwood. 2016. Mobility as antiracism work: The “hard driving” of NASCAR's Wendell Scott. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (3):597–611.

- Alderman, D. H., P. Kingsbury, and O. J. Dwyer. 2013. Reexamining the Montgomery bus boycott: Toward an empathetic pedagogy of the civil rights movement. The Professional Geographer 65 (1):171–86.

- Anderson, R., W. Nelson, and M. McCrackin. 1961. Report on visit to Fayette and Haywood counties, Tennessee, January 3, 4, and 5, 1961. Box 5, Carl and Anne Braden Papers, MS 425, University of Tennessee Special Collections Library, Knoxville, Tennessee. https://digital.lib.utk.edu/collections/islandora/object/volvoices%3A7217.

- Ballantyne, K. 2021. “We might overcome someday”: West Tennessee’s rural freedom movement. Journal of Contemporary History 56 (1):117–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009420961449.

- Berger, M. A. 2014. Freedom now!: Forgotten photographs of the civil rights struggle. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Binoy, P. 2022. Remembering Rondo: Black counter-memory and collective practices of place-making in Saint Paul’s historic black neighborhood. Geoforum 133:32–42.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019. The pluralities of Black geographies. Antipode 51 (2):419–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12467.

- Civil Rights Movement Archive. SNCC News Release. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.crmvet.org/docs/651229_sncc_lowndes-tents.pdf.

- Cobb, C. E. 2016. This nonviolent stuff’ll get you killed: How guns made the civil rights movement possible. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Duncan, A. F. 2022. Evicted!: The struggle for the right to vote. Westminster, MD: Calkins Creek.

- Early B. Williams on Being Shot and Violence | Voices of the Movement: Fayette County, Tennessee. n.d. BenLHooksInstitute YouTube Channel. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/@BenLHooksInstitute.

- Early B. Williams on Living in Tent | Voices of the Movement: Fayette County, Tennessee. n.d. BenLHooksInstitute YouTube Channel. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/@BenLHooksInstitute.

- Eaves, L. E. 2020. Interanimating Black sexualities and the geography classroom. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 44 (2):217–29.

- Hawthorne, C. 2019. Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty‐first century. Geography Compass 13 (11):e12468.

- Inwood, J. F. 2017. Critical pedagogy and the fierce urgency of now: Opening up space for critical reflections on the US civil rights movement. Social & Cultural Geography 18 (4):451–65.

- Jansen, H. 2012. From Selma to Montgomery: Remembering Alabama’s civil rights movement through museums. Unpublished thes., Florida State University. http://npshistory.com/publications/semo/jansen-2012.pdf.

- Jeffries, H. K. 2010. Bloody Lowndes: Civil rights and Black power in Alabama’s Black Belt. New York: NYU Press.

- Mary Williams on Moving Into Tent City: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County Tennessee. n.d. BenLHooksInstitute YouTube Channel. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/@BenLHooksInstitute.

- Rodríguez, N. N., and A. Vickery. 2020. Much bigger than a hamburger: Disrupting problematic picturebook depictions of the civil rights movement. International Journal of Multicultural Education 22 (2):109–28.

- Sapp, D. 2022. Discussion guide: Evicted! The struggle for the right to vote. New York: Astra Publishing House. https://www.memphis.edu/tentcity/resources/pdfs/evicted_teachers_guide.pdf.

- Seeger, P. 1961. Fayette County. In Story songs: A baker’s dozen of American ballads about 3 saints, 4 sinners, and 6 other people. Columbia Records, track B4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JKFJbAxBOE

- Southern Poverty Law Center. 2011. Teaching the movement: The state of civil rights education in the United States 2011. Montgomery, AL: SPLC.

- Swalwell, K., A. M. Pellegrino, and J. L. View. 2015. Teachers’ curricular choices when teaching histories of oppressed people: Capturing the US civil rights movement. The Journal of Social Studies Research 39 (2):79–94.

- University of Memphis. 2019a. Tent City: Stories of civil rights in Fayette County Web Site: Fayette Timeline 1960. Last updated May 11, 2023. https://www.memphis.edu/tentcity/movement/fayette-timeline-1960.php.

- University of Memphis. 2019b. Tent City: Stories of civil rights in Fayette County Web Site: Fayette Timeline 1963. Last updated May 11, 2023. https://www.memphis.edu/tentcity/movement/fayette-timeline-1963.php.

- Viola McFerren on Blacklist and Getting Supplies: Voices of the Movement, Fayette County Tennessee. n.d. BenLHooksInstitute YouTube Channel. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/@BenLHooksInstitute.

- Winston, C. 2021. Maroon geographies. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111 (7):1–15.

- Woods, C. 1998. Development arrested: The blues and plantation power in the Mississippi Delta. New York: Verso Books.