ABSTRACT

In the age of climate change, the Instagram influencer is still a popular role model for ways to navigate the modern world, and they present us with their visual practices of self-presentation as well as their activism, lifestyle, and business model. However, conspicuous consumption – once a hallmark of success – is now being challenged, and perhaps a paradigm shift is building with the new breed of climate influencers with engaged expertise and ethical vigilance. The aim of this paper is first to identify climate celebrities and then to focus specifically on macro influencers, such as activists or actors, and on micro-influencers, such as entrepreneurs. The article examines how they communicate climate change applying different strategies on Instagram while remaining authentic, using concepts from research on social media within studies of celebrity culture and in climate celebrity communication Second, we demonstrate a shift taking place in the way climate change is communicated: from traditional legacy-media advocacy by celebrities to activists and entrepreneurs performing sustainable everyday practices on social media. This work will contribute directly to how we analyse both the macro and micro-climate influencer as a role model in the age of climate change, providing solutions for coping, engaging and taking action.

Introduction

Climate change is a central political issue of our time, and celebrities have been key players in communicating the topic to a wider audience (Brockington Citation2009, Goodman and Littler Citation2013, Hammond Citation2017). However, these key players approach this political and environmental self-expression in quite different ways that are now very much dependent on whether they are macro-influencers – with a career beyond social media as achieved celebrities (Rojek Citation2001) – or micro-influencers – famous through their strategic self-presentation on social media and treating followers as fans (Senft Citation2008, Marwick Citation2015) with a more intimate relationship with their followers. When addressing climate change, celebrities enter the realm of political communication, and they have now, in many ways, become important figures in today’s political culture (Budabin & Richey Citation2021; Chouliaraki Citation2013, Wheeler Citation2013; van Zoonen Citation2005). To generate a comprehensive reading and understanding of this clearly political relationship between celebrities and celebrity politicians, it is useful to include John Street’s related distinction between, first of all, ‘the traditional politician who engages with the world of popular culture in order to enhance or advance their pre-established political functions and goals’ (Street Citation2004, p. 437) like former US president Barack Obama or former Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel; and in contrast, the ‘entertainer who pronounces on politics and claims the right to represent peoples and causes but does so without seeking or acquiring elected office’ (Street Citation2004, p. 438). This distinctive difference is exemplified by the political presentations of public individuals – from the popular music star and philanthropist Bono to the ever-present and politically engaged Hollywood actress Angelina Jolie to the climate micro-celebrity and the public intellectuals like Noam Chomsky. This article concentrates specifically on the type of political celebrity who focuses on climate change but is not running for office. Furthermore, we want to demonstrate how specific types of climate celebrities approach the subject differently through their individual social media profiles as either macro or micro-influencers (Kay et al. Citation2020, Abidin Citation2021).

Our research also builds on a particular ‘pandemic’ constitution of fame and politics (Marshall Citation2020) in which influencers – which include, in our work, both macro and micro-influencers – define a new patterning of how an important and significant issue around environmental sustainability is articulated, shared, and made tangible in and through social media platforms. However, the very idea of what we have identified as climate influencers operates in very different ways in their individual and collective addressing and engaging with climate change issues and performing authenticity as a key part of the presentations of self. Moreover, they also need to be understood in a wider (historical) context of celebrity culture. First of all, influence and connection have altered quite significantly over the last 15 years and are dramatically shifting the formation of visibility of key individuals on social media. This paper explores how this transformation of our public personality system, which still mixes a celebrity system of influence from the past, where fame was either inherited or based on merit (Rojek Citation2001), with an emerging and expanding influencer culture, and how the transformation plays into the way that particular forms of cultural politics are also mutating. The paper focuses specifically on three different types of climate influencers and how climate change as a highly visible issue is configured differently through their social media formations of influence, connection, and (self-)presentation, as well as how they perform authenticity and an emotional framing that seeks to be congruent with their respective agendas. It provides a critical theoretical modelling of examples of climate change activity that is part of the array of what we would define broadly as climate influencers. These climate influencers can be configured into three main categories of influencers, preliminarily defined by their interest in climate change as a central part of their online identity, and that they are not seeking political office. We thus make a distinction between different kinds of climate celebrities: there is the climate politician and then there is a different type of climate influencer that includes these three main categories. We build on the broad definition of an influencer as often a commercial practice of performing a branded self on social media (Hearn and Schoenhoff Citation2016, p. 205, Hund Citation2023, pp. 13–14) that can encompass traditional celebrities (stars, journalists, activists) and micro-celebrities (fashion and food lifestyle influencers and activists) communicating ideas as well as those practicing sustainable living and consumption:

Activist macro-influencers who have built their impact on climate change specifically through social media profiles and (self-)presentation but usually combined with a high visibility in legacy media. They can be characterised as being outside the entertainment industry, e.g. as activists or public intellectuals, and they have an explicit political agenda and invitations to consume are related to their own publications.

Star macro-influencers who have built their social media influence in the entertainment industry, e.g. as movie stars, that predate their social media activity. Their social media posts include promotions for professional work as well as endorsements. Their climate change engagement is often concerned with celebrity advocacy or philanthropy and in cooperation with NGOs such as the UN.

Micro-influencers who have a career and a commercial business through social media and have worked to build followers specifically through their environmental and political positioning, combining both activism and entrepreneurship.

Our study analyses the strategies at work in these three forms of influencers primarily through their presence on social media platforms with the focus on Instagram. It investigates this changed celebrity system in terms of how it now works its way into the issue of climate change as well as an emerging reconfiguration of activism with authenticity and emotional framing as distinguishing factors. It is a qualitative study focusing on specific categories of climate influencers and does not claim to be entirely representative. Rather, we have chosen and selected to analyse what Yin identified categorically as ‘extreme cases’ (Yin Citation2009, p. 47) and demonstrate how and what the individual types and related agendas derived from these examples are communicating about climate change and making related claims about how we (in both an individual and collective sense) should operate in this transformed world. Specifically, our research questions are:

How do climate celebrities in the shape of macro and micro-influencers construct and communicate climate change on social media?

How has the role of climate celebrity changed when being on social media?

Mapping the emergent “climate influencer”

From an overarching perspective, climate influencers are a type of climate celebrity who are not politicians or seeking office but those who have the issue of environmental sustainability as a central part of their public persona as well as their presentation of the self on social media. Thus, the term climate celebrity covers a spectrum of personas from what we have identified as macro-influencers which include the categories of Hollywood stars and activists and then on to self-made micro-influencers. But how do we go about defining a climate celebrity accurately? Climate celebritydom is a complex cross-cultural structure: each climate celebrity is simultaneously a ‘non-state actor’ as well as being recognised as an ‘authorised speaker’ placed between science, politics, and entertainment (Boykoff and Goodman Citation2009, p. 395). The ‘climate influencer’ embodies what Corner and Pels call a modern ‘political style’ that combines the ‘issue-specific’ – because they focus on climate change as a key political issue and the ‘personality bound’ because the issue is an integral part of how they present themselves online (Corner and Pels Citation2003, p. 7).

The definition of the three categories of climate influencers we described above builds on the characterisations of environmental advocacy in Abidin et al. (Citation2020) combined with a specific focus on how they present themselves on social media (Marwick Citation2015). Extending Abidin’s hierarchical classification of influencers where macro-influencers having more than 500,000 followers are at the top of the hierarchy, whereas micro-influencers with less than 500,000 are at the bottom (Abidin Citation2021, p. 6), we propose a useful simplification of this analysis through our focus on international climate influencers with a Western bias. However, the difference between these three categories of climate influencers also concerns how macro-influencers address followers, a way that normalises a broadcast kind of communication of ‘the one to many’ (Marwick and Boyd Citation2010, p. 129): thus, since the macro-climate influencer has, as mentioned above, established their fame ‘outside of social media’, often they have too many followers to engage directly in dialogue online. In contrast, the micro-influencer is more likely to be engaged in dialogue with followers (Marwick Citation2013, p. 5).

In tracking the extant research on climate celebrities in general (e.g. Brockington Citation2009, Boykoff and Goodman Citation2009, Goodman and Littler Citation2013, Hammond Citation2017), no focus on how this particular issue is communicated via personal profiles on social media is evident. A more recent characterisation of ‘environmental celebrities’ recognises that climate change is presented by many different types of celebrities (Abidin et al. Citation2020, p. 393). Related research in marketing studies, in contrast, has highlighted ‘the greenfluencer’ as the research core objective: in particular, marketing research has pointed towards how influencers make sustainable products their primary promotion and clear source of advertising income (Breves and Liebers Citation2022, p. 784). Furthermore, as part of a corporate responsibility programme, Hearn analyses how young stars become ‘celebrity-brand activists’ making ‘environmentalism a cause célèbre’ as an element of the Disney company’s website (Hearn Citation2012, p. 30 + 34) and making climate-friendly products part of their ‘commodity activism’ (Banet-Weiser and Mukherjee Citation2012, p. 13).

Even though climate engagement by celebrities is not new (Hearn, Citation2012, Wheeler Citation2013, Goodmanet al. Citation2016, Hammond Citation2017, Robeers and Van Den Bulck Citation2019), there has been a shift in how they engage and present their advocacy. This shift concerns media representation as well as the issues addressed because ‘(t)here is an individualised and personalised media structure that is advancing in contrast to representation’ (Marshall Citation2020, p. 101). When communicating environmental issues before the advent of social media, the individual celebrity activist, such as Brigitte Bardot saving seal pups in Greenland in the 1970s and Sting’s concerts supporting the protection of the rainforest in the 1980s, depended on their activities being reported by legacy media. Later, Al Gore’s agenda-setting documentary An Inconvenient Truth (2006), followed by his Nobel Peace Prize, had an impact on political debate but was also important because it used the personal narrative as a way of making the issue both authentic and relatable. This strong focus on the personal and individual perspective dominates the narrative in contemporary online culture and has become central when communicating about climate change on social media. Perhaps, Al Gore’s narrative combining climate change with personal knowledge-seeking and the individual narrative set the mould for how we see an activist such as Greta Thunberg, characterising her Asperger’s as her ‘superpower’ and making it part of her activist narrative on social media (Murphy Citation2021, p. 198).

How does this personalisation connect with the climate change issue? This ‘mainstreaming’ of climate change as a relevant and broadly accepted issue means, according to Goodman et al., that there is now this shift to an ‘after data’ (Citation2022, p. 1) mood, which translates into a declining interest in informational narratives simply presenting ‘dry accounts of the latest specific knowledge about the changing climate, to stories of personal/or literal journeys upon the climate landscape and those of climate-related impact’ (Boykoff and Goodman Citation2009, p. 12). Perhaps this particular transformation, from a focus on information to personal journeys, is a result of climate change becoming a globally discussed issue. Brockington explains this shift and the way it interacts with celebrity and perhaps the emotional attachment and sensitivity around this environmental activism: ‘the prominence of the climate change agenda in recent years has multiplied the mutually enjoyable benefits celebrities and environmental causes provide to each other’ (Brockington Citation2009, pp. 39–40). In a similar way to Brockington (Citation2009), Boykoff and Goodman use their concept of ‘after-data’ to describe how the role of the climate influencer indicates that it is no longer enough to explain the science or insist that this is relevant and important, but instead the focus is on how they engage personally with the subject (Goodman et al. Citation2022, p. 1).

Witnessing and emotional framing

Climate change as an issue has become more mainstream. In their analysis of Leonardo DiCaprio’s documentary, The 11th Hour (Citation2007, 2024), Boykoff and Goodman identify useful strategies of engagement in climate change, including providing factual information, witnessing, and emotional framing (Boykoff and Goodman Citation2022, p. 15): Celebrities, in general, have the ‘capacity to house conceptions of individuality and simultaneously embody or help “collective configurations” of the social world’ (Marshall Citation2014 , 1997, p. xi-xii). In other words, climate celebrities are showing us how to engage with climate change on a personal level. They become aspirational role models (Warner Citation2013, Marwick Citation2015), and they do so by seeking knowledge and bearing witness, as well as normalising engagement, including ‘emotion as a response and as a motivational force to “solve” climate change’ (Boykoff and Goodman Citation2022, p. 15).

DiCaprio thus represents how the Hollywood celebrity engages with climate change in a documentary, but if we look at his Instagram account, the witnessing is performed, but the personal and emotional are usually absent from his posts. In contrast, Greta Thunberg, as mentioned above, has a very personal narrative on Instagram and combines witnessing and emotional framing such as expressing anger and using humour to get her message across (Murphy Citation2021).

There is the macro-influencer as the Hollywood star witnessing and full of empathy – but who rarely engages in a climate-friendly lifestyle but prioritises to convey information; or, like climate macro-influencers such as Mark Ruffalo, on a regular basis, address current climate politics and display their emotional investment. In contrast, we have the macro-influencer like the activist Thunberg who practices and documents the lifestyle she preaches, and we can follow her sailing across the Atlantic and by train in Europe on her social media accounts. Nonetheless, there are macro-celebrities who also demonstrate a lifestyle that accords with a more sustainable way of living. Take the ‘vegan celebrities’, for example, including the former talk show host Ellen DeGeneres and Hollywood actor Alicia Silverstone, both of whom advocate for a vegan lifestyle through educational and campaigning work in legacy media (Doyle Citation2016). Both of these macro-celebrities use veganism as an ‘important critique of unsustainable food practices’ (Doyle Citation2016, p. 787). Interestingly, the vegan lifestyle is presented as an individual choice: It is ‘refigured as the individual choice to be a healthy, happy and kind self, consistent with the motivational practices of a lifestyled consumer politics’ (Doyle Citation2016, p. 788). In this way, the sustainable lifestyle is somehow not a political issue at all, and the Hollywood stars can uphold their broad appeal and make it a fundamentally individual choice.

Clearly, there is a relationship in this emotional framing by celebrities designed to produce what could be described as an affective (Massumi Citation2015) patterning that draws followers on social media closer to a commonality around influencers addressing climate change and future sustainability. In many ways, this structuring of affect to emotion to collective alliances with influencers fits into the way that social media correlates contemporary sentiment (Marshall Citation2022). This study of climate influencers, both macro and micro, further underlines the personalisation transformation that social media advances through a sense of para-social (Horton and Wohl Citation1956) connection by massive numbers of followers – some who are building markets (Breves and Liebers Citation2022) and others who have established entertainment visibility that defines their perhaps more culturally valued market. Furthermore, the way they perform their authenticity is connected to their status as role models and influencers.

The formation of authenticity: role models in the emergence of KOLs

Circulating in and through the formation of influence more generally and climate influencer culture more specifically is what can be described as an authenticity that is also aligned to what we have identified as the emotional affiliation built between the influencer and their followers. For the climate influencer, authenticity is based on the ‘congruence between the influencer’s image and the message’ (Boerman et al. Citation2022, p. 921) and can depend on a different set of cultural and national contexts as shown in the analysis of female Arab influencers on Instagram (Hurley Citation2019) and different types of Asian YouTubers (Abidin Citation2018). Congruency, however, has general relevance because, according to Boerman et al., celebrities, when ‘campaigning for pro-environmental behaviour, are often accused of hypocrisy due to the incongruence between their environmental communication and their behaviour’ (Boerman et al. Citation2022, p. 921). It thus makes sense, based on this reading of the significance of congruence for celebrities, that even a climate micro-influencer with the singular issue of climate change would be vulnerable and totally dependent on performing the right kind of consumption to avoid contradictions. Similarly, the climate macro-influencers also need to make sure that hypocrisy is not suspected or detected in their climate-issue congruence (Robeers and Van Den Bulck Citation2019, p. 452).

Authenticity is a performance central to our understanding of celebrities, from film stars (Dyer Citation1979), who are often also macro influencers, to contemporary micro-influencers (Marwick Citation2015, Baym Citation2018, Hund Citation2023). Indeed, on social media, authenticity can be understood as a central currency (Enli Citation2017) that works in different ways. In The Influencer Industry: The Quest for Authenticity on Social Media, Emily Hund stresses that ‘the meaning of authenticity is always changing’ and the ‘industrial version is just one of many versions’, but still the performance of authenticity remains a central ‘measuring stick’ (…) ‘by which stakeholders value influence’ (2023, p. 169–171).

Marwick’s analysis of the different conceptions of authenticity for fashion bloggers concludes that they can be authentic by having 1) truthful self-expression (honesty), 2) responsiveness to audiences, and 3) honest brand engagement. It is important to stress in the presentation of the online public self that there is no contradiction between being truthful and being commercial, even if you are paid to promote products by a collaborator (Marwick Citation2013, Poell et al. Citation2022). When analysing a climate micro-influencer, this is very often the performance that they aspire to: a truthful expression of ‘practicing what they preach’, being in dialogue with followers, and honest brand engagement. This style of social media performance directly addresses the issue of sustainable consumption, which is considered legitimate and thus honest, but still has some economic currency for the influencer. The personal ethics related to what brands to endorse might be evaluated and discussed on an individual basis, and thus there might be different comfort levels conveyed by an array of brands (Marwick Citation2013, p. 6). Authenticity, when analysing climate influencers including both macro and micro, is connected to how the climate change issue is performed on the social media profile, but it also works differently depending on whether ‘you’ are an activist or celebrity macro-influencer because you do not necessarily display your private life on your own social media profile. In contrast, the micro-celebrity is dependent on ‘the always-on’ of Instagram as well as the connection and exchanges with followers (Marwick Citation2015) and the shared intimacy of their daily life as part of their performance (Senft Citation2008, Marwick Citation2015, Marshall Citation2010).

‘The authentic person’ is, for the micro-influencer, constituted by their honest communication of their own opinions as well as their perceived closeness to the audience (Van Driel and Dumitrica Citation2021, p. 75). Sharing their everyday practices is essential for the influencer: ‘These snippets of everyday life that the influencer share in their feed have to align with the persona they have chosen to present’ (Van Driel and Dumitrica Citation2021, p. 75). Nonetheless, as Hou explains, influencers’ performance is based on a ‘staged authenticity’ and ‘managed connectedness’ with the audience (Hou Citation2018, p. 534). The narrative of authenticity for climate micro-influencers is thus constructed in different ways, and the performance can vary (Poell et al. Citation2022, p. 152) depending on their presentation of self, but the relationship with the audience also contributes to its formation (Baym Citation2018, p. 173) and their status as role models.

So, with both macro and micro-influencers presenting themselves as role models concerned with climate change, in what ways are they operating differently and displaying a distinctly different structure of appeal to followers? The reading of influencers in terms of the key opinion leaders (KOLs) is connected to the idea of the role model, something that has defined stardom and celebrity and how the power of these public individuals has an impact on the everyday lives of audiences (Stacey Citation1994).

It is Katz and Lazarsfeld (Citation1955) who originally developed the concept of an ‘opinion-leader’ and the ‘two-step-flow’ model (Citation1955, pp. 31–42). This model demonstrates how the communication unfolds from the opinion leader and then influences the communication by individuals and groups, such as local communities associated with an opinion-leader (Katz and Lazarsfeld Citation1955). Although far from an identical study of the way communication operates via social media and its interplay with climate change as a political and cultural issue, Katz and Lazarsfeld’s work does identify the communication and connection pathways among individuals and groups that are useful in understanding how the various levels from macro-influencing to micro- (and even nano-) influencing now define the movement of ideas and opinions in contemporary culture. The contemporary marketing-based definition concerned with digital media culture’s individualised structure of connection is called a Key Opinion Leader, which has been turned into the now very well-known Katz and Lazarsfeld-originally-inspired acronym: KOL. Transnationally, in social media marketing, KOLs are characterised as ‘generally realised traffic by means of product endorsements’ (Jin et al. Citation2021, p. 142869). ‘KOLs play important roles in diffusing information, setting agendas, and influencing others’ decision-making or behaviour’ (Luqiu et al. Citation2019 in Ming Liu et al. Citation2022, p. 1). Invitations to consume are mixed with ideas and opinions in the structure of this commercial characterisation of influencers known as KOLs. As a result, the micro-influencer promoting sustainable products and presenting their relatable everyday zero-waste lifestyle while also being part of an online community qualifies as a KOL and a role model, whereas the macro-influencer typically functions solely as a role model.

The climate macro-influencers – activists and stars

Our category of macro-climate influencers comprises two types best defined as activists/public intellectuals and stars. These macro-influencers’ claims to fame have been established outside social media as argued above, and they have added directly to their climate influence through their public presentation of the self online (Marshall Citation2010) and their visibility and voice as climate change advocates ().

Table 1. Climate macro-influencers – activists and stars on social media (accessed 16 January 2024).

The activists and intellectuals as activist climate macro-influencers either communicate climate change through the representation of their work, including activities, presentations, articles, speeches and travel, or by engaging with organisations and politicians. Often, they are in direct social media-conveyed dialogue, with the establishment participating in summits and UN climate conferences. They are in the business of ideas, and they need to be perceived as credible and trustworthy. Typically, they are active on Twitter and comment on current events related to climate and share news, reports and engage in debates.

High-profile activists and public intellectuals such as George Monbiot and Naomi Klein have published books and worked as professional commentators and journalists for years. The high-profile climate change activist Greta Thunberg is an outlier because she gained prominence almost exclusively through social media, followed by the attention of legacy media and then became the poster girl for the young climate movement (McCurdy Citation2013, Sjögren Citation2022). Thunberg and the German activist Louisa Neubauer both started out as micro-influencers but have, through their presence on social media, voiced their critique and dissatisfaction with how the political establishment has chosen to engage with the climate crisis (Murphy Citation2021).

The climate macro-influencer communicates in very different ways. Whereas the professional intellectuals prefer Twitter, the younger activists operate across multiple platforms highly effectively and engage in visual communication on Instagram. Where Klein and Monbiot have focused on keeping distance, preferring witnessing and commentary which supports their authenticity because their congruence is based on their written arguments in tweets, Neubauer and Thunberg have accentuated the emotional framing, and witnessing is replaced by participation in marches and protests using the visual affordances of Instagram. For them, there is congruence between arguing against fossil fuel online and being arrested at a demonstration and documenting it on social media, and Thunberg famously every Friday posts a photo of herself with her sign ‘Skolstrejk för Klimatet’ to document her resilience ().

Figure 1. Climate macro-influencers: Screenshots of extracts from activist macro-influencer @greathunberg and star macro-influencer@leonardodicaprio.

Star climate macro-influencers are traditional stars, e.g. in film or music, who use their fame to shine a light on the cause of climate change. Their fame is based on their presence in legacy media, but on Instagram, they can present their own, controlled public presentation of the self. However, it is typical that access to the public presentation of the private self is limited because the focus is simultaneously on the advocacy of climate change and the professional PR and promotion related to the celebrity/star’s new film or concert tour. Stars like Emma Watson, Leonardo DiCaprio, Mark Ruffalo, and Jane Fonda do not share information about how climate – friendly and environmentally focused their private lifestyles are, but nonetheless engage in celebrity activism and advocacy (Haastrup Citation2018). They make the climate narrative a personal one – but do not share whether they live a sustainable lifestyle, but still, as argued by Littler, the personalising of the advocacy becomes part of their own story (Littler 2008, p. 238 in Hammond Citation2017, p. 98): Jane Fonda participates in campaigns like Fire Drill Fridays, Emma Watson promotes UN Fossil Fuel Treaty, and DiCaprio posts photos of his UN-advocacy work in Brazil. Mark Ruffalo differs slightly because he posts personal anniversaries with private photos interspersed with posts on climate change literature and professional achievements. In contrast, the Clueless-actress (Citation1995) Alicia Silverstone’s Instagram is dominated by her vegan agenda, posting photos from her own kitchen, prioritising her private presentation of self, making a point of how she enjoys vegan food, and both having fun with new recipes and sharing it with friends and family.

Climate and the micro-influencer activists and entrepreneurs

The climate micro-influencer celebrities have typically established their fame based solely on their social media presence, and sustainability and climate change are usually part of their ‘claim to fame’ and the overall purpose of their online profile. In this sense, they have a very different starting point than the star or activist climate macro-influencers. They typically demonstrate the ‘always on’ online presence and maintain their online availability (Mullen Citation2010 in Marwick Citation2015, p. 140). The climate micro-influencer is usually an entrepreneur but can also be an activist and, either way, they are making a living being online based on promoting sustainable products, events and consumption (Hearn and Schoenhoff Citation2016, Abidin et al. Citation2020, Schmuck Citation2021). They are oftentimes engaging in ‘commodity activism’ by promoting sustainable consumption (Banet-Weiser and Mukherjee Citation2012) as well as presenting themselves as amateur experts and providers of information on living sustainably (Hautea et al. Citation2021, p. 7 + 9).

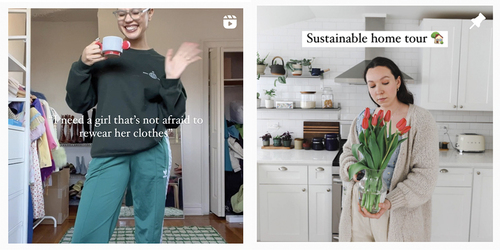

If we take the key characteristics that Marwick ascribes to micro-celebrities in general, they typically include what she calls ‘aspirational consumption’, a practice where cheaper brands are bought to invoke the aura of an unattainable luxury brand (Welch Citation2002 in Marwick Citation2015, p. 156) with ‘microcelebrities creating content that portray them in a high-status light, simulating the attention given to celebrities’ (Marwick Citation2015, p. 156). This is also true of climate micro-influencers: the difference is that they only focus on sustainable consumption or recycling, such as where to get vintage fashion or on ‘how not to consume’ which is often how to mend or upcycle clothes. The climate micro-influencers on Instagram establish a specific lifestyle communicated as in ‘visual narratives’ (Serafinelli Citation2018, p. 110) in order to be both recognisable to their followers and also create ‘visual consistency’ in their personal brand (Maares et al. Citation2021, p. 7) ().

Table 2. Climate micro-influencers on Instagram advocating climate change through lifestyle and activism (Accessed 16 January 2024).

When looking at climate micro-influencers, we typically follow the curated version of their everyday life in contrast to the climate macro influencers. Their public presentation of the private self shows followers a narrative of what an environmentally conscious but still aesthetically pleasing and enjoyable life might look like. In that way, they engage in aspirational consumption but link it exclusively to sustainable types of consumption. Thus, there is an invitation to enjoy consumption – but only of a climate-friendly and sustainable kind while also demonstrating how fun and rewarding ‘not consuming’ can be. In this way, climate micro-influencers legitimate an alternative climate narrative going beyond promoting products.

The climate micro-influencers on Instagram are also a heterogenous type even though they have a counter-narrative in common compared to the traditional ‘influencer’ with consumption as the primary focus (Hearn and Schoenhoff Citation2016, Hou Citation2018). This counter-narrative includes guiding followers by being role models, showing how to consume sustainable products, dress fashionably in vintage outfits, eat plant-based food or live a zero-waste lifestyle. This presentation of the self focuses on the individual version of ‘commodity activism’ (Banet-Weiser and Mukherjee Citation2012) and often with a positive emotional framing. It is represented by the sustainable fashion influencer Jasmine Rogers @thatcurlytop, who consistently presents stylish ‘new outfits’ as well as vegan food products and performs her authenticity by being truthful in her self-expression. She prefers to rewear and thrift, but when she buys new products they are sustainable. Following Marwick (Citation2015), she has an honest brand engagement in the sense that she prefers sustainable fashion brands, but also admits that nobody is perfect and thus she does not present herself as judging her followers, but rather as inviting them to enjoy thrifting and have fun being creative and stylish. Another slightly different profiles for a vegan influencer with focus on food – Immy Lucas @sustainable – vegan – focuses on ‘how to’ – videos explaining and demonstrating sustainable living and gives advice on cooking vegan food that she presents at home presented in an informative and stylish way adhering to the aesthetic codes of Instagram (Serafinelli Citation2018, Manovich Citation2020). For @sustainable-vegan it is a performance of making climate-friendly living look effortlessly easy and an integral part of your everyday life. This is in contrast to macro-influencer Silverstone, who is sharing the odd recipe, but she does not make how-to videos or instruct in sustainable ‘lifehacks’. Activist micro-influencer and authors Tori Sui @torisui and Xyie Bastida @xiyebeara, focus more on the political dimensions of the issue and participate in marches and events, but they also visually document their impact as activists, e.g. by posting when they are invited to television shows and magazines. They correspond to the activist macro-influencers like Klein or Monbiot, but on a much smaller scale; they are documenting when they appear in legacy media to stress their impact: however, neither of these micro-influencers is just ‘witnessing’ or performing advocacy – like the climate macro-influencer DiCaprio. Activist-influencers are participating like Thunberg, and they are making the ‘issue’ of climate change part of their lifestyle like Silverstone. They show how it is inseparable from their everyday life and that it is something to aspire to. Through these performances, they present themselves as relatable role models and examples of KOLs (key opinion leaders) demonstrating sustainable living with easy ‘life-hacks’ ().

Figure 2. Climate micro-influencers: Screenshots of extracts from activist micro-influencers @thatcurlytopp (fashion) and @sustainably_vegan (food).

To sum up, the authenticity of climate micro-influencers lies in their consistency of lifestyle and overall focus on climate change. They become a potential alternative to the conspicuous consumption of the traditional fashion and food influencers on Instagram (Marwick Citation2015, Hund Citation2023). Their climate narrative is a regular performance closely connected to both their authenticity and lifestyle and often clearly presented through their individual profile that displays an optimistic and constructive emotional framing.

The authentic climate influencer – from macro to micro

When conceptualising the climate influencer with a focus on the distinctions between the different types of macro and micro-influencers concerned with climate change, it seems that macro-influencers such as the activist and the Hollywood actor can address climate change as inspiration and legitimiser of values and awareness and get away with not necessarily displaying a sustainable lifestyle. However, the activist macro-influencer (not including the intellectuals) makes an effort to show that their lifestyle and their fight for climate change are closely connected. Micro-influencers, by way of further contrast, can be seen as key opinion leaders because they not only promote certain sustainable products, but they also represent a relatable role model closer to home because they lead a particular vegan or zero-waste lifestyle (Haastrup Citation2022). Our investigative study of how climate celebrities understood as influencers – in the broadest conceptualisation of the term – construct and communicate climate change is an investigation of a spectrum of particular forms of social media identities such as the climate macro and micro-influencers. For instance, the politics of climate for star macro-influencers is intertwined with their careers in the entertainment industry. Their original appeal means that they are able to keep their millions of followers while engaging with climate issues, using their star image as political currency to work with NGOs as advocates of ideas and, at the same time, continue to present their star image online. However, the question is for how long will this discrepancy between addressing climate change as an issue of interest but otherwise upholding a unsustainable lifestyle be an acceptable personal narrative? And, additionally, what are the implications related to whether their professional work in the creative media industry has an impact on the environment? Contradistinctively, another group we have defined as activist macro-influencers communicate to their followers about climate change and the environment on what can be described as their issue singularity in their social media work. These activist macro-influencers have built their followers (as we have identified) through environmental activism that is clearly politically driven and very much linked to visibility on legacy media. Their impact as macro-influencers is very wide-ranging as they present their opinions in all sorts of forums: engaging in online debates, connecting with hashtag publics, appealing to the activist community (social media), posting memes featuring key messages and contributing to legacy media. This wide range of activity produces a new kind of structure for political celebrity, part of which still involves the legacy media coverage of how well they are doing on social media.

Our investigation has also identified an intriguing and collectively influential structure in and through social media of climate and environmentally driven micro-influencers. They have fewer Instagram followers, are regularly active on their accounts and integrate products and promotions with ‘how-to’ activities and activism. We have identified their complex relation to authenticity combining both congruence and ‘being true to themselves’, and the entrepreneurial motivation and alignment that is essential for many climate micro-influencers. Their issue singularity can present a paradox when promoting products at the same time as they advocate minimising consumption through zero waste and thrifting. However, they document their lifestyle and often argue that nobody is perfect, and everyone can do something – making sustainable living an option for everybody and, in some cases, also explaining why they themselves still promote consumption. Their performances of authenticity and expressions of emotion link climate change to what they consider environmentally sound products fit for use by their followers. Micro-influencers also demonstrate the importance of going beyond raising awareness and show how effortless – and even fun – a sustainable life can be by exuding a different kind of relatable authority than the Hollywood star (Haastrup Citation2023).

Conclusion

Over the last decade, the concept of the influencer has become an essential term used to articulate the political and cultural power of certain individuals by means of and via their social media activity. In this preliminary and conceptual study, we have developed three identifiable categories of climate influencers and how, through their different narratives, they circulate in the public spheres of contemporary culture and promote different agendas of climate change without intentions of seeking political office. Instead, these influencers represent a different kind of impact with their mostly positive, constructive and engaging strategies for the performance of the climate narrative on social media. Similarly, the three types of influencers we have identified are individual types of role models with personalised climate narratives: from the traditional awareness-raising and appeals to calls for engaging in debates and marches, to taking action through consuming sustainably and presenting lifestyle changes as both fun and easy. They further demonstrate a change from the traditional online climate advocacy providing information, such as the star and intellectual macro-influencer to an aspirational performance of everyday-life by the micro-influencer making sustainably living their business model. As a result, climate micro-influencers transform the abstract climate issue into a way of life and actual individual agency.

However, another important change is how the star and activist macro-influencers and the micro-influencers represent a personal counternarrative and exemplify how different types of non-experts can contribute and ‘visibly intervene in a discussion about climate change that generally takes place among expert level scientists and journalists’ (Hautea et al. Citation2021, p. 12). In contrast to the trending ‘Gloom and Doom’ videos expressing climate anxiety (Hautea et al. Citation2021, p. 7) – not to mention other widespread climate scepticism and misinformation (Falkenberg et al. Citation2022) – these macro and micro-influencers are all clearly advancing on their activism in positive and engaging ways. There is no question that any contemporary issue is subject to this complex structuration of social media connection and communication: nonetheless, we also need to make distinctions between the different implications of these positive, emotional and constructive counternarratives and discuss what we accept as authentic climate narratives by macro as well as micro-influencers. Likewise, our conceptualisation of climate influencers lays the ground for future research into followers online and off-line and what political impact these visual and personal climate role models have.

This study is the first step in categorising and making sense of how influencer culture plays into the ebbs, flows and understandings of the politics of climate change. As part of this work, we have identified the way in which forms of a personal, emotional connection and authenticity are now part of how the key political issue of climate change and the environment is performed in and across the ever-changing dimensions of contemporary celebrity as new forms of social media influence emerge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helle Kannik Haastrup

Helle Kannik Haastrup is an Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen. Her research focuses on film culture, celebrities in digital media culture and their social and cultural significance. She has published the first Danish-language introduction to that topic, Celebritykultur (Samfundslitteratur, 2020), articles in Popular Communication, Celebrity Studies and Persona Studies, and co-edited Rethinking Cultural Criticism: New Voices in the Digital Age (Palgrave MacMillan, 2021).

P. David Marshall

P. David Marshall is Emeritus Professor at Deakin University and Honorary Professor at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China. His research investigates our political, economic, cultural and celebrity public personality systems and their transformations in and through digital culture. His books include Persona Studies: An Introduction (2019), Advertising and Promotional Cultures: Case Histories (2018), Celebrity Persona Pandemic (2016), Contemporary Publics (2016), A Companion to Celebrity (2016), Celebrity and Power (2nd edition 2014) and The Celebrity Culture Reader (2006).

References

- Abidin, C., 2018. #familygoals: family influencers, calibrated amateurism, and justifying young digital labor. Social Media + Society, 3 (2), 205630511770719. doi:10.1177/2056305117707191.

- Abidin, C., et al. 2020. “The tropes of celebrity environmentalism. Annual review of environment and resources, 45 (1), 387–410. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-081703.

- Abidin, C., 2021 From “networked publics” to “refracted publics”: a companion framework for researching “below the radar” studies. Social Media & Society, [Jan-March]. 7 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1177/2056305120984458

- @aliciasilverstone (Alicia Silverstone). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/aliciasilverstone/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Banet-Weiser, S. and Mukherjee, R., 2012. Commodity activism: cultural resistance in neoliberal times. New York: NYU Press.

- Baym, N., 2018. Personal connections in the digital age. Minnesota: Polity Press.

- Boerman, S., Meijers, M., and Zwart, W., 2022. The Importance of influencer-message congruence when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environmental Communication, 16 (7), 920–941. doi:10.1080/17524032.2022.2115525.

- Boykoff, M. and Goodman, M., 2009. Conspicuous redemption? Reflections on the promises and perils of the ’celebritization’ of climate change. Geoforum: Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 40 (3), 395–406. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.04.006.

- Boykoff, M. and Goodman, M., 2022. Celebrities and Climate change. Institute for Interdisciplinary Research into the Anthropocene. Available from: https://iiraorg.com/2022/06/12/celebrities-and-climate-change/,1-23. [Accessed 26 April 2023].

- Breves, P. and Liebers, N., 2022. # greenfluencing. The impact of parasocial relationships with social media influencers on advertising effectiveness and followers’ Pro-environmental Intentions. Environmental Communication, 16 (6), 773–787. doi:10.1080/17524032.2022.2109708.

- Brockington, D., 2009. Celebrity and the Environment. London & New York: Zed Books.

- Budabin, A.C., and Richey, L.A., 2021. Batman Saves the Congo: how celebrities disrupt the politics of Development. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Chouliaraki, L., 2013. The ironic spectator. solidarity in the age of post-humantarianism. London and New York: Polity Press.

- Corner, J. and Pels, D., Eds. 2003. Media and the restyling of politics: consumerism, celebrity and cynicism. Sage Publications. doi:10.4135/9781446216804.n5.

- Doyle, J., 2016. Vegan celebrities and the lifestyling of ethical consumption. Environmental Communication, 10 (6), 777–790. doi:10.1080/17524032.2016.1205643.

- Dyer, R., 1979. Stars. London: BFI Publishing.

- @emmawatson (Emma Watson). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/emmawatson/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Enli, G., 2017. Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: exploring the social media campaigns of trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. European journal of communication, 32 (1), 50–61. doi:10.1177/0267323116682802.

- Falkenberg, M., et al. 2022. Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nature Climate Change, 12 (12), 1114–1121. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01527-x.

- @GeorgeMonbiot (George Monbiot). Available from: https://twitter.com/GeorgeMonbiot [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Goodman, K., et al. 2016. Spectacular environmentalisms: media, knowledge and the framing of ecological politics. Environmental Communication, 10 (6), 677–688 . doi:10.1080/17524032.2016.1219489.

- Goodman, M., Doyle, J., and Farrell, N. 2022. Celebrities and Climate change. Available from: https://iiraorg.com/2022/06/12/celebrities-and-climate-change/ [12 June 2022].

- Goodman, K. and Littler, J., 2013. Celebrity ecologies: introduction. Celebrity Studies Journal, 4 (3), 269–275. doi:10.1080/19392397.2013.831623.

- @gretathunberg (Greta Thunberg). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/gretathunberg/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Haastrup, H.K., 2018. Hermione’s feminist book club: celebrity activism and cultural critique. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 34 (65), 98–116. doi:10.7146/mediekultur.v34i65.104842.

- Haastrup, H.K., 2022. Personalising climate change on Instagram: self-presentation, authenticity, and emotion. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 38 (72), 065–085. doi:10.7146/mk.v38i72.129149.

- Haastrup, H.K., 2023. Having fun saving the climate: the climate influencer, emotional labour and–storytelling as counter-narrative on TikTok. Persona Studies, 9 (1), 36–51. doi:10.21153/psj2023vol9no1art1884.

- Hammond, P., 2017. Climate change and post-political communication: media, emotion and environmental advocacy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315772592.

- Hautea, S., et al. 2021 Showing they care (or don’t): affective publics and ambivalent climate activism on TikTok. Social Media + Society, [April-June]. 7 (2), 1–14. doi:10.1177/20563051211012344

- Hearn, A., 2012. Brand, Culture, Action. In: S. Banet-Weiser, and R. Mukherjee, eds. Commobity activism: cultural resistance in neoliberal times. New York: New York University Press.

- Hearn, A. and Schoenhoff, S., 2016. From celebrity to influencer: tracing the diffusion of celebrity value across the data stream. In: P.D. Marshall and S. Redmond, eds. A Companion to Celebrity. John Wiley & Sons, 194–212. doi:10.1002/9781118475089.

- Heckerling, A., et al., 1995. Clueless. USA: Paramount.

- Horton, D. and Wohl, R.R., 1956. Mass communication and para-social interaction. observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19 (3). Published online: 8 Nov 2016, pp. 215–229. doi:10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

- Hou, M., 2018. Social media celebrity and the institutionalization of YouTube. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25 (3), 534–553. doi:10.1177/1354856517750368.

- Hund, E., 2023. The influencer industry. the quest for authenticity on social media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hurley, Z., 2019 Imagined affordances of Instagram and the fantastical authenticity of female Gulf-Arab social media influencers. Social Media + Society, [January-March]. 5 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1177/2056305118819241

- Jin, M., et al. 2021. Uncertain KOL selection with multiple constraints in advertising promotion. IEEE access, 9, 142869–142878. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3121518

- Katz, E. and Lazarsfeld, P.F., 1955. Personal influence: the part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Glencoe, Ill: The Free Press.

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., and Parkinson, J., 2020. When less is more: The impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management, 36 (3–4), 248–278. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2020.1718740.

- @leonardodicaprio (Leonardo DiCaprio). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/leonardodicaprio/?hl=da [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Liu, M., Zhao, R., and Feng, J., 2022. Gender performances on social media: a comparative study of three top key opinion leaders in China. Frontiers of Psychology, 13, 1046887. 1–11. 2022 Nov 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046887

- @luisaneubauer (Luisa Neubauer). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/luisaneubauer/?hl=da [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Luqiu, L.R., Schmierbach, M., and Ng, Y., 2019. Willingness to follow opinion leaders: a case study of Chinese Weibo. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.005

- Maares, P., Banjac, S., and Hanusch, F., 2021. The labour of visual authenticity on social media: exploring producers’ and audiences’ perceptions on Instagram. Poetics, 84, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101502

- Manovich, L., 2020. The aesthetic society. In: P. Mörtenboeck and H. Mooshammer, eds. Data Publics. London & New York: Routledge, 192–212.

- Marshall, P.D., 2010. The promotion and presentation of the self. Celebrity Studies Journal, 1 (1), 35–48. doi:10.1080/19392390903519057.

- Marshall, P.D., 2014( 1997). Celebrity and power: fame in contemporary culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Marshall, P.D., 2020. Celebrity, politics, and new media: an essay on the implications of pandemic fame and persona. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 33 (1), 89–104. doi:10.1007/s10767-018-9311-0.

- Marshall, P.D., 2022. Correlating affect and emotion: covidiquette and the expanding curation of online persona(s). Thesis Eleven, 169 (1), 8–25. doi:10.1177/07255136211069170.

- Marwick, A.E., 2013. “They’re really profound women, they’re entrepreneurs”: conceptions of authenticity in fashion blogging [ Conference presentation]. International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Cambridge, MA, United States (July 8-11), 1–8.

- Marwick, A.E., 2015. Instafame: luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture, 27 (1), 137–160. doi:10.1215/08992363-2798379.

- Marwick, A.E. and Boyd, D., 2010. I tweet honestly, i tweet passionately: twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13 (1), 114–133. 7 July. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313.

- Massumi, B., 2015. Politics of affect. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- McCurdy, P., 2013. Conceptualising celebrity activists: the case of Tamsin Omond. Celebrity Studies, 4 (3), 311–324. doi:10.1080/19392397.2013.831627.

- Mullen, J., 2010. Lifestreaming as a Life Design Methodology. Thesis (MA). https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/fb84cbd1-6669-4304-b10d-faa3f82b3c1e

- Murphy, P., 2021. Speaking for the youth, speaking for the planet: Greta Thunberg and the representational politics of eco-celebrity. Popular Communication, 19 (3), 193–206. doi:10.1080/15405702.2021.1913493.

- @NaomiAKlein (Naomi Klein). Available from: https://twitter.com/NaomiAKlein/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Poell, T., Nieborg, D., and Duffy, B.E., 2022. Platform and Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Robeers, T. and Van Den Bulck, H., 2019. Hypocritical investor’ or Hollywood ‘do-gooder’? A framing analysis of media and audiences negotiating Leonardo DiCapri’s ‘green’ persona through his involvement in Formula E. Celebrity Studies Journal, 12 (3), 444–459. doi:10.1080/19392397.2019.1656537.

- Rojek, C., 2001. Celebrity. New York: Reaktion Books.

- Schmuck, D., 2021. Social media influencers and environmental communication. In: B. Takahashi, J. Metag, J. Thaker, and S.E. Comfort, eds. The handbook of international trends in environmental communication. London: Routledge, 373–387. doi:10.4324/9780367275204.

- Senft, T., 2008. Camgirls–celebrity and community in the age of social networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Serafinelli, E., 2018. Digital life on Instagram: new social communication of photography. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Sjögren, O., 2022. Ecological Wunderkind and heroic trollhunter: the celebrity saga of Greta Thunberg. Celebrity Studies Journal, 14 (4), 472–484. doi:10.1080/19392397.2022.2095923.

- Stacey, J., 1994. Stargazing. London: Routledge.

- Street, J., 2004. The celebrity politician: Political style and popular culture. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 6 (4), 435–452. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00149.x.

- @sustainably_vegan (Immy Lucas). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/sustainably_vegan/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- @thatcurlytop (Jasmine Rogers). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/thatcurlytop/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- @torisui (Torit Sui). Available from https://www.instagram.com/toritsui_/?hl=en Accessed 16 January 2024

- Van Driel, L. and Dumitrica, D., 2021. Selling brands while staying “authentic”: the professionalization of Instagram influencers. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27 (1), 66–84. doi:10.1177/1354856520902136.

- van Zoonen, L., 2005. Entertaining the Citizen. When Politics and Popular Culture Converge. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers.

- Warner, H., 2013. Fashion, celebrity and cultural workers: SJP as cultural intermediary. Media, Culture & Society, 35 (3), 382–391. doi:10.1177/0163443712471781.

- Welsh, D., 2002. Luxury Gets More Affordable. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2002-04-21/luxury-gets-more-affordable

- Wheeler, M., 2013. Celebrity Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- @xiyebeara (Xiye Bastida). Available from: https://www.instagram.com/xiyebeara/ [Accessed 16 January 2024].

- Yin, R.K., 2009. Case study research: design and methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.