ABSTRACT

This study analyses and explains how the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) acquired and retains monopoly and monopsony power over Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) in a complex political, legal, regulatory, and financial context. A qualitative and interpretive approach to research underpins a thematic analysis of social media and journalistic content alongside a review of a limited academic literature. It is found that the UFC has acquired and retained monopoly and monopsony power in a context of weak regulation, limited competition, ineffective legal and political intervention, and an absence of unionisation. The three key strategies employed by the UFC to sustain power over MMA were found to be 1. control of athlete labour via restrictive contracts; 2. acquisition of competitor promotions, expertise, and commercial contracts; and 3. building reputation and legitimacy via public relations and lobbying activities. The UFC has employed a combination of legitimate, referent, reward, expert, informational, and coercive power to become the dominant organisation in MMA.

Introduction

This study analyses and explains how the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) obtained monopoly and monopsony power over Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) in a complex legal, regulatory, political, and financial context. The three key strategies employed by the UFC to acquire and sustain power over MMA were found to be 1. control of athlete labour via restrictive contracts; 2. acquisition of competitor promotions, expertise, and commercial contracts: and 3. building reputation and legitimacy via public relations and lobbying activities. To analyse the strategic action of the UFC, this study identifies six forms of empirical power as described by French and Raven (in Cartwright,1959, cited in Kovach Citation2020). These ‘crystallizations’ of power include legitimate power (authority, status, and prestige); referent power (the power of charismatic leadership for example); reward power (such as control over athlete contracts, wages, and bonuses); expert power (business acumen and legal expertise); informational power (control over access to information); and coercive power (such as the use of sanctions).

The work of Etzioni (Citation1975, cited in Mullins and Rees, Citation2023) on organisational power is also instructive in understanding how the UFC acquired and sustains control of MMA in the USA via remunerative (reward) and normative (legitimate) forms of power given the calculative involvement and attachment to the UFC by athletes. Further, this study utilises the insights on ‘hard’, ‘soft’ and ‘smart’ power as identified by Nye (Citation2005, Citation2011) where ‘hard’ power can be equated with coercive power and ‘soft’ power with the other forms cited in Kovach (Citation2020). Smart’ power combines coercive power with ‘soft’ forms of power.

In practice, the UFC can combine these forms or ‘crystallisations’ of power to mobilise resources, build partnerships, and create bargaining power or leverage, for competitive advantage. Power is therefore theorised as resource based where monopoly power is defined as ‘the power to control prices or exclude competition’ (Nash Citation2021) and monopsony power is defined as ‘having market power in the purchase of a product or service’ such as labour (Nash Citation2021). The study highlights how the UFC acquired its power through strategic action in a context of limited competition, ineffective unionisation, relatively weak legal and regulatory oversight, and increasing levels of political, media and commercial support.

Literature review

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) is a combat sport that combines the rules and practices of several martial arts. In the 1990s, tournaments were held with minimal rules and were characterised by violent conduct that resulted in political and public pressure to ban the sport (Hill Citation2013). Political opposition was notable from senator John McCain who labelled the sport ‘human cockfighting’ (Greene Citation2018). The sport was subsequently banned in 36 US states (Graham Citation2016). This in turn led to business underperformance and promoters facing bankruptcy. However, the image and reputation of the sport has changed in recent years, with a set of standardised and unified rules being introduced in 2009 and political support increasing during Donald Trump’s term in office (2017–21) when the UFC became the sports arm of his ‘MAGA’ regime (Zidan Citation2020). Today, modifications to MMA have allowed the sport to be approved in 47 US states by regulatory bodies such as Athletic Commissions and is allowed without a regulatory body in two states, with the sport eventually allowed in New York state following a legal case (Cruz Citation2020).

In the context of an economic decline in the late 1990s and early 2000s, described as the ‘dark ages’ for the sport (Hess Citation2007), the critical event leading to MMA reaching the mainstream, and the catalyst for the rapid growth of the UFC as the lead promoter, was the acquisition of the UFC, for $2 million in 2001 by Station Casinos executives Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta (operating as Zuffa). By 2016, a business conglomerate (re-named Endeavor in 2017) acquired the UFC for $4 billion. This was the largest acquisition in the history of sports entertainment. Today, the sport is a multi-million-dollar industry with the UFC generating over a billion dollars a year (Nash Citation2022a) and being by far the largest organiser and promoter of MMA events in the USA, whilst having global reach in terms of audience and political influence. The UFC has acquired political influence in Saudi Arabia (Zidan Citation2023b) and the UAE where events have been organised (Zidan Citation2019, Butryn and Masucci Citation2020). Further, the UFC has links to Chechnya (Zidan Citation2023c) but its primary power base is the USA and to a lesser extent, Canada.

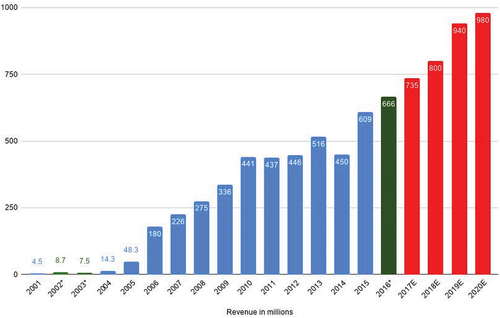

highlights the UFC revenue growth from 2001 to 20 in $US dollars. Although there are many MMA organisations worldwide, most notably in the USA, including the UFC, Bellator, PFL (Professional Fighters League) and Invicta, and outside of the USA, Cage Warriors (UK), One Championship (Singapore), Rizin and Pancrase (Japan) and equivalent bodies in Russia including the influential Absolute Championship Berkut (ACB) in Chechnya, the UFC have 80% share of the Eastern hemisphere market, and 90% market share in the USA (Nash Citation2021b). By comparison, other promoters have problematic financial prospects. For example, in 2014, rival promoter Bellator had its best year for generating revenue but this was one-tenth of the UFC’s revenue in the same time period (Nash Citation2020a) and in late 2023, PFL acquired Bellator. Another competitor, One Championship, generated losses pre-pandemic of $229 million, despite having significant investors (Nash Citation2021a). More recent financial data indicates a trajectory of increasing revenue generation by the UFC, especially since the parent organisation, Endeavour, procured World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) in April 2023 with a 51% controlling stake in a $21bn deal.

A key factor to explain the financial dominance of MMA by the UFC includes a broadcasting contract with FOX, and latterly ESPN. The FOX contract was a 5-year deal worth $1.5 billion (Anon Citation2018). Also of note is that the deal generated almost twice as much as the two major broadcasting deals in boxing (Nash Citation2016). Moreover, the UFC has major TV deals outside the USA that are beneficial for maintaining their monopoly. These deals include those with BT Sport in the UK, Canal + in France, Setanta Sports in Ukraine, and the UFC ‘Fight Pass’ being available worldwide. Being shown on major TV networks allows the UFC to expand their consumer base through increasing publicity, furthering their reputation as the premier MMA organisation. Ticket sales for live UFC events and Pay-Per-View (PPV) sales are higher than competitors and all the ‘top’ fighters are under contract with the UFC, reducing market competition. Also, the UFC regularly generates more revenue and sells more Pay-Per-Views per annum than boxing (Nash Citation2016). The UFC generates revenue from sources that boxing promoters do not, including video games, merchandise, and gyms. Additionally, in 2014, the UFC reached a 6-year $70 million exclusive attire (uniform) agreement with Reebok (Nag Citation2021), and more recently a three-year deal with Venum (Bissel Citation2021). Rival organisations do have TV deals with mainstream broadcasting companies, such as Bellator with Showtime (Segura Citation2021) and the BBC (Fry Citation2023), and One Championship with Amazon Prime (Atkin and Taylor Citation2022). However, this indicates a growth in the market for MMA rather than competition that might challenge the market dominance of the UFC.

Finally, in relation to the financial context, the UFC has created and retained monopoly status through purchasing competitor organisations. The UFC has bought out several notable organisationsfor example, Pride FC, the WEC (World Extreme Cagefighting) and Strikeforce (Harty Citation2014). The purchasing of competitors allowed the UFC to attain notable fighters who were fighting for rival promoters, as well as removing competition. This created a further sense that the UFC are the premier organisation with the best fighters, including the number one ranked fighter in all weight divisions (Nash Citation2021b). Because the rival organisations generally cannot facilitate fights with the top-ranked fighters, public interest is lower. To further compound the power of the UFC and its parent company, the procurement of WWE, as stated, is expected to increase the monopoly and monopsony power of the UFC in both MMA and professional wrestling. A timeline of UFC financial power acquisition is summarised in .

Table 1. Timeline of UFC financial power acquisition.

Central to the literature on MMA in the USA is the Sherman Anti-Trust Act that is intended to stop unreasonable restraints of trade (Cruz Citation2018, Citation2020, Milas Citation2022). Currently, there are two anti-trust lawsuits (2010–17 and 2017 to date) being taken against the former owners of the largest promoters in MMA, Zuffa, who owned the UFC until its sale to the Endeavour group. In December 2014, a group of then-current and former UFC fighters sued the promotion in a class-action lawsuit under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. They alleged that the UFC operated an anti-competitive scheme to maintain and enhance monopoly power in the market for elite, professional MMA fighter bouts and monopsony power in the market for elite, professional MMA fighter services (Gift Citation2014, Citation2022a). The legal cases centre on whether fighters contracted by the UFC were underpaid, since they received a relatively small percentage of the revenue generated by the UFC compared to other sports (Tabuena Citation2022). Fighters claimed the UFC raised rival MMA promoter costs by restricting access to critical inputs, such as the fighters themselves, the best venues, valuable sponsorships, and television networks, thereby suppressing fighter compensation (wages) (Critchfield Citation2014, Gift Citation2020). The damages being sought range from approximately $811 million to $1.6 billion (Nash Citation2020b).

The second anti-trust lawsuit taken by former UFC fighters, relates to the period 2017 to date. The lawsuit claims that the owners engaged in anticompetitive practices, such as long-term exclusive contracts and abusing their market dominance (Montague Citation2021). The only difference between the two lawsuits is the time frame. If successful, this lawsuit could add an estimated $1 billion of damages onto the potential $1.6 billion for the earlier anti-trust lawsuit (Tabuena Citation2021a). Additionally, losing the lawsuit would likely result in amendments to the UFC’s business model. In response, the UFC have modified contract lengths to protect themselves from further legal proceedings. Fighters are now required to have any disputes arbitrated rather than initiating legal action (Tabuena and Nash Citation2023). Nash (Citation2021b) anticipates a settlement prior to the completion of the two lawsuits that may take years to resolve.

It is important to note that MMA is not regulated at the federal level unlike boxing has been, since the introduction of the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act (enacted in the year 2000) or ‘Ali Act’. Briefly, the Ali Act is a federal law that protects the rights of boxers by limiting the restrictions in contractual arrangements. Although there has been Federal level interest in extending the Ali Act to cover all combat sports, this has not been realised to date (Dunn Citation2022). Due to the UFC’s lobbying against the Ali Act and UFC president Dana White’s friendship with former US President Donald Trump, the act was vetoed in 2017 (Athanur Citation2022). However, there were plans to introduce the Ali Act with a change of US President (Evanoff Citation2022). Savage (Citation2016) observes that the Department of Justice or the US Attorneys, who are tasked with upholding the provisions of the law, have not been enforcing the law in boxing. Moreover, enforcement of federal law at the state levels remains problematic (Varney Citation2009). Nash (Citation2017a) observes that if the Ali Act was introduced into MMA, the UFC would have to modify its business model which may explain the UFC’s resistance to the integration of the act into MMA. To summarise, the Ali Act expansion may change the power dynamics within MMA for the benefit of the fighters (Gross, Citation2016a).

Another key political development in MMA in recent years has been attempts at unionisation. Unionisation may be the most accessible method for the improvement of workers’ rights within combat sports, and desire for a union has intensified within the MMA community (Birren and Schmitt Citation2017, Mullen Citation2018, Ansari Citation2022). Currently there are three bodies representing MMA fighters in the USA. These are the Professional Fighters Association (PFA) formed in 2016 and not administered by fighters and the Mixed Martial Arts Athlete Association (MMAAA) formed in 2016 and Project Spearhead in 2018, both operated by fighters and ex-fighters. The PFA focused entirely on a union for the UFC (Tabuena Citation2016), whereas the MMAAA and Project Spearhead aim to unionise the whole of MMA. The MMAAA had ‘head-line worthy’ fighters advocating for unionisation for the first time (Gross, Citation2016a), as well as being supported by a former owner of rival promoter, Bellator (Al-Shatti Citation2022). However, relatively few fighters are members, so collective bargaining power is weak. In response, Project Spearhead aims to secure support of 30% of contracted UFC fighters to acquire enough collective bargaining power to challenge the UFC (Raimondi Citation2018). Critically, 30% is needed to trigger a review by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to determine if fighters are employees or independent contractors (Nash Citation2018a). If the NLRB deem the fighters to be employees of the UFC, the power to authorise a union would be established. The advantages of employee status would likely be to impact contracts between fighters and the UFC (Aris Citation2013) and result in modifications to the UFC business model.

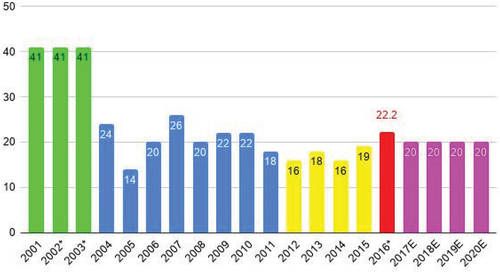

The central issue is therefore whether fighters are classified as independent contractors or employees (Conklin Citation2020). Although it has been claimed that if athletes supported a union, it would create a ‘ripple effect’ for the entire sport (Duncan Citation2020), Nash (Citation2022b) argues that unionisation may not benefit independent contractors such as MMA fighters, and an association may be a more effective means to secure fighter benefits. On the other hand, although associations can enact lawsuits, they cannot collectively bargain or strike, unlike a union. Nash (Citation2022b) adds that despite drawbacks, legislation may be more protective of fighters’ rights than a union, assuming the law is enforced. It can be noted that unionisation is a feature of other sports in the USA, where athletes receive a greater share of the revenue generated by the sport. The UFC has typically paid 20% of its revenue in wages, similar to WWE prior to the merger with UFC, and post-merger, fighter pay has decreased (Pekios Citation2023). This can be compared to almost 50% of revenue paid in wages in unionised sports such as American Football, Baseball, Basketball and Ice Hockey (Conway Citation2022). However, combat sports such as boxing are similar to MMA in lacking unionisation.

Methodology

The methodological approach to the research is qualitative (Devine Citation1995, Sparkes and Smith Citation2014). Qualitative research is used to acquire ‘rich data’ by exploring the perspectives of those within the sport, and specifically those observing power relations within MMA. This study therefore aims to increase understanding of how the UFC acquired and sustains its control of MMA through an analysis of the strategic action of the organisation within a specific context. The primary method used in this study is an analysis of media content (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014) supported by a review of the literature, albeit limited in scope. ‘Content analysis is a generic name for a family of analytical methods that aim to systemise, reduce and interrogate the content of data by … coding and identifying themes … at a manifest and latent level’ (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014, p. 116). This study examines the types or ‘crystallisations’ of power deployed by the UFC. The types and examples of power are coded and classified as ‘legitimate’, ‘referent’, ‘reward’, ‘expert’, ‘informational’, and ‘coercive’ using French and Raven’s terminology (Kovach Citation2020). Individuals with the required expertise to answer questions regarding power-relations in MMA have expressed their insights openly and candidly in the public domain via social media and in newspaper and magazine articles. Identified ‘experts’ cited in this study have published books, journal articles, and articles available in the media that serve to answer the research question and interviews may not have added anything new.

This research takes a step-by-step approach to analysing media content (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014, p. 118; ). This is a similar process to a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2021).

Table 2. Research process.

Stage 1 is ‘immersion’, where many media sources are accessed to become familiar with the politics and governance of MMA specifically in the USA. The sources used are newspapers, magazines, books, social media sources, and published literature in academic journals. Stage 2 is a search for patterns in the data using coding and stage 3 groups discovered patterns into broader themes. The themes that emerged relate to the threefold strategy employed by the UFC (). Stage 4 is to cross-check the data to avoid potential bias of excluding data that does not fit with prior observations. Stage 5 in this study is to create a table that summarise the key findings. From the findings, examples of the types of power used by the UFC can be highlighted ().

Table 3. UFC strategies (codes and themes).

Table 4. Forms of power employed by the UFC.

The advantage of analysing and interpreting media content is the availability and ease of accessibility. When combined with a review of the published literature, a content analysis can offer insights that can be valuable to comprehending power relations in MMA. The media sources accessed to perform the content analysis are cited as Appendix 1. Although ethical issues regarding consent to participate in the study, anonymity of informants and confidentiality of data are mediated by employing a content analysis of media sources, the subjectivity of those supplying media content should be accounted for. Therefore, the scope for generalisability is to some extent limited (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014). Research limitations also include the minimal resources available to undertake the study, such as time, finance and access to relevant data, including confidential fighter contacts and some commercial data.

Theories of power

To analyse power-relations in MMA and specifically the strategic action of the UFC, the empirical study recognises the six forms or ‘crystallizations’ of power as described by French and Raven (Citation1959), cited in Kovach (Citation2020). These are legitimate power (authority, status, and prestige); referent power (the power of charismatic leadership for example); reward power (such as control over athlete contracts, wages, and bonuses); expert power (business acumen and legal expertise); informational power (control over access to information); and coercive power (such as the use of sanctions). ‘Coercive power’ is equated with ‘hard power’ defined as ‘the ability to get others to act in ways that are contrary to their initial preferences and strategies’ (Nye Citation2011, p. 11). Apart from coercive power, the other five forms of power utilised in this study can be defined as ‘soft power’ (Nye Citation2005). ‘soft power’ is defined as the ability to get ‘others to want the outcomes that you want’ (Nye Citation2005, p. 5). The employment of both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power is defined by Nye (Citation2005) as ‘smart power’. The work of Etzioni (Citation1975, cited in Mullins and Rees, Citation2023) on organisational power is also instructive in understanding how the UFC acquired and sustains control of MMA in the USA via remunerative (reward) and normative (legitimate) forms of power given the calculative involvement and attachment to the UFC by athletes. It is acknowledged that there is a methodological and empirical challenge in clearly demarcating between different forms of power.

Ostensibly, ‘power’ itself is theorised as resource based where monopoly power is defined as ‘the power to control prices or exclude competition’ (Nash Citation2021) and monopsony power is defined as ‘having market power in the purchase of a product or service’ (Nash Citation2021). Pluralists (Smith, in Marsh and Stoker Citation1995, pp. 209–227) assume that power is dispersed between competing interest groups, or those with a common interest or objective. The dispersal of power therefore emerges from bargaining between interest groups. By contrast, elite theory is a school of thought in which power is centralised (Evans, in Marsh and Stoker Citation1995, pp. 228–247). Consequently, interest groups differ in their resources and capacity to mobilise resources. It is therefore argued that power is unequally distributed among competing groups, and some groups may be resource dependent on others. A neo-Marxist analysis of power (Taylor, in Marsh and Stoker Citation1995, pp. 248–267) focuses on power as embedded into the structure of society to favour dominant interests that control capital and labour (also see Lowndes et al. Citation2017).

In a capitalist society and economy such as the USA, there is an attempt by the government to regulate monopoly and monopsony power, ensuring power is dispersed widely in a democratic society. In this scenario, legal and regulatory bodies have a critical role in managing conflict between competing groups. However, the state can be captured by corporate interests. Preliminary research into power in MMA would suggest that the UFC has significant monopoly and monopsony power where power is not widely dispersed and regulatory oversight is minimal.

In practice, the UFC can combine the types of power identified by Kovach (Citation2020) to extend monopoly and monopsony power given that the organisation has a capacity to mobilise resources, build partnerships, and conduct effective lobbying activities, for example, to magnify its bargaining power. Kidd et al. (Citation2010) draws on Lukes’ (1974) theory of power in suggesting that the most effective use of power is to influence the perspectives and decisions of others, in this case to shape the narrative around MMA, without the need for conflict or coercion. This insight is consistent with the concept of ‘soft power’. Preliminary research would suggest that the UFC controls the narrative around MMA and has significant legitimate power. These interpretations of ‘power’ will be related to the findings of this study.

Findings

From a review of the published literature (Hill Citation2013, Gross Citation2016a,Citationb, Birren and Schmitt Citation2017, Cruz Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2020, Reams and Shapiro Citation2017, Gift Citation2019, Yiu et al. Citation2020, Walters and Heine Citation2021, Caves et al. Citation2022) and a content analysis of media sources (Nash Citation2017a,Citationb, Citation2018a,Citationb, Citation2020a,Citationb, Raimondi Citation2018, Zidan Citation2022a,Citationb, Citation2023a,Citationb,Citationc), the three key strategies used by the UFC to acquire monopoly and monopsony power were found to be: 1. control of athletes via restrictive contracts; 2. acquisition of competitor promotions, athletes, expertise, and commercial contracts; and 3. public relations and lobbying activities to build reputation and legitimacy. summarises the key findings.

Restrictive contractual arrangements

Control over athlete contracts has arguably been central to UFC strategy to maximise monopoly and monopsony power. Research by Nash (Citation2022c) highlights that athletes have limited bargaining power given that contract terms include fixed terms of service with certain conditions that favour the UFC. For example, although athlete contracts automatically terminate after a fixed period without legal consequence (the ‘sunset clause’), in practice, the UFC can allow a contract to expire without fulfilling its obligations to the athlete such as offering a minimal number of ‘pay days’. Opportunities for a fighter may therefore be withdrawn if the athlete is not viewed as compliant with the UFC’s practices. This has proven to be an issue for fighters unhappy with UFC practices, but their legal obligations remained for a five-year duration until recently when contract duration was reduced to 3 years. However, it remains problematic for an athlete to exit a ‘restrictive’ contract and take their services to another promoter, because the UFC is the recognised promoter in MMA and the sanctioning body for recognised titles.

Additionally, due to a lack of effective unionisation, as is the case with other combat sports such as boxing, there has been little or no collective bargaining by the athletes. Cruz (Citation2020) and Nash (Citation2022b) conclude that an association of fighters would be more beneficial than a union and the fact that MMA is not a team sport may be a factor undermining efforts at collective bargaining. Other issues found in the content analysis include ‘fighter wage’ which is relatively low in relation to revenue generated, by comparison with unionised sports, apart from a few fighters (Gift Citation2019). In terms of control of fighters, Gift (Citation2022b) notes that the wage share of UFC fighters has been steady, at approximately 20% of promotional revenues generated by events for 11 years consecutively, despite the rapid revenue growth of the sport (Gift Citation2022c). highlights fighter wage share of UFC revenue from 2001 to 20, respectively.

Moreover, athletes do not have opportunities to seek personal sponsorship and ‘fighter welfare’ is compromised by a lack of medical insurance despite the risk of brain injury (Mahjouri Citation2021). As athletes are ‘independent contractors’ rather than employees, they do not qualify for the entitlements that employees can claim. Arguably, the UFC are motivated to oppose unionisation to increase profits and control. Baldwin (Citation2018) noted that support for Project Spearhead among athletes decreased after ex-professionals were released from their contracts due to support for unionisation, despite authorisation cards being anonymous. One of the PFA owners, Jeff Borris, concluded that fighters are fearful of the UFC (Courtney Citation2016), and this may be the reason why unionisation has not progressed with any momentum. Although the legality of the status of fighters under contract with the UFC is questionable where athletes are required to wear uniforms promoting a UFC sponsor and are subject to anti-doping testing as though they are employees (Fowlkes Citation2017), existing contractual arrangements clearly favour the UFC. Moreover, athletes cannot take legal action against the UFC but must seek arbitration under recent changes to contractual arrangements. Dundas (Citation2020) concludes that the UFC hold a monopoly of power over fighters under contract.

Additionally, low-paid fighters have limited means to take individual legal action against a powerful organisation such as the UFC. From the UFC’s perspective, the incentive to re-sign fighters who openly criticise the UFC’s business model is low, since lower ranked and younger fighters are generally not major revenue earners. Contract termination is a major deterrent for fighters who are yet to make significant monetary gains in their career (Nash Citation2021) and therefore are resource dependent on the UFC. Further, the incentive for the highest paid MMA fighters to be critical of their employer is low. Arguably, for the balance of power between fighters and the UFC to change, the most influential fighters would be required to lead collective action.

It can also be noted that the UFC does not only determine contracts with the top fighters, but it is the sanctioning body that creates the titles for which the fighters compete. In practice, the fighters under contract legitimise a title and its sanctioning body by competing for the UFC and not alternative promoters. Since the UFC titles are regarded in higher esteem to those of competitors, it increases the athlete incentive to join the UFC. It can be claimed therefore that the UFC are efficient at legitimising and monetising their assets and the fighters are the key assets. To summarise, subduing unionisation attempts has been critical for the UFC in retaining its control of MMA and, in effect, the UFC has created a monopoly to award titles to fighters under contract.

Looking to the future, it can also be noted that MMA is a relatively new sport and in other sports, unionisation took time to develop. The ongoing Anti-trust lawsuits challenged prior contractual arrangements of the UFC, leading to recent changes to avoid further legal action. Specifically, the 2014 lawsuit claims that ‘the UFC engaged in an illegal scheme to eliminate competition from would-be rival MMA promoters by systematically preventing them from gaining access to resources critical to MMA promotions by imposing UFC fighters’ ability to fight for would-be rivals’ (Gavia Citation2022). This was done by ‘paying fighters a fraction of what they would make in a competitive market’ (Gift Citation2019, Citation2022b, Gavia Citation2022). The lawsuits are currently ongoing.

Resource acquisition

Nash (Citation2021b) notes that the UFC has three distinct competitive advantages over rival promoters. First, the UFC was the ‘first mover’ in an emerging market for MMA. Perhaps the most significant development in the gaining of resources was the UFC purchase of Pride FC in 2007. Pride collapsed following match-fixing allegations given the involvement of gambling syndicates associated with a ‘mafia’. Second, the UFC brand is embedded into MMA, with the highest audience and commercial value. Third, its human resources (the athletes) are ‘locked in’ to the UFC business model, following acquisition of rival promoters and their athletes. Barriers to entry are therefore established, reducing market competition.

Nash (Citation2019a, Citation2020b, Citation2021c) notes the financial prospects for rival promoters to the UFC are poor, given the UFC’s monopoly power. The main competitor, Bellator, until its recent procurement by PFL, generated one-tenth of the revenue of the UFC, and despite attaining notable fighters, had a relatively small customer base. By comparison, the UFC are financially robust to an extent where the ongoing lawsuits are unlikely to impact significantly on the UFC’s business model (Nash Citation2020b). The UFC not only purchases rival promotions and their athletes but actively seeks and signs athletes working for rival promotions via the ‘Looking for a Fight’ initiative led by UFC President, Dana White (Hannoun Citation2022). As noted, the UFC has successfully acquired rival promoters and in April 2023 its parent company, Endeavor, purchased WWE, itself a monopoly in professional wrestling. As noted by Nash (Citation2019b), both the UFC and WWE prior to the merger generated 70% of their revenue through media rights. The new company named TKO can in effect set the price to view MMA in a market they monopolise. In effect, rival promoters are resource dependent on the UFC, given its extensive network of influence over MMA. Furthermore, The UFC dominates the narrative around MMA on social media, notably Instagram and TikTok (Tabuena Citation2021b).

To maintain power, a dominant interest group with monopoly power can exclude others from entry into a market or decision-making processes (Kaplow Citation1985). The UFC is not a pure monopoly, but it has market dominance (Geisst Citation2000). In practice, the UFC has acquired both vertical integration and horizontal integration. Vertical integration refers to taking ownership of the production process and horizontal integration includes acquisition of competitors. The UFC is not only the primary seller as the leading promoter in MMA but is also the primary buyer of labour (the athletes).

Building reputation and legitimacy

Over time, the UFC (within its parent company, Endeavor) has built a network of powerful individuals with high expertise. For example, former president Donald Trump has a long association with combat sports, notably professional wrestling and MMA; the Director of Endeavor, Ari Emmanuel, has extensive network of political and sports entertainment contacts; and the newly formed merger of WWE and the UFC includes Board members Dana White (UFC President) and Vince McMahon who was instrumental in building the WWE monopoly before his resignation in 2024. Furthermore, the Fertita brothers’ gambling empire originally bought the UFC and secured close partnerships with senior personnel within the regulatory bodies for sports. For example, the hiring of Mark Ratner, the former executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission. The strategy was to build legitimacy and minimise opposition to the sport. Over time the UFC have acquired the elite athletes as well as agents, managers, and others into the UFC, working in partnership with powerful stakeholders such as sponsors and broadcasters.

Given the extent of their financial and political influence, the UFC is in a strong bargaining position. This is demonstrated in the successful lobbying against the introduction of the Ali Act into MMA. Cruz (Citation2019) does not anticipate that the Ali Act, if introduced into MMA, will impact significantly on the power of the UFC and notes that in boxing ‘promoters find ways around the legislation’. Also, the introduction of the Ali Act into MMA lacks support in Congress, in both political parties. Cruz (Citation2019) concluded that any change to the governance of MMA via legal and regulatory means is likely to be incremental, as it was in boxing. However, the Ali Act, if introduced into MMA, would reduce the power that promoters have over athlete contracts, explaining the opposition from the UFC.

Furthermore, the Ali Act separates promoters from sanctioning bodies. The Ali Act addressed issues such as conflicts of interest where promoters have little ‘professional distance’ between themselves and managers or agents in their responsibilities for athletes. In the case of the UFC, it is both the promoter and the sanctioning body. Moreover, the regulatory bodies at State level (Athlete Commissions) have little incentive to enforce federal law as there is no ‘clear blue water’ between the Athlete Commissions and the sanctioning bodies (Haynes Citation2021). Without a federal level commission to oversee the state commissions, enforcement is problematic. In practice the Ali Act has not been fully enforced in boxing and this may be the case for MMA should legal and regulatory controls over the sport increase. Whilst the UFC is subject to antitrust legislation, its enforcement in the case of MMA has proven ineffective to date, pending the ongoing legal case.

By gaining and extending political influence, the UFC has built their capacity to resist regulatory controls and by doing so, increase their autonomy. For example, Athletic Commissions are hesitant to sanction promotions due to local political support for events that raise taxation to support local economies. Also, there was arguably minimal ‘political distance’ between the UFC and the Athletic Commissions in respect of doping infringements until the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) gained responsibility for enforcing doping regulations in MMA (Battison Citation2023). Nonetheless, athletes who have been banned from the sport by USADA have returned to claim UFC titles. The lobbying power of the UFC is therefore controlled by the power of government agencies operating at the Federal level, but compliance with federal agencies has allowed the UFC to gain a high level of autonomy.

Despite media, public, and political concerns around the reputation of the UFC and MMA, the UFC has been largely successful in minimising reputational damage regarding athlete welfare, doping infringements (Fares et al. Citation2020), gambling infractions, and the medical costs associated with fighting (Burgos Citation2021), especially considering MMA is a dangerous sport with a high injury risk (Bledsoe et al. Citation2006, Otten et al. Citation2010, Jensen et al. Citation2017). A growing body of literature is beginning to explore the complexities of health risk cultures (Atkinson Citation2019, Channon Citation2020, Lenartowicz et al. Citation2023). Fighters too have a growing awareness of health risks as a recent poll demonstrated in which 61.2% of MMA fighters expressed concerns about long-term brain damage (Gross Citation2020). Although the UFC does donate monies to medical research, specifically relating to brain injury (Marrocco Citation2021), it can be argued that the amount allocated is negligible by comparison with revenue generated. Furthermore, the UFC does not provide long-term health insurance for their athletes as they are not employees (Mahjouri Citation2021). Yiu et al. (Citation2020) note that the UFC has adopted a strategy of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to help maintain its growth trajectory and to mitigate future business risks. However, to what extent the CSR strategy is authentic rather than a cynical marketing initiative is debatable (McWilliams et al. Citation2006, Rangan et al. Citation2015).

It can be noted that the failure of rival promotions in the period 1997–2001 was due, to a large extent, to reputational damage resulting in public and political opposition, alongside incompetent business practices in an economic decline (Hess Citation2007). The UFC’s largest competitor was based in Japan, as American-based organisations were not successful. It took until around 2006 for successful MMA organisations, for example Strikeforce, to provide significant competition in the USA (Nash Citation2014). It has taken the UFC two decades to improve the image of MMA, resulting in significant profit and power over the sport and at the heart of the strategy is the UFC’s figurehead Dana White, whose charisma, or referent power, resulted in building reputation and legitimacy. Dana White has received both political and media support to help his lobbying activities via a successful public relations exercise that has served to marginalise contentious issues within MMA (Gaarenstroom et al. Citation2016). The extent of his influence is found in his personal connections with senior political figures, particularly Republican Party politicians. A study of monopolies (Geisst Citation2000) found a long history of empire building by influential entrepreneurs in the USA operating in a favourable corporate environment, and the UFC can also be cited as one such organisation possessing monopoly power (Nash Citation2021).

Furthermore, the UFC has demonstrated its power even in a highly regulated environment during the Pandemic (2020–22), mainly between March and September 2020 (Two Circles Citation2020) by hosting events outside of the USA such as at ‘Fight Island’ in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where there was less regulation (Butryn and Masucci Citation2020, Ordonez Citation2021). In most countries, sports events were cancelled or modified during the Pandemic, but the UFC found a way to stage events. The UFC was also the first sporting organisation to hold an event in the USA since the spread of COVID-19, with much support coming from Donald Trump. Dana White’s charismatic leadership led to the UFC gaining favourable treatment from the former president to grow their brand further. Despite an 80% decline in revenue for the Endeavor group during the Pandemic and gambling activities reduced, the UFC provided an opportunity to gamble on fight events that resulted in a 46% increase in its fan-base and today MMA is a top four sport in the USA in terms of audience (Gavia Citation2022). These opportunities were claimed via the personnel connections between the Saudi royal family and the ‘UFC family’.

It can be concluded from an analysis of media content, in combination with a review of published literature, that the UFC is a skilled promoter, lobbyist, and broker with a high-level business acumen and competence. In this sense, the UFC is adept as using ‘smart power’ (Nye Citation2011) in creating monopoly and monopsony power in MMA. However, the UFC operates in a ‘favourable’ corporate culture in the USA that encourages ‘free enterprise’ with the support of corporate partners (sponsors, broadcasters), minimal competition, and in a political space characterised by relatively weak regulation or oversight compared to other sports.

Conversely, the power the UFC have in MMA may not be sustainable in the mid to longer term if it cannot evade reputational damage, reducing legitimate power. For example, the UFC is arguably influenced by the ‘soft power’ strategy (Nye Citation2005) of the President of Chechnya where fighters from the Akchat Fight Club compete in the UFC as independent contractors, damaging the reputation of the UFC and MMA as they are associated with a dictatorship. Associations with Saudi Arabia and UAE also pose reputational risks given human rights abuses (Zidan Citation2019), and within the USA, the UFC’s relationship with Donald Trump may also be a reputational risk. In the case of Chechnya, Zidan (Citation2023c) observes, ‘Until the UFC’s relationship with Kadyrov begins to cost it, whether in the form of hefty fines from the U.S. Treasury for breaking sanctions or as sticking points with sponsors and broadcast partners, the sad truth is that the organization is unlikely to take any action to limit its ties to the brutal warlord’. Finally, the recent acquisition of WWE could pose a reputational risk because professional wrestling is widely regarded as ‘sports entertainment’ rather than an authentic sport and the recent resignation of Vince McMahon following allegations of sex trafficking may also inflict reputational damage on both WWE and the UFC following the recent merger (Feldscher and Goldman Citation2024).

Discussion: power relations in MMA

This discussion centres on power relations in MMA and in particular the strategic action of the UFC to gain, retain, and sustain power as the leading promoter. According to French and Raven (cited in Kovach Citation2020) it is important to identify the types of power that are effective strategically in meeting the aims of an organisation or individual. identifies six types of power and gives examples of where the UFC have used this type of power, although all forms of power overlap in practice.

Legitimate power

The UFC has extensive legitimate power or normative power by being the recognised authority in MMA. The UFC has control of titles as the sanctioning body and therefore awards status and prestige to fighters. Over time it has acquired the highest credibility in MMA as the leading promoter in the market. Athletes accept the legitimate power of the UFC and are largely compliant with obligations in contracts. However, the acquisition of legitimate power took two decades as the sport lacked legitimacy in its original format. The introduction of a set of rules overseen by regulatory bodies has resulted in political and public acceptance of MMA as a ‘sport’. To build and sustain legitimate power, the UFC has focused on public relations to normalise the sport albeit conceding modifications to the rules and increased surveillance by federal agencies.

The strategy to increase legitimacy has involved seeking to control a ‘narrative’ that the UFC have constructed. For example, the UFC has adopted a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategy to reduce public and political concerns about the sport and attempt to mitigate any threats to its reputation. Over two decades, the UFC has built its ability to mitigate reputational damage that could have undermined its legitimacy. It has acted to reduce the impact of ‘scandals’ relating to athlete welfare and doping infringements for example that may have resulted in political pressure and increased regulation.

However, the recent formation of a more powerful monopoly and monopsony in combat sports with the procurement of WWE, could result in reputational damage given that WWE is a ‘scripted sport’. In time, the association with WWE may raise questions regarding the authenticity of MMA itself and this may result in a loss of customer loyalty with implications for revenue, profit, market share, and control of the sport. Legitimate power may also diminish should there be a loss of support from sponsors and broadcasters. Currently, however, the UFC is the only brand in MMA with the power to guarantee PPV sales (Nash Citation2022b).

The two ongoing lawsuits may also be critical in the UFC maintaining its legitimate power in the mid to long term. In approximately 90% of anti-trust cases in the USA, a financial settlement is reached without the case proceeding to the highest courts. Tabuena (Citation2021a) and Nash (Citation2021b) believe that a settlement may be reached that does not impact significantly on the UFC’s business practices. Therefore, the UFC are likely to benefit from a ‘favourable’ settlement via the courts that may render changes to their business model unnecessary as well as the potential of significant financial and reputational damage being mediated. The plaintiffs in turn may settle for compensation instead of proceeding with legal action that may fail after many years. The key issue to be decided is whether the athletes are entitled to a share of the revenue generated by the UFC in a period of rapid expansion when fighter compensation (wage level) increased but not relative to the increase in revenue (wage share). Although a monopoly and monopsony exist in MMA, it may be legal, unless it was acquired illegally by intentionally eliminating competition (Pride and Strikeforce). This is difficult to prove with any degree of certainty.

Finally, the UFC association with financial backing from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Chechnya offer a threat to the legitimate power of the organisation. Repressive regimes facing accusations of human rights violations and political corruption have been accused of ‘sportswashing’ (Zidan Citation2018). However, as of the time of writing, the UFC has legitimate power within MMA as the main promoter and sanctioning body that has contracts with all the ‘top’ athletes, the strongest reputation, a level of authority in the sport, and the largest market share. Therefore, its legitimate power is strong and may be hard to diminish given its foundation in resource-based power.

Reward power

Reward power can be defined as the ability ‘to give or withhold rewards based on performance as a major source of power that allows managers to have a highly motivated workforce’ (Jones and George Citation2015, p. 333). The UFC has significant reward power as the most affluent organisation in MMA. The UFC is central to a powerful coalition of interests that includes sponsors and broadcasters. Additionally, competitors are to some extent resource dependent on the UFC for their relative success and have very limited financial power in comparison. Competitors have benefited from the UFC making the sport more popular, as well as signing notable former UFC fighters. Reward power has taken the form of financial acquisitions of competing interest groups, purchases of assets, securing sponsorships and the sale of broadcasting rights resulting in maximising media promotion (Critchfield Citation2014, Harty Citation2014, Nash Citation2016, Citation2022a, Gift Citation2020, Citation2022b). The UFC has also sought to manipulate the political environment by acquiring the support of the Republican Party and specifically the former President, Donald Trump (Zidan Citation2020, Athanur Citation2022). Finally, the UFC has sought to modify the legislative and regulatory environment in specific States within the USA (Cruz Citation2020).

At the core of reward power is the control over athlete contracts, including wages and rewards. The UFC can provide positive rewards in the form of opportunities to compete, wage levels, bonuses, personal recognition, status, and can exclude others who have sought the power to collectively bargain. Despite UFC wages not matching revenue growth, they can still offer substantial wages (Caves et al. Citation2022). The potential of a high wage level alongside other reward factors makes the UFC a desirable promotion to many athletes. The barriers and deterrent to unionisation within MMA are high. Supporting a union has led to fighters being released by the UFC. Litigation against the UFC is unlikely to benefit athletes and, as stated, the ongoing lawsuits may not impact on the power of the UFC, especially with the recent merger of the UFC and WWE.

Referent power

According to Fuqua et al. (Citation1998) referent power can be associated with the power of a role model. It is dependent on respecting, liking, and holding another individual in high esteem, and usually develops over a long period of time. It can be claimed that loyalty to the UFC has been acquired via the charismatic leadership qualities of Dana White, the UFC President. By employing a president with a favourable media profile, particularly in Republican controlled states and the ‘right wing’ media, the UFC has built its capacity for effective lobbying, public relations, and impactful marketing. The use of Referent power has built a brand with a loyal customer base including celebrities with a strong social media profile as well as political support including from a former US President.

This form of power has been sustained by marginalising and excluding athletes who have opposed or criticised the UFC leadership. The strength of this power is demonstrated with the continuation of public support despite Dana White being a part of several controversies. However, referent power may not be sustainable with a change of leadership. It is noted that leadership has been a critical factor in the growth of the UFC and a change of leadership may impact the UFC’s referent power. The recent merger of the UFC and WWE has created a role for Dana White and the potential for a more senior role within the new organisation. Therefore, referent power may be maintained in the foreseeable future.

Coercive power

Coercive power is found in the capacity to penalise others (Kovach Citation2020). Critical to the UFC’s control of MMA is control of their most valuable assets, the athletes (fighters). This has been achieved through contract negotiations resulting in a number of key consequences for fighters, who have the status of independent contractors. This includes agreeing to a fixed contract duration, which was 5 years until recently, financial consequences such as a level of compensation per fight with performance-related bonuses, and no access to personal sponsorship or revenue from image rights. Additionally, not receiving the benefits available to employees such as health insurance. These are relatively poor terms by comparison with other sports. Non-compliance with these terms results in termination of contract. Additionally, there is currently no opportunity for collective bargaining via an athlete union or representation by an association since support for collective representation has been largely supressed.

It could be argued that if fighters such as Conor McGregor (the UFC’s top earner) and others became figureheads to challenge the UFC’s business model and supported unionisation it could pressure the UFC to modify its control over athletes. However, the incentive for high earning athletes to support unionisation is minimal. Former UFC heavyweight champion Francias Ngannou stated that he would only re-sign if the UFC agreed to allow in-cage sponsorships and health insurance (Bohn Citation2022, Raimondi Citation2023). However, the UFC held all the negotiating power and did not agree to his terms (Varriale Citation2019).

Zidan (Citation2023a) concludes that the UFC ‘offers one-sided and restrictive contracts, controls fighter likeness, and enforces clothing and sponsor policies without any negotiation with fighters. None of this is reflective of a legitimate independent contractor relationship’. Further, Gift (Citation2020) notes that contracts lack transparency. A lack of accountability is the outcome of the UFC being both the promoter and the sanctioning body. Also, Weber (Citation2018) argues that the contractual terms that MMA fighters have faced closely resemble similar ‘abuses’ of power in professional boxing before the Ali Act was implemented. Additionally, Gaul (Citation2017) states that the UFC’s market dominance has left fighters vulnerable to exploitation where fighter wage share throughout the last 11 years has remained the same at 19–20% (Gift Citation2022b).

Expert power

The UFC has demonstrated significant expert power with the capacity to outperform competitors. The UFC is undoubtedly a skilled promoter, lobbyist, and broker, with high-level business expertise and competence. Where competitors have perceived or assumed the UFC has superior skills or abilities, they have in effect awarded power to the ‘expert’. Part of the strategy to obtain and sustain expert power is to acquire personnel with expertise. This includes individuals who can act as a powerful legal team to contest the ongoing litigation, a media team consisting of powerful broadcasters such as ESPN and powerful sponsors such as Venum, with extensive audience reach and other support services.

Furthermore, the UFC has acquired key personnel from rival promoters to join the UFC ‘family’ (Leonard Citation2021). The ‘expert power’ of the UFC has arguably been magnified with the merger with WWE (Haynes and Rodriguez Citation2023). As a result of harvesting expert power, the UFC has also been a successful lobbying body, not only in the USA but in other countries. For example, in the province of Ontario, Canada, lobbying resulted in legal constraints at both the federal and provincial levels being rescinded (Walters and Heine Citation2021).

Informational power

Another source of power acquired by the UFC is Informational power. This type of power results from possessing knowledge that others need or want. In an age of information technology, this type of power is increasingly relevant to a business and political strategy. The UFC has been successful in demonstrating informational power via creating barriers to access via Pay Per View (PPV) and in managing contracts with athletes that are not fully transparent. Not all information is readily available, and some information is closely controlled by the UFC. This can lead to unethical practice, poor governance or even corruption and, whilst questions remain about accountability and transparency, the UFC to date has evaded critical investigation despite journalistic enquiries.

In practice, the UFC may be a ‘closed network’ that creates significant barriers to access into the market and limited growth opportunities for existing smaller competitor promotions. Nash (Citation2021b) observes that monopoly power can be measured by the extent to which the UFC can set prices for events that competitors follow. It is the UFC that has the market information to develop powerful strategies that limit access to the market for MMA.

Insights from the work of Etzioni (Citation1975, cited in Mullins and Rees) potentially support the analysis provided pending further research. In particular, Etzioni’s focus on remunerative power and normative power can be equated with reward power and legitimate power respectively, where athletes have a calculative involvement with the UFC, complying with the UFC contract controls, and accepting its symbolic rewards of esteem and prestige, in return for financial compensation and ‘immortality’ as athletes. Clearly this relationship is open to exploitation by the UFC as is demonstrated, arguably, in its negligence of athlete welfare and curtailment of athlete autonomy. Moreover, insights on power by Nye (Citation2005, Citation2011) as applied to this study serve to highlight how the UFC has utilised both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power strategies to achieve control over MMA with a particular emphasis on control of athlete contracts, both the legally binding agreement and the ‘psychological contract’. This legitimised arrangement of power, alongside other strategies, has enabled the UFC to expand its business operations exponentially over the last decade to the extent that control of athlete contracts has been increased since the formation of TKO.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the UFC is likely to maintain its financial monopoly and monopsony power over MMA in the USA, at least in the short to mid-term because of its strong market position, limited competition, athlete controls via restrictive contracts, ineffective unionisation, and weak political, legal, and regulatory oversight, particularly at the national level. Over a twenty-five-year timespan, the UFC and its partners have been successful in acquiring power over MMA and potentially it can build its power base in acquisitions and mergers with other combat sports as implied with the 2023 purchase of WWE.

The UFC has utilised a range of powers to build its control of MMA including legitimate, referent, reward, expert, informational, and coercive types of power. Apart from the employment of coercive power such as sanctions, the UFC uses ‘soft’ power to achieve its objectives. Power is observable in the strategic action of the UFC but also non-observable and contextual. The strategic action of the UFC is seen in the control of athletes via compliance-based contracts without transparency; acquisition of competitor promotions, athletes, expertise, and commercial contracts; public relations and lobbying activities to shape the political, legal, and regulatory context; and in its successful attempt to build reputation and legitimacy. The UFC also has significant influence over the context in which MMA operates, with minimal critical scrutiny, accountability, or transparency in athlete contracts, for example. The UFC has also been successful in acquiring a level of political and media support to control the narrative around MMA and minimise reputational risk.

Clearly, the six types of power identified in this study are interrelated, and it is difficult to differentiate and demarcate one form of power from another. However, creating a typology offers a point of entry to understanding and analysing power-relations in MMA. Reflecting on the ‘three faces of power’ identified by Lukes’ (1974, in Kidd et al. Citation2010) power is centralised in MMA (elite theory) rather than widely distributed among competing interest groups (pluralism). Although there is a plurality of organisations in MMA, only one organisation has monopoly power. A neo-Marxist theory of power is also supported to an extent because there is limited market competition that favours one interest group in an environment likely to produce a monopoly albeit that the favoured interests are not a coherent and discernible economic class. Additionally, labour is controlled by one dominant interest group that has significant financial and economic power. In this study, as Lukes notes, power is observable in the strategic action of an organisation or group and unobservable in the lack of transparency in contractual arrangements, for example. Power is also contextual since the UFC established their dominance in a favourable corporate environment with a level of support from senior political figures.

However, looking forward, MMA faces very similar challenges encountered in the governance of boxing and other combat sports. There is a potential for reputational damage that could be a threat to the UFC’s legitimacy within MMA. The use of legitimate power may therefore prove to be central to the UFC’s strategy of expanding its monopoly and monopsony power in partnership with the WWE and other stakeholders.

Acknowledgment

This article is based on primary research originally undertaken by I.E. King as part of his undergraduate dissertation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Shatti, S. 2022. Tim Kennedy reveals how ‘fear’ killed the MMAAA’s infamous UFC unionization effort: ‘Nobody would do it’. MMA Fighting [ online]. 8 June. [Accessed 11 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.mmafighting.com/2022/6/8/23160281/tim-kennedy-reveals-how-fear-killed-the-mmaaas-infamous-ufc-unionization-effort-nobody-would-do-it

- Anon. 2018. ESPN to broadcast 30 UFC events per year during 5-year deal. Espn. [ Online]. 23 May. [Accessed 3 February 2023]. Available from: https://africa.espn.com/mma/story/_/id/23581729/espn-ufc-reach-five-year-television-rights-deal

- Ansari, D. 2022. “It will happen in MMA, it’s just a question of time” – Georges St-Pierre believes formation of an MMA fighters’ association is inevitable. Sportskeeda. [ Online]. 29 October. [Accessed 12 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.sportskeeda.com/mma/news-georges-st-pierre-believes-mma-fighters-union-will-inevitably-take-place-future

- Aris, J.B. 2013. The Fight as an Independent Contractor. Sherdog. [Online]. 29 June. [Accessed 6 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.sherdog.com/news/articles/The-Fight-as-an-Independent-Contractor-53481#:~:text=Because%20UFC%20fighters%20are%20independent%20contractors%2C%20the%20Internal,an%20IRS%20Form%201099-MISC%20to%20report%20their%20earnings

- Athanur, P. 2022. How Dana White used Donald Trump to prevent the Muhammad Ali Expansion Act from benefitting MMA fighters. First Sportz. [ Online]. 9 December. [Accessed 15 January 2023]. Available from: https://firstsportz.com/ufc-how-dana-white-used-donald-trump-to-prevent-the-muhammad-ali-expansion-act-from-benefitting-mma-fighters/

- Atkinson, M., 2019. Sport and risk culture. In: K. Young, eds. Research in the Sociology of Sport, 12. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, 5–21.

- Atkin, N. and Taylor, T. 2022. ONE Championship signs 5-year US broadcast deal with Amazon’s Prime Video. South China Morning Post. [ Online]. 28 April. [Accessed 17 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/sport/martial-arts/mixed-martial-arts/article/3175742/one-championship-signs-5-year-us-broadcast

- Baldwin, N. 2018. Kajan Johnson: Project Spearhead needs a ‘miracle’ to succeed. Bloody Elbow. [ Online]. 26 October. [Accessed 4 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.bloodyelbow.com/2018/10/26/17992284/kajan-johnson-project-spearhead-miracle-success-leslie-smith-al-iaquinta-ufc-mma-news-unionization

- Battison, P., 2023. Jeff Novitzky: From taking down Lance Armstrong to cleaning up the UFC. BBC Sport, April 25. On-line: Jeff Novitzky: From taking down Lance Armstrong to cleaning up the UFC - BBC Sport. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- Birren, G.F. and Schmitt, T.J., 2017. Mixed martial artists: challenges to unionization. Marquette Sports Law Review, 28 (1), 85–106.

- Bissel, T. 2021. Report: Venum deal gives UFC champions a $2,000 pay rise. Bloody Elbow. [ Online]. 1 April. [Accessed 12 January 2023]. Available from: https://bloodyelbow.com/2021/04/01/ufc-venum-reebok-deal-details-emerge-champions-fighters-pay-rise-mma-news/

- Bledsoe, G.H., et al. 2006. Incidence of Injury in Professional Mixed Martial Arts Competitions. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 1 (5), 136–142.

- Bohn, M. 2022. Francis Ngannou walking away from UFC, Jon Jones fight is both a commendable and frightening risk | Opinion. MMA Junkie. [ Online]. 15 January. [Accessed 17 February 2023]. Available from: https://mmajunkie.usatoday.com/lists/ufc-news-francis-ngannou-turns-down-contract-jon-jones-fight-dana-white-risk-opinion

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2021. Thematic Analysis. A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

- Burgos, J. 2021. UFC fighter’s search for affordable health insurance puts spotlight again on the fighter pay issue. MixedMartialarts. [ Online]. 11 September. [Accessed 5 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.mixedmartialarts.com/news/ufc-fighters-health-insurance-issue#:~:text=A%20call%20to%20action%20Instagram%20post%20from%20UFC,the%20social%20media%20platform%20asking%20for%20some%20advice.

- Butryn, T.M. and Masucci, M.A., 2020. The Show Must Go On: The Strategy and Spectacle of Dana White’s Efforts to Promote UFC 249 during the Coronavirus Pandemic. International Journal of Sport Communication, 13 (3), 381–390. doi:10.1123/ijsc.2020-0240.

- Caves, K., Tatos, T., and Urschel, A., 2022. Are the Lowest-Paid UFC Fighters Really Overpaid? A Comment on Gift (2019). Journal of sports economics, 23 (3), 355–365. doi:10.1177/15270025211049790.

- Channon, A., 2020. Edgework and mixed martial arts: Risk, reflexivity and collaboration in an ostensibly ‘violent’ sport. Martial Arts Studies, 9, 6–19. doi:10.18573/mas.95

- Conklin, M., 2020. Two Classifications Enter, One Classification Leaves: Are UFC Fighters Employees or Independent Contractors? Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, 29 (2), 227–250.

- Conway, T. 2022. Dana White says Raising UFC Fighter’s Pay is ‘Never Gonna Happen while I’m Here’. Available from. Dana White Says Raising UFC Fighters’ Pay is ‘Never Gonna Happen While I’m Here’ | News, Scores, Highlights, Stats, and Rumors | Bleacher Report.

- Courtney, A. 2016. “Fighters are fearful of the UFC” – Jeff Borris on creating a Professional Fighters Association. Talksport. [ Online]. 17 August. [Accessed 13 December 2022]. Available from: https://talksport.com/sport/mma/117355/fighters-are-fearful-ufc-jeff-borris-creating-professional-fighters-association-160817206714/

- Critchfield, T. 2014. Class-Action Lawsuit Filed Against UFC by Cung Le, Jon Fitch, Nate Quarry. Sherdog. [ Online]. 16 December. [Accessed 19 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.sherdog.com/news/news/ClassAction-Lawsuit-Filed-Against-UFC-by-Cung-Le-Jon-Fitch-Nate-Quarry-78853

- Cruz, J., 2017. Sports and the First amendment: UFC is the Latest Challenger. Marquette Sports Law Review, 27 (2), 355–373.

- Cruz, J., 2018. Rethinking the Use of Anti-Trust law in Combat Sports. Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 28 (1), 63–96. doi:10.18060/22331.

- Cruz, J. 2019. Is the Muhammad Ali Act helping protect fighters? Fight Sports Law. [ Online]. 21 September. [Accessed 17 April 2023]. Available from: https://fightsportslaw.com/post/187853615219/is-the-muhammad-ali-act-helping-protect-fighters

- Cruz, J., 2020. Mixed Martial Arts and the Law. Disputes, Suits and Legal Issues. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Devine, F., 1995. Qualitative Analysis. In: D. Marsh and G. Stoker, eds. Theory and Methods in Political Science. MacMillan: Basingstoke. 137–153.

- Duncan, J., 2020. Re-Union for MMA: Reoccurring Issues Plaguing Mixed Marshal Arts Fighters and Potential Solutions. University of Denver Sports and Entertainment Law Journal, 23, 11–44. Available from: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/denversel23&id=17&collection=journals&index=

- Dundas, C. 2020. MMA fighters overwhelmingly support unionization, despite no clear path forward. The Athletic. [ Online]. 3 June. [Accessed 5 January 2023]. Available from: https://theathletic.com/1850784/2020/06/03/mma-fighters-support-association-unionization-no-clear-path/

- Dunn, S. 2022. What is the Muhammad Ali Act & What Would it Mean for MMA? Boardroom. [ Online]. 23 December. [Accessed 18 January 2023]. Available from: https://boardroom.tv/muhammad-ali-act-mma-boxing/

- Etzioni, A. 1975. A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations: on Power, Involvement and their Correlates. In: L.J. Mullins and Rees, G. Management and Organisational Behaviour. 13th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education. 844–845.

- Evanoff, J. 2022. Pro-Fighter Ali Expansion Act to Be Brought Before U.S. Senate in 2023. B.J Penn. [ Online]. 20 December. [Accessed 11 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.bjpenn.com/mma-news/ufc/pro-fighter-ali-expansion-act-to-be-brought-before-u-s-senate-in-2023/

- Fares, M.Y., et al. 2020. Doping in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC): A 4-year epidemiological analysis. Drug Test Analysis, 13 (4), 785–793. doi:10.1002/dta.2987.

- Feldscher, K. and Goldman, D., 2024. The WWE knew that Vince McMahon was a liability. So why did it bring him back after his scandalous departure? Atlanta, Georgia, USA: CNN Business.

- Fowlkes, B. 2017. Are UFC fighters employees or contractors? Why the distinction matters – and could mean millions. MMA Junkie. [ Online]. 12 August. [Accessed 28 January 2023]. Available from: https://mmajunkie.usatoday.com/2017/08/ufc-fighters-employees-or-independent-contractors

- French, J. and Raven, B., 1959. The Bases of Social Power. In: D. Cartwright, ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, 150–167.

- Fry, A. 2023. MMA franchise Bellator signs renewal deal with BBC in the UK. Digital TV Europe. [ Online]. 23 February. [Accessed 4 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.digitaltveurope.com/2023/02/23/mma-franchise-bellator-signs-renewal-deal-with-bbc-in-the-uk/

- Fuqua, E., Payne, K., and Cangemi, J., 1998. Leadership and the effective use of power. National Forum of Educational Administration and Supervision Journal, 15E (4), 36–41.

- Gaarenstroom, T., Turner, P., and Karg, A., 2016. Framing the Ultimate Fighting Championship: an Australian media analysis. Sport in Society, 19 (7), 923–941. doi:10.1080/17430437.2015.1096243.

- Gaul, J.C., 2017. The ultimate fighting championship and Zuffa: from human cock-fighting to market power. American University Business Law Review, 6 (3), 647–686.

- Gavia, P. 2022. America’s most savage CEO: dana White. [ Online] 31 December. [Accessed 24 April 2023]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8-qnUyJSlc

- Geisst, C.R., 2000. Monopolies in America: empire Builders and Their Enemies from Jay Gould to Bill Gates. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gift, P. 2014. Dissecting the UFC fighter antitrust lawsuit, part 1. Bloody Elbow. [ Online]. 17 December. [Accessed 24 April 2023]. Available from: https://bloodyelbow.com/2014/12/17/mma-ufc-fighter-antitrust-lawsuit-monopoly-monopsony-cung-le-nate-quarry-jon-fitch-part-1/

- Gift, P., 2019. Moving the Needle in MMA: On the Marginal Revenue Product of UFC Fighters. Journal of sports economics, 21 (2), 176–209. doi:10.1177/1527002519885432.

- Gift, P. 2020. How Long Are UFC Exclusive Contracts? Witness in Antitrust Suit Sheds Rare Light on MMA’s Business Side. Forbes. [ Online]. 10 November. [Accessed 4 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulgift/2020/11/10/how-long-are-ufc-exclusive-contracts/?sh=1b1b43733cd8

- Gift, P. 2022b. UFC Fighter ‘Wage Share’ Held Steady at 19–20% for 11 Straight Years. Forbes. [ Online]. 19 April. [Accessed 2 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulgift/2022/04/19/ufc-fighter-wage-share-held-steady-at-19-20-for-11-straight-years/

- Gift, P. 2022c. Judge Pauses Follow-On Antitrust Lawsuit Against the UFC. Forbes. [ Online]. 2 October. [Accessed 2 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulgift/2022/10/02/judge-pauses-follow-on-antitrust-lawsuit-against-the-ufc/?sh=de0252c3675a

- Gift, P. 2022d. UFC posts best financial year in company history. Forbes. [ Online]. 16 March. [Accessed 28 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulgift/2022/03/16/ufc-posts-best-financial-year-in-company-history/?sh=4dae7ac32330

- Graham, A.B. 2016. New York ends ban and becomes 50th state to legalize mixed martial arts. The Guardian. [ Online]. March 22. [Accessed 31 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/mar/22/new-york-legalizes-mma-ufc

- Greene, N. 2018. How John McCain Grew to Tolerate MMA, the Sport he Likened to “Human Cockfighting”. Slate. [ Online]. 26 August. [Accessed 2 March 2023]. Available from: https://slate.com/culture/2018/08/john-mccain-ufc-how-he-grew-to-tolerate-mma-the-sport-he-considered-human-cockfighting.html

- Gross, J. 2016a. How the Ali Act could upset the power balance between UFC and its stars. The Guardian. [ Online]. 2 May. [Accessed 11 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2016/may/02/ufc-muhammad-ali-act-mma-conor-mcgregor-dispute

- Gross, J. 2016b. UFC fighters make first steps to unionize: ‘It’s a fight for what’s right’. The Guardian. [ Online]. 1 December. [Accessed 18 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/dec/01/ufc-fighters-union-wme-img-better-treatment

- Gross, J. 2020. For many MMA fighters, CTE fears are already a reality. The Athletic. [ Online]. 4 June. [Accessed 20 December 2022]. Available from: https://theathletic.com/1854544/2020/06/04/mma-fighters-brain-health-cte-is-reality/

- Hannoun, F. 2022. UFC signs Josh Fremd, Isaac Dulgarian in latest episode of ‘Dana White: Lookin’ for a Fight’. MMA Junkie. [ Online]. 7 February. [Accessed 24 April 2023]. Available from: https://mmajunkie.usatoday.com/2022/02/ufc-contract-josh-fremd-isaac-dulgarian-dana-white-lookin-for-fight-mma

- Harty, C. 2014. 5 MMA Organizations Bought Out by UFC. The Richest. [ Online]. 16 January. [Accessed 4 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.therichest.com/mma-sports/5-mma-organizations-bought-out-by-ufc/#:~:text=5%20MMA%20Organizations%20Bought%20Out%20by%20UFC%201,%28WEC%29%3A%202001-2010%20…%205%201%20Strikeforce%3A%201986-2013%20

- Haynes, S. 2021. The Fight Analyst Interviews: John Nash Discusses the Latest in MMA Finance | Crooklyn’s Corner – 19. Bloody Elbow Podcasts. [ Online]. 25 October. [Accessed 24 April]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQr4pWo8DxI

- Haynes, S. and Rodriguez, V. 2023. UFC-WWE merger creates Vince and Ari Axis of Power. The Level Change Podcast 238. April 4. [Accessed 6 April 2023]. Available from: https://bloodyelbowpodcast.substack.com/p/ufc-wwe-merger-vince-mcmahon-ari-emanuel-mma-new?utm_source=podcast-email%2Csubstack&publication_id=1474930&post_id=112526297&utm_medium=email#details

- Hess, P., 2007. The Development of Mixed Martial Arts: From Willamette Sports LJ. 4, 1. Willamette University, Salem, Oregon, USA.

- Hill, A. 2013. A timeline of UFC rules: From no-holds-barred to highly regulated. Bleacher Report. [ Online]. 24 April. [Accessed 12 March 2023]. Available from: https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1614213-a-timeline-of-ufc-rules-from-no-holds-barred-to-highly-regulated

- Jensen, A.R., et al. 2017. Injuries Sustained by the Mixed Martial Arts Athlete. Sports Health, 9 (1), 64–69. doi:10.1177/1941738116664860.

- Jones, G. and George, J., 2015. Essentials of Contemporary Management. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education.

- Kaplow, L., 1985. Extension of monopoly power through leverage. Columbia Law Review, 85 (3), 515–556. doi:10.2307/1122511.

- Kidd, W., Legge, K., and Harari, P., 2010. Politics and Power. Palgrave-MacMillan: Basingstoke.

- Kovach, M., 2020. Leader Influence: A Research Review of French and Raven’s (1959) Power Dynamics. The Journal of Values-Based Leadership, 13 (2), 15. doi:10.22543/0733.132.1312.

- Lenartowicz, M., Dobrzycki, A., and Jasny, M., 2023. Let’s face it, it’s not a healthy sport’: Perceived health status and experience of injury among Polish professional mixed martial arts athletes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 58 (3), 589–607. doi:10.1177/10126902221119041.

- Leonard, M. 2021. UFC Faces Antitrust Suit by Fighters Over ‘Iron-Fisted Control’. Bloomberg Law. [ Online]. 24 June. [Accessed 25 April 2023]. Available from: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/ufc-faces-antitrust-suit-by-fighters-over-iron-fisted-control

- Lowndes, V., Marsh, D., and Stoker, G., eds., 2017. Theory and Methods in Political Science. Fourth ed. London: Bloomsbury.

- Mahjouri, S. 2021. Dana White backtracks on UFC fighter health benefits: ‘I responded to the wrong guy’. MMA Mania. [ Online]. 8 June. [Accessed 18 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.mmamania.com/2021/6/8/22525067/ufc-president-dana-white-fighter-health-benefits-mma-news-video

- Marrocco, S. 2021. UFC pledges additional $1 million to Professional Athletes Brain Health Study. MMA Fighting. [ Online]. 7 January. [Accessed 11 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.mmafighting.com/2021/1/7/22219007/ufc-pledges-additional-1-million-to-professional-athletes-brain-health-study

- Marsh, D. and Stoker, G., eds. 1995. Theory and Methods in Political Science. MacMillan: Basingstoke.

- McWilliams, A., Siegal, D.S., and Wright, P.M., 2006. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies, 43 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00580.x.

- Milas, J., 2022. Out of the Octagon and into the Courtroom: The UFC’s Antitrust Lawsuit. De Paul Journal of Sport, 18 (1), 1–36.