ABSTRACT

Athlete maltreatment has become ‘one of the greatest concerns faced by governing bodies, authorities and practitioners in sport’ (Stirling 2009, p. 1901). Its causes broadly stem from: (1) the culture and authority structures in organised sport; (2) the limited legal rights of athletes; and (3) a fragmented system of organisational oversight. Cutting across these causes is the distinct ‘policy mix’ within the elite sport system itself. Drawing upon a theoretical framework located within ‘new institutionalism’ and an interpretive qualitative approach using document analysis and semi-structured interviews, this investigation focuses on how policy instruments (e.g. programmes, rules, budgets, etc.) combine to shape/reinforce the behaviour and views of athletes, coaches, and administrators. Findings show that the policy instruments within the existing hierarchical structure of the elite sport system are interconnected and complement each other to mutually facilitate the attainment of elite sport success. Overall, this study suggests that the mix of policy instruments aimed at achieving the state’s sport/political objectives may sustain and reinforce maltreatment.

Introduction

According to Stirling (Citation2009), ‘issues of athlete maltreatment have arguably become one of the greatest concerns faced by governing bodies, authorities and practitioners in sport’ (p. 1091). Yet, despite this concern serious athlete maltreatment scandals continue to occur globally, with many countries remaining committed to elite sport systems for a range of reasons including ideological and political purposes (Green and Houlihan Citation2005, De Bosscher et al. Citation2009). Thus, while it provides a platform for displays of nationalism and nation-state success, involvement in elite sport can represent a tragic experience for many athletes, characterised by various types of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse and neglect) (Parent and Fortier Citation2018, Kerr et al. Citation2019).

One country that has been confronted with maltreatment in its pursuit of national success is South Korea (hereafter Korea). In 2019, in response to a number of high-profile scandals and widespread concerns about athlete maltreatment, the government appointed a Sport Reform CommitteeFootnote1 to review the overall system and causes of maltreatment (Hong Citation2020, Kim and Jang Citation2022). The wide-ranging reports consisted of approximately 300 pages and included seven recommendations, resulting in some minor improvements (An and Jeoung Citation2020, Hong Citation2020). Notably, the committee’s recommendations focused on individual parts of the sport system rather than the system as a whole. Thus, little attention was devoted to potential interactions within or between these parts, including the potential mix of policy instruments, and their role in sustaining problems.

To date, the causes of athlete maltreatment have been identified as stemming from a range of sources including: (1) the culture of organised sport; (2) the power of authority figures; (3) the autonomy of sport organisations and associated absence of oversight; (4) the lack of, or limited, legal rights of athletes; and (5) the fragmented system for addressing maltreatment (Donnelly and Kerr Citation2018, Kerr et al. Citation2019, Human Rights Watch Citation2020). This body of pioneering research has provided detailed features of maltreatment and increased awareness of the problem, raising its profile and significance on the global agenda. However, while elite sport systems feature strongly as a cause of maltreatment (to the extent that these can exploit athletes through unfair contracts, inadequate compensation, and limited career development opportunities), we know relatively little about the combination of policies and programmes and their synergistic effects. Moreover, beyond the focus on elite sport, most research has surrounded Western sporting contexts. Therefore, it is imperative to consider the causes of maltreatment within different national and institutional environments.

One largely overlooked factor cutting across the above features and causes of maltreatment concerns the distinct institutional policy instruments within the elite sport system itself. Policy instruments are the tools that governments deploy to achieve public goals and broadly take the form of carrots (incentives), sticks (regulations) and sermons (information) (Serbruyns and Luyssaert Citation2006, Salazar-Morales Citation2018, Pacheco-Vega Citation2020). Through this conceptual lens, the tools of state-run elite sport systems (such as athlete relocation programmes or coach salary schemes) are important because they are not merely a matter of technical design; they are also a political exercise in which priorities are expressed and resources are committed (Peters Citation2002).

Indeed, policy instruments play an important role in bringing together ‘networks of heterogeneous actors’ as stakeholders come to share stories, knowledge and practices in the instrument’s design (Voß and Simons Citation2014, p. 16, Béland and Howlett Citation2016). For example, an instrument such as a new ‘integrity unit’ can bring together industry experts, media, athletes and academics in support of a common goal (see for example, Verschuuren and Ohl Citation2023). Hence, instruments can reshape the political landscape and create new constellations of actors who might be either advantaged or disadvantaged within this transformative process (Voß and Simons Citation2014, Béland and Howlett Citation2016, Capano and Howlett Citation2020). As will be described below, Korea’s youth athlete training camps (a policy instrument) connect schools with government sport agencies, a link which over time, has advantaged physical education teachers whose students win medals. In addition to conferring material advantages, it is worth noting that instruments also serve a symbolic function, gaining legitimacy from their adherence to the preceding decision-making process and embodying authoritative power (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). Thus, when multiple instruments combine, they operate within what is referred to as a ‘policy mix’ that interacts to sustain institutional structures and systems (Capano and Howlett Citation2020). From this perspective, the concept of a ‘policy instrument mix’ offers a theoretical approach towards understanding the synergistic consequences of the elite sport system, by providing an account of the historical emergence and contemporary interaction of instruments.

The purpose of this research is twofold. First, it seeks to identify, describe and trace the emergence of key policy instruments designed to support the Korean elite sport system. Korea’s elite sport structures are arguably distinct in comparison with Western systems, as the mix of public institutions (e.g. municipal government, tertiary education) are strongly directed from central government, allowing for a remarkable coherence of policy purpose and action. This coherence and potential complementarity (Kern and Howlett Citation2009, Rogge and Reichardt Citation2016) provides a unique context from which to examine the interactive effects of policy instruments. Second, drawing from interview data, this study explores how the mix of policy instruments around elite sport may contribute to the problem of athlete maltreatment and inhibit subsequent system-wide change. Capano and Howlett (Citation2020) highlight the lack of knowledge around the mechanisms activated by policy instruments and their impacts ‘on the ground’ (p. 7). To this end, we ask: how does the mix of instruments in the system shape the behaviours of coaches, athletes and sports organisation officials, and to what extent can we expect this mix to harness unexpected results? This research thus considers how policy instruments and their associated objectives, might constitute a particular interrelated governing system that contributes to, and perhaps even facilitates, athlete maltreatment. Overall, the aim is to understand the role of policy instrument mixes and their potential role in athlete maltreatment in elite sport.

The paper is divided into five sections. The first section explains new institutionalism and policy instrument mix as a theoretical framework. The second section provides an overview of the relevant context and governing structure underpinning the Korean elite sport system and its instruments. Section three outlines the methods used including data sources and data collection processes. The fourth section identifies and describes the Korean government’s four key instruments used to develop elite athletes: (1) the Semi-Professional Team System linked with businesses/workplaces (SPTS); (2) the Specialist Athlete System for developing student-athletes (SAS); (3) the National Sports Festival (NSF); and (4) the Collective Sports Training Camps (CSTC). The final section examines how and why mutual interactions of policy instruments may contribute to athlete maltreatment. Conceptually, the analysis draws from ‘new institutionalism’ and in particular, the tendency for complex policy mixes to contribute to sustaining institutional structures and systems (March and Olsen Citation2006, Rogge and Reichardt Citation2016, Capano and Howlett Citation2020).

Conceptual framework: new institutionalism and policy instrument mix

To explain the elite sport system with respect to a mix of policy tools, this study adopts a particular theoretical perspective – new institutionalism. The concept of ‘institution’ is a complex and multifaceted term that is generally utilised to describe social phenomena at a number of different levels such as organisations, written contracts and informal codes of conduct (Lowndes and Roberts Citation2013, Scott Citation2013). Arguably, if institutions are defined by hierarchical arrangements, rules, routines, roles, incentives, and norms (North Citation1990, Schmidt Citation2010, March and Olsen Citation2011, Peters Citation2019), an institutional analysis fits well with the concept of policy instruments.

As one of the primary approaches in political science, ‘institutionalist’ explanations see individuals and organisations as constrained by ‘formal and recorded rules’ that are constructed in a number of forms such as national and international laws, clauses in a constitution, regulations, licences and policies (March and Olsen Citation2006, Lowndes and Roberts Citation2013, Peters Citation2019). Subsequent rules can be established and be imposed within organisations to establish the behaviour of actors and regulate deviant actions (Peters Citation2019). In this way, the elite sport system can be understood as an institution that consists of a variety of nested rules, including regulations and organisational arrangements such as budgets and programmes.

Studies of maltreatment in sport have identified various causes of athlete maltreatment that broadly relate to such institutional considerations (Stirling and Kerr Citation2014, Mountjoy et al. Citation2016, Donnelly and Kerr Citation2018, Fortier et al. Citation2020, Willson et al. Citation2022). Fortier et al. (Citation2020), for example, observe that young athletes are vulnerable to maltreatment through talent recruitment procedures, because the process is highly competitive and the fear of missing out on opportunities can drive young athletes to endure maltreatment in the pursuit of their goals. Likewise, Willson et al. (Citation2022) assert that maltreatment issues may be facilitated by the self-governance and autonomy of sport organisations and their corresponding lack of independent/external oversight. Despite the recognition of these causes, most previous studies have considered these antecedents as general environmental determinants, and these have seldom been theoretically conceptualised (Kerr et al. Citation2019, Kavanagh et al. Citation2020, Roberts et al. Citation2020). In this respect, there is a need to analyse the institutional arrangements in the elite sport system because emerging maltreatment may, in part, be precipitated by those institutions.

As a theoretical lens, the concept of a ‘policy mix’ can help us understand outcomes of the elite sport system because it addresses the emergence and interaction of instruments and tools (Rogge and Reichardt Citation2016). According to Howlett (Citation2020), policy instruments are broadly defined as a variety of ‘tools or techniques of governance’ that include traditional substantive instruments (e.g. regulations) and procedural instruments (e.g. advisory committees) used to solve complex policy problems (p. 165). From this perspective, a policy instrument is a formal institution embodying a tangible interplay between politics and society supported by rules and regulations (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). Thus, the Korean elite sport system needs to be examined in relation to its policy instruments because their continued use may reinforce their legitimacy, making them more resistant to change, and ‘locked in’ over time (Howlett Citation2019, p. 32).

Context: the interrelated governing structure of Korean elite sport

South Korea, population 52 million, is a liberal democratic state that is heavily involved in elite sport. The Korean elite sport system consists of three main organisations including: (1) the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST) as a central administrative agency in charge of national sports policies for elite sport development and mass sport participation; (2) the Ministry of Education (MoE) as a government body for school sport policy and student-athletes; and(3) the Korean Sport and Olympic Committee (KSOC) as a quasi-government organisation that implements and administers elite sport policy and the national sports programme, via the National Sports Federations (NSFs). These agencies operate under two main laws to support the elite sport system: the ‘National Sports Promotion Act’ (1962) and the ‘School Sports Promotion Law’ (2012) (Shon Citation2019). The former initially sought to improve the health and wellbeing of participants (Chae et al. Citation2015) but was revised in 1982 to include the objective of promoting Korean national prestige through international elite sport. Today, the development of adult elite athletes is mainly based on the Act and implemented via key policy instruments (discussed in subsequent sections).

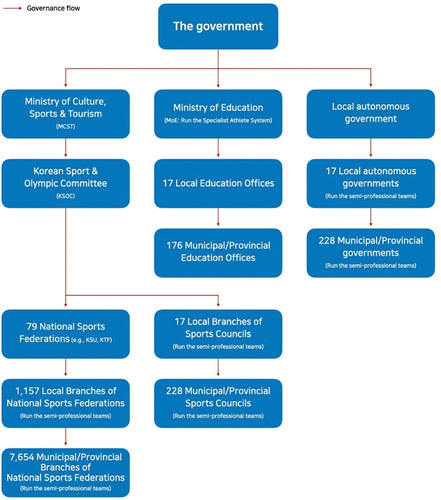

The KSOC is governed by the MCST and oversees the operation of 79 NSFs, 1,157 local branches of NSFs, 7,654 municipal/provincial branches of NSFs, 17 local branches of sports councils and 228 municipal/provincial sports councils (Korean Sport and Olympic Committee Citation2023). The MoE supervises the Specialist Athlete System for developing student-athletes and school sports teams through 17 local education offices and 176 municipal/provincial education offices. Local government is administered through 17 local autonomous governments and 228 municipal/provincial governments (see ). The sport activities of all organisations are primarily governed through provisions of the Act (Shon Citation2019). The Act is implemented through a hierarchical system, in which 79 NSFs oversee all elite athletes (student-athletes, semi-professional athletes and professional athletes) under the umbrella of the KSOC. Under such a hierarchical institutional arrangement, the KSOC (the principal) makes decisions that influence the NSFs (the agents) to operate in particular ways (Gailmard Citation2009). According to Peters (Citation2019), the ‘principal’ provides specific rules and guidelines to the agent, that in turn fulfils the principal’s objective. The agents (NSFs and other organisations) are induced to act according to particular strategies such as the use of oversight and performance-based budgeting as ways of ensuring compliance.

After the notable successes achieved at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, the Korean government increased its investments in elite sport (Yoo and Kang Citation2017). As with many developed nations, the Korean government utilised performance-based funding and investment strategies to pursue success (cf. Sam Citation2012). To receive funding from the KSOC, sport organisations needed a clear national objective of winning medals in international competitions as the key performance indicator (Song Citation2018). As a result, the 79 NSFs are not independent from the management and supervision of the KSOC and the latter has immense power to control a significant number of sports organisations (NSFs, sports councils and sports teams of the local and municipal/provincial governments). On the surface NSFs seem to operate independently because most NSF presidents are also presidents of ChaebolsFootnote2 (e.g. private companies such as Hyundai) however, their work is directly regulated by the KSOC via sport funding. Through this large-scale hierarchical structure, the government sustains its elite sport system via key policy instruments that mutually reinforce the pursuit of national success. Within the system, instruments operate as ‘cohesive techniques of governance’ in order to achieve ‘overarching policy objectives’ that work together (Rogge and Reichardt Citation2016, Capano and Howlett Citation2020). In other words, the interaction or mix of instruments is intended to produce a coherent and coordinated system. However, while the system’s instrument mix may lead to success in terms of medals, it may render itself vulnerable to maltreatment.

In 2019, the #MeToo movement in Korean elite sport attracted increased public attention resulting in the establishment of the Sport Reform Committee under the MCST by order of President JaeIn Moon. The committee conducted a comprehensive analysis of the overall sport system with the aim of implementing reforms and driving change. As a result of their analysis, the committee recommended: (1) establishment of the Korea Sport Ethics Centre; (2) improving school sport for student-athletes and general students; (3) enacting legislation for a fundamental law of sportFootnote3; (4) enhancing sport clubs for all; (5) changing the elite sport system and athlete development; and (6) separating the Korea Olympic Committee from the KSOC (Kim and Jang Citation2022). In its report, the committee recognised instruments in the elite sport system (e.g. the SAS and the CSTC) as factors that can lead to substantial human rights violations, encompassing acts of physical and sexual abuse, as well as infringements upon the right to education (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism Citation2019). However, four years after the reforms, student-athletes experiencing maltreatment continue to quit, while perpetrator coaches maintain their jobs (Choi Citation2023). One possible explanation for this situation is that while the committee recognised the potential impact of particular instruments such as the SAS and the CSTC, they did not examine their overall mix and connectedness.

Methods

This project employs an interpretive qualitative approach including: (1) document analysis and (2) semi-structured interviews with stakeholders and athletes (Elliott and Timulak Citation2005). Document analysis was conducted to obtain essential information to enhance understanding of how policy instruments are deployed and operate. In particular, documents help identify the formal rules within the elite sport system. Texts included state laws and official documents such as annual reports and strategy documents from the government and quasi-governmental organisations of sport (MCST, MoE and KSOC), as well as press releases. Documents were utilised to describe and clarify the following aspects: the connections between organisations, the objectives and anticipated outcomes of the elite sport system, the perspectives of stakeholders, the resources mobilised to support the system, and the specific policies that govern it. To this extent, document analysis supports and reinforces evidence from other sources such as semi-structured interviews (Yin Citation2009).

Interviews were conducted to obtain different perspectives and knowledge, gain an understanding of social contexts, and elicit individuals’ views and personal experiences (Fossey et al. Citation2002, Creswell et al. Citation2007). Interview data were collected from athletes and officials of key organisations including MCST, MoE, KSOC and two selected NSFs. To this end, interviewees were selected through a blend of purposive and snowball sampling utilising social networks that exist between participants of the target population (Bernard Citation2017). This study focused purposely on two categories of interviewees: (1) officials and staff members who work within the elite sport system and (2) athletes who could offer perspectives on both maltreatment and details about the institutional structures and systems of sport. Given the sensitive nature of the research, participant anonymity and their well-being were a priority (Bradbury-Jones et al. Citation2014, Mcmahon et al. Citation2022).

The interviewees’ contact information was acquired through lists of sport organisations. Participants were contacted via telephone and email, informed of the aim of the research and ethical consent secured. Overall, 18 interviews were conducted between January and December 2022, from: the MCST (n = 2), the MoE (n = 2), the KSOC (n = 2), the NSFs (n = 4), and adult elite athletes (n = 8: 5 male, 3 female; average age = mid-20s). General questions for all of interviewees explored their perceptions and experiences of the elite sport system, and its potential impact on athlete maltreatment. Questions for officials, administrators, and directors, focused on their institutionally-derived roles within the elite sport system. Each interview was conducted in Korean, lasted between one and two hours and was audio taped. The researcher transcribed the audio recordings, subsequently translating them into English with transcripts retained in both Korean and English. At this stage quotes were cross-checked by the authors to reach agreement on the interviewees’ meanings given potential linguistic/grammatical differences and nuances of expression. The data was coded and analysed with respect to concepts from institutional theory that aligned with the research questions (e.g. rules, regulations, and path dependency etc). For example, interview data related to the elite sport system and athlete maltreatment were categorised into a number of themes including: (1) the governing structure of the Korean elite sport system and the operative elements/features of policy instruments; (2) the links/connections among and between the instruments that interviewees could identify (RQ1); and (3) interviewees’ perspectives on the causal links between instruments and athlete maltreatment (RQ2). The next section provides an overview of policy instruments within the Korean elite sport system.

Policy instruments of the Korean elite sport system

This section outlines the four main policy instruments within the elite sport system including: (1) the Semi-Professional Team System linked with businesses/workplaces; (2) the Specialist Athlete System for developing student-athletes; (3) the National Sports Festival; and (4) the Collective Sports Training Camps. It incorporates interview data from stakeholders in order to elucidate the existing hierarchical structure within the elite sport system, as well to document the connectedness/interaction of the policy instruments.

The Semi-Professional Team System (SPTS)

The Semi-Professional Team System first emerged after the country regained independence from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 (Kim and Noh Citation2013). The SPTS was used to develop elite athletes and played an important role in the success of the 1986 Seoul Asian Games and the 1988 Seoul Olympics (Kim and Noh Citation2013). Since that time, most private companies have focused on operating popular professional teams, such as baseball and soccer, to promote their companies.

However, a semi-professional team system linked with businesses/workplaces has also been run by a combination of: (1) the government and its agents (the six types of organisations noted above) and (2) private companies based on the ‘National Sports Promotion Act’. It is widely known that the SPTS is the most important instrument for the development of elite sport in Korea as it involves more athletes and coaches than the professional ranks (Kim and Noh Citation2013, Lim Citation2021). Indeed, as of 2022 there were 1,162 semi-professional teams including 520 representing local and municipal/provincial governments, 274 teams aligned with local and municipal/provincial branches of NSFs, 183 teams of local and municipal/provincial sports councils, 115 teams supported by private companies and 70 teams associated with public organisations (e.g. Korea Railroad Corporation and Korea Expressway Corporation) (Korean Sport and Olympic Committee Citation2022).

To this extent, semi-professional teams operate as farm or feeder systems for the elite sport system similar to how professional systems work internationally. However, there are some unique features of the Korean system. According to Choi et al. (Citation2021) and Lim (Citation2021), elite athletes and coaches are employed by government city halls and local sports councils as officials and full-time staff, albeit with notable differences compared with their ‘normal’ colleagues. One athlete described their work this way:

I am employed as an elite athlete of […] sports council. My colleagues and I don’t have desks and computers for office work, and we are just components of the council. All semi-professional athletes in Korean sports have the same conditions. We have to train all day for the sports council instead of performing administrative duties because we are employed primarily as athletes … We don’t go to the council on a regular basis, we just go there for contracts or education programmes once a year. I’ve never thought of myself as an office worker in the semi-professional team. I’m a just temporary athlete who gets paid by the council.

One key difference is that while most officials are permanent staff, semi-professional athletes and coaches have to renew their contracts every year based on their sport performance results (Noh Citation2012, Kim and Noh Citation2013). As one informant confirmed:

In the city hall, general semi-professional athletes have to renew their contracts once a year, but national athletes need to undergo contract renewal every two years, based on performance standards in the [National Sports] Festival and international competitions.

From the government’s point of view, the SPTS has played a significant role in maintaining a top 10 international ranking in the Summer and Winter Olympics (Lim et al. Citation2011). In particular, the SPTS serves as a means to develop elite athletes and maintain less popular sports such as skating and triathlon which have lower audience attendance rates. As staff member C of the NSFs observes:

Most athletes in less popular sports can go to a semi-professional team after graduating from high school and university. […] If the semi-professional team system wasn’t supported and administered by the government, most athletes would have to quit their careers as athletes.

In this regard, the SPTS is a central instrument to develop elite athletes and is now deeply entrenched as one of the unique institutional elements of Korean sport. Importantly, as a key instrument that shapes the political landscape of elite sport, the SPTS also features other more substantive tools (such as contract renewal processes) that have a more direct bearing on behaviours connected to maltreatment.

The Specialist Athlete System for developing student-athletes (SAS)

The Specialist Athlete System was implemented in 1972 and has had two distinctive objectives across five decades. First, the aim of the instrument has been to develop student-athletes as fast as possible via three particular incentives: (a) by progressing students from primary schools through to universities based on sport performance (winning medals) instead of academic performance; (b) by providing students with support via scholarships and equipment; and (c) by allowing students to focus on their training without distraction (Cho and Lee Citation2013). Illustrating these incentives, consider the reports of two athletes:

Student-athletes can get some benefits such as scholarships or funding, skate blades, shoes and sportswear from elementary school to university.

When I was a student-athlete, I focused only on training without studying and school classes. My peers and I trained as much as general students studied. It was normally over 8 or 9 hours per day.

The second objective of the SAS was to discover young talented student-athletes and guide them into the system. Importantly, elite student-athletes developed through the SAS can also be semi-professional athletes within the unique institutional elements previously described. Here, the simultaneous operation of instruments is indicative of a complementary policy mix in relation to elite athletes. For example, in the case of student-athletes in schools at least three conditions must be met to maintain their elite athlete status. First, most student-athletes have to join the SAS.Footnote4 Second, they have to live away from their parents in the collective sports training camps for intensive training.Footnote5 Third, they need to achieve medals/points from the National [Junior] Sports FestivalFootnote6 in order to progress from primary schools to universities or semi-professional teams.Footnote7 Likewise, in semi-professional teams, adult athletes have to live with their colleagues in the training camps to prepare for the NSF and other domestic/international competitions; and, medals/points from the festival and international games are the most important factors in the annual renewal of contracts. As a result, there are two systems in place: one for youth in schools and one for adults in the workplace, each supported by two instruments: the National [Junior] Sports Festival and the training camps. We now turn to those two instruments.

The National Sports Festival (NSF)

After Korean independence from Japanese colonial rule in 1945, the National Sports Festival, which is organised by the KSOC each October, emerged as the main event to unite Korean people and develop the then-poor country (Jung and Jin Citation2017). However, the role of the NSF was regularly altered by various military regimes to align with numerous political goals such as transforming the nation’s image, conveying an impression of superiority over North Korea, and strengthening national prestige via sport (Moon Citation2019). Given its goal to maintain a top 10 position in the Olympics (Nam-Gil and Mangan Citation2002, Choi et al. Citation2019), the NSF has been used to achieve rapid performance success over the past few decades (Jung and Jin Citation2017). Considered as ‘South Korea’s mini-Olympics’, it serves as a fundamental part of the elite sport system to discover talented athletes who wish to become national athletes (Chang et al. Citation2017, p. 319). Today, the NSF is the biggest and most important domestic competition for approximately 20,000 athletes (semi-professional, university and high school athletes) who compete across 50 sports and accrue points while representing 17 provinces and metropolitan cities. Importantly, the NSF is explicitly connected with the SPTS. For athletes, it is essential to perform well in the NSF given that it has a major impact on their contract and salary. As one athlete said:

The council only assesses the results of the NSF to renew contracts with athletes. If you do not win medals in the festival, they will not renew your contract or your salary would be cut.

Likewise, for semi-professional team coaches, success in terms of medals and points of their athletes in the NSF can substantially affect their contract negotiations (Lim et al. Citation2011). For example, only 20% of their evaluation for contract renewal is qualitative (i.e. scientific support and training programmes), whereas 80% is based on the performance standards (medals/points) of their athletes (Lee and Lee Citation2020, Oh et al. Citation2020). As shown in below, the significance of athletes’ achievements is considerable when coaches are assessed to renew their contracts.

Table 1. Assessment standard to renew contracts of head coaches and coaches/trainers in the semi-professional teams of the Goyang city hall (Source: Oh et al. Citation2020, p. 73).

While the NSF is explicitly linked with the SPTS’s process of contract renewal, the National [Junior] Sports Festival is also connected to, and complementary with, university and student-athlete development structures because it plays a role in their admission to university.

The Collective Sports Training Camps (CSTC) and National Training Centres (NTC)

The Collective Sports Training Camps were first introduced in 1972 to expedite the development of both student and adult elite athletes (Myung Citation2017). In Western nation-states, sports’ training camps are generally utilised to improve ‘training adaptation at specific times in the season’ (Saw et al. Citation2018, p. 1). However, in Korea, most student-athletes (from primary school to high school) and adult athletes must live in the training camps throughout their career and until they retire. In training camps, teachers and coaches maintain complete control over the life of all athletes for the purposes of: (1) increasing athletes’ mental strength; (2) inducing a military service-like culture defined by obedience and strict hierarchy; (3) providing intensive training; and (4) enhancing teamwork amongst athletes (Lee Citation2012).

According to Park et al. (Citation2011), the training camps succeeded in Korea reaching a top 10 position in the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympic Games because of the huge numbers of student and semi-professional athletes sacrificing their studies and freedom to focus solely on intensive training. In terms of its institutional significance, there have been media reports surrounding the incentive structure of the NSF. Specifically, one journalist reported that physical education teachers can be promoted to ‘principal’ faster than other teachers if their student-athletes win medals in the National [Junior] Sports Festival and other competitions (Cho Citation2019). This reward system is common knowledge amongst student-athletes and teachers, as identified in the following interview:

If a student-athlete wins medals in the competitions, teachers can obtain promotions. In my case, I won a gold and a bronze medal at the same time … when I was in elementary school. After that, a vice-principal became a principal in the school and the medals significantly contributed to their promotion.

Thus, while the training camps are an instrument to monitor and induce student-athletes to focus on training, they are further shaped and legitimised by stakeholders (principals, physical education teachers and coaches) within the SAS. And in this way, the training camps supplement and reinforce the system of incentives linking performance with pay.

The National Training Centres fulfil a similar linking function but are managed under the KSOC and are designed to improve the performance of about 1,200 national athletes (Ha and Son Citation2014). These centres have also played a significant role by providing residential facilities, various amenities and intensive training programmes for national athletes (Park and Lim Citation2015). As with the collective training camps, the National Training Centres are closely connected with the Specialist Athlete System and the Semi-Professional Team System to maintain their political position and legitimacy.

The interaction of policy instruments and maltreatment

If the mix of instruments is self-reinforcing and persistent, it follows that some mechanisms underlying athlete maltreatment might be entrenched inside the institutional structure of the elite sport system. Therefore, this section discusses how the interaction of policy instruments potentially leads to the occurrence of maltreatment. Here we draw upon interviews to give voice to key stakeholders but also to highlight the effect of policy mixes.

With respect to the Korean case, the government and its agencies effectively utilise policy instruments (and their associated rule structures) to maintain an elite sport system that is based on narrow political outcomes. For organisations and actors operating through these instruments, the interaction of rule structures has undoubtedly generated medal success; however, it may also have yielded unintended effects. Previous research for example, has shown that coaches and semi-professional teams apply enormous pressure on athletes to accrue points in the NSF so that they can retain contracts and secure government funding (Kim and Noh Citation2013, Han et al. Citation2021). In this way, the overall mix of the SPTS, including its salary structures and connection with the NSF potentially creates an environment susceptible to maltreatment. This susceptibility is further exacerbated by athletes perceiving few alternative options to sustain their careers as a result of the SAS. Drawing from Flanagan et al. (Citation2011) and Rogge and Reichardt (Citation2016), the connections between instruments effectively steer both student and adult athletes towards the same ends through an intentional design, creating both direct and indirect effects across organisations.

While the effects in this case are the coherent or aligned pursuit of elite results, the governing system and mix of policy instruments constrains actors to follow rules not only based on a ‘logic of consequence’ but also because the mix renders it difficult to imagine anything else – i.e. the ‘logic of appropriateness’ (March and Olsen Citation2011). In relation to the former, stakeholders’ actions are governed by an instrument mix that produces ‘clear prescriptions and adequate resources (i.e. it prescribes doable action in an unambiguous way)’ (March and Olsen Citation2011, p. 482). In relation to the latter, stakeholders in the elite sport system abide by rules established in order to be recognised as loyal members of the political community. Indeed athletes, parents, coaches and officials tend to accept the prescriptions as facts and thus rarely engage with, or think critically about, these policy instruments as part of the process to achieve their goals (Stinchcombe Citation2001). One way of conceptualising this phenomenon, as described by athlete G, is: ‘To go straight forward to win medals’ (10 December 2022). In other words, it is best to focus on sport, to avoid distractions and questioning the system.

Likewise, the SPTS’s reliance on residential camps appears to aggravate the problem. Consider the comments of one interviewee:

… many adult athletes in the SPTS experience various types of maltreatment within the collective training camps. This is because they live in the camps with their colleagues and can only go outside on weekends.

Perhaps more concerning is that these training camps appear to bring youth and adult athletes together potentially enabling maltreatment. This concern is highlighted by athlete F:

The relationship between seniors and juniors in the camp is very hierarchical and strict. So, if you don’t follow their instructions and orders, you can get hit a lot by them … I ran a lot of errands for my seniors when I was in [middle and high] school. There were no convenience stores [in the school] so I had to go to the stores to buy snacks for my seniors. Now, I have lived as the youngest in the semi-professional team for five years so I have done various types of physical labour such as cleaning the rooms, making food, washing the dishes, doing the laundry and running errands instead of seniors in the training camp. (June 12, 2022)

This mirrors research findings elsewhere, with Fortier et al. (Citation2020) noting that young athletes are vulnerable in the unique environment of sport because of ‘the demands of competition … and time spent in a distant training centre [camp]’ (p. 4). Huh et al. (Citation2020) research also suggests that the training camp is the most dangerous place where semi-professional athletes are abused by both coaches and seniors. Although elite athletes complain, they tend to react passively to the problem because of the hierarchical structure, collective atmosphere and personal consequences faced if they speak out (Han et al. Citation2021).

Notably, the second recommendation of the Korean Sport Reform Committee proposed the complete abolition of the Collective Sports Training Camps (operated from elementary school to high school including unconventional off-school camps) and suggested allowing only limited operation of dormitories targeting long-distance students (Kim and Jang Citation2022). Although a new policy in 2021 (see Article 11 of the ‘School Sports Promotion Law’) emphasised that – a school’s principal shall make efforts to eliminate regular training camps during a semester (School Sports Promotion Law Citation2021), while acknowledging that a training camp is a necessary occurrence for sports games – student-athletes are still subjected to a dangerous environment as illegal training camps continue to operate. As MCST staff member ‘A’ explains:

Most elementary and middle schools run the training camps illegally like unofficial camps around the school. This is because schools and coaches really want to run the camps to control student-athletes effectively.

In a similar vein, MoE official ‘B’ who manages the training camps of schools, explained a fresh problem emerging from the new policy as follows:

The training camps still exist out of official institutions. It is very dangerous for student-athletes who live in a villa or a flat with only their colleagues. Nobody checks the facility and teaches safety education for them, because it is an illegal collective training camp.

In this perspective, policy instruments tend to create their own logics of action because they have ‘inertial effects’ showing resistance to outside pressures and change (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007, p. 10). While training camps are run by school sport teams and semi-professional teams, KSOC’s National Training Centres have similar negative repercussions. As the NSF’s staff member ‘A’ expressed ‘they are trained within the closed training environments like a jail’ (30 April 2022) and in this environment, another reported:

… Athletes suffer mental distress. They cannot hang out with peers and share their problems because they are all rivals. Some athletes told their coaches about physical problems … but coaches said, ‘You should go home because there are many athletes wanting to become national athletes’.

Therefore, where the National Training Centres are also legitimated and reinforced by the wider mix of instruments, this vulnerability appears to be a tacitly endorsed and routinised phenomenon for adult national athletes. Indeed, the threat of expulsion (‘there are many athletes [willing to take your place]’) is rendered possible by the context of a highly complementary/reinforcing suite of policy instruments such as the SAS. The National [Junior] Sports Festival arguably shows a similar complementarity. As one NSF staff member ‘D’ highlights:

The festivals are the most important games for student-athletes and adult athletes to progress to universities and semi-professional teams … However, athletes endure coaches’ abusive language for the opportunity to participate in these festivals. I think it seems like the government created a structure that athletes have to endure in order to win medals.

In Korea, the SAS has served as the cornerstone of the elite sport system’s rapid growth for 50 years. However, its centrality and networks also create a range of conditions that may contribute to maltreatment. MoE official ‘A’ explained the problems as follows:

The SAS is the most fundamental problem. Because it leads to a win-at-all costs attitude, the collective training camp culture, excessive and long training, and the loss of right to education. […] Thus, coaches at school have great power that decides school, university and professional teams of athletes.

Although the interdependence of policy instruments appears to explain unwanted outcomes, the instruments’ interconnectedness arguably renders their continuation as ‘path dependent’ (Pierson Citation2000, Peters Citation2019). According to North (Citation1990), this persistence is sustained by interrelated ‘formal rules nested in a hierarchy’ because changing existing formal rules (policy instruments) incurs a social cost while requiring consensus (p. 83). Confirming this propensity, the MCST staff member ‘A’ suggests:

The government has retained the SAS for developing student-athletes based on the ‘School Sports Promotion Law’ … because officials, administrators and politicians want stability rather than a change in the system.

Given that public organisations tend to routinise their tasks and create standards for operational procedures, the instruments established by the government persist because of the forces of inertia created at the development phase (Peters Citation2019). Consider the perspective of MoE official ‘B’ about the potential impact of path dependency:

Stakeholders such as coaches, politicians/lawmakers, officials and administrators who experienced success as [former] elite athletes in the elite sport system have a vested interest to maintain the system. You know, they have still pursued these [policy] instruments to maintain an internationally prominent position in the Olympics. But, it is difficult to break the tradition of historical success within the system, so progressive thinkers in sport are unable to change the elite sport system.

Indeed, to maintain the elite sport system in Korea, ‘the National Sports Promotion Act has been revised by the MCST about 40 times in the last 60 years’ (MCST A, 26 February 2022).

Thus, drawing from Peters (Citation2019), the Korean elite sport system continues to operate as it does because the initial path is sustained by modifying existing instruments that create additional rigid layers within it. This is similar to developed Western countries’ elite sport systems, such as those in Australia and France, which tend to adhere to their original objective of sustaining higher medal standings in the Olympics (Houlihan and Zhenga Citation2016). On the one hand, policy instruments in the elite sport system attain ‘consistency’ and ‘coherence’ to generate positive lock-in effects by retaining robustness and resilience over time (Howlett Citation2019, p. 33). But on the other hand, the policy instruments have yielded unintended outcomes such as athlete maltreatment.

This finding raises an important question: why does bundling policy tools lead to unintended outcomes? As Tinbergen (Citation1952) notes, the mix of policy instruments is typically deployed to accomplish a specific policy objective that does not necessarily have to be limited to the use of a single instrument. Arguably, in such combinations, each instrument is not isolated from others and interacts, creating the possibility of negative conflicts ‘(one plus one is less than two)’ as well as synergies ‘(one plus one is more than two)’ (Howlett Citation2018, p. 252). In this case, the interaction of instruments within the Korean elite sport system has not only produced synergistic effects (e.g. maintaining a top 10 in the Olympics and national success via sport) but has also confronted negative effects, that is, athlete maltreatment.

Conclusion

In order to fill a gap in the literature on athlete maltreatment, this paper analysed the institutionalised mix of policy instruments in the Korean elite sport system. The findings indicate that these instruments as formal institutions are deployed to reach ‘overarching policy objectives’ and generate both intended and unintended outcomes. The hierarchical structure of the wider system has given rise to policy instruments that mutually reinforce the attainment of elite sport success. Indeed, the major policy instruments operate both via a ‘logic of consequence’ (e.g. in salary negotiations, promotions, and university admissions) and a ‘logic of appropriateness’ (e.g. there can be no alternative) (March and Olsen Citation2011). In this way, the interaction of various instruments simultaneously renders athletes vulnerable to maltreatment because the instruments reinforce the elite sport system, its incentive structures, and its singular pursuit of medal success.

The concept of a ‘policy instrument mix’ contributes to a broader understanding in relation to the complexity of institutional mechanisms (Kern and Howlett Citation2009). To achieve explicit political purposes and maximise effectiveness, the combination of instruments provides coherence and complementarity, thereby assisting in the maintenance of institutional structures and systems. In this process, the mix generates both intended and unintended effects within the elite sport system. Consequently, despite the Sport Reform Committee’s determined efforts to address the issue of maltreatment in the current Korean context, the main sport organisations have not adopted and acted upon the newly proposed safeguarding measures. This may in part be attributed to the committee’s approach of examining each instrument individually, which is unlikely to lead to effective solutions. In fact, the results of this study indicate that attempting to fix a single part of the elite sport system in isolation may inadvertently create new problems such as the emergence of ‘illegal’ training camps around schools and in private sport clubs (Choi Citation2023). Perhaps in recognition of this system-wide view, Kihl (Citation2023) proposes that sport integrity ‘systems’ of regulation require an understanding of their various parts, their interaction and interdependence. In light of these findings, this study calls for regular re-evaluation of the ongoing institutional causes of, and associated efforts to address, maltreatment in elite sport. Future research should thus investigate how athlete maltreatment in elite sport becomes entrenched and intertwined with other informal institutions (e.g. practices, narratives and culture) so as to gain a better understanding of the interplay between policy and society. On this point, we would re-affirm the need for more studies of maltreatment and its causes outside of Western contexts, such that new insights can be gleaned from particular state systems operating within long-standing cultural foundations (such as Confucianism).

Ethics approval

This research was reviewed by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (February 2022, Ethics Committee reference number 22/001).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The committee members consisted of five Vice-Ministers (the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST), the Ministry of Education (MoE), the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF), the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF) and the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, and 15 civilian experts (Sport, human rights, gender, disability, law and civil society) from February 2019 to January 2020 (Hong Citation2020).

2. After the secondary military government was awarded the bid to host the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics in 1981, presidents of Chaebols were appointed as NSF presidents with the directive to invest a significant amount of money into elite sport. At the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, out of the total 33 NSFs associated with Olympic events, 21 of them were led by Presidents of Chaebols (Park Citation2022).

3. This law enacted in August 2021 aims to promote the well-being of citizens, foster national development, and enhance social integration by specifying fundamental matters crucial for directing and implementing sport policies (Chae et al. Citation2015).

4. For a few popular sports (e.g. football), general students can be student-athletes through two tracks: the SAS and private sport clubs.

5. For an individual event such as skating, it is not necessary to live in the training camps.

6. The National Junior Sports Festival was first introduced in 1972 to develop elementary and middle school elite student-athletes.

7. Today, many student-athletes transfer directly to semi-professional teams after graduating from high school due to various factors including the requirement of military service (where athletes must enlist until the age of 28), short athletic careers, and potential income.

References

- An, J. and Jeoung, J., 2020. After the recommendation of the sports innovation committee, changes and choices in Taekwondo. The Korea journal of sport, 18 (4), 747–756. doi:10.46669/kss.2020.18.4.068.

- Béland, D. and Howlett, M., 2016. How solutions chase problems: Instrument constituencies in the policy process. Governance-an International journal of policy administration and institutions, 29 (3), 393–409. doi:10.1111/gove.12179.

- Bernard, H.R., 2017. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Taylor, J., and Herber, O.R., 2014. Vignette development and administration: a framework for protecting research participants. International journal of social research methodology, 17 (4), 427–440. doi:10.1080/13645579.2012.750833.

- Capano, G. and Howlett, M., 2020. The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. SAGE open, 10 (1), 2158244019900568. doi:10.1177/2158244019900568.

- Chae, J., Kim, S., and Hong, S., 2015. Study on reorganization of laws involving sports (Study on fundamental sports law through legal analysis of foreign sports law – focus on Germany). The Korean association of sports law, 18 (2), 11–48. doi:10.19051/kasel.2015.18.2.11.

- Chang, I.Y., Sam, M.P., and Jackson, S.J., 2017. Transnationalism, return visits and identity negotiation: South Korean-New Zealanders and the Korean national sports festival. International review for the sociology of sport, 52 (3), 314–335. doi:10.1177/1012690215589723.

- Cho, S., 2019. The problem of the sport’s collective training camp, The Pressian Times, October 24, 2019. Available from: https://www.pressian.com/pages/articles/262622.

- Choi, J., et al., 2021. Strategies for legal and institutional improvement for the vitalization of corporate-sponsored sports teams. Journal of Korean society of sport policy, 19 (3), 175–195. doi:10.52427/KSSP.19.3.12.

- Choi, Y., 2023. The sport reform after four years: the victims leave while the perpetrators remain Korea centre for investigative journalism, June 16, 2023. Available from: https://newstapa.org/article/vwc1o.

- Choi, S.A., Yun, D.J., and Kim, J.H., 2019. The reproduction of the life and violence of elite athletes. Korean journal of oral history, 10 (1), 247–291.

- Cho, N. and Lee, Y., 2013. Exploring alternative strategies on the basic concepts and realities of government-fostered student athletics policies. The Korean journal of elementary physical education, 19 (3), 151–164.

- Creswell, J.W., et al., 2007. Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The counseling psychologist, 35 (2), 236–264. doi:10.1177/0011000006287390.

- De Bosscher, V., et al., 2009. Explaining international sporting success: An international comparison of elite sport systems and policies in six countries. Sport management review, 12 (3), 113–136. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2009.01.001.

- Donnelly, P. and Kerr, G., 2018. Revising Canada’s policies on harassment and abuse in sport: A position paper and recommendations. Toronto.

- Elliott, R. and Timulak, L., 2005. Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research. In: J. Miles and P. Gilbert, eds. A handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. Oxford: Oxford university press, 147–159.

- Flanagan, K., Uyarra, E., and Laranja, M., 2011. Reconceptualising the ‘policy mix’ for innovation. Research policy, 40 (5), 702–713. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.005.

- Fortier, K., Parent, S., and Lessard, G., 2020. Child maltreatment in sport: smashing the wall of silence: a narrative review of physical, sexual, psychological abuses and neglect. British journal of sports medicine, 54 (1), 4–7. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100224.

- Fossey, E., et al., 2002. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry, 36 (6), 717–732. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x.

- Gailmard, S., 2009. Discretion rather than rules: choice of instruments to control bureaucratic policy making. Political analysis, 17 (1), 25–44. doi:10.1093/pan/mpn011.

- Green, M. and Houlihan, B., 2005. Elite sport development: policy learning and political priorities. London: Routledge.

- Han, S.W., Yoo, H.M., and Huh, J.H., 2021. A phenomenological study on the human rights violation experience of semi-professional athletes at workplace. Korean journal of sport science, 32 (3), 391–402. doi:10.24985/kjss.2021.32.3.391.

- Ha, J.H. and Son, H., 2014. A study on the historical value of Taereung Seonsuchon, Korean Elite Sports Mecca. Korean journal of physical education, 53, 1–9.

- Hong, D., 2020. Establishing new sports paradigm and future task through the sports reform committee policy documents analysis in South Korea. The Korean journal of physical education, 59 (2), 285–302. doi:10.23949/kjpe.2020.3.59.2.285.

- Houlihan, B. and Zhenga, J., 2016. The Olympics and elite sport policy: where will it all end? In: F. Hong and L. Zhouxiang, eds. Delivering olympic and elite sport in a cross cultural context. London: Routledge, 1–18.

- Howlett, M., 2018. The criteria for effective policy design: character and context in policy instrument choice. Journal of Asian public policy, 11 (3), 245–266. doi:10.1080/17516234.2017.1412284.

- Howlett, M., 2019. Procedural policy tools and the temporal dimensions of policy design. Resilience, robustness and the sequencing of policy mixes. International review of public policy, 1 (1), 27–45. doi:10.4000/irpp.310.

- Howlett, M., 2020. Policy instruments: definitions and approaches. In: G. Capano and M. Howlett, eds. A modern guide to public policy. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, 165.

- Huh, J.H., Kim, E.J., and Ko, K.H., 2020. Research on the human rights violation of semi-professional athletes in the workplace. Korean journal of sport science, 31 (4), 728–744. doi:10.24985/kjss.2020.31.4.728.

- Human Rights Watch, 2020. “I was hit so many times I can’t count” Abuse of child athletes in Japan [online]. Human Rights Watch. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/20/i-was-hit-so-many-times-i-cant-count/abuse-child-athletes-japan# [Accessed 24 July 2022].

- Jung, M.H. and Jin, Y.S., 2017. Significance and transition of the National Athletic Competition. Korean journal of physical education, 56 (1), 1–10. doi:10.23949/kjpe.2017.01.56.1.1.

- Kavanagh, E., et al. 2020. Managing abuse in sport: An introduction to the special issue. Sport management review, 23 (1), 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.002.

- Kern, F. and Howlett, M., 2009. Implementing transition management as policy reforms: a case study of the Dutch energy sector. Policy sciences, 42 (4), 391–408. doi:10.1007/s11077-009-9099-x.

- Kerr, G., Battaglia, A., and Stirling, A., 2019. Maltreatment in youth sport: A systemic issue. Kinesiology review, 8 (3), 237–243. doi:10.1123/kr.2019-0016.

- Kihl, L.A., 2023. Development of a national sport integrity system. Sport management review, 26 (1), 24–47. doi:10.1080/14413523.2022.2048548.

- Kim, H.B. and Jang, S.H., 2022. The perception of people in sports field on the recommendations of the sports innovation committee. Korean journal of convergence science, 11 (5), 81–102. doi:10.33645/cnc.2022.04.44.4.81.

- Kim, K.H. and Noh, Y.Y., 2013. Improving semi-professional sport teams and policy suggestions to build effective sport ecosystem. The Korean society for sport management, 18 (4), 35–54.

- Korean Sport and Olympic Committee, 2022. Sport support portal. Seoul: Korean sport & olympic committee. Available from: https://g1.sports.or.kr/index.do [Accessed 6 December 2022].

- Korean Sport and Olympic Committee, 2023. Organisational charts [online]. Korean Sport & Olympic Committee. Available from: https://www.sports.or.kr/home/020102/0050/main.do [Accessed 30 November 2022].

- Lascoumes, P. and Le Galès, P., 2007. Introduction: Understanding public policy through its instruments - from the nature of instruments to the sociology of public policy instrumentation. Governance-an International journal of policy administration and institutions, 20(1), 1–21: doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00342.x.

- Lee, Y.S., 2012. Camp training realities of school athletic club and improvement plan. Journal of Korean society of sport policy, 10 (2), 93–107. doi:10.52372/kjps10005.

- Lee, C.H. and Lee, Y.S., 2020. A study on the development of the performance evaluation for elite athletics and coaches in Goyang-si athletic departments. Journal of Korean society of sport policy, 18 (4), 123–140. doi:10.52427/KSSP.18.4.8.

- Lim, D., 2021. An analysis of swimmer’s ethical consciousness and solutions to revitalizing business swimming teams in South Korea. Journal of sport ethics, 1 (1), 79–97.

- Lim, S.M., Lee, K.M., and Kim, J., 2011. Women’s semipro tennis, what is the problem?: Problem exploration for the vitalization of women’s semipro tennis. Korean journal of physical education, 50 (6), 103–112.

- Lowndes, V. and Roberts, M., 2013. Why institutions matter: the new institutionalism in political science. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P., 2006. Elaborating the ‘new institutionalism. In: R. Rhodes, S. Binder, and B. Rockman, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–20.

- March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P., 2011. The logic of appropriateness. In: R. Goodin, ed. Political science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–20.

- Mcmahon, J., Mcgannon, K.R., and Palmer, C., 2022. Body shaming and associated practices as abuse: athlete entourage as perpetrators of abuse. Sport, education and society, 27 (5), 578–591. doi:10.1080/13573322.2021.1890571.

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, 2019. The sport reform committee 1th written advice [ online]. Ministry of culture, sports and tourism. Available from: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_notice/press/pressView.jsp?pSeq=17269 [Accessed 29 March 2023].

- Moon, K.S., 2019. The significance of 100th Korean national sports festival and a plan introduction for sport business. Korean journal of sports science, 28 (6), 653–670. doi:10.35159/kjss.2019.12.28.6.653.

- Mountjoy, M., et al., 2016. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British journal of sports medicine, 50 (17), 1019–1029. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121.

- Myung, W., 2017. The socio-cultural background and the current issues of camp training system in school sport. Korean journal of sport science, 28 (3), 592–607. doi:10.24985/kjss.2017.28.3.592.

- Nam-Gil, H. and Mangan, J.A., 2002. Ideology, politics, power: Korean sport-transformation, 1945-92. The International journal of the history of sport, 19 (2–3), 213–242. doi:10.1080/714001746.

- Noh, S.O., 2012. From the 5 Korean medallists in the Olympics, 3 were semi-professional athletes: their salaries were evaluated based on their performance Maeil Business News Korea, 20 August. Available from: https://www.mk.co.kr/economy/view/2012/523598.

- North, D.C., 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- Oh, J.S., et al. 2020. Development of the performance in Goyang-si semi-professional team system. Available from: https://www.gplib.kr [Accessed 13 March 2023].

- Pacheco-Vega, R., 2020. Environmental regulation, governance, and policy instruments, 20 years after the stick, carrot, and sermon typology. Journal of environmental policy & planning, 22 (5), 620–635. doi:10.1080/1523908x.2020.1792862.

- Parent, S. and Fortier, K., 2018. Comprehensive overview of the problem of violence against athletes in sport. Journal of sport & social issues, 42 (4), 227–246. doi:10.1177/0193723518759448.

- Park, C.M., 2022. The names, both prominent and unknown of corporate owners who have taken up positions in NSFs The SisaJournal. Available from: https://www.sisajournal.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=240954 [Accessed 2 May 2023].

- Park, C., Lee, J., and Lee, B., 2011. The collective training camp in a university elite boxing team: A cultural approach. Korean society for sport anthropology, 12 (0), 54–66.

- Park, J.-W. and Lim, S., 2015. A chronological review of the development of elite sport policy in South Korea. Asia pacific journal of sport and social science, 4 (3), 198–210. doi:10.1080/21640599.2015.1127941.

- Peters, B.G., 2002. The politics of tool choice. In: M.L. Salamon, ed. The tools of government: a guide to the new governance. Oxford and New York: Oxford university press, 552–564.

- Peters, B.G., 2019. Institutional theory in political science: the new institutionalism. 4th ed. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pierson, P., 2000. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. The American political science review, 94 (2), 251–267. doi:10.2307/2586011.

- Roberts, V., Sojo, V., and Grant, F., 2020. Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport management review, 23 (1), 8–27. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2019.03.001.

- Rogge, K.S. and Reichardt, K., 2016. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: An extended concept and framework for analysis. Research policy, 45 (8), 132–147. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.04.004.

- Salazar-Morales, D.A., 2018. Sermons, carrots or sticks? Explaining successful policy implementation in a low performance institution. Journal of education policy, 33 (4), 457–487. doi:10.1080/02680939.2017.1378823.

- Sam, M., 2012. Targeted investments in elite sport funding: Wiser, more innovative and strategic? Managing leisure, 17 (2–3), 207–220. doi:10.1080/13606719.2012.674395.

- Saw, A.E., Halson, S.L., and Mujika, I., 2018. Monitoring athletes during training camps: observations and translatable strategies from elite road cyclists and swimmers. Sports, 6 (3), 63. doi:10.3390/sports6030063.

- Schmidt, V.A., 2010. Taking ideas and discourse seriously: explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’. European political science review, 2 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1017/S175577390999021x.

- School Sports Promotion Law, 2021. School Sports Promotion Law [online]. Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=56583&type=sogan&key=2 [Accessed 27 April 2023].

- Scott, W.R., 2013. Institutions and organizations: ideas, interests, and identities. London: Sage publications.

- Serbruyns, I. and Luyssaert, S., 2006. Acceptance of sticks, carrots and sermons as policy instruments for directing private forest management. Forest policy and economics, 9 (3), 285–296. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.06.012.

- Shon, S.J., 2019. Improvements of legal institution for the development of sports system in Korea: focusing on the capacity enhancement of sports organizations. The journal of sports and entertainment law, 22 (2), 67–88.

- Song, M.K., 2018. A study on the financial independence of sports organizations: Focusing on Korea Sport and Olympic Committee. The journal of sports and entertainment law, 21 (1), 3–19.

- Stinchcombe, A.L., 2001. When formality works: authority and abstraction in law and organizations. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Stirling, A.E., 2009. Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British journal of sports medicine, 43 (14), 1091–1099. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433.

- Stirling, A.E. and Kerr, G.A., 2014. Initiating and sustaining emotional abuse in the coach-athlete relationship: an ecological transactional model of vulnerability. Journal of aggression maltreatment & trauma, 23 (2), 116–135. doi:10.1080/10926771.2014.872747.

- Tinbergen, J., 1952. On the theory of economic policy. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Verschuuren, P. and Ohl, F., 2023. Can the credibility of global sport organizations be restored? A case study of the athletics integrity unit. International review for the sociology of sport, 58 (7), 1193–1213. doi:10.1177/10126902231154095.

- Voß, J.-P. and Simons, A., 2014. Instrument constituencies and the supply side of policy innovation: The social life of emissions trading. Environmental politics, 23 (5), 735–754. doi:10.1080/09644016.2014.923625.

- Willson, E., et al., 2022. Listening to athletes’ voices: national team athletes’ perspectives on advancing safe sport in Canada. Frontiers in sports and active living, 4 (840221). doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.840221

- Yin, R.K., 2009. Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks: sage.

- Yoo, H.-W. and Kang, H.-M., 2017. A study on the present condition and future of public finance in the field of sport. Journal of Korean society of sport policy, 15 (2), 115–129.