?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Business and skills training programmes have been a popular social policy intervention to increase productivity of the self-employed in developing countries. We study the Small Business of the Family Economy programme, a government business training programme designed to assist Nicaraguan self-employed workers. Using data from three rounds of the Nicaragua Living Standards Measurement Survey, we employ a difference-in-differences strategy to exploit variation in eligibility for the programme across time and economic activity. Our estimates indicate that the programme does not increase self-employed workers’ earnings overall. However, we find heterogeneous treatment effects for female self-employed workers with low educational attainment, which could be explained by increased working months and having a second job.

1. Introduction

In developing countries where wage and salary employment are limited, self-employment is common and accounts for a sizeable portion of the labour force (Fields Citation2019; Gindling and Newhouse Citation2014). However, self-employed workers often face a multitude of challenges that can impede their economic growth. These challenges include limited access to financial resources, inadequate business training and skills, a lack of social protection, and limited bargaining power in the market. Without government intervention, self-employed individuals may struggle to overcome these obstacles, leading to a perpetuation of poverty and income inequality. Therefore, governments often implement various policies and programmes to support and empower self-employed workers. Typical self-employment policies include microfinance (loan), cash transfer (grant) and technical (vocational) and business (managerial) training programmes (Cho and Honorati Citation2014).

One of the most popular approaches among these social programmes has been microfinance, which is based on the premise that a lack of access to financial capital is a barrier to small-scale business development. Early evidence from non-randomised microfinance evaluations generally reported positive effects, particularly for the extremely poor (Khandker Citation2005; Pitt and Khandker Citation1998). However, recent experimental evaluations of microfinance have found no or mixed effects on microenterprise and earnings growth (Banerjee, Karlan, and Zinman Citation2015). Six randomised microfinance studies conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bruhn and Zia Citation2013), Ethiopia (Tarozzi, Desai, and Johnson Citation2015), India (Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster, and Kinnan Citation2015), Mexico (Angelucci, Karlan, and Zinman Citation2015), Mongolia (Attanasio et al. Citation2015), and Morocco (Crépon et al. Citation2015) show that microfinance positively affects self-employment activities, but it has no significant impact on profits or overall household earnings.Footnote1

Although there is still optimism about the power of financing support (especially grant type) for microenterprises (Blattman and Dercon Citation2018; Blattman, Fiala, and Martinez Citation2013), awareness that business success may depend on non-financial services (e.g. business training) and non-traditional training (e.g. gender-oriented training for women and psychology-based training programmes) is increasing (Arráiz, Bhanot, and Calero Citation2019; Campos et al. Citation2017; McKenzie and Puerto Citation2021). The related literature investigates the combined effects of financial capital and business training and reports mixed results on profits and earnings ranging from no effects (Bjorvatn and Tungodden Citation2010; Giné and Mansuri Citation2021; Karlan and Valdivia Citation2011) to dissipating short-term effects (De Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff Citation2014) or long-term effects (Berge, Bjorvatn, and Tungodden Citation2015).Footnote2

Due to the mixed results about business training on self-employment, it is difficult to draw consistent policy implications for supporting self-employment, and more evidence in different settings and contexts is required. Furthermore, most previous studies on business training are based on the loan clients of microfinance institutions (MFIs) who were willing to participate in business training. Those who obtain loans from MFIs may be systematically different from the average self-employed workers (Beaman et al. Citation2014), and this endogenous selection into credit markets makes it even more challenging to generalise the findings of randomised business training evaluations beyond MFI clients.

This paper examines the Nicaraguan government’s social programme to encourage self-employment using a quasi-experimental approach with a representative sample of self-employed workers. We investigate the effects of Nicaragua’s Small Business of the Family Economy (SBFE) programme, which aims to improve the capabilities of self-employed workers by providing business training and information and skill development in five sectors: agriculture, forestry, manufacturing, commerce and services, and construction. We use nationally representative data from the Living Standards Measurement Survey (LSMS) which was conducted by the National Institute of Development Information of Nicaragua. We estimate intent-to-treat effects using a difference-in-differences method in which we exploit variation in the timing of the introduction of the SBFE programme and the programme eligibility.

Our estimates indicate that the SBFE programme does not increase the overall earning of self-employed workers. This is consistent with the findings of Cho and Honorati (Citation2014) who report that various entrepreneurship programmes do not immediately translate into increased earning. In contrast, we find strong heterogeneous treatment effects for female self-employed workers with low educational attainment. The SBFE programme is associated with a 14.5% increase in female self-employment earnings for those with primary education or less, and an 18.3% increase for those with secondary education. These heterogeneous treatment effects are also consistent with previous research that found a positive impact of business training on the profits of female-run microenterprises (Arráiz, Bhanot, and Calero Citation2019; Bruhn and Zia Citation2013; Bulte, Robert, and Nhung Citation2017; McKenzie and Puerto Citation2021).Footnote3

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the SBFE programme and its policy context. Section 3 describes the data, and Section 4 defines the eligibility status and presents the empirical strategy. Section 5 discusses the programme’s effects on self-employed workers’ earning with heterogeneous treatment effects and robustness checks. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. The SBFE Programme

The main goals of Nicaragua’s Ministry of Family Economy, Community, Cooperative, and Associative (Ministerio de Economía Familiar, Comunitaria, Cooperativa, y Asociativa, MEFCCA) is to promote and support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and the commercialisation of their products, to improve the quality and productivity of those businesses. The establishment of this ministry marked a shift towards the inclusion of self-employed individuals in the Government’s social programmes. In 2012, the MEFCCA and the National Institute of Technology (Instituto Nacional de Tecnología, INATEC) launched the SBFE, formerly known as the ‘Micro, Pequeña y Mediana Empresa’ programme.Footnote4The SBFE programme was designed to target individuals who want to develop or start their own business; they are mostly self-employed workers of SMEs in the agriculture, forestry, manufacturing, commerce and services, and construction sectors.

The SBFE programme aims to improve and strengthen the capabilities of self-employed workers through training and the establishment of sustainable businesses.Footnote5 It offers four types of training: (1) business plans; (2) business organisation; (3) networking, virtual store establishment, and access to new markets; and (4) administrative techniques. Three features differentiate this programme from previous traditional business training programmes.

Firstly, the SBFE programme encouraged female self-employed workers to participate, emphasising their importance as economic agents in the local economy where the programme was implemented.Footnote6 Secondly, the programme included a local customisation component that allowed participants to become more immersed in their local market and gain better experience and knowledge about their potential customers. Thirdly, the SBFE programme’s treatment intensity was significantly higher than that of most previous business training programmes in other contexts because it included a three-month training (100 hours total) and follow-up strengthening tutoring (4 hours).Footnote7

The SBFE programme ensured that all participants developed business development plans to market their SMEs, and facilitated small business registration through the MEFCCA’s information system. The aim is to improve the corporate image of SMEs while also facilitating access to local markets for their products.

3. Data

To examine the impact of the SBFE programme on the self-employed workers’ earning, we use the survey data from the LSMS, a national survey that covered urban and rural areas across several years. For data collection, the country was divided into census segments, each of which contained approximately 150 urban households and 120 rural households. Since the SBFE programme was launched in 2012, we consider the 2009 and 2014 waves to be the programme’s pre-intervention and post-intervention periods, respectively, and by analysing the 2005 and 2009 waves also, we are able to check the parallel trend assumption.

Our main sample includes only self-employed workers. A self-employed person is a respondent who self-identified as self-employed and who reported their primary activity during the previous week of the survey interview to be in a SMEs that did not involve hiring any workers. We do not include those self-employed workers or unpaid family workers who reported self-employment as the second or third occupation. Furthermore, we restrict our sample to self-employed workers aged 14 and up, which is the legal working age in Nicaragua and the minimum age required to participate in the SBFE programme.

compares the characteristics of self-employed and paid-employed workers in the LSMS samples for 2005, 2009, and 2014. We consider all workers just for comparison but the sample for evaluation includes only self-employed workers. In Panel A, 54% of the self-employed sample are male, with an average age of 39 years and 6.5 years of education; 65% live in urban areas, and 70% qualify for the SBFE programme. The key variable, self-employment eligibility status, remains stable across survey years (71% in 2005, 69% in 2009, and 69% in 2014), whereas real earnings increase (1,683 in 2005, 2,354 in 2009, and 2,493 in 2014). Compared to paid-employed workers in Panel B, self-employed workers are older, less educated, and less likely to live in urban areas with lower earnings.

Table 1. Summary statistics for self-employed and paid-employed workers in the LSMS.

4. Empirical strategies

This section explains the eligibility for the SBFE programme and presents the empirical strategies.

4.1. Eligibility status

The programme eligibility variable is taken from the following survey question: ‘What is the main economic activity of your occupation or the place you work?’ Using the CUAEN (Clasificador Uniforme de las Actividades Económicas de Nicaragua), we coded the responses into 104 economic activities for self-employed workers, of which only 50 are eligible for the SBFE programme. presents all economic activities for all years using the 3-digit CUAEN codes.

Programme eligibility which depends on a worker’s current employment is not randomly assigned, and this non-randomness is evident from the significant differences between eligible and non-eligible people in terms of demographic and socioeconomic covariates, as well as pre-intervention earnings level. Thus, we employ a propensity score matching (PSM) method to construct a valid comparison group to the treatment group of interest.Footnote8

The propensity score in this study is a conditional probability of being eligible for the treatment, given a set of observable covariates. The PSM estimator contains two identifying assumptions: unconfoundedness and overlap. The first assumption means that the differences in outcomes between treatment and control groups are attributed to the intervention as follows: , where

and

are potential outcomes for each individual I, D is the assignment, and X are covariates. This implies that the selection into treatment is based only on observable factors, and that

and

are independent of treatment D once we account for observed characteristics, allowing us to estimate the average treatment effect (Caliendo and Kopeinig Citation2008; Rosenbaum and Rubin Citation1983). The second assumption is also known as the condition of common support, which can be expressed as

. This assumption implies that all individuals with the same values of X are eligible to participate in the programme (Heckman, LaLonde, and Smith Citation1999). Since we cannot determine whether the individual was treated or not by the SBFE programme, we rely on intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. ITT analysis suggests an unbiased lower-bound of the treatment effect free of non-compliance, withdrawal, and protocol deviation of the individuals (Gupta Citation2011).

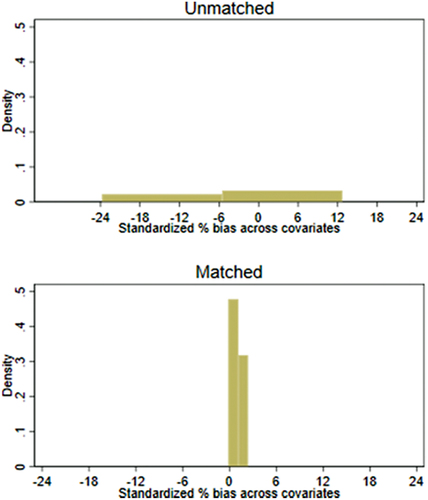

shows the differences between the eligible and ineligible groups. These two groups have significant differences in gender, age, household size, area of residency, secondary completed or less, and real earnings. Thus, we use variables of gender, age, household size, education, and area of residency (rural or urban) to implement full Mahalanobis matching using the 10 nearest neighbours without a calliper. After the matching, all covariates (Panel A) and pre-intervention real earnings (Panel B) become balanced between the eligible and non-eligible groups. We also plot the bias correction in Appendix using the standardised percent of bias across the key covariates reported in Panel A (Caliendo and Kopeinig Citation2008). After the PSM is applied, the standardised bias across covariates is within 0% in contrast to the unmatched sample. All of the estimations presented in the following sections are based on the matched sample.

Table 2. Test for equality of means for the pre-intervention variables.

4.2. Identification strategy

When both the unconfoundedness and overlap assumptions are satisfied, the treatment assignment is independent of a vector of covariates . But the efficacy of a PSM design depends mostly on how well the observed variables determine programme participation. If the treatment assignment is influenced by unobserved factors, the PSM will still provide a biased estimate. This concern about selection bias can be alleviated by using a difference-in-differences (DID) approach which eliminates unobserved, time-invariant factors that may affect the outcome variable (Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd Citation1997). Thus, our main empirical strategy employs a standard DID method, taking advantage of variations in the timing of the programme’s introduction and eligibility for the SBFE programme. As a result, our identification strategy is two-pronged. First, it is based on the difference in exposure before and after treatment among eligible self-employed workers. Second, our estimation includes other changes that may be occurring across the country, affecting the corresponding control groups who were not eligible for the SBFE programme.

The following is the baseline estimating equation:

where is the outcome variable (mainly, real earnings) for individual i, which is the logarithm of the real earnings;

is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if individual i is eligible for the SBFE programme and 0, otherwise;

is another dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the period is 2014 and 0 if it is 2009. Thus,

represents the coefficient of interest that shows the effect of the SBFE programme given the interaction between Post and Eligibility.

is a vector of individual characteristics that may affect earnings, including gender, age, household size, years of education, and area of residence, as summarised in .

is a regional fixed-effect that absorbs geographically restricted shocks affecting the real earnings of self-employed workers; and

is occupational fixed effects. Meanwhile,

is a letter-code economic activity fixed effect that absorbs non-observable, time-invariant, sector characteristics, and

is the error term clustered at eighteen letter-code activities by year.

Although we combine the DID approach with the PSM and include a comprehensive list of control variables, our estimates may be biased if the eligibility measure captures other variables relevant to the outcomes, such as eligibility for other social programmes and sectoral changes over time. However, the following factors may help to alleviate this concern.

First, the MEFCCA and INATEC implemented a number of social programmes, but they were limited in coverage and did not directly target self-employed workers. Unlike other Latin American countries, the Government of Nicaragua did not implement conditional cash transfer programmes or other social programmes to assist self-employed workers in the sectors targeted by the SBFE programme during the time of this study (The World Bank Citation2017). Other social programmes, such as Hambre Cero, Merianda Escolar, Proyecto Agora, and Programa Amor were poverty-alleviation programmes that targeted mostly children, women, the elderly, and people with disabilities. To the best of our knowledge, there were no other similar and contemporaneous programmes that could potentially influence our SBFE programme estimates.

Second, potential estimation bias from the sector-wide changes over the period could be alleviated because we use within-sector variations among 104 economic activities in the five eligible sectors. In addition, one might be concerned with the sectoral patterns in the 50 economic activities eligible for the SBFE Programme before and after the implementation. However, the composition of the eligible status of those economic activities using their CUAEN letter code did not significantly change. For example, the economic sector of agriculture, hunting, and forestry had about 34.8 % of all workers in 2005, 35.4% in 2009, and 32.4% in 2014 (CEDLAS Citation2022). Likewise, the overall composition of the self-employed did not change during the sample period. The percentage of self-employed workers is consistent across years; approximately 31% of all workers in the LSMS were self-employed workers.

4.3. Parallel trend assumption test

The key assumption for justifying the DID method is that real earning trends in the eligible and non-eligible groups would have been the same in the absence of the programme. Using the pre-intervention samples from 2005 and 2009, we run Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) , which considers 2005 to be the pre-period of the SBFE programme and 2009 to be the post-period. Given that the SBFE was implemented in 2012, we anticipate that the interaction between Post and Eligibility will not be significantly different from zero.

shows the estimates of the parallel trend test with the matched sample. Column (1) contains estimates with no controls. Individual controls are included in column (2). Column (3) also accounts for regional fixed effects, which capture the significance of geographical differences in real earnings. Columns (4) and (5) show the estimates with occupation and letter-code fixed effects. Overall, the estimates in all specifications are not statistically significant, and including a different set of controls has no differential effect on the estimates. These findings support the robustness of the DID model’s parallel trend assumption in this context.

Table 3. Test for parallel trends between 2005 and 2009.

5. Results

5.1. Estimating the effect of the SBFE on earnings

We now turn to the DID estimates from the 2009 and 2014 LSMS waves using a sample of self-employed workers. summarises our main findings, with columns (3), (6), and (9) representing the specifications described in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) . Overall, the estimates from the Post × Eligibility variable indicate that the introduction of the SBFE has no statistically significant impact on the earning of self-employed workers. This finding is similar to that of Cho and Honorati (Citation2014), who reviewed different entrepreneurship programmes and showed that those programmes had no immediate impact on earnings. While the SBFE programme also does not have a positive impact on the earnings of all self-employed workers (column 3), it increased the earnings of female self-employed workers by 7.5 percent (column 6). Considering the negative coefficient of the Post variable, the positive impact on females can be interpreted as the SBFE programme offering a measure of protection against the adverse trend for self-employed women. This result suggests the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects by gender.Footnote9

Table 4. Impact of SBFE programme on earnings.

Although the Eligibility variable is not our main interest here, it is noteworthy that the significant coefficients of the Eligibility variable do not necessarily imply inconsistency with the results in where the eligible and non-eligible groups in the matched sample were balanced across various covariates including earnings. Since we use variables of gender, age, household size, education and area of residency as the matching covariates, introducing occupation fixed effects or letter-code fixed effects in our estimation may change the balance in earnings between the eligible and non-eligible groups. Furthermore, the PSM method was applied for the whole sample, and as such, the balance within sub-groups categorised by gender may exhibit different results.

5.2. Heterogeneous treatment effects

One possible explanation for the heterogeneous treatment effects is the educational attainment of self-employed workers. To examine the effects of the SBFE programme by education level, we divide the sample into three mutually exclusive sub-groups: (1) those with primary education or below (no education up to 6 years of schooling); (2) those with secondary education (between 7 and 11 years of schooling); and (3) those with higher than secondary education (12 years of schooling or above). shows that the programme effect is highest among those with low educational attainment. The SBFE programme is associated with 14.5% (column 2) and 18.3% (column 5) earning increases for female self-employed workers with primary and secondary education, respectively, whereas there is no programme correlation for those with higher education (columns 7–9). Female self-employed workers are driving these disparate programme impacts. We do not find any significant association for males regardless of their educational attainment. In addition, we find no significant correlation between female self-employment and higher educational attainment (column 8).

Table 5. Heterogeneous treatment effects by educational attainment.

These findings are consistent with those of Arráiz et al. (Citation2019) and Bruhn and Zia (Citation2013) who reported that a large part of the programme impact comes from the treatment effect on female self-employed workers rather than from male workers. Moreover, the overall magnitude aligns with the findings of McKenzie and Puerto (Citation2021), indicating an increase of 15.4% in profits over a three-year period in Kenya. This result falls within the confidence interval of other studies reviewed in McKenzie and Woodruff (Citation2014). In contrast, related literature indicates that female-run microenterprises do not have significantly more profits in the Dominican Republic (Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar Citation2014), India (Field, Jayachandran, and Pande Citation2010), Pakistan (Giné and Mansuri Citation2021), Peru (Karlan and Valdivia Citation2011), and Tanzania (Berge, Bjorvatn, and Tungodden Citation2015).

Although previous studies used a randomised field experiment design, ensuring their results’ internal validity, their study samples were drawn primarily from loan clients of partner MFIs who were interested in participating in a business training programme. We analyse instead self-employed workers from representative samples regardless of their microcredit-taking status and personal interest in receiving business training. Thus, the discrepancy between our findings and previous findings could be attributed to a trade-off between sample representativeness and internal validity.

We also investigate whether age is a source of heterogeneity. In the 2009 and 2015 LSMS waves, the median age of self-employed workers was 39 years old. shows that the SBFE programme is associated with an 11.3% more of earnings for the female self-employed workers who were under the median age (at the 1% significance level). We find no significant relationship between the programme and the earning of male self-employed workers of any age.

Table 6. Heterogeneous treatment effects by age category.

5.3. Falsification test

A falsification test can be used to test the heterogeneous treatment effects of education on female self-employed workers. We estimate Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) using only paid-employed workers who were not eligible for the SBFE programme. We expect the estimates to be statistically insignificant because paid-employed workers were not eligible for the programme. shows that the programme has no effect on paid-employed workers regardless of gender or education level. In all heterogeneity analyses, the estimates from this falsification test are small in magnitude and statistically insignificant.

Table 7. Falsification test on paid-employed workers between 2009 and 2014.

5.4. Possible mechanisms for the programme impact

Finally, we examine possible effect channels such as whether an individual has received any other formal training in the previous 12 months, the number of working months, and the likelihood of having a second job to explain the positive programme impact on the earning of female self-employed workers. We find that 3.6% of the self-employed sample received formal training in the previous 12 months,Footnote10 and that self-employed workers worked 10.5 months per year, on average, with 9.7% holding down a second job.

displays the results for these outcomes. We find no significant impact of the SBFE programme on these variables in the overall sample (Panel A). However, Panel B clearly shows that female self-employed workers were more likely to work 0.5 more months and also 5 percentage points (51%) more to have a second job. Meanwhile, Panel C reports that none of these possible channels are statistically significant (at the 5% level) for male self-employed workers except for training. These findings indicate that female self-employed workers improved their earning by extending their working months and diversifying their job portfolio.

Table 8. Possible mechanism for the SBFE programme impact.

One possible reason for the observed increase in labour supply among female self-employed workers, particularly those with low education, may be attributed to their comparatively shorter work periods during the pre-trend period. shows that females self-employed workers an average worked 10.2 months, while their male counterparts worked slightly longer, with an average of 10.6 months, while the probability of having a second job was 8.8% for females compared to 10.0% for males. This disparity in the duration of work and second-job likelihood suggests that females, especially those with lower educational attainment, had more room for expanding their labour supply and diversifying their job portfolios.

An alternative channel through which the programme could have influenced outcomes is by enhancing labour productivity. The programme included components of business planning, goal setting, and financial education for self-employed workers which implies a potential impact on productivity. While our analysis does not incorporate specific proxy variables to directly measure labour productivity, we acknowledge the plausible association between the programme’s components and enhanced productivity. Female self-employed workers with low education attainment, who may have faced greater challenges in business management and planning, may have benefited more significantly from these elements, leading to improved productivity.

In summary, the observed differential impact on low-education females in terms of increased labour supply and potentially enhanced productivity may be linked to their initial work patterns and the specific components of the programme addressing aspects of business management.Footnote11

6. Discussion and conclusion

Self-employed workers are frequently regarded as the dominant form of economic activity in developing countries such as Nicaragua, so the potential benefits of policies that improve the earnings of self-employed workers is large. We find that the SBFE programme is associated with higher earnings for female self-employed workers, especially for those with lower educational attainment, and for younger cohorts. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that business training has a positive impact on the profits of female-run microenterprises (Arráiz, Bhanot, and Calero Citation2019; Bruhn and Zia Citation2013; Bulte, Robert, and Nhung Citation2017; McKenzie and Puerto Citation2021). However, related literature indicates that female-run microenterprises have no significant impact on profits in several countries.

One possible explanation for the disparity between our findings and the related literature is that we examine all self-employed workers from a nationally representative survey (the Nicaragua LSMS), whereas previous studies are based on randomised field experiments that involve loan clients of MFIs who are willing to participate in business training programmes. Another aspect of the SBFE programme’s strong gender effect relates to Nicaragua’s labour market. In India, Field, Jayachandran, and Pande (Citation2010) find that cultural and labour market discrimination against women could be a reason for no effect of business training on female entrepreneurs. The labour market structure in Nicaragua is relatively favourable for female workers. According to the Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean, the share of female workers in total employment in Nicaragua increased from 42% in 1993 to 57% in 2014, suggesting lower labour market discrimination against women in the country.

The fact that we have no significant programme impact on male self-employed workers needs to be investigated further. When the MEFCCA launched the SBFE programme, it targeted both male and female self-employed workers, with a special emphasis on women empowerment. Understanding why the SBFE programme was ineffective for male self-employed workers may shed light on policy implications for business and skills training in developing countries in the future.

The main limitation of this study is that we do not identify the programme intervention at the individual level and do not know who received the training because we do not have access to administrative data. Given that our ITT estimates for female self-employed workers are still sizeable and statistically significant, the true impact of the programme calculated by treatment on the treated estimates could be greater than the results presented here. Another limitation is that programme eligibility was not randomly assigned; thus, there may be systematic differences in both observable and unobservable characteristics between the eligible and non-eligible groups, and our claim of causality should be viewed with caution. Nevertheless, we addressed this issue by using quasi-experimental approaches such as PSM, DID, and various fixed effects.

Although these findings are specific to self-employed workers in Nicaragua, with the caveats mentioned above, they may provide some insights to other developing countries with a high level of informal economic activity and self-employment when it comes to targeting the desired beneficiaries of business training programmes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Booyuel Kim

Booyuel Kim is an associate professor of Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Seoul National University. He received a B.A. in Economics from Handong University in 2003, and a Master of International Affairs and his Ph.D. in Sustainable Development both from Columbia University in 2009 and 2014, respectively. After completing his Ph.D., he worked as a post-doctoral research scholar at the Earth Institute of Columbia University while participating in the Millennium Villages Project and the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign. From 2015 to 2020 he worked as an assistant professor at KDI School of Public Policy and Management. His research interests span health and education issues in the developing countries as well as in Korea. As the principal investigator, he has been in charge of evaluating the following field experiments: girls’ education support project and HIV/AIDS prevention project in Malawi (since 2010), rural community-driven development project in Cambodia and Myanmar (since 2015), and an A.I.-backed adaptive learning project in Vietnam (since 2018).

Rony Rodriguez-Ramirez

Rony Rodriguez Ramirez is a PhD student in Education Policy and Program Evaluation at Harvard. Prior to enrolling in the PhD program, he was working as a research assistant at The World Bank, Development Impact Evaluation Unit.” Before working at The World Bank, he worked as an RA at KDI School of Public Policy and Management in South Korea working on the economic history of the Nicaragua Civil War, at SoDa Labs of Monash University setting up a novel dataset on environmental assassinations, and at Instituto Tecnológico Autonónomo de México – Innovation for Poverty Action in Mexico City evaluating the long-term impact of outsourcing schools in Liberia. He received a B.A. in Applied Economics from Universidad Centroamericana in Nicaragua, and a M.A. in Development Policy from KDI School of Public Policy and Management. His research interests are development economics, impact evaluations, labor market, violence, and conflict.

Hee-Seung Yang

Hee-Seung Yang is a professor in School of Economics at Yonsei University, Korea. Before joining Yonsei, he had worked at KDI School of Public Policy and Management, Korea and at Monash University, Australia, after finishing his Ph.D. in Economics at UC San Diego. His primary research interests are in labor economics and development economics. In particular, he has studied policy relevant questions to understand how various public policies affect individual behaviors and labor market outcomes of the targeted population. To date, his research has been published in journals such as Journal of Public Economics, Journal of Population Economics, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Economic Development & Cultural Change, and Industrial & Labor Relations Review.

Notes

1. Although the overall microfinance impact on business profits or earnings from these studies are weak and imprecisely measured, some reported that microfinance increased profits for pre-existing business (Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster, and Kinnan Citation2015) and earnings from self-employment activities (Crépon et al. Citation2015).

2. Many studies analysed the effects of business training separately (Bruhn and Zia Citation2013; Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar Citation2014; Field, Jayachandran, and Pande Citation2010; Valdivia Citation2015).

3. Related literature also reports no significant impact for female entrepreneurs (Berge, Bjorvatn, and Tungodden Citation2015; Drexler, Fischer, and Schoar Citation2014; Field, Jayachandran, and Pande Citation2010; Giné and Mansuri Citation2021; Karlan and Valdivia Citation2011).

4. This is translated to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in English.

5. The programme requires the following documentation and conditions on the beneficiaries; (1) copy of birth certificate or identification card; (2) copy of the last academic grades or certificates showing that the individual can read and write; (3) 14 years or older for the training in the commerce and service sector; (4) 16 years or older for the training in the manufacturing and construction sector; and finally (5) the individual should desire to be trained. Self-employed workers who want to participate in the programme must fill a form at the MEFCCA, after which they are assigned to the INATEC to coordinate the day in which that training will be performed and to determine the number of training hours.

6. The MEFCCA and the INATEC have consolidated a strategy to improve education, skills, and jobs especially for female self-employed workers while emphasising women’s participation in the SBFE programme and job creation in the productive sectors (The World Bank Citation2017). During our interviews with programs managers in Nicaragua, we observed two main strategies implemented by the program in order to emphasise involvement of women self-employed workers. First, the program actively focused on recruiting and supporting women entrepreneurs by providing targeted outreach, networking opportunities, or specific resources tailored to their needs. This approach could help address gender-based barriers to entry and provide women with increased access to entrepreneurial opportunities. Second, the program facilitated access to business networks, markets, or procurement opportunities that were traditionally difficult for women to access. By providing a platform, such as social media communication channels, for women entrepreneurs to connect with potential customers, clients, or partners, the program could have enabled them to expand their business reach and increase their earning potential. Similar to what it is described in Arráiz et al. (Citation2019), the program might have served as a catching-up program for women that were initially worse in comparison to ineligible women and/or men.

7. None of the related studies reported a training duration of more than 100 hours. For example, Brooks, Donovan, and Johnson (Citation2018) implemented a business training programme in Nairobi, Kenya, consisting of four two-hour classes (only eight hours). Similarly, Bruhn and Zia (Citation2013) implemented a nine-hour-long business training programme in Bosnia and Herzegovina (spread out over three days of three-hour training each). Relatively more intensive business training programs, such as Campos et al. (Citation2017) and Giné and Mansuri (Citation2021), provided 36 and 46 hours of training, respectively, which are still less than half of the total training hours provided in the SBFE programme.

8. In this study, we implement full Mahalanobis matching using the 10 nearest neighbours without a caliper. Using different matching algorithms such as kernel and radius matching or increasing/decreasing the number of neighbours does not significantly change the main results.

9. examines the results of the test for parallel trends by gender. We do not find any systematic difference for female self-employed workers (columns 4–6) between the eligible and non-eligible groups during 2005–2009 period.

10. We believe that the formal training dummy in our dataset does not fully capture the true participation in the SBFE programme for the following reasons. First, we acknowledge that we do not have a precise measure for training take-up due to a lack of access to the administrative data. However, the Government of Nicaragua (Citation2016) reported that 197,356 self-employed workers participated in the SBFE programme in 2014 and around 200,000 self-employed people each year for the following five years are expected to participate in the SBFE programme. The SBFE programme coverage is large enough to support a significant portion of self-employment in Nicaragua. Second, the SBFE programme was provided mainly in the capital city and major cities while our sample covers the whole Nicaragua population. Thus, the formal training dummy could be systematically underestimated.

11. It would be useful to know the actual faction of the self-employed in the treatment group who would have received the business training. That information is crucial for understanding an alternative potential channel if the larger effect on less educated and younger women and the negligible effects on older and more educated women and on men was due to differences in likelihood of receiving training. However, we do not know if the self-employed in the treatment group received the business training program and the lack of information on exposure to the program are one of the main limitations of this study.

References

- Angelucci, M., D. Karlan, and J. Zinman. 2015. “Microcredit Impacts: Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (1): 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130537.

- Arráiz, I., S. Bhanot, and C. Calero. 2019. “Less is More: Experimental Evidence on Heuristic-Based Business Training in Ecuador.” IDB Invest Working Paper TN No.18. Washington, D.C: Inter-American Development Bank.

- Attanasio, O., B. Augsburg, R. De Haas, E. Fitzsimons, and H. Harmgart. 2015. “The Impacts of Microfinance: Evidence from Joint- Liability Lending in Mongolia.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (1): 90–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130489.

- Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, R. Glennerster, and C. Kinnan. 2015. “The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation.” American Economic Journal Applied Economics 7 (1): 22–53. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130533.

- Banerjee, A., D. Karlan, and J. Zinman. 2015. “Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140287.

- Beaman, L., D. Karlan, B. Thuysbaert, and C. Udry. 2014. “Self-Selection into Credit Markets: Evidence from Agriculture in Mali.” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 20387. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20387.

- Berge, L., K. Bjorvatn, and B. Tungodden. 2015. “Human and financial capital for microenterprise development: evidence from a field and lab experiment.” Management Science 61 (4): 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1933.

- Bjorvatn, K., and B. Tungodden. 2010. “Teaching Business in Tanzania: Evaluating Participation and Performance.” Journal of the European Economic Association 8 (2–3): 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00526.x.

- Blattman, C., and S. Dercon. 2018. “The Impacts of Industrial and Entrepreneurial Work on Income and Health: Experimental Evidence from Ethiopia.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10 (3): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170173.

- Blattman, C., N. Fiala, and S. Martinez. 2013. “Generating Skilled Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Experimental Evidence from Uganda.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (2): 697–752. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt057.

- Brooks, W., K. Donovan, and T. Johnson. 2018. “Mentors or Teachers? Microenterprise Training in Kenya.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10 (4): 196–221. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170042.

- Bruhn, M., and B. Zia. 2013. “Stimulating Managerial Capital in Emerging Markets: The Impact of Business Training for Young Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Development Effectiveness 5 (2): 232–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2013.780090.

- Bulte, E., L. Robert, and V. Nhung. 2017. “Do Gender and Business Trainings Affect Business Outcomes? Experimental Evidence from Vietnam.” Management Science 63 (9): 2885–2902. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2472.

- Caliendo, M., and S. Kopeinig. 2008. “Some Practical Guidance for the Implementation of Propensity Score Matching.” Journal of Economic Surveys 22 (1): 31–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x.

- Campos, F., M. Frese, M. Goldstein, L. Iacovone, H. Johnson, D. McKenzie, and M. Mensmann. 2017. “Teaching Personal Initiative Beats Traditional Training in Boosting Small Business in West Africa.” Science 357 (6357): 1287–1290. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5329.

- Cho, Y., and M. Honorati. 2014. “Entrepreneurship Programs in Developing Countries: A Meta Regression Analysis.” Labour Economics 28:110–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2014.03.011.

- Crépon, B., F. Devoto, E. Duflo, and W. Parienté. 2015. “Estimating the Impact of Microcredit on Those Who Take It Up: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Morocco.” American Economic Journal Applied Economics 7 (1): 123–150. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130535.

- De Mel, S., D. McKenzie, and C. Woodruff. 2014. “Business Training and Female Enterprise Start-Up, Growth, and Dynamics: Experimental Evidence from Sri Lanka.” Journal of Development Economics 106:199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.09.005.

- Drexler, A., G. Fischer, and A. Schoar. 2014. “Keeping It Sim- Ple: Financial Literacy and Rules of Thumb.” American Economic Journal Applied Economics 6 (2): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.2.1.

- Field, E., S. Jayachandran, and R. Pande. 2010. “Do Traditional Institutions Constrain Female Entrepreneurship? A Field Experiment on Business Training in India.” The American Economic Review 100 (2): 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.125.

- Fields, G. 2019. Self-Employment and Poverty in Developing Countries. IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.60.v2.

- Gindling, T., and D. Newhouse. 2014. “Self-Employment in the Developing World.” World Development 56:313–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.03.003.

- Giné, X., and G. Mansuri. 2021. “Money or Management? A Field Experiment on Constraints to Entrepreneurship in Rural Pakistan.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 70 (1): 41–86. https://doi.org/10.1086/707502.

- Government of Nicaragua. 2016. Anexo al Presupuesto General de la República 2016 Marco Presupuestario de Mediano Plazo 2016 – 2019. Managua: Government of Nicaragua.

- Gupta, S. 2011. “Intention-To-Treat Concept: A Review.” Perspectives in Clinical Research 2 (3): 109. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.83221.

- Heckman, J., H. Ichimura, and P. Todd. 1997. ““Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme.” The Review of Economic Studies 64 (4): 605–654. https://doi.org/10.2307/2971733.

- Heckman, J., R. LaLonde, and J. Smith. 1999. The Economics and Econometrics of Active Labor Market Programs. In Handbook of Labor Economics, edited by O. Ashenfelter and D. Card. 1st 1865–2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4463(99)03012-6.

- Karlan, D., and M. Valdivia. 2011. “Teaching Entrepreneurship: Impact of Business Training on Microfinance Clients and Institutions.” Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (2): 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00074.

- Khandker, S. R. 2005. “Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh.” The World Bank Economic Review 19 (2): 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhi008.

- McKenzie, D., and S. Puerto. 2021. “Growing Markets Through Business Training for Female Entrepreneurs: A Market-Level Randomized Experiment in Kenya.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13 (2): 297–332. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180340.

- McKenzie, D., and C. Woodruff. 2014. “What are We Learning from Business Training and Entrepreneurship Evaluations Around the Developing World?” The World Bank Research Observer 29 (1): 48–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkt007.

- Pitt, M., and S. R. Khandker. 1998. “The Impact of Group-Based Credit Programs on Poor Households in Bangladesh: Does the Gender of Participants Matter?” Journal of Political Economy 106 (5): 958–996. https://doi.org/10.1086/250037.

- Rosenbaum, P., and D. Rubin. 1983. “The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects.” Biometrika 70 (1): 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

- Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEDLAS and The World Bank). 2022. Employment Structure (Distribution of Workers by Gender, Age and Education). Dataset.

- Tarozzi, A., J. Desai, and K. Johnson. 2015. “The Impacts of Microcredit: Evidence from Ethiopia.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (1): 54–89. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130475.

- Valdivia, M. 2015. “Business training plus for female entrepreneurship? Short and medium-term experimental evidence from Peru.” Journal of Development Economics 113:33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.10.005.

- The World Bank. 2017. Nicaragua. Paving the Way to Faster Growth and Inclusion. Washington, D.C: The World Bank.

Appendix

Table A1. CUAEN codes and eligibility status, all years.

Table A2. Test for parallel trends by gender.

Table A3. Descriptive statistics of possible mechanism during pre-trend periods.