ABSTRACT

In developing countries, value chains for many crops are underdeveloped, leading to low producer prices and poor quality produce. Value chain research using secondary data is made difficult by selection problems, whereas experimental research is logistically very difficult and lacks external validity. With the intention of conducting a field experiment, we piloted an intervention connecting smallholder groundnut farmers in Ghana to a premium groundnut processor through aggregators. While we successfully delivered inputs and training to farmers, we failed in our attempts to link aggregators with downstream processors over two growing seasons. In this paper, we situate the challenges we faced in the broader literature on value chains and identify three problems that prevented us from establishing a value chain for high quality groundnuts: uncertainty, cash constraints, and trust. To help inform future research on this topic, we propose three specific interventions that could mitigate these problems.

1. Introduction

Agricultural value chain development is a priority for many governments, non-government organisations (NGOs), and private actors for its potential to raise farmer incomes, improve food quality, and increase consumer choice. In many developing countries, agricultural value chains have undergone rapid transformation in the past few decades, in large part due to the modernisation of the retail sector (Reardon et al. Citation2003; Weatherspoon and Reardon Citation2003). Agricultural value chain development can entail linking farmers to markets through contractual arrangements (Bellemare and Bloem Citation2018; Grosh Citation1994; Meemken and Bellemare Citation2020; Minot and Sawyer Citation2016; Porter and Phillips-Howard Citation1997; Wang, Wang, and Delgado Citation2014), organising farmers into agricultural cooperatives (Ortmann and King Citation2007), providing third party quality verification services (Abate et al. Citation2021; Saenger, Torero, and Qaim Citation2014), developing specialised brokers (Reardon and Timmer Citation2007), and strengthening vertical integration (Grosh Citation1994; Suzuki, Jarvis, and Sexton Citation2011). Despite global trends in value chain development, in Ghana, and throughout Africa, few farmers participate in modern value chains (Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). Groundnuts in Ghana are predominantly traded on spot markets, offering little opportunity for producers to access premium buyers and increase profits through quality improvement.

The overarching goal of our research project was to develop and evaluate a value chain intervention to link smallholder groundnut producers in Ghana to a premium processor through aggregators. These aggregators would serve as specialised brokers, working with smallholder farmers to produce high quality groundnuts to be bulked and sold to a specific processor with strict quality requirements at a high price. This value chain would benefit farmers, who would receive higher prices and some inputs, and the processor, who would receive produce of known and high quality. We initially intended to use a randomised control trial (RCT) to evaluate the impact of this improved value chain on farmer practices and income, processor procurement and production costs, and food quality. Before doing so, we set out to pilot the intervention over the course of two groundnut production seasons. During the pilot, we encountered several challenges that are characteristic of the groundnut value chain in Ghana, and of agricultural value chains more broadly in the developing world: uncertainty, cash flow constraints, and lack of trust. In this paper we detail these challenges and how they prevented the pilot’s success.

The literature on value chain development in developing countries dates back decades and is summarised in several thorough and broad reviews (Barrett et al. Citation2022; Reardon and Peter Timmer Citation2007; Reardon et al. Citation2009). The literature on contract farming in particular is dense and includes many papers on the impact of contract farming on farmer outcomes, with recent reviews by Wang, Wang, and Delgado (Citation2014), Minot and Sawyer (Citation2016), Bellemare and Bloem (Citation2018) and Ton et al. (Citation2018). Contract farming, and modern value chains more generally, require that both the farmer and buyer (aggregator, retailer, or processor) select into an agreement. For studies using observational data, and cross-sectional observational data in particular, there is substantial potential for selection bias which complicates any study seeking to establish causal impacts by comparing participants and non-participants (Barrett et al. Citation2022; Bellemare and Bloem Citation2018; Ton et al. Citation2018; Wang, Wang, and Delgado Citation2014). Ton et al. (Citation2018) find that in addition to selection bias, publication and survivor bias lead to a clouded understanding of how value chain development affects farmer outcomes.Footnote1

To alleviate concerns over selection bias, some researchers have implemented RCTs to estimate the impact of modern value chains on farmer outcomes. Ashraf, Giné, and Karlan (Citation2009) offered credit and marketing opportunities for Kenyan farmers to grow cash crops (baby corn and French beans) for export, estimating the impact on production and marketing, use of formal credit, and income. Magnan et al. (Citation2021), Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo (Citation2023), Bold et al. (Citation2022), and Hoffmann et al. (Citation2023) estimate the impacts of offering a quality premium and access to quality-improving technologies on production and marketing practices for groundnuts in Ghana and Senegal, and maize in Uganda and Kenya, respectively. Arouna, Michler, and Lokossou (Citation2021) estimate the impacts of offering production contracts (quantity and sale price determined before planting) to rice farmers in Benin on production, marketing, and farmer income. These RCTs have largely shown that farmers do change their production and marketing behaviour when presented with a new value chain opportunity. However, the studies were generally conducted over a single growing season, with heavy involvement of a third party and/or a buyer already known by farmers. Thus, while the internal validity of experimental studies may be high, their validity in external settings can be limited.

Because agronomic and economic circumstances can change from year to year, it is important to verify that value chain interventions result in positive impacts over a range of circumstances rather than one instance. In some years, participation in a modern value chain may be beneficial to a given actor along the chain, and in other years it may not. Success of a value chain intervention in one year does not necessarily mean continued or regular success. In Ashraf, Giné, and Karlan (Citation2009), farmers benefited from cash crop production in the first year they participated in an export-oriented value chain. After that first year, however, a change in European standards caused the exporter to stop buying from the NGO, leaving the farmers without a market for their cash crops and unable to repay loans they had incurred to qualify for participation in this value chain. The NGO subsequently collapsed and farmers returned to growing traditional staples. In Magnan et al. (Citation2021), the research team offered to pay farmers a premium for high quality (low aflatoxin) groundnuts over the course of two years. While few farmers took up this opportunity in the first year, many more did in the second.Footnote2 However, in the second year the quality of groundnuts available on the open market at no premium was generally high, and an actual buyer likely would have sourced groundnuts on the spot market, which would have disadvantaged farmers who had made investments in quality but could not get a premium price, discouraging future investment. Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo (Citation2023) offered a quality premium for a single year during which prevailing market prices were high, often exceeding the market price. The premium offer did increase the share of farmers selling through the cooperative at a premium, but this was still only 25% of treatment farmers. Had the cooperative had a downstream contract with an exporter or premium processor, the quantity sold through the cooperative could have fallen short. Arouna, Michler, and Lokossou (Citation2021) offered production contracts to farmers from a private miller for a single season, during which the prevailing market price at harvest was lower than the contracted price leaving farmers no incentive to side sell. Had the market price instead been high, the contract could have broken down due to side selling and the results would have been different. The study by Bold et al. (Citation2022) covered four growing seasons, alleviating some concerns that the results were not dependent on production or market conditions in a single year. Furthermore, longer studies such as this give farmers more time to familiarise themselves with a new buyer and build trust, allowing a value chain to strengthen over time.

Value chain experiments typically depend heavily on a facilitator who is not the buyer or seller – usually an NGO or the research team itself. These experiments also typically focus on only one link of the chain. Magnan et al. (Citation2021), Bold et al. (Citation2022), Hoffmann et al. (Citation2023), and Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo (Citation2023) all aim to determine whether farmers will change their production practices in reaction to a price premium. Without a downstream buyer agreeing ex ante to pay the premium for the aggregated produce, the research team must pay or backstop it. While the willingness and ability of the research team to pay a premium is not known by farmers, it is known by the buyer. Absent this assurance, the buyer would not be able to offer premiums without confidence that there is downstream demand for quality from consumers, premium processors, or export markets, which is far from guaranteed in emerging value chains (Abate et al. Citation2021). Ashraf, Giné, and Karlan (Citation2009) consider the entire value chain that links smallholder farmers to a horticultural crop exporter. To instil trust and facilitate communication and financial transactions, an NGO acted as an intermediary between farmers and the exporter. Without the NGO, such linkages might not form.

Some experimental interventions rely on existing buyer-seller relationships, and intervene by changing only the terms of sale. For instance, Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo (Citation2023) offered a premium to groundnut farmers to sell through the cooperative through which they were already accustomed to selling. Arouna, Michler, and Lokossou (Citation2021) worked with a social enterprise already familiar to farmers to offer production contracts. In contrast, Ashraf, Giné, and Karlan (Citation2009), Magnan et al. (Citation2021), Bold et al. (Citation2022), and Hoffmann et al. (Citation2023) all invited farmers to sell to an unfamiliar buyer, which may reflect a more realistic transition into a modern value chain.

In experimental value chain research, there is an acute trade-off between feasibility and realism. Introducing new transaction conditions, or new business relationships altogether, is difficult. In reality, many value chain interventions fail (Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). Ensuring the success of value chain relationships, particularly within the time frame of a research project, requires levels of support that may be difficult to replicate outside of a research project. Even with support, value chain interventions can fail, as was our experience. In this paper we document this failure for two reasons: (1) it is important that both successful and unsuccessful interventions become part of the scientific record, and (2) other researchers and practitioners working on value chain development may be able to learn from our experience and avoid our missteps (Karlan and Appel Citation2017).

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2 we discuss the current state of the groundnut value chain in Northern Ghana and challenges it faces in modernising. In Section 3, we describe our proposed research project and our experiences working with groundnut value chain actors. In Section 4, we offer some potential solutions to the problems we encountered. In Section 5, we conclude.

2. The groundnut value chain in Ghana

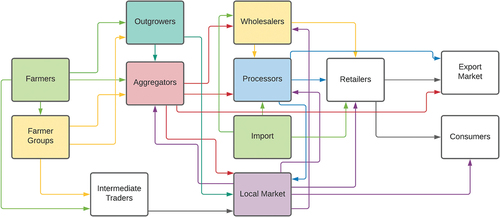

The groundnut value chain in northern Ghana is complex and disorganised. It consists of many fragmented smallholder farmers, aggregators, processors, and retailers (). Smallholder farmers (men and women) grow groundnut for sale and household consumption. Groundnut production is entirely rainfed and farmers use few inputs – essentially only seed and labour. Farmers are extremely cash constrained. If they do purchase fertiliser, they use it on maize. In the rare cases where an aggregator provides inputs on credit, the aggregator provides land preparation services, and even more rarely, seeds. Yields are consequentially low compared to those obtained on local experiment station plots or in farmer field trials (Masters et al. Citation2013; Narh et al. Citation2014; Owusu-Adjei, Baah-Mintah, and Salifu Citation2017). For more detailed descriptions of the groundnut value chain in Ghana, see Masters et al. (Citation2013), DAI (Citation2014), and Owusu-Adjei, Baah-Mintah, and Salifu (Citation2017).

Farmers often sell small quantities of groundnuts multiple times after each harvest to earn money as needed.Footnote3 Collective marketing is rare in Ghana,Footnote4 whereas groundnut cooperatives are common in Senegal (Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo Citation2023). Ghanaian farmers typically sell as individuals to small traders or larger aggregators that purchase at farmgate, or in local markets where groundnuts are then either resold by local retailers or further bulked by wholesalers and sent to urban centres in the south of the country. Groundnuts typically remain in their shells until they are sold to processors or to consumers. This helps to preserve, but also masks, groundnut quality. In retail markets, groundnuts are shelled and sorted based on visible traits, where nuts of lower quality are discounted and often make their way into locally processed fried and spiced snacks and seasoning, uses that disguise low quality groundnuts.

Current groundnut value chains have several characteristics that hinder their development. Groundnuts are grown by many smallholder farmers in Ghana; medium and large-scale production is rare.Footnote5 Aggregating production from many small farmers involves large transaction costs per volume procured (Minot and Sawyer Citation2016), and exacerbates side selling risks (Upton and Lentz Citation2017). While farmer groups exist in Northern Ghana, they generally do not collectively market groundnuts. Because groundnuts are typically grown in this setting using traditional methods and no inputs other than seeds and labour – albeit generating poor yields – farmers do not perceive an absolute need for technical assistance or input provision that often underpins modern value chain development (Ashraf, Giné, and Karlan Citation2009; Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). Groundnuts are non-perishable, which gives buyers (sellers) more flexibility in who they buy from (sell to) and when. This flexibility lends itself well to using spot markets (Barrett et al. Citation2022; Grosh Citation1994; Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). Because groundnuts are easily processed and consumed throughout Northern Ghana, farmers can decide to either sell groundnuts locally whenever they need money or to consume them directly, options not available for cash crops such as cocoa, coffee, cotton, and tea. Most modern value chains in Africa centre around perishable and/or cash crops for which there is low local demand (Minot and Sawyer Citation2016).

Perhaps most importantly, modern farm-to-processor value chains are unlikely to develop around crops for which a quality premium does not exist at farmgate, and for which quality is fully observable (Barrett et al. Citation2022; Grosh Citation1994; Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). While there is some visible variation in groundnut quality, this is generally not rewarded at the farm gate because groundnuts are aggregated from many different farmers as they move down the value chain. Processors or retailers that require quality can sort on observable traits (at a cost), without transmitting a price premium to the farmer.

The emerging market for aflatoxin safety in Ghana may change this calculus. Aflatoxin is an invisible and tasteless secondary metabolite of certain moulds, and chronic exposure to aflatoxin is linked to liver disease (IARC Citation1993; Liu and Wu Citation2010; Liu et al. Citation2012; Williams et al. Citation2004). It cannot be eliminated through processing or cooking. Because acute toxicosis from aflatoxin consumption is rare, and the diseases linked to aflatoxin occur over long periods of exposure, aflatoxin safety can be considered a credence attribute; quality is unknown by the consumer even after purchasing it. Testing is expensive, and can only be done cost-effectively on very large lots of groundnuts, if at all. In practicality, aflatoxin testing in Ghana is currently performed only by exporters to Europe and one premium processor that makes ready-to-eat-foods for humanitarian use and school feeding programs.

Aflatoxin contamination begins in the field, but is exacerbated in storage under poor conditions (Jordan et al. Citation2020). Farmers can improve quality and decrease aflatoxin risk through good post-harvest practices (Deutschmann, Bernard, and Yameogo Citation2023; Hoffmann et al. Citation2023; Magnan et al. Citation2021; Strosnider et al. Citation2006). These measures, however, require additional investment in labour and materials. The possibility to earn a premium by producing groundnuts for a processor requiring aflatoxin-safe groundnuts, coupled with the need for added investment to achieve low aflatoxin groundnuts, presents a new opportunity to modernise the groundnut value chain. In our research project, we partnered with aggregators to deliver knowledge and materials that would enable smallholders to produce and sell low aflatoxin groundnuts, offering a price premium that a downstream processor would guarantee. A local university provided testing at the farmer level using research funds.

Even after eliminating quality uncertainty among farmers, aggregators, and processors, the aggregator model faces considerable challenges. Farmers may decide to side sell if they are in need of money quickly or find a better spot market price (Upton and Lentz Citation2017). They may also elect to hold onto their groundnuts to wait for market prices to rise during the lean season rather than selling to an aggregator (Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). If farmers do not sell a quantity expected by the aggregator, downstream processors may receive lower than expected quantity and quality deliveries from aggregators. Delays in aggregation and delivery can lead to broken purchase agreements. Because of the challenges of procuring low aflatoxin groundnuts in Ghana, domestic processors that require them often resort to importing.

In our efforts to connect smallholders to premium processors through a more direct and linear modern value chain, we interacted with many value chain actors including farmers, out-growers, aggregators, processors, and NGOs. These interactions helped us identify three main challenges inhibiting groundnut value chain development: uncertainty, cash flow constraints, and a lack of trust.

2.1. Uncertainty

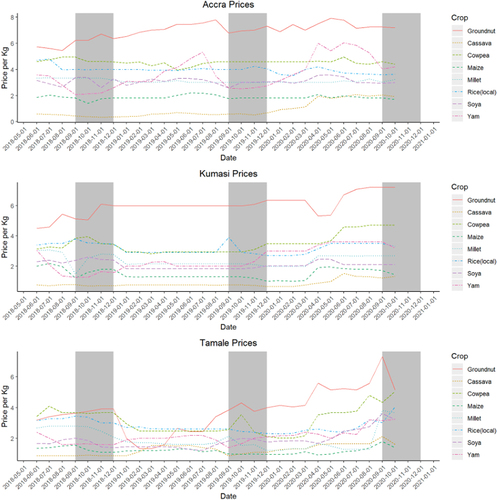

The first overarching issue inhibiting groundnut value chain development is uncertainty over price and quantity. Groundnut prices are highly uncertain. shows the monthly prices of staple crops in Ghana from June 2018 to October 2020 at three regional urban centres: Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale.Footnote6 Groundnut prices are volatile in the Northern region (Tamale), where 94% of all groundnuts in Ghana are produced (Masters et al. Citation2013). The shaded areas in each panel of represent the harvest months in Northern Ghana (September to December). Groundnut prices often increase before harvest and drop shortly after, with varying levels of price fluctuation in the months after harvest. The price of groundnuts in Tamale is impacted by many factors, such as weather, early/late harvest in other groundnut producing regions, and the quantity and quality of groundnut production in neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso.

Figure 2. Prices of key crops at three important markets in Ghana 2018–2020. The shaded regions depict the typical groundnut harvest months in Northern Ghana (typically September to December). Source: Esoko.com.

While setting a price before harvest would appear to reduce price risk for both farmer and buyer (Arouna, Michler, and Lokossou Citation2021), in our context uncertainly led to both parties finding it risky to pre-arrange a price before harvest. If a purchase agreement price is below the eventual market price, aggregators stand to win and farmers to lose. However, without enforceable contracts, farmers often side sell at a higher price in a local market or to another aggregator. As one aggregator noted, ‘You need to agree to this price before, but if the market price goes up then I cannot guarantee that farmers will sell it at the agreed upon price’ (pers. comm., March 2020). If the purchase agreement price is above the market price, farmers stand to win and aggregators to lose. However, an aggregator could choose to terminate the agreement and buy from the local market or negotiate down the agreed price. In our discussions about how a contract would work, another aggregator inquired, ‘Well what if the market price goes down? Can we renegotiate a lower price?’ When told that they could not, they responded, ‘That isn’t fair. Why should I always be on the losing side?’ (pers. comm., March 2020). Both sides expressed reluctance to enter a contract where market conditions could make the contract unfavourable to them in the future, especially when they do not trust the other party to honour the contract when market conditions are favourable.

In addition to price uncertainty, groundnut value chains are plagued by quality uncertainly. This includes uncertainty over the quality of groundnuts produced by a specific farmer or group of farmers, and uncertainty over the general quality of groundnuts available in the market.

If buyers cannot accurately judge quality at farm gate, they will not pay as high of a premium for it. Or, if buyers test for quality in a way farmers cannot observe, buyers may under-report quality and offer a lower price, reducing the incentive for farmers to invest in quality. Third party quality verification (in our case aflatoxin testing) can help overcome these problems (Bernard et al. Citation2017; Saenger, Torero, and Qaim Citation2014), but can be expensive to conduct on a farmer-by-farmer basis.

Quality uncertainty at the market level is also an impediment to groundnut value chain development. Aflatoxin levels are highly variable from year to year, and even between regions in the same year (Magnan et al. Citation2021; Mutiga et al. Citation2014, Citation2015). This sets up a situation where investments in aflatoxin prevention may or may not lead to higher quality groundnuts than those widely available on the market. Aggregators and farmers face risks in forming advance agreements on quality, just as they do for price. If an aggregator and a farmer agree to a pre-harvest price for low aflatoxin groundnuts, but aflatoxin ends up being generally low throughout the region, aggregators can easily purchase low aflatoxin groundnuts from the market, creating an incentive for the buyer to default on the contract. If aflatoxin levels end up being generally high and the farmer has produced low aflatoxin groundnuts, the farmer may try to renegotiate price or find another premium buyer.

Contracts can be used to protect both buyers and sellers from price and quantity uncertainty. However, without a legal environment that supports contract enforcement, agents who wish to transact must rely on trust, a topic we address in Section 2.3. If both buyer and seller take a short view of a commercial relationship, they will each try to exploit volatility when it appears to break in their favour, undermining the formation of a long-term mutually beneficial relationship.

2.2. Cash flow constraints

The second overarching issue inhibiting the development of premium value chains is cash flow or liquidity constraints. That cash flow constraints can prevent smallholder farmers from purchasing inputs is a major economic rationale for contract farming (Grosh Citation1994; Minot and Sawyer Citation2016). An aggregator provides inputs to farmers, helping them produce greater quantity or meet quality expectations. Input provision also has the benefit of creating an obligation for farmers to sell to the aggregator via the loan repayment.Footnote7 However, such arrangements require aggregators to secure financing months before they can sell to processors, which was difficult for aggregators to do. We observed that farmers expected aggregators to provide input support, and aggregators expected processors to fund input support, but neither aggregators or processors were able to meet these expectations because they lacked the funds or would not take on the risk of default by the other party.Footnote8

Challenges in agricultural value chain finance are well documented (Miller Citation2012). Without an arrangement that requires farmers to repay input loans with production, downstream cash flow constraints make it difficult for aggregators to purchase groundnuts from farmers. At harvest time, farmers are reluctant to receive payment after the time of sale. Even if they do enter an agreement to sell to an aggregator, side selling to meet immediate consumption needs is common. Thus, aggregators must provide cash on the spot when purchasing. While aggregators may not be as cash constrained as farmers, they are not always able to make cash purchases of the quantities necessary to fulfill an agreement with a downstream processor. To make such large purchases, the aggregator requires advance partial payment from the processor, or that farmers wait for payment. Both scenarios require trust (see Section 2.3 below), without which aggregators and processors often resort to smaller transactions drawn out over a longer period of time. This extends the length of time that groundnuts are stored on farms under sub-optimal conditions, which increases the risk of aflatoxin contamination and the risk that a farmer side sells.

Processors can also face cash flow constraints, as they do not receive payment for their groundnut products until they are sold. They are not always in a position to provide cash to aggregators to purchase groundnuts from farmers, or even to pay aggregators upon delivery. Unexpected processor cash flow problems can leave them unable to purchase groundnuts as agreed, forcing aggregators to sell on local markets at a lower price. In an environment where cash flow problems are frequent and at times unpredictable, it is difficult for any actor along the value chain to engage in the kind of purchase agreement necessary to channel dependable quantities of high quality groundnuts from farmers to processors.

2.3. Trust

The final overarching issue preventing groundnut value chain development in Ghana is lack of trust. A lack of trust between agents in a value chain increases the cost of each transaction, which can prevent them from taking place (de Vries et al. Citation2023). Without recourse to a well-functioning legal system through which contracts can be enforced, the only way one party can sanction another is through discontinuation of future agreements (Grosh Citation1994). If neither party is confident the agreement will be profitable in the future, or that the other party will continue with the agreement, the threat of discontinuation is not enough to deter parties from defaulting on contracts.

Some long-term relationships do exist in groundnut value chains in Ghana, notably between aggregators and farmers. These aggregators build relationships with farmers over many years to establish trust and obtain a consistent supply of groundnuts. Generally these relationships are built on input provision. The aggregator provides inputs (often tractor rental for land preparation) on credit to farmers, who pay aggregators back in groundnuts. If farmers successfully repay the aggregator, other inputs may be provided on credit (e.g. seed).Footnote9 Farmers have an incentive to repay aggregators so they can receive inputs on credit in the future, reducing the risk of side selling.

Although some farmers and aggregators have long-term relationships, these relationships can be tenuous. Cash flow problems may prevent the aggregator from being able to provide farmers with inputs on credit, and farmers may side sell or default on loans in order to make ends meet, despite having been supplied inputs on credit. One aggregator stated, ‘I refuse to give inputs on credit because I have lost money when farmers who I have given seed, tractor rental, and other inputs refused to sell groundnuts to me. There is no guarantee the farmers will sell to me and I will be left with no money’ (pers. comm., March 2020). While trust can be established between aggregators and processors, it can be dissolved by a single bad transaction. One processor reported, ‘I have previously worked with aggregators who in the first year and sale had high quality peanuts, but later when the season was not very good they added sticks and rocks to the bags making future work with them impossible’ (pers. comm., January 2020).

Without trust, problems arising from uncertainty and cash flow constraints are exacerbated. Agents along the value chain can mutually insure against price and quality uncertainty, but this requires trust from both parties and repeated transactions. Trust could help mitigate the effects of cash flow problems on value chain development. For instance, if farmers trusted that an aggregator would pay a higher price for groundnuts later than is available on the spot market now, and aggregators could trust that processors would pay them for a large shipment after they have had some time to sell their processed products, then cash flow constraints would be less prohibitive. Without trust, however, parties to a transaction expect cash on delivery, resulting in delays and inefficiencies that prevent value chain development.

3. The piloted intervention

The goal of our project was to estimate the impacts of premium value chain inclusion on smallholder farmer outcomes including production practices, yields, aflatoxin levels, and profits. To do this, we planned to create a premium value chain in Northern Ghana that would help smallholder farmers mitigate aflatoxin risk and remove uncertainty over aflatoxin levels for aggregators and processors. To causally estimate the impacts of being included in such a value chain, we planned an RCT. We would identify groundnut producing communities from the catchment area of the aggregator(s) and assign half of the communities to be invited to supply low-aflatoxin groundnuts to a premium processor through the aggregator. The other communities would serve as a control group and produce and market groundnuts as usual. Within each treatment community, the aggregator would work with farmer groups, training them on post-harvest practices and providing them with inputs to increase yields and reduce aflatoxin levels, notably drying tarpaulins. Properly drying groundnuts on tarpaulins and effectively storing them in well aerated areas is a low-cost and effective way to reduce aflatoxin levels in groundnuts (Magnan et al. Citation2021; Strosnider et al. Citation2006; Turner et al. Citation2005; Zuza et al. Citation2018).

To select aggregators for the study, we searched for aggregators who met our criteria of having prior experience working with groundnut farmers, having adequate cash flow to supply inputs to farmers on credit and purchase large quantities of groundnuts after harvest, being willing to pay farmers a premium for low aflatoxin groundnuts, having a good storage facility, being capable of transporting large quantities of groundnuts, and being willing to enter a purchase agreement with a premium processor. To identify such aggregators, we talked with a number of people with experience in the groundnut sector in Northern Ghana, including farmers, aggregators, processors, scholars, consultants, and NGO workers.Footnote10 We interviewed 12 different aggregators in person and/or over the phone to confirm whether they fit our criteria.

We set out to work with a processor that required low-aflatoxin groundnuts and was willing to procure them through an aggregator rather than purchase them on the wholesale spot market. Ideally, the processor would be able to provide cash up front to aggregators to facilitate large purchases. We began the project with a certain processor in mind, but also engaged with other processors that produce a variety of groundnut products for the formal market within Ghana and for export.

Before implementing a complex RCT that would entail many transactions between one or more aggregators and hundreds of farmers, and at least one large transaction between an aggregator and a processor, we piloted a single transaction between an aggregator and a processor seeking low-aflatoxin groundnuts produced by smallholder farmers. Unfortunately, our pilot attempts were not successful in establishing a viable proof of concept that we could scale up for the planned RCT. The remainder of this section describes our attempts and how they broke down.

3.1. 2019 groundnut harvest

Our first attempted purchase agreement was between a large agricultural aggregator based in Accra (‘Aggregator 1’) and a large groundnut paste processor with high safety standards (‘Processor A’). Aggregator 1 mostly aggregates rice, but had aggregated groundnut in the past, including for Processor A. Processor A supplies specialised groundnut paste to the Ghanaian government for school feeding programs and also for export. They therefore must adhere to strict aflatoxin standards. In previous years, they imported groundnuts from the US to ensure low aflatoxin levels. Prior to the study, they transitioned to sourcing domestically and engaging in costly sorting processes to meet standards.

The first purchase agreement between Aggregator 1 and Processor A was for 20 MT of groundnuts, approximately one-fifth of Processor A’s annual requirement. Prior to harvest, the research team worked with Aggregator 1 to identify groundnut producing villages from which they would procure groundnuts. Based on past experience with farmers defaulting on input loans, Aggregator 1 was not willing to provide tarpaulins or any inputs on credit. The research team covered the cost of the tarpaulins and assisted Aggregator 1 in training farmers. During training, farmers were told that Aggregator 1 would return to purchase groundnuts at a good price (without specifics) because they would be high quality. The farmers and Aggregator 1 had no prior business interactions.

Uncertainty over the post-harvest market price led to difficulties agreeing on a price before harvest. Aggregator 1 asked the processor to pay 9 GhS/kg, approximately 3 GhS/kg over the expected market price and 1.5 GhS/kg above what Processor A was willing to pay. In order to increase the likelihood of a successful transaction between Aggregator 1 and Processor A, the research team agreed to cover the 1.5 GhS/kg difference. While this action on behalf of the research team calls into question whether future transactions could be made without it, we felt it was necessary to build trust and experience between the two parties and establish a proof of concept. Aggregator 1 and Processor A were unable to finalise negotiations until January of 2020, three months after harvest. Once the terms of the agreement were finalised, Aggregator 1 informed us that they would not have the cash to begin purchasing groundnuts from farmers until an unrelated rice sale was completed. During this time, Processor A became doubtful of Aggregator 1’s ability to fulfill the agreement and began purchasing groundnuts from local markets at a low price. Aflatoxin risk did not pose a problem to Processor A because levels of the contaminant were generally low that year. At this point, Processor A terminated the purchase agreement with Aggregator 1, stating that they no longer needed groundnuts.

Following the breakdown between Aggregator 1 and Processor A, the research team and Aggregator 1 met with two large processors in Accra to attempt a second purchase agreement for the 2019 harvest, despite it being long after harvest. Both processors, ‘Processor B’ and ‘Processor C’, stated that they imported groundnuts from Burkina Faso because it was cheaper and lower risk than purchasing within Ghana.Footnote11 Surprisingly, Processor B, an exporter of branded groundnut snacks (within Africa), did not know if they tested for aflatoxin. Their quality concerns were that groundnuts be of uniform size, not shrivelled, and white skinned (as opposed to the red skinned groundnuts predominantly grown in Northern Ghana). The lack of concern over aflatoxin and need for white-skinned groundnuts led us to believe Processor B would not be a suitable partner for the project.

Processor C reported sorting out 50 percent of the groundnuts they import to meet quality standards. Nevertheless, they said it was less expensive to import groundnuts than to source them domestically. Previous experiences with aggregators made Processor C apprehensive about working with Aggregator 1 without a legally binding purchase agreement. The processor also expressed concern about working with a research team and over whether the working relationship would continue after the study. Aggregator 1 expressed concern over Processor C importing instead of honouring the purchase agreement, and also over the possibility that Processor C would reduce the size of the purchase if consumer demand for their product was low. Ultimately, Processor C declined to enter a purchase agreement because they lacked contracts with retailers that would ensure a need for large quantities of groundnuts.

At this point we turned our attention to smaller processors that do not import. We contacted three such processors who all explained that they cannot engage in the types of large purchase agreements that are advantageous to aggregators. Thus, we went back to Processor A to establish a smaller purchase agreement in the hopes this could lead to larger ones in the future.

In February of 2020, four months after harvest, Aggregator 1 and Processor A established a second purchase agreement for 5 MT at 5.8 GhS/kg – slightly above the spot market price – with the research team paying an additional 4.2 GhS/kg to Aggregator 1 to cover expected costs of training and aggregation. A member of the research team accompanied Aggregator 1 to conduct aflatoxin testing with farmers. The groundnuts tested well below the allowable limit and would require little to no sorting. Despite Aggregator 1 having provided training and tarpaulins (or perhaps because of it), the farmers demanded well above the prevailing market price. Furthermore, many farmers had already sold much of their harvest by this time. In the end, Aggregator 1 only managed to purchase 166 kg of groundnuts, forcing them to terminate the purchase agreement with Processor A.

Our attempts to establish a sale from the 2019 groundnut harvest ultimately failed due to a combination of the three factors described above. Price uncertainty led to delays in finalising a purchase agreement, and lower than expected aflatoxin levels and market prices made the purchase agreement less beneficial for Processor A, making it easy for them to terminate. Aggregator 1’s cash constraint prevented them from purchasing groundnuts from farmers in a timely manner. Processor A’s cash constraint made them unable to afford the groundnuts at the agreed upon price after the delay in delivery. A lack of trust delayed or prevented most aggregators and processors from entering purchase agreements in the first place. Aggregator 1 did not trust that any of the processors would follow through with the purchase agreement, fearing they would instead import or purchase on the spot market. The processors did not trust that Aggregator 1 would deliver the specified quantity and quality of groundnuts. Finally, it also turned out that Aggregator 1 was justified in not trusting the farmers to sell at a reasonable price after giving them tarpaulins and training.

We should reiterate here that the purchase agreements we attempted to establish were very small. They did not require a massive cash outlay, and were intended to build trust so that larger agreements could be made in the future. Though we were concerned that we could not even facilitate a small purchase agreement for premium groundnuts, we opted to try again the following season.

3.2. 2020 groundnut harvest

For the 2020 harvest, we identified an aggregator working out of the Upper West region, ‘Aggregator 2’, through an international NGO. At the time, Aggregator 2 was working with the NGO on a project to improve groundnut quality and connect smallholder farmers to markets. Aggregator 2 had longstanding relationships with hundreds of smallholder farmers, had made large sales to processors in the past, had good storage facilities, and importantly, had a line of credit from the NGO to provide inputs to farmers. While credit from NGOs for aggregators is not common, it could be possible for processors to provide credit for this purpose once trust and a trading relationship is established. Importantly, Aggregator 2 had experience with aflatoxin-mitigating technologies. Despite Aggregator 2’s scepticism about processors honouring their end of the contract, they agreed to work with Processor A. We facilitated a purchase agreement between Aggregator 2 and Processor A, and they settled on a quantity of 100 MT. Consistent with our previous experience, Aggregator 2 and Processor A struggled to agree on price, or even a price premium, before harvest, with Aggregator 2 saying it was too risky to do so before the market price was known.

At the start of the 2020 groundnut season, Aggregator 2 provided seed, land preparation, and fertiliser to farmer groups on credit. The research team purchased tarpaulins and worked with Aggregator 2 to provide training on post-harvest practices to the farmers. After harvest, the research team tested the farmers’ groundnuts for aflatoxin, and they were again extremely low. Knowing this, Aggregator 2 set their price at 15 GhS/kg, nearly triple the market price at the time, believing the groundnuts their farmers produced were uniquely low in aflatoxin and claiming to have an exporter that would pay that price if Processor A would not. The high asking price and threat to leave the purchase agreement created considerable tension with Processor A. We discussed the price with Aggregator 2 at length, explaining that Processor A could simply purchase groundnuts on the market and sort if necessary, and managed to reduce their asking price to 9 GhS/kg – still nearly twice the market price. Because of their commitment to the research project, Processor A reluctantly accepted this price. However, they stated they would not work with the Aggregator 2 again.Footnote12 Given that this transaction would not lead to future ones, we encouraged Processor A to terminate the purchase agreement and ended our interactions with Aggregator 2.

Having the NGO provide credit to Aggregator 2 resolved the cash flow issue, but price uncertainty and a lack of trust still prevented a sale. After two years of purchase agreements failing due to recurring issues of uncertainty, cash flow constraints, and a lack of trust, we decided it would not be possible to build the necessary relationships to develop a premium groundnut value chain from farmer to aggregator to processor in Northern Ghana within the time horizon of our research project.

4. Lessons for future value chain interventions and research

The experiences described above indicate that overcoming one or even multiple obstacles to value chain development may not be enough. The research team provided inputs and aflatoxin testing in the field to remove uncertainty over quality and worked with an aggregator who was well financed to prevent cash flow constraints. Furthermore, we subsidised prices to bridge the gap between aggregators and processors. Whether the market price turned out to be high or low, our subsidy would increase the likelihood that processors and aggregators would face an advantageous price, and that the aggregator would be able to pass some of the premium on to farmers. However, several problems remained. In both years, aflatoxin levels in groundnuts available in the market were low enough that processors could easily abandon a purchase agreement, putting the aggregator at risk. Low levels of trust persisted throughout the value chain. Aggregators could not trust farmers, and aggregators and processors could not trust each other. In most cases this lack of trust seems justified, in large part due to uncertainty and cash flow problems beyond the control of any agent.

Here we propose three possible interventions for the development of premium groundnut value chains in Ghana. The first is to use a flexible contract design. Instead of a pre-determined price and quantity (e.g. 7 GhS/kg for 100 MT of groundnuts), the purchase agreement could use a pre-determined premium based on the market price and a quantity range. This would reduce price risk for both aggregators and processors, increase the speed at which purchase agreements are made, and prevent price disagreements. We did suggest this possibility to Aggregator 2, but they wanted to wait until after harvest to make any agreements pertaining to price. Nevertheless, we think these types of agreements merit further exploration. The literature on contracts under price uncertainty focuses on quantity-flexible contracts (Tsay Citation1999), options (Cheng et al. Citation2003), and risk-sharing (Li and Kouvelis Citation1999). These studies all involve more developed value chains; there exist little research on contract structure in emerging value chains.

The second intervention is vertical integration. Large processors can invest directly in their own value chain to diminish the role of aggregators. Vertical integration removes problems associated with the lack of trust between aggregators and processors, although trust issues with farmers could remain. Indeed, several processors we spoke with showed interest in directly purchasing from farmers after multiple failed purchase agreements and poor experiences transacting with aggregators.Footnote13 Vertical integration can provide more supply and demand assurance than informal contract arrangements (Macchiavello and Miquel-Florensa Citation2017) and allow for quality control. Partial vertical integration in the Ghanaian pineapple industry allowed processors and exporters to maintain strict quality control while spreading export risk among multiple smallholder producers (Suzuki, Jarvis, and Sexton Citation2011).

Although partial vertical integration has seen success in the Ghanaian pineapple sector, there remain several advantages to the aggregator model. While it may be possible for processors to work directly with large farmers, this could exclude smallholders from these value chains, or position large out-growers as de facto aggregators. Aggregators have the advantage of geographical, and in some instances social, proximity to farmers. This could reduce the risk of side selling by farmers. Aggregators also provide local storage and logistics support. With vertical integration, these functions would all fall on the processor, who may not be well positioned to perform them.

The third intervention is a transparent and competitive market for purchase agreements. Multiple aggregators and processors in the premium groundnut market would present publicly visible bids to facilitate matches between buyer and seller. We believe that such a market would speed up purchase agreements, whether they occur before or after harvest. Such a market would also make it easier for processors to engage in multiple purchase agreements to reduce their exposure to contract risk. This would also prevent aggregators from acting as monopolists and renegotiating prices after harvest. Aggregators could also benefit from engaging in several purchase agreements with different processors for the same reason. Aggregators and processors could use this market to experiment with different counterparts and build longer relationships based on their experiences.

While we believe a market for purchase agreements would reduce risk in the groundnut value chain and eventually lead to more trust, intermediaries can act in an anti-competitive manner. Bergquist and Dinerstein (Citation2020) find that intermediaries in Kenya collude, leading to higher profits for traders at the expense of both the producer and the consumer. They find that lowering barriers to entry for traders does not necessarily remedy the problem, as traders were able to maintain their monopolistic pricing even after more traders entered the market. Chau, Goto, and Kanbur (Citation2016) find that wholesale wheat traders in Ethiopia can collude to lower the price paid to farmers in small markets, but not large ones, demonstrating the importance of having many aggregators and processors present in the market.

5. Conclusion

Empirical research on value chain development is difficult. Observational studies are prone to bias and lack internal validity. Randomized control trials are logistically complex and require substantial third party involvement. We set out to overcome what we believed was the primary barrier to groundnut value chain development in Ghana, uncertainty over quality, by providing aflatoxin-mitigating inputs to farmers and aflatoxin testing to aggregators and processors. However, other issues remained. Price uncertainly, cash flow constraints, and a lack of trust between groundnut value chain actors continued to prevent the creation and execution of purchase agreements between aggregators and processors. Subsidizing transactions to ensure an acceptable price for both parties did not solve the problem, nor did working with an aggregator with adequate cash flow.

In an environment where contract enforcement is limited due to an under-developed legal system, other mechanisms are required to overcome uncertainty and a lack of trust. Possibilities include flexible contracts to reduce the risk of uncertainty in the groundnut market, vertical integration to mitigate mistrust and potential cash flow problems, and a competitive market for purchase agreements to reduce the risks agents face in transacting with one single party.

Acknowledgements

This study is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through Cooperative Agreement No. 7200AA 18CA00003 to the University of Georgia as management entity for US Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Peanut (2018-2023). The study also received support from the CGIAR One Health Initiative, supported by contributors to the CGIAR Trust Fund. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Institutional Review Board Approval was granted by the University of Georgia (Project 00002288) and the University for Development Studies. We thank Avery Grau, Dave Hoisington, Mark Manary, and Jamie Rhoads for their valuable input and commitment to this project. Josh Deutschmann, Jeff Michler, and two anonymous referees provided helpful comments on the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest. All errors are solely the authors’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sean Posey

Sean Posey is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural an Environmental Sciences at Tennessee State University.

Nicholas Magnan

Nick Magnan is Associate Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics at Colorado State University and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Georgia.

Ellen B. McCullough

Ellen McCullough is an Assistant Professor in the Agricultural and Applied Economics Department at the University of Georgia.

Vivian Hoffmann

Vivian Hoffmann is an Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Carleton University and a Senior Research Fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Nelson Opoku

Nelson Opoku (PhD) is a senior lecturer in Plant Pathology at the Department of Biotechnology and Molecular Biology, University for Development Studies.

Abdul-Hafiz Alidu

Abdul-Hafiz Alidu is a graduate with an MS in Biological and Environmental Science from the University of Jyväskylä.

Notes

1. Publication bias refers to the phenomenon that studies, particularly observational studies, showing null results do not get published. Survivor bias occurs because only value chain arrangements that are successful enough to survive for several years are typically analysed using observational data.

2. Several factors could have prevented more farmers from selling at the premium price in the first year: poor timing of the purchase visit, limited flexibility of the date of sale, a confusing and/or inadequate premium, and mistrust since this was the first time such an offer was made. In the second year, the premium was higher and more transparent, and the purchase date more flexible. See Magnan et al. (Citation2021) for details.

3. Tasila and Mabe (Citation2023) report that groundnut farmers in the Northern region sell 62% of their production.

4. Personal communication with Market Oriented Agriculture Program in Upper West Region, January 2020, and with Outgrower Business leaders in Northern Region, January 2023.

5. Magnan et al. (Citation2021) report that average groundnut area in the study region is 2.5 acres and average production is 376 kg.

6. Esoko ceased to publish data after October 2020.

7. One farmer stated, ‘I won’t sell all of my groundnuts or agree to sell all of my groundnuts unless an aggregator has invested in my farming and provided inputs to improve my production’ (pers. comm., January 2020).

8. One aggregator complained, ‘Farmers always think aggregators have all this money and that they should be the ones taking all the risk and helping them no matter what. That is why I can’t find any farmers to continue to work with’ (pers. comm., March 2020). Two processors expressed similar frustration about aggregators demanding that processors take on all the risk involved with providing inputs to farmers.

9. Personal communication with farmers and aggregators, January 2020.

10. The Market Development Program for Northern Ghana (https://ghana-made.orghttps://ghana-made.org) provided the most extensive list of aggregators.

11. Processor C stated that, ‘I used to export to the EU, but have consistently failed aflatoxin tests. Due to this I have switched and have begun sourcing groundnuts from Burkina Faso because they are higher quality’ (pers. comm., January 2020).

12. In our interactions with Aggregator 2, we found them to frequently exhibit aggressive and bullying behaviour to us, to Processor A, and to others.

13. Personal communication with processor, January 2020.

References

- Abate, G.T., T. Bernard, A. de Janvry, E. Sadoulet, and C. Trachtman. 2021. “Introducing Quality Certification in Staple Food Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa: Four Conditions for Successful Implementation.” Food Policy 105:102173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102173.

- Arouna, A., J.D. Michler, and J.C. Lokossou. 2021. “Contract Farming and Rural Transformation: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Benin.” Journal of Development Economics 151:102626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102626.

- Ashraf, N., X. Giné, and D. Karlan. 2009. “Finding Missing Markets (And a Disturbing Epilogue): Evidence from an Export Crop Adoption and Marketing Intervention in Kenya.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 91 (4): 973–990. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2009.01319.x.

- Barrett, C.B., T. Reardon, J. Swinnen, and D. Zilberman. 2022. “Agri-Food Value Chain Revolutions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” Journal of Economic Literature 60 (4): 1316–1377. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201539.

- Bellemare, M.F., and J.R. Bloem. 2018. “Does Contract Farming Improve Welfare? A Review.” World Development 112:259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.018.

- Bergquist, L.F., and M. Dinerstein. 2020. “Competition and Entry in Agricultural Markets: Experimental Evidence from Kenya.” American Economic Review 110 (12): 3705–3747. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171397.

- Bernard, T., A. De Janvry, S. Mbaye, and E. Sadoulet. 2017. “Expected Product Market Reforms and Technology Adoption by Senegalese Onion Producers.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99 (4): 1096–1115. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aax033.

- Bold, T., S. Ghisolfi, F. Nsonzi, and J. Svensson. 2022. “Market Access and Quality Upgrading: Evidence from Four Field Experiments.” American Economic Review 112 (8): 2518–2552. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210122.

- Chau, N.H., H. Goto, and R. Kanbur. 2016. “Middlemen, Fair Traders, and Poverty.” The Journal of Economic Inequality 14 (1): 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-015-9314-2.

- Cheng, F., M. Ettl, G.Y. Lin, M. Schwarz, and D.D. Yao. 2003. Flexible Supply Contracts via Options. Technical Report. Yorktown Heights, NY, USA: IBM TJ Watson Research Center.

- DAI. 2014. DFID Market Development (MADE) in Northern Ghana Programme. Technical Report. London: Department for International Development.

- Deutschmann, J.W., T. Bernard, and O. Yameogo. 2023. Contracting and Quality Upgrading: Evidence from an Experiment in Senegal. Working Paper. University of Chicago.

- de Vries, J., J.A. Turner, S. Finlay-Smits, A. Ryan, and L. Klerkx. 2023. “Trust in Agri-Food Value Chains: a Systematic Review.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 26 (2): 175–197. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2022.0032.

- Grosh, B. 1994. “Contract Farming in Africa: An Application of the New Institutional Economics.” Journal of African Economies 3 (2): 231–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jae.a036805.

- Hoffmann, V., S. Kariuki, J. Pieters, and M. Treurniet. 2023. “Upside Risk, Consumption Value, and Market Returns to Food Safety.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 105 (3): 914–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12349.

- IARC. 1993. Some Naturally Occurring Substances: Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins. Technical Report. Geneva: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Jordan, D., W. Appaw, W. O Ellis, R. Akromah, M.B. Mochiah, M. Abudulai, R.L. Brandenburg, J. Jelliffe, B. Bravo-Ureta, and K. Boote. 2020. “Evaluating Improved Management Practices to Minimize Aflatoxin Contamination in the Field, During Drying, and in Storage in Ghana.” Peanut Science 72–88. https://doi.org/10.3146/PS20-3.1.

- Karlan, D., and J. Appel. 2017. Failing in the Field: What We Can Learn When Field Research Goes Wrong. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

- Li, C.L., and P. Kouvelis. 1999. “Flexible and Risk-Sharing Supply Contracts Under Price Uncertainty.” Management Science 45 (10): 1378–1398. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.45.10.1378.

- Liu, Y., C.C.H. Chang, G.M. Marsh, and F. Wu. 2012. “Population Attributable Risk of Aflatoxin-Related Liver Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Cancer 48 (14): 2125–2136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.009.

- Liu, Y., and F. Wu. 2010. “Global Burden of Aflatoxin-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Risk Assessment.” Environmental Health Perspectives 118 (6): 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0901388.

- Macchiavello, R., and J. Miquel-Florensa. 2017. Vertical Integration and Relational Contracts: Evidence from the Costa Rica Coffee Chain. Discussion Paper No. DP11874. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research.

- Magnan, N., V. Hoffmann, N. Opoku, G. Gajate Garrido, and D.A. Kanyam. 2021. “Information, Technology, and Market Rewards: Incentivizing Aflatoxin Control in Ghana.” Journal of Development Economics 151:102620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102620.

- Masters, W.A., S. Ghosh, J.A. Daniels, and D.B. Sarpong. 2013. Comprehensive Assessment of the Peanut Value Chain for Nutrition Improvement in Ghana. Technical Report. Boston, MA, USA and Geneva: Tufts University and GAIN.

- Meemken, E.M., and M.F. Bellemare. 2020. “Smallholder Farmers and Contract Farming in Developing Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (1): 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909501116.

- Miller, C. 2012. Agricultural Value Chain Finance Strategy and Design. Technical Report. Rome: International Fund for International Development.

- Minot, N., and B. Sawyer. 2016. “Contract Farming in Developing Countries: Theory, Practice, and Policy Implications.” In Innovations for Inclustive Value Chain Development, edited by A. Devaux, M. Torereo, J. Donovan, and D. Horton, Chap 4. 127–155. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Mutiga, S.K., V. Hoffmann, J.W. Harvey, M.G. Milgroom, and R.J. Nelson. 2015. “Assessment of Aflatoxin and Fumonisin Contamination of Maize in Western Kenya.” Phytopathology 105 (9): 1250–1261. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-10-14-0269-R.

- Mutiga, S.K., V. Were, V. Hoffmann, J.W. Harvey, M.G. Milgroom, and R.J. Nelson. 2014. “Extent and Drivers of Mycotoxin Contamination: Inferences from a Survey of Kenyan Maize Mills.” Phytopathology 104 (11): 1221–1231. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-01-14-0006-R.

- Narh, S., K.J. Boote, J.B. Naab, M. Abudulai, Z. M’Bi Bertin, P. Sankara, M.D. Burow, B.L. Tillman, R.L. Brandenburg, and D.L. Jordan. 2014. “Yield Improvement and Genotype× Environment Analyses of Peanut Cultivars in Multilocation Trials in West Africa.” Crop Science 54 (6): 2413–2422. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2013.10.0657.

- Ortmann, G.F., and R.P. King. 2007. “Agricultural Cooperatives I: History, Theory and Problems.” Agrekon 46 (1): 40–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2007.9523760.

- Owusu-Adjei, E., R. Baah-Mintah, and B. Salifu. 2017. “Analysis of the Groundnut Value Chain in Ghana.” World Journal of Agricultural Research 5 (3): 177–188. https://doi.org/10.12691/wjar-5-3-8.

- Porter, G., and K. Phillips-Howard. 1997. “Comparing Contracts: An Evaluation of Contract Farming Schemes in Africa.” World Development 25 (2): 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00101-5.

- Reardon, T., C.B. Barrett, J.A. Berdegué, and J.F.M. Swinnen. 2009. “Agrifood Industry Transformation and Small Farmers in Developing Countries.” World Development 37 (11): 1717–1727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.023.

- Reardon, T., and C. Peter Timmer. 2007. “Transformation of Markets for Agricultural Output in Developing Countries Since 1950: How Has Thinking Changed?” Handbook of Agricultural Economics 3:2807–2855. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0072(06)03055-6%3Dihub.

- Reardon, T., C. Peter Timmer, C.B. Barrett, and J. Berdegué. 2003. “The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85 (5): 1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00520.x.

- Saenger, C., M. Torero, and M. Qaim. 2014. “Impact of Third-Party Contract Enforcement in Agricultural Markets—A Field Experiment in Vietnam.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 96 (4): 1220–1238. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau021.

- Strosnider, H., E. Azziz-Baumgartner, M. Banziger, R.V. Bhat, R. Breiman, M.N. Brune, K. DeCock, et al. 2006. “Workgroup Report: Public Health Strategies for Reducing Aflatoxin Exposure in Developing Countries.” Environmental Health Perspectives 114 (12): 1898–1903. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9302.

- Suzuki, A., L.S. Jarvis, and R.J. Sexton. 2011. “Partial Vertical Integration, Risk Shifting, and Product Rejection in the High-Value Export Supply Chain: The Ghana Pineapple Sector.” World Development 39 (9): 1611–1623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.02.007.

- Tasila, D., and F.N. Mabe. 2023. “Market Participation of Smallholder Groundnut Farmers in Northern Ghana: Generalised Double-Hurdle Model Approach.” Cogent Economics & Finance 11 (1): 2202049. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2202049.

- Ton, G., W. Vellema, S. Desiere, S. Weituschat, and M. D’Haese. 2018. “Contract Farming for Improving Smallholder Incomes: What Can We Learn from Effectiveness Studies?” World Development 104:46–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.015.

- Tsay, A.A. 1999. “The Quantity Flexibility Contract and Supplier-Customer Incentives.” Management Science 45 (10): 1339–1358. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.45.10.1339.

- Turner, P.C., A. Sylla, Y. Yun Gong, M.S. Diallo, A.E. Sutcliffe, A.J. Hall, and C.P. Wild. 2005. “Reduction in Exposure to Carcinogenic Aflatoxins by Postharvest Intervention Measures in West Africa: A Community-Based Intervention Study.” The Lancet 365 (9475): 1950–1956. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66661-5.

- Upton, J., and E. Lentz. 2017. “Finding Default? Understanding the Drivers of Default on Contracts with Farmers’ Organizations Under the World Food Programme Purchase for Progress Pilot.” Agricultural Economics 48 (S1): 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12385.

- Wang, H.H., Y. Wang, and M.S. Delgado. 2014. “The Transition to Modern Agriculture: Contract Farming in Developing Economies.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 96 (5): 1257–1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau036.

- Weatherspoon, D.D., and T. Reardon. 2003. “The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa: Implications for Agrifood Systems and the Rural Poor.” Development Policy Review 21 (3): 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00214.

- Williams, J.H., T.D. Phillips, P.E. Jolly, J.K. Stiles, C.M. Jolly, and D. Aggarwal. 2004. “Human Aflatoxicosis in Developing Countries: A Review of Toxicology, Exposure, Potential Health Consequences, and Interventions.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80 (5): 1106–1122. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1106.

- Zuza, E.J., A. Muitia, M.I.V. Amane, R.L. Brandenburg, A. Emmott, and A.M. Mondjana. 2018. “Effect of Harvesting Time and Drying Methods on Aflatoxin Contamination in Groundnut in Mozambique.” Journal of Postharvest Technology 6 (2): 90–103.