?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A growing literature in economics has analysed the effects of psychological interventions designed to boost individual aspirations as a strategy to increase households’ propensity to make long-term investments and thus reduce poverty. This paper reports on a randomised controlled trial evaluating a short video-based intervention designed to increase aspirations of adults in poor rural Ethiopian households who are beneficiaries of the Productive Safety Net Program, the main government safety net program in Ethiopia. Evidence from a sample of 5,258 adults from 3,220 households is consistent with the hypothesis that there are no significant effects of the intervention on self-reported aspirations for the household, educational investment in children, or savings nine months post-treatment. This suggests that the effect of light-touch aspirations treatments for extremely poor adults may be limited in this context.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increased focus in the economics literature on the interplay between psychology and economic decision-making, and the role of poverty in shaping this interplay. Theorists have identified multiple channels through which excessively low or excessively high aspirations can discourage investment: households with excessively low aspirations may lose interest in shifting their long-term income trajectory or, at the other extreme of excessively high aspirations, may become discouraged about the prospects of ever reaching an unrealistically high target level of income (Genicot and Ray Citation2017). This has led to models of an ‘aspirations poverty trap’ in which low aspirations are both a product of poverty and an additional constraint that limits exit – suggesting that directly targeting increased aspirations may be effective in facilitating households’ economic advancement (Dalton, Ghosal, and Mani Citation2016).

In development economics, a small but growing empirical literature has analysed the effect of interventions that directly or indirectly target enhanced aspirations and associated economic behaviours (Bernard et al. Citation2014, Citation2019; Ghosal et al. Citation2022; Wydick, Glewwe, and Rutledge Citation2013). In addition to their theoretical promise, cognitive or psychological interventions aimed at enhancing aspirations, self-esteem or self-belief are attractive because they are relatively low-cost to implement at scale. Targeting the ‘aspirations poverty trap’ may thus be a cost-effective strategy for poverty alleviation.

In this paper, we provide evidence about the effectiveness of an aspirations intervention implemented for a low-income rural sample in the context of a multiarm randomised controlled trial evaluating nutrition and livelihoods interventions targeting beneficiaries of Ethiopia’s main social safety-net program, the Productive Safety Net Program. The evaluation is implemented in collaboration with the Strengthen PSNP4 Institutions and Resilience (SPIR) program, and evaluates a video that shares stories of successful journeys out of poverty by other rural households. The sample includes 3,220 households in 192 kebeles in two regions of Ethiopia; 1,012 households were invited to attend a one-time screening of these documentaries, and their stated aspirations and economic behaviours were measured in a large-scale survey approximately nine months later.Footnote1 The experimental design allows us to estimate multiple experimental effects of interest, comparing households exposed to aspirations programming and other livelihoods interventions to households who received similar interventions without exposure to the aspirations video itself; and also comparing these households to a control arm in which households received PSNP transfers only.

The results suggest that there is almost no evidence of any significant effect of the intervention on stated aspirations or related economic behaviours. Administrative data reports attendance at the screening was high (around 90%), but recall as of the survey date is meaningfully lower (around 50% of households recall that they attended the screening), suggestive of potentially limited salience. In addition, there is no evidence of any shift in stated aspirations for education of the household’s eldest child, or aspired level of income or assets in ten years, for the pooled sample or the sample of men and women. Similarly, there is no evidence of any effect on educational enrolment or attendance for children, or other measures linked to potentially long-term investment by households (e.g. savings and livestock investment). The precision of the estimated effects varies: in some specifications, we can rule out effects as small as a two percentage point increase in educational aspirations, while in some specifications, the confidence interval is considerably wider and thus we cannot rule out a large, but imprecisely estimated, effect.

These results join an existing literature examining the effects of interventions seeking to enhance participants’ aspirations. Bernard et al. (Citation2014) and Bernard et al. (Citation2019) reported findings from an evaluation of the same video screening also implemented in rural Ethiopia and found much larger and more statistically significant positive effects. Recall of and positive attitudes towards the screening were high, and there were significant effects on self-reported adult aspirations as well as economic behaviours (in particular, there were large effects on school enrolment for children, an increase of more than 20% in the average number of children enrolled per household). In Kenya, another recent randomised trial found positive effects of an aspirations workshop (inclusive of a video element as well as other additional exercises) for a sample of poor rural households on a range of economic outcomes; there were, however, no additional effects of the aspirations intervention for a subsample that had already received large cash transfers valued at more than $2000 in purchasing power parity terms (Orkin et al. Citation2023).

Two other recent papers reported on randomised controlled trials that targeted related specific subsamples, HIV-positive women in Uganda and sex workers in Kolkata. In Uganda, a video presenting the stories of HIV positive role models led to increased engagement in businesses as well as increased income (Lubega et al. Citation2021). In Kolkata, an intervention targeting sex workers was designed to mitigate stigma and enhance self-image, a concept related to though clearly not identical to enhancing aspirations; the analysis found evidence of significant improvement in respondents’ self-image, as well as increases in savings and health behaviours (Ghosal et al. Citation2022). By contrast (Baranov, Haushofer, and Jang Citation2020), analysed several light-touch positive psychology interventions targeting poor adults in urban Kenya, including one targeting aspirations, and found no positive effects on psychological well-being or decision-making.

A much larger literature has analysed related interventions targeting children’s aspirations (Wydick, Glewwe, and Rutledge Citation2013). evaluated an international child sponsorship program and found significant effects on educational and employment outcomes in adulthood, arguing that this reflects partly an increase in aspirations. However, the program of interest included substantial material transfers to the child, as well as intensive weekly programming over as long as nine years designed to enhance the target children’s socioemotional development. By contrast, two recent large-scale evaluations of ‘growth-mindset interventions’ designed to increase students’ self-efficacy and investment in education in Argentina and Peru found generally null effects (Ganimian Citation2020; Outes-León, Alan, and Vakis Citation2020). A role model intervention targeting aspirations among youth in Somalia also was unsuccessful in increasing higher education aspirations, though there was some effect of female role models on gender norms (Serra et al. Citation2021).

There is also a growing literature analysing the effects of various forms of training in life skills or non-cognitive skills on educational, social, and labour market outcomes of children and youth (Acevedo et al. Citation2020; Ashraf et al. Citation2020; Bhanot et al. Citation2020; Blattman, Jamison, and Sheridan Citation2017; Edmonds, Feigenberg, and Leight Citation2021; Ganimian et al. Citation2020; Groh et al. Citation2016). While the content of these trainings or interventions varies, enhancing aspirations is often an important intermediate goal, and aspirations are generally a measured outcome. An earlier literature review found evidence that this form of training can generally have positive effects on labour market outcomes, in contrast to more traditional skills training programs (Blattman and Ralston Citation2015), and recent papers have presented evidence of positive effects on educational outcomes as well in both Zambia and India (Ashraf et al. Citation2020; Edmonds, Feigenberg, and Leight Citation2021). However, these are more intensive forms of programming entailing extended interaction with participants over a period of weeks, months or years. In addition, these programs did not target adults, and many were implemented in urban and periurban areas.

Our paper contributes to this literature by providing new evidence around the effects of an aspirations intervention targeting a population that is underrepresented in the existing literature – extremely poor adults (SPNP beneficiaries are generally the poorest 10—15% of households), predominantly engaged in subsistence agriculture – and documenting the effects on a wide range of outcomes of interest. We also contribute by analysing aspirations interventions when implemented in conjunction with integrated livelihoods programming inclusive of a large cash transfer, joining recent evidence from Kenya (Orkin et al. Citation2023). In general, the results here suggest the importance of caution in designing light-touch interventions designed to enhance aspirations, as the positive results reported in other papers are not replicated here.

2. Context and experimental design

2.1. Overview of the evaluation

This paper reports on interventions implemented as part of the Strengthen PSNP4 Institutions and Resilience (SPIR) program in Ethiopia, a five-year project designed to support implementation of the fourth phase of the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP4) as well as provide complementary programming. The PSNP is one of the largest safety net programs in sub-Saharan Africa, now serving eight million people annually. It provides cash and/or food transfers to rural households in the form of payment for labour on public works or direct transfers for households who do not have an eligible worker (Hoddinott and Mekasha Citation2020). The program is targeted both geographically (in districts that are often drought affected and chronically food-insecure) and at the household level, employing community-based targeting to select households that meet certain criteria, particularly food insecurity (Berhane et al. Citation2013). Evidence generally suggests that the PSNP itself has some modest effects on enhancing food security and assets but the effects are not large, in part because realised transfers do not match the intended level of transfers (Berhane et al. Citation2014; Gilligan, Hoddinott, and Seyoum Taffesse Citation2009).

As part of PSNP4, SPIR was led by World Vision in collaboration with the government of Ethiopia and funded by USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance.Footnote2 The broader SPIR project targeted nearly 500,000 beneficiaries in 15 vulnerable woredas in Amhara and Oromia regions, and its primary objectives were to enhance resilience to shocks and livelihoods and improve food security and nutrition for rural households. All households received resource transfers (cash and food) as part of PSNP4, in addition to supplemental interventions delivered by SPIR. In addition, SPIR was the focus of an experimental impact evaluation conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute designed to measure the causal impact of multisectoral graduation model interventions on multiple domains. Here, we provide a brief overview of the full experimental design while focusing primarily on the intervention targeting enhanced aspirations that is of interest for this analysis.

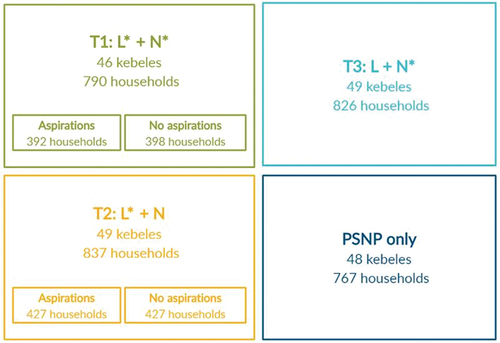

The full experimental design evaluates combinations of four interventions; N and L correspond to the primary interventions focused on nutrition and livelihoods, respectively, while N* and L* represent enhanced versions of these interventions. provides an overview of the design. There are three treatment arms; T1 includes L* and N* interventions, T2 includes L* and N, and T3 includes L and N * . In the control arm (denoted PSNP only), there is no targeted SPIR programming, but households do receive the base cash and food transfers as well as supplemental services under the government-led PSNP.

The SPIR health and nutrition package (N) includes integrated nutrition social behaviour change communication as well as water, sanitation and health education, supplemented by more targeted interventions at the household level in the N* arms.Footnote3 The SPIR livelihoods program (L) focuses on the establishment and development of VESAs, Village Economic and Social Associations, as well as improved access to finance and engagement in productive value chains. VESAs include both men and women and are used as a platform for trainings and other project activities around financial literacy, promotion of savings and credit use, agriculture and livestock value chain development, and catalysing women’s empowerment. In the L* arms, two additional interventions are rolled out.Footnote4 The first is targeted livelihoods transfers to the poorest households in each kebele, in the form of a one-time cash grant or a poultry package; these transfers are cross-randomised to the poorest 40% of households sampled in each kebele in the L* arms (T1 and T2). The second intervention is the primary focus of this paper: one-time screenings of short documentary films designed to motivate individuals to undertake actions that will improve their well-being in the future, and described in more detail in the next subsection.

The primary analysis here will focus on the cross-randomisation of the aspirations intervention within the T1 and T2 arms. Households exposed to the video screening can thus be compared to households who similarly received enhanced livelihoods programming but were not exposed to the screening, as well as to households in the T3 (L only) and control arms.

Randomisation into the four primary experimental arms was conducted at the kebele level, utilising stratification by woreda. The randomisation entailed a re-randomisation procedure in which 1000 possible assignments were generated, and each allocation was evaluated for balance with respect to key covariates (the population share of PSNP beneficiaries, and the distance from the kebele to the district capital). The randomisation characterised by the highest relative efficiency in covariate balance – the minimum maximum t-statistic – was retained (Alderman et al. Citation2019).Footnote5 For the second-stage randomisation within the L* arms, a similar procedure was implemented to randomly assign half the kebeles to receive aspirations programming. The procedure entailed rerandomisation to ensure balance across the number of aspirations and non-aspirations kebeles within T1 and T2, stratifying by woreda. Ultimately, 47 kebeles in these two arms were assigned to receive the aspirations treatment (23 in T1, and 24 in T2), while 48 kebeles not assigned to receive the aspirations treatment (23 in T1 and 25 in T2). again provides more details.

Ethical approval for this evaluation was received from the Institutional Review Board at IFPRI as well as the IRB at Hawassa University, one of the study partners.

2.2. Aspirations intervention

The primary intervention analysed here is a screening of documentaries in Amharic and Afaan Oromo that provide true, inspirational stories about the returns to hard work and the benefit of aiming high; this description of the intervention draws partly on Bernard et al. (Citation2014). The documentaries were developed by a team of researchers who identified four inspirational stories about individuals in rural Ethiopia who significantly improved their socio-economic well-being through their own planning and persistence. The four stories focus on two men and two women, and each is 15 minutes in length, rendering the whole screening an hour in duration.Footnote6 All four segments highlight individuals who were poor rural residents at baseline, and who used diverse strategies to increase their income (e.g. identifying new household businesses, or adopting enhanced farming practices); none of the four received significant interventions from government or non-governmental organisations. Broadly, the documentaries emphasise the importance of the featured individuals’ persistence and consistency in working towards their goals.

The theory of change for the intervention centres around the hypothesis that poor households living in poor communities may be characterised by systematically low aspirations – an absence of affirmative goals or hopes for a better future, towards which they can work step-by-step (Orkin et al. Citation2023). Closely related to low aspirations may be the absence of appropriate role models of other households or individuals who have been able to exit poverty, particularly in poorer or remote communities; given that the PSNP is geographically targeted towards exactly these communities, the absence of role models is highly plausible. By providing concrete examples of success stories and highlighting how this success stemmed from individuals’ own efforts and successes, the intervention seeks to encourage households to increase their goals and engage in forward-looking behaviour to achieve these goals.

In the kebeles in which aspirations programming was offered, SPIR staff visited each household in the sample and provided an invitation for the household (both husband and wife) to attend a scheduled screening of the documentary. (Accordingly, the screening was not a kebele-wide event open to all residents, and information was not disseminated publicly.) Administrative information on attendance recorded by program staff is available for 45 of 47 kebeles and Panel A of provides an overview of this data, enabling us to assess compliance with the experimental design.Footnote7 On average, approximately 18 households were invited to the screenings (corresponding to the SPIR survey sample), and slightly over 16 report that at least one adult attended, corresponding to an average attendance rate of 90%. However, it is not necessarily the case that both spouses attended the screenings; the average screening included attendance of around 13 men and 12 women. There are also nine kebeles in which implementing staff failed to explicitly include women in the invitations. In some cases women attended nonetheless, but the average number of women present was only four in these kebeles. (Average attendance by women in the remaining kebeles in which women were invited rises to 15, higher than average male attendance.) There were no reports of any individuals who were not invited (i.e. individuals from a control community) attempting to attend a screening.

Table 1. Attendance at aspirations screening.

The documentaries were screened in the selected kebeles only once, in December 2018. The screening was thus approximately nine months prior to the midline survey, details of which are provided in the next subsection.

2.3. Sample and data collection

The full sample for this evaluation includes 15 woredas in the Amhara and Oromia regions of Ethiopia; this is the full set of woredas in which SPIR is operational.Footnote8 Within these woredas, the evaluation includes 192 kebeles, comprising approximately all kebeles in which the PSNP operates and in which SPIR implementation activities had not yet been launched at the point of the baseline survey in January 2018.Footnote9 Households were eligible for inclusion in the sample if they were PSNP4 beneficiary households including a child aged 0—35 months, and if the child’s primary female caregiver was a household member, leading to a total sample of 3,314 households.Footnote10 Baseline surveys were conducted with this female caregiver (denoted the primary female) and a primary male respondent, usually the spouse of the primary female. All households were surveyed at baseline between January and April 2018, and targeted for follow-up between July and October 2019. The follow-up survey included 3,220 households, corresponding to an attrition rate of only 2.8 percent.

Surveying was conducted in the field by local survey firms, using data collection on tablets, and were administered in Amharic or Afaan Oromo as appropriate. Survey modules include detailed information about exposure to SPIR programming, household economic activities (cropping, livestock cultivation and outside labour), savings and credit utilisation, nutritional and health knowledge and practices, female empowerment and intimate partner violence, and aspirations.

3. Empirical analysis

3.1. Outcomes of interest

The primary objective of this analysis is to provide evidence about the effects of the interventions of interest on respondents’ aspirations as well as related variables that capture behavioural dimensions plausibly linked to aspirations. As noted in Section 2b, the theory of change for the intervention centres around encouraging participating households to raise their long-term goals, in principle, and engage in concrete forward-looking behaviours that may be linked to these goals, in practice. We thus seek to measure both the goal and any related behavioural steps.

The outcomes of interest were prespecified in the baseline report (Alderman et al. Citation2019). First, we analyse six variables linked to aspirations, each reported by both the male and the female respondents. Four binary variables capture whether the respondent’s aspired level of education for his or her eldest child is no education, primary education, secondary education, or post-secondary education. The respondent also states the aspired level of income and assets in ten years; these variables are converted to thousands of birr, and calculated as a log. (The aspired level of assets is only reported by the male respondent.) These variables capture whether respondents’ hypothetical aims have shifted (increased) after exposure to the intervention.

Second, we analyse several dimensions of forward-looking behaviour: investment in education and savings and loan behaviour, as well as (secondarily) engagement in wage work and livestock. Education is a canonical investment with long-term returns, particularly for rural households, and saving funds to facilitate future investment is similarly a plausible step towards a goal of higher income; these are also variables that were shown to be responsive to the same intervention when previously evaluated in Ethiopia (Bernard et al. Citation2014). Four educational variables are reported: a binary variable for whether a child is reported enrolled this academic year; binary variables for whether the child attended consistently this year, or more than 50% of days this year; and a continuous variable equal to the number of days the child is reported to have attended school in the last seven days. Eight variables capture household financial behaviour: whether the primary female in the household reports any savings; whether she reports any savings with a village savings and loan association and/or a microfinance institution; the amount of reported savings; whether the primary male reports any productive loan, and the amount of that loan; whether the primary male in the household reports a bank account; and whether the primary male reports a deposit with a rural savings and credit cooperative.

Variables capturing engagement in wage work and livestock are secondary outcomes of interest that may capture other steps households could take to diversify their livelihoods stream, with the objective of ultimately increasing income and exiting subsistence agriculture. In addition, investment in livestock assets could be a plausible alternate mode of savings given limited access to financial institutions. We identify these outcomes as secondary given that the mechanism for any intervention effect is more indirect.

3.2. Empirical specification

The empirical specification can be written as follows, estimating an intent-to-treat effect. The dependent variable of interest for individual i in household h in kebele v in woreda d is regressed on a binary variable for L* (encompassing both the first and second treatment arms T1 and T2), and the interaction between L* and the cross-randomised aspirations intervention, denoted Aspvd. A control for the baseline level of the outcome of interest (Yihvdt-1) is included, when available.Footnote11 All regressions include woreda fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the kebele level.

For each coefficient, we report both a standard p-value and a q-value adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing (Simes Citation1986).Footnote12

The primary coefficient of interest is β2, capturing the effect of the aspirations intervention relative to the other L* (and nutrition) interventions implemented in the treatment arms T1 and T2; the coefficient β1 captures the direct effect of these other interventions on aspirations.Footnote13 We also estimate the same specification for the subsample of extremely poor households who were eligible for cash or poultry transfers. This analysis is of particular interest given very recent evidence from Kenya, discussed in the literature review, that large cash transfers can have a direct positive effect on aspirations (Orkin et al. Citation2023).

While in our main specification we abstract from further variation in nutrition programming across the main treatment arms, we also estimate a fully saturated specification as a robustness check.

Again, we report both p-values and q-values for each of the estimated coefficients.

To assess baseline balance, we report the mean values across treatment arms for a subset of baseline demographic variables (a binary variable for whether the head of household reports any education, a binary variable for whether the primary female in the household reports any education, the age of the primary male and female, the number of children under five, and the baseline level of education for the eldest child, for whom aspirations will be reported). We also estimate the saturated regression specification (EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) ) for these variables and calculate the joint p-value corresponding to the test of the hypothesis that covariates are fully balanced across arms (β1 = β2 = β3 = β4 = β5 = 0).Footnote14 Consistent with the randomisation design, the results reported in suggest there is little evidence of any meaningful imbalance across treatment arms.

Table 2. Baseline balance.

4. Empirical results

provides evidence about respondents’ recall of the aspirations video screening. As previously noted, screenings were conducted in December 2018 while respondents were surveyed between August and October 2019. Self-reported data as of the midline survey suggests that approximately nine months following the screening, recall of the intervention has declined significantly. Only 41% of women and 51% of men in targeted kebeles report that they attended a video screening focusing on aspirations. (If we construct a household-level recall measure equal to one if either spouse reports recall of the intervention, the mean in the targeted kebeles is 60%.) While the slightly higher attendance among men is consistent with the administrative data in that women were not invited in some kebeles, in general self-reported attendance is significantly lower than reported administrative data (in which attendance was around 90%, as reported previously in Section 2b). This gap in self-reported recall of attendance vis-à-vis administratively reported attendance is suggestive of potentially limited salience of the intervention, or perceived low quality of the video screening.

There is also some reported contamination in kebeles that were not targeted for the aspirations intervention in the experimental arms T1 and T2 (as reported in Column C), and in kebeles in arm T3 (as reported in Column D); between 5% and 15% of respondents report that they do recall attending an aspiration screening.Footnote15 While it is impossible to fully rule out that these respondents did attend a screening, no such contamination was reported by program staff, and the geographic dispersion of the sample as well as the absence of public information around the video screenings renders their attendance unlikely. Another possible hypothesis is that respondents may be mis-identifying another intervention.

To examine intervention effects, reports the results of estimating EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) for the dependent variables capturing aspirations in the pooled sample (both men and women), and reports the same results for the extremely poor sample only.Footnote16 In both samples, there is very little evidence of any significant effect of the aspirations intervention on the aspirations variables, and this pattern is consistent using both the unadjusted p-values and the adjusted q-values.Footnote17 There is also no evidence of significant effects of the broader set of L* interventions on aspirations. The point estimates are relatively small in magnitude: for education, the largest effect observed in the full sample () is an increase in the probability that parents report secondary school education as an aspiration for their child, and this effect is still only 2.2 percentage points, relative to a mean probability in the control arm of 46%. (The confidence interval is somewhat wider, however, suggesting that a larger effect cannot be ruled out.)

Table 3. Intervention effects on stated aspirations (pooled sample).

Table 4. Intervention effects on stated aspirations (extremely poor sample).

Table A1 in the Appendix reports the fully saturated specification with a full set of binary variables for each treatment arm, and again shows a consistent pattern of null effects. Table A2 in the Appendix reports the results of estimating the parsimonious specification, EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) , including additional interaction terms for gender, and thus assessing whether the effects are different for men and women. In fact, the effects of L* on aspirations seem to be substantially different for men and women,Footnote18 but the effects of the video intervention itself are similar. Though there is some evidence that men shift their aspirations for their eldest child from no education to university and these effects are muted for women, the estimated interaction effects are generally insignificant when employing the adjusted q-values.Footnote19 We also report in Tables A3 and A4 in the Appendix separate sets of results for parents who report their eldest child is a boy vis-à-vis parents who report their eldest child is a girl. There is no evidence of differential effects with respect to the gender of the eldest child.Footnote20

reports experimental effects for educational outcomes: more specifically, enrolment and attendance for children aged 6—13 in the sample households, a sample of 2,537 children. (Enrolment data was only collected for these children, corresponding to the target ages for primary school in Ethiopia; given that the household sample was targeted at households with infants at baseline, the number of older children in the sample is not large.) The results suggest there is generally no evidence of any positive effect of the aspirations intervention on any measures of school enrolment or attendance.

Table 5. Intervention effects on educational outcomes.

then reports a series of variables linked to household savings. While there is evidence of substantial effects of the main L* interventions on savings, especially savings reported by women, there is no evidence of differential effects driven by the cross-randomised aspirations treatment. We also report in the Appendix (Tables A5 and A6) analyses of other economic outcomes (household investment in livestock, and household engagement in wage labour). Again, the results are generally null.

Table 6. Intervention effects on savings.

4.1. Discussion and conclusion

To sum up, evidence from this context suggests that the hypothesis of a null effect of a relatively light-touch aspirations intervention implemented in a sample of poor adults in rural Amhara and Oromia province cannot be rejected. There is no evidence that the intervention succeeded in shifting respondents’ stated aspirations around their income or their children’s educational level; nor is there evidence of any shifts in economic behaviours. In contrast to recent evidence from Kenya, we also see no evidence that a large cash or in-kind transfer had any direct positive effect on aspirations. However, the transfers in this trial were valued at only around $400 in PPP terms, in contrast to a transfer of over $2000 in the Kenya trial. These findings are also inconsistent with previous evidence from Ethiopia analysing the same intervention in a broad sample of rural households that was not limited to PSNP beneficiaries (Bernard et al. Citation2014).

In interpreting the absence of any intervention effects, we can identify several possible relevant hypotheses. First, the base level of stated aspirations for education is extremely high. In the pooled sample of both men and women, 45% of respondents state that they aspire for their children to complete secondary school; 50% of respondents state their aspiration is for a tertiary education (bachelors’ degree). This high level of initial aspirations is also consistent with reported patterns in other Ethiopian data (Bernard et al. Citation2014; Dercon and Singh Citation2013). Enrolment rates for the children observed in the survey (aged 6—13) are similarly high at 92%. This arguably leaves relatively limited scope for an intervention to further enhance educational goals or shift enrolment patterns. That being said, the coefficients of interest here are generally not suggestive of positive effects that are imprecisely estimated due to low power, but rather indicative of effects that are very close to zero; and should there be true intervention effects, there could be scope for shifts in other economic decisions made by respondents (for example, savings or other forward-looking household investments).

Second, the entire sample in this analysis, including the control group, is receiving cash and food transfers through the Productive Safety Nets Program; and thus we cannot rule out the hypothesis that these transfers themselves had an effect on aspirations. That being said, PSNP transfers are primarily targeted as consumption support transfers for households at or below subsistence, and there is no evidence that the larger ($200 or roughly $400 in purchasing power parity terms) transfers evaluated as part of the experimental design had any meaningful effect on aspirations.

In light of these results, further work may seek to explore the contexts in which interventions can effectively target aspirations for adults (as opposed to youth, where the body of evidence is substantially larger) and understand how the process of aspiration formation can vary. While some initial results have been promising, effects may be highly context-specific.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw data from the underlying trial is currently available in IFPRI’s data repository. Code and data files for the specific analysis reported here will be submitted to the Journal of Development Effectiveness for posting upon article acceptance.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2024.2334214.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jessica Leight

Jessica Leight is a Research Fellow in the Poverty, Gender and Inclusion unit at IFPRI.

Daniel O. Gilligan

Daniel Gilligan is unit director in the Poverty, Gender and Inclusion unit at IFPRI.

Michael Mulford

Michael Mulford is the Chief of Party at SPIR II at World Vision.

Alemayehu Seyoum Taffesse

Alemayehu Seyoum Taffesse is Senior Research Fellow/Program Leader- Ethiopia at IFPRI.

Heleene Tambet

Heleene Tambet is a senior Research Analyst in the Poverty, Gender and Inclusion unit at IFPRI.

Notes

1. A kebele is a subdistrict in Ethiopia. A woreda is a district.

2. SPIR has been implemented by World Vision in partnership with the Organization for Rehabilitation and Development in Amhara (ORDA) and CARE between 2016 and 2021.

3. N* includes targeted nutritional intervention for acutely malnourished children, interpersonal therapy in groups for women identified as depressed, and behavioural change communication delivered by World Vision community health facilitators.

4. The original experimental design also called for L* programming to include social analysis and action, a community-led social change strategy that addresses constraints on women’s role in intrahousehold decision-making, mobility, and choice of livelihood activities, as well as restrictions on access to markets that derive from cultural and social norms. In practice, implementation of the SAA interventions was limited.

5. Due to differences in the timing of program rollout in the two evaluation regions, randomisation was conducted separately for Amhara and Oromia. More details are provided in the baseline report.

6. Three of the profiled individuals are from Oromia, and one is from Amhara. The individuals were identified from descriptions of individuals’ life stories submitted by non-governmental organisation staff and development agents.

7. Two kebeles do not have attendance information available: Akim Tserewa (Sekota woreda, Amhara) and Shelo Belala (Siraro woreda, Oromia). Note that attendance information, when collected, is a list of men and women who attended each screening, but these names are not listed with household indicators as employed in the survey itself. In addition, matching names between attendance records and the survey sample can be somewhat imperfect, and for this reason the estimates of attendance are not fully precise.

8. At the point of sampling, this area was constituted by only 13 woredas, but following the baseline survey, two new woredas were created to generate 15 in total. We retain the original woreda strata when controlling for study design in the treatment effect models during analysis.

9. More precisely, these two inclusion criteria yielded 196 kebeles; two additional kebeles were dropped when no PSNP clients were identified, one kebele was dropped for security reasons, and one kebele was excluded in error from baseline surveys.

10. This corresponds to 95.4% of the target sample identified prior to the baseline survey. The sample includes 1,920 households from Amhara and 1,394 from Oromia. Interviews with a primary male respondent were completed in 2,756 sample households; of the 558 households without a primary male respondent interview, 522 (93.5%) were female headed households and generally would not have had a responsible male (such as a spouse to the female head) eligible to serve as primary male respondent. In only 35 households was a primary male respondent identified but not available for interview.

11. Baseline data is not available for school enrolment and attendance variables for children.

12. Multiple hypothesis-adjusted q-values are calculated in Stata using the command qqvalue and employing the Simes method, thus adjusting the p-values as a function of the number of hypotheses tested.

13. The coefficient on T3 is omitted in this more parsimonious model.

14. The final column of the table reports a p-value corresponding to the joint test β1 = β2 = β3 = β4 = β5 = 0.

15. Reported contamination in the control arm is minimal.

16. As previously noted, the full midline sample includes 3,220 households; however, the sample for the individual-level aspirations variables is lower than 6440 (corresponding to two respondents per household), because in some households the primary male or female was either completely absent at midline (e.g. deceased or migrated) or not available for the survey (temporarily absent or declined to provide consent). The sample included in the aspirations analysis thus includes 2,911 women and 2,347 men; attrition was more common for the male respondent. There are 2,224 households in which both spouses are represented in this analysis, 687 in which only the female spouse is represented, and 123 in which only the male spouse is represented. There are also 186 households surveyed in the midline survey in which neither spouse responded to the aspirations module, and thus they are not represented in this analysis.

17. This adjustment is estimated for all specifications and coefficients within the pooled sample.

18. Fully assessing the reason for this pattern is beyond the scope of this paper, but it may reflect the fact that the direct economic effects of L* interventions differ for men and women.

19. Again, adjustments for multiple hypothesis testing are conducted across all specifications and coefficients within a table (i.e. for the male and female samples, respectively), but are not conducted across tables.

20. We also explore examining the effects on aspirations for the non-random subsample of respondents who do report recall of the video session. There is no robust evidence of any experimental effects here.

References

- Acevedo, P., G. Cruces, P. Gertler, and S. Martinez. 2020. “How Vocational Education Made Women Better off but Left Men Behind.” Labour Economics 65 (March 2019): 101824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101824.

- Alderman, H., F. Bachewe, D. O. Gilligan, M. Hidrobo, N. Ledlie, G. V. Ramani, and A. S. Tafesse. 2019. “Impact Evaluation of the Strengthen PSNP4 Institutions and Resilience (SPIR) Development Food Security Activity (DFSA): Baseline Report.” https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/136720/filename/136934.pdf.

- Ashraf, N., N. Bau, C. Low, and K. McGinn. 2020. “Negotiating a Better Future: How Interpersonal Skills Facilitate Intergenerational Investment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 1095–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz039.

- Baranov, V., J. Haushofer, and C. Jang. 2020. “Can Positive Psychology Improve Psychological Well-Being and Economic Decision-Making? Experimental Evidence from Kenya.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 68 (4): 1345–1376. https://doi.org/10.1086/702860.

- Berhane, G., D. O. Gilligan, J. Hoddinott, N. Kumar, and A. Seyoum Taffesse. 2014. “Can Social Protection Work in Africa? The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 63 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/677753.

- Berhane, G., K. Hirvonen, J. Hoddinott, N. Kumar, A. S. Taffesse, Y. Yohannes, and A. Strickland , et al. 2013. “The Implementation of the Productive Safety Nets Programme and the Household Asset Building Programme in the Ethiopian Highlands, 2012: Program Performance Report.” Unpublished, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

- Bernard, T., S. Dercon, K. Orkin, and A. Seyoum Taffesse. 2019. “Parental Aspirations for Children’s Education: Is There a ‘Girl Effect’? Experimental Evidence from Rural Ethiopia.” AEA Papers and Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191072.

- Bernard, T., S. Dercon, K. Orkin, and A. Taffesse. 2014. “The Future in Mind: Aspirations and Forward-Looking Behavior in Rural Ethiopia.” 10224. CEPR Discussion Paper.

- Bhanot, S. P., B. Crost, J. Leight, E. Mvukiyeke, and B. Yedgenov. 2020. “Can Community Service Grants Foster Social and Economic Integration for Youth? A Randomized Trial in Kazakhstan.” Journal of Development Economics 153:102718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102718.

- Blattman, C., J. C. Jamison, and M. Sheridan. 2017. “Reducing Crime and Violence: Experimental Evidence from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Liberia.” The American Economic Review 107 (4): 1165–1206. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150503.

- Blattman, C., and L. Ralston. 2015. “Generating Employment in Poor and Fragile States: Evidence from Labor Market and Entrepreneurship Programs.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2622220.

- Dalton, P. S., S. Ghosal, and A. Mani. 2016. “Poverty and Aspirations Failure.” Economic Journal 126 (590): 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12210.

- Dercon, S., and A. Singh. 2013. “From Nutrition to Aspirations and Self-Efficacy: Gender Bias Over Time Among Children in Four Countries.” World Development 45:31–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.001.

- Edmonds, E., B. Feigenberg, and J. Leight. 2021. “Advancing the Agency of Adolescent Girls.” Review of Economics and Statistics 1–46.

- Ganimian, A. 2020. “Growth-Mindset Interventions at Scale: Experimental Evidence from Argentina.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720938041.

- Ganimian, A., F. Barrera-Osorio, M. Loreto Biehl, and M. Ángela Cortelezzi. 2020. “Hard Cash and Soft Skills: Experimental Evidence on Combining Scholarships and Mentoring in Argentina.” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 13 (2): 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2019.1711271.

- Genicot, G., and D. Ray. 2017. “Aspirations and Inequality.” Econometrica 85 (2): 489–519. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta13865.

- Ghosal, S., S. Jana, A. Mani, S. Mitra, and S. Roy. 2022. “‘Sex Workers, Stigma, and Self-Image: Evidence from Kolkata Brothels’.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 104 (3): 431–448.

- Gilligan, D. O., J. Hoddinott, and A. Seyoum Taffesse. 2009. “The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme and Its Linkages.” The Journal of Development Studies 45 (10): 1684–1706. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380902935907.

- Groh, M., N. Krishnan, D. McKenzie, and T. Vishwanath. 2016. “The Impact of Soft Skills Training on Female Youth Employment: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Jordan.” IZA Journal of Labor & Development 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40175-016-0055-9.

- Hoddinott, J., and T. J. Mekasha. 2020. “Social Protection, Household Size, and Its Determinants: Evidence from Ethiopia.” The Journal of Development Studies 56 (10): 1818–1837. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1736283.

- Lubega, P., F. Nakakawa, G. Narciso, C. Newman, A. N. Kaaya, C. Kityo, and G. A. Tumuhimbise. 2021. “Body and Mind: Experimental Evidence from Women Living with HIV.” Journal of Development Economics 150 (December 2020): 102613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102613.

- Orkin, K., R. Garlick, M. Mahmud, R. Sedlmayr, J. Haushofer, and S. Dercon. 2023. “Aspiring to a Better Future: Can a Simple Psychological Intervention Reduce Poverty?”

- Outes-León, I., S. Alan, and R. Vakis. 2020. “The Power of Believing You Can Get Smarter the Impact of a Growth-Mindset Intervention on Academic Achievement in Peru.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9141.

- Serra, D., C. Porter, E. Kipkech Kipchumba, and M. Sulaiman. 2021. “Influencing Youths’ Aspirations and Gender Attitudes Through Role Models: Evidence from Somali Schools.” Texas A&M University Working Paper 20210224-002.

- Simes, R. J. 1986. “An Improved Bonferroni Procedure for Multiple Tests of Significance.” Biometrika 73 (3): 751–754. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/73.3.751.

- Wydick, B., P. Glewwe, and L. Rutledge. 2013. “Does International Child Sponsorship Work? A Six-Country Study of Impacts on Adult Life Outcomes.” Journal of Political Economy 121 (2): 393–436. https://doi.org/10.1086/670138.