ABSTRACT

Background: Negative reactions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following childbirth have been increasingly reported in mothers, particularly following objectively and subjectively difficult childbirth experiences. A small body of research has examined fathers’ reactions to childbirth, with mixed results.

Objective: The study aimed to further these studies, investigating whether objective and subjective aspects of fathers’ participation in childbirth were related to levels of PTSD and fear of childbirth symptoms, in the first year following childbirth.

Method: In total, 224 fathers whose partners had given birth within the previous 12 months answered online questionnaires that examined participation in childbirth, subjective appraisals, levels of fear of childbirth, and PTSD symptoms. Data were analysed using structural equation modelling, examining both direct and indirect effects.

Results: Approximately 6% of fathers reported symptoms consistent with probable PTSD. Negative cognitions mediated the path between an emergency caesarean and PTSD. Fear of childbirth was related to emergency caesareans and lack of information from the medical team.

Conclusions: Future studies should examine the level of fathers’ participation, their subjective appraisal of childbirth, and fear of childbirth, when assessing fathers’ reactions to childbirth.

HIGHLIGHTS

Fathers may report fear of childbirth, not just PTSD, following a traumatic childbirth.

Negative appraisal mediates the relationship between an emergency caesarean and PTSD.

Fear of childbirth is related to lower levels of information sharing by staff.

Antecedentes: Se han informado cada vez más reacciones negativas tales como el TEPT después del parto en las madres, particularmente después de experiencias del parto objetiva y subjetivamente difíciles. Un pequeño conjunto de investigaciones ha examinado las reacciones de los padres ante el parto, con resultados mixtos.

Objetivo: Este estudio tuvo como objetivo ampliar estos estudios, investigando si los aspectos subjetivos y objetivos de la participación de los padres en el parto se relacionaban a los niveles de TEPT y al miedo a los síntomas del parto, en el primer año después del parto.

Método: 224 padres cuyas parejas habían dado a luz dentro de los 12 meses previos, contestaron cuestionarios en línea, que examinaba la participación en el parto, las valoraciones subjetivas, los niveles de miedo al parto y síntomas de TEPT. Los datos se analizaron utilizando el modelo de ecuación estructural que examina tanto los efectos directos como indirectos.

Resultados: Aproximadamente 6% de los padres reportaron síntomas compatibles con un probable TEPT. Las cogniciones negativas mediaron la vía entre la cesárea de urgencia y TEPT. El miedo al parto se relacionó con la cesárea de urgencia y la falta de información del equipo médico.

Conclusiones: Los estudios futuros deberían examinar los niveles de participación de los padres, sus valoraciones subjetivas del parto, así como también el miedo al parto cuando se evalúan las reacciones de los padres al parto.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

The birth of a child is typically a joyous and significant event for parents. However, a growing body of literature highlights potential negative aspects of this experience. Childbirth that involves risk to the mother and/or baby, such as physical medical emergencies, health issues with the baby, and unexpected complications, can be considered potentially traumatic events (Pop-Jordanova, Citation2022). Studies have shown that around 4% of mothers report probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic birth, with a smaller percentage showing chronic PTSD (Yildiz et al., Citation2017).

In contrast with previous generations, more than 90% of fathers are now present during labour (Redshaw & Henderson, Citation2013). The presence of the father has a demonstrated positive effect on parental relationships, father–infant relationships (Bowen & Miller, Citation1980), and the general well-being of the mother (Gungor & Beji, Citation2007; Somers-Smith, Citation1999). Studies have reported that men who felt less fulfilment and delight with the labour process reported more symptoms of depression (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2000).

Regarding PTSD, a few studies have examined PTSD among fathers following childbirth, and the findings are inconsistent. One study reported that 19% of fathers reported psychological distress at 6 months after childbirth, yet none reported symptoms consistent with PTSD (Skari et al., 2002). Other studies reported levels of probable PTSD, from 0.7% at 8 weeks (Kress et al., Citation2021) and 5% at 9 weeks postpartum (Ayers et al., Citation2007) to 7% at 3 months postpartum (Schobinger et al., Citation2020). Predictors for higher levels of PTSD among fathers after childbirth are similar to those for mothers: complications during the birth (Ayers et al., Citation2007; Kress et al., Citation2021), high levels of emotion during birth (Ayers et al., Citation2007), anxiety sensitivity (Zerach & Magal, Citation2016), acute PTSD symptoms (Schobinger et al., Citation2020), and partner’s early PTSD symptoms (Iles et al., Citation2011). Only one study to date, using a single-item scale, has examined fathers’ subjective experience of the birth, and reported negative appraisal to be related to later PTSD. (Kress et al., Citation2021). This study showed that one predictor among mothers, emergency caesarean delivery, was not related to PTSD symptoms in fathers, but that high job burden (‘how heavily burdened they were by their job’) during pregnancy was predictive of PTSD.

Fear of childbirth has been studied extensively in mothers, and studies show that it is related to levels of PTSD Grundström et al. (Citation2022) and predicts postpartum psychopathology (Grekin et al., Citation2021). Only two studies have looked at fear of childbirth in fathers. In one study, 13.6% of the participants showed a fear of childbirth, which was correlated with being a first-time parent (Hildingsson et al., Citation2014). In addition, high levels of fear were associated with a negative perception of pregnancy, approaching labour, and a preference for caesarean section (Hildingsson et al., Citation2014). One qualitative study of men with high levels of fear of childbirth concluded that fathers find this hard to discuss out of consideration for their partner, and attend childbirth despite their fear (Eriksson et al., Citation2007).

Prior studies suggest that the wide range of negative emotional responses during and after birth may be related to appraisal of the event, such as perceptions of self-functioning and appraisal of the degree of support from medical staff. For example, fathers who felt unable to support their partner during labour experienced a higher level of stress than those who felt that they successfully fulfilled supportive roles (Johnson, Citation2002). Lack of support from the medical staff affected the fathers’ emotional state, leading to increased feelings of alienation and despair during childbirth (Elmir & Schmied, Citation2016).

The present study sought to extend these findings by examining PTSD symptoms and fear of childbirth in a cohort of fathers from a community sample in the first year after childbirth. Moreover, the study aimed to investigate how objective characteristics (labour type) and subjective appraisals of labour (negative perceptions of the self and the world, fathers’ reported level of participation, and extent of information shared by the medical staff) were related to the severity of reported symptoms.

We hypothesized that:

The severity of post-traumatic symptoms and the level of fear of birth would be greater among men who attended an emergency caesarean section than in men who attended a planned caesarean section or were present during regular labour.

There would be a correlation between subjective characteristics of the labour event, such as negative cognitions, father’s involvement, and extent of information shared by the medical staff, and the severity of post-traumatic symptoms and level of fear of childbirth.

2. Method

2.1. Study participants

We included men whose partner had given birth between 2 months and 1 year prior to participating in the study, and who could answer questionnaires in Hebrew.

2.2. Questionnaire methods

It was assumed that the anonymity of this method might be preferred by some participants on account of the sensitivity of the subject. The questionnaire introduction noted that participation was voluntary and could be suspended at any stage. Possible emotional triggers were mentioned, and a list of support providers was given.

2.3. Procedure

This was a cross-sectional study using a convenience sample, combined with purposive and snowball sampling. The study recruits were solicited in several ways using online social media, recruiting participants from websites most likely to be used by relevant participants, e.g. regarding parenting, fathers, and childbirth. These recruited participants were asked to recruit further participants (snowball sampling). The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee at the Bar Ilan University where the authors are based, before data collection commenced using internet-based questionnaires.

2.4. Measures

Demographic and obstetric data regarding gender, age, country of origin, education, marital status, religious observation, parity, and mode of childbirth were collected. Information was also collected on the last delivery, including pain management, preparation for birth, and level of satisfaction with treatment during the birth.

Experience of childbirth was measured using the Wijma Delivery Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ, version B) ( Wijma et al., Citation1998). This scale was originally conceptualized to capture fear regarding childbirth; more recent studies have delineated four factors: Negative Emotions (NE), Lack of Positive Emotions (LPE), Social Isolation (SI), and Moment of Birth (MB). The current study used the original format, consisting of 33 items measuring the participants’ feelings and cognitions surrounding the childbirth experience (e.g. ‘How did you feel during the birth?’). Items were scored on a six-point Likert scale, with high scores indicating higher levels of fear in childbirth during the woman’s last delivery. Total scores for this questionnaire ranged from 0 to 165. All four subscales were calculated. Previous research has indicated a high level of reliability, of 0.90 or higher (Wijma et al., Citation1998). Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.89.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms were measured using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al., Citation2015). This 20-item self-report questionnaire assessed symptoms of PTSD experienced in the past month (e.g. ‘How bothered were you by intrusive, recurrent and unwanted memories of the traumatic experience?’). Scoring was on a scale of 0–4 for each symptom. A total symptom severity score (0–80) was obtained by adding the scores of the 20 items. Probable PTSD was calculated using a cut-off of 33 (Bovin et al., Citation2016), although the length of time these symptoms had been experienced was not assessed. Cronbach’s alpha in the study was 0.95. Participants were asked to which traumatic event they were relating these symptoms.

Post-traumatic cognitions were measured using the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI) (Beck et al., Citation2004). This 33-item self-report questionnaire assesses cognitions related to PTSD on three subscales: Self-blame (e.g. the event happened because of the way I acted), Negative Cognitions of Self-worth (e.g. I can’t trust that I will do the right thing), and Negative Cognitions of the World (e.g. You can never know who will harm you), on a seven-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha in the study was 0.93.

Fathers’ participation in the birth was measured using the Father Interview Form (Gungor & Beji, Citation2007). This consists of items that measure the fathers’ motivation for attending the birth (e.g. to support their partner), the amount of time they were present throughout the birth, and the amount of control they felt they had over events. A composite score of behaviours (Father participation) was calculated, including behaviours that they carried out to support their partner physically (e.g. massage) and psychologically (e.g. helped her feel she was not alone), and communication (e.g. listened effectively to their partner), with a total score of up to 19 potential behaviours.

Information sharing by the medical team was measured by three dichotomous items: Did you feel that the medical team shared information regarding their decisions with your partner? Did the medical team initiate sharing information with you about your partner/baby? If you asked the medical team for information regarding your partner, did they help you? These questions have a total score of up to 3.

2.5. Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS software version 26 and AMOS software version 25.

First, descriptive statistics were presented using means and standard deviations; this was followed by univariate correlations, which were assessed using Pearson correlations, chi-squared tests, or analysis of variance procedures. To examine the mediation model, structural equation modelling (SEM) was conducted, which assessed the correlations between the variables. In addition, quality of fit measures were produced: the goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI) (all with goodness of fit values > 0.9), as well as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which is expected to have a value of 0.08 or less (Arbuckle, Citation2013). The SEM approach examined both direct and indirect paths, to test the hypotheses regarding mediation.

Significance was considered for a p-value lower than 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

and present the demographic and birth characteristics of the participants. In total, 224 men were recruited into the study; 67% were aged 26–35 years and 86% were married. The majority of participants had an academic background, and reported higher than average income (compared to the average national income at the time of the study). Most pregnancies lasted between 37 and 40 weeks, over 80% of births took place in hospital, and over 90% were vaginal and/or assisted births. Most fathers attended the birth to support their partner, and were present 100% of the time. Fathers’ participation was measured on a total of 19 potential behaviours, and averaged 11.5 out of 17 behaviours performed.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Table 2. Birth characteristics.

Examination of the relationship between probable PTSD and birth type showed that a greater proportion of fathers attending an elective caesarean (33.3%) reported probable PTSD in comparison with those attending a regular birth (7.4%) or an emergency caesarean (0%) (χ2 = 6.1, p < .05).

Similarly, fathers whose partners underwent an elective caesarean reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms (M = 23.3, SD = 6.4), compared with those attending a regular birth (M = 10.1, SD = 12.9) or an emergency caesarean (M = 6.4, SD = 7.7) [F(2,176) = 3.3, p < .05].

However, fathers whose partners underwent an emergency caesarean reported a significantly higher fear of childbirth (M = 70.7, SD = 26.1), compared with those attending a regular (M = 45.7, SD = 21.3) or an elective caesarean (M = 48.7, SD = 16.1) [F(2,218) = 10.1, p < .001].

presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations between study variables.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables.

The results show that emergency caesareans were correlated with lower father participation, less information sharing by the medical team, and a higher fear of childbirth. In addition, father participation was positively correlated with information sharing by the medical team and higher PTCI scores. More information sharing by the medical team was negatively correlated with fear of childbirth. However, higher PTCI scores were positively correlated with fear of childbirth.

3.2. Testing the study model: SEM analysis

To examine the study model and hypotheses, SEM analysis was conducted. The model was controlled for fear and perception of pregnancy. The results demonstrate acceptable goodness of fit indices of the model [χ2(5) = 6.14; p = .292; GFI = .99; NNFI = .99; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .039].

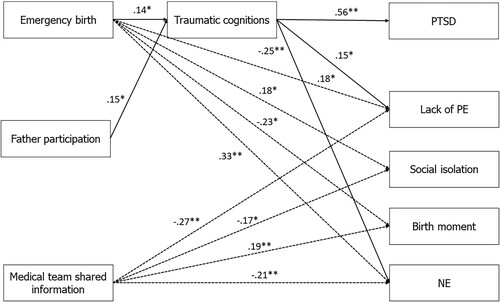

The results of hypothesis testing according to the main model are presented as follows.

H1: Higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth will be found among fathers who were present at an emergency birth. No significant association was found between post-traumatic stress symptoms and type of birth (β = −.07, p = .30). H1 was not supported.

H2: Higher levels of fear of childbirth will be found among fathers who were present at an emergency caesarean. The results showed that emergency caesarean is correlated with LPE (β = .18, p < .05), higher SI (β = .18, p < .05), lower MB emotions (β = −.23, p < .05), and higher NE (β = .33, p < .01). H2 was supported.

H3: PTSD cognitions will be positively correlated with PTSD symptoms. A positive association was found between these variables in the model (β = .51, p < .01). H3 was supported.

H4: PTSD symptoms will be negatively correlated with higher levels of fathers’ participation. No significant association was found between these variables (β = .01, p = .85). H4 was not supported.

H5: PTSD symptoms will be negatively correlated with information sharing by the medical team. No significant association was found between these variables (β = .02, p = .88). H5 was not supported.

H6: Fear of childbirth will be negatively correlated with information sharing by the medical team. The results showed that sharing information by the medical team was correlated with LPE (β = −.27, p < .01), lower SI (β = −.17, p < .05), higher MB emotions (β = .19, p < .01), and lower NE (β = −.21, p < .01). H6 was supported.

Examination of indirect effects showed that post-traumatic cognitions mediate the effect of emergency caesarean on PTSD (β = .08, p < .05). Specifically, fathers who were present at an emergency caesarean tended to experience more post-traumatic cognitions, which, in turn, led to more PTSD symptoms ().

Figure 1. Relationships between emergency birth, father’s participation, and information sharing by the medical team, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and fear of childbirth, mediated by traumatic cognitions. PE = positive emotion; NE = negative emotion. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01. Only significant paths appear in the figure.

In addition, post-traumatic cognitions mediated the effect of fathers’ participation on PTSD (β = .07, p < .05). Specifically, fathers who participated more in childbirth tended to experience more post-traumatic cognitions, which, in turn, led to more PTSD symptoms.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to characterize the relationships between fathers’ participation in childbirth, the medical team’s sharing of information, and cognitive appraisals, and fear of childbirth and self-reported PTSD symptoms. As hypothesized, most fathers in this study reported being present for the whole of the labour, and this is consistent with previous reports over the past decade. Approximately 6% of fathers reported a level of PTSD symptoms consistent with a clinical diagnosis.

As expected, and consistent with previous studies in other populations, negative appraisal played a significant role in PTSD levels: fathers who were present at an emergency birth reported more traumatic cognitions, which, in turn, were significantly related to more PTSD symptoms. Fathers who reported more active participation in the childbirth also reported more traumatic cognitions, which, in turn, led to more PTSD symptoms. This latter finding is more surprising, since active coping skills are usually associated with lower PTSD symptom levels (Peters et al., Citation2021). However, since there is little literature regarding fathers’ participation during childbirth, this needs to be examined more carefully. It may reflect the fact that greater participation is, by definition, related to greater exposure to potentially traumatic aspects of childbirth. It may also be that their partner’s reaction to their participation is salient; for instance, if the father reports that he brought ice and offered massage, but his partner rejected these as being helpful, this may lead to negative cognitions regarding the participation, and therefore raise the chances of reporting higher levels of PTSD.

As with the literature on mothers after a traumatic birth, it seems that different factors are related to reporting higher levels of fear of childbirth, e.g. as compared to PTSD. In this study, fear of childbirth was found to be related to an emergency caesarean. This is perhaps again related to exposure: whereas fathers are likely to be present at an elective caesarean (thus presenting with more exposure to potential trauma), emergency caesareans are characterized by the mother being whisked away and the father not being present, possibly increasing the feelings of lack of control and danger. This is consistent with a previous study showing that fathers who are unable to be supportive of their partners report higher stress (Johnson, Citation2002).

Fear of childbirth was also impacted by information sharing by the medical team, which was associated with lower social isolation, higher ‘moment of birth’ emotions, and lower negative affect. This finding is important and could be further explored in future research.

4.1. Limitations and recommendations for further research

This study was limited in terms of sample, since this was a self-selected group of men who answered messages on social media, and therefore it is not clear how well they represent a larger, more general population, or a clinical sample. Moreover, the sample size was small, which limited the power and the SEM results. Future studies should attempt to recruit a larger sample of all fathers within a specific population.

Similarly, the use of self-report questionnaires, as opposed to clinical interviews, limits the conclusions that can be drawn in relation to clinically relevant symptom levels. This is particularly important in relation to PTSD. In this study, although we asked participants to link their symptoms with a specific event, most did not answer this question. We also did not assess the length of time for which PTSD symptoms were present. As such, these results may reflect acute PTSD rather than probable chronic PTSD, and may also reflect PTSD related to a different traumatic event. Future studies that are prospective, beginning during the mother’s pregnancy, and include a clinical interview to assess PTSD (e.g. the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale), would be the best way to overcome these limitations.

There is a growing understanding that an individual’s reaction to a potentially traumatic event is embedded in their intimate personal relationships, such that negative reactions to a traumatic event negatively affect these relationships, and that a lack of social support and dissatisfaction in interpersonal relationships are risk factors for developing PTSD (Fredman et al., Citation2014). Models now look to examine both partners’ reactions, both to the event and to each other, when understanding PTSD. This is in line with previous studies that have examined PTSD in fathers along with their partners (Kress et al., Citation2021). Future studies would benefit from using this model, reporting both partners’ reaction in a prospective design, and including variables found to be important in this study, such as negative appraisals, level of participation by the fathers, and fear of childbirth.

5. Conclusions

Childbirth has the potential to exacerbate existing psychological symptoms, and increase the likelihood of new symptoms, in both parents. Although only a small number of studies on childbirth-related psychopathology have examined the reactions of fathers, their results have important implications for families. This study showed that in the year following childbirth, approximately 6% of fathers report symptoms of probable PTSD, and also report fear of childbirth after attending labour; the severity of these may be related to the type of labour that the father attended. These findings may have important implications at the practical level, with one option for change being the formulation of a clear, formal policy regarding the role of the father in the delivery room and the attitude of the staff to his presence, especially during emergency and elective caesarean procedures.

The findings of this study highlight the importance of sharing information about the condition of the mother and the foetus by the medical staff. Many men feel helpless and confused about their role during labour (Hanson et al., Citation2009), which may later affect their mental state and their relationship with their partner and the newborn. Obtaining reliable information from the medical staff about the condition of their loved ones may reduce this level of fear.

These results suggest that in the same way as mothers are routinely assessed for symptoms postpartum, it is also important to assess fathers’ symptoms. Studies have demonstrated the impact of the parents’ mental state on their relationship, as well as on parent–baby bonding and baby development, and early detection is important. In addition, interventions that relieve or even prevent mothers’ PTSD related to childbirth (Taylor Miller et al., Citation2021) may also be relevant for fathers, and this aspect should be explored.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, SAF. The data are not publicly available owing to ethical committee restrictions.

References

- Arbuckle. (2013). IBM® SPSS® AmosTM 22 user’s guide.

- Ayers, S., Wright, D. B., & Wells, N. (2007). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in couples after birth: Association with the couple’s relationship and parent–baby bond. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 25(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830601117175

- Beck, J. G., Coffey, S. F., Palyo, S. A., Gudmundsdottir, B., Miller, L. M., & Colder, C. R. (2004). Psychometric properties of the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): A replication with motor vehicle accident survivors. Psychological Assessment, 16(3), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.289

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

- Bowen, S. M., & Miller, B. C. (1980). Paternal attachment behavior as related to presence at delivery and preparenthood classes: A pilot study. Nursing Research, 29(5), 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198009000-00010

- Elmir, R., & Schmied, V. (2016). A meta-ethnographic synthesis of fathers׳ experiences of complicated births that are potentially traumatic. Midwifery, 32, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.09.008

- Eriksson, C., Salander, P., & Hamberg, K. (2007). Men’s experiences of intense fear related to childbirth investigated in a Swedish qualitative study. The Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 4(4), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmhg.2007.07.045

- Fredman, S. J., Vorstenbosch, V., Wagner, A. C., Macdonald, A., & Monson, C. M. (2014). Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Initial testing of the significant others’ response to trauma scale (SORTS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(4), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.001

- Greenhalgh, R., Slade, P., & Spiby, H. (2000). Fathers’ coping style, antenatal preparation, and experiences of labor and the postpartum. Birth, 27(3), 177–184. PMID: 11251499. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00177.x

- Grekin, R., O’Hara, M. W., & Brock, R. L. (2021). A model of risk for perinatal posttraumatic stress symptoms. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 24(2), 269–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01068-2

- Grundström, H., Malmquist, A., Ivarsson, A., Torbjörnsson, E., Walz, M., & Nieminen, K. (2022). Fear of childbirth postpartum and its correlation with post-traumatic stress symptoms and quality of life among women with birth complications – A cross-sectional study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01219-7

- Gungor, I., & Beji, N. K. (2007). Effects of fathers’ attendance to labor and delivery on the experience of childbirth in Turkey. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 29(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945906292538

- Hanson, S., Hunter, L. P., Bormann, J. R., & Sobo, E. J. (2009). Paternal fears of childbirth: A literature review. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 18(4), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1624/105812409X474672

- Hildingsson, I., Johansson, M., Fenwick, J., Haines, H., & Rubertsson, C. (2014). Childbirth fear in expectant fathers: Findings from a regional Swedish cohort study. Midwifery, 30(2), 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.01.001

- Iles, J., Slade, P., & Spiby, H. (2011). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and postpartum depression in couples after childbirth: The role of partner support and attachment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.12.006

- Johnson, M. P. (2002). The implications of unfulfilled expectations and perceived pressure to attend the birth on men’s stress levels following birth attendance: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 23(3), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820209074670

- Kress, V., von Soest, T., Kopp, M., Wimberger, P., & Garthus-Niegel, S. (2021). Differential predictors of birth-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in mothers and fathers – A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.058

- Peters, J., Bellet, B. W., Jones, P. J., Wu, G. W. Y., Wang, L., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Posttraumatic stress or posttraumatic growth? Using network analysis to explore the relationships between coping styles and trauma outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102359

- Pop-Jordanova, N. (2022). Childbirth-related psychological trauma. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki, 43(1), 17–27.

- Redshaw, M., & Henderson, J. (2013). Fathers’ engagement in pregnancy and childbirth: Evidence from a national survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-70

- Schobinger, E., Stuijfzand, S., & Horsch, A. (2020). Acute and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in mothers and fathers following childbirth: A prospective cohort study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 109(10), 1154–1163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.00468.x

- Somers-Smith, M. J. (1999). A place for the partner? Expectations and experiences of support during childbirth. Midwifery., 152(2), 101–108. PMID: 10703413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-6138(99)90006-2

- Taylor Miller, P. G., Sinclair, M., Gillen, P., McCullough, J. E. M., Miller, P. W., Farrell, D. P., Slater, P. F., Shapiro, E., & Klaus, P. (2021). Early psychological interventions for prevention and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-partum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258170

- Wijma, K., Wijma, B., & Zar, M. (1998). Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 19(2), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829809048501

- Yildiz, P. D., Ayers, S., & Phillips, L. (2017). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208 (October 2016), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009

- Zerach, G., & Magal, O. (2016). Anxiety sensitivity among first-time fathers moderates the relationship between exposure to stress during birth and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 204(5), 381–387. PMID: 26894317. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000482