ABSTRACT

Introduction: Research has shown that combining different evidence-based PTSD treatments for patients with PTSD in an intensive inpatient format seems to be a promising approach to enhance efficiency and reduce generally high dropout rates.

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of an intensive six-day outpatient trauma-focused treatment for patients with PTSD.

Method: Data from 146 patients (89.7% female, mean age = 36.79, SD = 11.31) with PTSD due to multiple traumatization were included in the analyses. The treatment programme consisted of six days of treatment within two weeks, with two daily individual 90-minute trauma-focused sessions (prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), one hour of exercise, and one hour of psychoeducation. All participants experienced multiple traumas, and 85.6% reported one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders. PTSD symptoms and diagnoses were assessed with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), and self-reported symptoms were assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Results: A significant decline in PTSD symptoms (CAPS-5 and PCL-5) from pretreatment to one-month follow-up (Cohen's d = 1.13 and 1.59) was observed and retained at six-month follow-up (Cohen's d = 1.47 and 1.63). After one month, 52.4% of the patients no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD (CAPS-5). The Reliable Change Index (RCI) shows that 73.9% of patients showed improvement on the CAPS-5 and 77.61% on the PCL-5. Additionally, 21.77% (CAPS-5) and 20.0% (PCL-5) showed no change, while 4.84% (CAPS-5) and 2.96% (PCL-5) showed symptom worsening.

Discussion: The results show that an intensive outpatient trauma treatment programme, including two evidence-based trauma-focused treatments, exercise, and psychoeducation, is effective for patients suffering from PTSD as a result of multiple traumatization. Subsequent research should focus on more controlled studies comparing the treatment programme with other intensive trauma treatments and less frequent routine treatment.

HIGHLIGHTS

Intensive outpatient trauma treatment is effective in treating PTSD.

Six days of combining prolonged exposure, EMDR, exercise and psycho-education seems feasible and effective in treating PTSD.

73.9% of the patients show improvement on the CAPS-5 and 77.61% show improvement on the PCL-5, symptom worsening was there in 4,84, respectively 2.96%.

Introducción: Las investigaciones han mostrado que la combinación de diferentes tratamientos para TEPT basados en la evidencia para pacientes con TEPT en una modalidad hospitalaria intensiva parece ser un enfoque prometedor para aumentar la eficiencia y reducir las tasas de abandono generalmente altas.

Objetivo: Evaluar la efectividad de un tratamiento ambulatorio intensivo de seis días focalizado en trauma para pacientes con TEPT.

Método: Fueron incluidos en el análisis los datos de 146 pacientes (89.7% mujeres, edad media = 36.79, DE = 11.31) con TEPT debido a traumatización múltiple. El programa de tratamiento consistió en seis días de tratamiento durante dos semanas, con dos sesiones individuales diarias de 90 minutos focalizadas en trauma (exposición prolongada y desensibilización y reprocesamiento por movimientos oculares), una hora de ejercicio y una hora de psicoeducación. Todos los participantes experimentaron múltiples traumas y el 85.6% reportó uno o más trastornos psiquiátricos comórbidos. Los síntomas y diagnóstico de TEPT se evaluaron con la escala de TEPT administrada por el clínico según el DSM-5 (CAPS-5) y los síntomas autoinformados se evaluaron con la lista de verificación de TEPT según el DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Resultados: Se observó una disminución significativa en los síntomas de TEPT (CAPS-5 y PCL-5) desde el pretratamiento hasta el seguimiento al mes (d de Cohen = 1.13 y 1.59) y se mantuvo a los seis meses de seguimiento (d de Cohen = 1.47 y 1.63). Después del mes, el 52,4% de los pacientes ya no cumplían los criterios diagnósticos de TEPT (CAPS-5). El índice de Cambio Confiable (RCI por sus siglas en inglés) muestra que el 73,9% de los pacientes mostraron una mejoría en el CAPS-5 y el 77,61% en el PCL-5. Además, el 21,77% (CAPS-5) y el 20,0% (PCL-5) no mostraron cambios, mientras que el 4,84% (CAPS-5) y el 2,96% (PCL-5) mostraron un empeoramiento de los síntomas.

Discusión: Los resultados muestran que un programa de tratamiento ambulatorio intensivo para trauma, que incluye dos tratamientos focalizados en trauma basados en la evidencia, ejercicio y psicoeducación, es efectivo para pacientes que sufren de TEPT como resultado de una traumatización múltiple. La investigación posterior debería centrarse en estudios más controlados que comparen el programa de tratamiento con otros tratamientos intensivos para para trauma y tratamientos de rutina menos frecuentes.

1. Introduction

About 7% of people exposed to a traumatic event develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2017; Kessler et al., Citation2017; De Vries & Olff, Citation2009). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; APA, Citation2017), a diagnosis of PTSD requires persistent intrusion symptoms, avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event, negative mood or cognitive changes associated with the trauma, and increased arousal. PTSD is associated with psychological distress and often becomes chronic (Pietrzak et al., Citation2012; Yehuda et al., Citation2015), resulting not only in a burden for the individual suffering from PTSD, but also resulting in large costs for society (Davis et al., Citation2022). There are several evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Among these are Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), which are (strongly) recommended by most guidelines, except for a ‘suggested’ recommendation for EMDR by the APA guideline (APA, Citation2017; International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, Citation2018; NICE, Citation2018; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs;, Citation2023).Traditionally, evidence-based treatment for PTSD is delivered in an outpatient format, mostly in weekly sessions, which is generally associated with high dropout rates ranging from 30 to 62% (Ragsdale et al., Citation2020). Additionally, due to the spaced sessions, the treatment duration typically extends over several months. Hence, there is a need for more rapid symptom reduction and therapies with higher retention rates. In response to this, evidence-based in – and outpatient PTSD treatment programmes delivered in a massed intensive format have been developed (e.g. Bongaerts et al., Citation2017; Ehlers et al., Citation2014; Hendriks et al., Citation2010). The treatment results of these programmes are promising, as they have shown similar treatment outcomes compared to standard, less intensive trauma-focused therapies, with no reports of symptom exacerbation or increased drop-out rates. In fact, a current review indicates improved treatment retention rates (Ragsdale et al., Citation2020). While the precise reasons for the improved retention rates are not definitively understood, one hypothesis posits that patients may find it more feasible to commit to a shorter treatment duration.

Different intensive programmes have been investigated. A pilot study (N = 12) of a five-day intensive inpatient programme combining EMDR with trauma-informed yoga showed a decrease in PTSD symptoms and a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.91) and only one patient dropped out (Zepeda Méndez et al., Citation2018). Another three-week (15 days of treatment) intensive outpatient treatment for veterans (N = 191) showed large reductions in PTSD symptoms (Cohen's d = 1.12) and a dropout rate of 7.9% (Zalta et al., Citation2018). The programme consisted of CPT, mindfulness, yoga, and psychoeducation. Another study investigating the effects of an intensive outpatient PE therapy programme (N = 73) also showed a decrease in PTSD symptom severity with a large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.20) (Hendriks et al., Citation2018). The programme consisted of four consecutive days, with a total of 12 90-minute PE sessions, followed by four weekly booster 90-minute PE sessions. During the programme, there was a dropout rate of 5% during the booster phase. Additionally, several analyses of an intensive inpatient therapy programme (N = 347) consisting of eight days of PE, EMDR, sport activities, and psychoeducation sessions, showed a large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.64) for reducing PTSD symptoms, with a dropout rate of 2,3% (Van Woudenberg et al., Citation2018). The study of Zepeda Méndez et al. (Citation2018) and Zalta et al. (Citation2018) were lacking long term follow-up. The study of Hendriks et al. (Citation2018) had three – and six-month follow-ups which showed large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 1.2) and the study of Van Woudenberg et al. (Citation2018) also showed large effect sizes on a subsample at follow-up.

Besides the differences between the intensive programmes, there are also some similarities. For example, in most of the intensive treatment programmes, there is an addition of a physical activity. Several intensive trauma treatment programmes add yoga (Zepeda Méndez et al., 2018), interactive sports (Van Woudenberg et al., Citation2018) and/or running (Bongaerts et al., Citation2017) as an add-on component to their treatment. Preliminary evidence suggests that adding exercise to PE (Powers et al., Citation2015) or applying it as a standalone intervention (Fetzner & Asmundson, Citation2015) can reduce PTSD symptoms. A meta-analysis has indicated that various forms of physical activity may contribute to improved health of PTSD patients (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2015). However, there is no consensus on the optimal form or intensity of exercise. Also, a recent study (Voorendonk et al., Citation2023) did not show beneficial effects of adding physical exercise to an intensive inpatient trauma treatment compared to a non-active physical control condition.

So, combining (effective) treatment components in an intensive treatment programme seems to be a promising approach for delivering evidence-based interventions that can lead to a more rapid treatment response and high rates of retention. However, factors such as the number of sessions, the treatment setting (clinical or outpatient), and the specific types and amount of physical activity included need to be carefully considered. By describing the effects of a six-day programme, we aim to contribute to the existing body of evidence. The objective is to investigate whether a six-day intensive outpatient programme, combining PE and EMDR with various forms of physical activity and psychoeducation, can effectively decrease PTSD symptoms and result in remission of the PTSD diagnosis. A secondary goal is to assess whether the attrition rates in this programme are also low.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data from 183 patients diagnosed with PTSD and treated in an Intensive Outpatient Trauma Treatment programme at the Altrecht Academic Anxiety Centre between April 2018 and December 2020 were collected. The data collection was part of routine outcome monitoring. Data from 37 patients were excluded from the analysis: 15 patients dropped out of treatment, 15 patients explicitly objected to the use of their data for research purposes, and data from seven patients were classified as unreliable or invalid. The reasons for invalidity included difficulties understanding the questions (one patient), discontinuation of antidepressant medication during treatment (one patient), single trauma instead of multiple traumas (two patients), and invalid responses (two patients). Therefore, the analysis included data from 146 patients (89.7% female, mean age = 36.79, SD = 11.31).

Inclusion criteria for the intensive treatment programme were an established PTSD diagnosis according to the DSM-5 and a history of experiencing multiple traumas (at least four A-criterion trauma events as described in the DSM-5 PTSD criteria. The rationale behind requiring individuals to have experienced at least four criterion A events is to ensure that the programme caters specifically to those with a history of multiple traumatization.). Comorbid psychiatric disorders were not directly assessed by the treatment team; instead, the responsibility for this assessment was delegated to the referring therapist. Sedative medication was minimized, and alcohol and drug use were prohibited during treatment and for one month after treatment. Exclusion criteria were severe acute suicide risk without any backup from other mental health specialists, lack of proficiency in the Dutch language, unwillingness or difficulty participating in a group, and severe psychiatric symptoms that could interfere with trauma treatment.

2.2. Procedure

During the screening process, the patients were assessed using several measurement tools. The Dutch version of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013a; Dutch version Boeschoten et al., Citation2014a), a semi-structured interview, was administered to evaluate PTSD diagnoses and symptoms. The Life Events Checklist-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013b; Dutch version Boeschoten et al., Citation2014b) was used to assess traumatic events experienced by the patients. In addition to these measures, the screening phase included the administration of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013c; Dutch version Boeschoten et al., Citation2014c), which is a self-report measure used to assess PTSD symptoms. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, Citation1983; Dutch version De Beurs, Citation2006) was used to evaluate a range of psychological symptoms, and the Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition (BDI-II-NL; Beck et al., Citation1996; Dutch version Van der Does, Citation2002) was utilized to assess symptoms of depression. Furthermore, an assessment of the impact of trauma symptoms on daily life was conducted using a visual analogue scale (VAS; Crichton, Citation2001). These measurement tools provided a comprehensive assessment of PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and other psychological symptoms during the screening phase.

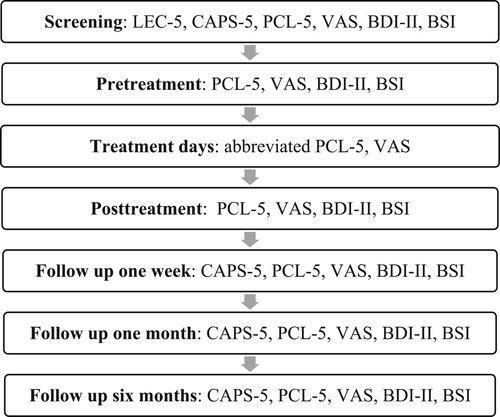

Once the eligibility of the patients was determined, a treatment plan was created. This plan included identifying the specific traumatic memories that would be targeted during treatment and determining a starting date for the intervention. The treatment itself was conducted over a period of three consecutive days, in two consecutive weeks of treatment. During the treatment process, measurements were taken at different time points. The initial screening involved assessments of the patients’ symptoms and experiences. The mean time between screening and pre-treatment was 62.57 days (SD = 50.11). Subsequently, measurements were taken on both the first day and the last day of treatment to evaluate the progress and outcomes. In addition to these assessments, follow-up measurements were carried out at one week, one month, and six months after the completion of the treatment. These follow-up measurements allowed for the evaluation of the long-term effects of the intervention (). Additionally, patients were asked to complete an abbreviated PCL-5 version and the trauma-VAS at the beginning of each treatment day.

2.3. Treatment

The intensive treatment programme lasted for a total of two weeks, with three consecutive treatment days in each week. Each treatment day included two individual trauma-focused therapy sessions, with each session lasting for 90 minutes. In addition to the individual therapy sessions, patients also participated in a 60-minute physical exercise session and a 60-minute psycho-education session each day. The physical exercise sessions were conducted in a group setting with up to four patients, and they involved trauma-sensitive yoga, interactive physical activities, or running. The treatment days were structured as follows: patients started with a session of PE, followed by a short break. After the break, they engaged in the designated physical exercise routine. Following the exercise session, there was a lunch break. Afterwards, an EMDR session took place, and the treatment day concluded with a psycho-education session. At the end of each treatment day, patients went home or stayed in a nearby clinic if necessary. The decision to stay in the clinic could be based on various factors, such as problems in the home situation, severe self-harm or suicide risk, or any other individual circumstances that required additional support and supervision. After three days of treatment, patients went home for four days before returning for week 2. All treatment components were delivered by different therapists, but all psychologists were trained in trauma treatment. For all treatment components, the same group of therapists rotated, following a model similar to the therapist rotation model outlined by Van Minnen et al. (Citation2018). The treatment differed from the more intensive treatment described in Wagenmans et al. (Citation2018), in being six instead of eight days, outpatient versus inpatient, one hour exercise per day versus six and one hour psycho-education instead of several hours per day. Also there was no joint lunch or dinner provided.

2.3.1. Trauma focused treatment

Trauma-focused treatment in the programme consisted of PE and EMDR. Both PE and EMDR are widely recognized and recommended evidence-based treatments for PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2017; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies, Citation2018; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Citation2018). Patients received PE treatment before EMDR daily. A recent study by Van Minnen et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that the sequence of these two trauma-focused treatments is important, with better treatment outcomes observed when PE is conducted prior to EMDR. Therapists followed the principles of the inhibitory learning approach in delivering PE, where expectancy violation is considered a crucial factor (Craske et al., Citation2014). During PE sessions, the goal was to expose patients to their traumatic memories by having them vividly describe the events in the present tense, focusing on as many details as possible, as if the trauma was happening again. At the beginning of each PE session, patients identified their harm expectancy (e.g. ‘I will go crazy’), which was then assessed at the end of the session. To maximize the expectancy violation, additional exposure in vivo elements such as sounds or photos could be incorporated to increase arousal levels. Towards the end of the session, homework assignments involving exposure in vivo were assigned to reinforce the learning effects outside of therapy sessions.

EMDR therapy was conducted by a therapist trained in EMDR, following the EMDR 2.0 protocol (Matthijssen & de Jongh, Citation2018, Citation2022). EMDR 2.0 is an enhanced version of EMDR therapy based on the standard Dutch protocol by Erik ten Broeke, Ad de Jongh and Hellen Hornsveld (version Citation2021), which itself is built upon the original EMDR protocol developed by Shapiro (Citation2017). The EMDR 2.0 protocol incorporates additional elements such as increased working memory taxation, modality-specific taxation, and arousal induction. It is believed to be more efficient compared to the standard protocol, as it requires fewer desensitization sets to achieve therapeutic effects (Matthijssen et al., Citation2021).

2.3.2. Physical exercise

Due to the lack of clear evidence supporting a specific type of physical activity as an add-on treatment, the programme incorporated a combination of different exercise modalities. The programme included three types of exercise: trauma-sensitive yoga (Emerson & Hopper, Citation2014), various sports games (e.g. badminton, ring hockey), and running. Each type of physical activity was offered twice during the treatment and was tailored to the individual's level of physical fitness.

2.3.3. Psycho-education

Psycho-education sessions were conducted daily for 60 minutes. The sessions covered various topics including ‘PTSD and treatment,’ ‘sleep hygiene,’ ‘how to deal with crisis,’ ‘dissociation,’ ‘feelings of anger, guilt, or shame,’ and ‘assertiveness’. During the first psycho-education session, which focused on explaining PTSD and the treatment programme, patients were encouraged to bring a significant other. The sessions followed the principles of psycho-education for PTSD (Keijsers et al., Citation2017) and utilized practice sheets from ‘Vroeger and Verder’ (Dorrepaal et al., Citation2009).

In addition to the psycho-education sessions, daily intervision and supervision sessions were conducted between the therapists. These sessions served as a platform to discuss the techniques used in PE/EMDR as well as the progress and individual needs of the patients.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. LEC-5

The Dutch version of the Life Events Checklist-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013b; Dutch version Boeschoten et al., Citation2014b) consists of 17 items. Patients were asked to indicate whether they have experienced exposure to potential traumatic events that meet the A-criterion of PTSD according to the DSM-5. The checklist helps in assessing the range of traumatic events that participants have experienced.

2.4.2. CAPS-5

The presence and severity of PTSD were assessed using the Dutch version (Boeschoten et al., Citation2014a) of the Clinician-Administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013a). The CAPS-5 is a 30-item clinical diagnostic interview for PTSD. Twenty of these items correspond to DSM-5 defined diagnostic criteria and are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (absent) to 4 (extreme or incapacitating), based on the frequency and intensity of the symptoms. The CAPS-5 allows for the determination of PTSD diagnosis, symptom severity, presence of the dissociative subtype, and late onset PTSD. Psychometric assessments of the CAPS-5 have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (Boeschoten et al., Citation2018). The CAPS-5 month version was administered at screening, one-month follow-up, and six-month follow-up assessments. The week version of the CAPS-5, assessing symptoms of the past week, was administered at screening, one-week follow-up, one-month follow-up, and six-month follow-up assessments.

2.4.3. PCL-5

The PCL-5 (Weathers et al., Citation2013c; Dutch version Boeschoten et al., Citation2014c) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 20 items designed to assess the DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD. Each symptom is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The scores for each item can be summed to obtain a total symptom severity score, which ranges from 0 to 80. Psychometric assessments have demonstrated strong internal consistency, test-retest reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Blevins et al., Citation2015). In the treatment programme, the week version of the PCL-5 was used, which assesses symptoms experienced during the past week.

2.4.4. VAS

Disturbance in daily life caused by PTSD symptoms was assessed by asking patients to indicate the extent to which they experienced suffering from their PTSD symptoms. This was measured using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; Crichton, Citation2001), which ranged from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely bothered).

2.5. Data analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 22.0). The data was carefully checked for entry errors and, in collaboration with the patients, any necessary adjustments were made. No outliers were removed from the dataset, as there was no prior justification for exclusion.

Paired sample t-tests were used to analyze treatment effects, and effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated using JASP (Version 0.14.1). Repeated measures ANOVA was performed in SPSS to assess the reduction in symptoms over time on the PCL-5 and VAS, including the pretreatment, posttreatment, follow-up at one week, and follow-up at one month. For analysis of results at six months follow up, paired sample t-tests were used. A mixed ANOVA was performed in SPSS to compare PTSD symptoms of patients with and without the dissociative subtype of PTSD. The Reliable Change Index (RCI) was calculated by dividing the difference between the pretreatment and posttreatment scores by the standard error of the difference between the two scores. The standard error of the difference was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha values, which were .90 for the CAPS, and .93 for the PCL-5. RCI values greater than 1.96 are reliable changes within the treatment sample (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Data from the final sample that completed the treatment were analyzed. The gender distribution in the sample was 10.3% male (N = 15, M age = 41.20, SD = 11.92) and 89.7% female (N = 131, M age = 36.28, SD = 11.17). All patients in the sample met the criteria for PTSD according to the DSM-5, with 47.3% of them also meeting the criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD (N = 69). According to the LEC, life events in the clusters of physical and sexual abuse were the most common reported traumatic experiences for which the patients sought treatment. The majority of patients (N = 125, 85.6%) reported having one or more current comorbid psychiatric disorders (see ). Missing data, resulting from participants not showing up for a measurement or the measurement being conducted too late, were not imputed and were excluded from the analysis (see ). The drop-out rate during treatment was 8.2%.

Table 1. Comorbid diagnosis.

Table 2. Mean scores and standard deviation of all measurement instruments and moments.

3.2. Treatment effects

3.2.1. CAPS-5

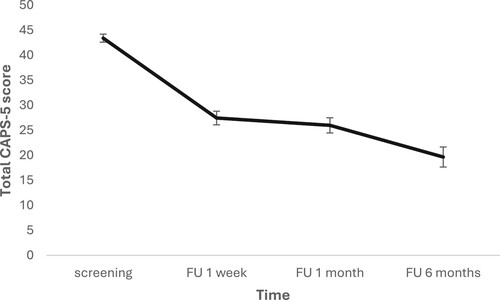

A significant decrease in PTSD symptoms from screening to one month follow up was found on the CAPS-5(M) (t(1, 123) = 12.53, p < .001, d = 1.13) (N = 124). The CAPS-5 score decreased with an average of 17.41 points. All 146 patients were diagnosed with PTSD at the screening (100%), however 52.4% (65 out of 124 patients) did not meet the PTSD criteria at one month follow-up. Moreover, a significant decrease in PTSD symptoms from screening to six months follow up was found on the CAPS-5 (t(1, 68) = 12.24, p < .001, d = 1.47) (N = 69) (). According to the CAPS-5, six months after treatment 68.1% (47 out of 69 patients) did not meet the criteria for PTSD. According to the Reliable Change index (RCI), most patients (73.39%) improved during treatment ().

Figure 2. Course of PTSD symptoms on the CAPS-5.

Note: Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Table 3. Reliable Change Index (RCI).

A mixed ANOVA showed that patients with a dissociative subtype of PTSD had a higher severity scoring at screening and follow up after one month compared to patients without this subtype (F(1, 114) = 9.906, p = .002, ηp2 = .080). However, no significant interaction effect was found, indicating this treatment was an effective treatment for both patient groups (p = .238).

3.2.2. PCL-5

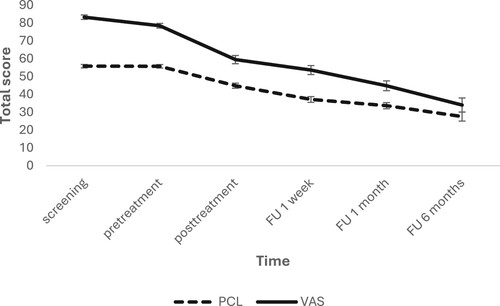

Scores on the PCL-5 were comparable during screening (M = 55.49, SD = 9.16) and pretreatment (M = 56.64, SD = 11.39) (t(85) = -.1.23, p = .223). As the screening contained more missing data, this data-point was not used in the analysis. A repeated measures ANOVA (N = 127) with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction indicated that self-reported PTSD symptoms significantly differed over time (pretreatment, posttreatment, one week follow up, one month follow up) on the PCL-5 (F(2.084, 262.568) = 124.748, p < .001, ηp2 = .498). Post hoc analysis using a Bonferroni correction showed significant differences between all timepoints (all p’s < .001), and a large effect from pretreatment to one month follow up (d = 1.59). Moreover, self-reported PTSD symptoms (PCL-5) decreased from screening to six months follow up (t(1, 54) = 12.07, p < .001, d = 1.63) (N = 55).

Similar to the results on the CAPS-5, patients with a dissociative subtype of PTSD reported more PTSD symptoms at screening and follow up after one month compared to patients without this subtype (F(1, 121) = 7.224, p = .008, ηp2= .056), but no significant interaction effect was found (p = .297).

3.2.3. VAS

Scores on the VAS did not differ significantly between screening (M = 82.53, SD = 11.49) and pretreatment (M = 79.80, SD = 16.81) (t(80) = 1.62, p = .109). Due to the amount of missing data at screening, only pretreatment data was used in the analysis. A repeated measures ANOVA (N = 121) with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction indicated that self-reported suffering due to PTSD significantly differed over time (pretreatment, posttreatment, one week follow up, one month follow up) as measured with the VAS (F(2.069, 248.259) = 84.490, p < .001, ηp2 = .413). Post hoc analysis using a Bonferroni correction showed significant differences between all time points (all p’s < .001), and a large decline in scores from pretreatment to one month follow up (d = 1.40). Self-reported suffering due to PTSD symptoms also decreased from screening to six months follow up (t(1, 54) = 11.01, p < .001, d = 1.49) (N = 55) ().

Figure 3. Course of self-reported PTSD symptoms on the PCL-5 and VAS.

Note: Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. The VAS scale ranges from 0–100. The PCL-5 ranges from 0–80.

In line with results on the CAPS-5 and PCL-5, patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD also reported more suffering of PTSD symptoms both at screening and follow up after one month compared to patients without this subtype (F(1, 117) = 6.243, p = .014, ηp2 = .051). No significant interaction effect was found (p = .158).

4. Discussion

The results of the present study provide evidence for the effectiveness of an intensive outpatient trauma treatment programme for patients with a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from multiple traumatization. The treatment programme, which consisted of six days of treatment within two weeks, combining PE and EMDR therapy with physical exercise and psychoeducation, resulted in a significant decline in PTSD symptoms from pretreatment to one-month and six-month follow-up assessments. Moreover, a considerable proportion of patients no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD after one month (52.4%) and six months of treatment (68.1%). The high rates of improvement observed, as indicated by the Reliable Change Index (RCI) at one month post treatment (CAPS-5: 73.39%, PCL-5: 77,61%), further support demonstrates that the treatment had a meaningful impact on the PTSD symptoms in most patients. Additionally, the low dropout rate observed in this study (8.2%) is consistent with previous findings in intensive trauma treatment programmes (Hendriks et al., Citation2018; Wagenmans et al., Citation2018). The intensive format of the treatment, with a concentrated schedule of therapy sessions over a relatively short period, may contribute to higher treatment retention rates compared to traditional weekly sessions.

The study contributes to the existing body of evidence on the effectiveness of intensive treatment programmes for PTSD. The findings are consistent with previous research that has explored the efficacy of intensive trauma treatment programmes. Studies investigating similar intensive programmes, both in inpatient and outpatient settings, have reported significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and high rates of treatment retention (Bongaerts et al., Citation2017; Ehlers et al., Citation2014; Hendriks et al., Citation2010; Zalta et al., Citation2018). These findings suggest that intensive treatment formats have the potential to enhance treatment efficiency and decrease dropout rates compared to traditional outpatient treatments. Furthermore, they seem feasible, safe and effective.

A strength of this study is the large sample size. Also the rigorous assessment measures are a strength. Both the large sample size and the use of objective and subjective measure for measuring PTSD symptoms add to the robustness of the findings. Also the use of a long term follow-up measurement is a strength and shows symptom reduction is maintained over time. Furthermore, the use of a combination of evidence based trauma treatments and the incorporation of physical activity as part of the treatment programme in an outpatient setting is unique and is important in an attempt to try to enhance treatment as much as possible. Although recent research (Voorendonk et al., Citation2023) did not find beneficial effects of adding physical exercise to an intensive inpatient trauma treatment in comparison to a control condition, other studies have shown that physical activity, such as yoga, sports, and running, can contribute to reducing PTSD symptoms (Powers et al., Citation2015; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2015). However, the optimal form and intensity of exercise for PTSD treatment remain unclear. In the current study, physical exercise was included as an add-on component to the trauma-focused therapy sessions. Although the specific type of physical activity was not standardized, it is encouraging that the treatment programme incorporating exercise yielded positive outcomes. Future research should aim to identify the effectiveness of physical exercise and the most effective and tailored physical exercise interventions for PTSD treatment.

Also, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the absence of a control group limits the ability to establish causality. However, from screening to pretreatment, where no treatment takes place, no symptom changes have been found, contributing to the conclusion that the treatment itself is responsible for the change. Although this result has been found, future research should consider employing randomized controlled trials with a control group to strengthen the evidence base. Second, while combining different elements is a strength of the study, it is also a limitation, because it makes it impossible to determine the specific contribution of each treatment component. In future research different treatment components should be submitted to head-to-head comparison or in different combinations. Third, the generalizability of the findings may be limited to the specific sample characteristics and the treatment setting. The majority of participants were female, and the study was conducted in an academic anxiety centre, which may not fully represent the diversity of individuals with PTSD or other treatment settings (e.g. refugees/asylum seekers and first responders). Future studies should aim for more diverse samples and assess the effectiveness of similar programmes in different clinical settings.

In conclusion, the present study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of a six-day intensive outpatient programme for individuals with PTSD. The findings highlight the potential of combining trauma-focused treatments, physical activity, and psycho-education to achieve significant symptom reduction. While the study has strengths, such as a large sample size, rigorous measurements and the inclusion of a long term follow up, it also has limitations, such as the lack of a control group and specific sample characteristics that need to be addressed in future research. Further investigations should utilize more rigorous study designs, include diverse samples, investigate the comparative effectiveness of different intensive treatment approaches and explore the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic benefits of physical exercise in PTSD treatment.

Disclosure statement

SMa receives income from providing trainings on enhancing trauma treament including intensifying treatment. There are nu further conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. 2017. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults; American Psychiatric Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation.

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Boeschoten, M. A., Bakker, A., Jongedijk, R. A., & Olff, M. (2014b). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5), Nederlandse vertaling.

- Boeschoten, M. A., Bakker, A., Jongedijk, R. A., & Olff, M. (2014c). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), Nederlandse vertaling.

- Boeschoten, M. A., Bakker, A., Jongedijk, R. A., van Minnen, A., Elzinga, B. M., Rademaker, A. R., & Olff, M. (2014a). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), Nederlandse vertaling.

- Boeschoten, M. A., Van der Aa, N., Bakker, A., Ter Heide, F. J. J., Hoofwijk, M. C., Jongedijk, R. A., Van Minnen, A., Elzinga, B. M., & Olff, M. (2018). Development and Evaluation of the Dutch Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1546085. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1546085

- Bongaerts, H., Van Minnen, A., & de Jongh, A. (2017). Intensive EMDR to treat patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder: A case series. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 11(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.11.2.84

- Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. (2017). American Psychiatric Association. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline.

- Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

- Crichton, N. (2001). Visual analogue scale (VAS). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10(5), 697–706. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00525.x

- Davis, L. L., Schein, J., Cloutier, M., Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P., Maitland, J., Urganus, A., Guerin, A., Lefebvre, P., & Houle, C. R. (2022). The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 83(3), https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.21m14116

- De Beurs, E. (2006). Brief Symptom Inventory Handleiding. PITS B.V.

- De Vries, G., & Olff, M. (2009). The lifetime prevalence of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(4), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20429

- Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700048017

- Dorrepaal, E., Thomaes, K., & Draijer, N. (2009). Vroeger en verder - Handboek + Werkboek (2de editie). Pearson Benelux B.V.

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., Deale, A., Stott, R., & Clark, D. M. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-Day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and Emotion-Focused Supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040552

- Emerson, D., & Hopper, E. (2014). Traumaverwerking door yoga (1ste editie). Altamira.

- Fetzner, M. G., & Asmundson, G. J. (2015). Aerobic exercise reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.916745

- Hendriks, L., De Kleine, R. A., Broekman, T. G., Hendriks, G., & Van Minnen, A. (2018). Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for chronic PTSD patients following multiple trauma and multiple treatment attempts. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1425574

- Hendriks, L., De Kleine, R. A., Van Rees, M., Bult, C., & Van Minnen, A. (2010). Feasibility of brief intensive exposure therapy for PTSD patients with childhood sexual abuse: A brief clinical report. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 1(1), https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5626

- International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). (2018). New ISTSS prevention and treatment guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.istss.org/treating-trauma/new-istssguidelines.aspx.

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

- Keijsers, G., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, K., & Emmelkamp, P. (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten I (2de editie). Boom Lemma.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., De Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, P., Lepine, J. P., Levinson, D., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

- Matthijssen, S. J., Brouwers, T., van Roozendaal, C., Vuister, T., & de Jongh, A. (2021). The effect of EMDR versus EMDR 2.0 on emotionality and vividness of aversive memories in a non-clinical sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1956793. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1956793

- Matthijssen, S. J. M. A., & de Jongh, A. (2018, 2022). EMDR 2.0 protocol.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116.

- Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, R. B., Southwick, S. M., & Grant, B. F. (2012). Psychiatric comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder among older adults in the United States: Results from wave 2 of the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1097/jgp.0b013e31820d92e7

- Powers, M. B., Medina, J. L., Burns, S., Kauffman, B. Y., Monfils, M., Asmundson, G. J., Diamond, A., McIntyre, C. K., & Smits, J. A. (2015). Exercise augmentation of exposure therapy for PTSD: Rationale and pilot efficacy data. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(4), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1012740

- Ragsdale, K. A., Watkins, L. E., Sherrill, A. M., Zwiebach, L., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2020). Advances in PTSD Treatment delivery: Evidence base and future directions for intensive outpatient programs. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00219-7

- Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 75, 964–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

- Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. Guilford Publications.

- Ten Broeke, E., de Jongh, A., & Hornsveld, H. (2021). EMDR Standaardprotocol.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2023). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VA-DoD-CPG-PTSD-Provider-Summary.pdf.

- Van der Does, A. J. W. (2002). BDI-II-NL. Handleiding. De Nederlandse versie van de Beck Depression Inventory-2nd edition. Harcourt Test Publishers.

- Van Minnen, A., Hendriks, L., Kleine, R. D., Hendriks, G. J., Verhagen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Therapist rotation: A novel approach for implementation of trauma-focused treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1492836. doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1492836

- Van Minnen, A., Voorendonk, E. M., Rozendaal, L., & de Jongh, A. (2020). Sequence matters: Combining prolonged exposure and EMDR therapy for PTSD. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113032

- Van Praag, D. L. G., Fardzadeh, H. E., Covic, A., Maas, A. I. R., & von Steinbüchel, N. (2020). Preliminary validation of the Dutch version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) after traumatic brain injury in a civilian population. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231857

- Van Woudenberg, C., Voorendonk, E. M., Bongaerts, H., Zoet, H. A., Verhagen, M., Lee, C. W., van Minnen, A., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Effectiveness of an intensive treatment programme combining prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for severe post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1487225. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1487225

- Voorendonk, E. M., Sanches, S. A., Tollenaar, M. S., Hoogendoorn, E. A., de Jongh, A., & van Minnen, A. (2023). Adding physical activity to intensive trauma-focused treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1215250

- Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., Sleijpen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1430962.

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013a). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; past-month version). Interview available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013b). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013c). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Yehuda, R., Flory, J. D., Bierer, L. M., Henn-Haase, C., Lehrner, A., Desarnaud, F., Makotkine, I., Daskalakis, N. P., Marmar, C. R., & Meaney, M. J. (2015). Lower methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter 1F in peripheral blood of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 77(4), 356–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.02.006

- Zalta, A. K., Held, P., Smith, D. L., Klassen, B. J., Lofgreen, A. M., Normand, P., Brennan, M. B., Rydberg, T. S., Boley, R. A., Pollack, M. H., & Karnik, N. S. (2018). Evaluating patterns and predictors of symptom change during a three-week intensive outpatient treatment for veterans with PTSD. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1816-6

- Zepeda Méndez, M., Nijdam, M. J., ter Heide, F. J. J., van der Aa, N., & Olff, M. (2018). A five-day inpatient EMDR treatment programme for PTSD: Pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1425575. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1425575