ABSTRACT

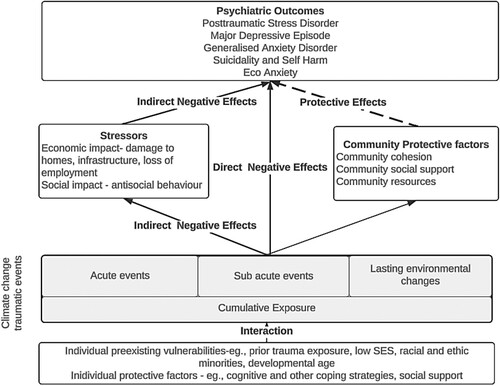

The European Journal of Psychotraumatology has had a long interest in advancing the science around climate change and traumatic stress. In this special issue, we include papers that responded to a special call in this area. Six major themes emerge from these papers and together they contribute to trauma and adversity model of the mental health impacts of climate change. We argue that, in addition to individual vulnerability factors, we must consider the (i) cumulative trauma burden that is associated with exposure to ongoing climate change-related impacts; (ii) impact of both direct and indirect stressors; (iii) individual and community protective factors. These factors can then guide intervention models of recovery and ongoing resilience.

HIGHLIGHTS

Trauma and adversity are central to understanding the mental health impacts of climate change.

We present a trauma and adversity model of the mental health impacts of climate change.

La Revista Europea de Psicotraumatología lleva mucho tiempo interesada en los avances de la ciencia en torno al cambio climático y el estrés traumático. En esta edición especial incluimos artículos que respondieron a un llamado especial en esta área. De estos artículos emergen seis temas principales y juntos contribuyen al modelo de trauma y adversidad de los impactos del cambio climático en la salud mental. Sostenemos que, además de los factores de vulnerabilidad individuales, debemos considerar: (i) la carga traumática acumulativa asociada con la exposición a los impactos continuos relacionados con el cambio climático; (ii) impacto de estresores tanto directos como indirectos; (iii) factores protectores individuales y comunitarios. Estos factores pueden luego guiar los modelos de recuperación y resiliencia continua.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been increasing attention devoted to understanding and mitigating the impacts of climate change on mental health (Berry et al., Citation2010; Charlson et al., Citation2021; Cianconi et al., Citation2020; Doherty & Clayton, Citation2011; Olff, Citation2023). This attention is the result of the increasing frequency and severity of climate change-related events (Basu et al., Citation2018; Edwards et al., Citation2024; Thompson et al., Citation2023) as well as the growing anxiety over the existential threat posed by climate change on human health and well-being to future generations (Heeren & Asmundson, Citation2023; Usher, Citation2022). The European Journal of Psychotraumatology has had a long interest in this issue (Olff, Citation2017, Citation2019) and in 2020 put out a call for studies advancing research in the area of climate change and traumatic stress (see Olff, Citation2022). The papers included in this special issue of the European Journal of Psychotraumatology draw from, and contribute to, a trauma-informed perspective on this topic. The central theme of this special issue is that trauma and adversity are central to our understanding of the mental health impacts of climate change. In this editorial, we argue that taking a trauma focus to this understanding is essential in order to evolve our thinking of resilience and recovery.

The 15 papers included in this special issue represent six major themes drawn from research on traumatic events directly associated with climate change (e.g. hurricanes, floods, wildfires) as well as events associated with other environmental stressors (e.g. earthquakes): (1) the complexity of climate change related mental health outcomes; (2) the impacts of exposure to multiple or simultaneous climate change-related events and stressors; (3) the moderators and mediators of vulnerability to climate change-related mental health outcomes; (4) individual and community resilience and protective factors; (5) the impacts of traumatic forms of climate change on child and adolescent mental health; and (6) the development and implementation of interventions designed to prevent or mitigate these impacts. Together they contribute to trauma and adversity model of the mental health impacts of climate change ().

2. Exposure to multiple climate change events

When describing climate change-related events and their mental health impacts, researchers tend to categorise disaster events based on their time course or chronicity. For example, events have been labelled as acute extreme weather events that last for days such as wildfires, hurricanes and floods; sub-acute events that last for months such as droughts and heat waves; and lasting environmental changes such as sea level rises, and permanently altered environments (Palinkas & Wong, Citation2020). Similarly, disaster response frameworks often classify psychosocial interventions based on their position in time relative to a single emergency event – i.e. addressing mental health symptoms in the aftermath of a disaster, versus building mental health preparedness and resilience for future disasters (Mrazek & Haggerty, Citation1994). While this way of categorising events is useful, a trauma-informed perspective would also have us recognise the importance of cumulative events. As the global effects of climate change continue to worsen, not only are natural disaster events increasing in frequency, communities are increasingly more likely to be impacted by multiple and overlapping disaster events (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2023; Leppold et al., Citation2022). In this Special Issue, Agyapong et al. (Citation2022) found that the number of traumatic disasters experienced a five-year period (including COVID, wildfire and flood events) was associated with both the prevalence and severity of mental health conditions including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression episode and generalised anxiety disorder. We can expect that the global burden of mental health problems will continue to escalate as the climate crisis worsens and cumulative disaster exposure becomes the norm, and that these impacts will be disproportionately felt by minority communities more directly affected by climate change (Pearson et al., Citation2023). As such, there is a clear need for researchers, policy makers and disaster response agencies to consider the compounding mental health impacts of exposure to multiple or simultaneous climate change-related events and stressors.

3. Complexity of climate change-related mental health outcomes

A range of mental health outcomes has been associated with the impacts of climate change-related disaster events. Although disaster events are frequently traumatic in nature and are most typically associated with the emergence of posttraumatic stress symptoms (Agyapong et al., Citation2022; Chen et al., Citation2023; Massazza et al., Citation2022; van der Does et al., Citation2023), the mental health sequelae of disasters are complex and may also include symptoms of anxiety (Agyapong et al., Citation2022; Richez et al., Citation2022), depression (Agyapong et al., Citation2022; Chen et al., Citation2023), and general psychological distress (Pardon et al., Citation2024; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Further, a scoping review article in this Special Issue indicated that amongst individuals, lasting environmental changes associated with climate change (particularly heat and heatwaves) result in increased mortality risk, suicide and suicidal behaviours, and psychiatric morbidity amongst individuals with mental health conditions (Massazza et al., Citation2022). It is therefore clear that the mental health impacts of climate change extend beyond the acute effects of natural disasters, and that long-term alterations to the environment caused by climate change will continue to worsen mental health outcomes over time.

4. Moderators and mediators of vulnerability

A trauma lens also provides important information when considering who is vulnerable to poor mental health outcomes following the impacts of climate change. In a longitudinal study, Liang et al. (Citation2023) found a cumulative, dose-related relationship between childhood trauma/stressful life events, and the later mental health response to disaster events. While social support had a buffering effect, this effect was not seen for those with a high stress load. It is also well demonstrated that there are demographic disparities that moderate the health effects of climate change (Benevolenza & DeRigne, Citation2019), particularly among vulnerable populations such as low-income individuals (Tekin et al., Citation2023) and racial and ethnic minorities (Berberian et al., Citation2022). Pertinently, in addition to individual pre-existing vulnerabilities, the financial stressors emerging directly from extreme disaster events are a core mediator between these events and their adverse mental health outcomes. For example, economic factors such as damage to homes and infrastructure, threats to livelihood and employment, and the associated financial stressors (Berry et al., Citation2010, Citation2018; Hayes et al., Citation2018) are all contributors to negative mental health outcomes beyond the direct effects of trauma exposure and physical danger (Zhang et al., Citation2022). Accordingly, a trauma-informed perspective on the mental health outcomes of climate change must consider both pre-existing vulnerabilities and post-disaster stressors which mediate the effects of disasters and other climate change events.

5. Resilience and protective factors

Studying the protective factors which promote mental health resilience in the face of adversity and trauma – both at the individual and community levels – is essential to informing preparedness and response to climate change events. Frameworks of post-disaster resilience highlight that community systems and social support are central ecological resources that buffer against the negative mental health effects of climate change and related disasters (Ungar & Theron, Citation2020). In this Special Issue, Bakic and Ajdukovic (Citation2021) found that interpersonal and community resources, including social support from loved ones and the community; as well as individual resources, such as psychological resilience; were associated with greater mental health and life satisfaction in members of flood-affected communities in Croatia. Similarly, Liu et al. (Citation2021) found greater social support increases self-compassion and posttraumatic growth in the aftermath of trauma; as well as increasing prosocial and reducing antisocial behaviours. Individual-level psychosocial resources are also critical protective factors against negative mental health outcomes, with Tekin et al. (Citation2023) finding that in survivors of Hurricane Katrina, factors such as hope for the future, efficient coping strategies, and acceptance of the situation were associated with recovery trajectories of posttraumatic stress, reflected in improvements in individuals’ symptoms over time. While the cumulative impacts of climate change are severe, this evidence points to a number of individual- and community-level protective factors which may buffer the negative mental health effects of climate change-related disaster events and lasting environmental changes.

6. Child and adolescent mental health

Childhood and adolescence are critical developmental periods characterised by complex neurodevelopmental changes. Exposure to childhood trauma is associated with disruptions in normative cognitive and biological (i.e. genetic, neurodevelopmental, and hormonal) functioning that confer risk for psychiatric illness (McKay et al., Citation2021). In this Special Issue, there was a particular focus on mechanisms that underpin the emergence and maintenance of mental health problems in children and adolescents exposed to climate change-related natural disasters. In a longitudinal study of Chinese children and adolescents exposed to the Zhouqu debris flow, Liang et al. (Citation2023) identified that depressive symptoms were stable over the two-year study period, with feelings of self-hate, loneliness and sleep disturbance most central to the enduring experience of depression over time. Given the multifaceted developmental processes occurring in this period, it is notable that one study also found that the clinical expression of mental health responses to natural disasters diverged by age group. In children exposed to a violent storm in France (Richez et al., Citation2022), acute stress responses amongst 0–5-year-olds were more typically characterised by agitation and developmental regression, whereas 6–11-year olds were more likely to report experiencing anxiety.

It is worth noting that factors influencing mental health outcomes post-disaster are not restricted to individual-level personal characteristics, but also include higher-level factors concerning the disaster itself or the community’s subsequent response. Factors such as the severity of disaster and level of exposure to the event can confer further vulnerability for mental health problems (Khan et al., Citation2023). Indeed, after the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake (Ohnuma et al., Citation2023), exposure to television media coverage of the victims was associated with greater psychopathology among children and greater psychological distress among their parents.

As well as identifying factors which confer risk for mental health problems in children and adolescents post-disaster, this Special Issue also sheds light on a number of factors that support resilience and adaptive functioning in a post-disaster environment. Liu et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that in Chinese teenagers exposed to the Ya’an earthquake, greater social support had a positive impact on prosocial behaviours, both directly and indirectly via increasing self-compassion and posttraumatic growth; as well as reducing antisocial behaviour. The importance of social support, particularly from parents and caregivers, was echoed by a narrative review examining the potential impact of the Turkey–Syria earthquake on the psychological well-being of the affected children and adolescents (Khan et al., Citation2023). The review also highlights the need for long-term mental health support services – co-designed by affected communities, to ensure their cultural appropriateness and effectiveness and encourage help-seeking – so that children and adolescents can receive ongoing mental health support after the initial acute disaster event.

7. Intervention

The psychosocial needs of communities post-disaster are highly complex, and the specific needs of individuals can vary greatly. Although effective psychological interventions for disaster-related mental health problems exist, the scarcity of mental health workers limits the practicality of trained mental health professionals delivering sustained care to individuals and communities affected by disaster. Task-shifting approaches, which shift service delivery from highly qualified health workers to individuals with lower qualifications (Seidman & Atun, Citation2017), may be one way of increasing community capability to respond to the mental health needs post-disaster.

In this Special Issue, two studies investigated the efficacy of a skills-based psychosocial intervention that adopted a task-shifting model to address psychological distress following climate change disasters. The Skills fOr Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) programme (O’Donnell et al., Citation2020) was found to reduce psychological distress and posttraumatic stress symptoms in cyclone-affected communities in the Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu (Gibson et al., Citation2021), relative to Usual Care. Similarly, the SOLAR programme was found to significantly reduce anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms relative to an active Self-Help condition in a sample of individuals affected by compound disasters in rural and regional Australia (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2023). Interestingly, the findings from this randomised controlled trial highlighted the need to consider the cumulative events, with the authors suggesting booster sessions would be useful to maintain treatment effects when ongoing stressors occur. These findings highlight that flexible, scalable low-intensity psychosocial interventions delivered by laypeople could form a critical part of post-disaster recovery by allowing for more optimised allocation of mental health resources, so that the diverse mental health needs of individuals can be most effectively addressed. Importantly, the SOLAR programme provides skills to manage exposure to traumatic events, which as this editorial argues, is an essential part of understanding and addressing the mental health impacts of climate change.

The growing evidence that communities impacted by disasters are increasingly impacted by multiple disasters blurs the question of when the most appropriate time is to intervene with an intervention like the SOLAR programme. For a single disaster event, the idea of 3–12 months post disaster is a useful time to consider utilising interventions targeted to psychosocial distress. However, for communities impacted by multiple disasters over time, this is less clear. It may be that an intervention like the SOLAR programme which is conducted in the aftermath of a particular disaster (as a recovery response) becomes a part of a preparedness response for a future disaster. It is essential that research and policy agendas consider systems being impacted by multiple disasters, and recognise that communities may be simultaneously engaging in preparedness, response and recovery phases relating to different disaster events.

8. Conclusion

Although the trauma and adversity focus represented in this special issue is largely derived from the experience of acute climate change related events, it offers the potential for illuminating the causes and consequences of mental health outcomes typically associated with the existential and long-term threats of climate change to human health and well-being. Governments and emergency response organisations are increasingly looking to the research community to guide them on how to foster both individual and community psychosocial resilience and recovery in the face of climate change-related impacts. This sits as a challenge to the research field, and we must bring our trauma expertise to these important questions. To this end, we applaud efforts for global research collaborations in this area such as the climate change theme of the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (www.global-psychotrauma.net/climate). As each year continues to surpass the preceding year as the hottest on record, and as the number of people exposed to these events continues to rise, the urgency of conducting such collaborations and research will only continue to increase.

References

- Agyapong, B., Shalaby, R., Eboreime, E., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Owusu, E., Adu, M. K., Mao, W., Oluwasina, F., & Agyapong, V. I. (2022). Cumulative trauma from multiple natural disasters increases mental health burden on residents of Fort McMurray. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2059999. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2059999

- Bakic, H., & Ajdukovic, D. (2021). Resilience after natural disasters: The process of harnessing resources in communities differentially exposed to a flood. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1891733. doi:10.1080/20008198.2021.1891733

- Basu, R., Gavin, L., Pearson, D., Ebisu, K., & Malig, B. (2018). Examining the association between apparent temperature and mental health-related emergency room visits in California. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(4), 726–735. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx295

- Benevolenza, M. A., & DeRigne, L. (2019). The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: A systematic review of literature. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(2), 266–281. doi:10.1080/10911359.2018.1527739

- Berberian, A. G., Gonzalez, D. J., & Cushing, L. J. (2022). Racial disparities in climate change-related health effects in the United States. Current Environmental Health Reports, 9(3), 451–464. doi:10.1007/s40572-022-00360-w

- Berry, H. L., Bowen, K., & Kjellstrom, T. (2010). Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. International Journal of Public Health, 55(2), 123–132. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0

- Berry, H. L., Waite, T. D., Dear, K. B., Capon, A. G., & Murray, V. (2018). The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 282–290. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0102-4

- Charlson, F., Ali, S., Benmarhnia, T., Pearl, M., Massazza, A., Augustinavicius, J., & Scott, J. G. (2021). Climate change and mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4486. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094486

- Chen, X.-Y., Wang, D., Liu, X., Shi, X., Scherffius, A., & Fan, F. (2023). Cumulative stressful events and mental health in young adults after 10 years of Wenchuan earthquake: The role of social support. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2189399. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2189399

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 74. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

- Cowlishaw, S., Gibson, K., Alexander, S., Howard, A., Agathos, J., Strauven, S., Chisholm, K., Fredrickson, J., Pham, L., Lau, W., & O’Donnell, M. (2023). Improving mental health following multiple disasters in Australia: A randomized controlled trial of the Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) program.

- Doherty, T. J., & Clayton, S. (2011). The psychological impacts of global climate change. American Psychologist, 66(4), 265. doi:10.1037/a0023141

- Edwards, B., Taylor, M., & Gray, M. (2024). The influence of natural disasters and multiple natural disasters on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: Findings from a nationally representative cohort study of Australian adolescents. SSM - Population Health, 25, 101576. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101576

- Gibson, K., Little, J., Cowlishaw, S., Ipitoa Toromon, T., Forbes, D., & O’Donnell, M. (2021). Piloting a scalable, post-trauma psychosocial intervention in Tuvalu: The Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience program. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1948253.

- Hayes, K., Blashki, G., Wiseman, J., Burke, S., & Reifels, L. (2018). Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 1–12. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0210-6

- Heeren, A., & Asmundson, G. J. (2023). Understanding climate anxiety: What decision-makers, health care providers, and the mental health community need to know to promote adaptative coping. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102654. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102654

- Khan, Y. S., Khan, A. W., & Alabdulla, M. (2023). The psychological impact of the Turkey-Syria earthquake on children: Addressing the need for ongoing mental health support and global humanitarian response. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2249788. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2249788

- Leppold, C., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Reifels, L., & Quinn, P. (2022). Public health implications of multiple disaster exposures. The Lancet Public Health, 7(3), e274–e286. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00255-3

- Liang, Y., Chen, Y., Huang, Q., Zhou, Y., & Liu, Z. (2023). Network structure and temporal stability of depressive symptoms after a natural disaster among children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2179799. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2179799

- Liu, A., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2021). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth mediate the relations between social support, prosocial behavior, and antisocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1864949. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1864949

- Massazza, A., Ardino, V., & Fioravanzo, R. E. (2022a). Climate change, trauma and mental health in Italy: A scoping review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2046374. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2046374

- Massazza, A., Joffe, H., Parrott, E., & Brewin, C. R. (2022b). Remembering the earthquake: Intrusive memories of disaster in a rural Italian community. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2068909. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2068909

- McKay, M. T., Cannon, M., Chambers, D., Conroy, R. M., Coughlan, H., Dodd, P., Healy, C., O’Donnell, L., & Clarke, M. C. (2021). Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(3), 189–205. doi:10.1111/acps.13268

- Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academy Press.

- O’Donnell, M. L., Lau, W., Fredrickson, J., Gibson, K., Bryant, R. A., Bisson, J., Burke, S., Busuttil, W., Coghlan, A., & Creamer, M. (2020). An open label pilot study of a brief psychosocial intervention for disaster and trauma survivors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 483. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00483

- Ohnuma, A., Narita, Z., Tachimori, H., Sumiyoshi, T., Shirama, A., Kan, C., Kamio, Y., & Kim, Y. (2023). Associations between media exposure and mental health among children and parents after the Great East Japan Earthquake. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2163127. doi:10.1080/20008066.2022.2163127

- Olff, M. (2017). 2016: A year of records. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1281533. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1281533

- Olff, M. (2019). Facts on psychotraumatology. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1578524. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1578524

- Olff, M. (2022). Sexual assault as a public health problem and other developments in psychotraumatology. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2045130. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2045130

- Olff, M. (2023). Crises in the anthropocene. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2170818. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2170818

- Palinkas, L. A., & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 12–16. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

- Pardon, M. K., Dimmock, J., Chande, R., Kondracki, A., Reddick, B., Davis, A., Athan, A., Buoli, M., & Barkin, J. L. (2024). Mental health impacts of climate change and extreme weather events on mothers. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1), 2296818. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2296818

- Pearson, A. R., White, K. E., Nogueira, L. M., Lewis Jr, N. A., Green, D. J., Schuldt, J. P., & Edmondson, D. (2023). Climate change and health equity: A research agenda for psychological science. American Psychologist, 78(2), 244. doi:10.1037/amp0001074

- Richez, A., Gindt, M., Battista, M., Nachon, O., Menard, M.-L., Askenazy, F., Fernandez, A., & Thümmler, S. (2022). Storm Alex: Acute stress responses in the pediatric population. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2067297. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2067297

- Seidman, G., & Atun, R. (2017). Does task shifting yield cost savings and improve efficiency for health systems? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12960-017-0200-9

- Tekin, S., Burrows, K., Billings, J., Waters, M., & Lowe, S. R. (2023). Psychosocial resources underlying disaster survivors’ posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories: Insight from in-depth interviews with mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2211355. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2211355

- Thompson, R., Lawrance, E. L., Roberts, L. F., Grailey, K., Ashrafian, H., Maheswaran, H., Toledano, M. B., & Darzi, A. (2023). Ambient temperature and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(7), e580–e589. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00104-3

- Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441–448. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1

- Usher, C. (2022). Eco-Anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(2), 341–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.020

- van der Does, F. H., Nagamine, M., van der Wee, N. J., Chiba, T., Edo, N., Kitano, M., Vermetten, E., & Giltay, E. J. (2023). PTSD Symptom dynamics after the great east Japan earthquake: Mapping the temporal structure using Dynamic Time Warping. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2241732. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2241732

- Zhang, Y., Workman, A., Russell, M. A., Williamson, M., Pan, H., & Reifels, L. (2022). The long-term impact of bushfires on the mental health of Australians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2087980. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2087980