ABSTRACT

Background: With the introduction of the ICD-11 into clinical practice, the reliable distinction between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) becomes paramount. The semi-structured clinician-administered International Trauma Interview (ITI) aims to close this gap in clinical and research settings.

Objective: This study investigated the psychometric properties of the German version of the ITI among trauma-exposed clinical samples from Switzerland and Germany.

Method: Participants were 143 civilian and 100 military participants, aged M = 40.3 years, of whom 53.5% were male. Indicators of reliability and validity (latent structure, internal reliability, inter-rater agreement, convergent and discriminant validity) were evaluated. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and partial correlation analysis were conducted separately for civilian and military participants.

Results: Prevalence of PTSD was 30% (civilian) and 33% (military) and prevalence of CPTSD was 53% (civilians) and 21% (military). Satisfactory internal consistency and inter-rater agreement were found. In the military sample, a parsimonious first-order six-factor model was preferred over a second-order two-factor CFA model of ITI PTSD and Disturbances in Self-Organization (DSO). Model fit was excellent among military participants but no solution was supported among civilian participants. Overall, convergent validity was supported by positive correlations of ITI PTSD and DSO with DSM-5 PTSD. Discriminant validity for PTSD symptoms was confirmed among civilians but low in the military sample.

Conclusions: The German ITI has shown potential as a clinician-administered diagnostic tool for assessing ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD in primary care. However, further exploration of its latent structure and discriminant validity are indicated.

HIGHLIGHTS

This study validated the German International Trauma Interview (ITI), a semi-structured clinician-administered diagnostic interview for ICD-11 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Internal reliability, inter-rater agreement, latent structure, and convergent validity were explored in trauma-exposed clinical and military samples from five different in- and outpatient centres in Germany and German-speaking Switzerland.

The findings supported the German ITI's reliability, inter-rater agreement, convergent validity and usefulness from a patient perspective. Future research should explore its factor structure and discriminant validity, for which differences between the samples were found.

Antecedentes: Con la introducción de la CIE-11 en la práctica clínica, la distinción confiable entre el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) y el trastorno de estrés postraumático complejo (TEPTC) se vuelve primordial. La Entrevista Internacional de Trauma (ITI por sus siglas en inglés) semiestructurada administrada por un clínico tiene como objetivo cerrar esta brecha en los entornos clínicos y de investigación.

Objetivo: Este estudio investigó las propiedades psicométricas de la versión alemana de la ITI entre muestras clínicas expuestas a traumas de Suiza y Alemania.

Método: Los participantes fueron 143 civiles y 100 militares, edad M = 40.3 años, de los cuales el 53.5% eran hombres. Se evaluaron los indicadores de confiabilidad y validez (estructura latente, confiabilidad interna, acuerdo entre evaluadores, validez convergente y discriminante). El análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) y el análisis de correlación parcial se realizaron por separado para los participantes civiles y militares.

Resultados: La prevalencia del TEPT fue del 30% (civiles) y del 33% (militares) y la prevalencia de TEPTC fue del 53% (civiles) y del 21% (militares). Se encontró una consistencia interna y un acuerdo entre evaluadores satisfactoria. En la muestra militar, se prefirió un modelo parsimonioso de primer orden de seis factores a un modelo AFC de segundo orden de dos factores de la ITI TEPT y alteraciones en la autoorganización (AAO). El ajuste del modelo fue excelente entre los participantes militares, pero ninguna solución fue encontrada en los participantes civiles. En general, la validez convergente estuvo respaldada por correlaciones positivas de ITI TEPT y AAO con DSM-5 TEPT. La validez discriminante de los síntomas de TEPT se confirmó entre los civiles, pero fue baja en la muestra militar.

Conclusiones: La ITI alemana ha demostrado un potencial como herramienta de diagnóstico administrada por clínicos para evaluar el TEPT y el TEPTC del CIE-11 en atención primaria. Sin embargo, se requiere una mayor exploración de su estructura latente y su validez discriminante.

1. Introduction

The 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; WHO, Citation2019) describes two sibling disorders following exposure to a traumatic experience: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD (CPTSD). A PTSD diagnosis requires exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events, such as short- or long-lasting exposure to natural or human-made disasters, combat, serious accidents, sexual violence as well as learning about the sudden, unexpected or violent death of a loved one. PTSD symptoms are organised into three clusters: re-experiencing the trauma in the here and now, avoidance of traumatic reminders, and a persistent sense of current threat. CPTSD describes a broader array of symptoms, comprising all PTSD symptoms plus additional Disturbances in Self-Organization (DSO) symptoms, which fall into three clusters: affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbances in relationships. A person may only be diagnosed with PTSD or CPTSD, but not both. CPTSD is typically associated with multiple, prolonged experiences of interpersonal traumatisation from which it is difficult to escape, such as repeated childhood sexual or physical abuse, domestic violence, prolonged combat exposure, torture, and genocide campaigns (WHO, Citation2019). However, the type of trauma is a risk factor rather than a requirement for a diagnosis of CPTSD (Brewin, Citation2020; Maercker et al., Citation2022). Research has shown that the CPTSD diagnosis relates to a broader set of experiences in the social-interpersonal context, such as higher levels of functional impairment, more negative trauma-related cognitions about the self and the world, and higher levels of attachment insecurities (Karatzias et al., Citation2017, Citation2018).

With the introduction of the ICD-11 into clinical practice, the development and implementation of valid assessment tools for PTSD and CPTSD will become paramount. Specifically, the reliable distinction between PTSD and CPTSD is important because the two mental health diagnoses may require different treatment approaches. The benefit of multicomponent interventions for CPTSD, which besides trauma-focused strategies also include distress tolerance and emotional self-regulatory skills, is currently debated among experts (Coventry et al., Citation2020; Karatzias & Cloitre, Citation2019). Valid diagnostic instruments are thus central for future clinical research and practice. To date, two partner instruments have been developed to assess ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD: the self-report International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ; Cloitre et al., Citation2018) and the clinician-administered International Trauma Interview (ITI; Roberts et al., Citation2019). A body of literature using the ITQ in various clinical and non-clinical samples of different cultural backgrounds confirms the validity of the questionnaire and illustrates that two distinct symptom profiles related to PTSD and CPTSD can be distinguished based on both factor analyses (e.g. Redican et al., Citation2021) and network analyses (Knefel et al., Citation2020; Levin et al., Citation2021). The validity of the individual items was confirmed in analyses based on item response theory (Christen et al., Citation2021; Cloitre et al., Citation2018). However, treatment guidelines stress that in order to establish a diagnostic status of PTSD and CPTSD, structured validated clinical interviews conducted by trained professionals along with standardised trauma checklists are needed (Schäfer et al., Citation2019).

The semi-structured clinician-administered ITI aims to fill the gap for reliable and valid assessment tools for ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD in clinical and research settings. It is an expansion of the already established self-report measure ITQ. In agreement with the WHO's policy of parsimony and clinical utility (Reed, Citation2010), the ITI focuses on assessing six PTSD core symptoms, six DSO core symptoms as well and functional impairment by each core symptom cluster. Versions of the ITI have been validated in two published studies: First, an earlier ITI version was tested in a Swedish trauma-exposed community sample, which resulted in several changes in the original interview questions (Bondjers et al., Citation2019); second, the updated version was validated in a Lithuanian trauma-exposed community sample (Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022). In both studies, an acceptable model fit was found for both a six-factor correlated model as well as a two-factor second-order model that included PTSD and DSO symptoms as latent factors. Composite reliability was high (.86–.88 for PTSD and .89–.92 for DSO) and convergent and discriminant validity were supported through robust associations of PTSD symptoms with indicators of fear and anxiety and DSO symptoms with depression, dysthymia, emotion regulation difficulties and social phobia scales (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022).

The primary aim of the present study was the investigation of the psychometric properties of the newly translated German version (for all German-speaking regions, i.e. Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, South-Tirol) of the ITI in a clinical sample collected in five therapy centres. This included the assessment of latent structure, internal reliability, inter-rater agreement, and convergent validity and discriminant validity. Moreover, the usefulness and duration of the diagnostic interview from the patients’ perspective were examined in a subsample.

Based on data from previous ITI and ITQ validations (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022), we hypothesised that both a six-factor correlated model and a second-order two-factor model of PTSD and DSO symptoms would fit the data well and that internal reliability and inter-rater agreement would be satisfactory. Convergent validity was operationalised as the association between ITI PTSD and DSO with DSM-5 PTSD (measured by the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist 5; PCL-5) as the two instruments assess similar constructs. Discriminant validity was operationalised as the association of ITI PTSD and DSO with different mental health indicators (e.g. anxiety, depression), which can also represent trauma sequelae. Regarding convergent validity, we expected high positive correlations for ITI PTSD symptoms with intrusions, avoidance, and arousal according to the PCL-5 whereas ITI DSO symptoms would correlate most substantively with PCL-5 alterations in cognitions and mood. Regarding discriminant validity, we expected significant but smaller positive associations between ITI PTSD and anxiety/phobic anxiety as PTSD is often viewed as a fear-based disorder (Maercker et al., Citation2022). We further expected DSO symptoms, which occur across a variety of contexts regardless of proximity to a traumatic stressor, to be associated with depression, borderline symptoms, aggression/hostility, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and interpersonal sensitivity.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

To assess a sample with high proportions of potential PTSD and CPTSD diagnoses, participants seeking treatment for trauma-related distress were recruited from five clinical departments: 1. Integrated Psychiatry Winterthur, Switzerland; 2. Bundeswehr Center for Military Mental Health, Germany; 3. Civil in- and outpatient centres in Germany, namely Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences, Campus Benjamin Franklin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences, Campus Mitte, as well as the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine at the Central Institute of Mental Health Mannheim. Inclusion criteria were exposure to at least one traumatic experience; being ≥18 years; no clinical signs of acute psychosis, no primary diagnosis of a severe cognitive or substance abuse disorder; no acute suicidality that requires admission to a closed ward; substantial knowledge of German. Each participant was informed that participation in the study is voluntary and that withdrawal of consent will not affect subsequent treatment. All participants were provided a participant information sheet and gave written informed consent. In most cases, self-report questionnaires were filled in before the clinical interview. However, since the study was conducted in a naturalistic primary care setting, this could vary, depending on the capacity and daily schedule of the treatment centres. Moreover, to reduce demands on patients and staff, not all assessment centres included all of the self-report measures. Participants did not receive financial remuneration.

Data were collected by 30 interviewers (29 with MSc in Psychology or MD in Psychiatry who were licensed psychotherapists or therapists in training; one advanced psychology student with clinical experience). The training took approximately three hours and included: 1. theoretical introduction of ICD-11 concepts; 2. ITI coding rules; 3. sample patient interview and group discussion of ratings. Interviewers who joined the study team at a later point were either trained with video recordings of the training session or personal instruction. Uncertainties in scoring or study procedures were discussed with the study supervisors at each site. Inter-rater reliability was determined in the military subsample by an independent interviewer who conducted a separate interview within one week (n = 84). Both interviews took place in the beginning of the treatment. In the following, the specific procedures of each treatment centre are described.

2.1.1. Integrated Psychiatry Winterthur

Inpatients were recruited at a specialised inpatient ward for stress-related disorders at the Integrated Psychiatry Winterthur (ipw), Switzerland, from February 2020 to November 2021. Informational flyers were handed to participants upon admission by their therapists and the study was explained. A total of 85 participants registered to participate, of whom four withdrew consent before data collection (e.g. due to ending inpatient treatment prematurely) and four withdrew during data collection as the interview questions were too burdensome, resulting in n = 77 participants who completed the study. The study was approved by the cantonal ethics committee of Zurich (ID 2019-02071).

2.1.2. Treatment centres in Germany

Inpatients and outpatients were recruited between October 2020 and March 2022 at the consultation centres of both Departments of Psychiatry and Neurosciences, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Central Institute of Mental Health Mannheim via waiting lists for inpatient treatment, the institutional website, and social media. As data collection for this study was integrated into a larger project focused on the treatment of nightmares in PTSD, additional inclusion criteria were applied: a PTSD diagnosis according to DSM-5 and a total score ≥ 26 on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013b); at least two nightmares per week. Exclusion criteria included lifetime cannabis abuse or dependence and a score >29 on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Study dropouts were not recorded. The final subsample consisted of n = 66 individuals who were almost exclusively outpatients. The study was approved by the ethics commission of Berlin (Ethikkommission des Landes Berlin, nr: 19/0384–IV E11).

2.1.3. German military

In- and outpatients seeking treatment for trauma-related distress were recruited at the Bundeswehr Center for Military Mental Health between November 2020 and January 2022. Patients included both active-duty military personnel and veterans. They were approached by psychiatrists who provided information about the study. Less than 2% of invited patients did not participate in the data collection. One participant ended data collection prematurely. In total, n = 100 participants provided data for this study. The study was approved by the ethics commission of the Charité Berlin (ID EA1/182/20).

2.1.4. Total sample

The final sample included in the analysis comprised 243 participants, aged 40.31 years (SD = 11.27, range = 18–65), 53.5% were male. Demographics for participants from the different centres are presented in . Among the civilian participants, the most prevalent traumatic experiences were physical assault, which was experienced or witnessed by n = 102 (71.3%), followed by sexual assault n = 90 (62.9%) and other unwanted sexual experiences n = 75 (52.4%). Among the military participants, the most prevalent traumatic experiences were combat/exposure to a war zone, which was experienced or witnessed by n = 87 (87.0%), followed by severe human suffering n = 75 (75.0%) and fire or explosion n = 74 (74.0%). provides further details on trauma exposure.

Table 1. Demographics.

Table 2. Overall trauma exposure.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. International Trauma Interview (ITI; Roberts et al., Citation2019)

The ITI is a semi-structured clinical interview to investigate potential diagnoses of PTSD and CPTSD following the ICD-11 conceptualisation. The structure of the ITI is similar to the CAPS-5 (Weathers et al., Citation2013b). First, an index traumatic experience is specified to which symptom assessments pertain. Second, using pre-formulated diagnostic questions, clinicians evaluate the endorsement of three PTSD symptom clusters with two items each: 1. Re-experiencing (nightmares, intrusive memories/flashbacks); 2. Avoidance of internal or external reminders of the traumatic experience; 3. Persistent perception of heightened current threat (hypervigilance, exaggerated startle reaction) which started or got worse after the traumatic experience. Both frequency and intensity of symptoms during the last four weeks are evaluated on a five-point scale from ‘absent’ (0) to ‘extreme/incapacitating’ (4). Each symptom can be further specified by several additional questions provided. When there is insufficient memory of the experience (e.g. following traumatic brain injury, heavy alcohol intoxication, being drugged or childhood abuse), emotional reactivity to internal or external trauma-related cues is explored as an indicator of intrusions. Functional impairment related to PTSD symptoms is evaluated regarding social functioning, occupational functioning and functioning in other important areas of life on a scale from ‘no adverse impact’ (0) to ‘extreme impact, little or no functioning’ (4).

The three DSO symptom clusters reflect how patients typically feel and think about themselves and how they relate to others. Two items are evaluated for each symptom cluster: 1. Affect dysregulation, including hyperactivation (heightened emotional reactions to minor stressors) and hypoactivation (emotional numbing or dissociation); 2. Persistent negative self-concept (feeling like a failure, feelings of worthlessness); 3. Disturbances in relationships (persistent feelings of being distant from others or having difficulties in maintaining close relationships). Frequency and intensity of DSO symptoms were indicated on a five-point scale from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘extremely’ (4). Impairment in social functioning, occupational functioning and functioning in other important areas is evaluated in three items on a scale from ‘no adverse impact’ (0) to ‘extreme impact, little or no functioning’ (4). To be classified as DSO symptoms, the difficulties must be perceived as related to the traumatic experience(s). The criterion of trauma-relatedness is fulfilled if a symptom began or got worse following trauma exposure. Trauma-relatedness is rated as ‘definite’, ‘likely’, or ‘unlikely’, whereby symptoms rated as ‘unlikely’ should not be counted as endorsed when applying the diagnostic algorithm.

The total ITI score ranges from 0 to 48. A diagnosis of PTSD requires the endorsement of at least one of two symptoms from each of the three PTSD symptom clusters, plus endorsement of functional impairment associated with these symptoms (severity ≥ 2). A diagnosis of CPTSD requires the presence of PTSD and the endorsement of at least one of two symptoms from each of the three DSO symptom clusters, plus endorsement of functional impairment associated with these symptoms (severity ≥ 2).

The German translation of the ITI included updates made after the Swedish validation (Bondjers et al., Citation2019) and was created by researchers of the University of Zurich (Schnyder & Maercker, Citation2020) in collaboration with the authors of the original version. It is a predecessor of the current release version of the ITI (Roberts et al., Citation2022).

2.2.2. Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013)

The LEC-5 assesses exposure to 16 frequent traumatic events in the Western context and one additional item for any other extraordinarily stressful event. Participants specify if they experienced the event themselves, witnessed the event, learned about a situation happening to someone close, exposure was job-related or if it does not apply. In line with the ICD-11 trauma definition, trauma was rated as endorsed if participants experienced the event themselves (including job-related exposure) or witnessed the event personally. The LEC-5 was completed in all subsamples.

2.2.3. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013a)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report scale corresponding to the DSM-5 PTSD criteria. It assesses four symptom clusters: intrusions (5 items), avoidance (2 items), negative alterations in cognitions and mood (7 items) and alterations in arousal and reactivity (6 items). Respondents indicate how much they have been bothered by each PTSD symptom over the past month, using a 5-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘very strongly’ (4) (range: 0–80). Higher scores represent more severe psychopathology. The German version of the PCL-5 has been found a reliable instrument with good diagnostic accuracy (Krüger-Gottschalk et al., Citation2017). Cronbach's alpha in the current study was α = .91 for the total sum score. The PCL-5 was completed in all subsamples.

2.2.4. Beck Depression Inventory revised (BDI-II; Beck et al., Citation1996)

The 21-item BDI-II is among the most widely used self-report scales for assessing the severity or intensity of depressive symptoms. Items are rated on a four-point scale, ranging from ‘0’ (symptom not present) to ‘3’ (strong presence of symptom) (range: 0–63). Higher scores represent more severe psychopathology. The German version of the BDI-II has good psychometric properties (Kühner et al., Citation2007). Cronbach's alpha in the current study was α = .92 for the total sum score. The BDI-II was assessed in the German military and Swiss inpatient subsamples.

2.2.5. Borderline Symptom List-short version (BSL-23; Bohus et al., Citation2009)

The BSL-23 is a 23-item self-rating instrument for specific assessment of borderline-typical symptomatology based on criteria of the DSM-IV. Subjective severity of symptoms in the past week is assessed on a five-point Likert scale from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘very strong’ (4) (range:0–92). Higher scores represent more severe psychopathology. The measure was developed and validated in German and showed good psychometric properties (Bohus et al., Citation2009). Cronbach's alpha in the current study was α = .94 for the total sum score. The BSL-23 was assessed in the Swiss inpatient ward and the treatment centres in Germany.

2.2.6. Brief Symptom Inventory

The BSI-53 (BSI-53; Derogatis, Citation1993) is a widely used measure for screening psychopathology during the preceding seven days. The subscales assess somatisation (7 items), obsessive-compulsiveness (6 items), interpersonal sensitivity (4 items), depression (6 items), anxiety (6 items), aggression (5 items), phobic anxiety (5 items), paranoid ideation (5 items), and psychoticism (5 items). Subjective severity of symptoms in the past week is assessed on a five-point Likert scale from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘very strongly’ (4) (range: 0–212). Higher scores represent more severe psychopathology. The German version of the BSI -53 (Franke, Citation2015) is well-validated and widely used. Cronbach's alpha of relevant subscales were: anxiety α = .91, .90; aggression α = .88, .86; phobic anxiety α = .85, .85; interpersonal sensitivity α = .88, .85; paranoid ideation α = .84, .83; psychoticism α = .83, .80, in the military and civilian samples, respectively. The BSI-53 was assessed in the German military and Swiss inpatient subsamples.

2.2.7. Usefulness and duration

After concluding the clinical interview, usefulness and duration of the ITI were evaluated with the following questions: ‘Overall, how would you rate the usefulness of the diagnostic interview?’ (‘very good’, ‘quite good’, ‘rather low’, ‘very low’); ‘How would you rate the duration of the interview?’ (‘very good’, ‘acceptable’, ‘a little bit too long’, ‘much too long’).

2.2.8. Demographics

Information about age, gender, civil status, employment, and education were assessed.

2.3. Data analysis

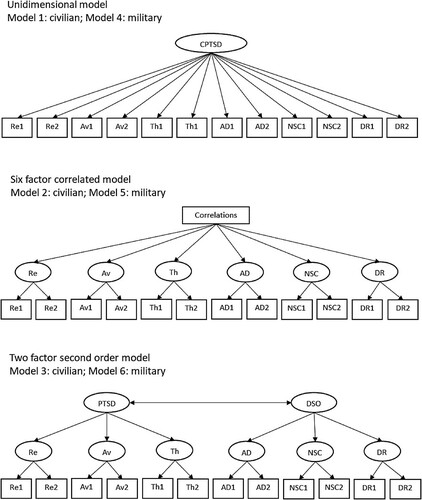

First, we calculated descriptive statistics and diagnostic rates for PTSD and CPTSD and assessed group differences between participants from the five treatment centres. Diagnostic status was determined by applying the ICD-11 diagnostic algorithm to the ITI items. Second, internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha; Cronbach, Citation1951) was calculated. Inter-rater reliability (Krippendorff's alpha; Hayes & Krippendorff, Citation2007) was determined among 84 participants in the German Military subsample for whom two interviewers conducted separate ITI interviews. Data from the first interview was used for the subsequent analyses. Third, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the fit of the preferred model from previous ITI validation studies (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022). As demographic and descriptive results showed that the military and civilian samples strongly differ (e.g. gender ratio, full-time work percentage, most frequent exposure types), they were analysed separately. We conducted two nested CFA model comparisons in each of the two subsamples (German military sample and combined German-Swiss civilian sample): In the first, we compared a unidimensional model to a six-factors correlated model, and in the second, we compared the six-factors correlated model to a. two-factor second-order model. Nested models can be compared using the chi-square difference test, which tests whether the difference in chi-square values between two models is significant or not. A significant chi-square difference indicates that the more complex model fits the data better than the simpler model. Consequently, two unidimentional models (models 1, 4), two six-factor correlated models (models 2, 5) and two two-factor second-order models (models 3, 6) were tested. The unidimensional model acted as a comparison model (see ). Finally, partial correlations were tested between ITI PTSD and DSO and external variables to explore the hypotheses for convergent and discriminant validity using SPSS 28. It was tested how strongly the individual PTSD and DSO facets associated with sum scores of other mental health questionnaires, controlling for age and gender. The variables assessed in all subsamples were: age, gender, PCL-5; inpatient ward Switzerland and German military: BDI-II, BSI-53; inpatient ward Switzerland and treatment centres Germany: BSL-53. Finally, a frequency rating of the usefulness and duration of the interview was calculated among the subsample of Swiss inpatients (n = 77).

Figure 1. Alternative tested models of the latent structure of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD symptoms.

Note: PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, DSO = Disturbances in Self-Organization, CPTSD = Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Re = Re-experiencing, Av = Avoidance, Th = Sense of current threat, AD = Affect dysregulation, NSC = Negative-self-concept, DR = Disturbed relationships.

The following model fit indicators were considered in CFA analyses: a non-significant chi-square (χ2) result indicates good model fit; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) values ≥.95 excellent fit and ≥.90 represent adequate fit; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values ≤.06 indicate excellent fit, ≤.08 represent good fit, and ≤.10 represent adequate fit (Bentler, Citation1990; Kline, Citation2011; Steiger, Citation1990). Beyond fit statistics, models were compared regarding parsimony and consistency with theoretical assumptions in ICD-11. Data were analysed using Mplus. Missing data ranged between 2% (inpatient ward Switzerland) and 10% (treatment centres Germany). Maximum likelihood estimation was used, to handle missingness.

3. Results

3.1. PTSD and CPTSD in the sample

When scoring the ITI, a total of n = 43 (30%) civilians and n = 33 (33%) military participants fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. An additional n = 76 (53%) civilians and n = 21 (21%) military participants reported CPTSD (). Descriptive statistics for the ITI and other measures are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 3. Endorsement of ITI symptoms and diagnostic rates.

3.2. Internal consistency and inter-rater agreement

Satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach's α) was found for civilian and military samples, respectively: α = .73, .83, for PTSD; α = .85, .87 for DSO; α = .84, .86 for total score. The inter-rater agreement (Krippendorff's α), available only in the military subsample (n = 84), was good (α = .80 for PTSD; α = .83 for DSO; α = .89 for total score).

3.3. Factorial validity

presents the fit statistics for the six different models that were tested. The six-factor correlated model was preferred over the unidimensional model in the military sample (χ2Δ p value < .001). In the civilian sample, the fit statistics showed that no model demonstrated a good enough fit. The best fit was identified for the six-factor correlated model, yet its fit indexes were not adequate (satisfactory CFI (0.91) and SRMR (0.05) but poor TLI (.85) and RMSEA (0.11)). Attempts at modifying the models by adding additional correlations between errors did not yield better fit. Due to the ambiguity in the solutions, it was not possible to definitively choose a specific model.

Table 4. Model fit statistics for the alternative models of the International Trauma Interview.

In the military sample, the difference between models 5 and 6 was not significant (χ2Δ = 10.97 (df Δ = 8) p = .203), indicating that the more parsimonious model, i.e. the six-factors correlated model, was preferred, and with excellent model fit statistics. Standardised factor loadings for the chosen ITI models are presented in Supplementary materials (Tables S2a, S2b). Factor loadings were all positive, significant (p < .001), and ranged from moderate to high.

3.4. Convergent and discriminant validity

Zero-order bivariate correlations among study variables are presented in Supplementary materials (Table S3). Next, partial correlations between the ITI subscales and other study variables controlling for age and gender were calculated. presents correlations between ITI PTSD and DSO, on the one hand, and PCL-5 subscales (representing convergent validity), and BDI, BSL and BSI (representing discriminant validity), on the other hand, separately for the civilian and military samples. Among civilians, ITI PTSD was associated most strongly with PCL intrusions (large effect), followed by arousal, cognitions and mood (moderate effects) and avoidance (small effect). In the military sample, ITI PTSD was associated most strongly with PCL intrusions, followed by avoidance, arousal and cognitions and mood (large effects). Regarding ITI DSO symptoms, among civilians, significant associations were found with PCL cognitions and mood and arousal (small effects). In the military sample, ITI DSO correlated most strongly with PCL cognitions and mood, followed by arousal (large effects) and intrusions and avoidance (moderate effects).

Table 5. Partial correlation coefficients between ITI subscales and PCL subscales, BDI and BSI, controlling for age and gender: Civilian (above diagonal) and military participants (below diagonal).

Regarding discriminant validity, depression was associated most strongly with ITI DSO in both samples (moderate to large effects). Borderline symptoms among civilians were not significantly associated with ITI PTSD and DSO. In the military sample, all BSI subscales were significantly associated with ITI PTSD and DSO (moderate-large effects). The civilian sample presented a more varied picture whereby ITI PTSD symptoms correlated significantly with BSI anxiety and paranoid symptoms (small effects) and DSO correlated significantly with interpersonal sensitivity, aggression, paranoid and psychotic symptoms (small to moderate effects).

3.5. Patients’ ratings of usefulness and duration of the ITI

A total of 39% of the Swiss inpatients reported the usefulness to be very good, 57.1% as quite good and 3.9% as rather low. Regarding the duration of the interview, 27.3% indicated it to be very good, 58.4% quite good, 13% a little bit too long, and 1.3% much too long.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the psychometric properties of the German version of the International Trauma Interview (ITI) for the assessment of ICD-11 CPTSD and PTSD. It is the first clinical study to validate the ITI among trauma-exposed in-and outpatients with high prevalence rates of PTSD (37%, 33%) and CPTSD (53%, 21%) for civilian and military participants, respectively. Overall, the results are largely in line with validation studies in two other languages (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022), providing first evidence to support the German ITI's psychometric properties and demonstrating its applicability in various clinical contexts. Moreover, the majority of patients reported the usefulness and duration of the ITI to be quite good or very good.

While the civilian and military samples were relatively similar concerning age and educational background, they also showed relevant differences, both in terms of demographic characteristics such as gender (military: majority male, civilians: majority female) or professional functioning (military: majority working full-time, civilians: minority working full-time) and regarding types of trauma exposure. Among the military sample, combat exposure was most prevalent, whereas civilians reported higher levels of sexual and physical assault than military participants. In agreement with the exposure patterns, PTSD prevalence was similar in both samples, but civilians were diagnosed with CPTSD twice as frequently. As the violence during combat is not personally directed against the soldier, the relational working models may often not be challenged to a degree that would initiate changes in self-organisation (Bachem et al., Citation2019). Sexual and physical abuse, on the other hand, are often repeated, distinctly interpersonal and deliberately perpetuated by one human to another. Given these differences between the samples, validity analyses were conducted separately for the two samples.

In the present study, inter-rater agreement in diagnostic status using the ITI was distinctly higher than previously documented during the ICD-11 field studies based on unstructured clinical interviews (Reed et al., Citation2018). Moreover, the present results document similar inter-rater agreement as in the Lithuanian and Swedish ITI validations (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022), although a more stringent methodology was used. Instead of independently scoring audio or video recordings of ITI assessments, two separate assessments were conducted by different interviewers. The current results thus provide strong support for inter-rater agreement of the German ITI, promising increased concordance among clinicians.

In the military sample, the first-order six-factor CFA model was preferred over a second-order two-factor model of PTSD and DSO symptoms. This approach is statistically and conceptually more parsimonious and thus in accordance with the ICD-11's prototype matching approach, which suggests that among core symptoms of a disorder hierarchies should be avoided (Maj, Citation2011; Reed, Citation2010). Following, each of the symptom groups is equally likely to contribute to the diagnosis of CPTSD. In the military sample, the second-order two-factor model also presented an excellent fit, which is in line with studies using the ITQ in clinical samples, where usually both first- and second-order models presented a good fit (Redican et al., Citation2021), suggesting that both can be used for research and clinical purposes.

However, while among the military sample the factorial structure was excellent, the civilian sample resulted in a non-definitive solution as several fit statistics were not within the traditionally accepted thresholds for a good or adequate fit. This discrepancy in fit indices may be attributed to several factors, including the inherent complexity of the model, potential measurement errors, or the specific nature of the data and sample characteristics. For example, the larger number of centres and interviewers involved in collecting the civilian sample (four centres, 24 interviewers) compared to the military sample (one centre, six interviewers) as well as the higher heterogeneity among civilian participants may have resulted in individual differences, higher variance, and error levels. The findings thus suggest that a cautious interpretation and replication of this study with different civilian samples would be valuable to verify the model's robustness and generalizability.

An exploration of intercorrelations between study variables showed distinct differences between the civilian and military samples. While among civilian participants small to moderate associations of ITI PTSD and DSO with other study variables were found, in the military sample almost all associations were moderate to large. These results could be related to the fact that the samples are different by definition as the military sample comprised uniquely of members of the German Bundeswehr that, though different, are exposed to similar treatment characteristics in the same centre and perhaps share a more similar life course. The homogeneous nature of the primarily male military sample may have led to easier detection of effects.

Overall, the convergent validity of the ITI was supported by substantial associations of ITI PTSD symptoms with the sub-scales of the PCL-5. In both samples, the largest associations were found for ITI-PTSD symptoms and PCL-5 intrusions, which aligns with results obtained for the ITQ (Cloitre et al., Citation2021). Moreover, ITI DSO symptoms correlated most strongly with PCL-5 alterations in mood and cognitions, a symptom cluster that covers several relevant aspects of ICD-11 DSO (i.e. a negative self-concept, and relationship difficulties). Surprisingly, however, we found that PCL-5 alterations in mood and cognition correlated with ITI PTSD to a similar extent as with DSO. This finding may be accounted for by the fact that alterations in mood and cognitions include negative feelings such as fear and horror (Weathers et al., Citation2013). As the ICD-11 conceptualises PTSD symptoms as a conditioned fear response to a highly threatening experience (Maercker et al., Citation2022), the high associations are conclusive.

Indicators of discriminant validity included a variety of mental health measures that can represent trauma sequelae other than PTSD and DSO symptoms. As expected, ITI PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with BSI general anxiety in both samples, and the effect size was larger than for DSO symptoms. However, in the military sample, we found similar size correlations between ITI PTSD and sub-scales of the PCL-5 as between ITI PTSD and anxiety, which contrasted with our hypothesis. In the civilian sample, the hypothesis was confirmed as the associations between ITI PTSD and sub-scales of the PCL-5 were larger than the correlations between ITI PTSD and measures of anxiety. ITI DSO correlated more strongly with depression than was the case for ITI PTSD symptoms, replicating a pattern found in previous studies using the ITI (Bondjers et al., Citation2019; Gelezelyte et al., Citation2022) and ITQ (Hyland et al., Citation2017). Further in line with hypotheses, BSI subscales that assess aspects of self-worth or relating to others were more strongly associated with ITI DSO than PTSD symptoms. These included interpersonal sensitivity (i.e. perceptions of inadequacy and inferiority to others), paranoid symptoms (i.e. experiencing distrust and suspicion), psychoticism (i.e. feelings of isolation and alienation from others) and aggression (i.e. hostility, irritability, emotional outbursts). It is noteworthy, however, that while we did find the assumed pattern of associations, DSO symptoms correlated to a similar extent with the PCL-5 cognitions and mood subscale as with other conceptually related mental health indicators and thus their discriminant validity was low. These results mirror the breadth of the DSO construct, which includes symptoms that may occur in a range of different psychopathologies (Camden et al., Citation2023; Eberle & Maercker, Citation2023).

Finally, contrary to our hypothesis, associations with borderline symptoms were not significant in partial correlation analysis. These low associations may be partially explained by different interpersonal relationship patterns between patients with borderline personality disorder and patients with CPTSD. While patients with borderline personality disorder tend to engage in intense but volatile relationships, patients with CPTSD tend to avoid intimate relationships altogether. Moreover, while CPTSD patients have a consistently negative self-identity, borderline patients experience an unstable and shifting sense of self (Cloitre et al., Citation2014; Maercker et al., Citation2022).

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, all study variables used to assess convergent and discriminant validity were measured with self-report instruments. Second, despite being large for a trauma-exposed clinical sample, statistical power for advanced analyses was limited. Third, no official ITI training materials were available when the study was conducted, and the training provided was shorter than currently recommended by the authors of the ITI. This is of particular relevance considering the mixed results regarding factorial validity in the civilian sample, for which data were collected by a large number of interviewers in different treatment centres. Fourth, the specific focus on trauma treatment of most participating centres has resulted in a severely impaired sample, which limits the generalizability of the results to less impaired patient groups. Moreover, the time point of the index event was not recorded and thus could not be considered as a variable potentially associated with the validity of the instrument. Fifth, data were collected in a naturalistic primary care context and study procedures and assessment instruments could not be fully standardised. Moreover, one sub-sample was recruited according to narrower inclusion criteria than the others, which may have resulted in systematic differences between the civilian sub-samples that were not taken into consideration and could have affected the ability to get an adequate model fit in this sample. However, the heterogeneity of the sample under investigation (civil and military patients, in- and outpatients from two countries) is also a strength of this study, as it suggests that the ITI has the potential to be applied in various clinical contexts and populations.

In conclusion, the present results provide first evidence that the German version of the ITI is a reliable and valid instrument for the assessment of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD in primary care. While the results on internal consistency and retest reliability of the German ITI were conclusive, future research should continue to explore its factor structure and discriminant validity, for which differences between the samples were found in the present study. The existence of validated diagnostic tools is crucial to prepare the ground for the implementation of ICD-11 as the official diagnostic system in German-speaking countries.

Supplementary Table S2a and S2b factor loadings.docx

Download MS Word (18.3 KB)Supplementary Table S1 means and SDs.docx

Download MS Word (20.6 KB)Supplementary Table S3 Intercorrelations.docx

Download MS Word (20.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Access to the German Military subsample must be requested from the German Ministry of Defense ([email protected]) while the data collected in civil in- and outpatient centres in Germany and Switzerland are available from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bachem, R., Levin, Y., & Solomon, Z. (2019). Trajectories of attachment in older age: Interpersonal trauma and its consequences. Attachment & Human Development, 21(4), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1479871

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed. Manual. The Psychological Corporation.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R. D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., Steil, R., Philipsen, A., & Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): Development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1159/000173701

- Bondjers, K., Hyland, P., Roberts, N. P., Bisson, J. I., Willebrand, M., & Arnberg, F. K. (2019). Validation of a clinician-administered diagnostic measure of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD: The International Trauma Interview in a Swedish sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1665617. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1665617

- Brewin, C. R. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A new diagnosis in ICD-11. BJPsych Advances, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.48

- Camden, A. A., Petri, J. M., Jackson, B. N., Jeffirs, S. M., & Weathers, F. W. (2023). A psychometric evaluation of the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) in a trauma-exposed college sample. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(1), 100305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2022.100305

- Christen, D., Killikelly, C., Maercker, A., & Augsburger, M. (2021). Item response model validation of the German ICD-11 International Trauma Questionnaire for PTSD and CPTSD. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 3(4), e5501. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.5501

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25097. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25097

- Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Prins, A., & Shevlin, M. (2021). The international trauma questionnaire (ITQ) measures reliable and clinically significant treatment-related change in PTSD and complex PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1930961

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., Karatzias, T., & Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12956

- Coventry, P. A., Meader, N., Melton, H., Temple, M., Dale, H., Wright, K., Cloitre, M., Karatzias, T., Bisson, J., Roberts, N. P., Brown, J. V. E., Barbui, C., Churchill, R., Lovell, K., McMillan, D., & Gilbody, S. (2020). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 17(8), e1003262. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Derogatis, L. R. (1993). Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (3rd ed.). National Computer Systems.

- Eberle, D. J., & Maercker, A. (2023). Stress-associated symptoms and disorders: A transdiagnostic comparison. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(5), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2858

- Franke, G. H. (2015). Die Brief-Symptom-Checkliste mit 53 Items – Standardform – Deutsches Manual. Hogrefe.

- Gelezelyte, O., Roberts, N. P., Kvedaraite, M., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Kairyte, A., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., & Kazlauskas, E. (2022). Validation of the International Trauma Interview (ITI) for the clinical assessment of ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) in a Lithuanian sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2037905. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2022.2037905

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

- Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Downes, A. J., Jumbe, S., Karatzias, T., Bisson, J. I., & Roberts, N. P. (2017). Validation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 136(3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12771

- Karatzias, T., & Cloitre, M. (2019). Treating adults with complex posttraumatic stress disorder using a modular approach to treatment: Rationale, evidence, and directions for future research. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 870–876. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22457

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., Roberts, N., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., & Cloitre, M. (2017). Evidence of distinct profiles of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.032

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M. M., Bradley, A., Kitchiner, N. J., Jumbe, S., Bisson, J. I., & Roberts, N. P. (2018). The role of negative cognitions, emotion regulation strategies, and attachment style in complex post-traumatic stress disorder: Implications for new and existing therapies. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12172

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Knefel, M., Lueger-Schuster, B., Bisson, J., Karatzias, T., Kazlauskas, E., & Roberts, N. P. (2020). A cross-cultural comparison of ICD-11 complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptom networks in Austria, the United Kingdom, and Lithuania. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22361

- Krüger-Gottschalk, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Rau, H., Dyer, A., Schäfer, I., Schellong, J., & Ehring, T. (2017). The German version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 379. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1541-6

- Kühner, C., Bürger, C., Keller, F., & Hautzinger, M. (2007). Reliabilität und validität des revidierten Beck- Depressionsinventars (BDI-II). Befunde aus deutschsprachigen stichproben. Der Nervenarzt, 78(6), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-006-2098-7

- Levin, Y., Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Bachem, R., Maercker, A., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2021). Comparing the network structure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in three African countries. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.041

- Maercker, A., Cloitre, M., Bachem, R., Schlumpf, Y. R., Khoury, B., Hitchcock, C., & Bohus, M. (2022). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. The Lancet, 400(10345), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

- Maj, M. (2011). Psychiatric diagnosis: Pros and cons of prototypes vs. operational criteria. World Psychiatry, 10(2), 81–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00019.x

- Redican, E., Nolan, E., Hyland, P., Cloitre, M., McBride, O., Karatzias, T., Murphy, J., & Shevlin, M. (2021). A systematic literature review of factor analytic and mixture models of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102381

- Reed, G. M. (2010). Toward ICD-11: Improving the clinical utility of WHO’s international classification of mental disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(6), 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021701

- Reed, G. M., Sharan, P., Rebello, T. J., Keeley, J. W., Medina-mora, E., Gureje, O., Matsumoto, C., Onofa, L. U., Paterniti, S., Purnima, S., Robles, R., Mart, J. N. I., Elena Medina-Mora, M., Gureje, O., Luis Ayuso-Mateos, J., Kanba, S., Khoury, B., Kogan, C. S., Krasnov, V. N., … Pike, K. M. (2018). The ICD-11 developmental field study of reliability of diagnoses of high-burden mental disorders: Results among adult patients in mental health settings of 13 countries. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20524

- Roberts, N. P., Cloitre, M., Bisson, J., & Brewin, C. R. (2019). International Trauma Interview (ITI) for ICD- 11 PTSD and complex PTSD (Test Version 3.1).

- Roberts, N. P., Cloitre, M., Bisson, J., & Brewin, C. R. (2022). International Trauma Interview (ITI) for ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD. Release version 1.0.

- Schäfer, I., Gast, U., Hofmann, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Lampe, A., Liebermann, P., Lotzin, A., Maercker, A., Rosner, R., & Wöller, W. (2019). Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung. S3 Leitlinie der Deutschsprachigen Gesellschaft für Psychotraumatologie (DeGPT). Springer Verlag.

- Schnyder, U., & Maercker, A. (2020). Internationales Trauma Interview (ITI) für ICD-11 PTBS und Komplexe PTBS. Studienintervention Version 1.1. Unpublished version.

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

- Weathers, F., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013a). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). National Center for PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013b). The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). National Center for PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2019). International classification of diseases 11th revision (ICD-11).