ABSTRACT

The importance of school leaders’ work for the development of schools is often highlighted in the research literature. However, school leadership is enacted in a social setting influenced by political, cultural, historical, and economic factors across societal as well as national settings. In Sweden, the turnover rates of school principals are high specifically among novice principals. This empirical study aims to contribute to our understanding of turnover related to structures and principal agency in the Swedish context by exploring the early stages of school principals’ careers, their work environments, and their ideas about careers and motives for action. The study is based on interviews with 14 novice principals, situated at the site of their school leader education and their workplace. The findings show a constant movement among novice principals regarding their work location, work responsibilities, and positioning within their current status, during their first years of duty as a principal. The findings reveal how structures and career agency consolidate ongoing movements, making it challenging to develop professional agency and situated concerns. The career movements of novice principals within the Swedish market-oriented school system revealed the educational sector to be positioned as a marketplace and the principal as a wear-and-tear item.

Introduction

The importance of school leaders’ work for the development of schools is often highlighted in the research literature (e.g. Ahlström & Aas, Citation2020; Seashore Louis et al., Citation2010). However, school leadership is enacted in a social setting influenced by political, cultural, historical, and economic factors across societal as well as national settings (Jerdborg, Citation2023; Valle & Lillejord, Citation2023; Walker et al., Citation2007). Moreover, everyday encounters in schools are multifaceted, often political and linked to the national context, structuring, and affecting work-life experiences through cultural norms and policies (Shevchuk et al., Citation2019).

To be a novice as a principal in such a setting is demanding, resulting in many countries struggling with a lack of induction, high turnover, and alarming burnout among novice principals (Bush & Oduro, Citation2006; DeMatthews et al., Citation2023). That is, few individuals are prepared to meet challenges, such as limited resources and institutional and systemic complexity. Hence, turnover among novice principals as well as increased crises in principals’ supply have been found in several countries around the world (e.g. Gronn & Rawlings-Sanaei, Citation2003; Stevenson & Walker, Citation2006). Principal turnover most often includes principal changes to other schools, regions, positions, & exits from the school system altogether. However, turnover has been researched, defined, and conceptualized in diverse ways in the international literature. Other terms such as mobility and retention are also in use (Snodgrass Rangel, Citation2018). This study aligns with DeMatthews et al. (Citation2023) in that researchers need to investigate ways that principals and principal turnover might be meaningfully different, and what those differences might mean for the factors that predict turnover and the consequences of it.

In Sweden, the turnover rates of school principals are high compared to several other Nordic countries meaning that principals only work for a short time in their schools. In 2013, Swedish principals on average had worked for three years or less at their school (SSI, Citation2019; Thelin, Citation2020). In the Swedish setting novice principals, specifically those born in the 60s and 70s, are found to change schools more frequently than older peers (Thelin, Citation2020). Furthermore, principals in municipal schools are more likely to change positions than principals in independent schools (SNAE, Citation2020). This means, some schools and municipalities in Sweden are far more affected by such mobility than others (Thelin, Citation2020). More precisely, in the academic year 2014/15, on average, only 2 out of 10 principals remained at the same school after five years while 11% remained principals in the same municipality but had changed schools. About 20% had left the principalship altogether after only one year. After three years, roughly 40% had left the profession, and after five years, nearly 60% had quit as a principal. Only one in three remained at all in the school system (SNAE, Citation2020).

In general, central routines and development processes come to a halt when the principal changes. Many principal changes risk causing staff turnover, and in all, principal turnover tends to affect the school and the students in several negative ways. Schools with a lack of well-functioning dialogue with the municipal administrative management often have a high turnover of principals (Jarl et al., Citation2017). However, we do not know much about why principals leave their schools or how the politics built into the school system contributes to shaping principal careers. We do know that principals’ professional agency is found to be in interplay with emotions and is strengthened by participation in professional training programmes. However, this is not the case concerning handling organizational and structural change, being involved in upper management relations (Hökkä et al., Citation2019), a finding that needs further investigation.

This study aims to contribute to our current understanding of turnover related to structures and principal agency in the Swedish context by exploring the early stages of school principals’ careers, their work environments, and their ideas about careers and motives for action. Specifically, this article examines how novice principals engage in and reflect on their careers during their first years as a principal and explore links between novice principals’ actions and (educational) societal structures. In an overarching view, this means relating to how schools and municipalities (or independent school organizers) are linked in the governing of education in Sweden regarding principal careers (cf. Moos et al., Citation2016). Two research questions guide this study: 1) What reflections and deliberations do novice principals engage in and how does this influence their career action-taking? 2) How can the links between novice principals’ actions and (educational) societal structures be described?

The aim and research questions are answered by focusing a specific selection of principals, that is, novice school principals working in Swedish compulsory schools while participating in the mandatory school leader training programme which in this study are viewed as their induction period.

Early careers of novice principals

Research on the early stages of a school principal’s career is in revival and growing, although it is still in its infancy (Kilinc & Gumus, Citation2021; Murphy, Citation2023). Even as some research focuses on how novice principals experience their transition phase to principalship, the research on why some individuals stay on to establish their practice at their school while others leave their posts remains scant (Stevenson & Walker, Citation2006). Being a principal means balancing between personal emotions, ideals, goals, commitments, and external expectations. Further, their position between upper management and personnel is often emotionally tense, embracing emotions of inadequacy, frustration, and exhaustion (Hökkä et al., Citation2019).

The most studied categories on the early stages of a school principal’s career are novice principals’ preparation and developmental pathway, their socialization process, and the challenges they face in terms of demands, expectations, workload, and their role in school improvement (Kilinc & Gumus, Citation2021). Oplatka (Citation2012) concludes that socialization into the school principal’s role means learning the organizational culture of the school, attaining acceptance as a leader, and developing confidence while being inexperienced. This is all important for promoting a positive school culture and encouraging the development of teaching and learning (Arar, Citation2018; O’Doherty & Ovando, Citation2013; Shirrell, Citation2016). Weindling and Dimmock (Citation2006) conclude that novice principals’ pre-established ideas about the principal role often conflict with reality, eventually leading to the development and adjustment of their ideas. However, Shirrell (Citation2016) finds novice principals’ approaches to remain quite consistent.

Understanding how novice principals are influenced by their national context is essential for understanding their agency concerning careers. Garbe and Duberley (Citation2021) highlight career as a useful construct by mediating stability and change and the relationship between individuals and institutions. Moreover, they show power relationships to be involved in processes of change and in forming career paths. That is the intersection of practices and policies – uncovering the politics of everyday decisions. While Shevchuk et al. (Citation2019) find skill mismatch to result in higher turnover and employee departure, White and Knight (Citation2018) find employee mobility to be positive for the individual and that changing jobs boost employee satisfaction. That is, individuals nowadays may be less oriented towards in-school careers and more orientated towards mobility and market individualism (Cappelli, Citation1999). It is also plausible that professionals with strong value commitment experience the impossibility of ‘making a difference’, decide to resign, and move on (Archer, Citation2007).

Sweden is an interesting context for study, where differences in how novice principals understand their school leader education and work have been demonstrated (e.g. Jerdborg, Citation2022). In Sweden, the school system is highly decentralized and market-oriented, but tendencies of re-centralization have been prominent during the last decade (e.g. Lundahl, Citation2002; Nordholm & Andersson, Citation2019). Consequently, more knowledge is needed about novice principals’ institutional and social work environments, as well as ideas about careers and motives for action.

Contextualised background

As described in the introduction, the turnover rates of school principals are high in Sweden and principals only work for a short time in their schools, on average three years or less. Why this is so needs further focus. This study examines how novice principals engage in and reflect on their careers during their first years as a principal and explore links between their actions and how (educational) societal structures impinge upon them, investigating how and why they use their personal powers to act ‘so rather than otherwise’ in practice (cf. Archer, Citation2007, p. 10). Before introducing the theoretical frame and the methodology, the Swedish school system is presented and contextualized as an important background for the study.

The Scandinavian education system is predominantly public, meaning that education is free at all levels and that national steering through laws, regulations and even curriculums is strong. However, since the late 1980s, the Scandinavian education system has undergone major reforms (Ahlström & Aas, Citation2020). In Sweden, this meant that the earlier centrally controlled school sector implemented a new policy course directed towards decentralization and market orientation, which resulted in school principals having greater responsibility and parents being able to choose schools for their children. Independent schools developed alongside the public schools, however financed by the public (Lundahl, Citation2002). Nowadays, there is a tendency towards recentralization in this system (Nordholm et al., Citation2020). Moreover, novice principals in Sweden tend to recognize and support the recentralization logic, question the prevailing market logic, and propose stronger state governance and further reregulation reforms (Nordholm & Andersson, Citation2019). Further, Nordholm et al. (Citation2023) find a battle between state and municipal governance in Sweden, in which municipal school administrations are shown to control school principals’ decision-making capacity.

The majority of compulsory students in Sweden (84%) are yet to attend a municipal school (SNAE, Citation2023). About 3470 principals work as leaders in compulsory schools. These principals are steered by national laws and regulations decided by parliament and evaluated and supported by the government through governmental agencies, even if employed in a municipal or independent school. Some steering is directed directly towards the school principal, who is responsible for the schools’ inner work and organization, while other steering is directed towards the ‘school owner’ in terms of the municipality or independent school provider, as responsible for providing education. In the 290 municipalities, a political school board and their officials, led by a superintendent, direct education, and their school principals. Independent school providers’ organizations are directed by their school boards. There is diversity in how these entities are organized, as some are owned by large corporations and others by small (non-commercial) foundations (Jarl et al., Citation2007; SNAE, Citation2023).

Within this system, municipalities and independent school organizers engage principals in employment. As employers, they need to relate to national requirements regulated in the Education Act (SFS, Citation2010:800), which states that anyone getting hired as a principal must have ‘pedagogical insight through education and work experience’ and that both of these demands must be met at the time of appointment. Educational demand refers to a reasonable university education, including at least 23 credits of pedagogy. Work experience refers to several years of experience in any suitable area and does not need to be from the educational sector (SSI, Citation2014). However, in practice, most new principals have formerly worked as teachers. About 90% of compulsory school principals aged 50–65 and over hold a pedagogical university degree, while this is true among 82% of those aged 30–39 (SNAE, Citation2023). Within one year of gaining their position, principals must begin the mandatory in-service programme, the national principal training programme (NPTP), which engages 20% of principals’ working time during the first three years. The NPTP includes 30 credits divided into three courses: school law, school organization and quality work, and school leadership. The programme has 12 course days each year, carried out in three-day workshop meetings twice each semester in conference hotels. Between attendance at meetings, principals conduct literature reading and educational tasks in their working practice (Jerdborg, Citation2022).

Structure, agency, and career as theoretical frame

In the Swedish setting, Wermke et al. (Citation2022) discuss school principals’ agency in terms of experienced autonomy, highlighting the need for further studies on how structure and agency influence principals. The extent to which an individual is free to embody their values, dispositions, knowledge, and actions, or whether these are shaped by cultural dispositions, norms, experiences, and societal structures, remains an everlasting concern (e.g. Archer, Citation2003). Theories of structure and agency promote understanding of how individuals make sense of and take actions out of their lives. However, structure and agency have been thought of and framed in different ways (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013).

Giddens (Citation1984) means that agentic action is depending upon an individual capacity to make a difference in a course of events. Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003), taking a position in critical realism, criticized Giddens way of conceptualizing agency, and put to the fore an analytical distinction between the social and the individual to enable addressing the relationship between the individual and her circumstances. In Archer’s (Citation2007) definition, reflexivity entails considering oneself in relation to a social context, making sense of circumstances, and attempting to navigate one’s way. Reflexivity mediates between social context, structure, and personal agency. Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003) takes an interest in how structures are reproduced or changed by the acting of agents through the morphogenic cycle. However, Archer’s (Citation2003) typology of reflexive types has been criticized as static, concurring with other studies (e.g. Dyke et al., Citation2012). To this, Archer (Citation2007) agrees, redefining ‘contextual continuity’ as an active concept shaped by the individual’s awareness to fit their current position in society.

In Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998) work, agency is further developed and reconceptualized as a temporal process embedded in social engagement. They analytically separate the temporal elements of past, current, and future. This makes it possible to make a distinction between reflexive/iterative forms of agency, practical/evaluative agency, and projective agency. Ståhlkrantz (Citation2022), using Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998) framework for investigating the work of Swedish principals, show that in relation to a standards-based curriculum, principals’ agency still differs, and their agency is in practice constrained by structures in terms of cultural norms influenced by political agendas. Further, other researchers highlighted a need for constructs to specifically address professional agency connected to subjects’ autonomy and self-fulfilment, promotion of change, innovative work behaviour and resisting structural power but also to critics, struggle and individuals leaving their work organizations (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013; Messmann & Mulder, Citation2017). Also, leaders’ emotion in relation to professional agency has been put forward as important (e.g. Hökkä et al., Citation2019). Moreover, from a sociocultural position, Billett (Citation2006) connects the relations between the individual and the social (cf. Archer, Citation2000; Bhaskar, Citation2016) and individual development across life history. Within such a framing, agency is defined as the ways in which individuals construct their own life course through their choices and actions within their opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstance (e.g. Ecclestone, Citation2007).

Novice principals are found to experience strong emotions and tension (Bolívar & Moreno, Citation2006; Spillane et al., Citation2015). The emotional dimension of a principal’s work has been considered a composite of professional, situated, and personal components (Crow et al., Citation2017), affecting but not determining agency because they are mediated by vocational aspects, values, and moral purposes (Day & Leithwood, Citation2007). Within this frame, the professional dimension reflects what a good principal ‘is’ in terms of ideals (open to long-term policy and social trends). Competing elements include changing policies, continuing professional development, workloads, roles, and responsibilities. The personal dimension is located in life outside work, linked to family and social roles, as well as their feedback, while the situated or socially located dimension occurs at the local school, affected by local conditions, teachers, students, and demographics (Crow et al., Citation2017). Compulsory school principals in Sweden score surprisingly low on the situated socially located dimension, failing to pay attention to the local school (Nordholm et al., Citation2020). This is surprising in light of far-reaching decentralization in Sweden, where municipalities since the late 1980s are responsible for their schools because of their expected knowledge of and interest in local matters (Lundahl, Citation2002). Brewer et al. (Citation2020) focus particularly on how agency is linked with context-specific leadership. They found that school leaders through their agency can rearrange, rephrase, and redevelop elements in context. However, this requires that the principal has high levels of context specific literacy, learned in social practice and in context over time.

Overall, the multidisciplinary concept of agency has become widely used in educational studies, for example through addressing professional learning (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). Moreover, career researchers argue that agency and power dynamics in organizational and institutional settings can be explored through the analytical linking of creativity with constraint (Tomlinson et al., Citation2013). An important area of discussion in research has concerned individual agency within social and economic societal structures (Hitlin & Elder, Citation2007). However, as Tomlinson et al. (Citation2013) argue, it is important to keep the analytical distinction from Archer’s (Citation2000, Citation2003) work between structure and agency. This is because empirical research shows that structures are not merely individuals’ internal norms but also something external that individuals need to confront and grapple with through reflexivity and action strategies, that is for example, to overcome biased opportunity structures with regard to careers.

In this study, novice principals’ actions are investigated considering the structural properties of schools, local educational authorities (LEAs), and the national educational system, as principals’ agentic actions cannot be explained in simple terms of personal resources (cf. Bhaskar, Citation2016). Archer (Citation2000) indicates that agents and structures have different powers and properties, as they operate in different realms of social reality, being temporarily separate. In this study, the issue of ‘types’ is approached empirically. In Archer’s (Citation1995) view, structure precedes actions that (eventually) change them. Underlying structures and mechanisms operate in the strata of ‘deep’ reality, while novice principals operate in the strata of the actual. This study consequently takes an interest in how structures are engaged in by novice principals, as enablement or constraint, influencing their career action-taking through reflection and deliberation. Thus, the human scope for action is viewed as conditioned by diverse social and cultural structures, activated into powers by shaping projects (Archer, Citation1995, Citation2007). Only when there is congruence (activating structural enablement) or incongruence (activating structural constraint) between the social property and the person’s project will the social property structure be activated (Archer, Citation2007, p. 12). Hence, the social or cultural structures activated by novice principals is an important empirical question for investigation in this study while exploring the links between the novice principals’ actions and educational societal structures, being the central conflation of analytical dualism (Archer, Citation2000).

Further, Archer (Citation2003) identifies three distinct types of reflexivity – communicative, autonomous, and meta-reflectivity – each affecting how an individual perceives their job. Both autonomous reflexives and meta-reflexives seek to translate their concerns into their occupations; however, whereas autonomous reflexives invest in skills and rapid promotion, meta-reflexives invest through value commitment. By contrast, for communicative reflexives, a good job enjoys respect in the natal community (Archer, Citation2003, p. 301). Individuals form projects to realize their values, reflecting upon their social situations and concerns (Archer, Citation2003). Deliberation includes prioritizing, accommodating, and subordinating concerns together, while dedication focuses on realizing projects, eventually leading to the establishment of a sustainable modus vivendi. In this sense, internal conversations govern agents’ responses to social stability or change as the missing link between society and the individual – that is, structure and agency. That is, reflection on internal conversations and deliberations is an important aspect this study seeks to discover. Moreover, Archer (Citation2003) finds reflexivity in adopting different ‘stances’ towards the totality of structural powers. The evasive, strategic, or subversive stance is ventured as a generative mechanism at the personal level and constitutes the micro-macro link (Archer, Citation2003, pp. 342–343).

In this article, Archer’s (Citation2000, Citation2003) analytical concepts are complemented by concepts and a definition of professional agency (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). That is, subjects learn through processes of actively creating subjectivity. As professional subjects, they learn not only new skills but also about themselves as emotional subjects, negotiating who they are while prioritizing, considering, and choosing what is important in their lives. Professional subjects have discursive, practical, and embodied relations to their work, and these are temporally constructed within sociocultural and material circumstances, constraining and enabling work (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013).

Research methods and data

This qualitative study focused on novice school principals working in Swedish compulsory schools while participating in the mandatory school leader training programme. As principals in Sweden are obligated to take the three-year NPTP in parallel with their work, starting within one year of gaining their first principal position, this period is viewed as their induction period in this study. Given that all novice principals attend this programme, this was a suitable site for locating the study. Information-oriented sampling combined with a replication strategy was used to sample NPTP-holding universities; three of the six universities at the time hosting the NPTP were selected to collect experiences from principals leading schools located in different regions in Sweden and thus to increase validity by reducing the risk of influence in the study of a particular regional policy or structure. Within each educational setting, one course group was selected, including principals participating in the third year of the NPTP. This study used empirical material from individual interviews with 14 compulsory school principals, whereof two were employed by independent school heads and all others by municipal school heads. These principals were selected within the frame of coming as close to an average compulsory school principal in terms of external factors as possible.

The first interviews were conducted situated at their respective educational sites and the second round of interviews at their schools, yet within the frame of the course. The interviews were semi-structured, lasting 60–100 minutes, digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Open questions were used, allowing the principals to narrate their stories, combined with follow-up questions and close-ended questions, which are important for unravelling processes of reflexivity in terms of thinking, deliberation, and action. Additionally, the principals used Post-it notes to name areas of work and prioritized the identified areas, unfolding their thinking, deliberations, and actions. Field studies were conducted in the principals’ educational and work settings to gain knowledge about their milieus of being and to establish a reasonable, trustful interviewer – interviewee relationship. Notes were taken during fieldwork; however, they were not used specifically in the analysis but served as backdrop information to gain knowledgeable awareness concerning the principals’ life and work situation.

Analyses

The interview transcriptions were analysed using a combined case-oriented and variable-oriented approach (Miles et al., Citation2014). Thus, the two interviews with each principal were coded as a case, while cross-case analyses between principals were conducted to identify underlying structures and mechanisms by comparing patterns of similarities and differences through an analytical method of retroduction (Bhaskar, Citation2016).

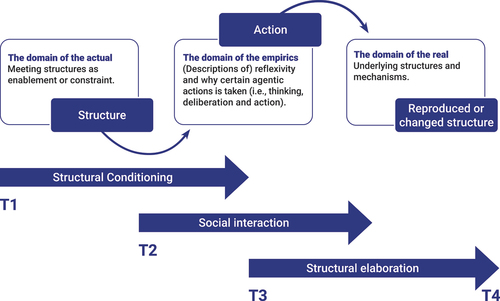

This means, the analysis was related to the theoretical underpinnings of the three strata, as illustrated in . That is, different timepoints analytically represent the relations between structure, agency, and reproduced or changed structure as illustrated in . That is, between timepoints 1 (T1) and 2 (T2), structures influence agents. Between timepoint 2 (T2) and 3 (T3), agency mediates conditioning powers, while timepoint 4 (T4) represents the resulting transformation or reproduction of structure. Timepoint 4 also represents the point where research was undertaken.

In the first stage of analyses, the structural conditioning, what actual social interaction in terms of the principals’ thinking, deliberation, and action-taking – that is, their reflexivity and awareness, and reproduced or changed structure were traced in the empirical data and revealed how certain structures were met by the principals as an enablement or constraint. Moreover, novice principals’ work-related agency is also stratified in terms of the self, the person and the ‘social self’, emerging in the strata of the natural, the practical and the social (Archer, Citation2000). In this study, how the individual principal, as a person, experiences and influences work is operationalized through the practical order as professional agency and career agency. How they experience the self and mediate emotional dimensions of the self is operationalized through the natural order as professional subject agency. How they experience the ‘social self’ through the social order is operationalized in terms of emotional work agency. The focus is set on their reflexive, practical/evaluative and projective negotiations of what they ‘grapple with’ emotionally concerning 1) professional components 2) situated/socially located components and 3) personal components, as described by Crow et al. (Citation2017). The institutionalized structures are seen as sociocultural conditions of their work and social work situation such as material circumstances, physical artefacts, power relations, work cultures, discourses, and subject positions. As middle managers, they are squeezed between superiors and personnel and their respective structures and agency. The conceptual framework is displayed in .

Table 1. Display of the theoretical frame.

The first stage of analyses as described above, focusing on reflexivity, deliberation, and action revealed that structural properties and agentic actions not only could be related to the level of the school and the principal but also needed to be related to structures at the higher level and agentic actions of the superintendent and school board, in terms of conflation (Archer, Citation2000). Thus, at a second stage of analyses, an analytical instrument was constructed based on concepts of the theoretical perspective, functioning as a tool for capturing an analytical process overview, that is, focusing on what emerges in terms of central conflation as agency meets structure, what structural and agentic powers are put in play, and what the results are in terms of reproduction or change at different levels and strata as these mutually influences each other. In the final stage, the principals’ movements, perceived as micro-politics, are linked to the macro-political societal level. Following Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003, Citation2007) in terms of ‘a commodified society’, the principal’s role in a commodified educational context was used as the frame for condensing the results into an analytical generalization using a metaphorical perspective (cf. Morgan, Citation1986). In all, this analytical strategy makes it possible to hypothesize and theorize about casual mechanisms by means of retroduction. This is important because much of what happens is otherwise out of reach of our perceptions and analyses without this analytical richness could well be narrowed and simplistic in relation to a complex social world. Validity is enhanced by methodological pluralism. In this study, both interviews and observations in the educational site as well as in the principal’s workplace combined with interviewing key persons in their schools to gain feedback, were used to test and check the trustworthiness of data, even though not specifically analysed as data for this article. The results were also checked by replicating findings making cross-case comparisons and trying for rival explanations. The rich sets of interviews conducted in various settings also enhance reliability because it gives the opportunity to try and retry the analytical framework in several settings. However, the analytical complexity also set limitations as do the diversity and timeline of interviewees’ interpretations and reflections on their selves.

Results

This section presents the results. First, three sub-sections relating to the first research question and rendering from the first stage of analyses are presented. They illustrate reflections and deliberations principals engage in as professional subjects in socio-cultural conditions by describing their struggling with structural conditions of work. Furthermore, the influence on the principals’ career and actions are illustrated, by showing how they balance between the practical, the natural and the social order to achieve physical well-being, performative achievement, and self-worth. Second, the research question of how the links between the principals’ actions and educational societal structures can be described is approached by describing and illustrating the micro-macro link as a central conflation, using a metaphorical perspective of merchandise stemming from the second stage of analyses.

Novice principals as professional subjects in socio-cultural conditions

While first entering principalship, the respondents had varied ideals regarding the principal professional role and in interviews they described how they viewed what a principal should be: a principal knows everything, works with school development, is part of important forums, makes decisions, wants something with their life compared to teachers, and administers, organizes, and leads teachers. Further, various professional concerns, such as beliefs in making use of gained professional skills, were part of why they applied for a principal appointment in the first place. Moreover, some respondents had situated considerations, wanting to help out in their specific school or community. Others wanted to reach a particular status, earn a higher salary, or realize a professional identity goal. This means, upon entering principalship, as novices they grapple with making sense of themselves as professional subjects and finding a professional identity as a principal. In the following quote, Ellen and Jessica describe their struggles as new principals, each situated in a small school with a certain context:

I became the principal of a small school. There was no trust in management but great suspicion. We had rather low goal achievement. The students and their guardians ruled the school informally. They thought it was cosy, regardless of the curriculum. But I couldn’t close my eyes to what I saw. I want all students to get through the school system, realize their dreams, and have those opportunities. To turn this school into an environment in accordance with the school law and curriculum, I couldn’t do it; it was better for me to change schools. (Ellen)

I think it’s really important that the teachers feel like part of the whole community, meeting those outside the school and gaining input from other businesses. In my opinion, this is connected with the mindset of wanting to be part of something more than just the school. (Jessica)

Intertwined professional and situated components of the emotional dimension of work mediate through their professional identity and the socio-cultural conditions of work, in terms of work cultures and subject positions, shapes structures. Jessica continued her struggle to lead teachers with her concerns in focus, acting out of professional agency, while Ellen decided to give up on her school, taking on another one instead, which rather could be termed an act of career agency. In essence, the emotional dimensions of work can be the reason for principals to stay on or leave their schools.

Struggling with structural conditions of work

The respondents confirmed they were struggling with structural conditions in which they operated, here described as power relations and subject positions, material circumstances and physical artefacts, work cultures and discourses. The quotes illustrate how career outcomes are not necessarily the result of an individual principal’s choice but instead reflect structures of opportunity. How overarching structures are experienced by respondents is visualized in .

Table 2. Structures experienced as enabling and constraining.

Seeking to establish their careers as principals, the respondents were affected by structures in terms of concerns of their superintendents or school boards. These concerns appear in the form of power-relations with superiors and possible positionings of their professional subjects. Lisa described entering the principalship through a position as assistant principal in junior high school, which she was quite comfortable with (i.e. years 7–9), with the intention to learn the new role with time and support. However, instead, she was thrown into a forced tornado of new responsibilities in terms of schools and school forms in new contexts:

I became a team leader and first teacher, and I started lecturing for an IT company. I felt this was too much and that I needed to choose a path and thought that I might try an assignment as an assistant principal. At the time, I thought I would need to apply for quite a few positions before getting an interview. So, I applied at two schools in the municipality. I got a job right away at one of these schools. I became assistant principal at a 7–9 school and managed to stay there for a year. Then, I was asked by the superintendent to step in as deputy principal at two schools that were going to be without a principal because their principal was moved to another assignment. I had to think a lot because I had only been assistant principal for a year. But I decided to accept and begin at the schools that I work at now, two F–6 schools. (Lisa)

Was this a fully voluntary process? Well, formally, yes. But socially, no. She felt that she had to say yes to play her hand well. This means, instead of developing professional agency in her new role as assistant principal, she reluctantly starts to develop a strategic career agency concerning the power-relations in her municipality. However, it was not long before there was a change in superintendents:

Now we have a new superintendent and various gaps in the municipal organisation that need to be filled. I have been asked to take on a new assignment. On Monday, I will begin as the principal at a large F–9 school. (Lisa)

Meeting up with Lisa a few months later at her new F–9 school, she was exhausted after all of her school changes while trying to learn her new role:

In the past, I have been good at keeping up to date. Now, I haven’t been as active. I haven’t really been able to. I have been given an extended mission and have had to jump in as principal at a third school for a period, and new things have sort of come up all the time. I haven’t really had the time or energy for it. Maybe it’s some kind of professional slump. […] And then I think I sort of turn my gaze inward rather than taking in new impressions. (Lisa)

Thus, in between her changing schools, Lisa had to run a third school. In this case, career agency seem to inhibit both the possibility to develop professional agency and care for socially situated concerns in a specific school.

Material circumstances and physical artefacts are other socio-cultural conditions affecting the work of our respondents. Principal Helena was really committed to her school, where she had worked for many years as a teacher, assisting her principal. Then, she became the deputy principal and started in the NPTP. After comparing the conditions of her assignment with her peers in the NPTP, she discovered a lack of supportive material circumstances and work conditions. Around the same time, her deputy position was to be announced as a vacancy for permanent employment, and she was told by superiors to apply:

This summer, I would need to apply for the position where I am the deputy principal. It is a full-time position with fifty percent teaching in service. Well, I applied for it, but reflection has been aroused on my part because I will not be valued like the other principals in this municipality working as a teacher 50 percent as well. (Helena)

Helena started a dialogue with her superintendent, suggesting how to better structure her assignment. However, she met full resistance:

I have talked about this with my boss, but there was no possibility for a full-time position as principal for me in the municipality. (Helena)

Helena described how confronting these circumstances which she experienced as constraints made her leave her school and municipality for another after trying to find any enablement:

I have had a dialogue with my boss the whole time, but he claimed that I shouldn’t be valued like the other principals. By that, I mean that I can happily apply for a full-time position elsewhere, to avoid the split position. That’s why I chose the assignment in a neighbouring municipality. (Helena)

Thus, in confronting what she experienced as constraints, Helena still groped to find any enablement. Finally, she found the physical artefact in terms of her application as the enablement she needed:

I hadn’t planned to apply for any other principal position, but as I had to make that application, I had everything like my CV and cover letter well prepared. So, when a principal position in my neighbouring municipality appeared on social media, I began to think, and I sent my application. I was called for an interview and selected out of 18, and after the interview, I became their first choice. (Helena)

The quotes illustrate how Helena develops career agency in her meeting with peers in the NPTP, becoming aware of the diversity of material circumstances in play. Nevertheless, her professional self mediates, and modulates emotional dimensions, as her feeling of a need to be valued professionally is central to her story. Furthermore, available principal positions in nearby municipalities provide circumstances of competition in the principal labour market to take advantage of.

Showing how the novice principals modulate between components of emotional work agency, the quotes illustrate their considerations while confronting structures such as discourses of, and actual work cultures. One example is Peter:

I was working as an assistant principal in another municipality when I was headhunted for this position and could not refuse. I’ve previously worked for the superintendent who hired me. The assignment embraces two schools that are in great need of change. I had the opportunity to handpick the management team I wanted to bring. It’s not every day that you get that opportunity. (Peter)

The quote above illustrates how principals are affected by the concerns of superintendents or school boards. Moreover, as our respondents confirm being in the arena of appearing as the solution for superiors’ concerns, both current and past work cultures, work relations and discourses come into play when explaining why taking advantage of this situation. Thus, circumstances of competition in the principal labour market are used by superintendents as well as principals, meaning a sociocultural condition of work that affect schools strongly. Even principals who reported a strong commitment and sense of responsibility in favour of a specific school exhibited this prioritization, finding it hard to turn down offers and consequently, they were downplaying their caring for their current school. Only those working in independent schools managed to stick to situated concerns:

When I listen to my colleagues in the NPTP, I don’t want to be in any other organisation as a principal. I feel that principals get ignored. But I always have backing. It’s not like anyone ignores me. Absolutely not! I always feel that I have full support. […] So, if I remain as principal, this is where I am to stay. (Sarah)

Balancing between the practical, the natural and the social order

The statistics of principals in Sweden show that many principals leave the profession altogether only after a few years. Only a few go back to teaching, meaning many principals leave for a sector other than the educational sector. In line with this, the results of this study showed that the majority of principals felt they were done with being a teacher and could not even imagine going back to teaching for a living:

Going back to full-life teaching, I don’t think I will do. That time is over. (Peter)

I think it would be very difficult to go back to teaching; one would have to be critical of so much. You have acquired another insight somewhere. (Angelica)

Instead, the novice principals reflected on whether some other branches would be just as good:

If I think about my own future, it’s probably some other line of business. (Jessica)

It’s not obvious that I would be the principal of another school. It’s more likely that I would think, Should I be a principal? Should I work in a school at all? (Henrik)

Further, it was clear that before leaving principalship, they struggled to finish the NPTP, as this seemed to be an important merit:

I want above all to finish my education [i.e. NPTP]. It would feel tragic to start another job in another business sector and not finish it. (Henrik)

However, some of the principals imagined a future career within the school sector:

I have a secret dream of becoming a secondary school principal. I’ve been in compulsory school all my professional life. Compulsory school is really tough. (Sofia)

I think that I will remain in the principal’s role for at least ten years from now. Then, I will move on and take another principal role elsewhere. Then I might go back to working at an administrative level as a compulsory school head or superintendent. (Peter)

Thus, as they pendulated between personal, professional, and situated concerns, imagining their projective future careers, diverse concerns came into play. Furthermore, the stance they take might not be crucial in the Swedish ad hoc system. As one of the principals stated, in that case, what will make him take the next step:

You never know; it could be coincidence. (Henrik)

The novice principals developed strategies to manage and respond to the work conditions they faced. Some used the evasive strategy of ‘go with the flow and never say no’ meaning viewing all socio-cultural conditions as opportunities, illustrating career agency to be stronger than professional agency. However, taking an evasive stance might be strategic, as it showed to promote the personal and professional concerns of the principals. However, it also entails having to take on takedowns and unwanted challenges, such as a diverse change of responsibilities and schools, steered by a higher level and mediated through the superintendent. Relating to structures there seemed to be a commitment to a discourse of ‘the generative principal’ and ’progression through relocation and additional responsibilities’ as well as a shaping and maintaining of profitable relations with superiors.

Others used a subversive strategy of ‘creating favourable projects and dare to try’ meaning taking more of an active stance towards structures, illustrating grappling with shaping professional agency. However, not complying might not be strategic regarding internal career opportunities as it entails making decisions in favour of self-respect, such as changing employers. Thus, one is ‘forced’ into a subversive stance-taking as developing professional agency and identity. Relating to structures there seemed to be a commitment to a discourse of ‘searching for more suitable conditions through relocation’. That is, either strategy promotes re-location of novice principals.

The micro-macro link: the principal’s role in a commodified educational context

The extensive movements among the interviewees during their first years as principals illustrated by the results included movements between schools, as well as shifts in the kinds and number of responsibilities the principals handled. These may involve, for example, taking on more schools or starting up a new school form (such as adding a primary school to a middle school). Some principals shifted from being assistant principals to becoming principals, often meaning changing schools and municipalities. A few principals shifted responsibilities within the school, taking on new parts of work, such as shifting responsibilities with a peer (meaning their employees shift manager, even as the manager is still there). Only one out of 14 principals stayed in their workplace and had quite the same responsibilities during their first three years. These continually ongoing movements were related to the fact that these same individuals, before taking on principalship, had worked for many years, often 15–20 years, in one and the same school. This reveals that ‘the moving around’ can hardly be explained by the individual types. A detailed summary of the pathways is shown in .

Table 3. Pathway as novice principal, the first years of duty (until last semester in the NPTP).

Only the two principals working at independent schools highlighted situated components as emotionally important. Moreover, those principals also highlighted structures in the form of work cultures, material circumstances and power relations as being mostly supportive, promoting their professional agency. Consequently, those principals were committed to staying in their respective schools for the long term. They would rather leave the educational sector all together, than change schools. The other principals highlighted professional and personal components as emotionally important. They highlighted grappling with structures in terms of material circumstances, power relations, subject positions, discourses, and work cultures. However, these were not directed towards supporting novice principals to develop professional situated agency. The conditions in terms of discourse, positions and power relations were rather promoting career agency to change schools by offering new opportunities and simultaneously providing difficulties for novice principals to act out of commitment to a specific school. Furthermore, this means that either stance one takes, evasive or subversive, it can bring both active and passive elements because there is no obvious strategic stance that brings active elements to take.

To sum up, it seems that school principals have become ‘wear-and-tear items’ in an educational marketplace. That is, their career movements become micro-politics linked to the macro-political societal level. As such, their movements are influenced by a mix of structural powers of recentralization and discourses of market orientation. Recentralization of the school sector is prominent in Sweden during the last decade with a number of national regulation programmes implemented by state-regulated school agencies. Making the NPTP mandatory for new principals is only one example. This orientation intertwines with the market-oriented school system in Sweden and this mix is experienced as confusing by novice principals in the NPTP (e.g. Nordholm & Andersson, Citation2019). The career movements of our respondents can be categorized into two separate categories: (a) the subversive principals decide to move on and thus advertise themselves at a cost in the educational marketplace, and (b) the evasive principals are treated as an item, moved around, and sorted by their superintendents. The superintendent, as the head of schools in a municipality, thus has (non-intentionally) come to gain the role of merchandiser, buying, and selling on the market and remaining cognizant of the buy and sell rates for principals. They also maintain warehouses and act as retailers in the market-oriented and competitive school system. That means both principals and superintendents need to play their hand well to gain from, or at least not suffer from supply and demand effects in this market. Even the state has come to be an actor in this market, surprisingly, they are taking the role of regulating the market in terms of the products, for example, bettering products by providing mandatory principal education. This is displayed in .

Table 4. Educational sector as marketplace and the principal as wear-and-tear item.

Returning to Archer (Citation2000, Citation2003) and the morphogenic cycle, what structures are reproduced by the acting of agents in this system and what kind of social change is produced? This is presented in .

Table 5. Links between principals and educational societal structures.

Concluding discussion

The result of this study recognizes a constant movement among novice principals’ work location, work responsibilities, and their positioning in their current status, meaning that social structures most often impede novice principals’ attempts to develop professional agency in the socially situated dimension at a specific school. Instead of developing a professional agency in their new role as principal as could be expected, they (somewhat reluctantly) start to develop a strategic career agency. This was specifically apparent in municipal organizations. Novice principals were affected by structures such as material circumstances, physical artefacts, power relations, work cultures, discourses, and subject positions, often mediated through the concerns of their superintendents. Encountering such structures as constraints made novice principals leave their schools and municipalities for another, thus subordinating their situated and social dimensions themselves. Turnover among novice principals is reflected in the enablement that made novice principals leave their school, alternatively, change, or take on more responsibilities within their current assignment because their superintendent changed their duty, thus subordinating their situated and social dimension. Consequently, regardless of how the structures were confronted, the results remained – a constant movement among novice principals, who moved between schools, municipalities, responsibilities, and roles during their first years of duty, meaning career outcomes are not necessarily the result of an individual principal’s choice but instead reflect structures of opportunity and constraint.

This important outcome affects the novice principals’ process of learning throughout their induction phase. First, it can be contested whether they gained from the NPTP in the absence of stability in their assignments to allow linking with education. Second, in regard to the social environments in compulsory schools in Sweden, it can be contested whether novice principals, during these circumstances, gain any socialization in the role, develop any context-specific literacy, learn the organizational culture of a school, attain acceptance as a leader, or develop some sort of confidence (Brewer et al., Citation2020; Oplatka, Citation2012). Third, the results highlight the effects of these outcomes for compulsory schools: In the face of a constant change of principal at the school, who is to promote a positive school culture and enhance school capacity? (e.g. Arar, Citation2018). This finding is specifically interesting in light of decentralization, as the main argument for having municipalities as heads of schools is their engagement in and knowledge about the situated social circumstances (cf. Lundahl, Citation2002). This finding needs further exploration at the municipal level to investigate what has disorientated them from their main responsibility as school heads (SSI, Citation2019). In this study, the two independent school organizers took better care of their local responsibilities. One possible explanation for further investigation is whether the market-oriented school system, oriented towards students and parents, has been exploited by leaders and administrators of municipal schools, causing them to move between municipalities to gain personal benefits but lose their engagement with the local community, or if the development of career agency is simply the outcome of competitive educational environments.

The results cannot be understood solely in terms of certain ‘types’ or stances (Archer, Citation2003). Rather, they must be understood in terms of formal and informal structures, affecting novice principals, compulsory schools but also superintendents. Few independent organizers were represented; however, these provided slightly more supportive structures for the situated dimension. This supports the interpretation that there is a crucial interplay between how structural and cultural powers impinge upon agents (i.e. novice principals) and how they act (Archer, Citation2007). If processes in which novice principals’ pre-established ideas about the principal role conflict with reality lead to sense-making and development (Weindling & Dimmock Citation2006), there needs to be some stability in a principal’s work situation. If novice principals tend to remain consistent in their approaches (Shirrell, Citation2016), developing professionally might take time. However, if the principals meet new schools or responsibilities every new year, this process starts all over before any real development can take place.

Previous research has focused on novice principals’ developmental pathways (e.g. Murphy, Citation2023). This study complements and broadens previous themes by including novice principals’ turnover related to structures and principal agency in the Swedish context. The results illuminate earlier findings on the tendency among novice principals to change schools, as well as why some schools and municipalities might be more affected (Thelin, Citation2020; SSI, Citation2019). This study used data from principals in three different educational (i.e. regional) settings. The one difference that can be noted is that not all regions seem to have assistant principals in their workforce, meaning that the opportunities to be introduced to principalship differ and that the step from teacher to principal is taller in some regions. Moreover, the results nuanced the former finding that compulsory school principals do not pay attention to the situated context (Nordholm et al., Citation2020). Regarding research, the need to compare national contexts is prominent since processes of turnover well can be shaped by national societal structures (Archer, Citation2003; Stevenson & Walker, Citation2006). Many countries are struggling with a lack of induction for novice principals, resulting in turnover and burnout (Bush & Oduro, Citation2006; DeMatthews et al., Citation2023).

Archer (Citation2007) argues that people with strong value commitment might experience education professions as commodified, resign, and move on. This risk seems highly relevant in the Swedish context, as the principals predicted that they would change sectors rather than stay in education if leaving principalship. Our findings align with those of Archer (Citation2007) and Cappelli (Citation1999), in that risk is linked to changed societal structures. This study consequently proposes that policymakers, municipalities, school boards, and superintendents sincerely and critically examine their shaping of structures and their acting, to introduce more situated support for local schools. They need to support novice principals to remain at their schools for longer periods, at least as long as it takes to finish their induction phase and accomplish their mandatory studies within the NPTP.

Explicating the links between novice principals’ actions and educational societal structures metaphorically as the treatment of principals as wear-and-tear items shows how structures consolidating this are making the principal a passive agent. Even the seemingly active act of shifting employers (cf. White & Knight, Citation2018) positions the principal as an item in this educational market. Taking an active stance, they would be players instead of items, and the schools would be strategic playgrounds. Thus, the state could regulate the market in terms of open windows for buying and selling. In this study, some schools were merely treated as 24-hour open stores and principals as sweaters in different colours by their superintendents. Sometimes they were stacked in colour themes and sometimes spread all over the store. The results align with Wermke et al. (Citation2022), who show that municipal administration controls school principals’ decision-making space and reveal a need to study how municipalities and superintendents support situated local school contexts (cf. SSI, Citation2019). Do they support stable leadership with an interest in the local context, or do their interests mainly concern solving ‘their puzzle’, forgetting about the local life and development in schools? The School Inspectorate’s investigations reveal far more principal changes than municipalities report because many changes ‘do not count’ in their view (SSI, Citation2019, p. 11). Such changes are also revealed in this study and in all this was illustrated as a problematic and constant movement among principals in (some) Swedish compulsory schools, showing principal turnover might be far more problematic than hitherto feared. The findings of the study thus help to advance our understanding of possible obstacles to educational change that might occur in diverse national contexts and direct future research interest into these matters.

This study should be complemented by studies using triangulation, as one limitation is only focusing on principals. Triangulation could bring important perspectives by including superintendents. How they meet structures and what agency they conduct should extend our knowledge on the premises for novice principals’ induction phase. Yet, this study strengthens the theoretical foundation of the literature on novice principals (Kilinc & Gumus, Citation2021) by introducing a framework for investigating societal structure in relation to novice principals’ agentic actions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahlström, B., & Aas, M. (2020). Leadership in low- and underperforming schools–two contrasting Scandinavian cases. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International Journal of Leadership in Education (pp. 1–21). https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1849810

- Arar, K. (2018). How novice principals face the challenges of principalship in the Arab Education System in Israel. Journal of Career Development, 45(6), 580–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317726392

- Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2000). Being human: The problem of agency. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency, and the internal conversation. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press.

- Bhaskar, R. (2016). Enlightened common sense. Ontological explorations. Routledge.

- Billett, S. (2006). Work, subjectivity and learning. In B. Stephen, F. Tara, & S. Margaret (Eds.), Work, subjectivity and learning (pp. 1–20). Springer Netherlands.

- Bolívar, A., & Moreno, J. M. (2006). Between transaction and transformation: The role of school principals as education leaders in Spain. Journal of Educational Change, 7(1–2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0010-7

- Brewer, C., Okilwa, N., & Duarte, B. (2020). Context and agency in educational leadership: Framework for study. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(3), 330–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1529824

- Bush, T., & Oduro, G. K. T. (2006). New principals in Africa: Preparation, induction and practice. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610676587

- Cappelli, P. (1999). The new deal at work: Managing the market-driven workforce. Harvard University Press.

- Crow, G., Day, C., & Møller, J. (2017). Framing research on school Principals’ identities. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(3), 265–277.

- Day, C., & Leithwood, K. (2007). Successful Principal leadership in times of change: An international perspective. Studies in Educational Leadership (Vol. 5) Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5516-1

- DeMatthews, D. E., Reyes, P., Carrola, P., Edwards, W., & James, L. (2023). Novice Principal burnout: Exploring secondary trauma, working conditions, and coping strategies in an urban district. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 22(1), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.1917624

- Dyke, M., Johnston, B., & Fuller, A. (2012). Approaches to reflexivity: Navigating educational and career pathways. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33(6), 831–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.686895

- Ecclestone, K. (2007). An identity crisis? The importance of understanding agency and identity in adults’ learning. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2007.11661544

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

- Garbe, E., & Duberley, J. (2021). How careers change: Understanding the role of structure and agency in career change. The case of the humanitarian sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(11), 2468–2492. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1588345

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. University of California Press.

- Gronn, P., & Rawlings-Sanaei, F. (2003). Principal recruitment in a climate of leadership disengagement. Australian Journal of Education, 47(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410304700206

- Hitlin, S., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00303.x

- Hökkä, P., Vähäsantanen, K., Paloniemi, S., Herranen, S., & Eteläpelto, A. (2019). Emotions in leaders’ enactment of professional agency. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(2), 143–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-07-2018-0086

- Jarl, M., Blossing, U., & Andersson, K. (2017). Att organisera för skolframgång: strategier för en likvärdig skola. Natur & Kultur.

- Jarl, M., Kjellgren, H., & Quennerstedt, A. (2007). Förändringar i skolans organisation och styrning. In J. Pierre (Ed.), The school as a political organisation (pp. 23–47). Gleerups.

- Jerdborg, S. (2022). Educating school leaders: Engaging in diverse orientations to leadership practice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(2), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1770867

- Jerdborg, S. (2023). School Principal re-positioning in a system of professional relations: The case of newly appointed principals in Sweden. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 55(4), 456–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2023.2217086

- Kilinc, A. C., & Gumus, S. (2021). What do we know about Novice School Principals? A systematic review of existing international literature. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 49(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219898483

- Lundahl, L. (2002). Sweden: Decentralization, deregulation, quasi-markets - and then what? Journal of Education Policy, 17(6), 687–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000032328

- Messmann, G., & Mulder, R. H. (2017). Proactive employees: The relationship between work-related reflection and innovative work behaviour. In G. Michael & P. Susanna (Eds.), Agency at work (Vol. 20, pp. 141–159). Professional and Practice-based Learning. Springer International Publishing

- Miles, M. B., Michael Huberman, A., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (Eds.). (2016). Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain. Springer International Publishing.

- Morgan, G. (1986). Images of organization. SAGE.

- Murphy, G. (2023). Leadership preparation, career pathways and the policy context: Irish novice principals’ perceptions of their experiences. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 51(1), 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220968169

- Nordholm, D., & Andersson, K. (2019). Newly appointed principals’ descriptions of a decentralised and marked adopted school system: An institutional logics perspective. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 47(4), 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217751075

- Nordholm, D., Arnqvist, A., & Nihlfors, E. (2020). Principals’ emotional identity - the Swedish case. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1716326

- Nordholm, D., Wermke, W., & Jarl, M. (2023). In the eye of the storm? Mapping out a story of principals’ decision-making in an era of decentralisation and re-centralisation. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 55(4), 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2104823

- O’Doherty, A., & Ovando, M. N. (2013). Leading learning: First-year principals’ reflections on instructional leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 23(3), 533–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461302300305

- Oplatka, I. (2012). Towards a conceptualization of the early career stage of principalship: Current research, idiosyncrasies and future directions. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 15(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2011.640943

- Seashore Louis, K., Dretzke, B., & Wahlstrom, K. (2010). How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a National US Survey. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.486586

- SFS. (2010). Skollag [Education Act] 800. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

- Shevchuk, A., Strebkov, D., & Davis, S. N. (2019). Skill mismatch and work-life conflict: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Education & Work, 32(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2019.1616281

- Shirrell, M. (2016). New principals, accountability, and commitment in low-performing schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(5), 558–574. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2015-0069

- SNAE (Swedish National Agency for Education). (2020). PM: Omsättning bland rektorer i grund- och gymnasieskolan. SNAE.

- SNAE (Swedish National Agency for Education). (2023). Elever och skolenheter i Grundskolan. Beskrivande statistik. Läsåret 2022/23. Diarienummer: 2022:2513.

- Snodgrass Rangel, V. (2018). A review of the literature on Principal turnover. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 87–124. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317743197

- Spillane, J. P., Harris, A., Jones, M., & Mertz, K. (2015). Opportunities and challenges for taking a distributed perspective: Novice School Principals’ emerging sense of their new position. British Educational Research Journal, 41(6), 1068–1085. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3166

- SSI (Swedish Schools Inspectorate). (2014). Pedagogisk insikt genom utbildning och erfarenhet – behörighetskrav för rektorer och förskolechefer (Bedömnings-PM 2014-04-02).

- SSI (Swedish Schools Inspectorate). (2019). Huvudmannens arbete för kontinuitet på skolor med manga rektorsbyten–Utan spaning ingen aning (Tematisk validitetsgranskning 2019. Dnr: 400–2018:7409). https://skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/02-beslut-rapporter-stat/granskningsrapporter/tkg/2019/huvudmannen-och-rektorsbyten/overgripande-rapport-rektors-rorlighet-slutversion_tillg_webb.pdf

- Ståhlkrantz, K. (2022). Principal agency. In N. Wahlström (Ed.), Equity, teaching practice and the Curriculum (pp. 90–104). Routledge.

- Stevenson, H., & Walker, A. (2006). Moving towards, into and through principalship: Developing a framework for researching the career trajectories of school leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610676604

- Thelin, K. (2020). Principal turnover: When is it a problem and for whom? Mapping out variations within the Swedish case. Research in Educational Administration & Leadership, 5(2), 417–452.

- Tomlinson, J., Muzio, D., Sommerlad, H., Webley, L., & Duff, L. (2013). Structure, agency and career strategies of white women and black and minority ethnic individuals in the legal profession. Human Relations, 66(2), 245–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712460556

- Valle, R., & Lillejord, S. (2023). A new regime of understanding. School leadership in Norwegian education policy (1990–2017). Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 9(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2023.2208258

- Walker, A., Hallinger, P., & Qian, H. (2007). Leadership development for school effectiveness and improvement in East Asia In T. Townsend (Ed.), International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement (pp. 659–678). Springer International Handbooks of Education.

- Weindling, D., Dimmock, C., & Walker, A. (2006). Sitting in the “Hot Seat”: New Headteachers in the UK. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(4), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610674949

- Wermke, W., Jarl, M., Sophie Prøitz, T., & Nordholm, D. (2022). Comparing Principal autonomy in time and space: Modelling school leaders’ decision making and control. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(6), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2022.2127124

- White, M., & Knight, G. (2018). Training, job mobility and employee satisfaction. Journal of Education & Work, 31(5–6), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2018.1513639