Abstract

Like many parts of the world, Aotearoa New Zealand’s waterways are under immense pressure from anthropogenic impacts that will be amplified by the effects of climate change. After decades of rising public concern, progress had been made on freshwater policy for the protection and restoration of the country’s waterbodies. However, a new Government, elected at the end of 2023 threatens to undo that progress, and implement economic policies that will worsen the country’s freshwater crisis. This article was prompted by an open letter, signed by 51 freshwater experts and national and regional leaders on freshwater issues, that urged the new Government not to reverse or undermine the progress made. It describes the state of the country’s waterways, provides a brief history of developments for freshwater in Aotearoa New Zealand and highlights the influence of the country’s agricultural sector on its environmental policy.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.Introduction: “Dear Prime Minister, don’t take freshwater policy backwards.”

Successive New Zealand Governments have failed to protect the country’s freshwater. There is ample evidence now of a nationwide freshwater crisis that will be worsened by the effects of climate change. Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) has witnessed the dramatic loss of its freshwater biodiversity (Quinn and Hickey 1990; Weeks et al. 2016; Joy et al. 2019), worsening water quality (Julian et al. 2017; Rogers et al. 2023), as well as increasing risks to people’s health, including the safety of drinking water (Richards et al. 2022; Prickett et al. 2023). The rapid intensification of the country’s agricultural sector, particularly dairy farming, in recent decades has contributed significantly to this decline (Julian et al. 2017). Forestry and horticulture also contribute to pressure on the health of waterways (Julian et al. 2017; Norris et al. 2023) as well as insensitive urban development and chronic underfunding of storm and wastewater systems also jeopardizing the health of waterways (Gadd et al. 2020; Chambers, Wilson, et al. 2022).

Given the severity and complexity of NZ’s freshwater crisis and the fundamental value of water to life (flora and fauna, human health, economy, etc.), waterways need central government-level intervention and oversight, strong legal protection, and political leadership. However, the new Government, elected in October 2023, is intending to weaken existing freshwater protections as well as implement economic policies that will further intensify agricultural land use, prioritise private property right, and undo progress to address the country’s water infrastructure deficit (New Zealand National Party and ACT New Zealand 2023; New Zealand National Party and New Zealand First 2023).

In December 2023, 51 freshwater experts, along with national and regional leaders on freshwater issues and restoration, published an open letter (‘the letter’) to the newly elected Prime Minister Christopher Luxon and his Ministers (Morton 2023) (the full letter and signatories provided as supplementary material). The letter urged the new Government to retain NZ’s national freshwater policy (National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 – NPS-FM 2020), which the country’s regional councils are in the process of implementing. The freshwater experts and leaders warned that the new Government’s proposal to replace the NPS-FM 2020, along with other proposals, will undoubtedly lead to the country’s waterways’ continued decline. The letter was headed “Don’t take freshwater policy backwards,” and opened, “New Zealand’s rivers, lakes and aquifers are in a dire state. If you proceed with your proposals to undo the country’s freshwater policy, they will only get worse” (supplementary material).

This article was prompted by the letter andsection headings in this article are extracted quotes from the letter. In this article, we present a brief background on the state of NZ’s freshwater bodies, provide a brief history of recent Governments’ approaches to freshwater policy and outline progress made. We then present what the new government has proposed and analyse what this means for NZ’s waterways.

As has occurred in Inland Waters previously, with regards to the Bolsonaro administration’s dismantling of Brazil’s environmental protections (Thomaz et al. 2020), we have written this article to bring to the attention of the international community the destructive environmental decisions the new NZ Government is making. We do so because the destruction of the environment in one part of the world is not inconsequential for other places and communities. We also write in the hope that international pressure might play a part in limiting the damage done to NZ’s freshwater policy and its waterways.

“NZ’s rivers, lakes, and aquifers are in a dire state.”

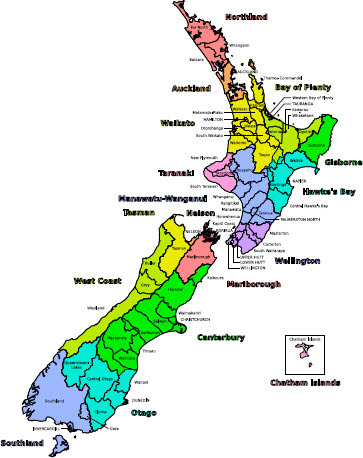

The degradation of NZ’s waterways is widespread. All NZ regions have experienced decline in water quality and the health of freshwater ecosystems, with lowland lakes and rivers tending to be the most severely degraded (Larned et al. 2016). Agricultural land use has been a major contributor to this decline, with almost half of the total length of the country’s waterways running through agricultural land (Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019). Regions where dairy farming has expanded and intensified over the last 30 years have experienced extensive and rapid decline in recent decades (Julian et al. 2017; Dench and Morgan 2021; Ramenzani et al. 2016). These are primarily the regions of Canterbury, Southland, Waikato, Taranaki, and Manawatū () (though intensive dairy operations exist outside these regions too). Horticulture, forestry, and other livestock farming also contribute to pollution of waterways and loss of habitat. Wetlands are still being lost, primarily as a result of being drained for livestock grazing (Denyer and Peters 2020; Burge et al. 2023). Some intensive horticulture operations can have particularly high nitrogen loss to water (Norris et al. 2023). Forestry can be a significant contributor of sediment and nutrients, particularly at the time of harvest (Julian et al. 2017). Impacts of forestry on NZ waterways have been particularly pronounced in the eastern regions of the North Island, especially Gisborne (Ministerial Inquiry into Land Uses in Tairawhiti and Wairoa 2023).

Urban waterways make up <1 percent of the total length of waterways in NZ (Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019). Urban water quality tends to be the poorest and urban waterways are frequently drastically modified habitats (eg piped, straightened, etc.) (Gadd et al. 2020; Chakravarthy et al. 2019). The most recent national survey of the country’s wastewater services reported ∼3,000 wastewater overflows nationally (where untreated sewage spills out of broken pipes or faulty infrastructure) (Water NZ, 2022). A previous year’s survey noted that the problem is likely to be much larger than what is reported due to little regulatory oversight (Water NZ, 2020). Stormwater, the runoff from urban landscapes to local waterbodies, also carries with it heavy metals (eg zinc, copper, lead). These have been found to frequently exceed ecotoxicological thresholds, as defined by Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council, in NZ waterways (Good et al. 2014; Gadd et al. 2020). There is most often no treatment for stormwater in NZ. Insensitive design of urban environments means contaminants are washed from impervious surfaces by higher flows than under natural conditions, though retention ponds are sometimes established to reduce sediment and heavy metal loss to waterways (Good et al. 2014).

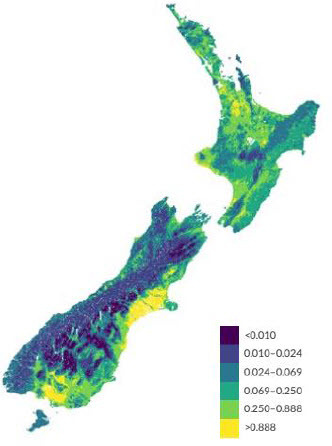

Physiochemical measures of water quality indicate many of the country’s waterbodies are in a poor state, with frequently worsening trends (Whitehead et al. 2022). Eighty-five percent of waterways in pasture catchments now exceed Australasian nitrate guideline thresholds of 0.44 mg/L NO3-N () (Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019). Total nitrogen loss averaged across all waterways is estimated to be 74% above natural loads (159% for nitrate-nitrogen) (Snelder et al. 2018). In some catchments, there has been an estimated 26-fold increase in nitrogen loss to water from anthropogenic activity (Snelder et al. 2018). After normalisation of area, nutrient loads in some of NZ’s farmed catchments now rival some of the world’s most intensively farmed catchments, such as the Mississippi River (USA) and Yellow River (China) (Joy and Canning 2021).

Figure 2: Modelled median concentrations in g/m3, 2013-2017 (CC BY-SA 4.0, Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019)

Researchers estimate 44 percent of lakes nationally are presently eutrophic or higher (Abell et al., 2020). The same study found that under reference conditions ∼10 percent of lakes were estimated to be eutrophic and between 1-3 percent supertrophic, with none estimated to have been hypertrophic. Shallow lakes are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic impacts, and some have likely suffered damage from nutrient enrichment and invasive species that will be very difficult and/or expensive to reverse (Özkundakci and Lehmann 2019. Abell et al. 2020).

As with physiochemical measures, the decline of NZ’s aquatic life also reveals the failure to protect the country’s freshwaters. Nationally, aquatic biodiversity, especially that of native fish, is in sharp decline particularly in highly modified catchments (Weeks et al. 2016; Joy et al. 2019). Three quarters of NZ’s mostly endemic native fish species are listed as threatened or at risk of extinction (Weeks et al. 2016). Threats to native fish species are impacts on water and habitat quality from anthropogenic pressures and barriers to fish passage such as dams and culverts (Joy et al. 2019). The most severe diversity declines are associated with pastoral land use (Joy et al. 2019). The type of pastoral land use also effects the rate of decline, with increased prevalence of dairy farming in a catchment leading to less abundant and diverse fish communities (Ramenzani et al.2016). There is a strong correlation between native freshwater fish decline and freshwater invertebrate communities, measured using the macroinvertebrate community index (MCI). MCI monitoring revealed that, between 2001 and 2020, 56 percent of river monitoring sites were worsening, and just 25 percent improving (Ministry for the Environment 2023). Many of these sites that have been improving are likely to be where point source pollution has been remedied. Earlier studies showed macroinvertebrate communities in many NZ waterways had shifted from being dominated by sensitive ‘clean water’ invertebrates to being dominated by more pollution tolerant species as a result of anthropogenic pressure (Quinn and Hickey 1990).

Additionally, invasive species, such as koi carp (Cyprinus carpio) (Rowe 2007) in lakes and Didymo (Didymosphenia geminata) in streams and rivers (Anderson et al. 2020), put further pressure on NZ’s freshwater ecosystems. For example, two species of introduced invasive Daphnia (D. pulicaria/pulex and D. galeata) have become established in many NZ lakes over the last 20 years, disrupting natural ecosystems and biodiversity (Burns et al. 2024 preprint).

Alongside ecosystem health impacts, the decline of NZ’s freshwater also risks human health. A recent study found nearly 10 percent of 435 groundwater sites sampled nationally had nitrogen concentrations above the 11.3 mg/L human NZ drinking water standard for nitrate-nitrogen (based on the World Health Organisation’s standard) (Rogers et al. 2023). In the same study, 33 percent of over 1000 surface and groundwater sites sampled were found to exceed 5.6 mg/L (a legal trigger point for councils to investigate drinking source water contamination) (Rogers et al. 2023). To put these concentrations into perspective, earlier groundwater surveys estimated nitrate-nitrogen levels in unaffected NZ groundwater (no human influence) to have a median value between 0.3 and 1 mg/L (Daughney and Wall 2007). There is emerging evidence nitrate exposure at levels considerably lower than the drinking water standard increases risk of colorectal cancer, thyroid disease, and neural tube defects (Chambers, Douwes, et al. 2022; Richards et al. 2022). The costs of harm from cancer associated with nitrate in NZ has been estimated at $43 million USD. A recent estimate for a nitrate removal system for one NZ city (pop. ∼400,000) suggested capital costs would be between $347 million NZD and $610 million NZD depending on how much nitrate was to be removed (Birdling 2021).

Additionally, 59 percent of monitored bores contained faecal bacteria (Escherichia coli) concentrations exceeding drinking water standards and 64 percent exhibited increasing trends in E. coli (Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019). Land use type and the intensity of land use has been found to increase the prevalence and diversity of pathogens in waterbodies, including those used for drinking water sources in NZ (Williamson et al. 2011; Phiri et al. 2020; French et al. 2022). Moreover, in 2016, the North Island town of Havelock North experienced the largest campylobacter outbreak ever recorded (Gilpin et al. 2020). Water contaminated with sheep faeces entered a poorly maintained municipal bore, partly due to an inadequate understanding of the connectivity between surface and groundwaters, leading to an estimated six to eight thousand people becoming ill and four deaths (Gilpin et al. 2020). This, as well as the contamination of groundwater nationally, highlights the connectivity of water across the landscape, and that NZ’s freshwaters should be considered a single integrated system rather than discrete disconnected waterbodies.

Freshwater recreational opportunities have also declined with swimming in most rivers in farmed and urban areas in NZ now posing a risk to human health from the ingestion of pathogens (Larned et al. 2016). E. coli is used as an indicator organism for monitoring faecal contamination and inferring pathogenic risk. However, pathogens present in NZ waterways have been identified as a number of bacteria or viruses, including campylobacter, cryptosporidium, and norovirus (Phiri et al. 2020. French et al. 2022). Furthermore, there is evidence of antimicrobial resistance in waterborne diseases present in NZ waterways (Davis et al. 2021; van Hamelsveld et al. 2023) Pathogens can also be transported through the consumption of food harvested from waterbodies (van Hamelsveld et al. 2023). This has particular impact on Māori (Indigenous peoples) as collecting wild foods (mahinga kai) is strongly connected to cultural health and well-being (Tipa 2013). The intensification of agriculture has also led to declines in recreational fisheries (Stewart et al. 2019).

On top of all the indicators of decline, other emerging contaminants like pesticides (including chlorpyrifos and diazinon) and Emerging Organic Contaminants (including bisphenol-A) can be found in surface waters and aquifers (Hageman, et al. 2019; Close et al. 2021).

Crucially, many of the factors contributing to the deterioration of waterways are likely to be amplified by climate change, adding further risk through changes in hydrology and temperature (Ling 2010).

“Collaboration between industry and government was tried and failed … the public has been calling on central government to provide stronger protection for water.”

It is not possible in this article to present a full history of NZ Governments’ approaches to waterbodies, which would require deeper discussion of colonisation (Taylor 2022). There is a far longer history of Māori resistance to government-facilitated environmental destruction that we are unable to cover here. However, we believe a brief history of recent public debate, government initiatives and, particularly, the influence of the agricultural industry provides important context for why new Government’s is seeking to undo progress on protect for freshwater.

Understanding NZ’s approach to freshwater policy requires an understanding of the NZ public’s widespread and active concern for waterways and an understanding of NZ’s agricultural industry. The NZ public, including and especially Māori, are deeply connected to their waterways. For Māori, rivers are ancestors and form a central part of one’s identity (Stewart-Harawira 2020). The wider NZ public also feels strongly connected to waterbodies, with many non-Māori also thinking of waterways as part of their identity (Knight 2016). At the same time, NZ’s agricultural industry has had an enormous influence not only on freshwater itself but also on the development of freshwater (and other environmental) policy in NZ. NZ commonly considers itself an “agricultural nation” and farming has occupied a dominant and frequently unquestioned place in NZ society and culture (Liepins and Bradshaw 1999; Pomeroy 2022).

In 2001, the NZ Government made special provisions with regards to anti-monopoly laws to allow the merger of dairy companies to form the Fonterra dairy company (McGiven 2016). The dairy industry had already begun a period of rapid expansion and intensification of farming systems and Fonterra’s establishment encouraged this further. Simultaneously, public concern about the consequences of this expansion and intensification developed. Waterbodies in the South Island region of Canterbury came under (and are still under) immense pressure as land was converted to irrigated, intensive dairy farming. Community environmental groups such as ‘Water Rights Trust’, ‘Save the Rivers’ and ‘Orari River Protection Group’ were formed in Canterbury in the early 2000s. They were not the first grassroots groups to challenge the intensification of land use and other anthropogenic stressors on waterways, and many more would follow. Chairman of the Water Rights Trust, Murray Rodgers, wrote in an opinion piece in 2004, “the damage to Canterbury's water continues to escalate faster than any remedial efforts … we are facing what could be fairly called a water crisis that demands urgent and comprehensive action” (Rodgers 2004).

Mounting public pressure on the agricultural sector led, in 2003, to the signing of an agreement between the Government and Fonterra called the ‘Dairying and Clean Streams Accord’ (Ministry for the Environment et al. 2003). The Accord committed (in a non-legally binding agreement) the dairy company to a number of goals it claimed would reduce the impact of dairy farming on waterways. In 2008, after a lack of progress on many of the accords short-term commitments and increasing pressure on waterways, the Agricultural Minister at the time commented: “If an industry wants to avoid regulation, it must take concerted action before the rest of the community demands government intervention” (New Zealand Government 2008).

In the 1990s and early 2000s, agricultural interests were able to take advantage of an absence of regulation to gain decades long consents for irrigation and to intensify farm systems (Robson-Williams et al. 2022). With problems rapidly worsening, public concern rising and the accord with industry failing, in 2007 the then-Labour Government began work on developing a National Policy Statement for freshwater and established national rules for human sources of drinking water. The Government changed in 2009 to a National-led government, which established a stakeholder group called the Land and Water Forum to provide environmental policy advice, particularly with regards to freshwater, to the Government. It included agricultural groups and, remarkably, even fertiliser companies (Land and Water Forum 2011).

In 2011, the Government produced the first National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM). Recognition of the need for a “limits-based approach” had been growing. Indeed, the NPS-FM 2011 stated that “setting enforceable quality and quantity limits is a key purpose of this national policy statement” (Ministry for the Environment 2011). However, it entirely devolved responsibility to regional councils for identifying and establishing limits. Regional councils are responsible for implementing national policy statements and other elements of NZ’s resource management law. Establishing limits was a challenge for regional councils, who sometimes lacked appropriate scientific expertise or resources to do this and commonly lacked the political will or skill needed to achieve necessary limits (Kirk et al 2020). In 2012, then-president of the NZ Freshwater Sciences Society, Professor David Hamilton, gave a speech at the annual conference highlighting, “an urgent need to implement a “limits-based approach” to freshwater management in New Zealand” (Hamilton 2012). He stressed that without this, the situation could get even worse. “Further land use intensification within catchments of these waterbodies will render past investment in their restoration largely useless and greatly add to the financial burden placed on future generations tasked with remediation of these degraded ecosystems” (Hamilton 2012).

However, the implementation of limits that provided for ecosystem health was impeded, largely (though not exclusively) by the influence of the agricultural sector who argued for various forms of self-regulation (such as the AccordFootnote1) and adopted a common anti-regulation tactic of introducing doubt or focusing on scientific uncertainty (Michaels 2008; Koolen-Bourke and Peart 2022). Agricultural lobby groups persistently focused on presenting costs to the sector or existing farm systems, which were frequently presented as costs to the country or community and avoided considering the benefits of a healthier environment or opportunities for more resilient farm systems (Hazeldine 2019). The impacts on society at large of agricultural intensification were consistently ignored by the dairy industry despite research revealing their externalities were equivalent or exceeded their revenue (Foote et al. 2015). At the same time, a significant amount of public funding was handed out by the Government to develop irrigation schemes that continued to intensify land use (New Zealand Government 2015).

In 2014 and 2017, the National Government revised the NPS-FM. Theses iterations introduced numerical limits for some contaminants. However, there were some serious omissions and some additions that were criticised by the public and ecologists. The public was particularly concerned with E. coli limits that did not prioritise safe swimming in waterbodies but allowed for levels of E. coli said to be suitable only for wading. Ecologists criticised the Government’s focus on the toxic effects of nitrate on invertebrates rather than nitrogen’s impact on the health of aquatic ecosystems (Death et al. 2018; Joy and Canning 2021). Diverting attention to toxicity allowed the Government to say they had brought in a nitrate bottom line for rivers, while the bottom line (6.9 mg/L NO3-N) allowed for levels of nitrogen pollution far beyond what aquatic ecosystems could assimilate (compare with the Australasian nitrate guideline of 0.44 mg/L NO3-N). Not uncoincidentally, the intensity of dairy operations is the strongest predictor of excessive nitrogen in NZ rivers (Julian et al. 2017).

“Progress made towards cleaner drinking water & healthier waterways.”

Throughout the 2010s, public awareness and concern over the worsening situation continued to climb. Multiple surveys found ∼80 percent of New Zealanders considered the freshwater crisis their most important environmental issue and/or wanted the Government to do more to prevent freshwater pollution (Stats NZ 2018; Rood 2019). Famously, the Whanganui River was granted legal personhood in 2017 (with time still needed to assess the outcome of this approach) (Talbot-Jones and Bennett 2022) and the health of waterways became a significant election issue in the General Election that same year (Hartevelt 2017). The Labour-led Government had campaigned on ‘clean rivers’ and had a clear mandate to significantly improve the health of freshwaters (New Zealand Labour Party 2017).

In May 2020, the freshwater reform package was released. Despite more than two years of input from expert panels, crucial advice was not included. The Science and Technical Advisory Group (STAG), supported by extensive research, gave explicit advice that precise nitrogen and phosphorus limits are necessary to protect the quality of drinking water and the ecological health of waterways, and recommended a dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) bottom line of 1 mg/L-1 ((STAG) 2019; Canning 2020; Ministry for the Environment 2020a; Science and Technical Advisory Group 2020). A subsequent case study of the NPS-FM 2020 process noted that, “The DIN was supported by the Freshwater Leaders Group [an advisory body of community, environmental and agricultural leaders], Te Kāhui Wai Māori [an advisory body of Māori environmental and agricultural leaders], the majority of STAG members, most academics, science bodies and health providers, environmental organisations, the vast majority of public submissions, iwi/Māori and MfE – the agency leading the reform. From this perspective its failure to pass muster was surprising” (Koolen-Bourke and Peart 2022). It is less surprising if you take into account the influence of the agricultural industry on NZ politics and environmental policy.

However, the NPS-FM 2020 was still a step forward. It made clearer the requirement for councils to take biological indicators, such as the MCI and Fish Index of Biological Integrity, into account when establishing limits on nitrogen and phosphorus for ecosystem health. Toxicity was retained (despite the advice of the STAG, which had proposed a single ecosystem health national bottom line for nitrogen) but was limited to 2.4 mg/L NO3-N. The Labour Government also introduced a new National Environmental Standard for freshwater (NES-F) that placed some restrictions on highly damaging agricultural activities like Intensive Winter Grazing (Donovan and Monaghan 2021) and the excessive use of nitrogenous fertilisers (Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020).

While it is difficult to adequately account for the monetary value of healthy waterbodies to the country (with many values not lending themselves well to monetary equivalence), the Ministry for the Environment found in its Regulatory Impact Statement that when accounting for the cost of implementing these reforms, the most likely result was a net benefit for the country (Ministry for the Environment 2020b). Alongside these changes, the previous Government also established a new distinct drinking water regulator (a government agency called Taumata Arowai) in 2021, as a direct result of the Havelock North outbreak (Government Inquiry into Havelock North Drinking Water 2017) It had also begun major structural reform to address the neglect of waste, storm and drinking water infrastructure (Chambers et al. 2022). Of all the changes, arguably the most important and effective update to freshwater policy has been the Te Mana o te WaiFootnote2. decision-making framework, described in the next section.

Te Mana o te Wai: “A much needed and long-overdue change in direction.”

Te Mana o te Wai is the decision-making framework of the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020. There is no single equivalent English word meaning mana. Mana encapsulates a number of English words, such as prestige, standing, authority, power, and status. Te mana o te wai means “the mana of the water”. However, in this article, Te Mana o te Wai refers to (ie is the name of) the decision-making framework of the NPS-FM 2020 that establishes a hierarchy of obligations and six principles for decision making. Te Mana o te Wai is borne from Māori concepts and thinking, and developed by Māori leaders and scholars for translation into policy (Harmsworth et al. 2016; Te Aho 2019; Kitson and Cain 2022). Its hierarchy of obligations prioritises the health of people and the natural environment by requiring councils to first protect the health of waterways and the quality of communities’ drinking water before commercial activities can be considered. The letter described Te Mana o te Wai as “a much needed and long-overdue change in direction”. Te Mana o te Wai does not preclude commercial activity. Instead, it gives the necessary weight in regional plans and in law to the health of waterways and the safety of drinking water sources.

Optimistically, Te Mana o te Wai has been tested over the last few years and appears to have the strength to provide meaningful protection against over exploitation of waterbodies. In a decision in 2023, commissioners noted, “No strong weighting was given to the protection of freshwater values versus its use and development [in previous iterations of the NPS-FM]” (Kirikiri and Cussins 2023). Their decision stated that, “Those words [the definition of Te Mana o te Wai from the NPS-FM 2020] are the primary driver for our decision to decline the T2 applications” (p. 43). The applications had been to take 8.44 M m3 /y of groundwater for irrigation which commissioners were “not persuaded that the potential adverse effects of the application can be avoided or mitigated” (p. 42) These included “cultural values, on flows in surface water bodies and associated effects on the biota that dwell within those water bodies, and effects on other current users of shallow groundwater, including for irrigation, stock water, and domestic supply” (p. 42). Some other recent decisions in Canterbury and Southland have also seen Te Mana o te Wai provide the basis for more favourable decisions for the health of waterways (Williams 2022, 2023).

Te Mana o te Wai also makes clearer the relationship between mana whenua (Indigenous people of the land – Māori groups with ancestral connection to a specific region of NZ), the wider community, and regional councils in decision-making through its six principles. Māori have commonly been engaged with regional councils and other agencies on freshwater issues but marginalised in final decision-making (McNeill 2016).

“If you proceed with your proposals to undo the country’s freshwater policy, they will only get worse.”

The main proposals that have consequences for freshwater in the coalition agreements between the three parties that have formed the new Government are:

“Replace the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 to allow district councils more flexibility in how they meet environmental limits and seek advice on how to exempt councils from obligations under the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 as soon as practicable” (New Zealand National Party and ACT New Zealand 2023).

“Replace the National Policy Statement for Freshwater 2020 to rebalance Te Mana o te Wai to better reflect the interests of all water users” (New Zealand National Party and ACT New Zealand 2023).

“National’s manifesto commitment to remove two farming regulations for every new one introduced will be replaced by this agreement’s commitment to reduce farming regulation and undertake comprehensive regulatory review across Government” (New Zealand National Party and ACT New Zealand 2023).

“Replace the Resource Management Act 1991 with new resource management laws premised on the enjoyment of property rights as a guiding principle” (New Zealand National Party and ACT New Zealand 2023).

“Cut red tape and regulatory blocks on irrigation, water storage, managed aquifer recharge and flood protection schemes” (New Zealand National Party and New Zealand First 2023)

The parties in the new Government have attempted to justify replacing the NPS-FM 2020 in a number of fallacious ways. The National party has emphasized that they want to ensure “that local communities get the opportunity to customise and to have nuanced processes in place that ensure that at a community level they can make decisions that are appropriate for that community” (New Zealand Parliament 2023). Using the word “community” here appears to intentionally obscure the commercial interests that are pushing the new Government to weaken environmental policy.

Regional councils and local communities already have significant flexibility in how they apply the policy to their catchments. The main and essential restriction is that no council or community can decide to make freshwater pollution worse. Waterbodies are not required to be pristine but, where they are below bottom lines, work is required over time to restore their health. The essential differences between previous iterations of the NPS-FM and the NPS-FM 2020 are that bottom lines are clearer and the power imbalance between commercial and public interests (that has greatly contributed to the country's freshwater crisis) has begun to be addressed by Te Mana o te Wai.

The ACT party has been particularly focused on getting rid of Te Mana o te Wai, as one of its many anti-Māori policies (Duff 2023), its leader stating that Te Mana o te Wai is “the same as waving crystals over the water to drive out evil spirits, and it’s truly bonkers” (ACT Party 2023b). It is important to understand the connection between environmental exploitation and the intentional marginalisation of Indigenous peoples (eg Whyte 2018), as well as recognise the value of Indigenous thinking and leadership on the severe environmental problems we all face (of which Te Mana o te Wai is a prime example).

The consequences of these proposed changes would be grave, setting the country and the public back decades in the work to protect and restore the health of waterways and locking in damage where tipping points are reached. The impacts will be on the health of our natural environment, our own health, our social and cultural well-being, and our economy would be severe, particularly when we take the amplifying effects of climate change into account. These impacts will be felt most intensely by marginalised communities, and the young and future generations of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Conclusion: “Listen to the wider community … and provide the leadership needed.”

As the letter notes, “the public has been calling on central government to provide stronger protection for water and to drive the restoration of rivers, lakes, and other waterbodies for decades. History tells us concern and pressure from the public will only increase.” There will undoubtedly be resistance from many corners against the new Government’s approach to freshwater. What we hope is that those in Government who may care about the health of waterbodies and have a longer-term vision for the country “listen to the wider community – not just the minority of voices who have asked you to undo the progress the country has made towards cleaner drinking water and healthier waterways.”

The leadership needed now for NZ’s waterways is (a) to continue with the progress made in freshwater policy development and allow regional councils to complete their regional plans under the NPS-FM 2020, (b) support and fund regional councils and other appropriate agencies to develop best practice, long term monitoring programmes that monitor not only in-stream variables but also land use and measures of intensity that can provide appropriate and adequate data to inform future plans, and (c) intensify government efforts to develop a long-term vision with short-term goals to transition Aotearoa New Zealand’s agricultural sector to systems that are healthy, sustainable and resilient and away from high input, intensive systems.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Thank you to David Hamilton for encouragement to write this article and to the three anonymous reviewers for their useful and supportive feedback. Thank you to the other 49 signatories on the open letter.

Notes

1 In 2013, the dairy sector signed another accord with the Government called the Sustainable Dairying: Water Accord DairyNZ. 2023. Sustainable Dairying: Water Accord. [accessed 13 January 2024]. https://www.dairynz.co.nz/regulation/policy/sustainable-dairying-water-accord/.

2 More detail on Te Mana o te Wai may be found here.

References

- Abell JM, van Dam-Bates P, Özkundakci D, Hamilton DP. 2020. Reference and current Trophic Level Index of New Zealand lakes: benchmarks to inform lake management and assessment. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 54(4):636-657.

- ACT Party. 2023a. Standing up for Rural New Zealand. [accessed 9 January 2024]. https://www.act.org.nz/primary-industries.

- ACT Party. 2023b. Will Mauri Make Our Water Safe To Drink. [accessed 9 January 2024] https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PA2306/S00205/will-mauri-make-our-water-safe-to-drink.htm

- Anderson SE, Closs GP, Matthaei CD. 2020. Agricultural Land-Use Legacy, The Invasive Alga Didymosphenia geminata and Invertebrate Communities in Upland Streams with Natural Flow Regimes. Environmental Management. 65(6):804-817.

- Birdling, G. 2020. Evidence in Chief of Greg Birdling for Christchurch City Council, Land and Water Regional Plan Change 7 Hearing Dated 17 July 2020. https://api.ecan.govt.nz/TrimPublicAPI/documents/download/3909177,

- Burge O, Price R, Wilmshurst J, Blyth J, Robertson H. 2023. LiDAR reveals drainage risks to wetlands have been under-estimated. New Zealand journal of ecology.

- Burns C, Rees A, Wood S. 2024, Predicting distribution and establishment of two invasive alien Daphnia species in diverse lakes in New Zealand-Aotearoa PREPRINT (Version 1) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3147414/v1

- Canning AD. 2020. Nutrients in New Zealand rivers and streams: an exploration and derivation of national nutrient criteria. Wellington: Essential Freshwater Science and Technical Advisory Group.

- Chakravarthy K, Charters F, Cochrane TA. 2019. The Impact of Urbanisation on New Zealand Freshwater Quality. Policy Quarterly. Vol. 15 (2019): (3).

- Chambers T, Douwes J, Mannetje At, Woodward A, Baker M, Wilson N, Hales S. 2022. Nitrate in drinking water and cancer risk: the biological mechanism, epidemiological evidence and future research. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 46(2):105-108.

- Chambers T, Wilson N, Hales S, Prickett M, Ellison E, Baker MG. 2022. Beyond muddy waters: Three Waters reforms required to future-proof water service delivery and protect public health in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand medical journal. 135(1566):87-95.

- Close ME, Humphries B, Northcott G. 2021. Outcomes of the first combined national survey of pesticides and emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in groundwater in New Zealand 2018. Sci Total Environ. 754:142005. eng.

- Davis M, Midwinter AC, Cosgrove R, Death RG. 2021. Detecting genes associated with antimicrobial resistance and pathogen virulence in three New Zealand rivers. PeerJ. English.

- DairyNZ. 2023. Sustainable Dairying: Water Accord. [accessed 13 January 2024]. https://www.dairynz.co.nz/regulation/policy/sustainable-dairying-water-accord/.

- Daughney C, Wall M. 2007. Groundwater quality in New Zealand: state and trends 1995-2006. GNS Science consultancy report. 23.

- Dench WE, Morgan LK. 2021. Unintended consequences to groundwater from improved irrigation efficiency: Lessons from the Hinds-Rangitata Plain, New Zealand. Agricultural Water Management. 245:106530.

- Donovan M, Monaghan R. 2021. Impacts of grazing on ground cover, soil physical properties and soil loss via surface erosion: A novel geospatial modelling approach. Journal of Environmental Management. 287:112206.

- Currie LD, Christensen CL, editors. Why aren't we managing water quality to protect ecological health? Farm environmental planning – Science, policy and practice; 2018; Palmerston North, NZ. Fertilizer and Lime Research Centre.

- Duff M. 2023. ‘A massive unravelling’: fears for Māori rights as New Zealand government reviews treaty. The Guardian. [accessed 12 January 2023]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/02/fears-for-maori-rights-as-new-zealand-government-reviews-waitangi-treaty.

- Foote KJ, Joy MK, Death RG. 2015. New Zealand Dairy Farming: Milking Our Environment for All Its Worth. Environmental Management. 56(3):709-720.

- French R., Charon J., Lay CL., Muller C., & Holmes EC. 2022. Human land use impacts viral diversity and abundance in a New Zealand river. Virus evolution, 8(1), veac032. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/veac032

- Gadd J, Snelder T, Fraser C, Whitehead A. 2020. Current state of water quality indicators in urban streams in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 54(3):354-371.

- Gilpin BJ, Walker T, Paine S, Sherwood J, Mackereth G, Wood T, Hambling T, Hewison C, Brounts A, Wilson M et al. 2020. A large scale waterborne Campylobacteriosis outbreak, Havelock North, New Zealand. Journal of Infection. 81(3):390-395.

- Good JF, O’Sullivan AD, Wicke D, Cochrane TA. 2014. pH Buffering in Stormwater Infiltration Systems—Sustainable Contaminant Removal with Waste Mussel Shells. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 225(3):1885.

- Government Inquiry into Havelock North Drinking Water. 2017. Report of the Havelock North Drinking Water Inquiry: Stage 2. Auckland, New Zealand.

- Hageman KJ, Aebig CHF, Luong KH, Kaserzon SL, Wong CS, Reeks T, Greenwood M, Macaulay S, Matthaei CD. 2019. Current-use pesticides in New Zealand streams: Comparing results from grab samples and three types of passive samplers. Environmental Pollution. 254:112973.

- Hamilton D. 2012. Beyond the Limits. Beyond the Limits New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Conference; Dunedin, NZ.

- Harmsworth G, Awatere S, Robb M. 2016. Indigenous Māori values and perspectives to inform freshwater management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ecology and Society. 21(4).

- Hartevelt J. 2017. NZ Election 2017: The environment election. NZ Herald. [accessed 8 January 2023]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/96089426/nz-election-2017-the-environment-election.

- Hazeldine T. 2019. Memorandum: Dairy NZ Economic Modelling. [accessed 9 January 2023] https://eds.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/191217-Tim-hazeldine-memo-final.pdf

- Joy MK, Canning AD. 2021. Shifting baselines and political expediency in New Zealand’s freshwater management. Marine and Freshwater Research. 72(4):456-461.

- Joy MK, Foote KJ, McNie P, Piria M. 2019. Decline in New Zealand’s freshwater fish fauna: effect of land use. Marine and Freshwater Research. 70(1):114-124.

- Julian JP, de Beurs KM, Owsley B, Davies-Colley RJ, Ausseil AGE. 2017. River water quality changes in New Zealand over 26 years: response to land use intensity. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 21(2):1149-1171.

- Kirikiri R, Cussins T. 2023. Ruataniwha Tranche 2 Resource Consent Applications – Decision. [accessed 8 January 2023] https://www.hbrc.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Ruataniwha-Tranche-2-Decision-Final.pdf

- Kirk N, Robson-Williams M, Fenemor A, Heath N. 2020. Exploring the barriers to freshwater policy implementation in New Zealand [Article]. Australasian Journal of Water Resources. 24(2):91-104.

- Kitson J, Cain A. 2022. Navigating towards Te Mana o te Wai in Murihiku. New Zealand Geographer. 78(1):92-97.

- Knight K. 2016. New Zealand's rivers : an environmental history. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press.

- Koolen-Bourke D, Peart R. 2022. Science for Policy: The role of science in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management. Auckland, NZ: Environmental Defence Society.

- Land and Water Forum. 2011. Forum Members. [accessed 2024 12 January 2024]. http://www.landandwater.org.nz/Site/About_Us/Forum_Members.aspx#H126742-1.

- Larned ST, Snelder T, Unwin MJ & McBride GB. 2016. Water quality in New Zealand rivers: current state and trends, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 50:3, 389-417, DOI: 10.1080/00288330.2016.1150309

- Liepins R, Bradshaw B. 1999. Neo-Liberal Agricultural Discourse in New Zealand: Economy, Culture and Politics Linked. Sociologia Ruralis. 39(4):563-582.

- Ling N. 2010. Socio-economic drivers of freshwater fish declines in a changing climate: a New Zealand perspective. Journal of Fish Biology. 77(8):1983-1992.

- McGiven A. 2016. The Future Opportunities and Challenges for one of the World's Largest Dairy Export Firms: Fonterra in New Zealand. The Journal of Applied Business and Economics. 18(3):16-23. English.

- McNeill J. 2016. Scale Implications of Integrated Water Resource Management Politics: Lessons from New Zealand. Environmental Policy and Governance. 26(4):306-319.

- Michaels D. 2008. Doubt is Their Product: Public Health and Manufactured Uncertainty. Epidemiology. 19(6):S27.

- Ministerial Inquiry into Land Uses in Tairawhiti and Wairoa. 2023. Outrage to optimism: Report of the Ministerial Inquiry into land uses associated with the mobilisation of woody debris (including forestry slash and sediment in Tairāwhiti /Gisborne District and Wairoa District. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Outrage-to-Optimism-CORRECTED-17.05.pdf

- Ministry for the Environment. 2011. National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2011. Wellington, NZ.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2020a. Action for healthy waterways: summary of modelling to inform environmental impact assessment of nutrient proposals. . Wellington, NZ

- Ministry for the Environment. 2020b. Regulatory Impact Analysis Action for healthy waterways. Part I: Summary and Overall impacts. Wellington, NZ.

- Ministry for the Environment, Ministry for Primary Industries. 2018. Essential Freshwater: Healthy Water, Fairly Allocated. Wellington, NZ.

- Ministry for the Environment, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fonterra Co-operative Group, Zealand Local Government New Zealand. 2003. Dairying and Clean Streams Accord. Wellington, NZ.

- Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand. 2019. Environment Aotearoa 2019. Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand.

- Morton J. 2023. Government’s freshwater reform sparks backlash from 50 experts, leaders. NZ Herald. [accessed 9 January 2024]. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/governments-freshwater-reform-engenders-backlash-from-50-experts-leaders/.

- New Zealand First. 2023. New Zealand First 2023 Policies. [accessed 9 January 2024]. https://www.nzfirst.nz/2023_policies.

- New Zealand Government. 2008. Call for action on nutrients management. [accessed 9 January 2024] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/call-action-nutrients-management

- New Zealand Government. 2015. Budget 2015: Funding boost for Irrigation Acceleration Fund. [accessed 7 January 2024] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/budget-2015-funding-boost-irrigation-acceleration-fund

- New Zealand Government. 2017. Speech from the Throne. [accessed 9 January 2024] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-throne-2017

- New Zealand Labour Party. 2017. Clean rivers for future generations. [accessed 9 January 2024] https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PA1708/S00173/clean-rivers-for-future-generations.htm

- New Zealand National Party. 2023. Getting back to farming. [accessed 9 January 2024]. https://www.national.org.nz/getting_back_to_farming.

- New Zealand National Party, ACT New Zealand. 2023. Coalition Agreement between the National Party and the ACT Party. New Zealand National Party.

- New Zealand National Party, New Zealand First. 2023. Coalition Agreement between the National Party and the New Zealand First Party. New Zealand National Party.

- New Zealand Parliament. 2023. Oral Questions — Questions to Ministers. Question No. 11—Environment. Wellington, NZ; [accessed 12 January 2024]. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/HansS_20231219_053250000/11-question-no-11-environment.

- Norris M, Johnstone PR, Green SR, Trolove SN, Liu J, Arnold N, Sorensen I, van den Dijssel C, Dellow S, van der Klei G et al. 2023. Using drainage fluxmeters to measure inorganic nitrogen losses from New Zealand’s arable and vegetable production systems. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 51(2):274-296.

- Özkundakci D. & Lehmann MK. 2019. Lake resilience: concept, observation and management, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 53:4, 481-488

- Phiri BJ, Pita AB, Hayman DTS, Biggs PJ, Davis MT, Fayaz A, Canning AD, French NP, Death RG. 2020. Does land use affect pathogen presence in New Zealand drinking water supplies? Water Research. 185:116229.

- Pomeroy A. 2022. Reframing the rural experience in Aotearoa New Zealand: Incorporating the voices of the marginalised. Journal of Sociology. 58(2):236-252.

- Prickett M. 2023. Water: What are National and Act doing in the shadows? Newsroom. https://newsroom.co.nz/2023/09/10/what-are-national-and-act-doing-in-the-shadows/.

- Prickett M, Chambers T, Hales S. 2023. When the first barrier fails: public health and policy implications of nitrate contamination of a municipal drinking water source in Aotearoa New Zealand. Australasian Journal of Water Resources.1-10.

- Quinn JM, Hickey CW. 1990. Characterisation and classification of benthic invertebrate communities in 88 New Zealand rivers in relation to environmental factors. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 24(3):387-409.

- Ramezani J, Akbaripasand A, Closs GP, Matthaei CD. 2016. In-stream water quality, invertebrate and fish community health across a gradient of dairy farming prevalence in a New Zealand river catchment. Limnologica. 61:14-28.

- Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020. 2020. LI 2020/174. New Zealand.

- Richards J, Chambers T, Hales S, Joy MK, Radu T, Woodward A, Humphrey A, Randal E, Baker MG. 2022. Nitrate contamination in drinking water and colorectal cancer: Exposure assessment and estimated health burden in New Zealand. Environmental research. 204(Pt C):112322-112322.

- Robson-Williams M, Painter D, Kirk N. 2022. From Pride and Prejudice towards Sense and Sensibility in Canterbury Water Management. Australasian Journal of Water Resources.1-20.

- Rodgers M. 2004. 20 July 2024. Water Crisis Needs Action. The Christchurch Press.

- Rogers KM, van der Raaij R, Phillips A, Stewart M. 2023. A national isotope survey to define the sources of nitrate contamination in New Zealand freshwaters. Journal of Hydrology. 617:129131.

- Rood D. 2019. How water is reshaping the political landscape. Policy Quarterly. 15(3):22-28.

- Rowe DK. 2007. Exotic fish introductions and the decline of water clarity in small North Island, New Zealand lakes: a multi-species problem. Hydrobiologia. 583(1):345-358.

- Science and Technical Advisory Group. 2019. Freshwater Science and Technical Advisory Group Report to the Minister for the Environment. Wellington, NZ.

- Science and Technical Advisory Group. 2020. Freshwater Science and Technical Advisory Group: Supplementary report to the Minister for the Environment. Wellington, NZ.

- Snelder T, Larned ST, & McDowell RW. 2018. Anthropogenic increases of catchment nitrogen and phosphorus loads in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 52(3), 336-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2017.1393758

- Stats NZ. 2018. GSS 2018 Metadata Package. [accessed 10 January 2024]. https://datainfoplus.stats.govt.nz/item/nz.govt.stats/ccaab3c2-5e1e-48c1-9663-c34462423a0f/62.

- Stats NZ. 2022. Lake quality data. [updated 14 April 2022; accessed 9 January 2024]. https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/lake-water-quality.

- Stewart C, Gabrielsson R, Shearer K, Holmes R. 2019. Agricultural intensification, declining stream health and angler use: a case example from a brown trout stream in Southland, New Zealand New Zealand Natural Sciences. 44.

- Stewart-Harawira MW. 2020. Troubled waters: Maori values and ethics for freshwater management and New Zealand's fresh water crisis. WIREs Water. 7(5):e1464.

- Talbot-Jones J & Bennett J. 2022. Implementing bottom-up governance through granting legal rights to rivers: a case study of the Whanganui River, Aotearoa New Zealand, Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 29:1, 64-80, DOI: 10.1080/14486563.2022.2029775

- Taylor LB. 2022. Stop drinking the waipiro! A critique of the government's ‘why’ behind Te Mana o te Wai. New Zealand Geographer. 78(1):87-91.

- Te Aho L. 2019. Te Mana o te Wai: An indigenous perspective on rivers and river management. River Research and Applications. 35(10):1615-1621.

- Thomaz SM, Barbosa LG, de Souza Duarte MC, Panosso R. 2020. Opinion: The future of nature conservation in Brazil. Inland Waters. 10(2):295-303.

- Tipa GT. 2013. Bringing the past into our future—using historic data to inform contemporary freshwater management. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 8(1-2):40-63.

- van Hamelsveld S, Kurenbach B, Paull DJ, Godsoe WA, Ferguson GC, Heinemann JA. 2023. Indigenous food sources as vectors of Escherichia coli and antibiotic resistance. Environmental Pollution. 334:122155.

- Water NZ. 2020. National Performance Review 2019/2020. [accessed 27 February 2024]. https://www.waternz.org.nz/Attachment?Action=Download&Attachment_id=5110

- Water NZ. 2022. National Performance Review 2021/2022. [accessed 27 February 2024]. https://www.waternz.org.nz/NationalPerformanceReview

- Weeks ES, Death RG, Foote K, Anderson-Lederer R, Joy MK, Boyce P. 2016. Conservation Science Statement. The demise of New Zealand's freshwater flora and fauna: a forgotten treasure. Pacific Conservation Biology. 22(2):110-115.

- Whitehead A, Fraser C, Snelder T, Walter K, Woodward S, Zammit C. 2022. Water quality state and trends in New Zealand Rivers: Analyses of national data ending in 2020. Christchurch, NZ.

- Whyte K. 2018. Settler colonialism, ecology, and environmental injustice. Environment and Society, 9(1), 125-125–144. doi: https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2018.090109

- Williams D. 2022. ECan terminates water consents. Newsroom. [accessed 12 January 2024]. https://newsroom.co.nz/2022/03/18/ecan-terminates-water-consents/.

- Williams D. 2023. Finally, water’s health is being put first. Newsroom. [accessed 12 January 2024]. https://newsroom.co.nz/2023/03/30/finally-waters-health-is-being-put-first/.