ABSTRACT

This article documents the creation and distribution of a new sample pack, Instruments INDIA, as an intervention against systemic orientalist practices observable within the marketing, branding and production of non-Western instrument sample packs. This intervention draws upon Edward Said’s model of Orientalism and Stuart Hall’s theories of representation, fortifying an interrogation of practices that misrepresent diverse sonic content, musicians and cultures in negative ways. The research brings into focus the influence digital samplers and early sample library CDs had in determining technical configurations and misrepresentation tendencies found within paratextual elements of contemporary sample packs. The article joins forces with a leading sample pack distributor, Loopmasters, to cultivate change via new policy documents and good practice principles. Attending to problematic representation issues at the start of the music production chain offers a strategy to scaffold and promote positive change throughout the production process and into other connected music industry areas, where influential language and imagery align sample content with music production goals and aspirations. The article offers a first-hand account of sample pack development in collaboration with musicians of Indian musical instruments, which provide a case study to better understand and inform more ethical commercial practices in the future.

Introduction

Sample packs containing non-Western instrument content produced and sold by Western distribution companies face numerous challenges in how they are represented, packaged, labelled and sold to international markets. Stereotypes, inaccuracies, misconceptions and racism abound in this corner of the music industry, seemingly unruffled by the seismic force of Black Lives Matter in 2020 and statements of “we must do better” regarding representing and reflecting the diversity of multicultural societies. The project notices this delay in action and joins forces with the sample pack industry in urging reflection and change to audio products that disregard updated societal norms. The article furthers this dialogue, critically asking where such outmoded practices stem from and how might sonically diverse content be better represented and handled in the future. Guiding this interrogation of inequities in the production and advertising of non-Western instrument sample packs are Edward Said’s Orientalism (Citation1978) and Stuart Hall’s theories of representation (Citation1996, Citation2013), which act as continuing threads to probe current depictions of culture and difference while assisting in establishing ways to contest and move forward,Footnote1 with better practice. The article argues that coalescing these two prominent theoretical proponents in this way offers an opportunity to see how images and text stand in for large entities such as musical traditions, cultures and countries, and simultaneously encourages the questioning of reductive representation choices. In short, through the lens of Said’s model of Orientalism an explanation is found for a system that hosts and packages sounds with unjust and insensitive imagery and text, while Hall’s representation theories enable the unpacking and decoding of the functionality of such image and text choices, revealing the constitutive role these representations have in social and political life (Hall Citation1996, 443). While the roots of these theories circle tightly around the portrayal of Black subjects and imagery (Hall), and the Orient (Said), the relevance of these arguments are undeniably germane to the treatment of non-Western musical instrument content that provides the subject matter for this article.

The methodology for this research involved the creation of a new sample pack, entitled Instruments INDIA, which was commercially released by Loopmasters in 2022, as a collaboration with 11 musicians of Indian musical instruments (Aditi Sen (Ghungroo), Ganesan S (Udukkai and Sangu), Kirpal Panesar (Dilruba and Tar Shehnai), Kousic Sen (tabla), Prathap Ramachandra (Ghatam, Kanjira and Konnakol), Raaheel Husain (Hindustani vocal and Sitar), Rajeeb Chakraborty (Sarod), Rekesh Chauhan (Harmonium), Shyla Shanmugalingam (Veena), Tarun Bhattacharya (Santoor), Yarlinie Thanabalasingam (Carnatic Vocal)). Participating and observing the commercialisation process via a collaborative and reflexive process, with the musicians who contributed their sounds, established an experiential, practice-led situation to witness the process, production and interconnected system challenges, while giving voice and space to those whose sounds populate the sample pack’s interior. Creating a new sample pack which modelled good practice also provided a tool for leverage with the sample pack distributor for initiating dialogue and convening change, while offering a tangible way to evidence and critique previous out-of-step practices.

In addition to sample pack production, the methodology involved a mix of archival research and qualitative data gathering. A survey of current downloadable sample packs from a range of distributors observed the conventions and norms for handling non-Western instrument sounds, while archival research of earlier sample library CDs (the precursor to the contemporary downloadable sample pack) from the 80s and 90s, which feature non-Western instrument sounds, provided points of comparison. Further, a series of engagement events, conversations and interviews with musicians, academics, sample pack distributors and producers created moments to spotlight perspectives from key stakeholders and enabled a co-created guidance document to emerge from the research to benefit producers and distributors in future product releases.

The article is divided into four parts for the purpose of organising several themes and stages of the research: Part 1 provides a background to the Instruments INDIA project and the formative years recording musicians. Part 2 introduces sample packs and their history, providing definitions and an overview of how non-Western instrument sounds were handled in the early days of selling sound offering a comparison with contemporary practices. Part 3 documents the construction of the Instruments INDIA sample pack and discusses the journey and challenges of commercialising a collection of non-Western instrument sounds. Part 4 presents the key findings and introduces a co-created guidance document aimed at supporting sample pack producers and distributors who create and sell non-Western sample packs.

Part 1: background

Project background

The Instruments INDIA project (a collaboration between the author and Milap – an international Indian arts and culture companyFootnote2) resulted in the creation of a sound archive containing over five hours of audio recordings of Indian musical instruments, motivated by a mutual interest in the application of these sounds for educational and creative purposes. 28 Indian musical instruments featured in this collection and sound bites of these recordings made their way onto the Instruments INDIA educational website and fuelled a series of electronic music works.Footnote3 The sound archive was used again in 2016, populating a downloadable tablet app to engage and encourage participation from classroom learners with the sounds of Indian musical instruments via quizzes and games where sound provided the central component. The latest application and repackaging of the sound archive provides the focus for this article – the creation of the Instruments INDIA sample pack as an idea emerging from the desire to engage further afield with global end-users and specifically music producers within the sample pack community.

Recording

28 different musical instruments were recorded in a variety of spaces including recording studios, performance venues, green rooms, quiet office spaces and hotel rooms around the UK and India between 2012–13 (). The recordings captured audio tours around the instruments, flourishes of improvisations, small motifs, individual notes and verbal explanations of playing styles. Musicians were approached by Milap to scope out interest in providing sounds for online educational resource development and payment for these sonic contributions was written into artist contracts since many of these musicians were contracted by Milap for UK concert performance tours and educational events.

At the point of capture, the future life of these recordings was unknown regarding how such material would feed and fuel further digital resources via creative repurposing. The unknown destiny of sound recordings has been observed within the field of ethnomusicology; as Seeger (Citation1986) notes “no one can predict the ways their collections will be used. Some will become one of the building blocks of cultural and political movements; some will bring alive the voice of a legendary ancestor for an individual; some will stimulate budding musicians, some will soothe the pain of exile, and some will be used for restudies of primary data that may revolutionise approaches to world music”. Feldextends this thinking, forecasting the woes associated with commercial distribution of field recordings “the intentions surrounding a recording’s original production, however positive, cannot be controlled once a commodity is in commercial circulation … field recordings have served to validate very diverse agendas, many of which were unanticipated and may now be unwelcome or distasteful to recordists or those recorded … unwittingly or not, they – we – have been central players in creating a global schizophonic condition whose consequences are now vastly more complex and open to contestation than any of its participants could have anticipated” (Citation1996, 11). This schizophonia (the split between an original sound and its electroacoustical transmission or reproduction) stands as a cautionary tale, attributed by the many examples in the literature focused on permissions, crediting, recompense and ethics of sample capture and use (Chang Citation2009; Feld Citation1996; Franklin Citation2021; Hesmondhalgh Citation2000, Citation2006; Katz Citation2010).

The process of collection was not concerned with specific techniques, scales or types of music or performances per se, but rather the sounds, timbres and gestures each musician was willing to contribute. Eliciting sound from each musician became the topic of much discussion and reflection within the partnership. The uniqueness of instrument playing styles, the gharanasFootnote4 and lineages of the performers, along with British-born versus Indian-born contributions, all came sharply into focus.Footnote5 Standing back from the sound recordings and viewing them as a whole collection presented a snapshot of highly respected, renowned musicians of Indian music who held affiliation with Milap and benefitted from Milap’s artist development programmes.Footnote6 This recording work captured a set of results that were a product of the time, the blend of musicians and the openness to any sound given in the recording sessions. Context and circumstance at the point of audio capture are important to acknowledge since “the acts and conditions of recording bring about transformations of many different kinds: authenticity is disrupted; some sound is amplified, some silenced; sound is given new life, even as salvage and sacrifice coincide” (Bohlman Citation2002, 23).

Creative application of sounds

The audio recordings were viewed as educational and creative assets and their use extended beyond the Instruments INDIA website and experimental compositional work.Footnote7 Wider interest in the project and audio was in conflict with the full audio collection sitting behind closed doors, inaccessible to the public or individuals with creative intentions. Lobley and Jirotka’s discussions of the wider application of such audio resources states, “sound recordings have great potential for widespread use by, and engagement with, diverse audiences. Sound is highly portable and can be delivered digitally … in a variety of ways” (Citation2011, 3). One approach devised to counter the dormant state of the archive was the establishment of a commissioning competition, calling for international artists to propose new ways of utilising the sound archive as an initiative to foster constructive cross-cultural understanding. This venture was shaped by Milap’s mission to “inspire, educate and entertain people of all backgrounds through Indian arts” coupled with their agenda for audience development and their funder’s recommendations to grow their digital presence and establish new outlets of creativity.Footnote8 Three projects were commissioned through this scheme between 2016–17; Ish Sherawat’s Mimetic patterns (a multichannel audio work), Greg Dixon’s 12 electroacoustic miniatures, Anantatā (Navajīvanacand) with an accompanying Space Regenerator instrument (a new electronic instrument, see ), and Steven Naylor’s Rivers (a fixed media composition).

Figure 2. Greg Dixon’s The Space Regenerator (Citation2017), a new instrument invented for his submission to the instruments INDIA composition commission.

From sound archive to sample pack

Extending and increasing the creative interaction with the sound archive became an ongoing goal of the partnership, transpiring from the wealth of creative responses from the commissioning prize. With each new application of the sound archive we witnessed the sounds renegotiate their identity as informants, symbolic audio, educational data and creative potential in a process Feld terms as “schizophonic mimesis”.Footnote9 By transforming the sound archive into a commercial sample pack, a greater number of end-users was anticipated, where the sounds would achieve a wider, global reach unbound by commissioning briefs or restrictions.Footnote10 A process of selection, reduction and transformation followed to sift and consolidate five hours of recordings into a curated sample pack of 300 sounds, formatted for music production purposes.

Part 2: sample packs and their history

What is a sample pack?

Sample packs are collections of sounds specially designed for end-users (producers of digital music) to use as building blocks in their music productions. Sample packs are typically divided into loops and one-shots. Loops can be melodies, rhythms, drones, or beats which are created to seamlessly loop if placed in a repetitive sequence within a DAW (digital audio workstation). One-shots are single gestures, such as a note, chord, percussive hit, beat, vocal stab or sound effect. Many music professionals rely on sample packs to get a start in their productions, as Delhi-based film composer and music producer, Girishh Gopalakrishnan describes, “I’m working actively on a number of feature films in India … I can say that a lot of my sketching of how I start creating music both for background scores and songs involves the use of a lot of samples as you immediately get a picture of what you require in a composition as a broad sketch or idea … it’s really easy to give the client a direct idea of what this is going to sound like, not only as a production, but as a mock-up which will be replaced or augmented by other live instrumentation” (in conversation with Gopalakrishnan Citation2022). Others use sample packs to venture into new musical territories to find inspiration or to add detail and interest to ongoing projects.

Sample packs are often themed, enabling categorisation within existing genres or sound origins, for example, “Lo-fi soul” or “tabla” sounds respectively. The size of a sample pack is variable but typically falls in the range of 50–1000 sounds in each collection. While loops and one-shots comprise the majority content within sample packs, other content can be included such as MIDI patterns, scale files and patches, which are all designed to configure setting in a user’s DAW depending on the theme of the pack. There are also specialist sample packs known as multisample sample packs that aim to imitate instrument sounds and qualities through velocity sensitive triggering. In the recording stage for multisample sample packs, each note of an instrument is captured at a range of dynamic levels (e.g. soft, medium and loud) so that when these samples are assigned to a midi controller, the instrument’s character is more accurately reflected depending on the exerted pressure on the controller.

A further specialist pack worth mentioning is the construction kit, which provides loops, layers, beats, rhythms, synths, pads and instrument sounds all in one downloadable folder where the contents can be combined to re-create a track or be completely redesigned and reworked. Construction kits provide sound materials designed to work together where the samples are all in the same key, have the same bpm (beats per minute) and are based on the same chord or song structure, groove, and feeling. Construction kits give users insights into how producers arrange sounds so this can be replicated in future tracks. Many music producers appreciate such packs for their flat-pack-like assembly model and the learning opportunities these audio resources provide.

Sample packs are typically bespoke creations, cultivated in the studio from acoustic or synthetic sources and destined solely for distribution. These are then collated in downloadable folders and packaged with digital cover art (a visual or image which usually includes the title of the sample pack), a text product description and technical information detailing file types and a breakdown of content, and then sold via distributor websites. End-user engagement with sample packs prior to purchase is via a mix of digital packaging (artwork, title, product description and categorisation tagging) and sample previews (audio snapshots of the product together with a demo track) to promote interest and entice consumers.

Once purchased, end-users utilise sample pack content in vastly different ways. Versatility in application satisfies broad audiences from those looking for a single sound to enhance their mix to those wanting to start something new with a set of sounds for inspiration. End-users can modify samples heavily, so much so that they are no longer identifiable. Further, sample packs are not always purchased or used to retain their links or associations to their commercial categorisations, for example, sounds from a dubstep sample pack do not necessarily end up in a dubstep production. Such flexibility “gives people the chance to make new genres … you are always hearing people using traditional Indian vocals in psytrance [a subgenre of trance music which explores high tempo riffs and high energy arrangements of rhythms] tracks or festival music, it’s just great to hear people blending legitimate sources of sounds to create their own stuff” (in conversation with Conor Bailey, Artist Relations Coordinator, Loopmasters 2022). From the moment the sample pack is commercially released for sale, the content producer relinquishes all control over who uses them and what they are used for as per the terms and conditions of sale.

A brief history of sample packs

The history of sample packs is relatively short and entwined with the emergence of sound effects as observed by Théberge, “the precedence for the production and marketing of collections of individual sounds lay within the film and broadcast industry, not the music industry” (Théberge Citation2003, 96). The creation of a commercially released sound library appears to have first emerged in 1969 with the release of the first BBC Sound Effects library No. 1 (by BBC Radio Enterprises) on phonograph record. These early sound library provisions predominantly found application within sound effects contexts such as theatre productions, film sound and radio. Music making from these sound effects libraries was not an intended application and it was another 20 years before such bespoke provision of sounds for music making became commercially available with the arrival of Simon Harris’ Beats, Breaks and Scratches (Citation1986). Vinyl sample LPs were primarily aimed at “DJs for use in nightclubs as well as in the creation of their own records and remixes. As such they contained breakbeats which had been looped to run uninterrupted for around three minutes” (Goodyer Citation1992).

A significant shift in music making practices was heralded by the arrival of digital samplers in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Early digital samplers encouraged music making from pre-loaded samples of audio. The Synclavier II (an early digital synthesizer and digital sampler system from 1982) offered disk streaming sampling, focusing on instrument timbres, while in the case of the Fairlight CMI, the sampler provided an expandable sound library accessible from 8’ inch floppy discs containing collections of short soundfiles (approximately between a quarter of a second to a whole second in duration). These libraries were not limited to the sounds of instruments, but included other sound effects derived from voices, objects and the environment. By providing small units of sound in this way, creative ways of music making sprang forth, inspired by the sampler’s ability to assign a sample to any note on a keyboard interface, thus maintaining the musicality, playability and pitched sound of a sample via this humble mapping procedure.

Some early libraries included samples of non-Western instruments. For example, the Fairlight CMI Series II’s disk no. 21 included a range of non-Western wind instrument samples ().

Figure 3. Fairlight CMI sound library documentation, revision 1.3, compiled by Peter Wielk. Disc 21, “wind” entry.

The Fairlight CMI’s extensive and eclectic sample provision offered an amalgamation of audio loosely categorised by headings of instrument type such as “percussion”, “wind” and “keyboards”. Content for the sound libraries was called upon from Fairlight’s global offices as Peter Wielk (Studio Manager and Product Specialist at Fairlight Instruments) describes: “it was ‘open season’ for sample acquisition, and there was also a pressing need for the Fairlight CMI to go out with an actual sound library. Samples had been created all over the world by both the distributers and end-users, who were encouraged to share their spoils with Fairlight HQ. And although most of these samples were excellent (and still sound brilliant today), many were incorrectly pitched, and there was absolutely no standardised description” (email correspondence with Peter Wielk, December 2022).

Of interest to this discussion was the sample labelling approach, which enabled identification of the sample when loaded and viewed on the Fairlight CMI’s monitor screen. The end-user would see the sample’s label, for example, “FLUTE4” when they were in fact interacting with an Indian flute sample (as confirmed in the CMI IIX library directory). Brevity in labelling was essential for viewing lists of samples on the Fairlight CMI’s small monitor, but the sound’s identity and integrity were compromised in this way.

Digital samplers such as the AKAI S1000, Ensoniq Mirage and EMU made use of floppy discs to access additional samples. AKAI employee Dominic Hawkens recalls the era of the upgradable sample floppy disc: “at AKAI UK, in Heathrow, they had all these sounds on floppy discs … you could turn up, load up the disc and copy them and they had a S1000 and S1100… I remember the first time I went to AKAI HQ, they had a little off-sales window where you could make an appointment and they would upgrade stuff, and there was a guy you could ring up and book, and you’d bring your own disc … this was the very first time you could get a library of sounds”. Ed Stratton (founder of Zero-G and pioneer of the sample library CD era) also remembers the time of the floppy disc sample provision, “I had sampled quite a lot of sounds myself and decided to try selling them”.Footnote11 His earliest sample library offering to the music production community took the form of 3½ floppy discs loaded with samples from his own personal sample collection. Stratton placed an advertisement in the classifieds of Sound On Sound magazine, for his floppy disc entitled “3D – Dance Disk Directory” marketed specifically for the Ensoniq Mirage.

The innovation in offering sounds on CD-ROM as a progression from floppy disc provision was somewhat stumbled upon as Hawkens describes “we got a SCSI hard disk and we plugged it into the S1000 and then read in all the floppy discs that we wanted and saved them out to the hard drive. Effectively we made a hard drive of what we wanted our CD to look like, so our hard drive became the master, and then we read the disc image off the hard drive to a file and then wrote that disc image back out to a CD and wondered if that would work, and it did. Kind of obvious now that you look back on it. We were able to take a hard drive snapshot, burn it onto a CD. Early CD burning software was just out. We were able to make CD versions of all the relevant sample collections by then” (in conversation with Dominic Hawkens, 2021).

The sample library CDs boom of the late 80s and early 90s made available vast numbers of samples in different categories and genres. The advantage and appeal of sample library CDs was their functionality on any sampler device you owned at home since they were non-sampler specific. Prior to such provision, sample libraries were supplied for the device you owned. Key providers in the sample library CD boom included AMG, East-West, Best Service and Zero-G who were soundware companies who spurred on developments and practices in sample library distribution.

Culturally diverse and non-Western instrument content on sample library CDs

Observing the handling and representation of non-Western instrument sounds within sample library CDs via a survey of this provision enabled insights into the attitudes towards difference in this early period of selling sound.Footnote12 Selecting CDs for this survey was guided by the era where this innovation first appeared (late 80s and early 90s). In seeking out the earliest of examples, the motive was to observe the representation standards for non-Western instrument content of this fledgling product whose precedence appeared to exert such influence on future product releases of a similar vein. The product conventions for sample library CDs found acceptance (and later expectation) in their end-user communities.

In these early examples, very few credit contributing musicians within CD cover art or liner note descriptions. In these instances, end-users interacted with these sounds without trace of where they had been sourced from. Terminology for describing the library’s content included frequent references to “mythical”, “exotic” or “ethnic” sound as a convention for communicating the “othered” nature of the content being sold. Visual art for these discs adopted sexualised images, predominantly women in suggestive positions along with a tendency to select images that reinforced cultural stereotypes or assumption of “primitiveness” or “otherness”. For example, an illustration of Moai statues from Easter Island provides the cover art for the sample library CD, Ethnic Flavours (1992) produced and distributed by Zero-G. Titles and descriptive text would relate tenuously or ambiguously to the instruments, sources, musicians, cultures and playing styles of non-Western instrument content, leading to inaccuracies and misinformation. These approaches created a palpable division between standard sound libraries (those including synth, vocal or drum sounds) and othered non-Western products. The Western sound library producers and distributors exerted orientalist preconceptions upon this sound content, portraying foreign musical cultures as obscure, strange and untamed.

Labelling of sources and instruments within track listings often reduced sounds to numerical entries whereby numbers would replace the actual names of the instruments. In doing so, end-users would engage with samples as they were labelled, rather than the real names, terms and identities. The blanket term of “ethnic” was used to categorise a wide variety of sounds from all around the world, without stating which country, region, tradition or culture they had originated from or were associated with. Such absence of specificity “narrows the marketable options … into a rather patronizing catch all” (Kelleher Citation2019, 49) for any sound or instrument regarded as non-Western or “foreign” sounding “from which it may be difficult to escape” (Ibid). These shortcomings and omissions indicate the cultural appropriation sustaining these products and markets. The taking of instrumental sounds, knowing little to nothing of what they are or where they are from, while brandishing them with the title “ethnic” erases everything about the sound and musician’s identity, is a process that demonstrates ignorance for the sake of profit and commodification.

The research noted a few isolated examples which appeared to go against these conventions for the time. Abracatabla (released on the AMG label, Citation1995), a sample library CD containing predominantly tabla sounds performed by Talvin Singh, is one of the few examples to include a musician’s name on the front cover of the sample pack (). Most offerings in this vein tended to “downplay the identity of the sampled artist” (Théberge Citation2002, 99). Placing Singh’s name upon the product packaging contributed to Singh’s growing fame and world-wide recognition. Singh recalls a trip to India in the late nineties where he was greeted by fans and a general awareness of who he was, which he associated with the sample pack’s uptake and global reach (In conversation with Talvin Singh, Citation2022, Tung Auditorium, Liverpool). Founder of AMG,Footnote13 Matt Wilkinson, noted that “a lot of artists liked to do it for the recognition – probably more of the drummer types as it was like [a] CV for them and a way to establish their skills etc. that they’d rarely get”.

Abracatabla stands as unique offering, led by the artist and cultivated by the freedom to include whatever content was deemed best. Wilkinson explains, “our emphasis with all our libraries was the artist first and foremost and then the title because we always tried to work with the best musicians … it was one of the last ‘big productions’ we did. It was recorded in a top pro studio and cost a lot to make. Wasn’t viable anymore and marked the end of the era of high-level sample libraries” (email correspondence, January 2023).

Contemporary distributors of sample packs

Exploring representation norms within sample library CDs containing non-Western instrument sounds (undertaken between 2021–22) provided a chance to make comparisons with current representation practices observable in downloadable sample packs. This comparative procedure reinforced the notion that the commercial sample pack product was preceded by the sample library CD. This evolution, spurred on by the dot.com boom of the late 1990s and 2000s, mirrors other similar digital media products such as music singles and albums, and their transition from physical formats (i.e. CDs) to downloadable equivalents. Acknowledging this format evolution is pertinent since any conventions or practices of concern could be explained by pointing back to earlier ways of handling, marketing, and representing content by way of a legacy argument. Selling downloadable sounds was not a new industry born overnight but was instead informed by previous practices tweaked to fit a new distribution model. Downloadable sample packs honoured their physical media predecessor in significant ways, i.e. by retaining visual artwork, content quantities and the general vocabulary used in marketing. Such retentions were to suit and sustain the needs of the end-user while satisfying expectations and levels of familiarity for the consumer. To see these products not as two separate isolated inventions, but as part of a single product’s development through time may ease some of the perplexities regarding the normalising of out-of-date nomenclature and provides another lens to view representation via a product’s advancement over time, which typically seeks to better serve its purpose and customer’s needs. Part of this project has contended with the unchallenged state of misrepresentation in sample packs and distribution platforms which harbour and promote particular orientalist attitudes to generate sales and attract end-users. My impatience perhaps is too obvious here, eager for provisions to keep abreast of topical movements, but this inertia has its own story and is more likely explained by the industry’s own challenges of agility.Footnote14 In the wake of Black Lives Matter, which continues to highlight the need for open dialogue on addressing inequalities, biases and racism, there is a sense that sample packs, as a pocket of the music industry, have operated for too long without questions asked of its responsibilities and duties around its representation practices. While other areas of the music industry such as concert programming, live music and workforce diversity have outwardly expressed statements, self-reflections and pledges to dismantle structural racism in the industry (along with dedicated movements and campaigns to support inclusive participation), sample pack production and distribution have somehow dodged this same reckoning. The sample pack industry is not specifically challenged by the need to diversify its product lines as one might observe in the beauty brand industry or music festival line ups; in contrast, the challenge is problematised by the frequent misrepresentations of diverse voices, content and contributions on digital platforms via the inaccurate depictions upon the wrappers or digital fronts distributors place upon them. Hall’s writings have frequently noted that representation issues are not simply to do with absence, low frequency appearance or marginality, but more to do with simplification and stereotypical characterisation (Citation1996, 442) often faced by the minorities those who are being represented. Others have pointed the finger at “industry personnel … [who] are uncomfortable with the burden of representation and the scholarly critiques that accompany these rolesFootnote15” … [but understand] their actions may have unintended consequences” (Whitmore Citation2016, 338). When probed on the responsibility to change in an evolving climate, the sample pack industry concedes that a combination of systemic issues have retained the status quo “it’s because producers didn’t speak up about where they sourced their samples from, and sample marketplaces aren’t themselves totally public-facing as [they] have a niche clientele, along with sample marketplaces having financial targets to achieve and do not want to negatively impact revenue by questioning industry norms, this has continued freely” (email correspondence with Joseph Gilling and Loopmasters 2023).

A lack of workforce diversity may well play its part as a factor in upholding out-dated practices, but it is also worth acknowledging that sample packs are part of a wider culture of exoticism and belong to a legacy of colonialism fraught with injustices such as appropriation and power struggles. In music production genres, such as electronic dance music (EDM), exoticism is woven into the very nature and following of this music culture. The terms “world music”, “tribal”, “exotica” and “ethnic” run deep, existing as accepted and popular musical styles and categories. Further, EDM and DJ remix culture have built a reliance on sampling whatever, whenever, fuelling a trend of cross-cultural musical mixing and significantly, the “growth of the world music category” (Chou Citation2021, 94–113). To abandon these terms is clearly desirable, but for the distributor, it may seem implausible to make the first move. Could such a relatively small cog in a larger wheel exert any influence or power in reforming while it waits for other parties to catch up? Some may say a collective effort would be needed where the whole music industry pledges to act all at once. For distributors, ridding themselves of problematic terms and questionable representation practices could risk leaving them at a loss without suitable alternative terms or conventions to ensure their end-users continue to engage with and consume their products. Therein lies the reminder that distributors manage a number of competing expectations including “(1) audiences’, musicians’, scholars’, and journalists’ views and expectations of world music and what makes it valuable; (2) their own views; and (3) their commercial, aesthetic, and ideological priorities as businesspeople and music lovers” (Whitmore Citation2016, 331).

One theory that rumbles on in the background of my discussion is that the tail end of the sample pack’s lifecycle, when sounds are consumed, used and mixed within productions, requires no crediting, acknowledgement or reference to the sample’s origin. This legitimate and entirely legal part of the deal is what makes sample packs persistently desirable. This upfront condition, written in the terms of use, removes the headache for the end-user regarding sample clearance, payments of royalties and importantly mitigates future lawsuits for copyright infringement. It also, in part, avoids the typical “musical invasions” (Feld Citation1996, 1) and cultural-appropriation-without-recompense practice sampling culture has been so readily and historically associated with.Footnote16 In the same way that Tracklib modelled a system for downloading music tracks for sampling, free of copyright via a one-off payment from the consumer, sample pack distributors serve a music production community who desire sounds without fear of legal implications later down the line. In a system that enables the anonymisation of samples use post-purchase, the reluctance to properly credit musicians, label sounds with care and accuracy, and attend to claims of authenticity might well be deprioritised or deemed irrelevant. This argument is clearly weak, but worth airing to present the reality of a sample’s lifecycle and ultimate destiny, and while void of identity, it still deserves to start its journey in an accurately represented form. This point may benefit from the analogy that any good chef would want to know (and verify) where their ingredients are coming from before creating a culinary dish.Footnote17 A highly idealised vision stemming from this point is that with representation challenges overcome and good practice in place, there may well be a greater willingness from end-users to “engage with or be transformed by the Other” beyond accessing “cultural titbits … selectively incorporated for marketing purposes in order to appeal to a wider variety of audiences” (Chou Citation2021).

Through this “then and now” comparative process I was curious to see “if the repertoires of representation around ‘difference’ and ‘otherness’” (Hall, Evans and Nixon Citation2013, 225) had been overcome or were still in play regarding the issues outlined previously (crediting, visual artwork, terminology, categorisation and specificity). Six distributors of sample packs were targeted (Ableton, Landr, Loopmasters, Noiiz, Splice, and Symphonic distribution) to explore contemporary approaches to handling and representing non-Western instrument sounds. Chosen for their position as central providers of sample packs, these distributors all act as hosts to third party sample packs (producers who provide sample pack content for distribution), while commissioning their own packs through in-house production teams. Their connection with global third-party providers enables vast quantities of diverse content to appear on their sites, sustaining high demands for original content via frequent releases. The quality of this content remains a priority for both distributors and end-users as Conor Bailey (Artist Relations Coordinator) from Loopmasters describes: “Some of our most successful packs have been those from around the globe … diverse sounds seem to sell really well … our customers really like authenticity, and things that are recorded to a high standard, not just thrown together in a sequence using a Kontakt instrument, these are really trained musicians who are very talented, and I think anyone with an ear for production tends to gravitate towards a higher production quality” (in conversation with Conor Bailey 2022). This ongoing interest in non-Western content for creativity is part of an age-old pattern where “cultures of socially subordinated groups are constantly mined for new ideas with which to energise the jaded and restless mainstream” (Saha Citation2012, 738). The sample pack industry and distribution model doubles this process by first sourcing or commissioning the audio product and then selling it on to end users.

Exploring a cross-section of non-Western instrument sample pack content from each provider enabled observations to be made about the handling and representation of diversity. Approximately 10 packs were selectedFootnote18 from each distributor and observations were collated on the following themes and questions:

Sample provision: What non-Western instrument content is hosted? Content availability across distributors showed plentiful availability of non-Western instrument packs. Non-Western instrument packs offered new fusions, themes and innovation via blends of cultural content with other genres and styles. The provision of Indian instrument sample packs regularly included sitar and tabla sounds, however variation beyond these two instruments was rare and indicated a limited view of further instrumentation and what constitutes Indian music.

Crediting of artists: Do musicians receive credit within sample pack information? Distributors host content where musicians are uncredited for their contribution to the sample pack they appear on. Sample pack descriptions downplay the issue by providing generic statements attesting to the involvement of performers e.g. “recorded by professional musicians”, “from the best musicians across India”, and “played by some of the most consummate and decorated Indian musicians”. This practice forgoes musicians’ names while crediting labels or production houses. A more conscious effort in profiling musicians in the branding of the product was observed on some platforms e.g. Splice offers a Splice Originals series, where artists are credited, their name features in the title and descriptions include video content introducing themselves and showcasing their instrument, but this was not mainstream practice. One rationale for the reluctance to credit involves labels strategizing to keep producers and musicians to themselves since explicitly naming individuals on sample pack titles, credits and descriptions has resulted in competitor labels poaching key individuals for their own financial benefit. Label Content Manager, Joseph Gilling from Loopmasters expands on this rationale further, “there can be other issues with associating artist names to sample packs too – customers may use said artist name in the branding of their subsequent music releases (e.g. Joe’s song featuring Carl Cox). This is misleading as it is not a real collaboration with the artist and can lead to damaging their public image. Other reasons are that sample pack producers may not want to be credited as they work with multiple different brands. A producer may work simultaneously with two competing providers and would rather keep that quiet. Whilst it’s a great thing to credit an artist for their contribution to a sample pack product, for individuals whose full-time employment is in this space, discretion is sometimes preferred” (in conversation, 2023).

Search criteria: Is it possible to search for non-Western instruments sample packs using the distributor’s search function? How are non-Western instrument samples located? Some distributors have replaced the “world music” category within their information retrieval systems. Landr uses the word “international” within their top level “genre” dropdown menu, while Splice and Symphonic Distribution both use “Global”. “World” or “world music” are terms in operation in Loopmasters, Ableton and Noiiz. These broader search categories operate as the primary way to locate and access non-Western instrument samples and runs counter to discourse on the “world music” term where many have branded it “flawed”,Footnote19 “controversial”Footnote20 “toxic”, “racist”,Footnote21 “bad culture” and “offensive”.Footnote22 Even with the alternative categories (“international” and “Global”) in play, the segregation of sounds based on their non-Western status is actively maintained via these top-level classification terms.

Sitar sounds were often found categorised under the “guitar” tag within distributor’s search systems (Landr). Noted was the categorisation of an Istanbul saztar and cümbüş (two Turkish stringed instruments) also found under the “guitar” category in Loopmasters. Free text search bars were useful for locating non-Western instruments (Loopmasters, Sounds.com), however this method relied on the correct spelling of the instrument and the end-users’ prior knowledge of the instrument’s name. Distributors often host a variety of non-Western instrument content that is not labelled correctly in terms of its title, individual sounds or tagging resulting in content being unsearchable. For example, a sample pack of Indian percussion instruments distributed on Landr, titled and labelled “Indian percussion”, contains 135 samples all labelled as “Percussion Loop” followed by a number e.g. “Percussion Loop 1”, “Percussion Loop 2 … ” These sounds are from a variety of percussion instruments identified aurally as sounds from mridangam, tabla, ghatam and kanjira. These instrument names are omitted from the labelling and thus, not locatable using the free search function.

Terms and categories: How are these sample packs labelled, titled, described and categorised? Terms such as “exotic”, “oriental” and “mysterious” are still prevalent in sample pack descriptions and titles.Footnote23 The word “spice” also regularly appears in sample pack descriptions of Indian instruments sounds or influence.Footnote24 Descriptions and titles can often be mismatched, for example, a sample pack called “Oriental” produced by EarthMoments, available on Ableton, contains samples of Ouds, Arabic drums, hand percussion, clarinets and bouzouki instruments. This titling (possibly alluding to an Asian connection or used in its pejorative sense as generalised othering) causes confusion by bundling a seemingly random selection of instruments into a catch-all title, where they find themselves distanced from their cultural homes via a title that unashamedly others everything that is non-Western. Non-Western instrument sample packs also often include sexual references to promote interest in these products. For example, the words “sensual”, “steamy” and “seductive” are common adjectives within such descriptions.

Sample pack descriptions regularly make claims of authenticity regarding instrument content. Overall, this word is both overused and misused in this context and primarily suggests samples are (i) original content i.e. not available elsewhere or reworked from other libraries and (ii) that they have been performed on real instruments, rather than synthesized. The word “authentic” however, does not appear connected or concerned with the sound being “authentically” derived from its culture, playing style or tradition. Authenticity as a cultural construct, open to interpretation, is important to ponder here in relation to selling samples. As a start, “authentication by experts and authentication by end-users” (Peterson Citation2005) likely produces two entirely different outcomes. A legitimate argument to any authenticity claim lies in the formatting demands of producing commercially viable sample packs (and previous sample library CDs) which subject technological processes “calculated to render them useful to Western sampling musicians” (Théberge Citation2003, 102), noting the quantising, time stretching and grid fixing for “loopability” along with any re-tuning, which in fact transforms the sounds via these curatorial changes. Gouly observes “how the positionality of the human actors involved in the production of sample packs, and the market forces constraining their production, shape how idiomatically ‘authentic’ these materials are perceived” (Gouly Citation2019, 114). Authenticity is, as Grazien suggests, “what consumers in a particular social milieu imagine the symbols of authenticity to be” (Citation2004, 34). These arguments intensify in the case of non-Western instrument sample packs (which can be generated and produced by members of the said musical culture or not) and then enter a Western marketing and distribution system where qualified authorities (the workforce) in non-Western music making are limited or non-existent, begging the question, how can the unfamiliar ever be authenticated? Whitmore goes a step further to explain “industry personnel [in the business of selling world music] grapple with what they imagine audiences have ‘been led to believe’, what they themselves believe, and which visual, auditory, and narrative markers make a music [or samples] authentic to which audiences” (Whitmore Citation2016, 336).

Visual artwork: What artwork accompanies non-Western instrument sample packs? Artwork for non-Western instrument sample packs demonstrated a variety of approaches. Many included imagery of the featured instrument(s) while others opted for intricate patterned backgrounds and text combinations. Some “world” themed packs chose artwork which appeared inspired by art or fabrics with geometric patterns sitting somewhere between Peruvian Aguayo fabric and African batik. Some packs use sacred and cultural symbols as the primary subject of the visual artwork such as Hindu gods, Buddha heads and Thai demon guards. The harm of such imagery is that “marketing representations have the power to make us believe that we know something of which we have no experience and to influence the experiences we have in the future” (Borgerson and Schroeder Citation2002, 251).

Selling sound, as these findings have shown, has continually faced challenges within branding and marketing. Sound, as an entirely aurally consumed product has always needed a helping hand from visuals, titles, labels and categories for end-user comprehension and for encouraging commercial consumption since they are “physically intangible” (Koiso-Kanttila Citation2004, 48). These extra components operate together within a “signifying practice”, forging a representation of the sound in much the same way that paratextual material (book covers, album art, video game iconography and downloadable app thumbnails) represent interior content on behalf of the actual content. The intention of packaging samples, in CD or downloadable format is to “connect graphic elements closely with specific musical content” (Rivers Citation2003, 21) and can have significant business consequences, such as determining a product’s success (Moore Citation2004). New unions are forged when sound and image meet during the assigning of sample pack visual art, solidifying associations, links and depictions. Perceptions of certain musical genres, styles and cultures have been made by reinforcing stereotypes via choices of images, for example people and their music become associated with certain characteristics due to their perceived membership of a social group. Hall reminds us that a stereotype is something “reduced to a few essentials, fixed in Nature by a few, simplified characteristics” (Citation2013, 249) and also comments that “stereotyping tends to occur where there are gross inequalities of power” (Citation2013, 258). Sample pack visuals appear particularly vulnerable to the traps of stereotypes and clichéd imagery, where incorrect assumptions have not only misrepresented the sounds (and musicians) but have also shaped attitudes towards difference in and beyond this creative community. When in operation, the role of stereotypes is “to make fast, firm and separate what is in reality fluid” (Dyer Citation2009); stereotypes work by making complex ideas quick and easily to interpret. In a semiotic sense, the signifier and signified have been “fixed by our cultural and linguistic codes which sustain representation” (Hall, Evans, and Nixon Citation2013, 31). Continued misrepresentation with such images and text perpetuates the cycle, influencing future producers and distributors on how a non-Western instrument sample pack should look, therein satisfying end-users’ expectations.

Misrepresentation is exemplified within sample pack artwork via the continued use of visual “markers of the exotic” (Whitmore Citation2016, 344). As mentioned these include Hindu gods and Buddha sculptures which appear as dislocated spiritual symbols, applied in a way that disregards their sacred status by dismissing the “boundaries between purity (sanctity) and impurity” (Arya Citation2017). Images of eroticised and scantily dressed belly dancers and geishas waving fans on artwork reiterate the orientalist portrayal of women as submissive and seductive, feeding temptations while distorting these images into oversexualised caricatures. Sample packs also tend to include totem poles and carved masks as a means to communicate a connection to primitiveness of indigeneity. The fetishising of sound through these visuals sets up suggestions (in some cases) of spiritual powers, sexual energy, desire, emotion and forbidden pleasures. Théberge noted the “quasimagical powers” of early sample CDs where the “promise implicit in world music sampling is not simply access to new creative materials duly authenticated, but the fact that the samples carry with them primal powers that can be transferred to the user/consumer – powers that can then be used to induce specific effects on the listener” (Citation2003, 100).

These symbols found on sample pack artwork “speak volumes and require little explanation” (Moore Citation2004) and are so readily drawn upon for representing non-Western instrument sounds to establish a visual shorthand for difference and “othered” content. Reductive imagery of this kind limits the end-user’s understanding of these cultures and sounds, diminishing the chance for a more informed opinion or perspective from developing. As Borgesson and Schroder describe, the critical damage of this reductive imagery is not the offence caused in the moment, but the impact these misrepresentations have on the semiotically and ontologically associated groups and individuals and their opportunities for the future (Citation2002, 571).

All sample packs face the same challenge of pushing a product which is incomplete; individual sounds by themselves do not make music; instead, what is marketed is the potential for creativity (albeit reliant on the capabilities of the end-user) and the promise of something new, fresh and unavailable elsewhere. These potentials are exaggerated and amplified in the case of non-Western instrument sounds since they are sources of new, unfamiliar or hard-to-obtain content. In many cases, the visuals and descriptions take on the heavy lifting for these unfamiliar sounds, influencing end-users on how they should be listened to perceived, and used.

Towards change

Changes and shifts have started to appear within distributors’ policies and advice documents that reflect on their own practices and aim to assist third party producers (see - screenshot taken from Loopmasters Content Branding Policy) in their approaches towards representing diversity.Footnote25

This example from Loopmasters, calls into question not the representation of culturally diverse sound, but the relevance of this imagery for a trance-related sample pack. With this hypothetical example, the conjunction of image and text establishes an association between a religious symbol and a music genre, encouraging the consumer to infer a particular creative potential from reading this pairing. “They [image, text and sound] gain in meaning when they are read in context, against or in connection with one another” (Hall, Evans, and Nixon Citation2013, 232). The appropriation of a cultural symbol to market trance samples (which have nothing to do with Hinduism despite the frequent conjunction or association) demonstrates the problematic nature of this intertextual meeting of sound, image and text.

Loopmasters have committed to addressing their back catalogue by flagging 116 packs in terms of their artwork relevance, genre classification, title issues, claims of authenticity, appropriation, branding concerns and inaccurate religious connections. These actions spurred on by the finding of this research show a distributor recognising their responsibility as a mediator of representation and liable party in influencing perceptions of race and difference within music production communities.

Part 3 – constructing a sample pack

The project’s creation of a new sample pack containing Indian musical instrument sounds set out to challenge the conventions witnessed in the above discussion, aiming for better practice in representation and overcoming orientalist tendencies. Creating a sample pack was a practical means of navigating the journey of sample pack development, generating learning and insights regarding interactions between distributors, producers and musicians.

Creating the instruments INDIA sample pack

A working groupFootnote26 was set up in 2021 to facilitate the transformation of the Instruments INDIA archive to the sample pack.Footnote27 This team liaised with all the musiciansFootnote28 to audition their recorded content. The team also proposed content for the sample pack and acted as an interfacing mechanism between all parties. Our guiding principle for these meetings was to conduct the transformation process (from archive to sample pack) with the musicians, in a mutual and equitable way. Musicians decided what samples went forward into the sample pack. The working group discussed and decided that the sample pack would have few to no effects added (as in a “dry” pack with little processing or manipulation by effects) to ensure the samples stayed faithful to the original recordings. Dedicated listening time was scheduled to reflect on the samples as a collective group and gave opportunity for sounds to be withdrawn or replaced with alternatives.

Musicians expressed priorities around their audio to best represent their virtuosity and contribution. Sample packs have a fixed quality to them, operating as miniature recordings that (in the context of our sample pack) tie a musician’s name and reputation to each sonic contribution. Ensuring each sample was musically sound (from the musician’s perspective) was a key concern, dominating much of the working group’s discussion. As with any music recording, perfection and accuracy became paramount before approving the commercial release.

For some musicians, the grid engendered a mixture of curiosity and concern. Snapping a sample to a grid is a common feature of almost all sample pack content. This process ensures a sample’s rhythmic precision over a 2, 4 or 8 bar loop and is a process that requires subtle time stretching (known as warping in Ableton) and quantising in some cases of isolated parts of each loop. When implemented, time stretching and quantising renders samples as useable, meaning that they can be easily dropped into a DAW since beats and melodies align perfectly with grids, tempos and grooves.Footnote29 As the Instruments INDIA pack contained a high percentage of rhythmic and melodic loops, snapping these to a grid was guided by pragmatism and end-users in mind. A more liberal approach to using the grid was implemented for freer-style vocal material as well as the harmonium content, which both employed a more liberal and improvisatory style that somewhat resisted grid snapping. This approach resulted in the creation of phrases. Phrases are like loops but do not necessarily have the regularity or length that loops have.

The working group used the meetings with musicians to probe issues of labelling when it came to how individual loops and one-shots were termed. The convention in the industry follows a norm of:

BPM, key, instrument name/identifier, sample number and file format:

e.g. 82_Gb_Tar-ShenaiLoop_04.wav.

The key designation of this labelled convention does not really work for Indian music, which employs ragas rather than keys, so the team developed a more appropriate approach. For example, instead of labelling a loop as being in the key of C Major, a loop was labelled with the associated raga name, for example, “Bilawal”. This was particularly important for melodies from the sitar, sarod, tar-shenai and dilruba as well as for vocal content. We later discovered that this preferable labelling was incompatible with the distributor’s search system, which end-users use to locate samples based on their Western key name embedded within the labelling. If we embedded the Indian scale names into the labelling, our samples would not be searchable. This incompatibility is what Gouly terms as a “disjuncture”, noticeable “between those who produce pre-composed materials [samples] and the musical communities that they serve or service” (Citation2019, 128). Once the samples were handed over to the distributor, they were later tagged with metadata making the samples searchable via instrument name or genre categories. We noticed limitations in the distributor’s available tags, where non-Western instruments such as sarod, tar shehnai and dilruba samples were assigned with the “guitar” instrument tag, demonstrating the confining nature of the labelling system. These tensions around labelling and tagging of sound for product optimisation brings to mind Van Toorn’s “patron discourse” where “cultural practices of minority groups are only liberated into the public domain to the extent that patron discourses succeed in trapping them in the categories which the dominant audience has available to contain them” (Citation1990, 103) and further underscores “the difficult[ies] that categorisation will get us into” (Hutnyk Citation2000, 213). The finite set of tags and inflexible labelling observations corroborates with Said’s third dogma of Orientalism that the “Orient is eternal, uniform, and incapable of defining itself; therefore it is assumed that a highly generalised and systematic vocabulary for describing the Orient from a Western standpoint is inevitable and even scientifically ‘objective’” (291). Like the Orient, Non-Western instrument sample packs lack “autonomous agency” and are funnelled through a Western marketing system to achieve commercial viability. Said’s encouragement to focus on how othered societies are represented, along with the language that is used, and the way verbal and written interactions create a view of something, demonstrates in this instance, a system intolerant of difference which itself strips away the integrity and accuracy from such incoming samples.

Artwork was generated for the sample pack by the distributor’s in-house design team. The first design made use of an intricate pattern arranged around an octagonal title window (). The working group noted similarities with this design to other existing non-Western instrument sample pack artworks and questioned its ability to cut through a saturated market as a unique offering. More specifically, the pattern was deemed clichéd in its depiction of Indian culture due to the similarity of the design applied to products with an association to India, for example, Darjeeling tea boxes, supermarket-bought Indian food, as well as condiments such as chutney and ready meals.Footnote30 The prevalence and default nature of the pattern was noted, “it’s used everywhere … its always the fallback option designers come to. They literally have no other ideas or ways to present something from another culture. They don’t even try … on a basic level, yes it works because people instantly can see that it’s something ‘ethnic’ and something not from here [i.e. the UK]. But with that assumption comes a lot of other conscious and subconscious bias judgement even before looking into what it is” (in conversation with Archana Shashtri, Director of Marketing and Communications, Milap, 2023).

The repetition of visual clichés within sample pack artwork “mould[s] people’s minds and souls in a specific direction. In this view, the cliché does not only threaten the unique individual simply because of what it represents — infinite copies of the same thing – but also because of what it does: easily digestible and easily repeated, the cliché prevents people from critical reflection and original thought” (Berger Citation2011, 181). The intricate pattern shown in appears to have been taken up and adapted from Indian sari fabrics, architecture, mandala art or rangoli designs, and while maintaining a connection with India in an instant (the immediate first impression), its continual use leaves no room for other artwork, innovation or creativity when considering different iconography or visual branding alternatives.

The second design blended a purple-magenta cut out border overlayed upon a photograph of two Indian instruments (a veena gourd and tabla membrane are visible). The title occupied a more prominent position and included Milap’s branding (). The product description listed all contributing musicians and provided hyperlinks to their websites and their instrument(s). This crediting detail was deemed particularly significant for the musicians as Rajeeb Chakraborty, sarod musician explains, “as an instrumentalist, I would like to say a big thank you that you have thought from this angle. The first big one [sample library of an Indian instrument] was produced in England by Talvin Singh, Abracatabla … it became an absolute sensation. After that so many producers have met and made [samples] with Indian musicians. But nobody has that idea of giving credit to the people involved in it. It’s not only about the money … it’s also about giving credit to musicians who have invested all their lives to produce those great sounding syllables. All musicians will appreciate this … it gives you so much pride” (in conversation, 2021).

Making the Instruments INDIA pack took a markedly different approach to other instances of non-Western instrument content production. The agency of the musicians to represent their musical traditions and playing styles was exhibited via their participation, direction and autonomy, but as this article has described, this was regularly disrupted and compromised due to Western systems for digital packaging, categorisation and sound formatting required for the sale and distribution of the sample pack. On reflection, there were two key factors which appeared to strongly delimit the scope for difference: (i) the question of who generates/produces the sample pack (is it members of the musical tradition/culture or outsiders to the musical culture?) and (ii) the narrow and restrictive categorisation and formatting procedures within distribution systems. These factors, in combination, chip away at the ability of individual musicians (and the musical cultures) to represent themselves accurately and in contrast and contention to circulating stereotypes.

Part 4: moving forward

Creating the instruments INDIA sample pack (2021–2022) provided an opportunity to do things differently regarding representation and equity. This process was informed and guided by the musicians, Milap and the above research findings. Observing past and present practices of sound product branding and marketing and holding discussions with musicians, distributors, producers and end-users, culminated in the formulation of a guidance document for producers and distributors of sample packs containing culturally diverse content and non-Western instrument sound. This co-created resource stands as an anti-orientalist set of principles, derived by the musicians who contributed to the Instruments INDIA sample pack, and shaped by interactions with Loopmasters who distribute the Instruments INDIA sample pack on their online platform and Loopcloud subscription service. The document forms part of Loopmaster’s Content Branding Policy and Product Optimisation Guide in efforts to encourage producers to consider the creation and representation of non-Western instrument sample packs in the form of a contract agreement.

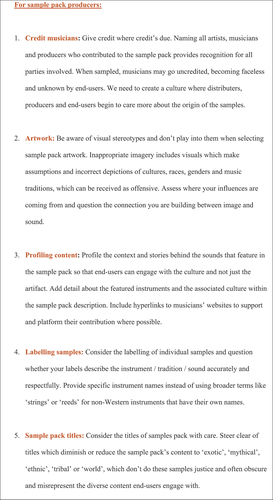

The following guidance for producers and distributors exists as a PDF document within Loopmasters’ Content Branding Policy and is distributed to all of Loopmasters’ affiliated producers (approximately 90 globally based third party producers).

Creating the sample pack and guidance document operated as acts of opposition to orientalism observable in contemporary music production and consumer contexts. Orientalist branding and marketing for audio products, along with Orientalist systems for organising packs into categories and descriptions based on reductive terminology combine to accommodate a certain type of product conceived by the West’s perceptions of the other. The “support system of staggering power” (Said Citation1978, 306) upholding these perceptions and products is sizeable, comprised from a mix of inherited predecessor practices, the music industry, the Internet and its information retrieval systems, which all work together to keep these perceptions and terms in play. Disrupting these perpetual defaults, for example, attending to visible insensitivities at the point of sale provides a strategy that anticipates knock-on effects throughout the production process and into other music industry areas. Thus, tackling the music industry’s problems with terminology and imagery at the sample pack stage intends to support change further upstream since their front matter and categorisation play formative roles at the start of the music production chain, acting as inspiration and influence on a producer’s next steps.

Next steps

Engagement and collaboration with Loopmasters has continued via a shared approach to improving representation issues within sample packs. Their establishment of a Content Branding Policy (2023) envisions the hosting of “a safe and inclusive space where all individuals and cultures are represented fairly and authentically” (2023). The policy sets out the need for sample pack producers to “reflect on their product artworks, titles, descriptions, and promotional materials, alongside the audio samples, presets, and patches themselves” and extends to the rejection of inappropriate terminology, “we must not use terms such as ‘ethnic’, ‘tribal’, ‘oriental’, or other cultural, socio-political, or religious generalisations. These marginalise communities and reinforce stereotypes”(Loopmasters, Content Branding Policy, 2023). Such terms impede a deeper, more accurate understanding of these sounds from forming and operate as “stand ins” (Taylor Citation2007, 209) hiding the reality of the content’s origin from the end-user.

By including the guidance () within distributor’s policies, it is anticipated that a before and after picture of sample pack production may begin to emerge within Loopmasters’ own catalogue and hosting of third-party packs. Work has begun to track and follow such transformations, including data on existing packs to redress existing misrepresentation, while ensuring any new sample packs produced beyond this point abide by the 2023 policy. The wider vision extends to observable shifts around representing diversity in the music industry, with my heart set on an overhaul to the terminology which has been relied upon for so long for non-Western content.

Conclusions

The process of working collaboratively with musicians to produce a sample pack from archived sound provided an experiential learning opportunity to address issues of representation in relation to branding and marketing of non-Western instrument sounds. Exploring an industry where stereotypes, clichéd imagery and out-of-date terminology are commonplace motivated the actions and questions of the research.

By exploring the history of selling sound it has been possible to map out the product evolution of sample packs from sound effects LPs, floppy disc sample libraries, sample library CDs and finally to present day downloads. Each juncture of this history has provided insight into the conventions, norms and ways of handling this content. Custom ways of promoting, branding and representing sound in the days of sampler libraries and sample library CDs left an imprint on the way non-Western sounds are handled today, feeding and satisfying end-user expectations about the other by confining difference to a set of limited tropes, stereotypes and terminology. The derivation and sourcing of sound for libraries and pack provides but one factor in achieving a more equitable existence and marketing, however the control musicians have over these sounds, their labelling and branding is limited by systems that show ill-flex in accommodating difference.

Instilling good practice around terminology, visual art, representation, crediting and labelling, at both producer and distributor levels via a guidance document aims to influence how others choose to represent difference on these platforms and also, how end-users receive and engage with these packs. Co-creating this document with musicians and distributors has proved vital in arriving at meaningful content that amplifies the voice of musicians within a system that has traditionally favoured the label or producer’s name over the individuals providing the sonic content.

Exploring representation practices within sample packs has offered learning beyond the sample pack focus. Other digital products, services and consumables face similar challenges of representation where images and text play significant roles in establishing and upholding specific beliefs and interpretations of difference. Questioning the connection between artwork, title and sonic content prior to distribution can provide a starting point to develop and encourage greater cultural competency.

Finally, this article contests the persistent practices of misrepresentation within sample pack creation and distribution but takes a non-prohibitive stance on the production and distribution of non-Western instrument sample packs. In advocating for sampling and its associated musical practices, the author’s view is one that continues to view and value sampling and sample pack use as sites for boundless possibility and creativity. In the sample pack world, musician-led products are clearly favourable, giving autonomy to the individuals whose musical cultures and traditions are being represented through sound, however there is an understanding that audio products are often produced by mix of talent, expertise and enterprise personnel covering technical, formatting and artistic vision. As this case has shown, it was a blend of voices convening together on a common goal which has made this research and set of findings possible. This article is not about shutting down production or distribution, but instead, offers a way to build cultural competency with difference in music and sound to facilitate the continued expansion of sample pack provision from producer and musician communities, globally, who are keen to share their music, instruments and sound on digital platforms.

Geolocation information

The research took place in the UK and involved interview data collection from practitioners, some of whom are based in India. The subject matter deals with Indian musical instruments and musicians from India.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Manuella Blackburn

Manuella Blackburn is a Reader in Electronic Music and Sound Design at Keele University. She is a practice-researcher who creates electronic music and investigates sound from intercultural perspectives. She has published texts on sound-based compositional methodologies, sampling, musical borrowing and intercultural creativity.

Notes

1. Stuart Hall’s line of questioning remains important to this article’s discussion: “How do we represent people and places which are significantly different from us? Why is ‘difference’ so compelling a theme, so contested an area of representation?” (Hall, Evans and Nixon Citation2013, 215)

2. A partnership formed to explore the inclusion of Indian musical instruments in digital and electronic music contexts, initiated in 2012.

3. Two musical works as part of an AHRC funded fellowship (2012–13) plus three commissioned compositions (2016). See Blackburn Citation2014, 146–153 for a full account of this project.

4. A gharana is tradition or mode of musical training which has its own distinct features.

5. The topic of a new form of Indian classical music cultivated in the UK became the PhD subject for Milap CEO, Alok Nayak. This topic emerged from this early discussion and reflection activity.

6. Milap support for artists includes progression routes and professional development programmes like national youth orchestra SAMYO and the new music band TARANG.

7. Blackburn completed two experimental electronic works in 2013 (Javaari and New Shruti for sarod and electronics).

8. Milap is an Indian arts and culture company (Limited Company and charity funded by Arts Council England).

9. Feld Citation1996. “The recordings of course retain a certain indexical relationship to the place and people they both contain and circulate. At the same time their material and commodity conditions create new possibilities whereby a place and people can be recontextualized, rematerialized, and thus thoroughly reinvented”.

10. A precedent for using a sound archive as the basis for a sample pack was set by in the creation of the PRES sample pack, distributed by Ableton (Sounds from the Polish Radio Experimental Studio, 2018). “200 raw samples from original PRES compositions turned into almost 300 sounds, loops and effects”. The electronic tape compositions by Eløbieta Sikora, Krzysztof Knittel and Ryszard Szeremeta were used as source material for the content of the sample pack. These composers were key figures in the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio (Studio Eksperymentalne Polskiego Radia, PRES; 1957–2004).

11. Ed Stratton, email correspondence 15/04/21.